Abstract

The ocean is a priority for governments and international organizations. Large-scale, in situ ocean water quality monitoring programs are not very feasible due to the high costs associated with their implementation and operation. In this work, we present a tool for assessing ocean conditions, the SIMAR Integrated Marine Water Quality Index (ICAM-SIMAR-Integral), composed of two satellite parameters and three numerical models. We evaluated its spatiotemporal variability at 10 sites in the Gulf of Mexico, which have dissimilar environmental conditions. We validated its use by comparing it with the TRIX trophic index at 41 sites. To construct the index, the five parameters were standardized using a logarithmic equation and then summed, weighted according to their relationship with eutrophication. An index with a scale of 1 to 100 was obtained, divided into five classification intervals: oligotrophic, mesotrophic, eutrophic, supertrophic, and hypertrophic. The median values of the index and its parameters exhibited significant spatial and temporal variability, consistent with the literature’s criteria regarding their values and eutrophication thresholds. Comparison with TRIX showed no significant differences, validating the implementation of ICAM-SIMAR-Integral as an easily interpreted early warning system for managers and decision-makers in conservation matters. This index will allow for continuous, large-scale monitoring of the ocean, thereby contributing synoptically to its sustainable use.

1. Introduction

The oceans are a vital support system for human life on the planet, fulfilling many societal needs through ecosystem services. However, the irresponsible use of marine resources has led to alarming levels of degradation [1]. Decades of exploitation have increased marine pollution [2], declined fish populations and collapsed fisheries [3], destroyed habitats and resulted in biodiversity loss [4], and had significant impacts on food systems [5]. This adverse situation is currently being exacerbated by population growth, industrialization, urbanization, and tourism, increasing wastewater discharge in coastal areas and generating environmental, sociological, and economic risks in many parts of the world [1,6,7].

Water has been classified as a direct ecosystem service, and its sustainable management is a priority on the agendas of several governments and international organizations, with the issue of assessing its quality being a recurring theme [8]. In marine environments, water quality refers to the set of physical, chemical, and biological conditions that allow for the healthy functioning of oceanic and coastal ecosystems, as well as the maintenance of biodiversity, primary productivity, and ecosystem services [9]. Water quality is a descriptive parameter of the aquatic environment, both from an environmental perspective and from a planning and management perspective. Water quality can be affected by natural causes or external factors; when these latter factors are not related to the hydrological cycle, it is pollution [10].

The largest percentage of marine pollution originates on land, either along the coast or inland. Pollutants, such as chemicals and nutrients, are transported from farms, factories, and cities by rivers to bays and estuaries, and then to the ocean [11]. Marine debris, such as plastic, is transported by wind or stormwater runoff [12]. Due to the increase in nutrients, ecosystems undergo eutrophication processes. Eutrophication is an ecological process that occurs when an aquatic ecosystem receives an excess of nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, from either natural or anthropogenic sources, such as agricultural fertilizers and contaminated urban and industrial wastewater [13].

One of the challenges faced by scientists studying water quality is how to transform data of diverse natures and varying levels of variability into information that is understandable and usable by the broader community. For that, several approaches in the form of indices have been developed to integrate these datasets. According to Gupta et al. [14], the objective of an index is to express, through a number, the relative magnitude of a phenomenon or condition, so that it can be used as an assessment and management tool.

Several indices have been developed to assess water quality, including the Trophic Index or TRIX [15] and various versions of Water Quality Indices or WQIs [13]. The main objective of these indices is to evaluate the condition of water used for human consumption as a direct ecosystem service. They are based on monitoring systems for physical, chemical, and/or biological variables, the values of which determine the direct human use of water or assess the cost involved in bringing it to an acceptable level. Much has been published on the use of these indices worldwide; however, most have been used to assess freshwater, inland waters, and, to a lesser extent, coastal waters [13,16].

Unlike inland water monitoring programs, the comprehensive implementation of an in situ monitoring program in large marine ecosystems is practically impossible due to the high costs involved. Consequently, a proposal has emerged to provide a water quality index approach that utilizes data derived from satellite observations, as well as data derived from marine environmental models. Remote sensing is an effective tool for measuring environmental variables over large areas at a lower cost, filling the gaps left by the instrumental limitations of traditional methodologies and generating the large amount of data needed to build predictive models useful for management [17,18,19]. Daily satellite observations allow for the monitoring of the surface marine environment and the generation of time series of key variables to assess marine water quality.

This work aims to leverage the ability to access databases of variables related to eutrophication processes, derived from remote sensing observations and numerical models, to develop a quality index that allows for a synoptic assessment of marine water quality across a broad spatial scale and daily. This tool could reveal both the spatial and temporal variability of marine water quality and would be publicly available on the Marine and Coastal Information and Analysis System operational explorer (SIMAR). The goal is to obtain an index that allows for the long-term sustainability of a quick and fairly reliable assessment of the condition of the sea in relation to eutrophication processes.

In accordance with these considerations, the objectives of this work are: I. To describe the SIMAR Integral Marine Water Quality Index (ICAM-SIMAR-Integral), based on five parameters obtained from data derived from remote sensing and numerical models; II. To evaluate the spatio-temporal variability of the index and the parameters that compose it, in ten sites in the Gulf of Mexico that represent different environmental conditions; III. To validate the results of the index by comparing them with results obtained in situ using the TRIX eutrophication index, collected from specialized literature.

The following section describes the four steps involved in creating the index, including generating sub-indices for each parameter and then calculating their weighted sum. The spatial and temporal variability of the index across a region will also be shown, and finally, the tests performed during the product validation process will be analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the SIMAR Integral Marine Water Quality Index (ICAM-SIMAR-Integral)

The SIMAR Integral Marine Water Quality Index (ICAM-SIMAR-Integral) is an adapted version of Horton’s [20] “WQI”. It is designed to assess marine eutrophication as an early warning system using five environmental parameters, satellite data, and numerical models. Based on the general criteria applied to the different existing WQI variants [16], the following four steps were carried out for its development:

- Selection of environmental parameters for marine water quality

Five parameters available on the SIMAR operational explorer were selected, obtained from Marine Water Quality Early Warning System—1 km (SATwality) [21], through satellite observation and the application of numerical models, covering a spatial resolution of 1 km and a daily temporal resolution of each pixel:

- -

- Chlorophyll-a concentration (mg/m3) or CHL: Satellite biological parameter, indicator of the presence of phytoplankton on the sea surface and related to possible contamination by organic matter, available since 4 September 1997 [22].

- -

- Nitrate concentration (mmol m−3) or NO3: Chemical parameter obtained from numerical models, an indicator of the presence of nutrients at the sea surface, available since 1 January 1993 [23].

- -

- Phosphate concentration (mmol m−3) or PO4: Chemical parameter obtained from numerical models, an indicator of the presence of nutrients at the sea surface, available since 1 January 1993 [24].

- -

- Diffuse attenuation coefficient of incident irradiance at 490 nm (m−1) or KD490: Satellite optical parameter used as an indicator of turbidity, available since 4 September 1997 [25].

