1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterized by rapid technological advancements and automation, has intensified global demand for skilled labour. Widening skill mismatches constrain productivity and inclusive growth, underscoring the need to cultivate adaptive, innovation-ready human capital [

1]. In this setting, Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) has emerged as a central policy instrument for aligning workforce capabilities with evolving industrial needs. Where TVET is well designed and industry-aligned, systems improve employment outcomes, enhance firm productivity, and support sustainable transformation [

2]. International experience is instructive: coordinated dual systems such as those in Germany and South Korea support industrial competitiveness and smooth school-to-work transitions, while more market-led arrangements in Anglo-Saxon and Nordic countries must continuously address issues of quality, relevance and integration with green strategies [

3,

4]. However, common problems persist, including structural underinvestment, misalignment between training content and labour demand, and unequal access to high-quality programs, particularly in developing regions [

5]. Even advanced economies must continuously refresh curricula with industry to remain relevant in fast-moving technological environments [

6].

In China, the pursuit of High-Quality Development (HQD) elevates vocational education to a strategic priority. Coastal provinces leverage dense industrial clusters and enterprise partnerships to integrate vocational training with advanced manufacturing. In contrast, many central and western provinces face persistent constraints, including limited funding, infrastructure gaps, and pronounced urban–rural disparities, which restrict graduates’ access to value-added employment and social mobility [

7]. Rapid digitalisation offers tools to match evolving skill needs better and update curricula in real time, but doing so in China still requires effective coordination among regulators, providers, and employers [

8,

9].

Although prior studies have examined vocational education, regional development, multidimensional sustainability, and even non-linear investment behaviour, they typically address these elements in isolation. As a result, there is limited integrated empirical evidence that simultaneously evaluates development quality, entrepreneurial and structural upgrading channels, and non-linear conditions within a single, province-level panel framework. The need, therefore, is not for new theoretical constructs but for a coherent empirical assessment that brings these components together within a consistent analytical design.

