Abstract

As global climate change intensifies, research on low-carbon practices has become a critical component of sustainable tourism development. The carbon emission profile of ski tourism differs significantly from other tourism sectors. Ski resorts have a mountainous terrain and typically maintain relatively high levels of vegetation, endowing them with inherent advantages for pioneering low-carbon and sustainable tourism practices. However, the substantial energy demands associated with artificial snowmaking systems and advanced infrastructure pose significant challenges to reducing carbon emissions in ski resort operations. This study gathers first-hand data on sustainable tourism development in the Chongli ski resort—the region that hosted the 2022 Winter Olympics—through field investigations and interviews with key industry stakeholders. It develops a comprehensive framework accounting for carbon emissions in ski resorts by integrating input–output analysis with enterprise-level data, focusing on four core operational sectors: catering, skiing, wholesale and retail, and leasing and business services. Furthermore, this study examines the coupling relationship between carbon emissions and operating revenue. Using correlation and regression analyses, this study identifies the key drivers of carbon emissions across these operational departments within the ski tourism sector. The results indicate that carbon emissions from these four sectors in the Chongli ski resort exhibit periodic fluctuations with an overall upward trend year by year. Nevertheless, progress in low-carbon development is evident, suggesting that the resort is on a trajectory toward achieving peak carbon emissions and eventual carbon neutrality. The inclusion of natural endowments, market-scale effects, festival and special events, and capital investment in ski tourism collectively serve as crucial drivers for low-carbon sustainability in Chongli. Based on these findings, this study proposes targeted recommendations to support low-carbon sustainable development, offering scientific insights for similar Winter Olympics host cities. This study integrates top-down input–output analysis with bottom-up enterprise data, taking Chongli, the host city of the Winter Olympics, as a timely case study. It constructs a four-dimensional low-carbon development model based on the identification of key natural, social, and economic driving factors, and strengthens the reliability of the conclusion by relying on first-hand field research and operator interview data. Our study provides an analysis of methodological innovation, framework integrity, and solid empirical evidence that accounts for micro-scale carbon emissions in ski resorts.

1. Introduction

Global climate change represents a critical challenge to human development, garnering worldwide attention and spurring global initiatives for mitigation [1,2]. The extensive impacts of climate change—including significant economic losses [3], disruptions to employment [4], and public health crises [5]—underscore the urgent need for effective carbon emission reductions methods across all sectors. The tourism industry, while a powerful engine for economic growth and job creation [6,7,8,9], is also a substantial contributor to carbon emissions, posing a threat to ecological systems [10,11,12].

Ski tourism faces a distinct paradox. As a multi-billion-dollar sector hosting between 300 and 350 million annual skiers worldwide [13], it is both vulnerable to and complicit in climate change. Rising temperatures diminish the reliability of natural snow, forcing resorts to increasingly depend on energy-intensive snowmaking [14,15]. This reliance, in turn, exacerbates carbon emissions, creating a feedback loop. Furthermore, development of resorts and their operations, including artificial snowmaking, can negatively impact local biodiversity [13,14]. The role of ski tourism in sustainable development is to account for its energy demands and greenhouse gas emissions [16,17]. Therefore, reducing carbon emissions in ski resorts and exploring green, low-carbon, and circular sustainable development models have become key strategies for the ski tourism industry to address global warming and ecological degradation [18]. Such efforts are also vital for promoting industrial upgrades and structural optimization of ski tourism, thereby advancing the sustainable development of the tourism sector as a whole [19].

Research on low-carbon development in the tourism industry mainly focuses on accounting for carbon emissions [20,21] and pathways for emission reduction [22,23,24]. Since Gossling and Scott first argued that tourism is not a low-carbon industry—particularly due to air travel [25,26,27]—the scope of carbon emissions research has expanded from individual tourism sectors to systematic assessments and, more recently, to integration with other industries. The scale of this research has also broadened from the national [28] and regional levels [29,30] to specific types of tourism areas, such as the ski resorts studied herein. Steiger (2019) highlighted the significant risks climate change poses to ski tourism, including shorter ski seasons and shifts in market competitiveness [13]. Yang (2023) discussed the environmental impacts of ski tourism and emphasized the need to foster low-carbon behaviors among tourists [31]. Sung (2015) quantified carbon sequestered by and emitted from tourism-related activities at the Oak Valley resort, a ski and golf resort located in Korea, in 2006, underscoring the importance of low-carbon sustainability in ski tourism [17]. Other scholars have contributed by identifying specific emission reduction strategies: Rutty (2014) evaluated the efficacy of vehicle monitoring and eco-driver training in reducing CO2 emissions at ski resorts [32]. Unger (2016) analyzed sustainable alpine tourism models that incorporated travel-related emissions [16]. Polderman (2020) developed a Smart Altitude Decision-Making Toolkit aimed at supporting the transition of ski resorts towards a low-carbon economy [33].

Carbon accounting in tourism mainly employs a top-down and bottom-up approach [34]. The top-down method estimates emissions using regional or national economic accounting data [35,36], while the bottom-up approach traces emissions from consumption, covering the full lifecycle of tourism activities [37]. Due to the differing standards and distinct advantages and limitations of each method, researchers are increasingly combining both to develop more robust accounting frameworks [38]. Although input–output analysis—a top-down method—is widely used, its application at the micro-scale (e.g., for individual ski resorts or tourism sectors) remains limited. A notable exception is Sun (2020), who integrated the bottom-up and top-down approaches to measure the carbon footprint of wine tourism [38]. Such integrated approaches represent an emerging trend in accounting for carbon emissions in tourism and offer valuable insights for identifying emission sources and designing mitigation strategies at the micro level. Existing research methods to determine carbon emissions in tourism resorts have largely relied on visitor surveys and energy consumption data [17].

In summary, reducing carbon emissions is essential for achieving sustainable tourism, especially for ski resorts, which face mounting challenges under global climate change. Although interest in the low-carbon and sustainable development of ski resorts is growing, several research gaps remain. Most studies rely heavily on skier surveys, which often fail to capture systemic influences such as emissions from the tourism consumption supply chain. Moreover, research on influencing factors tends to focus narrowly on tourist behavior and travel-related emissions, lacking consideration of both natural and anthropogenic dimensions.

This leaves critical research gaps. First, a comprehensive accounting framework that captures the full scope of emissions, including those embedded in the tourism consumption supply chain, is lacking for ski resorts. Second, analyses of factors influencing emissions have predominantly focused on tourist behavior and transportation, failing to adequately integrate both natural and anthropogenic drivers.

