Abstract

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) hinges critically on extensive international cooperation. However, the extent and evolution of such cooperation at the global level, along with the relative synergy contributions of different country groups, remain insufficiently studied and inadequately quantified. This study aims to assess the level of global cooperation in advancing the SDGs from 2001 to 2023. It further examines the synergy contributions of countries across different income groups and geographic regions. To this end, a synergy-based statistical framework is employed for the analysis. Our results indicate that global cooperation has shown a steady upward trend during this period, yet substantial disparities persist across different goals and indicators. High-income countries contributed most to economic SDGs, whereas low-income countries contributed most to environmental and social SDGs. Regionally, North America and Europe contributed most to economic synergy. Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean made more substantial contributions to social and environmental progress. This study enhances the understanding of global cooperation dynamics related to the SDGs. It also provides evidence-based insights to support the design and timely adjustment of more effective international cooperation strategies.

1. Introduction

To address the most pressing challenges facing humanity, the United Nations adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to promote peace and prosperity for people and the planet. These goals span three dimensions: economic, environmental, and social. Despite notable progress [1,2,3], no nation can achieve all objectives alone, given disparities in resources, capacities, and stages of development. Thus, strengthening global cooperation has become a prerequisite for sustainable development [4,5,6]. SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) underscores the importance of partnerships. These partnerships rely on multilateral cooperation, financial assistance, technology transfer, and capacity building. Their purpose is to close development gaps and accelerate progress.

While the importance of international cooperation is widely acknowledged, systematically measuring it remains challenging. Cooperation takes diverse forms, including informal partnerships, technology transfers, and policy coordination, many of which are difficult to quantify or track over time [7]. The SDGs’ broad and complex indicator framework, coupled with varying national priorities and trajectories, further complicates rigorous assessment [8,9].

Existing research has focused on development assistance flows, multilateral mechanisms, and international agreements. In the field of international aid, Li et al. [10] find that the governance capacity of recipient countries is closely related to the effectiveness of foreign aid. Aid to countries with high governance capacity contributes more to their sustainable development. Mary and Mishra [11] also find that international aid reduces both the incidence and the duration of civil wars. In addition, a substantial body of research on specific types of aid, including climate aid [12], trade aid [13], and international food aid [14]. In terms of building cooperation mechanisms, Kidd and McGowan [15] develop an international cooperation framework to support marine spatial planning. Against the backdrop of global decarbonization, Lindner [16] finds that international cooperation on hydrogen energy has increased significantly. Shi and Yin [17] review studies on carbon footprints and find that most international cooperation occurs among European and North American countries. Cooperation in developing countries remains relatively limited. Other scholars investigate global green technology cooperation networks and find that the number of countries participating in green technology cooperation is increasing [18]. John et al. [19] use qualitative research methods to examine the fulfillment of international agreements. They find that agreements such as the Paris Agreement promote cooperation among stakeholders. Najarzadeh et al. [20] finds that since the entry into force of the Kyoto Protocol, global greenhouse gas emissions have decreased substantially. Additionally, a large body of research on other agreements, such as the Amazon Cooperation Treaty and the North American Free Trade Agreement [21,22].

These macro-level studies offer valuable perspectives but often fail to reveal whether countries cooperate effectively on specific SDG indicators. They also provide limited insights into how cooperation levels evolve or how contributions differ by income group or region. This gap limits understanding of how cooperation operates in practice. It also hinders the identification of strengths and weaknesses in outcomes. As a result, policymakers lack robust evidence for designing targeted collaboration strategies.

To fill this gap, this study introduces the concept of synergy as a quantitative tool for measuring the level of global cooperation in achieving the SDGs [23,24]. Rather than relying solely on documented agreements or financial flows, this method uses statistical techniques to detect covariation in SDG performance among countries. It captures more comprehensive and often implicit patterns of cooperation.

Drawing on SDG indicator data from 2001 to 2023, this study evaluates the global levels of cooperation in advancing the SDGs and quantifies the synergy contributions by income group and region. Analyzing these perspectives helps clarify the cooperation landscape and its challenges. It also provides quantitative evidence to support the development of more targeted and effective strategies. The main contributions of this study are twofold. (1) It develops a systematic methodological framework to quantify global cooperation levels and their trends across specific SDG indicators. This framework provides robust and verifiable evidence for assessing the evolution of international cooperation. (2) It conducts an in-depth analysis of the synergistic contributions of countries at different income levels and across different regions in the economic, environmental, and social dimensions. This analysis reveals the heterogeneity of global cooperation and offers empirical support for designing international cooperation policies.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Standardization

This study uses original data on SDG indicators obtained from the 2025 Sustainable Development Report, which primarily aggregates data from international organizations such as the World Bank. These organizations adopt rigorous data validation procedures, ensuring the scientific reliability of the dataset.

Due to data availability constraints, we selected 64 SDG indicators that cover 167 countries and regions from 2001 to 2023 (see Supplementary Table S1). Table 1 presents the definitions and expected directions of these indicators. Specifically, a positive sign (+) is assigned to indicators whose increasing values indicate improvement in target conditions or reduced risk. A negative sign (−) is assigned to indicators whose decreasing values reflect the mitigation of adverse effects or progress toward the target. In line with the World Bank’s official income classification standards, we categorized the 167 countries into four income groups based on the modal income category for each country during 2001 to 2023.

Table 1.

SDG indicators and their target directions.

In addition, all indicators are subjected to directional consistency treatment and normalization, such that larger standardized values uniformly indicate closer proximity to the SDGs. This procedure ensures the comparability of different indicators. The indicators are normalized using the following formula:

where is a unitless normalized indicator, with a yearly time step denoted as . denotes the overall number of years, denotes the actual value of the SDG indicator, and and correspond to the minimum and maximum values of the indicator observed across all years, respectively.

2.2. Within-Group and Between-Group Changes of SDG Indicators

The decomposition approach adopted in this study conceptually builds on the framework introduced in previous research [23]. That study separates indicator changes into domestic change (DC) and foreign change (FC). DC captures variations driven by internal structural or institutional adjustments, while FC reflects influences arising from cross-country interactions and external conditions. Extending this decomposition logic to a multi-group context, we adapt the original “domestic-foreign” structure to a “within-group-between-group” framework. This transformation enables the method to be applied to comparisons across income groups or geographical regions rather than individual countries. Accordingly, the fluctuations in SDG indicators are decomposed into within-group change (WGC) and between-group change (BGC), allowing us to capture the compound effects of both domestic and international dynamics on SDG performance.

For each SDG indicator over a period of years, the WGC is defined as a vector representing all pairwise distances between the indicator values of consecutive years. Specifically, for a given group , the distance of an SDG indicator from year to year is denoted as , and can be expressed as:

where the value of lies within the range [0, 1], with 0 indicating no WGC. The aggregated WGC for group over the entire period can then be calculated as:

WGC represents the within-group change observed among countries belonging to the same income level or geographical region, whereas BGC captures the composite change computed across all countries globally. Similar to WGC, the BGC of each SDG indicator is defined as a distance vector. However, unlike WGC, the distances for BGC are calculated across the entire set of countries, rather than within a single group. Let J denote the total number of country groups classified by income level or region. The BGC distance of a given SDG indicator from year t to t + 1 is expressed as dt, and is calculated according to the following formula:

Here, the value of dt typically varies within the range [0, ]. A distance of 0 indicates no between-group change, implying that all country groups, whether classified by income level or geographical region, have either already achieved their respective SDG targets or have chosen not to undertake further improvements. Similarly, the aggregate BGC for a given set of countries over the entire time horizon T can be expressed as follows:

2.3. Synergistic Effects and Synergy Contributions of SDG Indicators

The synergy effect of SDG indicators among countries grouped by either income level or geographical region can be quantified by jointly considering the within-group change for each group and the corresponding between-group change across different groups. This approach is grounded in the assumption that all country groups are simultaneously influenced by both intergroup diplomatic relations and intra-group dynamics. Accordingly, the synergy effect for countries classified by income level or region is defined as the difference between the within-group change of a specific group and the aggregate between-group change observed in the global context. This definition is aligned with the synergy-based analytical framework proposed in a recent study, which quantifies collaborative patterns by comparing within-group oscillations and cross-group dynamics [23]. Let denote the synergy effect of group J in year t; it is calculated as follows:

Dividing by J ensures that the synergy effect remains bounded within the range [0, 1). A synergy value of zero indicates that there was no net change in the global SDG indicator from year t to year t + 1. This outcome may arise either because no progress was made globally on the indicator, or because positive changes in some groups were offset by negative changes in others, thereby neutralizing the difference between within-group and between-group changes. In other words, a synergy effect close to zero reflects a scenario in which countries of different income levels or regions have persistently refrained from cooperation or engaged in mutual competition.

