Abstract

Background: Lavandula stoechas and Artemisia absinthium essential oils (EOs) were evaluated as natural antimicrobial and repellent agents. Methods: The chemical composition was determined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The antibacterial activity was evaluated by agar diffusion method, and the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were determined for antifungal activity, while the repellent effect against mill moth was tested by fumigation. Results: Camphor was the main component in both EOs, accounting for 31.83% of L. stoechas and 41.92% of A. absinthium. In antibacterial assays, both EOs showed very good activity against Gram-positive bacteria, with inhibition zone diameters (IZDs) higher than 15 mm, and average activity against Gram-negative bacteria, with IZDs ranging from 8 to 14 mm. The EOs reduced Aspergillus niger mycelial growth by 61% to 80% for LsEO and 50% to 61% for AaEO at concentrations ranging from 1 to 3 mg/mL. The oils exhibited variation in repellent and insecticidal potential, with L. stoechas showing higher activity, while both had an impact on development and fecundity of Ephestia kuehniella. Conclusions: Thus, the two EOs may be effective as biological and sustainable alternatives to conventional chemical products for food preservation.

1. Introduction

The Algerian territory is part of the Mediterranean biome and is characterized by a rich range of wild and cultivated legumes which, along with cereals, are essential components of the Algerian diet [1,2]. However, pulses rapidly deteriorate due to oxidation, insect infestation, or microbial activity, which can harm human health when stored under unfavorable conditions [3,4,5,6,7].

Currently, the most common method used to protect these food products involves the application of synthetic preservatives such as fungicides and bactericides, owing to their ease of use. Nevertheless, the use of these synthetic substances is increasingly being questioned because of the potential health risks they present, including contamination of the biosphere and the food chain [8], carcinogenic and teratogenic effects, and prolonged degradation periods [9]. This situation has driven consumers to seek more natural foods and encouraged scientific researchers to explore non-toxic, natural additives.

In this context, researchers have turned their attention to medicinal and aromatic plants, which represent a valuable heritage for humanity in terms of primary healthcare and subsistence. The use of these plants as natural antimicrobials and antioxidants is generating growing interest due to their secondary metabolites [3,4,6,10,11]. These compounds offer a wide diversity of chemical structures with a broad range of biological activities, making medicinal plants promising potential sources of drugs.

Intending to propose an alternative to synthetic food preservatives and enhance the flora of Algeria’s Eastern Numidia region, this study focuses on the antimicrobial and repellent properties of essential oils from two aromatic and medicinal plant species. Both species grow naturally in the El-Tarf region and are widely used in traditional medicine: Lavandula stoechas (Lamiaceae) and Artemisia absinthium (Asteraceae).

L. stoechas, locally known as “Helhela,” is used as an expectorant, antispasmodic, wound disinfectant, and for dermatological issues. It possesses antimicrobial, anticancer, sedative, antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, and insecticidal properties. A. absinthium, commonly known as wormwood or bitter mugwort (locally “Chajret meriem” or “Chiba”) [12], is primarily valued for its antimicrobial [13], antioxidant [14], antifungal [15], antidepressant [16,17], and neuroprotective properties [18].

The exploration of plant-derived essential oils as natural alternatives aligns with the principles of sustainability by promoting eco-friendly solutions. The overuse of synthetic preservatives and pesticides poses significant environmental and health risks, including ecosystem contamination and the emergence of resistant pathogens. In contrast, essential oils offer a path toward sustainable, biodegradable, and non-toxic solutions for food preservation and pest control.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the chemical composition and evaluate the antimicrobial and repellent properties of essential oils from the aerial parts of L. stoechas and A. absinthium. This work prospects the development of a highly sustainable plant-based product that could be derived from renewable agriculture in North Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Extraction of Essential Oils

The plants were harvested following the Good Agricultural and Collection Practices recommended by the World Health Organization. A total of 1800 g and 2500 g of aerial parts (Flowers and leaves) of L. stoechas and A. absinthium, respectively, were freshly collected during their growing and flowering period (March to June) in the province of El-Tarf (Northeast Algeria).

In order to extract the essential oils, the aerial parts of both plants were air-dried at low temperatures (8–10 °C), in the shade, for 15 days. Samples of 100 g of the dried material were then subjected to hydrodistillation using a Clevenger-type apparatus (Glassco, Haryana 133104, India) for 2 h. The obtained essential oils were dehydrated using anhydrous sodium sulfate, and then stored in sealed dark glass vials at 4 °C until use [19].

2.2. Determination of the Chemical Composition of Essential Oils by GC-MS

The characterization of EOs was performed using the GC-MS system Agilent Technologies 7890B GC System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), coupled with an Agilent Technologies 5977A MSD mass spectrometry module. The column temperature was initially set at 60 °C and held constant, then gradually increased to 230 °C, over 45 min at a rate of 2 °C/min. An Agilent HP-5ms low-polar column (60 m × 0.22 mm, 0.25 µm) was employed. The injection was automated with a volume of 2 µL of a solution 1:100 essential oil in hexane. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The pressure is maintained at 25 psi (equivalent to 1.72 bar). The detector is equipped with a quadrupole filter and uses electron ionization. The filament energy is 70 eV, with a temperature of 280 °C. The mass range analyzed spans from 35 to 350 atomic mass units (amu). The identification of the various compounds present in the essential oil was accomplished by comparison of retention time (RT) with standard values of known molecules and by matching their mass spectral data with NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) libraries [20].

2.3. Bacterial Strains

The tested bacterial strains were provided by the microbiology laboratory of the Faculty of Medicine in Annaba (Algeria). The targeted strains were carefully selected due to their high propensity for contaminating food products and their pathogenicity. Some of these strains are from the reference collection ATCC (American Type Culture Collection), while others were isolated from samples collected from individuals suffering from various infections, including food poisoning, and stool cultures. The isolates were identified by API gallery, and all strains were stored at −18 °C until use.

The tested Gram-positive bacterial panel included Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) ATCC 43300, Enterococcus faecalis, and Bacillus cereus.

The Gram-negative bacteria selected for the assays consisted of reference strains Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, alongside an Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli strain. The panel was supplemented witha clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

2.4. Antibacterial Activity of the Essential Oils

The antibacterial activity of the EOs was determined using the agar diffusion method as follows: the bacterial strains were cultured in Muller Hilton broth (MHB) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The turbidity of the cultures was then adjusted to 108 CFU/mL using the 0.5 Mc Farland standards. Discs impregnated with 10 µL of crude essential oil, were placed on the surface of the MHA (Mueller-Hinton Agar) medium, which had been pre-inoculated with a standardized bacterial suspension (108 CFU/mL). The Petri dishes were then sealed and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The inhibition zonediameters were measured, and the results are expressed as the mean of the three-test results ± standard deviation.

2.5. Determination of Fungal Activity of Essential Oils

The antifungal activity of the essential oils was initially tested against Aspergillus niger (Microbiology Laboratory at the University of Tebessa, Algeria). The pathogenic fungus was selected due to its well-known ability to infest stored grains and its resistance to most commonly used synthetic antifungal treatments.

The pathogenic fungus A. niger was cultured on fresh potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates at laboratory temperature until sporulation was observed, prior to the experiment. Different dilutions of EOs were prepared in DMSO, and 500 µL of each dilution was mixed with 9.5 mL molten PDA to prepare various concentrations ranging from 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mg/mL. This mixture was vortexed and then poured into sterile Petri dishes. The center of each solidified medium was inoculated upside down with 6-mm square mycelial plugs cut from the periphery of 5-day-old cultures. Positive controls were simultaneously run with DMSO and without EO. The plates were incubated for 9 days at 28 °C. During this period, the fungal growth was assessed daily by measuring the average of the two perpendicular diameters of each colony, and growth curves were carried out. The lowest concentration of each EO that completely prevented visible fungal growth and allowed a revival of fungal growth during the transfer experiment was considered the MIC for that EO [21]. In order to ascertain the effect of each EO concentration on the fungal growth, percentages of inhibition were calculated after 9 days of incubation, according to the following formula:

where Ø is the diameter (mm) of the mycelium.

