Abstract

This study examines the impact of sustainability “big data” analytics on “product innovation” in Jordanian pharmaceutical companies, focusing on the mediating roles of “knowledge management capabilities” and “agile supply chain” management. Using structural equation modelling with data from 381 pharmaceutical managers, we tested eight hypotheses relating to direct and indirect relationships between these constructs. The findings revealed that big data has a significant positive direct effect on “sustainability product innovation” (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), accounting for 46.3% of the total effect. “Knowledge management” and “agile supply” chain were found to mediate this relationship, contributing (31.3% and 22.4%) of the total effect, respectively. Our supplementary analysis demonstrated that big data has a notably stronger impact on radical innovation compared to incremental innovation (36.3% stronger effect). The model demonstrated robust explanatory power, accounting for (43.5%) of the variance in product innovation, (37.2%) in knowledge management, and (45.1%) in agile supply chain. All measurement scales showed strong psychometric properties with factor loadings exceeding 0.75 and composite reliability values ranging from 0.889 to 0.932. These findings expand our understanding of how “sustainability big data” fosters pharmaceutical innovation and offer pragmatic insights for managers seeking to leverage data capabilities for a competitive advantage in the pharmaceutical industry of Jordan.

1. Introduction

A safe, effective, and affordable quality of medicines is instrumental in promoting the right to health, with prevention and treatment incorporated, which form indispensable elements of the development agenda worldwide [1]. The Jordanian pharmaceutical industry has established a prominent reputation and added significant value on local and international levels. It is and always will be an engine of the economy, a collaborator with previous work in creating prosperity and advancement of the country moving forward. This sector contributes substantially to the GDP and represents a significant portion of total exports for the country [2]. Jordan has done well across all levels and sectors, including the industry. These improvements have been made possible by virtue of incentives that encourage investment and promote Jordan, facilitating a favourable investment climate, security, and stability [3].

The entrepreneurial orientation of the Jordanian pharmaceutical industry is transitioning towards continuous technological changes. These changes pose a number of challenges for the institutions, reduced ability (a) to innovate and create new services/products that cater to client demands, (b) to adapt themselves to market dynamics, and (c) to undertake risk when accessing new markets. In order to stay competitive with established market leaders, start-ups have been forced to redefine their business models [4]. Pharmaceutical companies need sustainability and development, and more attention should be placed on patent issues to improve their innovation abilities and to face the challenges of global competition [5]. As the pandemic persists, the sector has become increasingly crucial, particularly in developing countries. Stable health is an important issue in a turmoil of emerging viruses and epidemics worldwide. Drug production firms need to be innovative and progressive.

The era of the big data economy has arrived, and big data analytics (BD) is considered the new oil of the 21st century. To encompass sustainability, big data has become vital for companies operating in the pharmaceutical industry to stay ahead of the competition and to understand trends, patterns, and behaviours in healthcare systems [6]. The purpose of this research is to investigate the influence of the sustainability of big data analytics on product innovation in Jordanian pharmaceutical organisations, with the mediating role of knowledge management efficiencies and agile supply chain practices. The importance of this research is not only attributed to its novelty in context (i.e., the Jordanian pharmaceutical industry) but also to the gap identified in the theoretical literature, which is dominantly concerned with firm-level organisational innovation and performance [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Without regard to mediating variables (such as knowledge management competency and agile supply chain practices) alongside the dependent variable (such as product innovation), we assert that the study objectives can be articulated as follows:

- The study aims to evaluate the current use of the sustainability of big data analytics for sustainability product innovation in the Jordanian pharmaceutical industry.

- This study analyses how agile supply chain exchange mediates the relationship between “sustainability of big data analytics” and “product innovation.”

- This study analyses how knowledge management exchange mediates the relationship between “sustainability of big data” and “product innovation.”

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Sustainability of “Big Data Analytics” and Product Innovation

Dynamic Capability Theory (DCT) offers a strong theoretical energy with which accounts for the impact of BDA on product innovation in environments characterised by high-speed change. Recent empirical studies indicate that BDAC enhances the capacity of firms to sense, seize, and reconfigure [12,13], enabling them to identify new opportunities, explore innovative options, and facilitate resource reallocation more effectively. These are the dynamic capabilities that let companies quickly come up with and carry out new product ideas, with quick validation based on real-time business intelligence. Moreover, new studies indicate that BDAC fosters ambidextrous innovation (i.e., exploration and exploitation), which is an important mechanism by which big data influences innovation outcomes [14,15]. Moreover, organisations that develop a strong innovation culture are more able to employ BDAC for process reformation and maintain continuous innovation so as to strengthen the dynamic capabilities path from big data to successful product development [16]. Consequently, big data analytics is defined by the substantial volume of data that requires processing, analysis, and storage. Big data analytics (BDA) encompasses extensive, intricate, and varied analyses that necessitate effective and creative information technology solutions for enhanced insights and improved decision-making [17].

The sustainability of big data analytics derived from consumer blogs enhances the capacity for informed corporate decision-making, suggesting that, relative to other organisational attributes (such as corporate culture), data-driven decision-making could elevate firm productivity by as much as 5% [18]. Three essential success criteria have been identified for leveraging big data in innovation: consumer engagement, a pioneering ecology, and accelerated innovation processes. These features indicate a paradigm shift that enables companies to substantially reduce the time and cost associated with new product development [19].

Knowledge of big data for competition in modern enterprises increasingly fosters innovation in products and services [20]. Big data enhances the innovative capabilities of businesses in various ways [21,22,23]. It has been ascertained that pharmaceutical corporations might reduce the time required to introduce new treatments by three to five years with the application of big data predictive modelling [21]. Due to big data, the achieved improvements in process over three years may show up to a 26% increase in productivity [24].

However, using big data to enable rapid innovation is a relatively new subject, and there is very little literature on this topic currently. In order to reveal these success factors, building on emerging product innovation development-related research and on industry expert insights is required. In large-scale data collection projects with a need for better product, consumer, and market insight, the traditional performance metrics are often poor-performing or even sub-optimal [21,25]. According to previous research, the following hypothesis is suggested.

H1.

There is a positive correlation between the sustainability of “big data” analytics and sustainable product innovation.

2.2. Mediating Role of Agile Supply Chain

Recognised components of supply chain resilience include market sensitivity, process integration, and collaborative planning [26], as well as demand responsiveness [27]. Additionally, awareness, data accessibility, speed, and flexibility are also key elements [28]. Supply chain agility is defined as a strategic capability or resource that enables organisations to quickly adapt their tactics and operations in response to changes in the external business environment [29].

Good supply chain management has been delivered in several fashions; facing challenges associated with this area and using the power of computing to be able to understand “big data” for businesses is the goal. Excellent degree of packaging process integration is also achieved with the aid of the web-centric applications and next-generation enterprise retail planning systems (NGERPs), software application services, and standard ERP or SCM products [30]. This integration is frequently fragmented, being limited only to bilateral cooperation or internal organisational processes [31].

The supply chain industry uses RFID, monitoring systems, and sensory equipment to gather a large amount of information [32]. Using this data through IT appliances such as business intelligence, analytics, and big data solutions [33], supply chain processes can be improved, costs minimised, and inventory management refined, which leads to increased profitability. Big data analytics has a great potential to influence different industries (marketing, logistics, production, and procurement) in the supply chain [34]. There are trend recognition and demand forecasting capabilities in big data through dynamic decision support.