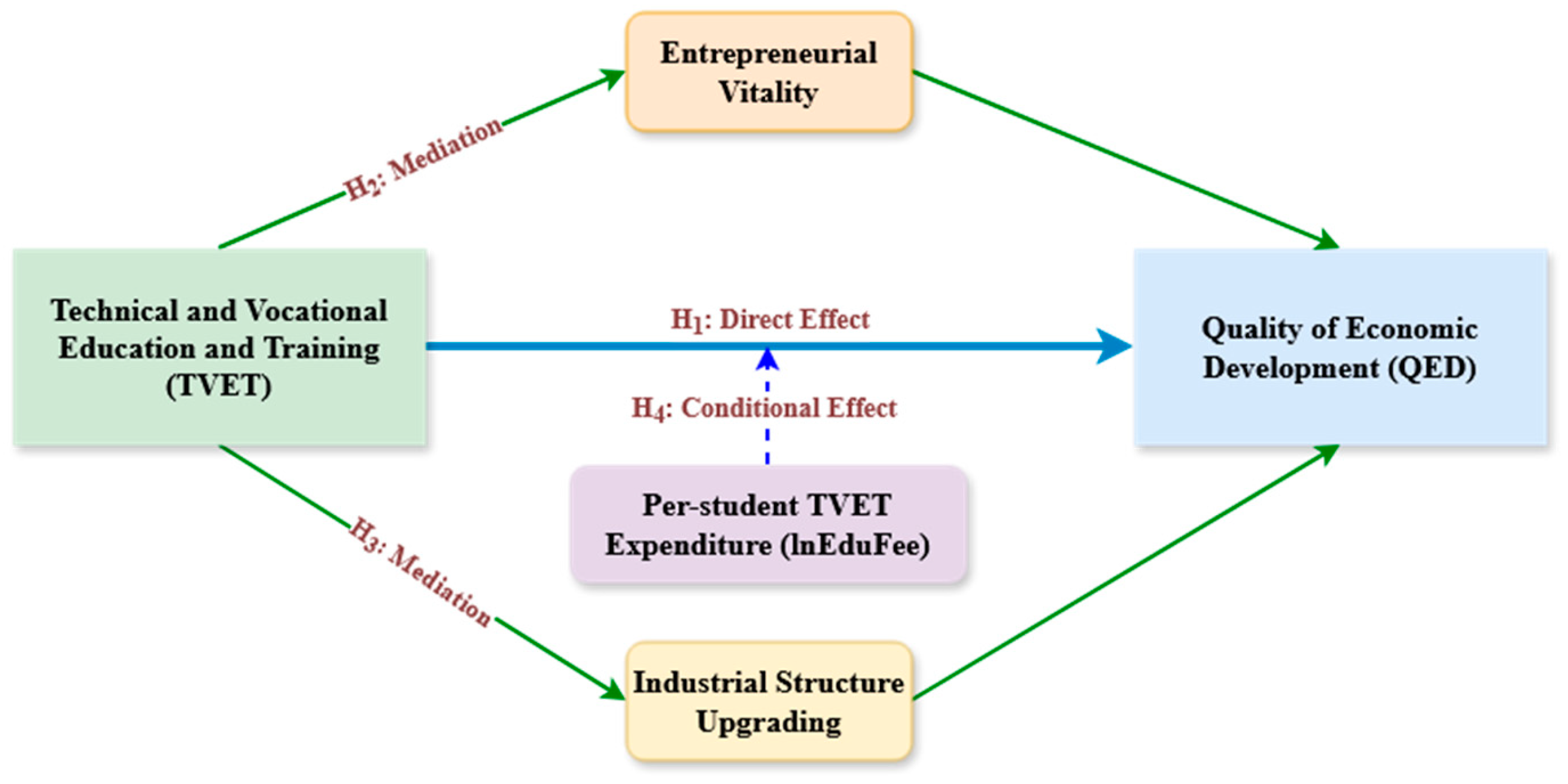

This study responds to the need for an integrated empirical approach. First, we apply a multidimensional QED measurement framework consistently across provinces and years to construct a comparable panel. Second, we examine how TVET operates through two well-recognised development channels, entrepreneurial vitality and industrial structure upgrading, within a unified mechanism model rather than treating them separately. Third, we quantify non-linearities by estimating province-level funding thresholds using a panel threshold regression design. China offers an empirically rich environment for such analysis, given marked provincial differences in TVET investment, industrial maturity, and fiscal capacity, which allow established mechanisms to be tested under heterogeneous conditions. Our study does not assume that China is theoretically unique; rather, its pronounced provincial variation provides a suitable empirical environment for testing how established mechanisms perform under heterogeneous conditions.

To clarify the study’s empirical contribution, this analysis integrates several components that are typically examined separately in prior work. First, although multidimensional measures of development quality exist, our contribution lies in applying a consistent, entropy-based QED index across all provinces and years in a long balanced panel, ensuring comparability and reducing the heterogeneity that arises when indicators or weighting schemes vary across studies. Second, while entrepreneurship and industrial upgrading are well-recognised mechanisms in the literature, they are commonly analysed in isolation; here, we estimate them jointly within a unified mediation framework, thereby quantifying their complementary roles in the TVET–QED relationship. Third, although non-linear returns to education investment are theoretically established, few studies identify where such thresholds lie within vocational education systems; by estimating two statistically significant funding cut-offs, this study provides empirical insight into how marginal returns to TVET development shift across investment regimes. Together, these contributions position the study as an integrated empirical assessment that uses established analytical methods to generate coherent evidence on how TVET affects the quality of economic development across heterogeneous provincial conditions.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 4 reports summary statistics for the balanced panel of 30 provinces (2013–2023; N = 330). All variables exhibit ample cross-provincial and over-time dispersion, which is appropriate for two-way fixed-effects identification. The dependent variable, lnQED, shows meaningful spread (M = 0.147, SD = 0.070), indicating heterogeneity in development quality across provinces. The core regressor, lnTDI, also varies appreciably (M = 0.296, SD = 0.064), consistent with uneven TVET system maturity. lnEV is notably dispersed (M = 1.522, SD = 1.723; SD > M), reflecting concentration of entrepreneurial activity in a subset of provinces, while lnISU also shows broad variation (M = 1.559, SD = 0.881), in line with differential structural upgrading. The threshold driver, lnEduFee, exhibits substantive variance (M = 9.539, SD = 0.451), motivating the search for expenditure cut-offs in

