Abstract

The overuse of chemical fertilizers can result in elevated concentrations of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) in soil, potentially impacting rock weathering processes and carbon flux in karst regions. This study analyzed the impacts of chicken dung fertilizer and compound fertilizer on the weathering of carbonate rocks within the water-soil-rock system, yielding the following results: (1) The peak concentrations of various ions in the compound fertilizer system (Ca2+: 36.8 mg/L, Mg2+: 4.3 mg/L, N: 284.2 mg/L, P: 920.6 mg/L, HCO3−: 16,170.3 mg/L) were generally superior to those in the chicken manure fertilizer system (15.4 mg/L, 1.9 mg/L, 306.9 mg/L, 27.9 mg/L, and 4576.5 mg/L, respectively), with a difference of approximately fourfold between the two systems; (2) Nitric acid generated by nitrification in fertilizers and phosphoric acid in compound fertilizers modify the chemical equilibrium of rock weathering, enhance dissolution, and influence the dynamics of HCO3−; (3) Nitrogen and phosphorus in compound fertilizers are predominantly eliminated through ion exchange and adsorption. Calcium-phosphate precipitates are generated on the limestone surface within the 20 cm soil column, exhibiting a greater degree of weathering compared to the chicken manure fertilizer treatment; (4) analyses utilizing XRD, FT-IR, XPS, SEM, and additional approaches verified that substantial weathering and surface precipitation transpired on limestone throughout the 20 cm compound fertilizer column.

1. Introduction

Carbonate rocks are extensively found in Southwest China (Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Guangxi, Tibet), constituting the most characteristic region for karst landform formation in the country. Exposed carbonate rocks constitute approximately 53% of the total area of Guizhou Province [1]. The limestone soils resulting from the weathering of carbonate rock have supported essential agricultural and forested regions in Southwest China, establishing it as a significant production zone for crops like rice and rapeseed. Nonetheless, the soils in this region are intrinsically defined by shallow layers and inadequate water and nutrient retention capabilities. To satisfy developmental requirements, karst terrain has historically endured extensive agricultural exploitation, with fertilizer application rates significantly surpassing those of other areas [2,3]. From 2000 to 2018, the worldwide usage of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers rose by 33.1% and 18.4%, respectively, to satisfy the escalating food demand. In that timeframe, China represented over 30% of global fertilizer consumption, establishing itself as the foremost fertilizer consumer worldwide [4]. Excessive fertilizer application has resulted in nitrogen and phosphorus pollutant emissions from agricultural sources significantly surpassing those from industrial and household pollutants [5]. Soil, as the second largest carbon reservoir on Earth, is essential in regulating the global climate [6]. Overapplication of fertilizer can lead to soil compaction, alter pH balance, diminish microbial diversity and enzyme activity, and adversely affect soil carbon sequestration [7,8]. The karst regions of Southwest China are ecologically vulnerable, experiencing significant soil erosion and rocky desertification [9]. The weathering of carbonate rock can sequester CO2, creating a substantial carbon sink [10,11]. Calcium ions (Ca2+) emitted from carbonate rocks are essential in regulating soil microbial diversity and facilitating soil carbon sequestration [12]. The lithosphere constitutes Earth’s most extensive carbon store, with karst activities contributing around (1.1–6.08) × 108 t C yearly, representing 15–30% of the global missing carbon sink and significantly influencing the global carbon cycle [13]. Karst processes consume atmospheric CO2, dissolve carbonate rocks, and the resultant dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) enters the hydrosphere and biosphere [14]. Carbonate rocks are very prevalent in southern China, encompassing an area of over 1 million square kilometers, with an estimated carbon storage capacity of up to 6.1 × 1016 tons. This region serves as a vital global carbon storage and significantly impacts the global carbon cycle through continuous karst processes [15].

Historically, carbonate weathering was considered to be predominantly influenced by carbonic acid. Recent studies demonstrate that exogenous acids, such as sulfuric and nitric acids from anthropogenic activities, considerably contribute to the dissolving process, hence elevating HCO3− concentrations in aquatic systems and affecting the carbon sink effect [16,17]. A study by Shi Yu on the upper and middle reaches of the Xijiang River revealed that exogenous acids from industrial and agricultural activities significantly contribute to the karst carbon sink process within the watershed [18]. Agricultural fertilization constitutes a significant source of these exogenous acids. A study indicated that the use of nitrogen fertilizer diminished the percentage of carbonate rock breakdown by carbonic acid by roughly 10% [19]. In contrast, Semhi’s studies in the karst region of southern France determined that nitric acid originating from nitrogen fertilizers might enhance the dissolution of carbonate rock by 6% [20]. Moreover, the enrichment of nitrogen and phosphorus might expedite microbial proliferation and augment enzyme activity, potentially resulting in heightened loss of soil organic carbon [21]. Phosphate fertilizers can enhance calcite dissolution by adsorbing onto mineral surfaces and facilitating subsequent precipitation [22]. Moreover, fertilizer affects the forms and movement of phosphorus in the soil. When the surface soil becomes saturated with phosphorus, it may percolate to deeper strata, potentially leading to acidification and heightened risk of inorganic phosphorus loss. The generated acidic compounds can also engage in the weathering of carbonate rocks [23,24].

Contemporary study primarily examines the effects of fertilizers on soil characteristics. Research on the interplay between nitrogen/phosphorus and carbonate rocks, along with their consequent impact on karst carbon sink fluxes, is still rather limited. As China’s population has increased, the poultry farming sector has experienced significant expansion [25], generating around 1 million tons of chicken excrement per day. The nitrogen in this manure is present as ammonium nitrogen and urea nitrogen [26,27]. Current treatment methods for livestock and poultry manure mostly encompass composting, land application, thermal treatment, and anaerobic digestion [28], with composting and land application being the predominant methods employed in China [29]. Statistics indicate that compound fertilizers comprise 44.5% of China’s fertilizer consumption structure, rendering them the predominant group by share. Nitrogen and phosphorus primarily exist in forms such as ammonium nitrogen, nitrate nitrogen, monoammonium phosphate, and diammonium phosphate. In China, compound fertilizers and chicken dung are the two predominant fertilizers; however, they demonstrate considerable disparities in nitrogen and phosphorus concentration. Their environmental impact consists of nitrogen in fertilizers being transformed into nitrate by nitrification and phosphorus forming phosphates. These compounds can interact with carbonate rocks, resulting in the generation of easily hydrolyzable calcium nitrate, while phosphate may precipitate as hydroxyapatite. This work used chicken dung and compound fertilizer as representative nutrition sources, performing laboratory kinetic experiments to observe changes in hydrochemical parameters, alongside characterization techniques like XRD, EDS, XPS, and FT-IR. The objective is to examine their influence on the karst carbon sink, establishing a scientific foundation for judicious fertilization measures, augmenting carbon sequestration potential, and preserving the integrity of the soil carbon reservoir.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

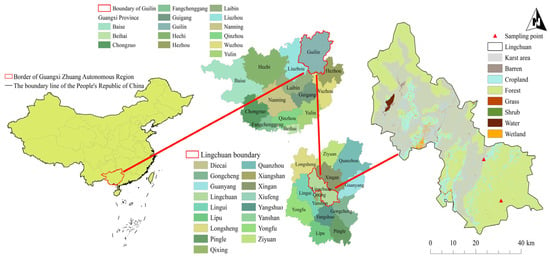

The research region, depicted in Figure 1 (geographical coordinates: 25°10′11″–25°12′30″ N, 110°30′00″–110°33′45″ E), is situated in Maocun Village, Chaotian Township, Lingchuan County, Guilin City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. It is roughly 30 km from the main core of Guilin. The drainage area of the Maocun-Chaotian River basin is roughly 476.24 km2. The karst area and non-karst area inside the basin encompass 172.81 km2 and 303.43 km2, respectively. The research area exhibits characteristic karst landforms, including peak cluster depressions and peak cluster valleys, in addition to non-karst hilly topography.

