Abstract

While there is very limited information on the cost of production (COP) for the emerging 100% grass-fed organic dairy sector, this study (1) estimates the COP using primary data collected from on-farm surveys, (2) assesses the correlation between COP and key production and management factors, (3) examines how land, feed and labor efficiency, and production scale affect the COP, and (4) derives recommendations for enhancing the economic efficiency of grass-fed organic dairy farms. Data collected via annual surveys in the Northeastern United States from 2019 to 2022 were analyzed through descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, hypothesis tests, and regression analysis. At an average cost of USD 45.91 per hundredweight equivalent of milk, the marginal impacts of the cows managed per full time equivalent labor and milk sold per cow on the COP were −USD 0.166 and −USD 0.003, respectively. Conversely, the COP increased by USD 1.44 when the crop acres per cow increased by one unit, and the COP of small farms with less than 45 cows was USD 6.20 higher than other farms. As farms are significantly different in resource endowment and other factors, the strategies for reducing the COP and improving the economic returns should be identified for individual farms. However, our analyses highlight the importance of enhancing labor efficiency in forage production, land management, milking and feeding, improving herd management and optimizing nutrition and dry matter intake to support high milk productivity. This study may help existing grass-fed dairy farms improve their farm management and reduce COP and help prospective farms assess their suitability for transitioning to grass-fed operation.

1. Introduction

While dairy has been one of the largest agricultural sectors in the United States, many American dairy farms, especially small and medium-sized farms, are struggling to stay in business due to increasing production costs and a downward trend in farmgate milk prices in real terms (i.e., after inflation is adjusted) [1,2,3]. For example, while the average farmgate price per hundredweight (cwt) for Class I milk increased moderately from USD 13.77 in 1980 to USD 17.00 in 2023 [4], the real price in 1980 dollars dropped remarkably from USD 13.77 to USD 4.60 over the period (calculated from the nominal price using the consumer price index data of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [5]).

To overcome these challenges and move towards more sustainable development, the dairy industry is actively seeking innovative strategies in accordance with rapidly changing consumer preferences and market conditions. Many dairy farms have made great efforts to change their production practices to differentiate their milk and meet consumer demand for healthier and more environmentally friendly dairy products such as organic milk and yogurt [6,7,8,9,10]. For example, the total retail sales of organic milk and cream in the United States increased from about USD 1.1 billion in 2005 to USD 4.2 billion in 2023 [11,12]. The rapid growth in the organic dairy markets in the United States is also reflected in the remarkable increase in the number of organic milk cows, from 2265 in 1992 to 352,289 in 2021 [4]. Organic dairy markets have also allowed farmers to capture price premiums for their products. For example, organic milk price received by farmers in New York in 2023 averaged USD 37.73 per cwt, while the average price received by dairy farmers for all milk in the state that year was only USD 21.66 per cwt [13,14]. In addition to organic operations, an increasing number of dairy farms have switched to 100% grass-fed organic operations [15]. In 100% grass-fed organic dairy production systems, cows on certified organic farms are not fed any grain or grain byproducts, and the nutrient needs of the animals are met with grazed and stored forages, minerals, and limited amounts of permitted supplemental non-grain energy sources such as molasses [16]. Note that a 100% grass-based diet is not necessary to be considered organic in the United States. In the rest of this paper, grass-fed refers to 100% grass-fed organic operations as defined above.

Research has shown that grass-fed milk has a significantly different nutritional profile compared to conventional milk [17,18,19,20,21,22,23] which may contribute to many human health benefits, including protecting against oxidative stress, cell damage, inflammation, and promoting cardiovascular health and immune support [24,25,26,27,28]. Consumer demand for grass-fed milk has increased significantly in the past decade due to these perceived health benefits as well as concerns over environmental impacts and sustainability in the industrial food production. For example, the number of grass-fed dairy farms in the United States increased about 400% from 2016 to 2019 [29]. As of August 2025, Organic Valley, the largest grass-fed milk supplier in the United States, had 285 grass-fed dairies across the United States—a metric that had doubled since 2024 [30]. According to the Verified Market Research [31], the grass-fed dairy market in the United States was valued at USD 4.64 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of roughly 6% to reach USD 6.98 billion by 2031. Globally, grass-fed milk market revenue was valued at USD 12.5 billion in 2024 and is estimated to reach USD 20 billion by 2033, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 6.5% over the period [32].

Despite interest in both consumption and production of grass-fed milk, economics may be a restrictive factor for both consumers and producers limiting future industry growth. Currently retail costs of certified 100% grass-fed milk are between 50% and 100% higher than certified organic milk and over 200% higher than conventional milk. These higher retail prices reflect higher production costs which may be related to differences in milk productivity, feed production costs, land needs, and labor efficiency [33,34].

