Abstract

Post-industrial landscapes represent one of the most complex challenges for contemporary sustainable land management, as they combine environmental degradation, cultural heritage, and socio-economic restructuring. This study examines five representative post-industrial sites within the Dąbrowa Basin (southern Poland), selected from an initial pool of 20 locations to capture the full diversity of contemporary transformation pathways. The research integrates multi-temporal satellite imagery (1999–2025), historical maps (1936, 1965), extensive field surveys, and a systematic review of literature and regional press to assess environmental, functional, and cultural dimensions of landscape change. The results reveal four distinct transformation trajectories: hydrological reclamation, heritage-led revitalization, passive ecological succession, economic redevelopment, and one additional case of unmanaged degradation. Hydrological and cultural revitalization produced the most sustainable outcomes, characterized by high environmental stability, strong public accessibility, and preserved industrial identity. Natural succession created ecologically valuable but functionally limited spaces, while commercial redevelopment ensured economic stability at the cost of industrial memory. Sites lacking coordinated revitalization remain unsafe, inaccessible, and environmentally unstable. The study demonstrates that post-industrial transformation is strongly influenced by municipal engagement, land ownership, historical legacy, and the interaction between natural and engineered processes. These findings contribute to the international discourse on sustainable post-industrial redevelopment and highlight the need for integrated, cross-sectoral strategies supporting multifunctional, resilient landscapes in Central Europe.

1. Introduction

Post-industrial landscapes have emerged as one of the major challenges in contemporary land management, environmental engineering and sustainable regional planning. The global decline of mining, quarrying, metallurgy, cement production and related heavy industries has left vast areas of degraded land that require long-term ecological restoration, structural stabilisation and functional reintegration into broader settlement and landscape systems [1,2,3]. These areas are typically characterised by soil contamination, hydrological disturbance, geomorphological instability, vegetation degradation and biodiversity loss, combined with socio-economic challenges such as unemployment, spatial marginalisation, urban shrinkage and the erosion of local identity [4]. Their transformation plays a critical role within the European Green Deal, circular-economy strategies, climate adaptation frameworks and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [5].

Current scholarship conceptualises sustainable reclamation as a multidimensional process integrating ecological recovery, economic restructuring, cultural regeneration and social inclusion [6,7,8]. Foundational theoretical approaches include landscape ecology, ecological engineering, landscape urbanism, heritage-led regeneration and socio-economic transition theory, all of which highlight the need to reconnect biophysical processes with human-centred functions [9,10,11,12]. Numerous analytical frameworks have been proposed to guide these transformations, including multi-criteria brownfield assessment [13], connectivity-oriented redevelopment models [14] and ecosystem-based transition approaches [15]. These models collectively emphasise that effective post-industrial regeneration requires both the restoration of degraded ecosystems and the adaptive reuse of industrial structures, which together reinforce environmental stability and generate new cultural and economic opportunities [16,17].

Recent advances in ecological engineering and technical reclamation emphasise hydrological restoration, soil–water optimisation and the integration of nature-based solutions as core mechanisms of long-term environmental recovery. Experimental studies demonstrate that solid mining waste can improve water-retention capacity in loamy soils, accelerating the regeneration of vegetation cover and early-stage succession [18]. Other research highlights the multifunctional role of artificial water bodies—such as flooded extraction pits and engineered lakes—as components of blue–green infrastructure that support biodiversity, regulate hydrological regimes and provide recreational value [19,20]. Complementary work in environmental modelling and landscape monitoring shows that long-term assessment of post-mining terrain requires multi-source, multi-temporal data, including satellite imagery, historical cartography and field verification [21,22].

Parallel to environmental trends, socio-cultural research emphasises that post-industrial landscapes function as narrative environments, where memory, symbolic meaning and collective identity shape public perception and acceptance of redevelopment projects [23]. Studies within environmental humanities and cultural geography show that places formerly associated with extraction, labour and industrial power often acquire new meanings through reinterpretation, storytelling and heritage-based design [24]. Governance capacity and stakeholder coordination have also been identified as decisive factors determining whether post-industrial transformation leads to inclusive, multifunctional landscapes or remains limited to narrow, economically driven redevelopment [21,25,26]. Integrated approaches linking heritage conservation, landscape design, creative industries and community engagement are increasingly recognised as essential for socially resilient and culturally meaningful transformations.

The European context provides numerous examples illustrating the diversity of post-industrial trajectories. Heritage-led revitalization in the Ruhrgebiet, Upper Silesia, Wallonia, Ostrava–Karviná Basin and the Donbas region demonstrates how preserved industrial structures can be reinterpreted as cultural, educational or tourism-oriented facilities, forming the backbone of new regional identities [27,28,29,30]. Prominent case studies such as Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord, Ile-de-Nantes and Docks-de-Seine in France, the Humenné in Slovakia and the Hanyang Ironworks redevelopment show how industrial artefacts can be embedded within multifunctional green spaces that combine recreation, ecology and creative industries [31,32,33,34]. Hydrological reclamation strategies have reshaped entire regions such as the Lusatian Lake District—Europe’s largest artificial lake system—and numerous former lignite pits in Germany and Czechia, illustrating the potential of water-based reclamation for climate adaptation and landscape restructuring [35,36,37]. At the same time, spontaneous ecological succession has produced valuable semi-natural habitats on former extraction sites across Europe, contributing to biodiversity and ecological connectivity [38].

In Poland, the transformation of post-industrial landscapes remains heterogeneous and strongly dependent on municipal capacity, governance arrangements, ownership structures and regional planning frameworks [39]. As one of the most historically industrialised regions of Central Europe, the Dąbrowa Basin (Zagłębie Dąbrowskie) has experienced extensive extraction-based development over more than 150 years, including coal mining, sand exploitation, limestone quarrying and cement production, which significantly altered local geomorphology, hydrology and settlement structure [40]. Today, the region contains a diverse mosaic of industrial ruins, abandoned quarries, flooded pits, slag heaps, hydrologically reclaimed lakes and heritage complexes adapted to cultural or recreational uses. While various successful initiatives have emerged—ranging from cultural revitalization to hydrological reclamation and passive renaturalisation—many sites remain degraded, underused or only partially integrated into broader territorial strategies.

Despite the substantial international literature on post-industrial transformation, no comprehensive study has yet compared the full spectrum of ecological, hydrological, cultural and functional trajectories within the Dąbrowa Basin using an integrated, multi-temporal and multi-source methodology. This gap underscores the need for a systematic assessment that captures long-term spatial dynamics, evaluates adaptive readiness and situates regional patterns within broader European and global frameworks of post-industrial transition.

1.1. Research Gap

This study addresses the identified research gap by providing a comprehensive, multi-temporal and multi-source analysis of post-industrial transformation pathways in the Dąbrowa Basin. The specific aims are as follows:

- Identify and classify the dominant transformation trajectories occurring across post-industrial sites in the region, including hydrological reclamation, heritage-led revitalization, spontaneous ecological succession, commercial redevelopment and unmanaged degradation.

- Assess long-term spatial dynamics (1999–2025) using satellite imagery, historical maps and field observations to document changes in land cover, hydrology, vegetation development and structural preservation.

- Evaluate environmental, functional and cultural conditions using an integrated set of indicators covering landscape quality, ecological integrity, hydrological stability, accessibility and heritage value.

- Compare adaptive readiness across different site types, highlighting opportunities and constraints for sustainable reuse.

- Develop a typology of five transformation models grounded in empirical evidence and aligned with contemporary international frameworks for post-industrial regeneration.

- Situate the Dąbrowa Basin within global and European post-industrial transitions, demonstrating how its mixed trajectories reflect broader patterns observed in regions such as the Ruhrgebiet, Lusatia, Wallonia and Upper Silesia [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

1.2. Aim and Contribution of the Study

The present study addresses the identified research gaps by conducting a comprehensive comparative analysis of five representative post-industrial sites within the Dąbrowa Basin, selected from an initial inventory of twenty locations. The research aims to:

- Identify and compare the dominant post-industrial transformation trajectories observed in the region, including hydrological reclamation, heritage-led revitalization, spontaneous ecological succession, commercial redevelopment and unmanaged degradation.

