1. Introduction

Over the last decade, policy uncertainty and disruptive dynamics have increased in the global economy, prompting companies to strive for competitiveness by delivering high-quality products or services and adapting to new sustainability requirements. For improved transparency and resilience, enhanced through sustainability reporting, companies can demonstrate their environmental and social responsibility, while also strengthening their relationships with various stakeholders [

1]. The company’s ability to integrate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into its strategy becomes increasingly important [

2].

The regulatory framework has evolved from the UN 2030 Agenda, which developed seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to a continuous process of sustainability reporting disclosure that encompasses ESG aspects. The integration of the SDG-ESG nexus represents a strategic approach, supported by the complex regulations developed over the last years. At the global level, regulators have enforced rules for disclosing complex non-financial information that supports sustainability goals. For example, with its ambitious targets, the European Union’s (EU) directives have evolved from a voluntary disclosure, as supported by the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) [

3], to a mandatory disclosure based on double materiality, as outlined in the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) [

4], which facilitates companies’ transition to sustainable practices.

While the EU has developed the most comprehensive and integrated regulatory framework in the world, EU guidelines are applied to all companies outside the EU that operate on the European market, and many non-EU countries adopt or adapt these regulations. The EU framework ensures increased transparency compared to other standards, and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) normalized methodology ensures comparability [

5,

6]. Moreover, the European market predictably reacts to the regulatory announcements. The EU introduced revolutionary concepts, such as double materiality, taxonomy, and value chain, which are explored in this study. We chose this framework as a reference, not because it is the best, but because it is the most mature and comprehensive regulation, has a global impact on the market, offers data for longitudinal analysis, and represents a natural laboratory for studying the adoption of sustainability reporting. The alternative would have been to consider multiple reporting frameworks, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), etc. This choice would have reduced data consistency and made it difficult to isolate a single framework.

The EU’s ambitious approach that empowers big companies to provide complex metrics supported by ESRS, as well as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), to provide information voluntarily, in accordance with European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) proposals, has led stakeholders to face strategic uncertainty in navigating its rapid evolution [

7]. In this context, the Omnibus regulation package [

8] and the “Stop the clock” directive [

9] simplify and postpone for two years the numerous administrative tasks for companies affected by the new regulations.

Following the development of these regulations, academic literature evolved, incorporating new concepts and paradigms. Mainly, the authors focused on descriptive and retrospective mappings of the field, with descriptive bibliometric analysis dominating the field’s cartography [

10,

11]. Still the stakeholders (companies, investors, regulators, researchers) are confronted with a strategic uncertainty in the ESG-SDG integration due to a complex and dynamic chain of factors: the rapid evolution of the regulations (CSRD, ESRS), of the assurance standards of sustainability reporting, from International Standard on Assurance Engagement (ISAE) 3000 [

12] to International Standard on Sustainability Assurance (ISSA) 5000 [

13], and a vast and retrospective academic literature. They must understand not only that there is a domain but also where it is headed to prioritize their investments, research, and regulatory efforts efficiently. It involves a strategic decision-making problem in complex and uncertain conditions.

A major challenge in integrating CSRD-related research topics with SDGs is the comprehensive complexity and dynamism of the system [

14]. A critical gap exists in academic literature, as there are a lack of approaches that combine the bibliometric cartography with forecast models to anticipate the research tendencies and to link them directly to the strategic alignment with specific SGDs, offering an actionable guide for strategic planning. Essentially, there is a leap from description to prediction, which the literature has yet to make systematically in this specific domain. The existence of practical problems (strategic uncertainty) creates a need for knowledge. The existing academic literature, primarily based on descriptive bibliometrics, does not adequately address this need, leaving a research gap due to a lack of prediction-oriented research aimed at action and predictive analytics that forecast research trends to inform strategic decision-making in sustainable business integration.

The primary objective of this paper is to illustrate the evolution of sustainability reporting. Additionally, the study aims to demonstrate how the new sustainability framework aligns with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which encompass the three pillars: environmental, social, and governance matters. Lastly, predictive bibliometrics adds value by providing a data-driven approach for setting priority strategies.

Following the problem statement and the research gap, in accordance with the paper’s objective, the study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the structural and thematic evolution of academic literature at the intersection of sustainability reporting, assurance, and the SDGs over the past decade (January 2015–September 2025)?

RQ2: Which CSRD-related research terms show the most substantial alignment with specific SDGs, and how is their growth trajectory projected?

RQ3: Based on the forecasted trends, what are the strategic priority areas for future research and business investment to strengthen the ESG-SDG nexus?

Our research employs a tripartite analytical methodology designed to map systematically, evaluate, and forecast the ESG-SDG nexus: first, a bibliometric analysis to cartograph the existing academic research landscape and identify key themes and evolutions; second, an alignment (mapping) analysis to critically assess the coherence and gaps between ESG reporting practices and specific SDG targets; and third, a predictive model approach that combines multiple scientific approaches with sustainability metrics, utilizing AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), Error, Trend, Seasonal (ETS) Components, and regression models with SDGs to extrapolate future research trajectories and emerging trends, transforming empirical insights into a strategic, forward-looking framework.

The paper contributes to the literature in three ways:

1. It provides a novel predictive perspective by combining bibliometric mapping with an ensemble forecasting model; It moves beyond the dominant descriptive paradigm in bibliometric studies of ESG/SDG research [

10,

11] by integrating ensemble forecasting models. This allows us to project future research trends, offering strategic foresight rather than retrospective analysis.

2. It introduces a quantifiable SDG alignment score for CSRD-related topics. We develop a novel SDG Impact Score, a composite indicator that assesses both the volume and interdisciplinary breadth of CSRD-related research associated with each of the Sustainable Development Goals. This provides a granular, empirical map of how current academic discourse connects corporate social responsibility and disclosure (CSRD) to global goals (SDGs), addressing the often-theoretical discussion on this nexus.

3. It offers actionable strategic priorities for investment and research derived from the empirical forecast. We synthesize the bibliometric mapping, SDG alignment scores, and growth forecasts to identify Tier 1 and Tier 2 priority domains (e.g., ‘ISSA 5000′ for auditors, ‘double materiality’ for strategists).

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 develops the key framework and concepts,

Section 3 details the bibliometric and forecasting methodologies,

Section 4 presents and discusses the results, and

Section 5 presents the conclusions, implications, and limitations.

3. Research Methodology

Bibliometric analysis has become a cornerstone of understanding the complex sustainability-related fields. Several studies have mapped the academic landscape of this area [

10,

11]. These studies synthesized past knowledge and identified research clusters through a retrospective and descriptive methodology, concluding with recommendations for future studies that provide quantitative, predictive trajectories of the field. This creates a methodological gap; while we know where the research has been, we lack robust, model-driven tools for anticipating future directions. Our study addresses this gap by mixing cartographic mapping techniques from bibliometrics with advanced forecasting models to generate actionable, forward-looking information for the ESG-SDG nexus.

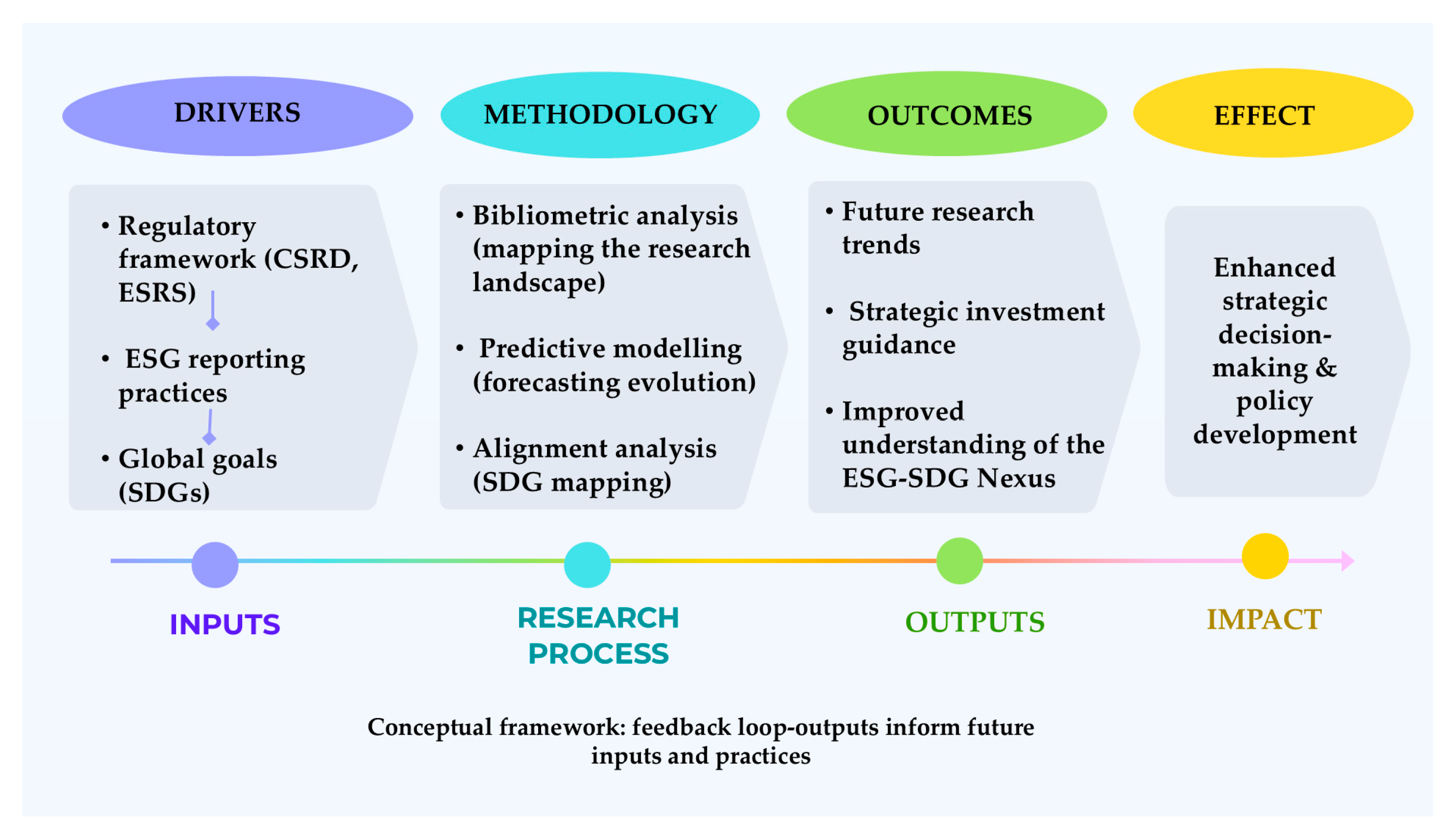

This section runs through the methodology employed to address the research questions and provides a systematic framework for data collection, analysis, results discussion, and interpretation. Through this research, we aim to deliver a comprehensive cartography of the main academic writing movements related to the ESG-SDG nexus, based on CSRD and ESRS requirements, as well as forecasts that consider the challenges and opportunities in sustainable business integration (

Figure 1).