In contrast, when the sum of WGC values across the J groups exceeds the corresponding BGC value, the resulting synergy effect approaches 1, suggesting that all groups have made concerted efforts to improve SDG indicators collectively. The aggregate synergy effect across all groups over the entire study period can similarly be represented as a vector, expressed as:

It is important to note that the synergy concept proposed thus far can only quantify whether the different groups are acting cooperatively or competitively with respect to each other. However, this measure does not capture whether such cooperation or competition is directed towards improving SDG indicators in their expected direction, or conversely, towards deteriorating them in the opposite direction. Therefore, we use the concept of synergy direction, which is derived based on the gradient of inter-annual changes. The specific formula is given as:

In order to formally define the direction of change, we introduce the following function:

The output of the above sign function is then compared with the expected direction of each SDG indicator to determine the sign of the synergy effect, as formulated below:

A positive synergy signal indicates that the groups are collectively improving the SDG indicator in its expected direction, whereas a negative synergy signal suggests that the groups are acting collectively in the opposite direction, thereby hindering progress toward the target. Beyond the overall synergy effect, it is also necessary to quantify the contribution of each group to the global synergy outcome, providing a clearer understanding of their role within the overall system. In this study, we denote the contribution of group j to the global synergy effect from year t to t + 1 as , which is computed as follows:

Here, indicates whether the contribution of group j to the global synergy effect is positive or negative. Groups making a negative contribution should adjust their policies promptly and strengthen cooperation with other groups to advance progress toward the SDGs. It is worth emphasizing that the contribution of a single group to a given indicator may fall below −100% or exceed +100%, but the sum of contributions from all groups for that indicator will always equal 100% or −100%.

3. Results

3.1. Within-Group Changes Across Different Groups

First, we classified 167 countries worldwide according to their income levels and geographic locations (Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials). This study focused on 64 measurable SDG indicators, which were categorized into three dimensions: economic (SDGs 8–10, 12, 17), environmental (SDGs 6, 13–15), and social (SDGs 1–5, 7, 11, 16), as detailed in Table 1 [25,26]. Our analysis examined within-group changes in SDG indicators among countries grouped by income level and geographic region.

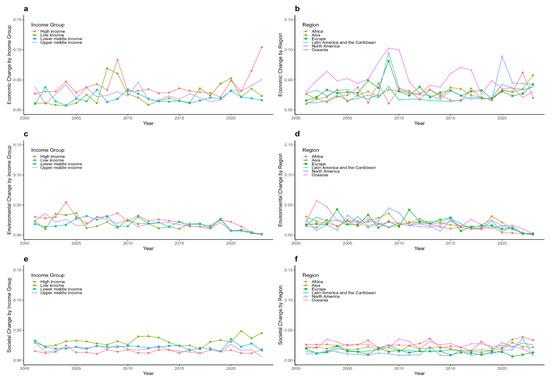

Figure 1 illustrates within-group changes for countries classified by income level and by region across the economic, environmental, and social SDG dimensions. Figure 1a shows the within-group changes in economic SDGs across income groups. The figure indicates that high-income and low-income countries had large fluctuations in 2008–2012 and 2020–2023. These changes were likely caused by the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic [27,28]. Figure 1c presents the within-group changes in environmental SDGs. Countries in all income groups show a broadly synchronized pattern over the study period. This is because they face similar environmental pressures, such as global warming and more frequent extreme weather events [29,30,31]. These shared shocks lead to similar movements in the indicators. Figure 1e shows the within-group changes in social SDGs. Low-income countries display large within-group changes throughout the entire period. In contrast, high-income countries maintain consistently low levels of variation.

Figure 1.

Within-group Changes in economic, environmental and social SDG indicators. Note that panels (a,c,e) present the within-group changes from 2001 to 2023 among countries classified by income level, while panels (b,d,f) show the within-group changes from 2001 to 2023 among countries classified by region.

Across regions, Figure 1b shows the within-group changes in economic SDG performance. Oceania, Europe, and North America display larger fluctuations in 2008. Their financial markets are highly open, which increases exposure to global shocks. Trade dependence also makes these regions sensitive to disruptions during crises [32,33]. Figure 1d presents the within-group changes in environmental SDG performance. The regions move in broadly synchronized trends. After 2015, within-group changes decreases in all regions. This decline relates to the Paris Agreement, which strengthened carbon control and ecological management [34,35]. Figure 1f shows the within-group changes in social SDG performance. Africa maintains high levels across the study period. North America remains low throughout. This reflects stable social indicators in high-income economies. Many African countries are low-income economies with greater room for improvement [36].

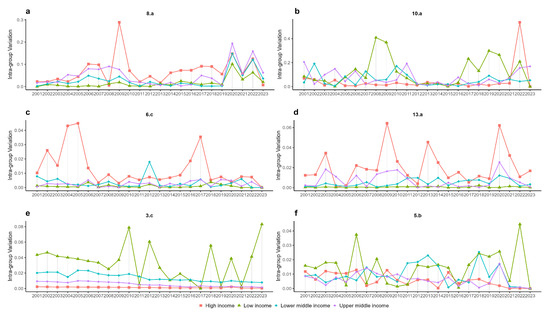

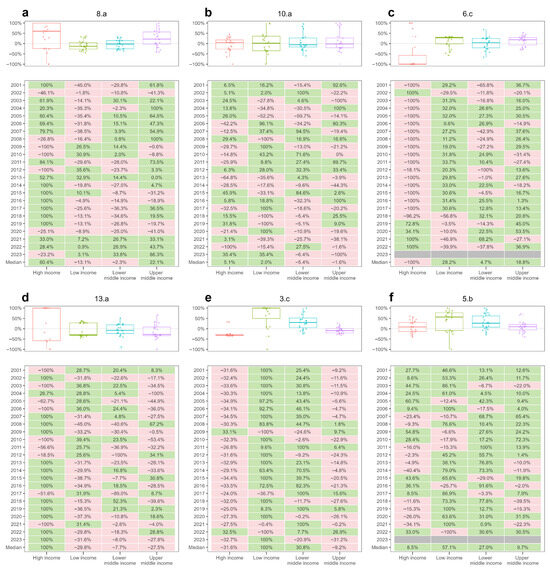

Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures S1–S10 (see Supplementary Materials) illustrate the within-group changes of 64 SDG indicators across different income-level country groups.

Figure 2.

Global within-group changes among countries at different income levels in six selected SDG indicators. (a) 8.a—unemployment rate, (b) 10.a—gini coefficient, (c) 6.c—freshwater withdrawal, (d) 13.a—CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement production, (e) 3.c—mortality rate, under-5, and (f) 5.b—ratio of female-to-male mean years of education received.

From Figure 2a, within-group change in unemployment is noticeably higher in 2008, 2020, and 2022 across countries at different income levels. This pattern may be linked to the 2008 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and the Russia–Ukraine conflict in 2022 [37]. Specifically, the pandemic resulted in large-scale shutdowns of labor-intensive industries, particularly in the service sector, and disrupted global supply chains, causing unemployment rates to surge worldwide. The outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war in 2022 generated severe volatility in energy, food, and raw material markets, destabilizing the global economy and indirectly affecting labor markets [38,39].

Figure 2b shows that low-income countries experienced larger within-group change in the Gini index during 2008–2009. In 2022, high-income countries displayed greater within-group change in this indicator. In 2022, the Russia–Ukraine war triggered surges in energy and food prices, compounded by high global inflation, which substantially increased living costs [40]. For example, the U.S. inflation rate reached 8% in 2022, the highest in nearly two decades, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Figure 2c shows that high-income countries experienced larger within-group change in freshwater withdrawal during 2001–2006 and 2016–2017. From 2001 to 2006, rapid global economic growth increased industrial activity and urbanization in high-income countries, which raised water demand. In 2016–2017, Europe faced record heatwaves and severe drought, which greatly increased agricultural irrigation needs.

From Figure 2d, high-income countries consistently exhibited high levels of CO2 emissions embodied in their fossil fuel exports. This was primarily due to advanced industrialization, with production long reliant on fossil fuels such as oil and coal. Although the share of renewable energy has been increasing, the pace of transition remains slow. Additionally, higher per capita incomes have supported high car ownership, frequent air travel, and elevated consumption levels, making substantial CO2 reductions challenging [41,42]. For instance, in 2022, car ownership was 850 vehicles per 1000 people in the United States, compared with 226 per 1000 in China, which has a similarly large population.

From Figure 2e,f, low-income countries show consistently high under-five child mortality. They also display larger gender gaps in years of schooling throughout the study period. Key factors include limited access to safe drinking water, inadequate nutrition, and insufficient medical treatment for preventable diseases [43]. Furthermore, institutional discrimination and traditional practices have continued to hinder progress toward gender equality.

