Abstract

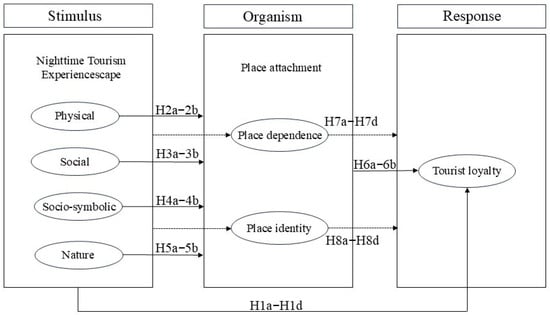

Nighttime tourism has become a key driver of urban nighttime economic development. The nighttime tourism experiencescape (NTE)—comprising elements such as atmospheric lighting landscapes, culturally distinctive night markets, and diverse entertainment formats—creates an environment markedly distinct from daytime settings. This NTE significantly influences tourist experiences and contributes critically to the sustainable development of urban destinations. Grounded in the Stimulus–Organism–Response framework, this study investigates how the NTE shapes tourist loyalty. Empirical results indicate that the effect of the NTE on tourist loyalty is primarily mediated by place attachment, with place dependence demonstrating a stronger mediating effect than place identity. In the direct pathway, only the socio-symbolic dimension of the NTE exerts a significant positive impact on tourist loyalty. The study offers both theoretical and practical contributions: it reveals the mechanisms that influence tourist loyalty in nocturnal contexts and offers actionable insights into the sustainable management of nighttime tourism in urban destinations.

1. Introduction

As urbanization progresses, tourism has extended into nighttime hours [1]. This evolution has given rise to nighttime tourism (NTT), a distinct form of tourism that transcends conventional spatial limitations by emphasizing the temporal dimension, thereby enriching the spatiotemporal dynamics of urban tourism [2]. As an integral component of the nighttime economy, NTT is recognized as a key driver of urban economic growth and cultural vitality [3,4]. Its offerings not only provide visitors with distinctive visual and cultural experiences that enhance destination image but also inject renewed dynamism into the nighttime economy itself [5].

The appeal of NTT lies in its distinctive atmospherics and cultural resonance, which extend beyond a mere temporal extension of daytime tourism [1]. The nocturnal cityscape—crafted through illuminated landscapes, night markets, and entertainment venues- offers culturally immersive experiences [6] that foster deeper emotional connections between tourists and destinations. This unique experiential spectrum allows for cultural engagement within relaxed and socially inclusive nocturnal settings [2]. Unlike daytime tourism, which often centers on hurried sightseeing, the night transforms urban spaces through lighting and ambiance into experiential realms characterized by mystery, relaxation, romance, and dynamism [7]. These intentionally designed environments provide unique sensory stimulation and facilitate social interaction, thereby enabling deeper cultural immersion [8].

The distinct landscapes and environments of NTT are poised to significantly influence tourists’ psychological states [8]. Tourist loyalty is a key psychological and behavioral construct for the sustainable development of tourism destination. Highly loyal tourists not only help reduce marketing costs for destinations but also attract more potential visitors through positive word-of-mouth communication [9], thereby providing sustained momentum for the long-term growth of destinations. Although extensive research has examined the antecedents of loyalty [10], the existing literature remains predominantly focused on daytime contexts, largely overlooking the unique attributes of urban NTT environments and their psychological impact. The destination environment serves as the spatial foundation of tourist activities, and its impact on tourist loyalty cannot be overlooked. How the nighttime tourism environment shapes tourist loyalty thus remains an underexplored research gap. Specifically, does the urban nighttime tourism experiencescape (NTE), which is fundamentally distinct from its daytime counterpart, enhance tourist loyalty, and if so, through what mechanisms? Addressing these questions would not only expand the theoretical understanding of tourist loyalty from a temporal–spatial contextual dimension but also offer evidence-based insights to guide the planning and sustainable management of NTT.

In response to these research limitations, this study employs the theoretical perspectives of servicescapes and the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) model to investigate the relationship between NTE and tourist loyalty, with an empirical focus on the Qinhuai River–Confucius Temple scenic area in Nanjing, a renowned nighttime tourism destination in China.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 1 presents the introduction. Section 2 delineates the literature review. Section 3 elucidates the derivation of hypotheses. Section 4 details the materials and methods employed in the study. Section 5 examines the empirical results obtained. Section 6 interprets the findings in the discussion. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the study and presents concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Servicescape and Nighttime Tourism Experiencescape

Servicescapes, a fundamental concept in service marketing, refer to environmental factors shaping customer perceptions and experiences. Bitner [11] formally proposed the ‘servicescapes’ framework, conceptualizing it as the physical environment that affects the behaviors of both customers and employees in service settings. Subsequently, Baker et al. [12] expanded the elements of servicescapes, emphasizing the importance of interpersonal interactions and social components within these environments. This led Tombs and McColl-Kennedy [13] to innovatively incorporate customer elements into servicescape modeling, establishing the ‘social servicescape model’. Later, Rosenbaum and Massiah [14] enriched the traditional physical-social servicescape framework by integrating symbolic social elements and natural environmental factors, achieving a more comprehensive conceptualization of servicescape dimensions.