To answer the RQ and overcome the limitations of previous descriptive studies, we adopted an integrated conceptual framework (

Figure 1), which transforms the driving factors (inputs) of the ESG-SDG nexus into strategic impact through a cyclic research process. This combines: 1. The bibliometric cartography of the field, 2. Critical analysis of the alignment reporting practices (CSRD/ESRS) and SDGs, and 3. The predictive modelling of the evolution of tendencies. The outputs of this process—the forecasts, research tendencies, and the strategic guide inform future practices and policies, closing a feedback loop that assures a continuous relevance of the framework. This conceptual framework is the background on which the paper’s logic is built. Bibliometric analysis ensures objectivity within the examined sample [

40].

This research database is the Web of Science (WoS) by Clarivate, providing a broader range of high-quality academic writings and ensuring credibility in the field of study. Web of Science allows files to be downloaded in different formats. Thus, the database used for this research study was downloaded in “Tab delimited file” to be used in VOSviewer 1.6.20 and in “BibText” format to be used in Biblioshiny software 5.2.0, as well as in RStudio 4.5.2. The selected period is from January 2025 to September 2025. The data was extracted from WoS on 8 November 2025.

To identify the academic papers that would establish the research sample, we searched for articles in the field of non-financial reporting and assurance, based on the ISAE 3000 or ISSA 5000 frameworks. To ensure an adequate search using the CSRD, ESRS, ISAE 3000, and ISSA 5000 reporting frameworks, the following Boolean string was used in combination with the corresponding logical connectors: (“Sustainability reporting” OR “ESG reporting” OR “CSRD” OR “Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive” OR “ESRS” OR “European Sustainability Reporting Standards”) AND (“ISSA 5000” OR “ISAE 3000” OR “assurance”).

For the selection of sample papers, the key phrase “sustainability reporting” was primarily considered, which could have generated results at a global level. By associating it with the terms CSRD and ESRS, the final sample included papers that were published predominantly by authors from the European Union and studies conducted on European companies. However, no restriction was set regarding the countries of origin of the authors. To ensure the robustness of the research conclusions, the bibliometric analysis will be structured into two categories based on the authors’ countries of origin: developed and developing. To perform the statistical tests, the data were grouped into developed countries as high-income and developing countries as upper-middle-income and lower-middle-income, based on the World Bank’s country classification.

In the current bibliometric analysis, two programs were used: VOSviewer and R Studio—Biblioshiny. Van Eck and Waltman [

41] suggest that VOSviewer can be utilized to create maps based on keywords, co-citations, and authors, enabling researchers to analyze the information in greater detail. It is also a powerful tool when the sample has more than 100 items. In the bibliometric analysis, the keyword maps and those referring to the most influential articles were created using VOSviewer version 1.6.20. To refine the database and acquire accurate outcomes for the bibliometric analysis, a “thesaurus” file has been imported. The thesaurus file has been checked so that each term is unique.

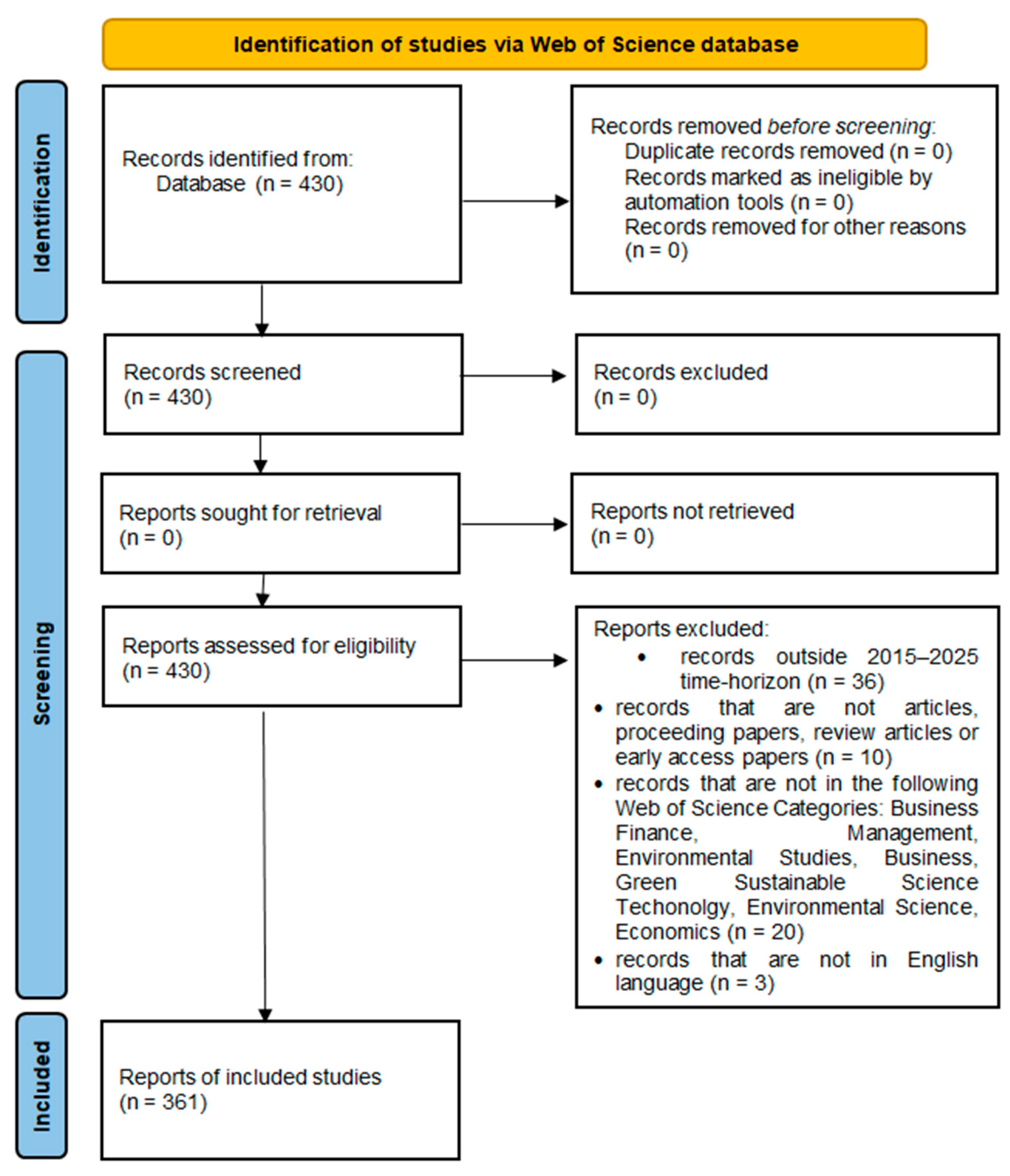

The process of identifying studies in the Web of Science (Clarivate) database is described in

Figure 2 using a PRISMA flow diagram. The initial search consists of 430 papers. After applying several filters and refining the inquiries, the research is focused on 361 articles.

The dataset for the period January 2015–September 2025 incorporates academic discourse based on CSRD terminology and its established linkages to the UN SDGs. Using the tidyverse, forecast, lubridate, ggplot2, viridis, scales, and gridExtra libraries in R Studio 4.5.2, we performed a complex analysis based on mapping and forecasting.

Twelve core CSRD-related research terms (CSRD, double materiality, supply chain, value chain, EU Taxonomy, ESRS, ISAE 3000, ISSA 5000, sustainability assurance, sustainability reporting, investors, stakeholders) were selected based on their importance in sustainability reporting frameworks. Their selection is grounded in the conceptual architecture of the EU’s sustainability reporting framework, not chosen arbitrarily, but based on the key components that the CSRD addresses: 1. The regulatory core (the “what”) CSRD, ESRS, and EU taxonomy as binding rules and standards, 2. The conceptual principles (the “how”)—double materiality, supply chain, value chain as novel methodologies defining scope and assessment; 3. The reporting practice (the “action”)—ESG reporting, sustainability reporting, 4. The assurance mechanism (the “verification”)—sustainability assurance, ISAE 3000, ISSA 5000, that helps to ensure credibility and combat greenwashing; 5. The strategic purpose (“for whom, why”)—investors, stakeholders, as driving the reliable data demand. This approach ensures a comprehensive value chain of policy-practice CSRD triggers, related to practical challenges and academic research innovation, that directly inform the capabilities needs for SDG alignment.

Based on these terms, we created a mapping dictionary as the foundation for the qualitative analysis of the CSRD’s thematic requirements and the SDG targets, defining the mapping between each CSRD-related research term and its corresponding relevant SDGs. To quantify the interdisciplinary relevance and impact of each SDG within our research landscape, we constructed an SDG impact score. This approach aligns with previously developed research on creating robust, sustainable indices [

42], particularly in measuring research alignment with global agendas [

43].

To respond to the second research question (RQ2), we calculated an Impact Score based on two key variables extracted from the research data: 1. Total research mentions, representing the total number of articles mentioned for each SDG across all CSRD-related terms, and 2. The number of distinct CSRD research terms that map to each SDG as terms covered. The formula used is as follows:

Impact score = (Total mentions × Terms covered)/10 (The division by 10 is a normalization factor to scale the score to a manageable range for visualization).

The volume of research representing the total mentions reflects how frequently an SDG is discussed in the literature, indicating its prominence. The terms covered measure the number of different CSRD topics related to the SDG, indicating its interdisciplinary relevance. The multiplicative relationship ensures that SDGs with both high research volume and broad coverage receive higher impact scores, highlighting goals that are central to CSRD research.

To answer the third research question (RQ3), we developed an ensemble forecasting model. The idea was also explored by Chenary et al. [

44], who developed a forecast for global SDG scores using machine learning, and Martinez [

45], who focused on hybrid models for improved predictive accuracy.

We started with a temporal series (2015–2025) of annual academic research articles for each key term. To forecast the future, we did not perform only a single method, but we created an ensemble model that combines three different methods for maximum accuracy:

ARIMA, which captures trends and patterns from our historical data.

The ETS model, which models volatility and error structure.

Linear regression with SDG factors that explain the research activity through important external factors. In our model of linear regression, performed to answer RQ3, the dependent variable (LR = Linear Regression target) is the annual frequency of research publication for each of the twelve selected CSRD-related terms. Our model forecasts the number of scientific articles that will be published annually about each key concept within the sustainability reporting umbrella. This variable is defined as:

- -

LR (linear regression target) is the forecasted research volume.

- -

SDG_Weighted_Score: how well a key term covers multiple SDGs

- -

SDG_Alignment_Index: Grade of strategic alignment with SDGs targets

- -

Regulatory_wave: intensity of the regulatory pressure

- -

Market_volatility: economic uncertainty.

- -

Time_index: general temporal trend.

While individual models have weaknesses [

44], we combined them into an average (40% ARIMA, 35% ETS, and 25% regression) to create a more robust composite forecast.

The construction of the exogenous variables is based on the SDG Alignment index, which is calculated annually by mapping SDGs and corresponding annual growth rates. For the regulatory Pressure waves, a scaled index (0–1) reflecting key regulatory milestones (2014 NFRD = 0.2, 2022 CSRD adoption = 0.6, 2024 ESRS = 0.8). The market volatility proxy considered the annual average of the EU Economic Policy Uncertainty Index.