Incorporation of big data technology in the supply chain increases its value in terms of operational excellence, reducing costs, satisfying customer needs and monitoring behaviour by providing real-time visibility, which ultimately closes the gap between demand and supply. However, the deep implementation of big data technology in the supply chain area is held back by its infancy, initial investments, and misunderstanding of how to apply it [35].

Firms are only now recognising the importance of agile supply chain management (ASCM) in producing new, value-added goods for end users because of increasing world comparisons and market shifts [36,37]. During the last two decades, it has been accepted that supply chain management (SCM) is a core competency, yet many firms still have trouble achieving a sustainable competitive advantage [38].

The debate about local supply chains and land-based operations thereby emerged into highlighting the important role of flexible manufacturing systems and effective supply chain operations to develop innovations [39]. Responsive supply chains are characterised by their ability to use safety inventories, compress lead times, respond quickly to unanticipated demand, and utilise modular designs to postpone product variety [40,41]. The latter capacities bring with them special challenges, particularly for innovative products, with their generally short lifecycles and often complex designs, as well as unpredictable demand [42,43].

Performance of efficient and responsive supply chains is facilitated by adaptive capabilities through which a firm can “stabilise” the uncertain environment and manage the output level to local demand [44,45,46]. ASCM supports organisations in the development and production of products that meet customer needs, and it does so by promoting teamwork, communication, and rapid problem solving [40]. However, there is still a lack of empirical research in this domain despite the theoretical focus on supply chain resilience benefits [47].

A supply chain agility maturity model focuses on flexibility, responsiveness, speed, efficacy, and visibility as key parts of resilience. Even though it provides a basis for measuring and improving supply chain resilience, the framework would benefit from being extended to also incorporate flexibility and creativity, especially in relation to product innovation [48]. This paper clarifies the significance of agile supply chain practices for firms to develop value-added products for end-customers. It studies the correlation between agile supply chains and product innovation. The framework aims to do so by making sense of how resilience drives innovation; thus, synthesising concepts from existing research and providing both scholarly and practitioner communities with novel insights.

H2.

The sustainability of “big data” analytics correlates positively with the agile supply chain.

H3.

An agile supply chain correlates positively with sustainable product innovation.

H4.

The agile supply chain plays a role in mediating the connection between the sustainability of “big data” analytics and product innovation.

2.3. Mediating Role of Knowledge Management Capabilities

Knowledge management, or KM, is essential to enhancing the effect of business development on company performance. It is commonly known that BDA and KM are interdependent because KM makes it easier to share business intelligence and expand human knowledge, which enhances performance in several ways [49]. Strong KM-oriented businesses are better able to handle and incorporate fresh information from BDA into their current body of knowledge, which amplifies the benefits of BDA for performance [50]. Knowledge management KM is defined as the systematic process of locating, organising, transferring, and exploiting knowledge and expertise [51]. Furthermore, businesses that have managed a variety of knowledge types in the past are often more creative and better able to utilise internal resources, such as BDA [52].

From a Knowledge-based View (KBV), knowledge management (KM) capabilities play a critical role in transforming sustainability-oriented big data analytics (BDA) into actionable insights that support product innovation [53,54]. BDA produces intensive, structured, and unstructured data, which can contribute to improving environmental and social performance if properly managed. Yet, the realisation of value from such capabilities is contingent on a firm’s capacity to access, assimilate, share, and utilise resources via knowledge management (KM), underscoring KM as a critical mediating dynamic capability between sustainable BDA and innovation outcomes [55,56].

Merging sustainability big data analytics (BDA) capabilities—managerial and technological dramatically leads to a better company performance [57], to provide new knowledge, and actionable insights that could enhance decision-making and competitive benefit. BDA is the practice of analysing huge and complex datasets [58]. Effective utilisation of BDA by businesses may generate extended lasting strategic rewards over time, such as a total reduction in client acquisition costs of 47% and an increase in revenue of just 8% [59]. On the one hand, the organised approach to management of (BDA) generated knowledge, and its integration in already existing organisational knowledge is required for addressing BDA, as underlined by [60]. BDA needs more than technological infrastructure.

In the context of BDA, skills have a positive effect on organisational performance (OP), and knowledge management (KM) plays an intervening role to further strengthen this relationship. With structural equation modelling as the method, an empirical study is implemented to validate the paradigm of these two dimensions of KM and BDA capabilities influencing corporate performance [56].

The combination of experience, creativity, risk-taking ability, and financial resources on the part of a company is the most important factor in developing new products and services during market entry, especially for early stages [61]. Innovation and knowledge are essential to the survival and success of a company because they both enable information to be translated into creative solutions, generating the production of new products [62,63]. Innovation is the utilisation of knowledge in production processes and systematic generation of new ideas through a variety of activities and technologies, thus being ingrained in the effective management of knowledge [64,65].

Knowledge management (KM) is crucial in order for organisations to create, execute, and maintain sustained competitive advantages by deploying useful information and sharing cooperative business techniques, leading finally to innovation [66]. However, it is the challenge of maintaining innovation that becomes even more difficult amidst changing consumer preferences and fierce market competition, in addition to rapid technological advances [67]. To meet these challenges, some firms (such as Hitachi and Xerox) have also entered into collaborations with external organisations to improve their creativity capacities [68]. These partnerships help the organisation to learn from external sources in order to support new thinking and operational approaches, becoming part of the firm’s practices for enterprising innovation [69].

The management of information within the innovation sphere includes identification, generation and application, communication, and storage of information [70,71]. These activities guarantee that organisations not only build capabilities, but they also attend to the culture, knowledge as an organisational asset for differentiation and competitiveness. The activities can be paramount by enabling innovation [72]. Through the use of intangible assets and mechanisms for transforming knowledge into value-added processes, firms can allocate resources to develop innovative products and services that provide a competitive advantage [73,74,75].

A variety of information and expertise is everywhere, which has an impact on product development, both positive and negative. The complexity and ambiguity of excessive information can be reduced by effective knowledge management, which will systematically collect and use the knowledge [76,77]. To accomplish effective and successful innovation results, organisations need to identify the type of expertise needed, how to acquire it, and the process for using it [77,78]. This is of particular importance for SMEs, as knowledge is considered a key resource for ensuring long-term competitiveness in the global market [79].

H5.

The sustainability of big data analytics (BDA) is positively associated knowledge management (KM).

H6.

Knowledge management capabilities (KM) are positively associated with sustainable product innovation.

H7.

(KM) capabilities moderate the relationship between (BDA) sustainability and sustainable product innovation.

2.4. Relation Between Knowledge Management and Agile Supply Chain

Agile and lean supply chains both have an equivalent level of importance, but the impact of KM processes on the SC performance is significant in the case of judging SC strategy under both scenarios, with relatively higher significance to agile supply chains [80].

The results show that knowledge management approaches are significantly associated with an agile value chain, and that the dimensionality of these relationships captures important components of supply chain agility, including manufacturing cost control, share in market and production response, process virtualisation, and online collaboration [81]. It is suggested that effective supply chain management (SCM) may be enhanced by having a unified knowledge management (KM) and strategy [82]. A productive supply chain is established when buyers and sellers exchange information using IT. Virtual supply networks are essentially information-based rather than physical.