Understanding the major factors influencing the cost of producing grass-fed milk is crucial not only for producer economic viability but reducing retail prices to expand consumption. This study focuses on the COP rather than the profit due to three considerations: First, while COP is determined by many internal and individual factors and revenue is the result of many external factors, focusing on the COP provides a more direct way for farmers to analyze their cost components as compared to their peers and identify actionable ways to reduce their COP with more predictable impacts. Second, although dairy farms are significantly different in resource endowment and many other factors, they face very competitive markets and the variation in their profit is basically determined by their milk productivity and COP. Third, information on the COP can help consumers understand why grass-fed milk is more expensive than conventional and organic milk and appreciate farmers’ efforts.

This study is motivated by the significant development of the grass-fed dairy sector in the United States and many other countries and the lack of information on the COP of grass-fed milk and its contributing factors in the existing literature. Specifically, this study will address the following research questions through empirical analysis of primary data collected from a farm survey: (1) How do farm management and production practices influence the COP for grass-fed milk? (2) What are some potential strategies for grass-fed dairy farms to enhance their production efficiency and economic viability? Answering these questions is expected to help enhance the economic viability of the existing grass-fed dairy farms, informing farmers who are considering starting grass-fed operations, and helping consumers understand and appreciate the reasons behind the higher price of grass-fed milk.

2. Data and Methods

In 2019, 2020, and 2022, farm financial data were collected from grass-fed dairy farms in the northeast region, primarily New York and Vermont. Only farms that were 100% grass-fed organic and selling wholesale milk were selected. Data was collected during visits to the farms using the Dairy TRANS 20.20 tool [35]. This tool is an Excel-based workbook developed by Iowa State University Extension that translates farm-level data inputs into summaries including (1) a balance sheet that provides a snapshot of beginning and ending values of the farm on a fair market value and/or cost, (2) farm cash incomes and expenses taken from farmer’s financial records which contain more detail than those taken directly from the tax form Schedule F, (3) non-farm income, income taxes paid, capital purchases, and sales, and (4) production data with milk output, number of cows, productive crop/pasture acres, opportunity costs of labor and equity, unpaid labor hours, and fulltime labor equivalents (1 FTE = 3000 h).

To allow for more equal comparisons between farms with different debt loads and dependence on the dairy enterprise to cover living expenses, the tool assumes several standardizations: (1) farms’ actual asset (market) value, income, and all expenses other than interest are included, (2) an unpaid labor charge of USD 40,000 per owner operator and per additional FTE unpaid is applied, (3) inventory change adjustments to factor in changes in herd size or equipment inventory and value are included, (4) a 4% charge on the farm’s assets is included instead of interest payments, and (5) dairy-related non-milk income (e.g., crop sales, calf sales, etc.) is converted into an equivalent weight of milk which is then added to the total weight of milk sold and is referred to as hundredweight equivalents (cwt eq.). This is performed to account for the expenses associated with producing the dairy-related non-milk incomes that cannot accurately be separated from the expenses to produce milk. This tool was selected due to its simultaneous simplicity and comprehensive assessment of the factors of the total cost of production as well as its suitability for research applications through the standardizations and familiarity among farmers in the region due to prior uses.

Financial data was collected by one individual to decrease variability. Farms were contacted primarily by mail and phone due to the high proportion of Plain community farmer participants who do not use computers. Data was collected primarily via in-person interviews; however, some were collected over the phone once a farm had participated for several years and was familiar with the process. Data were input directly into the Dairy -Trans tool as they were collected. Data collected includes the following: (1) a modified balance sheet for market value of farm assets, feed and cattle inventory, and farm acreage, (2) quantity of milk, livestock, and crops sold and their respective farm incomes, (3) all dairy farm expenses except interest payments, and (4) farm labor hours for both paid and unpaid labor. Farm liability data were not collected.

The production and financial data from the Excel-based DairyTrans 20.20 [35] together with farm demographic data were analyzed in Stata SE 17.0 and SPSS 29 through descriptive statistics, correlation analysis and hypothesis tests, and regression analysis.

