Liquorice Cultivation Potential in Spain: A GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Weeds: Can be composted or used as mulch.

- Leaves: Rich in nutrients and bioactive compounds; can be repurposed as soil amendments, used in animal feed, or valorised for cosmetic and medicinal applications.

- Stems: Often discarded, yet nutritionally dense and potentially rich in bioactive substances; can be processed for biomass energy, used as mulching material, or explored for fibre production.

- ○

- Flavouring agent: Used in sweets, candies, chewing gum, and beverages.

- ○

- Natural sweetener: Glycyrrhizin serves as a low-calorie sugar alternative.

- ○

- Herbal teas and alcoholic beverages: Commonly included in specialty drinks and herbal infusions.

- ○

- Digestive health: Helps treat acid reflux, stomach ulcers, and gastrointestinal discomfort.

- ○

- Respiratory support: Found in syrups and lozenges for sore throats and cough relief.

- ○

- Anti-Inflammatory and immune boost: Used in chronic inflammatory conditions and immune support formulations.

- ○

- Adrenal and stress regulation: Helps manage cortisol levels and adrenal function.

- ○

- Skin brightening and anti-inflammatory: Commonly used in creams and serums to reduce hyperpigmentation.

- ○

- Anti-aging and antioxidant protection: Helps protect the skin from environmental damage.

- ○

- Natural pesticide: Acts as a mild insect repellent in organic farming.

- ○

- Soil remediation: Assists in reducing heavy metal concentrations in polluted soils.

- ○

- Traditional medicine: Integral to chinese, ayurvedic, and middle eastern herbal treatments.

- ○

- Tobacco industry: Used to enhance the flavour and smoothness of tobacco products.

- Increased consumer preference for natural ingredients—As consumption trends shift towards organic and naturally derived products, liquorice extract is gaining popularity in various formulations.

- Expanding applications—Beyond traditional medicinal uses, liquorice extract is increasingly used in functional foods, dietary supplements, and natural cosmetics.

- To identify the agro-environmental factors that determine the suitability of Glycyrrhiza glabra cultivation in Spain;

- To develop a GIS-based multi-criteria assessment that integrates climatic, edaphic, hydrological, and socioeconomic variables at municipal scale; and

- To classify and map priority areas for potential liquorice expansion, highlighting zones where cultivation may contribute simultaneously to sustainable agriculture and rural development.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection and Layer Preparation

