Abstract

The growing proportion of older adults has created significant societal pressure for sustainable, inclusive solutions that enhance health, autonomy, and well-being in old age. Smart elderly care has therefore emerged as a multidisciplinary research frontier at the intersection of technology, health, and social sustainability. This study provides a comprehensive systematic review to map and conceptualize its evolving landscape in the digital era. Following the PRISMA guidelines, 55 peer-reviewed articles published in the Web of Science database were analyzed using document co-citation analysis and natural language processing-based content analysis, utilizing CiteSpace and Leximancer for implementation. The findings reveal that existing studies have predominantly focused on technology acceptance and adoption among older adults, with quantitative approaches such as Structural Equation Modeling within the Technology Acceptance Model framework being most frequently used. Building on these insights, the review identifies five key directions for advancing sustainable wellbeing: (1) conceptual clarification and operationalization of smart elderly care, (2) theoretical integration across disciplines, (3) examination of influencing factors shaping user engagement, (4) evaluation of social and well-being outcomes, and (5) methodological and disciplinary diversification. By synthesizing fragmented knowledge into a coherent framework, this study contributes to the understanding of smart elderly care as a critical component of sustainable aging societies and lays the groundwork for future academic inquiry and policy innovation.

1. Introduction

The accelerating trend of population aging is leading to significant demographic shifts that pose serious challenges to traditional healthcare and social support systems, creating an imbalance between care demands and available caregivers and placing unprecedented pressure on healthcare system quality [1]. Ongoing advancements in AI, IoT, and machine learning technologies empower smart elderly care to better optimize, preserve, and enrich the quality of services delivered to older adults [2]. Smart elderly care emerges as a crucial response to these challenges, offering technology-enhanced approaches that improve diverse facets of older adults’ health and overall well-being [3,4]. Smart elderly care can streamline daily activities for elderly individuals, enhance quality of life through increased autonomy, and deliver timely care interventions [3]. The global smart elderly care market was valued at USD 4.2 billion in 2024 and is expected to expand to USD 12.8 billion by 2033, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.8% [5].

Recent studies on smart elderly care have investigated multiple and varied research concerns [6], from technology development and performance optimization to user acceptance and behavioral responses. This multidisciplinary research spans medical informatics, information systems, and human–computer interaction studies, with particular attention to user behavior and technology acceptance among elderly populations. Social science researchers have increasingly focused on understanding the behavioral factors influencing smart elderly care adoption and usage patterns. Given this expanding research landscape, a systematic examination of the field’s intellectual structure and research trajectories becomes essential. Systematic reviews play a vital role in consolidating existing knowledge and clarifying the evolution of a research field. As highlighted by prior studies [7,8], such reviews help scholars trace major trends, identify underexplored areas, and formulate future research directions.

Despite the expanding body of literature on smart elderly care, the contours of this research domain remain insufficiently defined [9]. An examination of previous review studies highlights three notable deficiencies. The first is the absence of a comprehensive and coherent understanding of the theoretical foundations underpinning smart elderly care. Most previous studies have been limited to reviewing a certain perspective, such as the effects of socially assistive robots [10], ethical conflicts issues [11], specific application scenarios [12], and AI-assisted design [13]. Second, the review articles largely concentrate on specific technological applications rather than examining the broader theoretical and methodological foundations of the field. Third, existing reviews predominantly employ a qualitative literature analysis method and are confined to a specific topic within smart elderly care [14]. Although bibliometric attempts have been made to map trends in the field [15], rigorous quantitative analyses of cluster patterns, thematic evolution, and intellectual structures remain limited. These constraints reduce the analytical rigor and broader applicability of current review outcomes.

To address these research gaps, this study provides a systematic and extensive assessment of the literature surrounding smart elderly care, drawing from multiple disciplines to provide a holistic understanding of this evolving field. The objective is to elucidate the intellectual foundations, identify cutting-edge research fronts, and highlight key themes that have emerged within this body of work. Accordingly, the review examines the following four questions:

- (1)

- What intellectual bases support the field of smart elderly care?

- (2)

- What research fronts have formed within this domain?

- (3)

- What thematic foci dominate current scholarship?

- (4)

- What future research pathways are needed to advance the field?

To answer these questions, 55 systematically screened articles were analyzed using bibliometric and content analytic approaches. Co-citation analysis, adopted as the main bibliometric method, examined citation networks to reveal the intellectual landscape and structural attributes of smart elderly care research. This methodological integration enhances analytical rigor and provides both quantitative insights and comprehensive coverage of this emerging domain [16,17]. As elderly–technology interaction represents a critical area within human–computer interaction and information systems research, this study contributes a theoretically grounded research agenda based on intellectual structure analysis and identified research gaps.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Data retrieval was conducted using the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection database with a five-year timeframe (2020–2024), targeting literature published between 1 January 2020, and 31 December 2024. This five-year period was chosen strategically as it captures the intensified global focus on aging populations and the corresponding surge in technological solutions addressing demographic challenges [18]. Given its reputation for high-quality and trustworthy coverage of authoritative multidisciplinary scholarship [19], WoS was selected as the primary database, as it remains one of the most influential sources available. The multidisciplinary coverage of WoS ensures comprehensive representation of diverse research perspectives essential for cross-disciplinary synthesis. Consistent with the systematic review’s objective to integrate knowledge across multiple disciplines [7], the research strategy avoided a focus on any particular research field.

To achieve comprehensive coverage of smart elderly care research, studies were included if they met three criteria: (1) highly relevance to technologies supporting elderly care or healthcare, (2) a focus on research involving the elderly, and (3) publication in English-language peer-reviewed journals. Based on these criteria, the following search string was developed: (“older*” OR “elder*” OR “senior*” OR “ageing*” OR “aging*”) AND (“technolog*” OR “smart” OR “information system*” OR “intelligen*”) AND (“care *” OR “* care”). The search encompassed multiple disciplines, including health care, geriatrics gerontology, medical informatics, business, economics, information systems, psychology, engineering, and computer science. The review included exclusively peer-reviewed journal publications, consistent with established norms in systematic review research [20].

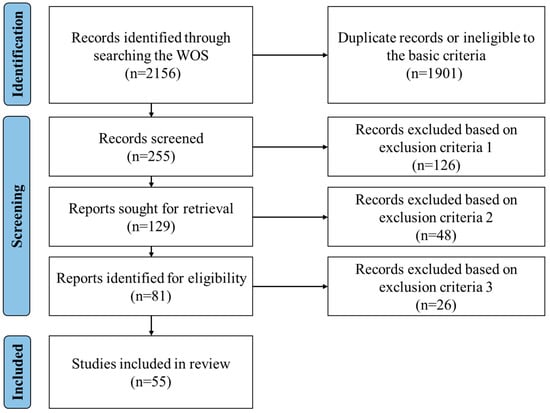

To ensure a transparent selection process, the study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations (details can be found in the Supplementary Materials) [21]. PRISMA originates in healthcare research and has been widely adopted for reviewing information systems literature [22]. The two authors independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. No automation tools used. As illustrated in Figure 1, the final articles were identified through a sequence of three screening stages.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Exclusion criterion 1 eliminated studies whose primary emphasis was on the technical or engineering side of smart elderly care. As the objective of this review is to explore the broader social implications rather than technological specifications, excluding technical-focused work, as recommended in previous systematic reviews (e.g., Frizzo-Barker et al. (2020) [23]), ensures that the included articles remain within the intended analytical scope.

Exclusion criterion 2 was applied to eliminate articles that failed to place older adults at the core of their inquiry. Studies focusing solely on related groups (such as physicians, caregivers, and officials) without fully exploring the elderly themselves were not included.