Descriptive statistics were generated for the whole sample over three years to summarize and describe the key variables of the dataset (e.g., mean, standard deviation, minimum value, maximum value, frequency, etc.). Such statistics provide a clear and concise overview of the data. For example, the average values of COP by year, region, and farmer groups and their variations provide highly needed information for dairy farms, extension specialists, researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders of the grass-fed dairy sector. Correlation analysis and hypothesis tests were conducted to identify potential relationships between COP and key farm production and management factors as well as farm demographics. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated, and alternative hypotheses were tested at the 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 significance levels to address several research questions. Regression analysis was used to identify the major factors affecting the COP and quantify each factor’s marginal impact on the COP when other factors are controlled. Specifically, the following linear regression model was estimated to examine the impacts of four groups of factors: land efficiency, output efficiency, labor efficiency, and farm demographics,

where Yij is the COP per cwt eq. of farm i in year j, X1ij, X2ij, X3ij, …, Xijn are the values of n independent variables of farm i in year j, a is the intercept, b1, b2, b3, …, bn are the corresponding coefficients to be estimated, and eij is the error term. Alternative specifications of this linear regression model were estimated with different combinations of independent variables.

While the overall goodness of fit of each estimated regression model was measured by R-squared and adjusted R-squared and tested via the F-test, each estimated coefficient is tested for its significance level.

3. Empirical Results

This section first reports the descriptive statistics, including the estimated COP, then presents the results of correlation analysis and hypothesis tests, and finally reports the estimated regression models. Note that some interpretation and explanation of the empirical findings are based on the authors’ field observations and communication with many grass-fed dairy farms over several years.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

While the primary data collected from the surveys were recorded in Excel and then processed in STATA for statistical analysis, the descriptive statistics for numerical variables and categorical variables are reported in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the dataset.

Table 2.

Farm demographic and management information.

The overall COP per cwt eq. averaged USD 45.91, with a wide range from USD 25.51 to USD 92.38. Farms managed, on average, 346 acres for pasture and stored forage production with an average herd size of 62 cows, resulting in an average of 5.5 acres per mature cow. While the acres per cow varied greatly from 1.71 to 11.65, this large range indicates different production models: some farms were managing very small land bases of primarily pasture and purchasing all their stored forage needs while other farms were managing both pasture and hay land to produce stored forage. Similarly, some farms opted to purchase supplementary energy in the form of molasses, while other farms relied only on forages to meet cow energy requirements. This is also evidenced by the wide range in molasses costs from USD 0 to USD 4.81 per cwt eq.

As Snider et al. [15] indicated, a substantial proportion of grass-fed dairy producers (64%) nationally identify as Plain sect community members (e.g., Amish, Mennonite, etc.). Because these religious beliefs can influence management practices and access to information, this information was collected in the survey. This dataset hosts a smaller proportion (39.06%) of Plain sect community farmers than that of Snider et al. [15]. The term English is used to distinguish farmers who do not identify as Plain sect community members. While most participating farms (70.31%) milked year-round, there were some fully seasonal herds (29.70%). Additionally, most farms (79.03%) milked twice daily while few herds milked once per day (16.13%) or three times every two days (4.84%).

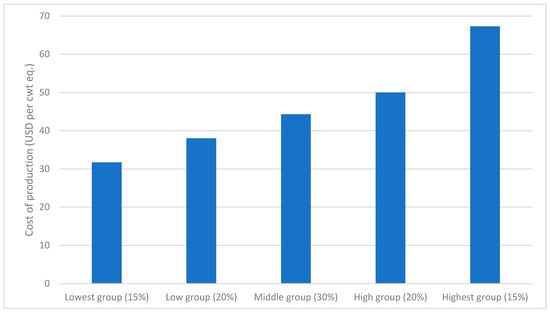

While COP varied significantly among the farms in the dataset, Figure 1 reports COP by five groups defined by their percentiles of COP, from the 15% with the lowest COP to the 15% with the highest COP. While the average COP for the lowest group and the highest group were, respectively, USD 31.70 per cwt eq. and USD 67.30 per cwt eq., the majority (70% or 45 farms) had a COP between USD 38.00 and USD 50.00 per cwt eq.

Figure 1.

Distribution of farms by their COP.

3.2. Correlation Analysis and Hypothesis Tests

Correlation analysis was conducted to identify potential relationships between COP and key farm production and management factors. This allows for the identification of management or other factors that are highly associated with increasing or decreasing COP. As reported in Table A1 in the Appendix A, positive correlations were identified between COP and land per cow (r = 0.3751, p = 0.0021), fuel expense (r = 0.6365, p < 0.0001), supply expense (r = 0.3422, p = 0.0053), repair expense (r = 0.4642, p = 0.0001), and molasses expense (r = 0.6107, p = 0.0002). These indicate that increasing acreage and expenses relating to forage production and energy supplementation significantly increase production costs in grass-fed dairy operations.