- Assess environmental, functional and cultural outcomes for each site through an integrated evaluation of landscape quality, ecological conditions, hydrological dynamics, accessibility and the preservation of industrial structures.

- Determine the key factors influencing adaptive readiness, including environmental stability, safety, functional diversity, heritage value, governance capacity and community engagement.

- Classify and refine transformation models that represent the main pathways of sustainable post-industrial redevelopment in the Dąbrowa Basin and comparable regions.

- Situate regional developments within broader European and global frameworks, comparing the region’s trajectories with international examples of post-industrial landscape management, including those from the Ruhrgebiet, Upper Silesia, Wallonia, the Ostrava–Karviná Basin and the Lusatian Lake District.

To achieve these objectives, the study integrates multi-temporal satellite imagery (1999–2025), historical topographic maps (1930 and 1965), systematic review of academic literature, regional press analysis, and extensive field surveys conducted between 2020 and 2025. This mixed-methods approach enables the long-term visualisation and quantification of landscape change, the assessment of adaptive readiness and the identification of site-specific drivers of transformation.

The findings provide one of the most comprehensive assessments of contemporary post-industrial landscape evolution in Central Europe. They demonstrate how the interplay of ecological processes, hydrological restructuring, industrial heritage preservation and governance models shapes the direction, pace and sustainability of post-industrial transitions. This integrative perspective positions the Dąbrowa Basin as a valuable laboratory of landscape transformation, offering actionable insights for planners, policymakers and local authorities seeking to balance ecological regeneration with cultural, social and economic development objectives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Initial Inventory

The methodological framework was designed to capture long-term, multidimensional post-industrial transformation processes in the Dąbrowa Basin. The study integrates historical reconstruction, multi-temporal satellite analysis, cartographic comparison, field surveys, and qualitative socio-cultural assessment.

The first stage involved developing a comprehensive inventory of post-industrial sites using multiple complementary data sources.

The initial identification of locations was based on the OPI-TPP 2.0 national database, which provides descriptive records, metadata and photographic documentation of former industrial sites in Poland. This supported the preliminary screening of sites according to

- Industrial origin;

- Period of activity;

- Remaining structures;

- Availability of archival information.

To refine this inventory, additional analyses were performed using

- Google Earth Pro (v. 7.3.6)—multi-temporal satellite imagery (2003, 2009, 2020, 2025);

- Geoportal.gov.pl—layers topographic maps (1965, 2025);

- Digitised pre-war maps (1936) from the Digital Repository of Scientific Institutes (RCIN);

- Cadastral data;

- Local and regional press archives (2000–2025).

Local experiential knowledge from multigenerational residents was used only as contextual guidance for interpreting ambiguous spatial features and was always cross-validated with cartographic and field evidence.

The initial pool of 20 sites (Table 1) was selected because it represents the full industrial and landscape diversity of the Dąbrowa Basin. All locations originate from the same historically unified industrial system (mining, metallurgy, quarrying, sand extraction, cement production) and exhibit clear, measurable post-industrial transformations, forming a coherent comparative sample.

Table 1.

Initial inventory of 20 post-industrial sites in the Dąbrowa Basin.

Based on these combined sources, 20 post-industrial sites were identified.

Inclusion criteria required

- Documented industrial activity;

- Detectable landscape or structural change within the last 20–25 years;

- Availability of historical and contemporary imagery;

- Physical accessibility for field assessment.

Each site underwent screening using remote sensing (1999–2025), historical maps (1936 and 1965), press archives (2000–2025) and field verification (2023–2025).

Sites were excluded when

- (a)

- Imagery was incomplete;

- (b)

- Access was restricted;

- (c)

- No measurable transformation occurred after closure;

- (d)

- The site lacked relevance to the study’s analytical framework.

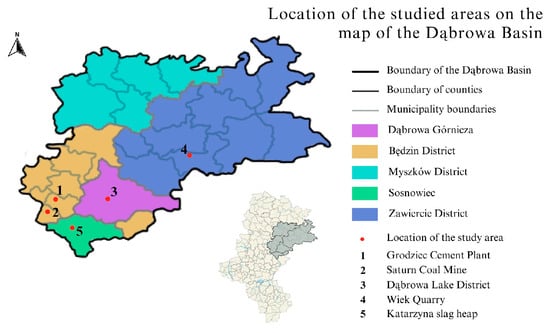

The five selected sites represent the full spectrum of observed transformation trajectories in the region: hydrological (Pogoria), heritage-led (Saturn), passive ecological (Wiek Quarry), economic redevelopment (Katarzyna Slag Heap), and unmanaged degradation (Grodziec). No other site in the initial inventory presented unique features beyond these categories.

2.2. Literature and Regional Press Analysis

A systematic review of scientific literature, technical reports, planning documents and regional development studies formed the theoretical and contextual basis for interpreting spatial and environmental changes. The review focused on

- Reclamation approaches;

- Ecological and hydrological restoration;

- Industrial heritage management;

- Socio-environmental transitions;

- Regional planning frameworks in Central Europe.

Regional press analysis (2000–2025) included municipal bulletins, news portals and archival newspapers. These sources provided information on

- Public perceptions and conflicts;

- Redevelopment decisions;

- Safety issues and accidents;

- Community initiatives;

- Municipal involvement and investment patterns.

Press materials often supplied temporal details not visible in satellite imagery or maps (e.g., phases of abandonment, informal uses, early revitalization).

2.3. Analysis of Historical and Contemporary Spatial Data

Historical and contemporary cartographic datasets were integrated to reconstruct multi-decadal landscape transformations. Three main data groups were used:

- (1)

- Pre-war topographic maps (1936; used selectively)

A digitised pre-war topographic map (1936) obtained from the Digital Repository of Scientific Institutes—RCIN was used exclusively for the analysis of the Katarzyna Steelworks slag heap (Huta Katarzyna).

It documents the early extent and morphology of the metallurgical waste deposit and transport links associated with the steelworks.

It was not used for the other four case-study sites.

- (2)

- Mid-20th-century topographic map (1965)

A 1965 topographic map, accessed via Geoportal.gov.pl, reflects industrial spatial organisation during the peak of heavy industry and was used to identify

- Extraction pits.

- Industrial buildings.

- Transport infrastructure.

- Spoil heaps.

- (3)

- Contemporary cartographic data (2025)

Modern topographic maps (2025 layer, Geoportal) were used to assess current instances of the following:

- Land-use categories.

- Hydrological structures.

- Settlement patterns.

- Recreational infrastructure.

- Vegetation distribution.

- Preserved or demolished industrial elements.

Comparative analysis across all datasets enabled the reconstruction of long-term transformation trajectories.

2.4. Google Earth Pro Analysis

Google Earth Pro (version 7.3.6) served as the principal tool for analysing multi-temporal satellite imagery. The Time Slider function was used to access all available satellite photographs of each study site across different years.

Because GEP imagery availability varies by scale, resolution and dataset, the earliest usable satellite photographs ranged from 1984/1985 (coarse-resolution Landsat-based imagery) to the late 1990s (higher-resolution commercial imagery). In all cases, the full available timeline—approximately 2000 to 2025—was analysed to ensure continuous temporal coverage with one from 1985.

2.4.1. Temporal Analysis Protocol

To ensure comparability across time, the following protocol was applied:

- Identical viewing frame (bounding box locked for each site).

- Identical camera angle and scale for all time points.

- Consistent time intervals: every available year was examined; key transition years were extracted for documentation.

