Abstract

Degrowth scholars emphasize the importance of the foundational economy (FE) for ‘living well within planetary boundaries’. The foundational economy describes the provision and regulation of everyday goods and services needed for the satisfaction of basic needs, such as housing, care, education, energy, food and mobility. However, there is a lack of conceptual models linking FE production and consumption to biodiversity conservation and restoration. This paper develops an ecological–economic model of ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, and the foundational economy. It embeds FE sectors in the whole economy and provides economic arguments both on the supply side (e.g., economies of scale, scope and density; transaction costs) as well as on the demand side (e.g., trust in institutions; universal basic services; willingness to accept changes) in favor of resource efficiency. Compared to extractive and financialized business models, the FE production has major environmental advantages, especially if connected to public and not-for-profit economic activities. Though FE production is certainly a necessary condition for biodiversity conservation, it is not per se a sufficient strategy. The foundational economy is also embedded in natural processes; thus, respective institutional, legal and economic frameworks are needed to limit the environmental impacts of FE.

1. Introduction

The state of biodiversity (genetic, species, ecosystem, and landscape diversity) is dramatic and has worsened over the last 50 years [1]. Since the adoption of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, international and national efforts to halt biodiversity loss have resulted in a wide range of treaties and agreements that aim to fulfill the main goals of the CBD, i.e., to conserve biodiversity, to sustainably use biodiversity components, and to fairly and equitably share the benefits of biodiversity conservation, especially in regard to genetic resources [2]. Biodiversity is generally defined as the “variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems” (Article 2 of the CBD [2]). Assessments of the outcomes of biodiversity conservation policies suggest that the success of the CBD was rather limited. For instance, Perrings et al. [3] demonstrate that signatory countries to the CBD have significantly failed to meet the target of halting biodiversity until 2010. The authors list two main reasons for the failure to achieve these goals. Firstly, the underlying causes and drivers of biodiversity loss [4,5,6,7] were not addressed accordingly. Driving forces, pressures, state changes, impacts and responses (DPSIR framework) of biodiversity loss have been systematically studied in various contexts and fields, and levels and granularity of biodiversity [5,7]. Secondly, the goals and objectives of the 2010 CBD frameworks were vague, lacking binding targets to be achieved [3].

The most recent significant international agreement within the framework of the CBD is the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) [8], which sets new ambitious goals for 2030 and 2050, and considers the various reasons of failure of earlier treaties. By 2030, at least 30% of the terrestrial, inland water, marine and coastal ecosystems that are the most important for the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services should be effectively protected. In addition, 30% of the most degraded ecosystems should have been effectively restored [9,10,11]. Until 2050, no further biodiversity loss (species loss) should occur [2].

The GBF includes 23 targets to be fulfilled by the parties to the framework in three broad policy areas (goals): reducing threats to biodiversity, meeting people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit-sharing, and providing tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming [10].

As will be discussed in more detail below (Section 2.2), these exemplary GBF targets are also, in a broader sense, policy goals of the foundational economy. The foundational economy as a term and concept broadly relates to two scientific perspectives. First, it is a positive (descriptive) concept assessing the importance and size of different economic sectors satisfying (basic) human needs. This includes the distinction between private and public, market and non-market provisions of basic goods and services. Second, it is a normative (prescriptive) model that provides numerous conclusions for economic, social and environmental policies. The latter may include suggestions for biodiversity conservation and restoration, and also aims to provide the basis for living well within planetary boundaries (e.g., [12]). The links between environmental health, resource/energy use, and the satisfaction of human needs through provisioning systems, such as the foundational economy, have rarely been studied to date (a notable exception is the study by [13]; see Section 2 for more details). Among other reasons, the separation of discourses on sustainability and the effects of economic growth in the natural and social sciences may be an important reason for these research gaps. In specific regard to the mediation of resource use—and thus, among others, effects on biodiversity—current theories of provisioning systems appear to have room for improvement [12] (pp. 7f).

In the European Union, the Birds and Habitats Directives (Natura 2000 network) are the most important frameworks for the conservation of biodiversity [14,15]. One of the basic principles of biodiversity conservation is the legal provision that the good environmental status (GES) of a species or ecosystem should be preserved permanently or achieved within a certain timeframe. Although there are still problems in regard to the effectiveness of implementation and a lack of specific knowledge, the two directives, including the Natura 2000 network, have produced impressive outcomes. The network is regularly touted as the world’s largest network of protected areas [16,17,18].

To reduce the threats to biodiversity conservation through ecological resilience, several funding programs were set up (such as the LIFE program). In 2024, the European Parliament and the Council passed the Nature Restoration Law [19], which obliges member states to enhance the ecological status of ecosystems [19].

Although these global and European biodiversity conservation frameworks include some provisions, this brief sketch emphasizes that the fundamental connections between the foundational economy and biodiversity conservation and restoration have not yet been considered appropriately. This paper fills this conceptual research gap by providing these missing links, as well as the shortcomings of the FE model about biodiversity conservation. It thus has a fourfold purpose: Its first aim is to describe the potential connections between the foundational economy, resource use and biodiversity. Second, it places the foundational economy in context to other sectors of the economy and discusses the potential benefits in regard to biodiversity conservation and restoration.

Third, it conceptualizes the linkages between biodiversity, ecosystem services and the foundational economy within a novel ecological–economic model. A variety of economic concepts are described to outline how the foundational economy could contribute to biodiversity conservation, and why the foundational economy may even be considered a cornerstone of future biodiversity conservation and restoration. Furthermore, it connects the DPSIR framework to the potential responses of the FE model in each step. With this approach, the shortcomings and missing or insufficient responses of the FE become apparent as well. Fourth, the paper describes specific strategies and economic policies of the foundational economy, especially in regard to achieving the common good by emphasizing not-for-profit or limited-profit business models, and by largely ending extractive economic activities. These policies could support reducing material throughput and the various other drivers of biodiversity loss and thus enhance biodiversity conservation. However, it should be noted that while the foundational economy is a necessary economic provisioning system embedded in ecological processes, it is by no means sufficient as a stand-alone strategy. For instance, the FE may be efficient in terms of reducing the ecological footprint per unit of service but does not per se provide an upper boundary to resource consumption. This paper, therefore, contributes to the literature on the conceptualization of the foundational economy as a means of securing the satisfaction of basic needs and as a vital component of ecological sustainability, sufficiency and biodiversity conservation.

Methodologically, this paper follows a conceptual approach and is based on a systematic and narrative scoping review, using Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases. Keywords included ‘foundational economy’, ‘biodiversity’, ‘sufficiency’, ‘environmental’ and ‘resilience’. While the databases produce long lists for each of these, papers dealing with a combination of these strings are very rare. For instance, at the time of the writing of this paper, WoS lists a mere 67 papers in total on the ‘foundational economy’ concept, none of which refer to the combination with ‘biodiversity’. A mere ten papers combine the FE and ‘environment*’. Based on these searches, this paper thus conceptualizes the foundational economy from a theoretical and policy-oriented perspective and discusses its connections, impacts and dependencies with environmental concerns such as the conservation of biodiversity. Most scholarly studies on the foundational economy are from European researchers. While the conceptualization of the linkages between the foundational economy and biodiversity conservation does not have a certain regional focus in mind and is, therefore, globally applicable, this paper is certainly embedded in the European debate and does not account for other regions’ specificities or frameworks, which might be vastly different in non-European regions.