Conversely, negative correlations were identified between COP and labor earnings (r = −0.6473, p = 0.0000), milk sold per cow (r = −0.5545, p = 0.0000), herd size (r = −0.2710, p = 0.0201), and cows managed per FTE (r = −0.2912, p = 0.0186). The inverse relationships between COP, milk sold per cow, and herd size suggest that enhanced milk production efficiency per cow and increased herd size are linked with diminished production costs, thereby emphasizing the benefits of increased productivity per animal and per farm on cost reduction. However, it should be recognized that milk sold does not equate to milk production. A large portion of milk produced may be utilized to raise youngstock on the farm and therefore may contribute to lower milk sales. Additional information on milk diverted to youngstock rearing was not available for all years in this dataset and therefore cannot be fully explored here. However, preliminary data from 2023 show that, on average, grass-fed farms fed 24.07 cwt of milk per calf and raised an average of 17 calves per farm per year with an average milking herd size of 62. Therefore, while milk sold per cow averaged 84.65 cwt, total milk produced per cow averaged 92.50 cwt. While future data collection of this nature will allow for a more robust analysis of these factors, animal production efficiency is clearly a critical factor in lowering farm COP. In addition, the negative relationships between COP, cows managed per FTE, and labor earnings per hour indicate that labor efficiency is a critical determinant of COP and profitability on grass-fed dairy farms.

One-tailed t-tests were conducted to investigate the difference in COP and other variables between groups of farms utilizing different management practices in terms of buying forage vs. producing forage, supplementing energy or not, and year-round twice daily milking vs. alternative milking schedules. First, since fuel costs and other cash expenses related to forage production were highly correlated to COP, a comparison was made between farms that were producing most of their stored forages and farms that were buying most of their stored forages. This was determined by the purchased forage expense per cow where farms spending less than USD 30 per cow were assigned to the ‘producing forage’ group. Upon conducting a one-tailed t-test between these groups, the results, reported in Table 3, are statistically significant for all variables included in the table, which are indicative of operational and economic aspects of farming practices. The variables in Table 3 were selected due to their association with producing stored forages and their influence on COP.

Table 3.

t-test of the mean difference for producing forage vs. buying forage.

Farms producing most of their stored forage needs managed 2.38 more acres per cow and incurred higher production costs than farms purchasing most of their forage needs. Similarly, individual expense categories related to making forage were higher for the ‘producing forage’ group including supplies, fuel, and repairs. These indicate substantial production cost differences between these two management paradigms. Like many other agricultural sectors, specialization in forage production may provide economies of scale, especially relative to labor. Reliance on more resource-efficient equipment and specialization of labor could be contributing to generally lower forage prices on the market compared to realized feed production costs on grass-fed dairy farms. Furthermore, differences in quality of the forages made on-farm or purchased off-farm could also impact milk production and thus sales which is highly negatively correlated to COP. In addition, “producing forage” farms earned less per hour influenced by their lower milk productivity. As these differences could reflect variations in labor economics, scales of operation, herd management, feeding practices, forage quality, or genetic selection, more information is needed to fully understand the underlying causes of these differences.

Second, as reported in Table 4, the farms that supplemented energy were significantly different from their counterparties in terms of COP and several other variables. Supplying additional energy to the animals would be expected to increase milk productivity, therefore COP and milk sold per cow were the primary variables investigated in this comparison. Farms feeding supplemental energy had substantially higher production costs with no statistical difference in milk sold per cow. It is possible that differences in the quality of forages fed in the two groups could explain the lack of increase in milk sales. Reliance on poorer quality forages and energy supplementation at the levels used by these farms may represent a smaller increase in milk sales than feeding higher quality forages without supplemental energy. Without information on the quality of forages or quantity of molasses fed, this cannot be elucidated. It is also possible that farms supplementing energy produced more milk, but the additional milk was diverted to feed youngstock and therefore is not reflected in milk sales. Information on youngstock rearing would be needed to further explore this possibility. Regardless, energy supplementation appears to be a significant driver of COP for grass-fed dairy farms, and more information on the economics of feeding supplemental energy is needed to aid producer decision-making.

Table 4.

t-test of the mean difference for supplementing energy vs. not supplementing energy.

Third, while most grass-fed dairy farms milk twice daily and calve year-round [15], some grass-fed farms are interested in milking less than twice daily or seasonally calving to control labor costs and other on-farm resources. Since altering milking frequency can impact milk production and expenses, these variables were selected along with COP in this comparison. In this dataset, the overall cost of producing milk and cash expenditures per cow did not differ statistically between farms utilizing a typical year-round calving twice daily milking schedule and those using an alternative schedule (Table 5). While farms using alternative schedules were significantly more labor efficient, managing 10 cows per FTE more than the traditional schedule farms, labor earnings per hour were numerically different but statistically similar between the two groups. This is likely due to the alternative schedule farms selling significantly less milk per cow and potential variation in milk price.

Table 5.

t-test of the mean difference for year-round 2X vs. other schedules.