- Visual interpretation of

- -

- Vegetation dynamics;

- -

- Structural demolition;

- -

- Progressive exposure or infilling of pits;

- -

- Shoreline development;

- -

- Informal access paths;

- -

- Regeneration patterns.

2.4.2. Quantitative Measurements

- Polygon tool was used to delineate and calculate the area of extraction pits, flooded basins, forests, spoil heaps and built-up zones.

- Path/Ruler tools supported measurement of shoreline changes, expansion of vegetation patches, removal of spoil heaps and development of road/path networks.

- All measurements were recorded in WGS84 (default GEP coordinate system).

2.4.3. Interpretive Accuracy and Cross-Validation

Satellite-based observations were systematically cross-checked with

- Historical topographic maps (1936, 1965);

- 2025 topographic maps;

- Orthophotos;

- Field surveys (2023–2024);

- Regional press descriptions (2000–2025).

This multi-source validation ensured reliable reconstruction of transformation trajectories such as hydrological reclamation, spontaneous ecological succession, heritage decay or revitalization, and commercial development.

2.5. Field Surveys

Field surveys were conducted from 2023 to 2025, supplemented by partial observations in 2020 and 2021. To capture seasonal variation, each site was visited multiple times in spring, summer and autumn.

A standardised field protocol assessed

- Safety: slope stability, hazardous structures, unsecured quarry edges, unsafe voids.

- Maintenance & monitoring: fences, cameras, lighting, signage.

- Industrial heritage: buildings, shafts, foundations, machinery, markers.

- Environmental quality: waste accumulation, vegetation health, erosion, scenic value.

- Vegetation structure: managed vs. unmanaged; succession stage (I–III).

- Accessibility: entrances, footpaths, public transport, barriers.

- Cultural presence: murals, events, commemorations, local narratives.

- Municipal involvement: recent investments, renovation works, evidence of ongoing management.

2.6. Data Synthesis and Site Selection Criteria

To synthesise findings from diverse data sources, a structured Multi-Criteria Assessment (MCA) was developed (Table 2). The evaluation framework addressed reviewers’ concerns by introducing clear, measurable and replicable criteria.

Table 2.

Evaluation categories and operational scoring definitions used in the Multi-Criteria Assessment (MCA).

All eight criteria were assigned equal weights because they represent complementary aspects of adaptive readiness and none dominates functionally (Table 3). Total scores (0–16) were divided into three readiness classes using equal terciles: 0–4 (low), 5–10 (medium), 11–16 (high).

Table 3.

Final classification thresholds for adaptive readiness (MCA scoring system).

The final MCA score (0–16) was classified into three categories reflecting the degree of adaptive readiness: low (0–4), medium (5–10) and high (11–16). These thresholds were established to ensure consistent interpretation of site conditions, enabling comparison across different types of post-industrial landscapes.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Study Area

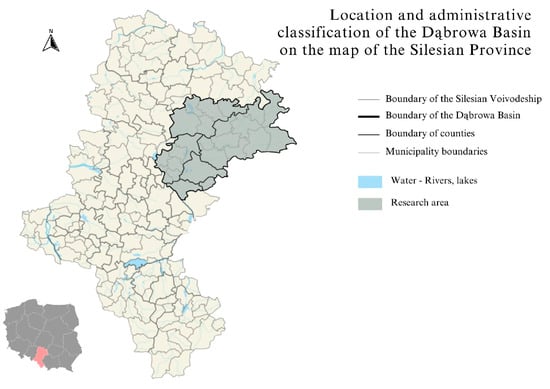

The Dąbrowa Basin is a region (Figure 1) shaped by intensive industrial activity spanning nearly 150 years, which resulted in the formation of a highly heterogeneous post-industrial landscape. The five selected sites (Figure 2) demonstrate distinct physical structures, levels of environmental degradation, and post-industrial legacies inherited from mining, quarrying, cement production, and metallurgical processes. Contemporary land-use patterns vary widely, reflecting both formal reclamation initiatives and spontaneous ecological responses.

Figure 1.

Location and administrative classification of the Dąbrowa Basin on the map of the Silesian Province.

Figure 2.

Location of the studied areas on the map of the Dąbrowa Basin.

Across the sites, the most evident transformations include

- Infilling and flooding of extraction pits;

- Spontaneous afforestation of abandoned quarries and spoil heaps;

- Partial or complete demolition of industrial buildings;

- Redevelopment of former industrial zones into commercial or recreational areas;

- The emergence of unmanaged vegetation and informal uses in neglected locations.

These characteristics form the basis for evaluating the degree and direction of revitalization and reclamation processes.

3.2. Multi-Criteria Assessment (MCA) Scoring

To address the need for measurable evaluation, all five sites were assessed using the 0–16 point Multi-Criteria Assessment (MCA) introduced in Section 2.6.

The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

MCA scores (0–16) for the five study sites.

Summary of scoring results

- The highest scores were recorded for Saturn (16/16) and the Dąbrowa Lake District (14/16).

- Katarzyna Slag Heap reached high readiness (12/16).

- Wiek Quarry showed intermediate conditions (5/16).

- Grodziec Cement Plant scored the lowest (2/16).

3.3. Multi-Temporal Spatial Changes (1999–2025)

Multi-temporal analysis based on Google Earth Pro satellite imagery (1985–2025) and Geoportal topography maps (1965–2025) revealed measurable and distinct transformation patterns across all five study sites. Key quantitative changes are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of multi-temporal spatial changes (1985–2025) at the five study sites.

The spatial analysis demonstrates a clear divergence in transformation pathways. Sites such as the Dąbrowa Lake District and Saturn Coal Mine show major functional and structural redevelopment, documented through increased water area, expanded infrastructure and stabilised vegetation. In contrast, Grodziec Cement Plant and Wiek Quarry exhibit either unmanaged natural succession or degradation, with measurable increases in canopy cover but no infrastructural improvements. Katarzyna Slag Heap represents a complete functional and morphological reset, with all industrial features removed and replaced by commercial development.

3.4. Environmental and Functional Assessment of the Five Sites

3.4.1. Grodziec Cement Plant

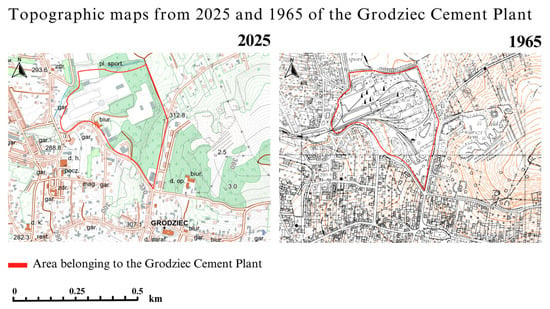

The Grodziec Cement Plant, covering approximately 32 ha, represents the most advanced stage of structural degradation among the examined sites. Field observations (Figure 3) reveal extensive collapses of industrial buildings, uncontrolled vegetation succession, and widespread safety hazards resulting from unsecured ruins. Satellite imagery from 2009–2025 (Figure 4) confirms a complete absence of revitalization efforts, with dense shrubs and pioneer tree species gradually obscuring the remaining industrial structures. No new infrastructure, functional reuse, or spatial interventions have taken place in over two decades.

Figure 3.

Images taken during field research at the Grodziec Cement Plant in 2020. (a) Photo taken facing north, showing the silo. (b) Photo inside of the buildings on the east side of the silo. (c) Photo taken facing north-west, of the building behind the silo. (d) Site map showing where the photos were taken.

Figure 4.

Satellite images from 2009 and 2025 of the Grodziec Cement Plant from Google Earth Pro. Imagery © Google/Maxar Technologies.

Historical topographic maps from 1965 (Figure 5) illustrate the original extent of the cement works, including processing buildings and quarry-related facilities. When compared with contemporary orthophotos, they reveal a near-total loss of industrial identity and functional connectivity. The site is now dominated by unmanaged natural processes, classifying Grodziec as a case of post-industrial decline characterized by low adaptive readiness, environmental instability, and minimal integration into its urban surroundings.