To address these gaps, this study makes a novel contribution by constructing a hybrid carbon emission calculation model that integrates “top-down” input–output analysis with “bottom-up” enterprise-level data. Our method innovatively links operational data from various ski tourism suppliers with the final consumption structure of a regional input–output table. By leveraging the complete consumption coefficient matrix, we can trace and quantify carbon emissions across the entire supply chain. Furthermore, this research incorporates remote sensing and big data from the Internet to holistically analyze the natural and human factors influencing carbon emissions in ski resorts.

This study focuses on the Chongli ski resort—a primary venue for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics—as a compelling case study. Chongli is emblematic of the global ski industry’s dual challenges and ambitions. Its explicit commitment to sustainable development, through both emission reduction and enhanced carbon sequestration, positions it as a frontrunner in the pursuit of low-carbon and potentially carbon-neutral goals for major winter sport destinations. The choice of Chongli is, thus, not only representative but also significant in its practical importance. The findings of this study can provide a scientific reference for other cities hosting the Olympics and regions based on alpine tourism, navigating the path toward low-carbon sustainable development.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

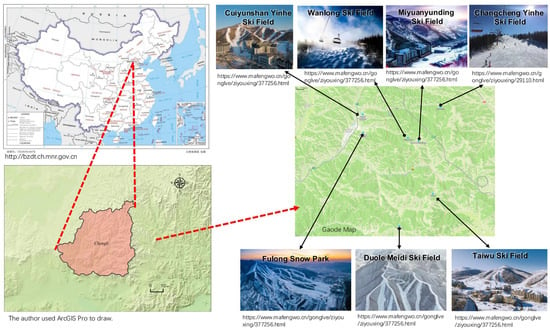

As one of the main competition venues for snow sports at the 2022 Winter Olympics, Chongli, Hebei, actively implemented the concept of green hosting. During the preparation for the Winter Olympics, the concept of green and low-carbon practices was integrated into the entire process of building and developing the Chongli Ski Tourism Resort. The Ski and Tourism Resort in Chongli, Hebei Province, is located in Chongli District, Zhangjiakou City, Hebei Province (Figure 1). It began in 1996 and has undergone 20 years of meticulous cultivation and dedicated development. Currently, it includes 169 ski runs totaling 161.7 km and 68 cable cars and aerial tramways totaling 45.6 km, forming the largest ice and snow tourism cluster in North China. The core area covers an area of 280 km2. The core area includes Wulan Ski Resort, Miyuan Yunding Park, Taowu Ski Resort, Changchengling Ski Resort, Fu Long Ski Resort, Duolameidi, and Cuiyunshan Galaxy Ski Resort. The total ski run area is 470 hectares, with a maximum daily capacity of 56,000 visitors. The vertical drop of the ski runs in the core area is 550 m.

Figure 1.

Study area.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

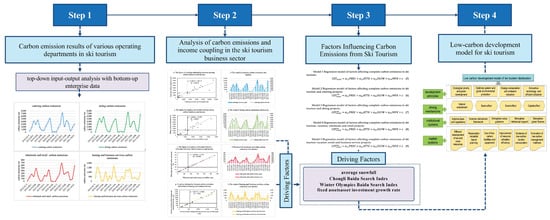

This study focuses on the ski tourism industry within the Chongli ski resort, employing key indicators such as tourist arrivals, tourism revenue, and energy consumption to conduct a computational analysis of operational data across four business sectors: skiing operations, catering services, rental businesses, and retail trade. This study innovatively applies input–output analysis to link micro-enterprises with regional economic structures, establishing a framework with which to measure carbon emissions for ski tourism. By conducting correlation analysis and single-indicator regression analysis, this study identifies potential influencing factors affecting overall ski tourism and its various operating departments, and also develops an econometric regression model. The ordinary least squares (OLS) method was used to estimate the direction and magnitude of the impacts of these factors on total carbon emissions in ski tourism and its subsectors. Based on these findings, this study examines the driving mechanisms underlying reductions in carbon emissions in the development of ski tourism resorts, while exploring foundational principles and concrete measures for advancing low-carbon development in the industry (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research framework.

2.3. Carbon Accounting Methodology

Currently, methods for calculating carbon emissions in tourism are primarily categorized into top-down and bottom-up approaches. The bottom-up approach focuses on investigating and analyzing both demand-side tourists and supply-side tourism enterprises, employing techniques such as lifecycle assessments to estimate carbon emissions (or carbon footprint). This method yields relatively accurate data; however, due to its reliance on field surveys for data collection, it is predominantly applied at the micro-scale—such as individual scenic spots, resorts, or restaurants—to account for carbon generated from tourism. In contrast, the top-down approach estimates carbon emissions at the industry or regional levels using macro-level statistical data. Typically, the carbon emissions of the tourism sector are derived through coefficient disaggregation by mapping tourism-related activities to corresponding sectors in national or regional input–output accounts. This method provides long-term time series data and is commonly used for the meso- and macro-scale spatial analyses of tourism emissions.

The ski resort in Chongli—the host city of the 2022 Winter Olympics—is a key component of regional economic development with strong links to agriculture, industry, and other service sectors, making it particularly suitable for carbon emission analysis using input–output methods. At the same time, compared to broader provincial or national scales, the city level offers greater feasibility for collecting detailed tourism consumption data through surveys. Therefore, a bottom-up survey approach can be employed to obtain precise operational data from ski resorts. By integrating this with a top-down input–output framework, carbon emission flows across interconnected industrial sectors can be systematically analyzed, enabling a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of emissions in the Olympic host region and providing robust scientific support for developing low-carbon tourism models.

Given that the highest spatial resolution of China’s official input–output data is currently limited to the provincial level, applying this analysis to the micro-scale remains challenging. Chongli is located in Hebei Province. According to the collective principles of the input–output data, sectors within the same classification share similar input–output structures, and micro-enterprises within these sectors generally conform to the broader industrial patterns of the region. Therefore, this study adopts the input–output structure of Hebei Province, integrates it with operational data from key sectors, and uses it to estimate carbon emissions from ski tourism in Chongli. Primary data for this research were collected from major ski resorts in Chongli, covering four core operating departments: catering, skiing, wholesale and retail, and leasing and business services—excluding accommodation and transportation. Thus, the scope of measuring carbon emissions in this study is defined by these four departments.

Based on the 2017 Hebei Provincial input–output table, the structure of carbon emissions is presented in Table 1, where the second quadrant represents intermediate inputs and outputs, the first quadrant corresponds to final use, and the third quadrant reflects the value-added component.

Table 1.

Input–output table.