3.3. Regression Results

While the correlation analysis and hypothesis tests reported in the previous subsection provided important information on how the selected variables are correlated in terms of both the direction and degree of correlation, regression analysis provides information on the causality relation as well as the impact of each independent variable on the dependent variable (COP) while holding other variables constant. In our analysis, two regression models are estimated to identify the factors that determine the COP and quantify the marginal impact of each factor while other factors are controlled or held constant. While Model 1 includes four major variables addressing three factor groups as previous discussed, Model 2 includes those variables plus three dummy variables for demographic factors including English vs. Plain status and production scale (herd size). For the four major variables, the land per cow and seed and fertilizer expense per acre represent land utilization efficiency, excluding forage value variations due to purchase differences; the cows per FTE reflects labor efficiency, with its inclusion aimed at isolating its impact on costs while accounting for factors such as experience and community identity in further analyses; and milk sold per cow serves as a direct indicator of output efficiency, allowing for the assessment of cost influences attributable to animal productivity alone, while controlling for additional variables like purchased energy and milking frequency in extended analysis. The estimation results of the two regression models are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Estimation results of two regression models.

The empirical results suggest four major findings: First, the estimated models fit the relatively small dataset well and explain 41.4% of the variation in COP in Model 1 and 45.8% of the variation in COP in Model 2. The F-statistic and its p-value for the two models also suggest that we are 99% confident that the variation in the COP is affected by the independent variables included in the models. Second, regarding the estimated coefficients and their significance levels for the four major independent variables, milk sold per cow showed a negative and significant impact on the COP at the 0.01 significance level in both models; land per cow had a positive impact on the COP at the 0.10 significance level; per acre seed and fertilizer expense showed a positive but insignificant impact; and cows per FTE had a negative impact but was only significant in Model 1. Third, for the two dummy variables for farm size, while small farms (<45 cows) had significantly higher COP at the 0.05 significance level, large farms (>70 cows) had lower COP but it was not statistically significant at the 0.10 significance level. Regarding the dummy variable for English farms, they had higher COP as compared to the COP of Plain farms, but the difference was not statistically significant at the 0.10 significance level. Fourth, the relatively small absolute values of the estimated coefficients of the independent variables suggest that the COP is determined by this set of variables together and the marginal impact of each individual variable is small when other variables are controlled. For example, when the land per cow increases by one acre, the COP is expected to increase by only USD 0.987 according to Model 1 and USD 1.43 according to Model 2, when other variables in each model are held constant. The relatively small marginal impacts of the independent variables suggest that, while each factor influences COP, their individual impacts are relatively small compared to their combined effect when controlling for other factors. In application, this finding suggests that farms need to pay attention to all the factors simultaneously to control their COP.

Like many other empirical studies, this study is limited by the small dataset with only 64 observations (22 from 2019, 21 from 2020, and 21 from 2022) and the empirical results from the data analysis should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, the methods used to calculate COP were chosen to facilitate comparisons across farms with differing debt loads, family living draws, and other external factors that influence COP but are not directly related to farm management. While this allows for investigation into management factors’ influences on COP generally, the COP values presented here may not reflect the true experience of some farmers and therefore should be used with caution outside of this context. Another limitation is that some potentially important variables affecting the COP were not included in the regression analysis due to the lack of available data or multicollinearity concerns. Finally, there is the inherent challenge in standardizing farms for comparison. All farms are uniquely different, and while DairyTrans was a necessary tool for creating comparability, the standardization process can never fully account for all farm-level differences. Since there are very limited studies on grass-fed dairy, as it is a relatively new sector in the literature, it is a challenge to compare and validate findings from this study or to discuss to what extent the findings from this can be applied to other regions.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

As one of the first empirical studies on the COP of grass-fed dairy in the Northeastern United States, this study suggests three major conclusions. First, COP varies widely from USD 25.51 to USD 92.38 with an average of USD 45.91. The cost to produce grass-fed milk appears to be substantially higher than that of conventional and organic production models. Second, COP is highly positively correlated with acres per cow and key expense categories including fuel, supplies, repairs, and supplemental energy. COP is negatively correlated with the quantity of milk sold per cow, cows managed per FTE, and labor earnings per hour. Farms producing their own stored forages had significantly higher COP, acres per cow, and expenses related to forage production including fuel, supplies, and repairs. Farms feeding supplemental energy also had significantly higher COP and did not sell more milk. Farms using alternative milking strategies were more labor efficient but had similar COP due to lower milk sales. These suggest that farm acreage, herd size, cow production efficiency, and labor efficiency highly influence COP. This was further supported by regression analyses that found that over 45% of the variation in COP can be explained by these factors.

