Abstract

Social media has become the core channel through which people communicate, and the important role of influencer marketing in creating a fan base for brands is widely recognized. Grounded in Source Credibility, Homophily Theory and Signaling Theory, the purpose of this study is to investigate how influencer efficacy affects the fan effect of green food brands under digital social media. This paper adopts a quantitative research method. A cross-sectional survey was conducted on the Wenjuanxing platform and collected 417 valid responses from consumers who had previously purchased green food based on an influencer’s recommendation. A conceptual model was tested through the structural equation modelling procedure. The results showed that professionalism (β = 0.166, p = 0.011), trustworthiness (β = 0.291, p < 0.001), and similarity (β = 0.267, p < 0.001) had positive effects on perceived quality. Furthermore, perceived quality (β = 0.333, p < 0.001) significantly promoted the formation of the brand fan effect and partially mediated the effects of these characteristics of influencers on the brand fan effect. This study provides new insight into the fan effect of green food brands and also provides a theoretical basis for green food companies to accurately match their brands with suitable influencers, enhance the brand fan effect, and rationally formulate operational strategies.

1. Introduction

As Internet penetration deepens and user engagement on digital platforms grows, social media has become an integral part of everyday communication. Continuous innovation in digital technologies has reshaped how information is produced and disseminated, fostering the emergence of social media influencers as important opinion leaders in consumer markets. Empirical studies show that influencer efficacy, such as professionalism, significantly shapes consumer attitudes, perceived value and purchase intentions, extending classic source credibility theory to social commerce contexts [1]. In parallel, research on parasocial interaction and fan economy indicates that closer influencer–follower relationships can enhance stickiness and fan growth, thereby amplifying marketing effectiveness in digital environments [2,3,4].

Against this backdrop, short-video and livestreaming platforms such as TikTok/Douyin have facilitated the rapid rise in Chinese influencers, including Yuhui Dong and Qiqi, whose live-commerce practices integrate entertainment, real-time interaction, and product recommendation to drive sales [5]. Companies such as East Buy have incorporated such influencers into their branding strategies to create differentiated brand value, enhance the distinctiveness of their food products in a highly competitive market, and increase consumer engagement. In China’s agricultural food sector, this is particularly salient for the promotion of green food. The certified green food market in China has expanded steadily in recent years, reaching an estimated RMB 380 billion in sales in 2023. The Green Food Certification system, together with Organic and ESG labels, establishes regulatory standards for safety, traceability, and sustainability. Following the definition of the China Green Food Development Center, green food refers to products that comply with national green food standards, emphasizing environmental protection, reduced agrochemical use and food safety [6]. Accordingly, green food brands in this study are defined operationally as food brands that market products bearing the official Green Food certification label (e.g., certified rice, tea, fruit, and processed grain products commonly sold on Chinese e-commerce and livestreaming platforms) [7].

Recent studies on green labels and green advertising further suggest that credible environmental cues and persuasive communication can increase green perceived value and trust, reduce perceived risk and price sensitivity, and ultimately strengthen purchase intention for green foods [8]. In this context, influencers like Yuhui Dong and Qiqi engage audiences with brand-related content through livestreams and short videos, activate fan identities, and embed green food products in narrative and interactive formats. And influencers’ first-hand experiences are persuasive. By sharing authentic personal experiences, influencers provide experiential cues that help consumers reduce uncertainty and form vivid product expectations. Compared with other eco-friendly product categories, such as sustainable fashion or zero-waste household products, green food is more strongly characterized by health, safety, and environmental credence attributes, for example, organic production, reduced pesticide residues, and low-carbon farming practices, which consumers cannot reliably verify even after purchase and consumption [9,10]. Because of this credence nature and the frequent food-safety scandals reported in many markets, consumers face heightened uncertainty and perceived risk when evaluating green food claims and are therefore especially dependent on trusted interpersonal information sources, rather than only on labels or firm-generated messages, to form quality perceptions and close relationships [11,12]. Enhancing influencer efficacy on social networks is therefore crucial for expanding consumer demand for green food brands, building strong brand–consumer relationships, and improving the overall efficiency of green food branding and communication.

Research on influencer efficacy has become an important topic in the field of digital marketing, and in-depth explorations have uncovered the multi-dimensional impact of influencers on brand communication, consumer behavior, social identity, and other aspects. Many studies have demonstrated that influencer trustworthiness plays a pivotal role in shaping consumer responses. For example, Han and Balabanis [13] found that trustworthiness and expertise of social media influencers significantly shape attitudinal outcomes. On this basis, we also focus on similarity as the central construct, because similarity reflects perceived social connection and identity alignment between the influencer and the follower. Consumers are more likely to be persuaded by communicators whom they perceive as similar to themselves in values, lifestyles, and beliefs. Studies have shown that the perceived effectiveness of influencers not only directly affects the recognition and understanding of a brand (brand cognition) and behaviors such as purchase intention, but is also closely related to the degree of interaction between influencers and their followers as well as the emotional connection they share [14,15,16,17,18]. From the perspective of research content, although there are many studies on the impact of influencers on brand image and loyalty, there is still a lack of information on their impact on the fan effect of green food brands.

To address these limitations, this study identifies and fills a gap in existing research on green food marketing, namely the lack of a systematic understanding of how influencer efficacy drives the fan effect of green brands. Prior studies have predominantly focused on consumers’ motivations (e.g., environmental awareness, health consciousness, green knowledge) and decision-making processes (e.g., attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control) leading to purchase intentions or behavior [7,8,19,20]. By contrast, limited research has explored how influencer efficacy as a key driver of the fan effect in green food brand communication, specifically examining how distinct dimensions of influencer efficacy shape consumers’ perceptions of green food quality and foster the fan effect in green food branding. Guided by Source Credibility, Homophily Theory and Signaling Theory, this paper conceptualizes influencer efficacy and its components and develops hypotheses on their direct effects on the fan effect of green food brands. Furthermore, perceived quality is introduced as a mediating variable to explain the psychological mechanism linking influencer efficacy and the brand fan effect. Theoretically, this study extends existing influencer marketing literature by integrating influencer efficacy and perceived quality into the green consumption domain, thereby deepening the understanding of how influencer efficacy drives the fan effect in sustainable brand communication. It also differentiates itself from prior research by shifting the analytical focus from consumers’ internal motivations to influencers’ external impact, thereby uncovering the black box of fan formation in green food marketing. Practically, our findings provide actionable insights for green food enterprises to identify the key dimensions of influencer efficacy that most effectively stimulate the brand fan effect, optimize influencer selection and collaboration, and develop communication strategies that strengthen fan engagement. These contributions together offer a robust theoretical and managerial foundation for advancing sustainable marketing practices in the era of social media.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influencer Efficacy

