Abstract

As global efforts to combat climate change and promote sustainable development intensify, PODEn, as an innovative type of clean, sustainable fuel, has gained growing attention for its potential to support eco-friendly energy transitions, especially concerning the spray characteristics of its blended fuels. Environmental conditions are crucial in the fuel spraying process, which is essential for optimizing combustion efficiency and reducing emissions—key elements of sustainable energy use and climate action. In this study, the parameters of spray morphology, droplet size distribution, and velocity were accurately measured using a constant-volume combustor and high-speed photography. The results demonstrate that as ambient pressure increases, both the spray cone angle and boundary gas entrainment volume increase, while the spray penetration distance and spray volume decrease. These changes, driven by pressure differences and variations in gas density that influence droplet movement and fragmentation, are critical for optimizing fuel injection strategies to enhance combustion efficiency and reduce environmental impact. This aligns closely with the Sustainable Development Goals focused on clean energy, responsible consumption, and climate mitigation. Conversely, as ambient temperature rises, the penetration distance and spray volume increase, whereas the entrainment volume decreases and the spray cone angle narrows. This phenomenon results from the combined effects of temperature on gas density, viscosity, evaporation rate, and convective flow, underscoring the need for adaptive engine designs that leverage these characteristics to improve fuel efficiency and reduce carbon emissions—an essential step toward sustainable development in the energy and automotive sectors.

1. Introduction

With the intensification of global climate change mitigation initiatives globally, the transportation sector is undergoing an unprecedented sustainable energy transition [1,2] due to excessive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from conventional fossil fuels. To achieve carbon neutrality, the development of efficient, clean, and sustainable alternative fuels, along with in-depth investigations of their combustion characteristics, is crucial for alleviating the energy crisis and improving environmental quality [3]. Recognizing this, the internal combustion engine (ICE) industry needs to place greater emphasis on the development and integration of renewable and sustainable alternative fuels that can significantly reduce emissions without requiring a complete overhaul of existing engine technologies [4,5,6,7]. Polymethoxy dimethyl ether (PODE), a promising new oxygenated fuel, has emerged as a viable alternative to diesel in compression-ignition engines due to its excellent performance in fuel efficiency and emission control [8,9,10]. The general molecular structure of PODEn consists of a single oxygen-rich chain (CH3O(CH2O)nCH3) (denoted by n), and the PODE molecular structure is free of C–C bonds and shows great potential for reducing soot emissions and improving auto-ignition performance [11]. The polymerization range in current synthesis processes typically spans from n = 1 to 6 [12]. PODE1 is characterized by a low cetane number and low boiling point, which negatively impact ignition and storage, making it unsuitable for engine applications [13]. Although PODE2 meets the cetane number requirement for engine operation, its low flash point poses considerable risks during transportation and storage [14]. For n values greater than 6, the higher melting point can lead to precipitation at ambient temperatures, resulting in clogging of the fuel supply system [14,15]. Therefore, n is generally taken between 3 and 5. PODE3-5 exhibits a higher cetane number and improved low-temperature fluidity, making it a viable, sustainable alternative to conventional diesel fuels. Modern mainstream alternative fuels for internal combustion engines—including biodiesel, alcohol fuels (methanol and ethanol), hydrogen, and ammonia—each possess distinct characteristics and limitations. Biodiesel (e.g., fatty acid methyl esters) is a renewable ester fuel with good compatibility with diesel and a relatively high cetane number (50–60). However, its oxygen content is only about 10%. Its high viscosity (4–6 mm2/s at 40 °C) can cause nozzle clogging and incomplete atomization. Additionally, its high cold filter plugging point limits its use in low-temperature environments [16]. The fuel performance of biodiesel also depends heavily on its feedstock [17]. Methanol and ethanol are oxygenated fuels with high oxygen content (both approximately 34.8%), which significantly reduces particulate emissions. However, their extremely low cetane numbers (methanol: 3–8; ethanol: 8–10) result in poor ignition performance. Furthermore, their low boiling points and strong hydrophilicity may cause fuel system corrosion and phase separation during storage. Methanol’s high latent heat of vaporization also makes its direct use as a sole fuel impractical [18]. Hydrogen and ammonia are carbon-free fuels that eliminate CO2 emissions. However, hydrogen has a low volumetric energy density and poses higher safety risks during storage and transportation. Ammonia exhibits low flammability and a narrow combustion range, requiring auxiliary ignition measures. Its combustion generates difficult-to-control NOx emissions [19]. Moreover, the direct injection method used in hydrogen internal combustion engines (H2ICEs) may exacerbate particulate formation [20,21]. Compared to these modern fuels, PODE (polyoxymethylene dimethyl ether) offers distinct comprehensive advantages. Its high oxygen content (up to 47.0% at P100) surpasses that of biodiesel and methanol/ethanol, and its molecular structure lacks C–C bonds, fundamentally inhibiting soot formation [22,23]. Its cetane number (P100: 78.6) significantly exceeds that of alcohol fuels and rivals high-quality diesel, ensuring excellent ignition performance without requiring modifications to the engine ignition system. PODE’s kinematic viscosity is lower than that of diesel and biodiesel, enhancing atomization quality. It remains liquid at room temperature and atmospheric pressure, exhibits excellent miscibility with diesel (no phase separation after 50 days of static storage), requires no high-pressure storage or transportation equipment, and is highly compatible with existing diesel fuel systems. Research by Iannuzzi et al. [24] indicates that the addition of PODE substantially reduces the soot-dominated phase. Experiments by Li et al. [25] investigated PODE’s effects on the spray and atomization characteristics of diesel fuel in a constant-volume chamber at 293 K. The results demonstrated that PODE serves as a promising sustainable alternative to conventional diesel fuels under the 293 K condition. The results showed that the Hirayasu model significantly overestimated the spray tip penetration of PODE compared to the experimentally measured data. In addition, the effect of PODE on the spray characteristics of gasoline needs to be further investigated. Liu et al. [26] showed that with the addition of PODE, the spray cone angle of both gasoline and diesel increased; the liquid penetration distance of gasoline increased, and the liquid penetration distance of diesel decreased.

