Abstract

This case study is an overview of architectural design solutions implemented in the construction of farming facilities and the technological processes necessary to support a sustainable farm that runs with nearly zero waste in a closed-loop system that functions with full energy independence. The research will thoroughly investigate the specific location and configuration of the farm units in the target area—providing an extensive description of all necessary building typologies and infrastructures. The text will provide a summary of the agricultural solutions implemented at the farm, which is located in the region of Vojvodina in the Republic of Serbia. This region consists mainly of fertile agricultural land and could be a template for further designs and innovations in sustainable farming. This case study concerns the design of a resilient and self-reliant farm complex that consists of multiple animal species (broilers, pigs, and cattle), including a biogas station. The study is meant to show that adjustments made in architectural design, variations in building typology, and smart urban planning can contribute significantly to the improvement of sustainability in agricultural practices. This case study demonstrates that investments in sustainable solutions not only benefit the environment but can also deliver significant economic returns for investors—thereby further stimulating growth and development in the field of sustainable agriculture.

1. Introduction

Sustainable innovations can be found throughout the disciplines, with similar ideas becoming increasingly present in the fields of architecture and agriculture. Modern farm designs are full of smart architectural solutions that are supported by current technologies and innovative materials that support the beneficial use of resources. However, the issue that arises repeatedly is as follows: to what degree do these advancements need to be implemented for each individual project? Vojvodina is a region in the Republic of Serbia that consists of 84% fertile agricultural soil, thereby making this area the main location of farming and agricultural complexes in the country [1]. Today, farms that were established in the past are facing new problems regarding production, the main factors being outdated facilities, feeding technologies, and agricultural processes. Strategies put forth by the government have put emphasis on the farming process, making it essential for agricultural producers to accept innovations in farming as a necessary investment. These potential improvements have to be implemented without the provision of support for agricultural solutions and urban planning. It is essential that the architectural design follows trends that allow the modern farm to function, while simultaneously resolving issues of sustainability within its scope of influence [2,3,4]. The process of providing such improvements must be approached with care, paying special attention to soil resource management and sustainable land planning. It is very encouraging that over the past years (between 2008 and 2013) soil resources in Serbia have not decreased, even with novel construction and changes in land use [5]. This aligns with the ideology of sustainable land management and the imperative of sustainable development goals in the field of agriculture. Government policies regarding this issue are well managed, and regulations addressing construction on agricultural soil allow only a few building types (related to agricultural functions) to be legalized and approved [6]. Unfortunately, the salvation of arable land is not a worldwide trend. Land is gradually being lost due to the requirements of urbanization and trends in population growth that greatly influence the influence processes of farming and food production methods, resulting in the need for all production to take place on a larger scale. For comparison, overbuilding on the nation’s agricultural land in Italy is estimated to occur at a rate of 55 ha per day [7]. The population growth rate in general is slowing down worldwide, but the overall world population reached had reached 8 billion in 2022 and is expected to continue to rise [8]. As farming (crop and animal production) is one of the primary avenues providing agricultural products for food production, it is necessary to make farm processes and technologies more effective and to reach a higher level of sustainability in certain aspects of farm architecture [9,10,11]. It is obvious that mankind is facing an ever-growing problem: the intersection of population growth and rising demand, in contrast with a decrease in productive agricultural land. Therefore, food production in the future will have to become more sustainable and productive than it is currently; simultaneously, farming practices will have to address the pressing environmental issues that are being faced by mankind on a global scale [12,13,14,15,16]. Farms have the role of managing natural resources and extensive sections of land in the countryside; this has a great effect on land use, the ecosystem, and ecological functions [17,18,19]. Therefore, sustainable farming must start at the management level, with decisions to use less intensive farming techniques and implement as many environmentally friendly farming practices as economically feasible [20,21,22,23].

Urban planning and architectural solutions will play an important role in the resolution of this issue [24,25,26,27]. Farm complexes exist as independent entities, with their own specific needs and parameters in morphology, but at the same time have the same fundamental principles as are used in urban planning. All man-made environments consist of constructed buildings and the open spaces between them. Despite contemporary practices, which are primarily driven by economic profit, it should be noted that an understanding of the constructed environment and the many layers of the processes required enables equal consideration of both open and closed spaces [28,29]. Both aspects need to be observed in order to generate quality farm design. Furthermore, the undertaking of farm reconstruction or the creation of new complexes can support new architectural, construction, and technological solutions that can contribute to a lowered environmental impact and acceptable LCA when implemented into designs [30,31,32,33]. The design of buildings for such specialized use generates a specialized branch in architectural design. An understanding of the processes, needs of animals and employees, technology, location, economic environment, and the natural environment is vital for successful production on farms [34,35]. Architecture must provide the means for achieving effective results, economic benefit, social interaction within the context of its surroundings, ecosystem support, and the implementation of sustainability principles.

Modern farms are implementing new architectural solutions in their designs. Most of these solutions can be seen in the domain of locally sourced materials, modern design, ease of function (feeding, movement, and treatment), an increase in usage of natural processes, and a decrease in the cases of energy loss [36,37,38,39]. New farm complexes, particularly livestock farms, increasingly employ biogas digesters (anaerobic digesters) as part of their integrated sustainable waste and energy management strategies. Biogas digesters provide a power supply for the farm and generate an additional line of income from the sale of energy.

What separates this case study from the other modern farm complexes is

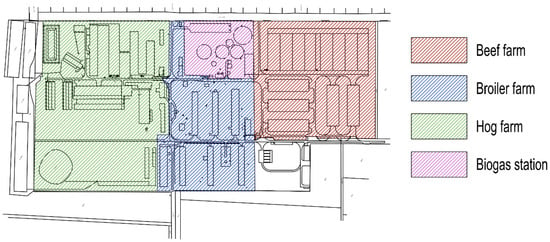

- Multiple livestock species in one location (broilers, pigs, and cattle) (Figure 1).

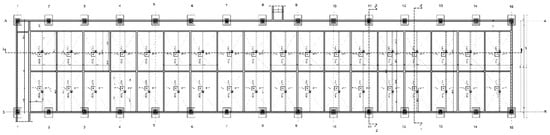

Figure 1. Farm complex arrangement—three different farms and biogas station at one location.

Figure 1. Farm complex arrangement—three different farms and biogas station at one location. - Additional installations to support a full energy cycle that enables zero waste on the lot (utilization of waste produced heat from a cogeneration plant applied on-site) (Figure 1).

- Design of a durable complex that can be easily maintained long term.

- Landscaping treatment of open spaces.

- Full energy independence.

These aspects, combined with technologies and innovative building solutions, make this farm complex more resilient and sustainable. With smart, sustainable design, it is possible to achieve successful, near-zero waste production that simultaneously meets all three pillars of sustainability: social, economic, and environmental.

The aim of this case study, in particular, is to elaborate on the architectural design that contributes to sustainable construction and to examine the technological processes implemented through

- Necessary building typologies and infrastructure.

- Architectural solutions.

- Building materials.

- Urban disposition of all farm units on the lot.

While addressing how the various aspects of design mentioned above contribute to the energy efficiency of the farm and the rate of recycling. These points cover most of the segments of environmental concerns and sustainability goals that LCA studies recognize in relation to farm activities like the breeding and fattening of livestock, the housing of fattening animals, the storage of manure, and solutions, in particular, for the management of the emissions created from this waste [40].