2.6. Insect Rearing

Ephestia kuehniella (mill moth) larvae were obtained from untreated infected soft wheat flour and reared in the laboratory at 25 ± 3 °C, 50 ± 5% relative humidity, with a light/dark cycle of 8 h (light): 16 h (dark) in disinfected flour. The insect was identified by Fourth instar larvae from the next generation were collected from the stock colony and used for the tests. All experiments were conducted under the same environmental conditions. The insect has been recognized as a common pest of stored grains, particularly flour, with rapid development in the Mediterranean regions.

2.6.1. Repellent Effect of Essential Oils

The repellent effect was tested by fumigation using essential oils at their pure concentration under controlled laboratory conditions. A circle of Whatman paper (No. 3) with a diameter equivalent to that of a Petri dish (9 cm in diameter) was cut in half. One half of the circle was impregnated with pure essential oil (500 µL), while the other half remained untreated. Ten fourth-instar larvae were placed in the center of the Petri dish. The number of insects present on each side of the paper was counted every 30 min for 2 h. This approach allows the repellent efficacy of essential oils to be measured based on the distribution of larvae and provides relevant data on the duration and extent of the repellent effect. The repellent percentage (RP) is calculated as follows:

where NC is the number of insects present on the untreated side of the paper, and NT is the number of insects present on the side treated with pure essential oil. The data of average repellent percentage after 2 h of exposure is calculated, and the oil activity is classified into one of the different repellent classes according to the ranking system proposed by McDonald et al. [22].

2.6.2. Toxicity Activity

To evaluate the toxicity of essential oils extracted from the tested plants (A. absinthium and L. stoechas), different concentrations of each oil (120, 200, 280, 360, and 500 µL/L) were applied to a 3 cm diameter filter paper, which was attached to the underside of the vial lid. Ten individuals from each developmental stage, including newly emerged adults and 4th larval stage were placed in 370 mL glass vials, with 100 g of flour added as larval food. The vials were hermetically sealed, and the experiment was conducted at a temperature of 25 ± 3 °C with a relative humidity of approximately 50%. Each concentration was tested in five replicates, along with a control group that received no treatment. Larvae and adults were exposed to the different oil concentrations for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, and the mortality rate was recorded.

The observed mortality was corrected using Abbott’s formula, which accounts for natural mortality and determines the actual toxicity of the essential oils [23]:

where Mt is the mortality in treated groups; Mc is the mortality in the control group. The lethal concentrations for 50% mortality (LC50) and 25% mortality (LC25) were determined using the GraphPad Prism 7 software.

2.6.3. Insecticidal Activity on Insect Development

The lethal concentrations LC50 of L. stoechas and A. absinthium, determined on larvae after 24 h and 96 h of treatment in the toxicity test, were applied to a 3 cm diameter filter paper, which was attached under the lid of the vial. Ten last-instar larvae were placed in 125 mL glass vials, and 100 g of flour were added for feeding. The experiment was conducted under the same conditions as the toxicity test. Five replicates were performed for each concentration, along with a control group that received no treatment. The larvae were exposed to LC50-24 h/24 h and LC50-96 h/96 h. After treatment, the treated larvae were placed in a new plastic box containing 100 g of clean flour. The experiment was conducted at a temperature of 25 ± 3 °C and a relative humidity of approximately 50%. The development of treated and untreated larvae was monitored based on several parameters, including:

- % Pupal Formation: Determined by the number of larvae that transform into pupae relative to the total number of larvae, multiplied by 100%.

- % Adult Emergence: Determined by the number of adults that emerges relative to the total number of pupae, multiplied by 100%.

- Average Adult Lifespan: Determined by the lifespan (in days) of adults that survived the treatment.

- Female Fecundity: Determined by the total number of eggs laid by a female during the oviposition period.

The observed mortality percentages in larvae and pupae were corrected using Abbott’s formula [13], as described in the toxicity test.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The t-test was used to compare the antibacterial activity of both EOs, using SPSS 25, with a statistical significance set at p < 0.05. The homogeneity of variance for insecticidal and antifungal activity comparisons was verified using the Brown-Forsythe test to confirm the validity of analyses. A one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were applied to identify significant differences between groups. Data analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA, USA, 2016).

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils

The essential oil yields (w/w) obtained from the aerial parts of L. stoechas and A. absinthium were 1.02% and 0.88%, respectively. The composition of the EOs is presented in Table 1. The GC-MS analysis identified 44 volatile constituents in L. stoechas essential oil (LsEO). The major components were camphor (31.83%) and Fenchone (11.34%) followed by D-Limonene (5.58%), β-Guaiene (5.05%), Camphene (4.69%) and Bornyl acetate (3.93%). Concerning A. absinthium essential oil (AaEO), the major components were Camphor (41.92%) and Chamazulene (20.19%) followed by Terpinen-4-ol (9.29%) and γ-Terpinene (3.88%).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of L. stoechas and A. absinthium essential oils.

3.2. Antibacterial Activity

The results of the agar disc diffusion method were interpreted according to the following criteria [9]: inhibition zones > 15 mm indicate very good activity, diameters between 8–15 mm indicate moderate activity, and diameters < 8 mm indicate weakactivity. Thus, both EOs were remarkably more active against Gram-positive bacteria, with IZDs ranging from 8.1 to 25.3 mm, than Gram-negative bacteria, whose IZDs varied from 7.1 to 15.3 (Table 2). However, the statistical test t revealed that LsEO was slightly better (p = 0.041) than AaEO.

Table 2.

Inhibition zone diameters (mm) of LsEO and AaEO.

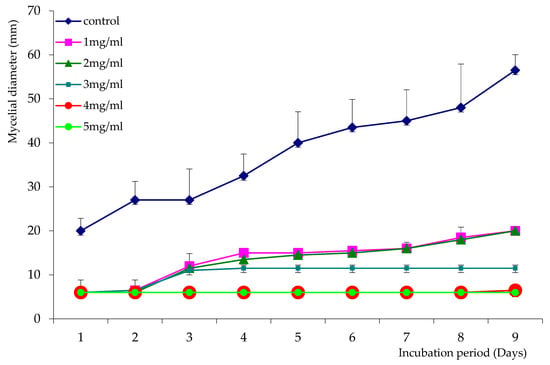

3.3. Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils

The growth of Aspergillus niger over nine days in the presence of L. stoecas and A. absinthium essential oils, at different concentrations, is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The results showed that mycelial growth increases with incubation time. However, mycelial diameter decreased considerably with the increasing concentrations of essential oils, compared to the control. The essential oil of L. stoechas showed good antifungal activity against A. niger by reducing mycelial growth after 3 days of incubation with low concentrations (1 and 2 mg/mL) and causing growth arrest at a concentration of 3 mg/mL, whereas no growth was observed at concentrations of 4 and 5 mg/mL (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Growth curves of Aspergillus niger in the presence and absence of LsEO.

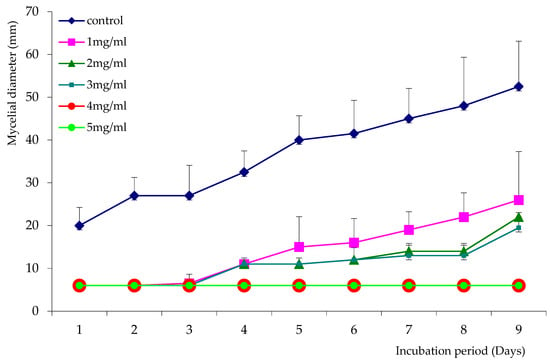

Figure 2.

Growth curves of Aspergillus niger in the presence and absence of AaEO.

The essential oil of A. absinthium was able to retard the growth of A. niger for 3 days, even at low concentrations (1 mg/mL). Moreover, mycelial growth was considerablyreduced after 3 days of incubation at concentrations of 2 and 3 mg/mL and completely absent at concentrations of 4 and 5 mg/mL (Figure 2).