- -

- Dissolved oxygen at the sea surface (mmol/m3) or O2: Chemical parameter derived from models, which can be affected by changes in salinity, temperature, or the presence of organic matter, available since 1 January 1993 [26].

Satellite-derived variables and numerical models are generated operationally in SIMAR by resampling the original Copernicus Marine Service datasets at a spatial resolution of 1 km. The CHL and Kd490 products were obtained from the OCEANCOLOUR_GLO_BGC_L4_MY_009_104 [27]. This dataset provides multi-year level 4 biogeochemical fields, with full gaps, derived from satellite observations. The models (NO3, PO4, and O2) are generated using the NEMO-PICIS GLOBAL_ANALYSISFORECAST_BGC_001_028 modeling framework [28]. All products were interpolated to a common grid using a conservative remapping method and consistently masked using the SIMAR land–ocean boundary to ensure spatial comparability across variables. The temporal series was harmonized by constructing a continuous daily dataset that integrates hindcast fields up to their terminal date and operational analyses thereafter. The validation of each dataset follows the protocols established by the Copernicus Marine Service [29,30]. These documents provide comprehensive assessments of model proficiency, bias, uncertainty estimates, and comparisons with in situ measurements from global observation networks.

- B.

- Generation of the sub-indices for each parameter

The concentrations of each parameter were converted into unitless subscripts. Considering the logarithmic behavior of each parameter according to the time series analyzed from the SIMAR database, a base-10 logarithmic standardization was performed with a range between 0 and 1, based on the maximum (max) and minimum (min) values. The logarithmic standardization equations used to obtain each subscript (Sub) were as follows:

- -

- Chlorophyll-a sub-index (CHL):

Nitrate sub-index (NO3):

- -

- Phosphate sub-index (PO4):

- -

- Sub-index of the diffuse attenuation coefficient (KD490):

Dissolved oxygen sub-index (O2):

where x is the daily value of the parameter observed in a pixel of the SIMAR area (covers 1.0° N and 33.0° N latitude, and 123.0° W and 59.0° W longitude; geographic coordinates latitude/longitude on WGS84 (EPSG:4326)). Maximum and minimum values (Table 1) were previously defined through analysis of the SIMAR database (data series period from 1 January 2000, to 31 December 2024) and specialized literature searches [5,31,32,33,34]. If any value of x were above the max or below the min, then x would take the values of these values.

Table 1.

Maximum (max) and minimum (min) values of each satellite parameter or model that make up the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral.

- C.

- Assignment of parameter weighting values

To assign weights to each parameter, their variability was determined at key sites within the SIMAR area using Principal Component Analysis (data series period from 1 January 2000, to 31 December 2024). Based on the results of the empirical orthogonal functions from each analysis, the weighting of each parameter was generalized and performed, resulting in a first version. To further support the previous result, specialized literature on the parameters and their relationship to eutrophication processes was reviewed [5,33,34], and various experts were consulted. Accordingly, the following weights (W) were assigned to the parameters: NO3 = 0.3, CHL = 0.3, KD490 = 0.25, PO4 = 0.1, and O2 = 0.05.

- D.

- Calculation of the SIMAR Integral Marine Water Quality Index (ICAM-SIMAR-Integral) using an aggregation function

The subscripts of the individual parameters were combined using the weights to obtain a single overall index:

In this Equation (6), W represents the weights assigned to each parameter, and the terms Sub(CHL), Sub(NO3), Sub(PO3), Sub(KD490), and Sub(O2) are the standardized values of each parameter derived from Equations (1)–(5). Subsequently, a rating scale was generated to categorize the different levels of marine water quality according to the level of eutrophication related to the overall index value (Table 2). The criteria for defining the different intervals were based on expert judgment and aligned with established scales.

Table 2.

Evaluation criteria of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral based on its quantitative values.

2.2. Evaluation of the Spatial and Temporal Variability of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral

2.2.1. Study Sites

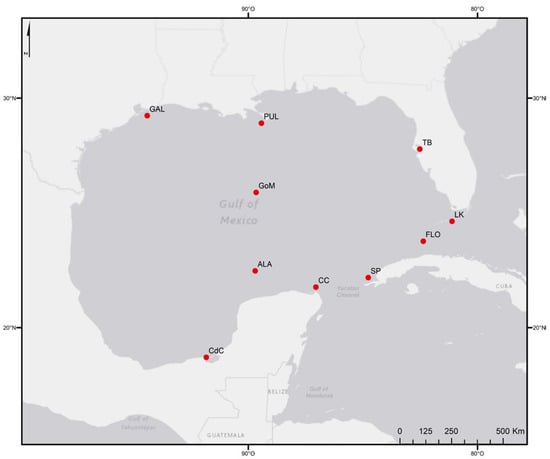

To evaluate the spatiotemporal variability of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral, 10 sites were selected within the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1): four estuaries’ areas with different degrees of eutrophication, one coastal upwelling zone, three coral reef sites, and two open oceanic zones (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Geographic location of the 10 study sites. TB: Southwest Pass, PUL: Pulaski Shoals Light, GAL: Galveston, CdC: Ciudad del Carmen, CC: Cabo Catoche, ALA: Alacranes Reef, SP: Bajos de Sancho Pardo, FLO: Florida Straits, GoM: Mid Gulf, and LK: Long Key.

Table 3.

Study sites, acronyms, coordinates, and the ecosystem they represent.

2.2.2. Data Processing for the Spatio-Temporal Evaluation of the Index

Daily values for the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral index and its constituent parameters (CHL, NO3, PO4, KD490, and O2) were downloaded from the SIMAR operational explorer for each site over an 11-year data series, beginning on 1 January 2014, and ending on 31 December 2024. The median, percentiles (25th–75th), and minimum and maximum values for each metric were calculated for each site and for each site per year and visualized using box and whisker plots.

To evaluate the spatiotemporal variability of each metric, nonparametric statistics based on null models were used [35]. Using the primary data from ICAM-SIMAR-Integral (univariate matrix), a similarity matrix based on Euclidean distances was constructed, and a one-way PERMANOVA was applied by “site” and “year,” with 9999 permutations and a significance level of 0.05. A pairwise test was also performed. With the primary data of the parameters that make up the index (multivariate matrix), a Z-test was first performed (the mean of each parameter was subtracted and the result divided by its standard deviation), yielding a normalized matrix. Subsequently, a similarity matrix was constructed (similar to the one generated for the index), and a one-way PERMANOVA by “site” and a pairwise test were also applied. The PRIMER v7 software [36] was used for all procedures.