This paper examines the capacity of knowledge management and its relations with competitive advantage and supply chain agility [83]. Agile supply chain practices and knowledge management (KM) have been noted as being crucial for performance as a whole by fostering more responsive and ductile businesses that are able to adapt their resources to the changing market demands in order to gain long-term competitive advantage. Receiving efficiently motivates an organisation to exploit its knowledge-based resources for sustainable competitive advantage (CA), and the knowledge capacity of a firm enables the organisation to develop in a competitive direction. Supply chain agility (SCA) has become a critical factor that greatly impacts the success of organisations [84]. The key to obtaining sustainability in supply chains depends almost exclusively on knowledge and its efficient management [85]. The competitiveness and supply chain agility of the firm are significantly affected by knowledge management abilities, i.e., absorptive, transformative, and inventive capabilities [83]. Table 1 presents the relationships among the variables within the theoretical framework.

Table 1.

Overview of the principal prior research.

H8.

Knowledge management capabilities positively correlate with agile supply chain.

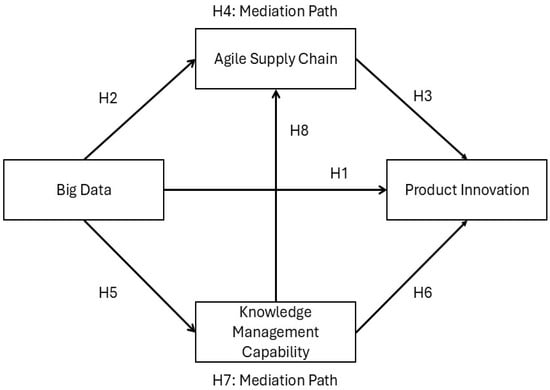

2.5. Model of the Study

A theoretical framework has been established to examine the relationship between big data [86] as the independent variable and product innovation [87] as the dependent variable within the Jordanian pharmaceutical industry. The literature substantiates the idea that big data fosters corporate product innovation by establishing a definitive and strong correlation between big data and product innovation.

The impact of this big data model on pharmaceutical product innovation in Jordan has been studied. Research shows that although pharmaceutical innovation is successful, big data has its attributes [86], an agile supply chain [88], and knowledge management [89]. Additionally, the speed at which big data is analysed has a greater impact on enhancing creative product innovation. Figure 1 depicts the interrelations among the variables.

Figure 1.

Model of study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling Method and Collection Procedure

The sample comprises 381 managers from pharmaceutical companies in Jordan, who vary in terms of gender, age, experience, educational credentials, administrative level, management hierarchy, and tenure in their current positions. This variation offers an in-depth comprehension of how various organisational levels and functions perceive and impact the researched variables. A survey conducted by the Jordan Food and Drug Administration indicated that the pharmaceutical sector employed more than 7000 workers in 2024, with women constituting approximately 36% of the workforce. A quota-based random sampling procedure was used to collect the data, and electronic questionnaires were emailed to HR managers. Senior and middle management were selected as the target group, since they are more actively involved in knowledge management, supply chain activities, and data processing than personnel at lower levels. Hence, they were more likely to understand and interpret the question accurately when answering it. This also contributes to a greater understanding of Jordanian pharmaceutical companies and makes it easier for them to find a way towards producing innovation. The Qualtrics sample size calculator was applied to accurately determine the required sample size for the study, as attested in previous studies. This produced a sufficient sample of 381, at a 95 percent confidence level and five percent margin of error.

In order to meet the aims of the research, a survey was included and distributed by email to senior and middle management in Jordanian pharmaceutical companies from April to August 2025. Schedule and method of the survey were designed to be flexible enough to meet participants’ availability and objectives between data collection periods [90]. The response rate is evaluated systematically by the research group. It adapts to maintain participant interest and answer questions, but follow-up emails were sent as reminders in order to attempt to ensure that both sampling is representative and data collection is efficient.

3.2. Measures

A questionnaire with five sections: demographic characteristics, big data [86], product innovation [87], agile supply chains [88], and knowledge management [89]. It was developed to examine the research variables. A 5-point Likert scale was used to quantify this. A quantitative research approach was employed to thoroughly investigate the interaction among knowledge management, lean supply chains, big data, and product innovation. The questionnaire is an efficient and effective tool for data collection and analysis, facilitating problem-solving and fostering product innovation in the Jordanian pharmaceutical business.

4. Data Analysis

The Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS 26) program used structural equation modelling (SEM) to examine the relationships between big data, product innovation, agile supply chains, and knowledge management in pharmaceutical manufacturing companies. The study used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), a sophisticated statistical technique, which is employed to understand the factor structure of a dataset and test hypotheses about the relationships between observed data and the underlying constructs. This method makes it possible to analyse complex causal networks and also the simultaneous investigation of multiple interactions. To validate measurement scales, items with factor loadings of at least 0.50 were included, although our final model showed that the loadings for all retained items were substantially higher than 0.75.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

This study was started by gathering information from 413 pharmaceutical industry managers in Jordan. During the initial data screening, it was found that 32 of the questionnaires showed problematic response patterns, had significant amounts of missing information on the most important variables (more than 10% of the responses were missing in each questionnaire), and there was also an indication of straight-lining (identical responses on multiple construct scales). Our subsequent analysis was based on 381 valid questionnaires after the removal of these incomplete responses. The dataset after the exclusion of responses demonstrated great quality of data with very few missing values (less than 0.5% for each measured variable). Verification of the data by Little’s MCAR test shows that any missing data that remain are completely at random (χ2 = 94.82, df = 92, p = 0.398); thus, our analytical approach is justified. While the demographic profile of the sample provided is similar to that for the wider pharmaceutical workforce of Jordan, details on non-respondents were not obtained. Accordingly, no definitive judgement about the potential for non-response bias is possible.

The Table 2 shows that the participant characteristics in the sample were similar to the workforce composition of the pharmaceutical sector in Jordan, which is usually seen. One out of three respondents, almost two-thirds, were males (65.1%), which is in line with the industry’s current gender employment trends. The age demographics of the respondents were dominated by mid-career professionals. The largest group (43.3%) was between 30 and 42 years, and nearly one-quarter (24.7%) were young professionals under 30 years of age. Most of the professional experience levels were concentrated in the (10–15) year bracket (31.2%), which shows that participants had an organisational amount of industry knowledge. Educational attainment was very high, as nearly 30% of the respondents had graduate-level qualifications. The hierarchical distribution facilitated the collection of voices across the different organisational levels. Close to one-third were from executive positions and two-thirds from middle management, thus reflecting a wide range of organisational perspectives.

Table 2.

Demographic employees (N = 381).

The Table 3 shows that the correlation analysis indicates substantial positive associations among all variables (p < 0.001). Big data exhibits a robust positive association with “knowledge management” (r = 0.61) and moderate positive associations with “agile supply chain” (r = 0.54), radical product innovation (r = 0.48), and incremental product innovation (r = 0.41). “Knowledge management” demonstrates a substantial positive correlation with “agile supply chains” (r = 0.59) and moderate positive associations with “radical” (r = 0.52) and “incremental” (r = 0.46) “product innovation”. Similarly, agile supply chains demonstrate moderate positive correlations with radical (r = 0.49) and “incremental” (r = 0.44) “product innovation”. All constructions exhibit substantial internal consistency (α > 0.88), with means ranging from 3.47 to 3.92 on a 5-point scale, indicating moderately favourable perceptions of big data implementation, knowledge management capabilities, “agile supply chain” practices, and “product innovation” in Jordanian pharmaceutical companies.