The paper is organized as follows: A brief literature review on selected aspects of the connections between the foundational economy and the environment is presented in Section 2. In Section 3, the conceptual ecological–economic model is discussed, while Section 4 includes the economic strategies that improve the sustainability of the foundational economy. Finally, Section 5 provides a discussion, summary and policy conclusions.

2. The Foundational Economy and the Environment: A Brief Overview

2.1. Basic Conceptualizations of the Foundational Economy

Several concepts and descriptions of the foundational economy (FE) and its parts have been put forward in scientific discourse. The Foundational Economy Collective [20] programmatically described the FE as the infrastructure of everyday life in 2020. Taking up the idea of the everyday economy, the Competence Center for Infrastructure Economics, Public Services and Social Provisioning [21] describes the foundational economy as providing goods and services that are needed every day. The concept thus not only includes all kinds of (mostly public) infrastructure (e.g., technical and network, social, housing and institutional infrastructure) but also accounts for other branches of the economy such as local food supply, repair services, and retail banking. Bärnthaler et al. [22] differentiate the foundational economy even further into the unpaid local care and reproduction activities, and delineate the FE from market-driven, export-oriented production, and the extractive financialized parts of the economy [12]. These sectors contribute little to human well-being but instead serve to distribute wealth unequally (see Table 1 below). The latter is problematic because resource consumption and negative impacts on biodiversity are much larger in high-income households (e.g., [23]).

The concept of the foundational economy is thus closely linked to degrowth and sufficiency discourses, and to a critique of the current capitalist economic system [24]. On the one hand, the foundational economy is merely a descriptive or conceptual model of a part of the economy, emphasizing the importance of structurally less recognized sectors of the economy such as the care sectors (both paid and unpaid) [25]. However, the concept of providing goods and services of general economic interest (‘Daseinsvorsorge’ is German for fundamental public services) does not capture both the breadth and depth of the foundational economy concept, nor does it question economic paradigms of growth or efficiency.

On the other hand, as will be discussed in more detail below, the foundational economy presents a normative framework enhancing biodiversity conservation and restoration as it supports the respect for planetary boundaries and thus sustainable development, and can also facilitate debates on production and consumption corridors [26]. The latter concept operationalizes the donut economy framework [27] as it discusses the idea that resource use may have lower limits in order to satisfy basic human needs, but at the same time, upper boundaries of resource use are also limited by the Earth’s capacity to sustainably provide resources for the human economy and society. As a normative concept, the foundational economy contrasts with standard (neoclassical) models of the functioning of markets and the growth of the economy as it basically puts the satisfaction of human needs and a ‘good life for all within planetary boundaries’ at the center of debate. As such, the concept has also found some traction in policy programs in the UK [28] as well as in Austria (cf. [29,30]). The concept thus combines alternative allocation, provision and distribution systems of resources and services based on human needs and supports social cohesion and democratic governance.

The foundational economy is a foremost needs-based concept (instead of market-driven willingness-to-pay), which regulates, provides for and funds the satisfaction of basic needs for all citizens [31]. Through covering needs, human well-being is directly supported, instead of relying on the hope for trickle-down effects of economic growth, which has not materialized for large groups of the population over the last two decades [32].

The access to foundational infrastructure, however, is currently unevenly distributed. Riepl et al. [33] study the implications of the foundational economy in regard to the spatial accessibility of foundational infrastructures using Vienna, Austria as a case-study. Households with a low socio-economic status (e.g., below-average household income) tend to have worse access to foundational infrastructures, such as social infrastructure (e.g., healthcare, education, and green spaces, all as part of the providential foundational economy; see [22]). These results highlight the importance of additional frameworks that support FE goals, such as equal access to foundational infrastructure.

While this paper emphasizes the foundational economy as a comprehensive alternative socio-economic model based on needs facilitating a sustainable economic degrowth path, there are, of course, other approaches, such as the well-being economy (WE) and community wealth building (CWB) that address specific elements of sustainability policies [34]. The FE model is thus not considered as being exclusive, but inclusive by combining—also in a historical perspective [35]—other economic policy approaches in a joint framework.

To some extent, the foundational economy has also been conceptualized as a new approach to local development, similar to WE and SWB strategies. Sissons and Green [36] discuss the development of the foundational economy in the context of employment and job quality at a local level. They argue, in line with the general discourse, that the foundational economy provides a new model of development not only in terms of the importance of different branches of the economy but also in terms of new approaches to economic decision-making, including considering sustainable development and the environmental impacts of development.

While the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are generally considered as equally important, their potential synergies (and less frequently, trade-offs) are rarely discussed in planning foundational infrastructures. There are, of course, close linkages between biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, and other policy fields. Shin [37] (p. 3) writes: “The close interlinkages between biodiversity, climate change mitigation, other nature’s contributions to people and good quality of life are seldom as integrated as they should be in management and policy.” Interestingly, as will be discussed below, the linkages between the foundational economy and biodiversity conservation and restoration remain to be conceptualized to date.

The foundational economy not only proposes an alternative economic line of thinking but also rests on new perspectives of spatial and urban development [38,39], and the relations between local and regional entities. With a focus on the common good of social and economic development, the FE emphasizes cooperation not only on the local but also on the interregional and international levels. Essletzbichler [40] compares three broad scenarios of (urban) development: liberal globalism, nationalistic capitalism, and the foundational economy. The first two approaches focus on (neo-)liberal policies at a global or national scale, whereas the foundational economy pursues the idea of a “grounded city”, in which the economy is first and foremost a provisioning system that serves the needs of the local (urban) population. Social risks and precarious working conditions are reduced in mutual relations and social dependence on each other. Social rights are considered a duty to be fulfilled by all members of society. The author views the FE as being firmly grounded in local contexts, offering perspectives for national and international cooperation, and as an alternative socio-economic model for social–ecological transformation. As such, the FE model provides an important element of transformative strategies, but—as a limitation—does not detail biodiversity conservation strategies or frameworks.

Table 1.

Areas of the economy, including the foundational economy, and the connections to the social–ecological transformation and biodiversity conservation and restoration (Source: own concept and draft based on works from [20,22,33]).

Table 1.

Areas of the economy, including the foundational economy, and the connections to the social–ecological transformation and biodiversity conservation and restoration (Source: own concept and draft based on works from [20,22,33]).