While many grass-fed dairy farms are actively searching for information and strategies to enhance their production efficiency and economic viability, this study suggests four major recommendations based on the data analyses as well as field observations of grass-fed farm operations and communication with many farms: (1) optimize the number of replacements being raised to maximize milk sales from milk produced, (2) enhance milk productivity per cow by optimizing cow nutrition, reproductive performance, comfort, and health to aid in maximizing milk sales, (3) invest in labor efficiency enhancements in milking, feeding, and other aspects of farm management to maximize output relative to labor resources, and (4) optimize acreage to balance high-quality forage production with available economic, labor, and other resources. Future COP studies will collect additional management data to better elucidate the impacts of specific farm management factors and practices on COP and farm profitability. In addition, existing grass-fed farmers need access to technical assistance to help calculate their own farms’ COP to inform management decisions that enhance farm viability. Furthermore, prospective grass-fed dairy farmers need access to technical assistance to understand whether they are able to transition to this production model successfully and if it will support farm viability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D., S.Z., Q.W. and S.F.; Methodology, Q.W., S.Z. and H.U.; Validation, S.Z. H.U. and A.A.; Formal analysis, H.U., Q.W. and S.Z.; Resources, H.D., S.F. and S.Z.; Data curation, S.F. and S.Z.; Writing—original draft, S.Z. Q.W., S.F. and H.U.; Writing—review and editing, S.Z., Q.W., A.A., S.F., H.U. and H.D.; Supervision, S.Z., Q.W. and H.D.; Funding acquisition, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative (OREI) (Grant award number 2023-51300-40985 and 2018-51300-28515).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board (protocol code 00000036 and date of approval 12 December 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. We also would like to thank other members of our research team for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Sarah Flack has been employed by Sarah Flack Consulting. The remaining authors are employed by the University of Vermont and declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the government funding organization had no direct involvement with the study.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Correlation matrix.

Table A1.

Correlation matrix.

| Cost of Production (USD/cwt eq.) | Land per Cow (acres/cow) | Seed and Fertilizer Expense (USD/acre) | Labor Earning (USD/hour) | Milk per Cow (cwt eq./cow) | Cost of Molasses (USD/cwt eq.) | Cost of Supplies (USD/cwt eq.) | Fuel Cost (USD/cwt eq.) | Repair Cost (USD/cwt eq.) | Total Cash Expense (USD/cow) | Herd Size (cows) | Cows per FTE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of production (USD/cwt eq.) | 1 | |||||||||||

| Land per cow (acres/cow) | 0.3751 ** (0.1178) | 1 | ||||||||||

| Seed and fertilizer expense (USD/acre) | −0.1509 (0.1254) | −0.2672 ** (0.1228) | 1 | |||||||||

| Labor earning (USD/hour) | −0.6473 *** (0.0980) | −0.3010 ** (0.1211) | −0.0400 (0.1268) | 1 | ||||||||

| Milk per cow (cwt eq./cow) | −0.5545 *** (0.1052) | −0.3335 *** (0.1197) | 0.1224 (0.1260) | 0.2234 *** (0.1238) | 1 | |||||||

| Molasses cost (USD/cwt eq.) | 0.6107 *** (0.1008) | 0.3482 *** (0.1190) | 0.1062 (0.1263) | −0.4501 *** (0.1134) | −0.3480 *** (0.1191) | 1 | ||||||

| Supply cost (USD/cwt eq.) | 0.3422 *** (0.1193) | 0.3253 *** (0.1201) | −0.1165 (0.1261) | −0.2887 ** (0.1216) | −0.3196 ** (0.1203) | 0.4333 ** (0.1144) | 1 | |||||

| Fuel cost (USD/cwt eq.) | 0.6365 *** (0.0981) | 0.4559 *** (0.1130) | −0.1542 (0.1254) | −0.3200 *** (0.1203) | −0.3260 *** (0.1201) | 0.4063 ** (0.1160) | 0.2204 * (0.1239) | 1 | ||||

| Repair cost (USD/cwt eq.) | 0.4642 *** (0.1138) | 0.3681 *** (0.1181) | 0.0782 (0.1266) | −0.3973 *** (0.1165) | −0.4826 *** (0.1112) | 0.5021 *** (0.1098) | 0.3408 ** (0.1194) | 0.2918 ** (0.1215) | 1 | |||

| Total cash expense (USD/cow) | 0.0178 (0.1269) | −0.0706 (0.1267) | 0.2305 * (0.1236) | −0.2702 ** (0.1222) | 0.5300 *** (0.1069) | 0.1715 (0.1251) | 0.0987 (0.1263) | −0.0363 (0.1269) | 0. 0675 (0.1267) | 1 | ||