Finally, to answer RQ3, a Strategic Score is used to map each forecasted initiative into an investment-priority tier. Investment priority is determined using:

Strategic_Score ≥ 80 indicates “TIER 1 (critical); Tier 2—High (≥65 points), representing domains that exhibit growth potential and a pronounced alignment with sustainability.

The forecasting has inherent limitations, framing its results as exploration and strategic. The 10–11-year data limit reduces statistical robustness. The model cannot account for unforeseeable, paradigm-shift events, and the constructed indices are a simplification of complex reality. The model offers a systematic, data-driven approach for priority setting, rather than providing precise numerical predictions.

4. Results and Discussion

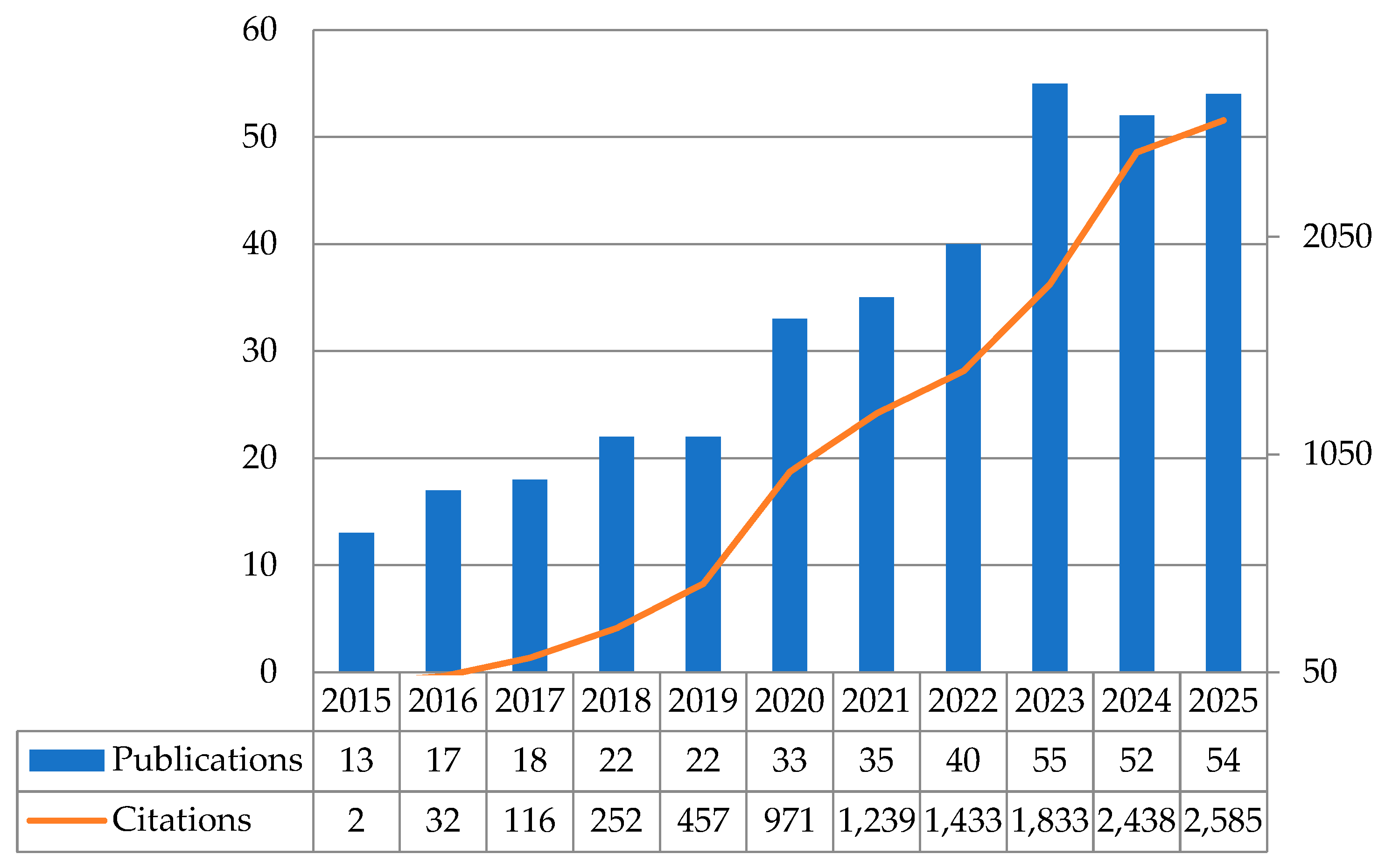

By using the selected terms, a series of relevant academic writings in the field of sustainability were identified (

Figure 3).

Based on the graphic in

Figure 3, the number of publications on this area increased significantly during the analyzed time horizon (2015–2025). The lowest stage was noted in 2015, with only 13 publications, which can be explained by companies’ focus on financial statements and results. In 2016, the GRI standards were restructured to facilitate the non-financial reporting process for companies, leading to an increase in publications in this area of research. The highest number of publications in the field of sustainability was recorded in 2023, with 55 papers, followed closely by the first three quarters of 2025. Given the current updates in sustainability reporting regulations, it is expected that research interest will increase, resulting in an upturn in the number of publications, surpassing the value seen in 2023.

This phenomenon is due to the implementation of the ESRS regulatory framework, which highlights new ESG reporting practices. In terms of citations, the trend is also on the rise, with the most significant increase occurring between 2023 and 2024, from 1.833 to 2.438 citations. The first part of the year 2025 is, of course, the most abundant in terms of citations: 2.585. We can see the increased interest of researchers in sustainability reporting and the amount of these documents. However, to strengthen these results,

Figure 2 suggests that the foundations of sustainability reporting and its importance for a company’s performance were established in research from 2015 to 2022, prior to the development of the ESRS.

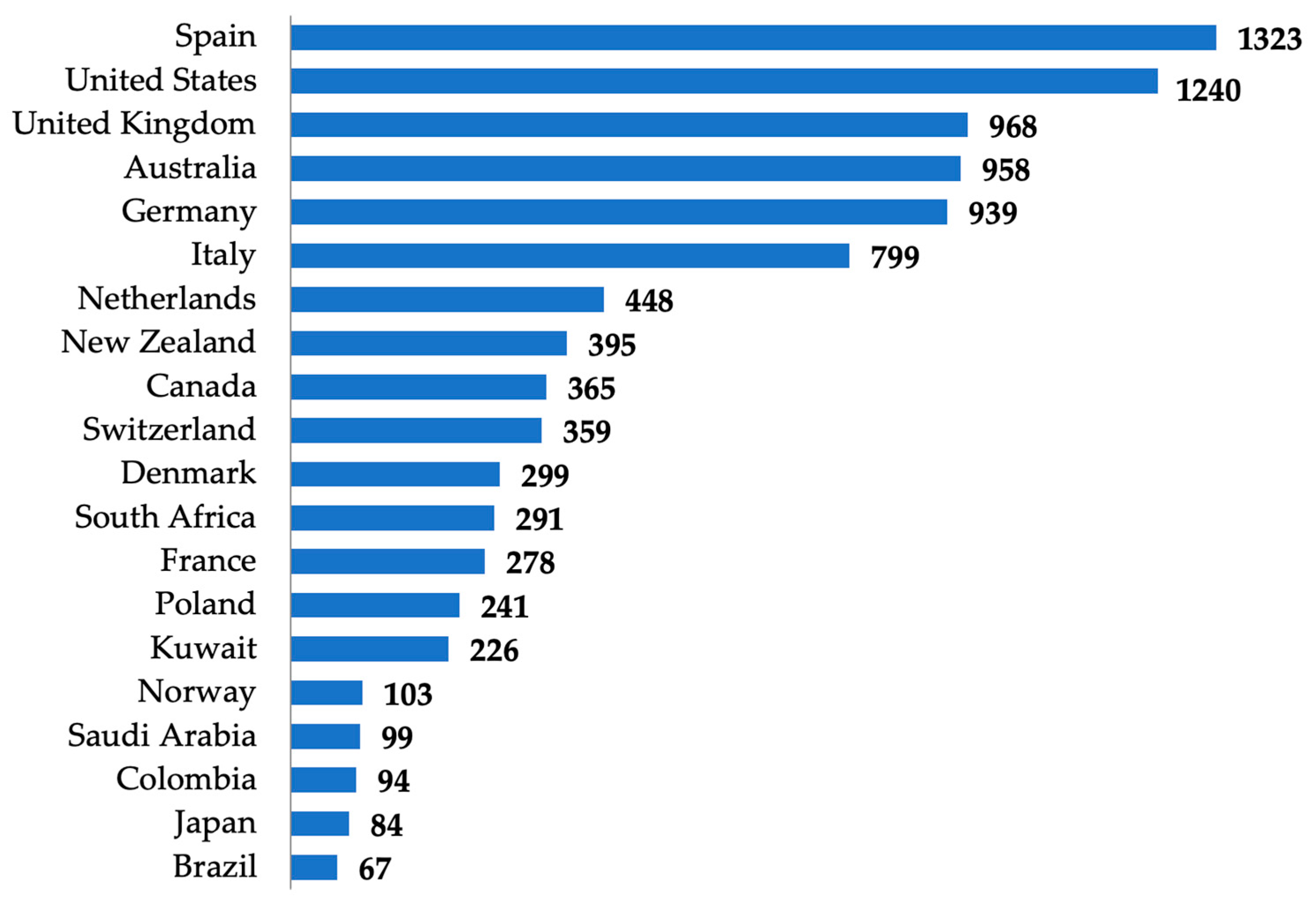

Moreover, the study is conducted on a global scale to investigate how different territories adapt to ESG trends. Of course, mitigating environmental, social, and governance risks is also a matter of corporate culture, which is diverse and specific to each territory.

Figure 4 illustrates the macroeconomic situation, specifically the number of citations, for the top 20 countries.

The most representative country, in terms of citations, is Spain, with 1323 citations and an average of 42.7 records per year during the analyzed period. The second position is occupied by the United States, with 1240 citations and an average of 31.8 citations. The following three countries in the ranking are the United Kingdom, with 968 citations, Australia, with 958 citations, and Germany, with 939 citations.

One common feature that can be observed among all 20 countries is that they have developed and prosperous economies, a high quality of life, and leading companies in international markets. The fact that the ranking includes articles written by authors from non-EU countries demonstrates a high degree of collaboration among authors from various regions.

Figure 5 represents a box plot that clearly highlights the structural differences in research impact between the two countries groups.

The visual description (

Figure 5) indicates that the distribution is targeted at higher citation values, with a superior median and dispersion in developed countries, and a low-value distribution with lower variability in developed countries. The two distributions are strongly differentiated, indicating a systematic disadvantage of the developing countries.

The econometric analysis highlights the effect of the development status (coefficient: 0.7117,

p = 0.001). The high statistical significance (

p-value < 0.01 confirms that the visual difference is not a hazard. The negative coefficient is translated into a deficit of ~51% in citations for developing countries (exp (−0.7117) ≈ 0.49).

Figure 5 illustrates this gap precisely, with the distribution for developing countries flat on the left side. The model explains 79.9% of the citation variations, having a high quality.