2.3. Validation of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral

To validate the proposed index, the results of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral were compared with in situ results obtained from the TRIX eutrophication index [15], based on various data sources from specialized literature (Table 4). A total of seven data sources from 12 coastal locations in Mexico were reviewed, resulting in a sample of 41 sites for comparison. The trophic state index, or TRIX, is a multivariate index that includes chlorophyll, nitrogen components, phosphates, and oxygen (TRIX = ((log [CHL X a D%O X N X P]) − (−1.5))/1.2). According to Penna et al. [37], it is classified into four levels of eutrophication: poorly productive waters (oligotrophic), moderately productive waters (mesotrophic), moderately to highly productive waters (eutrophic), and highly productive waters (the highest trophic level). To align it with our index, the latter criterion was considered supertrophic for this study. To be able to compare both indices, the TRIX in situ (Table 4) was first transformed to the TRIX homologous index using the equation:

TRIX homologous-Index = 100 − (TRIX in situ × 10)

To statistically compare the TRIX homologous-Index with the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral (Table 4), two approaches were used: the goodness-of-fit test [38,39], considering the TRIX homologous-Index as observed data and the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral as modeled data; and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [40,41,42]. For both approaches, the criteria of Perdices [43] were followed with a significance level of 0.05. The critical values for the goodness-of-fit test were taken from Zar [38], and for the Wilcoxon signed-rank test from Wilcoxon et al. [41]. For the goodness-of-fit test, the results were interpreted following the criteria of Xu et al. [39], while for the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the criteria of Rey and Neuhäuser [44] and Maggio and Sawilowsky [45] were followed.

Table 4.

TRIX mean and median values obtained in the field at different coastal sites in Mexico, collected from various information sources. ICAM-SIMAR-Integral mean and median values at the same sites, obtained from daily values collected from the SIMAR operational explorer.

Table 4.

TRIX mean and median values obtained in the field at different coastal sites in Mexico, collected from various information sources. ICAM-SIMAR-Integral mean and median values at the same sites, obtained from daily values collected from the SIMAR operational explorer.

| TRIX | ICAM-SIMAR-Integral | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Site | No. | Period | Mean | Median | Mean | Median |

| Herrera-Silveira and Morales-Ojeda [46] | Celestun | 1 | Three times a year from 2002 to 2006 | - | 4.43 | 53.63 | 54.35 |

| Sisal | 2 | - | 4.61 | 54.48 | 55.76 | ||

| Progreso | 3 | - | 5.17 | 53.64 | 54.93 | ||

| Telchac | 4 | - | 4.47 | 53.91 | 55.30 | ||

| Dzilam de Bravo | 5 | - | 3.57 | 51.55 | 52.37 | ||

| Ría Lagartos | 6 | - | 4.41 | 55.50 | 56.24 | ||

| Aranda-Cirerol [12] | Celestún | 7 | March to May 2000 | 5.23 | - | 58.14 | 57.96 |

| 8 | July to September 2000 | 4.80 | - | 50.80 | 51.07 | ||

| 9 | November 2000 to January 2001 | 5.46 | - | 55.06 | 55.24 | ||

| Sisal | 10 | March to May 2000 | 5.08 | - | 58.52 | 58.22 | |

| 11 | July to September 2000 | 5.10 | - | 49.32 | 49.41 | ||

| 12 | November 2000 to January 2001 | 4.89 | - | 56.95 | 58.58 | ||

| Progreso | 13 | March to May 2000 | 4.79 | - | 57.21 | 56.91 | |

| 14 | July to September 2000 | 5.16 | - | 47.60 | 47.52 | ||

| 15 | November 2000 to January 2001 | 4.99 | - | 56.57 | 57.82 | ||

| Dzilam de Bravo | 16 | March to May 2000 | 5.20 | - | 55.36 | 55.88 | |

| 17 | July to September 2000 | 5.17 | - | 46.37 | 46.38 | ||

| 18 | November 2000 to January 2001 | 4.78 | - | 55.51 | 55.45 | ||

| Ayala-Rodríguez [47] | Santa María | 19 | Monthly monitoring from November 2004 to February 2006 | 6.68 | - | 29.10 | 28.70 |

| Topolobampo | 20 | 5.99 | - | 37.14 | 35.52 | ||

| Ohuira | 21 | 6.13 | - | 38.75 | 38.25 | ||

| Escobedo-Urias [48] | Topolobampo | 22 | 2004 | 5.74 | - | 38.98 | 37.70 |

| 23 | 2005 | 5.82 | - | 37.44 | 35.79 | ||

| 24 | 2006 | 6.07 | - | 36.06 | 34.95 | ||

| 25 | 2007 | 6.20 | - | 36.20 | 35.42 | ||

| Navachiste-Macapule | 26 | 1998 | 4.95 | - | 41.14 | 40.89 | |

| 27 | 2000 | 5.09 | - | 39.24 | 38.71 | ||

| 28 | 2002 | 5.27 | - | 40.04 | 39.73 | ||

| 29 | 2003 | 5.43 | - | 40.46 | 40.15 | ||

| Cacheux [49] | Guaymas | 30 | September 2018 | 4.50 | - | 44.36 | 42.61 |

| 31 | December 2018 | 4.50 | - | 43.21 | 44.24 | ||

| 32 | February 2019 | 6.00 | - | 37.88 | 37.74 | ||

| 33 | April 2019 | 4.50 | - | 37.09 | 37.39 | ||

| Cervantes-Duarte et al. [50] | Bahía de Magdalena | 34 | 2015 | - | 5.38 | 52.68 | 53.94 |

| 35 | 2016 | - | 5.61 | 50.47 | 52.54 | ||

| 36 | 2017 | - | 5.85 | 45.86 | 46.73 | ||

| 37 | 2018 | - | 5.91 | 47.82 | 49.13 | ||

| Reyes-Velarde et al. [51] | Santa María-La Reforma | 38 | September 2018 | 4.39 | 4.88 | 44.30 | 46.10 |

| 39 | December 2018 | 4.48 | 5.21 | 32.30 | 34.51 | ||

| 40 | February 2019 | 6.31 | 6.38 | 27.84 | 28.34 | ||

| 41 | April 2019 | 4.61 | 4.70 | 50.80 | 51.22 | ||

3. Results and Discussion

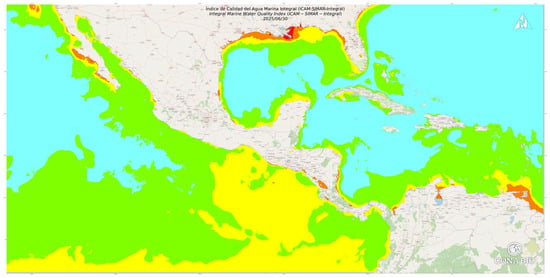

3.1. Visualization of ICAM-SIMAR-Integral on the SIMAR Operational Explorer

The ICAM-SIMAR-Integral is available and operational in SATwality, on the SIMAR operational explorer [21], displaying daily information for each 1 km pixel, from 1 January 1998, to the present day, covering 25,678,682 pixels in the SIMAR area and 1,553,287 pixels for the Gulf of Mexico. This index is part of an early warning system that detects potential impacts on water quality at specific locations, based on significant changes in the values of one or more of its constituent parameters.

This document shows an example of the differential visualization of the index, where the evaluative criteria for the level of eutrophication are represented by the different colors described previously. Figure 2 illustrates the data for 30 June 2025, where blue pixels indicate oligotrophic waters, primarily coinciding with open ocean waters. As we approach the coast, green pixels appear, indicating mesotrophic conditions, coinciding with many coral reef areas and other zones with moderate eutrophication. Similarly, as we approach rivers, estuaries, or other sources of larger terrestrial runoff or upwelling zones, the pixels change from yellow to red, reflecting the increasing eutrophication. By visiting the SIMAR operational explorer, you can observe the spatial and temporal variability of the index results within its historical time series.