Figure 5.

Topographic maps from 2025 and 1965 of Grodziec Cement Plant from Geoportal (Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography, Poland).

Additional historical and regional documentation helps contextualize this trajectory. Local heritage records confirm that Grodziec was the first cement plant in the former Kingdom of Poland, expanded multiple times throughout the early 20th century and ultimately closed in 1979 due to technological obsolescence [39]. Architectural archives describe subsequent deterioration, including roof collapses, fires, and prolonged abandonment, which accelerated natural overgrowth and reduced the structural integrity of surviving buildings [40]. According to municipal announcements, significant intervention became possible only in 2024, when the city of Będzin secured a record 72 million PLN in external funding to initiate cultural and service-oriented adaptive reuse [41]. These sources collectively illustrate a long period of neglect followed by an abrupt reactivation enabled entirely through external financial mechanisms.

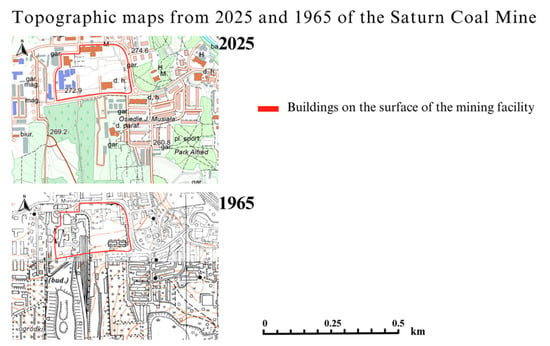

3.4.2. Saturn Coal Mine

The Saturn Coal Mine, occupying approximately 7.3 ha, is one of the most dynamically transformed sites. Satellite imagery from 2009, 2020, and 2025 (Figure 6) clearly shows extensive redevelopment, including the restoration of key buildings, creation of pedestrian routes, and managed vegetation. Field surveys (Figure 7) confirm that revitalization efforts are concentrated in the eastern part of the site, where preserved industrial buildings have been fenced, catalogued, and designated as historical monuments. The western part continues to function as an active industrial area, including automotive workshops.

Figure 6.

Satellite images from 2009, 2020 and 2025 of the Saturn Coal Mine from Google Earth Pro. Imagery © Google/Maxar Technologies.

Figure 7.

Images taken during field research at the Saturn Coal Mine in 2020. (a) The avenue leading from the car park towards the built-up area facing North; (b) Maria Nogajowa Public Library Branch No. 5—Media Library.

Historical topographic maps (Figure 8) depict the full operational layout of the mine, enabling comparison between past and current spatial patterns. The coexistence of cultural, administrative, and industrial uses demonstrates a flexible post-industrial trajectory. Saturn thus represents a strong example of heritage-led revitalization, where architectural preservation and selective adaptive reuse contribute to high adaptive readiness.

Figure 8.

Topographic maps from 2025 and 1965 of Saturn Coal Mine from Geoportal (Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography, Poland).

Extensive regional documentation further supports this interpretation. Archival materials from the Saturn Museum detail the mine’s operation between 1887 and 1996, including the development of its characteristic surface structures and the historical significance of the power station, now converted into the “Elektrownia” Art Gallery [42]. Local accounts describe the revitalization of the former pithead building (cechownia), restored as a cultural center following comprehensive conservation works [43,44]. Press reports also confirm ongoing investments, including the construction of the first municipal indoor swimming pool within the former mine premises, planned for opening in 2026, which enhances the site’s multifunctionality [41]. Regional photo archives highlight more than a century of mining heritage and underline the site’s symbolic importance for the identity of Czeladź [45]. Together, these sources confirm Saturn as a model example of successful heritage-oriented revitalization [46].

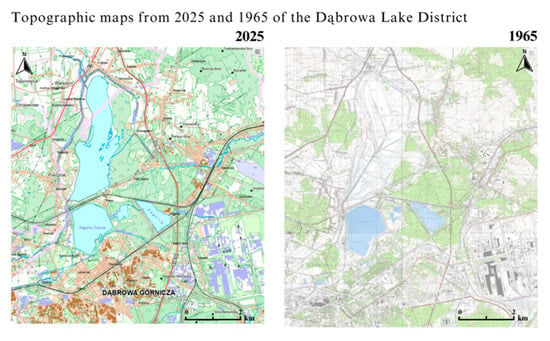

3.4.3. Dąbrowa Lake District (Pogoria I–III, Kuźnica Warężyńska)

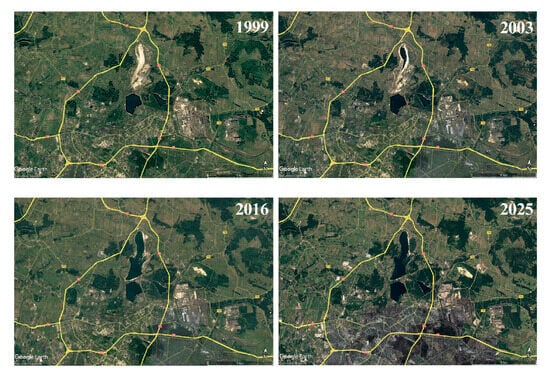

The Dąbrowa Lake District, covering approximately 1200 ha, constitutes the largest post-industrial landscape analysed in this study. Multi-temporal satellite imagery (1985–2025) documents a continuous hydrological evolution transforming former extraction pits of the Pogoria I–III and Kuźnica Warężyńska basins into a coherent lake system. Early imagery from the 1980s and 1990s shows several isolated depressions partially inundated by groundwater, whereas images from 2003 display extensive flooding following the cessation of pumping operations. By 2016, the system reached full hydrological continuity, reflecting a complete transition from an extraction landscape into a stable aquatic–terrestrial mosaic (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Satellite images from 1999, 2003, 2016 and 2025 of the Dąbrowa Lake District from Google Earth Pro. Imagery © Google/Maxar Technologies.

Hydromorphological assessment indicates that the surface area of all reservoirs increased from approximately 308 ha in 1985 to 795 ha in 2025, driven primarily by the construction and filling of the Kuźnica Warężyńska reservoir (Pogoria IV). Shoreline expansion was also substantial, growing from 10.5 km in 1985 to 25.5 km in 2025. The most dynamic changes occurred along Pogoria III and Pogoria IV, where littoral development, sediment redistribution and anthropogenic shaping (including beaches and recreational zones) resulted in visible shoreline reconfiguration. Pogoria I and II exhibited moderate but continuous natural succession, expressed in reed expansion and the formation of shallow littoral shelves.

Field observations from 2023–2024 (Figure 10) confirm a high degree of landscape stabilisation and functional diversification. Engineered embankments, managed greenery and recreational infrastructure dominate the surroundings of Pogoria III and IV, whereas Pogoria II maintains a more natural character with extensive wetland vegetation. In contrast, the newly formed basin of Pogoria IV reveals a combination of engineered structural elements—stone revetments, hydrotechnical installations, controlled outlets and stabilised slopes—which have progressively naturalised since the completion of filling in 2006. Historical topographic maps from 1965 (Figure 11) highlight the scale of transformation: areas once occupied by extraction fields, internal transport lines and drainage corridors now form water bodies with stabilised and ecologically functional shorelines.

Figure 10.

Image taken during field research at the Dąbrowa Lake District in 2024.

Figure 11.

Topographic maps from 2025 and 1965 of Dąbrowa Lake District from Geoportal (Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography, Poland).

Quantitative analysis conducted using Google Earth Pro (1985–2025) shows that Pogoria I increased its water surface from 62 to 75 ha, Pogoria II from 18 to 26 ha, and Pogoria III from 195 to 208 ha. Pogoria IV, filled between 2002 and 2006, reached 486 ha in 2025. Shoreline development followed similar trajectories: Pogoria III expanded from 5.8 km to 6.5 km, while Pogoria IV increased from 10.2 km at the moment of filling to 13.0 km in 2025. The reservoirs show clear hydrological stabilisation, with minimal interannual variation in inundated area despite measurable seasonal fluctuations in water level, especially in Pogoria III and Pogoria IV (Table 6).