Specifically, in this study, the input–output table includes n production departments; representing the final use of department I; representing the total output of department I; representing the added value of department j; and representing the total input of department j.

According to the theory and research ideas of tourism satellite accounts during the research period, ski tourism catering, skiing, wholesale and retail, and leasing and business services represented different industries in the input–output table. The operating income of the four core operating departments was used to determine the proportion of their respective parts. Using the 2017 input–output table of Hebei Province (Although preparation for the Winter Olympics promoted infrastructure investment and tourism development in some local areas, such as Zhangjiakou, this impact had significant sectoral limitations and did not significantly in-fluence the macroeconomic structure of Hebei Province and the traditional industries at the local city and county levels, which form the core of the province’s economy. The connections of internal technology production between these leading industries, that is, the input–output structure, remained relatively stable in the medium term. Furthermore, the input–output table of the regional economy mainly reflects the deep-seated production of technology determined by medium- and long-term supply-side demands. During the relatively short period from 2017 to 2021, despite fluctuations in demand-side and large-scale projects driven by policies, the vast industrial system of Hebei Province and its supporting supply chain technology coefficients did not undergo systematic and fundamental re-structuring. The economic fundamentals of the province maintained a strong continuity.), the complete energy consumption coefficient matrix was calculated based on the final use of each ski resort project. Column data were established for the final use, and then the indirect investment levels were calculated for the final use of each of the four operating departments.

Because the input–output table data is only developed every five years to obtain continuous data, the input–output structure assumption for 2018–2021 is consistent with that of 2017. Based on the input–output table, the relationship between the total economic output and the final usage can be obtained:

In Formula (1), X represents the total output matrix of all industries; Y represents the final use matrix of all industries; and A represents the direct consumption coefficient matrix, Leontief inverse matrix, and complete energy consumption coefficient matrix of all industries.

To represent the final consumption matrix of the four operating departments of ski tourism, Y, can be replaced with L, the Leontief inverse matrix can be transposed, and the matrix on the right side of the equation represents the total investment matrix for producing a certain product.

In Formula (2), is a matrix of 1 × m, where m represents m departments in the input–output table. In this study, the input–output table of Hebei Province in 2017 consisted of 42 departments, with t representing a specific time point.

The accuracy of this study is based on months. Referring to the IPCC standard, the energy emission coefficient corresponding to the industry based on the income of each project is calculated, followed by the carbon emission coefficient .

The specific calculation steps are as follows:

In Formula (3), represent the energy consumption coefficients of catering, skiing, wholesale and retail, and leasing and business activities projects, respectively. is the conversion coefficient of standard coal for k (k = 1,2, …r) types of energy. The sectors in ski resorts did not have data in the energy balance sheet and value-added statistics. Therefore, we calculated the energy coefficients based on the corresponding departments for each sector. represents the consumption of k types of energy in other departments; represents the wholesale and retail, accommodation, and catering industries in Hebei Province (The consumption data is sourced from the 2018 Regional Energy Balance Table in Hebei Province). ; represents the added value of other departments; and represents wholesale and retail and accommodation and catering industries in Hebei Province.

The methodology used in this study to account for carbon emissions aligns with the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories and its 2019 Refinement. Specifically, the emission factors for energy consumption (e.g., electricity, coal, and natural gas) are derived from the default values provided in IPCC Volume 2 (Energy), and the standard coal conversion coefficients are consistent with those recommended in the China Energy Statistical Yearbook, which itself is compiled in accordance with international energy accounting standards. This ensured that our carbon emission estimates were comparable and verifiable against internationally accepted protocols. Furthermore, the system boundary for carbon emissions from ski tourism—covering direct emissions from energy use and indirect emissions from the supply chain—is defined in line with scopes 1 and 2 of the IPCC’s emission categories, thereby enhancing the transparency and credibility of our accounting framework.

The sum of all input column vectors from different operating departments in ski tourism is the total output of different operating departments of ski tourism, represented by . Carbon emissions from ski tourism catering, skiing, wholesale and retail, and leasing and business service projects are represented by as follows:

Coupling analysis of carbon emissions and operating income: The operating income of the four core operating departments of ski tourism was investigated against total carbon emissions, using different relative efficiency thresholds as classification criteria. Based on this, the development process of these departments from 2018 to 2021 was categorized into four distinct carbon emission–income types: Type I (high carbon and high income), Type II (high carbon and low income), Type III (low carbon and low income), and Type IV (low carbon and high income). This typology enables a systematic discussion of the coupling relationship and decoupling mechanisms between income and carbon emissions across the four core departments during different periods.

Analysis of influencing factors: This study examines the factors driving carbon emissions in ski tourism from three analytical dimensions: natural conditions, social environment, and economic environment.

Natural conditions are represented by monthly climatic indicators, including the average daily maximum temperature (°C), average daily minimum temperature (°C), total monthly snowfall (mm), number of snowy days per month, average monthly sunshine duration (h), average wind speed (m/s), relative humidity (%), and average air quality index (AQI).

The social environment comprises two components: the public attention level and policy support intensity. Public attention is measured by the Baidu Search Index for four key terms—Chongli, Winter Olympics, ice and snow, and low-carbon levels—reflecting trends in public interest. Policy support intensity is assessed based on the frequency of relevant keywords—ice and snow, Winter Olympics, and low-carbon levels—appearing on the official websites of Zhangjiakou City and Chongli District government.

The economic environment includes four macroeconomic indicators representing the inflation level (Consumer Price Index), investment level (growth rate of fixed asset investment), production level (Producer Price Index), and consumption capacity (retail sales of consumer goods for enterprises above the designated size at the provincial level). These variables collectively capture the broader economic context influencing ski tourism emissions.

2.4. Statistical Analysis Approach

A time series regression model was designed for influencing factors of carbon emissions in Chongli ski tourism: The maximum and minimum values of the aforementioned indicators were normalized using STATA 14 software. Correlation analysis was then conducted between these indicators and the dependent variable, followed by individual regression analyses. Based on statistical significance and the strength of regression coupling, four key variables were selected (the process of which is detailed in Supplementary Materials File S1): average snowfall (PREC) from natural conditions; the Chongli Baidu Search Index (ATTE), the Winter Olympics Baidu Search Index (ICES), and the fixed asset investment growth rate (INVE) from the economic environment. The characteristics of these variables’ statistics can be found in Table 2. A time series regression model was constructed to analyze the factors affecting carbon emissions in Chongli ski tourism, as follows. Model 1: Regression model of factors affecting complete carbon emissions in ski tourism:

Table 2.

Description of factors influencing carbon emissions from ski tourism.