Efficacy refers to the comprehensive, long-term assessment of an entity’s functions and capabilities, rather than a short-term evaluation. Scholars such as Ryu and Han [21] describe influencer efficacy as the assessment of customers’ impressions of influencers, as shaped by activities and content; it involves the audience’s subjective evaluation and interpretation of the influencer. It is crucial for influencers to achieve efficacy, which emerges from the continuous publication of relevant content across online media. Once established, influencer efficacy directly impacts followers’ attitudes towards recommended products, subsequently influencing brand consumer behavior.

Scholars have studied the relationship among influencers, their followers, and the content they post, as well as the mechanism by which it affects the marketing effectiveness of influencers, through communication models. Results suggest that for effective influencer marketing, influencers need to retain fans and encourage them to keep following their recommendations [4]. Trivedi and Sama [22] compare the effects of celebrity and expert influencers on consumers’ online purchase intentions in regard to electronics products and find that the latter has clear advantages over the former. That study shows that consumers value the professional opinions and trustworthiness of expert influencers more than they are attracted to celebrity influencers simply by their looks or personal charm. Therefore, brands should pay more attention to the expertise and industry background of influencers when choosing partners [22].

There is no consensus on how to divide the dimensions of influencer efficacy. Ryu and Han [21] define it as a multidimensional concept, including authenticity, communication skills, expertise, and others. Hugh et al. [14] use the Theory of Information Source Characteristics to study the effects of influencers on followers from three aspects: influencer trustworthiness, similarity and professionalism. Other studies use the same theory but propose slightly different dimensions, as summarized in Table 1.

Signaling theory posits that in situations of high information asymmetry, consumers rely on externally observable signals to infer the true, unseen quality of a product. Green food has significant trustworthiness attributes. Its environmental protection, health and safety characteristics are difficult to verify through direct experience before or after purchase. Therefore, consumers rely more on quality signals from credible information sources when making purchasing decisions. In the digital social media environment, an influencer’s professionalism can be seen as a capability signal regarding product knowledge and judgment, while their trustworthiness constitutes a trust signal reflecting honesty and integrity. These signals can effectively reduce consumers’ uncertainty about the quality of green food, enhance their perceived quality, and thus promote their positive attitude towards the brand and their following behavior. At the same time, the similarity between influencers and consumers can also be seen as a signal of value alignment, making it easier for consumers to regard influencers as credible advocates of green consumption. Therefore, in the context of high information asymmetry of green food, the signals of capability, integrity, and value consistency sent by influencers constitute the core mechanism for exerting their influence.

Within the context of green food, we classify influencer efficacy into three dimensions of professionalism, trustworthiness and similarity, drawing on the Source Credibility Model, Homophily Theory and Signaling Theory. These theoretical perspectives suggest that consumers, particularly in product domains such as green food, where quality, safety and environmental attributes are not easily observable, are more likely to be persuaded by influencers perceived as experts, trustworthy and aligned with consumers’ values and lifestyles than by influencers whose influence rests mainly on physical attractiveness. Professionalism is reflected in the fact that influencers have a thorough understanding of key attributes such as the quality and freshness of green food, thereby being able to sort out brand-related information for consumers and assist them in more clearly judging and identifying different agricultural product brands [23,24]. Trustworthiness refers to the degree to which consumers trust and accept the information provided by influencers in communication [14,25]. Similarity is defined as the degree of alignment between an influencer and their audience in terms of preferences, value orientations, or beliefs [26].

Table 1.

Dimensions of Influencer Efficacy.

Table 1.

Dimensions of Influencer Efficacy.

| Source | Factors Driving Influencer Efficacy |

|---|---|

| Balabanis and Chatzopoulou [27] | trust, expertise, homophily, attractiveness, authority, approachability, and inspirational |

| Ki et al. [28] | inspiration, expertise, similarity, and enjoyability |

| Ryu and Han [21] | communication skills, expertise, influence, and authenticity |

| Wang and Chen [29] | credibility, attractiveness, professionalism, interactivity |

| Wiedmann and Von Mettenheim [30] | influencer attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise |

| Hugh et al. [14] | influencer professionalism, trustworthiness, similarity |

| Barta et al. [31] | originality, quality, quantity and humor |

| Han and Balabanis [13] | credibility, trustworthiness, expertise and authenticity |

| Lin et al. [23] | professionalism, product involvement, interactivity and popularity |

2.2. Perceived Quality

Perceived quality is a very important factor in green food marketing [32]. It mainly refers to the target audience’s feelings and perceptions of product quality, performance, and user experience. When a food is viewed as being of excellent quality, healthy, and associated with a good user experience, it tends to be better recognized and trusted, and thus chosen over other options. Mitra and Golder [33] hold that perceived quality reflects consumers’ subjective feelings and is distinguished from actual quality. This train of thought can be traced back to the research of Zeithaml [34], who conceptualized it as the subjective evaluation of the general advantage of products by customers rather than objective quality. Perceived quality is key for maintaining long-term customer relationships and influencing purchase intention [35,36,37]. Various studies use extended research models to assess the effects of perceived quality in the food marketing field. For example, Wang et al. [38] assess the degree of consumer confidence in certified food and incorporate perceived quality into the Theory of Planned Behavior to analyze consumers’ purchase intention for certified foods. Roh et al. [39] integrate Consumption Value Theory and Rational Behavior Theory to study organic food consumption. The results of such studies suggest that the perceived quality of green products has a significant impact on consumer attitudes, which in turn positively impacts purchase intention. Because perceived quality affects consumer attitudes and consumption behaviors toward brands, it may also affect their purchasing decisions as well as consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty.