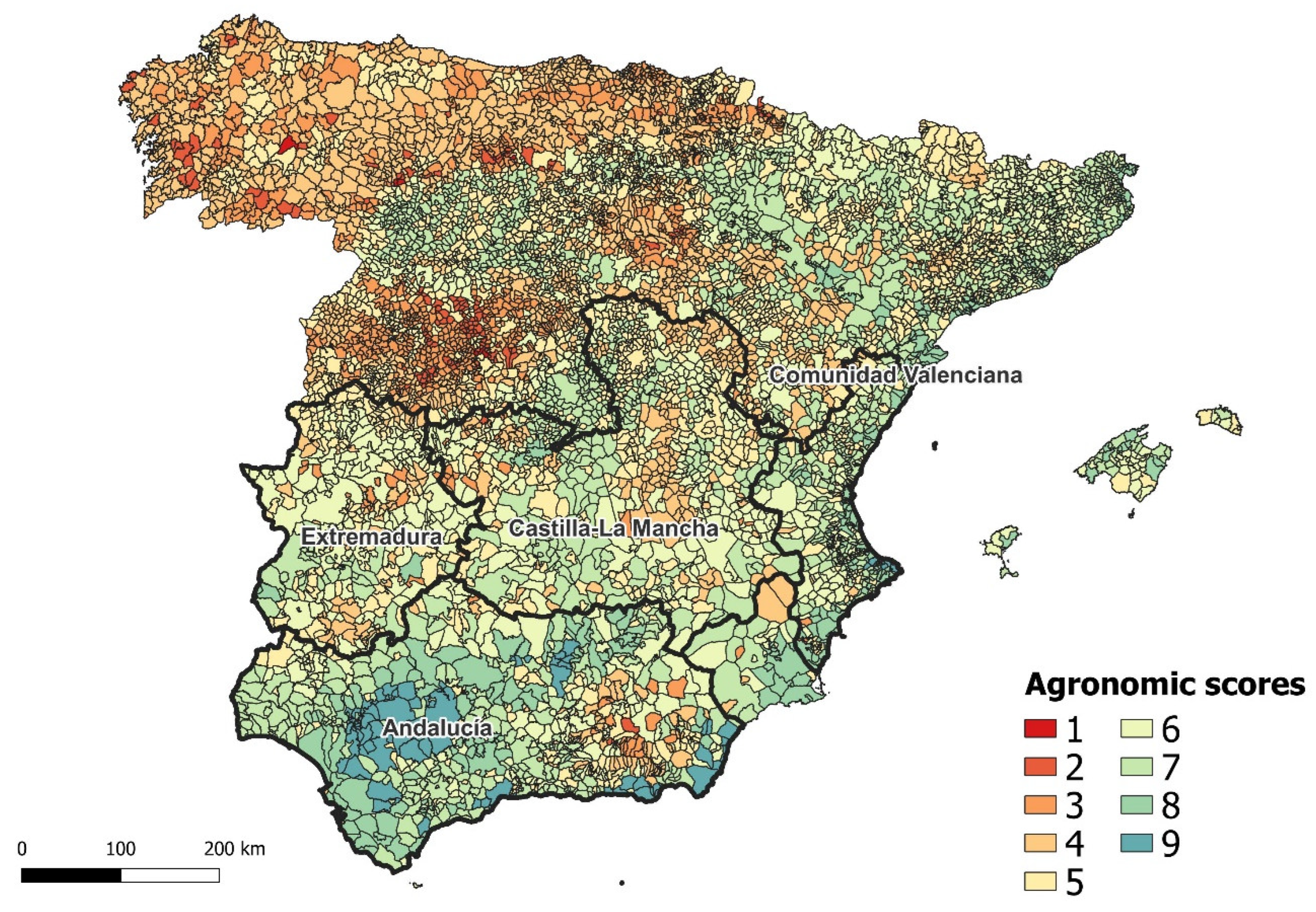

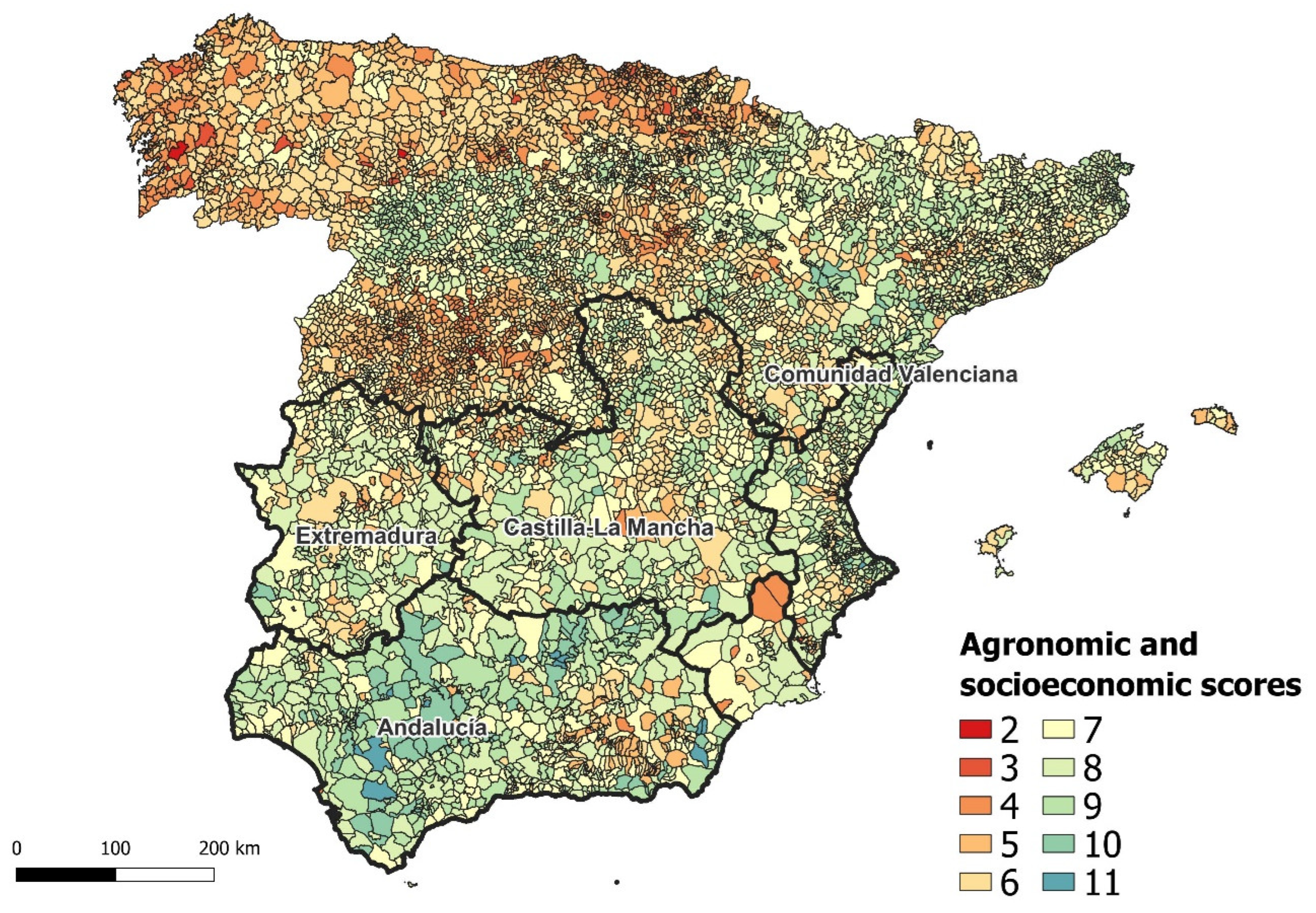

2.2. Suitability Analysis Through Spatial Overlay

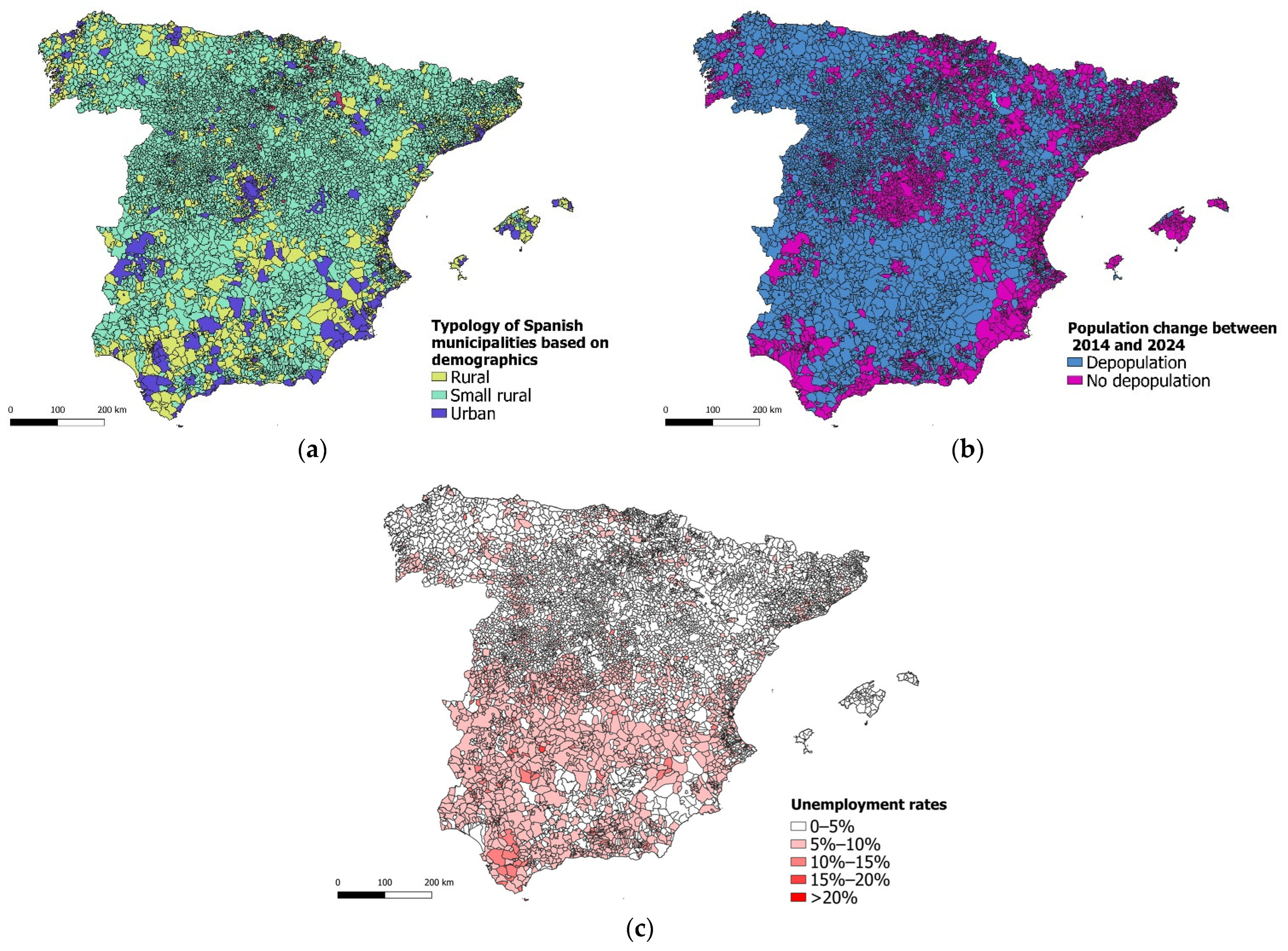

- Depopulation trend: municipalities showing a sustained negative demographic balance during most of the 2014–2024 period, according to official INE records [36].

- Rural classification: municipalities classified as rural or semi-rural (i.e., under 50,000 inhabitants).

- Unemployment rate: municipalities with an unemployment rate above the national average.

- Socioeconomic indicators were operationalised as binary variables by design. This approach ensured harmonisation across heterogeneous data sources and, importantly, prevented the socioeconomic dimension from outweighing the agronomic criteria within the composite model. The binary structure reflects an intentional weighting strategy rather than a strict representation of underlying socio-economic gradients, as for the value chain development crop suitability in terms of agronomic criteria (with no need of major interventions) was considered a priority.

2.3. Spatial Classification and Prioritisation

- High suitability: 10–12 points.

- Moderate suitability: 7–9 points.

- Marginal suitability: 5–6 points.

- Low suitability: <5 points.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of Agronomic Requirements