As a quintessential activity within the experiential economy, tourism increasingly depends on distinctive scenario design and ambiance crafting to shape memorable encounters. Building upon servicescape theory, O’Dell [15] pioneered the concept of ‘experiencescapes’, which Mossberg [16] later systematized into four core components: physical environments, products/souvenirs, social contexts, and co-tourist interactions. This conceptual framework has subsequently catalyzed interdisciplinary applications across diverse tourism contexts. For instance, Hu & Chen [17] developed the destination experiencescape for coastal tourism, while Radic et al. [18] investigated the cruise ship dining experiencescape. Similarly, Zong & Tsaur [19] adapted the framework to Hanfu tourism, identifying eight distinct components of the destination experiencescape for Hanfu tourism. These contributions have significantly enriched the theoretical framework of experiencescape.

Building upon the conceptual foundations of experiencescapes, this study proposes the NTE as a multidimensional construct that represents the holistic integration of both tangible and intangible environmental elements perceived by tourists in nocturnal tourism destinations. The framework systematically encompasses four constitutive dimensions: the physical dimension, the natural dimension, the social dimension, and the socio-symbolic dimension. The physical dimension primarily involves spatial layout and the physical environment. The natural dimension pertains to natural elements that possess attention-restorative properties, such as green vegetation, rivers, and lakes. The social dimension emphasizes human interactions, focusing on the interpersonal communications between tourists and various groups at the destination. Finally, the socio-symbolic dimension includes markers, symbols, or representations that convey the cultural connotations of the destination, comprising both tangible elements like tourist souvenirs and intangible elements such as historical narratives.

Compared to daytime tourism, the NTE places greater emphasis on tourists’ situational perception and multi-dimensional experiences within the unique nocturnal environment. Visually, the lightscapes created by nighttime illumination not only soften the visual imperfections of the destination but also enhance a sense of detachment from reality through their stage-like effects, thereby deepening immersive engagement. Auditorily, reduced background noise amplifies intentionally designed soundscape elements such as thematic music and live performances, further reinforcing immersion. Spatially, visitors’ attention becomes more focused on key nodal areas highlighted by lighting, such as squares, stages, and light shows, while their movement range tends to be more concentrated. Such a light-guided spatial configuration significantly shapes tourists’ spatial perception and behavioral experience. Moreover, activities such as night markets and tourism performances enhance the social dimension of the NTE.

2.2. Tourist Loyalty

Tourist loyalty represents a foundational construct in tourism consumer behavior, originally defined by Oliver [20] as sustained destination preference and repeat visitation intention. Building on this foundation, Baker and Crompton [21] operationalized this concept through revisit intention and recommendation willingness, establishing measurable dimensions. Subsequent methodological refinements by Chen [22] and Lee et al. [23] differentiated attitudinal loyalty, manifested through destination attachment, from behavioral loyalty. This attitudinal–behavioral dichotomy, particularly operationalized through revisit intention and word-of-mouth (WOM) advocacy, has gained substantial empirical validation in contemporary tourism studies.

Extensive literature demonstrates that satisfaction serves as a fundamental determinant of tourist loyalty [24]. Research confirms that satisfied tourists exhibit stronger revisit intentions and greater propensity for destination recommendations. Service quality enhances loyalty by meeting tourist expectations, delivering value, and consequently strengthening revisit intentions, reducing price sensitivity, and increasing the likelihood of WOM referrals [25,26]. Additional empirically validated antecedents include destination image [9], destination personality [27], visitors’ experience [28], involvement [29], and tourist engagement [30]. These factors operate through interconnected psychological and behavioral mechanisms to shape loyalty formation.

Extensive scholarly investigations have significantly advanced our understanding of tourist loyalty through comprehensive literature reviews and synthesis. Nonetheless, this review also uncovers several critical limitations within the current scholarship.

Tourist loyalty—a complex outcome variable—is influenced by a multitude of subjective (e.g., satisfaction, perceived value) and objective (e.g., destination image) factors. While prior studies have examined these relationships, the role of objective experiencescapes, particularly in NTT, remains underexplored. Given the stark contrast between nocturnal and diurnal tourism environments, an empirical question persists: Does the nighttime tourism experiencescape significantly enhance tourist loyalty? Furthermore, although servicescape theory has been applied in tourism research, its extension to nighttime tourism contexts is scarce.

To address these gaps, this study develops a conceptual model that links NTE to tourist loyalty. It employs quantitative methods for empirical validation and aims to provide theoretically grounded, systematic support for the sustainable development of NTT in destinations.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Theoretical Model

The SOR model was initially proposed by Mehrabian and Russell [31] as a framework to elucidate the mechanisms through which external environmental factors influence individuals. This model serves as a pivotal explanatory tool in environmental psychology. The SOR model posits that: Stimulus (S) refers to external environmental cues that act as stimuli. Organism (O) indicates that these stimuli trigger internal psychological states within individuals. Response (R) denotes that psychological states subsequently drive behavioral responses. This model effectively elucidates how individuals react to external stimuli, rendering it widely applicable across diverse research domains. In the context of NTT, the SOR model offers significant theoretical guidance for examining the impact of the NTE on tourist loyalty. NTE (e.g., lighting, ambiance, activities) serve as external stimuli. Tourists’ psychological perceptions—operationalized in this study as place attachment—mediate the stimulus-response relationship. The behavioral outcome is tourist loyalty.