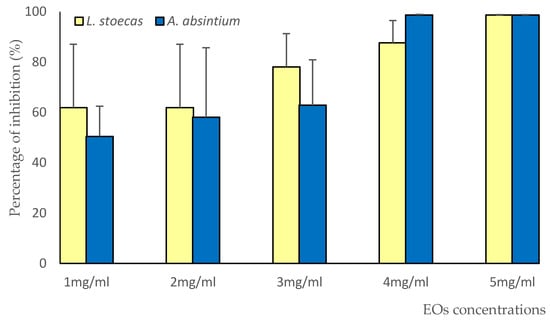

We can conclude from the growth curves that the concentration of 4 mg/mL was the MIC for both tested essential oils. The ability of the two essential oils to reduce A. niger growth was confirmed by the percentages of inhibition shown in Figure 3. These EOs were able to reduce A. niger mycelial growth by 61% to 80% for LsEO and 50% to 61% for AaEO, at concentrations ranging from 1 to 3 mg/mL. In addition, growth was totally inhibited at concentrations of 4 and 5 mg/mL for A. absintium.

Figure 3.

Percentages of inhibition of LsEO and AaEO against Aspergillus niger.

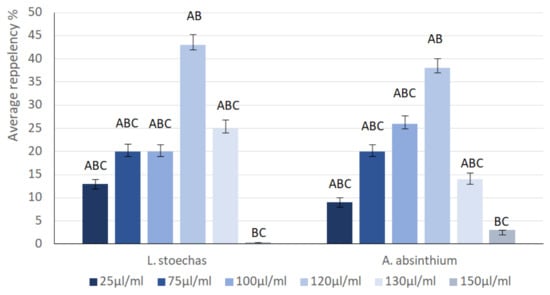

3.4. Determination of the Repellent Activity of Essential Oil

Essential oils extracted from L. stoechas and A. absinthium were tested on E. kuehniella at various concentrations (25, 50, 75, 100, 120, 130, and 150 µL/mL) for their repellent effects (Figure 4). The average repellency at the lowest concentration of 25 µL/mL displays a value of 13% for LsEO and 9% for AaEO. A maximum repellency of 43% was recorded at a concentration of 120 µL/mL for L. stoechas, reflecting a moderately repellent effect, while for A. absinthium, 38% repellency was recorded at 120 µL/mL, indicating a weakly repellent effect, according to McDonald’s (1970) repellency classification. Moreover, the statistical test showed a significant (p = 0.02) difference between the two EOs. Generally, the repellency rate increases with increasing concentration of both oils. However, at concentrations of 120 µL/mL and 130 µL/mL, the repellency rate begins to decrease for LsEO and AaEO, respectively.

Figure 4.

Repellent activity of L. stoechas and A. absintium essential oil on E. kuehniella at different concentrations (n = 3 replicates, each containing 10 larvae). The means that do not share any letter are significantly different between concentrations for each plant.

3.5. Determination of the Essential Oils Insecticidal Activity

Adults exposed to volatile compounds from both essential oils did not survive the treatment. Total lethality (100%) was recorded within the first 24 h at the lowest concentration (120 µL/L air). Consequently, LC50 and LC25 were not determined on adults. Impact of both EOs on larvae showed significant differences between concentrations. We detected no mortality in the control groups.

The toxicity of the essential oils against E. kuehniella larvae and adults is presented in Table 3. Mortality increased with concentration, with significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s test. After 24 h, L. stoechas EO showed the highest larvicidal activity, causing 10.20% mortality at 120 µL/L and 34.69% at 500 µL/L, whereas A. absinthium EO exhibited weaker effects (4% at 280 µL/L and 12.24% at 500 µL/L).

Table 3.

Corrected mortality percentage of E. kuehniella larvae after different periods of exposure to the EOs (mean ± SEM, n = 5 replicates, each containing 10 larvae).

After 48 h, mortality continued to rise with both concentration and exposure time. L. stoechas EO induced 26.53% mortality at 120 µL/L and 65.3% at 500 µL/L, while A. absinthium EO reached 34.69% at the highest concentration. Probit analysis showed LC25 values of 330 and 701.8 µL/L and LC50 values of 860.8 and 1086 µL/L for L. stoechas and A. absinthium, respectively, after 24 h. After 48 h, LC25 decreased to 133.1 and 435.8 µL/L, and LC50 to 375.2 and 604 µL/L (Table 4).

Table 4.

Probit analysis (LC25 and LC50) of the toxicity of L. stoechas and A. absinthium essential oils against last-instar larvae of E. kuehniella after different periods of exposure to the treatment (mean ± SEM, n = 5 replicates, each containing 10 larvae).

After 72 h, mortality further increased. L. stoechas EO caused 38.64% mortality at 120 µL/L and 84.09% at 500 µL/L, while A. absinthium EO caused 55.56% mortality at the highest concentration. LC25 values were 85.71 and 288 µL/L, and LC50 values were 221.7 and 420 µL/L for the two oils, respectively (Table 4).

After 96 h, mortality continued to rise. At 120 µL/L, L. stoechas and A. absinthium EOs caused 45.45% and 12.20% mortality, respectively. At 500 µL/L, A. absinthium EO induced 78.07% mortality, with an LC50 of 365.2 µL/L (Table 4).

3.6. Impact on the Development of E. kuehniella After Larval Treatment at LC50

The fate of E. kuehniella larvae treated with essential oils at LC50-24 h and LC50-96 h is mentioned in Table 5. Exposure of final instar larvae to lethal concentrations LC50 did not have an immediate impact on the entry of treated larvae into the pupal phase. A rate of 100% and 80% of formed pupae were recorded after receiving treatment at the larval stage with LC50-24 h of L. stoechas and A. absinthium oil, respectively. However, both essential oils had later repercussions on the development and reproduction of treated larvae. Blocked adult emergences were reported at a rate of over 70% in larvae treated with LC50-96 h of both essential oils, and at a rate of over 90% after treatment with LC50-24 h of both tested essential oils. The negative impact of these two essential oils extended to the lifespan and reproduction of adults that survived the treatment. Emerged adults recorded an average lifespan of 1 to 2 days compared to untreated adults with an average lifespan of 13 to 14 days. Indeed, the reproduction, specifically the fecundity of females that underwent treatment at their larval stage, is null compared to untreated females (140.1 eggs/female).

Table 5.

Impact of Essential Oils on the Development parameters and fecundity of E. kuehniella After Larval Treatment at LC50 (mean ± SEM, n = 5 replicates, each containing 10 larvae).

4. Discussion

The GC-MS analysis revealed that the composition of LsEO is slightly different from that of the essential oils described in many other Algerian regions like Tlemcen, Skikda, Blida, Medea, and Chlef, as well as in Tunisia, where Fenchone (11.3–68.2%) was more predominant than Camphor (8.7–18.1%) [24]. On the other hand, a very recent study from Morocco reported a chemical profile similar to our results with Camphor (24.35%) and Fenchone (9.58%) as major compounds [25]. Thus our LsEO can be attributed to the camphor chemotype, although the Fenchone/Camphor chemotype, remains the most commonly identified [19,26,27]. Another characteristic of our LsEO is the absence of 1,8-Cineole, one of the main compounds of Lavandula EOs. The absence of this compound can be explained by genetic (degree of hybridization) and evolutionary factors (different maturing stages of flowers). Indeed, Insawang et al. [28] reported that it was possible that the high production of 1,8-cineole (33.86%) in L. stoechas × viridis ‘St. Brelade’, is a genetic trait inherited and transmitted by L. viridis, as this compound was only detected in the L. viridis essential oil, but not in the essential oils of the L. stoechas cultivars. Regarding the influence of the evolution stage of the plant on the composition of its EO, Guitton et al. [29] observed that the opened flowers presented Linalyl acetate and some sesquiterpenes as the main compounds, suggesting that they may act as attractive molecules for pollinating insects. In contrast, the unopened and faded flowers contained mainly 1,8-Cineole, Ocimene, Limonene, Linalool, and Terpinen-4-ol, indicating a repellent action to protect immature flowers and seeds from harmful insects [16]. Moreover, it must be noted that other factors like environmental conditions, geographical origin, and even the method of extraction are also responsible for the variation of the chemical composition of essential oils [17,18,19].