3.2. Socioeconomic and Territorial Development Opportunities

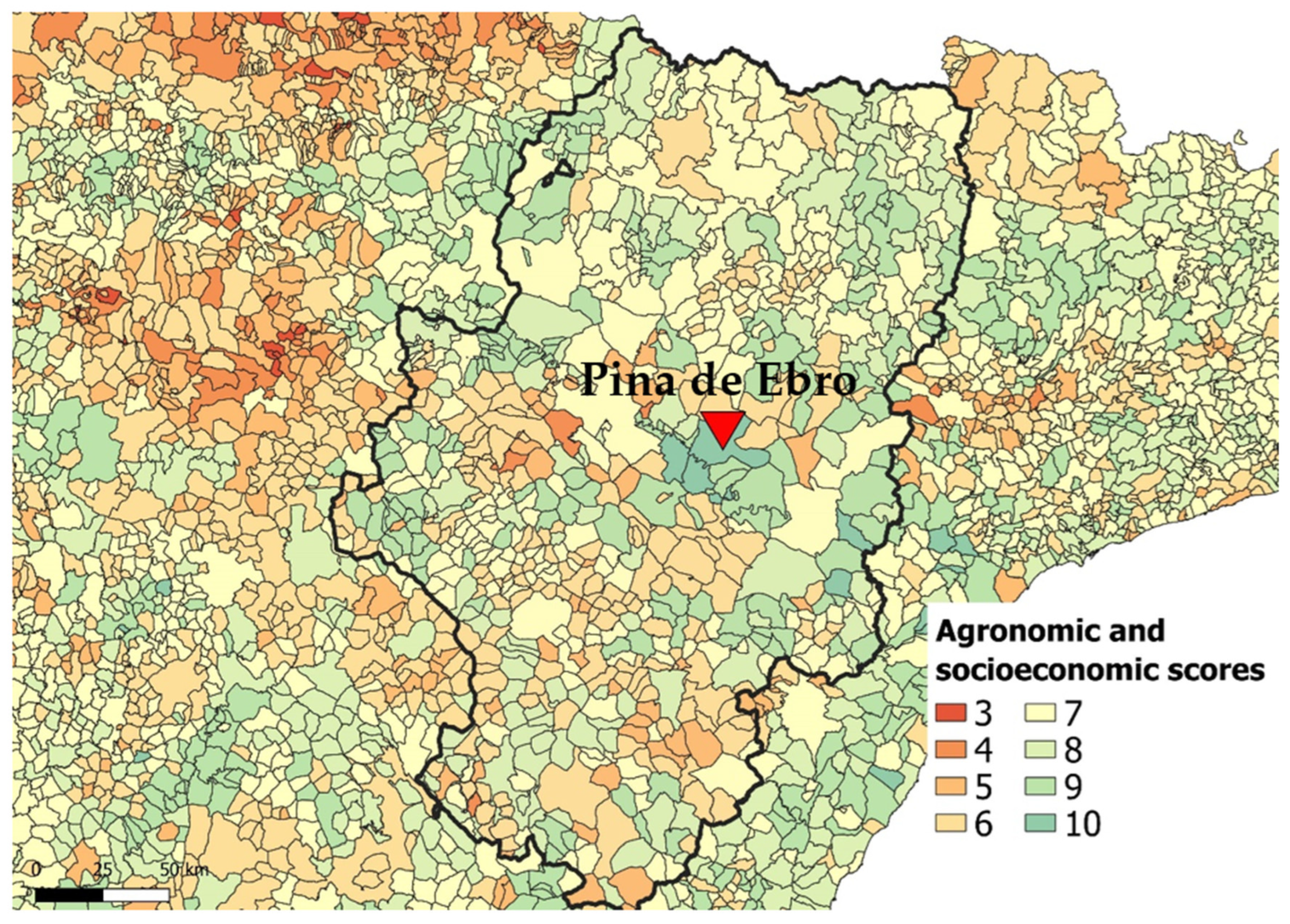

3.3. Composite Suitability Score

- High-priority zones (scores 10–12), where liquorice cultivation could simultaneously improve land-use efficiency and contribute to rural development goals.

- Moderate-suitability areas (scores 7–9), where either the agronomic or social dimension is partially met.

- Low-suitability municipalities (≤6), which may require substantial adaptation or be excluded from short-term planning.

3.4. Case Study: The EcoRadiz Project

- Resuming the cultivation of a traditional crop with deep cultural roots in the region.

- Generating employment opportunities for socially vulnerable women, with a flexible, self-managed working model.

- Promoting organic farming and sustainable resource use, including solar energy and local wool-based insulation.

- Cultivation trials on 1 hectare of municipal land, using 400 kg of initial planting material.

- Acquisition of 4000 kg of organic liquorice root from other Spanish producers for early-stage processing tests.

- Interior refurbishment of the workshop using sustainable materials and installation of 8 (from a capacity of 12) solar panels.

- Training of 14 women in agro-processing tasks, with four of them expected to lead the daily operations.

3.5. Synthesis, Strategic Reflections and Limitations

- The model is based on static climatic averages and does not account for interannual variability or future climate scenarios.

- Soil data is restricted to pH, without factoring in salinity, organic matter, or texture factors that may influence crop performance.

- The socioeconomic dimension includes only three indicators; other factors such as age structure, land tenure, or value chain maturity were not incorporated due to data limitations.

- The scoring thresholds, while grounded in the literature, still involve subjective categorization and can benefit from expert calibration or stakeholder validation processes.

- Although native or long-established in Spain, G. glabra can expand vigorously in riparian areas. The model omits ecological-risk indicators, which should be integrated in future assessments.

- The current scoring system relies on broad threshold categories for socioeconomic indicators; more granular classes could enhance the robustness of the assessment and bring the framework closer to formal MCDA standards.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Optimal growing conditions correspond to areas with mean annual temperatures above 16 °C, neutral to slightly alkaline soils (pH 6.5–7.5), and annual precipitation between 500 and 1000 mm.

- Southern and southwestern regions, particularly Andalusia, Extremadura, and Castilla-La Mancha, are identified as high-potential regions in terms of combined environmental and social suitability.