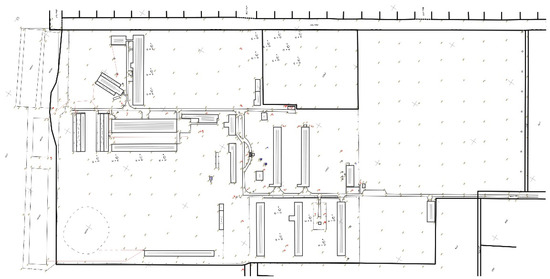

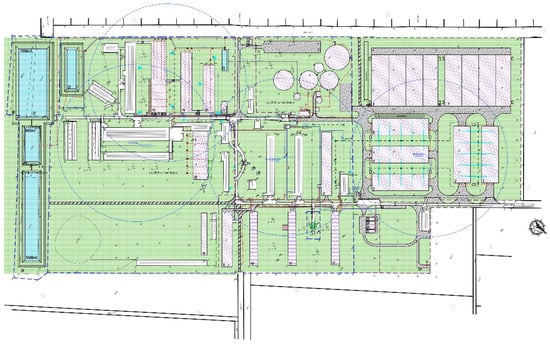

The study includes a description of the location before reconstruction (Figure 2) and initial design ideas, followed by a review of building typologies (Figure 3). Architectural details and urban facets of the farm have focused on the aspects of sustainable design. The final section of this study contains the key findings, along with suggestions for possibilities for the further development of modern, sustainable farms.

Figure 2.

Existing situation before the new, sustainable design.

Figure 3.

Urban solution for the farm final design with existing and new buildings.

2. The Current State of the Site and the Sustainable Concept for Its New Design

The investor holds ownership of an existing farm complex in Novo Orahovo (near Subotica) which was built in 1946. The farm historically produced pig and chicken meat. The complex was consistently upgraded over the course of the years, but never had a complete reorganization of its architectural, urban, and technological designs. However, to a certain degree, it still evolved to meet the new functional needs of agriculture [6]. The existing housing for livestock is specific to the current types and numbers of animals involved, thereby influencing the dimensions of their enclosures accordingly.

Over the years, the quantity of animals has increased following economic trends and the requirements of the market. The farm is surrounded by 800 ha in agricultural land, which is all owned by the same investor; this land is used to produce food for the existing livestock, and the rest of the yield is sold, partially, to third parties.

In general, the work of architects and civil engineers has always aimed at combining the needs of agricultural production and functional requirements, taking into consideration various constraints while utilizing already existing knowledge [41]. When the reconstruction of the farm complex was considered, the focus was shifted to modern production technologies, renewable energy sources, and sustainable architecture. The goal was to fully close the production cycle with strategies such as using solar energy, optimizing the use of water, providing nutrient-rich soil, and supporting seed growth to optimize the collection of sunlight and solar energy in plants. Farms breed livestock to produce meat; animals digest plant matter, leaving manure as a by-product. Manure is used as a raw material for the digestion process in biogas production, generating electricity via a cogeneration plant, providing a secondary product from a cooled cogeneration plant system, which produces hot water at 93 °C. The water is then used to heat the farm facilities. The electric energy produced is used for the purposes of the farm, while also being sold to the electric distribution services of the Republic of Serbia along with other farm products. Digestion masses are pushed through separators which divide this mass into water with a 1–2% biomass and compost with a 77% biomass. The products generated have no odor and the surrounding agricultural land can then be watered and fertilized with this residue. Compost can also improve the quality of agricultural land and improve the quality of the newer plants being grown, thus closing the cycle of multi-phase use of solar energy. To provide for all of the necessities, a decision was made to incorporate a biogas power plant at the location to eliminate waste and to enable the energy independence of the farm. Special attention was paid to utilizing the excess heat waste that is usually generated by biogas plants and redirecting it toward further use in the processes of the plant. Usually, heat that is gained through the digestion process is released in the atmosphere, creating a negative effect on the environment. Modern farms that have biogas stations within the complex rarely employ the use of this extra heat, as its utilization requires further investment in the additional infrastructure needed. Designs geared toward the prevention of such heat waste are beneficial for the welfare of the ecosystem, but can also be geared toward providing benefits for the farm—this excess heat could be redirected to produce hot water for heating broilers, piglets, and the offices, eliminating the need for the use of other energy sources and thereby reducing long-term added costs.

To enable day-to-day functioning, an adequate amount of raw material had to be provided for the biogas plant, namely the right mixture of manure and biomass, meaning the right quantity of animals had to be available on the farm. This is a number that is hard to obtain since livestock breeding is dictated by trends in the meat market. The design had to allow for a certain amount of flexibility, where a reduction in manure could be compensated for with biomass. This meant that the farm’s existing capacities had to be increased and that new facilities had to be functionally connected to the buildings that were already present on site, while old facilities needed some architectural and technological upgrades. The decision to include an additional species of animal (cattle) in addition to the swine and broilers was made considering two deciding factors: manure improving the function of the digestion process unit within the biogas station and the farm offering three types of meat product to the market, making the complex more resilient to market changes. Usually, modern farms are breeding one species, driven by the goal of uniformity in buildings, processes, and employment of staff. Narrowing the field of production and specialization of the processes has been the goal of many fields over the last few decades, with architecture following emerging needs and functions. While the specialized evolution of architectural design for different building typologies is welcomed, architects are not fond of the repetition of structures and production of urban concepts through the simple repetition of buildings, even though this example has been repeated throughout history [42,43,44]. Every facility design needs to be borne out of a wider scope of influence, such as location and the needs and functions of the facility and its users [45,46,47,48].

All of these factors were put into consideration, meaning that there were three separate farms next to one another at the same location to form this unique complex. Veterinary regulations in the Republic of Serbia tend to incorporate EU standards and they dictate that every farm must have fencing, controlled gates with entryways and disinfection barriers, an appropriate distance between buildings, etc. All of these design aspects were provided for at each animal facility and were integrated to function as a whole using one biogas station, a mutual installation system, a mutual sewage system, etc. The overall solutions for eliminating waste and the internal provision of all of the necessary energy supplies for the farm are unique in the area of Vojvodina. Many of these elements have been developed individually at other farms, but never on this scale and without energy independence. The specificity of this case study is the mixture of materials that are put into the digestion units. Many farms build biogas stations for electric power production with the sole intent of re-selling the energy to the electrical grid, while taking care of a large amount of farm waste. Often, farms do not have their own arable land to provide food for animals or raw material for the digestion process of the biogas plant; this issue is usually resolved by purchasing food from the livestock market. On the other hand, companies with no farms in their possession choose to produce green energy through biogas production and do so by purchasing the raw materials. In this case study, the existing state of the farm was upgraded and a variety of solutions for biogas station raw materials were provided so that energy production would still have constancy in case some of the input avenues failed to deliver.

In addition to setting and distributing all of the necessary facilities and infrastructures on the location, emphasis was put on urban design and landscaping of the complex. Typically, farms are focused on function and economic gain: speed in production, the functionality of buildings, and the systems that facilitate these goals. The surrounding areas of the buildings are submitted to functional roles, in part (roads, plateaus, and other manipulated surfaces), as the areas left over are usually not subject to any kind of intervention.