| Unpaid | Paid economic activities (registered in the national accounts and statistics) | Paid economic activities (profits concealed & taxes avoided, often not in national accounts) | ||||

| Everyday Economy | Export-oriented market economy (international competition) | Extractive/rentier economies | ||||

| Core economy: Care, reproduction, voluntary work | Foundational Economy (FE) * Material foundational economy, * Providential foundational economy, * Contested FE | Non-essential local provisioning | ||||

| (Public/not-for-profit) infrastructure (technical/network, social infrastructure) | Essential local provisioning systems | Non-market free provisioning & access (Nature’s contributions, cultural goods & services) | ||||

| Examples of the different areas of the economy | ||||||

| Unpaid care work (family work, community), reproductive household duties, child care, civil society engagement (e.g., NGOs) | Utilities (water, waste management), health, care, education, energy | Food, pharmacies, local/retail banks, repair, local production of essential goods (e.g., clothing) | Recreation areas, biodiversity conservation, public spaces, cultural institutions | Restaurants, hair dresser, books, furniture | Cars, computers, machinery, chemicals | Financial products, services, markets; high frequency trading, financialized services, resources trading & speculation |

| Spatial importance | ||||||

| Local, small-scale | Local/regional, domestic economies | Local/regional, domestic economies | Mostly local/regional | Local/regional, domestic economies | International/global | Global |

| Temporal dimension | ||||||

| Long-term (reproduction cycles, generational perspectives) | Long-term provisioning, long technical life span | Long-term business models | Long-term, intergenerational | Both short- & long-term business models | Short- & medium-term investment & development cycles | (Very) short-term |

| Basic means of provisioning (supply-side) | ||||||

| Reciprocity, altruism, solidarity | Public, not-for-profit, limited-profit, strongly regulated markets | Local/regional regulated markets | Public planning & provisioning (including funding) | Local/regional regulated markets | Markets, (international) trade between companies, trade agreements | (Financial) markets, appropriation, value extraction, Regulatory Capture |

| Basic means of need satisfaction/use/consumption (demand side) | ||||||

| Non-monetary, no markets or public provisioning involved | Basic everyday use of goods and services of general interest | Everyday use | Use and non-use values, co-production | Consumption of comfort goods and services, important for inclusion/social participation | Private status/luxury consumption | Extraction of values for wealth accumulation & redistribution |

| Strategies and potential policy approaches from the view of social-ecological transformation and a “good life within planetary boundaries” | ||||||

| Improvement of overall conditions, social acceptance & recognition, potential incentives/support for safeguarding the provisioning systems | Expansion, complementing fields, decommodification, municipalization, decommodification, ecologicalization, Improvement of the working conditions | Expansion (e.g., biodiversity loss, climate change), precautionary principle (e.g. mental health), decommodification, democratic governance & local inclusion | Support of local/regional provisioning & production, differentiated policies of ecologicalization and inclusion | Substantial structural changes necessary, selective growth & shrinkage | Significant restrictions & reduction of extractive business models that are detrimental to the environment and social justice | |

| Connections to biodiversity conservation & restauration (production & supply side) | ||||||

| Low material inputs, human care labor, personal services with low environmental impacts; personal information & education enhancing ecological knowledge & awareness for biodiversity | Satisfaction of basic needs within planetary boundaries: large economies of scale and scope, minimized use of land & resources, planning & regulation can restrict biodiversity loss | Local provisioning systems can be seasonal & regional (for most goods), potential for resource-saving circular economy, negative impacts on biodiversity immediately noticeable | Biodiversity conservation & restoration central to non-market goods & services; essential for recreation, education & caring about biodiversity | Local & regional systems within planetary boundaries & circular economy, regulation of land & resource use, planning for biodiversity conservation & regulation | Circular economy difficult to achieve (global value chains), remote & distant resource extraction & mining, international regulation of biodiversity with obstacles & ineffective | Value extraction for wealth accumulation leads to high overconsumption of wealthy households responsible for disproportionally huge environmental impacts such biodiversity loss (per capita & in absolute terms) |

| Connections to biodiversity conservation & restauration (demand side) | ||||||

| Social security, equity & fairness, welfare, coverage of universal basic needs, and trust all increase acceptance of biodiversity conservation & restoration policies, even at the cost of reductions in income/output. | International competition may locally & regionally increase insecurity and the believe of a “race to the bottom” | Inequality, wealth accumulation decrease trust & social cohesion, and undermine democratic institutions and governance, thus is detrimental to biodiversity conservation | ||||

2.2. Concepts and Values of Biodiversity Conservation: Connections to the Foundational Economy

Before detailing the foundational economy and its linkages to biodiversity conservation and restoration, it is necessary to clarify biodiversity as understood in natural sciences, and the various potential values attributed to biodiversity conservation and restoration, as well as the drivers of biodiversity loss and the overshoot of planetary boundaries.

Biodiversity (biological diversity) relates to the diversity of genes, species, habitats (ecosystems) and landscapes [2]. As will be discussed in more detail in Section 3, there are numerous linkages between the FE and biodiversity loss and conservation. The DPSIR framework emphasizes the drivers, pressures, state changes, and impacts with the responses (or non-responses) of policies or strategies. While FE strategies can provide responses in regard to each element of the DPSIR framework, it should be noted that connections between the FE and biodiversity conservation are rather abstract. To date, there are no specific FE policies to conserve genetic, species or ecosystem biodiversity. Rather, the material inputs and more stringent sustainability policies reduce the drivers of biodiversity loss in general and provide strategies to tackle pressures and impacts.

In regard to potential points of contact and overlapping policy goals between the biodiversity conservation frameworks described briefly in the introduction (CBD and the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) [8]) and the foundational economy, several GBF targets may be of particular interest [2]:

- -

- “Enhance green spaces and urban planning for human well-being and biodiversity”: Target 12 focuses, e.g., on biodiversity-inclusive urban planning.

- -

- “Integrate biodiversity in decision-making at every level” (target 14): The GBF explicitly addresses the consideration of biodiversity values in regulations, and in planning and development processes.

- -

- “Enable Sustainable Consumption Choices to Reduce Waste and Overconsumption”: Target 16 aims at a significant and equitable reduction of consumption, in order “for all people to live well with Mother Earth”.

Arguing about the role of the foundational economy for biodiversity conservation along the exemplary GBF targets and integrating it into an ecological–economic model (see Section 3) on the basis of ecosystem services is inevitably related to one’s understanding of the values of biodiversity.

Broadly speaking, the ‘ecological value’ and values of biodiversity (conservation) can be framed in at least two categories [41]. Originating from ecological research methods such as remote sensing, the concept of ecological value formerly developed for the natural sciences extended to social, economic and cultural sciences as well. In ecological research, the ecological value primarily addresses the instrumental value of one species (structure or process) benefiting other species and the ecosystem as a whole (i.e., biodiversity, resilience).

A large part of the economic valuation of biodiversity—and of ecosystem services as the most prominent approach also used in this paper—aims at ascertaining such instrumental values. Both use and non-use values of biodiversity conservation are used to assess the benefits and costs of changes in biodiversity (owing to management options), based on individuals’ preferences and utility functions (e.g., [42,43]). Intrinsic values play a role in valuation insofar as the existence of species or ecosystems contributes to altruistic or ethical arguments in the utility function. Humans may attribute both instrumental and intrinsic values to biodiversity conservation.

While the dichotomy of instrumental and intrinsic values has been debated in the scholarly literature for some time, Himes and Muraca [44] propose a different approach by discussing the concept of relation values. These values exemplify the relationship between humans and nature, thus supporting the notion that—in addition to the aforementioned dichotomy—human perspectives and relations and those of the whole human society must change to conserve biodiversity effectively within planetary boundaries. The IPBES (Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) recommends considering biodiversity in terms of instrumental, intrinsic and relational values to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the values of nature [45].

In regard to the focus of this paper, the embedding of the foundational economy (FE) in the different value conceptions of biodiversity conservation means that the FE can be connected to all three value dimensions (for a recent overview on methods and values, see [46]). However, connecting the FE with biodiversity conservation foremost rests on instrumental values. Intrinsic and relational values may be added and supported in the further development of FE strategies. Arguably, the FE provides the fundamental basis for thinking beyond instrumental values, and for including intrinsic and relational values as well. (For instance, secure and affordable satisfaction of everyday needs can increase one’s willingness to accept stricter conservation policies; see Section 3 and Section 4 below).

