Abstract

Biodiversity loss has been one of the most serious environmental issues on local and global scales. Enhancing people’s pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) to conserve biodiversity is crucial. Nature experiences are limited for urban residents, although nature experiences in childhood have been focused on as a key factor promoting PEBs. Therefore, we consider the role of urban parks in improving PEBs for urban residents towards sustainable cities and communities (Sustainable Development Goal 11). This study aims to elucidate the relationships among urban park use, PEBs, environmental attitudes, nature experiences in childhood, affective connections, community attachment, and ecosystem services by structural equation modeling, using survey data (n = 638) we collected from real urban park users in Osaka (Japan) in 2024. We have obtained three significant findings. First, urban park use for enjoying nature could promote PEBs, while nature experiences in childhood do not directly affect PEBs. Second, the effects of urban park use on PEBs begin to work when the frequency of urban park use exceeds around 2.2 days per week. Third, the perception of ecosystem services does not promote PEBs. We provide discussions concerning policy measures to increase urban park use based on the results. Note that the collected data may be potentially biased toward frequent park users.

1. Introduction

Our system of production and consumption imposes burdens on biodiversity on local and global scales. Our production and consumption patterns are among the drivers that hurt biodiversity due to land use changes and environmental resource overexploitation [1]. About 75% of land and 66% of ocean areas have been significantly converted for food production [2]. Humans have caused the sixth mass extinction through co-opting resources, fragmenting habitats, introducing non-native species, spreading pathogens, killing species directly, and changing the global climate [3]. The rate of species extinctions is tens to hundreds of times as high as the average across the past ten million years [2]. We urgently need to change our lifestyle to alleviate biodiversity loss.

Urban lifestyle tends to be separated from nature and has a negative impact on the environment without any consciousness. Urban consumption does not consider production sites that rely on environmental ecological resources [4,5]. Urban food consumption indirectly changes rural landscapes and damages biodiversity [6]. Urban life separated from nature leads to lower environmental attitudes and behaviors [7]. The extinction of nature experience in urban life prevents cultivating emotional connections with nature and conducting pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) [8,9]. Therefore, we must connect urban residents to nature to promote biodiversity conservation towards sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11).

In this study, we aim to elucidate the relationships among urban park use, PEBs, environmental attitudes, nature experiences in childhood, affective connections, community attachment, and perceptions of ecosystem services by applying structural equation modeling (SEM) to survey data (n = 638) collected from real urban park users in Osaka, Japan, in 2024. We focus on the role of urban parks in enhancing PEBs and investigate whether urban park use for enjoying nature can compensate for nature experiences in childhood, and how these mediating factors and perceived ecosystem services lead to PEBs. The study sites are three urban parks in Osaka, whose spatial characteristics and ecosystem services are also described. Based on the results of SEM, we discuss policy measures to increase the frequency of urban park use to encourage PEBs.

2. Background Research

Urban green spaces are significant substitutes for nature experiences to reconnect urban people with nature [8,9,10,11]. In this respect, using urban parks is crucial for promoting PEBs for urban people. Some studies have addressed the relationships between using urban parks and promoting pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. A positive relationship between park use frequency and relatedness to nature is identified [12]. Daily interactions with urban parks are induced by the values that prioritize the environment and are related to PEBs as well as the health and well-being of individuals [8]. Positive impacts of urban green space availability on perceived connection with nature and its subsequent influence on PEBs among urban residents are found in Nagpur city [13]. Nature experiences in adulthood, in addition to those in childhood, are effective in encouraging PEBs, implying that high-quality urban green spaces should be accessible in all life stages [14].

Urban parks have an indirect influence on PEBs. Recent studies emphasize emotional processes as important mediators. Emotional affinity toward nature—shaped by past and present experiences in natural environments—plays a motivational role in promoting pro-environmental commitment and behavior [15]. Consistent with this, a recent meta-analysis reports a moderate positive association between connection to nature and PEBs while emphasizing that more longitudinal and experimental research is needed to clarify causal mechanisms [16].

Urban parks may influence PEBs through nature connection and community and place attachment [17,18]. Community-based urban parks also help residents connect with their living places and enhance their sense of place attachment [19]. Place attachment to greenery is also significant in explaining PEBs of urban residents [20]. In contrast, the influence of emotion on PEBs remains a subject of debate in the literature [21], and thus empirical evidence on how emotional connections to nature and community attachment jointly shape PEBs in the context of everyday urban park use is still limited.

Perceptions of ecosystem services provided by urban parks offer another potential mediating mechanism. Previous studies have indicated that people’s perceptions, acquisition, and valuation of ecosystem services can influence the initiation and direction of their behaviors, as well as their support for environmental management and policy [22,23]. In urban settings, perceptions of recreational, cultural, and regulating services from green spaces have been linked to willingness to engage in conservation and other pro-environmental actions [24]. However, the causal relationships among park use, perceived ecosystem services, and PEBs—and the extent to which perceptions of ecosystem services mediate the effects of park use on behavior—have rarely been examined within an integrated causal framework.