3.2. Research Hypothesis

3.2.1. Nighttime Tourism Experiencescapes and Tourist Loyalty

Based on the SOR theory, external environmental stimuli exert profound effects on individuals’ psychological perceptions and behavioral responses. In the context of tourism, a service-oriented industry, the environmental factors of the NTE constitute a critical form of external stimulus. These stimuli not only trigger tourists’ physiological reactions but also evoke emotional experiences and shape cognitive evaluations, ultimately influencing loyalty behaviors such as revisit intentions. Existing research demonstrates that servicescapes significantly impact consumers’ loyalty behaviors [32]. From a physical dimension perspective, the built environment of the NTE, encompassing ambient factors, spatial layout of facilities, and symbolic artifacts, exerts significant influence on tourist experiences. Knoferle et al. [33] empirically verified that both functional accessibility and aesthetic appeal in spatial configurations stimulate consumption frequency and improve retention rates. Synthesizing these theoretical and empirical foundations, we propose:

H1a:

The physical dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on tourist loyalty.

When examining the impact of the NTE on tourist loyalty, the social dimension plays a critical role. According to Yang et al. [34], tourists’ psychological states and behaviors are significantly influenced by interactions with service staff, which not only shape immediate experiences but may also foster long-term loyalty. Additionally, customer-to-customer interactions within service environments enhance tourists’ sense of belonging and perceived social support—key factors in cultivating loyalty [13]. Line et al. [35] conceptualized tourism destinations as holistic servicescapes, demonstrating that social servicescapes positively influence tourists’ emotional responses and revisit intentions. These findings underscore the importance of social dynamics in tourism experiences and highlight the pivotal role of social interactions in building loyalty. Based on the existing literature, we propose:

H1b:

The social dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on tourist loyalty.

Socio-symbolic elements (e.g., handicrafts, cultural symbols) serve dual functions: they enhance environmental cultural richness while facilitating consumer psychological identification and belongingness [14]. As cultural identity carriers, these elements strengthen tourist-environment emotional attachments. Empirical evidence confirms that culturally significant symbolic cues foster customer–servicescape emotional connections, generating senses of belonging and acceptance that positively affect WOM and repurchase behaviors [36]. This emotional linkage mechanism constitutes a vital pathway for tourist loyalty development. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H1c:

The socio-symbolic dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on tourist loyalty.

Research indicates that natural elements in commercial environments can enhance consumers’ psychological well-being and health perceptions [37]. Rosenbaum [38] introduced the concept of the ‘natural dimension’ in servicescapes, demonstrating that consumers perceive the restorative potential of natural elements, such as greenery, water features, and open-air spaces. Extending this line of inquiry, Vanessa et al. (2020) [39] illustrate the significant impact of natural plants on tourist satisfaction and loyalty, while Kou et al. (2025) [40] further establish the notable influence of a destination’s natural environment on tourist experience and perception. Collectively, such perceptions foster a functional dependency on the setting, encouraging repeat visitation. The natural dimension enhances both consumers experience quality and emotional attachment to servicescapes, thereby positively influencing behavioral intentions. Based on this theoretical foundation, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1d:

The natural dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on tourist loyalty.

3.2.2. Nighttime Tourism Experiencescape and Place Attachment

This study adopts a two-dimensional structure of place attachment: place dependence and place identity [41]. Place dependence reflects an individual’s reliance on and attachment to the functional facilities of a destination, while place identity represents the emotional identification that individuals develop with the destination at a spiritual level.

The SOR theory posits that external stimulus influence individuals’ cognitive and affective states, ultimately affecting behavioral outcomes [31]. In servicescapes context, environmental factors such as spatial layout, décor, ambiance, and color schemes significantly shape consumers’ cognitive evaluations [42]. Within the NTT setting, architectural styles, distinctive lighting, and other physical elements constitute primary stimuli that evoke emotional responses and foster destination attachment [43]. Importantly, visitors’ positive cognitive evaluations of experiencescapes significantly elevate satisfaction levels, thereby strengthening place identity. Based on this theoretical foundation, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a:

The physical dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place dependence.

H2b:

The physical dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place identity.

Belongingness theory posits that customer interactions within servicescapes cultivate feelings of respect, acceptance, and inclusion, fostering emotional investment and potential attachment formation [40]. Empirical studies confirm that positive social interactions provide essential psychological support, constituting a fundamental precursor to servicescape attachment. In tourism destination, balanced interpersonal dynamics enhance peer recognition during nocturnal activities. This social validation facilitates the transformation into destination identification and functional dependence. Theoretically, this suggests that the social dimension of servicescapes positively influences place attachment in tourism contexts. Consequently, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a:

The social dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place dependence.

H3b:

The social dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place identity.

Place attachment represents a symbolic bond between individuals and specific locations, emerging from shared cultural and emotional connections. Empirical research indicates that high levels of empathetic arousal significantly influence customers’ holistic perceptions of servicescapes, which in turn affect their emotional responses and evaluations of the services provided [14]. Grounded in this theoretical framework, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4a:

The socio-symbolic dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place dependence.

H4b:

The socio-symbolic dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place identity.

Based on Kaplan’s [44] Attention Restoration Theory, the tranquility and harmony provided by environments play a crucial role in alleviating mental fatigue and facilitating emotional recovery. Within NTT contexts, nocturnal activities including landscape viewing and evening strolls provide distinctive restorative experiences. These experiences transcend mere geographical spaces, transforming them into meaningful places embedded with personal memories and social connections [45], thereby reinforcing place attachment.

Empirical research identifies positive sensory stimulation and cultural engagement as pivotal factors in creating profound experiential impressions [46]. The nocturnal temporal dimension offers unique sensory experiences that differ markedly from daytime encounters. Enhanced nighttime activities and distinctive environmental atmospheres strengthen place attachment through intensified sense of place. As Li et al. [5] demonstrate, NTE serve dual functions in destination development, enhancing visitors’ perceived value and fostering place identity formation, thereby contributing to sustainable destination attractiveness. With increasing diversification and personalization of nighttime offerings, this attachment relationship is anticipated to further consolidate. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5a:

The natural dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place dependence.