Under actual operating conditions of a diesel engine, the in-cylinder combustion process is influenced not only by the inherent properties of the fuel but also by the spray behavior of the fuel atomized by the nozzle. Fuel spray characteristics play a crucial role in the combustion process, directly affecting mixture formation quality, combustion efficiency, and pollutant generation. The spraying process involves complex physical phenomena such as fuel fragmentation, atomization, evaporation, and mixing with air, all of which are influenced by multiple factors. Ambient pressure and temperature, as key external conditions during engine operation, significantly impact the spray characteristics of PODE-blended fuels. However, spray characteristics, particularly at the droplet micro-particle size level, remain relatively underexplored. Therefore, investigating the effects of spray characteristics is essential. In this study, macroscopic parameters such as spray cone angle and spray penetration distance of diesel/PODE3-4 blended fuels were examined under varying ambient backpressures (3, 4, and 5 MPa) and ambient temperatures (300, 400, and 500 K) using a high-temperature, high-pressure, constant-volume bomb experimental platform combined with high-speed camera technology.

2. Materials and Methods

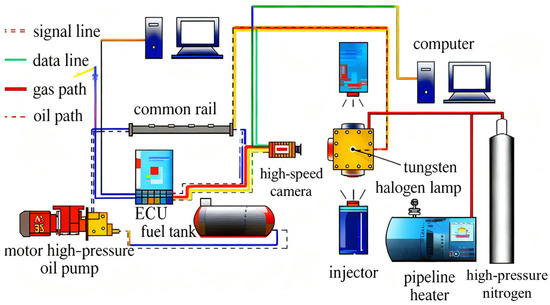

The specific design of the test setup is illustrated in Figure 1. The constant volume bomb test rig shown in Figure 1 serves as the core equipment for simulating the fuel spray process under various ambient pressure and temperature conditions in this study. It is engineered to enable precise control of environmental parameters and facilitate observation of the spraying process. The internal structure is square-shaped, with side lengths of 150 mm × 150 mm and a wall thickness of 65 mm. These design parameters ensure that the device can withstand static pressures up to 6 MPa and transient burst pressures up to 15 MPa. The fixed-capacity bomb test bench is equipped with an advanced pressure control system. This system monitors real-time pressure changes inside the bomb using high-precision pressure sensors and compares them with preset pressure values. When the pressure deviates from the set value, the control system automatically adjusts the air intake or exhaust devices to maintain a stable pressure inside the bomb accurately. A quartz glass window with a radius of 55 mm is installed on the side of the bomb. A high-speed camera (FASTCAM-SA7) records the entire spraying process at 20,000 frames per second, with a resolution of 320 × 256 pixels and an exposure time of 33,937 microseconds. The high-speed textured image camera unit primarily consists of a light source, a collimation system, a shadowgraph mirror, a knife edge, and the high-speed camera. The high-brightness pulsed laser light source provides intense, stable illumination for the entire system. The collimation system converts the light from the source into parallel rays, ensuring uniform illumination through the spray area within the constant volume bomb. The shadowgraph mirror then reflects and focuses the light passing through the spray area so it can be accurately projected onto the knife edge. The knife-edge highlights the boundaries and internal structure of the spray by blocking part of the light and converting changes in light refraction into variations in light intensity. The high-speed camera captures the light processed by the shadowgraph system at a very high frame rate, enabling visualization of the instantaneous dynamics of the spray. Four electric heating tubes, which are solid round rods with embedded heating wires, are arranged along the four edges of the square cavity to regulate the ambient temperature within the cavity. In the experiment, the temperature sensor achieves a measurement accuracy of ±1 °C, providing real-time feedback on the temperature inside the fixed-volume bomb. This allows the temperature control system to promptly adjust the heating or cooling power, ensuring temperature stability throughout the experimental process. The fuel injection system is critical for injecting the PODE-blended fuel into the fixed-volume bomb. It primarily consists of a fuel injector, oil pump, and control system. The pump supplies sufficient pressure to the injector, enabling the fuel to overcome the environmental pressure inside the bomb and achieve effective injection. The control system precisely regulates parameters such as injection timing, pulse width, and injection pressure. In this experiment, an injection pressure of 120 MPa, combined with varying ambient pressures and temperatures, facilitates a comprehensive study of the effects of different factors on the spray characteristics of PODE-blended fuels.

Figure 1.

Experimental apparatus.

The specific conditions of the test are shown in Table 1. PODE3-4 was chosen as a representative of the four test fuels, namely P0 (Pure Diesel: Using commercially available No. 0 diesel fuel from China National Petroleum Corporation, Beijing, China), P20 (80% diesel and 20% PODE: Provided by Qingdao Tongchuan Petrochemical Engineering Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China), P50 (50% diesel and 0% PODE), and P100 (pure PODE). The relevant physical property parameters are detailed in Table 2. Density, viscosity, surface tension, and volatility are the four key parameters that strongly influence spray injection [27,28,29,30]. For the physical property parameters of P20 and P50 blended fuels, we used Kay’s mixing law for estimation, which is given in [31]:

where n is the number of fuel components; is the physical parameter of the fuel blend; is the mass fraction of the ith fuel; and is the physical parameter of the ith fuel.

Table 1.

Experimental condition.

Table 2.

Physical properties of experimental fuels.