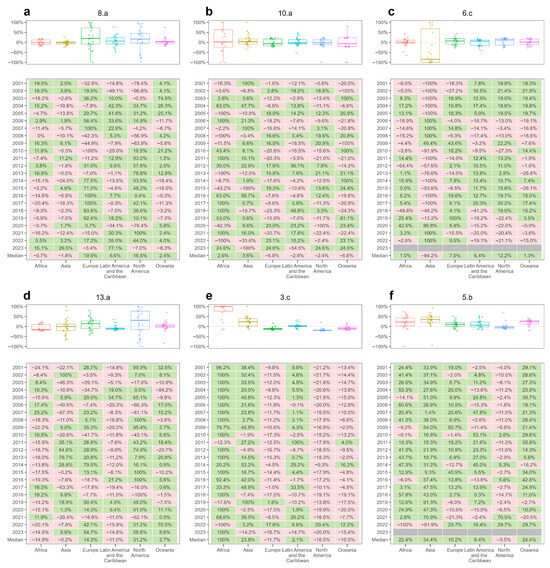

Figure 3 and Supplementary Figures S11–S20 (see Supplementary Materials) present the within-group changes of 64 SDG indicators across various regions.

Figure 3.

Global within-group changes among countries in different regions for six selected SDG indicators. (a) 8.a—unemployment rate, (b) 10.a—gini coefficient, (c) 6.c—freshwater withdrawal, (d) 13.a—CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement production, (e) 3.c—mortality rate, under-5, and (f) 5.b—ratio of female-to-male mean years of education received.

Figure 3a shows that all regions experienced larger within-group change in unemployment during 2008–2010 and 2019–2023. This pattern may be linked to the 2008 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and the Russia–Ukraine conflict in 2022. The result is consistent with our earlier findings. Figure 3b shows that Africa displays larger within-group change in the Gini index over the study period. This may be because many African economies rely heavily on resource exports, which concentrate wealth in the hands of a small share of the population [44]. Figure 3c shows that Asia has higher within-group change in freshwater withdrawal during 2001–2008 and 2016–2017, while the other regions display relatively small within-group change in this indicator. Between 2001 and 2008, Asia underwent rapid industrialization and urbanization, with major economies such as China and India substantially expanding water consumption for infrastructure development and manufacturing activities [45,46,47]. During 2016–2017, severe droughts struck South and Southeast Asia due to climatic factors. To ensure agricultural production and domestic water supply, freshwater withdrawal surged again. Notably, the strong El Niño event caused Vietnam to experience its worst drought in nearly a century in 2016. Figure 3d shows that most regions exhibit higher within-group change in CO2 emissions during 2008–2009 and 2020–2021. This was largely due to expansionary fiscal and monetary policies adopted worldwide to stimulate economic recovery in the wake of the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic [48]. These measures fueled infrastructure investment, boosting demand for cement, coal, and other carbon-intensive materials, which in turn elevated per capita carbon emissions [30]. For example, in response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Chinese government launched a $586 billion stimulus package, with more than half allocated to infrastructure construction. Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. government implemented massive fiscal stimulus measures. These included multiple rounds of cash transfers, such as those under the CARES Act. The transfers significantly increased household disposable incomes and stimulated consumption of high-carbon goods, such as electronics. As a result, emission burdens further increased [49]. Figure 3e shows that Africa experiences larger within-group change in under-five child mortality over the study period. This pattern is mainly linked to weak healthcare systems, low vaccination coverage, and limited prevention and treatment of common infectious diseases. Poverty and low educational attainment also restrict families’ access to medical services. In some areas, prolonged armed conflicts have further weakened public health systems [50]. In addition, Figure 3f indicates that Asia and Africa both show larger within-group change in the gender gap in years of schooling.

3.2. Gross Synergy

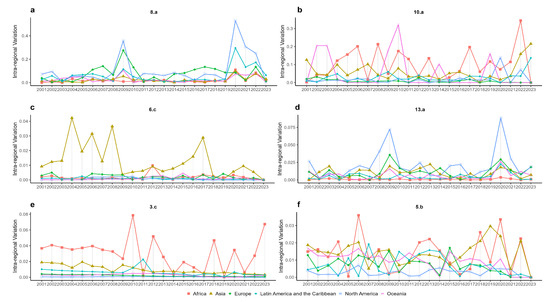

Gross synergy measures the degree of cooperation among countries in the process of achieving the SDGs. If some countries make progress toward the SDGs in the expected direction, their overall synergy will increase; conversely, if they move away from the goals, the gross synergy will decrease. From Figure 4, when countries are classified by income level, approximately 86% of SDG indicators exhibited a positive average gross synergy, compared with about 84% when classified by region. This indicates that, during the study period, most SDG indicators showed positive synergies at the global level. Countries worldwide jointly improved the majority of SDG indicators, although specific indicators still require further cooperative efforts.

Figure 4.

Gross synergies of 64 SDG indicators across countries, classified by income level and region, 2001–2023. Panels (a,b) illustrate the average gross synergies of 64 SDG indicators among countries worldwide, classified by income level and by region, over the study period. Panels (c,d) show the proportion of years during the study period in which countries worldwide, classified by income level and by region, exhibited positive gross synergies.

When grouped by income level, the highest positive average gross synergies were recorded for indicator 9.b (Mobile broadband subscriptions) and indicator 5.d (Seats held by women in national parliament), both reaching 0.013. High-income countries generally possess technological and financial advantages, whereas low-income countries have large potential demand and development space for digital infrastructure. These complementary conditions fostered synergy through technology transfer, investment, and project implementation. In parallel, international conventions continued to be promoted, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. These conventions encouraged countries across income groups to adopt institutional measures, including parliamentary seat quotas. These measures have led to substantial global progress in increasing the proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments. By contrast, when grouped by income level, the smallest average gross synergy was observed for indicator 2.e (Sustainable Nitrogen Management Index) at −0.016. This suggests that cooperation among income groups to reduce nitrogen fertilizer use faces considerable challenges [51].

When grouped by region, the highest average gross synergy was found for indicator 14.c (Fish caught by trawling or dredging), at 0.017, whereas the lowest was for indicator 2.b (Prevalence of obesity), at −0.009. With the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, broad international consensus on marine ecological protection has been established. The coordination and consistency of related policies have also improved significantly. Consequently, efforts to reduce obesity have involved limited cross-regional cooperation. These efforts depend heavily on region-specific dietary patterns and lifestyles. As a result, obesity shows the lowest level of synergy among regions.

The proportion of years with positive gross synergy is a useful metric. It helps assess whether cooperation among countries, classified by income level or region, represents a sustainable long-term pattern or only a short-term occurrence. As shown in Figure 4, this proportion is zero for indicator 2.b (Prevalence of obesity) and indicator 15.c (Red List Index of species survival). This finding suggests a lack of close global cooperation in reducing obesity and protecting biodiversity. This situation may impede progress toward SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). It may also increase systemic risks to global health and species survival. If this situation persists, achieving the SDGs will face serious challenges in the future [52,53].