Figure 2.

Image of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral result from 30 June 2025, obtained from the SIMAR operational explorer.

However, a methodological limitation related to spatial scale must be acknowledged. Since the algorithm is based on input data derived from satellites and models with a specific pixel resolution, very localized phenomena occurring at a spatial scale below this threshold (1 km) are beyond the system’s detection capacity.

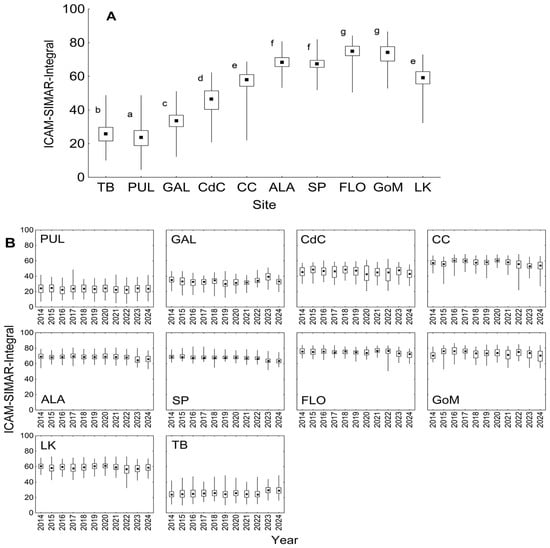

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variability of Metrics

The ICAM-SIMAR-Integral showed significant differences between sites (Pseudo-F = 1232.3, p = 0.001). The statistical analysis reflects a gradient of spatial variability, with the highest median values (above 70) in open oceanic sites, values between 60 and 70 for coral reef sites in Cuba and Mexico, below 60 for coastal areas in Mexico and the Long Key coral reefs, and the lowest values (below 40) for estuarine sites in the United States (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Spatial and temporal variability (black squares as median, white rectangles as percentiles 25–75, vertical lines as minimum, and maximum) of the SIMAR Integral Marine Water Quality Index (ICAM-SIMAR-Integral). (A) Variability between sites, where the lowercase letters (a–f) represent the result of the pairwise test analysis; (B) Variability between years at each site. The full names of the sites can be found in Table 3.

Pulaski Shoals Light, Southwest Pass, and Galveston are located near coastal areas with high eutrophication, such as the mouth of the Mississippi River and Tampa and Galveston Bays. All three zones receive high levels of terrigenous runoff from urban sources, including cities and ports, as well as agricultural and industrial sources. They also receive nitrogen deposition from the atmosphere (due to industrial emissions) as it falls into the sea with rainfall. This situation results in nutrient-rich coastal waters, with high turbidity and abundant phytoplankton [52,53].

The coastal areas of Mexico (Ciudad del Carmen and Cabo Catoche) appear comparatively less eutrophic than the three sites described above. Laguna de Términos receives runoff from the Usumacinta and Grijalva rivers, which form one of the largest hydrological basins in Mexico, carrying volumes of freshwater laden with nutrients from agriculture, livestock, and wastewater [54,55,56]. Many scientific studies classify this eutrophication as “moderate” compared to highly degraded systems, but with a trend toward deterioration due to increasing anthropogenic pressures [57]. Cabo Catoche is an area vulnerable to nutrient pollution, but it does not exhibit the widespread eutrophication seen in estuarine lagoons. Instead, in addition to seasonal coastal upwellings, it shows “hot spots” of localized eutrophication, directly linked to groundwater discharges [58].

When analyzing index values in reef ecosystems, a steady increase in the nitrogen-phosphorus ratio in coastal waters has been reported in Long Key, resulting from wastewater and fertilizer runoff from urban development in the Florida Keys, in addition to the natural ocean upwelling that also influences it [59]. This sets it apart somewhat in terms of the index from the Sancho Pardo and Alacranes reefs, both sites located far from the mainland and with greater oceanic influence [60,61], and even more so from the open waters of the Florida Straits and the Gulf of Mexico. In the Gulf of Mexico, eutrophication processes are different and more seasonal, not directly influenced by local sources, but rather by massive inputs of nutrients that travel hundreds of kilometers from the continent [62].

Regarding temporal variability, all sites except Pulaski Shoals Light showed significant differences between years (Supplementary Materials Table S1). However, despite this statistical variability, no clear trend is observed in the temporal behavior of the index, nor does any particular year stand out as being visually very different from the others (Figure 3B). This could be because the differences in values were daily or monthly, and this is not as noticeable in the annual graph. Temporal variability can be due to both anthropogenic changes (productive variability in agriculture, industries, coastal developments, among others) and natural changes [63,64]. These latter factors could be related to the inconsistent dry and rainy seasons from year to year, which influence the magnitude of terrestrial runoff [65], and to interannual phenomena such as El Niño and La Niña, which alter climatic patterns every 2 to 7 years [66]. They are also related to the occurrence of meteorological phenomena such as hurricanes [67], coastal upwellings [68], and phytoplankton blooms [69], among others.

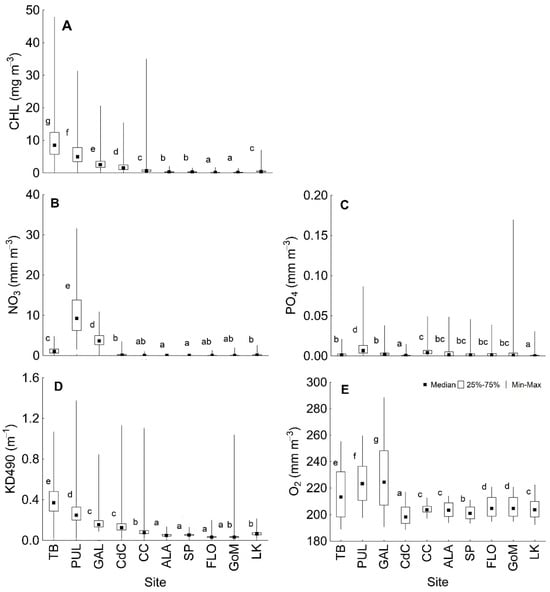

The parameters comprising the marine water quality index showed significant differences between sites (CHL: Pseudo-F = 44.42, p = 0.001; NO3: Pseudo-F = 103.02, p = 0.001; PO4: Pseudo-F = 40.72, p = 0.001; KD490: Pseudo-F = 53.55, p = 0.001; O2: Pseudo-F = 112.92, p = 0.001). CHL and KD490 exhibited a behavior quite like that observed with the index. Their medians exceeded 7 mg m−3 and 0.38 m−1, respectively, in Southwest Pass, and the median NO3 reached almost 10 mm m−3 in Pulaski Shoals Light. Regarding O2, Galveston and Pulaski Shoals Light reached the highest values. PO4 values were relatively similar at all sites, not exceeding 0.2 mm m−3 (Figure 4A–E). These parameters also showed significant differences across the years at each site (Supplementary Materials Table S2). As observed with the water quality index, although statistically significant differences were present, there was no clear trend to explain them, nor were there any years that visually differed considerably from one another at each site. The temporal variability of the parameters is due to the similar causes discussed for the index.