Model 2: Regression model of factors affecting complete carbon emissions in ski tourism’s catering projects ():

Model 3: Regression model of factors affecting complete carbon emissions in ski tourism’s skiing projects ():

Model 4: Regression model of factors affecting complete carbon emissions in ski tourism’s wholesale and retail projects ():

Model 5: Regression model of factors affecting complete carbon emissions of ski tourism’s rental and business service projects ():

A description of each influencing factor is shown in the table below.

2.5. Data Collection Methods

The basic dataset comes from first-hand data acquired through field investigations and telephone interviews with major ski resorts in Chongli. A detailed questionnaire can be found in Supplementary Materials File S2. The input–output data are sourced from the Hebei Statistical Yearbook for sectors including wholesale, retail, accommodation, catering, and other relevant service industries. Standard coal conversion coefficients were obtained from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook to convert energy consumption data from these sectors into unified units. Natural condition variables were derived from meteorological records provided by the China Meteorological Administration. Public attention data in the social environment were collected from the Baidu Index, while the intensity of policy support was obtained from official government websites at the local and municipal levels. Economic environment indicators were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics’ official data platform.

3. Results

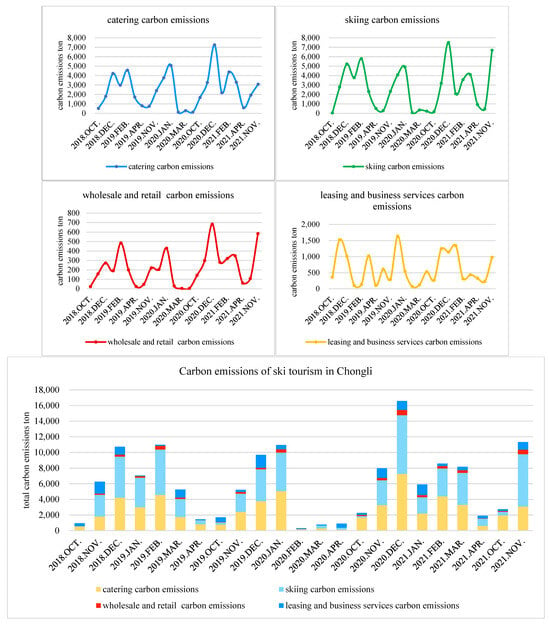

3.1. Carbon Emission Results of Various Operating Departments in Ski Tourism

From the perspective of the catering department, the mid-snow season is often a period of high carbon emissions (for example, direct carbon emissions reached 1742.58 tons in December 2018, and indirect carbon emissions reached 2485.12 tons) (Figure 3). However, at the beginning of the season (such as April 2019), direct carbon emissions were 329.69 tons and indirect carbon emissions were 470.18 tons, and at the end of the season (such as February 2020), direct carbon emissions were 53.92 tons and indirect carbon emissions were 76.90 tons. Emissions during the snow season were at their lowest level. The mid-snow season often involves holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s Day, and Spring Festival. The increase in food and beverage consumption during these holidays is the main factor promoting the increase in carbon emissions from ski tourism. From the perspective of the skiing department, the mid-snow season is mostly a high-value period for carbon emissions (for example, direct carbon emissions were 2210.78 tons in December 2018, and indirect carbon emissions were 3016.67 tons). However, these emissions significantly decreased at the beginning (such as 220.36 tons of direct carbon emissions and 300.69 tons of indirect carbon emissions in April 2019) and the end (such as 32.38 tons of direct carbon emissions and 44.19 tons of indirect carbon emissions in February 2020) of the ski season. Similarly, the increase in holiday tourism activities in the mid-snow season promotes an increase in carbon emissions due to skiing operations. Conversely, the economic demands of the holiday have a relatively weak impact on the carbon emissions of the wholesale and retail sector, which mainly focuses on personal skiing equipment such as ski equipment and snow suits. The high-value period of carbon emissions tends to shift slightly backward (for example, direct carbon emissions were 387.02 tons and indirect carbon emissions were 295.97 tons in December 2020). However, at the beginning and end of the snow season (for instance, direct carbon emissions were 13.78 tons and indirect carbon emissions were 10.54 tons in April 2019; direct carbon emissions were 16.98 tons and indirect carbon emissions were 12.99 tons in February 2020), carbon emissions were at a low level. In the early stages of the snow season, there is a higher number of professional skiers; this group of people has a lower demand for personal equipment. However, the transition from professional skiers to skiing enthusiasts in the middle and later stages of the snow season leads to an increase in the demand for personal equipment and other items for skiing, thus promoting a backward trend in the high carbon emissions of ski tourism’s wholesale and retail departments. From the perspective of the leasing and business service departments, the high-value period mostly occurs in the early and mid-snow seasons (for example, in November 2018, direct carbon emissions were 551.67 tons and the indirect carbon emissions were 976.58 tons; in December 2020, the direct carbon emissions were 412.83 tons and indirect carbon emissions were 730.79 tons), while they significantly decreased in the late snow season (for example, in February 2020, direct carbon emissions were 26.12 tons and indirect carbon emissions were 46.25 tons). Considering the higher number of professional skiers in the early and mid-snow season, there is a higher demand for training services and personal equipment leasing, which leads to an increase in the scale of business and carbon emissions. During the holiday economy period in the mid-snow season, due to the increase in tourist numbers, the expansion of the business scale promotes an increase in carbon emissions.

Figure 3.

Carbon emissions from different tourism sectors of ski resorts.

The overall carbon emissions from ski tourism in Chongli have been increasing year by year. Carbon emissions are relatively low during the early and late stages of the snow season but peak during the middle months. The emission pattern indicates that carbon emissions are relatively small in October—the start of the skiing season—and April of the following year—the end of the season. Among all sectors, catering and skiing activities contribute the most to emissions, followed by leasing and business services, while wholesale and retail generate the smallest proportion. This trend suggests that winter vacation periods, including the Spring Festival and other holidays, significantly drive carbon emissions from ski tourism, particularly in the catering and skiing sectors. Therefore, future planning and development of ski tourism should prioritize carbon reduction measures in these two areas.