3.3. Synergy Contributions from Different Groups

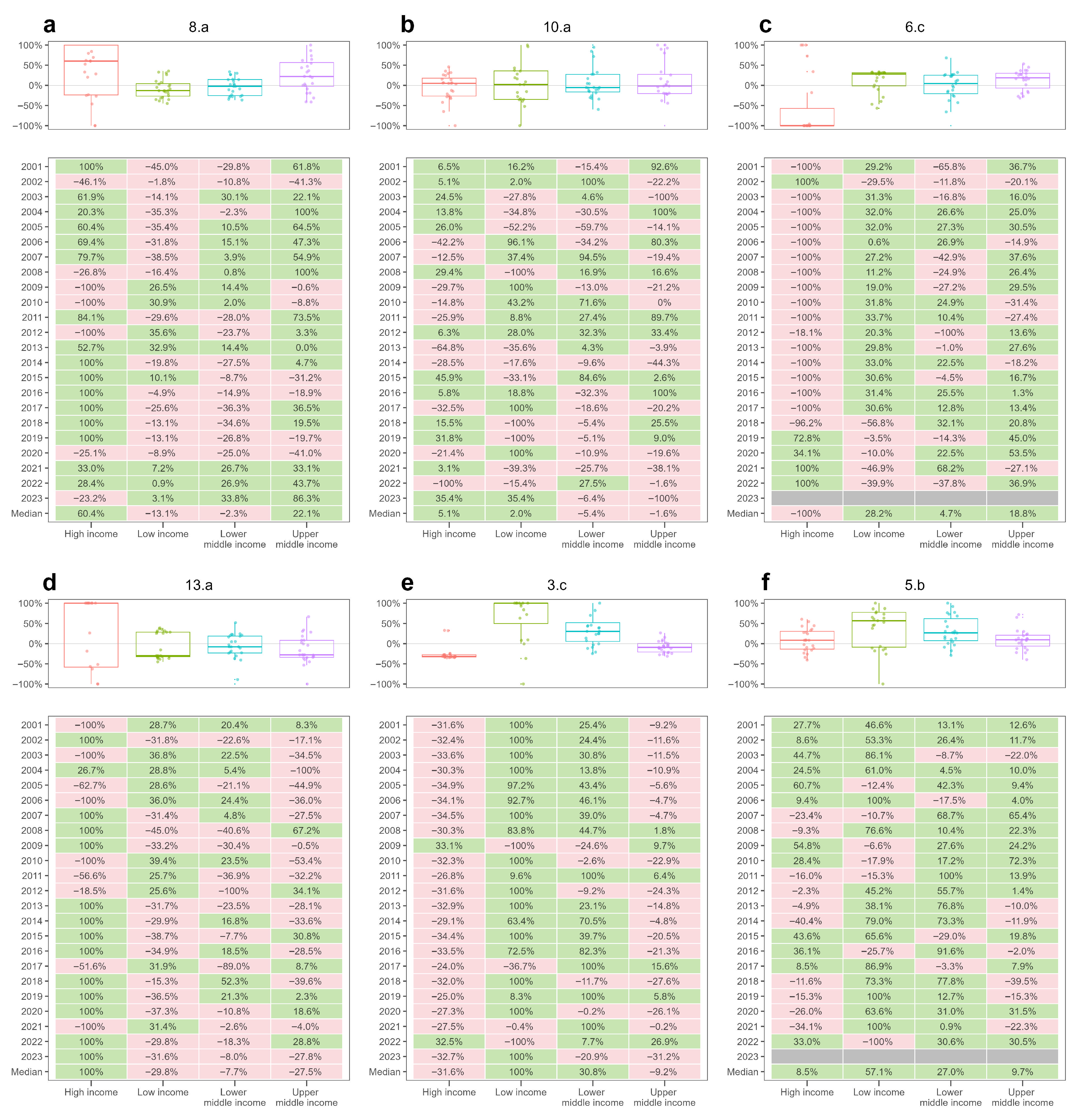

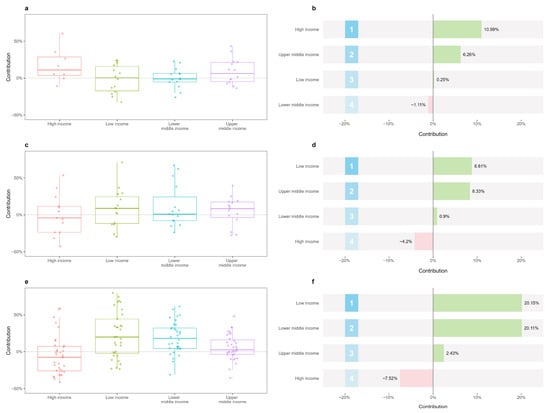

To enhance global cooperation in achieving the SDGs, it is essential to evaluate the synergy contributions of different country groups. Such an assessment identifies key areas for collaboration. It also provides a scientific basis for resource allocation, policy design, and international cooperation. These insights help support more targeted global sustainable development strategies. Figure 5 and Supplementary Figures S21–S30 (see Supplementary Materials) present the synergy contributions of countries at different income levels to 64 SDG indicators from 2001 to 2023. Figure 6 and Supplementary Figures S31–S40 display the contributions of countries in different regions for the same indicators and period. The results show that all income groups contributed negatively to reducing unemployment during the COVID-19 pandemic. High-income countries had the largest negative contribution (−41.0%). Low-income countries had the smallest (−8.9%).

Figure 5.

Synergy contributions by income group for six selected SDG indicators. (a) 8.a, (b) 10.a, (c) 6.c, (d) 13.a, (e) 3.c, and (f) 5.b. Cells shaded in green represent positive contributions, whereas those shaded in red correspond to negative contributions. Gray-shaded cells indicate either the unavailability of data for a particular year or the absence of synergy calculations for that time point. It is important to emphasize that the median values shown in the lower section of each panel capture only the overall contributions of countries grouped by income level to each SDG indicator throughout the 2001–2023 period. These medians are not constrained to total +100% or −100%, as they serve to reflect general directional patterns rather than precise proportions.

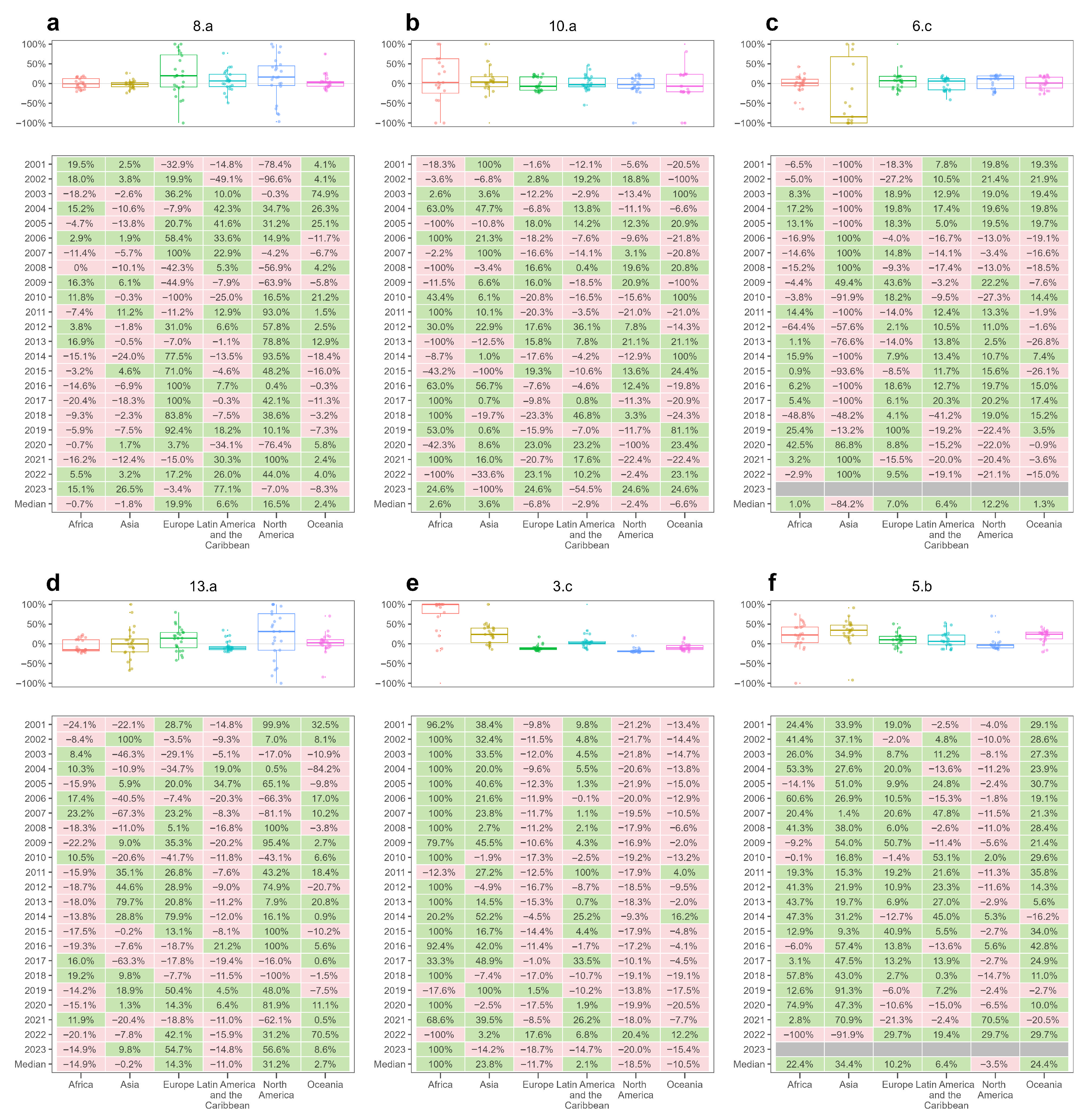

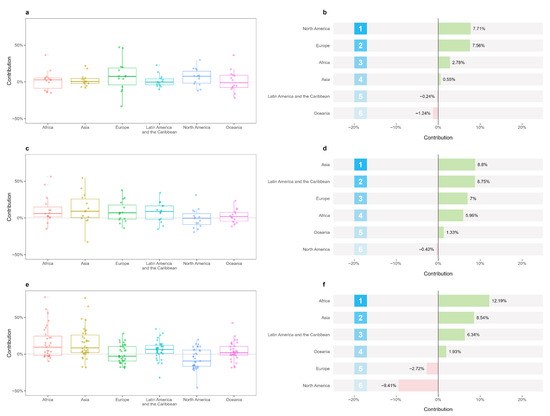

Figure 6.

Synergy contributions by region for six selected SDG indicators. (a) 8.a, (b) 10.a, (c) 6.c, (d) 13.a, (e) 3.c, and (f) 5.b. Cells shaded in green represent positive contributions, whereas those shaded in red correspond to negative contributions. Gray-shaded cells indicate either the unavailability of data for a particular year or the absence of synergy calculations for that time point. It is important to emphasize that the median values shown in the lower section of each panel capture only the overall contributions of countries grouped by region to each SDG indicator throughout the 2001–2023 period. These medians are not constrained to total +100% or −100%, as they serve to reflect general directional patterns rather than precise proportions.

Because synergy contributions may include extreme values, we used the median contribution for statistical analysis and visualization. This approach is reflected in the lower panels of Figure 5 and Figure 6 and in Supplementary Figures S21–S40. Between 2001 and 2023, high- and upper-middle-income countries made positive contributions to reducing global unemployment. Low- and lower-middle-income countries showed negative contributions. At the regional level, Africa and Asia contributed negatively. Other regions contributed positively. Europe (19.9%) and North America (16.5%) recorded the highest contributions. In terms of reducing global income inequality, high-income and low-income countries contributed positively, while the other two income groups had negative contributions. Regionally, Africa and Asia contributed positively, whereas the remaining regions had negative impacts. For freshwater withdrawal, rapid industrialization and urbanization caused high-income countries to make negative contributions. The other income groups contributed positively. Low-income countries made the largest positive contribution. At the regional level, Asia showed a negative contribution, whereas all other regions contributed positively. For CO2 emissions, high-income countries made positive contributions. This outcome reflects their long-term efforts in energy transition and clean energy development. Other income groups contributed negatively. Regionally, North America, Europe, and Oceania contributed positively, while other regions made negative contributions. Regarding the under-five mortality rate, low- and lower-middle-income countries contributed positively, while high- and upper-middle-income countries contributed negatively. This is largely because high-income countries had already reduced child mortality to very low levels, leaving limited room for further improvement. By contrast, even moderate declines in low-income countries had a significant impact on global progress. For example, World Bank data (2023) show that Singapore’s under-five mortality rate was about 2 per 1000 live births, one of the lowest worldwide. At the regional level, Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) contributed positively, with Africa ranking first, whereas the other regions contributed negatively. Finally, all income groups made positive contributions to improving the ratio of average years of schooling between men and women. Regionally, all areas except North America recorded positive contributions toward gender equality in education.

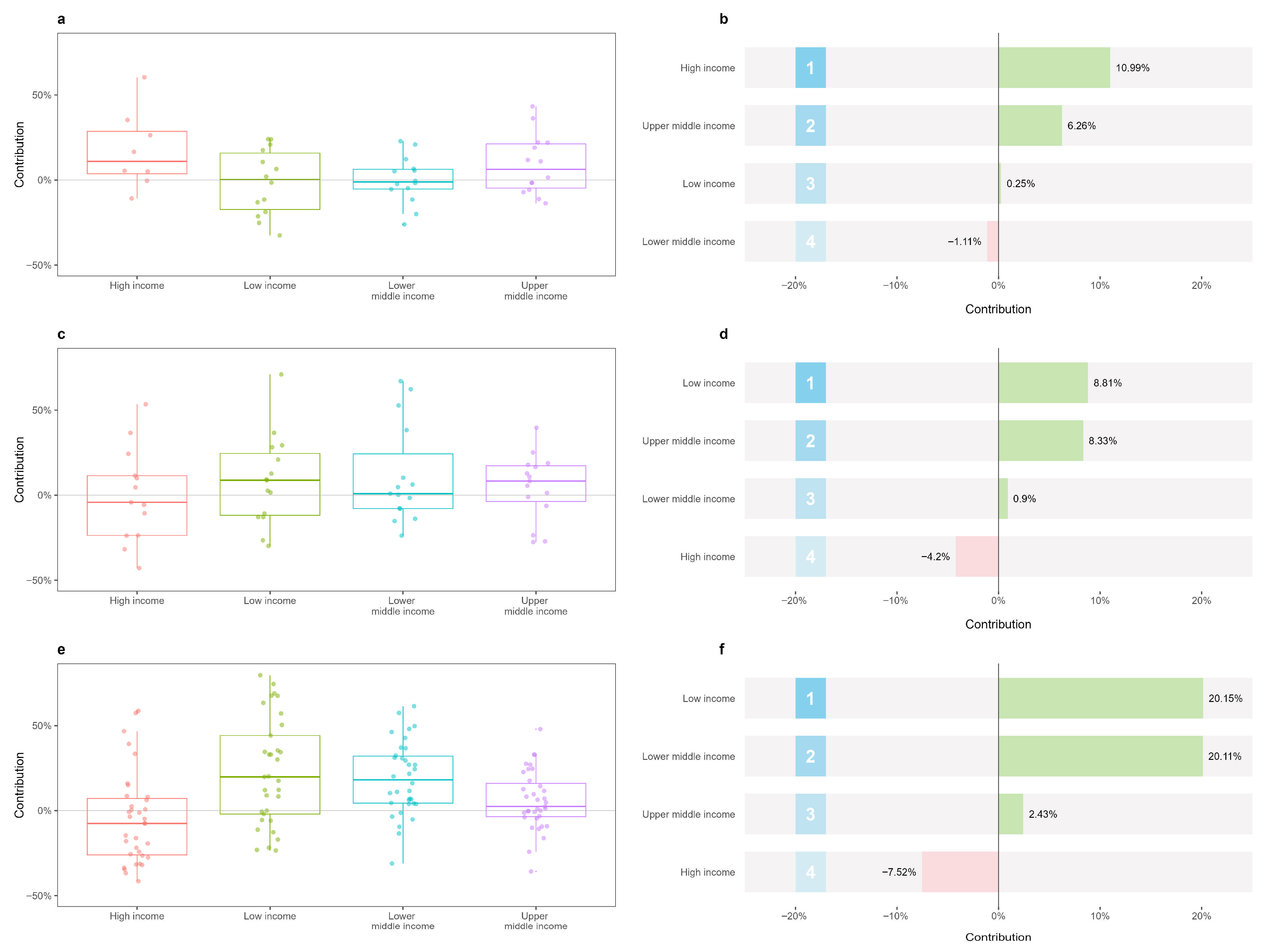

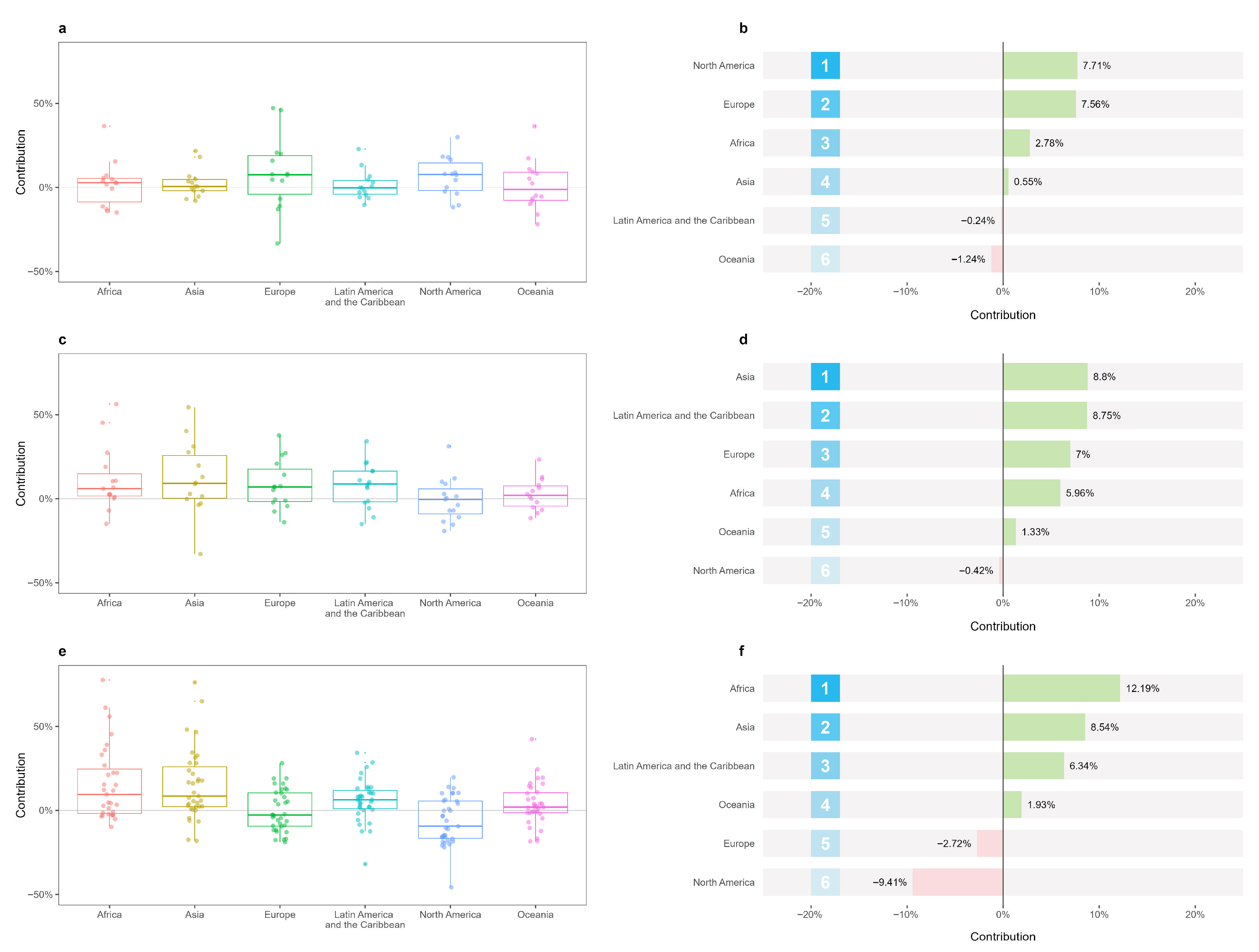

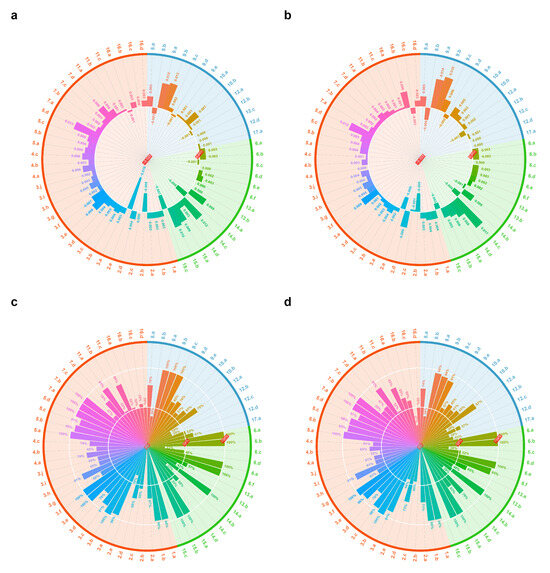

To evaluate the overall global contributions to economic, environmental, and social SDG indicators, we ranked country groups based on their median synergy contributions, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Between 2001 and 2023, all income groups made positive contributions to global economic development, with the exception of lower-middle-income countries. High-income countries made the largest contribution. Regionally, all areas except Oceania and Latin America and the Caribbean contributed positively. North America made the largest contribution, followed by Europe. This pattern underscores the reliance of global economic growth on developed economies in these two regions. Over the same period, all income groups contributed positively to global environmental sustainability except high-income countries. Low-income countries made the largest contribution. Regionally, all areas except North America made positive contributions. This outcome reflects North America’s long-standing dependence on a fossil-fuel-dominated energy structure, which has led to persistently high greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, the repeated withdrawal of the United States from major international environmental agreements has undermined the stability and consistency of global climate cooperation. For example, it exited the Kyoto Protocol in 2001 and, in 2025, initiated procedures to withdraw again from the Paris Agreement, which is expected to take effect in 2026. For social SDG indicators, all income groups except high-income countries contributed positively to global social sustainability. Low-income countries made the largest contribution. Regionally, all areas except North America and Europe contributed positively. Since the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals and later the SDGs, developing regions such as Asia and Africa have achieved substantial improvements in social sustainability. These gains have been supported by financial aid, technical assistance, and policy advocacy [33]. In contrast, North America and Europe had already reached high levels in many social indicators, such as child mortality rates and years of schooling. Their limited room for further improvement led to relatively negative synergy contributions to global progress [54,55].

Figure 7.

Aggregate contributions of countries classified by income level to the advancement of economic, environmental, and social SDG indicators. Panels (a,c,e) present boxplots of median synergy contributions from countries grouped by income level to all economic, environmental, and social SDG indicators, respectively. Panels (b,d,f) display the corresponding rankings of these income groups in advancing the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of the SDGs.

Figure 8.

Aggregate contributions of countries classified by region to the advancement of economic, environmental, and social SDG indicators. Panels (a,c,e) present boxplots of median synergy contributions from countries grouped by region to all economic, environmental, and social SDG indicators, respectively. Panels (b,d,f) display the corresponding rankings of these regional groups in advancing the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of the SDGs.

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

These findings underscore that global sustainable development is a complex and systemic challenge. It therefore requires more effective synergistic governance mechanisms grounded in differentiated responsibilities and equitable burden-sharing. This result aligns with the conclusions drawn in previous studies [56,57]. Viewed through the lens of pragmatic sustainability, these findings highlight the need for feasible forms of cooperation. Such cooperation must be adapted to specific national contexts. These approaches can help generate tangible progress across countries. To strengthen policy coordination and resource sharing across income levels and regions, this study proposes targeted policy actions. These actions aim to promote a more balanced, inclusive, and cooperative framework for advancing the SDGs across the economic, environmental, and social dimensions.

In the economic dimension, high-income countries may take the lead in advancing SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). They need to promote reforms to trade rules under the World Trade Organization framework. Reducing non-tariff barriers on exports from low- and middle-income countries can improve their competitiveness in global markets. They should also expand investment in key infrastructure, such as transportation, energy, and digital communications. Multilateral financing platforms, including the World Bank, can serve as effective channels for these investments. These efforts are expected to strengthen these countries’ integration into global value chains [58,59]. Middle-income countries may prioritize industrial upgrading by raising the added value of manufacturing and supporting local innovation systems. They can do this by developing domestic enterprise clusters and strengthening national research and development capacity. These efforts help improve the resilience of their economic structures. Low-income countries should make use of international development assistance and South–South cooperation to advance agricultural infrastructure. This can help stabilize food supply and create more employment in rural areas. A useful example is the Upper Atbara Dam Complex developed by China and Sudan. The project improved local irrigation conditions and raised water management efficiency. It also expanded irrigated farmland. As a result, agricultural productivity increased and farmers’ incomes grew.

From a regional perspective, Europe and North America may expand foreign direct investment and policy-based financing. They may also co-develop cross-border industrial parks and provide long-term financing instruments to systematically enhance the local manufacturing capacity of Africa, Asia, and LAC. These efforts may be supported by joint R&D programs, talent development, and institutional capacity-building. Together, these measures can establish a capital–technology–institution support mechanism. This mechanism can advance the global implementation of economic SDGs and promote fair, efficient, and sustainable economic cooperation. Asian countries may use initiatives such as the Belt and Road and RCEP to enhance infrastructure connectivity. They may also deepen cooperation with partners in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean on industrial planning, technology transfer, and logistics networks. These actions can help partner regions integrate into the global economy. Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean may build multilateral and intercontinental cooperation networks. They may also attract overseas investment. At the same time, they may improve the compatibility of local infrastructure and institutional systems. Through these efforts, they can gradually move from passive participants to co-designers of global economic cooperation rules.

In the environmental dimension, high-income countries may lead in meeting emission-reduction commitments and promote domestic green transitions through carbon pricing. They may also create international platforms for green technology sharing. These platforms can grant patent access for renewable energy and waste-recycling technologies to low- and middle-income countries [60]. The Green Energy Corridors project between Germany and India offers a representative pathway for middle- and low-income countries. Germany supported India through financial cooperation and technical assistance, including grid planning and wind-solar integration technologies. The project greatly improved India’s use of renewable energy and shows how green technology sharing can help optimize energy structures. Low- and middle-income countries may prioritize climate-adaptive infrastructure and develop community-level environmental monitoring and early-warning systems to enhance risk management capacity [61]. A combined approach of mitigation and adaptation can help them pursue more resilient development pathways and contribute to stable participation in global environmental governance.

Regionally, Europe and North America may jointly advance a global cooperation mechanism for green transition under SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 14 (Life Below Water), and SDG 15 (Life on Land). They can share governance experience and provide institutional advisory services. They can also license relevant technologies to Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean to help these regions design environmental governance systems suited to their development stage [62,63]. At the same time, Europe and North America may improve the coherence and predictability of their climate policies. This step can ensure that emission reduction commitments are effectively fulfilled and can set a strong example for the international community [64,65]. East Asian countries may use their clean-energy technology strengths to expand cooperation with Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean. They may work together on low-carbon urban development and pollution control, promoting technology transfer and capacity-building under South-South cooperation. Latin America, one of the world’s most biodiverse regions, may also leverage its forests, wetlands, and other ecosystems. It can work with Africa and Southeast Asia on forest conservation and water resource management. This collaboration would advance Global South efforts toward SDG 13 and SDG 15.

In the social dimension, high-income countries may strengthen systemic support for low- and middle-income countries through investment-driven international cooperation. Development funding may prioritize rural school construction, remote-learning facilities, and basic healthcare infrastructure. By integrating financing, technology, and institutional advisory services, they may actively participate in multilateral initiatives such as the Global Partnership for Education. Such efforts would better align resource support with capacity-building, thereby accelerating the implementation of social SDGs. Middle- and low-income countries can use multilateral platforms, such as the Global Partnership for Education, to obtain funding and technical support for basic education [66,67]. They can also work with multilateral institutions to build social data systems. These systems help increase accuracy and transparency in social governance. Real-world cases show clear benefits. One example is the education data platform developed by Bangladesh and UNICEF. The platform records student attendance, learning progress, and school resources. This helps the government detect dropout risks early and take timely action. Such evidence-based governance improves education equity and supports human capital development.

From a regional perspective, Europe and North America may continue supporting education infrastructure and primary healthcare development in developing countries. They can do this through mechanisms such as the Global Partnership for Education and the Gavi Alliance. They may also place greater emphasis on institutional capacity-building to help partner countries establish stable public service systems [68,69]. Countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Oceania may engage more actively in the global social SDG agenda. They can strengthen collaboration with international organizations, academic networks, and regional frameworks [70,71,72,73]. They may also deepen policy coordination in education, gender equality, and social inclusion. These efforts can help translate international cooperation experience into feasible domestic reform programs. Embedding such programs institutionally can ensure long-term and synergistic implementation of social SDGs [74,75,76].

4.2. Limitation and Prospect

Although this study yields some enlightening findings, it has several limitations in terms of methodology and data.

First, the synergy identified in this study primarily characterizes the consistency of changes in SDG indicators across countries. Such synergy may arise not only from institutionalized cooperation but also from the combined effects of global shocks and business cycles. Therefore, the synergy results should be interpreted as a composite reflection of cooperation potential and shared driving mechanisms, rather than as a direct measure of cooperation intensity in a strict causal sense.

Second, the dataset is drawn from the 2025 Sustainable Development Report. Due to challenges in quantifying many of the 231 UN indicators and the slow pace of data updates, our analysis includes only 64 indicators for 167 countries over the period 2001–2023. It should be noted that even within the same country or region, SDG performance can vary substantially across subnational areas. As data availability improves, future research will be able to assess global cooperation levels in SDG progress more comprehensively and with greater precision, particularly at the state or city level.

Third, in measuring the overall synergy contributions across the three dimensions, this study aggregates 64 indicators into the economic, environmental, and social dimensions using equal weights. This approach simplifies the differences in importance among indicators to some extent and may influence the results. Due to space limitations and methodological considerations, this paper has not yet conducted systematic robustness or sensitivity analyses based on alternative weighting schemes. Future research could compare results under different weight specifications to further enhance the robustness of the conclusions.

Finally, quantifying intra-regional cooperation in SDG implementation, as well as the contributions of international organizations such as BRICS, the G20, and the OECD, should be a priority for future studies. Analyzing cooperation at a more granular regional level will help identify specific challenges and support the formulation of better-targeted policy recommendations.

5. Conclusions

Enhancing international collaboration is essential for the attainment of the SDGs [4,5]. This study quantifies global cooperation on the SDGs from 2001 to 2023 and assesses the synergy contributions of countries, grouped by income level and geographic region, toward achieving the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of sustainable development. The results show that approximately 86% of SDG indicators for countries classified by income level, and about 84% for those classified by region, exhibit positive average gross synergies. This suggests that, since the launch of the MDGs and, particularly, following the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the global community has achieved phased collective progress in areas such as education, climate change mitigation, and infrastructure development. This synergistic trend underscores the importance of cross-border cooperation in advancing the SDGs and reflects growing convergence in institutional frameworks, policy orientations, and knowledge sharing. Although most indicators have improved through collaborative global efforts, 2.b (Prevalence of obesity) and 2.e (Sustainable Nitrogen Management Index) still require stronger international collaboration. These low-synergy indicators highlight the lack of effective coordination mechanisms and joint actions in critical areas such as nutrition improvement and sustainable agriculture. This finding aligns with machine-learning evidence suggesting that countries form clear structural clusters in several SDG dimensions [77].

Building on the results, the analysis underscores pronounced disparities in synergy contributions across income groups and regions from 2001 to 2023. High-income countries exerted the greatest influence in the economic dimension, primarily by driving global trade, investment, and technological dissemination. By contrast, low-income countries made more favorable contributions in environmental and social dimensions, benefiting from low initial baselines and achieving notable progress in areas such as child health, educational access, and resource-use efficiency. By contrast, high-income countries often make negative contributions to environmental and social SDGs, primarily due to persistently high carbon emissions and the near-saturation of key social indicators. Regionally, North America shows the strongest positive contributions to the economic dimension, followed by Europe, underscoring the central role of developed regions in driving economic globalization. In the environmental and social dimensions, however, developing regions, particularly Asia, Africa, and LAC, demonstrate stronger contributions. This study provides valuable insights to assist policymakers in formulating targeted strategies commensurate with the development stages and specific needs of different countries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411283/s1. Supplementary Materials include Table S1 and Figures S1–S40.