The model is based on the formula: Log(citationsi) = β0 + β1 Development + β2 Control + ϵi, where:

- -

Log(citations) = log of the citation number for each country (used for normalization);

- -

Development = independent dummy variable (1 for development and 0 for developed countries);

- -

Control = number of publications.

The robustness validation is proved by:

(a) The Breusch–Pagan test (p = 0.091), which assures homoscedasticity, the model error is constant in all the predictor values. The dispersion (“width”) of the distributions in our graphic is consistent and not systematically different between groups. The graph does not require transformations to be interpreted correctly.

(b) VIF test (maximum VIF = 2.69), absent multicollinearity: the predictors are independent, and the coefficient for development status is stable. This is related to the difference between the two curves, which can be directly attributed to the development status, without confounding from other correlated variables.

(c) Sample size (n = 62)—the figure captures a wide variety of countries, and the results are statistically robust.

The left-shifted distribution of developing countries is characterized by the significant negative coefficient (−0.7117), indicating a real deficit rather than random fluctuation. The clear separation of the two distributions, along with a low p-value (0.001), suggests that the difference is systematic and reproducible.

Robustness tests, including the Breusch–Pagan (for constant variance) and the VIF test (for low multicollinearity), confirm that the model’s assumptions are met, ensuring that the observed differences in distribution shape and dispersion are reliably estimated.

These tests have implications for research policies, particularly for developing countries, highlighting the priority investments in areas with high impact potential, international collaboration strategies to compensate for structural disadvantages, as well as mentoring programs and partnerships with institutions in developed countries.

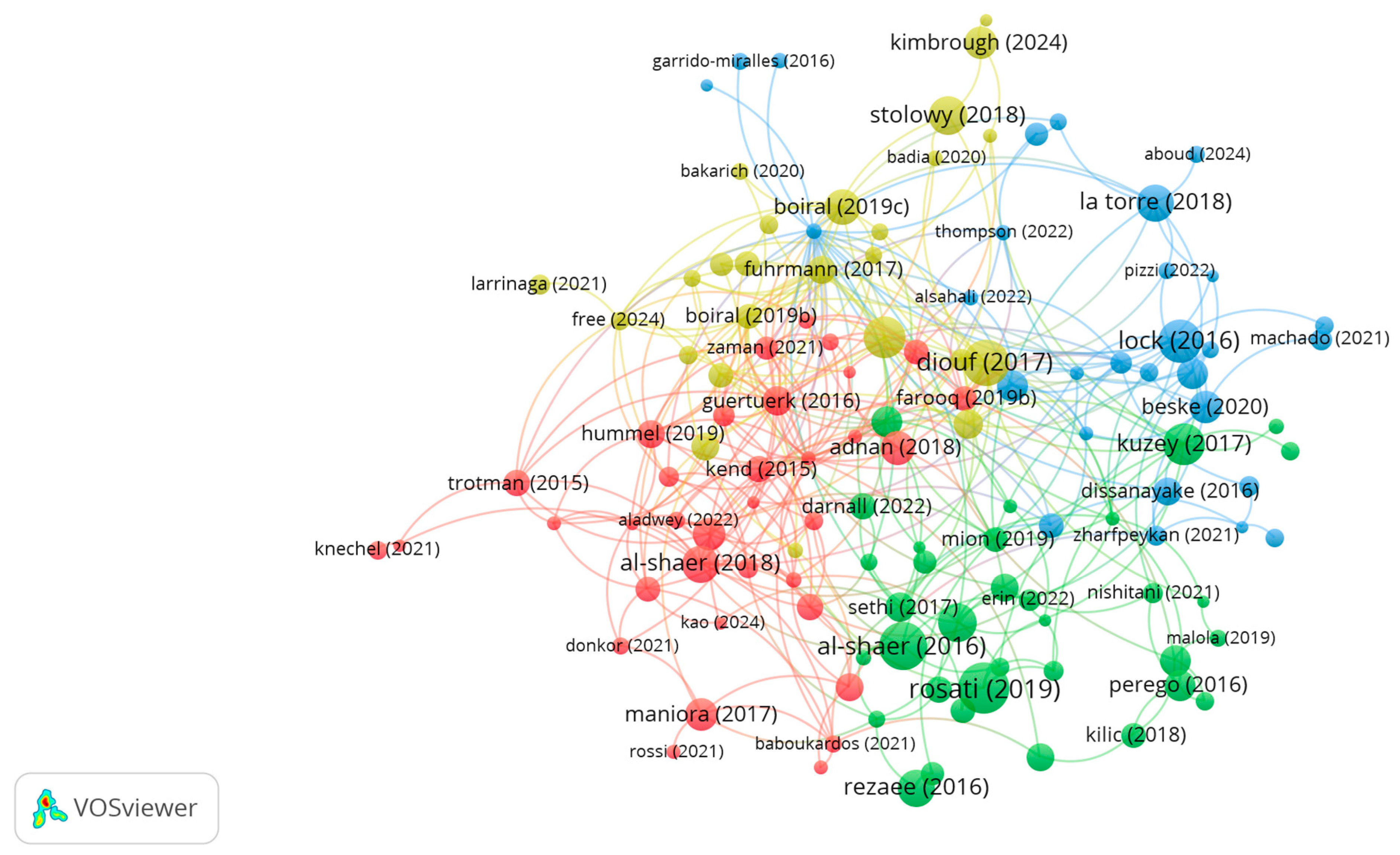

The VOSviewer program was used to obtain results regarding the identification of the most cited articles from the chosen database, selecting the “Citation” function and the “Documents” analysis unit. These are also the most dominant articles from the authors in the whole sample.

Figure 6 illustrates a series of strong links between articles from 2016 to 2020, during which the term “sustainability” gained increasing recognition among users and the GRI reporting framework was adopted by companies across all industries.

Figure 6 presents the reference citations of the most cited articles written by authors who have conducted studies on sustainability topics. The most cited articles have larger dots, their detailed presentation from each cluster is given in

Table 1. The four clusters distinguish the various approaches and interpretations that the term “sustainability” can have. The colors of each cluster were generated by software. Therefore, the authors in the red cluster are interested in the GRI and SDGs reporting frameworks, while the green cluster presents the topic studied by the authors from the perspective of corporate social responsibility. In the blue cluster, the authors discuss the relevance of assurance missions, as well as the implementation of a sustainable business in several areas of activity. The authors in the yellow cluster, on the other hand, focus on harmonizing regulatory frameworks in Europe and introducing integrated reporting practices.

By expanding the analysis of the most relevant articles, with the help of Biblioshiny, we were able to obtain a list of the ten most cited articles globally (

Table 1).

As shown in

Table 1, all articles are from the period 2016–2019, with a focus on the GRI reporting framework and the concept of corporate social responsibility. The most cited article is co-authored by Rosati [

46], the author who also has the most citations in the green cluster (

Figure 6). This study examines the relationship between the adoption of the SDG framework and several organizational factors, drawing on data from two databases: GRI and Orbis. The results indicate an increased interest in adopting the SDG regulatory framework and assurance services for sustainability reports for companies with significant intangible assets. The second article, by citations, has Al-Shaer as its co-author, who is the most cited in the red cluster. The research is based on statistical methods and demonstrates a positive relationship between gender diversity and reporting quality, particularly in the presence of female independent directors [

47]. The third article, by authors Diouf and Boiral [

48], presents stakeholders’ perceptions of investing in socially responsible companies, with the authors receiving the most citations in the yellow cluster. Through interviews with multiple stakeholders, they identified that the positive aspects of sustainability performance are often used by management to mask the negative impacts that a particular business may have on communities or the environment. From the blue cluster, the most cited author is Lock, who, together with Seele, researched the level of credibility of sustainability reporting, finding that ten years ago it was mediocre in a sample of companies from European countries [

49].

The keyword map was also created using VOSviewer to identify the most significant terms within the addressed topic. The “Co-occurrence” type of analysis was conducted in conjunction with the “All keywords” analysis unit. We selected an occurrence threshold to ensure that only terms sufficiently strong for the proposed research objective are displayed. After several attempts to reach the 10-occurrence threshold, a significant link between the selected key terms was identified. The minimum number of occurrences of a keyword was set to 10 times. After adding the “thesaurus” record stated in the research procedure section, the number of words that met the criteria was 56 items out of 1312. A lower threshold was chosen because the field of sustainability encompasses a considerable number of words (

Figure 7).

Therefore, the following words held the top positions in the three clusters: “assurance,” “quality”, and “corporate social responsibility”. Based on

Figure 7 in

Table 2, the three clusters, along with the first five keywords that determine the research direction of each article in the database, are presented.

Table 2 shows that Cluster 1 (green) focuses on assurance engagements over the sustainability statements. Moreover, the focus of this cluster is on the reporting process through relevant sustainability disclosures. The data has been collected and corroborated by managers from several key departments, including HR, Compliance, Safety, and Environment, to inform the final form of the sustainability report. Cluster 2 (red) highlights the importance of responsible behavior by companies that engage with affected communities. Additionally, it emphasizes the holistic approach to sustainability reporting by focusing on both internal (company size, strategies, and objectives, as well as field of activity) and external (legislative frameworks, market and competitors, and stakeholders) determinants that can influence the presentation of non-financial information. The last cluster (blue) specifies the same key characteristics of ESG reporting, offering an internal positive perspective that aims to transition the business to a more sustainable one. These activities bring financial benefits to companies, making them more attractive to investors and enhancing their brand.