As will be shown in more detail below, first, biodiversity contributes instrumentally to several aims and objectives of the FE, e.g., by delivering crucial ecosystem services (provisioning, regulating, maintaining ES). Second, intrinsic values are specifically addressed in relation to biodiversity conservation and existence, and altruistic and bequest values, since the FE facilitates the appreciation of such values by producing (universal) basic services. Third, as the FE model can be considered an alternative socio-economic model (in a normative sense), it also provides the basis for a new relationship between society, economy and nature.

2.3. Embedding the Foundational Economy, and Potential Connections to Biodiversity Conservation

Table 1 presents an overview of the foundational economy embedded within a society’s economic and social structures, including the reproductive non-market sectors of the core economy. Taking the number of jobs and workloads (measured in hours worked in the paid and non-paid sectors), the foundational economy is estimated to account for between 40 and 60% of the whole economy [20,29,47]. The core economy of reproduction is often overlooked because it is unpaid and not recorded in the national accounts, thus leading to a structural imbalance [25]. As previously discussed, the foundational economy consists of utilities and infrastructure (technical, social) and the local provisioning of essential goods and services. Furthermore, Table 1 includes the sector of Nature’s contributions, as well as cultural goods and services. These essentially non-market sectors are summarized under the category of the paid sector of the economy, as both are managed within human institutional frameworks and are regularly managed with a focus on providing instrumental values. (Planning and managing biodiversity conservation involves major efforts in terms of setting aside protected areas, reducing large-scale emissions impacting biodiversity (e.g., nitrate emissions from agricultural production), and opportunity cost of growth-oriented economic development (see for forest conservation, e.g., [48,49])).

The non-essential segments of the local economy consist of economic activities that provide convenience and luxury goods and services.

Two further sectors of the economy are largely outside the foundational economy; one is the export-oriented industrial production of goods, such as machinery, cars, and chemicals. While these sectors may provide some basic infrastructure for the foundational economy, they are mostly devoted to the resource-consuming production of luxury or non-essential goods. (As the foundational satisfaction of basic goods and services also rests on industrial products, industrial policies have increasingly been discussed in connection with the FE model, and to planetary boundaries and the potential role such policies can play in connection with degrowth strategies [50]).

Finally, the extractive and rentier sectors of the economy consist of all activities that do not produce goods and services for everyday consumers, but instead focus on financial markets, financialization and (high-frequency) trading of resources [12]. In this conceptualization of the foundational economy, these sectors extract values (cf. [48]) rather than producing benefits for citizens in the sense of satisfying needs. Table 1 also refers to the spatial and temporal dimensions of the different economic sectors, as well as their relationship with social–ecological transformation.

The lower part of Table 1 describes potential connections to the conservation and restoration of biodiversity. Both supply- and demand-sided dimensions are included. On the supply side (production), several economic arguments can be put forward for the biodiversity-conserving properties of non-market and foundational economic activities.

First, the unpaid activities of the core economy (reproduction, family care, voluntary work) have a low environmental impact as they primarily consist of personal services and care work. Some of these activities directly improve ecological knowledge and lay the foundations for civic engagement; for example, environmental NGOs, community services and awareness-raising activities. It is not straightforward to assume that increasing the amount of unpaid work by reducing working hours is per se leading to a reduction in resource use. While resource use is closely connected to income, wealth and expenditure of households, a reduction in paid working hours will certainly lead to a reduction in resource use. However, leisure hours may also be used for resource-intensive activities [51], leading to well-known rebound effects [52].

Second, the sectors of (public) utilities and infrastructure, together with the local provisioning of essential goods and services, may lead to major environmental advantages compared to other forms of economic organization. Owing to economies of scale and scope, the production of goods and services is generally more resource-efficient (e.g., [53]). Examples include public water provision, public transport, education and healthcare. Furthermore, such activities are often standardized, regulated and monitored, leading to lower environmental impacts and efficient transaction costs.

Strengthening the foundational economy with a focus on need satisfaction is often considered beneficial for the environment. A comprehensive international quantitative study by Vogel et al. [13] (p. 1) found that dimensions of the foundational economy such as “public service quality, income equality, democracy, and electricity access are associated with higher need satisfaction and lower energy requirements”. Unlike extractive industries and growth-orientation, the foundational economy may generate economies of scale and scope in providing foundational goods and services, leading to significantly lower resource inputs than other economic models and branches. Thus, the foundational economy can tackle some of the most important ecological drivers of biodiversity loss [6,7], namely, habitat modification (through reduced land consumption and land sealing), overexploitation (decreased material throughput), and climate change (foundational infrastructures are less energy-intensive) (cf. [54]).

Local provisioning (e.g., food, repair services) is more likely to be organized within a (regional) circular economy using local and regional resources (e.g., [55]). The negative ecological impacts of local resource use are also immediately noticeable and may also lead to increased environmental awareness. FE production and provisioning may reduce resource use at the local and regional level, thus contributing to staying within planetary boundaries. As a reviewer for this paper rightly emphasized, the local and regional perspective might ignore global impacts and delays between biodiversity loss, thresholds, and reaching planetary boundaries. Thresholds might be exceeded long before planetary boundaries are overshot.

Social infrastructures are a crucial part of the foundational economy. However, while the provision of services itself is primarily based on human labor and is less resource-intensive than other branches of the economy on a per-service basis, many social infrastructures depend on a variety of technical/network infrastructures such as buildings, public spaces, energy and utilities [56]. Therefore, an extension of the foundational economy might not automatically lead to a reduction in resource use. The latter is a necessary but certainly not sufficient framework for the conservation and restoration of biodiversity (in relation to the circular economy, e.g., [57]). Nevertheless, the public provision of foundational goods and services reduces greenhouse gases (GHGs) and has proven to be more inclusive [40], making it potentially more biodiversity-friendly.

As discussed above, reducing the use of resources per service unit (efficiency) is a necessary but not sufficient strategy for conserving biodiversity. While reducing resource use addresses key drivers of biodiversity loss (e.g., land use change, resource extraction; [58,59]), two additional dimensions have to be considered. On the one hand, the complexity of ecological systems must be acknowledged (see, e.g., Goldenberg et al. [60]), who study climate change, ocean acidification and ecological impacts). On the other hand, beneficial impacts on biodiversity conservation through the reduction in resources depend on the types and the quantity of resources, how these resources are utilized, and on the location of resource extraction. For instance, biodiversity, land and resources can be embedded in imported goods and services. This can potentially increase global threats to biodiversity conservation and SDGs, while decreasing local or national pressure on biodiversity [59,61,62]. Therefore, the local and regional reduction in resource extraction and use must be complemented by regulations preventing biodiversity leakage [63,64]. Pan et al. [65] provide recent evidence that carbon leakage owing to land use changes that particularly affect biodiversity is a substantial problem for global ecosystems. Biodiversity leakage thus points to a further limitation of merely local or regional FE strategies: Even if alternative socio-economic models are implemented in local contexts, imports (and exports) and the embodied natural resources have to be regulated on an international level (e.g., by new industrial policies, see [50]).