Overall, existing research suggests that (i) childhood and adult nature experiences, (ii) affective connections to nature, (iii) community and place attachment, and (iv) perceptions of ecosystem services can all contribute to PEBs. Nevertheless, these previous studies address these factors independently, based on correlation analysis, and do not explicitly model the integrated system of direct and indirect paths linking urban park use to PEBs. In particular, few studies examine how park use for enjoying nature, environmental attitudes, emotional connections to nature, community attachment, and perceptions of ecosystem services interrelatedly to affect PEBs among urban park users.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Site

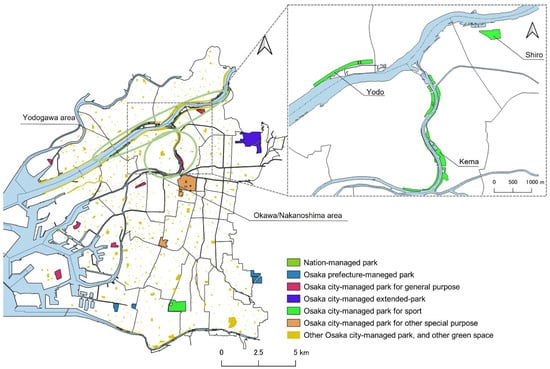

We target three urban parks in Osaka, a megacity in Japan: Yodogawa River Park with Nishinakajima and Juso areas (Yodo), Kema Sakuranomiya Park (Kema), and Shirokita Park (Shiro) (Figure 1). They are middle-sized parks along a river. According to the Osaka City Green Basic Plan, they are located in the Okawa/Nakanoshima or the Yodogawa area and are the core of green areas. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the parks.

Figure 1.

Map of the Target Urban Parks in Osaka.

Table 1.

Essential Characteristics of the Target Urban Parks.

3.2. Data Collection

We conducted an on-site questionnaire survey targeting park users to examine purposes of park use, their environmental attitudes, and their behaviors. We carried out the survey in two periods, from 24 April to 9 May 2024 and from 1 June to 22 June 2024. In each period, we collected data on four days per park, equally covering weekdays and Sundays/holidays. The survey was conducted between 12:00 and 17:00. We did not conduct the survey on rainy days because completing the questionnaire was difficult. In doing so, we obtained verbal informed consent from all respondents before conducting the questionnaire survey. We collected 695 responses. 57 responses were deleted for analysis because they contain missing data. The number of valid responses is 638.

Our questionnaire includes demographic data, items related to park use and ecosystem services, and factors related to pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs). We did not collect any information to specify a person and we anonymized all the data collected from the questionnaire. To assess PEBs, we referenced the Public Opinion Survey on Biodiversity conducted by the Japanese Cabinet Office in 2022, utilizing the response items from “Question 5: Status of Efforts for Biodiversity Conservation Activities.” The questions in the questionnaire are provided in Tables S1–S3 in Section S1 (see Supplementary Materials).

Questions related to affective connections with nature, environmental attitude, community attachment, and the frequency of nature experiences in childhood are drawn from previous studies. Affective connections with nature refer to the emotional connection, such as a sense of familiarity with nature, that is formed by the interaction with nature [25]. To measure environmental attitudes, we employ a shortened version of the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP), initially developed by Dunlap and Van Liere (1978) [26] and used by Hawcroft and Milfont (2010) [27]. Although the complete version of the NEP is preferable, we use the shortened version in this study, reducing questions to alleviate the burden on respondents. Community attachment is based on the Community Consciousness Scale [28]. For those unable to write independently, we collected the data through an interview using the same questionnaire.

3.3. Heatmaps

We create heatmaps based on four cultural services in each park, using the data from the questionnaire. In the questionnaire, we asked respondents which area in each park is important regarding recreational, spiritual, educational, and therapeutic services. Respondents indicated the areas on the map. The heatmaps are created by kernel density estimation using a geographical information system software, QGIS version 3.28.5. For the kernel density estimation, we set different sizes of search radius in the three parks because the map resolution differs among them: 35 m for Yodo, 75 m for Kema, and 20 m for Shiro. We provide weights on areas according to the importance for each respondent.

3.4. Analytical Model

We employ structural equation modeling (SEM) to elucidate the causal relations among urban park use, nature experiences, PEBs, and some other important factors. SEM has some advantages over the standard regression analyses [29,30]. First, SEM estimates all paths within an integrated system at the same time. Second, SEM captures indirect and mediating effects, clearly distinguishing direct and indirect paths within an analytical framework. Third, SEM can incorporate latent variables, which are composed of observed variables. Finally, SEM provides overall model fit indices that assess the appropriateness of the theoretical model for the data as a whole, which cannot be evaluated by estimating each equation separately.