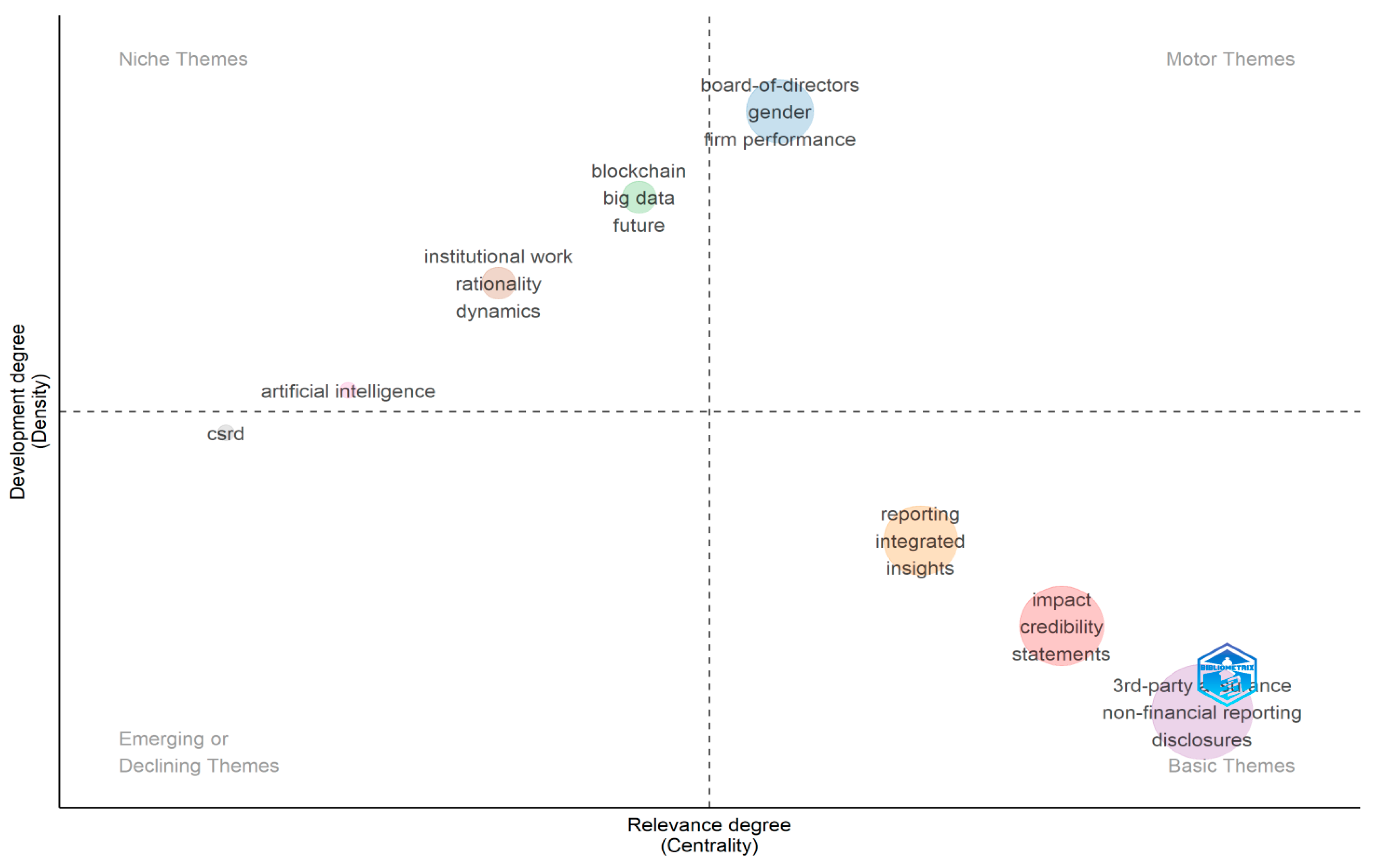

Moreover, our analysis includes a thematic map generated using Biblioshiny to understand the most relevant topics in the sustainability field and their stage of development. A thesaurus file was also used for the list of synonyms, and another.txt file was used to exclude words such as country names. The two axes of the map represent the degree of interaction of a topic with others in the same field (centrality) and the strength of a topic’s development (density).

Figure 8 presents elements found in each of the four quadrants, highlighting the diversity of the research field and identifying areas that are particularly relevant or that have potential for expansion.

Figure 8 reveals that the first quadrant is assigned to the niche topics. It highlights well-developed topics that are marginal to the study’s field. Here, we can mainly see topics related to artificial intelligence, big data, and blockchain, which are becoming increasingly indispensable in the context of the emerging economy. With the help of technology, the process of measuring and reporting sustainability indicators is done more efficiently. Additionally, the assurance engagements can be facilitated by a series of artificial intelligence-based programs. The second category comprises central topics that have a significant impact on sustainability and are well-developed. This category, as shown in

Figure 6, encompasses a company’s performance, gender diversity, and the composition of its board of directors. Nowadays, companies need to focus on two types of performance, financial and non-financial, to develop and maintain a sustainable business [

52,

55]. At the same time, current trends highlight a growing concern for inclusion and diversity, which is why gender discrimination is a topic that companies carefully examine. As a result, among the metrics disclosed by companies is the number of women on the board of directors, in top management positions, and in various other key positions in production processes. The third quadrant underlines emerging or declining themes. It is considered that the term “CSRD” is in full development as a subject underlying the field of sustainability, being a reporting framework used by a wide variety of European companies [

54]. Already in force and replacing the NFRD, CSRD represents the focus for many practitioners. Lastly, the fourth quadrant highlights topics that are important to the field of study but are not sufficiently developed, serving as ideas for future research. Integrated thinking, a multi-perspective approach to ESG issues, and information disclosure are phrases that support sustainability reporting. These statements have a significant impact on the decisions that stakeholders or other users make. Credibility and reliability are mainly ensured by independent auditors who perform a series of tests on the qualitative and quantitative indicators included in the reports. Therefore, the concept of assurance and the process of preparing the sustainability report can be considered key topics that require further study by researchers [

56].

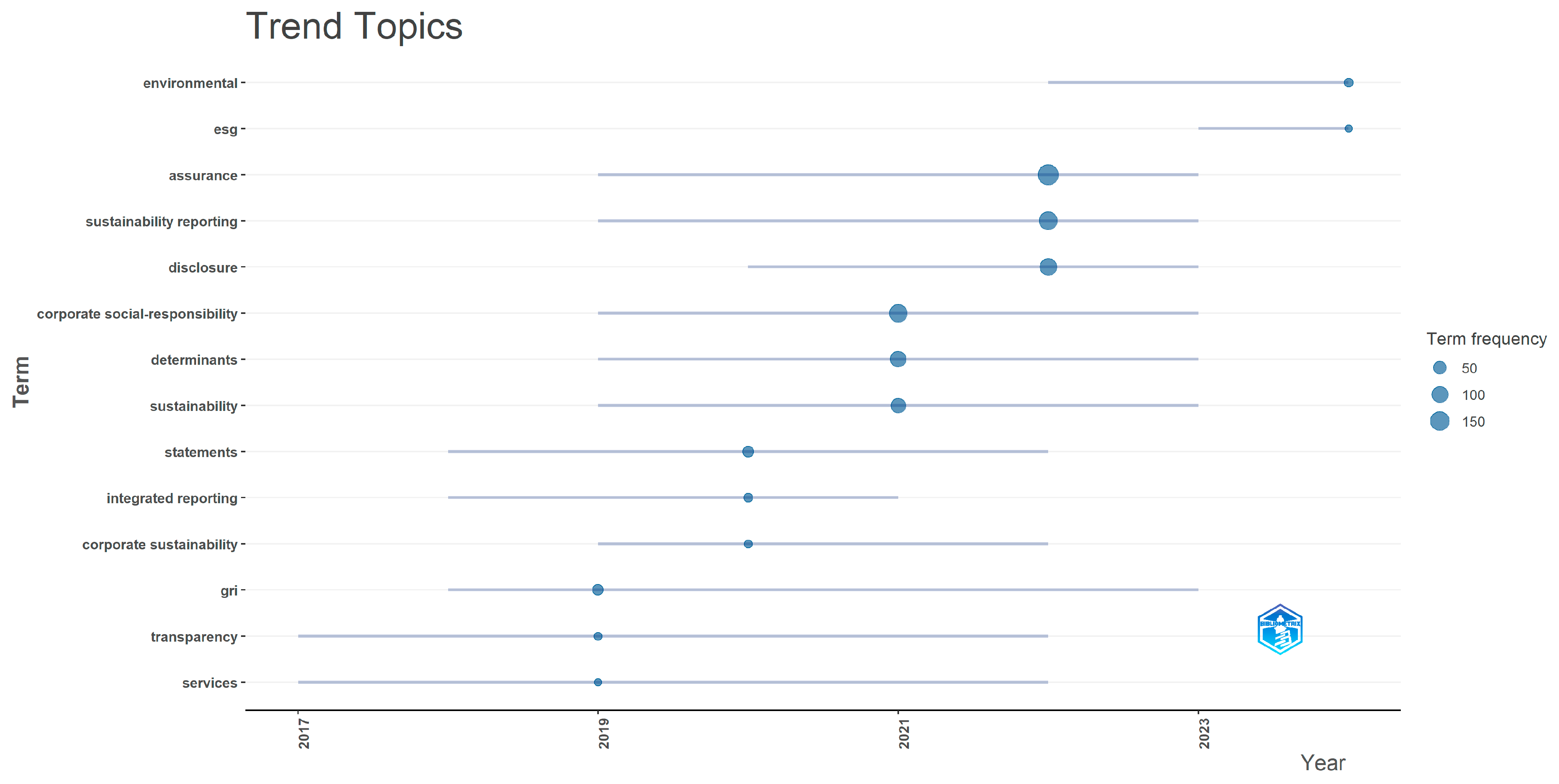

The graphics in

Figure 9 illustrate the evolution of several key terms related to the reporting and assurance of sustainability statements, which are presented on the vertical axis. The size of the bullet points indicates the frequency of each word during the time frame from the horizontal axis.

Therefore, based on

Figure 9, the terms “environmental” and “ESG” emerged when the CSRD was adopted. Additionally, we can observe that for a considerable period, “gri”, “transparency”, and “services” were focal points for researchers who sought to emphasize the importance of comparability between reports, the transparent disclosure of information, and the necessity of high-quality reporting services [

53]. Nonetheless, the topics of “assurance”, “sustainability reporting”, and “corporate social responsibility” have the highest frequencies, and they are the most pertinent for our research.

Previous studies that have included bibliometric analyses have demonstrated the diverse interpretations of the term “sustainability” and the potential for extending research to various areas, such as sustainable development, urban sustainability, ecological footprint, and climate change [

38]. Similarly, Rathore et al. [

56] identify the same countries as relevant to the analysis of sustainability, namely the US, Italy, the UK, and Germany, and also introduce the concept of “ergonomic” sustainability. This element also refers to the social component through increased productivity, reduced stress, and maintaining good physical health. In terms of assurance missions, Johri & Singh [

57] undertake a bibliometric analysis, which yields results similar to those demonstrated in this study. Average annual production shows the highest growth in 2023, followed by a slight downward trend. Another similar result is related to the keywords in the field of auditing that appear in both bibliometric analyses: “assurance,” “disclosure,” and “determinants.” Lastly, the prospect of digitization, including the implementation of artificial intelligence in the design and auditing of sustainability reports, as well as the two types of company performance (financial and non-financial), is confirmed by the study conducted by De Silva Gunarathne & Kumar [

37].

In response to RQ 1, as evident from the bibliometric analysis, there has been a significant evolution in the process of sustainability reporting over the past decade. Several frameworks emerged from stakeholders’ needs for a broader understanding of businesses and more transparent disclosure of information. Moreover, as greenwashing can be considered a form of fraud in sustainability statements, the importance of assurance engagements has increased.