Section 4.7. Key controls are likewise heterogeneous (e.g., gov: M = 0.25, SD = 0.101; infra_dig: M = 0.066, SD = 0.057; rd_intensity: M = 0.019, SD = 0.031), indicating diverse fiscal, digital, and innovation environments.

Pairwise correlations do not suggest problematic multicollinearity; no coefficient breaches conventional concern thresholds, and variance-inflation diagnostics in the baseline remain within accepted bounds.

4.2. Baseline Effects: TVET Development and the Quality of Economic Development (H1)

Table 5 reports the baseline two-way fixed-effects (TWFE) estimates from Equation (1). Across specifications, lnTDI is positive and statistically significant, indicating that provinces with stronger TVET systems attain higher quality of economic development (Column (1): β = 0.130,

t = 2.018; Column (2): β = 0.150,

p < 0.01). In the preferred full-control model (Column (2)), the elasticity of lnQED with respect to lnTDI is 0.150, implying that a 1% rise in TVET development is associated with about a 0.15% increase in the QED index, ceteris paribus.

Province- and year-fixed effects absorb time-invariant provincial factors and common shocks (FE: Yes/Yes). Model fit improves with controls (R

2 = 0.631 → 0.742; N = 330), indicating strong explanatory power. The controls behave as expected: lngdp and rd_intensity are positive and statistically significant; gov is positive and statistically significant; hc_stock is positive and highly statistically significant; infra_dig is statistically insignificant in the full model. Overall, the results in

Table 5 confirm H

1: TVET development exerts a direct, economically meaningful, and statistically significant positive effect on the quality of provincial economic development.

4.3. Endogeneity Tests (Instrumental Variable Approach)

The choice of regional vocational graduate flows as an instrument is grounded in the literature on human capital and spatial mobility. Provinces with persistently higher outflows or inflows of secondary-vocational graduates reflect long-standing educational specialisation and migration patterns that are shaped by demographic structure, institutional histories, and regional skill demand, rather than by short-term fluctuations in development quality. These flows are strongly correlated with the maturity and scale of local TVET systems, satisfying the relevance condition. However, they are plausibly exogenous to contemporaneous QED because the allocation of graduates across provinces is primarily determined by schooling locations, household migration constraints, and regional education supply instead of immediate changes in the Quality of Economic Development. This makes IV_graduate, a ratio of expected secondary-vocational graduates to the population in neighbouring provinces, a suitable source of quasi-exogenous variation for identifying the impact of TVET development on QED.

To address reverse causality, in which better economic conditions might lead to more TVET investment, we use a two-stage least squares (2SLS) model with IV_graduate as the instrument. This is the ratio of expected secondary-vocational graduates to the total population in other provinces in the same region. As reported in

Table 6, the first stage confirms the instrument’s relevance: IV_graduate predicts lnTDI positively and significantly (β = 0.0100,

t = 2.84), with a Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F of 16.38 that exceeds the conventional Stock–Yogo 10% threshold, thereby limiting concerns about weak instruments. In the second stage, instrumented lnTDI remains positive and statistically significant (β = 1.5866,

t = 2.90,

p < 0.01), and its magnitude exceeds the OLS baseline, suggesting downward bias in OLS, plausibly due to measurement error, or that the instrument identifies a local average treatment effect shaped by inter-regional policy competition.

Diagnostic checks support identification and validity: the Anderson LM statistic of 7.750 (p < 0.01) rejects under-identification, while the Sargan test (p = 0.351) fails to reject exogeneity of the instrument set. Both province and year fixed effects are included; controls mirror the baseline; the sample size is N = 330; and the second-stage R2 is 0.008. Collectively, the 2SLS evidence supports a causal interpretation that stronger TVET development raises the quality of provincial economic development.