Figure 1.

The location of the research area and sampling points.

2.2. Materials and Preparations

Samples of dense limestone and surface limestone soil were gathered from Maocun Village, Chaotian Township, Lingchuan County, Guilin City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Soil sampling was conducted utilizing the diagonal approach, with samples collected from three depth intervals (10–20 cm, 20–30 cm, and 30–40 cm) and subsequently amalgamated. The rock samples were rinsed with deionized water and air-dried in conjunction with the soil. Sample preparation adhered to the guidelines of the Geochemical Evaluation of Land Quality standard (DZ/T 0295–2016) [30]. Impurities were eliminated, and the materials were pulverized, sifted, and divided to procure test specimens, which were thereafter stored in a desiccator. Limestone slabs were fabricated utilizing an angle grinder. The experiment utilized naturally air-dried chicken dung as organic fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O: 1.6–1.2–0.7%) and Lop Nur compound fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O: 17–20.5–21%) as industrial fertilizer. All materials were readied for the ensuing dynamic soil column experiments.

2.3. Characterization and Analysis Methods of Limestone

The limestone slices were collected, classified, and subsequently dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h following the trials. A little quantity of each sample was thereafter extracted and pulverized in a ceramic mortar for ensuing microscopic characterization examinations. The test results were evaluated utilizing MDI JADE 6 software and Origin 2023. The crystal structure, phase composition, and internal structure of the materials were examined utilizing an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, PANalytical B.V., X’Pert3 Power, Almelo, The Netherlands). The instrument’s operational characteristics were: CuKα radiation (45 kV, 40 mA), a scanning rate of 10°/min, and a scanning range from 10° to 90° [31]. Analytical reagent-grade (99.9%) KBr from Xilong Scientific was utilized as the infrared absorption backdrop. The sample and KBr were combined in an agate mortar at a ratio of 1:100, subsequently undergoing meticulous grinding and mixing. A suitable quantity of the mixture was placed into a tablet pressing mold and compressed at a pressure of 20 MPa for 10–20 s using a tablet press to produce a translucent thin sheet. A Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Nicolet™, Waltham, MA, USA) was utilized to examine the structural modifications of the functional groups inside the material. The specifications and technical parameters of the utilized Fourier transform infrared spectrometer were iS10, with a scanning range established at 4000–400 cm−1 [32]. A monochromatic Al Kα (1486.6 eV) X-ray source was employed in a Thermo Fisher K-Alpha X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, Thermo Fisher, K-Alpha, USA) to irradiate the material. This irradiation stimulated the emission of inner-shell or valence electrons from atoms or molecules. The kinetic energy of the photoelectrons was measured to acquire information on the sample’s elemental composition and the binding energies of its chemical bonds. For full-spectrum acquisition, the pass energy was established at 100 eV with a step size of 1 eV; for narrow-spectrum acquisition, the pass energy was set to 20 eV with a step size of 0.1 eV. The vacuum level for the experiment was 10−19 mbar, and all recorded sample spectra were calibrated utilizing the standard contamination peak of C 1s (binding energy, BE = 284.8 eV) [33]. The surface micromorphology of limestone was examined utilizing a scanning electron microscope (SEM, GeminiSEM 300, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). An energy dispersive spectrometer (model: Ultim Max, Oxford Instruments plc, Abingdon, United Kingdom) was integrated with the SEM to examine the elemental composition. The test parameters were established as follows: an accelerating voltage of 1.5 kV, a current of 5 nA, and a working distance (WD) of roughly 10 mm. Before testing, the sample was secured on the sample stage with conductive tape, and loose surface powder was removed using an air gun. A gold-spraying treatment was administered to the sample’s surface for 30 s to improve its conductivity. Upon positioning the sample in the sample chamber, the accelerating voltage, brightness, and magnification were calibrated. The auto-focus mode was employed to eradicate image blurriness, resulting in the acquisition of clean images and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) spectral data in both rapid and slow scanning modes [34].

2.4. Experimental Setup and Methods

This experiment involves a dynamic dissolution research with two distinct soil layer thicknesses and types of fertilizer. The soil utilized was limestone soil obtained from a 20–40 cm weathering profile of carbonate rocks in a karst area. The experimental design is encapsulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Names and Conditions of Experimental Groups.

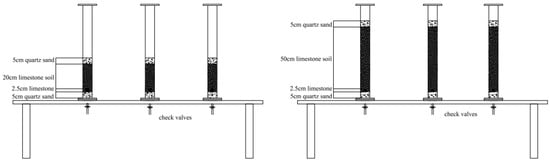

Figure 2 illustrates a schematic representation of the experimental configuration. The experiment utilized a PVC column measuring 75 cm in height and 7.5 cm in inner diameter. Prior to the experiment, one group of columns was sequentially filled from top to bottom with the following materials: 5 cm of quartz sand, a 20 cm-thick soil sample (comprising calcareous soil mixed with various chemical fertilizers), limestone fragments (dimensions: 2 cm × 1 cm × 0.5 cm), an additional 5 cm of quartz sand, and circular qualitative filter paper. The remaining group of columns was filled similarly, with the calcareous soil layer measuring 50 cm in thickness. Solutions were consistently introduced into the dissolving columns, comprising chicken manure fertilizer solution (100 g of chicken manure dissolved in 1000 mL of water) and compound fertilizer solution (100 g of compound fertilizer dissolved in 1000 mL of water). In the initial 10 days (Days 0–10), a cumulative volume of 1000 mL of the designated fertilizer solution (chicken manure fertilizer solution for columns treated with chicken manure and compound fertilizer solution for columns treated with compound fertilizer) was incrementally administered to the respective fertilizer-amended soil columns, while 1000 mL of tap water was supplied to the control soil columns. Between Day 10 and Day 50, a cumulative volume of 4000 mL of tap water was incrementally introduced to each column.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the dynamic dissolution column experimental setup.

Leachate was collected at regular intervals, and its hydrochemical properties were analyzed. A water quality analyzer was employed to ascertain pH and electrical conductivity (EC); bicarbonate (HCO3−) was quantified utilizing an Aquanmerck bicarbonate titration kit. To ascertain cation concentrations (Ca2+, Mg2+) in aqueous solutions, standard curve solutions were formulated with gradients of 1 mg/L, 3 mg/L, 5 mg/L, 8 mg/L, and 10 mg/L utilizing 1000 μg/mL Ca and Mg standard solutions. An inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) was utilized, featuring a detection limit between 0.1 ng/mL and 1 ng/mL. The phosphorus (P) concentration in the solution was determined using the molybdenum blue colorimetric method using a TU-1810SPC UV-visible spectrophotometer (glass cuvette; single wavelength: λ = 700 nm; measurement accuracy: 0.1 mg/L). The detailed procedure was as follows: Two milliliters of the solution from the glass vial were pipetted into a 50 milliliter colorimetric tube and diluted to 25 milliliters; four milliliters of potassium persulfate solution were added, and the combination was subjected to autoclaving for digestion at high pressure for 60 min. Subsequent to digestion, ultra-pure water was incorporated to achieve a total volume of 50 mL, followed by the introduction of 1 mL of ascorbic acid solution and 2 mL of molybdate solution. The total nitrogen (TN) concentration in the solution was assessed utilizing the alkaline potassium persulfate method with a TU-1810SPC UV-visible spectrophotometer (quartz cuvette; dual wavelengths: λ = 220 nm and 275 nm; measurement accuracy: 0.1 mg/L). The procedural steps were: 1 mL of the solution from the glass vial was transferred into a 25 mL colorimetric tube and diluted to 10 mL; 5 mL of alkaline potassium persulfate solution was added, and the tube was subjected to autoclaving for digestion at high pressure for 60 min. Subsequent to digestion, 1 mL of 1:9 hydrochloric acid (HCl) was incorporated, and the total volume was adjusted to 25 mL using ultra-pure water.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrochemical Processes in Soil–Limestone Systems

3.1.1. Analysis of the Influence of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Concentrations on the Concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+

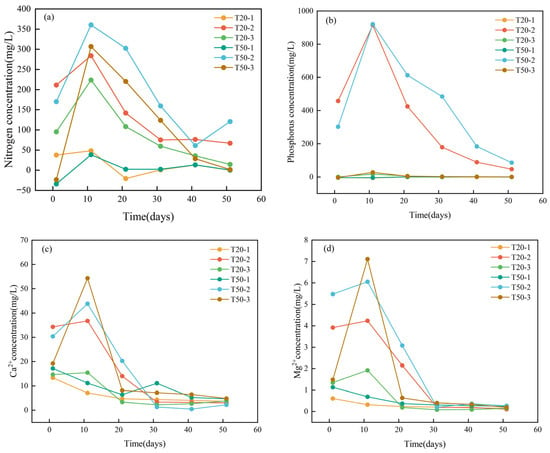

Figure 3a–d depict the fluctuations in concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, Ca2+, and Mg2+ in the leachate from various soil columns. The nitrogen concentration in the 50 cm soil column exceeded that of the 20 cm column, whereas the phosphorus concentration in the compound fertilizer column was markedly greater than in the chicken manure column, with maximum values of 920.6 mg/L and 27.9 mg/L, respectively—a disparity exceeding 30-fold. The disparity in nitrogen concentration between the two was quite minor. The amounts of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) peaked on the 10th day and thereafter declined as the frequency of tap water leaching episodes increased. In the compound fertilizer treatment, the nitrogen concentration increased with the application of the fertilizer solution, peaking on the 10th day, and thereafter declined throughout the clear water leaching phase. The maximum value of T50–2 was markedly greater than that of T20–2, and its concentration consistently exceeded that of T20–2 during the decline phase. This suggests that the augmentation of soil depth may facilitate the collection or retention of nitrogen and postpone its leaching process. In Column T50–2, the nitrogen content on the 50th day exhibited a marginal rise relative to that on the 40th day. The likely explanation for this is the increased soil content in this column: a portion of the nitrogen was adsorbed onto the surfaces of soil particles, and furthermore, the leachate did not completely permeate the soil layer. The two variables resulted in the desorption of nitrogen, which then entered the leachate in the later stage.

Figure 3.

The change in ion concentration in the exudate: (a) Nitrogen concentration, (b) Phosphorus concentration, (c) Ca2+, (d) Mg2+.

The variations in Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations exhibited a link with nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) levels. The concentrations of these two cations in the compound fertilizer columns exceeded those in the chicken manure fertilizer columns, peaking following the injection of fertilizer solution, followed by a slow decline. The disparities in Ca2+ and Mg2+ contents between the two fertilizer treatments in the 50 cm soil columns were minimal; however, the discrepancies were substantial in the 20 cm soil columns. The maximum concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the compound fertilizer columns were 36.8 mg/L and 4.3 mg/L, respectively, whereas in the chicken manure fertilizer columns, they were 15.4 mg/L and 1.9 mg/L, respectively, indicating about a twofold difference. The ion concentrations in the blank columns remained low due to the introduction of tap water. Significantly, in the 50 cm chicken manure fertilizer column (T50–3), the contents of Ca2+ and Mg2+ surged markedly during the initial application of chicken manure solution, then declined swiftly during tap water leaching. This phenomenon pertains to the substantial presence of nitrogen, particularly ammonia nitrogen, in deep soil and chicken dung, with nitrifying bacteria: subsequent to the initial fertilization, the ammonia nitrogen generated acidic compounds via nitrification. During the infiltration process, these acidic chemicals dissolved carbonate rocks, hence enhancing ion concentrations [35]:

NH4+ + 2O2 → NO3– + H2O + 2H+

NO2 + OH– → HNO3→H+ + NO3–

CaCO3 + HNO3 → Ca2+ + NO3– + HCO3–

HCO3– + H+ → H2O + CO2

The leaching of tap water steadily reduced nitrification, resulting in a corresponding decrease in the dissolution effect on carbonate rocks. Subsequent to the final water injection, the concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ across the six columns were comparable. This suggests that nitrogen and phosphorus in the chemical fertilizer contributed to the dissolving of limestone, resulting in elevated quantities of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the leachate, indicating the involvement of anthropogenic acids in carbonate weathering. This aligns with the research findings of Xie Yincai et al. [36]. A substantial quantity of phosphorus in the compound fertilizer was transformed into phosphate, which markedly enhanced the dissolving of lime soil and limestone. Consequently, the quantities of Ca2+ and Mg2+ produced by leaching exceeded those observed in the chicken dung fertilizer treatment. In the presence of compound fertilizer, the concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the leachate from the 20 cm lime soil layer were inferior to those from the 50 cm lime soil layer. The compound fertilizer likely contains a significant concentration of phosphate ions, which interact with Ca2+ in the soil and rock pieces to produce calcium hydrogen phosphate precipitates. The precipitates adhere to the rock surface, leading to a reduction in the concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+. This phenomenon necessitates additional characterization and validation.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Influence of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Concentrations on Water Chemical Parameters, Such as Inorganic Carbon

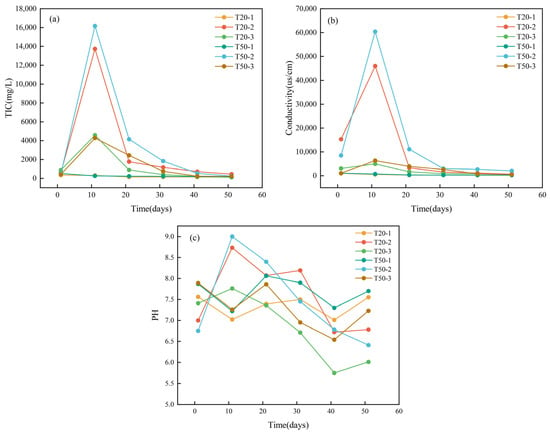

Figure 4a,b illustrate the variations in total alkalinity (HCO3− concentration) and electrical conductivity within the leachate. Their general fluctuation trend aligns with that of calcium and magnesium ions in the leachate illustrated in Figure 3a,b. From Day 0 to Day 10, a total of 1000 mL of fertilizer solution was administered into the experimental column, during which all aforementioned values exhibited an increasing trajectory, culminating in their maxima on Day 10. Between Day 10 and Day 50, a cumulative volume of 4000 mL of tap water was introduced into the experimental column, resulting in a progressive decline in each value until it approached that of the control column. In the blank column, a total of 5000 mL of tap water was administered from Day 0 to Day 50, resulting in consistently low readings. The maximum concentrations of phosphorus, total alkalinity (HCO3−), and electrical conductivity in the leachate from the compound fertilizer column were 920.6 mg/L, 16,170.3 mg/L, and 60,400 μs/cm, respectively; whereas the corresponding values for the chicken manure fertilizer column were 27.85 mg/L, 4576.5 mg/L, and 6390 μs/cm, respectively. The three characteristics of the compound fertilizer column were 33, 3.5, and 9.45 times greater than those of the chicken manure fertilizer column, respectively. This signifies that the hydrochemical characteristics of the water–soil–rock system under compound fertilizer conditions differed significantly from those under chicken manure fertilizer conditions.

Figure 4.

The change in ion concentration in the exudate: (a) total alkalinity (HCO3− concentration), (b) electrical conductivity, (c) pH.

This phenomena can be ascribed to the following factors: nitrogen and phosphorus in the compound fertilizer are transformed into nitrate and phosphate, which dissolve limestone, resulting in a rise in HCO3− concentration and electrical conductivity. Furthermore, carbonate and phosphate can react with H+, resulting in an alkaline solution [37]. Consequently, as illustrated in Figure 4c, the pH of the leachate escalated swiftly during the initial water injection. Nevertheless, when the frequency of water injections increased, the concentrations of phosphate and carbonate diminished, the dissolution effect on limestone lessened, and thus, all hydrochemical parameters declined correspondingly. The principal equations pertinent to this procedure are as follows [38,39]:

CO32– + H2PO4– → HCO3– + HPO42–

CO32– + H2NO3 → HCO3– + HNO3–

At the conclusion of the experiment, the pH values in the chicken manure fertilizer columns (T20–3 and T50–3) were markedly lower than their beginning values, likely due to H+ ions generated by the action of nitrifying bacteria in both the soil and the chicken dung. The H+ ions then interacted with CaCO3 in the limestone soil and rock fragments, resulting in elevated levels of HCO3− and Ca2+ in the leachate. Following several leaching events, the decrease in NH4+ and the diminished nitrification led to a marginal increase in pH. Conversely, the unaltered soil column, which was solely irrigated with tap water, had persistently low and stable values across all parameters over the experiment.

Nitrogen was recognized as the primary agent affecting hydrochemical alterations in the chicken manure columns, but phosphorus predominated the dissolving process in the compound fertilizer columns. The parameters recorded in the compound fertilizer columns were consistently several times greater than those in the chicken manure columns, suggesting that phosphorus possesses a superior capacity to enhance dissolution in the limestone soil–rock system compared to nitrogen. In conclusion, the application of compound fertilizer markedly elevates the concentration of inorganic carbon in the groundwater system, hence imposing a more significant detrimental impact on karst carbon sequestration.

3.1.3. Analysis of the Dissolution Rate of Limestone

Subsequent to the experiment, the limestone slices were extracted, rinsed with deionized water, and dried in an oven. Their post-experiment weights were recorded using an electronic balance with a precision of 0.0001 g. The dissolution rate in each column was determined by comparing the weights before and after the experiment using the formula Rd = (Wi − Wf)/2.7 (T × S), where Rd signifies the dissolution rate, Wi indicates the initial weight of the slice, Wf denotes the final weight post-experiment, T represents the experiment’s duration, and S is the surface area of the limestone slice (7 cm2). The specific gravity of limestone is 2.7, measured in g/cm3.

Table 2 displays the beginning and end weights of the limestone slices along with the associated dissolution rates throughout all six experimental columns.

Table 2.

Shows the weight and dissolution rate of limestone slabs in different experimental columns before and after the experiment.

Table 3 illustrates that the dissolving loss of limestone in the compound fertilizer columns (T20–2 and T50–2) exceeded that observed in the chicken manure columns (T20–3 and T50–3) and the control columns (T20–1 and T50–1). The dissolving rate of limestone was maximized under compound fertilizer treatment, signifying that the use of compound fertilizer promotes limestone dissolution and expedites the corrosion process. The data indicate that the degree of dissolution in the chicken manure columns did not significantly differ from that in the control columns, implying that chicken manure exerts no substantial influence on limestone dissolution. These results further illustrate that compound fertilizer has a more significant detrimental effect on karst carbon sequestration than chicken manure.

Table 3.

Chemical Composition of Limestone.

3.2. Morphological Characteristics of Limestone

3.2.1. XRD Analysis of Limestone

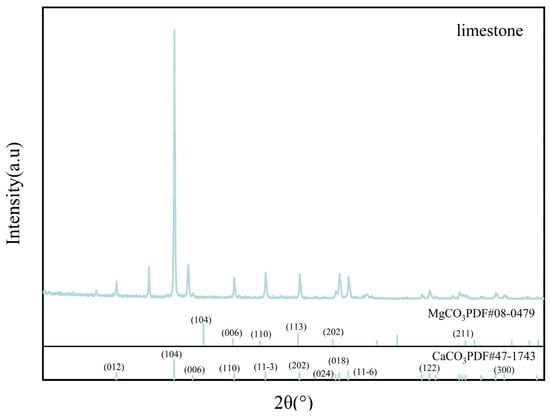

X-ray diffraction (XRD) utilizing MDI Jade6 software was applied to investigate the surface sediments of limestone and limestone soil prior to the experiment. Obtain the XRD reference spectrum. The findings (Figure 5 and Figure 6, and Table 3) demonstrate that the principal constituent of limestone is calcium carbonate, accompanied by a modest presence of magnesium carbonate, whereas limestone soil is chiefly comprised of silicon dioxide with trace levels of calcium carbonate.

Figure 5.

XRD pattern of the original limestone.

Figure 6.

XRD pattern of the original limestone soil.

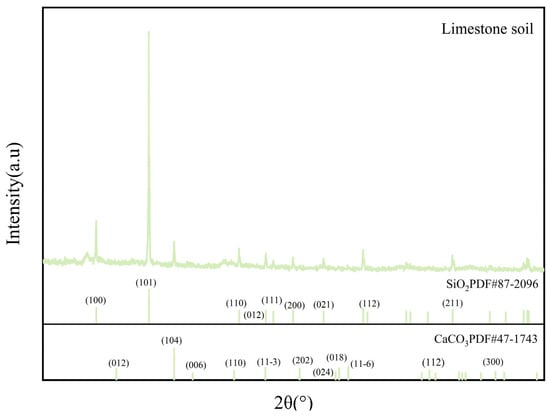

The surface deposits on the limestone post-experiment were investigated via X-ray diffraction (XRD), with the results depicted in Figure 7a,b. The limestone beneath both 20 cm and 50 cm soil conditions displayed predominant CaCO3 diffraction peaks. The strength of the CaCO3 peaks was markedly diminished in the slices treated with chicken dung and compound fertilizer relative to the control group. Within the identical soil column height, the CaCO3 concentrations in the compound fertilizer treatment group were inferior to those in the chicken manure group. In the slices treated with compound fertilizer, a sequence of diffraction peaks was detected at angles of 20.9° (020), 29.3° (021), 30.5° (221), and 34.2° (220), according to the usual reference pattern for CaHPO4 (PDF#09–0077). This signifies the deposition of dicalcium phosphate on the surface. The magnitude of these peaks was greater in the 50 cm soil column compared to the 20 cm column. Upon examining the XRD data using MDI Jade 6 software, no diffraction peaks of calcium nitrate were detected, demonstrating the absence of crystalline calcium nitrate formation on the limestone surface. This can be ascribed to the potent hydrolytic characteristics of nitrate and its facile leaching from the surface during various leaching processes, hence rendering it undetectable by XRD. Consequently, further verification utilizing spectroscopic techniques, including FTIR and XPS, is essential. The results indicate that Ca2+ leached from the limestone reacted with HPO42− from the compound fertilizer, resulting in the formation of CaHPO4 precipitate, which adhered to the rock surface. This observation aligns with the phenomena documented by Ren Chao, wherein phosphate generates Ca-P precipitates on the calcite surface [40]. Hydrochemical results indicated that the Ca2+ concentration in T50–2 exceeded that of T20–2; nevertheless, the distinctive CaHPO4 peaks in the XRD pattern of T50–2 were less pronounced, implying greater precipitate formation on the limestone surface in the 20 cm column. This can be ascribed to the elevated CaCO3 concentration in the 50 cm limestone soil, where phosphate was partially adsorbed by soil particles and did not completely permeate. This suggests that larger soil layers exert an inhibiting influence on the phosphate-augmented dissolution of carbonate rocks.

Figure 7.

X-ray diffraction pattern of limestone (a) 20 cm column experimental group, (b) 50 cm column experimental group, (c) Compound fertilizer column experimental group.

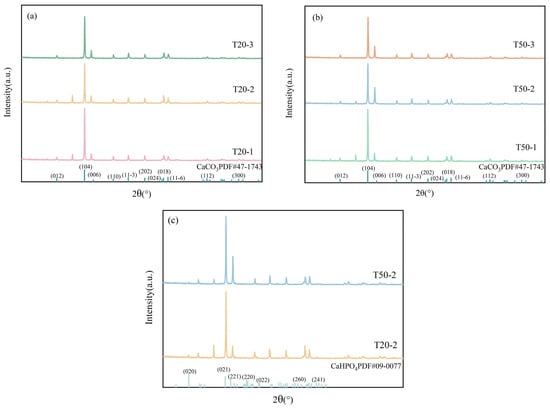

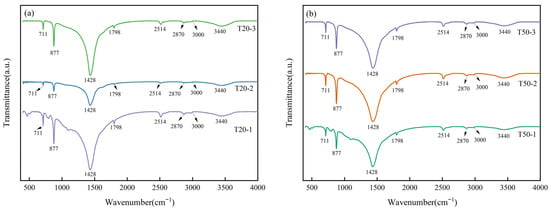

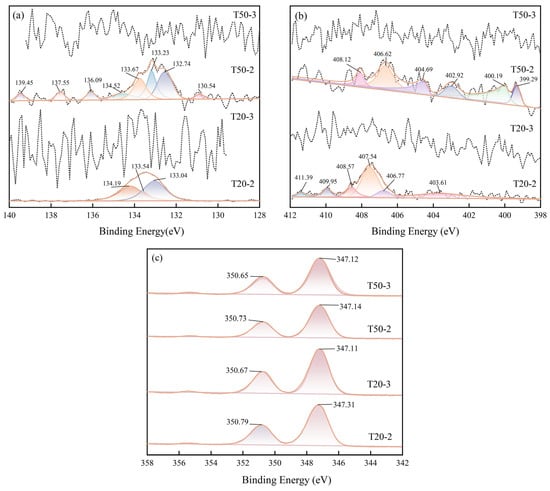

3.2.2. FT-IR Analysis of Limestone

FT-IR analysis was utilized to ascertain alterations in the functional groups on the limestone surfaces under various treatment conditions. The findings are illustrated in Figure 8. Absorption bands in the range of 2870–3000 cm−1 and at 3440 cm−1 are ascribed to the stretching vibrations of surface hydroxyl groups (–OH) [41]. The characteristic bands at 711 cm−1, 877 cm−1, and 1428 cm−1 are all associated with calcium carbonate. The bands at 711 cm−1 and 877 cm−1 correspond to the in-plane and out-of-plane bending vibrations of C–O, respectively [42,43], respectively, while the peak at 1428 cm−1 arises from the asymmetric stretching vibration of C=O in CO32− [44], thereby affirming that the primary mineral component of the limestone is CaCO3. At an equivalent soil column height, the absorption band of limestone subjected to the compound fertilizer treatment at 1428 cm−1 exhibited a narrowing. The absorption band of limestone in the compound fertilizer column at 1428 cm−1 is narrower than that in the chicken manure fertilizer column and the blank column, indicating a more pronounced dissolving impact. In conclusion, despite alterations in the chemical composition of the aqueous components in the leachate, the primary functional group structure of the limestone medium remains unchanged, and no new functional groups have formed.

Figure 8.

FT-IR profile of limestone (a) 20 cm column experimental group (b) 50 cm column experimental group.

No discernible bands of phosphate or nitrate were observed in the rock pieces subjected to the chicken manure fertilizer treatment, potentially attributable to their decreased nitrogen and phosphorus levels. The vibration intensity at 1428 cm−1 was less pronounced than that in the control group, suggesting that chicken manure continued to facilitate limestone dissolution, albeit the compound fertilizer treatment had the most substantial dissolution effect. The lack of nitrate peaks may be attributed to the comparatively low nitrogen concentration in the compound fertilizer and the great hydrolyzability of calcium nitrate.

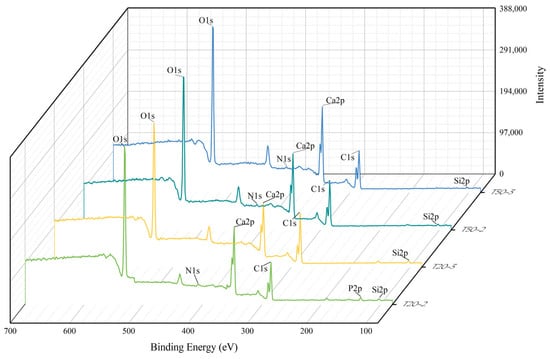

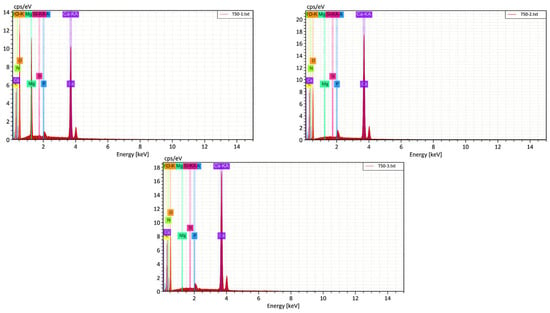

3.2.3. XPS Analysis of Limestone

Comprehensive scans of the binding energy on the limestone surfaces from the compound fertilizer and chicken manure columns were performed (Figure 9) to ascertain the chemical makeup of any newly produced solid phases. The survey spectra indicated an N1s peak in all columns except T20–3, demonstrating nitrogen retention on the limestone surface, agreeing with the hydrochemical data. A P2p signal was detected in column T20–2, demonstrating the presence of phosphorus on the limestone. A little alteration in the Ca2p peak indicated that Ca2+ in the solution interacted with phosphate ions, resulting in the development of chemical precipitates (e.g., CaHPO4) adsorbed onto the limestone surface. This additionally corroborates the existence of Ca–P (e.g., calcium hydrogen phosphate) solid-phase precipitate inside the reaction system. No P2P peak was observed in the comprehensive scan spectrum of T50–2. The absence may be ascribed to the increased thickness of the limestone soil layer, which absorbed a substantial amount of phosphate during infiltration, leading to a phosphate concentration on the limestone surface that was below the instrument’s detection threshold.

Figure 9.

Full–spectrum scan of XPS limestone.

Figure 10a illustrates the P 2p narrow spectrum, revealing three peaks in sample T20–2 with binding energies of 133.54 eV, 134.19 eV, and 133.04 eV. The peaks at 134.19 eV and 133.04 eV correspond to P 2p3/2 and P 2p1/2, respectively [45], signifying the existence of phosphate species such as HPO42− (134.0 eV) and PO43− (133.0 eV) on the limestone surface. In sample T50–2, seven peaks were identified, and their binding energy positions further corroborate that PO43− (132.74 eV, 133.23 eV) is the predominant species [46]. The variations in phosphate binding energy among several experimental groups indicate that phosphate interacted with Ca2+ to produce Ca–P (e.g., calcium hydrogen phosphate) precipitates. Despite the observation of many peaks in the chicken manure column, the spectral noise was substantial; hence, these signals will not be further addressed.

Figure 10.

Narrow XPS spectra of limestone (a) P2p, (b) N1s, (c) Ca2p.

In the N 1s spectrum (Figure 10b), peaks at 407 eV and 408 eV are ascribed to NO3− [47], whereas the broad peak near 400 eV is derived from adsorbed organic nitrogen. The peaks at 403 eV and 405 eV correspond to NO2− and enriched nitrate species [48]. This suggests that nitrogen is predominantly adsorbed on the limestone surface in amorphous forms (including nitrate, nitrite, and organic nitrogen), thereby elucidating the lack of calcium nitrate diffraction peaks in the XRD pattern.

The Ca 2p spectrum (Figure 10c) indicates that the binding energies of Ca 2p in the compound fertilizer columns are typically elevated compared to those in the chicken manure columns, exhibiting more pronounced peaks, which signify enhanced surface ion exchange and increased production of Ca–P precipitates. The increased binding energy in T20–2 relative to T50–2 further suggests that nitrogen and phosphorus-induced chemical interactions with limestone were more significant in the shallower soil column (20 cm). The thicker soil layer (50 cm) significantly impeded the penetration of nitrogen and phosphorus, thereby diminishing the breakdown of carbonate rocks.

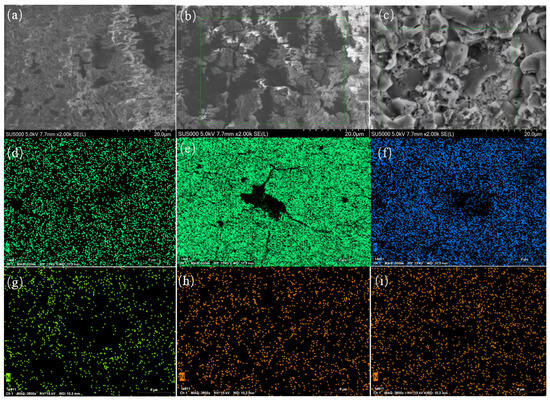

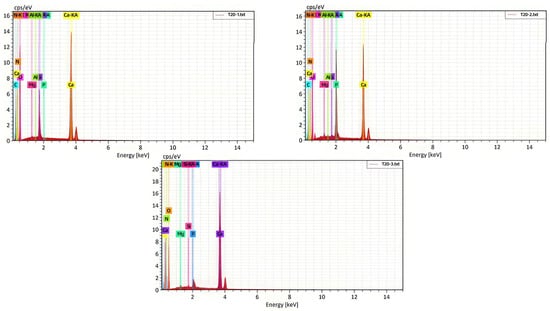

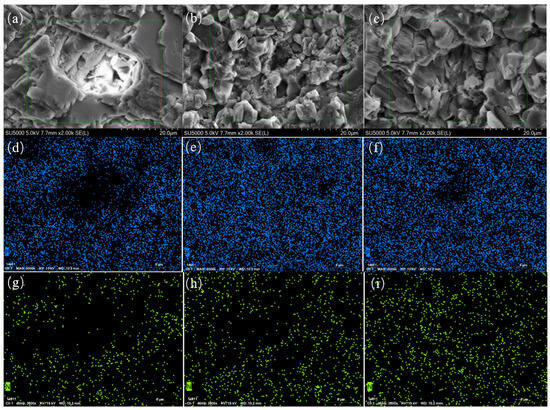

3.2.4. Characterization (SEM/EDS) Analysis of Limestone

Figure 11a–f present the SEM pictures and EDS micrographs depicting nitrogen and phosphorus elements in limestone pieces following 51 days of reaction within a 20 cm-thick soil column. Figure 12 illustrates the EDS element mappings, whereas Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 provide the EDS spectrum data of the limestone surface following the identical reaction duration. The photos indicate slight corrosion on the limestone surface in the blank column; however, more pronounced corrosion is evident in the compound fertilizer and chicken manure solution columns. The SEM photos in the compound fertilizer column depict a coarse limestone surface characterized by numerous irregular etch pits, pores, cluster-like formations, and somewhat deep dissolution pits. Conversely, the chicken dung column displays discernible dissolution steps on the limestone surface, albeit with lesser step depths. The results demonstrate that the compound fertilizer solution has a more pronounced dissolving impact on limestone compared to the chicken manure solution. This is probably attributable to the conversion of ammoniacal nitrogen in both fertilizers into HNO3, facilitated by nitrifying bacteria [49]. The HNO3 generated from nitrification interacts with CaCO3 in limestone, resulting in the formation of Ca2+ and H2CO3, which leads to the dissolution of the limestone [50]. The compound fertilizer, in addition to ammoniacal nitrogen, comprises a substantial quantity of soluble phosphate, which, upon dissolving in water, generates dihydrogen phosphate ions (H2PO4−), hence augmenting limestone disintegration. The limestone surface offers an accessible source of Ca2+ and optimal nucleation sites. Ions initially create minuscule crystal nuclei in faults or active areas on the rock surface. The fertilizer consistently provides phosphorus, enabling phosphate ions in the solution to perpetually adhere to these nuclei, so facilitating the slow growth of crystals into cluster-like formations [51,52]. These results align with the hydrochemical processes and XRD analysis outcomes.

Figure 11.

(a,d,g) depict the SEM image, phosphorus EDS micrograph, and nitrogen EDS micrograph of T20–1, respectively; (b,e,h) illustrate the SEM image, phosphorus EDS micrograph, and nitrogen EDS micrograph of T20–2, respectively; (c,f,i) present the SEM image, phosphorus EDS micrograph, and nitrogen EDS micrograph of T20–3, respectively.

Figure 12.

EDS Element Mapping of T20-1, EDS Element Mapping of T20-2, EDS Element Mapping of T20-3.

Table 4.

EDS energy Spectrum Results of limestone Surface in Column T20–1.

Table 5.

EDS energy Spectrum Results of limestone Surface in Column T20–2.

Table 6.

EDS energy Spectrum Results of limestone Surface in Column T20–3.

Figure 13a–f present the SEM pictures and EDS micrographs depicting the nitrogen and phosphorus elements in limestone pieces following 51 days of reaction within a 50 cm-thick lime soil column. Figure 14 illustrates the EDS element mappings, whereas Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 exhibit the EDS spectrum data of the limestone surface following the identical reaction duration. The surface morphological features of the limestone in the various experimental columns are generally aligned with those noted in the 20 cm limestone soil columns. Likewise, in the T50–2 (compound fertilizer) column, the phosphorus concentration on the limestone surface exceeds that in the chicken dung column. The dissolving degree is comparatively lower than that of the 20 cm column, perhaps attributable to the increased soil height. In the 50 cm compound fertilizer column, a fraction of the phosphate was adsorbed onto soil particles and did not completely leach downhill. The nitrogen concentration on the limestone surface in the T50–3 (chicken dung) column exceeds that in the compound fertilizer column. The higher levels of ammoniacal nitrogen and nitrifying bacteria in the 50 cm chicken dung column facilitated nitrification, resulting in the adsorption of nitrogen ions onto the limestone surface and promoting dissolution. This elucidates the abrupt rise in Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations recorded in the hydrochemical data during the initial water injection in the 50 cm chicken manure column. The results indicate that during fertilization, phosphate and nitrate enhance the dissolution of carbonate rocks, with compound fertilizer exerting a more significant influence. In areas characterized by extensive karst terrain, such as Southwest China, these findings suggest considerable detrimental effects on carbon sequestration initiatives.

Figure 13.

(a,d,g) depict the SEM image, phosphorus EDS spectrum, and nitrogen EDS spectrum of T50–1, respectively; (b,e,h) illustrate the SEM image, phosphorus EDS spectrum, and nitrogen EDS spectrum of T50–2, respectively; (c,f,i) present the SEM image, phosphorus EDS spectrum, and nitrogen EDS spectrum of T50–3, respectively.

Figure 14.

EDS Element Mapping of T50-1, EDS Element Mapping of T50-2, EDS Element Mapping of T50-3.

Table 7.

EDS energy Spectrum Results of limestone Surface in Column T50–1.

Table 8.

EDS energy Spectrum Results of limestone Surface in Column T50–2.

Table 9.

EDS energy Spectrum Results of limestone Surface in Column T50–3.

4. Conclusions

This study examined the impacts of compound fertilizer and chicken manure on the soil-limestone system through laboratory kinetic tests, utilizing varying lime soil thicknesses of 20 cm and 50 cm. Through the integration of hydrochemical analysis and diverse characterization techniques, the following fundamental conclusions were derived: There were substantial disparities in hydrochemical responses. The maximum ion concentrations in the leachate from the compound fertilizer treatment were significantly above those of other groups, particularly HCO3− (16,170.3 mg/L) and phosphorus (920.6 mg/L). This suggests that compound fertilizer significantly enhanced the release and movement of ions within the soil-rock system, whereas the effect of chicken manure fertilizer treatment was very minimal. Chemical fertilizers markedly expedited rock degradation and diminished the carbon sink effect. Nitrogen (transformed into HNO3 via microbial processes) and phosphorus (H2PO4−) in chemical fertilizers reacted with limestone (CaCO3), resulting in the release of H2CO3 by ion exchange. This resulted in a pronounced elevation in HCO3− concentration in the solution, modified the weathering pathway, markedly expedited carbonate rock dissolution, and diminished its intrinsic carbon sink capability. The disintegration rate ranked compound fertilizer as surpassing chicken manure fertilizer. The results of the calculations indicated that the dissolution rate of limestone was maximized under compound fertilizer treatment, whereas the enhancement effect of chicken manure fertilizer on dissolution was minimal. Microscopic findings additionally validated the phosphorus immobilization mechanism. XRD, XPS, and FTIR investigations demonstrated that phosphate ions (PO43−/HPO42−) in the compound fertilizer interacted with calcium ions (Ca2+) in limestone, resulting in the formation of stable hydroxyapatite (Ca-P) precipitates on its surface. This surface precipitation technique further facilitated the dissolving reaction. Moreover, the thickness of the soil layer served a crucial regulating function. SEM observations indicated that all promoting effects were most pronounced under a thin 20 cm soil layer. The dissolving degree, surface nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations, and secondary mineral formation were all markedly greater than those of the 50 cm deep soil layer. This suggests that the thinner soil layer possessed a diminished buffering ability, and the influence of chemical fertilizers on the weathering of the underlying limestone was more pronounced. In conclusion, the utilization of compound fertilizer significantly enhances limestone disintegration, with a notably pronounced effect in karst regions experiencing severe rocky desertification. This discovery indicates that in the southwestern karst region, where chemical fertilizers are extensively utilized, agricultural practices may considerably intensify rock weathering and expedite carbon release, thereby presenting obstacles to regional carbon neutrality objectives. The environmental impact of organic fertilizers, such as chicken dung, is significantly less than that of compound fertilizers.

Author Contributions

L.L.: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization. H.H.: Writing–review and editing. J.L.: Validation, Resources. W.W.: Validation, Investigation. Z.J.: Supervision Validation, Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Supported by the Youth Project of China Nonferrous Metals Group: “Study on the Source and Occurrence State of Hydrocarbon Gases in the Coral Yantianling Granite, Guangxi” (2024KJQN04). Guangxi Science and Technology Plan Project—Young Fund Project (2023GXNSFBA026355). Guangxi Science and Technology Program (Guike AD25069074). Besides this, no other commercial or non-commercial organizations have provided financial support for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Science Data Bank repository, accessible via https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.28951.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Guilin Agricultural Water and Soil Resources and Environment Observation and Research Station of Guangxi, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin, 541006, China, the Collaborative Innovation Center for Water Pollution Control and Water Safety in Karst Area, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin, 541006, China, the Guilin Lijiang River Ecology and Environment Observation and Research Station of Guangxi, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin, 541006, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Author Jiacai Li was employed by the company China Nonferrous Guilin Geology and Mining Research Institute Co., Ltd.