SEM is effective in analyzing the relationships among human perceptions and behaviors. For example, van Dinter et al. (2022) [18] apply an SEM to the analysis of the relationships between personal and park characteristics, park use behavior, sense of place, and park visitors’ long-term subjective well-being, although the main aim is different from our study. Our developed model primarily relies on the existing model examining the influence of nature experiences in childhood on PEBs [25,31,32,33,34]. We posit that urban park use and perception of ecosystem services mediate the relations between nature experiences in childhood and PEBs. In this analysis, the effects of community attachment, cultivated through nature experiences in childhood [35], as well as the quantity and quality of urban green spaces [36], are controlled to ensure a comprehensive understanding of their influence on PEBs.

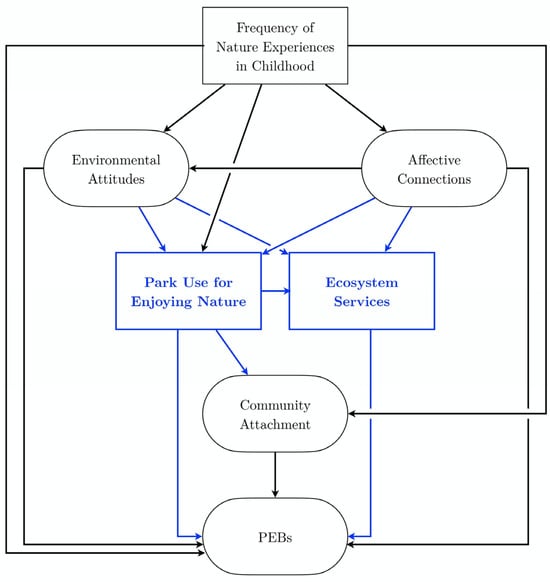

Figure 2 presents the structure of our causal relations in the SEM. The black arrows in Figure 2 represent causal relationships analyzed in previous studies. The blue arrows highlight hypothetical pathways through which park use for enjoying nature and ecosystem services exerts both direct and indirect effects on PEBs, which are the focus of this study. We need to conduct an empirical analysis regarding blue arrows. In what follows, we empirically investigate these complex, mutually interdependent effects among the variables shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of the SEM.

Ordinal variables such as age, travel time, and park-use frequency were converted into continuous variables by assigning the median value of each category. For example, respondents who reported being 40–49 years old were assigned 44.5 years as the median of that category. For variables whose highest category was open-ended, we used the following procedure. For age, the highest category was “70 years or older.” The next lower category, 60–69 years, was assigned 64.5 years, which is 4.5 years from both its lower and upper bounds. By analogy, respondents in the “70 years or older” category were assigned 74.5 years, using the same 4.5-year interval width from the lower bound of 70 years. We created a variable of park use for enjoying nature that considers quality and quantity. We focus on park use for enjoying ‘nature’ because our interests lie in promoting PEBs to tackle global environmental issues through urban park use. Equation (1) denotes the variable, park use for enjoying nature (PUE). The first part of the term on the right-hand measures the quality of park use for enjoying nature; the remaining part (Frequency of Park Use) measures the quantity of it.

Following the structure of the SEM above, the estimation equations of the SEM are presented below. The mathematical notations are shown in Table 2. Variables denoted by lowercase letters represent observed variables, whereas variables denoted by uppercase letters represent latent variables.

Table 2.

Mathematical Notations.

Structural Model:

Measurement Model for Latent Variables:

ATTITUDE:

CONNECT:

ATTACH:

PEBs:

Note that we captured perceptions of ecosystem services, which align with public goods, focusing on climate mitigation and habitat for creatures, for two reasons: first, PEBs are often driven by social motives rather than personal incentives; second, because we are interested in the role of urban park use in enhancing PEBs to tackle global environmental issues.

We estimated the SEM above by using maximum likelihood (ML) with robust standard errors in Stata/MP 18.

4. Results

4.1. Data in the Survey

We obtained 695 responses through the questionnaire and used 638 valid responses from individuals over 16 years old. Table 3 shows the attributes of respondents.

Table 3.

Summary of Respondents.

We asked respondents about the frequency of park use in the form of categorical variables ranging from first time (never used before) to almost every day. We converted this categorical variable to the number of visits per year, as shown in Table 4. PUE is significantly different among Yodogawa, Kema, and Shirokita Parks, with the 1% level based on a Levene’s test. PUE in Yodogawa Park (3.40) is obviously lower than that in Kema (8.41) and Shirokita (13.56) Parks. There is no significant difference between Kema and Shirokita Parks at the 10% level. We captured the perception of ecosystem services, which align with public goods, focusing on climate mitigation (ES1) and habitat for creatures (ES2) in Table 4. This is because PEBs are often driven by social motives—such as a desire to contribute to public goods or align with the community’s shared values—rather than personal incentives. Table 5 shows other latent variables with their response rates.