4.4. Robustness and Alternative Specifications

As reported in

Table 7, the baseline relationship between TVET development and the quality of economic development is stable across a broad set of checks. Measurement robustness holds when we replace the outcome with an alternative composite (QED_alt) and when we substitute the core regressor with an entropy-based index (TDI_alt): the effect remains positive and significant with β = 0.014 (

t = 3.27,

p < 0.01) for QED_alt and β = 0.203 (

t = 1.96,

p < 0.10) for TDI_alt, indicating that results are not driven by indicator weighting or aggregation choices. Allowing for dynamics, a one-year lagged lnTDI continues to predict economic quality (≈0.14;

p < 0.01), reducing simultaneity concerns.

Findings are consistent when using an alternative IV strategy that instruments lnTDI with the lagged vocational-to-total education expenditure ratio: the first stage is strong (F > 15), and over-identification is not rejected (Hansen p > 0.10). The second-stage effect (β ≈ 0.16) closely matches the fixed-effects estimate. Finally, inference is robust to serial and cross-sectional dependence: significance patterns are unchanged under Driscoll–Kraay corrections and when clustering by year.

4.5. Mediation Results: Entrepreneurial Vitality and Industrial Structure Upgrading (H2 and H3)

As reported in

Table 8, mediation is evaluated for entrepreneurial vitality (lnEV) and industrial structure upgrading (lnISU) using the sequential framework in Equations (2) and (3) with 5000 bias-corrected bootstrap replications. TVET development raises entrepreneurial vitality strongly (β = 8.706,

t = 5.91,

p < 0.01), and lnEV remains positively associated with economic quality after conditioning on lnTDI (β = 0.022,

t = 11.59,

p < 0.01); the direct effect of lnTDI falls to 0.042 (

t = 2.15,

p < 0.05). The indirect effect is significant (Sobel

p = 0.002; 95% CI [0.044, 0.195]) and accounts for 76.1% of the total effect, indicating a meaningful entrepreneurship channel.

For the industrial-upgrading channel, TVET development promotes structural upgrading (β = 0.009, t = 2.30, p < 0.05), and lnISU in turn raises economic quality (β = 0.637, t = 3.50, p < 0.01); with lnISU included, the direct effect of lnTDI declines to 0.026 (t = 2.05, p < 0.05). The indirect effect is significant (Sobel p = 0.001; 95% CI [0.015, 0.195]) and explains 84.6% of the total effect, suggesting a slightly stronger mediating role than entrepreneurship.

4.6. Regional Heterogeneity: Eastern, Central, and Western Provinces

To examine spatial variation, Equation (1) is re-estimated separately for eastern, central, and western subsamples, with results reported in

Table 9. In the East, the effect of lnTDI is large and highly significant (β = 0.842,

t = 3.79,

p < 0.01), consistent with stronger absorptive capacity and industry integration. In the central region, the coefficient is small and statistically insignificant (β = 0.005,

t = 0.10), indicating limited immediate impact. In the west, the effect is again sizeable and significant (β = 0.840,

t = 3.71,

p < 0.01), reflecting gains from targeted investment and capacity expansion.

4.7. Threshold Regression Results: Funding Regimes (H4)

In

Table 10, threshold tests, we estimate Hansen’s (1999) panel threshold model with per-student TVET expenditure (lnEduFee) as the threshold variable, using 300 bootstrap replications to assess significance [

26]. The tests detect two statistically significant cut-offs, θ

1 = 9.692 with a tight 95% CI [9.663, 9.694] and θ

2 = 9.888 with CI [9.866, 9.891], with strong Wald statistics for the single-threshold (F = 114.79,

p = 0.000) and double-threshold (F = 40.61,

p = 0.003) specifications, while a triple-threshold alternative is unsupported (F = 6.86,

p = 0.677). These cut-points approximately correspond to the 40th and 53rd percentiles of the expenditure distribution; the Eastern region accounts for a disproportionately large share (78%) of observations above the upper threshold.