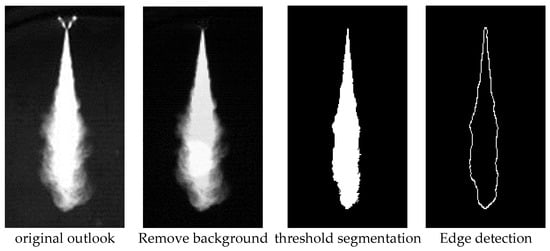

The spray TILL grayscale image is captured using a high-speed camera and processed through a custom procedure developed in MATLAB 2024a, which includes the following steps: (1) background removal to enhance the spray image, (2) threshold segmentation to convert the image to grayscale. The grayscale histogram of the spray-enhanced image exhibits a characteristic bimodal distribution with a distinct valley. One peak corresponds to the low grayscale values (near 0) of the background region, while the other peak corresponds to the high grayscale values of the spray droplet aggregation area. The valley between these two peaks serves as the critical threshold separating the grayscale values of the background and spray regions. By identifying the gray level at this valley in the histogram, an initial threshold range can be established. In experiments, the initial threshold range for diesel/PODE3-4 blended fuel spray images was 65–90. This range enables preliminary separation of the main spray area, preventing misidentification of background noise due to excessively low gray values and avoiding loss of spray edge regions caused by excessively high gray values. Building upon this initial range, iterative threshold refinement was performed by constraining the edge contours at the injector nozzle’s pixel coordinates (x, y). The core criterion was that the nozzle pixels must lie precisely on the spray edge contour. By sequentially adjusting the threshold using the threshold function, the final threshold is determined when the nozzle pixel aligns exactly with the boundary contour of the spray region in the binarized spray image (pixels below the threshold are set to 0, and those above are set to 1). Subsequently, the Sobel operator—which calculates gradients through discrete differences between rows and columns within a 3 × 3 neighborhood, producing clearer contours in images with grayscale gradients and high noise—and the Canny operator—which detects edge pixels using two thresholds, including weak pixels only when connected to strong pixels, thereby resisting noise-induced false edges and yielding a more continuous oil mist boundary—were applied to determine the boundary curve of the oil mist. (3) edge extraction to detect the spray boundaries. Finally, regions outside the spray edges are removed to produce the final image. The macroscopic spray feature parameters are then calculated based on this final image and the calibrated conversion rate. The resulting spray image is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process procedure of spray imaging.

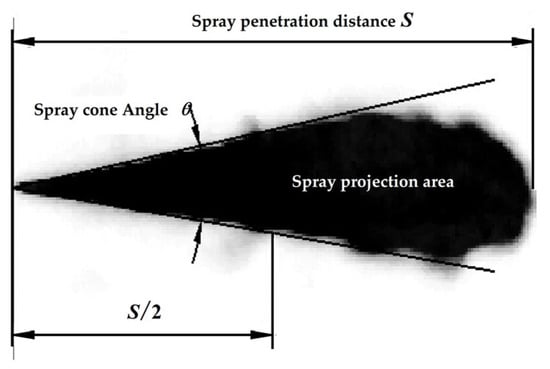

The spray parameters are illustrated in Figure 3. Spray penetration distance (SPD) is defined as the distance from the nozzle outlet to the spray tip. The spray cone angle (SCA) is the angle formed between the spray edges and the nozzle axis at half the spray penetration distance. The spray projected area (SPA) refers to the area projected onto the plane of the viewport. Spray performance is characterized by specific spray parameters, particularly the magnitude of the spray cone angle and spray penetration distance, as discussed in this paper. A larger SCA and SPA indicate greater fuel dispersion and enhanced ability to entrain surrounding air, which promotes subsequent combustion and reduces emissions in the actual engine. Therefore, a larger SCA and SPA correspond to improved spray performance.

Figure 3.

Spray parameter.

3. Results and Discussion

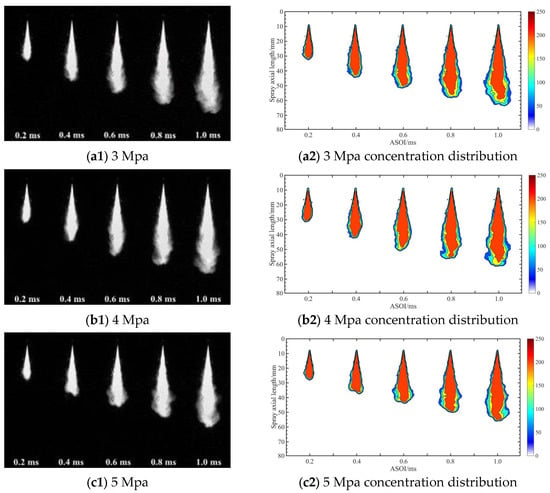

3.1. Effect of Ambient Pressure

Figure 4 illustrates the spray morphology and concentration distribution of P20 under varying ambient backpressures (3, 4, and 5 MPa) based on uniform experimental conditions (ambient temperature of 300 K), as detailed in Table 1. In Figure 4, under lower ambient pressure (3 MPa), the spray exhibits an elongated morphology with a longer penetration distance and relatively sharp spray edges due to slower fuel jet diffusion. At low ambient pressure, air resistance to the fuel jet is minimal, allowing the jet to propagate at high speed, resulting in extended spray penetration. The reduced air resistance also means less inhibition of radial diffusion, producing clearer spray edges. Conversely, at an ambient backpressure of 5 MPa, the spray penetration distance decreases significantly, the spray becomes denser, the spray cone angle widens, and the edges become blurred, indicating more vigorous mixing of fuel and air. Higher ambient pressure increases air resistance against the fuel jet, reducing its velocity and penetration distance. This elevated pressure enhances the interaction between air and fuel, promoting fragmentation and atomization of the jet, which leads to a coarser spray with a larger cone angle and blurred edges. Additionally, at the same spray moment, the axial elongation of the jet contracts, and the jet morphology transitions from slender to stubby. According to fluid dynamics principles, the resistance experienced by an object moving through a fluid depends on factors such as fluid density, object velocity, and object shape [34]. In this experiment, the fuel spray can be approximated as an object moving through air. As air density increases, the spray’s resistance can be expressed as:

where (/(N) which is the resistance, /(kg·m−3) is the air density, /(m·s−1) is the spray velocity, is the resistance coefficient, /(m2) is the windward area of the spray). Due to the increase in drag force, the spraying distance of the fuel oil is reduced under otherwise relatively stable conditions. As shown in the concentration distribution in Figure 4, with the increase in spray back pressure, the initial concentration of the spray decreases. This is attributed to the initial turbulence velocity after fuel injection; higher back pressure intensifies environmental effects, causing a rise in the temperature around the spray. This temperature increase accelerates fuel evaporation and reduces particle density.

Figure 4.

Spray morphology and concentration distribution of 3, 4, 5 Mpa back pressure.