- Moderate-potential zones exist across eastern and interior Spain, where targeted interventions could unlock productive capacity.

- Northern regions present structural limitations for cultivation but may serve niche purposes under specific conditions or as part of experimental pilot schemes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

| CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| EAFRD | European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development |

| EC | European Commission |

| ESDAC | European Soil Data Centre |

| ETRS89/UTM Zone 30N | European Terrestrial Reference System 1989/Universal Transverse Mercator Zone 30 North |

| EU | European Union |

| GBIF | Global Biodiversity Information Facility |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| INE | Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spanish Statistical Office) |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre (European Commission) |

| MAPA | Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (Spain) |

| OEC | Observatory of Economic Complexity |

| REACH | Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (EU Regulation) |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| WITS | World Integrated Trade Solution |

| WMS | Web Map Services |

References

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- European Commission. Bioeconomy Strategy. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/bioeconomy-strategy_en (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Rodríguez Franco, R.; Ibancos Núñez, C. Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico/Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/biodiversidad/temas/inventarios-nacionales/iect_glycyrrhiza_glabra_tcm30-164110.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Seedaholic. Liquorice, Glycyrrhiza glabra. Available online: https://www.seedaholic.com/siol/liquorice-glycyrrhiza-glabra-organic/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Botanical.com. Liquorice. Available online: https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/l/liquor32.html (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Egamberdieva, D.; Ma, H.; Alaylar, B.; Zoghi, Z.; Kistaubayeva, A.; Wirth, S.; Bellingrath-kimura, S.D. Biochar Amendments Improve Licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.) Growth and Nutrient Uptake under Salt Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Zheng, X.; Luo, J.; Lu, J. Integrative Physiology and Transcriptome Reveal Salt-Tolerance Differences between Two Licorice Species: Ion Transport, Casparian Strip Formation and Flavonoids Biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardes, M.; de la Sen, P. D4.3—Network-Based Local Business Models; Horizon Europe Project BIOLOC, European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, P.; Kong, W.; Cheng, L.; Shi, N.; Wang, S.; Guo, F.; Shen, H.; Yao, H.; Li, H. Effects of Licorice Stem and Leaf Forage on Growth and Physiology of Hotan Sheep. Animals 2025, 15, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, S.; Annadurai, S.; Abullais, S.S.; Das, G.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, M.F.; Kandasamy, G.; Vasudevan, R.; Ali, M.S.; Amir, M. Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice): A Comprehensive Review on Its Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, Clinical Evidence and Toxicology. Plants 2021, 10, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria Natural. LICORICE. Available online: https://www.sorianatural.es/en/enciclopedia-de-plantas/regaliz (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Mount Sinai. Licorice. Available online: https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/herb/licorice (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Kushiev, K.H.; Ibragimov, K.M.; Rakhmonov, I.; Karimov, A. The Rol of Licorice for Remediation of Saline Soil. Open J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 4, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.zbks44 (accessed on 9 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- World Integrated Trade Solution. Spain Liquorice Sap and Extract Imports by Country in 2023. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/ESP/year/2023/tradeflow/Imports/partner/ALL/product/130212 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- World Integrated Trade Solution. Liquorice Sap and Extract Exports by Country in 2023. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/ALL/year/2023/tradeflow/Exports/partner/WLD/product/130212 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Superficies y Producciones Anuales de Cultivos. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/estadistica/temas/estadisticas-agrarias/agricultura/superficies-producciones-anuales-cultivos/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- OEC. Liquorice Extract. Available online: https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/liquorice-extract (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- imarc. Licorice Extract Market Size, Share, Trends, and Forecast by Product Type, Form, Application, and Region, 2025–2033. Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/licorice-extract-market (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Global Market Insights. Licorice Extract Market Size—By Grade (Pharmaceutical, Food, Feed), by Form (Liquid, Powder, Block, Others), by Application (Food & Beverages, Pharmaceutical, Tobacco, Others), Growth Prospects, Regional Outlook & Forecast, 2024–2032. Available online: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/licorice-extract-market (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Future Market Insights. Licorice Extract Market Analysis—Size, Share, and Forecast Outlook 2025 to 2035. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/licorice-extract-market (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Ecoradiz—Tienda. Available online: https://ecoradiz.com/tienda/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Merck Glycyrrhizin. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/ES/es/product/aldrich/cds020796 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Government of Netherlands. The European Market Potential for Liquorice. Available online: https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/natural-ingredients-cosmetics/liquorice/market-potential (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- González, C.G.; Perpinyà, A.B.; Tulla I Pujol, A.F.; Martín, A.V.; Belmonte, N.V. Social Farming in Catalonia (Spain): Social Innovation and Agroecological Dynamization as Employment for Exclusion. Ager 2014, 16, 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulla, A.F.; Vera, A.; Valldeperas, N.; Guirado, C. New Approaches to Sustainable Rural Development: Social Farming as an Opportunity in Europe? Hum. Geogr. 2017, 11, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Revitalizing Territories via Social and Digital Innovation; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- Alsaadi, D.H.M.; Raju, A.; Kusakari, K.; Karahan, F.; Sekeroglu, N.; Watanabe, T. Phytochemical Analysis and Habitat Suitability Mapping of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. Collected in the Hatay Region of Turkey. Molecules 2020, 25, 5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Huang, X.; Yang, Z.; Niu, P.; Pang, K.; Wang, M.; Chu, G. Suitable Habitat Prediction and Desertified Landscape Remediation Potential of Three Medicinal Glycyrrhiza Species in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, H.; Karami, A.; Hadian, J.; Saharkhiz, M.J.; Nejad Ebrahimi, S. Variation in the Phytochemical Contents and Antioxidant Activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra Populations Collected in Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 137, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.A.; Bajwa, N.; Chinnam, S.; Chandan, A.; Baldi, A. An Overview of Some Important Deliberations to Promote Medicinal Plants Cultivation. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2022, 31, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Temperatura Media Anual (°C). Available online: https://www.mapama.gob.es/ide/metadatos/srv/api/records/6e36f18a-6f12-47aa-bfb5-060ab8382eff?language=all (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Pluviometría Media Anual. Available online: https://www.mapama.gob.es/ide/metadatos/srv/api/records/10696290-e0e5-4486-bf1f-e4ad370ce5d5?language=all (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- JRC European Commission. Ph in Europe. Available online: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/soil-ph-europe#tabs-0-description=0 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Demografía de la Población Rural en 2020; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- INE. Cifras Oficiales de Población de Los Municipios Españoles. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177011&menu=resultados&idp=1254734710990 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Rankel, K. Optimal Temperature for Your Licorice. Available online: https://greg.app/licorice-temperature/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- PictureThis. Ideal Temperature Range for Licorice. Available online: https://www.picturethisai.com/care/temperature/Glycyrrhiza_glabra.html (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Rankel, K. What Temperature Should My Liquorice Be Kept At? Available online: https://greg.app/liquorice-temperature/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Waddington, E. How to Grow a Liquorice Plant in The UK. Available online: https://blog.firsttunnels.co.uk/liquorice-plant-grow/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Fry, J.C. Natural Low-Calorie Sweeteners. In Natural Food Additives, Ingredients and Flavourings; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikaspedia. Glycyrrhiza glabra. Available online: https://agriculture.vikaspedia.in/viewcontent/agriculture/crop-production/package-of-practices/medicinal-and-aromatic-plants/glycyrrhiza-glabra-1?lgn=en (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Manitoba. Wild Licorice. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/agriculture/crops/crop-management/wild-licorice.html#:~:text=Area%20Of%20Adaptation,full%20sun%20or%20partial%20shade (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Rankel, K. 5 Secrets to Successfully Grow Australian Licorice. Available online: https://greg.app/how-to-grow-australian-licorice/#:~:text=%F0%9F%94%AC%20Soil%20pH%20and%20Nutrient,the%20right%20environment%20to%20thrive (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Rankel, K. 5 Do’s and Don’ts of Growing Licorice. Available online: https://greg.app/how-to-grow-licorice/#:~:text=%F0%9F%8C%B1%20Soil%20Type%20and%20Composition,ranges%20from%206.0%20to%208.0 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Ministerio de Trabajo y Economía Social. Estadísticas Por Municipios (Paro Registrado y Contratos). Available online: https://www.sepe.es/HomeSepe/es/que-es-el-sepe/estadisticas/datos-estadisticos.html (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Lim, T.K. Glycyrrhiza glabra. In Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 354–457. [Google Scholar]