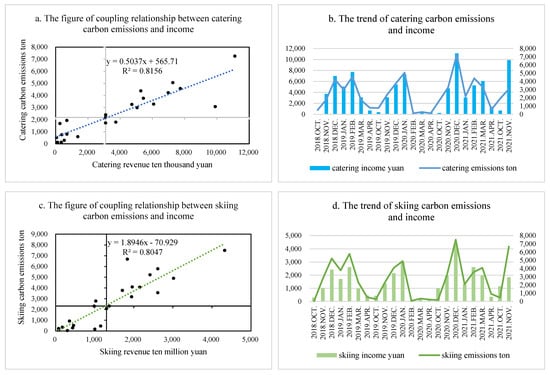

3.2. Analysis of Carbon Emissions and Income Coupling in the Ski Tourism Business Sector

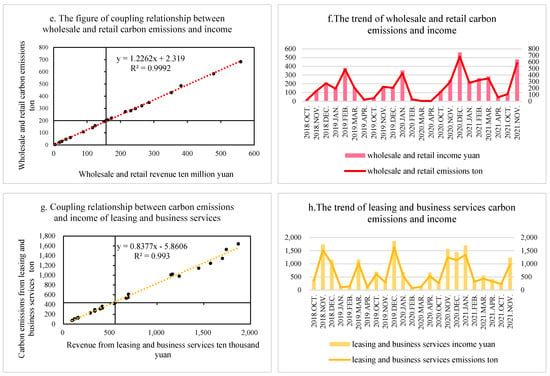

Coupling analysis of carbon emissions and revenue from catering: As shown in the figure below, the coupling curve between catering revenue and carbon emissions has an R2 value of 0.8156, with the majority of data points closely clustered around the fitted line, indicating a strong degree of coupling. Catering revenue explains 81.56% of the variation in carbon emissions from this sector, reflecting a significant positive correlation between revenue and emissions (Figure 4). It is expected that carbon emissions will continue to grow in tandem with increasing revenue in the foreseeable future. In general, during the months at the beginning and end of the snow season, carbon emissions are substantially higher compared to operating income, indicating elevated carbon emission intensity and reduced energy utilization efficiency during these periods. This pattern is closely related to the local climate characteristics of Chongli. Due to its high altitude and low temperatures, many catering enterprises resort to auxiliary heating methods outside the formal heating season to meet tourist demand, which disrupts the scale efficiency of energy supply and increases per-unit energy consumption.

Figure 4.

The coupling relationship between carbon emissions and income in the ski tourism business sector.

Coupling analysis of carbon emissions and revenue from skiing: As shown in Figure 4, the coupling curve between skiing revenue and carbon emissions has an R2 value of 0.8047, with the majority of data points closely clustered around the fitted line, indicating a strong degree of coupling. Skiing revenue explains 80.47% of the variation in carbon emissions from the skiing sector. Overall, there is a significant positive correlation between skiing revenue and carbon emissions. It is expected that carbon emissions will continue to grow in tandem with increasing revenue in the foreseeable future, maintaining a persistent coupling relationship. Unlike catering projects, skiing operations exhibited carbon emissions that were substantially higher than operating income during the mid-2018 snow season, reflecting a high carbon emission intensity and low energy utilization efficiency at this time. However, this situation gradually improved over the following two years. This improvement can be attributed to the green Winter Olympics policy, which drove continuous increases in the supply of low-carbon skiing products in Chongli and ongoing refinement of the low-carbon development model—positioning this sector as a potential leader in achieving carbon peak and carbon neutrality goals.

Coupling analysis of carbon emissions and revenue from wholesale and retail: As shown in Figure 4, the coupling curve between wholesale and retail revenue and corresponding carbon emissions has an R2 value of 0.9992, indicating a high degree of coupling. Most data points are closely clustered around the fitted line, demonstrating that this revenue accounts for 99.92% of the variation in carbon emissions from the wholesale and retail sector. This indicates a strong positive correlation between revenue and carbon emissions in this sector. It is expected that carbon emissions will continue to grow in tandem with increasing revenue in the foreseeable future, maintaining a persistent coupling relationship. Given its low carbon emission intensity and high energy utilization efficiency, this sector is suitable for moderate development to help optimize the overall carbon emission structure of ski tourism.

Coupling analysis of carbon emissions and revenue for leasing and business services: As shown in Figure 4, the coupling curve has an R2 value of 0.993 between revenue and carbon emissions in the leasing and commercial services sector, indicating a high degree of coupling. Most data points are closely clustered around the fitted line, demonstrating that revenue explains 99.30% of the variation in carbon emissions. This reveals a strong positive correlation between leasing and commercial service revenue and associated carbon emissions. It is expected that carbon emissions from this sector will continue to grow in tandem with increasing revenue in the foreseeable future, maintaining a persistent coupling relationship. Given its low carbon emission intensity and high energy utilization efficiency, this sector is suitable for moderate expansion in the future to help optimize the overall carbon emissions structure of ski tourism.

3.3. Analysis of Driving Factors for Carbon Emissions in Ski Tourism

According to the coupling analysis between carbon emissions from various operating departments of ski tourism and ski tourism revenue, a significant positive relationship was found between revenue and carbon emissions, both overall and across individual operating departments. Furthermore, considering the impact of major events such as the Winter Olympics on ski tourism in Chongli during the study period (October 2018 to November 2021), this study focuses on identifying the factors influencing carbon emissions from the perspectives of natural conditions, social environment, and economic environment. All indicators for these influencing factors passed the unit root test and were analyzed using time series regression with the ordinary least squares (OLS) method. Based on the results of the Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test, it is highly likely that there is no heteroscedasticity problem in the model, and no additional heteroscedasticity correction is necessary (Table 3). The regression results are shown in the table below.

Table 3.

Regression results of factors affecting carbon emissions from ski tourism.

The regression results in the table above are discussed below.

A significant overall negative correlation was observed between average snowfall and carbon emissions in ski tourism, as well as in the three operational sectors—catering, skiing, and wholesale and retail. The influence coefficients were −0.563 for total ski tourism emissions, −0.473 for catering, −0.602 for skiing, and −0.453 for wholesale and retail. Increased natural snowfall enhances snow depth and retention at ski resorts, thereby reducing the need for artificial snowmaking, which is a major source of carbon emissions. These results indicate that snowfall exerts the strongest influence on emissions from skiing activities.

In terms of public attention, the Baidu search volume for Chongli shows a significant positive correlation with carbon emissions from ski tourism and its related sectors. The influence coefficients are 0.440 for total emissions, 0.506 for catering, 0.358 for skiing, and 0.464 for wholesale and retail. As search volume reflects both the current and potential tourist market size, it is evident that growth in tourist numbers and consumption has a stronger multiplier effect on carbon emissions in catering compared to other sectors.

Similarly, Baidu search volume for the Winter Olympics positively correlated with carbon emissions from ski tourism and the same three operational sectors. The coefficients were 0.235 for total emissions, 0.113 for catering, 0.310 for skiing, and 0.384 for wholesale and retail. Search behaviors related to the Winter Olympics mirror consumer interest in the event and its host location, illustrating how major events drive ski tourism activity. Thus, the Winter Olympics contributed to increased carbon emissions in Chongli’s ski tourism sector.

In the economic dimension, the growth rate of fixed asset investment exhibits a significant positive correlation with total ski tourism carbon emissions, as well as emissions from catering and wholesale and retail. The influence coefficients are 0.217 for total emissions and 0.251 for catering, while the effect on skiing projects is not significant. Tourism service facilities generally have shorter investment and construction cycles compared to skiing infrastructure. Investments in reception services can more quickly stimulate catering operations and consumption, whereas skiing facilities require longer cycles and have a limited short-term operational impact. Given the significant relationship between operating income and emissions in catering and wholesale/retail, growth in fixed asset investment consequently leads to higher carbon emissions in these sectors and in local ski tourism overall.

4. Discussion

According to the theory of carbon emissions decoupling and the environmental Kuznets curve, as the economy grows, carbon emissions exhibit an inverted U-shaped curve that first increases and then decreases. Carbon decoupling is achieved at the turning point. This theory has received widespread empirical support in the field of ski tourism: Sung et al. (2015) conducted a study on the Oak Valley ski resort in South Korea and found that since 2010, this resort has entered a “weak decoupling stage” of “economic growth–slowdown in carbon emissions growth”, with the carbon emission intensity per unit of revenue increasing by CNY 1.2 per ton of CO2 [17]. Steiger et al. (2019) conducted a follow-up study on ski resorts in the European Alps and discovered that by relying on the substitution of renewable energy and energy-saving renovations of ski facilities, some more established resorts have achieved strong decoupling, with the economic output per unit of carbon emissions reaching CNY 38,000 per ton of CO2 [13]. Some more established ski destinations in the Alps (such as St. Moritz in Switzerland and Kitzbühel in Austria) have achieved “weak decoupling” by promoting electric shuttles, a 100% renewable energy supply, and a visitor carbon compensation mechanism. Some areas even approach “strong decoupling” [39]. However, ski areas in the North American Rockies, due to their reliance on long-distance self-driving tourists, are still in the “expansionary coupling” stage [40]. The findings of this study indicate a strong coupling relationship between ski tourism and operating income in Chongli, suggesting that this sector remains at a relatively low level of carbon emission efficiency—specifically, the economic output per unit of carbon emissions is still limited. This underscores the fact that carbon emissions from ski tourism have not yet decoupled from economic development, reflecting a low level of ecological and economic efficiency.

The main reasons why Chongli has not achieved decoupling can be summarized into three points: Firstly, there is a difference in development stages. As a latecomer ski destination, the infrastructure construction and expansion of ski facilities still rely on high-energy-consuming investment. Secondly, the energy structure is rigid. Artificial snowmaking accounts for more than half of the carbon emissions of the skiing sector, while the proportion of renewable energy supply is lower than 50% of similar European resorts. Thirdly, the dual-sided low-carbon transformation of supply and demand is behind current standards. The supply of low-carbon skiing products is relatively low, and the participation rate of tourists in low-carbon consumption (such as renting environmental protection equipment, using public transportation) is also low. Achieving carbon peak and carbon neutrality targets presents significant challenges for ski tourism in Chongli. It is imperative to accurately identify carbon emission sources, explore effective emission reduction pathways, and enhance the provision of low-carbon products and services through the formulation and implementation of targeted low-carbon management strategies. Improving carbon emission efficiency, guiding tourists toward low-carbon consumption behaviors, and promoting the decoupling of carbon emissions from tourism revenue are critical steps. Ultimately, the goal is to achieve high carbon efficiency in ski tourism development—sustaining robust economic output while minimizing carbon emissions.

To assess the robustness of our carbon emission estimates, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by varying key parameters in the calculation model. Specifically, we adjusted the standard coal conversion coefficients () and the energy consumption coefficients () by ±10%, reflecting potential uncertainties in energy data and emission factors. The results indicate that a 10% increase in values leads to an average increase of 8.7% in total carbon emissions, with the skiing and catering sectors being the most sensitive (9.2% and 9.0%, respectively). Conversely, a 10% decrease in values results in a 7.3% reduction in total emissions. These findings underscore the importance of accurate energy data and the need for localized emission factors in micro-scale carbon accounting. They also highlight how policies targeting energy efficiency in skiing and catering operations would have the most pronounced impact on emission reductions.

Ski resources are among the tourism assets most vulnerable to global climate change. During the 2022–2023 snow season, the snow line in the Alps shifted significantly downward, leading to the closure of nearly half of the ski resorts in Austria, France, and other regions. This highlights the profound impact of climate change on ski tourism. In contrast, leveraging the momentum of the Winter Olympics, skiing has emerged as a new source of growth in China’s tourism industry, with rapidly expanding consumer demand. Given these dynamics, ski tourism must proactively respond to climate challenges by exploring viable low-carbon development pathways. The carbon emission profile of ski tourism differs markedly from that of other tourism sectors. While ski areas typically occupy mountainous terrain with high vegetation coverage—offering inherent advantages for carbon sequestration and early progress toward low-carbon development—the operation and maintenance of ski facilities entail substantial energy consumption. Therefore, more precise identification and optimization of carbon emission pathways are essential to reduce the overall carbon footprint. Consequently, the low-carbon transition of ski tourism warrants greater scholarly attention and requires coordinated efforts among industry regulators, local governments, market operators, and tourists to co-develop a sustainable, low-carbon development model.