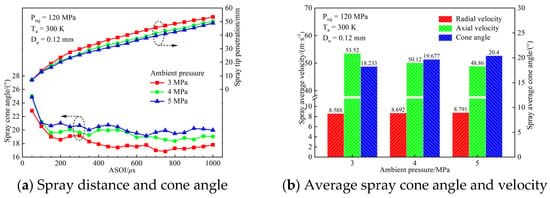

Figure 5 illustrates the spray characteristics of P20 under varying ambient backpressures. In Figure 5a, under identical operating conditions, the spray penetration distance decreases as the ambient backpressure increases. This occurs because higher ambient backpressure raises the density of the surrounding gas, which inhibits spray formation, restricts the initial spray velocity, and reduces the initial kinetic energy. As shown in Figure 5b, the average spray velocity decreases by 4.66 m/s when the ambient backpressure increases from 3 MPa to 5 MPa, resulting in a smaller curvature of the spray penetration distance. Conversely, the spray cone angle exhibits the opposite trend: higher ambient pressures produce a larger spray cone angle. This is because increased air resistance limits axial spray development and pushes the spray to spread radially, enlarging the cone angle. Additionally, the higher backpressure increases the density of the surrounding gas, enhancing the interaction between the conical surfaces of the spray and the environment, thereby promoting diffusion at the spray edges. From a sustainable engineering viewpoint, this enhanced radial spread and diffusion can facilitate more complete combustion, reducing unburned hydrocarbons and particulate matter emissions—directly contributing to sustainable development goals focused on clean air and environmental stewardship.

Figure 5.

Spray Characteristics of P20 Under Different Ambient Pressures (Distance, Cone Angle, Velocity).

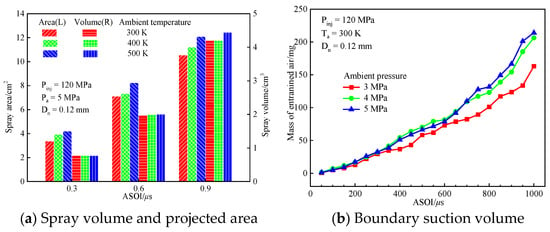

Figure 6a presents an analysis of the spray volume, projected area, and boundary entrainment characteristics of the blended fuel (P20) under varying environmental back pressures. At the same ambient temperature, the spray volume decreases as ambient back pressure increases, and this effect becomes more pronounced over time. The projected spray area exhibits a similar trend. This behavior is attributed to the increased gas density, which raises air resistance, inhibits spray volume diffusion, and reduces the projected spray area. From the perspective of sustainable development, this finding provides key guidance for optimizing the combustion process of sustainable blended fuels: by regulating back pressure to suppress excessive spray diffusion, we can minimize fuel adhesion losses on the combustion chamber wall, enhance fuel utilization efficiency, and further reduce fuel consumption per unit power—directly aligning with the “responsible energy consumption” imperative in global sustainable development goals. Moreover, reducing unnecessary spray diffusion also helps avoid localized fuel-rich zones during combustion, which in turn curbs the generation of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter (PM), reinforcing the role of P20 fuel in advancing clean transportation. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 6b, ambient pressure also influences the fuel spray fragmentation and atomization process, indirectly affecting the spray penetration distance. At a lower ambient pressure of 3 MPa, the restraining effect of the surrounding air on the fuel spray is relatively weak, causing the fuel liquid column to break up more slowly and produce larger droplets. These larger droplets have slower settling velocities and greater inertia, allowing them to penetrate further into the air, thereby increasing the spray penetration distance. In contrast, at a higher ambient pressure of 5 MPa, the air exerts a stronger influence on the fuel spray, causing the liquid column to break up more rapidly into numerous fine droplets. These smaller droplets have a larger specific surface area, experience greater friction with the air, and are more affected by air resistance, which rapidly reduces their velocity and consequently decreases both the spray penetration distance and spray volume. This atomization advantage is particularly valuable for P20, as it strengthens the application potential of this sustainable blended fuel in diesel engines, supporting the global transition from fossil diesel to low-carbon alternative fuels.

Figure 6.

Spray Volume, Projected Area, and Boundary Suction Characteristics of P20 under Different Ambient Pressures.