H5b:

The natural dimension of the NTE has a positive impact on place identity.

3.2.3. Place Attachment and Tourist Loyalty

Place attachment is widely recognized as a critical antecedent of tourist loyalty [47]. When tourists form emotional bonds with a destination, they tend to evaluate it more favorably, which leads to increased intentions to revisit and a greater likelihood of making WOM recommendations. Jia and Lin [48] incorporated place attachment as a mediating variable in their conceptual model, demonstrating how destination quality influences tourist satisfaction, which in turn affects tourist loyalty. Patwardhan et al. [49] further validated the positive impact of place attachment on tourist loyalty within the specific context of religious festivals, thereby reinforcing the role of place attachment in fostering loyalty. Based on these findings, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H6a:

Place dependence has a positive impact on tourist loyalty.

H6b:

Place identity has a positive impact on tourist loyalty.

3.2.4. Mediating Role of Place Attachment

Extensive research demonstrates that place attachment constitutes a cognitive and affective bond between individuals and their environment, formed through the integration of place-related cues that foster positive emotional connections [50]. Within tourism servicescapes, place attachment has been empirically validated to exert a significant positive influence on tourist loyalty [51], underscoring the pivotal role of emotional ties between visitors and destinations in driving loyal behaviors. Given the multidimensional nature of place attachment, encompassing both place dependence and place identity, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7a:

Place dependence plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the physical dimension and tourist loyalty.

H7b:

Place dependence plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the social dimension and tourist loyalty.

H7c:

Place dependence plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the socio-symbolic dimension and tourist loyalty.

H7d:

Place dependence plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the natural dimension and tourist loyalty.

H8a:

Place identity plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the physical dimension and tourist loyalty.

H8b:

Place identity plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the social dimension and tourist loyalty.

H8c:

Place identity plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the socio-symbolic dimension and tourist loyalty.

H8d:

Place identity plays an intermediary role in the relationship between the natural dimension and tourist loyalty.

As described above, a schematic summary of the study’s hypotheses is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research hypotheses and theoretical model.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Site

The survey was conducted in the Confucius Temple-Qinhuai River Scenic Area in Nanjing City, China. This scenic area, located in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, is an open-type tourist attraction covering a total area of 2.76 square kilometers. A five-kilometer section of the Qinhuai River winds through the area, connecting numerous historical and cultural landmarks, including the Confucius Temple, ancient city gates, former residences of notable figures, and traditional streets such as Wuyi Alley, and the Chinese Imperial Examination Museum, etc. Historically, this area has served as the most prosperous commercial and cultural center of Nanjing. Since the initiation of its preservation and development in 1984, the area has revived and has continued to host the annual Qinhuai Lantern Festival since 1986, which became its earliest nighttime tourism initiative. In 2010, the scenic area was awarded China’s highest honorary rating for tourist attractions—the National AAAAA-level Tourist Attraction. In addition to the long-standing Lantern Festival, the “Night Mooring on the Qinhuai” cruise serves as the core experience of the area’s NTT. This experience is complemented by a diverse range of offerings, including night markets, museum visits, intangible cultural heritage performances, light shows, and theater productions, which together form a comprehensive NTT activity system. This vibrant mix attracts a substantial number of visitors. According to statistics, the scenic area received 28.91 million visits in the first half of 2025 alone, ranking it among the most-visited high-level tourist attractions in China.

The Nanjing Confucius Temple-Qinhuai River Scenic Area was selected as the research site based on its distinctive strengths in visitor diversity and situational completeness, offering a robust empirical foundation for this study. The selection is supported by the following considerations. First, NTT in this area originated in 1986, reflecting its longstanding development and established maturity. It currently offers a diverse array of NTT activities that are widely favored by visitors. Second, the area has achieved notable socioeconomic benefits through its NTT initiatives, as further demonstrated by its inclusion in the inaugural 2021 list of ‘National-level Nighttime Culture and Tourism Consumption Clusters’ issued by the Chinese Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Third, although NTT in China takes multiple forms—such as theme park night tours and nightscapes showcasing modern urban achievements—the predominant model continues to be the revitalization of historic urban districts—integrating cultural heritage with contemporary commerce and blending natural and humanistic elements. Given its alignment with this mainstream model, the Nanjing Confucius Temple-Qinhuai River Scenic Area represents a typical and highly representative site for data collection.

4.2. Variables Measurement

To ensure measurement validity and applicability, this study adapted established experiencescape scales from Dong et al. [52] and Pizam & Tasci [53] as its foundation. Based on the specific characteristics of the case study site, the Nanjing Confucius Temple-Qinhuai River Scenic Area, necessary adjustments were made, resulting in a NTES comprising 23 items. For place attachment, we primarily referenced the validated scales of Patwardhan et al. [49], which exhibit high reliability in prior research. Considering this study’s context, 6 items were designed to assess place dependence and place identity. Tourist loyalty was measured using Verma & Rajendran’s [54] well-validated scale, demonstrating high reliability and validity in existing studies. After refinement, 3 items were retained for evaluation. The specific measurement items for each variable are detailed in Appendix A. The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree,” 5 = “strongly agree”), alongside standard demographic questions.