Table 4.

Summary of Responses to the Questionnaire Survey.

Table 5.

List of Latent Variables.

Table 6 summarizes all variables, including the mean, standard deviation, min, and max. Table 7 provides the correlation coefficients of all variables. No high correlation is found except for a few variables that compose the latent variables.

Table 6.

Summary of All Variables.

Table 7.

Correlation Coefficients of All Variables.

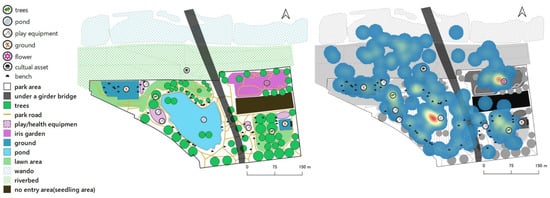

4.2. Created Heatmaps

Figure 3 shows a heatmap of therapeutic services in Shiro Park as an example. The numbers with each legend show the estimated values by Kernel density. They represent the estimated number of points per area. The colors are set so that higher values are colored red and lower values are colored blue. They are colored using a five-class equal interval classification. However, it is necessary to consider that this estimated value is also influenced by the amount of data and the weighting. Thus, we cannot compare the estimated values across cultural services straightforwardly. Trees and flowers in the pond are hot spots, although diverse areas are indicated as important places for the services by park users. All the heatmaps of the four cultural services (recreational, spiritual, educational, and therapeutic services) in the three parks (Yodo, Kema, and Shiro) are provided in Figures S1–S15 in Section S2 (see Supplementary Materials). Considering the overall characteristics of heatmaps, the recreation function was the most selected point, followed by the therapeutic function, and then the educational function. The spiritual function was the least selected point, although it was selected more in Kema Park than in Yodogawa and Shirokita Parks. Heatmaps of the four cultural services do not coincide, although some places are relatively significant in terms of the services. Diversity of the land use of urban parks is crucial for park users.

Figure 3.

Land Use Map and Heatmap (Sample).

4.3. Results of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

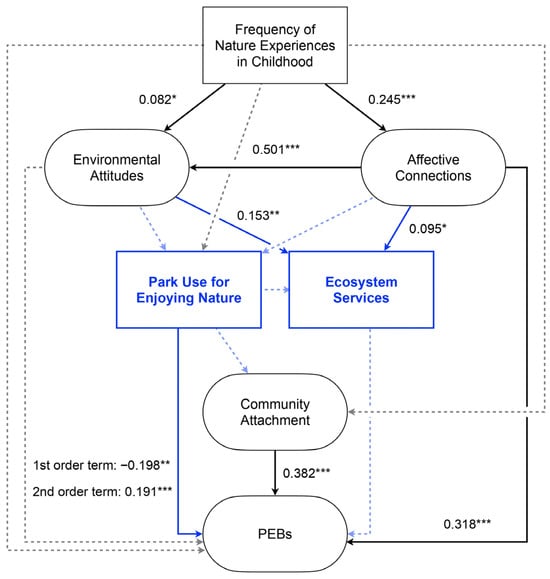

Figure 4 and Table 8 presents the estimation of the SEM. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.096. For RMSEA, values below 0.05 indicate a close fit, 0.05–0.08 a fair fit, 0.08–0.1 a mediocre fit, and 0.1 or higher a poor fit [29]. The comparative fit index (CFI) is 0.641. CFI should be ideally 0.95 or higher [30]. Thus, the goodness of fit is not very good, but not bad because it falls within the acceptable range. The sample size of our dataset (n = 638) can stably obtain parameter estimates. The model includes four latent variables and 113 parameters, yielding a parameter-to-sample ratio of approximately 1:6. This value falls within the commonly used range of 1:5 to 1:10 for power analysis [37].

Figure 4.

Graphical Results of the SEM. Note. ***: 0.01, **: 0.05, and *: 0.1.

Table 8.

Estimated Coefficients in the SEM.

The frequency of nature experiences in childhood has no effect on park use for enjoying nature, community attachment, and pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs). However, it has a positive impact on affective connections and environmental attitudes. In addition, the affective connections have positive effects on PEBs. These results suggest that the frequency of nature experiences in childhood has no direct effect on PEBs, but has an indirect effect on them through the mediating variables—the affective connections.