Perceived quality reflects consumers’ comprehensive subjective judgment of a product’s health value, environmental attributes, and safety. Essentially, it’s an evaluative emotional response triggered by cognitive cues. When consumers develop trust and a sense of belonging due to the influencer’s expertise, these positive perceptions translate into a higher perception of product quality [12]. When consumers consistently believe a particular green food brand possesses high-quality characteristics, this positive emotion solidifies into a deeper sense of consistency, gradually forming a fan effect characterized by sustained attention, proactive sharing, and loyal purchasing. In other words, the brand fan effect is achieved through a layered transformation of “cognition-emotion-relationship.” Perceived quality, acting as a mediator, effectively internalizes the external informational influence of influencer traits into an emotional connection between consumers and the brand, thus forming a long-term, stable fan effect.

2.3. Brand Fan Effect

Brand fan effect refers to the deep attachment consumers develop to their favorite brands that goes beyond ordinary preference. It manifests as extreme love or even faith in the brand, exhibiting emotional and behavioral characteristics similar to religious worship [40]. Brand fan effect is mainly reflected in consumers’ emotional investment and behavior. Consumers exhibit strong emotional dependence or even faith in a brand, for example, regarding the brand as a part of their daily lives. Meanwhile, this sentiment is often externalized in actual behavior, such as exclusive brand preference, repurchasing behavior, and active support for the brand. These behaviors are all based on the premise of recommendation by influencers, reflecting subordinate behaviors triggered by fans’ emotional investment and identity identification with influencers, rather than a stable attitude towards the brand. Although these behaviors may superficially resemble brand loyalty, repurchase intention, or word-of-mouth intention, their underlying psychological motivations and mechanisms are fundamentally different. Brand fan effect is driven by consumers’ emotional identification and trust in influencers. It is the result of emotional-behavioral resonance, rather than a rational decision based solely on brand attributes or product satisfaction. In other words, brand fan effect manifests as a dependent behavior towards the influencer. Although the object of this behavior is the brand, the motivation and psychological mechanism stem from the recognition of the influencer. In the digital age, digital technology and social platforms provide more opportunities for interaction between fans and followers, making the relationship between fans and followers much broader and closer through media communication. In this interactive context, fans are no longer passive recipients but take a more active role. The viral transmission characteristics of digital media make it easier for fans to interact with them, causing strong radiation effects. Brands are increasingly realizing the potential of partnering with these influencers, who have cultivated a loyal fan base. In light of these developments, and in the context of this so-called fan economy, some scholars explore the prospects for celebrity endorsement and investigate how social media influencers reshape brand marketing strategies [41].

Many researchers note the link between brands and their fans. Brand fan groups are often seen as individuals who are deeply attached to and love a brand, purchase and consume its products, endorse the lifestyle promoted by it, and derive personal meaning from it. In the context of the digital environment, some scholars introduce the concept of the fan economy, referring to the unique consumption behaviours of fans directed towards products and content related to their idols. Brands can leverage the fan effect to innovate new marketing models [40,42]. Within the context of virtual communities and the fan economy, Yang and Shim [43] focus on the emotional investment and attachment relationships exhibited by fans in online interactions, pointing out that online interactions and quasi-social relationships are deeply embedded in digital fan practices, thereby enhancing fans’ willingness to make purchases to support their favorite social media influencers. Furthermore, Kim and Kim [44], starting from the emotional dimension of the fan effect, construct a model to analyze how quasi-social interactions between fans and influencers improve fans’ quality of life and happiness, exploring how influencers make fans happy. Moreover, Xu et al. [40] explored the pathways and influencing factors of the realization of the fan effect in the new media environment. The results show that brand experience is a prerequisite for the brand fan effect, while brand identification is the most crucial factor in its realization. In the process of brand marketing, the brand fan effect should be fully developed and utilized. This requires brands to pay more attention to consumer brand experience, cultivate consumer brand identification, and shape a positive brand image.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Influencer Efficacy and Brand Fan Effect

As described above, influencer efficacy stems from the characteristics of the influencer and impacts consumer behavior and the audience’s relationship with the brand [45]. A study on consumer willingness to buy brands online shows that factors influencing purchases include vision, interaction, similarity, and entertainment, among others. Connelly et al. [46] apply Signal Theory and the Source Credibility Model and report that influencer reliability, similarity and professionalism all promote a positive brand attitude and purchase intention, consistent with the conclusions of Hugh et al. [14]. In the present study, we conduct an empirical analysis to explore how the personality characteristics of influencers affect brand attitudes and whether this can lead to the purchase of certain products or services. The reliability, professionalism, attractiveness, and interactivity of influencers can evoke strong emotional connections with consumers and thus spark interest in the brands being recommended. Influencers, as key information sources in online purchasing channels, impact purchasing behavior and the development of brand intimacy.

In summary, the literature suggests that factors such as influencer trustworthiness, similarity and professionalism affect purchasing behavior and their relationship with brands. When audiences read product recommendations from influencers, they consider these factors and form impressions of the influencers. Consequently, consumers evaluate influencers based on their trustworthiness, similarity and professionalism, which in turn fosters brand loyalty and becomes fans of the brand. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.

The professionalism of influencers has a positive impact on the brand fan effect.

H2.

The trustworthiness of influencers has a positive impact on the brand fan effect.

H3.

The similarity between influencers and followers has a positive impact on the formation of the brand fan effect.

3.2. Influencer Efficacy and Perceived Quality

Recently, the consumption of certified foods has drawn growing interest from the academic community [38]. In the process of purchasing branded products, perceived quality is one of the most important factors to consider. As detailed above, perceived quality in influencer marketing refers to consumers’ evaluations of products and services [30]. As key players in social media, influencers hold significant sway over their audiences. They interact and communicate with consumers, introducing the brand’s story and product functions and characteristics, thereby deepening consumers’ understanding of products and improving perceived quality [47]. This influencer-based interaction not only showcases the various features and experiences of the product but also conveys the language and philosophy of the brand, driving purchases.