- Roya Botanic Gardens Kew. Glycyrrhiza glabra L. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:496941-1 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- A. Vogel A Plant Encyclopedia Glycyrrhiza glabra L. Available online: https://www.avogel.ch/en/plant-encyclopaedia/glycyrrhiza_glabra.php (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Ugoeze, K.C.; Odeku, O.A. Herbal Bioactive–Based Cosmetics. In Herbal Bioactive-Based Drug Delivery Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collantes, F.; Pinilla, V. La Verdadera Historia de la Despoblación de la España Rural y Cómo Puede Ayudarnos a Mejorar Nuestras Políticas; Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio García de Oteyza, M.; Gutierrez Sanchis, A.; Conde Lopez, J. The Problem of Rural Depopulation in Spain. Towards a Sustainable, Person-Centred Model of Repopulation; Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- Pinilla, V.; Luis, Y.; Sáez, A. La Despoblación Rural en: Génesis de un Y Políticas; Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- BBVA. La Despoblación Rural: Crónica de Una Desaparición Anunciada. Available online: https://www.bbva.com/es/sostenibilidad/la-despoblacion-rural-cronica-de-una-desaparicion-anunciada/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Greenpeace. Los Problemas de La España Vaciada. Available online: https://es.greenpeace.org/es/en-profundidad/salvar-el-planeta-desde-la-espana-vaciada/los-problemas-de-la-espana-vaciada/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Renacimiento Demografico. Que Es La Despoblación. Available online: https://renacimientodemografico.org/que-es-la-despoblacion/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- arete activa. La Despoblación, El Presente y Gran Reto de Las Sociedades. Available online: https://www.arete-activa.com/factores-despoblacion-palancas-evitarla/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Plants For A Future Glycyrrhiza glabra—L. Available online: https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Glycyrrhiza+glabra (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Khaitov, B.; Karimov, A.; Khaitbaeva, J.; Sindarov, O.; Karimov, A.; Li, Y. Perspectives of Licorice Production in Harsh Environments of the Aral Sea Regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhanova, U.; Ibraeva, M. Phytoremediation of Saline Soils Using Glycyrrhiza glabra for Enhanced Soil Fertility in Arid Regions of South Kazakhstan. Eurasian J. Soil. Sci. 2025, 14, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushiev, K.H.; Kuralova, R.M.; Roziboyeva, M.B.; Djurayev, M.E. The Role of Glycyrrhiza glabra for Remediation of Soil Fertility. Int. J. Progress. Sci. Technol. 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, M.; Razmi, J.; Ghodsi, R. A Combined Fuzzy PCA Approach for Location Optimization and Capacity Planning in Glycyrrhizae Green Supply Network Design. J. Eng. Res. 2019, 7, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghlima, G.; Tafreshi, Y.M.; Aghamir, F.; Ahadi, H.; Hatami, M. Regional Environmental Impacts on Growth Traits and Phytochemical Profiles of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. for Enhanced Medicinal and Industrial Use. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EcoRadiz. Available online: https://ecoradiz.com/regaliz/regaliz-palo-cultivo/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Haghighi, T.M.; Saharkhiz, M.J.; Kavoosi, G.; Zarei, M. Adaptation of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. to Water Deficiency Based on Carbohydrate and Fatty Acid Quantity and Quality. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrollahi, V.; Mirzaie-Asl, A.; Piri, K.; Nazeri, S.; Mehrabi, R. The Effect of Drought Stress on the Expression of Key Genes Involved in the Biosynthesis of Triterpenoid Saponins in Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra). Phytochemistry 2014, 103, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Xiao, G.; Wang, S. Suitability Evaluation of Potential Arable Land in the Mediterranean Region. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 313, 115011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıc, O.M.; Ersayın, K.; Gunal, H.; Khalofah, A.; Alsubeie, M.S. Combination of Fuzzy-AHP and GIS Techniques in Land Suitability Assessment for Wheat (Triticum aestivum) Cultivation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 2634–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Alonso, N.; Viedma-Guiard, A.; Simón-Rojo, M.; Córdoba-Hernández, R. Agricultural Land Suitability Analysis for Land Use Planning: The Case of the Madrid Region. Land. 2025, 14, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, P.; Fiorentino, C.; AbdelRahman, M.A.E.; Sannino, M.; Scalcione, E.; Lacertosa, G.; Modugno, F.; Marsico, A.; Donvito, A.R.; Conceição, L.A.; et al. Modeling Climatic, Terrain and Soil Factors Using AHP in GIS for Grapevines Suitability Assessment. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 970–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, P.; Malacrinò, A.; Campolo, O.; Laudani, F.; Algeri, G.M.; Giunti, G.; Strano, C.P.; Benelli, G.; Palmeri, V. A Novel GIS-Based Approach to Assess Beekeeping Suitability of Mediterranean Lands. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trialfhianty, T.I.; Muharram, F.W.; Suadi; Quinn, C.H.; Beger, M. Spatial Multi-Criteria Analysis to Capture Socio-Economic Factors in Mangrove Conservation. Mar. Policy 2022, 141, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Schuurman, N.; Hayes, M.V. Using GIS-Based Methods of Multicriteria Analysis to Construct Socio-Economic Deprivation Indices. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2007, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penny, J.; Khadka, D.; Alves, P.B.R.; Chen, A.S.; Djordjević, S. Using Multi Criteria Decision Analysis in a Geographical Information System Framework to Assess Drought Risk. Water Res. X 2023, 20, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- María, J.; Urrecho, D.; Martínez, C.; Fernández, L. Ageing and Population Imbalances in the Spanish Regions with Demographic Challenges; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC): Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- Jara Santiago, L. The Journal of International Media, Communication, and Tourism Studies No.3 7|069 Rural Development Trough Remote Working in Regions Rich in Rural Tourism Resources-1. J. Int. Media Commun. Tour. Stud. 2007, 3, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Demographic Indicators ANTONIO ABELLÁN CSIC 1.1. Size and Evolution; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC): Madrid, Spain. Available online: http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/imserso-agespacap1-01.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- From Strategy to Action for a Regional, Participatory, and Sustainable EU Bioeconomy from Strategy to Action for a Regional, Participatory, and Sustainable EU Bioeconomy Evidence and Recommendations from RuralBioUp, SCALE-UP, BioRural, and MainstreamBIO; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Bioregions. How Can European Regions Help Develop the Bioeconomy? Available online: https://bioregions.efi.int/european-regions-help-develop-the-bioeconomy/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- EU CAP Network. Revitalising Rural Europe: Success Stories from the Rural Inspiration Awards 2019. Available online: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/publications/revitalising-rural-europe-success-stories-rural-inspiration-awards-2019_en (accessed on 28 November 2025).