The frequency of nature experiences in childhood and affective connections fosters environmental attitudes. Park use for enjoying nature has a non-linear effect on PEBs: The squared term of park use is positive with statistical significance. The threshold at which the effect changes from negative to positive is 2.2 visits per week. The frequency of nature experiences in childhood, affective connections, or environmental attitudes does not influence park use for enjoying nature. This result implies that we must increase urban park use to enhance PEBs.

Affective connections and environmental attitudes influence the perception of ecosystem services, but the perception of ecosystem services does not affect PEBs. Some factors that enhance the perception of ecosystem services may exist, but they do not contribute to encouraging PEBs.

Previous studies suggested that urban green space fosters community attachment [19,20]. However, considering control variables, our results show that age influences community attachment only. To examine scale reliability, we calculate Cronbach’s (, , , and ). A value above 0.70 is considered acceptable, and 0.60 is considered moderate [38]. Thus, most of the values support the scale reliability of the latent variables.

5. Discussion

5.1. Impact of Urban Park Use on PEBs

It is critical that park use for enjoying nature independently promotes pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs). Urban park use is not a catalyst for enhancing the positive impact of nature experiences in childhood. Urban park use is a key to achieving SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), and the resultant PEBs of urban residents contribute to pursuing SDGs 13 (climate action) and 15 (life on land). Previous studies mention that nature experiences in childhood enhance environmental attitudes and PEBs in adulthood [25,39,40]. However, our study has found that nature experiences in childhood do not directly affect PEBs or urban park use for enjoying nature in adulthood. Therefore, urban park use for enjoying nature can compensate for the loss of nature experiences in childhood. Thus, we must consider how we can encourage park use for enjoying nature to promote PEBs (see Section 4.2).

We should also note that the effects of urban park use on PEBs begin to work when the frequency of urban park use exceeds a threshold. The threshold is estimated to be around 2.2 days per week. Nature experiences of urban residents are limited to a substantial extent. Thus, urban park uses are only nature experiences in their usual life. Frequent urban park use for enjoying nature can accumulate nature experiences for urban residents. Therefore, increasing the frequency of urban park use beyond the threshold is crucial to promote PEBs for urban residents.

5.2. How to Increase Park Use for Enjoying Nature

The results show that urban park use has the potential to enhance PEBs and that it becomes effective in promoting PEBs once park use frequency exceeds a threshold. This implies we need to increase the frequency of urban park use at least to encourage PEBs. Let us consider how to increase urban park use to enjoy nature for urban residents here. We should consider three critical factors with relevant references: nature orientation, perceived accessibility, and social norms. Although nature orientation is the most influential factor of park use, perceived accessibility and social norms are critical, particularly for infrequent and non-park users [12,41]. Thus, we consider how to augment these three factors in the following.

First, nature orientation assesses emotional, cognitive, and experiential relationships with nature [42,43], which promotes outside nature activities in parks. However, it seems challenging to increase nature orientation because it is rooted in the biophilia hypothesis of an inherent biological desire for nature [44]. Therefore, it may be better to focus more on enhancing perceived accessibility and developing social norms.

Second, we need to enhance perceived accessibility (shorten the psychological distance to parks) by improving park quality (changing land use within an urban park), making the neighborhood environment attractive [45], and dispersively allocating parks in an urban area rather than intensively [8]. Above all, it is worth considering altering the land uses of urban parks based on the created heatmaps (Section 3.2). Some places with specific park features are hot spots for real park users; thus, we should establish areas with specific features to increase the number of park users. Furthermore, the diversity of the land use in urban parks is also significant because hot spots are scattered over various land types. In addition, we can also consider reducing the physical distance to parks by arranging public transportation [46] and developing universal accessibility to parks with inclusive designs [47]. We should take a holistic approach to improve perceived park accessibility, using the multiple methods above. They may be ineffective if we separately implement them.

Third, forming a social norm to use parks frequently is a fundamental engine for increasing public use. Sia et al. (2023) [41] remark that social norms are crucial for infrequent and non-park users. Furthermore, Baur et al. (2014) [48] mention that they are crucial for all park users regardless of frequency. A social norm is formed by conditions in an individual’s surroundings, such as influential persons and fictional characters in the media [49]. For example, education plays a key role in sharing the value of urban park use in society. Children and students should be educated to understand the value. It might be a good policy intervention to provide influential persons such as movie stars, politicians, and social media influencers with pecuniary incentives to remark that going to urban parks is an imperative custom for people’s urban life. Social norms are influenced by intergenerational transmission and social networks [50]. In this context, one good option is to create comfortable and fun spaces, e.g., holding festivals and bazaars and establishing a safe playground for families to enjoy with their children, parents, and residents, which may promote intergenerational interactions and develop human connections in a social network.