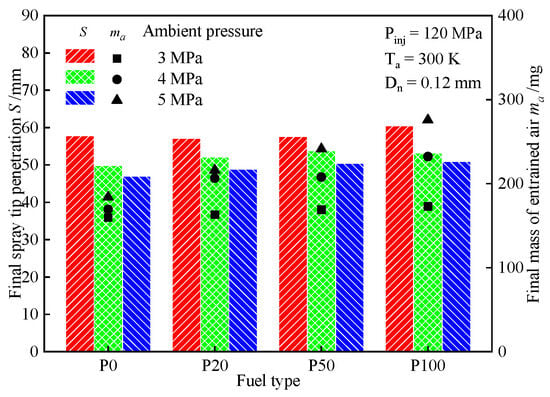

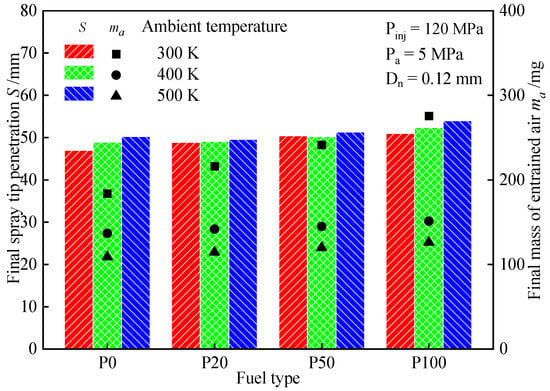

Figure 7 presents a comparative analysis of the spray characteristics of fuels ranging from P0 to P100 under ambient backpressures of 3, 4, and 5 MPa. Under consistent injection conditions, increasing ambient pressure leads to a reduction in penetration distance for all fuel blends. Specifically, the penetration distance decreases by 7.9 mm and 2.9 mm for P0, by 5.0 mm and 3.3 mm for P20, by 3.9 mm and 3.4 mm for P50, and by 7.2 mm and 2.24 mm for P100, respectively. These results indicate that diesel fuel (P0) experiences the most significant change in spray penetration, reflecting its higher sensitivity to variations in ambient backpressure. In contrast, PODE-blended fuels (P20–P100) exhibit more stable penetration distance responses to backpressure fluctuations. This stability is critical for sustainable engine operation: it allows engines to maintain consistent spray performance across diverse working conditions, avoiding emission spikes caused by spray instability and strengthening the adaptability of sustainable fuels in practical applications. Moreover, a higher proportion of PODE in the blend correlates with greater spray penetration distance, with an average increase of 3.9 mm. This trend can be attributed to the physical properties of the fuels: as shown in Table 2, PODE exhibits lower viscosity, and blending it with diesel reduces the overall viscosity of the fuel mixture. According to spray dynamics theory, reduced fuel density and viscosity improve momentum transfer efficiency during atomization, resulting in the maximum penetration distance observed for P100. From a sustainable energy utilization standpoint, this enhanced momentum transfer efficiency translates to more effective spray propagation and air-fuel mixing—two prerequisites for complete combustion. As ambient pressure increases, the mass of entrained ambient gas also rises across all tested fuels. From 3 MPa to 5 MPa, the entrained gas mass increases by 24.4 mg for pure diesel, 52.9 mg for P20, 72.2 mg for P50, and 102.8 mg for P100. This suggests that PODE-blended fuels exhibit superior atomization performance. The increase in entrained gas volume is primarily due to elevated ambient backpressure, which enhances gas density, reduces the mean free path between gas molecules, and intensifies droplet–gas interactions during spray propagation. Consequently, the volume of entrained gas at the spray periphery increases. Furthermore, higher backpressure induces flow field instabilities and deformation, promoting droplet breakup and fine atomization, which leads to smaller droplet sizes and improved dispersion of the fuel mist into the surrounding medium. This amplifies the air entrainment effect at the spray boundary. Among the tested fuels, diesel demonstrates the most pronounced vortical structures at the spray edge, indicating that PODE-based blends (P20–P100) offer enhanced air-fuel mixing performance compared to conventional diesel. This superior mixing performance is a pivotal factor in unlocking the full potential of PODE as a sustainable diesel alternative: it directly addresses the emission drawbacks of traditional diesel engines while maintaining or improving energy efficiency, thereby providing a feasible technical path for the transportation sector to transition toward sustainable energy systems and meet global carbon neutrality commitments. The spray cone angle and penetration distance exhibited under 4 MPa conditions are favorable.

Figure 7.

Spray characteristics of blended fuel at ambient back pressure (3, 4, 5 Mpa).

3.2. Effects of Ambient Temperature

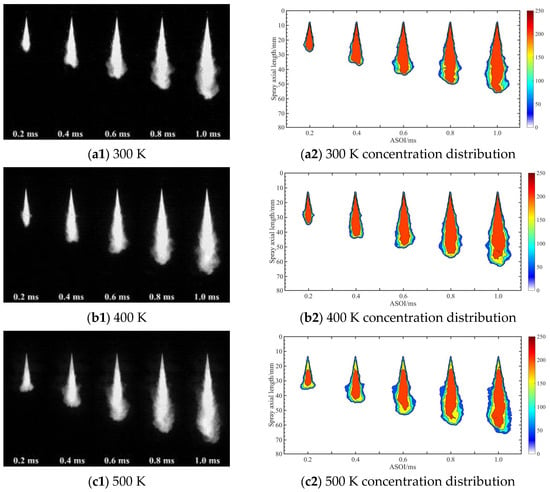

Figure 8 illustrates the spray morphology images with spray concentration field distribution of P20 fuel at different ambient temperatures (300, 400, and 500 K). In Figure 8, at the same spraying time point, the change in ambient temperature has a significant effect on the morphology of the P20 spray. At the low temperature of 300 K, the spray liquid core shows a thicker and shorter morphology, with a more rounded core head and a relatively longer column length. This is because at low temperatures, the viscosity of the fuel is high and the surface tension is large, making it difficult to quickly break up and disperse the fuel after it is sprayed from the nozzle, and the liquid inside the liquid nucleus has a stronger force between each other, resulting in the liquid nucleus being less easy to be deformed and elongated. At the same time, the density of the air in the low-temperature environment is larger, the resistance of the spray is also larger, further limiting the development of the spray, so that the length of the liquid core is shorter, and the head is thicker. From the perspective of sustainable fuel utilization, poor spray atomization leads to uneven air-fuel mixing, which often causes incomplete combustion. This inefficiency not only wastes fuel but also increases emissions of unburned hydrocarbons and particulate matter (PM), hindering the achievement of clean transportation goals. Therefore, this finding highlights the need to avoid low-temperature operating conditions that suppress P20’s spray performance or to pair it with adaptive injection strategies to ensure that the emission reduction benefits of sustainable fuels are fully realized. When the temperature increases to 400 K, the head of the spray liquid nucleus starts to become slightly sharper, the length of the liquid column increases, and the overall morphology is more elongated compared to 300 K. This occurs because elevated temperatures reduce fuel viscosity and decrease surface tension, making the fuel more susceptible to aerodynamic forces after exiting the nozzle, which leads to fragmentation and deformation. The higher temperature increases the thermal movement of the fuel molecules and weakens the intermolecular forces, which allows the liquid nuclei to be stretched and dispersed more easily, and the length of the liquid column is increased. At the same time, the increase in air temperature also leads to a decrease in its density, which reduces the resistance to spraying accordingly and favors the development of spraying. Combined with the concentration distribution graph in Figure 8, with the temperature of the body high, P20 end of the low concentration area of the coverage area is correspondingly enlarged, the main body of the concentration is weakened, because of the temperature will make the evaporation of the fuel significantly increased, the fuel molecules of the thermal movement of the fuel is intense, the intermolecular force is weakened, the fuel is more likely to be from the liquid state into a gaseous state, resulting in an increase in the spray through the distance, the front end of the concentration is higher. From the perspective of sustainable combustion optimization, the enhanced evaporation effect offers dual benefits. First, the gaseous fuel mixes more uniformly with air, improving combustion efficiency and reducing pollutant emissions. Second, it prevents liquid fuel from adhering to the combustion chamber walls, which can cause carbon deposits and increase maintenance costs. This extends the service life of engine components and promotes the sustainability of both energy use and equipment operation.