In sum, consumer recognition of influencer professionalism, similarity and trustworthiness may affect consumer evaluation of branded products [14]. Considering this, and the fact that perceived quality reflects the comprehensive evaluations of consumers [27,48], in an online purchasing environment, the higher the perceived quality of a good recommended by an influencer, the more satisfied a consumer will be with that good (and the influencer), creating a positive reinforcing effect. Conversely, if the perceived quality is low, consumers will be dissatisfied with both the product and the influencer marketing it and will not buy the item being marketed [48].

Based on these findings, this paper argues that the degrees of influencer professionalism, trustworthiness, and similarity influence the consumer’s perceived quality of brand products. We propose the following hypotheses:

H4.

Influencer professionalism positively impacts perceived quality.

H5.

Influencer trustworthiness positively impacts perceived quality.

H6.

The similarity between influencers and followers positively impacts perceived quality.

3.3. Perceived Quality and the Brand Fan Effect

As already established, the perceived quality of a product significantly affects consumers’ online purchase intention and brand loyalty. In short, as influencers successfully promote products with high perceived quality, consumers become fans of the brand. Indeed, this is reported across various contexts, including users of e-commerce platforms [27], Instagram users’ purchasing of branded clothing [49], and shopping behavior in fashion stores [50]. Chi and Chen [51] find that perceived quality promotes customer identification with products.

Therefore, online sales platforms and brands should focus on improving customers’ perception of product quality. Regarding green food promotion, the better the perceived quality of a green food recommended by influencers, the more likely consumers are to agree with that influencer’s recommendation, thus forming a fan effect around that product. We propose the following hypothesis:

H7.

Perceived quality has a positive impact on the brand fan effect.

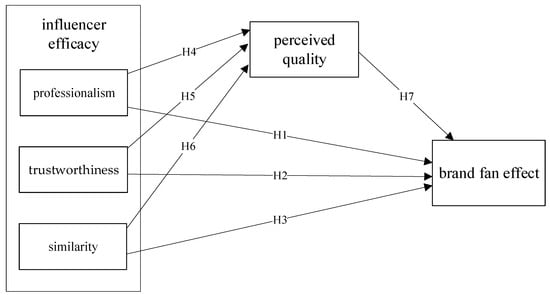

Taking all of these factors into consideration, we propose an empirical model on the relationship between influencer efficacy, perceived quality, and brand fan effect. We root it in established concepts such as the Source Credibility Model, Homophily Theory and Signaling Theory, taking influencer efficacy as the independent variable, perceived quality as the mediator variable, and brand fan effect as the dependent variable (as shown in Figure 1). We study the relationship between influencer efficacy, including each of its different dimensions, and brand fan effect.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

4. Research Methods

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Collection

We used a popular Chinese professional survey website, Wenjuanxing (www.sojump.com (accessed on 7 May 2023), an equivalent to Survey Monkey), for data collection. The survey was distributed through open links. Three screening questions were used at the beginning of the survey to ensure that respondents matched the target population. First, participants were asked whether they followed any influencers on social media. Second, they were asked whether the influencers they followed engaged in green food marketing activities, such as product recommendations or livestream selling. Third, participants were asked whether they had previously purchased green food as a result of an influencer’s recommendation. Only respondents who met all screening conditions were allowed to proceed to the full questionnaire. The questionnaire translation employed a “translation-reverse translation” process: one bilingual researcher translated the English items into Chinese, and another independent bilingual researcher then translated them back into English. The research team compared the original and translated versions and optimized the item wording accordingly to improve accuracy and comprehensibility. A pre-survey was conducted before the formal survey. The pre-survey participants were faculty and students from a comprehensive university in China. After completing the questionnaire, they provided feedback on the clarity, appropriateness, and difficulty of understanding the items. Based on this feedback, we revised some items that were not clearly worded or potentially ambiguous. A set of statements about attitudes is devised for each variable (influencer efficacy, perceived quality, and brand fan effect), and subjects are asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with each statement (where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree). All the items were measured on a five-point Likert scale. To ensure the authenticity and validity of the questionnaire, the survey is conducted anonymously, and the privacy of the respondents is respected as much as possible. After two rounds of distribution, 417 valid questionnaires were successfully collected. A detailed list of demographic information is shown in Table A1. Among the respondents, 54.9% were female, and 45.1% were male consumers. The majority of the respondents have a bachelor’s degree, and 15.6% hold a master’s degree or higher. In terms of occupational distribution, 36% were students, 10.1% were government or public institution personnel, 20.1% were employees, 20.9% were self-employed, and other occupations accounted for 12.9%. In terms of age, young people account for a large proportion of the sample, with those under 35 years old accounting for 64.7%.

4.2. Measurement of Variables

We measure influencer efficacy (influencer professionalism, similarity and trustworthiness), product perceived quality, and brand fan effect. To improve the reliability and validity of the measurement scale, we adopt the Influencer Efficacy Scale, a mature, widely used scale derived from Hugh et al. [14] that is modified to include 12 items covering our three variables. The measurement items for perceived quality are based on Yoo et al. [52] and consist of four questions. The measurement items for brand fan effect are taken from Xu et al. [40] and also consist of four questions. All questions use a 5-point Likert scale.

4.3. Reliability and Validity Test

AMOS24.0 software was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis on the 417 questionnaires collected, and SPSS22.0 software was used to calculate the Cronbach’s α of each variable. The Cronbach’s coefficients were 0.864, 0.919, and 0.909 for professionalism, trustworthiness, and similarity, respectively, for the influencer efficacy dimension; 0.867 for perceived quality; and 0.897 for the brand fan effect. The reliability of all scales was greater than 0.8, so the questionnaire had high reliability. All latent constructs in this study were specified as reflective measurement models. The reflective specification was theoretically justified because the items represented manifestations of the underlying latent construct. The measurement and structural models were estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS. Data normality was examined through skewness and kurtosis, and the skewness values ranged from −0.738 to −0.333, and kurtosis values ranged from −0.512 to 0.159, all of which fell well within the commonly accepted thresholds [53]. Confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model showed that the model had a good fit (Table 2). The reliability of the variables was shown in Table 3. The α value of each variable ranged from 0.864 to 0.919, and the CR values ranged from 0.864 to 0.919, all of which were above 0.800, indicating that the scale adopted in this study had good internal consistency. At the same time, the average variance extracted (AVE) and load of each index factor were above 0.500, indicating that the convergence validity of the scale also meets the requirements. The correlation analysis results of the scale were shown in Table 4. The AVE square root of each variable was greater than the correlation coefficient between this variable and other variables. To further enhance discriminant validity, the results of the HTMT index were added. As shown in Table 5, the HTMT values among all latent variables were significantly lower than the strict threshold of 0.85 and far below the lenient standard of 0.90 [54], indicating that the discrimination validity of the scale also reached an acceptable level.