We have discussed above how to increase urban park use, in general. However, it is critical to consider how to increase urban park use for enjoying nature. For example, many people enjoy plants and living creatures in Shiro Park because a famous iris garden has been established. Providing an urban park with natural areas is a potential option for easily experiencing nature. It is also significant to arrange natural areas into the zones of an urban park used for purposes other than enjoying nature. The arranged natural areas can encourage urban park users to enjoy nature unconsciously, which may induce them to use urban parks mainly to enjoy nature.

5.3. Impact of Perception of Ecosystem Services on PEBs

This study found that the perception of ecosystem services does not promote PEBs. This finding contrasts with previous studies that suggested the perception of ecosystem services enhances PEBs using the SEM framework [22,23]. There may be three reasons for this gap. First, the difference in analytical frameworks can explain this gap. The previous studies primarily focused on the relationship between the perception of ecosystem services and PEBs, but they failed to capture the causal relations. In contrast, our model captures the direction of causal paths from the perception of ecosystem services to PEBs, including relevant factors. There may be two reasons for the gaps between our results and existing literature. Second, our data possibly suffers from selection bias. The on-site survey likely targets frequent park users, whereas previous studies use online surveys or large-scale sampling to include non-park users as well as less frequent park users. Third, there are inherent limitations in operationalizing key concepts. Ecosystem services have multiple functions, yet our analysis focused on public goods type functions, such as climate mitigation and habitat provision. Dealing with the specific functions of ecosystem services may yield findings that differ from those of other studies.

To address these issues, it is required to explicitly incorporate individuals who do not use parks by broadening the range of the sampling framework and expanding both spatial and temporal scales. It would help mitigate selection bias and enable a more rigorous assessment of how the various functions of ecosystem services relate to PEBs and community attachment over time.

5.4. Urban Park Planning

We have discussed some measures to enhance PEBs by increasing urban park use in Section 4.2. In this context, we need to derive some implications for urban park planning from the holistic viewpoint.

First, education on the benefits of urban parks should be included in urban park planning policy to promote PEBs for urban people. Educating people on the value of urban park use and its ecological benefits to people is imperative for increasing urban park use. We can apply this type of education to all urban parks because it does not require physical changes. This education can make people psychologically closer to urban parks and create social norms to validate urban park use. We have some methods to educate people: education at schools, educational events for children in the park, and more information on urban parks through signs and free papers. Intergenerational interactions through local events can also play an educational role in boosting urban park use.

Second, planning urban parks spatially and physically is also essential for increasing urban park use and determining what people do in parks. This is because the characteristics of urban parks determine what people want to do in parks according to the created heatmaps. For example, setting up natural areas lets people enjoy nature and observe living creatures, which is related to cultural services. People will go to urban parks more frequently for this purpose. Spatial and physical improvements of urban parks may be costly. However, we can obtain the direct benefits of park use and environmental benefits by promoting PEBs for urban residents. We need to conduct a cost–benefit analysis in urban park planning.

Third, it is significant to take holistic urban park planning, including geographical features and accessibility to urban parks in a city. Urban parks should utilize original landscapes and geographical features like riverbanks, floodplains, and wetlands. They connect people to nature experiences in urban parks. Furthermore, accessibility to urban parks affects the frequency of park use. We need to consider and plan the locations of urban parks with public transportation in a city.

5.5. Limitations and Future Tasks

Let us discuss some limitations of this study from a future study perspective. First, the data collected on-site tend to be biased. We collected data on park use through an on-site survey in the megacity of Osaka. It is well known that on-site surveys may bias empirical results due to sampling bias because the sampled data do not represent urban residents who do not use urban parks. Note that the data may contain a non-response bias. We should have considered how to count non-responses in the on-site survey. Furthermore, additional data collection from cities of different sizes is required because the role of urban parks in compensating for nature experiences in childhood may differ depending on city size. In future studies, we want to expand the target respondents and time scale.

Second, we should collect data on the frequency of visits to urban parks in the questionnaire more elaborately. This study does not capture the frequency of visits to urban parks in the categories of park use purposes. However, using the estimated variable (Equation (1)), our findings indicate that the distinction of the purposes is crucial for promoting PEBs because park use for enjoying nature causes PEBs. Thus, in a future study, we must obtain data on park visit frequency separately in the categories of park use purposes.

Third, it is important to investigate the impacts of urban park characteristics on urban park use. The analytical framework of SEM does not capture the impacts of urban park characteristics, such as the size of green spaces, the length of waterfront, the presence of biotopes, and the installation of promenades, among others. In addition, cultural characteristics that are specific to Japan also have an impact on urban park use. These variables may significantly impact how urban residents utilize urban parks. It will be important to investigate and compare the impacts of urban park characteristics on a global scale because of substantial variations in urban parks across the country.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we elucidate the relationships among urban park use, pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs), environmental attitudes, nature experiences in childhood, affective connections, community attachment, and ecosystem services by structural equation modeling (SEM), using survey data (n = 638) that we collected from real urban park users in the target three parks in Osaka (Japan). We consider the role of urban parks in promoting PEBs and investigate whether urban parks substitute for nature experiences in childhood and how urban park use leads to PEBs.