Third, Nature’s contributions to people, and cultural goods and services increase environmental awareness. Some of these activities directly ‘produce’ biodiversity conservation and restoration. For example, protected areas and public spaces for recreation promote conservation and restoration and are also important for social equality [66]. Furthermore, including these “sectors” of the economy also makes the different values of biodiversity conservation (instrumental, intrinsic, relational; see Section 2.2) more explicit. In regard to land consumption, it has to be stressed that the trade-offs between conservation in protected areas, land for FE infrastructures, organic agriculture and renewable energy production is by far not settled, and that FE strategies must be careful in extending land use at the cost of nature conservation. Some trade-offs and conflicts are discussed in more detail in Section 3 in the DPSIR framework (Figure 2).

The non-essential (local) provisioning, fourthly, may also bear advantages for biodiversity conservation as energy and material flows could be more easily organized in a circular manner. The local regulation and planning of land and resource use could also contribute to efficient and effective conservation.

Two sectors well-known for causing major environmental harm are the export-oriented production sector and the financial sector. Most economic activities of the industrial sector, such as manufacturing cars, airplanes, chemicals, machinery, metals, and steel, are highly resource-intensive and often produce luxury or convenience goods. In addition, the use of these goods is often energy-intensive (e.g., air travel) and contributes to greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) that directly impact biodiversity. The construction and use of fossil infrastructure (e.g., airports, fossil power plants, oil rigs and pipelines, highways) is regularly connected to habitat loss and fragmentation [67]. Finally, the financial sector is oftentimes closely related to environmental harm through financing unsustainable economic activities [68]. Financial products and services can significantly increase GHG emissions [69]. The foundational economy as a conceptual basis for social–ecological transformation is inherently about shifting power away from extractive sectors of the economy. As Schaffartzik et al. [70] demonstrate, capitalist power, in the form of financial and economic assets, is primarily exerted through ownership and control over material resources. This occurs, for instance, by identifying the most profitable investments given the material stock, and by strategically influencing market and regulatory frameworks (e.g., by research and development, pressure on suppliers and customers, and through lobbying and regulatory capture), and by allocating profits, funds, and deciding on new material structures (cf. [71]).

On the demand side, the sectors of the core economy, the foundational economy and local provisioning sectors all provide citizens with basic goods and services. A stable and high-quality satisfaction of basic needs has been shown to correlate with the willingness to allocate (some) income and resources for environmental policies, including biodiversity conservation and restoration [72].

Public welfare policies increase trust in governments and public institutions (e.g., [73]). Welfare state policies also encourage postmaterialist thinking in citizens, who may then be more open to environmental policies [74]. Increased social capital, such as social trust and a sense of community belonging, enhances environmental behavior [75]. Caring for the environment and accepting environmental policy instruments, such as environmental taxes, are also closely connected to political trust, social security, and protection [76,77]. Studies even show that social security can lead to a higher willingness to sacrifice material consumption [78]. Respondents in social–democratic countries with well-developed welfare systems exhibited a higher willingness to accept reductions in their standard of living in order to protect the environment [79,80]. In addition, studies also show that economic insecurity and poverty are key obstacles to pro-environmental behavior and acceptance of environmental policies [81,82].

2.4. Foundational Economy and Environmental Improvements

In the context of industrial policies, Schroeder [83] emphasizes the role and importance of the foundational economy, including universal basic services, for a social–ecological transition. The author puts human needs that need to be fulfilled by the foundational economy at the center of her discussion by arguing that such a transition would be based on a different model of economic decision-making. However, as extractive and polluting industries might shrink, and the foundational economy (e.g., health, care, education) might expand, transition phases may be prone to instability. The author uses the example of combatting climate change to illustrate her point, but the same reasoning applies for biodiversity conservation.

Degrowth, sufficiency, and transition strategies are often associated with a reduction in the economy’s material throughput, which could potentially be beneficial for biodiversity conservation. However, this reduction in material flows may be correlated with a decrease in GDP and income, at least during the transition phase. This could also lead to the increased vulnerability of livelihoods and social insecurity. Solutions for stabilizing incomes include elements of the foundational economy, such as universal basic services, and job/income guarantees [72].

It is widely accepted that biodiversity conservation strategies and policies must be embedded in local and regional contexts to achieve both effective ecological outcomes and benefit-sharing for local stakeholders. Armitage et al. [84], for instance, develop five central principles of local governance frameworks for effectively conserving biodiversity. One central aspect is the consideration of well-being and strengthening of local institutions, including socio-economic development and overcoming barriers for a transformative change. The foundational economy is hypothesized to reduce or dampen the negative effects of urban growth and sprawl on the well-being of residents, in contrast to private companies, which can lead to a larger path dependence [85].

In regard to the materiality and the large resource inputs into infrastructure systems, Bahers and Rutherford [86] discuss the circular economy concept in light of the local foundational economy. They argue that the concept of circularity (e.g., reuse, recycle) is still embedded in a growth strategy that ignores the contradictions between sustainability and planetary boundaries, and the ever-growing resource flows (see, e.g., [87,88]). The foundational economy, of course, is based on a large variety of technical and social infrastructure. Even in a circular economy, the resource use should not be underestimated as building infrastructures is amongst the most resource-consuming economic activities [57,89]. Cong and Thomsen [55] discuss the potential policy strategies for implementing a bio-based local circular economy (BCE) and the ecosystem services connected to BCE. Their comprehensive literature review shows that the BCE focuses on minimizing emissions, but not on sufficiency and the size of the economy in relation to planetary boundaries.

The expansion of foundational infrastructures is often considered a contribution to overcoming the carbon lock-in [90,91]. However, there is a debate over whether decarbonization can already support a socio-ecological transformation and thus challenge the basic frameworks of the capitalist market economy [92].

As a transformative concept, the foundational economy might also lead to a double decoupling [93]. On the one hand, of the satisfaction of human needs from the amount of energy and resources used, and on the other hand, of the amount of energy used from the energy provisioning system. However, as a recent debate in the journal Planning Theory highlights [94,95,96], the foundational economy is not a degrowth project from the onset. Since it only describes in its humble form different sectors and logics of the economy, it becomes a transformative concept only when planetary boundaries, including biodiversity indicators and thresholds, are integrated as the very basis of economic activities. As has been acknowledged earlier, it must be noted that some of these perspectives are debated from a European standpoint; non-European views are often underrepresented. Thus, allocating available resources according to human needs within planetary boundaries is a (normative) degrowth agenda because it includes values of sustainability and social justice. Biodiversity conservation and restoration, as argued above, is built into the FE approach as extractive economic branches and activities (e.g., financialization, speculation) are ultimately assessed as unsustainable. (The financialization of biodiversity itself has gained attraction in recent years despite evidence of potential counterproductive effects (e.g., [61,90]).

Land, resources, and net primary production are, therefore, conserved further by developing the FE concept. This places strategic planning in an active position in the social–ecological transformation. Planning should, according to [96], leave the path of pragmatic policies and instruments—thus supporting economic growth—and instead strengthen all existing strategies and develop new ones for degrowth, especially at the local and regional levels.

Recently, the foundational economy concept has been introduced to the discourse on energy communities that aim at producing local renewable energy in joint, often not-for-profit associations. Bonfert [97] discusses these local energy initiatives in the context of the foundational economy by differentiating between the ‘FE 1.0 and 2.0’. Earlier concepts of the FE focused on describing the everyday economy mostly in terms of satisfying basic (everyday) human needs. The more advanced debate adds an ecological dimension to the concept by explicitly referring to the potential negative consequences of human need satisfaction and to the planetary boundaries [98].