4.3. Data Collection and Sample Structure

Prior to the formal distribution of questionnaires, the research team invited experts and scholars in tourism management, students, and tourists who had previously participated in NTT activities to evaluate the preliminary draft of the questionnaire. Based on their feedback, adjustments were made to the wording of relevant items to enhance clarity and improve respondents’ comprehension and overall experience.

The survey was conducted during nighttime hours from 2–16 June 2023. A convenience sampling method was employed, primarily following the approach recommended by Assiouras et al. (2019) [55]. Researchers approached visitors at scenic area parking lots and main exits as they concluded their visits. Initial verbal screening confirmed that participants had completed their NTT experience and were willing to participate in the study. After providing a detailed explanation of the research purpose and obtaining informed consent, eligible visitors were invited to complete a self-administered structured questionnaire. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in 363 valid responses, which yields an effective response rate of 90.75%. The demographic characteristics of the surveyed sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample profile.

4.4. Data Analysis Methods

In the analysis of the sample data, this study primarily employed AMOS 26.0 software to conduct hypothesis testing on the direct effects between variables through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Prior to performing the CFA, the researchers conducted preliminary assessments, including a common method bias test, normality distribution evaluation, and reliability-validity verification. To examine mediating effects, the bootstrap method with 5000 resamples was systematically applied to ensure statistical robustness.

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Bias Test

Common method bias (CMB) refers to potential deviations in measurement results caused by reliance on a single data source for sample collection [56]. To minimize such bias, well-established scales were adopted and appropriately modified to align with the characteristics of the research site. Questionnaires were distributed anonymously, and surveys were conducted across diverse locations and time periods. Furthermore, Harman’s single-factor test showed seven factors with eigenvalues >1 (unrotated), with the first factor explaining 39.31% of variance (<40% threshold), indicating no significant CMB impact on the findings.

5.2. Normal Distribution Test

This study conducted normality tests on the sample data using SPSS 26.0 software to ensure compliance with the prerequisites for subsequent statistical analyses. Specifically, the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of each latent variable were calculated, with the results presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

The analysis revealed that the absolute values of skewness coefficients for all 32 measurement items ranged from 0.018 to 0.736, all below the threshold of 3. Similarly, the absolute values of kurtosis coefficients ranged from 0.028 to 1.569, all below the critical value of 10. These findings confirm that the sample data satisfy the normality assumption, thereby making them suitable for further statistical analysis.

5.3. Reliability and Validity Test

The reliability analysis demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α coefficients for all latent variables ranging from 0.728 to 0.869, exceeding the conventional threshold of 0.7.

Convergent validity was assessed using factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 3, all factor loadings exceed the 0.5 threshold. CR values range from 0.733 to 0.873, exceeding the recommended minimum of 0.6 [57]. The AVE values range from 0.409 to 0.619. While the ideal AVE value should exceed 0.5, some scholars contend that an AVE value between 0.36 and 0.5 is still acceptable [58]. These results confirm the measurement model’s convergent validity.

Table 3.

The overall measurement model.

Discriminant validity testing serves as a critical foundation in structural equation modeling (SEM). While prior research has widely adopted the Fornell-Larcker criterion (AVE-SV comparison) as the primary method for evaluating discriminant validity, recent studies suggest that this approach may be ineffective under certain conditions [59]. To address this limitation, Henseler et al. [60] proposed the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) as an innovative method for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based SEM. The core idea of the HTMT is to compare the ratio of the average correlations between different constructs to the geometric mean of the average correlations within the items of the same constructs. A lower HTMT value indicates sufficient discriminant validity among the constructs. Comparative analyses of the Fornell-Larcker criterion and cross-loadings have demonstrated that the HTMT ratio exhibits superior performance in discriminant validity assessment.

This study assessed discriminant validity using Henseler’s [60] Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio method, following contemporary methodological standards. The analysis adopted the widely accepted HTMT threshold of <0.85, which demonstrates optimal balance between identification accuracy and false-positive rates [61]. As presented in Table 4, all HTMT ratios below the 0.85 benchmark, thereby confirming the measurement model’s discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity test of all constructs (HTMT test).

5.4. Model Fitting Indicators

This study conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 26.0 to evaluate the model fit, as presented in Table 5. The analysis indicates that the fit indices, including χ2/df, RMSEA, IFI, and CFI, all fall within acceptable thresholds, thereby demonstrating a good model fit.

Table 5.

Model Fit Index.

5.5. Path Analysis

The direct effects between variables were analyzed through path analysis, with the key results summarized in Table 6. Based on the SEM path analysis results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Table 6.

Estimated standardized coefficients.

The socio-symbolic dimension demonstrated a statistically significant effect on tourist loyalty, with a path coefficient of β = 0.219 (p < 0.05), thereby supporting H1c. In contrast, neither the physical dimension nor the natural dimension exhibited statistically significant effects on tourist loyalty. Therefore, H1a and H1d were not supported. Interestingly, while the social dimension showed a statistically significant influence on tourist loyalty (β = −0.178), its negative effect contradicted the hypothesized direction leading to the rejection of H1b.

The analysis revealed statistically significant effects of the physical dimension, socio-symbolic dimension, and natural dimension on both place dependence and place identity. Specifically, for place dependence, the path coefficients were β = 0.328 (p < 0.001), β = 0.228 (p < 0.05), and β = 0.161 (p < 0.05), thereby supporting H2a, H4a and H5a. In terms of place identity, the corresponding path coefficients were β = 0.261 (p < 0.01), β = 0.261 (p < 0.01), and β = 0.276 (p < 0.001), confirming H2b, H4b, and H5b. Additionally, the social dimension exhibited a significant effect on place dependence with β = 0.227 (p < 0.05), thereby supporting H3a. However, its impact on place identity did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.133), resulting in the rejection of H3b.