With regard to AaEO, the chemical profile was very similar to that described by Benkhaled et al. [30] in M’sila (East of Algeria), where Camphor (47.59%), Chamazulene (10.34%) and Terpinen-4-ol (6.35%) were the major compounds followed by γ-Terpinene (2.87). More recently, in the West of Algeria, Lakhdari et al. [31] found the same major compounds in an AaEO from Oran, with slight quantitative differences, and Benchohra et al. [32] reported an AaEO from Sidi Bel Abbes, partially comparable to our EO, with camphor (25.47%) as the main compound. These results confirmed that Algerian A. absinthium has a specific chemotype that is camphor, which exists in northern Algeria, from East to West. The same chemotype was also observed in Brazil, with (19%) of camphor [33]. In contrast, our findings were different from those reported by neighboring countries. Indeed, many studies revealed that Chamazulene chemotype was the most defined in Tunisia [14,34,35]. While in Morocco, Derwich et al. [26] and Houti et al. [36] described two AaEOs where α-thujone (40%) and cis-chrysanthenyl-acetate (30.02%) were the major compounds, respectively. The majority of the chemotypes reported in the literature are based on four compounds: (Z)-β-Epoxyocimene, (Z)-Chrysanthemyl acetate, Sabinyl acetate, and β-Thujone. However, each geographic region has its chemotype, and no correlation between the main component and geographical distribution of the chemotype has been established until now [37]. On the other hand, Houti et al. [36] revealed that the plant’s harvesting period plays a crucial role in the variation of EO composition. Indeed, it was observed that the AaEO harvested in June was richer in Camphor than those collected in March and September.

These changes in some proportion might be explained by the proposed biosynthesis pathways of camphor, through unstable bicyclic monoterpenes (Pinene). In addition, these biosynthesis pathways can be directly influenced by many climatic factors, such as the sun exposure temperature and the amount of precipitation. For example, light is the cornerstone of the development process of growing plants and can trigger the biosynthetic pathways of phenols, terpenoids, and secondary metabolism, as well as direct biosynthesis towards the preferential formation of specific products. All these data show that the chemical composition of AaEO is quite variable according to the period and place of harvest. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the composition of this EO is also affected by other factors, like the method and the plant organ used for the EO extraction [37,38]. Our EOs’ high Camphor concentration makes them more attractive to research for insecticidal and antibacterial properties.

In the context of antibacterial activity, our EOs were particularly active against the Gram-positive bacteria, which is in agreement with many reports. Baali et al. [39] indicated that LsEO was more active against S. aureus (15 mm) than E. coli (13 mm). Yassine et al. [40] showed that the strains of S. aureus and Listeria spp. were more sensitive with IZDs of 17.5 mm and 18.5 mm, respectively, than E.coli (13 mm). Bouyahya et al. [41] confirmed this result by observing that LsEO was much better active against S. aureus and L. monocytogenes than P. aeruginosa. Regarding AaEO, Aati et al. [42] produced the same observations, noting that minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of AaEO against Gram-negative bacteria were much higher than those of Gram-positive ones. More recently, Ksibi et al. [43] reported that AaEO exhibited better activity against S. aureus (23.3 mm) than P. aeruginosa (8 mm).

The lower sensitivity of Gram-negative bacteria to EOs has been attributed to the presence of an outer membrane (OM) surrounding the cell, which restricts the diffusion of hydrophobic compounds, like those of EOs, through the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) wall. While in Gram-positive bacteria, the absence of the barrier effect of the OM, makes them more vulnerable [44]. However, it should be noted that our investigation showed several observations that are clearly distinct from the majority of reports. For example, the resistance of B. cereus for both EOs was in contradiction with other studies, where B. cereus was very sensitive to these EOs as well as other Gram-positive bacteria [32,45].

This finding proved the difficulties of predicting not only the vulnerability of aparticular species but also that of individual strains within the same species to the EOs [35], especially when some species are not identified beyond the genus level.

Concerning the tested Gram-negative strains, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 showed a higher resistance to both EOs than E. coli and K. pneumoniae strains. This could be attributed to the presence of efficient specific efflux mechanisms, which confer intrinsicresistance to EO components [46].

The antibacterial activity of our tested EOs could be attributed to their major compound, camphor. Indeed, El Omari et al. [47] showed that camphor was as active as the crude LsEO. However, some reports suggest that the interactions of this major compound with the other EO components can enhance the antibacterial effect. Karaca et al. [48] investigated the antibacterial action of camphor in combination with EO from another genus of Lavandula called L. latifolia, following the checkerboard method, and the results showed a synergistic and additive effect of this combination against L. monocytogenes and S. aureus. In our study, this aspect could be the reason for the higher activity of LsEO compared to the AaEO. In fact, AaEO was richer in Camphor, its activity was weaker, which demonstrates that the activity of an EO is not only related to the presence of high amounts of an active compound but also to the nature of its interactions with the other EO components.

The most suggested mechanism of action of EOs is that the hydrophobicity of their compounds enables them to interfere with the outer membrane lipids and interact with transmembrane proteins, thereby affecting cell permeability [49]. In addition, these compounds can alter the process of energy generation, thus disrupting various cellular functions. However, it should be noted that the antibacterial activity does not result from a single mechanism, but rather from a cascade of reactions involving the entire bacterial cell [44]. Moreover, in our study, we were able to observe that the action of the EOs on bacteria, could be independent of their resistance mechanisms since the IZDs of the EOs against the reference strains of S. aureus ATCC 25923 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were very close to IZDs of S. aureus (MRSA) strain and E. coli (ESBL). However, further studies including a broader range of well-characterized resistant isolates are required to confirm this observation.

The antifungal activity of LsEO was better than that of other LsEOs collected from different Algerian regions (Skikada, Jijel, Bouira, Blida and Ain Defla), where MICs varied from 4.48 to 6.05 mg/mL against A. niger [26]. However, Zuzarte et al. [50] showed a higher activity of this EO with an MIC of 2.5 µL/mL against the same fungi. Concerning AaEO, the antifungal activity of A. absinthium species is less well explored in Algeria. Nevertheless, Houti et al. [36] reported good activity of an AaEO from Morocco, with MICs varying from 0.03 to 0.2% (v/v) against A. niger.

Similarly to the antibacterial activity, the antifungal effect of our EOs could also be attributed to their major compound. In this respect, Mahilrajan et al. [51] demonstrated that camphor oil was the most effective EO on A. niger, with an MIC of 100 µL/mL. However, the role of the other EO components in this activity should not be neglected. Indeed, Zuzarte et al. [50] revealed that the antifungal activity of the oil LsEO seems to result from a synergistic effect of several compounds since the major compounds, fenchone, and camphor, tested alone showed very low antifungal activity against the referred strains. The antifungal activity of EOs may be due to their ability to disrupt the structure and function of membranes or organelles of fungal cells and/or inhibit protein synthesis. The fungal cell wall is characterized by the presence of chitin, a long linear homopolymer synthesized by chitin synthase. Thus, the inhibition of chitin polymerization may affect cell wall maturation, septum formation, and bud ring formation, by damaging cell division and cell growth [52]. In this context, Anethole inhibited chitin synthase activity in permeabilized hyphae. The essential oil from Citrus sinensis epicarp (composed of limonene at 84.2%) was able to inhibit the growth of A. niger, leading to irreversible deleterious morphological alterations (in particular the loss of cytoplasm in fungal hyphae, and budding of the hyphal tip) [53]. Some studies showed that essential oils could affect mitochondrial effectiveness by inhibiting the action of mitochondrial dehydrogenases, involved in ATP biosynthesis, such as lactate dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, and succinate dehydrogenase. Bakkali et al. [54] demonstrated that the EO of A. herba alba and Cinnamomum camphora caused mitochondrial damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Haque et al. [55] indicated that terpenoids could play a key role in diminishing the mitochondrial functionality, which gives rise to an altered level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ATP generation. Moreover, ATP generation can be affected by the inhibition of the fungal plasma membrane H+ -ATPase, as demonstrated by Ahmad et al. [56], which leads to intracellular acidification and cell death. The capacity of EOs to inhibit protein synthesis in fungal cells could be illustrated by their effect on toxin elaboration. Prakash et al. [57] found that turmeric EO inhibited the aflatoxinbiosynthetic gene expression in A. flavus, mainly by acting on two regulatory genes, aflR and aflS, and secondarily on the structural genes aflD, aflM, aflO, aflP and aflQ. This activity leads to a down-regulation of the transcription level of aflatoxin genes, and a consequent reduction of the production of mycotoxins by the mold. In addition, the inhibition of aflatoxin production may also be due to theinhibition of carbohydrate catabolism in Aspergillus spp. by acting on some key enzymes [58].