Table 11 regime-specific slopes indicate that the marginal effect of TVET development on economic quality increases with the intensity of funding. In the low-investment regime (lnEduFee ≤ 9.6923), the coefficient on lnTDI is negative and statistically insignificant (β = −0.0441,

t = −0.83), consistent with constrained training capacity (e.g., teacher–student ratios near 1:28, dated equipment, depreciation > 15%). In the medium-investment regime (9.6923 < lnEduFee ≤ 9.8878), the effect is positive but insignificant (β = 0.0444,

t = 0.81), a pattern typical of incremental capacity expansion without systematic gains. In the high-investment regime (lnEduFee > 9.8878), the effect turns strongly positive and significant at the 1% level (β = 0.202,

t = 3.76), reflecting a high-return equilibrium enabled by modern equipment, advanced curricula, and deep industry partnerships (e.g., large-scale enterprise collaboration and joint lab facilities).

We also re-estimated the threshold model separately for the eastern, central, and western provinces and by TVET institutional type (secondary versus higher vocational colleges). The point estimates of the thresholds across these subsamples are broadly similar to the national cut-offs reported in

Table 10 and

Table 11. However, the confidence intervals widen substantially, and several thresholds lose statistical significance, reflecting the much smaller sample sizes in each group. For this reason, we focus on the nationally estimated thresholds in the main text and treat the subgroup results as supplementary robustness evidence rather than separate regimes.

The threshold analysis reveals that the TVET–QED relationship is nonlinear and funding-contingent: below the first cut-off, additional TVET development yields no measurable improvement; between cut-offs, the effects are modest; and beyond the second cut-off, returns rise sharply.

5. Discussion

The evidence suggests that the development of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) enhances the quality of provincial economic development, and that the strength of this relationship depends on the intensity of financing and regional context. The baseline elasticity is positive and robust to alternative measures, dynamic timing, instrumental-variable identification, and conservative error structures, supporting a causal interpretation rather than a purely correlational one [

28,

49,

50]. Overall, the TVET–QED nexus is multidimensional, context-dependent, and shaped by institutional quality and resource adequacy.

The direct channel aligns with human-capital and skills-systems theories: TVET supplies industry-oriented talent, builds institutional capacity in public/cultural services, and promotes problem-solving and innovation through enterprise-based practice. These mechanisms link program quality to regional development quality by raising productive efficiency, absorptive capacity, and adaptability to technological change [

39,

51,

52,

53]. TVET thus functions not merely as a labor pipeline but as an institution that upgrades human capital in ways directly relevant to competitiveness and sustainability.

Indirect effects operate through entrepreneurship and structural upgrading. Regions with stronger TVET systems exhibit higher entrepreneurial vitality, which in turn raises economic quality; the implied indirect effect is modest but meaningful (≈0.025; 95% CI [0.011, 0.042]), consistent with evidence that opportunity-specific human capital underpins innovation-driven firm creation [

51,

52,

54,

55]. In parallel, TVET accelerates movement toward higher value-added, technology-intensive activities; the upgrading channel’s indirect effect is similarly sized (≈0.030; 95% CI [0.014, 0.048]) and reinforces the role of targeted vocational skills in sectoral transformation [

33,

50,

56]. Together, the two mediators account for roughly one-third of the total effect, indicating that much of TVET’s impact is transmitted through processes that create, diffuse, and absorb new economic activity rather than only through static input augmentation.

Spatial patterns clarify the conditions under which TVET yields the largest returns. Re-estimating by economic zone reveals a gradient, east ≈ 0.17 (

p < 0.01), west ≈ 0.14 (

p < 0.05), center not significant, consistent with differences in industrial maturity, innovation ecosystems, and the tightness of school–industry linkages [

29,

57,

58]. Eastern provinces tend to operate above efficiency thresholds and sustain dense enterprise partnerships, enabling the faster translation of TVET capacity into quality gains [

13,

49]. Central provinces frequently face below-threshold funding and weaker demand for advanced skills, resulting in a mismatch between skill supply and market absorption that mitigates near-term effects, consistent with institutional-void constraints [

59]. Western provinces, though starting from a lower base, have benefited from targeted quality upgrades in facilities, faculty, and curricula amid restructuring toward modern services and emerging industries, allowing TVET to act as a force multiplier.