We have obtained three crucial findings. First, urban park use for enjoying nature has the potential to enhance PEBs regardless of nature experiences in childhood. Nature experiences in childhood do not directly affect PEBs, although many studies have mentioned that they are significant in promoting PEBs. Urban park use can compensate for the loss of nature experiences. Second, the effects of urban park use on PEBs begin to work when the frequency of urban park use exceeds a threshold, around 2.2 days per week. The relationship between urban park use and PEBs is non-linear. Third, the perception of ecosystem services does not influence PEBs. This finding contrasts with some previous studies because their analytical framework does not necessarily capture the causal relation.

There are some implications for theoretical development. First, using urban parks to enjoy nature can make urban people pro-environmental if they have nature experiences in childhood. Urban park use for enjoying nature in adulthood may compensate for nature experiences in childhood that urban people have currently been losing. Second, the frequency of urban park use is effective in encouraging PEBs, as is the accumulation of nature experiences in childhood. It is not until the frequency exceeds a certain threshold that urban park use becomes effective in promoting PEBs. Third, perceptions of ecosystem services may not hold in urban areas. It may be difficult for urban residents to perceive specific ecosystem services in urban developed areas, even including parks. We cannot deny the positive effects of the perception of ecosystem services on PEBs in general.

Note that the collected data may be biased toward frequent urban park users. The sites are limited to the Osaka megacity in Japan. We should have collected additional data, such as the frequency of park visits by park use purpose. Therefore, we need to randomly cover all urban residents, expand the investigation to other sites worldwide, and refine the survey items to more precisely elucidate causal relationships between urban park use and PEBs. Experimental approaches should be considered, such as matching estimation methods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411267/s1. Section S1. Questionnaire. Section S2. Created Heatmaps.