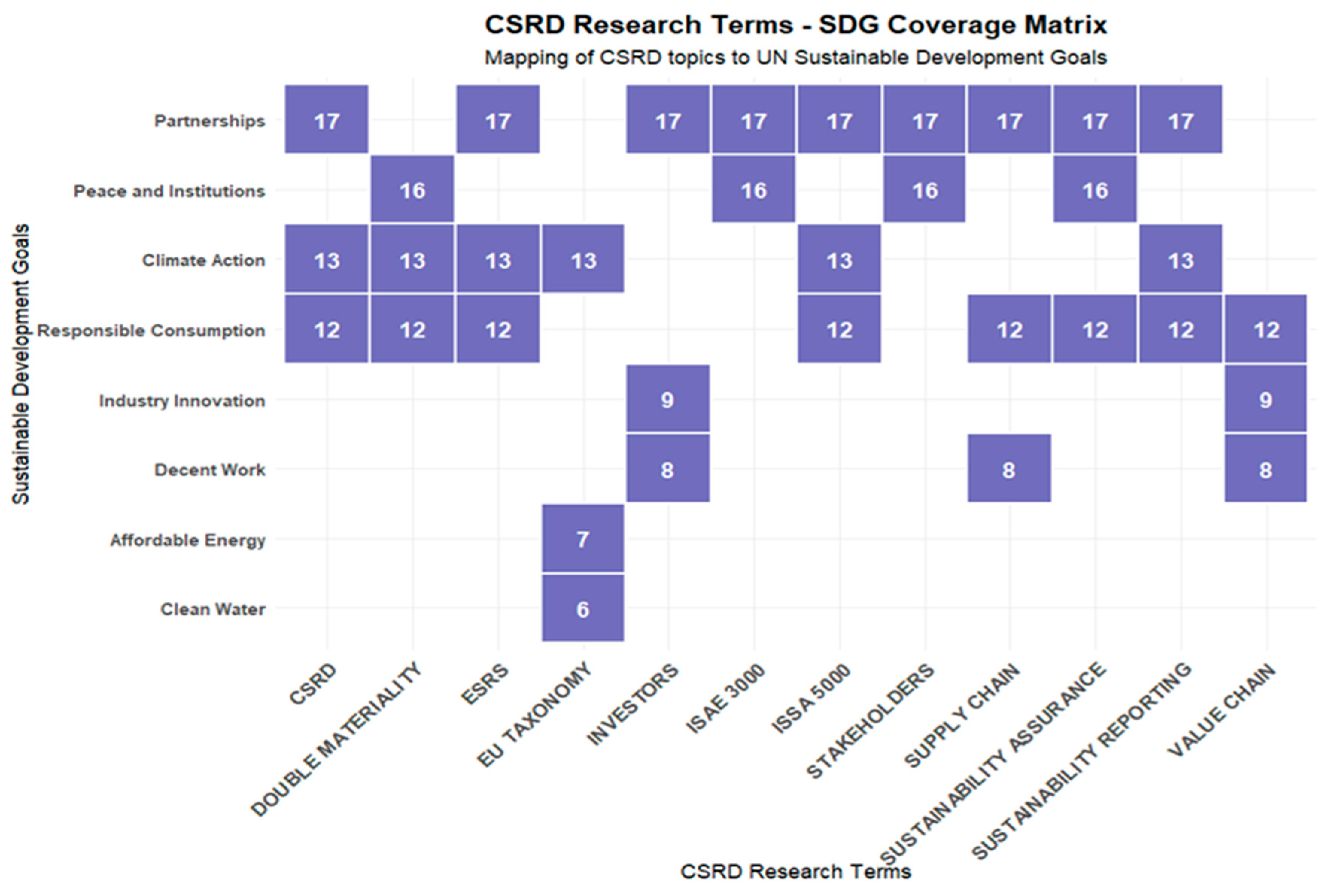

The CSRD-related research terms aligned with specific SDGs were analyzed to answer the second research question (RQ2).

The results of the performed integration are presented in the figures that follow.

Figure 10 presents the matrix of CSRD Research terms and their coverage in the SDGs.

Figure 10 illustrates how academic research related to the CSRD, utilizing our data frame, aligns with the SDGs, indicating which SDGs are most frequently discussed in CSRD-related research articles published between 2015 and 2025. The findings indicate that SDG 17, the Partnership for the Goals, is one of the most mentioned goals in the survey research, followed by SDG 12, Responsible Consumption and Production. This makes sense, as the CSRD directly focuses on how companies operate, utilize resources, and manage their supply chains—all core aspects of this goal. “Climate Action” is in third place, reflecting the central role of the climate change perspective in corporate sustainability reporting.

The intense focus on the three goals—SDG 12, SDG 13, and SDG 17—shapes the CSRD implementation’s “core triad”. ESRS, as the leading standard of CSRS, complies with the same SDGs as CSRD.

ISAE 3000, as a standard for assurance engagements, is aligned with SDG 16 because assurance serves as a fundamental mechanism for building trust and ensuring institutional integrity. It guides the verification of reported information to ensure its credibility, strengthening the accountability of corporate institutions. Additionally, it aligns with SDG 17 because the assurance process itself is a partnership among the assurer, the company, and the report users as a collaborative activity that supports the reliability of the entire reporting ecosystem. Therefore, ISAE 3000 is regarded as an anchor of institutional transparency and accountability, core values of SDG 16. ISAE 3000 is a procedural standard, not an operational one. It does not measure emissions or resource efficiency (SDGs 12 and 13). Instead, it ensures that information regarding these issues is verifiable and reliable, clearly placing it within the domain of governance and institutions (SDG 16).

ISSA 5000 is one of the most relevant initiatives in the context of CSRD and ESG–SDG reporting. It is linked to SDG 17, representing a collaborative activity, and SDG 13 arises from the requirement for rigorous verification of data on GHG emissions, climate risks, and decarbonization strategies. ISSA 5000 is also linked to SDG 12 by the verification of indicators related to energy efficiency, resources, waste, circularity, supporting responsible production and consumption practices. ISSA 5000 is indirectly connected to SDG 16, as it serves as a technical standard applied by assurance professionals to corporate reporting.

The stakeholders’ term is mapped to SDGs 16 and 17, as inclusive stakeholder engagement is a key principle of good governance and just, inclusive institutions, and as stakeholder engagement is the essence of partnership. The stakeholder term is not related to SDG 12, being seen more as a governance and partnership mechanism rather than a direct driver of consumption patterns.

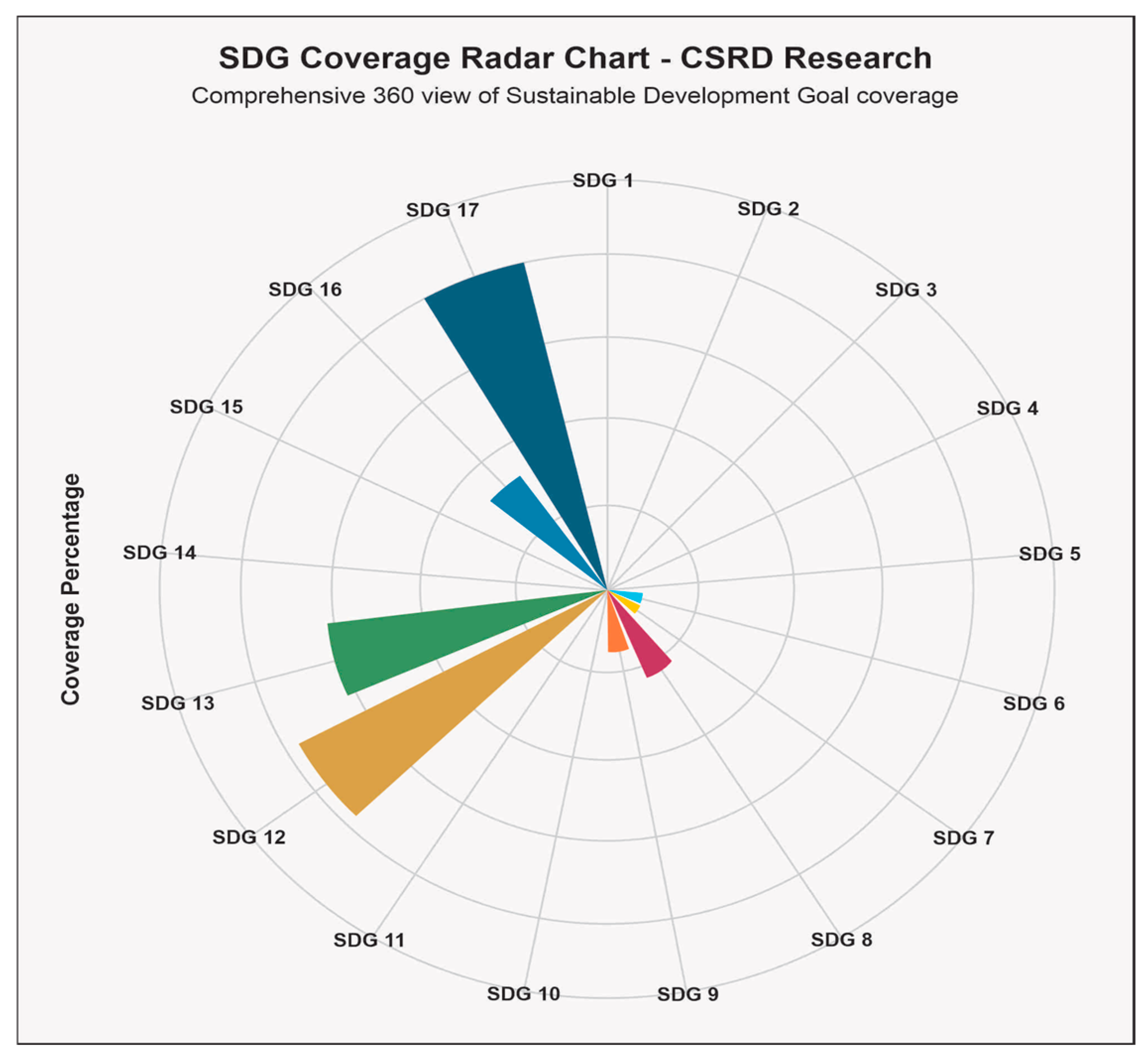

Figure 11 shows a radar diagram of SDG Coverage in CSRD-related research. The colors in the figure correspond to the official colors of the SDG-UN to reflect the correspondence with the priorities of the 2030 Agenda. The same colors will be used in all figures in the paper.

According to

Figure 11, the results indicate that SDG 17 had the highest frequency, followed by SDG 12 and SDG 13. Goals such as “no poverty,” besides “zero hunger,” “life under water,” and “gender equality”, have the shortest bars, indicating that they are discussed less frequently in the context of CSRD-related terms research. This suggests that the current research focus is more on environmental and governance issues directly related to corporate operations, rather than broader social issues. The chart highlights that while CSRD research encompasses a wide range of SDGs, its primary focus is on the goals most directly influenced by corporate operational and reporting practices.