The available location of the existing farm formed a rectangular-shaped area of 250,000 m2. All existing buildings were retained, with the necessary upgrades being implemented. As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 3, the design team developed a solution for the farm complex that consists of

1. Three farms in the same location, separated with fences and gates (in accordance to veterinary regulations):

1.1. Farm facility for cattle husbandry, capacity of 2000 bulls in turn or 1.5 × 2000 = 3000 per year.

1.2. Farm facility for swine husbandry, capacity of 600 sows or 16,000/20,000 fattening animals.

1.3. Farm facility for broiler feeding, capacity of 100,000 pieces per turn or 500,000 per year.

2. Biogas station with digestion units, capacity 1 MW.

3. Office and genetics facility.

4. Installation infrastructure for electricity, water, and sewage.

5. Infrastructure for traffic and communication corridors between buildings.

6. Lagoons for the storage of liquid manure and purified water from the biogas plant.

It is important to emphasize that all solutions implemented in the architectural design of the buildings, the optimal positioning of the buildings, the functions of the buildings, the supporting infrastructures, and the selection of technologies took into consideration aspects of sustainability, environmental impact, conditions of animal facilities, and their care, while maintaining an economic benefit for the investor in the process of production.

3. Project Execution: Materials and Technological Processes

Buildings for animal husbandry are the focus point of every farm complex, but these facilities cannot operate and complete their tasks if the other constituents of the complex are not functioning properly, placed appropriately, and working in connection. In addition to the livestock enclosures, each farm has several specialized buildings that serve a particular function, along with storage for machinery and equipment.

The structures intended for animal husbandry also need to provide space for all necessary equipment and technology. The size and amount of equipment also determines the architecture and the structural needs of each building. Sometimes the structure of a building can help to resolve certain technological issues. The design of a building is dictated by the various purposes it is used for such as functionality, maintenance, hygiene, the placement of technology and the maximization of natural processes (ventilation and lighting), durability, availability of space on the lot, and the comfort, safety, and the health of the animals. Other factors that need to be taken into consideration; veterinary parameters, aesthetics, cost effectiveness, sustainability, and the minimization of pollution. All of these factors were taken into consideration, and the farm system has been functioning efficiently since 2019 to date.

Another factor to take into consideration is that the needs of animals vary depending on the species, thereby affecting the structures they live in and the technological solutions used in the design and construction of their enclosures. It is crucial to select proper equipment for the care of the animals, thus dictating all other aspects of design. The tendency is to see a variety of animal species, (swine, poultry, and cattle) housed together on small private farms and farmsteads. Specialized farms generally house animals homogeneously; this highlights the specificity of this case study as it is a large farm complex that evolves into housing a variety of livestock. The farm in question originally had two species in breeding but, due to the needs of the biogas station for additional organic materials, the need arose for the introduction of cattle. Expansion of the farm had already been carried out on the free space existing within the parameters of the farm itself, while care was taken not to encroach on the surrounding arable land.

When looking to increase the capacities of the farm, its proximity to a settlement had to be taken into consideration. It became necessary to adhere to urban expansion practices and to provide an environmental impact assessment of the location, which was conducted through legal processes, through the Regional Planning Department MDCP. Sustainable design with no waste storage or leftovers, odor elimination, and smart landscaping were crucial factors in obtaining a building permit for this location. The care taken in proper design practices was a deciding factor in preventing conflicts of interest (due to manure and waste management issues) that might have arisen due to concerns about the proximity of this large farm complex in an urbanized area.

3.1. Buildings for Animal Husbandry

Cattle housing units are in fact low-tech facilities (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Cattle only need shelter and a windbreak; therefore, no cooling or heating system is required within the building. Four cattle housing facilities were planned as part of the overall design, with space reserved for one additional building if the farm’s capacity were to grow. Two of the five buildings are used as necessary quarantine (minimum 30 days) in situations where livestock are imported from abroad. Subsequently, these facilities function as a classic building for cattle fattening. Four of the buildings have implemented in phase one–three cattle enclosures and one quarantine building.

Figure 4.

Buildings for cattle breeding, effectively incorporated on the lot.

Figure 5.

The interior of the cattle breeding building. Modern technology incorporated with natural processes (lighting and ventilation).

Bearing in mind that a fully grown bull can weigh 550 kg by the time it is transported away from the facility, the buildings must have a durable and jolt-resistant base. Additionally, the lower sections of these structures are also in constant contact with manure and ammonia which corrode the materials at the base of the structure. In regard to this issue, concrete has proven to be the most effective in resisting these factors, as opposed to steel or wood. The structural system is made of prefabricated reinforced concrete elements (pillars, beams, and girders). The entire construct is then covered with insulated panels on the roof. A steel structured skylight was implemented at the top of the roof to provide natural light as well as ventilation of the facility. The walls on the lower section of the building had to be made of reinforced concrete due to the previously mentioned need for resistance to the impact of the animals housed. This material played another important role by protecting the livestock from wind, especially during the winter months, where temperatures can reach sub-zero. The height of the wall segment was 1.60 m while the remaining portions of the walls needed to be made from materials that allowed for air flow within the building, as air quality is of key importance for proper cattle husbandry. Therefore, a windproof netted material was chosen for the upper section of the enclosure, establishing a natural flow of air and proper ventilation, with the added help of the previously mentioned light fixture on the roof. The planned capacity for each building was 400 bulls (a total of 2000 in five facilities) with 20 enclosures per building, and 20 animals per enclosure. The buildings are rectangular, with dimensions 80.70 × 23.80 m, with a usable surface area of 1862.49 m2 and gross surface area of 1920.67 m2. Facilities are equipped with a water supply, as well as electrical installations for lighting. All of the necessary equipment was provided by System Line.

The floor slab of the building was constructed in a way that would ensure the simplification of the handling and collection of manure (Figure 5). Effectively, a major portion of the task is conducted by the animals themselves. The concrete floor is elevated by 7% near the walls where animals gather; the bulls push the straw down toward the central corridor, leaving the 10 cm deep bedding behind. The central corridor is built with dimensions that allow for machinery to scrape and collect manure unimpededly. The floor in the middle section is level and the manure is pushed out of the building and taken to the concrete plateaus designed for its storage. Floors that are inclined at a lesser degree, 5%, for example, retain too much of the soiled straw beneath the animals, while a greater incline at 9% leaves too much of the concrete surfaces uncovered. Therefore, the incline at which the floors are constructed is a carefully considered process, rather than an arbitrary percentage.

The buildings housing the bulls are cleaned daily; as the manure is essential to the functioning of the biogas station, it is of vital necessity that the manure is frequently and efficiently collected (50 t per day), once again demonstrating that the degree of elevation was a crucial detail rather than a random implementation into the architectural design.

It was imperative that the fences dividing the enclosures be functional and adaptable as cattle must be frequently redirected, divided up, or put into different groups, sometimes even several times a day. Ideally, the movement of the cattle should be conducted with minimal effort to save time and manpower, while also reducing the possibilities of animals getting injured in the process and ensuring their safety. Gates were made to be demountable, with double hinges so that they could be opened at both ends, adjusting to the needs of the farm at any given moment. Every box can be opened and merged with the next one or several gates at the same time. These gates can be set up to restrain one bull, in case they require medication or other veterinary interventions. This design makes the gates multifunctional and not just a single-use tool for enclosing livestock.

Watering points have been specially designed to prevent water from freezing. The water tanks have floating balls in them that require the animals to move them in order to access the water. The movement of the ball prevents the water from freezing. One enclosure houses 20 animals and has one watering point. Therefore, the ball is moved fairly frequently, and this simple innovation eliminates the need for equipment and power expenditure to heat the water tanks.

Passive architectural design methods were implemented to harness natural energy sources. By supporting natural ventilation and providing adequate shading, the need for additional artificial ventilation was reduced to a minimum.