Furthermore, the analysis indicated statistically significant effects of both place dependence and place identity on tourist loyalty with path coefficients of β = 0.405 (p < 0.001) for place dependence and β = 0.322 (p < 0.001) for place identity. These results suggest that both dimensions of place attachment positively influence tourist loyalty, providing empirical support for H6a and H6b.

5.6. Mediating Effect Test

To thoroughly examine the mediating role of place attachment between night tourism experiencescape and tourist loyalty, this study employed the Bootstrap method to test the significance of mediation effects. Utilizing 5000 resamples at a 95% confidence interval (CI), the results confirmed the mediating effects of place attachment. As illustrated in Table 7, none of the 95% confidence intervals for the mediation effects included zero, thereby providing robust support for H7a, H8a, H7b, H8b, H7c, H8c, H7d, and H8d.

Table 7.

Test of Mediating Effect.

6. Discussions

First, the analysis reveals that only the social-symbolic dimension of the NTE exerts a direct and significant positive influence on tourist loyalty, whereas the physical, social and natural dimensions exhibit non-significant direct effect. This finding diverges from established insights drawn from indoor consumption settings [62], highlighting the distinct complexity of NTT environments.

Specifically, the nonsignificant effects of the physical and natural dimensions can be explained by limited nighttime illumination, which restricts tourists’ holistic visual perception and detailed recognition of physical environments and natural landscapes. This finding is relatively consistent with Ruan’s qualitative study conclusion that the natural dimension does not have a significant impact on tourist experience [8]. Additionally, natural elements such as vegetation and water bodies are less able to serve their attention restoration function during nighttime, thereby reducing their role in fostering tourist loyalty. The social dimension also did not significantly affect loyalty, which may be attributed to tourists’ heightened safety awareness in nocturnal settings. Concerns for personal and property safety lead them to voluntarily reduce non-essential social interactions with strangers.

In contrast, this effect can be attributed to the fact that during NTT, cultural markers, symbols, and symbolic elements—such as distinctive architectural landscapes, locally symbolic souvenirs, and historically themed performances—constitute the core of the nocturnal experience. By reinforcing cultural identity and enhancing the sense of place uniqueness, these elements directly foster tourist loyalty.

Second, the research indicates that all hypotheses regarding the influence of the NTE on place attachment were supported, with the exception of the social dimension (H3b). Physical elements of the NTE, including ambient atmosphere, spatial layout, and design, along with the distinctive socio-symbolic cues of the Nanjing Confucius Temple, actively engage tourists’ emotions [63]. This engagement allows tourists to temporarily detach from daily routines and immerse themselves in the relaxing environment of NTT, thereby facilitating stress recovery and emotional relaxation [64,65]. Moreover, it enhances tourists’ place dependence and place identity towards the destination. While the social dimension of the NTE significantly affects place dependence, its impact on place identity is not significant. This may be explained by demographic profile of the respondents, who are predominantly young and middle-aged (75.7%). Tourists in these age groups tend to seek diverse destination experiences and prioritize whether the features and functions of NTT align with their personal needs [66]. Consequently, they are less likely to develop a strong place identity towards a specific destination.

Third, both place dependence and place identity exhibit statistically significant positive effects on tourist loyalty. This finding suggests that a stronger attachment to NTE correlates with a greater willingness to engage in WOM recommendations and revisit. These results align with existing literature on the relationship between place attachment and tourist loyalty [49]. Notably, the path coefficient for place dependence exceeds that of place identity, indicating that tourists prioritize functional fulfillment (e.g., convenience, amenities) in NTT settings, while emotional identification requires prolonged exposure. This finding challenges the assertion made by Zou et al.’s (2022) [47] that place identity exerts a stronger influence on loyalty behaviors across all dimensions of place attachment, as this claim does not hold true in nocturnal tourism contexts.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

7.1. Conclusions

The same site exhibits differentiated landscape characteristics and environmental atmospheres across distinct temporal dimensions [7]. The diurnal-nocturnal alternation not only offers visitors diversified visual scenes but also further influences their perceptual and psychological states. As an integral component of the urban nighttime economy, NTT offers visitors culturally distinctive experiences shaped by unique displays, diverse entertainment, and atmospheric lighting. Although NTE is considered vital to the vitality and sustainability of nighttime tourism [4], its impact on tourist loyalty remains unclear. Focusing on visitors to the Confucius Temple-Qinhuai River Scenic Area, this study examines the underlying mechanisms through which the NTE influences tourist loyalty.

The main findings are summarized as follows: First, the influence of the NTE on tourist loyalty is primarily mediated by place attachment. This suggests that tourists’ perceptions of nighttime landscapes, activities, and services must evolve into an emotional and psychological bond with the place to foster stable revisit and recommendation intentions. Within the NTT context, multisensory stimulation enhances tourists’ multifaceted value perception of the destination, which, in turn, cultivates a sense of dependence on and identification with it, ultimately promoting loyalty behaviors. It is noteworthy that the mediating effect of place dependence is slightly stronger than that of place identity, indicating that tourists’ behavioral loyalty relies more on the functional value of the setting—such as photo-friendly scenic spots and varied nighttime food offerings—than on emotional identification.