Table 6.

Hydromorphological characteristics of the Pogoria reservoirs (1985–2025).

Regional literature provides additional depth. Studies by Jaguś and Rzętała identify the Pogoria reservoirs as key elements shaping the local landscape and regulating hydrology following sand extraction [47]. Regional tourism data confirms that Pogoria I–III serve as major recreational destinations, while Pogoria II maintains a natural, protected character supporting diverse fish species, birds, and wetland vegetation [48,49]. Entries in the Silesian Encyclopedia describe shoreline morphology, formation processes, and contemporary management strategies for Pogoria I and III [50,51]. Local press frequently highlights the cultural and symbolic significance of the lake district, often referring to it as one of the greatest natural assets of Dąbrowa Górnicza [52]. These sources collectively position the Pogoria system as a flagship example of hydrological reclamation integrated with recreation, ecological protection, and regional identity.

Overall, the Dąbrowa Lake District displays a high level of adaptive readiness, expressed through the stability of hydrological conditions, well-established vegetation patterns, extensive recreational use and the presence of engineered hydrotechnical structures. The system exemplifies a successful large-scale hydrological reclamation project, integrating engineered interventions with natural succession processes and contemporary recreational and ecological functions.

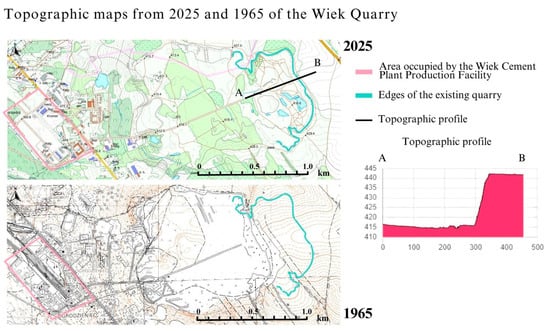

3.4.4. Wiek Quarry

Wiek Quarry spans approximately 130 ha and displays some of the clearest long-term extraction-related modifications among the examined sites. Topographic maps indicate that within 35 years of operation, the quarry edge migrated approximately 300 m northeast, demonstrating the direction and intensity of excavation. Terrain profiling (A–B, 454 m) performed using Geoportal confirms the presence of steep quarry walls reaching up to 30 m (Figure 12), forming a distinctive geological exposure.

Figure 12.

Topographic maps from 2025 and 1965 of Wiek Quarry from Geoportal (Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography, Poland); AB—terrain profile.

Satellite imagery from 2009 and 2025 (Figure 13) shows no significant changes in land use, indicating that the site has remained inactive for at least two decades. Natural succession gradually expands across the quarry floor, although steep limestone escarpments remain exposed. The absence of safety measures (Figure 14), infrastructure, and municipal intervention positions Wiek Quarry as a case of passive, nature-driven transformation characterized by medium adaptive readiness and high scientific and geotouristic potential.

Figure 13.

Satellite images from 2009 and 2025 of the Wiek Quarry from Google Earth Pro. Imagery © Google/Maxar Technologies.

Figure 14.

Images taken during field research at the Wiek Quarry in 2025. (a) Facing North; (b) facing West.

Regional geological and landscape sources reinforce this interpretation. Local descriptions identify Jurassic limestone walls, fossil-bearing strata, and characteristic geomorphological formations, situating Wiek within a broader category of post-extraction landscapes typical of the Kraków–Częstochowa Upland [53]. Studies by Majgier, Badera, and Rahmonov demonstrate that such quarries commonly host spontaneous ecological succession, producing mosaics of pioneer and forest habitats with high biodiversity [54]. Research by Skreczko and Wolny further underscores the didactic and recreational value of inactive quarries, citing their frequent use for field education and geotourism [55]. Together, these observations confirm the site’s potential as a natural geoscience resource, albeit limited by safety constraints.

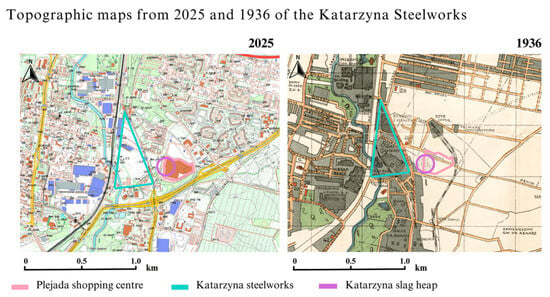

3.4.5. Katarzyna Slag Heap

The Katarzyna slag heap, now transformed into the “Plejada” commercial district, covers approximately 17 ha. Satellite imagery from 1999–2025 (Figure 15) shows complete morpho-functional restructuring: metallurgical waste deposits were leveled, vegetation cleared, and extensive retail and service buildings constructed. Field observations confirm full urbanization of the area, with additional commercial development progressing during the last decade.

Figure 15.

Satellite images from 2009 and 2025 of the “Plejada” Shopping Center from Google Earth Pro. Imagery © Google/Maxar Technologies.

Historical maps (Figure 16) document the original industrial morphology of the slag heap, which has been entirely erased in the contemporary landscape. Although the site demonstrates high economic productivity and spatial stability (Figure 17), all traces of industrial heritage have been removed. As a result, the Plejada area represents a clear case of commercial redevelopment driven predominantly by economic priorities.

Figure 16.

Topographic maps from 2025 and 1936 of Katarzyna Steelworks from Geoportal (Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography, Poland).

Figure 17.

Images taken during field research at the “Plejada” Shopping Center in 2025. (a) Facing West, direction of the steelworks buildings; (b) facing North.

Regional documentation helps explain this trajectory. Historical accounts describe the slag heap as a by-product of metallurgical operations active from the late 19th century until the closure of the Katarzyna Ironworks in 2010 [56]. Press reports portray the heap as a long-standing landmark in Sosnowiec, repeatedly associated with redevelopment debates and concerns about land-use change [57]. Additional reports note that the area narrowly avoided conversion into a logistics center before being fully leveled and redeveloped into the Plejada Shopping Centre during the 2000s and 2010s [58]. These sources confirm a transformation centered on economic imperatives, with complete erasure of industrial identity and no preserved heritage elements, supporting its classification as a commercially driven redevelopment lacking cultural continuity.

3.5. Comparative Evaluation of the Sites

The comparative analysis summarized in Table 7 highlights the distinct transformation pathways observed across the five locations. Three overarching patterns emerge:

Table 7.

The comparative characteristics of the studied sites.

- Highest adaptive readiness (10–16 occurs in sites where environmental restoration has been combined with cultural or recreational functions (Saturn, Dąbrowa Lake District, Katarzyna slag heap). These sites show strong municipal engagement, high accessibility, and well-maintained infrastructure.

- Intermediate readiness is associated with sites undergoing either passive natural succession (Wiek Quarry) or economic redevelopment (Katarzyna Slag Heap). These transformations stabilize the terrain but provide limited cultural or ecological benefits.

- Lowest readiness is characteristic of unmanaged and degraded sites that have not undergone revitalization (Grodziec Cement Plant). These areas present safety issues, low visual quality, and minimal functional value.

The contrast between sites underscores the influence of governance, funding availability, heritage preservation strategies, and the type of reclamation adopted.

3.6. Synthesis of Results

Across all sites, the research identified four dominant transformation trajectories:

- Hydrological reclamation (Pogoria system).

- Cultural and heritage revitalization (Saturn Coal Mine).

- Passive ecological succession (Wiek Quarry).

- Economic redevelopment (Katarzyna Slag Heap).

with Grodziec representing a fifth category—architectural degradation without functional reuse.