Another aspect of the design involved plans to construct two silo trenches, one to store feed and the other for additional mass storage that could also be used for the biogas power plant. One example is fermented corn, which provides a good amount of energy and is a readily available crop on the land surrounding the farm. The dimensions of the building are 94 × 73 m, the usable area 6789 m2, and the gross area 6862 m2. Access to the building is through internal roads on the plot. These structures are without roofing. The buildings are made of reinforced concrete and consist of base strips, reinforced concrete walls, and flooring. In the first phase of reconstruction, one silo trench was built.

Overall, cattle farm needs the following structures to function properly:

- Buildings for animals.

- Food silos.

- Silo trench building.

- Manure plateau (placed next to the biogas system in this design).

- Roads.

- Fences and gates.

- Disinfection barriers.

The buildings within the farm need to be distributed in a way that requires a minimal amount of road surface. However, there is a need for some distance between buildings to ensure that fire safety, solar, and air-conditioning requirements are met. In the Republic of Serbia, the trend is to follow EU standards of regulation, resulting in major changes regarding fire safety regulation in the recent past. All of the buildings within the property have been placed in a straight line allowing for the simple solution of using one roadway. The trench silo runs parallel to one side of the road. This positioning allows for one road to serve multiple buildings. Cattle tend to produce a lot of manure; usually, this mass is transported with the help of machinery and the enclosures housing cattle are situated close to the biogas production facility, with the manure plateau being placed closest to the biogas complex, optimizing manure management, reducing time investment, minimizing the expenditure of resources, and decreasing the need for manpower.

The design and technology implemented at the poultry facilities varies depending on the program that is in function—egg production, pullet production, broiler production, or broiler feeding. Plans were made to reconstruct three broiler feeding facilities in addition to already existing buildings that were not part of the design plan. Plans were also made to facilitate an improvement in quality of life for the existing livestock within the already existing buildings. The first step was to implement a heating system powered by the biogas plant. The existing buildings were not equipped with cooling, heating, or ventilation systems which resulted in notable losses in broiler numbers. Over the course of 35 days a batch of broilers have various needs in terms of temperature control. During the first 8 days, the animals require a temperature of 38 °C, and in the following 5 days 28 °C, after which they grow a thicker set of feathers and require a reduction in temperature, especially after they have surpassed a weight of 1.2 kg. There is an additional need for cooling to increase once the animals have surpassed 2.2 kg in weight. The most cost-effective way to cool the building is through the use of evaporative cooling pads (that have been implemented into the plans for the newer facilities). The water pads function with the help of air passing over water slopes found on their surface. This is a solution that is very energy effective; in the meantime, fans are used for ventilation and hot water is utilized from the biogas plant to heat the buildings. One of the greatest deficits of the existing buildings is a lack of technologies to navigate temperature control. Buildings designed for broiler feeding are advanced in technology; designs for newer facilities are often based on Big Dutchman technology, a company that has representation in Serbia.

Overall, a broiler feeder farm needs the following buildings for functioning:

- Buildings for animals.

- Food silos.

- Manure plateau.

- Roads.

- Fences and gates.

- Disinfection barriers.

The positioning of the buildings is a result of the already existent placement of buildings at the location. Manure management is performed with machinery. When constructing the newer facilities, it would be of interest to place the manure plateaus as close to the biogas complex as possible; this would optimize the process of deriving energy from biogas.

The hog section of this complex houses the most complex technological processes of husbandry in comparison to the fattening of poultry and cattle. Unlike the latter, where young animals are purchased in the market and brought into facilities for husbandry, hog piglets are produced on location, directly from the embryo. Genetic material is produced on the farm, where the selection of sows is also performed. Unlike broilers or cattle that stay in the same building throughout the whole process, hogs change their dwelling depending on their weight and age. Therefore, hog farms have specialized buildings for every stage of hog husbandry. All building types are very dependent on technology since the process is highly controlled, conducted in the total confinement concept to ensure stabilized temperature and to distribute economic gains evenly over the course of the year.

The buildings housing the hogs rely heavily on technology for temperature control, ventilation, the feeding process, and manure collection, with the set-up being different for every building as they house different types of hogs. The implemented technology and necessary equipment was provided by VOS-system.

The case-study farm already had existing hog buildings for all phases of animal husbandry. Some of them remain dated, but others have been brought up to task or have been constructed in the recent past. New capacities and buildings were added to the existing ones and functions were added.

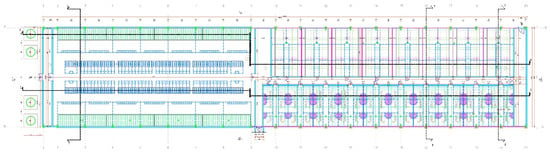

The newly designed section of the hog farm is divided into three types of buildings in which main phases of breeding take place:

1. Building for insemination of sows, farrowing, sows with piglets, and the nursery department (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Early phase of hog breeding, insemination, and farrowing in one section; piglets and nursery in the second part of the building.

2. Pre-fattening department.

3. Fattening department.

The building for the insemination of sows, farrowing, sows with piglets, and nursery department has a rectangular foundation with dimensions of 21 × 101 m. The total usable area of the building is 2007.36 m2, while the gross area of the building is 2121 m2. The structure of the building is made of prefabricated reinforced concrete elements. The pillar and the beam to the ridge constitute a unique element, which is set at an axial range of 5.15 m and 5.75 m. Different ranges were dictated by the three types of technology which were set in the building (feeding equipment, size of the boxes for animals, sanitary conditions…). The pillars are secured on reinforced concrete foundations with parapet beams. The walls have masonry parapets and thermo-insulating panels along the rest of its height. The roof cover that is placed on the prefabricated concrete beams consists of sandwich panels with polyurethane.

The building consists of several functional units, each designed with suitable equipment and technology. It is evident in the ground floor plan that the inner organization of space, divisions, fencing, and feeding divide the facility into three specialized sections. Insemination is conducted in the central part on the left end of the floor plan. Each sow has its own stall. Feeding is oriented towards the central corridor, leaving the back end of the animal within easy access for veterinary interventions. After insemination, sows are placed in the stalls to wait on farrowing after which the sow and its litter is moved to the next section. Relocation is necessary because the organization of the stall changes significantly at this stage. The sow and piglets are placed in the same box but sow movement is limited with a demountable fence. This entrapment prevents accidental injuries that can be attained by piglets from the sow and its weight (stepping on them, laying on them). On the 28th day, the approximately 9–12 kg piglets are separated from the sow and redirected to the nursery due to changing needs for space and stall organization. The sow is then ready for another farrowing in 3–5 days and is again relocated to the insemination stalls. The nursery represents the most sensitive phase in hog husbandry. During this period, piglets are still young, they consume solid food for the first time (until this phase they have had only milk), they get their vaccines, and create a new hierarchy in the stall. The stall houses 40 animals giving 0.45 m2 of space per piglet (20 m2 at average per box). Temperature is controlled at 28 °C with heating strips in the wall and fencing. The hot water for heating is provided by the operations of the biogas station.