This study encountered the following limitations during the process of data acquisition and analysis: Firstly, the sample size is insufficient. The current survey covers only 10 core ski resort areas around Chongli, meaning that the sample size is limited. However, due to its status as an Olympic venue, the ski resort is highly representative, and the generalizability of the research conclusions is good. Secondly, there may be potential biases in the telephone interview data. The interviewees were mostly resort managers, who may have underestimated the carbon emission data due to subjective cognition or considerations of corporate image, affecting the objectivity of the results. Thirdly, the micro-applicability of the provincial input–output table is insufficient. The current measure of indirect carbon emissions relies on provincial industry input–output tables, which have a relatively macro-classification (such as “catering industry”, which is combined for statistics), and cannot precisely match the intermediate input structure of ski tourism subsectors (such as ski equipment rental, artificial snowmaking services). This results in limited accuracy of indirect carbon emission measures for micro-departments. Fourth, monthly aggregation masks frequent seasonal fluctuations. Carbon emission data are aggregated on a monthly basis, failing to capture more granular changes within the ski season (such as peak tourist numbers on weekends and short-term surges during holidays), and missing seasonal driving factors at the daily or weekly level. This affects the in-depth analysis of the seasonal mechanism of carbon emissions. In response to these limitations, in the future, this research will be further integrated with enterprise measures and macro-level surveys, incorporating more comprehensive and detailed data on the full lifecycle of tourist consumption. This integration will facilitate the development of ski tourism input–output tables and environmental input–output tables, thereby refining the carbon emission accounting process and enabling more precise measurement of emissions across different consumption stages and products. Currently, carbon emissions data for ski tourism are available on a monthly basis; however, obtaining corresponding monthly socioeconomic data remains challenging. As a result, for the analysis of influencing factors, the social environment is proxied by public attention to Chongli and the Winter Olympics, while the economic environment is represented by the growth rate of fixed capital investment. Future research will explore alternative methods—such as field investigations, site visits, and big data mining—to obtain more comprehensive and high-resolution indicators of influencing factors, aiming to provide a more complete explanation of ski tourism’s carbon emissions and those of its various operational sectors.

5. Policy Recommendations

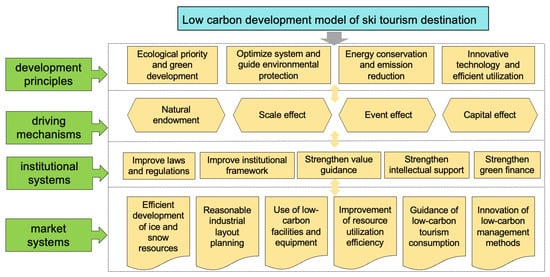

Based on the calculation and analysis of carbon emissions from ski tourism and various operating departments, it is clear that the overall carbon emissions from ski tourism in Chongli show cyclical fluctuations and are influenced by comprehensive factors such as natural conditions, the social environment, and the economic environment. Therefore, it is necessary to consider multiple aspects comprehensively to explore the construction of a low-carbon development model for ski tourism. The development of such a model in this study (Figure 5) includes four dimensions: development principles, driving mechanisms, institutional systems, and market systems.

Figure 5.

Low-carbon development model for ski tourism.

Development principles serve as the foundation of the model, driving mechanisms related to its intrinsic dynamics, while institutional and market systems represent specific implementation measures. The guiding principles include ecological priority, green development, system optimization, guidance on environmental protection, energy conservation and emissions reduction, low levels of carbon consumption, technological innovation, and efficient resource utilization. From the perspective of natural resources, the driving mechanism behind their use should be to ensure favorable natural conditions, promote support from government leadership, rational spatial planning of ski resorts, reduce duration and coverage of artificial snowmaking, and improve efficiency of resource utilization to promote carbon emissions reduction. From the perspective of market-scale effects, attention should focus on how consumption habits and behaviors influence low-carbon ski tourism—by optimizing the design and delivery of low-carbon ski tourism products and enhancing carbon efficiency, defined as economic output per unit of carbon emissions. From the perspective of festivals and special events, the promotion of low-carbon technologies in tourism-related events and activities should be strengthened, leveraging their use in demonstration and guidance. From the perspective of capital influence, a green financial service system should be established to channel investment toward low-carbon infrastructure, equipment, and facilities in ski tourism. Strengthening the low-carbon ski tourism system requires improvements in laws and regulations, institutional mechanisms, value orientation, intellectual support, and green financial services. The market system can be further optimized through intense and efficient use of ice and snow resources, rational industrial layout planning, low-carbon construction and operation of facilities, enhanced resource efficiency, promotion of low-carbon tourist behavior, and innovation in low-carbon management practices.

For ski resort operators, the following policy practices should be prioritized: First, low-carbon facilities and the application of technological innovations should be strengthened, focusing on the use of energy-saving snowmaking equipment and low-energy cableways, and reducing the time and coverage area for artificial snowmaking. Second, the supply of low-carbon tourism products and consumption guidance should be optimized, designing low-carbon-themed skiing routes and promoting low-carbon equipment rental services to drive carbon reduction by upgrading the consumption end. Third, innovative low-carbon management models should be established to improve resource utilization efficiency through intelligent energy monitoring systems, and a “tourism–ecology” collaborative management mechanism should be explored.

For local governments, a systematic policy support framework should be constructed with the following aims: Firstly, improve the regulatory and planning system, formulate local regulations for low-carbon development of ski resorts, and scientifically coordinate the development of ice and snow resources and the spatial layout of the industry within the region. Secondly, strengthen event demonstrations and green financial empowerment, promote the application of low-carbon technologies through public activities such as skiing events, and establish a green finance special fund to guide social capital to invest in low-carbon facilities. Thirdly, enhance technology and value guidance, establish a low-carbon technology training platform for the ski industry, and incorporate the concept of ecological priority into local tourism and cultural education systems.

6. Conclusions

Ski tourism represents a coupled ecological and economic system, within which carbon emissions and recycling processes have an impact on ecosystems, while emission patterns manifest the external impacts inherent to this integrated system. By enhancing carbon sequestration, advancing energy-efficient and low-carbon technologies, and promoting the adoption of renewable energy in ski destinations, critical pathways can be determined to achieve low-carbon development in this sector.

The expansion of ski tourism affects local vegetation and biodiversity, and its operations generate carbon emissions from tourist activities such as dining, accommodation, transportation, sightseeing, shopping, and entertainment. This study uses data on skier visits, tourism revenue, and energy consumption in Chongli—a host city of the Winter Olympics—to quantify carbon emissions from ski tourism and analyze their influencing factors.

An analysis of the evolving carbon emission patterns in Chongli’s ski tourism reveals cyclical fluctuations across four operational sectors: catering, skiing, wholesale and retail, and leasing and business services. Each sector exhibits distinct emission trajectories. For instance, lower temperatures may increase emissions in the catering sector due to higher heating demand, whereas skiing-related emissions may decline as natural snowfall reduces the need for artificial snowmaking. Specifically, elevated emissions in the catering sector during the early snow season reflect increased heating consumption, while reduced emissions in the skiing sector later in the season correlate with decreased reliance on snowmaking equipment.

Beyond climate factors, market dynamics also significantly influence emissions. During peak periods such as the Spring Festival, an increase in tourist numbers leads to a notable rise in overall carbon emissions. Meanwhile, natural snowfall is identified as a key driver of reducing emissions in ski operations.