Author Contributions

A.A.: Research design; Making a questionnaire survey; Revision of a questionnaire survey; Data collection; Data analysis; Interpretation; Visualization; Drafting and editing; Revision of manuscript; Review of manuscript; making supplementary materials. K.M. (Koichiro Mori): Data analysis; Interpretation; Visualization; Drafting and editing; Revision of manuscript; Review of manuscript; Corresponding author. K.M. (Kyohei Matsushita): Data analysis; Interpretation; Visualization; Drafting and editing; Revision of manuscript; Review of manuscript. J.H.: Data analysis; Interpretation; Visualization; Review of manuscript. K.F.: Research design; Making a questionnaire survey; Revision of a questionnaire survey; Interpretation; Review of manuscript; Project management and supervision; Fundraising. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the sub-project S-21-3, “Interaction between value-behavior-culture and biodiversity” (JPMEERF23S12130), included in the research project S-21, “Development of an Integrated Assessment Model linking Biodiversity and Socio-Economic Drivers, and its Social Application” (PMEERF23S12100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study in accordance with the regulations of the Ethics Review Committee at Shiga University, which stipulate that ethical review is not required if the data are already anonymized and if the subjects cannot be identified by any means. For further details, please refer to: https://www.shiga-u.ac.jp/research_cooperation/research_active_branch/scholar_ethics/research_ethics_committee/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Brondizio, E.S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J. Humans are driving one million species to extinction. Nature 2019, 576, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnosky, A.D.; Matzke, N.; Tomiya, S.; Wogan, G.O.U.; Swartz, B.; Quental, T.B.; Marshall, C.; McGuire, J.L.; Lindsey, E.L.; Maguire, K.C.; et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 2011, 471, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.L. Strengths and Weaknesses of Common Sustainability Indices for Multidimensional Systems. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Christodoulou, A. Review of sustainability indices and indicators: Towards a new City Sustainability Index (CSI). Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2012, 32, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Mansur, A.V.; Ascensão, F.; Colbert, M.; Crossman, K.; Elmqvist, T.; Gonzalez, A.; Güneralp, B.; Haase, D.; Hamann, M.; et al. Research gaps in knowledge of the impact of urban growth on biodiversity. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, D.; Collé, A.; Randler, C. Urban versus rural? The effects of residential status on species identification skills and connection to nature. People 2021, 3, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Koyanagi, T.F.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Urban residents’ perceptions of neighbourhood nature: Does the extinction of experience matter? Biol. Conserv. 2016, 203, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R. Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Yamaura, Y.; Aikoh, T.; Shoji, Y.; Kubo, T.; Gaston, K.J. Reducing the extinction of experience: Association between urban form and recreational use of public greenspace. Landsc. Urban. Plann. 2015, 143, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Fuller, R.A.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Shanahan, D.F. Opportunity or orientation? Who uses urban parks and why. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoti, S.A.; Dhyani, S.; Sahle, M.; Kumar, P.; Saito, O. Exploring the Nexus between Green Space Availability, Connection with Nature, and Pro-Environmental Behavior in the Urban Landscape. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heezik, Y.; Freeman, C.; Falloon, A.; Buttery, Y.; Heyzer, A. Relationships between childhood experience of nature and green/blue space use, landscape preferences, connection with nature and pro-environmental behavior. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2021, 213, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Liu, Z.; Pan, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Wu, J. How do different types and landscape attributes of urban parks affect visitors’ positive emotions? Landsc. Urban. Plann. 2022, 226, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dinter, M.; Kools, M.; Dane, G.; Weijs-Perrée, M.; Chamilothori, K.; van Leeuwen, E.; Borgers, A.; van den Berg, P. Urban Green Parks for Long-Term Subjective Well-Being: Empirical Relationships between Personal Characteristics, Park Characteristics, Park Use, Sense of Place, and Satisfaction with Life in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, M.; Tabrizi, A.M.; Bauer, N.; Kienast, F. Place attachment through interaction with urban parks: A cross-cultural study. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2021, 61, 127103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A.; Dasgupta, R. Pattern of place attachment and pro-environmental behavior towards green infrastructure. GeoJournal 2024, 89, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, J.M.; Desrochers, J.E. Can positive and self-transcendent emotions promote pro-environmental behavior? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Kadoya, T.; Ueichi, H.; Takamura, N. Effects of the awareness of ecosystem services on the behavioral intentions of citizens toward conservation actions: A social psychological approach. Jpn. J. Conserv. Ecol. 2014, 19, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-T.; Liu, J.-M.; Borazon, E.Q. Evaluating the effect of perceived value of ecosystem services on tourists’ behavioral intentions for Aogu Coastal Wetland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asah, S.T.; Guerry, A.D.; Blahna, D.J.; Lawler, J.J. Perception, acquisition and use of ecosystem services: Human behavior and ecosystem management and policy implications. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Sparks, P. Engaging with the natural environment: The role of affective connection and identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The new environmental paradigm. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawcroft, L.J.; Milfont, T.L. The use (and abuse) of the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimori, M.; Okamoto, T.; Kato, J. Development of the short version of the Community Consciousness Scale. Jpn. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 53, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model fit and model selection in Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Deng, J.; Deng, X.; Li, J. Empathy with nature promotes pro-environmental attitudes in preschool children. PsyCh J. 2024, 13, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Fornara, F.; Carrus, G. Predicting pro-environmental behaviors in the urban context: The direct or moderated effect of urban stress, city identity, and worldviews. Cities 2019, 88, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Profice, C.C.; Collado, S. Nature experiences and adults’ self-reported pro-environmental behaviors: The role of connectedness to nature and childhood nature experiences. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M.; Lekies, K.S. Nature and the life course: Pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism. Child. Youth Environ. 2006, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, M.; Muneda, M.; Shinohara, J.; Jinbo, K.; Shirai, T. The Effect of Community-based Nature Experience Activities for Junior High School Students on Changes in Place Attachment and the Relationship between Place Attachment and Behavioral Intentions: Focus on Minamiboso Studies. Jpn. Outdoor Educ. 2024, 27, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A.; Eder, R. The influence of green space on community attachment of urban and suburban residents. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.W.; Aspinall, P.; Montarzino, A. The childhood factor: Adult visits to green places and the significance of childhood experience. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVille, N.V.; Egan, P.A.; Goldberg, J.H.; Cramer, L.A.; Anderson, C.B. Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, A.; Tan, P.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Er, K.B.H. Use and non-use of parks are dictated by nature orientation, perceived accessibility and social norm which manifest in a continuum. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2023, 235, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. The NR-6: A new brief measure of nature relatedness. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K. Psychological park accessibility: A systematic literature review of perceptual components affecting park use. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Li, X. Public transportation and the spatial inequality of urban park accessibility: New evidence from Hong Kong. Transp. Res. D Trans. Environ. 2019, 76, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.C.; Cosco, N.G. What makes a park inclusive and universally designed? A multi-method approach. In Open space: People Space; Thompson, C.W., Travlou, P., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.W.; Tynon, J.F.; Ries, P.; Rosenberger, R.S. Urban parks and attitudes about ecosystem services: Does park use matter? J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2014, 32, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tankard, M.E.; Paluck, E.L. Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change. Soc. Iss. Policy Rev. 2015, 10, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.X.D.; Goodman, N.D.; Goldstone, R.L. The emergence of social norms and conventions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).