Table 3.

Descriptive data: mean and standard deviation (N = 381).

4.2. Measurement Model

The research revolves around four major constructs that were derived from the questionnaire and tested hypotheses. Big data, as the first construct, was evaluated through 14 items that covered 4 aspects: volume, velocity, variety, and veracity. Each of these aspects reflected a particular big data in the implementation of the pharmaceutical organisations. Volume (4 items) was about the amount of data analysed, whereas velocity (4 items) concerned the speed of data processing. Variety (3 items) dealt with the number of data sources used, and veracity (3 items) was about the quality and reliability of the data being processed [86].

The second construct, knowledge management, was represented by 12 items that were split into three dimensions: acquire, transfer, and distribute. Acquire (3 items) is an internal capacity of an organisation to recognise and acquire knowledge from both external and internal sources. Transfer (6 items) looked at the organisation’s internal processes of synthesising and distributing knowledge, and distribute (3 items) referred to the efficiency with which the information was shared with the external stakeholders [89].

The third one, agile supply chain, was a construct that had 9 associated items. All of these items, in their totality, describe the flexibility, responsiveness, and adaptability of the pharmaceutical companies’ supply chain operations with respect to supplier relationships, capacity adjustments, and responding to customer demands [88].

The fourth construct, product innovation, was represented by two different dimensions: radical product innovation and incremental product innovation, each comprising five items. Radical innovation items depicted radical changes to existing products (e.g., products that differ substantially, radical innovations introduced more frequently than competitors), whereas Incremental Innovation items showed minor enhancements of existing products (e.g., products that differ slightly, incremental improvements to existing lines) [87]. The questionnaire is included in the Appendix A to provide a detailed description of all measurement components.

For hypothesis testing, product innovation was considered as individual dimensions and a combined construct as well. Since the original hypotheses (H1, H3, H4, H6, H7) refer to “product innovation” as one concept, this dual approach allowed us to test both.

Firstly, the overall influence of the predictors on innovation, in general, could be examined. Secondly, their differential effects on different types of innovation could be investigated.

4.3. Measurement Model Validation

The Table 4 shows that the measurement model used that we used had statistically strong qualities for all the outlined criteria. The factor loadings for all the items varied between 0.76 and 0.88; thus, they were well above the traditionally minimal acceptability threshold of 0.50 and also above the more stringent threshold of 0.70 that is recommended for those scales that are already established. The scales were highly reliable, as evidenced by the composite reliability coefficients that varied from 0.889 to 0.932 and were well above the recommended threshold of 0.70.

Table 4.

Scale attributes and dimension: the factors loading (N = 381).

Convergent validity was strongly supported by all average variance extracted (AVE) values being between 0.63 and 0.72, which were a lot higher than the 0.50 threshold suggested [91]. Additionally, discriminant validity was confirmed through the Fornell–Larcker criterion since the maximum shared variance (MSV) values were always lower than the respective AVE values for each construct, thus indicating that there was sufficient differentiation between the constructs that were assessed.

The Table 5 shows that the detailed measurement model has an excellent fit according to all the fit indices. The χ2/df ratio (2.17) reflects a perfect fit, which is well under the limit of 3.0. Both the CFI (0.93) and the TLI (0.92) are above the minimum acceptable value of 0.90, thus indicating very good incremental fit. The RMSEA (0.055) and the SRMR (0.048) are also indicative of good fit as both are less than 0.08. The RMSEA 90% confidence interval [0.048, 0.062] is thus in agreement with the model’s stability, as the upper limit is still less than the 0.08 cutoff. These convergent fit indices constitute strong evidence in fa-vour of the measurement model as a good representation of the observed data.

Table 5.

Modelling fitting indicators (N = 381).

4.4. Assessment of Common Method Bias

Since all the data were gathered through self-reported questionnaires from the same individuals at a single point in time, we evaluated the possible common method bias (CMB) by multiple approaches that are suggested in the recent methodological literature.

Full Collinearity Assessment. At first, we performed a full collinearity test by calculating variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all latent constructs according to the approach suggested by [93]. This test is considered to be more robust than Harman’s single-factor test in identifying common method variance in structural equation models. The VIF values were in the range of 1.90 to 2.92, with all of them staying well below the conservative threshold of 3.3. To be exact, the VIF values were big data (2.61), knowledge management (2.92), agile supply chain (2.51), and product innovation (1.90). The findings from this analysis suggest that common method variance is not a significant source of error in the results.

Harman’s Single-Factor Test. Secondly, we executed Harman’s single-factor test by loading all 45 measurement items onto a single factor in exploratory factor analysis. The first unrotated factor accounted for 38.9% of the total variance, which is considerably less than the 50% threshold proposed by [94]. This result can also be considered as evidence that a single source of common method factor does not dominate the covariance of the measures. The agreement between both statistical tests (VIF < 3.3 and Harman’s test < 50%) reinforces the trust in the absence of a substantial common method bias.

Procedural Remedies. Thirdly, to lessen potential CMB ex ante, we took several procedural actions were taken during the data collection: (1) through clear statements on the cover page of the questionnaire, we assured respondents were assured of their complete anonymity and confidentiality, (2) by placing predictor variables (big data, knowledge management, agile supply chain) and criterion variables (product innovation) in different sections with intervening demographic questions, the variables were psychologically separated thus helping respondents see them as different constructs, (3) to reduce the possibility of different interpretations of the questions and the complexity of the questionnaire, we used clear and concise item wording was used that was validated during the pre-test with five pharmaceutical managers, and (4) where it was possible within dimensional subscales, the counterbalancing of the question order was applied to minimise consistency motifs.

The convergence of two independent statistical tests and multiple procedural controls gives us substantial assurance that common method bias is not a major factor that undermines the validity of our structural model results.

4.5. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

We built a structural model to evaluate the impact of big data on product innovation, with knowledge management and agile supply chain as possible mediators. In line with our predictions that regarded “product innovation” as a single construct, we constructed a combined measure by fusing both radical and incremental innovation for the initial hypothesis testing. Moreover, we conducted additional analyses to determine the influence of radical and incremental innovation separately to shed more detailed light on the phenomena.

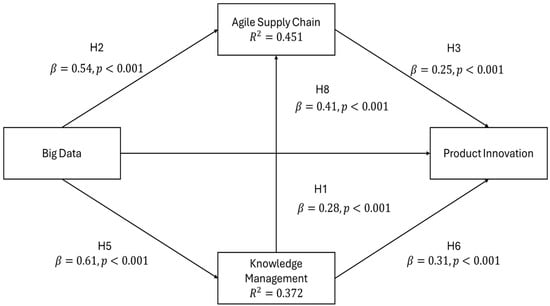

The Table 6 shows that the results of the structural model support the confirmation of all hypothesised direct relationships. Big data has a very significant positive direct impact on product innovation (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), knowledge management (β = 0.61, p < 0.001), and an agile supply chain (β = 0.54, p < 0.001). Knowledge management (β = 0.31, p < 0.001) and an agile supply chain (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) are both strongly positively correlated with product innovation. In addition, knowledge management has a positive effect on an agile supply chain (β = 0.41, p < 0.001). None of the path coefficients is insignificant, as all the critical ratios (t-values) are far beyond the 1.96 threshold, providing strong evidence for the theoretical framework. The 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for all paths do not include zero, thus confirming the robust nature of the relationships.