A functioning and comprehensive foundational economy provides the necessary opportunities for leisure and recreation. While recreation in green spaces might be assessed in terms of reproduction (supply side), the FE also facilitates the use of green spaces for one’s own enjoyment (demand side). The quality, quantity and distance of attractive green public spaces (streetscapes, parks) are important contributors to well-being and human health (e.g., [99]).

In the context of the foundational economy, the debate around Universal Basic Services (UBS) emerged as a specific allocation and provision strategy. UBS may be considered as a part of the FE with a special focus on free and equal access. As Büchs [100] points out, UBS has many advantages over alternative (sometimes complementary) strategies such as the Universal Basic Income (UBI). Coote [101] also places UBS at the center of the needs-based provision of essential goods and services while combining UBS with an income guarantee (a variant of UBI). However, in comparison to UBI, UBS can contribute to sufficiency and production/consumption corridors [26]. It can also provide much more scope for designing policies, such as those for not-for-profit associations embedded in democratic governance [102]. UBI as a transformative strategy is often considered insufficient, as more radical structural interventions would be needed, such as universal basic services or foundational infrastructures [103]. However, UBS may also have shortcomings in terms of the lack of considering individual preferences, and central planning ignoring local specificities [100].

Coenen and Morgan [104] contextualize the foundational economy within a framework of local (place-based) innovation. Innovations in the realm of the FE may be technical but primarily include social innovations and new forms of co-governance (cf. [105]). The authors conclude that the FE challenges traditional public-sector, local and welfare policies by experimenting with new approaches to the management, provision, regulation and funding of public goods and services. However, the foundational economy is not merely a framework that enhances innovations for social–ecological transformation; rather, it requires specific frameworks to lead to innovations that enhance and support the well-being of local people instead of working for the international consumer goods markets. This could also help in developing the societal and economic systems within planetary boundaries [106].

Rainnie [107] stresses that the production of foundational goods and services has been “undermined by privatization and outsourcing, and financialization”. Plank [108] suggests that new forms of public ownership, which are not necessarily public enterprises owned by the central government, are an important approach to the foundational economy as a transformative socio-economic model (see also Section 4 below). New public and private forms of enterprises at different levels of government, such as not-for-profit housing cooperatives, are needed to reduce extractive business models. For instance, resource consumption for housing can be reduced by mandating that not-for-profit housing cooperatives reduce the energy consumption of apartments. This has led to higher energy standards for subsidized houses, such as the ones provided by the City of Vienna (Austria), compared to privately financed houses. In addition, housing subsidies are tied to the maximum size of rental apartments (and maximum household income), which is certainly an example of sufficiency policies in the foundational economy (e.g., [108]).

3. The Foundational Economy and Biodiversity: An Ecological–Economic Conceptualization

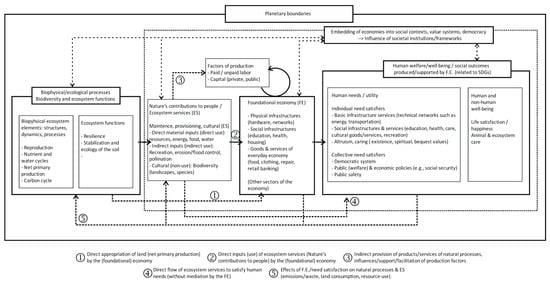

Figure 1 presents a conceptual ecological–economic model embedding the foundational economy (FE) into direct and indirect flows of natural resources (ecological/ecosystem goods and services) relevant to biodiversity. (The model described in this paper is a condensed and simplified picture of the complex relationships within and between ecosystems, and their elements and functions, to derive a conceptual underpinning of the linkages between the environment and the economy, in particular, FE. Detailed pictures of these relations, ecological complexity, and ecosystem characteristics such as resilience are as described in, e.g., [109,110,111,112].)

On the left side of the figure, the ecological processes and functions are sketched. These ecosystem functions, such as resilience, water retention, and the stabilization of the soil, are based on biophysical processes and elements of the ecological system, for instance, single species, structures, connections, and resource inflows and outflows. Furthermore, reproduction, water, nutrients and carbon cycles, and (net) primary production are important underlying ecological processes. Thus, biodiversity is first considered in its instrumental values for developing this model (as ecosystem service). However, the various connections between biodiversity and FE elements, and feedback loops, also include intrinsic and relational values.

Ecosystem functions, based on fundamental biophysical processes, determine ecosystem services (ES) (e.g., [109]), or Nature’s contributions to people [113]. Categories include the well-known maintenance, provision, and cultural ecosystem services. The foundational economy provides the basic goods and services of general interest in the form of goods and services of technical and social infrastructures. (Other sectors of the economy, such as other consumer goods, or goods and services traded on (international) markets, are not displayed in this figure).

FE goods and services contribute to the satisfaction of individual and collective needs, such as education or health services, public welfare policies, and safety. These lead to human and non-human well-being, including life satisfaction, happiness, or animal welfare.

This simplified model also illustrates the connections between the foundational economy and biodiversity. Generally, FE—as all economic activities are based on biophysical processes—rests on the different ecosystem services described above. However, as will be described here and in Figure 2 below, the FE supports the conservation of biodiversity and ES, as well as also having limitations in doing so.

First, biophysical processes are directly used or related to FE goods and services (①). Since the foundational economy is based on land use, such as the carrying function of the soil for infrastructures, it appropriates the (net) primary production of existing (soil) ecosystems, which can impact biodiversity conservation. In this sense, land is a direct factor of production and is thus directly linked to FE goods and services.

Second, the foundational economy uses numerous ecosystem services (ES) and Nature’s contributions to people (NCP) as raw materials or inputs (②) to produce FE goods and services. All ES are produced by biophysical processes and enhanced and secured by biodiversity. For instance, biodiversity contributes to a more resilient food system (provisioning ES; direct use), more robust maintenance ES (flood and erosion control; indirect use), and higher values of cultural ES in the sense of non-use values of biodiversity (e.g., [114]).

Third, ES also contribute to the provision of factors of production for the foundational economy such as labor (both paid and unpaid), as well as all forms of capital (③).

Fourth, biodiversity (and related ESs) may directly contribute to the satisfaction of human needs (④), for instance, by spiritual values as part of intrinsic and relational values of biodiversity.

Finally, it is important to note that the foundational economy—like any other economic consumption and production activity—has repercussions on the ecological system (⑤). Biodiversity thus not only provides the basis for FE goods and services provision but is also affected through the use of resources as well as by the emission of pollutants, waste generation, and land use changes (e.g., owing to resource use, such as mining for infrastructures).

Figure 1 also acknowledges the fundamental importance of societal and economic institutions and frameworks that regulate and influence both natural and economic/social processes.

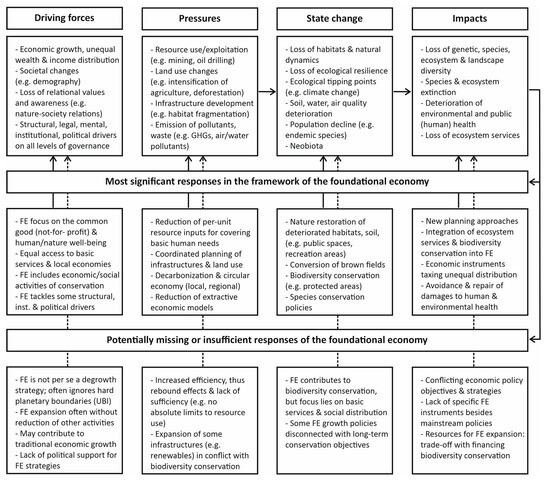

Figure 2 highlights the most important elements of the DPSIR (drivers, pressures, state changes, impacts, responses) framework in regard to the potential responses (and non-responses) of the foundational economy to the biodiversity crisis.