When the piglet reaches 40 kg, it moves on to the next phase of husbandry: fattening. Each of the sections of the building is separated by walls due to the different requirements in temperature. This fattening phase is divided into two segments: the pre-fattening department and fattening department. The technology and the architecture of the buildings, the size of the stalls, and their organization with corridors remain the same. The buildings differ only in the size of hogs placed in them. Since the fattening phase includes animals from 40 to 105 kg, the decision was made to separate the early phase of fattening from other processes, because one stall that fits a certain number of animals in the early phase does not provide enough space in the later phases, which would result in having to relocate the animals again. The space provided for one hog is 0.85–1 m2, giving stalls of 20 m2 on average. The structure of the buildings is made of prefabricated pre-stressed concrete elements. The pillars and the beams provide unique elements that are set at an axial range of 6.14 m. The dimensions of the pre-fattening building are 16 × 85.5m (net 1341.77 m2, gross 1367.19 m2), and for the fattening building 16 × 65 m (net 1017.96 m2, gross 1072.82 m2). The pillars are secured on the reinforced concrete foundations with parapet beams. The walls have masonry parapets and thermo-insulating panels along the rest of their height. The roof cover that is placed on prefabricated concrete corneas is a thermal insulation panel. These buildings are constructed in a way that there is no need for heating systems.

All of the hog buildings are connected to each other by enclosed hallways to enable the safe relocation of animals under all weather conditions. Collection of manure functions on the same principle as the rest of the buildings. Animals stand on slotted floors through which manure is washed out to the concrete reservoirs (Figure 7). These floor grids are made of PVC in the nursery department where animals are smaller, while they are made of concrete in other sections where the animals weigh more. What differs from building to building is the dimensions of the reservoirs and their positioning, which are determined by stall size. The manure is mixed with water in the cleaning process; the resulting mass is in liquid form and transported through a sewage pipeline in the direction of the biogas station. The leveling of the entire system was carefully calculated to enable gravitational flow of the waste. Pumps were installed only when no other solutions were available.

Figure 7.

Collection of manure in concrete reservoirs in fattening buildings.

Overall, the pig farm (Figure 8) needs the following buildings to function:

Figure 8.

New buildings in the pig farm and saplings planted in the open spaces.

- Buildings for animals (different types for piglets and fully grown animals).

- Food silos.

- Roads.

- Fences and gates.

- Disinfection barriers.

- Sewage systems (manure reservoirs, piping, pumps, …).

Since pig manure is collected in liquid form, the option to position the pig farm further from the biogas facility became available. Therefore, special attention was paid to the length and cost of the sewage system connecting these structures to the biogas structures to the complex. The distance between buildings was also dictated by fire safety regulations and the sun and air conditions.

These structures are highly dependent on technology.

3.2. Biogas Station and Hot Water System

The purpose of a biogas station is to collect all of the manure produced by the animals on the farm on a daily basis, simultaneously eliminating odor to reduce the impact the waste might have on settlements located in the vicinity of the farm. Concurrently, the plant produces its own electricity and thermal energy to power the functions of the farm itself.

Electrical and thermal energy are produced by burning biogas, which is produced through the anaerobic process of the digestion of energy from raw materials. The biomass is produced mainly via the organic waste produced during the process of cattle fattening, from silage and other available secondary sources like biomass attained during production in the food industry, e.g., sugar beet steaks, brewery dregs, etc. However, the main goal remains the production of electricity and its use on the site, as well as its dispersion through the distribution network. The obtained thermal energy (a by-product) of the process is used for the heating requirements of the farm facilities, while future activities might implement the utilization of heat for the dehydration of fruits, herbs, or other plants to expand the field of productivity of the farm.

Biogas, as a product of anaerobic digestion of biomass, is burned in gas engines.

The technology that is involved in producing electricity in biogas stations inevitably results in the production of heat. This energy presents a problem for the environment when it needs to be released, if the design does not incorporate methods for its further use. The capacity of this heat is 1.5 MW, from which about 200 kW is expended for the cooling purposes of the cogeneration plant and 200 kW for the heating of the digester. The rest of this heat energy is repurposed for other uses on the farm, in this case, for the heating of hog and broiler farms and the office building as well. The maximum amount of heat that can be taken from the cogeneration unit for farm purposes is 1161 kW, just under the projected farm requirements of 1300 kW. The simultaneous consumption is 70%, so the actual requirement is 910 kW. This means that additional heat from plant production the is used for the necessary heating of the farm facilities. The plant provides enough energy for these processes through its by-products. Therefore, the farm incurs no further costs to obtain heating for the buildings, and through this design solution the resulting unwanted product (heat) is used to reduce economic expenses.

The main product of fermentation is biogas with a methane content between 50 and 75%. The biogas station represents a complex of units within a farm system and consists of

- Mixer pit.

- Pump station.

- Digester, R = 27 m, capacity 480 m3 of biogas—two buildings.

- IST reservoir for manure.

- CHP cogenerating plant (heat energy salvage process).

- Separator (2 units).

- Collection pit.

- Reservoir for liquid residue from separator r = 36m.

- Electric power substation.

- Plateau for solid residue from separator.

- Plateau for temporary storage of remains.

The complex and its functions depend highly on technology and, above all, software solutions. The whole production process is automated and can be managed long distance. There are several companies in the EU that are engaged in this product placement such as LIPP (Tannhausen, Germany), Rota (Italy), and Natech (Austria). In this case the implemented software is LIPP, Germany.

It is hard to evaluate what section is the “heart” of the biogas station. Every single part is important with a role to play in the process of producing electricity. Unplanned maintenance is costly and wasteful, greatly affecting the entire production process. In addition to the architecture and constructed elements of the facilities, as well as the mechanical elements, the technologies of the process have the most important role. The selection of technology (the manufacturer) is the first element. While the key elements and landmarks of biogas, methane gas, and electricity production are relatively similar, not every technological approach provides the same results. The selection of technology determines the architecture and make-up of the surrounding buildings as a support system of the technological process. In this case, Lipp technology was used; the main contractor was Port Express Ltd.; and the project documentation was provided by JP Zavod za urbanizam Šid (the Public Urban Planning Enterprise in Šid).

Methane gas has been incorporated into digesters as part of the process of the digestion of raw material since 2019. Manure makes up the largest portion of this mass but is not the only substance that can produce biogas. Manure is the targeted component since its processing relieves the farm of waste, odor, and a negative environmental impact. Furthermore, there is no need for lagoons for manure storage and the need for maintenance is eliminated. To enable gas production during periods of animal rotation and pauses in the function of animal housing units, the design included reservoirs and plateaus that hold certain calculated amounts of manure mass collected on the functional days. These are enclosed concrete reservoirs without odor and a negative effect on the environment. Furthermore, the technological processes include corn silage as a raw material for the fermenters. On days when manure production is on pause, silage takes up a larger portion of the raw material. Corn silage is a part of production for cattle farms and is stored in trench silos. Depending on the raw material quality, the biogas plant needs 60 t of material daily. The combination of different waste materials is a specific technological process on its own. An important parameter is the inclusion of solid mass in the waste. With cattle manure, it is 18%, hog manure 3–5% (since it is mixed with water), and 34% in the case of broiler manure.

The designed capacity of this biogas station is 1 MW, that is, 24 MW per day, or to be exact 23.538 kW. This gives a maximum capacity production of 715.950 kW per month. If this is compared to the monthly production of the case study’s biogas station (Table 1), it is evident that production on a monthly basis is close to maximum. If daily production is taken into consideration, then most days are close to maximum, only 2 days show weaker production levels, and there are 14 days with the production of electricity above maximum capacity. Although the biogas station has a certain capacity included in its design, it is not expected to reach maximum values on a daily basis. Expected monthly production here would be 682.650 kW which means that this facility functions very well and at an above average level.

Table 1.

Productivity of this case study biogas station according to VD Buka company which has taken care of biogas and electricity production for January 2023 field measurements.