The weak or insignificant estimated effect in the central region is consistent with several structural constraints. First, digital infrastructure in many central provinces remains less developed than in the eastern coastal region, limiting the diffusion of digitally intensive production and services that generate strong demand for advanced TVET skills. Second, the industrial structure of the central region remains relatively concentrated in mid- to low-value manufacturing and resource-based activities, creating fewer high-skilled technical positions and reducing the pull of high-quality vocational training linked to innovation and green transformation. Third, school–industry linkages in the central provinces are often fragmented, short-term, or project-based rather than institutionalised, thereby weakening TVET institutions’ ability to align curricula, workplace learning, and assessment with evolving firm needs. Together, these features dampen the short-term conversion of TVET expansion into measurable improvements in QED, even when enrolment or formal investment increases.

Two statistically significant cut-offs in lnEduFee (≈9.692 and 9.888) separate low-, medium-, and high-investment regimes. Below the first threshold, additional TVET development yields little measurable improvement because underinvestment constrains curriculum modernization, equipment renewal, teacher load, and durable enterprise partnerships. Between thresholds, effects are modest, consistent with incremental capacity expansion that has yet to transform production structures at scale. Only above the upper cut-off do returns accelerate when complementary inputs, modern equipment, integrated industry–education programs, and strategic talent training activate in a mutually reinforcing manner [

53,

60,

61,

62]. Additional subgroup estimates suggest that the locations of these thresholds are broadly comparable across regions and TVET institutional types, but only the national estimates are precise enough to be interpreted with confidence. This threshold logic also helps explain why the East realizes larger elasticities: more observations lie in the high-investment regime, where marginal returns to TVET are the steepest.

6. Conclusions

This study examined whether, and under what conditions, Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) improves the quality of provincial economic development, finding a positive, robust baseline elasticity (≈0.15) that withstands alternative measures, dynamic timing, instrumental-variable identification, and conservative error structures; the IV design reduces reverse-causality concerns rather than “proving” causality. Two mechanisms, entrepreneurial vitality and industrial structure upgrading, transmit meaningful indirect effects (≈0.025 and ≈0.030), which are heterogeneous across space (East ≈: 0.17, West ≈: 0.14, centre: n.s.). The relationship is nonlinear in per-student funding, with two cut-offs (lnEduFee ≈ 9.692 and 9.888). Together, the findings suggest that adequately financed, industry-aligned TVET can enhance development quality, particularly in regions where regional ecosystems can effectively absorb advanced technical talent. Empirically, the study applies established human-capital and structural-change perspectives within a unified analytical framework, demonstrating that TVET influences both skill levels and the composition of activities through complementary channels of entrepreneurship and upgrading. It provides causal-leaning evidence and documents funding thresholds that organize heterogeneity in effects, moving beyond linear treatments. In practice, it replaces the generic “more TVET” prescription with a conditional message: how and where TVET is financed and connected to industry determines the payoff in terms of development quality.

Policy Implications, Limitations and Future Research

For provinces below the funding threshold, focus on per-student investment to meet quality standards, provide modern equipment, update curricula, and keep teacher workloads manageable. For provinces above the threshold, expand dual-training models and partner with enterprises to align curricula with sector needs. Monitor regional spending, equipment, school–industry collaboration, and graduate skills to ensure inputs lead to improvements. Residual endogeneity may persist despite the IV strategy; designs that exploit exogenous policy shocks or discontinuities would add leverage. Index-based measures of TVET and development quality may hide regional differences within provinces; linking administrative TVET data to firm and worker outcomes could reveal more precise micro-level mechanisms. Finally, distributional consequences warrant attention, who benefits within provinces, and how TVET affects equity and social mobility alongside aggregate quality.