Drivers of biodiversity loss such as economic growth, societal changes, and various institutional or political drivers on all levels of governance could be mitigated by the general economic policy approach of the FE in regard to focusing on basic human needs and common-good business models (e.g., not-for-profit; see Section 4 below for more details). By including equality and non-market provision, and fundamentally orienting economic policies towards sustainability, the FE can reduce some of the driving forces of biodiversity loss. However, a distinction between the elements of biodiversity (genetic to landscape diversity) is not feasible at this level of aggregation. Nevertheless, there are shortcomings because the FE is not a degrowth strategy per se as economic growth is not fundamentally turned away. Some FE elements, such as UBI (universal basic income), have problems in considering planetary boundaries.

Pressures such as resource use, exploitation, or unsustainable land use change are the direct consequences of the drivers mentioned above. The FE can reduce some of the pressures by reducing resource use per unit of output (foundational goods or services) owing to the above-mentioned economies of scale, scope, and density, and by reducing transaction costs and extractive economic activities. However, without a fundamental change, such as pursuing a social–ecological transformation (e.g., upper limits of resource use), increasing resource efficiency may result in increased economic growth (Jevon’s paradox, rebound effects). In addition, extending foundational infrastructures may be resource-intensive, and thus increase pressures on biodiversity. While pressures on all elements of biodiversity may be reduced by FE policies, land use and resource extraction mostly refer to species, ecosystem and landscape biodiversity.

Changes in the state of the environment, such as the loss of habitats, ecological tipping points, population decline and soil or water quality deterioration, may be mitigated by single FE activities. For instance, the FE includes—in the conceptualization developed in this paper—economic activities that specifically restore habitats and public spaces, re-develop brown fields, and re-introduce once-endemic species. These activities are mainly related to instrumental values of biodiversity, such as recreational or health-related benefits. Some FE policies, such as funding the extension of infrastructure, may conflict with the resources needed for biodiversity conservation.

Figure 1.

The foundational economy in an ecological–economic model (source: own concept and draft, building on works from [43,115,116,117]).

Figure 2.

The foundational economy and the DPSIR framework: potential responses and non-responses of the FE to the biodiversity crisis (source: own concept and draft).

Finally, the impacts of these developments, such as the loss of certain species, ecosystems or ecosystem services, can be mitigated by FE policies, such as new local policy instruments, or investing in repair (e.g., restoration) or avoidance of damages. However, some impacts may merely be ignored by the FE as the foundational economy does not provide specific instruments or resources that particularly focus on these impacts.

Summing up, there might be some trade-offs between the FE and biodiversity conservation if accompanying and complementing strategies are not pursued. Examples of such trade-offs and complementing strategies include

- -

- Essential local provisioning systems (see Table 1): Food systems are an essential part of the foundational economy [38]. However, designing food systems sustainably towards organic and local/regional agriculture may require the extension of areas for agriculture and could potentially conflict with biological conservation. Thus, such a transformation would not only change production systems but also make it necessary to alter consumption patterns, e.g., changing dietary habits [118,119,120]. FE models thus need complementary policies such as greening food systems and decarbonizing production to be effective in reducing the pressures on biodiversity.

- -

- Public infrastructures: For a sustainable mobility system, the FE would consider the improvement and expansion of public transport and bicycling infrastructure, some of which would need more resources and increase pressures on biodiversity (e.g., extension of rail networks). However, changing travel behaviors of households and shifting to green mobility also requires the reduction in private car use by means of sustainable transport policies, such as the reduction in environmentally counterproductive subsidies, taxing carbon emissions from private car use, electrification and reducing the capacities of public roads for car use (e.g., [121]).

4. FE Strategies Supporting Biodiversity Conservation

Based on the discourse of this paper thus far, FE strategies may be summed up in the following key points. As Refs. [29,102] have discussed, these strategies may include policies that facilitate a social–ecological just transition, which is deemed necessary for biodiversity conservation, climate neutrality, and equity/justice (for more information, see [20]). While these basic strategies are prerequisites for the FE per se, the following arguments connect these to biodiversity conservation:

- Managing the socio-ecological transformation, including biodiversity conservation and restoration, requires good basic (foundational) services for all. This implies an expansion of public services of general interest based on “social rights” to satisfy human needs (cf. [40]). The FE is considered more resource-efficient and environmentally friendly on both the supply (production) and the demand side, compared to other economic models of provisioning (see the discussion in Section 2 in reference to Table 1). These effects of the FE directly reduce pressures on biodiversity.

- Expanding (public) services of general interest requires integrated, socially just, and ecologically sustainable approaches to minimize resource consumption and respect planetary boundaries, especially in regard to biodiversity conservation and restoration, and climate protection. A secure provision of everyday services has been shown to increase the willingness to devote resources to environmental causes, such as biodiversity conservation.

- The responsibility of the public sector (state, planning) and a focus on the common good and the public interest (i.e., not-for-profit/limited-profit) are fundamental prerequisites for future-oriented public services. This includes the remunicipalization of foundational services (see [118,122]) that are currently commodified or financialized (e.g., in the healthcare, care, housing sectors). Biodiversity conservation can be enhanced by reducing pressures and increasing resources for dealing with the impacts of biodiversity loss through reducing extractive business models and improving public planning.

- The expansion of public services of general interest should go hand-in-hand with democratizing them, and be accompanied by greater participation, more opportunities for co-creation, and co-design. Greater public responsibility for expanding services of general interest requires effective, formative public planning, which can increase citizens’ trust in public institutions and consequently, in environmental policies.

- The expansion and strengthening of the public interest/not-for-profit orientation of the foundational economy must also be anchored in international market and trade arrangements, such as the European Union (EU) regulatory (single market) frameworks.

The fundamental strategies discussed here, of course, are not necessarily focused on biodiversity conservation or renaturation. However, the foundational economy by itself rests on these strategies, and may only fulfill the promises outlined in this paper if these economic policies are implemented. For instance, the significance of not-for-profit provisioning of basic goods and services precludes extractive business models and thus lowers the ecological footprint. Given the DPSIR framework discussed above, this alone could contribute to a reduction in drivers and pressures on ecosystems and biodiversity. Furthermore, a democratic and coordinated public planning approach may be more efficient (and socially just) in providing essential infrastructure, thus reducing the ecological footprint as well.

These policy strategies may certainly conflict with some mainstream proposals and strategies in favor of marketization, commodification and private involvement in the provision of foundational goods and services. However, numerous studies have shown that the privatization of fundamental infrastructures oftentimes leads to lower service quality and higher prices, owing to insufficient regulation and monitoring frameworks and extractive business models of corporate investors [123].