Collectively, these findings reveal that multifunctional, well-planned revitalization efforts yield the most sustainable outcomes, while unmanaged or purely economic approaches produce limited long-term benefits. This synthesis forms the foundation for further discussion on regional planning and policy implications.

4. Discussion

4.1. Regional Patterns of Post-Industrial Transformation

The five analysed sites demonstrate the coexistence of multiple transformation pathways shaped by over a century of industrial activity in the Dąbrowa Basin [59]. Mining, sand extraction, metallurgy and cement production created a heterogeneous set of geomorphological forms—slag heaps, quarries, pits and industrial complexes—whose post-industrial trajectories reflect differing levels of intervention and governance [60].

The MCA results highlight strong contrasts between sites undergoing coordinated revitalization and those evolving through unmanaged natural processes. Hydrological reclamation, most prominently represented by the Dąbrowa Lake District, constitutes the most spatially extensive change, corresponding to reclamation patterns documented in the Lusatian Lake District and post-lignite regions of Germany [59,60,61]. Multi-temporal imagery confirms lake expansion, shoreline restructuring and infrastructure development comparable to other European water reclamation landscapes [61].

Heritage-led revitalization, as exemplified by the Saturn Coal Mine, aligns with adaptive reuse strategies widely implemented in the Ruhrgebiet, Ostrava and similar European industrial regions [27,28,31]. Restoration of selected structures and incorporation of cultural functions reflect broader European approaches emphasising industrial identity preservation [39,40].

Sites lacking formal interventions, including the Grodziec Cement Plant and Wiek Quarry, exhibit spontaneous ecological succession, consistent with patterns observed in abandoned limestone quarries of the Kraków–Częstochowa Upland and Central European karst terrains [40,54]. These areas show increasing vegetation cover and structural decay typical of unmanaged post-industrial landscapes [38].

The conversion of the Katarzyna Slag Heap into a commercial area represents a pathway where economic forces dominate. Similar transformations have been noted in international cases in which industrial morphology is fully removed and replaced by new urban forms [56,57,62].

4.2. Comparison with International Frameworks

The identified transformation pathways correspond to dominant European frameworks for post-industrial redevelopment. Hydrological reclamation aligns with blue–green infrastructure principles promoting water retention, ecosystem stability and integrated land use [21,22]. The Pogoria system demonstrates this hybrid model, combining engineering with natural succession.

Heritage-led revitalization corresponds with European cultural sustainability policies that integrate preserved industrial structures into urban strategies [31,63,64]. The Saturn site illustrates these principles through selective building preservation and multifunctional reuse.

Passive natural succession aligns with ecological concepts of spontaneous renaturalisation [14,38,64], increasingly recognised as a legitimate reclamation approach under conditions of limited intervention.

Commercial redevelopment reflects market-driven models prioritising economic reintegration, comparable to international redevelopment cases in rapidly urbanising regions [33,34,65].

Regulatory frameworks influence the direction and pace of transformation. Indonesia demonstrates strong legal enforcement of reclamation duties [66,67,68], Canada emphasises climate-specific rehabilitation and long-term monitoring [69], while Polish post-mining landscapes remain characterised by uneven documentation and fragmented oversight [43]. These comparisons place the Dąbrowa Basin within a wider spectrum of global reclamation practices.

4.3. Governance, Funding and Local Context

Differences among the five sites underscore the importance of municipal engagement, land ownership and investment continuity. High-readiness locations—such as Saturn and the Dąbrowa Lake District—are characterised by sustained administrative support, systematic investment, and integration into broader recreational or urban systems [45,46].

Where administrative involvement is limited, as at Grodziec Cement Plant and Wiek Quarry, transformation proceeds mainly through natural processes [56,57]. While ecological value increases, the lack of maintenance and safety infrastructure limits public use [43].

Commercial redevelopment, as in the Katarzyna slag heap area, operates within a governance context dominated by private-sector priorities [58,59], producing stable but functionally uniform landscapes.

These findings align with broader analyses showing that governance capacity, inter-sectoral coordination and funding availability strongly shape revitalization outcomes [69,70].

4.4. Methodological Reflections

The integrated methodological approach—combining multi-temporal satellite data, historical cartography, field observations and regional press analysis—proved effective for reconstructing landscape trajectories [66]. Satellite imagery captured long-term spatial trends such as shoreline changes, vegetation dynamics and structural decay, while archival maps revealed industrial footprints no longer visible in contemporary data.

Field surveys provided essential information on safety, accessibility, maintenance and structure condition—factors not identifiable through remote sensing alone. Press archives enriched the analysis by providing insights into temporal decision-making, public debates and site-specific developments [44,47].

Limitations include variability in early satellite resolution, incomplete historical documentation and seasonal differences during field surveys. Similar methodological constraints are discussed in reclamation research in Canada and the global mining sector [67,71].

4.5. Synthesis of Transformation Models

The combined evidence supports the classification of the study sites into five models:

- Hydrological reclamation;

- Cultural–architectural revitalization;

- Passive natural succession;

- Economic redevelopment;

- Unmanaged degradation.

These models correspond with patterns described in post-lignite reclamation, ecological succession studies, zoning-based reclamation frameworks [72] and Polish mining rehabilitation analyses [73]. Their coexistence within one industrial region demonstrates the diversity of post-industrial trajectories influenced by environmental conditions, heritage value, governance and land-use pressures.

The typology developed here offers an empirical framework applicable to other post-mining landscapes in Central Europe and supports evidence-based planning for sustainable redevelopment.

4.6. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the availability and resolution of satellite imagery vary across sites and years, which may reduce the precision of early-period landscape interpretation. Area measurements based on manual digitisation in Google Earth Pro also introduce an estimated uncertainty of ±5%, despite cross-validation with orthophotos and topographic maps. Historical maps from 1936 and 1965 differ in scale and cartographic conventions, which may limit the comparability of industrial features over longer time spans.

Field surveys were conducted seasonally between 2023 and 2025, but winter conditions and restricted-access zones were not fully documented, potentially affecting the assessment of vegetation structure and accessibility. The study also does not include quantitative socio-economic or governance indicators, which could complement spatial and environmental analysis. Finally, the MCA framework applies equal weights to all criteria, providing transparency but simplifying the relative importance of safety, heritage, environmental quality and accessibility. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and comparing them with other post-industrial regions.

5. Conclusions

This study examined long-term transformation processes across five representative post-industrial sites in the Dąbrowa Basin, integrating multi-temporal satellite imagery, historical cartography, field surveys and a structured Multi-Criteria Assessment (MCA). The results demonstrate that post-industrial landscapes within a single industrial region can follow markedly different developmental pathways shaped by hydrological conditions, heritage value, governance arrangements and investment patterns.

Hydrological reclamation, as observed in the Dąbrowa Lake District, produced the most extensive and spatially coherent transformation, characterised by shoreline stabilisation, growing aquatic area and integration with recreational functions. Heritage-led revitalization at the Saturn Coal Mine illustrates how selective conservation of industrial structures can support functional diversification. In contrast, sites undergoing passive natural succession (Wiek Quarry) or unmanaged degradation (Grodziec Cement Plant) evolve through ecological processes that enhance vegetation cover but provide limited functional or infrastructural development. Commercial redevelopment at the Katarzyna Slag Heap demonstrates a distinct trajectory dominated by market-driven objectives that replace industrial morphology entirely.

The comparative analysis indicates that the most robust and multifunctional outcomes arise when environmental restoration is accompanied by coordinated municipal involvement and clear long-term planning. Conversely, the absence of governance support tends to result in fragmented or informal transformations. These findings highlight the importance of integrated management across administrative boundaries, particularly in regions characterised by diverse post-industrial legacies.

The five transformation models identified in this study—hydrological reclamation, cultural-architectural revitalization, passive succession, economic redevelopment and unmanaged degradation—offer an empirically grounded typology applicable to other post-mining and post-industrial regions in Central Europe. The combination of MCA scoring, remote-sensing timelines and field verification provides a replicable methodological framework for assessing adaptive readiness and long-term landscape change.