Figure 4.

Spatial variability (black squares as median, white rectangles as percentiles 25–75, vertical lines as minimum, and maximum) of the parameters that make up the marine water quality index. (A) Chlorophyll-a (CHL), (B) Nitrate (NO3), (C). Phosphate (PO4), (D) Diffuse attenuation coefficient (KD490), and (E) Oxygen (O2). The letters represent the results of the pairwise test analysis. The full site names can be found in Table 3.

The spatial variability of the parameters that make up the index is consistent with what has been reported in the literature. The Mississippi River drains approximately 40% of the agricultural runoff in the United States, including much of the world’s most productive land, known as the Corn Belt. Seventy percent of the nitrogen comes from synthetic fertilizers and manure applied to corn and soybean crops, and spring rains carry this nutrient (especially nitrate) into streams and rivers that eventually flow into the Mississippi [70,71]. The Mississippi’s nitrate influence also reaches Galveston, in addition to runoff from the Trinity River originating from agricultural lands that contribute fertilizers [72]. Southwest Pass (Tampa), in turn, is characterized more by phytoplankton blooms, whether of Karenia brevis, cyanobacteria, or diatoms [73], hence its higher median chlorophyll levels. Phytoplankton blooms are a natural phenomenon in this area of the Gulf of Mexico, and the excess nutrients in the bay intensify and prolong them [74].

Regarding O2, the observed results somewhat contradict the literature, since the northern Gulf of Mexico is where “dead zones” or hypoxic areas are most frequently reported, occurring seasonally as a result of eutrophication [75]. Generally, nutrients trigger massive algal blooms in the well-oxygenated surface layer, and when these algae die, they sink and decompose in the lower layer. The bacteria that decompose them consume the dissolved oxygen and create the dead zone [76]. In this case, the contradiction arises because the O2 parameter used in the index is a model that estimates its concentration in the surface layer of the sea and not at greater depths. This model is more responsive to salinity and temperature, and in both Pulaski Shoals and Galveston, the average surface waters are colder and more brackish (due to freshwater runoff from the land) than in other locations, achieving the highest oxygen saturations [77].

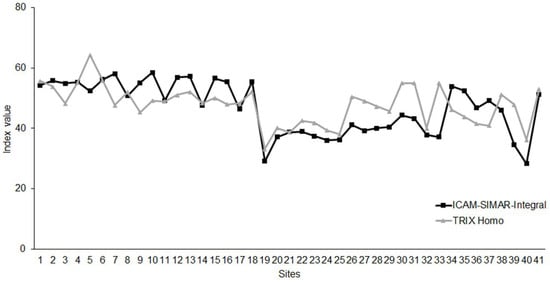

3.3. Validation of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral

Because TRIX scores range from 1 to 10, with the lowest scores representing the best conditions, and considering that ICAM-SIMAR-Integral scores range from 0 to 100, with the highest scores representing the best conditions, a transformation of TRIX to the TRIX homologous-Index was proposed by inverting and modifying the values. The resulting data showed similar behavior for both indices (Figure 5). In the goodness-of-fit test, a calculated value of 47.44 was found, and the critical value derived from the tables was = 55.76. This indicates that, with 95% confidence, the TRIX homologous-Index values are a good fit for ICAM-SIMAR-Integral. Similarly, the calculated value for the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was T = 365, while the critical value was Tlow = 303. This implies that at a 95% confidence level, the TRIX homologous-Index values are equal to those derived from the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral.

Figure 5.

Visual representation of average values of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral and the TRIX homologated in 41 coastal sites of the Mexican territory.

To understand and validate comparison processes between different types of data (in situ and satellite), several considerations must be made, which can focus on the variability patterns of said data, the test statistics and/or association indices used to express these types of relationships, and the number of observations (data pairs) when applying this approach [78]. The results obtained in this study indicate considerable similarity in the classification criteria of both indices regarding the degree of eutrophication at each site, despite the difficulties encountered in this type of comparison. First, it is important to consider spatial scales. TRIX in situ measurements are based on taking a sample of approximately 1 L of seawater, while ICAM-SIMAR-Integral estimates are obtained using remote sensors and models that cover an area on the order of 1 km2.

On the other hand, the frequency of the data within the same comparison period differed. In the case of TRIX, which are average values taken from different scientific articles, this average corresponded to different time periods (months/years). However, the data sample used to calculate the average within the defined period was not daily (for example, in some cases, data were only recorded three times a year). In contrast, in the case of ICAM-SIMAR-Integral, the period described for TRIX coincided with the period described, but the data sample used to calculate the average within the period was always daily. Therefore, the calculation of the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral average always had a larger number of daily data points.

Finally, both indices can exhibit different biases when estimating values. In TRIX, we can find very common biases such as incorrect calibration of the measuring equipment and sample contamination during collection, transport, or storage [79,80]. ICAM-SIMAR-Integral carries with it the potential bias of remote sensors when estimating data, such as cloud cover, reflection from the sea surface, and atmospheric absorption or scattering, among others [81,82]. These conditions make the results of the comparison between the two indices not exact; even so, with these possible problems in the generation of data, the comparative results were satisfactory, and we can consider the ICAM-SIMAR-Integral validated with this analysis.

4. Conclusions

The ICAM-SIMAR-Integral index is derived from a simple and effective analysis that will generate easily interpretable results for protected area managers, decision-makers, and policymakers responsible for conservation actions. The ICAM-SIMAR-Integral will provide a daily value for each 1 km2 plot within the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, and the Northeast Pacific, representing marine water condition based on calculated sub-indices of five parameters related to eutrophication. Daily monitoring of the index will allow for the observation of changes in each marine water plot, generating early warnings of potential water quality deterioration.

The ICAM-SIMAR-Integral is an approximation tool that serves as an early warning system. It is based on a numerical index with qualitative interpretation, designed to assess marine eutrophication through the comprehensive analysis of five relevant parameters derived from satellite data and numerical models. It was designed to operate on a broad spatial scale and with daily frequency. We are aware that it may have certain limitations, such as its restriction to surface waters, its dependence on modeled NO3/PO3/O2 values, its sensitivity to the chosen minimum/maximum and weighting values, and its inability to distinguish between natural and anthropogenic eutrophication signals. While it may not provide perfect results, its use would always be worthwhile given the difficulty of obtaining large-scale, high-frequency data from real-world physicochemical monitoring.