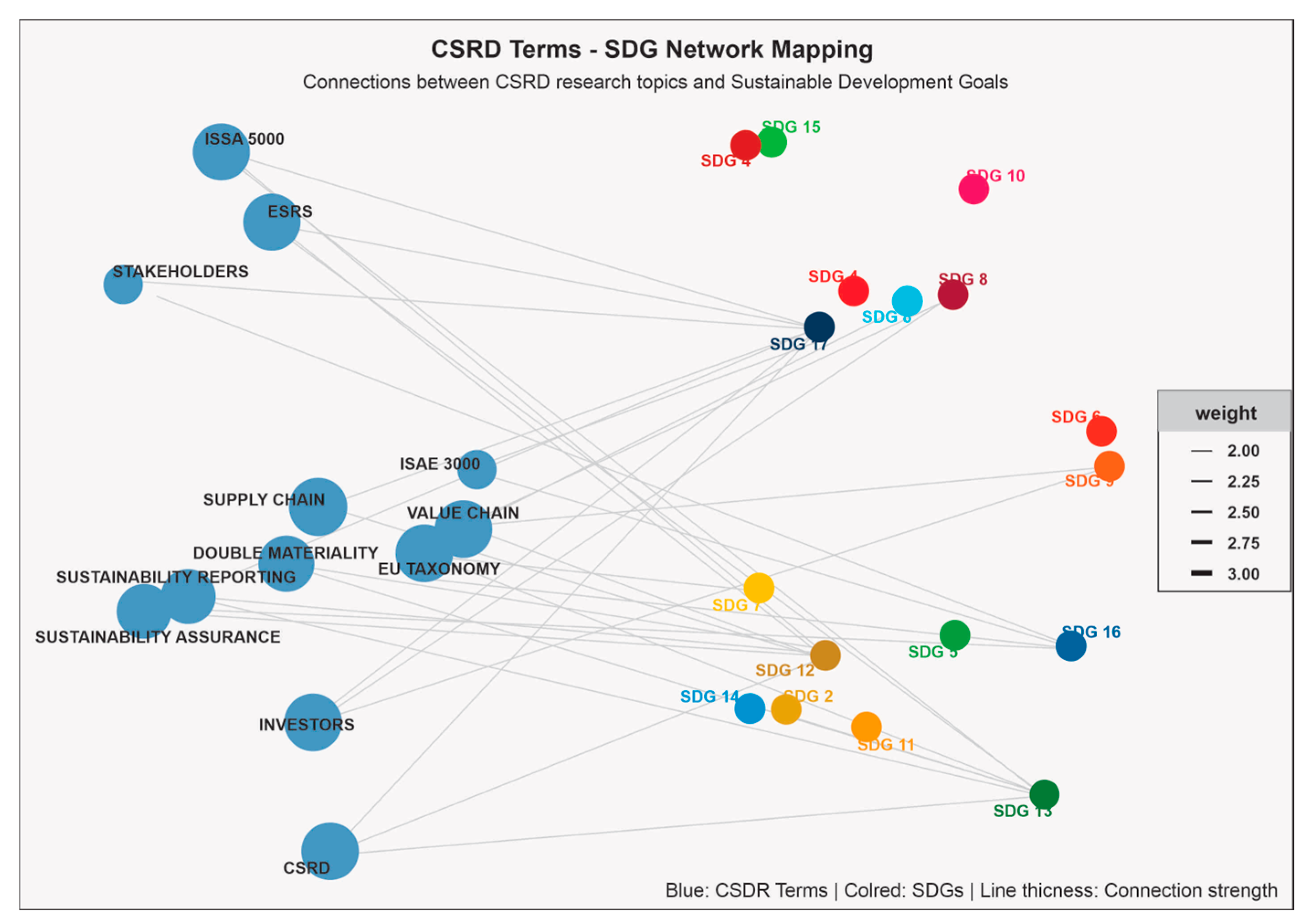

The network mapping, pointing out the visualized connections between selected CSRD-related terms and the UN SDGs, is presented in

Figure 12.

The blue nodes, representing CSRD-related terminology and concepts, are connected to the colored nodes, which represent specific UN SDGs (

Figure 12). The connection strength is quantified through a weighted scale. The figure illustrates that corporate sustainability reporting is not an isolated exercise but is intrinsically linked to achieving goals such as climate action (SDG 13) and responsible consumption (SDG 12), among others. By using this mapping, stakeholders can identify which areas of sustainability reporting have the strongest relationships to specific global goals, helping with strategy alignment, materiality assessment, and effective communication.

Figure 13 illustrates the network mapping, highlighting the visualized connections between selected CSRD-related terms and the UN SDGs.

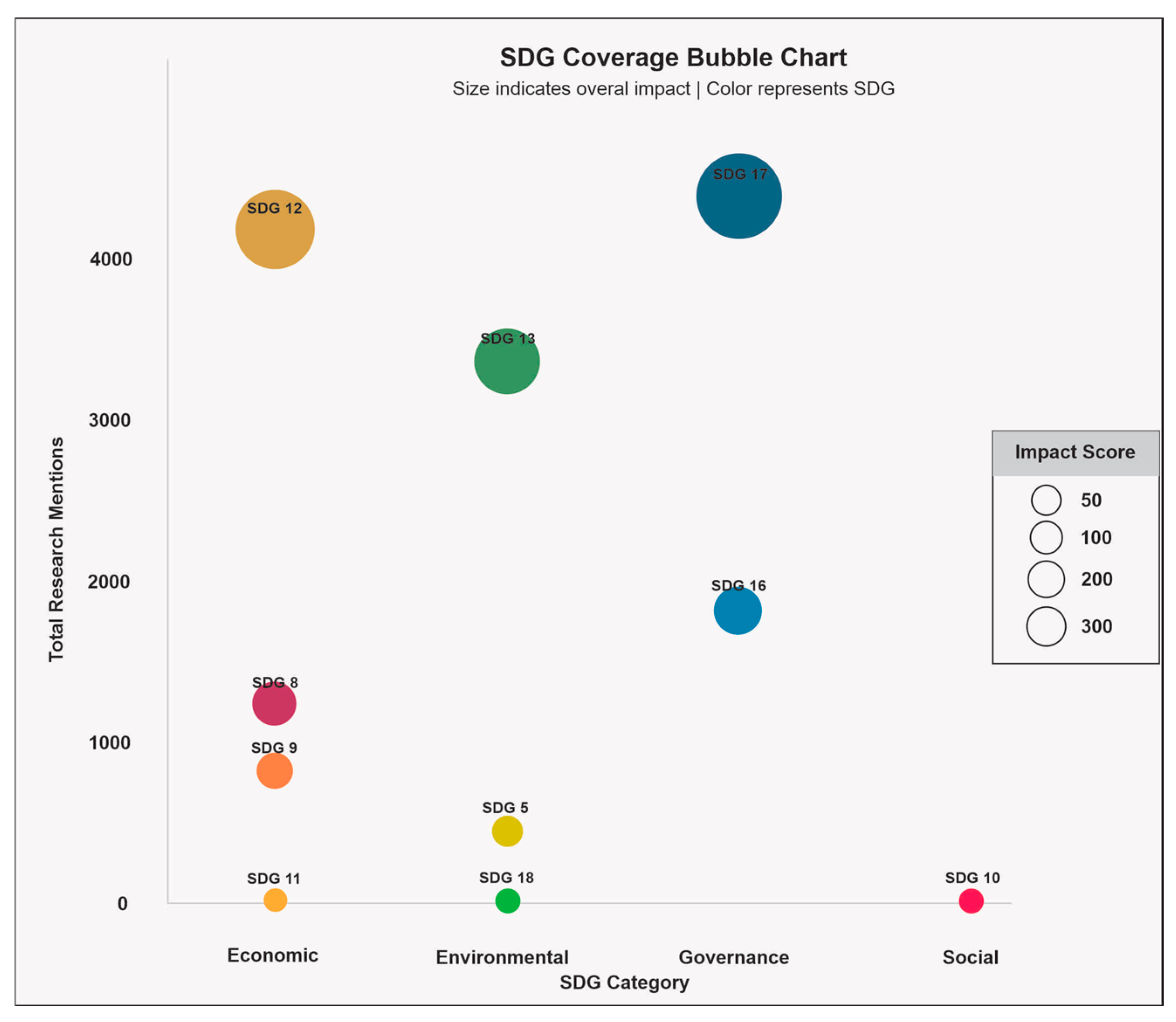

The bubble chart results are shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, which were generated using the ggplot2 package [

58]. In these charts, the size of each bubble is proportional to the calculated Impact_Score, and the color of each bubble corresponds to the official SDG color.

This visualization provides a natural representation of how research coverage, thematic coverage, and overall impact are distributed across the Sustainable Development Goals within the CSRD domain, answering the second research question (RQ2).

To get further and to find out more about the forecasted trends and the strategic priority areas for future research and business investment to strengthen the ESG-SDG nexus, answering the third research question (RQ3).

Table 3 presents the data on the Ensemble Average model’s performance, which combines ARIMA, ETS, and Linear Regression with SDG Factors.

The forecasting models discussed in

Table 3—ARIMA, ETS, and Linear Regression—all involve stochastic (random) elements. The ensemble approach aims to mitigate the impact of this randomness by combining multiple models, thereby improving accuracy. The model utilizes optimized weights based on inverse squared errors, a method also commonly found in the research literature [

20]. The detailed results of ARIMA, ETS, and Linear Regression components are presented in

Appendix A (

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3).

The ensemble weighting results with 40%, 35% and 25% (

Appendix A,

Table A4) achieve the best overall performance (as seen with the lower Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 6.3% and higher R-squared of 0.94), better than individual models:

- -

ARIMA -MAPE 8.2%, seasonal patterns—seasonal AR = 0.23, p < 0.05, stable positive trend (drift = 0.15, p < 0.01).

- -

ETS -MAPE 9.1%.

- -

Linear Regression with SDG Factors—MAPE 7.8%, significant regulatory drivers (+8.73, p < 0.01).

The ETS model proves its effectiveness in handling error structures, trend variations, and seasonality, complementing ARIMA by addressing different aspects of time series volatility. The assigned weight is slightly lower than that of ARIMA, due to its slightly higher MAPE, but it still contributes significantly to reducing the overall ensemble error.

Linear Regression incorporates important external drivers (e.g., SDG alignment, regulatory impact), but it does not fully capture time series dynamics on its own. The lower weight helps balance the ensemble by adding explanatory power without overshadowing the time-based models, thus reducing the risk of model-specific biases. The significant impact of SDG factors (

p < 0.001) (SDG Alignment: +12.45 articles/alignment point, Weighted SDG Score: +15.62 articles/score point) means that each unit increase in SDG alignment generates approximately 12 additional scientific articles per year. The coefficients from

Table A3 (Linear SDG Coefficient) indicate which factors are expected to drive the most future research activity. The SDG Alignment Index has a coefficient of +12.45 *** (

p < 0.01). We interpret this as a key term that aligns very well with the SDGs (e.g., ISSA 5000 is aligned with SDGs 12, 13, 17), which will attract, on average, 12.45 supplementary research articles per year for each supplementary alignment point.

Our finding of 6.3% MAPE in sustainability forecasting compares favorably with established benchmarks in the field [

44,

59], while the ensemble approach addresses methodological gaps identified in the recent literature [

60,

61].

All validation tests were successfully passed, indicating a robust econometric validation (Stationarity:

p < 0.01 for all models, no residual autocorrelation:

p > 0.05, residuals normality:

p > 0.05, reduced multicollinearity: maximum VIF = 3.2), and are presented in

Table A5 from

Appendix A.

The key findings are presented in

Table 4.

Table 4 presents statistical findings, quantitative evidence, and practical implications for researchers, investors, and businesses. It serves as a guide using the ensemble model, which has been proven to provide 28% variance reduction versus single models, making it more reliable for strategic decisions.

Table 5 presents the forecast outcomes.

As regards the data from

Table 5, the 5-year forecast, we found out that the top 3 research domains are:

- -

CSRD has an expected amount of 85 articles/year, reflecting its centrality in sustainability research.

- -

ISSA 5000, with 78.3 articles/year, indicating superior attention to specific sustainability assurance standards.

- -

Sustainability reporting, as a general umbrella, with 68.3 articles/year, indicates a mature and constantly expanding field.

The CSRD term growth rate (+15.3%) reflects progressive implementation, along with the concept of double materiality (+11.2%), which represents an emerging concept with high research potential.