5. Discussion, Summary, and Conclusions: Is the FE Biodiversity-Enhancing?

International studies on the lower and upper thresholds of resource use for human need satisfaction (production and consumption corridors; e.g., [26]) provide estimates of material requirements within planetary boundaries. For instance, the annual energy requirements for adequately meeting human needs were estimated at 13–18 GJ p.c., a level that could be provided sustainably through equitable, sufficient, technically efficient and largely collective provisioning [124]. However, as Vogel et al. [13] wrote, beneficial provisioning within the framework of the foundational economy—characterized by public service quality, high income equality, and low extractivism—is not necessarily linked to low energy use within planetary boundaries. There is no ‘natural’ process or mechanism that reduces energy consumption on its own when social provisioning systems are in place. Planetary limits can only be observed if these systems are combined with frameworks limiting the use of resources (energy, land).

Nevertheless, this paper has discussed some important economic arguments for why the foundational economy could be a cornerstone of biodiversity conservation and restoration. This conceptual model developed here meets the paper’s objectives discussed in the introduction by (1) identifying the ecological and economic connections of the FE, (2) embedding the FE within sustainability transitions, and (3) outlining potential policy frameworks to support biodiversity conservation. On the supply (production) side, FE production of goods and services benefits from substantial economies of scale, scope and density. These effects might increase resource efficiency by themselves. In addition, the reduction in transaction costs through public planning and regulation of foundational services (e.g., through standardization and guarantees for high-quality basic services) reduces the use of resources and environmental impacts, such as biodiversity loss.

Foundational infrastructures also require environmental resources and ecosystem services as inputs for production. Biodiversity can function both as direct inputs for production, and indirectly by safeguarding ecosystem resilience. However, biodiversity is also affected by FE production, owing to land consumption and material resource use.

Furthermore, FE production affects biodiversity, owing to the economic activities taking place on the basis of foundational infrastructure. Many FE activities involve personal services (care, education, voluntary engagement), which require minimal material and environmental inputs. However, we must bear in mind that many FE activities need technical infrastructure (e.g., buildings, energy, transportation) to function properly, such as health services. This paper’s hypothesis is that organizing such services within the framework of the foundational economy is more resource-efficient than other forms of provisioning. Increasing efficiency is generally a necessary, but by no means sufficient, strategy to achieve an overall reduction in resource inputs. Thus, biodiversity conservation may be supported by FE production. Sufficiency and degrowth frameworks that limit environmental impacts and accept planetary boundaries could eliminate the rebound and growth effects of efficiency improvements.

On the demand side, this paper argues that a secure and high-quality provision of foundational goods and services is a prerequisite for the acceptance of social–ecological transformation. Studies have shown that trust in public institutions and secure livelihoods are paramount to citizens’ appreciation of environmental and economic change. Higher acceptance of transition pathways is closely connected to secure, free access to FE goods and services (such as universal basic services, UBS).

One limitation of this study is that this paper conceptualizes the foundational economy as a cornerstone of biodiversity conservation—an approach which deems the FE a necessary but not sufficient strategy. The FE model establishes environmental, economic and social advantages (e.g., less resource use than mainstream economic models), leading to improved biodiversity conservation. However, the model does not detail potential strategies, instruments, frameworks, or specific conditions for biodiversity conservation and restoration.

The conceptual model also highlights the importance of embedding the foundational economy in an ecological–economic stock-flow model. Like many papers dealing with degrowth discourses, though, these approaches present a major scholarly challenge. While conceptual discussions are important, future research should empirically study the linkages between foundational economic concepts, sustainable development, and planetary boundaries, including biodiversity loss and conservation. To date, the foundational economy has only been conceptualized and theorized as the strategic bridge between the social and economic provisioning of UBS, as well as sustainability, sufficiency, and degrowth. Thus, this debate must be supported by more empirical evidence on the material resources necessary for a decent life, and the economic advantages and benefits of FE strategies. In summary, this is considered the main challenge of FE research in the years to come.

Funding

Parts of this research were conducted over the course of the project “MountResilience—Accelerating transformative climate adaptation for higher resilience in European mountain regions”, funded by the European Commission in the Horizon Europe Programme under Grant Number 10111287.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [TU Wien Repositum] at [https://doi.org/10.34726/7859].

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank L. Plank, E. Dowling, R. Bärnthaler, A. Krisch, A. Novy, A. Strickner, C. v. d. Laag, and discussants at the CROSS REIS workshop (Oslo 2024), the ISEE and NOBEL X conferences (both in Oslo 2025). Three anonymous reviewers provided numerous, very helpful suggestions for substantial improvements to the paper. All remaining errors are, of course, the responsibility of the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPBES; Brondizio, E.; Diaz, S.; Settele, J.; Ngo, H.T. (Eds.) Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Version 1; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBD. Convention on Biological Diversity; Secretariat for the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)/United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perrings, C.; Naeem, S.; Ahrestani, F.S.; E Bunker, D.; Burkill, P.; Canziani, G.; Elmqvist, T.; Fuhrman, J.A.; Jaksic, F.M.; Kawabata, Z.; et al. Ecosystem services, targets, and indicators for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchart, S.H.M.; Walpole, M.; Collen, B.; Van Strien, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Almond, R.E.A.; Baillie, J.E.M.; Bomhard, B.; Brown, C.; Bruno, J.; et al. Global Biodiversity: Indicators of Recent Declines. Science 2010, 328, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, A.; Idrisova, A. Convention on Biological Diversity: A review of national challenges and opportunities for implementation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 3295–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, M.; Sinkko, T.; Caldeira, C.; Tosches, D.; Robuchon, M.; Sala, S. Critical review of methods and models for biodiversity impact assessment and their applicability in the LCA context. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Borsky, S.; Braun, M.; Eitzinger, J.; Gaube, V.; Getzner, M.; Glatzel, S.; Gschwantner, T.; Kirchner, M.; et al. Past and future impacts of land-use changes on ecosystem services in Austria. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBD. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework; Secretariat for the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD): Montreal, QC, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Boran, I.; Pettorelli, N. The Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Paris Agreement need a joint work programme for climate, nature and people. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 61, 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.C.; Grumbine, R.E. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework: What it does and does not do, and how to improve it. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1281536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obura, D. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework: Business as usual or a turning point? One Earth 2023, 6, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, A.L.; O’Neill, D.W.; Büchs, M. Provisioning systems for a good life within planetary boundaries. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 64, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.; Steinberger, J.K.; O’NEill, D.W.; Lamb, W.F.; Krishnakumar, J. Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use: An international analysis of social provisioning. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 69, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Communities. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1992, 206, 50. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:1992:206:FULL (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- European Union. Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, 20. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2010:020:FULL (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Jones-Walters, L.; Čivić, K. European protected areas: Past, present and future. J. Nat. Conserv. 2013, 21, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowska, E.H.; Roberge, J.-M.; Blicharska, M.; Mikusiński, G. Gaps in ecological research on the world’s largest internationally coordinated network of protected areas: A review of Natura 2000. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 200, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaccio, A.; Campagnaro, T.; Sitzia, T. Birds and Natura 2000: A review of the scientific literature. Bird Conserv. Int. 2022, 33, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on nature restoration and amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401991 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- The Foundational Economy Collective. Foundational Economy: The Infrastructure of Everyday Life; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Competence Centre for Infrastructure Economics, Public Services and Social Provisioning. About The Economy We Need Every Day; Competence Centre for Infrastructure Economics, Public Services and Social Provisioning: Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://en.alltagsoekonomie.at/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Bärnthaler, R.; Novy, A.; Plank, L. The Foundational Economy as a Cornerstone for a Social–Ecological Transformation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]