Table 6.

Structural model results for direct effects (N = 381).

In order to test the mediation hypotheses (H4 and H7), we used bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to generate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects. This was in line with the recommendations of [95].

The Table 7 shows that the examination of pathway contributions informed the researchers about the major changes that big data is making to product innovation. The direct pathway accounted for less than half (46.3%) of the total effect, whereas significant indirect influences were felt via two key organisational capabilities. Knowledge management was the main mediating mechanism, thereby explaining almost one-third (31.3%) of the total effect, while agile supply chain practices made up an additional 22.4%. The statistical strength of these results was verified by bootstrap confidence intervals that indicated the significance of all the pathways, as they did not include zero at the 95% confidence level.

Table 7.

Decomposition of influence analysis (N = 381).

This set of outcomes offers strong support for our mediation hypotheses, in particular, that both knowledge management capabilities (H7) and agile supply chain practices (H4) are the main sources of the intervening mechanisms by which big data capabilities lead to increased product innovation. The two mediating pathways, being complementary, imply that pharmaceutical companies have to develop not only the organisational knowledge infrastructure but also the operational supply chain flexibility in order to be able to fully exploit the innovation returns from big data investments.

4.6. Supplementary Analysis: Effects on Radical vs. Incremental Innovation

To grasp more clearly the different ways big data affects various innovation types, we examined the impacts of big data on radical and incremental product innovation separately. The findings showed that the positive effects of big data on radical innovation, as opposed to incremental innovation, were stronger and more consistent across all the channels.

The Table 8 shows that the overall positive effect of big data on radical innovation was around 35.3% higher than its effect on incremental innovation (0.69 versus 0.51), which indicates that big data is of particular importance to disruptive innovations. The difference in the effect was very significant for the way through an agile supply chain (60% more for radical innovation), which suggests that supply chain flexibility may be especially necessary for breakthrough innovations that require a rapid reconfiguration of resources and processes. The way through knowledge management revealed more balanced effects (29.4% more for radical innovation), which implies that knowledge capabilities support both innovation types almost to the same extent. These results carry significant strategic implications: pharmaceutical companies looking for breakthrough innovations should focus on big data velocity and supply chain agility, while companies that are only interested in continuous improvement can obtain good results with moderate investments in these capabilities.

Table 8.

Effects on radical vs. incremental product innovation (N = 381).

The Table 9 shows the theoretical framework explains the majority of the variance for all the key constructs and thus can be said to have strong explanatory power. In the case of product innovation overall, the model accounts for 43.5% of the variance, meaning that the combination of big data capabilities, knowledge management practices, and agile supply chain processes explains a large part of the variation in pharmaceutical companies’ innovation outcomes. This R2 value is regarded as quite substantial in the field of organisational research, where R2 values above 0.33 are generally considered to indicate strong explanatory power [96].

Table 9.

Explained variance (N = 381).

Analysing the different innovation types separately, the model has more explanatory power for radical innovation (47.2%) than for incremental innovation (37.6%), the difference being 9.6 percentage points. The pattern is consistent with the conclusion that big data and related mechanisms have far more impact on radical innovations than on incremental ones, probably because radical innovations obtain more pattern recognition and prediction capabilities from big data analytics.

Regarding knowledge management, the variance accounted for (37.2%) indicates that the implementation of big data is a major driver of the knowledge management capabilities of pharmaceutical companies, while other factors not included in the model (e.g., organisational culture, leadership support, IT infrastructure) should be considered as well. In the case of an agile supply chain, the model captures 45.1% of the variance, indicating that the interplay between big data and knowledge management is responsible for almost half of the changes in supply chain agility. The relatively high R2 for the agile supply chain (0.451) as compared to knowledge management (0.372) implies that these constructs are especially powerful in predicting supply chain flexibility.

Theoretically, the R2 values are a testament to the soundness of the framework and emphasise that big data is a key enabler of innovation, not only by direct impact but also through mediating mechanisms, in the Jordanian pharmaceutical industry. The levels of explained variance are either at the same level as or higher than those reported in the studies on innovation antecedents conducted in pharmaceutical and manufacturing contexts.

4.7. Summary of Hypothesis Testing

All eight hypotheses were substantiated by the data collected from the field, which is in line with the theoretical framework that was set up. H1, the hypothesis that big data would have a positive impact on product innovation, was corroborated with a substantially positive direct effect (β = 0.28, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.40]). This direct effect is responsible for 46.3% of the overall impact of big data on innovation, which means that the data analytics capabilities are a source of innovation even if the mediating mechanisms are not perfect.

H2, a statement that big data has a positive effect on agile supply chain, was confirmed with a high degree of certainty (β = 0.54, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.42, 0.66]). The model shows that this is the second-strongest path, thus indicating that data-driven insights have a major role in enhancing the supply chain responsiveness. The findings of H3 indicate that there is a positive link between the agile supply chain and product innovation (β = 0.25, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.13, 0.37]), thus implying that operational flexibility can be converted into innovation outcomes. H4, a statement that agile supply chain is a mediator in the relationship between big data and product innovation, was corroborated with a significant indirect effect of 0.14 (95% CI [0.08, 0.19], p = 0.002), which represents 22.4% of the total effect.

H5, a claim that big data has a positive effect on knowledge management, was supported with a high degree of confidence, as it was the path with the largest coefficient in the model (β = 0.61, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.49, 0.73]). The establishment of such a strong link indicates that big data is the main source of organisational knowledge capabilities. H6 substantiated the positive link between knowledge management and product innovation (β = 0.31, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.18, 0.44]), which means that knowledge infrastructure is a direct facilitator of innovation. H7, a statement that knowledge management is a mediator in the relationship between big data and product innovation, was corroborated with a significant indirect effect of 0.19 (95% CI [0.12, 0.26], p < 0.001), representing the most substantial mediating pathway at 31.3% of the total effect. Lastly, H8 established a positive dependency between knowledge management and the agile supply chain (β = 0.41, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.53]), implying that knowledge capabilities facilitate organisational flexibility.

The results show that big data in the pharmaceutical industries in Jordan has been a driving force behind product innovations through direct and indirect routes. There is a partial mediation in the relationship between big data and product innovation through two factors, i.e., agile supply chain practices (H4, which contributes to 22.4% of the total effect) and knowledge management capabilities (H7, which contributes to 31.3% of the total effect), with the direct effect making up the remaining 46.3%. The simultaneous development of these two capabilities, i.e., knowledge management and agile supply chain, would thus be the best strategy of pharmaceutical firms to maximise the innovation dividend coming from big data investments.

Moreover, additional analysis showed that the role of big data in radical innovation was much more prominent than in incremental innovation, with the overall effects for breakthrough innovations being 35.3% higher. The difference was especially noticeable through the agile supply chain channel (60% stronger for radical innovation), thereby indicating that supply chain agility is particularly necessary for transformative innovations that require a quick reconfiguration of the resource base. All the relationships were positive and statistically significant, thus lending support to the theoretical framework, which holds that big data, if effectively used through efficient knowledge management and agile supply chain, will significantly increase pharmaceutical companies’ capabilities to innovate, especially in the case of transformative innovations that require a considerable deviation from existing products.