This work offers a novel approach to classifying marine water quality, specifically in locations lacking sustained monitoring programs, making this approach a valuable tool for future synoptic studies of large marine ecosystems that contribute to the sustainability of management plans and the use of ocean ecosystem services. The study showed a wide spatiotemporal variability in the index and its component parameters, successfully differentiating water quality between sites with different marine ecosystems and environmental conditions due to the influence of various eutrophication factors. The ICAM-SIMAR-Integral was successfully validated in comparison with TRIX, another eutrophication index recognized by the scientific community and widely used.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411354/s1, Table S1: Results of the Pair Wise Test (site/years). TB: TB: Southwest Pass, PUL: Pulaski Shoals Light, GAL: Galveston, CDC: Ciudad del Carmen, CC: Cabo Catoche, ALA: Alacranes Reef, SP: Bajos de Sancho Pardo, FLO: Florida Straits, GoM: Mid Gulf, and LK: Long Key; Table S2: Results of the Pair Wise Test (parameter/years). CHL: chlorophyll, NO3: nitrate, PO4: Phosphate, KD490: diffuse attenuation coefficient, and O2: Oxygen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C.-A., E.S.-d.-Á., S.C.-E., R.M.-D., L.R.-d.-l.-C. and L.R.-d.-l.-C.; methodology, H.C.-A. and E.S.-d.-Á.; software, J.V.-C. and L.R.-d.-l.-C.; validation, H.C.-A., E.S.-d.-Á., S.C.-E., R.M.-D., J.V.-C. and L.R.-d.-l.-C.; investigation, H.C.-A. and E.S.-d.-Á.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.-A. and E.S.-d.-Á.; writing—review and editing, H.C.-A., E.S.-d.-Á., R.M.-D., S.C.-E., L.R.-d.-l.-C. and J.V.-C.; visualization, H.C.-A., R.M.-D., S.C.-E., E.S.-d.-Á., J.V.-C. and L.R.-d.-l.-C.; supervision, S.C.-E.; project administration, S.C.-E.; funding acquisition, S.C.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted within the framework of the project “Implementation of the Strategic Action Program (SAP) for the Gulf of Mexico Large Marine Ecosystem (GoM-LME)” (ID 6952), funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The project is implemented by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and executed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS). It received in-kind co-financing from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources of Mexico (SEMARNAT), as well as from the Cartagena Convention and its Caribbean Regional Coordination Unit (CAR/RCU).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The ICAM-SIMAR-Integral is functional and available as part of the Marine Water Quality Early Warning System—1 km (SATwality), on the Marine and Coastal Information and Analysis System operational explorer (SIMAR) (https://simar.conabio.gob.mx/explorer/, accessed on 15 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Trust Fund for Biodiversity at CONABIO for their administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SIMAR | Marine and Coastal Information and Analysis System |

| TRIX | Trophic Index |

| WQIs | Water Quality Indices |

| ICAM | Marine Water Quality Index |

References

- Javed, S.; Ali, A.; Ullah, S. Spatial Assessment of Water Quality Parameters in Jhelum City (Pakistan). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riechers, M.; Brunner, B.P.; Dajka, J.-C.; Dușe, I.A.; Lübker, H.M.; Manlosa, A.O.; Sala, J.E.; Schaal, T.; Weidlich, S. Leverage Points for Addressing Marine and Coastal Pollution: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 167, 112263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holsman, K.K.; Haynie, A.C.; Hollowed, A.B.; Reum, J.C.P.; Aydin, K.; Hermann, A.J.; Cheng, W.; Faig, A.; Ianelli, J.N.; Kearney, K.A.; et al. Ecosystem-based fisheries management forestalls climate-driven collapse. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuatters-Gollop, A.; Guérin, L.; Arroyo, N.L.; Aubert, A.; Artigas, L.F.; Bedford, J.; Corcoran, V.; Dierschke, S.A.M.; Elliott, S.C.V.; Geelhoed, A.; et al. Assessing the state of marine biodiversity in the Northeast Atlantic. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeed, M.M.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Karim, M.R.; Uddin, M.F.; Hasan, M.; Khan, R.H. Surface Water Quality Profiling Using the Water Quality Index, Pollution Index and Statistical Methods: A Critical Review. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 18, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Angel, E.; Sebastias-Frasquet, M.; Millán-Nuñez, R.; González-Silvera, A.; Cajal-Medrano, R. Anthropocentric bias in management policies. Are we efficiently monitoring our ecosystem? In Coastal Ecosystems: Experiences and Recommendations for Environmental Monitoring Programs; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296950802_Anthropocentric_BIAS_in_management_policies_Are_we_efficiently_monitoring_our_ecosystems (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Uddin Md, G.; Moniruzzaman, M.d.; Quader, M.A.; Hasan, M.A. Spatial Variability in the Distribution of Trace Metals in Groundwater around the Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant in Ishwardi, Bangladesh. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meran, G.; Siehlow, M.; Von Hirschhausen, C. Integrated Water Resource Management: Principles and Applications. In The Economics of Water; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 23–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D. Water Quality Assessments: A Guide to the Use of Biota, Sediments and Water in Environmental Monitoring, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEDEX La Calidad de las Aguas. Libro Blanco del Agua en España; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2000. Available online: https://ceh.cedex.es/web/documentos/LBA/LBA.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Abirami, A. Marine Pollution and Waste Management. J. Law Leg. Res. Dev. 2024, 1, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda Cirerol, N. Eutrofización y Calidad del Agua de Una Zona costera Tropical; Universitat de Barcelona, 2004. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2445/35296 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Uddin, M.G.; Nash, S.; Rahman, A.; Olbert, A.I. A Comprehensive Method for Improvement of Water Quality Index (WQI) Models for Coastal Water Quality Assessment. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Patil, R.S. A Comparison of Water Quality Indices for Coastal Water. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2003, 38, 2711–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenweider, R.A.; Giovanardi, F.; Montanari, G.; Rinaldi, A. Characterization of the Trophic Conditions of Marine Coastal Waters with Special Reference to the NW Adriatic Sea: Proposal for a Trophic Scale, Turbidity and Generalized Water Quality Index. Environmetrics 1998, 9, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin Md, G.; Nash, S.; Olbert, A.I. A Review of Water Quality Index Models and Their Use for Assessing Surface Water Quality. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, P.J.; Green, E.P.; Edwards, A.J.; Clark, C.D. The Cost-Effectiveness of Remote Sensing for Tropical Coastal Resources Assessment and Management. J. Environ. Manag. 1999, 55, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthus, T.J.; Mumby, P.J. Remote Sensing of the Coastal Zone: An Overview and Priorities for Future Research. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 2805–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollett, I.; Mumby, P.J.; Müller-Karger, F.E.; Hu, C. Physical Environments of the Caribbean Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2012, 57, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.K. An index-number system for rating water quality. J. Water Pollut. Control. Fed. 1965, 37, 300–306. [Google Scholar]