Figure 8.

Spray morphology and concentration distribution of 300, 400, 500 K ambient temperature.

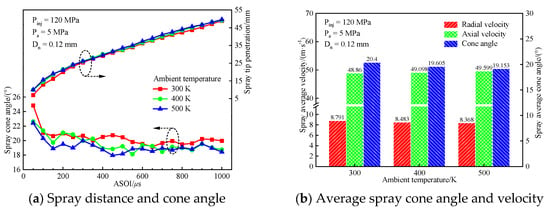

Figure 9 illustrates the spray characteristics (distance, cone angle, velocity) of the blended fuel (P20) at ambient temperatures of 300, 400, and 500 K. As shown in Figure 9a, under identical ambient pressure, the spray exhibits pronounced initial behavior as ambient temperature increases, with higher temperatures resulting in longer spray penetration distances. This occurs because the saturated vapor pressure of P20 fuel droplets rises with increasing ambient temperature, significantly accelerating evaporation rates. The rapid diffusion of fuel molecules from the droplet surface into the gas phase reduces the density of the surrounding gas medium, substantially decreasing the air resistance experienced by the droplets. Simultaneously, the momentum imparted by the evaporating fuel gas phase provides an additional propulsive force to the droplets. Together, these effects drive a rapid increase in penetration distance during the initial spray phase at elevated ambient temperatures. Consequently, the high-temperature group shows a distinct advantage in penetration distance during the initial phase, with growth slowing during the middle and later stages. The maximum difference at the same time point reaches 3 mm. As the spray progresses, droplets continue to evaporate and fragment, leading to a sharp increase in the mixing intensity between the gas and liquid phases. At this stage, the increase in spray penetration distance depends more on the momentum exchange process between the gas and liquid phases, while the constricting effect of the constant ambient back pressure (5 MPa) gradually becomes a dominant factor. Although ambient temperature still influences evaporation, the sharp reduction in droplet count during the mid-to-late stages significantly diminishes evaporation’s contribution to penetration distance. Concurrently, variations in gas–liquid momentum exchange are further constrained by the ambient back pressure, ultimately slowing the penetration distance growth rate across different temperature groups. Moreover, Figure 9a,b reveal that the spray cone angle decreases with increasing temperature. This occurs because elevated ambient temperatures significantly increase the saturated vapor pressure of P20 fuel droplets, accelerating evaporation rates. The rapid conversion of droplets to the gas phase within a short timeframe drastically compresses the effective diffusion range of the liquid-phase spray. Simultaneously, under constant back pressure, the temperature increase reduces air density, weakening the air’s entrainment resistance on droplets. However, this effect is entirely dominated by the “liquid-phase contraction” triggered by rapid droplet evaporation, causing the spray cone angle to decrease as temperature rises.

Figure 9.

Spray Characteristics of P20 at Different Ambient Temperatures (Distance, Cone Angle, Velocity).

As shown in Figure 9b, the average spray velocity increases proportionally with ambient temperature, reaching a maximum increase of 0.75 m/s. This stems from the significantly accelerated evaporation rate of P20 droplets at elevated temperatures, leading to a continuous reduction in liquid mass. According to the law of conservation of momentum, the initial momentum of the injected fuel is provided by the injection pressure. The decrease in droplet mass drives a corresponding increase in its velocity to maintain momentum balance. From the perspective of sustainable combustion, this mass reduction-driven velocity increase is not merely a physical response but a key enabler of cleaner, more efficient energy conversion: accelerated evaporation means fuel droplets transition from liquid to gaseous state earlier in the spray process. Simultaneously, under constant ambient back pressure, the temperature increase reduces air density, thereby weakening the aerodynamic drag on the droplets. This diminished aerodynamic drag further enhances the spray velocity.

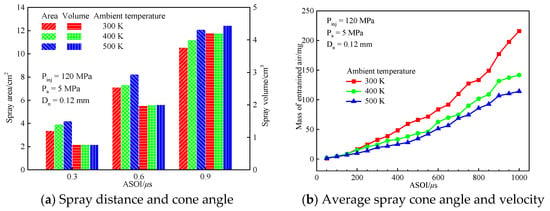

Figure 10 presents the analysis of spray volume, projected area, and boundary entrainment characteristics for blended fuel (P20) at ambient temperatures of 300, 400, and 500 K. In Figure 10a, spray volume increases with rising ambient temperature, while the corresponding spray projected area grows proportionally, expanding by 22.4% and 6.5%, respectively. This occurs because elevated ambient temperatures raise the saturated vapor pressure of P20 droplets, dramatically accelerating evaporation rates. On one hand, this rapid expansion of the vapor phase region drives spray spread in three-dimensional space through gas–liquid momentum exchange, directly increasing spray volume. On the other hand, under constant back pressure, the temperature increase reduces air density, weakening air resistance to droplets. This releases constraints on radial and axial droplet diffusion, further expanding the spray’s spatial coverage. Concurrently, the evaporation sensitivity of the PODE component in P20 becomes more pronounced with rising temperature, intensifying both droplet evaporation and spray spreading processes. This ultimately results in synergistic growth between spray volume and its two-dimensional projected area. From the perspective of sustainable development, optimizing spray volume and projected area based on temperature is highly practical. A larger spray volume and an expanded projected area result in a more uniform spatial distribution of fuel droplets, providing a foundation for thorough mixing with air. As shown in Figure 8 (concentration distribution), increased temperature leads to relatively lower mixed gas density and reduced air resistance, enabling easier spray penetration through the air and larger spray volume. However, the average spray cone angle decreases by 1.2°. Figure 10b indicates that entrainment volume decreases with rising temperature. This occurs because elevated ambient temperature significantly reduces air density, directly lowering the mass of air that can be entrained per unit volume, thereby decreasing entrainment. As shown in Figure 9b, the elevated ambient temperature accelerates heat transfer between droplets at the spray edge and the adjacent high-temperature gas at the leading edge. This reduces the velocity gradient on the outer cone surface of the spray, significantly enhancing mixing and evaporation efficiency, which in turn leads to a reduction in the spray cone angle. The spray volume and penetration distance demonstrated under the 400 K environment were superior.