Table 2.

Fitting Index Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Mediator Variables.

Table 3.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table 4.

Results of Correlation Analysis.

Table 5.

HTMT Analysis.

4.4. Common Method Bias

To examine for common method bias that may arise from self-reported questionnaire data, this study employed a Harman one-way factorial test. Specifically, all measurement items were included in an exploratory factor analysis without rotation to observe whether a single factor dominated the explanatory power. The results showed that the first factor explained 47.56% of the total variance, which was below the commonly used 50% threshold for identifying substantial common method bias. Therefore, it could be concluded that the data in this study were not significantly affected by common method bias [55].

4.5. Model Hypothesis Testing

To test the effect of each of the three dimensions of influencer efficacy on perceived quality and the formation of the brand fan effect, AMOS24.0 software was used to evaluate the structural model. Analysis revealed that the overall fitting index of the model was relatively good. x2/df = 1.753, which meets the commonly recommended standard of less than 3. GFI = 0.937, NFI = 0.953, TLI = 0.975, CFI = 0.979, all greater than the standard of 0.900; We provided the 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA, which was estimated at 0.043 (90% CI: 0.034–0.051), indicating a good model fit. Additionally, the SRMR value of 0.032 provided further evidence of satisfactory model fit. Next, the hypotheses were examined, with the outcomes summarized in Table 6. The table below presented professionalism (β = 0.256, p < 0.001), trustworthiness (β = 0.112, p = 0.013), and similarity (β = 0.355, p < 0.001) had a positive influence on brand fan effect; Professionalism (β = 0.166, p = 0.011), trustworthiness (β = 0.291, p < 0.001), and similarity (β = 0.267, p < 0.001) had positive effects on perceived quality. In addition, perceived quality (β = 0.333, p < 0.001) was significantly and positively correlated with brand fan effect. Therefore, all hypotheses were supported.

Table 6.

Standardized Regression Estimates and Significance of Structural Equation Models.

The model explained 37.3% of the variance in perceived quality (R2 = 0.373) and 74.1% of the variance in brand fan effect (R2 = 0.741). Based on Cohen’s [56] effect size criteria, the influencing factors and their strengths on brand fan effect and perceived quality were analyzed as follows: Regarding brand fan effect, professionalism (f2 = 0.066), similarity (f2 = 0.126), and perceived quality (f2 = 0.111) all exhibited medium effects, with similarity having the most prominent driving effect. Professionalism and perceived quality contributed similarly, while trustworthiness (f2 = 0.013) showed only a small effect, indicating that emotional resonance and perceived actual value were the core elements for cultivating brand fans, and the direct impact of trustworthiness was relatively limited. Regarding perceived quality, trustworthiness (f2 = 0.085) and similarity (f2 = 0.071) exhibited medium effects, with trustworthiness having a slightly higher impact than similarity. Professionalism (f2 = 0.028) showed a small-to-medium effect, indicating that consumers’ perception of brand quality mainly relied on trust and a sense of personal fit, while the supporting role of professionalism was relatively weak.

To examine whether demographic characteristics had a systematic impact on the research model, we conducted a multi-group structural invariance test. Specifically, in the gender group (male vs. female), the comparison between the Unconstrained model and the Structural Weights model yielded ΔCMIN = 28.782 and Δdf = 22, with a significance level of p = 0.151 calculated using the CHIDIST function in Excel; in the student vs. non-student group, ΔCMIN = 24.759 and ΔDF = 22, p = 0.309; and in the age group (≤35 years vs. >36 years), ΔCMIN = 13.462 and ΔDF = 22, p = 0.919, none of which reached a significant level (p > 0.05). The results indicated that there were no significant differences in the structural paths between groups, regardless of whether the groups were divided by gender, student status, or age. Therefore, the model structure of this study was robust across groups, and the research conclusions were not affected by the systematic bias of the sample’s demographic characteristics.

4.6. Testing of Mediating Effects

Finally, we used the bootstrap method in AMOS software to verify the mediating role of perceived quality. The number of samples was set to 5000, and the confidence interval was set to 90%. When the interval [BootLLCI, BootULCI] did not contain 0, an indirect effect existed; that is, a mediator effect was established. The results were shown as follows.

Professionalism → brand fan effect: Indirect effect b = 0.092, 90% CI [0.048, 0.157], direct effect b = 0.368, 90% CI [0.248, 0.482], total effect b = 0.460, 90% CI [0.350, 0.571];

Trustworthiness → brand fan effect: Indirect effect b = 0.093, 90% CI [0.054, 0.150], direct effect b = 0.107, 90% CI [0.018, 0.195], total effect b = 0.200, 90% CI [0.112, 0.293];

Similarity → brand fan effect: Indirect effect b = 0.063, 90% CI [0.020, 0.122], direct effect b = 0.291, 90% CI [0.184, 0.414], total effect b = 0.354, 90% CI [0.236, 0.490].