The energy potential for the different types of waste materials that can be utilized in biogas production is largely dependent on the efficiency of the digestion process and the energy conversion technology implemented. Regarding the example of the biogas station in Novo Orahovo, the waste material substrate mixture consists of approximately 25% cattle manure, 30% pig slurry, 2% chicken manure, and 33% recirculate and other organic waste materials. The energy potential of particular waste materials [49] compared with the produced energy is demonstrated in Table 2, and the synergy of mixing three different animal manures is proven to be beneficial.

Table 2.

Comparison of biogas electricity production from various potential substrates.

Digesters are circular buildings of 27 m in diameter (Figure 9). To increase the durability of the digesters, the walls are made of Verinox on the inside (a stainless steel and galvanized surface), an insulation layer, aluminum foil, and corrugated sheet metal as the outer surface. The wall is solidified with additional construction at every 100 cm. The height of the walls is 7.5 m. These buildings have fabric roofing. The height of the fabric membrane part of the building varies, depending on the inner pressure and the amount of liberated biogas. The upper structure is anchored in waterproof reinforced concrete slabs. The slabs have dilatational splits to prevent brakes.

Figure 9.

Biogas station on site.

All pits, reservoirs, and plateaus are made of waterproof reinforced concrete. After the mass in the digesters is processed, it goes into the separators. Solid waste from the separator unit becomes a compost of sorts, without any odor, and is used to fertilize the surrounding agricultural land. The liquid waste is in fact cleared water with 2% solid matter. It is transported in the lagoons (reservoirs) and is used for irrigation.

Solid waste gained after separation produces favorable characteristics as a result of the digestion process, such as a reduction in emissions of unpleasant odors, predominantly the decomposition of short-chain organic acids, thus reducing the risk of leaf erosion; improvement in rheological properties (flow), resulting in a reduction in leaf fouling on forage plants; and improvement in the short-term effect of nitrogen due to the increased content of fast-acting nitrogen and destruction or inactivation of weed seeds and disease agents. The digestion process changes the carbon fractions where nutrients are contained, remaining preserved as a whole and becoming easier to decompose. Therefore, their availability for plants is better [48]. The investor is only using this solid waste for agricultural soil treatment which has thus far resulted in a satisfactory income at harvest. The liquid from the lagoons is added to regular existing irrigation. Additionally, this fertilizer can be used in organic food production.

It is evident that the biogas station provides numerous positive impacts, although it requires a large investment. This process can relieve a farm of all waste and odor on a daily basis and enables the utilization of all products and by-products of the operations without producing excess, and there are additional economic benefits. Furthermore, manure management issues are greatly reduced and the release of methane gas into the environment is greatly reduced, enabling the energetic sustainability of the farm, eliminating the need for manure lagoons and other waste storage which tend to be the main cause of water and soil pollution.

The implementation of a new hot water pipeline is planned for the diversion of hot water. Pre-insulated tubes have been purchased and installed in accordance with the requirements of the basic standard EN 13941:2012 [50], and the accompanying standards EN 253; EN 488 [51,52]. Pipes have been laid on a freely excavated surface in the soil, in a sand bed at a minimum thickness of 15 cm below and 15 cm above the pipe. The metal part of the pipe is welded and controlled according to EN 13941, as well as being strengthened with cold water pressure. After testing of the joints, the thermosetting joints are further implemented, which are watered with polyurethane on the spot. Thermo-couple joints are manufactured according to the requirements of the EN 489 [53] standard. In addition to the pipeline itself, a substation unit has also been put on the site near the biogas station. From this location, all pipelines are distributed throughout the farm complex.

Keeping in mind the demands of the investor that the supply is safe, and that the option of a cogeneration plant has been provided for work at reduced capacity, the project foresees the opportunity to install additional energy sources. The system, therefore, has been connected to five existing gas tanks that can take over if the need arises. The total liquid gas capacity is 12,350 L.

The biogas station can be considered the core of the overall sustainable farm design. In comparison to other aspects (architecture and technology design, smart urban planning, materials selection, etc.), the digestion units and rest of the station sections share the facilities that provide the biggest sustainability contribution to the design, providing a significant decrease in the negative impacts that a large capacity farm could have on its surrounding environment. Through the development of these facilities, pollution and manure can be extracted from the farm and turned into a beneficial aspect of production by managing manure and water for soil treatment and the provision of electric energy and hot water. Such positive effects have been recognized worldwide. A further step in the process has been to transform biogas into biomethane. Over the past decade, biomethane production has seen significant growth, with 2021 seeing the greatest increase in the number of biomethane plants [54]. It is also important to note that feedstock for the new biomethane plants over the last eight years has consisted mainly of agricultural residues, manure, and plant residues, meaning that facilities have reduced overall pollution, especially farm complexes [55]. Furthermore, the electrical energy being produced on the farm frees up the energy grid. Biomethane facilities include the Köckte plant in Germany, that has been in operation since 2013, or the facility in Liffré, France, that started production in 2015 producing large amounts of biomethane from pig and cattle slurry. The effective management of waste on farms, with the focus on manure, is seen as an important environmental issue that can be resolved with functional biogas plants on site. If a plant does not exist at a given farm site, the manure can be collected and sold to third parties.

Biogas plants are not only suitable for fattening farms but can be implemented in various aspects of animal-related production. One example is dairy production, where a similar system could easily function. Even farms on a smaller scale can utilize these systems in their functioning. Such examples can be seen on farms in Poland [56].

Biogas stations can play a crucial role in preserving the environment and can be viewed as the heart of ecological awareness, social awareness, and sustainability practices. In this case study, the functioning of this biogas plant relieves the farm from odor pollution and provides products for irrigation and fertilization as a by-product of waste. Furthermore, electrical energy is generated for the entirety of the farm while providing additional energy that can be sold for added income. Hot water is produced to heat the farm, while there is a reduction in heat into the atmosphere which positively impacts the surrounding ecosystems and clearly demonstrates the efficiency of this kind of farm system.

3.3. Office and Genetics Facility

Every farm must have offices for management and workers. Buildings like this have been planned within the case-study farm complex. They have been designed with the purpose of housing the administrative offices of the entire farm. The management section of the pig farm consists of general offices, the veterinarian office, a mud corridor, two locker rooms, sanitary rooms, a clean corridor, and a dining room. The facility is connected to the internal roadway within the parameters of the farm for pig fattening. The genetics center is a facility for artificial insemination. The building has been planned for the separation and storage of seeds for sow insemination. The construction of the building is massive. The brick walls are placed on a strip foundation. The roof is made of wood construction elements and covered with trapezoidal sheet metal. The facility has had electricity installed, a water supply, and sewerage, as well as installations for heating hot water from a biogas plant. Alternatively, the heating of the building is resolved with electric power.

Every farm strives to minimize its numbers in staff. With new feeding and cleaning technologies, it is possible to have a smaller staff for farm maintenance. Therefore, the facility housing offices is one of the smallest in the farm complex.

3.4. Installation Infrastructure for Electricity, Water, and Sewage

The water supply network will be connected to two wells with a capacity of 10 L/s. The required amount of water for all three newly built farms is 2.77 L/s, which can be provided by the wells designed. Every facility has a washing system. In addition to the necessary water supplies, every building is protected with fire safety structures that are spread out over the entire area of the farm. This hydrant network is connected to drilled wells. The capacity of the existing well is 10 L/s per well. The required amount of fire-extinguishing water is 10 L/s. The pressure on the grid should be such that the hydrant’s outlet provides a pressure of 2.5 bar. The external hydrant network is made of PEHD 100 water pipes for 10 bar pressure, and the minimum diameter is d = 110 mm.