Figure 10.

Spray Volume, Projected Area, and Boundary Suction Characteristics of P20 at Different Ambient Temperatures.

Figure 11 illustrates the variation patterns of the final spray penetration distance and boundary gas entrainment for P0–P100 fuels under different environmental conditions. Combined with Figure 10b, it is evident that higher temperatures result in fewer entrained particles. This occurs because increased temperature leads to lower ambient concentration, reduced fuel viscosity, and decreased surface tension, all of which diminish the entrainment capacity. At 300 K, the difference in boundary coiling capacity between P0 and P100 reaches a maximum of 75 mg, indicating that diesel fuel exhibits a significant response to ambient temperature changes. For 400 K and 500 K, the relative difference between the two decreases to 15 mg and 18 mg, respectively. The differences among these temperatures are substantial. This is because temperature increases alter the physicochemical properties of the fuel. According to related research [35], when the fuel temperature exceeds 50 °C, in addition to relatively small changes in viscosity, surface tension, speed of sound, and elastic modulus exhibit varying degrees of increase. As shown in Table 2, the surface tension of the fuel increases with higher PODE content. Consequently, the Weber number is largest for P0 and smallest for P100. A larger Weber number facilitates easier liquid breakup and atomization. Therefore, at higher ambient temperatures, atomization is less effective for P100. As a result, the gap in boundary gas swept volume among the blended fuels narrows with increasing temperature.

Figure 11.

Spray characteristics of blended fuels at ambient temperatures (300, 400, 500 K).

4. Conclusions

(1) Under the same operating conditions, increasing the ambient backpressure enhances ambient gas drag, facilitating faster breakup and atomization of fuel droplets. Specifically, the spray cone angle, radial spray velocity, and boundary gas entrainment of P20 fuel exhibit an increasing trend, while the spray penetration distance, spray volume, and its projected area decrease correspondingly. The cone angle at P20 increased by an average of 1.61 mm and 2.14 mm from 3 MPa to 5 MPa, respectively. The spray penetration distance decreased by 5.0 mm and 3.3 mm, respectively, while the boundary gas entrainment volume increased by 52.9 mg. This optimized atomization behavior is pivotal for improving combustion efficiency and curbing pollutant emissions, directly supporting efforts to advance sustainable energy utilization and meet global climate targets. Such insights enable the fine-tuning of engine parameters to align with sustainable development goals focused on clean and efficient energy conversion.

(2) Under the same operating conditions, an increase in ambient temperature expands the spray low-concentration region, leading to increased fuel penetration distance, spray volume, and spray area, while the spray cone angle, boundary gas entrainment, and radial spray velocity decrease. When elevated from 300 K to 500 K, the maximum difference in the initial spray penetration distance of P20 fuel reached 3 mm, with the average spray velocity increasing by up to 0.75 m/s. Compared to 300 K, the spray volume expanded by 22.4%, the spray projected area increased by 6.5%, and the spray cone angle decreased by an average of 1.2°. These findings are critical for optimizing engine performance across varied thermal environments, a key enabler for developing sustainable transportation systems that operate efficiently under diverse climatic conditions. Leveraging this knowledge to refine combustion processes can drive reduced fuel consumption and lower greenhouse gas emissions, thereby contributing to the broader agenda of sustainable development centered on energy efficiency and carbon neutrality.