- Marine Water Quality Alert System (SATwality Marine-Coastal Information Analysis System (SIMAR). CONABIO. México. Available online: https://simar.conabio.gob.mx/explorer/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; Martell-Dubois, R.; Valdéz, J.; Ressl, R. Daily 1-km Satellite Chlorophyll-a Concentration (CHL). Satellite-Based Ocean Monitoring System (SATMO). Marine-Coastal Information and Analysis System (SIMAR), CONABIO, Mexico, 2018. Available online: https://simar.conabio.gob.mx/explorer/?satmo=chl1 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; Martell-Dubois, R.; Valdéz-Chavarin, J.; Rosique-de la Cruz, L.; Perera-Valderrama, S.; López-Perea, J.; Caballero-Aragón, H.; Ressl, R. Nitrate Concentration in Surface Sea Water (NO3) at 1 km. Ocean-Atmosphere Climate Model System (SIMOD). Marine-Coastal Information and Analysis System (SIMAR), CONABIO, Mexico, 2021. Available online: https://simar.conabio.gob.mx (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; Martell-Dubois, R.; Valdéz, J.; Ressl, R. Daily 1-km Satellite Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient of the Downwelling Irradiance at 490 nm (KD490) at 1-km. Satellite-Based Ocean Monitoring System (SATMO). Marine-Coastal Information and Analysis System (SIMAR), CONABIO, México, 2021. Available online: https://simar.conabio.gob.mx (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; Martell-Dubois, R.; Valdéz, J.; Ressl, R. Daily 1-km Satellite Secchi Disk Depth (ZSD). Satellite-Based Ocean Monitoring System (SATMO). Marine-Coastal Information and Analysis System (SIMAR), CONABIO, Mexico, 2018. Available online: https://simar.conabio.gob.mx (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; Martell-Dubois, R.; Valdéz-Chavarin, J.; Rosique-de la Cruz, L.; Perera-Valderrama, S.; López-Perea, J.; Caballero-Aragón, H.; Ressl, R. Dissolved Oxygen on the Sea Surface (O2) at 1 km. Ocean-Atmosphere Climate Model System (SIMOD). Marine-Coastal Information and Analysis System (SIMAR), CONABIO, Mexico, 2021. Available online: https://simar.conabio.gob.mx/explorer/?satmo=o2 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- OCEANCOLOUR_GLO_BGC_L4_MY_009_104. Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS). Marine Data Store (MDS). Available online: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/OCEANCOLOUR_GLO_BGC_L4_MY_009_104/description (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- NEMO-PICIS GLOBAL_ANALYSISFORECAST_BGC_001_028 Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS). Marine Data Store (MDS). Available online: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_ANALYSISFORECAST_BGC_001_028/description (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- CMEMS-OC-QUID-009-101to104-111-113-116-11830. Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS). Marine Data Store (MDS). Available online: https://documentation.marine.copernicus.eu/QUID/CMEMS-OC-QUID-009-101to104-111-113-116-118.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- CMEMS-GLO-QUID-001-028. Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS). Marine Data Store (MDS). Available online: https://documentation.marine.copernicus.eu/QUID/CMEMS-GLO-QUID-001-028.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Srivastava, G.; Kumar, P. Water quality index with missing parameters. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2013, 02, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, T.D.; Kumarasamy, M.V. Development of Water Quality Indices (WQIs): A Review. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 29, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.G.; Nash, S.; Mahammad Diganta, M.T.; Rahman, A.; Olbert, A.I. Robust Machine Learning Algorithms for Predicting Coastal Water Quality Index. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.G.; Nash, S.; Rahman, A.; Olbert, A.I. Performance Analysis of the Water Quality Index Model for Predicting Water State Using Machine Learning Techniques. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 169, 808–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Glibert, P.M.; Burkholder, J.M. Harmful Algal Blooms and Eutrophication: Nutrient Sources, Composition, and Consequences. Estuaries 2002, 25, 704–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. PRIMER v7: User Manual/Tutorial; PRIMER-E, Ltd.: Plymouth, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Penna, N.; Capellacci, S.; Ricci, F. The Influence of the Po River Discharge on Phytoplankton Bloom Dynamics along the Coastline of Pesaro (Italy) in the Adriatic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 48, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall International: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Chen, W.; Liang, Y. Feasibility Study on the Least Square Method for Fitting Non-Gaussian Noise Data. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2018, 492, 1917–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F.; Katti, S.K.; Wilcox, R.A. Critical Values and Probability Levels for the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test and the Signed Rank Test; American Cyanamid Co., & Lederle Lab.: Pearl River, NY, USA, 1963. Available online: https://books.google.cl/books/about/Critical_Values_and_Probability_Levels_f.html?id=GS3aGAAACAAJ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Wilcoxon, F.; Katti, S.K.; Wilcox, R.A. Critical Values and Probability Levels for the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test and the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. In Selected Tables in Mathematical Statistics; Amer Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1970; Volume 1, pp. 171–259. [Google Scholar]

- Perdices, M. Null Hypothesis Significance Testing, p-Values, Effects Sizes and Confidence Intervals. Brain Impair. 2018, 19, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, D.; Neuhäuser, M. Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank Test. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1658–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, S.; Sawilowsky, S.S. A New Maximum Test via the Dependent Samples T-Test and the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test. Appl. Math. 2014, 5, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silveira, J.A.; Morales-Ojeda, S.M. Evaluation of the Health Status of a Coastal Ecosystem in Southeast Mexico: Assessment of Water Quality, Phytoplankton and Submerged Aquatic Vegetation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 59, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Rodríguez, G.A. Grupos Funcionales del Fitoplancton y Estado Trófico del Sistema Laguna Topolobam-po-Ohuira-Santa María. Thesis, Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, 2008. Available online: http://www.repositoriodigital.ipn.mx/handle/123456789/13651 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Escobedo Urias, D.C. Diagnóstico y Descripción del Proceso de Eutrofización en Lagunas Costeras del Norte de Sinaloa. The-sis, Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, 2010. Available online: https://agua.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Diagn%C3%B3stico-y-descripci%C3%B3n-del-proceso-de-eutrofizaci%C3%B3n-en-Lagunas-costeras-del-Norte-de-Sinaloa.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Cacheux Martínez, E. Condición y Tendencia Ambiental de la Bahia de Guaymas, Sonora, México. 2019. Available online: https://rinacional.tecnm.mx/jspui/handle/TecNM/7352 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Jimenez-Quiroz, M.D.C.; Funes-Rodriguez, R.; Hernandez-Trujillo, S.; Gonzalez-Armas, R.; Ana-ya-Godinez, E. Interannual Variability in the Trophic Status and Water Quality of Bahía Magdalena, Mexico, During the 2015–2018 Period: TRIX. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 42, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Velarde, P.M.; Alonso-Rodríguez, R.; Domínguez-Jiménez, V.P.; Calvario-Martínez, O. The Spatial Distribution and Seasonal Variation of the Trophic State TRIX of a Coastal Lagoon System in the Gulf of California. J. Sea Res. 2023, 193, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrter, J.C.; Ko, D.S.; Murrell, M.C.; Hagy, J.D.; Schaeffer, B.A.; Greene, R.M.; Gould, R.W.; Penta, B. Nutrient Distributions, Transports, and Budgets on the Inner Margin of a River-Dominated Continental Shelf: Louisiana Shelf Nutrient Dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2013, 118, 4822–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, H.; Janicki, A.; Sherwood, E.T.; Pribble, R.; Johansson, J.O.R. Ecosystem Responses to Long-Term Nutrient Management in an Urban Estuary: Tampa Bay, Florida, USA. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2014, 151, A1–A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Arancibia, A.; Day, J. Ecological Characterization of Terminos Lagoon, a Tropical Lagoon-Estuarine System in the Southern Gulf of Mexico. Ecology of Coastal Ecosystems in the Southern Gulf of Mexico Region of the Lagoon of Términos 5: 1–26. 1982. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284543972_Ecological_characterization_of_Terminos_Lagoon_a_tropical_lagoon-estuarine_system_in_the_Southern_Gulf_of_Mexico (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Herrera-Silveira, J.A.; Comin, F.A.; Aranda-Cirerol, N.; Troccoli, L.; Capurro, L. Coastal Water Quality Assessment in the Yucatan Peninsula: Management Implications. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2004, 47, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenz, C.; Fichez, R.; Silva, C.Á.; Benítez, L.C.; Conan, P.; Esparza, A.C.R.; Denis, L.; Ruiz, S.D.; Douillet, P.; Martinez, M.E.G.; et al. Benthic Ecology of Tropical Coastal Lagoons: Environmental Changes over the Last Decades in the Términos Lagoon, Mexico. Comptes Rendus. Géoscience 2017, 349, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.M.; Carrillo, L.; Jarquín-Sánchez, A.; Alcérreca-Huerta, J.C.; Álvarez-Merino, A.; Lázaro-Vázquez, A. Transport of Nutrients into the Southern Gulf of Mexico by the Grijalva–Usumacinta Rivers. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e14838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Terrones, L.; Rebolledo-Vieyra, M.; Merino-Ibarra, M.; Soto, M.; Le-Cossec, A.; Monroy-Ríos, E. Groundwater Pollution in a Karstic Region (NE Yucatan): Baseline Nutrient Content and Flux to Coastal Ecosystems. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2011, 218, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, B.E.; Brewton, R.A.; Herren, L.W.; Porter, J.W.; Hu, C. Nitrogen Enrichment, Altered Stoichiometry, and Coral Reef Decline at Looe Key, Florida Keys, USA: A 3-Decade Study. Mar. Biol. 2019, 166, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Aragón, H.; Alcolado, P.M. Condición de arrecifes de coral sometidos a presiones naturales recientes: Bajos de Sancho Pardo, Cuba. Rev. Mar. Cost. 2011, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoretto, F.; Mascareñas-Osorio, I.; León-Deniz, L.; González-Salas, C.; Pérez-España, H.; Rivera-Higueras, M.; Ruiz-Zárate, M.-Á.; Vega-Zepeda, A.; Villegas-Hernández, H.; Aburto-Oropeza, O. Being Isolated and Protected Is Better Than Just Being Isolated: A Case Study From the Alacranes Reef, Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 583056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebich, R.A.; Houston, N.A.; Mize, S.V.; Pearson, D.K.; Ging, P.B.; Evan Hornig, C. Sources and Delivery of Nutrients to the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico from Streams in the South-Central United States1: Sources and Delivery of Nutrients to the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico from Streams in the South-Central United States. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2011, 47, 1061–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Carpenter, S.; Foley, J.A.; Folke, C.; Walker, B. Catastrophic Shifts in Ecosystems. Nature 2001, 413, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, S.C.; Fabry, V.J.; Feely, R.A.; Kleypas, J.A. Ocean Acidification: The Other CO2 Problem. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2009, 1, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulev, S.K.; Thorne, P.W.; Ahn, J.; Dentener, F.J.; Domingues, C.M.; Gerland, S.; Gong, D.; Kaufman, D.S.; Nnamchi, H.C.; Quaas, J.; et al. Changing state of the climate system. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 287–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseth, N.C.; Mysterud, A.; Ottersen, G.; Hurrell, J.W.; Chan, K.-S.; Lima, M. Ecological Effects of Climate Fluctuations. Science 2002, 297, 1292–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, T.; Dix, N.; Dunnigan, S.; Reddy, K.R.; Osborne, T.Z. Impacts of Hurricanes on Nutrient Export and Ecosystem Metabolism in a Blackwater River Estuary Complex. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Reyes, M.; Sydeman, W.J.; Schoeman, D.S.; Rykaczewski, R.R.; Black, B.A.; Smit, A.J.; Bograd, S.J. Under Pressure: Climate Change, Upwelling, and Eastern Boundary Upwelling Ecosystems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2015, 2, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glibert, P.M.; Maranger, R.; Sobota, D.J.; Bouwman, L. The Haber Bosch–Harmful Algal Bloom (HB–HAB) Link. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seybold, E.C.; Dwivedi, R.; Musselman, K.N.; Kincaid, D.W.; Schroth, A.W.; Classen, A.T.; Perdrial, J.N.; Adair, E.C. Winter Runoff Events Pose an Unquantified Continental-Scale Risk of High Wintertime Nutrient Export. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.E. Water Quality at the End of the Mississippi River for 120 Years: The Agricultural Imperative. Hydrobiologia 2024, 851, 1219–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetz, M.S.; Cira, E.K.; Sterba-Boatwright, B.; Montagna, P.A.; Palmer, T.A.; Hayes, K.C. Exceptionally High Organic Nitrogen Concentrations in a Semi-Arid South Texas Estuary Susceptible to Brown Tide Blooms. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 188, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Barnes, B.; Qi, L.; Corcoran, A. A Harmful Algal Bloom of Karenia Brevis in the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico as Revealed by MODIS and VIIRS: A Comparison. Sensors 2015, 15, 2873–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poor, N.; Pribble, R.; Greening, H. Direct Wet and Dry Deposition of Ammonia, Nitric Acid, Ammonium and Nitrate to the Tampa Bay Estuary, FL, USA. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, T.S.; DiMarco, S.F.; Cowan, J.H.; Hetland, R.D.; Chapman, P.; Day, J.W.; Allison, M.A. The Science of Hypoxia in the Northern Gulf of Mexico: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E.; Wiseman, W.J. Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia, A.K.A. “The Dead Zone”. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Díaz, G.Y.; Hernández-Ayón, J.M.; Zirino, A.; Herzka, S.Z.; Camacho-Ibar, V.; Norzagaray, O.; Barbero, L.; Montes, I.; Sudre, J.; Delgado, J.A. Understanding Upper Water Mass Dynamics in the Gulf of Mexico by Linking Physical and Biogeochemical Features. J. Mar. Syst. 2022, 225, 103647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Millan-Nuñez, R.; Gonzalez-Silvera, A.; Cajal, R. Comparison of in Situ and Remotely-Sensed Chl-a Concentrations: A Statistical Examination of the Match-up Approach. In Handbook of Satellite Remote Sensing Image Interpretation: Applications for Marine Living Resources Conservation and Management; Morales, J., Stuart, V., Platt, T., Sathyendranath, S., Eds.; EU PRESPO and IOCCG: Dartmouth, Canada, 2011; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, L.H. Environmental Sampling and Analysis: A Practical Guide; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, B.A.; Stauffer, B.A.; Young, D.A.; Sullivan, D.J.; Bricker, S.B.; Walbridge, M.R.; Clyde, G.A.; Shaw, D.M. Emerging Tools for Continuous Nutrient Monitoring Networks: Sensors Advancing Science and Water Resources Protection. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2016, 52, 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shi, W. The NIR-SWIR Combined Atmospheric Correction Approach for MODIS Ocean Color Data Processing. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 15722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobley, C.D.; Werdell, J.; Franz, B.; Ziauddin, A.; Bailey, S. Atmospheric Correction for Satellite Ocean Color Radiometry; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).