| Herd size (cows) | −0.2710 ** (0.1222) | 0.0300 (0.1269) | 0.4104 *** (0.1154) | 0.1402 (0.1256) | −0.0095 (0.1269) | −0.0523 (0.1268) | −0.0223 (0.1269) | −0.0808 (0.1265) | 0.0943 (0.1263) | 0. 0203 (0.1269) | 1 | |

| Cows per FTE | −0.2912 ** (0.1220) | −0.0913 (0.1265) | 0.2630 ** (0.1225) | 0.4140 *** (0.1156) | −0.0841 (0.1266) | −0.0746 (0.1266) | 0.0200 (0.1269) | −0.1316 (0.1259) | 0.0520 (0.1268) | −0. 0001 (0.1269) | 0.6812 *** (0.0925) | 1 |

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

References

- Walsh, J.; Parsons, R.; Wang, Q.; Conner, D. What makes an organic dairy farm profitable in the United States? Evidence from 10 years of farm level data in Vermont. Agriculture 2020, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, C.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Kitsos, A.; Cannella, M.; Wang, S.-K.; Han, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the dairy industry: Lessons from China and the United States and policy implications. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2903–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.M.; Law, J.; Mosheim, R. Consolidation in U.S. Dairy Farming (ERS Report No. 274); U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://ers.usda.gov/sites/default/files/_laserfiche/publications/98901/ERR-274.pdf?v=65010 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Marketing Service. Dairy Market News at a Glance. Dairy Market News, 11–15 November 2024. Available online: https://mymarketnews.ams.usda.gov/filerepo/sites/default/files/2998/2024-11-15/1172059/ams_2998_00251.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index. U.S. Department of Labor; 2024. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. Advertised Prices for Dairy Products at Major Retail Supermarket Outlets ending during the period of 9/19/2025 to 9/25/2025. Dairy Market News, 14 November 2025. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/mnreports/dybretail.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Brito, L.; Bedere, N.; Douhard, F.; Oliveira, H.; Arnal, M.; Peñagaricano, F.; Schinckel, A.; Baes, C.; Miglior, F. Review: Genetic selection of high-yielding dairy cattle toward sustainable farming systems in a rapidly changing world. Animal 2021, 15, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, N.; Garnett, T.; Lorimer, J. Dairy intensification: Drivers, impacts and alternatives. Ambio 2020, 49, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozari, H.; Szmelter-Jarosz, A.; Ghahremani-Nahr, J. The Ideas of Sustainable and Green Marketing Based on the Internet of Everything—The Case of the Dairy Industry. Futur. Internet 2021, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiano, A.; Harwood, W.; Gerard, P.; Drake, M. Consumer perception of the sustainability of dairy products and plant-based dairy alternatives. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11228–11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitri, C.; Nehring, R. Thirty years of organic dairy in the United States: The influences of farms, the market and the organic regulation. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Trade Association. Organic Trade Association Pegs Sales of Organic Products Near $70 Billion [Press Release]. 2024. Available online: https://ota.com/about-ota/press-releases/us-organic-marketplace-posts-record-sales-2023 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Hochul, K.; Ball, R.A. New York State Dairy Statistics 2023 Annual Summary. 2023. Available online: https://agriculture.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2024/07/2023dairystatisticsannualsummary.pdf#:~:text=New%20York%20State%20has%20nearly,state%20in%20the%20United%20States (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- MacKenzie, M.K.; Karszes, J. New York Organic Dairy Cost of Production: Benchmarks and Financial Performance 2023. 2024. Available online: https://dyson.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2024/07/E.B._2024-04_Organic_Financial_Performance-VD.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Snider, M.A.; Ziegler, S.E.; Darby, H.M.; Soder, K.J.; Brito, A.F.; Beidler, B.; Flack, S.; Greenwood, S.L.; Niles, M.T. An overview of organic, grassfed dairy farm management and factors related to higher milk production. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Plus Trust Inc. OPT Certified Grass-Fed Organic Livestock 2025 Program Manual. 2025. Available online: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/7dfcba80-cf7b-4ce3-a4de-b2df6219663c/downloads/487d3c3d-3fd1-4131-8ff5-89cc9429442d/Program%20Manual_OPT%20Certified%20Grass-fed%20v5.0_20.pdf?ver=1754330482891 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Alothman, M.; Hogan, S.A.; Hennessy, D.; Dillon, P.; Kilcawley, K.N.; O’donovan, M.; Tobin, J.; Fenelon, M.A.; O’callaghan, T.F. The “Grass-Fed” milk story: Understanding the impact of pasture feeding on the composition and quality of bovine milk. Foods 2019, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, S.; Provenza, F.D.; Kronberg, S.L. Health-promoting phytonutrients are higher in grass-fed meat and milk. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 555426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgersma, A. Grazing increases the unsaturated fatty acid concentration of milk from grass-fed cows: A review of the contributing factors, challenges and future perspectives. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 1345–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammone, M.A.; Riccioni, G.; Parrinello, G.; D’orazio, N. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Benefits and endpoints in sport. Nutrients 2019, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, B.; Fedele, V.; Ferlay, A.; Grolier, P.; Rock, E.; Gruffat, D.; Chilliard, Y. Effects of grass-based diets on the content of micronutrients and fatty acids in bovine and caprine dairy products 20. In Proceedings of the General Meeting of the European Grassland Federation, Luzern, Switzerland, 21–24 June 2004; Available online: https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02760385 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Șanta, A.; Mierlita, D.; Dărăban, S.; Socol, C.T.; Vicas, S.I.; Șuteu, M.; Maerescu, C.M.; Stanciu, A.S.; Pop, I.M. The effect of sustainable feeding systems, combining total mixed rations and pasture, on milk fatty acid composition and antioxidant capacity in Jersey Dairy cows. Animals 2022, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strusińska, D.; Antoszkiewicz, Z.; Kaliniewicz, J. The concentrations of β-carotene, vitamin A and vitamin E in bovine milk in regard to the feeding season and the share of concentrate in the feed ration. Rocz. Nauk. Pol. Tow. Zoot 2010, 6, 213–220. Available online: https://publisherspanel.com/api/files/view/2364738.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Benbrook, C.M.; Davis, D.R.; Heins, B.J.; Latif, M.A.; Leifert, C.; Peterman, L.; Butler, G.; Faergeman, O.; Abel-Caines, S.; Baranski, M. Enhancing the fatty acid profile of milk through forage-based rations, with nutrition modeling of diet outcomes. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, G.; Nielsen, J.; Larsen, M.; Rehberger, B.; Stergiadis, S.; Canever, A.; Leifert, C. The effects of dairy management and processing on quality characteristics of milk and dairy products. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2011, 58, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, C.A.; Abbott, A.; Doyle, P.S.; Nader, G.A.; Larson, S. A review of fatty acid profiles and antioxidant content in grass-fed and grain-fed beef. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’callaghan, T.F.; Hennessy, D.; McAuliffe, S.; Kilcawley, K.N.; O’donovan, M.; Dillon, P.; Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Effect of pasture versus indoor feeding systems on raw milk composition and quality over an entire lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9424–9440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwendel, B.; Wester, T.; Morel, P.; Tavendale, M.; Deadman, C.; Shadbolt, N.; Otter, D. Invited review: Organic and conventionally produced milk—An evaluation of factors influencing milk composition. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 721–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niles, M.T.; Darby, H.; Flack, S.; Ziegler, S.; Brito, A.; Snider, M. Grass-Fed Dairy Farm Production Practices and Demographics in the US. University of Vermont. 2019. Available online: https://www.uvm.edu/d10-files/documents/2024-10/SurveyArticleFinal.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- McMullen, E. (Organic Valley, Lafayette, WI, USA). Personal communication, 12 August 2025.