Future research should focus on expanding quantitative indicators of ecological performance, examining socio-economic impacts of revitalization strategies and evaluating long-term governance mechanisms that influence redevelopment outcomes. Integrating these dimensions could further support evidence-based planning and enhance the sustainable transformation of post-industrial landscapes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.; methodology, M.T.; validation, D.K. and M.T.; formal analysis D.K.; investigation, K.D.; resources, K.D.; data curation, D.K. writing—original draft preparation, K.D.; writing—review and editing, M.T.; visualization, K.D.; supervision, D.K.; project administration, M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Festin, E.S.; Tigabu, M.; Chileshe, M.N.; Syampungani, S.; Odén, P.C. Progresses in restoration of post-mining landscape in Africa. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, A. Circular economy in sustainable development of cities. Econ. Environ. 2019, 71, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, P.; Mali, B.; Fischer, W. Post-Mining Regions in Central Europe: Problems, Potentials, Possibilities; Oekom Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualetti, M.J.; Frantál, B. The evolving energy landscapes of coal: Windows on the past and influences on the future. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2022, 30, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Updating the 2020 Industrial Strategy; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, J.; Langhorst, J. Rethinking urban transformation: Temporary uses for vacant land. Cities 2014, 40, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaeen, S. Redeveloping former military sites: Competitiveness, urban sustainability and public participation. Cities 2006, 23, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daineko, L.; Karavaeva, N.; Yurasova, I. Redevelopment of ex-industrial areas in Yekaterinburg. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1079, 032093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtović, S.; Siljković, B.; Pavlović, N. Methods of identification and evaluation of brownfield sites. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Haase, D.; Priess, J.; Hoffmann, T.L. The role of brownfields and their revitalization for the functional connectivity of the urban tree system in a regrowing city. Land 2023, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Zdyrko-Bednarczyk, A.; Bednarczyk, J. Importance of Blue–Green Infrastructure in the Spatial Development of Post-Industrial and Post-Mining Areas: The Case of Piekary Śląskie, Poland. Land 2025, 14, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hakimi, H.A.; Azmi, N.F.; Li, K.; Duan, B. A Framework for Heritage-Led Regeneration in Chinese Traditional Villages: Systematic Literature Review and Experts’ Interview. Heritage 2025, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianjun, D. Revitalization of Old Revolutionary Base Areas: Challenges, Opportunities and Pathways—Based on a 5D analytical framework. China Econ. 2024, 19, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, T.; Shen, N.; Guan, M.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, H. Resource and Environment Constraints and Promotion Strategies of Rural Vitality: An Empirical Analysis of Rural Revitalization Model Towns. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 956644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaćina, R.; Bajić, S.; Dimitrijević, B.; Šubaranović, T.; Beljić, Č.; Bajić, D. Application of the VIKOR Method for Selecting the Purpose of Recultivated Terrain after the End of Coal Mining. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2024, 77, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Feng, S.; Li, P.; Wang, A. Ecological Restoration and Regeneration Strategies for the Gumi Mountain Mining Area in Wuhan Guided by Nature-Based Solution (NbS) Concepts. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catur, D.; Arifin, A. Environmental Rehabilitation of Industrial Area Challenges and Solutions Toward a Green Economy. KnE Soc. Sci. 2025, 10, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampus, M. Life in the ruins of a post-mining landscape: The co-constitutive character of human and non-human action in land restoration. Swed. J. Anthropol. 2024, 7, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurkovich, J. Recipe for a New Life in Post-Industrial Areas. J. Herit. Conserv. 2022, 69, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kostenko, T.; Bohomaz, O.; Hlushko, I.; Liashok, N. Use of solid mining waste to improve water retention capacity of loamy soils. Min. Miner. Depos. 2023, 17, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krodkiewska, M.; Łozowski, B.; Sierka, E.; Nadgórska-Socha, A.; Woźnica, A.; Feist, B.; Babczyńska, A. Artificial Water Bodies in Post-Industrial and Urban Landscapes—A Case Study on Assessing Their Potential in Blue–Green Urban Infrastructure. Water 2025, 17, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovych, V.; Skrobala, V.; Tyndyk, O.; Kaspruk, O. Hydro-ecological monitoring of heavy metal pollution of water bodies in the Western Bug River basin within the mining-industrial region. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, R.; Braiden, H. Restorative Experiences of Regenerative Environments: Landscape Phenomenology and the Transformation of Post-Industrial Spaces into Re-Naturalized Public Places. Environ. Soc. 2024, 15, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, H.; Khakzand, M. Eco-Revelatory: The Missing Link in the Development of Adaptive Landscape to Industrial Heritage Sites. Herit. Soc. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk-Świątek, A. Sustainable Transformation of Post-Mining Areas: Discreet Alliance of Stakeholders in Influencing the Public Perception of Heavy Industry in Germany and Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T.M.; Heuschkel, Z.; Dorn, C.; Stabel, A.A.; Lohrberg, F. From Mining–Recultivation Towards Urban Agriculture Strategies: Learning from Informal Planning with Thematic Focus in the Rhenish Mining Area. In Productive Processes: Sustainable Transitions for Urban Industrial Lands = Produktive Prozesse: Nachhaltiger Wandel Urbaner Gewerbegebiete; Chang, R.A., Förster, A., Gärtner, S., Kohlhas, L., Eds.; RWTH Aachen University: Aachen, Germany, 2023; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klute, J.; Kenway, P. Structural Change and Industrial Politics in the Ruhr Region; Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/engl/9-23_Onl-Publ_Structural_Change.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Popelková, R.; Mulková, M. The mining landscape of the Ostrava–Karviná coalfield: Processes of landscape change 1830s–21st century. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 90, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, L.; Schmitz, S. The sense of place of local mining heritage in Wallonia. Herit. Soc. 2023, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwińska, K. About Coal Differently: A Reinterpretation of the Post-Industrial Heritage of Upper Silesia in the Context of Socially Engaged Design. In Silesia Superior: Narratives on Upper Silesia–The Multitude of Perspectives; Dampc-Jarosz, R., Kowalczyk, A., Sadzikowska, L., Eds.; V&R Unipress: Göttingen, Germany, 2024; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin, F.; Szcześniak, M. (Eds.) Visual Culture of Post-Industrial Europe; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, Y. The Construction of Cultural Gene Map and Revitalization Strategies for Industrial Heritage: A Case Study of Hanyang Ironworks in Wuhan. MAJ Malays. Archit. J. 2025, 7, 176–192. [Google Scholar]