(3) Under identical experimental conditions, pure PODE demonstrated the most favorable spray characteristics, followed by the 50% and 20% blended fuels, with pure diesel exhibiting the least optimal performance. Specifically, the spray penetration distance of P100 increased by an average of 3.9 mm compared to P0. When the ambient back pressure increased from 3 MPa to 5 MPa, the total decrease in penetration distance for P100 was only 9.44 mm, significantly lower than that of P0, which was 10.8 mm, demonstrating superior spray stability. Additionally, the increase in boundary gas entrainment for P100 (102.8 mg) is 4.2 times that of P0 (24.4 mg). This is further supported by its physical advantages: low kinematic viscosity (1.05 mm2·s−1) and high oxygen content (47.0%). This hierarchy underscores PODE’s potential as a sustainable alternative fuel for diesel engines, as its superior spray behavior can significantly enhance combustion efficiency and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. The promising performance of PODE-blended fuels further illustrates how fuel formulation innovations can drive sustainable energy transitions, supporting the global shift toward cleaner, low-carbon energy solutions and aligning with key sustainable development imperatives related to responsible energy consumption and production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N. and C.S.; methodology, C.S.; software, J.N.; validation, J.N., F.N. and H.W.; formal analysis, F.N.; investigation, J.N.; resources, H.W.; data curation, F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, F.N.; writing—review and editing, C.S.; visualization, J.N.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, C.S.; funding acquisition, C.S., F.N. and H.W. All authors commented on the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52501384), Key Research and Development Program of Henan Province (Grant No. 251111222000), Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (Grant No. E2025203113) and Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department (Grant No. QN2023224).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Alonso-Villar, A.; Davidsdóttir, B.; Stefánsson, H.; Ásgeirsson, E.I.; Kristjánsson, R. Technical, economic, and environmental feasibility of alternative fuel heavy-duty vehicles in Iceland. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.Z.; Pan, J.F.; Fan, B.W.; Nauman, M.; Jiang, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W. Effect of blending ratio and equivalence ratio on combustion process of ammonia/hydrogen rotary engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 274, 126635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.D.; Feng, H.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, W. Investigation research of gasoline direct injection on spray performance and combustion process for free piston linear generator with dual cylinder configuration. Fuel 2021, 288, 119657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Yu, S.W.; Wang, T.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. A systematic review on sustainability assessment of internal combustion engines. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 451, 141996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Paparao, J.; Singh, P.; Kumbhakarna, N.; Kumar, S. A review of recent advances in hydrogen fueled Wankel engines for clean energy transition and sustainable mobility. Fuel 2025, 387, 134334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Huang, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Wei, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, M. Combustion and emission of diesel/PODE/gasoline blended fuel in a diesel engine that meet the China VI emission standards. Energy 2024, 301, 131473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, H.; Panthi, N.; Almanashi, A.; Magnotti, G. Influence of fuel injection parameters at low-load conditions in a partially premixed combustion (PPC) based heavy-duty optical engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 232, 121049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Geng, C.; Dong, J.T.; Li, X.; Xu, T.; Jin, C.; Liu, H.; Mao, B. Effect of diesel/PODE/ethanol blends coupled pilot injection strategy on combustion and emissions of a heavy duty diesel engine. Fuel 2023, 335, 127024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Q.; Qian, Y.; Mi, S.J.; Zhang, T.; Lu, X. Ammonia-PODE dual-fuel direct-injection spray combustion: An optical study of spray interaction, ignition and flame development. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 487, 144647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, C.; Parravicini, M.; Boulouchos, K.; Liati, A. Neat polyoxymethylene dimethyl ether in a diesel engine; part 2: Exhaust emission analysis. Fuel 2018, 234, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Li, W.; Pan, J. Optical study on the auto-ignition and knocking behaviors of ammonia/PODE RCCI mode. Fuel 2025, 381, 133467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.X.; He, X. Improvement of emission characteristics and thermal efficiency in diesel engines by fueling gasoline/diesel/PODEn blends. Energy 2016, 97, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.J.; Wang, X.B.; Miao, H.Y.; Huang, Z.; Gao, J.; Jiang, D. Performance and Emission Characteristics of Diesel Engines Fueled with Diesel-Dimethoxymethane (DMM) Blends. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Tang, Q.; Wang, T.F.; Wang, J. Kinetics of synthesis of polyoxymethylene dimethyl ethers from paraformaldehyde and dimethoxymethane catalyzed by ion-exchange resin. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 134, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.J.; Wang, Z.; You, X.Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; He, X. A chemical kinetic mechanism for the low- and intermediate-temperature combustion of Polyoxymethylene Dimethyl Ether 3 (PODE3). Fuel 2018, 212, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanli, H. Characterizing three generation biodiesel feedstocks: A statistical approach and empirical modeling of fuel properties. Waste Manag. 2025, 200, 114755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvidsten, I.B.; Marchetti, J.M. Securing liquid biofuel by upgrading waste fish oil via renewable and sustainable catalytic technology. Fuel 2023, 333, 126272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamun, S.; Hasimoglu, C.; Murcak, A.; Andersson, Ö.; Tunér, M.; Tunestål, P. Experimental investigation of methanol compression ignition in a high compression ratio HD engine using a Box-Behnken design. Fuel 2017, 209, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyam, A. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel for internal combustion engines: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 82, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musy, F.; Ortiz, R.; Ortiz, I.; Ortiz, A. Hydrogen-fuelled internal combustion engines: Direct Injection versus Port-Fuel Injection. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 137, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Biswal, A.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhao, H.; Hall, J. Experimental investigation for enhancing the performance of hydrogen direct injection compared to gasoline in spark ignition engine through valve timings and overlap optimization. Fuel 2024, 372, 132257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shuai, S. Study on combustion and emission characteristics of Polyoxymethylene Dimethyl Ethers/diesel blends in light-duty and heavy-duty diesel engines. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1393–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcoumanis, C.; Bae, C.; Crookes, R.; Kinoshita, E. The potential of di-methyl ether (DME) as an alternative fuel for compression-ignition engines: A review. Fuel 2008, 87, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, S.E.; Barro, C.; Boulouchos, K.; Burger, J. Combustion behavior and soot formation/oxidation of oxygenated fuels in a cylindrical constant volume chamber. Fuel 2016, 167, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.H.; Gao, Y.X.; Liu, S.H.; Ma, Z.; Wei, Y. Effect of polyoxymethylene dimethyl ethers addition on spray and atomization characteristics using a common rail diesel injection system. Fuel 2016, 186, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.X.; He, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tang, Q.; Wang, J. Performance, combustion and emission characteristics of a diesel engine fueled with polyoxymethylene dimethyl ethers (PODE3-4)/diesel blends. Energy 2015, 88, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Ye, M.Y.; Tian, J.P.; Zhao, H.; Liu, M.; Feng, L. Experimental research on the spray and particle characteristics of cylinder lubricating oil in low-speed two-stroke gas fuel engines. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 119, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, X.Q.; Wang, B.; Guo, T.; Shi, Q.; Zheng, M. Characteristics of non-evaporating, evaporating and burning sprays of hydrous ethanol diesel emulsified fuels. Fuel 2017, 191, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.L.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.F.; Xu, H.; Shuai, S. Experimental investigation on the macroscopic and microscopic spray characteristics of dieseline fuel. Fuel 2017, 199, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.Y.; Yi, B.L.; Fu, W.; Song, L.; Liu, T.; Hu, H.; Lin, Q. Experimental study on spray characteristics of long-chain alcohol-diesel fuels in a constant volume chamber. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, X.; Wu, P.; Yuan, Y. Experiments on combustion and emission particulate size distribution characteristics of diesel engine fuelled with methanol-blending biodiesel fuel. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhong, X.; Mi, S.; Yao, M. Numerical investigation on the combustion characteristics of PODE3/gasoline RCCI and high load extension. Fuel 2020, 263, 116366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Z.; Zhu, Z.J.; Zhu, J.Z.; Lv, D.; Pan, Y.; Wei, H.; Teng, W. Experimental and numerical study of pre-injection effects on diesel-n-butanol blends combustion. Appl. Energy 2019, 249, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakopoulos, D.C.; Rakopoulos, C.D.; Kakaras, E.C.; Giakoumis, E. Effects of ethanol-diesel fuel blends on the performance and exhaust emissions of heavy duty DI diesel engine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.S.; Li, G.X.; Li, H.M.; Huo, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Bai, H. Experimental study on the effects of fuel properties on spray macroscopic characteristics, particle size distribution, and velocity field in a constant volume chamber. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2026, 171, 111602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).