Author Contributions

Methodology, R.L. and Y.Z.; software, R.L.; validation, R.L.; formal analysis, R.L.; data curation, R.L.; writing, R.L. and Y.Z.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42430409, Y.Z.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, F.; Wang, H.; Tzachor, A.; Hidalgo, C.A.; Schandl, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.-Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.-G.; et al. The Disparities and Development Trajectories of Nations in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Song, S.; Lusseau, D.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, J. Bleak Prospects and Targeted Actions for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 2838–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Liu, J. Decoupling of SDGs Followed by Re-Coupling as Sustainable Development Progresses. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Wall, T.; Barbir, J.; Alverio, G.N.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Ramirez, J. Relevance of International Partnerships in the Implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Dong, J.; Gu, P.; Hao, Y.; Xue, K.; Duan, H.; Xia, A.; et al. Overlooked Uneven Progress across Sustainable Development Goals at the Global Scale: Challenges and Opportunities. Innovation 2024, 5, 100573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chau, S.N.; Dietz, T.; Li, C.; Wan, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Chung, M.G.; et al. Impacts of International Trade on Global Sustainable Development. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Costa, L.; Rybski, D.; Lucht, W.; Kropp, J.P. A Systematic Study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Interactions. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Bao, S.; Ren, J.; Xu, Z.; Xue, S.; Liu, J. Global Transboundary Synergies and Trade-Offs among Sustainable Development Goals from an Integrated Sustainability Perspective. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chau, S.N.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Dietz, T.; Wang, J.; Winkler, J.A.; Fan, F.; Huang, B.; et al. Assessing Progress towards Sustainable Development over Space and Time. Nature 2020, 577, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Guo, J.; Wang, Q. Impact of Foreign Aid on the Ecological Sustainability of Sub-Saharan African Countries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, S.; Mishra, A.K. Humanitarian Food Aid and Civil Conflict. World Dev. 2020, 126, 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Pan, A.; Fei, R. Three-Dimensional Heterogeneity Analysis of Climate Aid’s Carbon Reduction Effect. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-H.; Ries, J. Aid for Trade and Greenfield Investment. World Dev. 2016, 84, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, R.; Ghazalian, P.L. COVID-19 and International Food Assistance: Policy Proposals to Keep Food Flowing. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S.; McGowan, L. Constructing a Ladder of Transnational Partnership Working in Support of Marine Spatial Planning: Thoughts from the Irish Sea. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 126, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, R. Green Hydrogen Partnerships with the Global South. Advancing an Energy Justice Perspective on “Tomorrow’s Oil”. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1038–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Yin, J. Global Research on Carbon Footprint: A Scientometric Review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, C.-C.; Li, J. Structural Characteristics and Determinants of an International Green Technological Collaboration Network. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, C.K.; Ajibade, F.O.; Ajibade, T.F.; Kumar, P.; Fadugba, O.G.; Adelodun, B. The Impact of International Agreements and Government Policies on Collaborative Management of Environmental Pollution and Carbon Emissions in the Transportation Sector. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 114, 107930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najarzadeh, R.; Dargahi, H.; Agheli, L.; Khameneh, K.B. Kyoto Protocol and Global Value Chains: Trade Effects of an International Environmental Policy. Environ. Dev. 2021, 40, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.V.; Crespy, C.T.; Loess, K.H.; Renau, J.A. Western Hemispheric Trade Agreements and Sustainability: Lesson from Butterflies, Hummingbirds, and Salty Anchovies. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Villanueva, F.D.; Sarker, P.K.; Giessen, L.; Burns, S.L. How Do International Donors Influence Regional Environmental Governance? The Case of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty. Environ. Dev. 2025, 55, 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Raisolsadat, A.; Wang, X.; Van Dau, Q. Quantitative Assessment of The Group of Seven’s Collaboration in Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedercini, M.; Arquitt, S.; Collste, D.; Herren, H. Harvesting Synergy from Sustainable Development Goal Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23021–23028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, E.; Elsawah, S.; Ryan, M.J. A Review and Catalogue to the Use of Models in Enabling the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 340, 130803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T.; Comim, F. Measuring the Sustainable Development Goals: A Poset Analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Subedi, D.R.; Khatiwada, D.; Joshi, K.K.; Kafle, S.; Chhetri, R.P.; Dhakal, S.; Gautam, A.P.; Khatiwada, P.P.; Mainaly, J.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic Not Only Poses Challenges, but Also Opens Opportunities for Sustainable Transformation. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2021EF001996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, T.; Liu, B.; Fang, D.; Gao, Y. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Has Been Slowed by Indirect Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Commun. Earth Env. 2023, 4, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Takahashi, K.; Dai, H.; Liu, J.-Y.; Ohashi, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Matsui, T.; Hijioka, Y. Measuring the Sustainable Development Implications of Climate Change Mitigation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 085004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuldauer, L.I.; Thacker, S.; Haggis, R.A.; Fuso-Nerini, F.; Nicholls, R.J.; Hall, J.W. Targeting Climate Adaptation to Safeguard and Advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Shen, W.; Zhang, Z. Assessing Progress toward Sustainable Development in China and Its Impact on Human Well-Being. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shuai, C.; Chen, X.; Zhao, B. A Data-Driven Framework for Assessing Global Progress towards Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 60, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Puijenbroek, P.J.T.M.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Bouwman, A.F.; Ayeri, T.; Strokal, M.; Hofstra, N. Quantifying Future Sanitation Scenarios and Progress towards SDG Targets in the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 346, 118921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuc-Czarnecka, M.; Markowicz, I.; Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. SDGs Implementation, Their Synergies, and Trade-Offs in EU Countries—Sensitivity Analysis-Based Approach. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladini, F.; Betti, G.; Ferragina, E.; Bouraoui, F.; Cupertino, S.; Canitano, G.; Gigliotti, M.; Autino, A.; Pulselli, F.M.; Riccaboni, A.; et al. Linking the Water-Energy-Food Nexus and Sustainable Development Indicators for the Mediterranean Region. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Long, Y.; Shao, C. Spatiotemporal Variation and Regional Disparities Analysis of County-Level Sustainable Development in China. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yin, C.; Hua, T.; Meadows, M.E.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cherubini, F.; Pereira, P.; Fu, B. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the Post-Pandemic Era. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumilova, O.; Tockner, K.; Sukhodolov, A.; Khilchevskyi, V.; De Meester, L.; Stepanenko, S.; Trokhymenko, G.; Hernández-Agüero, J.A.; Gleick, P. Impact of the Russia–Ukraine Armed Conflict on Water Resources and Water Infrastructure. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, K.; Hu, Y.; Jiao, J.; Wang, S. Unveiling the Impact of Geopolitical Conflict on Oil Prices: A Case Study of the Russia-Ukraine War and Its Channels. Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 106956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Zhao, W.; Symochko, L.; Inacio, M.; Bogunovic, I.; Barcelo, D. The Russian—Ukrainian Armed Conflict Will Push Back the Sustainable Development Goals. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Pradhan, P.; Guo, H.; Fu, B.; Li, Y.; Bai, Y.; Chang, L.; Chen, Y.; et al. Spatio-Temporal Changes in the Causal Interactions among Sustainable Development Goals in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, W.; Meadows, M.E.; Fu, B. Finding Pathways to Synergistic Development of Sustainable Development Goals in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, F.; Dong, S.; Cheng, H.; Liang, L.; Xia, B. Spatial-Temporal Heterogeneity of Sustainable Development Goals and Their Interactions and Linkages in the Eurasian Continent. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; York, H.; Graetz, N.; Woyczynski, L.; Whisnant, J.; Hay, S.I.; Gakidou, E. Measuring and Forecasting Progress towards the Education-Related SDG Targets. Nature 2020, 580, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Fang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Zacarias, W.B.M.; Ioris, A.A.R. Evaluation of China’s Marine Sustainable Development Based on PSR and SDG14: Synergy-Tradeoff Analysis and Scenario Simulation. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 111, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Cao, S.; Du, M.; He, Z. Aligning Territorial Spatial Planning with Sustainable Development Goals: A Comprehensive Analysis of Production, Living, and Ecological Spaces in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; He, G.; Wang, C.; Yuan, J.; Cao, X. Spatial Variability of Sustainable Development Goals in China: A Provincial Level Evaluation. Environ. Dev. 2020, 35, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cai, W.; Lin, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. Nonlinear El Niño Impacts on the Global Economy under Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyzaguirre, I.A.L.; Iwama, A.Y.; Fernandes, M.E.B. Integrating a Conceptual Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals in the Mangrove Ecosystem: A Systematic Review. Environ. Dev. 2023, 47, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liang, D.; Sun, Z.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Bian, J.; Wei, Y.; Huang, L.; et al. Measuring and Evaluating SDG Indicators with Big Earth Data. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuso Nerini, F.; Mazzucato, M.; Rockström, J.; van Asselt, H.; Hall, J.W.; Matos, S.; Persson, Å.; Sovacool, B.; Vinuesa, R.; Sachs, J. Extending the Sustainable Development Goals to 2050—A Road Map. Nature 2024, 630, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z.; Bakshi, S. Determinants and Consequences of Sustainable Development Goals Disclosure: International Evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Morone, P. Economic Sustainable Development Goals: Assessments and Perspectives in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 354, 131730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Yu, K.; Xu, Z.; Xu, M.; Qu, S. Unveiling Complementarities between National Sustainable Development Strategies through Network Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 350, 119531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazneen, S.; Hong, X.; Ud Din, N.; Jamil, B. Infrastructure-Driven Development and Sustainable Development Goals: Subjective Analysis of Residents’ Perception. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 112931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.; Yu, L.; Chen, X.; Zhao, B.; Qu, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, J.; Miller, S.A.; Xu, M. Principal Indicators to Monitor Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 124015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y. Bundling Regions for Promoting Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.C.; Pandey, M. Highlighting the Role of Agriculture and Geospatial Technology in Food Security and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 3175–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham-Truffert, M.; Metz, F.; Fischer, M.; Rueff, H.; Messerli, P. Interactions among Sustainable Development Goals: Knowledge for Identifying Multipliers and Virtuous Cycles. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1236–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.J.; Saleem, M.; Misra, R.; Nguyen, N.; Mason, J. Reducing SDG Complexity and Informing Environmental Management Education via an Empirical Six-Dimensional Model of Sustainable Development. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Shu, K. The Coupling and Coordination Assessment of Food-Water-Energy Systems in China Based on Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, M.; Shams Esfandabadi, Z.; Zanetti, M.C.; Scagnelli, S.D.; Siebers, P.-O.; Aghbashlo, M.; Peng, W.; Quatraro, F.; Tabatabaei, M. Three Pillars of Sustainability in the Wake of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Waal, J.W.H.; Thijssens, T.; Maas, K. The Innovative Contribution of Multinational Enterprises to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Jato-Espino, D.; Castro-Fresno, D. Is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Index an Adequate Framework to Measure the Progress of the 2030 Agenda? Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P.; Thapa, P.; Putra, M.P.I.F.; Kropp, J.P. Building a Unified Sustainable Development Goal Database: Why Does Sustainable Development Goal Data Selection Matter? Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1278–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltruszewicz, M.; Steinberger, J.K.; Ivanova, D.; Brand-Correa, L.I.; Paavola, J.; Owen, A. Household Final Energy Footprints in Nepal, Vietnam and Zambia: Composition, Inequality and Links to Well-Being. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 025011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, E.K.; Ozturk, I.; Bekun, F.V.; Alhassan, A.; Gimba, O.J. Synthesizing the Role of Technological Innovation on Sustainable Development and Climate Action: Does Governance Play a Role in Sub-Saharan Africa? Environ. Dev. 2023, 47, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cui, C.; Dong, J.; Qu, A.; Shao, C. Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in Urban Agglomeration: Progress and Synergies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 116, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Pradhan, P.; Gao, S.; Su, C.; Skene, K.R.; Fu, B. Nonlinear and Weak Interactions among Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Drive China’s SDGs Growth Rate below Expectations. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 115, 107990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Ackom, E. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Driven Approach to Climate Action and Sustainable Development. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Shuai, C.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, B.; Qu, S.; Xu, M. Machine Learning-Enhanced Assessment of Urban Sustainable Development Goals Progress. Cities 2025, 158, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoiu, D.; Ionescu, G.H.; Cismaș, L.M.; Vochița, L.; Cojocaru, T.M.; Bratu, R.-Ștefan; Firoiu, D.; Ionescu, G.H.; Cismaș, L.M.; Vochița, L.; et al. Can Europe Reach Its Environmental Sustainability Targets by 2030? A Critical Mid-Term Assessment of the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebara, C.H.; Thammaraksa, C.; Hauschild, M.; Laurent, A. Selecting Indicators for Measuring Progress towards Sustainable Development Goals at the Global, National and Corporate Levels. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 44, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, W.; Hou, P.; Peng, K.; Deng, Y.; Wang, X. Changes in the Ecosystem Service Importance of the Seven Major River Basins in China during the Implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (2000–2015) and Sustainable Development Goals (2015–2020). J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 433, 139787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Rajagopalan, U.; Zyznarska-Dworczak, B. Sustainability Reporting as a Governance Tool for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Bibliometric and Content Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhathlaul, N.; Lakhouit, A.; Abdalla, G.M.T.; Alghamdi, A.; Shaban, M.; Alshahir, A.; Alshahr, S.; Alali, I.; Mutlaq Alshammari, F. Assessing Waste Management Using Machine Learning Forecasting for Sustainable Development Goal Driven. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S.; Öztürk, Ö.F.; Akkucuk, U.; Şaşmaz, M.Ü.; Çelik, S.; Öztürk, Ö.F.; Akkucuk, U.; Şaşmaz, M.Ü. Global Sustainability Performance and Regional Disparities: A Machine Learning Approach Based on the 2025 SDG Index. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).