- Toura, V. Rethinking Creativity at Neighborhood Level in the Post-Industrial ERA. The case studies of two urban voids redevelopments in France: Ile-de-Nantes and Docks-de-Seine. In Proceedings of the Grand Projects–Urban Legacies of the late 20th Century, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–19 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hajduková, R.; Sopirová, A. Typology of Terrain Vague and Emergence Mechanisms in Post-Communist, Post-Industrial Small and Medium-Sized Towns in Slovakia: Case Study of Humenné, Strážske and Vranov and Topľou. ALFA Archit. Pap. Fac. Archit. Des. 2023, 28, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwin, W.; Raab, T.; Birkhofer, K.; Hinz, C.; Letmathe, P.; Leuchner, M.; Roß-Nickoll, M.; Rüde, T.; Trachte, K.; Wätzold, F.; et al. Perspectives of lignite post-mining landscapes under changing environmental conditions: What can we learn from a comparison between the Rhenish and Lusatian region in Germany? Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, V.; Svarcova, V.; Hendrychova, M.; Vondrakova, L. Water quality of reclaimed lakes in post-mining locations of Czech Republic. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzior, A.; Grebski, W.; Kwilinski, A.; Krawczyk, D.; Grebski, M.E. Revitalization of Post-Industrial Facilities in Economic and Socio-Cultural Perspectives—A Comparative Study between Poland and the USA. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylong, K. Rewitalizacja terenów pokopalnianych w Zagłębiu Dąbrowskim. Builder 2024, 327, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starostwo, B. Zabytkowa Cementownia Grodziec. Available online: https://starostwo.bedzin.pl/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Lipiński, R. Cementownia Grodziec. Available online: https://Blog.Architekt.Bedzin.Pl/Cementownia-Grodziec (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Sobierajski, P. Zabytkowa Cementownia Grodziec W Będzinie Uratowana. Miasto Dostało Rekordowe 72 Mln Zł Dofinansowania Na Ogromny Projekt. Available online: https://Dziennikzachodni.Pl/Zabytkowa-Cementownia-Grodziec-W-Bedzinie-Uratowana-Miasto-Dostalo-Rekordowe-72-Mln-Zl-Dofinansowania-Na-Ogromny-Projekt/Ar/C3-18942663 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Historia w Sieci—Saturn. Available online: https://Muzeum-Saturn.Czeladz.Pl/Historia-W-Sieci-Saturn/ (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Babak, M. Czeladź Zrewitalizowała Cechownię Dawnej Kopalni Saturn. Available online: https://Dzieje.Pl/Dziedzictwo-Kulturowe/Czeladz-Zrewitalizowala-Cechownie-Dawnej-Kopalni-Saturn (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Sobierajski, P. W Czeladzi Powstaje Pierwszy, Kryty Miejski Basen. Pływalnia Na Terenie Byłej Kopalni Saturn Z Historyczną, Unikatową Architekturą. Available online: https://Bedzin.Naszemiasto.Pl/W-Czeladzi-Powstaje-Pierwszy-Kryty-Miejski-Basen-Plywalnia-Na-Terenie-Bylej-Kopalni-Saturn-Z-Historyczna-Unikatowa-Architektura/Ar/C1p2-27341897 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Sobierajski, P. Kopalnia Saturn W Czeladzi Fedrowała Ponad 100 Lat. Takich Zdjęć Z Jej Wnętrza Jeszcze Nie Widzieliście. ‘Będą Pamiątką’. Available online: https://dziennikzachodni.pl/kopalnia-saturn-w-czeladzi-fedrowala-ponad-100-lat-takich-zdjec-z-jej-wnetrza-jeszcze-nie-widzieliscie-beda-pamiatka/ar/c1p2-27402895 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Panusch, P. Kopalnia Saturn I Gsw Elektrownia. Available online: https://Www.Poznajhistorie.Pl/Monument/Czeladz-Kopalniasaturn (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Jaguś, A.; Rzętała, M. Znaczenie Zbiorników Wodnych W Kształtowaniu Krajobrazu (Na Przykładzie Kaskady Jezior Pogorii); Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Techniczno-Humanistycznej w Bielsku-Białej: Bielsko-Biała, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jeziora Pogoria. Available online: https://Www.Slaskie.Travel/Poi/3800/Zespol-Sztucznych-Zbiornikow-Wodnych-Pogoria-I-Iii (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Pogoria II-Dzikie Oblicze Pojezierz. Available online: https://www.dabrowa-gornicza.pl/aktualnosci/pogoria-ii-dzikie-oblicze-pojezierza/#:~:text=Pogoria%20II%2C%20spo%C5%9Br%C3%B3d%20wszystkich%20zbiornik%C3%B3w%20tzw.%20pojezierza%20d%C4%85browskiego%2C,si%C4%99%20siedliskiem%20wielu%20gatunk%C3%B3w%20ryb%2C%20ptak%C3%B3w%20i%20ro%C5%9Blin (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Machowski, R.; Rzętała, M. Zbiornik Pogoria III. Available online: https://Ibrbs.Pl/Index.Php/Zbiornik_Pogoria_III (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Machowski, R. Zbiornik Pogoria I. Available online: https://Ibrbs.Pl/Index.Php/Zbiornik_Pogoria_I (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Mirkowski, Z. Pogorie Są Jednym Z Największych Skarbów Dąbrowy Górnicze. Available online: https://Www.Dabrowa-Gornicza.Pl/Aktualnosci/Pogorie-Sa-Jednym-Z-Najwiekszych-Skarbow-Dabrowy-Gorniczej/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Piernikarczyk, A. Skała Rzędowa w Bzowie. Available online: https://www.polskieszlaki.pl/skala-rzedowa-w-bzowie.htm (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Majgier, L.; Badera, J.; Rahmonov, O. Kamieniołomy w województwie śląskim jako obiekty turystyczno-rekreacyjne na terenach uprzemysłowionych. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2010, 27, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Skreczko, S.; Wolny, M. Wykorzystanie nieczynnych kamieniołomów na wybranych przykładach obszaru Jury Krakowsko-Częstochowskiej. Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kult. 2014, 26, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Todur, W. Sosnowiec. Zapomniany Symbol Sosnowca. Hałda Huty Katarzyna. Available online: https://sosnowiec.wyborcza.pl/sosnowiec/7,93867,26995365,zapomniany-symbol-sosnowca.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Jurkiewicz, K. Huta Katarzyna Ocalona Od Centrum Logistycznego. Panattoni Nie Wybuduje Tutaj Hal. Czy Powstanie Tu Osiedle Mieszkaniowe? Available online: https://Sosnowiec.Naszemiasto.Pl/Huta-Katarzyna-Ocalona-Od-Centrum-Logistycznego-Panattoni/Ar/C1-8547309 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Ciepiela, B. Tradycje Zagłębiowskiego Górnictwa; Stowarzyszenie Inżynierów I Techników Górnictwa Koło “Zagłębie”; Stowarzyszenie Autorów Polskich Oddział W Będzinie: Będzin, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Przemsza-Zieliński, J. Historia Zagłębia Dąbrowskiego, 1st ed.; Związek Zagłębiowski: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik, R. Zagłębie Dąbrowskie. Available online: https://Ibrbs.Pl/Index.Php/Zagłębie_Dąbrowskie (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Bielecki, P. Krótka Historia o Zagłębiu Dąbrowskim; FdZD: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Z.M.; Zhang, X. Identifying the role of industrial heritage in the European Capital of Culture programme. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J. Rethinking industrial heritage tourism resources in the EU: A spatial perspective. Land 2023, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbread-Abrutat, P.; Kendle, A.; Coppin, N. Lessons for the mining industry from non-mining restoration. In Proceedings of the 8th International Seminar on Mine Closure, Cornwall, UK, 18–20 September 2013; pp. 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberman, R.; Ostręga, A. Reclamation and revitalization of lands after mining activities—Polish achievements and problems. AGH J. Min. Geoengin. 2012, 36, 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Susmiyati, H.R. Legal construction of post-mining reclamation in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Joint Symposium on Tropical Studies, online, 7–8 July 2021; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, B.; Baker, C.D. Mine Reclamation Planning in the Canadian North; Canadian Arctic Resources Committee: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak, A. Rewitalizować czy adaptować obiekty pogórnicze—rozważania teoretyczne. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. 2009, 25, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mérai, D.; Veldpaus, L.; Pendlebury, J.; Kip, M. Governance context for adaptive heritage reuse. Hist. Environ. 2022, 13, 526–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCAS. Analiza Wsparcia Terenów Poprzemysłowych, Zdewastowanych, Zdegradowanych w Województwie Śląskim. 2024. Available online: https://rcas.slaskie.pl/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Karyono, I.; Santiago, F. Post-mining land reclamation under Regulation No. 78/2010. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Energy and Mining Law (ICEML 2018), Jakarta, Indonesia, 18–19 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Hu, Z.; Fu, Y. Zoning of land reclamation in coal mining areas—New progress. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2014, 1, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasztelewicz, Z. Approaches to post-mining land reclamation in Polish lignite mining. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2014, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.