In all cases, the confidence intervals for the bias-corrected method did not contain 0, indicating that a mediator effect existed. For completeness, we fitted a full mediation model (with the direct path from the three dimensions to the brand fan effect fixed at 0) and compared it with the baseline partial mediation model using Δχ2. The results showed that Δχ2(3) = 166.16, p < 0.001, indicating that removing the direct path significantly reduced the model fit, further supporting the partial mediating role of perceived quality.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Research Conclusions

We develop and test an empirical model of the relationship between influencer efficacy (professionalism, trustworthiness, and similarity), perceived quality, and brand fan effect. It is rooted in the Source Credibility Model, Homophily Theory and Signaling Theory. We find that professionalism, trustworthiness, and similarity positively facilitate the formation of the fan effect in the context of green food brands, leading to the acceptance of hypotheses, H1, H2, and H3. From the perspective of consumers, they value professional knowledge, excellent skills, and authority in influencers. This supports the view that professionalism influences fan behavior [57]. Second, trustworthiness has a relatively weak direct impact on the brand fan effect, which means it has a weaker influence when it comes to deeper psychological mechanisms such as emotional attachment and fan-oriented supportive tendency. Further research revealed that trustworthiness has a significant and relatively stronger positive impact on perceived quality. This finding suggests that trustworthiness primarily affects the audience’s cognitive evaluation mechanism, meaning it more directly enhances consumers’ quality judgment of the subject. Based on this, we believe that trustworthiness is not the main driving force behind the brand fan effect, but rather that it exerts an indirect influence by improving perceived quality. Finally, similarity not only establishes cognitive connections between the influencer and followers but also creates connections at an emotional level. That is, fans are more likely to empathize with influencers, and this resonance promotes consumer acceptance of influencer recommendations, resulting in fan-like behavioral responses.

We further confirm that professionalism, trustworthiness, and similarity can promote the perceived quality of consumers, leading to the acceptance of hypotheses, H4, H5, and H6. Specifically, professionalism enhances influencers’ authority in product knowledge, risk identification, and judgment, thereby increasing consumer trust in product performance and efficacy. Trustworthiness strengthens consumers’ perception of the authenticity and impartiality of recommendations, reducing concerns about commercial motives or exaggerated claims. Similarity fosters value resonance and emotional closeness, lowering consumers’ defensiveness towards influencers’ intentions and making them more willing to accept influencers’ evaluations of product quality. These three qualities work together to enable consumers to form more stable, comprehensive, and positive quality judgments when encountering information about green food.

In addition, perceived quality has been shown to significantly promote the brand fan effect, leading to the acceptance of Hypothesis 7. This result is consistent with the view that high perceived quality can strengthen the relationship between consumers and brands [58]. In the category of green food, which is highly value-oriented and has a high degree of information asymmetry, perceived quality not only affects consumers’ evaluation of product functionality but also becomes a key clue for them to judge the reliability and value fit of the brand. When consumers perceive that green food performs well in terms of health, environmental protection and safety, the cognitive confirmation and emotional satisfaction brought about by product quality will enhance their positive attitude towards the brand, thereby increasing their positive behavioral tendencies such as continuous attention, active support and spontaneous dissemination, thus promoting the formation and strengthening of the brand fan effect. In other words, high perceived quality, by satisfying consumers’ value expectations and risk assessment needs, makes them more willing to generate typical fan behaviors such as continuous purchase, word-of-mouth sharing and even brand defense, becoming an important mechanism for green food brands to cultivate the fan effect.

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

Firstly, this study introduces the Source Credibility Model, Homophily Theory and Signaling Theory into the research framework of influencer efficacy on brand fan effect, expanding the application boundaries of these two theories in the field of green food brand marketing. Traditional studies often regard information sources and credibility as linear factors influencing audience attitudes, while this study deepens their explanatory power in value-oriented categories by using influencer professionalism, trustworthiness, and similarity as core dimensions. Simultaneously, based on Homophily Theory, this study reveals how the similarity between consumers and influencers in values, lifestyles, and environmental awareness further amplifies the impact on the brand fan effect. By integrating these two theories, this study clarifies how influencer efficacy is internalized into sustained fan support for green food brands through perceived quality, thus enriching the theoretical depth of the brand fan effect’s influencing mechanism.

Unlike existing literature that often emphasizes traditional persuasive cues such as professionalism and attractiveness, this study compares the relative effects of traits and finds that similarity has the most significant direct impact on the brand fan effect, higher than professionalism and trustworthiness. This result provides new discriminative evidence for influencer efficacy, revealing that in the value-sensitive context of green food, viewers rely more on value consistency and lifestyle resonance than on traditional professional or credibility cues to judge the persuasiveness of information sources. Green food naturally carries moral values such as health, environmental protection, and sustainability, making consumers more inclined to trust influencers whose beliefs align with their own, and viewing similarity as a key signal of genuine motives and consistency in stance. Therefore, this study not only supplements the theoretical discussion of the relative contribution of influencer efficacy but also expands the applicability of Homophily Theory in value-oriented consumption scenarios.

What’s more, this study reveals the mediating role of perceived quality between influencer efficacy and brand fan effect, further deepening the theoretical understanding of the formation mechanism of the fan effect in green food brands. As one of the core psychological evaluation dimensions for consumers in the brand evaluation process, perceived quality not only reflects consumers’ comprehensive judgment of product performance and overall value but also plays an indispensable precondition in the generation of brand fan effect. This study, through systematic empirical evidence, reveals how influencer efficacy not only directly shapes the brand fan effect, but also indirectly promotes sustained fan behavior by enhancing consumers’ perception of the quality of green food. This finding not only enriches the theoretical landscape of influencer marketing but also echoes the theoretical calls from Wang [38] to further clarify how influencer traits play a role in more complex psychological mechanisms, providing a more explanatory theoretical path for understanding the formation of the brand fan effect in the green food category.

5.2.2. Practical Implications

Research findings show that the professionalism, trustworthiness, and similarity of influencers significantly impact the brand fan effect of green food brands. Therefore, brands not only need to select influencers whose audience profiles align with the age structure, lifestyle, health awareness, and environmental attitudes of their target consumers, but also need to construct a sustainable influencer collaboration strategy framework grounded in audience attributes. This framework should create a tiered combination of influencers, including professional and authoritative influencers and those who resonate with the consumer’s lifestyle, to ensure credibility, identification, and sustained reach. By building a sustainable collaboration mechanism that involves jointly developing green communication guidelines, establishing performance indicators such as content quality indices and audience trust levels, and implementing long-term collaboration and periodic evaluation processes, the partnership between brands and influencers can shift from one-off campaigns to sustainable strategic collaboration. This framework enables companies to not only accurately match their target audience but also steadily enhance green awareness and quality perception in long-term relationships, thereby strengthening the controllability and sustainability of the fan effect for green food brands.