The sewage system is very important for the sustainability of the farm since the collected manure provides for a great amount of raw material for the functions of the biogas facility. On the other hand, this material can be problematic if not used in further processes. Its storage represents a liability for the environment because it cannot be directly implemented on agricultural land as a fertilizer. It needs to undergo certain processes that take time (mixing), which leaves a problem of storage space and treatment. With a biogas facility on site, all manure is collected and inserted into further closed-type processes with usable end-products (water and compost). This means that the system consists of numerous pipelines, reservoirs, and pumps for liquid manure (pigs) and concrete plateaus for temporary storage of consistent manure (chicken and cattle). Consistent manure is transported with adequate mechanization. The amount of liquid manure from the pig farm is 62 m3 per day. This mass is drained by corrugated sewage pipes to the biogas plant, with two tanks designed for storage if the biogas plant is not functioning (on occasions of regular repairs or other problems that need to be addressed). The process in the power plant tends to separate mass into liquids and consistent parts. Purified water from the biogas plant is directed to four newly designed earth lagoons and is used for irrigation of the surrounding agricultural land. The entire system is designed with gravitation flow wherever this type of implementation is possible; pumps are only installed where their use cannot be avoided. The functions of electrical installations are enabled with a new substation (MBTS-1P, 20/0.4 kV), equipped with a 400 kVA transformer. The substation is divided in two sections—one that distributes new electrical power throughout the farm complex and a second that is intended to put the remaining electrical power into the settlement grid (sale of electric power as an additional income for the farm). The spare power supply is provided by a diesel power generator with a power of 180 kVA. All existing facilities, except for irrigation, are connected to the backup power supply. In the substation, it is necessary to install the NN 4-pack outlet cabinet cable copies. The installation of a lightning rod is planned to protect the entire farm complex. The clamps should be mounted on the pipe pillars of the concrete foundation, that is, on the structural pillars of the buildings.

3.5. Traffic Infrastructure and Communication Corridors Between Buildings

The design incorporated new roads within the complex, in order to achieve improved functionality within each farm individually as well as between the farms.

Construction is planned on 3803.20 m2 of reinforced concrete roads and 1668.78 m2 of reinforced concrete plateaus in the first phase and 726.26 m2 of roads and 1668.78 m2 of plateaus in the second phase within the cattle farm. In addition to concrete roads and plateaus, the construction of 410 m2 of gravel roads is planned which can serve as an alternative route.

Within the chicken farm, the construction of an internal roadway is planned at 351.45 m2.

Within the pig farm, concrete roads are planned to take up 2131 m2 in order to connect three newly designed buildings with the existing roadway within the farm.

The reinforced concrete road construction consists of 18 cm concrete slab, concrete class C25/30, reinforced with steel nets Q188, and with dilations at 3.0 m distance. Below the construction, there is 15 cm of cemented sand and 20 cm of gravel.

3.6. Lagoons for the Storage of Liquid Manure and Purified Water from a Biogas Plant

Additional construction is planned for four facilities for the collection of purified water from the biogas plant and one facility for a water catcher from atmospheric rainfall. All facilities are circular in shape, with a diameter of 30 m and with depth of 4 m.

The design incorporated two lagoons. The lagoons have maximum dimensions of 100 × 20 m and a depth of 3.00 m with a maximum volume of 6000 m3.

All lagoons are built with a 3.00 m deep excavation, with sloping sides. The floor and walls of the lagoon are formed by pouring the soil layer and by placing geotextiles and HDPE foils on the soil to prevent water penetration. The walls have an inclination of 67°.

Purified water is fed directly from the biogas power plant to the lagoon using a pump.

All segments of the design are built on site.

4. Further Remarks on Architecture and Aspects Regarding Urbanization

- From the perspective of architecture, each typology of building utilizes as many sustainable solutions as are available within their scope. The various solutions can be divided into four categories. design solutions.

- Selection of materials.

- Technological solutions.

- Landscaping.

The architecture of farms has never been considered to inspire grand and thought-provoking designs. This fact remains true if we examine this architectural approach through its classical definition. These buildings do not require high-end materials to affect their aesthetics. Their primary role is to serve a purpose, which is to provide sustainable farming solutions. However, it is not outside the realm of possibility to attempt to make these structures more visually pleasing in the future. It could be suggested that local materials be taken into consideration for construction, decreasing the cost of transport and emissions levels. The same material selection driven by functional needs and local availability is made in other agricultural building types and productions as well [7].

In terms of construction, it can be said that these facilities are highly demanding with necessary spans, loads, and durability. The unique presentation of these buildings can be derived from this vantage point as well. Architectural language and the close connection of the farm buildings to the landscape can elevate the functional purposes of these buildings. Animal housing, the products of agriculture, and storage for machinery all need to be taken into consideration, when building a facility of this type and caliber. The selection of durable materials and a focus on reducing cost as well as pollution need to be taken into consideration. The selection of durable materials where needed, and low-cost ones in other places, contribute to building efficiency, low maintenance cost, reduction in pollution that can occur as a result of construction works for repairs, etc. Smart design could in some ways fulfill the gap between farm functionality and adjustments made for urban proximity. Although farms produce food that is sent to peoples’ tables, society still harbors a general dislike for farm complexes. They are seen as a source of pollution, noise, and the poor treatment of animals. By embracing multilayered sustainable designs that reflect a sense of local values, farm complexes can enhance local economic sustainability, rural tourism, and the general of rural life.

Some of the issues mentioned above were examined thoroughly in this case study. This resulted in special care for the surrounding environment and leaving existing flora on the location (tree lines planted in the past). These tree lines add a lot to the general aesthetic of the complex and its landscaping. The fact that these old tree lines were left untouched reflects the positive aspects of this type of farm management in terms of the environment and sustainability. It is thought that maintaining older trees is low in labor and cost effectiveness. However, this “small” gesture of conservation demonstrates a big change in the idea of how farms should function and how they can contribute to the environment without depleting it. It exemplifies how sustainable thinking can reach into the past and protect the already existing flora and fauna while preserving and sustaining the environment for the future. New trees can be planted between buildings, providing shade in the present and contributing to the anticipation of fruit in the future. The planted trees are a domestic cherry breed which provides a sense of genius loci, promoting local production and aiding in making better and stronger bonds with local fruit producers. This farm could have additional profit from fruit distribution, while the environment can benefit too. Some ideas for further development of the farm include fruit treatment facilities, dehydration facilities, and cool storages which will incorporate more green surfaces and trees in the open areas within the complex. Next to the animal housing, the empty surfaces are covered with cultivated grass and conifer trees. The landscape provides a visual representation of the great care taken for the design and atmosphere of this sustainable farm. Large complexes of this nature tend to focus more on function than on aesthetic, with the general focus being production on a large scale and the focal point being meat production and profit—not the aesthetics of the facility.

However, awareness of the landscaping and aesthetics of a facility is of great importance in times when farm complexes are receiving ever-increasing criticism in terms of the way they function. When sustainability and environmental impact are seen as an important aspect of the design of the free surfaces and agricultural facets of every farm, the natural consequence is that the landscaping is also taken into consideration as part of the overall design.

An important positive impact on the environment requires a large investment, but revenue and positive economic benefits also have to be provided. There is evidence that farmers and farms are willing to invest in sustainable land management practices that follow their socio-cultural contexts, and this could have economic benefits and positive environmental effects at the same time [54].