Exclusion criterion 3 concerned the evaluation of the methodological and publication quality of the eligible studies [24]. The SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) was adopted as the primary metric for this assessment, as it groups journals into four quartiles and reflects their influence based on the weighted average number of citations received over the previous three years, adjusted by the prestige of the citing sources [25]. To maintain a rigorous quality threshold, only articles appearing in Q1 or Q2 journals (representing the top half of SJR rankings) were retained. Applying such quality thresholds ensures that the synthesis draws exclusively from robust and influential scholarly work [7], as higher-ranked publications typically make more substantial contributions to academic progress [26]. Data extraction was performed independently by both authors using standardized criteria and later reconciled through consensus. In total, 55 studies met all inclusion requirements and were designated as focal articles (see Appendix A). These full-text papers, along with their reference lists, served as the core dataset for subsequent analyses.

2.2. Data Analysis

As research on smart elderly care cuts across various disciplines (e.g., healthcare, business, information systems, psychology, and computer science), a combination of bibliometric analysis and content analysis was adopted in this study. The integrated methods offer significant advantages for literature review research [27,28], enabling efficient analysis of large datasets that would be challenging to manage manually while minimizing subjective bias.

2.2.1. Co-Citation Analysis and Its Implementation in CiteSpace

A document co-citation analysis (DCA) was initially carried out to provide comprehensive insights into the structural configuration, intellectual underpinnings, and research fronts within the smart elderly care literature. The approach incorporates identifying significant references, examining the structural features of co-citation clusters, and generating automated cluster labels using terms taken from the titles, abstracts, and index keywords of focal articles [29]. Together, these steps expose the intellectual foundations of smart elderly care research and help delineate its emerging research fronts.

The analytical procedures were implemented with CiteSpace, a well-established knowledge visualization software in social science and health care research, designed to facilitate the exploration of knowledge structures and research field evolution [30,31]. A node’s betweenness centrality in CiteSpace represents its capacity to act as an intermediary in the network’s information exchange [32], which facilitates the identification of highly influential or transformative works. Additionally, research fronts within co-citation clusters can be characterized by the automated cluster labeling in CiteSpace through extracting cluster descriptors from the titles, abstracts, or keywords of the citing articles [29].

2.2.2. Content Analysis and Its Implementation in Leximancer

Content analysis of the focal articles was subsequently conducted to further explore the data and identify the underlying concepts and themes. As a systematic technique for generating replicable and valid inferences from textual materials [33], content analysis enables researchers to detect overarching themes, core meanings, and recurring patterns within qualitative datasets. The use of automatic content analysis is particularly valuable in this context, as it reduces several challenges inherent in traditional qualitative approaches, including the need to justify coding decisions, establish intercoder reliability, and substantiate interpretive claims [34].

The analysis was implemented via Leximancer, a sophisticated natural language processing (NLP) software based on Bayesian theory and widely used in social science research to analyze, interpret, and visualize intricate textual data [28]. Leximancer quantifies frequency and co-occurrence of concepts within a text corpus, generating a comprehensive concept map. Its process is deterministic, producing an explicit and reproducible coding that accurately represents the semantics and interconnections within the textual data [34]. Following the procedures outlined by Indulska et al. (2012) [35], the titles, abstracts, and keywords of all 55 focal articles were imported into Leximancer. The software then generated a concept map that visually illustrated the key concepts and their interconnections. After the initial automated extraction, the research team examined the map to interpret the contextual meaning of each identified concept and traced the relevant articles for deeper qualitative interpretation [35].

The content analysis process began with an automatic, corpus-level analysis using LexiPortal in Leximancer 5.0.261, which grouped concepts into themes based on their relevance and associative strength. The spatial proximity of circles on the map reflected the degree of relational closeness between themes [36]. Subsequently, the researchers reviewed these themes and co-occurrence patterns, conducting an in-depth interpretation by revisiting the underlying articles to uncover contextual nuances [35]. In addition, a manual cross-validation was performed by comparing the Leximancer output with independent literature analysis to enhance the credibility and validity of the findings [36].

3. Results

3.1. Findings of the Bibliometric Analysis

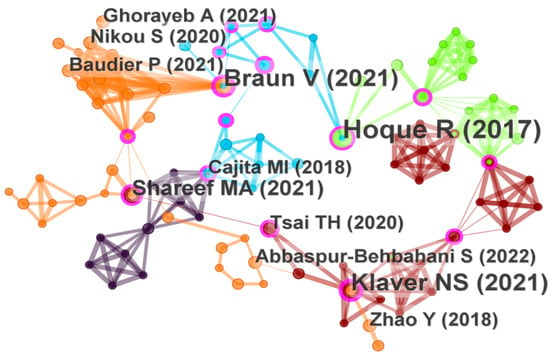

CiteSpace analysis verified 3333 references within the focal literature, achieving a validation accuracy of 99.17%. A hybrid network was constructed through DCA, comprising 157 nodes and 394 links (see Figure 2). In this visualization, each node represents a cited reference, labeled by the first author and year of publication. Concentric rings around each node illustrate the citation history of the reference. Within the network, landmark references with large citation rings represent the most frequently cited works, while those marked by purple rings exhibit high betweenness centrality, indicating their role in connecting different parts of the knowledge structure. References with landmark status or high betweenness centrality serve as key indicators of the intellectual foundations within smart elderly care research. As shown in Table 1, the references are listed in descending order based on citation count.

Figure 2.

DCA network of smart elderly care research. (The figure includes key references such as Hoque and Sorwar (2017) [37], Klaver et al. (2021) [38], Cajita et al. (2018) [39], Zhao et al. (2018) [40], Shareef et al. (2021) [41], Ghorayeb et al. (2021) [42], Tsai et al. (2020) [43], Nikou et al. (2020) [44], Abbaspur-Behbahani et al. (2022) [45], Baudier et al. (2021) [46], and Braun and Clarke (2021) [47]).

3.1.1. Landmark References as Intellectual Bases

Table 1 presents the top 12 landmark references that demonstrate both high citation frequency and high betweenness centrality, representing works that are not only frequently cited but also serve as critical intellectual bridges within smart elderly care research. These references span multiple disciplinary domains: Medical Informatics (4), Information Systems (4), Healthcare (2), Computer Science (1), and Research Methods (1). The landmark references investigate diverse smart elderly care technologies, such as mHealth applications [37,38,39,40], homecare technologies [41,42], wearable devices [43,48], health information technology [49], telemedicine solutions [46], and gerontechnology innovations [50].

Table 1.

Top 12 landmark references.

Table 1.

Top 12 landmark references.

| Rank | Citation Count | Centrality | Authors (Year) | Fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 0.21 | Hoque and Sorwar (2017) [37] | Medical Informatics |

| 2 | 5 | 0.30 | Braun and Clarke (2021) [47] | Research method |

| 3 | 5 | 0.20 | Klaver et al. (2021) [38] | Healthcare |

| 4 | 4 | 0.10 | Shareef et al. (2021) [41] | Information Systems |

| 5 | 3 | 0.18 | Cajita et al. (2018) [39] | Medical Informatics |

| 6 | 3 | 0.08 | Baudier et al. (2021) [46] | Information Systems |

| 7 | 3 | 0.08 | Tsai et al. (2020) [43] | Medical Informatics |

| 8 | 3 | 0.05 | Ghorayeb et al. (2021) [42] | Computer Science |

| 9 | 3 | 0.02 | Zhao et al. (2018) [40] | Information Systems |

| 10 | 2 | 0.23 | Kavandi and Jaana (2020) [49] | Healthcare |

| 11 | 2 | 0.22 | Zhang et al. (2017) [48] | Medical Informatics |

| 12 | 2 | 0.21 | Teh et al. (2017) [50] | Information Systems |

To elucidate the intellectual base indicated by the twelve key references, the study reviewed the theories applied and the independent and dependent variables examined in these works. The intellectual foundation established through these landmark references primarily centers on technology adoption frameworks, with particular emphasis on understanding elderly users’ behavioral responses to smart elderly care technologies. The predominant focus has been on adoption intention [38,39,40,41,46,48,50]. Hoque and Sorwar (2017) [37] uniquely examined both actual adoption behavior and intention concurrently, bridging the intention–behavior gap that is critical in elderly technology adoption research.