Second, within the direct effect pathway, only the socio-symbolic dimension of the NTE exerts a significant direct positive effect on tourist loyalty. Elements conveying cultural expression, social interaction, and identity symbolism—such as thematic light displays and narrative landscapes—can directly motivate tourist loyalty behaviors. This implies that symbolic consumption and meaning construction in NTT may serve as an independent behavioral driver, particularly for tourists seeking cultural experiences and identity affirmation.

7.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes two key theoretical contributions. First, it extends servicescape theory into NTT by demonstrating how the NTE functions under nocturnal conditions, clarifying the distinct operation of environmental stimuli after dark and offering a new theoretical pathway for understanding tourist behavior at night. While tourism occurs throughout all hours of the day, research specifically focused on nighttime tourism remains limited. [7] This study extends servicescape theory into the domain of nighttime tourism, thereby advancing the theoretical understanding of the mechanisms through which nighttime settings exert their influence. Second, the study advances the understanding of tourist loyalty by revealing its formation mechanism in nighttime settings. While existing loyalty frameworks are predominantly derived from daytime contexts, this research addresses a significant theoretical gap and highlights the critical role of temporal and situational factors in loyalty development.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study acknowledges several limitations. First, the research is geographically limited as it draws on data from a single site. Although the Confucius Temple-Qinhuai River Scenic Area is highly typical and representative of nighttime tourism, it is important to note that the findings may not be readily generalizable to other types of tourism destinations, such as theme parks. Future studies should incorporate comparative analyses across diverse destination typologies to enhance external validity. Second, the cultural applicability of the findings necessitates verification. While Chinese cultural contexts exhibit a strong affinity for nocturnal tourism activities, cross-cultural comparisons with societies that demonstrate different nighttime leisure patterns would provide valuable insights. Moreover, safety is a critical issue that cannot be overlooked in the context of NTT. The findings of this study indicate that the direct effect of the social dimension on tourist loyalty was not supported. One plausible explanation for this is that the distinctive nocturnal environment may heighten tourists’ sensitivity to safety and psychological vigilance, thereby diminishing the direct role of the social dimension in fostering loyalty. Consequently, in NTT settings, systematically investigating how perceived safety shapes tourist experience and loyalty presents a valuable direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and K.C.; methodology, L.G.; software, Y.C.; validation, J.C.; formal analysis, K.C.; investigation, J.C. and Y.C.; resources, J.C.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C. and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, K.C., L.G.; visualization, Y.C.; supervision, K.C.; project administration, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Scholarship Council, grant number 202406910064, and the APC was funded by the China Scholarship Council.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of School of Business and Tourism, Sichuan Agricultural University (protocol code BTSAUIRB-2023–0201 and date of approval 10 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/uvezs/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Variables | Items |

| Physical | PH1. The lighting here at night is very distinctive. |

| PH2. The overall color here at night is harmonious. | |

| PH3. The background music playing at night here is very harmonious. | |

| PH4. The smell of the snacks here at night is very attractive. | |

| PH5. The sanitary environment at night here is clean and tidy. | |

| PH6. The street decoration design at night is distinctive. | |

| PH7. The cruise programs and supporting facilities at night are well laid out. | |

| PH8.The tourist signage system here conveys a clear message at night. | |

| PH9. The facilities open at night are functional and well-maintained. | |

| PH10. The architectural landscape is distinctive at night. | |

| Social | SO1. The density of tourists at night is moderate. |

| SO2. I can interact with each other as equals. | |

| SO3. I can relate to each other casually. | |

| SO4. I can interact with each other without worrying about anything. | |

| SO5. The service staff here is hospitable, polite and friendly. | |

| Socio-symbolic | SY1. The night scene here shows the historical flavor. |

| SY2. The souvenirs here are distinctive | |

| SY3. The cruise programs and performances at night are distinctive. | |

| SY4. I am attracted to the overall cultural atmosphere at night. | |

| SY5. I am familiar with the cultural symbols displayed here. | |

| Natural | NA1. I can escape from the world by traveling here at night. |

| NA2. The night scene here is fascinating. | |

| NA3. The night cruise scene here is compatible with my personality. | |

| Place dependence | PD1. I prefer the nighttime atmosphere here to other destinations. |

| PD2. This place satisfies my nightlife needs better than other destinations. | |

| PD3. It gives me a sense of satisfaction that I can’t get anywhere else. | |

| Place identity | PI1. Here nighttime experience is unique. |

| PI2. I have a strong sense of identity here. | |

| PI3. I like it so much that I don’t want to leave too soon. | |

| Tourist loyalty | TL1. I would recommend this place to my family and friends. |