The study also found that growth in tourist numbers and consumption levels significantly drove emissions, particularly in the catering sector. Fixed capital investment further contributes to emissions, mainly in the catering and wholesale/retail sectors. Based on these findings, this article proposes the rational use of ecological and tourism resources, scientific planning of supporting infrastructure, and innovation in low-carbon transformation mechanisms. It also recommends establishing an integrated interactive framework to promote low-carbon development across related industries, ultimately fostering a mutually beneficial regional development model.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411379/s1, File S1: Variable selection process, File S2: Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.X., Y.L.; software, B.X.; data curation, J.L. and Y.L.; writing—original draft, J.L.; writing—review & editing, J.L., B.X. and C.L.; funding acquisition, B.X. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is founded by Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program (2025FY102000), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42201321).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to it does not involve human subjects in a medical, psychological, or sensitive social context.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| EC | energy consumption |

| CET | carbon emissions of ski tourism |

| PREC | average snowfall |

| ATTE | Chongli Baidu Search Index |

| ICES | Winter Olympics Baidu Search Index |

| INVE | fixed asset investment growth rate |

References

- Kythreotis, A.P. Progress in global climate change politics? Reasserting national state territoriality in a ‘post-political’ world. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, D. Climate change: Embed the social sciences in climate policy. Nature 2015, 520, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenton, T.M.; Xu, C.; Abrams, J.F.; Ghadiali, A.; Loriani, S.; Sakschewski, B.; Zimm, C.; Ebi, K.L.; Dunn, R.R.; Svenning, J.-C.; et al. Quantifying the human cost of global warming. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, D.; Duan, J.; Lu, H.; Yin, H.; Tan, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, M.; Cai, W.; et al. Global supply chains amplify economic costs of future extreme heat risk. Nature 2024, 627, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.J.; Albery, G.F.; Merow, C.; Trisos, C.H.; Zipfel, C.M.; Eskew, E.A.; Olival, K.J.; Ross, N.; Bansal, S. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature 2022, 607, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Wu, D.C. Tourism productivity and economic growth. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, C.; Dogru, T.; Turk, E.S. A nexus of linear and non-linear relationships between tourism demand, renewable energy consumption, and economic growth: Theory and evidence. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudi, S.; Arasli, H.; Akadiri, S.S. New insights into an old issue—Examining the influence of tourism on economic growth: Evidence from selected small island developing states. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Qu, H.; Ma, E. Modelling tourism employment in China. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Tan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, J. Research hotspots, future trends and influencing factors of tourism carbon footprint: A bibliometric analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Ullah, S.; Razzaq, A.; Cai, J.; Adebayo, T.S. Unleashing the dynamic impact of tourism industry on energy consumption, economic output, and environmental quality in China: A way forward towards environmental sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, R.; Scott, D.; Abegg, B.; Pons, M.; Aall, C. A critical review of climate change risk for ski tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1343–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, T.; Cierjacks, A.; Ernst, R.; Dziock, F. Direct and indirect effects of ski run management on alpine Orthoptera. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, N.; Scott, D.; Steiger, R. Sustainability of snowmaking as climate change (mal)adaptation: An assessment of water, energy, and emissions in Canada’s ski industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 1613–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.; Abegg, B.; Mailer, M.; Stampfl, P. Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Resulting From Tourism Travel in an Alpine Setting. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.Y.; Cho, W.; Hong, S.-H. Estimating the annual carbon budget of a weekend tourist resort in a temperate secondary forest in Korea. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Fang, W.; Yu, L.; Chuangxin, L.; Bing, X.; Ke, Z.; Junzhi, D.; Leer, C.; Suocheng, D. Ecological Carrying Capacity and Ecological Footprint of Ski Tourism: A Case of North Slope Region of Tianshan Mountain. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 5551–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cernaianu, S.; Sobry, C.; Liu, X. Ski Tourism: A Case Study as a Booster for the Economic Development of Chongli, in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Lenzen, M.; Liu, B.-J. The national tourism carbon emission inventory: Its importance, applications and allocation frameworks. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Dai, J.; Ma, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. How to decouple tourism growth from carbon emissions? A case study of Chengdu, China. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Gössling, S.; Hem, L.E.; Iversen, N.M.; Walnum, H.J.; Scott, D.; Oklevik, O. Can Norway become a net-zero economy under scenarios of tourism growth? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Higham, J. Overcoming information asymmetry in tourism carbon management: The application of a new reporting architecture to Aotearoa New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Peeters, P. Can tourism be part of the decarbonized global economy? The costs and risks of alternate carbon reduction policy pathways. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. International tourism and climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Dolnicar, S. A review of air travel behavior and climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2023, 14, e802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Challenges of tourism in a low-carbon economy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Clim. Chang. 2013, 4, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Moyle, B.D.; Moyle, C.-L.J.; Zhong, Y.; Shi, S. Drivers of carbon emissions in China’s tourism industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, S.; Gedikli, A.; Cevik, E.I.; Erdoğan, F. Eco-friendly technologies, international tourism and carbon emissions: Evidence from the most visited countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 180, 121705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. Global tourism vulnerability to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Hu, L.; Ma, Y.; Bu, H. How Ski Tourism Involvement Promotes Tourists’ Low-Carbon Behavior? Sustainability 2023, 15, 10277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Matthews, L.; Scott, D.; Del Matto, T. Using vehicle monitoring technology and eco-driver training to reduce fuel use and emissions in tourism: A ski resort case study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polderman, A.; Haller, A.; Viesi, D.; Tabin, X.; Sala, S.; Giorgi, A.; Darmayan, L.; Rager, J.; Vidovič, J.; Daragon, Q.; et al. How Can Ski Resorts Get Smart? Transdisciplinary Approaches to Sustainable Winter Tourism in the European Alps. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y. A framework to account for the tourism carbon footprint at island destinations. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Cadarso, M.A.; Driml, S. Tourism carbon footprint inventories: A review of the environmentally extended input-output approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 82, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, C.; Lin, P.-C.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Dolnicar, S. Assessing the carbon footprint of tourism businesses using environmentally extended input-output analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Jiang, X.; Cui, C.; Skitmore, M. BIM-based approach for the integrated assessment of life cycle carbon emission intensity and life cycle costs. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Drakeman, D. Measuring the carbon footprint of wine tourism and cellar door sales. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Lund-Durlacher, D. Tourist accommodation, climate change and mitigation: An assessment for Austria. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. Res. Plan. Manag. 2021, 34, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Steiger, R.; Rutty, M.; Pons, M.; Johnson, P. Climate Change and Ski Tourism Sustainability: An Integrated Model of the Adaptive Dynamics between Ski Area Operations and Skier Demand. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).