- U.S Grass Fed Dairy Market Size by Product Type (Milk, Cheese), by Application (Food and Beverages, Nutraceutical), by Distribution Channel (Indirect, Direct) and Forecast. Verified Market Research. 2025. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/us-grass-fed-dairy-market (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Global Grass-Fed Milk Market Size by Product Type (Whole Grass-Fed Milk, Reduced-Fat Grass-Fed Milk), by Packaging Type (Plastic Bottles, Glass Bottles), by Distribution Channel (Supermarkets/Hypermarkets, Convenience Stores), by End-User (Households, Restaurants/Cafes), by Nutrition Profiles (High Nutritional Value (Omega-3 and Vitamins) Standard Nutritional Value), by Geographic Scope and Forecast. Verified Market Reports. 2025. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketreports.com/product/grass-fed-milk-market/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- UVM Extension NW Crops & Soils. Cost of Production on Organic and Grass-Fed Dairy Farms [Video]. YouTube, 4 March 2022. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=df3jtrGAlFA (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Darby, H.; Flack, S.; Ziegler, S. 2023 Cost of Production on Grass-Fed Dairy Farms in the Northeast. University of Vermont Extension Northwest Crops and Soils Program. 2024. Available online: https://vip2.uvm.edu/d10-files/documents/2025-04/2023-COP-article.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Tranel, F. Dairy TRANS 20.20; A Software for Dairy Farm Financial Analysis; Iowa State University Extension: Ames, IA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).