It should be noted that the mechanisms proposed in this section are hypothetical and derived from published literature. The absence of mechanistic assays such as membrane integrity or mitochondrial function tests constitutes a limitation of our study. Therefore, these mechanisms remain speculative and require further experimental validation.

In our study, LsEO and AaEO showed moderate and weak repellent activities, respectively, against E. kuehniella. When comparing with the literature, it was found that there are limited studies on the repellent effects of the species L. stoechas, but related species within the Lavandula genus have shown comparable repellent behavior. For example, L. dentata EO demonstrated moderate repellency (~34%) against Callosobruchus maculatus at certain doses [59]. This supports the notion that monoterpenoids in lavender species can confer meaningful repellent properties, even if the effect is not extremely strong. Regarding A. absinthium, our results were inconsistent with those reported by Chaieb et al. [60], where the AaEO showed the highest repellent activity among of three Artemisia species (A. absinthium, A. campestris and A. herba-alba) against Tribolium castaneum, with repelling approximately 90% of the beetles after 2 h of exposure at 0.08 µL/cm2.

Mechanistically, the repellent effect of both oils may be linked to their major volatile compounds. Camphor and similar monoterpenes are known to interfere with insect neuroreceptors, which may explain repellent behavior. In addition, numerous monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes identified in A. absinthium and related species (Sabinene, α-Phellandrene, bicyclic monoterpenes) have been associated with neurotoxic or behavior-modifying effects on insects [61,62].

Although repellency typically increases in a dose-dependent manner, several mechanisms may explain the reduction recorded at 120 µL/mL for L. stoechas and 130 µL/mL for A. absinthium. First, high concentrations of volatile odorants can induce olfactory adaptation/desensitization in insects; prolonged or intense stimulation causes reduced sensitivity of peripheral olfactory receptors and altered neural coding in the antennal lobe, which effectively lowers behavioral avoidance to the same odor stimulus [63]. Second, many plant volatiles and essential oils exhibit a hormetic or biphasic behavioral response, where moderate doses act as repellents, while very high doses produce neutral or even attractive/less-avoidant responses [64]. Third, concentrated EO vapors can have direct neurophysiological effects (transient anesthetic or locomotor-suppressing actions) on insects that reduce their capacity to flee, thereby artifactually lowering measured repellency percentages even though the compound is biologically active [65]. Fourth, physicochemical factors at high loading, including altered volatilization dynamics and microphase behavior of complex EO mixtures, can change the emission profile of active molecules (condensation, slower steady-state release, or rapid depletion of the most active fraction), producing less effective airborne concentrations over the exposure period [66]. Moreover, interactions between EO constituents can shift with dose; at high overall concentration relative proportions and physicochemical interactions can create antagonistic effects (or mask active molecules), so that the whole oil is less active than expected from its major components. The multicomponent nature of EOs and documented synergistic/antagonistic contributions support this explanation [67].

Our moderate repellent percentages (below 50%) might limit the practical application of these EOs as standalone repellents in pest management. Indeed, although essential oils hold promise, their volatility, dose-dependent efficacy, and potential decline in effect at higher concentrations pose challenges. Furthermore, in real-world conditions, the repellent effect may be influenced by factors such as air circulation, application method, and possible habituation of target insects. Thus, future studies should explore formulation strategies (microencapsulation, slow-release systems) to enhance the persistence of repellent activity.

The evaluation of the insecticidal (fumigant) activity of LsEO and AaEO against E. kuehniella showed that both EOs exhibit a moderate fumigant toxicity. The activity of our LsEO was lower than that reported by El Ouali et al. [68], where L. stoechas EO showed stronger toxicity against Anopheles labranchiae larvae. Similarly, El akhal et al. [69] revealed a higher activity of EOs from different species of Lavandula (L. angustifolia and L. dentate) against Culex pipiens Larvae.On the other hand, the toxicity of our AaEO was very low compared to the results reported by Bano et al. [70], where the LC50 values were 42.45, 48.63 and 58.11 μL L−1 air after 24 h and 18.23, 34.32 and 41.16 μL L−1 air after 72 h of exposure, against C. cephalonica, T. castaneum and C. chinensis, respectively. The variations in toxicity between EOs could be attributed particularly to their different chemical profiles and the targeted insect species.

The substantial difference in toxicity between LsEO and AaEO can be largely ascribed to their distinct chemical compositions. Indeed, the LsEO is dominated by Camphor, Fenchone, Camphene, D-Limonene, and other oxygenated monoterpenes. These volatiles are known for their high vapor pressures that facilitate efficient diffusion through insect respiratory systems where they act trough different neurotoxic actions via mechanisms such as acetylcholinesterase inhibition, disruption of neural ion channels. Camphor and Fenchone, which are present in high proportions in our LsEO, are particularly efficient in fumigation because their molecular weights and polarity allow fast evaporation and effective penetration into insect spiracles. Additionally, D-Limonene and Camphene may contribute to the destabilization of insect cell membranes and neural functions [68,71,72]. Given their chemical characteristics, these compounds may disrupt neurotransmission, possibly by interfering with octopamine receptors or AChE (acetylcholinesterase), leading to eventual mortality [73]. This could demonstrate the effective synergistic action of these compounds against insects [74]. Conversely, although our AaEO’s chemical profile showed a higher proportion of Camphor (41.92%), this EO exhibited a weaker fumigant activity. This could be explained by the presence of a large fraction of sesquiterpenes and Azulene-type compounds, most notably Chamazulene (20.19%), which may act more slowly and less effectively via fumigant exposure, because of their lower volatility that reduces their concentration in the vapor phase, thus limiting immediate toxic impact [75]. There may also be antagonistic interactions, where large sesquiterpenes could compete with monoterpenes for volatilization or binding to target sites, thereby reducing their effectiveness [76]. Moreover, Zzulene-type compounds such as Chamazulene may not exert strong neurotoxic or respiratory effects compared with small monoterpenes; their biological activity might instead be more anti-oxidative or anti-inflammatory, as suggested in pharmacological studies. Indeed, A. absinthium EOs have been characterized in other works, and their sesquiterpene-rich profiles have been linked to moderate insecticidal efficacy. For instance, a study on A. absinthium from Tunisia reported bicyclic monoterpenes, bicycloheptanes, naphthalenes, and cycloalkenes as major constituents, and observed moderate fumigant toxicity (LC50 around 142.8 µL/L) against Tribolium castaneum [60].

From an application standpoint, while the raw LsEO and AaEO may not match the potency of some synthetic insecticides, their relatively moderate toxicity combined with their natural origin suggests potential as eco-friendly agents, particularly in storage facilities where continuous fumigation is feasible [77]. However, their volatility and relatively high required concentrations pose challenges. Thus, developing controlled-release formulations (microcapsules, nanoemulsions) or exploring synergistic blends is a promising avenue [78,79].

Exposure of E. kuehniella larvae to LC50 concentrations of LsEO and AaEO produced strong sublethal effects on subsequent development and reproduction. Although pupation was not prevented in most treated larvae, adult emergence and adult fitness were severely impaired; emergence rates fell sharply, adult lifespan was drastically shortened, and female fecundity was effectively null after larval exposure. These findings indicate that exposure to EO vapors at biologically relevant concentrations can produce pronounced delayed and reproductive effects even when immediate mortality is incomplete, which is a pattern frequently reported for essential oils and their constituents [80].