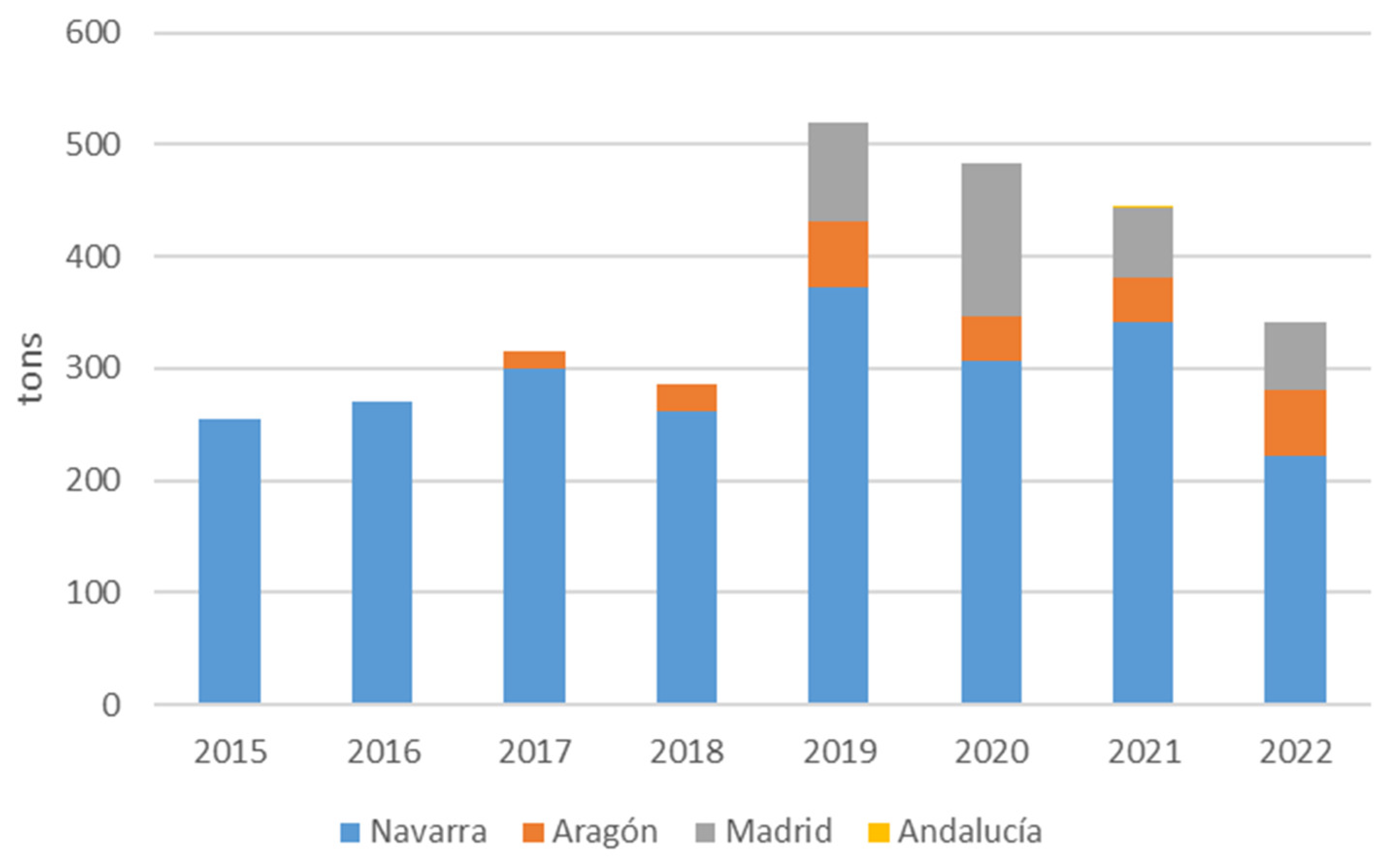

| Province | Rainfed Surface (ha) | Irrigated Surface (ha) | Total Surface (ha) | Performance Rainfed/Irrigated (kg/ha) | Production (tons) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navarra | — | 108 | 108 | -/2045 | 221 |

| Aragón | 16 | 19 | 35 | 719/2500 | 59 |

| Madrid | — | 21 | 21 | -/2975 | 62 |

| Criterion | Range/Class | Score | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean annual temperature | 20–25 °C | 3 | [37,38,39,40] |

| 17–19.9 °C or 25.1–27 °C | 2 | ||

| 14–16.9 °C or 27.1–29 °C | 1 | ||

| <14 °C or >29 °C | 0 | ||

| Water Availability (precipitation + floodplain proximity) | 500–1000 mm/year and near flood-prone zone | 3 | [41,42] |

| 500–1000 mm/year or near flood-prone zone | 2 | ||

| 400–499 mm/year, no floodplain | 1 | ||

| <400 mm or arid | 0 | ||

| Soil pH | 6.5–7.5 (optimal) | 3 | [41,42,43,44,45] |

| 6.0–6.49 or 7.51–8.0 | 2 | ||

| 5.5–5.99 or 8.01–8.5 | 1 | ||

| <5.5 or >8.5 | 0 | ||

| Depopulation trend | Sustained population decline (2014–2024) | 1 | [36] |

| Rural classification | Municipality with less than 30,000 inhabitants | 1 | [35] |

| Unemployment | Rate above national average | 1 | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ocamica, V.F.; Figueirêdo, M.B. Liquorice Cultivation Potential in Spain: A GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411299

Ocamica VF, Figueirêdo MB. Liquorice Cultivation Potential in Spain: A GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411299

Chicago/Turabian StyleOcamica, Víctor Fernández, and Monique Bernardes Figueirêdo. 2025. "Liquorice Cultivation Potential in Spain: A GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411299

APA StyleOcamica, V. F., & Figueirêdo, M. B. (2025). Liquorice Cultivation Potential in Spain: A GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Assessment for Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainability, 17(24), 11299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411299