References

- Wu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Luo, W.; Ma, T.; Wang, Y. Multiple Isotope Geochemistry and Hydrochemical Monitoring of Karst Water in a Rapidly Urbanized Region. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2018, 218, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Si, H.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Zhu, D.; Mao, Z.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, K.; Yu, P. Influence of Land Use Types on Soil Properties and Soil Quality in Karst Regions of Southwest China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Q.; Green, S.M.; Quine, T.A.; Liu, H.; Qiu, S.; Liu, Y.; Meersmans, J. Human Activity vs. Climate Change: Distinguishing Dominant Drivers on LAI Dynamics in Karst Region of Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, T.Y.; Tu, W.; Pu, L. Analysis on the Changes of Fertilization Intensity and Efficiency in China’s Grain Production from 1980 to 2019. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Jiang, M.; Su, R.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, R. Fertilization Intensities at the Buffer Zones of Ponds Regulate Nitrogen and Phosphorus Pollution in an Agricultural Watershed. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janzen, H.H. Carbon Cycling in Earth Systems—A Soil Science Perspective. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 104, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlu, E.; Kumar, S. Response of Soil Organic Carbon, pH, Electrical Conductivity, and Water Stable Aggregates to Long-term Annual Manure and Inorganic Fertilizer. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2018, 82, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ling, N.; Wang, T.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, Q. Responses of Soil Biological Traits and Bacterial Communities to Nitrogen Fertilization Mediate Maize Yields across Three Soil Types. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 185, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wei, X.; Cai, Y.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Pu, J. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Rocky Desertification and Soil Erosion in Karst Area of Chongqing and Its Driving Factors. Catena 2024, 242, 108108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Qin, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Su, C. Impact of Sulfuric and Nitric Acids on Carbonate Dissolution, and the Associated Deficit of CO 2 Uptake in the Upper–Middle Reaches of the Wujiang River, China. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2017, 203, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tan, L.; Zhao, M.; Sinha, A.; Wang, T.; Gao, Y. Karst Carbon Sink Processes and Effects: A Review. Quat. Int. 2023, 652, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jin, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Fang, F.; Luo, T.; Li, J. Characterization of Microbial Carbon Metabolism in Karst Soils from Citrus Orchards and Analysis of Its Environmental Drivers. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, C.; Xin, S.; Huang, F.; Cao, J.; Xiao, J. Characteristics of Dissolution Changes in Carbonate Rocks and Their Influencing Factors in the Maocun Basin, Guilin, China. Water 2023, 15, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, A.J.; Martin, J.B.; Young, C.R. Sources and Sinks of CO2 and CH4 in Siliciclastic Subterranean Estuaries. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2019, 64, 1500–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Lian, Y.; Qin, X. Carbon Cycle in the Epikarst Systems and Its Ecological Effects in South China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 68, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, H.; Li, J.; Yang, G.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Zou, S. Influences of Anthropogenic Acids on Carbonate Weathering and CO2 Sink in an Agricultural Karst Wetland (South China). Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, F. Influence of Anthropogenic Sulfuric Acid on Different Lithological Carbonate Weathering and the Related Carbon Sink Budget: Examples from Southwest China. Water 2023, 15, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Du, W.; Sun, P.; He, S.; Kuo, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, J. Study on the Hydrochemistry Character and Carbon Sink in the Middle and Upper Reaches of the Xijiang River Basin, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, P.A.; Oh, N.-H.; Turner, R.E.; Broussard, W. Anthropogenically Enhanced Fluxes of Water and Carbon from the Mississippi River. Nature 2008, 451, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semhi, K.; Amiotte Suchet, P.; Clauer, N.; Probst, J.-L. Impact of Nitrogen Fertilizers on the Natural Weathering-Erosion Processes and Fluvial Transport in the Garonne Basin. Appl. Geochem. 2000, 15, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Fan, J.; Wang, W.; Luo, J.; Kuzyakov, Y.; He, J.-S.; Chu, H.; Ding, W. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Enrichment Accelerates Soil Organic Carbon Loss in Alpine Grassland on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Guo, M.; Sun, X.; Li, L.; Guo, X.; Huang, L.; Xiao, J.; Xu, D.; Liu, D. High Concentration Phosphate Removal by Calcite and Its Subsequent Utilization for Tetracycline Removal. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 37, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Alva, A.; Chen, Q. Manure and Nitrogen Application Enhances Soil Phosphorus Mobility in Calcareous Soil in Greenhouses. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Xu, J.; Kou, T.; Huang, H. Accelerated Phosphorus Accumulation and Acidification of Soils under Plastic Greenhouse Condition in Four Representative Organic Vegetable Cultivation Sites. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 195, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnasamy, V.; Otte, J.; Silbergeld, E. Antimicrobial Use in Chinese Swine and Broiler Poultry Production. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2015, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Li, B.; Yu, A.; Liang, F.; Yang, L.; Sun, Y. The Effect of Aeration Rate on Forced-Aeration Composting of Chicken Manure and Sawdust. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1899–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Gu, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.-J.; Su, J.-Q.; Stedfeld, R. Diversity, Abundance, and Persistence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Various Types of Animal Manure Following Industrial Composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, J.; Lin, L.; Qin, W.; Gao, Y.; Hu, E.; Jiang, J. Occurrence, Fate and Control Strategies of Heavy Metals and Antibiotics in Livestock Manure Compost Land Application: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X. Composting Process and Odor Emission Varied in Windrow and Trough Composting System under Different Air Humidity Conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DZ/T 0295-2016; Specification of Land Quality Geochemical Assessment. Ministry of Land and Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Li, L.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Luo, A. Phosphate in Aqueous Solution Adsorbs on Limestone Surfaces and Promotes Dissolution. Water 2023, 15, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, W. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy in Sample Preparation: Material Characterization and Mechanism Investigation. Adv. Sample Prep. 2024, 11, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C.J.; Jablonski, A. Progress in Quantitative Surface Analysis by X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Current Status and Perspectives. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2010, 178–179, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural, N. The Significance of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis on the Microstructure of Improved Clay: An Overview. Open Geosci. 2021, 13, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilina, L.; Poszwa, A.; Walter, C.; Vergnaud, V.; Pierson-Wickmann, A.-C.; Ruiz, L. Long-Term Effects of High Nitrogen Loads on Cation and Carbon Riverine Export in Agricultural Catchments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 9447–9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Huang, F.; Yang, H.; Yu, S. Role of Anthropogenic Sulfuric and Nitric Acids in Carbonate Weathering and Associated Carbon Sink Budget in a Karst Catchment (Guohua), Southwestern China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 599, 126287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, C.N.; McCarty, P.L.; Parkin, G.F. Chemistry for Environmental Engineering and Science; McGraw–Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Teir, S.; Eloneva, S.; Fogelholm, C.-J.; Zevenhoven, R. Stability of Calcium Carbonate and Magnesium Carbonate in Rainwater and Nitric Acid Solutions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2006, 47, 3059–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Agudo, E.; Putnis, C.V.; Jiménez-López, C.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C. An Atomic Force Microscopy Study of Calcite Dissolution in Saline Solutions: The Role of Magnesium Ions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 3201–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, W. Phosphate Uptake by Calcite: Constraints of Concentration and pH on the Formation of Calcium Phosphate Precipitates. Chem. Geol. 2021, 579, 120365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torit, J.; Phihusut, D. Phosphorus Removal from Wastewater Using Eggshell Ash. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 34101–34109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffolo, S.A.; Comite, V.; La Russa, M.F.; Belfiore, C.M.; Barca, D.; Bonazza, A.; Crisci, G.M.; Pezzino, A.; Sabbioni, C. An Analysis of the Black Crusts from the Seville Cathedral: A Challenge to Deepen the Understanding of the Relationships among Microstructure, Microchemical Features and Pollution Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 502, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Chanda, D.K.; Das, P.S.; Ghosh, J.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Dey, A. Synthesis of Nano Calcium Hydroxide in Aqueous Medium. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 99, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdiri, A.; Higashi, T. Simultaneous Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solution by Natural Limestones. Appl. Water Sci. 2013, 3, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanitha, N.; Jeyalakshmi, R. Structural Study of the Effect of Nano Additives on the Thermal Properties of Metakaolin Phosphate Geopolymer by MASNMR, XPS and SEM Analysis. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 153, 110758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zeng, W.; Xu, H.; Li, S.; Peng, Y. Adsorption Removal and Reuse of Phosphate from Wastewater Using a Novel Adsorbent of Lanthanum-Modified Platanus Biochar. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 140, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusaitis, J.; Grassian, V.H. Atomic Force Microscopy and X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study of NO2 Reactions on CaCO3 (101̅4) Surfaces in Humid Environments. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 9001–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Yang, Y.; Whiddon, R.; Zhu, Y.; Cen, K. Catalytic Deep Oxidation of NO by Ozone over MnO x Loaded Spherical Alumina Catalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 198, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, R.; Malińska, K.; Marfà, O. Nitrification within Composting: A Review. Waste Manag. 2018, 72, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, R.; Li, L.; Cao, W. Anthropogenic Exogenous Nitric and Sulfuric Acids in Karst Plateau Reservoirs and Their Impact on Carbon Sinks. J. Hydrol. 2025, 660, 133394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Kong, M.; Fan, C. Batch Investigations on P Immobilization from Wastewaters and Sediment Using Natural Calcium Rich Sepiolite as a Reactive Material. Water Res. 2013, 47, 4247–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõiv, M.; Liira, M.; Mander, Ü.; Mõtlep, R.; Vohla, C.; Kirsimäe, K. Phosphorus Removal Using Ca-Rich Hydrated Oil Shale Ash as Filter Material–the Effect of Different Phosphorus Loadings and Wastewater Compositions. Water Res. 2010, 44, 5232–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).