Among the theoretical frameworks employed, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [51] and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) [52] emerge as the most frequently cited theoretical frameworks. These theoretical frameworks emphasize the influence of user perceptions and motivational factors on behavioral outcomes. Consequently, core constructs from these models—including perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence—have received substantial empirical attention.

Beyond these core constructs, these landmark references have explored the factors influencing elderly adoption of such smart elderly care technologies, which can be categorized into four dimensions. First, personal health conditions, which encompasses health-related perceptions and beliefs that influence technology adoption decisions, including perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, health belief, personal ability and control [40,41,44]. Second, personal traits, which relate to individual psychological and behavioral characteristics, such as technology anxiety, resistance to change, trust, perceived risk, attitude, self-efficacy, personal innovativeness, willingness to learn [37,38,39,43,46]. Third, technology attributes include factors such as technological uncertainty and reliability, availability, perceived ubiquity [41,42,48]. Finally, social context encompasses external influences including price/cost value, power posing, informational reference group influence, and subjective norm [48,49,50].

Methodologically, quantitative approaches utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM) dominate the landmark references, with fewer studies employing qualitative designs that utilize thematic analysis of interview data (i.e., Ghorayeb et al. (2021) [42]). Braun and Clarke (2021) [47] provide a framework for evaluating thematic analysis as the most cited methodological reference, highlighting its significance in qualitative method within smart elderly care research.

3.1.2. Six Knowledge Clusters: Mapping the Research Front Structure

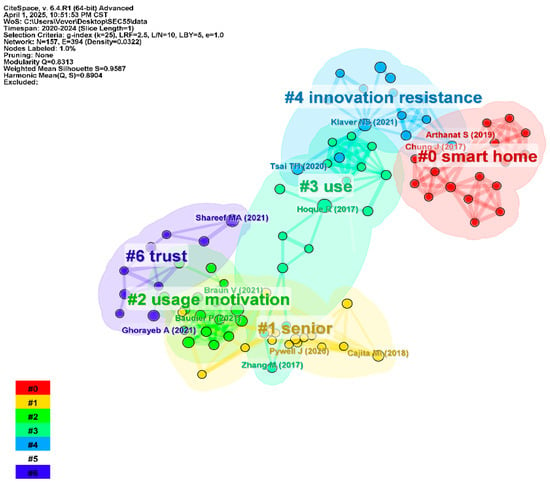

To explore the structure of the research fronts in smart elderly care, this study examined clusters of cited references using CiteSpace, identifying six main clusters with labels derived from keywords using the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) method. LLR method extracts statistically significant terms from the citing articles within each cluster and selects those that best differentiate one knowledge cluster from another. Consequently, the resulting labels often reflect data-driven co-occurrence patterns rather than manually curated thematic concepts. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of research on smart elderly care technologies, papers within the same cluster frequently address multiple dimensions simultaneously. These LLR-generated labels should therefore be understood as representative indicators of the intellectual focus of each research community, rather than strict conceptual boundaries imposed by the authors.

The analysis produced a modularity value of 0.8313, substantially exceeding the threshold of 0.3, indicating that the network is well-organized with clearly defined cluster boundaries. The mean silhouette value of 0.9587, close to 1, indicates that the clusters exhibit high internal consistency and homogeneity. As shown in Figure 3, some overlap occurred between clusters as all focal articles were highly related to smart elderly care and most cited the landmark references.

Figure 3.

Document co-citation clusters. (The figure includes key references such as Hoque and Sorwar (2017) [37], Klaver et al. (2021) [38], Cajita et al. (2018) [39], Zhao et al. (2018) [40], Shareef et al. (2021) [41], Ghorayeb et al. (2021) [42], and Tsai et al. (2020) [43], Baudier et al. (2021) [46], Braun and Clarke (2021) [47], Zhang et al. (2017) [48], Arthanat et al. (2019) [53], Pywell et al. (2020) [54] and Chung et al. (2017) [55].)

Research fronts within document co-citation clusters are identified and defined by specific terms extracted from citing articles, serving as indicators of emerging trends and focal research areas [29]. Therefore, the research fronts in smart elderly care appeared as six cluster titles: smart home (#0), senior (#1), usage motivation (#2), use (#3), innovation resistance (#4), and trust (#6). These clusters collectively reveal the field’s primary focus on understanding and addressing the complex behavioral dynamics surrounding elderly users’ technology use and resistance patterns. By applying the LLR method to the titles, keywords, and research fields of the focal articles, a set of representative terms was generated. Table 2 synthesizes these terms to clarify the thematic focus of each cluster.

Table 2.

Knowledge clusters and LLR-derived label terms.

Observing the title and keywords that appeared in smart home (#0), these produced “ethics”, “assistive technology”, and “ambient-assisted living”. Astell et al. (2020) [56] and Arthanat et al. (2019) [53] were cited the most in #0 as these studies explored factors influencing their acceptance and emphasized the potential of these technologies to support aging in place and improve the quality of life for the elderly. This cluster spans medical informatics, healthcare, and business research fields.

The main title and keywords in the senior (#1) contained “engagement”, “multimorbidity”, and “mobile health”. Cajita et al. (2018) [39], Cajita et al. (2017) [57], and Pywell et al. (2020) [54] were the most cited in #1 as they focused on the factors influencing the adoption of mobile health (mHealth) technology among older adults, exploring both facilitators and barriers to its use in different health contexts. The research fields encompass medical informatics, business, and healthcare.

When examining title and keywords that appeared in usage motivation (#2), there were “postadoption usage pattern”, “interviews”, and “digital health”. Braun and Clarke (2021) [47] was the most cited in #2, contributing methodological insights on thematic analysis and qualitative research rigor. Ali et al. (2021) [58], and Baudier et al. (2021) [46] were the second most cited in #2 as they examined the implementation of digital healthcare technologies with a focus on stakeholder interactions and acceptance factors. This cluster draws from the fields of management, engineering, and healthcare.

The main title and keywords in use (#3) were “UTAUT model”, “ehealth”, and “acceptance”. Hoque and Sorwar (2017) [37] as well as Kavandi and Jaana (2020) [49] were the most cited in #3 as they focused on the factors influencing the adoption/use of health-related technologies among the elderly population. The research fields involve public health, environmental science, and business.

The main title and keywords in innovation resistance (#4) were “mhealth application”, “perceived risk”, and “inhibitor perspective”. Talukder et al. (2021) [59], Klaver et al. (2021) [38], and Califf et al. (2020) [60] were the most cited in #4 as they investigated the barriers of technology on healthcare users from inhibitor perspective. The research fields involve computer science, telecommunications, and public health.

The main title and keywords in trust (#6) were “automation”, “human behavior”, and “fear”. Shareef et al. (2021) [41], Ghorayeb et al. (2021) [42], and Khosla et al. (2021) [61] were the most cited in #6 as they focused on the acceptance and impact of technology-based solutions in elderly care, examining trust, personal characteristics, and social interaction as key factors. The research fields involve psychology, healthcare, and computer science.

3.2. Key Findings from the Content Analysis

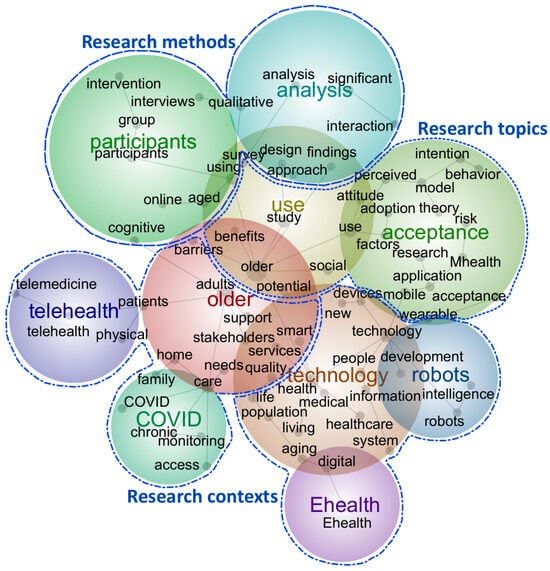

To improve the precision of concept extraction, the edit function was used to consolidate lexical variations, including singular and plural forms, case-sensitive versions of identical words, and synonymous terms (e.g., technology/technologies, patient/patients, service/services, interview/interviews, system/systems, ACCEPTANCE/acceptance, elder/elderly/older, and participants/respondents). After completing this refinement process, the concept map was generated based on the frequency and co-occurrence of terms, with larger circles representing more prominent themes. As illustrated in Figure 4, the concept map delineates the key concepts, themes, and interconnections of the 55 focal articles.

Figure 4.

Concept map of the 55 focal articles. (Note: Dots represent concepts automatically extracted from the text by Leximancer. Dot size indicates concept connectivity, calculated as the sum of co-occurrence counts between each concept and all other concepts. Colored circles represent themes, which are clusters of related concepts. Theme dominance is indicated by color intensity, with warmer colors representing more dominant themes in the dataset).

Consequently, the content analysis reveals three research foci: “research topics”, dominated by older adults’ use and acceptance of smart elderly care technologies; “research contexts”, characterized by diverse interactions between older people and technologies, especially telehealth and robots; and “research methods”, involving both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The subsequent analysis of focal works builds upon comprehensive examination of the concept map and detailed review of textual excerpts associated with each identified concept.

The research topic area encompasses two dominant themes labeled as “use” and “acceptance”, with concepts including adoption, attitude, intention and behavior. This suggests a strong focus on factors influencing older adults’ technology acceptance within the smart elderly care literature. Further examination of these articles reveals that influential factors can be categorized into three dimensions: external environment factors, technology characteristics, and individual characteristics.

External environmental characteristics have received comparatively limited attention in the literature. Studies examining this dimension focus on social relationships [41,62], available facilities [58,62,63,64], service availability [62,63,65], and resources accessibility [66].

Technology characteristics encompass factors directly related to design, functionality, and usability. The literature extensively explores perceived usefulness [67,68,69], perceived ease of use [67,68,69], perceived reliability [41,69,70], device quality [59], technology interactivity [68], price value [69], and gamification [71].

Individual characteristics relate to older adults’ demographics, beliefs, and psychological traits. Key factors include personal innovativeness [61,63], health status [58,72,73], self-perception of ageing [74], emotional attachment [74], attitude [68,73], technology anxiety [68,69], habit [75], digital literacy [76,77,78], life satisfaction [79], socioeconomic factors such as household income and employment status [58,79], family structure factors including number of children and frequency of children visiting parents [73]. Notably, some studies incorporate hybrid constructs that bridge multiple categories, such as trust [41,80] and technology readiness [68], which encompass both technological and individual characteristic dimensions.

Further analysis of the text, corresponding to the “theory” concept in the map, reveals that while technology acceptance and adoption theories dominate the literature, several additional theoretical frameworks have been employed to investigate older adults’ perceptions of smart elderly care technologies. Dominant theoretical frameworks include TAM (e.g., Askari et al. (2020) [62], Frishammar et al. (2023) [78], Li et al. (2024) [81]) and UTAUT (e.g., Rój (2022) [82], Wang et al. (2023a) [83]), focusing on understanding behavioral intentions. Alternative theoretical approaches have been applied to a lesser extent, offering diverse perspectives on older adults’ technology interactions. These include innovation resistance theory (e.g., Leung et al. (2024) [84]), which examines barriers to technology adoption; automation trust model (e.g., Shareef et al. (2023) [85], Shareef et al. (2021) [41]), which investigates trust formation in automated systems; theory of consumption values (e.g., Talukder et al. (2021) [59]), which explores value-based decision-making;, social cognitive theory (e.g., Kim and Han (2021) [86]), which examines the role of self-efficacy and social influences; and information systems success model (e.g., Ko and Chou (2020) [70], Wang et al. (2021) [74]), which evaluates system effectiveness and user satisfaction.

The research contexts encompass two complementary perspectives: user-centered contexts, examining how older adults interact with technologies such as telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, and technology-centered contexts, focusing on specific solutions including robots and e-health platforms for elderly care. Prominent concepts such as “new”, “information”, “system”, “intelligence”, and “device” reveal a strong emphasis on innovative elderly care practices associated with digital services. The concept map demonstrates concentrated attention on telehealth, e-health, and robots, with smart home technologies also receiving significant research focus. Further examination of the articles reveals investigation of diverse innovative smart elderly care applications, including wearable health technologies, mobile health (mHealth) solutions, online healthcare communities (OHCs), virtual reality (VR) interventions, and in-home monitoring systems.

The research methods analysis reveals that smart elderly care research is predominantly characterized by quantitative approaches, as evidenced by concepts such as “survey”, “significant”, “intervention”, “interaction”, and “analysis” in the concept map. Further examination of the literature demonstrates a marked preference for structural equation modeling (SEM) with data collected through questionnaire surveys, while experimental designs have received comparatively limited attention (e.g., Chiu et al. [87]). Qualitative methodologies constitute a smaller but notable portion of the research landscape, employing focus groups [42,88], semi-structured interviews [89,90,91], and case studies [92]. Mixed-methods designs remain underutilized, with relatively few studies adopting this approach [78,84,93].

4. Discussion

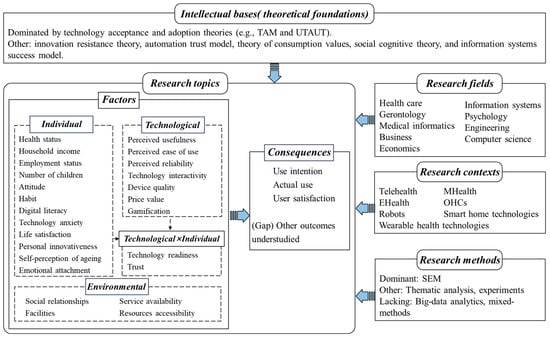

Results from CiteSpace and Leximancer were mutually validating and jointly answered the four research questions. Regarding RQ1 (the intellectual bases of smart elderly care research), both analyses show that technology acceptance and adoption theories constitute the dominant theoretical foundations in this field. In relation to RQ2 (the research fronts of smart elderly care research), the co-citation clusters reveal several emerging fronts, including “smart home”, “senior”, “usage motivation”, “use”, “innovation resistance”, and “trust”. Addressing RQ3 (the key focus of the existing literature), the content analysis identifies three major dimensions: research topics, research contexts, and research methods. The research topics primarily focus on factors leading to use and acceptance. The research contexts are diverse in technologies, with a particular emphasis on telehealth, robots, and ehealth in older adults’ lives. The research methods are dominated by quantitative approaches, especially SEM. Complementing these are qualitative approaches, with thematic analysis emerging as the predominant qualitative methodology for exploring lived experiences and contextual nuances. Finally, to respond to RQ4 (future research avenues), the following sub-sections synthesize insights from the DCA and content analysis results to propose multiple research directions and opportunities. Figure 5 summarizes smart elderly care research in the current literature.

Figure 5.

An overview of smart elderly care research in the literature. (Note: TAM = Technology Acceptance Model; UTAUT = Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology; SEM = Structural Equation Modeling; mHealth = mobile health; OHCs = Online Health Communities).

4.1. Operationalizing of Smart Elderly Care

Smart elderly care is a multifaceted entity and has been conceptualized variously across the literature. Scholars have conceptualized it as a technological infrastructure [93], an integrated service delivery system [2], a comprehensive care ecosystem [84], a quality-of-life enhancement mechanism [94], or a combination of these concepts [73]. In practice, smart elderly care manifests in various technological forms, such as mhealth applications [71], assistive robots [95], wearables [59], monitors [42], virtual realities [87], and gerontechnology innovations [50].

Reflecting its multifaceted nature, the literature exhibits inconsistency in how the age of the elderly population is defined across different implementation contexts. Although the United Nations defines older persons as those aged 65 and above [18], the operations in the literature often use younger thresholds, such as 50 and above [75], 55 and above [93], or 60 and above [84], depending on the technological context, level of service integration, or intended care outcomes.

Given these varying age thresholds and the expanding scope of smart elderly care technologies, those approaching old age—often referred to as the “pre-elderly” or “near-elderly”—emerge as a key demographic deserving attention in future research. As they constitute the next generation of users, understanding their attitudes, expectations, and readiness is critical for both technology design and long-term adoption strategies.

4.2. Intellectual Base of Smart Elderly Care

As smart elderly care research has been studied in various fields, the intellectual base theories also vary. Technology acceptance and adoption theories have been most prominently employed. Specifically, TAM [51] and UTAUT [52] have been widely used as a basis for research on older adults’ adoption and use of smart elderly care technologies.

In addition, several psychological theories have contributed to understanding older adults’ adoption of smart elderly care technologies, including social cognitive theory [96], self-determination theory [97], and attachment theory [98]. More recently, new theoretical models have emerged to capture the uniqueness of older adults. For example, within the consumer behavior paradigm, the automation trust model (ATM) was developed to understand the behavioral intentions of elderly people to adopt automation systems that replace human support in routine activities, including healthcare [41,85]. It is anticipated that theoretical developments tailored to understand the specific elderly’s adoption of smart elderly care will further proliferate.

However, there is a need to expand on other research fields and theories, not just focusing on the adoption issues. Innovation resistance theory [99] offers valuable insights into why some older adults resist or reject smart elderly care technologies. Furthermore, integrating perspectives from the service innovation literature (e.g., Lusch and Nambisan [100]) may be useful to further explore how technology-enabled services can be more effectively designed, implemented, and evaluated, thereby extending the understanding of smart elderly care effectiveness beyond mere adoption outcomes.

4.3. Factors Related to Smart Elderly Care Research Fronts

In smart elderly care research, technological factors have received the most extensive attention. Various studies have examined key technological characteristics, including technology acceptance dimensions such as ease of use and usefulness [78], technology interactivity [68], and gamification [71]. In addition to these perceptual attributes, concrete technical parameters—such as the weight of wearable devices, the type of materials used (e.g., plastic, silicone, or metal), skin-friendliness, and comfort during prolonged use—also play a crucial role in shaping elderly users’ acceptance. Older adults are particularly sensitive to factors such as heaviness, hardness, or potential allergic reactions, and their attitudes toward these specific device parameters significantly influence perceived comfort, safety, and ultimately, adoption intentions.

However, research on the ethical considerations in smart elderly care development remains insufficient. This is concerning as unethical issues may arise, including data breaches in elderly monitoring systems and unauthorized sharing of older adults’ personal health information, inadequate consent mechanisms, and lack of transparency in technology-based decision-making. Furthermore, although generative AI and large language models such as ChatGPT have become prevalent in big data analysis, their application in older adult research within the smart elderly care domain remains limited, representing a critical research priority that warrants future investigation.

Current scholarship includes only a small number of studies addressing environmental factors. Older adults, as a vulnerable demographic group [101], need more association with the external environment. The integration of more environmental factors into smart elderly care research needs to be further studied. Whether in virtual or physical realms, the surrounding social environment inevitably shapes individuals’ cognitive and behavioral responses. For example, older adults generally identify themselves as members of family units, community groups, or peer networks and regard these groups as reference points when making technology-related decisions [102]. Consequently, it is crucial to investigate how external elements, including family support, community-level resources, cultural expectations, and social ties, affect older adults’ views of smart elderly care, especially in light of the intricate relationships among external environments, innovation features, and personal characteristics of older adults. Applying theoretical frameworks such as the socio-ecological model [103] or social network theory [104] would be beneficial to investigate these multifaceted external influences.

In addition, the role of individual characteristics in smart elderly care research has been researched as predictors [62,72] or moderators [63]. Various factors from individual aspect have been identified across two primary dimensions: demographic characteristics such as age, gender, health status, income level, and children supports [58,63,73]; and psychological factors such as attitudes, perceptions, and motivation [62,75]. An emerging perspective involves integrated constructs, such as technology readiness [68], which encapsulate both individual predispositions and perceived characteristics of the technology to explain older adults’ intentions to engage with smart elderly care technologies. Research indicates that technology designed for older adults requires careful consideration of age-specific attributes that distinguish them from younger counterparts, such as cognitive processing speed, physical limitations, and established care preferences. To identify unique characteristics specific to older adults that do not apply to younger demographics in smart elderly care contexts, substantial follow-up studies are needed to develop age-appropriate theoretical frameworks and intervention strategies.

CiteSpace and Leximancer did not identify emotions as a prominent theme in the literature, revealing an area deserving further attention. While emotions substantially affect older adults’ decision-making, this dimension has been largely overlooked in smart elderly care research [105,106]. Future work using neuroscience-based experimental techniques, including skin conductance, electroencephalography (EEG), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), could enhance understanding of older adults’ emotional and physiological responses to such technologies. Additionally, identifying diverse emotional typologies among older adults when encountering smart elderly care technologies may influence or predict their behaviors, representing a promising research avenue for future exploration.

4.4. Consequences of Smart Elderly Care

Adoption intention, satisfaction, and actual usage emerge as the most frequent dependent variables in smart elderly care research. It is indisputable that these variables play a pivotal role in consumer decision outcomes, as they serve as direct measures of potential users’ interest in and openness toward adopting a new information system [107]. More recently, user engagement and retention have started to appear in consumer and information systems research [108,109]. Since sustained engagement has significant implications for long-term care outcomes and health improvements among older adults, it warrants closer examination in future research.

However, there is a notable research gap in examining negative outcomes. Specifically, the opposite side of adoption, including resistance, non-adoption, and discontinuance among older adults, requires further exploration. Older adults may resist the adoption of smart elderly care for various reasons that lead to non-adoption, such as perception of difficulties in use, preference for social participation, physical constraints to operate, and security/risk concerns. As Richetin et al. [110] argue, non-adoption represents a distinct phenomenon that cannot be simply conceptualized as the opposite of adoption. Therefore, applying the findings from older adults’ adoption of smart elderly care innovations in reverse may not explain the non-adoption phenomenon. This limited attention to older adults’ non-adoption is particularly concerning, as information technology acceptance among older adults remains a persistent challenge [111]. Understanding what drives older adults to reject or abandon smart care technologies is crucial for developing more inclusive and age-appropriate solutions.

Additionally, current research may not capture the full complexity of older adults’ experiences with smart elderly care technologies. Future studies should explore whether additional outcome measures are required to comprehensively assess the diverse range of older adult experiences with smart care technologies, potentially including measures of autonomy, dignity, social connectedness, and quality of life impacts.

4.5. Research Method and Field of Smart Elderly Care

Most studies on smart elderly care have employed SEM, typically relying on survey data collected from older adults. While this approach is valuable for establishing causal relationships and quantifying effect sizes and explanatory power, it is often constrained by limited sample sizes, which can affect the robustness and generalizability of findings. To address this limitation, big data analytics should be increasingly utilized to enhance validation and provide broader population insights.

In parallel, there is a growing need for in-depth qualitative investigations into how older adults perceive and interact with smart elderly care technologies. Such approaches can uncover nuanced experiences and identify complex drivers of both adoption and resistance that may not be captured through quantitative methods alone. Mixed-methods research is particularly well-suited to this domain, as it allows for a more comprehensive and systematic exploration of the multifaceted issues involved.

From a disciplinary perspective, current studies span a wide array of fields, including healthcare, gerontology, medical informatics, business, economics, information systems, psychology, engineering, and computer science. Looking forward, smart elderly care is likely to intersect more prominently with fields such as social policy and insurance, particularly as ethical, legal, and regulatory concerns come to the forefront. Addressing these interdisciplinary challenges requires future research to more explicitly engage with these emerging domains.

Several limitations must be noted. First, restricting data retrieval to the WoS database may have resulted in the exclusion of relevant studies indexed elsewhere, such as Scopus, PubMed, or IEEE Xplore. Second, by focusing on articles published between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2024, earlier foundational literature might not have been captured. Despite these constraints, supplementary reference and citation searches help lessen the chances of overlooking key contributions. Finally, while CiteSpace provides powerful bibliometric visualization tools, certain limitations in its user interface may hinder readability and interpretation.

5. Conclusions

By detecting research trends and examining the intellectual landscape via DCA and NLP-based content analysis, this study provides insights for future research development. The principal findings include the following: First, the field lacks conceptual consistency, with studies employing varying age thresholds for defining elderly populations rather than adhering to the United Nations standard, demonstrating a younger tendency. Moreover, no universally accepted definition of smart elderly care exists, making it difficult to establish standardized conceptual frameworks. Second, while research on smart elderly care has proliferated across healthcare, gerontology, medical informatics, information systems, and psychology, primarily grounded in technology acceptance and adoption theories (e.g., TAM and UTAUT), studies examining social policy, insurance, and legal dimensions remain insufficient. Third, research on how environmental factors shape the acceptance and evaluation of smart elderly care is comparatively scarce relative to studies emphasizing individual or technological dimensions. Moreover, discussions on privacy and ethical concerns remain inadequate. Accordingly, further research is required to propose measures that address these challenges and to incorporate methodological innovations that reinforce the robustness and credibility of findings.

This study contributes to moving beyond the technology-centric bias that has often shaped the smart elderly care and gerontechnology literature. Smart elderly care research across a wide range of domains, ranging from healthcare delivery, assistive technologies, home care services, social care, and telehealth to policy development, and insurance systems may benefit from this review. The findings offer holistic perspectives to understand older adults’ technology experiences and overcome the technology-centric bias that often overlooks user resistance and non-adoption behaviors. Researchers can improve the coherence of future work by connecting it to existing scholarship. This may involve framing studies around key dimensions of smart elderly care, including how it is defined and measured, what drives it, how it manifests, and what consequences it produces. They may also explore strategies to mitigate negative outcomes, apply diverse research methods to strengthen empirical validation, or pursue combinations of these approaches. Research might also follow a user-centered or technology-centered paradigm, with increasing emphasis on participatory design approaches that position older adults as co-creators rather than passive recipients of smart care technologies. This study’s central contribution is the extension of knowledge regarding future research directions in smart elderly care. The provision of empirically grounded pathways and interdisciplinary frameworks supports ongoing exploration of a field that holds substantial theoretical and practical significance amid global aging.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411357/s1, PRISMA checklist [112].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and software, J.L.; validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and B.W.; supervision, B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Scientific Research Laboratory of AI Technology and Applications, University of International Business and Economics (KYSYS-04).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAL | Ambient-Assisted Living |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ATM | Autonomous Trust Model |

| DHPs | Digital Healthcare Platforms |

| eHealth | Electronic Health |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| IRT | Innovation Resistance Theory |

| ISS model/IS success model | Information Systems Success Model |

| mHealth | Mobile Health |

| WHTs | Wearable Health Technologies |

| OHCs | Online Health Communities |

| PMT | Protection Motivation Theory |

| SARs | Socially Assistive Robots |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SMECS | Smart Medical and Elderly Care Systems |

| S–O–R | Stimulus–Organism–Response |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| UTAUT2 | Extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Focal articles.

Table A1.

Focal articles.

| Authors (Year) | Context | Age Range | Research Design | Main Related Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jeng et al. (2020) [89] | Smart bracelets | 60+ | Qualitative | Means–end chain theory, older adults’ perceived value (attribute functions, consequent benefits and value goals) |

| Jaana and Pare (2020) [67] | mHealth | 65+ | Quantitative | Expectation-confirmation theory, initial expectations, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, satisfaction, intention to continue |

| Vandemeulebroucke et al. (2020) [88] | Socially assistive robots (SARs) | 70+ | Qualitative | Older adults’ multidimensional perceptions (such as components of a techno-societal evolution, embeddedness in aged-care dynamics, and embodiments of ethical considerations) |

| Hawley et al. (2020) [113] | Telehealth | 65+ | Qualitative | Patient-perceived barriers (interest, access to care, access to technology, and confidence) |

| Askari et al. (2020) [62] | Medical apps | 65+ | Quantitative | TAM, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude toward use, subjective norm, sense of control, personal innovativeness, social relationships, self-perceived effectiveness, service availability, facilities, feelings of anxiety, intention to use |

| Verloo et al. (2020) [114] | Gerontechnology | 65+ | Qualitative | Older adults’ perception (preferring technologies related to their mobility and safety and those that would help slow down their cognitive decline) |

| Lin et al. (2020) [90] | mHealth | 58+ | Qualitative | TAM, perceived usefulness, ease of use, compatibility, technology anxiety, financial cost, and self-efficacy |

| Ko and Chou (2020) [70] | eHealth | 51+ | Quantitative | Information systems success model (ISS model), the five dimensions of service quality (tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy), and satisfaction with service quality |

| Kim and Han (2021) [86] | Health apps | 60+ | Quantitative | Social cognitive theory, healthcare technology self-efficacy, outcome expectations (including physical, social, and self-evaluative dimensions), privacy risk, self-regulatory behavior, and continuance intention |

| Huang et al. (2021) [66] | Gerontechnology | 60+ | Mixed-method | TAM, Health Behavioral Model (HBM), need factors (assessed need, perceived need), resources accessibility (cost, community services, health policy), predictive factors (personal characteristics, health belief), products characteristic (usability, reliability), and adoption intention |

| Wilson et al. (2021) [14] | eHealth | 60+ | Literature review | UTAUT2, barriers (a lack of self-efficacy, knowledge, support, functionality, and information provision about the benefits), and facilitators (active engagement, support for overcoming concerns privacy and enhancing self-efficacy, and integration to accommodate the multi-morbidity with which older adults typically present) |

| Klaver et al. (2021) [38] | mHealth | 65+ | Quantitative | TAM, UTAUT, privacy risk, performance risk, legal concern, trust, intention to use |

| Liu et al. (2021) [115] | Social robots | 60+ | Quantitative | Perceived competence and perceived warmth |

| Wilkowska et al. (2021) [72] | Assistive technology | 60+ | Quantitative | Age (60–69 years vs. 70+ years), health status (healthy vs. chronic illness), gender (male vs. female), acceptance of health-supporting technologies |

| Wang et al. (2021) [74] | Aged-care products | 55+ | Quantitative | ISS model, attachment theory, perceived information quality, perceived system quality, perceived service quality, self-perception of ageing, self-perception of ageing, emotional attachment, willingness to use |

| Johnson et al. (2021) [116] | mHealth | 65+ | Qualitative | Previous experience, care environment, personal values, knowledge, support systems, app usability, life stage, and friend or family history |

| Talukder et al. (2021) [59] | Wearable Health Technologies (WHTs) | 65+ | Quantitative | Theory of consumption values, enabler-inhibitor perspective, functional value (including device quality and convenience value. social value. epistemic value. emotional value, continued use intention |

| Cross et al. (2021) [117] | Patient portals electronic health record (EHR) | 65+ | Quantitative | TAM, expectation-confirmation theory, level of patient portal use (none, moderate, extensive, self-rated health care quality) |

| Ghorayeb et al. (2021) [42] | Smart home | 65+ | Qualitative | Older people’s views and expectations |

| Ali et al. (2021) [58] | eHealth | 65+ | Quantitative | Age, gender, education level, employment status, household income, health status, disability severity, ICT access, eHealth use |

| Shareef et al. (2021) [41] | Autonomous homecare system | —— | Quantitative | Autonomous trust model (ATM), technological uncertainty and Reliability, self-Concept and behavioral attitude, personal benefit and accomplishment, personal ability and control, empathetic cooperation and social interaction, trust, behavioral intention |

| Huang et al. (2022) [73] | Smart senior care | 60+ | Quantitative | Age, number of children, frequency of children visiting parents, perceived adequacy of senior care received, self-reported health, chronic diseases, smartphone use, attitude towards smart senior care, willingness of older adults to choose smart senior care |

| Rój (2022) [82] | eHealth | 60+ | Quantitative | UTAUT, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, acceptance and use of eHealth |

| Zhou et al. (2022) [118] | Wisdom healthcare | —— | Mixed-method | Knowledge gap theory, digital divide (including digital access gap, digital use gap, and digital knowledge gap), AI and big data, value perception, satisfaction with wisdom healthcare services |

| van Elburg et al. (2022) [63] | mHealth | 65+ | Quantitative | TAM, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude toward use, sense of control, personal innovativeness, self-perceived effectiveness, service availability, facilitating circumstances, gender, intention to use |

| Camp et al. (2022) [91] | In-home monitoring technology | 55+ | Qualitative | Older adults’ perceptions (personal hygiene, feeding, and socializing) |

| Jeng et al. (2022) [68] | Smart health wearable devices | 60+ | Quantitative | TAM, technology readiness, technology interactivity, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, technology anxiety, attitude, intention to use |

| Alam and Khanam (2022) [69] | mHealth | 46+ | Quantitative | TAM, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived reliability, price value, technology anxiety, behavioral intention, actual usage behavior |

| Ma and Zuo (2022) [75] | OHCs | 50+ | Quantitative | Dual-process model, direct informational support, indirect informational support, direct emotional support, indirect emotional support, habit, continued participation |

| Rodríguez-Fernández et al. (2022) [119] | Telemedicine | 65+ | Quantitative | TAM, UTAUT, chronic conditions (e.g., cancer, hypertension, diabetes), mood disorders (depression and anxiety), age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, marital status, telemedicine readiness |

| Pirzada et al. (2022) [120] | Smart homes | —— | Literature review | Four key criteria of smart elderly care (be personalized toward their needs, protect their dignity and independence, provide user control, and not be isolating) |

| Wang et al. (2023) [76] | Internet + traditional Chinese medicine | 60+ | Mixed-method | Attitude, knowledge cognition, and digital literacy, demand for TCM nursing services |

| Choi et al. (2023) [121] | Smart silver care | 65+ | Quantitative | ADDIE model, emotional support, cognition, physical activity, health data, nutrition, and motivation |

| Tandon et al. (2024) [71] | mHealth | 60+ | Quantitative | Self-determination theory, gamification, usability (including error prevention, completeness, memorability, learnability, and customization), empathetic cooperation and social interaction, engagement, continued use intention |

| Ren and Zhou (2023) [64] | Virtual nursing home | 60+ | Quantitative | UTAUT, TAM, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, conformist mentality, attitude, behavioral intention |

| He et al. (2023) [95] | SARs | 60+ | Quantitative | TAM, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived enjoyment, whether to use mobile devices, attitude, intention to use |

| van Elburg et al. (2023) [65] | mHealth | 65+ | Quantitative | TAM, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude toward use, subjective norm, sense of control, feelings of anxiety, personal innovativeness, social relationships, self-perceived effectiveness, service availability, facilitating circumstances, intention to use |

| Shareef et al. (2023) [85] | Machine autonomy | 65+ | Quantitative | ATM, expected personal ability and control, expected technological uncertainty, family benefit and accomplishment, expected empathetic cooperation and social interaction, self-concept and personality & image, trust, behavioral intention |

| Wang et al. (2023) [83] | Smart aged-care products | 60+ | Quantitative | UTAUT, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, perceived cost, perceived risk, behavioral intention, use behavior |

| Berridge et al. (2023) [77] | AI companion robots | —— | Quantitative | Age, education level, history of memory problems, number of chronic conditions, computer use confidence, social activity level, perceptions |

| Wang et al. (2023) [122] | mHealth | 60+ | Quantitative | TAM, Protection motivation theory (PMT), Perceived risk theory, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived risk, attitude, behavioral intention |

| Frishammar et al. (2023) [92] | Digital healthcare platforms (DHPs) | 65+ | Qualitative | UTAUT2, negative attitudes, technology anxiety, lack of trust |

| Cao et al. (2023) [123] | Smart medical and elderly care systems (SMECS) | 50+ | Quantitative | Stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R), price, operability, personalisation, perceived risk, perceived value, continuous participation |

| Koo et al. (2023) [124] | mHealth | 60+ | Quantitative | UTAUT, performance expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, device trust, chronic disease (Y/N), performance expectancy, behavioral intention |

| Yang et al. (2023) [79] | Digital health Technologies | 50+ | Quantitative | Age, gender, education level, marital status, employment status, exercise, medical insurance, income, life satisfaction, history of illness, willingness to use and willingness to pay |

| Zafrani et al. (2023) [80] | SARs named Gymmy | 65+ | Quantitative | Trust (including trust in the robot’s functional capabilities and social aspects) and technophobia (including personal failure, human vs. machine ambiguity, and inconvenience), quality evaluation (including pragmatic quality, hedonic quality, and attractiveness) |

| Chiu et al. (2023) [87] | VR | 65+ | Quantitative | VR training intervention |

| Frishammar et al. (2023) [78] | DHPs | 60+ | Mixed-method | TAM, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, digital maturity, trust, usage behavior |

| Afifi et al. (2023) [94] | VR | 54+ | Quantitative | VR improvements (older adults’ affect and stress, relationship with their family member, and overall quality of life) |

| Sancho-Esper et al. (2023) [125] | VR | 70+ | Mixed-method | TAM, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, technology anxiety, attitude, intention to use, intention to recommend |

| Sun et al. (2023) [126] | Mobile health services (MHS) | 60+ | Quantitative | PMT, S-O-R, fear appeal, coping appeal, fear Arousal, perceived usefulness, adoption intention |

| Li et al. (2024) [81] | Smart health services | 60+ | Quantitative | TAM, technical trust, security trust, privacy trust, family support, community support, service support. perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, health expectations, attitude, intention to use |

| Chen et al. (2024) [2] | Smart elderly care | 60+ | Quantitative | Social Support theory, smart elderly care, social support, quality of life |

| Leung et al. (2024) [84] | mHealth | 60+ | Mixed-method | IRT, medical management task support, dietary task support, and exercise task support, perceived usefulness and technology anxiety, adoption intention |

| Zhang et al. (2024) [93] | Cameras | 55+ | Mixed-method | Older adults’ privacy concerns (data privacy, ageing, and their ability to use digital technology) |

Note. AI = Artificial Intelligence; ATM = Autonomous Trust Model; DHPs = Digital Healthcare Platforms; EHR = Electronic Health Record; HBM = Health Belief Model; ICT = Information and Communication Technology; IRT = Innovation Resistance Theory; ISS model/IS success model = Information Systems Success Model; mHealth = mobile health; OHCs = Online Health Communities; PMT = Protection Motivation Theory; SARs = socially assistive robots; SMECS = Smart Medical and Elderly Care Systems; S–O–R = Stimulus–Organism–Response; TAM = Technology Acceptance Model; TCM = Traditional Chinese Medicine; UTAUT = Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology; UTAUT2 = Extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology; VR = Virtual Reality; WHTs = Wearable Health Technologies.

References

- World-Health-Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Chen, X.; Wu, M.L.; Wang, D.B.; Zhang, J.; Qu, B.; Zhu, Y.X. Association of smart elderly care and quality of life among older adults: The mediating role of social support. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Xie, C.; Schenkel, J.A.; Wu, C.; Long, Q.; Cui, H.; Aman, Y.; Frank, J.; Liao, J.; Zou, H.; et al. A research agenda for ageing in China in the 21st century (2nd edition): Focusing on basic and translational research, long-term care, policy and social networks. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 64, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Liu, H. The Impact Mechanism of Government Regulation on the Operation of Smart Health Senior Care Service Platform: A Perspective from Evolutionary Game Theory. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2025, 14, 8646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verified-Market-Reports. Smart Elderly Care System Market Insights; Verified Market Reports: Pune, India, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rybenská, K.; Knapová, L.; Janiš, K.; Kühnová, J.; Cimler, R.; Elavsky, S. SMART technologies in older adult care: A scoping review and guide for caregivers. J. Enabling Technol. 2024, 18, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, L.; Mulcahy, R.; Letheren, K.; Kietzmann, J.; Russell-Bennett, R. Mapping the deepfake landscape for innovation: A multidisciplinary systematic review and future research agenda. Technovation 2023, 125, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.W.T.; Zhang, R. Trust in AI chatbots: A systematic review. Telemat. Inform. 2025, 97, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Hagedorn, A.; An, N. The development of smart eldercare in China. Lancet Reg. Health-West. Pac. 2023, 35, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachouie, R.; Sedighadeli, S.; Khosla, R.; Chu, M.-T. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: A mixed-method systematic literature review. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2014, 30, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.H.; Shi, K.Y.; Yang, C.Y.; Niu, Y.P.; Zeng, Y.C.; Zhang, N.; Liu, T.; Chu, C.H. Ethical issues of smart home-based elderly care: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 3686–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Shukor, N.S.A.; Ishak, I.S. Systematic literature review of healthcare services for the elderly: Trends, challenges, and application scenarios. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 12, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhang, W. Research Progress in Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Smart Elderly Care Service Design: A Bibliometric Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA), Xi’an, China, 28–30 March 2025; pp. 1280–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.; Heinsch, M.; Betts, D.; Booth, D.; Kay-Lambkin, F. Barriers and facilitators to the use of e-health by older adults: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Chau, K.Y.; Liu, X.X.; Wan, Y. The progress of smart elderly care research: A scientometric analysis based on CNKI and WOS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randhawa, K.; Wilden, R.; Hohberger, J. A bibliometric review of open innovation: Setting a research agenda. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 750–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, O.; Wallin, J.A. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics 2015, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United-Nations. World Population Ageing 2023: Challenges and Opportunities of Population Ageing in the Least Developed Countries; United Nations: New York City, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tajudeen, F.; Bahar, N.; Pin, T.; Saedon, N. Mobile technologies and healthy ageing: A bibliometric analysis on publication trends and knowledge structure of mHealth research for older adults. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Christofi, M. R&D internationalization and innovation: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; Grp, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ngai, E.; Wang, L. Resistance to artificial intelligence in health care: Literature review, conceptual framework, and research agenda. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzo-Barker, J.; Chow-White, P.A.; Adams, P.R.; Mentanko, J.; Ha, D.; Green, S. Blockchain as a disruptive technology for business: A systematic review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Bote, V.P.; Moya-Anegón, F. A further step forward in measuring journals’ scientific prestige: The SJR2 indicator. J. Informetr. 2012, 6, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, H. Emerging market MNEs: Qualitative review and theoretical directions. J. Int. Manag. 2016, 22, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Lim, W.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ibekwe-SanJuan, F.; Hou, J. The Structure and Dynamics of Cocitation Clusters: A Multiple-Perspective Cocitation Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1386–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabe, M.; Pillinger, T.; Kaiser, S.; Chen, C.; Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Leucht, S.; Correll, C.; Solmi, M. Half a century of research on antipsychotics and schizophrenia: A scientometric study of hotspots, nodes, bursts, and trends. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 136, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace: A Practical Guide for Mapping Scientific Literature; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Humphreys, M. Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behav. Res. Methods 2006, 38, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indulska, M.; Hovorka, D.; Recker, J. Quantitative approaches to content analysis: Identifying conceptual drift across publication outlets. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, T.S.; Ding, A.; Back, K.-J. A bibliometric analysis of the hospitality and tourism environmental, social, and governance (ESG) literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, R.; Sorwar, G. Understanding factors influencing the adoption of mHealth by the elderly: An extension of the UTAUT model. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2017, 101, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaver, N.; van de Klundert, J.; van den Broek, R.; Askari, M. Relationship between perceived risks of using mHealth applications and the intention to use them among older adults in the Netherlands: Cross-sectional study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e26845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajita, M.; Hodgson, N.; Lam, K.; Yoo, S.; Han, H. Facilitators of and barriers to mHealth adoption in older adults with heart failure. CIN-Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2018, 36, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ni, Q.; Zhou, R. What factors influence the mobile health service adoption? A meta-analysis and the moderating role of age. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, M.A.; Kumar, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kumar, U.; Akram, M.S.; Raman, R. A new health care system enabled by machine intelligence: Elderly people’s trust or losing self control. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorayeb, A.; Comber, R.; Gooberman-Hill, R. Older adults’ perspectives of smart home technology: Are we developing the technology that older people want? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2021, 147, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-H.; Lin, W.-Y.; Chang, Y.-S.; Chang, P.-C.; Lee, M.-Y. Technology anxiety and resistance to change behavioral study of a wearable cardiac warming system using an extended TAM for older adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S.; Agahari, W.; Keijzer-Broers, W.; de Reuver, M. Digital healthcare technology adoption by elderly people: A capability approach model. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 53, 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspur-Behbahani, S.; Monaghesh, E.; Hajizadeh, A.; Fehresti, S. Application of mobile health to support the elderly during the covid-19 outbreak: A systematic review. Health Policy Technol. 2022, 11, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudier, P.; Kondrateva, G.; Ammi, C.; Chang, V.; Schiavone, F. Patients’ perceptions of teleconsultation during COVID-19: A cross-national study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Luo, M.; Nie, R.; Zhang, Y. Technical attributes, health attribute, consumer attributes and their roles in adoption intention of healthcare wearable technology. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2017, 108, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavandi, H.; Jaana, M. Factors that affect health information technology adoption by seniors: A systematic review. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1827–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, P.-L.; Lim, W.M.; Ahmed, P.K.; Chan, A.H.; Loo, J.M.; Cheong, S.-N.; Yap, W.-J. Does power posing affect gerontechnology adoption among older adults? Behav. Inf. Technol. 2017, 36, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthanat, S.; Wilcox, J.; Macuch, M. Profiles and predictors of smart home technology adoption by older adults. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2019, 39, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pywell, J.; Vijaykumar, S.; Dodd, A.; Coventry, L. Barriers to older adults’ uptake of mobile-based mental health interventions. Digit. Health 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Demiris, G.; Thompson, H.J.; Chen, K.Y.; Burr, R.; Patel, S.; Fogarty, J. Feasibility testing of a home-based sensor system to monitor mobility and daily activities in korean american older adults. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2017, 12, e12127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell, A.J.; McGrath, C.; Dove, E. ‘That’s for old so and so’s!’: Does identity influence older adults’ technology adoption decisions? Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 1550–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajita, M.I.; Hodgson, N.A.; Budhathoki, C.; Han, H.-R. Intention to use mHealth in older adults with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 32, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.A.; Alam, K.; Taylor, B.; Ashraf, M. Examining the determinants of eHealth usage among elderly people with disability: The moderating role of behavioural aspects. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2021, 149, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]