These effects could be attributed to several mechanisms. Many monoterpenes and oxygenated monoterpenes (Camphor, Fenchone, Terpinen-4-ol, 1,8-Cineole) are known to interfere with insect neural and endocrine physiology (including acetylcholinesterase inhibition or modulation of neurotransmitter receptors), leading to impaired feeding, metabolism and development that manifest later as reduced emergence and fecundity. Indeed, it was observed that EOs can inhibit detoxification and metabolic enzymes (such as esterases, glutathione S-transferases, and cytochrome P450s) and acetylcholinesterase in target insects, which both increases susceptibility to toxicants and impairs normal biochemical processes necessary for metamorphosis and reproduction [81]. In addition, some studies showed that reduced adult emergence, shortened lifespan and suppressed egg laying following larval or juvenile exposure could be attributed to cumulative physiological stress, impaired nutrient assimilation, and damage to reproductive tissues or gametogenesis, induced by EOs compounds [59,82].

It should be noted that, even though our study links chemical composition to biological outcomes at the level of whole oils, component-level bioassays (testing pure Camphor, Fenchone, etc.) and biochemical assays (AChE, GST, P450 activity, histological examination of gonads) would be required to confirm causality. Moreover semi-field trials in representative storage scenarios would also clarify whether the observed suppression of emergence and fertility is preserved under realistic ventilation and adsorption dynamics.

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted the potential of L. stoechas and A. absinthium essential oils as natural antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal and repellent agents. Antibacterial tests demonstrated significant efficacy against Gram-positive strains and mycelial growth inhibition of A. niger. The study also demonstrated notable repellent activity against Ephestia kuehniella and a good repercussion impact on insect reproduction. These findings suggest that these essential oils could serve as sustainable eco-friendly alternatives to conventional chemical agents for food preservation and pest control. Our findings underscore the potential of Lavandula stoechas and Artemisia absinthium essential oils as sustainable alternatives to synthetic preservatives and pesticides. By leveraging these plant-derived compounds, we propose a strategy that aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). The adoption of these essential oils could reduce the environmental footprint of agricultural practices, minimize chemical residues in food chains, and support the development of green technologies for pest management. Furthermore, the cultivation and utilization of these plants could enhance local economies by promoting renewable agriculture in North Africa and the Mediterranean area. Future research should focus on scaling up production methods and integrating these oils into commercial applications, ensuring their accessibility and affordability for sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.T. and M.B.; methodology, C.N., F.T. and M.B.; software, C.N., M.F.S., H.B. and M.B.; validation, F.T. and M.B.; formal analysis, N.B., C.N., A.L., S.G., A.D., F.B., K.H. and B.S.; investigation, N.B.; resources, N.B. and M.B.; data curation, N.B. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B., S.G., B.S. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, L.D.B., A.L., N.B., C.N., M.B. and B.S.; visualization, F.T. and M.B.; supervision, F.T., L.D.B. and M.B.; project administration, M.B.; funding acquisition, M.B. and L.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alberto Basset for allowing us to access the equipment in the BIO for IU laboratory of the University of Salento.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Charoukh, S.; Boumendjel, M. La Biodiversité, Défis et Réponses. Exemple de La Région d’Annaba; GIZ; Deutsche Gesellschaftfür Technische Zusammenarbeit: Frankfurt, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-944152-26-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, T.; Zaafour, M.; Boumendjel, M. Ethnomedical Knowledge and Traditional Uses of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants of the Wetlands Complex of the Guerbes-Sanhadja Plain (Wilaya of Skikda in North eastern Algeria). Herb. Med. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delimi, A.; Taibi, F.; Bouchelaghem, S.; Boumendjel, M.; Hennouni-Siakhene, N.; Chefrour, A. Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Activity of Essential Oil of Artemisia herba alba (Asteraceae) against Ephestia kuehniella (Lepidoptera:Pyralidae). Int. J. Biosci. 2017, 10, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lahcene, S.; Taibi, F.; Mestar, N.; Ali Ahmed, S.; Boumendjel, M.; Ouafi, S.; Houali, K. Insecticidal Effects of the Olea europaea Subsp. Laperrinei Extracts on the Flour Pyralid Ephestia kuehniella. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekioua, N.; Boumendjel, M.; Taibi, F.; Samar, M.F.; Mediouni Ben Jemaa, J.; Benaliouch, F.; Negro, C.; Nicoli, F.; De Bellis, L.; Boushih, E.; et al. In Vitro Evaluation of the Insecticidal Effect of Eucalyptus globulusand Rosmarinus officinalis Essential Oils on a Stored Food Pest Ephestia kuehniella (Lepidoptera, Pyralidea). Cell. Mol. Biol. 2022, 68, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, F.; Boumendjel, M.; Moncef, Z.; Omar, S.; Taha, K.; Amel, D.; Safa, A.; Hassiba, R.; Hanène, C.; Nacira, S.; et al. Conservation of Stored Food Using Plant’s Extracts: Effect of Oregano (Origanum vulgaris) Essential Oils on the Reproduction and Development of Flour Moth (Ephestia kuehniella). Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, F.; Boumendjel, M. Conservation et Stockage des Denrées Alimentaires; Editions Universitaires Européennes: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-8417-4151-6. [Google Scholar]

- Laib, I. Etude Des Activités Antioxydante et Antifongiquede l’huile Essentielle Des Fleurs Sèches de Lavandula officinalis: Application Aux Moisissures Des Légumes Secs. Nat. Technol. 2012, 4, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Ban, X.; Zeng, H.; He, J.; Huang, B.; Wang, Y. Chemical Composition and Antifungal Activity of Essential Oil from Cicutavirosa L. Var. Latisecta Celak. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feknous, N.; Boumendjel, M.; Leblab, F.Z. Updated Insights on the Antimicrobial Activities of Allium Genus (A Review). Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 50, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feknous, N.; Boumendjel, M. Natural Bioactive Compounds of Honey and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Czech J. Food Sci. 2022, 40, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeinodehi, A.; Khangholi, S. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil of Artemisia absinthium Growing Wildin Iran. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2008, 11, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslemi, H.R.; Hoseinzadeh, H.; Badouei, M.A.; Kafshdouzan, K.; Fard, R.M.N. Antimicrobial Activity of Artemisia absinthium Against Surgical Wounds Infected by Staphylococcus Aureus in a Rat Model. Indian J. Microbiol. 2012, 52, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msaada, K.; Salem, N.; Bachrouch, O.; Bousselmi, S.; Tammar, S.; Alfaify, A.; Al Sane, K.; Ben Ammar, W.; Azeiz, S.; Haj Brahim, A.; et al. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) Essential Oils and Phenolics. J. Chem. 2015, 2015, 804658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordali, S.; Cakir, A.; Mavi, A.; Kilic, H.; Yildirim, A. Screeningof Chemical Compositionand Antifungal and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oils from Three Turkish Artemisia Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumendjel, M.; Boucheker, A.; Feknous, S.; Taibi, F.; Rekioua, N.; Bouzeraa, N.; Chibi, A.; Feknous, N.; Baraoui, A.; N’har, S.; et al. Adaptogenic Activity of Cinnamomum camphora, Eucalyptus globulus, Lavandula stoechas and Rosmarinus officinalis Essential Oil Used in North-African Folk Medicine. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2021, 67, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A.; Ansaroudi, F.; Nabavi, S.F.; Nabavi, S.M. Antidepressant and Antioxidant Activities of Artemisia absinthium L. at Flowering Stage. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 7170–7175. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, K.S.; Sharma, A. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Potential of Artemisia absinthium Linn. and Artemisia asiatic Nakai: A Review. J. Pharm. Res. 2010, 3, 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Zoubi, Y.E.; El-Akhal, F.; Berrada, S.; Maniar, S.; Bekkari, H.; Lalami, A.E.O. Struggle against Bacterial Diseases: Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil of Lavandula stoechas L. from Morocco. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2016, 36, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Steam, IL, USA, 2007; Volume 8, ISBN 978-1-932633-21-4. [Google Scholar]