The R2 values give an account of the proportion of explained variance in the endogenous constructs. The indices serving as model fit demonstrate that the data fit perfectly: χ2/df = 2.17 (threshold < 3.0), CFI = 0.93 (threshold > 0.90), TLI = 0.92 (threshold > 0.90), RMSEA = 0.055 with 90% CI [0.048, 0.062] (threshold < 0.08), and SRMR = 0.048 (threshold < 0.08). The 5000 times bootstrap confidence intervals are used for the robust estimates of the parameter stability.

Figure 2 shows the structural equation model highlighting multiple routes that allow big data to have an impact on product innovation. In fact, the research uncovers that there exist, on the one hand, direct influences (big data directly enabling the innovation through improved analytical capabilities), and on the other, indirect influences, which are mediated via organisational capabilities.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model with standardised path coefficients and explained variance. Note: In addition, the information about all paths is that they are significant at p < 0.001. The paths that are on the standardised path coefficients (β) are shown with 95% bootstrap confidence.

The first indirect route is through knowledge management, where big data makes the firm proficient in acquiring, transferring, and distributing knowledge (β = 0.61) and, then, consequently, the organisation innovates in product development (β = 0.31); therefore, the indirect effect accounts for 0.19.

The second indirect route happens through the agile supply chain, where big data brings about supply chain flexibility and responsiveness (β = 0.54) that, in their turn, support innovation outcomes (β = 0.25) and, thereby, the indirect effect amounts to 0.14.

Moreover, a consecutive path is available through which big data empowers knowledge management (β = 0.61); thereafter, the agile supply chain capabilities are (β = 0.41), and, finally, the product innovation (β = 0.25) is getting credit. The intricate pattern of direct and indirect effects reflected in the study is consistent with the idea that data-driven innovation is a multi-layered process in pharmaceutical organisations.

The levels of variance that have been accounted for serve as proof of the model’s explanatory power. Product innovation (R2 = 0.435) is an example where the fusion of big data, knowledge management, and agile supply chain explains most of the variation in innovation outcomes.

Knowledge management (R2 = 0.372) indicates that big data capabilities are the key factor that leads to the development of the organisation’s knowledge infrastructure.

Agile supply chain (R2 = 0.451) points out that big data, together with knowledge management, explains nearly half of the changes in supply chain flexibility.

The difference in explanatory power for radical innovation (R2 = 0.472) as opposed to incremental innovation (R2 = 0.376) is an additional piece of evidence that the model is especially good at breakthrough innovations, which is in line with the theoretical expectation that big data analytics are particularly helpful in spotting patterns that lead to transformative rather than just incremental advances.

5. Discussion

The findings provide empirical support for the proposed relationships between sustainability-oriented big data analytics and product innovation in Jordanian pharmaceutical companies.

5.1. Sustainability Big Data and Innovation: Direct Effects

The presence of a significant direct effect of sustainability big data on product innovation (β = 0.28, p < 0.001) in our research is instrumental in extending [19] framework by suggesting that environmental and social analytics metrics, when receiving focus, become a novel source of innovation even under the sustainability umbrella. The linkage is becoming extremely crucial, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry in Jordan, which is experiencing a heavy pressure load to address sustainability-related pressures in areas such as resource use and responsible sourcing, etc. [3].

There is a moderate correlation (r = 0.48, p < 0.001), which signifies that pharmaceutical companies are capable of achieving the twofold goal of developing innovative products and, at the same time, realigning their innovation efforts with sustainability objectives. This finding goes against the view that the implementation of sustainability initiatives would impede innovation [7] and, instead, is in line with the view that environmental data analytics open up innovation avenues that are at the same time consistent with broader sustainability principles at the conceptual level. Nonetheless, the direct effect is responsible for only 46.3% of the total effect of sustainability big data, which suggests that organisational capabilities play very important roles as mediators and that their roles are beyond the existing literature that mainly focuses on direct relationships [6,7,8].

5.2. Knowledge Management as a Sustainability Translation Mechanism

As far as the mediation effect is concerned, knowledge management is the stronger one as it accounts for 31.3% of the total effect (β = 0.19, p < 0.001), thus making its decisive role in the conversion of sustainability-oriented big data into the innovation strategies that can be implemented visible. This aligns with the recent studies, which emphasise that the implementation of sustainable innovation depends on the capabilities of capturing, integrating, and applying environmental and social knowledge [53,54,55].

In the context of the pharmaceutical industry, knowledge management makes it possible for companies to gain sustainability intelligence from sources such as environmental monitoring systems, regulatory bodies, and stakeholder feedback; through insight transfer about concepts related to sustainable practices across different organisational units; and by sharing sustainability knowledge with external partners. The strong connection between sustainability, big data, and knowledge management (β = 0.61, p < 0.001) indicates that the processing of environmental and social data is associated with improvements in organisational learning capacity; thus, it is in line with the Knowledge-based View, which states that the acquisition of sustainability-related knowledge is a strategic resource for organisations [53].

Companies that are efficient in the management of sustainability knowledge can discover opportunities for innovation that not only meet the requirements of the market but, at the same time, may conceptually contribute to addressing sustainability challenges, e.g., by the innovative approaches that align with sustainability principles, innovative approaches consistent with sustainability principles.

5.3. Agile Supply Chain as a Sustainability Enabler

The agile supply chain is the instrument that accounts for 22.4% of the total effect (β = 0.14, p = 0.002), thus demonstrating how flexibility on the operational level may support companies in pursuing sustainability-oriented innovation efforts. Sustainability-oriented big data is a source of real-time visibility of sustainability-related operational data.

By the use of an agile supply chain, companies can quickly react to changes in the environment by, for instance, making operational adjustments consistent with sustainability principles. This work serves as an extension of the work of [33] by showing that supply chain agility is not only about meeting the needs of the market rapidly but also about adapting operational processes in ways that align with sustainability considerations. The connection between knowledge management and agile supply chain (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) indicates that sustainability knowledge may be employed as one of the enablers of supply chain flexibilities by providing knowledge that may inform sustainability-related operational decisions.

As a result, these two mediating paths together account for 53.7% of the total effect of big data on innovation, the rest 46.3% being the direct effect, indicating that pharmaceutical companies should build up knowledge infrastructure as well as operational flexibility at the same time.

5.4. Sustainability and Innovation Type Differentiation

Our further analysis reveals that the total effect of sustainability big data on radical innovation is 0.69, a figure which is slightly higher (35.3%) than that on incremental innovation (0.51). The difference lies in particular with the agile pathway, where the impact on radical innovation is 60% stronger (0.16 vs. 0.10), now suggesting that some step changes in sustainability innovations may require adjustments at an operational level.

For radical sustainable innovation, companies may pursue sustainable innovations and emphasise the need for agile supply chains. Companies may focus on process improvements to support incremental sustainable innovations. The knowledge management mode has less difference; the effect on radical innovation is 29.4% higher than that of incremental innovation, indicating that knowledge capabilities similarly promote two types of innovations.

5.5. Theoretical Implications for Sustainable Innovation

This study extends the theory of sustainability innovation in several ways. Firstly, by providing the evidence that environmental and social data analytics constitute a dynamic capability that enables the firm to sense sustainability opportunities, seize them through innovation, and reconfigure resources towards sustainable operations, the research integrates Dynamic Capability Theory with sustainability research [12,13,14].