Secondly, companies should conduct systematic cost-benefit analyses when formulating fan effect strategies. By comparing the differences in reach costs, unit content output value, fan stickiness, conversion efficiency, and long-term brand building among different types of influencers (such as professional, lifestyle, and micro-influencers), a quantitative evaluation model integrating input, impact, and accumulation can be developed to support more rational budget allocation. For example, while professional influencers are more expensive, they offer more significant returns in enhancing consumers’ professional awareness and quality perception of green food; micro-influencers are less expensive and have higher trust levels but require quantity and management coordination; lifestyle influencers can effectively enhance the sense of identification and sharing brought about by similarity. By combining cost-benefit analyses of product subcategory information strategies with fan strategies, brands can achieve more scientific resource allocation, enabling influencer collaborations to produce more targeted, verifiable, and efficient practical results in the green food market.

Third, to further amplify the positive impact of professionalism and trustworthiness, brands need to collaborate with influencers to develop content formats that enhance processing transparency and origin traceability, such as short videos showcasing the origin, transparent production process vlogs, testing and comparison content, and third-party quality verification demonstrations. These content formats should highlight key production scenarios such as daily farm operations, agricultural technology applications, and planting methods to build a more complete chain of evidence. This allows consumers to intuitively understand the brand’s genuine investment in quality control and green production and clearly see the entire process of green food value formation. Through the visual presentation of production details, brands can not only strengthen the authenticity and professionalism of green food but also effectively reduce consumers’ doubts about green advertising, thereby further enhancing their overall perception of product quality.

Fourth, green food brands should pay special attention to brand safety and the risk of greenwashing when using influencers for communication. When influencers’ words and actions are inconsistent with brand values or their content lacks transparency, fans are prone to perceiving it as perfunctory marketing, leading to a collapse of trust. Therefore, companies need to establish systematic review and risk control mechanisms, including compliance reviews of influencers’ values and past content, requiring all green information dissemination to be supported by verifiable evidence, continuously monitoring the consistency between influencers’ published content and the brand’s green propositions, establishing a sound crisis communication process, and maintaining caution in all communication to avoid exaggerating environmental effects or overemphasizing sensitive statements such as additive-free. By combining influencer selection criteria with brand safety management, brands can improve the controllability of their communication influence, reduce potential trust risks, and ensure that the digital communication of green food always remains on a sustainable, trustworthy, and low-risk track.

5.3. Limitations and Future Prospects

There are also some limitations to this study that can be addressed in future research. First, the conclusions of this study are primarily based on user samples from Chinese social media platforms, and contextual characteristics may limit their external generalization to other countries’ platforms and cultures. Furthermore, while the study uses cross-sectional data, which can reveal associations, it cannot identify causal relationships. Future research could further validate these findings through longitudinal studies or experimental designs. Second, we limited our analyses to three dimensions of influencer efficacy (trustworthiness, similarity and professionalism). The potential effects of other factors and their roles in inducing the brand fan effect can be explored in future work. Third, the structural model of this study does not incorporate core green consumption variables such as environmental consciousness, ethical consumption, greenwashing perception, or risk perception. Future research can integrate these constructs to better capture the role of sustainability-related values in shaping fan-oriented supportive tendencies. Finally, we only consider the mediating variable of perceived quality. More mediating variables (such as brand attachment, etc.) can be considered in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and S.Z.; methodology, Y.Y. and C.H.; software, Y.Y. and S.Z.; validation, Y.Y. and C.H.; formal analysis, Y.Y. and S.Z.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, C.H.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y., S.Z. and C.H.; supervision, C.H.; project administration, Y.Y. and C.H.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 2022 Harbin University of Commerce Teacher Innovation Support Program Project [22GLC283]. China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as according to the research ethics policy of Harbin University of Commerce, this type of study does not require formal ethics approval by Harbin University of Commerce.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are available from the corresponding author without undue restriction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 417).

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 417).

| Factor | Category | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 188 | 45.1% |

| Female | 229 | 54.9% | |

| Age | Under 22 years old | 142 | 34.0% |

| 23–35 years old | 128 | 30.7% | |

| 36–44 years old | 97 | 23.3% | |

| 45–60 years old | 37 | 8.9% | |

| Over 60 years old | 13 | 3.1% | |

| Education | Junior high school and below | 32 | 7.7% |

| High school, technical secondary school | 57 | 13.7% | |

| Junior College | 81 | 19.4% | |

| Undergraduate | 182 | 43.6% | |

| Postgraduate and above | 65 | 15.6% | |

| Monthly income | 3000 yuan and below | 160 | 38.4% |

| 3001–6000 yuan | 131 | 31.4% | |

| 6001–9000 yuan | 97 | 23.3% | |

| 9001 yuan and above | 29 | 6.9% |

Table A2.

Measurement items.

Table A2.

Measurement items.

| Variable | Items |

|---|---|

| professionalism | I consider [influencer] to be an expert on [field of expertise] |

| I consider [influencer] to be sufficiently experienced in [field of expertise] | |

| I consider [influencer] to have a lot of knowledge about [field of expertise] products | |

| I consider [influencer] to be competent in making assertions about [field of expertise] products | |

| trustworthiness | I feel [influencer] is dependable |

| I feel [influencer] is honest | |

| I feel [influencer] is sincere | |

| I feel [influencer] is trustworthy | |

| similarity | [influencer] and I have a lot in common |

| [influencer] and I are a lot alike | |

| [influencer] and I easily identify with each other | |

| [influencer] resonates with me. | |

| perceived quality | Be able to fully understand the cost performance of the product |

| Fully understand the social attributes of the product | |

| Be able to accept the burden of purchasing this product | |

| The first impression of the product and its introduction was good | |

| brand fan effect | Because the influencer’s recommendations for this brand have become part of my daily life |

| Because of the influencer’s recommendation, I will give priority to this brand | |

| Because the influencer’s recommendation motivates me to repurchase this brand’s products. | |

| Because the influencer’s recommendation leads me to use and update this brand’s products. |

References

- George, A.; Shibu, M.; Joseph, E.T.; Sunny, P. Impact of social media influencer marketing on customer purchase intention in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review. Front. Commun. 2025, 10, 1676901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V.C.; Wang, S.; Keating, B.W.; Chen, E.Y. Increasing social media stickiness through parasocial interaction and influencer source credibility. Australas. Mark. J. 2025, 33, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, B. The power of interaction: Fan growth in livestreaming E-Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfat, M.; Kirkham, R. It’s more delicious because I like you: Commercial food influencers’ follower satisfaction, retention and repurchase intention. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, W. Live commerce retailing with online influencers: Two business models. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 255, 108715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ishfaq, M.; Zhong, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, X. Green food development in China: Experiences and challenges. Agriculture 2020, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining Chinese consumers’ green food purchase intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic: An extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2021, 10, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shan, B. The influence mechanism of green advertising on consumers’ purchase intention for organic foods: The mediating roles of green perceived value and green trust. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1515792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, R.; Hobbs, J.E. Consumer confidence in credence attributes: The role of brand trust. Food Policy 2015, 52, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrobback, P.; Zhang, A.; Loechel, B.; Ricketts, K.; Ingham, A. Food credence attributes: A conceptual framework of supply chain stakeholders, their motives, and mechanisms to address information asymmetry. Foods 2023, 12, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenovic, M.; van Trijp, H.; Piqueras-Fiszman, B. (Un) believably green: The role of information credibility in green food product communications. Environ. Commun. 2024, 18, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Phua, J. Effects of eco-labels and perceived influencer expertise on perceived healthfulness, perceived product quality, and behavioral intention. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2024, 45, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Balabanis, G. Meta—Analysis of social media influencer impact: Key antecedents and theoretical foundations. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 394–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh, D.C.; Dolan, R.; Harrigan, P.; Gray, H. Influencer marketing effectiveness: The mechanisms that matter. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 3485–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.D.; Donavan, D.T.; Deitz, G.D.; Bauer, B.C.; Lala, V. A customer-focused approach to improve celebrity endorser effectiveness. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbaere, M.; Michael, B.; Phillips, B.J. Social media influencers: A route to brand engagement for their followers. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Daly, T.M.; Coussement, K.; Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.N.; Evers, U. Identifying influencers on social media. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinikainen, H.; Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Luoma-Aho, V. ‘You really are a great big sister’—Parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L.; Kuźniar, W. Green purchase behaviour gap: The effect of past behaviour on green food product purchase intentions among individual consumers. Foods 2023, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Cui, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhou, Y. Study on consumers’ motivation to buy green food based on meta-analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1405787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, E.A.; Han, E. Social media influencer’s reputation: Developing and validating a multidimensional scale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J.; Sama, R. The effect of influencer marketing on consumers’ brand admiration and online purchase intentions: An emerging market perspective. J. Internet Commer. 2020, 19, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Cai, Y.; Su, Y.; Lin, Q.; Lai, Q. Influence of key opinion leader on the brand advocacy of agricultural product: Taking Taobao live streaming as an example. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 9390–9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.H.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, L.Y. A literature review of brand evangelism. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2016, 38, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Muqaddam, A.; Ryu, E. Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G.; Chatzopoulou, E. Under the influence of a blogger: The role of information—Seeking goals and issue involvement. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.-W.C.; Cuevas, L.M.; Chong, S.M.; Lim, H. Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, W. The influence of opinion leader characteristics on consumers’ purchase intention in a mobile E-commerce webcast context. WHICEB 2022 Proc. 2022, 12, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.-P.; Von Mettenheim, W. Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise–social influencers’ winning formula? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Belanche, D.; Fernández, A.; Flavián, M. Influencer marketing on TikTok: The effectiveness of humor and followers’ hedonic experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Towards green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Golder, P.N. How does objective quality affect perceived quality? Short-term effects, long-term effects, and asymmetries. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucks, M.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Naylor, G. Price and brand name as indicators of quality dimensions for consumer durables. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraneševic, T.; Stančec, R. The effect of the brand on perceived quality of food products. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoj, B.; Pisnik Korda, A.; Mumel, D. The relationships among perceived quality, perceived risk and perceived product value. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2004, 13, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, J.; Chu, M. Behind the label: Chinese consumers’ trust in food certification and the effect of perceived quality on purchase intention. Food Control 2020, 108, 106825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.L.; Meng, R.; Xu, J.Z. Research on the formation of brand fan effect in new media environment. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2021, 30, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K. A study on the correlation and interaction between celebrity effect and fan economy. Star 2024, 27, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. The case study of marketing strategies by fan economy. Organization 2022, 34, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Shim, K. Antecedents of microblogging users’ purchase intention toward celebrities’ merchandise: Perspectives of virtual community and fan economy. J. Psychol. Res. 2020, 2, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. How does a celebrity make fans happy? Interaction between celebrities and fans in the social media context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; Dinh, T.D.; Ewe, S.Y. The more followers the better? The impact of food influencers on consumer behaviour in the social media context. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 4018–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, S.; Webster, J. Perceived greenwashing: The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Galliers, R.D.; Shin, N.; Ryoo, J.-H.; Kim, J. Factors influencing Internet shopping value and customer repurchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, S. Moderating effects of time pressure on the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention in social E-commerce sales promotion: Considering the impact of product involvement. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apiraksattayakul, C.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E. Shopping via Instagram: The influence of perceptions of value, benefits and risks on purchase intentions. Int. J. Online Mark. 2017, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Chen, Y. A study of lifestyle fashion retailing in China. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lee, S. An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.-H.; Chen, C.-F.; Tai, Y.-W. Exploring the roles of vlogger characteristics and video attributes on followers’ value perceptions and behavioral intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Shoukat, M.H.; Jamal, W.; Shakil Ahmad, M. What drives followers-influencer intention in influencer marketing? The perspectives of emotional attachment and quality of information. Sage Open 2023, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).