- Puškárová, A.; Bučková, M.; Kraková, L.; Pangallo, D.; Kozics, K. The Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Six Essential Oils and Their Cyto/Genotoxicity to Human HEL12469 Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, L.L.; Guy, R.H.; Speirs, R.D. Preliminary Evalution of New Candidate Materials as Toxicants, Repellents, and Attractants Against Store-Products Insects; Agriculture Research Service; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Washington, DC, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, W.S. A Method of Computing the Effectiveness of an Insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925, 18, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj Mostefa, M.; Kabouche, A.; Abaza, I.; Aburjai, T.; Touzani, R.; Kabouche, Z. Chemotypes Investigation of Lavandula Essential Oils Growing at Different North African Soils. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2014, 5, 1896–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Radi, M.; Eddardar, Z.; Drioiche, A.; Remok, F.; Hosen, M.E.; Zibouh, K.; Ed-Damsyry, B.; Bouatkiout, A.; Amine, S.; Touijer, H.; et al. Comparative Study of the Chemical Composition, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oils Extracted from Lavandula abrialis and Lavandula stoechas: In Vitro and in Silico Analysis. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1353385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benabdelkader, T.; Zitouni, A.; Guitton, Y.; Jullien, F.; Maitre, D.; Casabianca, H.; Legendre, L.; Kameli, A. Essential Oils fromWild Populations of Algerian Lavandula stoechas L.: Composition, Chemical Variability, and in Vitro Biological Properties. Chem. Biodivers. 2011, 8, 937–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ez Zoubi, Y.E.; Bousta, D.; Lachkar, M.; Farah, A. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Ethanolic Extract of Lavandula stoechas L. From Taounate Region in Morocco. Int. J. Phytopharm. 2014, 5, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Insawang, S.; Pripdeevech, P.; Tanapichatsakul, C.; Khruengsai, S.; Monggoot, S.; Nakham, T.; Artrod, A.; D’Souza, P.E.; Panuwet, P. Essential Oil Compositions and Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Five Lavandula stoechas Cultivars Grown in Thailand. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1900371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitton, Y.; Nicolè, F.; Moja, S.; Benabdelkader, T.; Valot, N.; Legrand, S.; Jullien, F.; Legendre, L. Lavender Inflorescence: A Model to Study Regulation of Terpenes Synthesis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 749–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhaled, A.; Boudjelal, A.; Napoli, E.; Baali, F.; Ruberto, G. Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidant Activity and Wound Healing Properties of Artemisia absinthium Essential Oil. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2020, 10, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhdari, W.; Mounir Bouhenna, M.; Salah Neghmouche, N.; Dehliz, A.; Benyahia, I.; Bendif, H.; Garzoli, S. Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Activity of Artemisia absinthium L. Essential Oil against Adults of Tenebrio molitor L. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2024, 116, 104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchohra, H.A.; Dif, M.M.; Tounsi, M.; Medjaher, H.E.S.; Aissaoui, L. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oil of Aerial Part of Artemisia absinthium L. (Asteraceae) From Algeria. Comptes Rendus L’Acad. Bulg. Des Sci. 2023, 76, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, T.M.; Dias, H.J.; Medeiros, T.C.T.; Grundmann, C.O.; Groppo, M.; Heleno, V.C.G.; Martins, C.H.G.; Cunha, W.R.; Crotti, A.E.M.; Silva, E.O. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil of Artemisia absinthium Asteraceae Leaves. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2017, 20, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, L.; Chograni, H.; Elferchichi, M.; Zaouali, Y.; Zoghlami, N.; Mliki, A. Variations in Tunisian Worm wood Essential Oil Profiles and Phenolic Contents between Leaves and Flowers and Their Effects on Antioxidant Activities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 46, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathlouthi, A.; Belkessam, M.; Sdiri, M.; Diouani, M.F.; Souli, A.; El-Bok, S.; Ben-Attia, M. Chemical Composition and Anti-Leishmania Major Activity of Essential Oils from Artemesia Spp. Grownin Central Tunisia. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houti, H.; Ghanmi, M.; Satrani, B.; ElMansouri, F.; Cacciola, F.; Sadiki, M.; Boukir, A. Moroccan Endemic Artemisia herba-alba Essential Oil: GC-MS Analysis and Antibacterial and Antifungal Investigation. Separations 2023, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens-Molina, J.A.; Vacas, S.; Castell, V.; Németh-Zámboriné, É. Variability of Essential Oil Composition of Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) Affected by Plant Organ. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2017, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, M.S.; Azar, P.A.; Hosain, S.W.; Khalilzadeh, M.A.; Zanousi, M.B.P. Composition of Essential Oil of Artemisia absinthium by Three Different Extraction Methods: Hydrodistillation, Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction & Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction. Asian J. Chem. 2012, 24, 5371–5376. [Google Scholar]