The working zone was in existence at the location of this project within the current municipal plan. The allocation of a new plot of land that would be suitable for greater farm capacities could prove to be difficult, and furthermore it would imply a dislocation from the surrounding arable land. As mentioned previously, it can be difficult to convert arable land into land allocated for construction in Serbia. Even if the functions are deemed suitable, it is a costly process and requires a greater overall investment. Expansion of the capacities of already existing farms has to be taken into careful consideration as even this can prove to be a complicated process. The decision to use an already existing farm in Novo Orahovo was based on logic, as the farm already had functional buildings and livestock available. There was an existing awareness that the quality of life in the neighboring village should not be encroached upon, and the facility already contained concepts for urbanization and the implementation of a biogas plant. The plant provided the opportunity to eliminate odor and pollution, allowing the farm to continue to function in close range of the settlement. The requirements of the plant mean that manure is cleaned daily except for in the poultry facilities. This eliminates the main point of contention between general society and the business of agriculture. These societal effects are a constant topic of discussion. The effects that farms have on their surroundings are frequently a point of contention. The architecture of biogas stations is predefined by the equipment manufacturing design, but architecture has many functions in addition to that which can be observed visually. The technical and raw presentation of a plant is not without its own expressiveness. The plant can be seen as providing a new depth to the design of a farm facility, it represents the synchronization of various factors that allow it to work as a functioning whole. The facility described over the course of this study will play an important role in the preservation of the surrounding ecosystems, the preservation of social connections between the settlement and the farm, and the recipients of the products provided. The technical aspects and equipment of the facility are essentially the core of providing recycling for high waste production and savings in energy consumption, while providing manure for fertilization and transport.

Another important aspect that farms need to take into consideration is the quality of life that is provided for the animals inhabiting the complex. This is an “obstacle” that can be overcome by creating appropriate floor plans and adjusting technologies to accommodate quality of life, giving special consideration to feeding, cleaning, and climate, etc. In this case study, solutions for these issues were provided with the help of natural processes—ventilation, lighting, and animal participation in cleaning processes—through architectural design.

The floor plans of this farm demonstrate a strong understanding of the life cycle of an animal, its day-to-day needs, behavior, climate control needs, etc., while simultaneously maintaining the ease and efficiency in the tasks of the workers. For example, the fencing systems provide various solutions for veterinary access to the animals, without the added complication of having to move animals around within the facility. An understanding of the animal provides solutions that could be seen in the cattle pen; this type of animal is not sensitive to low temperatures, thereby eliminating the need for heating in their enclosures. As with any living being, fresh air and good air circulation are vital for healthy development, and each housing unit took this into consideration and provided adequate solutions, using natural air flow to provide better ventilation. Even the facade of the farms was considered, and the colors used in the buildings utilized natural shades, greens, and whites reflecting the scenery surrounding the location of the farm.

The buildings for the pigs varied in multiple aspects. The pig enclosure was divided up to accommodate the different phases of the pig life cycle, greatly improving the quality of life of the animals (less room for conflict and injury). Younger animals were provided with safer surroundings, as they would face far more danger were they in spaces where there were various age groups of pigs. The ensured safety of the pigs also provides greater economic gain for the facility itself. The climatic surroundings of the pigs were also adjusted according to the phase of their development. Natural air flow was provided, with the proper placement of the roof, inlets, and special opening controls to ensure a healthy indoor environment. The buildings’ main purpose is functionality and to provide a controlled climate, the outer appearance also contributes to the general aesthetic of the farm. The white exterior contrasts with the surrounding greenery of nature, while remaining natural and in symbiosis with its environment. The silos provide a visual contrast and act as towers to animal housing units, providing a point of interest to the eye. The form of the farm buildings is separate from their function, and that is what separates them from other architecture. This is also true for the layout of the farm facility. There is diversity in the types of farm buildings each differing due to its function, creating a unique urban composition, providing the possibilities for breakthroughs in design, landscaping, and the field of socioeconomics. One example is a round barn found in New Prague, Minnesota, which was constructed on the basis of labor-saving ideas and ended up providing an unusual form in its landscape and a unique expression of architectural ideas [35].

5. Conclusions and Further Development Possibilities

By examining the various aspects of the development of a sustainable farm facility, this case study has shown that development and on-site design differs from the idea of the traditional farm in some capacity, and many standards of farm organization were redesigned; great steps were made to incorporate sustainable farm practices into the functions of a farm observed in the Republic of Serbia. Benefits were created for the environment and the investor, providing a great incentive for these types of practices to continue functioning in the future.

On-site functioning of this farm complex is result of complex planning and design:

- The existing farm location borders a village. Changes and expansion of the facility meant that the amount and manure and factors like odor and pollution had to be taken into consideration. Farms are seldom found so close to a settlement due to new regulations, creating another obstacle to overcome in terms of design. Expansion of the farm was made more difficult due to this proximity and faced challenges in adhering to new regulations.

- The biogas plant found in this location enabled the daily processing of manure, resolving the issue of finding space for the waste. Fermented manure has no odor, and the separation of its mass provides liquid and solid residue, which can be used for irrigation and fertilization of the arable land and orchards in the vicinity, providing further incentive and benefits for investors.

- The exact number of animals on the farm was calculated and accounted for, the numbers being vital for the purposes of the biogas plant. New animal housing was constructed along with the utilization of older structures. Cattle were brought in to maximize the functions of the biogas plant. This type of diversity is rarely seen on modern mass-production farms.

- The biogas plant produces electricity and hot water for the heating requirements on the farm. The on-site electricity production is designed to target ideal production capacities, providing an even greater benefit to investors. Excess heat from the power plant is also accounted for, which is unique to this project as this is not part of most biogas plant designs.

- A near-zero-waste system and energy independence are consistent with sustainable directives, relieving the main energy grid while protecting the ecosystem.

The planning of the buildings themselves provided its own benefits; the processes of ventilation, lighting, and the cleaning of buildings are performed as naturally as possible, which is enabled by carefully considered floor plans, architectural form, and mutual disposition of building elements. The stress is on construction, raw materials, and function in cattle housing buildings and strives to simplify forms in pig housing units. Simple and natural color selection like white let nature, tree lines, and free space come to the forefront. In terms of function, the buildings for animal housing addressed many issues, solving them in ways akin to the practices of top farms worldwide, even making some improvements in comparison to standard solutions (fencing, simplified accessibility for veterinarians, easy animal movement or separation…).

All construction within the parts of the buildings was deliberately performed with pre-stressed and reinforced concrete. Through time and experience in the field of designing animal housing buildings in farms, concrete has shown to be most resistant to ammonia, animal impact, and rodents. The durability of buildings saves economic resources for other (greener) investments that can improve the self-sufficiency and sustainability of the farm. Ideas for further development can be found in the area of new materials and different architectural language.

Nevertheless, the farm complex in question proposes many solutions that contribute to the goals of sustainable development. Resources and energy make a complete circle in their processes, using crops from the farm’s own land to feed and treat three different species of animals in one complex, using waste to produce electric power and repurposing excesses of heat and water into the functioning of the farm, and using the conversion of waste to fertilizer and to water for irrigation which is then reintroduced to the land to support the growth of crops. No excess waste is left on the farm, and all functions of the complex are self-sufficient. Farming must develop in accordance with sustainable principles adopted in every element of its functioning. Architecture and design can provide some of the necessary solutions. It begins with smart planning being performed before investments are made. The key to sustainable farming is a deep understanding of the processes and functions needed to run a farm and a knowledge of the surrounding environment. This knowledge can provide the innovations needed for not only a working farm system but a better functioning society. However, it all starts with the intent for improvement and care for our surroundings and the environment.

Author Contributions