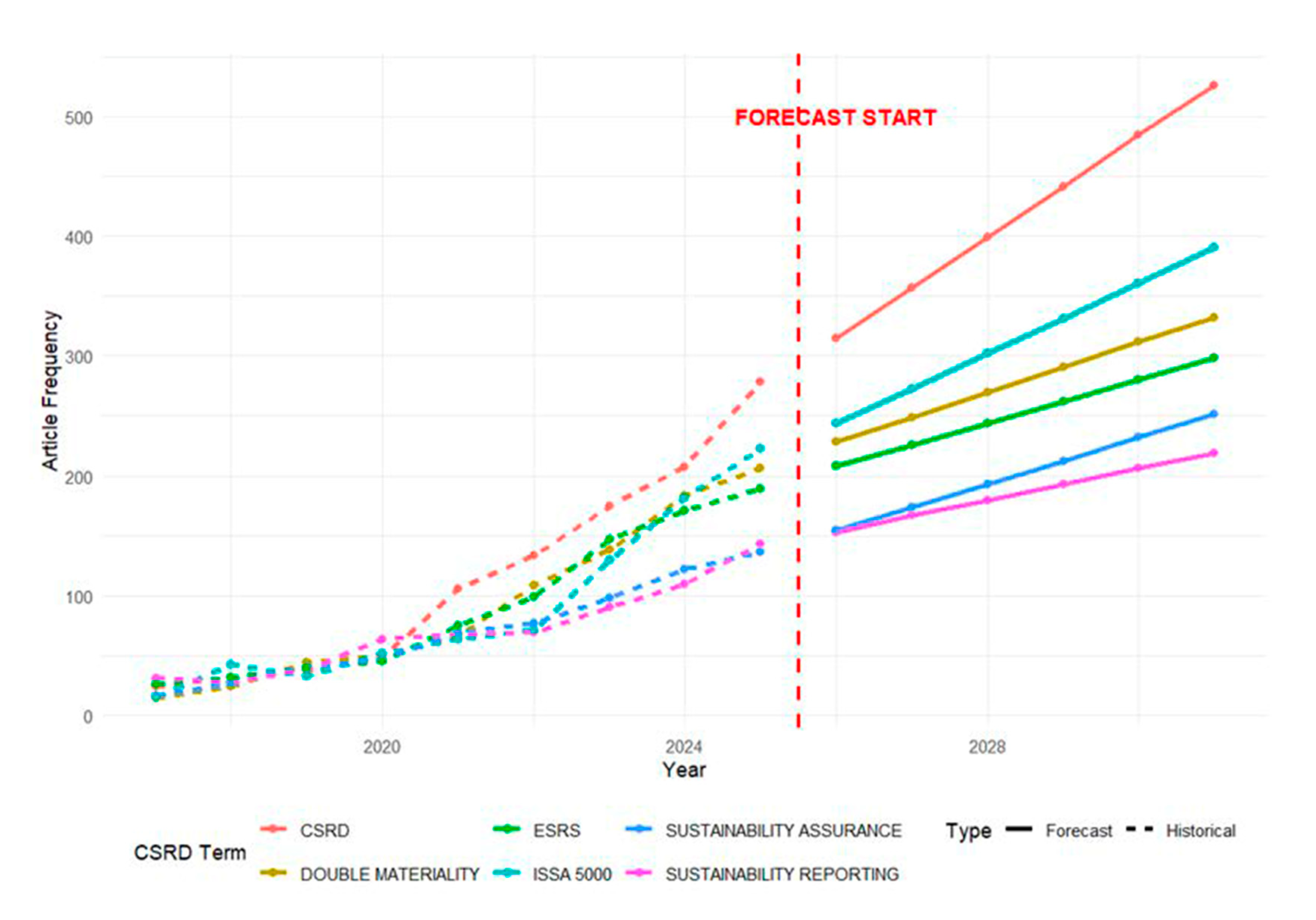

The graphical representation of the forecast of the most used CSRD terms is shown in

Figure 14.

The findings from the forecasting (

Figure 14) indicate an increasing impact of research related to CSRD and ISSA 5000 regulations, which are the primary drivers of an enhanced ESG-SDG nexus and the double materiality concept, encompassing both internal and external impacts, risks, and opportunities over the next several years.

Table 6 presents the annual evolution of each term.

The gradual decline in growth rates, from +4.8% in 2026 to +1.9% in 2031, presented in

Table 6 indicates the field maturation. This forecasting model enables us to conclude that, despite the complex challenges it presents, it also offers multiple opportunities. From a governance perspective, it enables evidence-based policy design that is responsive to evolving sustainability trajectories. From an investment and corporate strategy view, it facilitates the identification of high-impact domains where ESG performance aligns with SDGs objectives. Furthermore, by highlighting data-driven validation and temporal robustness, the model delivers a transparent and adjustable base for tracking progress toward sustainability commitments. While panoramic studies [

62] mapping the ESG field, our analysis is strategically focused on the CSRD/ESRS regulatory nucleus and its assurance mechanism (ISSA 5000), offering a granular perspective on the specific drivers of ESG-SDG integration. Perumandla et al. [

16] employ thematic modelling with LDA in their research on the ESG-SDG nexus, thereby extending beyond descriptive bibliometrics. In accordance with these further directions, our study demonstrates that advanced forecasting and feature engineering techniques can play a crucial role in harmonizing ESG implementation with SDG achievement, transforming sustainability from a compliance-driven obligation into a strategic, innovation-oriented process, thereby responding to the third research question.

To identify the strategic fields as an answer to RQ3, based on forecasts, we identified two priority categories:

Tier 1—Critical, with high absolute volume and strong alignment with SDG, as represented by CSRD (85 articles/year), which serves as the regulator nucleus. Research on its implementation will dominate, and ISSA 5000 (78.3 articles/year) represents the new milestone of sustainability assurance. Its high alignment with SDG 12, 13, and 17, as well as the practical need to combat greenwashing, makes it highly strategic to both researchers and practitioners.

Tier 2—High Potential—Explosive Growth: Double Materiality (+11.2% growth) is the concept that defines corporate materiality. Its rapid growth indicates an emergent academic niche with a high potential to transform strategic practice.

To conclude the answer for RQ3, we state that the priority strategic domains to meet the ESG-SDG nexus are:

Implementation and CSRD mechanisms as a guidance framework

The assurance of the reporting credibility through ISSA 5000 as a key instrument for verification.

Operationalization of the double-materiality concept (as a paradigm for strategic analysis).

They are a priority for: 1. researchers—these are the domains with the highest predicted volume and the fastest growth in publication, offering a fertile field for scientific contributions; and 2. investors and companies—these are the practical liaison between regulations (CSRD), assurance (ISSA 5000), and strategy (double materiality), which impacts the SDGs performance and alignment directly. The investment in these capacities will generate resilience and strategic opportunities.

Finally, we transformed historic bibliometric data into a strategic navigation map for the future, showing not only what was researched, but also where the research focus and innovation will be in the future years.

5. Conclusions

The first conclusion that can be drawn from the literature review is that ESRS are undergoing an ongoing process of updating them, making them increasingly easier to understand for their users. With respect to this matter, at the beginning of 2025, two new updated sets of regulations were introduced, aiming to reduce the number of disclosure requirements and facilitate the transition to CSRD. As the current ESRS requirements are rigorous and sometimes vague, the European Commission has planned an “omnibus” substitute to streamline them. Therefore, efforts are being made to facilitate the sustainability reporting process and to make it as smooth as possible for every company subject to the CSRD. On the other hand, assurance engagements on sustainability reports are also becoming increasingly common. To support practitioners, the IAASB proposes a new standard (ISSA 5000) to be used exclusively in assurance engagements on sustainability statements, focusing more on current needs.

The second conclusion is based on the bibliometric analysis performed on a sample of 361 research papers from the Web of Science—Clarivate database. Over the studied time frame, there is noticeable progress in citations and publications. This highlights the significance that researchers hold in the field of sustainability, particularly since the adoption of the ESRS. However, the bibliometric analysis indicates that the period from 2016 to 2019 had the most cited and relevant articles. Thus, the literature on the new ESRS regulations and assurance engagements remains limited, which may contribute to uncertainty among practitioners. Additionally, countries worldwide that prioritize sustainability are primarily from developed economies [

51]. Gradually, territories with less developed economies should integrate the concept of sustainability into their practices.

RQ1, based on the dynamics of bibliometric cartography, underlies the rapid adaptation of academic research to regulatory innovation. As an answer to RQ2, the alignment analysis demonstrated that the research nucleus of CSRD is strategically focused on SDG 12 “Consumption and responsible production”, SDG 17 “Partnerships”, and SDG 13 “Climate action”, forming a central triad. Through the analysis of these terms, ISSA 5000 and sustainability assurance are noted for their strong alignment with the SDGs and their trajectories of increase, indicating their status as emerging research frontiers.

Addressing RQ3, the forecasting model identified priority fields for investments and future research. The multi-model ensemble approach (ARIMA, ETS, and linear regression) demonstrates superiority over individual models, capturing the full spectrum of temporal patterns, and the SDG factor integration significantly improves predictive accuracy. The research suggests practical relevance for researchers, highlighting that research in CSRD and sustainability assurance will remain active over the next several years, with ISSA 5000 emerging as a significant new research opportunity.

The research highlights that practitioners and regulators should prioritize investments in CSRD and ISSA 5000, as the primary drivers of the ESG-SDG nexus, which advances sustainability and stimulates research interest.

The evolution of CSRD-related terms followed the development of regulations, with their mapping aligned with new developments in the framework, in accordance with the SDGs’ objectives. Therefore, there is a shift in the audit activity, progressing from ISAE 3000 to ISSA 5000, with a more specific focus on sustainability orientation. Moreover, our forecast ensures strategic planning, enhancing policy implications that rely on the regulatory frameworks (CSRD, ESRS) that continue to guide the research agenda. Specific assurance standards (e.g., ISSA 5000) are gaining strategic importance, and the double materiality concept, along with the value chain transition perspective, occurs as a high-potential domain for future exploration.

This research adds three main contributions: 1. It offers an integrated methodology between retrospective cartography and quantitative forecasting, 2. Points out the ESG-SDG nexus through their alignment and 3. Generates a strategic guide, classifying the research and investment domain on volume, alignment, and increase dynamics criteria.

The practical implications are directly related to (a) researchers, as they have a clear agenda with fertile domains for theoretical and empirical contributions, (b) practitioners and investors, pointing out the necessity of the priorities in strategic analysis to obtain resilience and SDG alignment, and (c) regulators, as the empirical validation that SDG alignment is the primary driver of the research, offer a supplementary justification for coherent policies that enforce this nexus.

The research has specific limitations related to its focus on the European context rules. Proposing for future research to expand the research to the global context and also enhance pattern detection by analyzing macroeconomic and geopolitical variables using deep learning models.

In conclusion, this study transforms the ESG-SDG nexus from a descriptive analysis into an informed strategic planning domain, demonstrating that predictive integration is the next necessary step towards consolidating companies’ alignment with the 2030 Agenda. Moreover, as developing countries have a significantly reduced impact on citations, they require differentiated scientific policies and specific strategies to enhance their visibility and international research relevance.