Second, the paper provides empirical evidence that sustainability and innovation should be viewed as mutually reinforcing rather than competing objectives. Sustainability-oriented big data plays the role of a catalyst for innovation outcomes by uncovering novel opportunities at the intersection of enhancing environmental performance and creating market value.

Third, the study results show that sustainable innovation is a deeply layered process that requires the coordinated efforts of data analytics, knowledge management, and operational capabilities. The dual mediation pathways put forward by the research cast doubts on the simplified linear models, which presume direct relationships between sustainability initiatives and innovation outcomes.

Fourth, by revealing these relationships in the pharmaceutical sector of Jordan, we are broadening the scope of sustainability innovation theory to include the sectors of the less developed countries, which is a very significant point in view of the fact that the developing economies are confronted with distinct sustainability issues such as limited environmental regulations, resource constraints, and competing development priorities [1,7].

Fifth, the differentiated effects on radical versus incremental innovation (35.3% stronger overall effect on radical innovation) offer a real-world basis from which it could be argued that sustainability-oriented big data can give rise to radical innovations that have the power to change the pharmaceutical products and processes fundamentally.

5.6. Practical Implications for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Development

Pharmaceutical managers must ensure that companies create robust data systems that not only monitor environmental and social metrics but also do so throughout the entire value chain. Sustainability data should interact with the four big data dimensions—volume, velocity, variety, and veracity—so that real-time environmental performance monitoring becomes possible. Enterprises need to put in place systematic mechanisms for sourcing environmental intelligence, sharing sustainability insights between different units of the business, and also supplying sustainability knowledge to those in the supply chain.

As agile supply chains represent 22.4% of the total effect of big data, companies should focus on making their supply chains more flexible. This could include, for example, the development of mutually beneficial relationships with environmentally certified suppliers, the implementation of reverse logistics for pharmaceutical waste, and the ability to quickly and easily switch to sustainable materials and processes. Companies on a path of breakthrough sustainable innovations need to put more emphasis on data analytics, velocity, and supply chain responsiveness, whereas those who are committed to continuous environmental improvement may, at the same time, invest more evenly in all three areas of capability.

Sustainability and innovation are two sides of the same coin, according to managers. By using big data in an environmentally friendly way, companies can simultaneously shrink their carbon footprints and identify new profitable innovation opportunities. An example may be the creation of green pharmaceuticals that have both environmental and market advantages, the lowering of waste disposal costs, or the proactive fulfilment of future regulatory requirements.

Government support for environmental monitoring systems, sustainability reporting standards, and data-sharing platforms would be enablers for pharmaceutical companies to have access to trustworthy sustainability data, policymakers in Jordan and similar emerging markets should argue. The government, as a policy actor, can play its role by, for instance, giving tax incentives to sustainable pharmaceutical innovation; offering subsidies to green technology adopters; promoting preferential government procurement of environmentally certified products; and facilitating collaboration in sustainability-oriented research.

Spending on education in data science with a focus on sustainability, starting green chemistry training programmes, and building industry knowledge-sharing networks would go a long way in developing the sector’s capability to leverage sustainability data for innovation [3]. Clearly defined environmental standards for pharmaceutical manufacturing will pave the way for market-driven, sustainability-oriented innovation. Since the pharmaceutical sector is a major contributor to Jordan’s GDP and exports [2], positioning Jordan as a regional leader in sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing could be the key to export competitiveness, especially in the European markets that have strict environmental requirements.

5.7. Sustainability Context and Broader Implications

The pharma industry is burdened with sustainability issues that are quite different from any other sector. Drugs are a continuous source of pollution since, after patient excretion or improper disposal, they make their way into water systems and change the composition of aquatic ecosystems. In some cases, they may also come into drinking water supplies. As a consequence of sustainability big data, firms are now able to design molecules that have a shorter environmental persistence by using predictive modelling and also be able to track their impact on nature throughout the product lifecycle.

The manufacture of pharmaceuticals, in turn, is a very energy and water-intensive process and quite polluting. Most of the pollution is caused by the use of solvents in the chemical synthesis and purification of the products. Being a real-time sustainability data user, in this case, would allow them to optimise their manufacturing processes to lessen their environmental footprint while still ensuring their products meet the necessary quality, safety, and efficacy standards.

Additionally, pharmaceutical supply chains are very long and spread over different countries. This, in turn, makes it a very complicated task to monitor the environmental performance of such chains. Big data analytics acts as a beacon of light in this respect, and hence, it is a key factor that enables companies to gain visibility with respect to the environmental practices of their suppliers. Besides that, it throws light on emissions caused by transportation and, most importantly, it also highlights the opportunities available for sustainable sourcing. All these put together empower companies to make the most informed decisions that are capable of creating a perfect balance among cost, quality, reliability, and environmental performance.

The pharmaceutical sector generates substantial waste, such as expired medications, packaging materials, and byproducts of manufacturing processes. Analytics dedicated to sustainability can pinpoint that sector’s waste reduction, recycling, and circular economy implementation measures. Worldwide, environmental regulations on pharmaceuticals are becoming stricter with more focus on environmental risk assessment, setting manufacturing emissions standards, and extended producer responsibility. Companies that use sustainability big data as a resource can forecast changes in regulations and propose compliant innovations ahead of time.

These sustainability demands, coupled with the market prospects for green pharmaceuticals and the growing aversion of healthcare systems to environmentally damaging products, position sustainability-driven innovation not only as an environmental imperative but also as a source of competitive advantage.

5.8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations point to potential areas of further research. Firstly, our research has established relationships between sustainability, big data, and innovation. Still, the next research should include objective environmental performance metrics such as verified emissions reductions, measured waste minimisation, and documented water conservation, along with innovation measures.

Secondly, which is a substantive limitation of cross-sectional design both we are unable to assess the extent to which reverse causality and omitted variable bias might be underlying relationships being observed. For this reason, the significant links found in our SEM analysis should be considered as theoretically supported relationships rather than evidence for causal influences. It would be preferable to have longitudinal studies in the future to gain a better understanding of the temporal dynamics of building sustainable capabilities and their effect on firm performance so that stronger causal inferences can be drawn.

Thirdly, our research lacks knowledge of non-respondents. While the final sample mirrors the demographics of those working in the industry, because information about nonrespondents is not available, a full evaluation of possible nonresponse bias cannot be made. Therefore, the generalisation of the results needs to be considered cautiously.

Fifth, our research was only concentrated on the pharmaceutical industry in Jordan, which may affect the extent of the research’s applicability. Comparative research in developing and developed countries would explain how institutional contexts, environmental regulations, and resource availability influence these relationships.

Fourthly, although our research considered big data in four dimensions, future research could delve deeper into the sustainability analytics practices. The study of the use of lifecycle assessment systems, the development of carbon footprint analysis tools, the creation of water footprint tracking platforms, and the building of circular economy optimisation models would supply the exact guidance to the managers.

Sixth, subsequent studies might explore how sustainability-oriented big data can be compatible with personalised medicine, digital health platforms, biotechnology advances, and precision manufacturing. Studies focusing on stakeholder engagement may explore how pharmaceutical companies utilise big data to deal with pressures from regulators, healthcare systems, environmental advocacy groups, and consumers.

Lastly, investigations comprising conflicts and compromises in environmentally friendly pharmaceutical innovations, such as the trade-off between environmental performance and product efficacy, the balancing of upfront costs against long-term savings, or the handling of conflicting expectations between environmental performance and affordability, will offer feasible advice to practitioners.