- Baali, F.; Boumerfeg, S.; Napoli, E.; Boudjelal, A.; Righi, N.; Deghima, A.; Baghiani, A.; Ruberto, G. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Essential Oils from Two Wild Algerian Medicinal Plants: Mentha pulegium L. and Lavandula stoechas L. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2019, 22, 821–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassine, E.Z.; Abdelhakim, E.O.L.; Dalila, B.; Moschos, P.; Dimitra, D.; Mohammed, L.; El Abdessalam, K.; Abdellah, F. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of the Essential Oil and Its Fractions of Lavandula stoechas L. from Morocco. Int. J. Curr. Pharm. Rev. Res. 2017, 8, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Et-Touys, A.; Abrini, J.; Talbaoui, A.; Fellah, H.; Bakri, Y.; Dakka, N. Lavandula stoechas Essential Oil from Moroccoas Novel Source of Antileishmanial, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 12, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aati, H.Y.; Perveen, S.; Orfali, R.; Al-Taweel, A.M.; Aati, S.; Wanner, J.; Khan, A.; Mehmood, R. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oils of Artemisia absinthium, Artemisia scoparia, and Artemisia sieberi Grown in Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8209–8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksibi, N.; Saada, M.; Yeddes, W.; Limam, H.; Tammar, S.; Wannes, W.A.; Labidi, N.; Hessini, K.; Dakhlaoui, S.; Frouja, O.; et al. Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Artemisia absinthium L. Collected from Tunisian Regions. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2022, 66, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Effect of Essential Oil son Pathogenic Bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1451–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, J.; Sadani, S.; Ghaemi, E.; Mazaheri Tehrani, M. Investigation of Composition and Antimicrobial Properties of Lavandula stoechas Essential Oil Using Disk Diffusion and Broth Microdilution. Med. Lab. J. 2016, 10, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.J.; Carson, C.F.; Chang, B.J.; Riley, T.V. Role of the MexAB-OprM Efflux Pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Tolerance to TeaTree (Melaleuca alternifolia) Oil and Its Monoterpene Components Terpinen-4-Ol, 1, 8-Cineole, and α-Terpineol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1932–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Omari, N.; Balahbib, A.; Bakrim, S.; Benali, T.; Ullah, R.; Alotaibi, A.; NaceiriElMrabti, H.; Goh, B.H.; Ong, S.K.; Ming, L.C.; et al. Fenchone and Camphor: Main Natural Compounds from Lavandula stoechas L., Expediting Multiple in Vitro Biological Activities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirci, F.; Karaca, N.; Şener, G.; Demirci, B. Synergistic Antibacterial Combination of Lavandula latifolia Medik. Essential Oilwith Camphor. Z. Fur Naturforschung Sect. C-J. Biosci. 2021, 76, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential Oils: Their Antibacterial Properties and Potential Applications in Foods—A Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzarte, M.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Cruz, M.T.; Benzarti, A.; Marongiu, B.; Maxia, A.; Piras, A.; Salgueiro, L. Antifungal and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Lavandula stoechas and Thymus Herba-Barona Essential Oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 44, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahilrajan, S.; Nandakumar, J.; Kailayalingam, R.; Manoharan, N.A.; Sri Vijeindran, S.T. Screening the Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils against Decay Fungi from Palmyrah Leaf Handicrafts. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Z.; Cheng, A.X.; Sun, L.M.; Lou, H.X. Effect of Plagiochin E, an Antifungal Macrocyclic Bis(Bibenzyl), on Cell Wall Chitin Synthesis in Candida Albicans. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008, 29, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Tripathi, A. Effects of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck Epicarp Essential Oil on Growth and Morphogenesis of Aspergillus niger(L.) Van Tieghem. Microbiol. Res. 2008, 163, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Zhiri, A.; Baudoux, D.; Idaomar, M. Antigenotoxic Effects of Three Essential Oils in Diploid Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) after Treatments with UVC Radiation, 8-MOP plus UVA and MMS. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2006, 606, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, E.; Irfan, S.; Kamil, M.; Sheikh, S.; Hasan, A.; Ahmad, A.; Lakshmi, V.; Nazir, A.; Mir, S.S. Terpenoids with Antifungal Activity Trigger Mitochondrial Dysfunctionin Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology 2016, 85, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, A.; Manzoor, N. Reversal of Efflux Mediated Antifungal Resistance Underlies Synergistic Activity of TwoMonoterpenes with Fluconazole. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 48, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, B.; Singh, P.; Kedia, A.; Dubey, N.K. Assessment of Some Essential Oils as Food Preservatives Based on Antifungal, Antiaflatoxin, Antioxidant Activities and in Vivo Efficacy in Food System. Food Res. Int. 2012, 49, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, N.; Woldeamanuel, Y.; Asrat, D.; Debella, A. Effect of Essential Oils on Aspergillus Spore Germination, Growthand Mycotoxin Production: A Potential Source of Botanical Food Preservative. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, S373–S381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abdali, Y.; Agour, A.; Allali, A.; Bourhia, M.; El Moussaoui, A.; Eloutassi, N.; Mohammed Salamatullah, A.; Alzahrani, A.; Ouahmane, L.; Aboul-Soud, M.A.M.; et al. Lavandula dentata L.: Phytochemical Analysis, Antioxidant, Antifungal and Insecticidal Activities of Its Essential Oil. Plants 2022, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, I.; Hamouda, A.B.; Tayeb, W.; Zarrad, K.; Bouslema, T.; Laarif, A. The Tunisian Artemisia Essential Oil for Reducing Contamination of Stored Cereals by Tribolium castaneum. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Jovanović, B.; Jović, J.; Ilić, B.; Miladinović, D.; Matejić, J.; Rajković, J.; Đorđević, L.; Cvetković, V.; Zlatković, B. Antimicrobial, Antioxidative, and Insect Repellent Effects of Artemisia absinthium Essential Oil. Planta Medica 2014, 80, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Baki, A.A.S.; Aboelhadid, S.M.; Al-Quraishy, S.; Hassan, A.O.; Daferera, D.; Sokmen, A.; Kamel, A.A. Cytotoxic, Scolicidal, and Insecticidal Activities of Lavandula stoechas Essential Oil. Separations 2023, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, S.C.; Silies, M.; Martelli, C. Adaptive Temporal Processing of Odor Stimuli. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 383, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedini, S.; Djebbi, T.; Ascrizzi, R.; Farina, P.; Pieracci, Y.; Echeverría, M.C.; Flamini, G.; Trusendi, F.; Ortega, S.; Chiliquinga, A.; et al. Repellence and Attractiveness: The Hormetic Effect of Aromatic Plant Essential Oils on Insect Behavior. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 210, 118122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattayakhom, A.; Wichit, S.; Koomhin, P. The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayllón-Gutiérrez, R.; Díaz-Rubio, L.; Montaño-Soto, M.; Haro-Vázquez, M.d.P.; Córdova-Guerrero, I. Applications of Plant Essential Oils in Pest Control and Their Encapsulation for Controlled Release: A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunse, M.; Daniels, R.; Gründemann, C.; Heilmann, J.; Kammerer, D.R.; Keusgen, M.; Lindequist, U.; Melzig, M.F.; Morlock, G.E.; Schulz, H.; et al. Essential Oils as Multicomponent Mixtures and Their Potential for Human Health and Well-Being. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 956541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouali Lalami, A.; El-Akhal, F.; Maniar, S.; EzZoubi, Y.; Taghzouti, K. Chemical Constituents and Larvicidal Activity of Essential Oil of Lavandula stoechas (Lamiaceae) from Morocco against the Malaria Vector Anopheles labranchiae (Diptera:Culicidae). Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2016, 8, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- El-Akhal, F.; Ramzi, A.; Farah, A.; Ez Zoubi, Y.; Benboubker, M.; Taghzouti, K.; El Ouali Lalami, A. Chemical Composition and Larvicidal Activity of Lavandula angustifolia Subsp. angustifolia and Lavandula dentate Spp. dentate Essential Oils against Culex pipiens Larvae, Vector of West Nile Virus. Psyche J. Entomol. 2021, 2021, 8872139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, P.; Rather, M.A.; Mukhtar, M.; Sherwani, A.; Ganie, S. Fumigant Toxicity of Artemisia absinthium Essential Oil To Common Stored Product Pests. Indian J. Entomol. 2022, 84, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalbane, I.; Alahyane, H.; Aboussaid, H.; Chouikh, N.-e.; Costa, J.; Romane, A.; El Messoussi, S. Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Properties of Moroccan Lavandula dentate and Lavandula stoechas Essential Oils Against Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis capitata. Neotrop. Entomol. 2022, 51, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.D.; Campoy, F.J.; Pascual-Villalobos, M.J.; Muñoz-Delgado, E.; Vidal, C.J. Acetylcholinesterase Activity of Electric EelIs Increased or Decreased by Selected Monoterpenoids and Phenylpropanoids in a Concentration-Dependent Manner. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2015, 229, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evelyn, M.N.; Edgar, P.N.; Soledad, Q.C.; Carlos, C.A.; Alejandro, M.V.; Julio, A.E. Insecticidal, Antifeedant and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity of Sesquiterpenoids Derived from Eudesmane, Their Molecular Docking and QSAR. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 201, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, L.J.N.; Prieto-Rodríguez, J.A.; Patiño-Ladino, O.J. Synergistic Insecticidal Activity of Plant Volatile Compounds: Impact on Neurotransmission and Detoxification Enzymes in Sitophilus zeamais. Insects 2025, 16, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, J.A.; Thangapandian, R.; Vijayaraghavan, C.; Patel, R.R.D.; Kiran, S.R. Insecticidal Potential of Essential Oil and Sesquiterpene Alcohols from Leaves of Clausena indica (Dalz.) Oliver Against Spodoptera litura, Helicoverpa armigera, and Tribolium castaneum Under Laboratory and Field Conditions. Neotrop. Entomol. 2025, 54, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, R.; Adhikari, K.; Mahanta, S.; Khanikor, B. Combinations of Plant Essential Oil Based Terpene Compounds as Larvicidal and Adulticidal Agent against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, P.; Marciniak, P.; Adamski, Z.; Ntalli, N. Controlling Stored Products’ Pests with Plant Secondary Metabolites: A Review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadollahi, A.; Jalali Sendi, J.; Setzer, W.N.; Changbunjong, T. Encapsulation of Eucalyptus largiflorens Essential Oil by Mesoporous Silicates for Effective Control of the Cowpea Weevil, Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Molecules 2022, 27, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Sammour, E.A. Evaluating the Persistence and Insecticidal Effects of Emulsifiable Concentrate Containing Cananga Odorata Essential Oil on Survival and Enzymatic Activity of Spodoptera littoralis. Phytoparasitica 2024, 52, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkouli, R.; Antonopoulou, M.; Asimakis, E.; Spyrou, A.; Kosma, C.; Zotos, A.; Tsiamis, G.; Patakas, A.; Triantafyllidis, V. Mediterranean Plants as Potential Source of Biopesticides:An Overview of Current Research and Future Trends. Metabolites 2023, 13, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Solami, H.M. Larvicidal Activity of Plant Extracts by Inhibition of Detoxification Enzymes in Culex pipiens. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2021, 33, 101371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniewicz, P.; Sytykiewicz, H.; Chrzanowski, G. The Effect of Essential Oils from Asteraceae Plants on Behavior and Selected Physiological Parameters of the Bird Cherry-Oat Aphid. Molecules 2024, 29, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).