| TL2. I would like to bring more companions to this place. | |

| TL3. I would like to visit this place again in the future. |

References

- Eldridge, A.; Smith, A. Tourism and the night: Towards a broader understanding of nocturnal city destinations. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2019, 11, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, S.; Xu, S.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Research on the sustainable development of urban night tourism economy: A case study of Shenzhen City. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 870697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Does tourism contribute to the nighttime economy? Evidence from China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.X.; Li, Y.Q.; Ruan, W.Q.; Zhang, S.N. Night tourscape in streets: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 61, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.H.; Ruan, W.Q. How to create a memorable night tourism experience: Atmosphere, arousal and pleasure. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 1817–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. The gloomy city: Rethinking the relationship between light and dark. Urban Stud. 2013, 52, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J.; Wang, P. All that’s best of dark and bright: Day and night perceptions of Hong Kong cityscape. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.Q.; Jiang, G.X.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.N. Night tourscape: Structural dimensions and experiential effects. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X. The five influencing factors of tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Grewall, D.; Parasuraman, A. The influence of store environment on quality inferences and store image. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombs, A.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. Social-servicescape conceptual model. Mark. Theor. 2003, 3, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Massiah, C. An expanded servicescape perspective. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, T. Experiencescapes: Blurring Borders and Testing Connections. In Experiencescapes: Tourism, Culture & Economy; O’Dell, T., Billing, P., Eds.; Frederiksberg Copenhagen Business School Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mossberg, L. A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Chen, H. Destination experiencescape for coastal tourism: A social network analysis exploration. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 46, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, A.; Lück, M.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chua, B.L.; Seeler, S.; Han, H. Cruise ship dining experiencescape: The perspective of female cruise travelers in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Y.; Tsaur, S. Destination Experiencescape for Hanfu Tourism: An Exploratory Study. J. China Tour. Res. 2023, 20, 144–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Gursoy, D. An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeon, S.; Kim, D. The impact of tour quality and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: The case of Chinese tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yan, B. From soundscape participation to tourist loyalty in nature-based tourism: The moderating role of soundscape emotion and the mediating role of soundscape satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 26, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akroush, M.N.; Jraisat, L.E.; Kurdieh, D.J.; Al-Faouri, R.N.; Qatu, L.T. Tourism service quality and destination loyalty-the mediating role of destination image from international tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco López, M.F.; Virto, N.R.; Manzano, J.A.; García-Madariaga, J. Archaeological tourism: Looking for visitor loyalty drivers. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 15, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.H.; Loi, K.I.; Xu, J. Investigating destination loyalty through tourist attraction personality and loyalty. J. China Tour. Res. 2020, 18, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Lin, C.; Llonch-Molina, N.; Marine-Roig, E. The impact of olive oil tourism on multisensory experiences and tourist loyalty. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 40, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.; Engeset, M.G.; Nyhus, E.K. Tourist involvement in vacation planning and booking: Impact on word of mouth and loyalty. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Noor, S.M.; Schuberth, F.; Jaafar, M. Investigating the effects of tourist engagement on satisfaction and loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Tuncer, I.; Unusan, C.; Cobanoglu, C. Service quality, perceived value and customer satisfaction on behavioral intention in restaurants: An integrated structural model. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 22, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoferle, K.M.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Herrmann, A.; Landwehr, J.R. It is all in the mix: The interactive effect of music tempo and mode on in-store sales. Mark. Lett. 2012, 23, 325–337. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41488784 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, A. The Influence of emotional labor of service employees on customer service misbehavior and repurchase intention: The role of face. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Kim, W.G. An expanded servicescape framework as the driver of place attachment and word of mouth. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 42, 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, M.; Nelson, T. From servicescape to consumption scape: A photo-elicitation study of Starbucks in the New China. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 1010–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H. Healthy places: Exploring the evidence. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S. Restorative servicescape: Restoring directed attention in third places. J. Serv. Manag. 2009, 20, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanessa, A.; Patrick, H.; Cristobal, F.R.; Diego, Y. Natural plants in hospitality servicescapes: The role of perceived aesthetic value. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, L.; Wei, C.; Chi, C.G.; Xu, H. Understanding sensescapes and restorative effects of nature-based destinations: A mixed-methods approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, M.; Yeager, E.P.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mimbs, B.P. Measuring place attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). J. Environ Psychol. 2021, 74, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F.; Hanne, P.L.; Jonathan, B. The cosmopolitan servicescape. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H.G. The effects of tourscape and destination familiarity on tourists’ place attachment. Tour. Tri. 2023, 38, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Place: An experiential perspective. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jasper, C.R. A cross-cultural examination of the effects of social perception styles on store image formation. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wei, W.; Ding, S.; Xue, J. The relationship between place attachment and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.G.; Lin, D.R. Tourists’ perception of urban service, place attachment and loyal behaviors: A case study of Xiamen. Geogr. Res. 2016, 35, 390–400. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Payini, V.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mallya, J.; Gopalakrishnan, P. Visitors’ place attachment and destination loyalty: Examining the roles of emotional solidarity and perceived safety. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Ren, Z.; Guo, Z.; Gao, S.; Xu, Y. Individual differences in place attachment and pro-environmental behavior: Pride as an emotional tie. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 214, 112357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.N.M.; Mohamad, M.; Ghani, N.I.A.; Afthanorhan, A. Testing mediation roles of place attachment and tourist satisfaction on destination attractiveness and destination loyalty relationship using phantom approach. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Siu, N.Y. Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Tasci, A.D.A. Experienscape: Expanding the concept of servicescape with a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Rajendran, G. The effect of historical nostalgia on tourists’ destination loyalty intention: An empirical study of the world cultural heritage site—Mahabalipuram, India. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Skourtis, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Buhalis, D.; Koniordos, M. Value co-creation and customer citizenship behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, Y.W. A scale for measuring teachers’ mathematics-related beliefs: A validity and reliability study. Int. J. Instr. 2017, 10, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. A holistic model of the servicescape in fast casual dining. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, G.; Oettler, L.; Katz, L.C. Imagining the loss of social and physical place characteristics reduces place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H.G. A structural model of liminal experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Moraga, E.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C.; Alonso-Dos-Santos, M.; Vidal, A. Tourscape role in tourist destination sustainability: A path towards revisit. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnow, R. Place type or place function: What matters for place attachment? Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2024, 73, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).