6. Conclusions

This investigation offers broad empirical proof showing that sustainability-focused big data analytics is a major factor in product innovation in the pharmaceutical industry of Jordan, while also helping to achieve environmental and social goals. Our research, based on 381 pharmaceutical managers’ responses, shows that sustainable innovation can be achievable if data analytics, knowledge management, and operational capabilities are strategically combined.

The study comes up with three significant conclusions. Firstly, sustainability big data has a very strong direct impact on product innovation, which is almost half of its total effect, thus confirming that environmental and social data analytics are the main facilitators of innovation. Secondly, it is very important to recognise that knowledge management capabilities and agile supply chain practices not only serve as the critical transition mechanisms but also that knowledge management is responsible for about one-third and agile supply chain for about one-quarter of the total effect, thus indicating that sustainable innovation demands coordinated capability development. Thirdly, the effect of big data on radical innovations is much more considerable than on incremental innovations, especially when going through the supply chain agility pathway.

This investigation concurs with the sustainability innovation theory by providing evidence that environmental and social data analytics is a dynamic capability for sustainable innovation, by uncovering new mediation mechanisms that complement each other, showing that sustainability and innovation are mutually reinforcing, extending sustainability innovation frameworks to pharmaceutical contexts of the developing economy, and differentiating sustainability data effects on transformative as opposed to incremental innovations.

To pharmaceutical executives, sustainable innovation means integrated investments in all-inclusive sustainability data systems recording environmental and social metrics; knowledge management processes for acquiring, transferring, and distributing sustainability insights; flexible supply chains that are capable of quickly implementing sustainable practices; and differentiated strategies based on innovation objectives. Companies that are seeking radical innovations should put the speed of data analytics and supply chain responsiveness first, while companies that are focusing on continuous improvement can achieve their goals with more balanced investments.

For policymakers in Jordan and other such emerging markets, the results provide a clear path to improve pharmaceutical competitiveness while lessening the negative environmental impact by means of various measures, including developing a national sustainability data infrastructure; introducing incentives for green pharmaceutical innovations; implementing sustainability education and capacity building programmes; and having progressive environmental regulatory frameworks and becoming a regional leader in sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The findings are very significant at a time when the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing demands from all over the globe to reach a sustainable level. Some of the issues raised are the environmental persistence of pharmaceutical compounds in water systems, resource-consuming manufacturing processes, waste management problems, and the introduction of new environmental regulations. Our work reveals that the pharmaceutical sector in Jordan has the potential to increase both its competitiveness and environmental performance if it progresses in the region of investments in strategic data analytics for sustainability-oriented organisations.

Although limitations such as the cross-sectional design and single-country focus require that generalisation be made with caution, the study has substantial contributions in understanding how pharmaceutical companies in developing economies can leverage sustainability-oriented big data analytics to achieve enhanced innovation capabilities and improved environmental and social performance.

To sum up, this research offers a clear picture of the pharmaceutical industry’s sustainable innovation as being not only environmentally required but also strategically beneficial. Companies that develop abilities to collect, review, and implement sustainability data, backed by strong knowledge management and adaptable operations, will be able to stand out competitively while they are contributing to the global sustainability goals and promoting the health and well-being of communities worldwide. The interplay of environmental necessities, regulatory pressures, and market opportunities for sustainable pharmaceuticals, therefore, presents a strong business case for the capability development pathways identified in this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.M. and A.S.; Methodology, S.M. and A.A.; Formal Analysis, S.M., S.I. and K.S.M.A.; Investigation, A.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.M., A.Ç. and A.M.K.; Supervision, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as it involves the use of anonyous surverys/questionnaires distributed to employees without collecting any personally identifiable information, posing no more than minial risks to participants, by the Scientific Research Ethic Committee of Cyprus University of Health and Social Sciences.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author can provide the data used in this study upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| 1. Demographic factors | ||||||

| 1. Gender Male Female | ||||||

| 2. Age 18–30 years 30–42 years 42–54 years >54 years | ||||||

| 3. Work Experience 0–5 years 5–10 years 10–15 years >15 years | ||||||

| 4. Management Level Top Management Middle Management | ||||||

| 5. Education Level Bachelor’s Degree Postgraduate | ||||||

| 2. Big Data independent | ||||||

| 2.1. Volume | ||||||

| VOL1 | In the company, we analyze large amounts of data. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VOL2 | In the company, the quantity of data we explore is substantial. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VOL3 | In the company, we use a great deal of data. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VOL4 | The company, we scrutinise copious volumes of data. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2.2. Velocity | ||||||

| VEL1 | In the company, we analyse data as soon as we receive it. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VEL2 | In the company, the time period between when we get new data and when we analyze it is short. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VEL3 | In the company, we are fast in exploring our data. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VEL4 | In the company, we analyze data speedily. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2.3. Variety | ||||||

| VAR1 | In the company, we use several different sources of data to gain insights. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VAR2 | In the company, we analyze many types of data. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VAR3 | In the company, we examine data from a multitude of sources. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2.4. Veracity | ||||||

| VER1 | In the company, we deal with precise and certain data. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VER2 | In the company, we analyze high-quality data. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| VER3 | In the company, we process data that is reliable and consistent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Knowledge Management | ||||||

| 3.1. Acquire | ||||||

| ACQ1 | Our company can identify the knowledge needed from external sources. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ACQ2 | Our company can acquire the knowledge needed from external sources. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ACQ3 | Our company can identify the knowledge from internal sources that will be used by our company. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3.2. Transfer | ||||||

| TRA1 | Our company can collate and synthesize knowledge acquired from external sources. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| TRA2 | Our company can transfer (to record and store) the knowledge acquired from an external source to become internal knowledge. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| TRA3 | Our company can collate and systematize knowledge acquired from internal sources. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| TRA4 | Our company is able to organize internal knowledge to be transferred to (shared with) staff who require this knowledge. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| TRA5 | Our company is able to apply existing knowledge to create new knowledge. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| TRA6 | Our company will transfer (share) this new knowledge to staff who need it. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3.3. Distribute | ||||||

| DIS1 | Our company will periodically evaluate which internal knowledge should be shared with the public. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| DIS2 | Our company will organise the knowledge that will be shared with the public into handouts, videos, or reports. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| DIS3 | Our company will share the knowledge with the public through lectures, seminars, market reports, or advertisements. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3.4. Agile Supply Chain | ||||||

| ASH1 | Our supply chain selects suppliers based on their performance on flexibility and responsiveness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH2 | Our supply chain maintains short, flexible relationships with suppliers. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH3 | Our supply chain can increase short-term capacity as needed. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH4 | When needed, our supply chain can adapt its operations as much as is necessary to execute our decisions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH5 | Production planning has the ability to respond quickly to varying customer needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH6 | Our supply chain can adjust/expedite its delivery lead times. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH7 | Our supply chain makes in responds to customer demand. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH8 | Our supply chain can make adjustments to order specifications as requested by our customers. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| ASH9 | Our supply chain structure often changes to contend with volatile market conditions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. Product Innovation | ||||||

| 5.1. Radical Product Innovation | ||||||

| RPI1 | Our new products differ substantially from our existing products. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| RPI2 | We introduce radical product innovations into the market more frequently than our competitors. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |