Abstract

Over the last 40 years, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has experienced economic growth that has driven urbanization and infrastructure improvements. However, this has also led to high resource use and poor planning, exacerbating climate challenges and underscoring the need for international cooperation. Given the substantial energy use associated with buildings, sustainable global building standards have been developed. Saudi Vision 2030 encourages sustainable practices in energy, housing, and water by adopting green building standards to guide environmentally friendly initiatives. This study provides an overview of the current status of green building rating systems in KSA and examines the principal obstacles faced during their implementation. Utilizing importance-performance analysis (IPA), the study identifies and evaluates strategies to advance green building ratings, drawing upon survey data from diverse stakeholders. Major barriers include low awareness across the public and private sectors and technical challenges such as a shortage of qualified professionals, limited information, and unreliable resources. The strategies proposed aim to establish clear standards for sustainable construction and promote targeted awareness campaigns with industry leaders and government, highlighting the long-term environmental and financial advantages of green buildings. Identifying these barriers and evaluating interventions will help to advance green building rating systems and sustainability in KSA and worldwide.

1. Introduction

The continuous consumption of world resources without proper planning has led to the planet facing severe consequences at an accelerating rate, including global warming, resource depletion, and environmental degradation [1]. Nowadays, on emergent grounds, world leaders are making concerted efforts to slow down the consumption of natural resources [2]. Recently, researchers have highlighted the role of the construction sector in this crisis; in [3], it was mentioned that the building sector is responsible for 39% of all CO2 emissions, and more than a third of the usage of total energy and CO2 emissions is a result of the building sector in the developed and developing nations [4]. This makes it a primary target for mitigation strategies. The pressure from developed countries worldwide to reduce carbon emissions is also growing. Reference [5] pointed out that new rules, such as updated EU guidelines, now require a transition to a building stock with no emissions by 2050. This makes it very important for countries to use strong assessment techniques. Scientists believe that ecological damage has reached, or is nearing, a point of no return. Given the growing demand and rising oil prices, world-leading economies are seriously considering shifting to renewable energy sources to reduce production costs and simultaneously slow greenhouse gas emissions, thereby controlling global warming [6]. Saudi Arabia, for example, has set ambitious targets to cut greenhouse gas emissions, including the 2060 Zero-Carbon target [7]. The building sector is a primary contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and can also be viewed as an enabler of a more sustainable built environment [8].

According to [9], Green Building is a concept that focuses on minimizing a building’s environmental impact throughout its lifecycle. In contrast, in [10] green buildings were considered as tools that improve environmental efficiency and health while minimizing adverse effects on human health. According to [11], it is a practice aimed at creating a structure that is environmentally and resource-efficient throughout its entire life cycle. These features can all be identified using a rating system. Ref. [12] stated that a building rating system is a framework used to assess the environmental performance and sustainability of buildings. According to [13], building rating systems are tools that classify buildings based on environmental sustainability, building efficiency, and user health.

In addition to their environmental benefits, green buildings also provide health and economic advantages. Research has shown that certified buildings with a rating system can enhance patient treatment and sleep quality [14]. Maintaining a high standard of indoor environmental quality is essential for promoting health and well-being. This is particularly significant because people who work in offices, stores, and healthcare settings spend a lot of time indoors—up to 90% of their time, as highlighted by [15]. Furthermore, workplaces with green elements and adequate ventilation can improve cognitive function by 101% and increase employee productivity by up to 8% [16]. For example, the transition to a green workplace at the CH2 building in Melbourne has led to a notable 10.9% increase in staff productivity [17]. Implementing a green rating system has also been shown to yield direct financial benefits. The Construction Marketplace Smart-Market Report reveals that commercial green buildings have achieved 8–9% reductions in operating costs, a 7.5% increase in building value, and a 6.6% increase in return on investment. As indicated by the Greening of Corporate America Smart Market Report, commercial green buildings experience a 3.5% increase in occupancy and a 3% increase in rent [18].

The purpose of implementing green building rating systems worldwide is to promote sustainable practices in buildings, as they significantly impact the global environment. Implementing green building ideas still requires significant adjustments at many points in the process, including design, construction, and daily operations. Due to these changes, new materials, methods, and approaches are necessary that differ from the old ones. People accustomed to traditional methods often resist adopting new, more environmentally friendly approaches. The hesitation among stakeholders to adopt this practice stems from concerns about its risks, the initial cost of adaptation, and unfamiliarity with the practice itself. Overcoming these barriers is essential to successfully implementing environmentally friendly building principles [19].

Saudi Arabia faces multiple obstacles that make it challenging for the country to fully utilize and implement these technologies [20]. A primary factor is the limited awareness and understanding of green building concepts and their advantages. Another barrier is the scarcity of experts and professionals in green building within the kingdom [21]. These experts are crucial since they help to guide and inform the use of green construction principles. In addition, the high initial expenditures of adding green building features and technologies are also a substantial barrier in Saudi Arabia.

Regionally, there is also resistance to change and a lack of readiness to make sustainability a top priority in the building business. Additionally, obtaining the necessary government permissions and clearances to use green building methods is challenging [22]. According to a 2014 report by the U.S. Green Building Council, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) had 866 LEED projects as of 2014, with only 106 certified. LEED is an internationally acknowledged green building certification program developed by the U.S Green Building Council [23]. The UAE had the most registered projects (650), followed by Qatar (88 registered, 13 certified) and Saudi Arabia (83 registered, 4 certified). There were fewer developments in Oman, Bahrain, and Kuwait. In 2014, only 4 of the 106 approved buildings were from Saudi Arabia, despite the country being a major player in the construction industry. However, the adoption of green buildings has been rising in the GCC. By 2023, Saudi Arabia had 1816 registered projects, of which 1162 were certified. The UAE had 2275 registered projects, but only 569 were certified [9]. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are important players in LEED projects that support the Sustainable Development Goals. The UAE is ahead in renewable energy regulations, whereas Saudi Arabia is working on its Vision 2030 [24]. In 2023, the U.S. Green Building Council ranked Saudi Arabia sixth, reflecting its dedication and goals towards sustainability [25].

The primary objective of this research is to identify and evaluate critical barriers to the adoption of Green Building Rating Systems (GBRS) in Saudi Arabia’s construction industry and systematically prioritize strategic interventions to overcome them. Ultimately, comprehending these obstacles and assessing the efficacy of proposed solutions will further promote the adoption of GBRS and bolster sustainability initiatives both within Saudi Arabia and on a global scale. The utilization of GBRS can assist projects in improving their environmental performance, elevating efficiency, and decreasing lifecycle costs. To achieve these objectives, the study seeks to answer two questions:

- What are the different kinds of barriers that act as a blockade while adopting GBRS in Saudi Arabia?

- How do Saudi construction industry stakeholders prioritize specific strategies to overcome these barriers in terms of importance and effectiveness?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a global literature review and identifies key barriers to the adoption of the green building rating system. Section 3 provided the techniques and methodologies adopted in this research, including the survey design and the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) framework. Section 4 presents the results of the data analysis. Section 5 discusses the findings of this research and compares them with the previous studies and the specific Saudi environment. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing the main contributions and offering policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews the theoretical background of sustainable construction. It first examines global rating systems and the barriers identified by various researchers that hinder the adoption of green rating systems, then narrows the focus to the specific context and challenges within the Saudi Arabian construction industry.

2.1. Global Perspective

The growing emissions in the building and construction industry highlight the importance of adopting a three-pronged approach to reduce energy consumption in buildings, mitigate carbon emissions from the power sector, and implement materials strategies that minimize carbon emissions throughout their lifecycle [26]. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has stated that to achieve a net-zero carbon building stock by 2050, direct building CO2 emissions need to decrease by 50% and indirect building sector emissions by 60%. This can be achieved by cutting power generation emissions by 2030. These efforts would need to see building sector emissions decline by around 6% per year from 2020 to 2030 [27]. Since the ultimate objective of green building rating systems is to slow the rampant consumption of natural resources and drive the trend towards sustainable building across different regions of the world, all governments, in their capacity, are being urged by international organizations to adopt sustainable building practices and share achievements to review progress. All responsible countries review existing building practices and develop green building ratings based on local climate to share their contributions towards a sustainable building drive. Globally, different sustainable building standards could be identified by their standard naming convention, like “Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)” in the USA, “Building Research Establishment’s Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM)” in the UK, “the comprehensive assessment system for building environmental efficiency (CASBEE)” in Japan, “Qatar Sustainability Assessment System (QSAS)” in Qatar, and “Estidama Pearl Rating System (PRS)” in Abu Dhabi. These certification systems provide a concise framework for categorizing green building elements and offer global verification that a building was designed, built, and operated in accordance with sustainable standards. The key feature of the LEED standard is that it can be applied to all types of buildings (i.e., residential, commercial, and, more recently, healthcare facilities). LEED also covers both new and existing buildings. Due to local limitations, some indicators of the LEED certification system are not suitable for use in other countries [28].

The adoption of green building rating systems worldwide has encountered several barriers, hindering their widespread implementation. In the context of China, the identified barriers include the high additional expense associated with green building, the acknowledgment of the importance of sustainable development, the level of international influence, the customary approach to conducting interdisciplinary research, and the lack of cost-efficient technologies [29]. In 2014, research in the United States identified several barriers to the adoption of green buildings, with costs and expenses associated with implementing green building practices being the most commonly reported hindrances [30].

Additionally, numerous researchers have highlighted that a lack of awareness of incentive policies contributes to industry players’ reluctance to adopt green building rating systems. This low awareness is a key factor preventing widespread adoption of sustainable building practices within the industry [31]. In 2016, Ref. [32] conducted a study that identified physiological, social, and economic factors as barriers to the adoption of the green building rating system. Overall, these obstacles were methodically categorized into five distinct categories: barriers related to government, barriers related to people, barriers related to knowledge and information, barriers related to the market, and barriers related to cost and risk [33].

Additionally, several solutions have been proposed to overcome these barriers and promote the global adoption of green building rating systems. These solutions include passing laws and providing incentives to encourage adoption, collaborating with research institutions and businesses to study the benefits of green building practices, policies, and regulations for green industrial development, government co-funding and incentives for training and technologies, and establishing a proper project management framework [34]. In addition, increasing local research and quantification of metrics specific to different regions can help better understand and optimize the design of green building practices for each region’s climate conditions. Additionally, practitioners and stakeholders need access to knowledge and resources regarding the barriers and solutions to adapting green building rating systems [35], which will enable them to make informed decisions, overcome barriers, and ultimately achieve sustainable development in the construction industry.

2.2. Saudi Arabia Construction Industry

Over the past four decades, Saudi Arabia has experienced remarkable growth, particularly in the construction sector. Urbanization has driven economic development as people move to cities for better living and jobs. This has increased demand for housing, development, and energy. The expansion of the Saudi Construction Market is mainly fueled by Vision 2030 national development plan, which aims to diversify and privatize the Kingdom’s economy. The Neom Future Cities, Qiddiya Entertainment City, and the Red Sea Project are all part of this proposal [36]. A 2022 report from Mordor Intelligence states that Saudi Arabia is engaged in over 5200 projects valued at $819 billion. These projects account for more than one-third of all ongoing projects in the GCC region [37]. Due to rapid urbanization, the Kingdom faces significant challenges in achieving sustainable urban development and implementing green building initiatives. To address these issues, the government and other interested parties are advocating for laws that promote sustainable development, such as initiatives to make cities greener and incentives for the construction of green buildings [38]. In addition, the use of rating systems such as LEED and BREEAM helps reduce the construction sector’s environmental footprint and sets benchmarks for sustainable practices, as noted by Romano [39].

Adopting rating systems can establish performance benchmarks and guidelines for sustainable construction, cultivating a culture that values environmental responsibility. Saudi Arabia may address these challenges by incorporating sustainable practices into its urban development plan and by collaborating with other countries to share achievements and monitor progress [40]. The Kingdom initiated the “Future Saudi Cities” project to address the challenges posed by rapid urbanization [41]. The goal is to build cities that are environmentally sustainable with high-quality infrastructure. This project aims to strike a balance between expansion and environmental protection, aligning with global sustainability goals. The Ministry of Municipalities and Housing in Saudi Arabia has developed local grading systems called Mostadam that promote sustainable construction and align with Saudi Vision 2030 [42,43]. Ref. [44] A comparison of the Mostadam and LEED systems within the Saudi market revealed that, in addressing Saudi Arabia’s unique environment, Mostadam is superior to LEED. Ref. [45] Conducted research into how people in Saudi Arabia feel about green rating systems, where they found that 61.6% of respondents expressed willingness to use Mostadam as a rating system for their building to align with Saudi Vision 2030. Similarly, Ref. [46] conducted a study on regional perspectives, primarily concentrating on energy conservation, material reduction, and pollution control. Although the conclusion does not apply to all construction types, this research identified higher costs, a lack of technologies, and a shortage of skilled labor as major barriers. The study concluded that aligning green initiatives with business strategies is the only way to deal with these obstacles.

A review of previous studies reveals that most have primarily focused on the barriers to adopting the green rating system globally in the construction industry. In contrast, this research focuses only on Saudi Arabia’s construction sector. To ensure the survey results are relevant, only respondents from the Saudi construction industry were asked to complete the survey, as they can provide a detailed analysis of the significance of these barriers and examine their underlying causes. Additionally, it aims to identify and prioritize potential solutions to address these barriers within Saudi Arabia’s construction industry.

3. Methodology

This section outlines the research design, data collection, sample size determination (calculated using Cochran’s formula), and the application of Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) as the primary analytical tool.

3.1. Research Design

The research began by reviewing previous studies to identify barriers to implementing green building rating systems across various construction industries and to explore potential solutions to overcome them. To identify these barriers, the author used major academic databases, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus. Merging these databases provided bibliographic information that boosted academic publication. The search strategy utilized specific keywords such as “green buildings,” “green rating systems,” “implementation barriers,” and “Saudi Arabia construction industry.” The efforts were then narrowed down to reviewing the related literature specifically in Saudi Arabia’s construction industry. This literature review was crucial, as it helped to identify 10 key barriers and 8 potential solutions. Later, these barriers were categorized using a thematic analysis methodology.

Afterward, these barriers and solutions were analyzed using multiple analytical tools and techniques. Once this analysis was completed, a survey questionnaire was prepared, targeting practitioners across various groups, including industry professionals, government organizations, and commercial sectors, as the unit of analysis. The survey was distributed via the snowball technique to ensure it reached a broader audience across the public and private sectors of Saudi construction. To ensure data integrity, the survey was designed in accordance with ethical research standards, and data were kept private; it was promised that they would be destroyed after the research was conducted. This encouraged the respondent to provide honest feedback, especially for organizational and policy barriers, without any fear. The quantitative survey approach is selected for this study, as it aligns with the methodologies of [19,30], which successfully employed this approach in their respective studies, recognized as studies on green building barriers in Ghana and Malaysia.

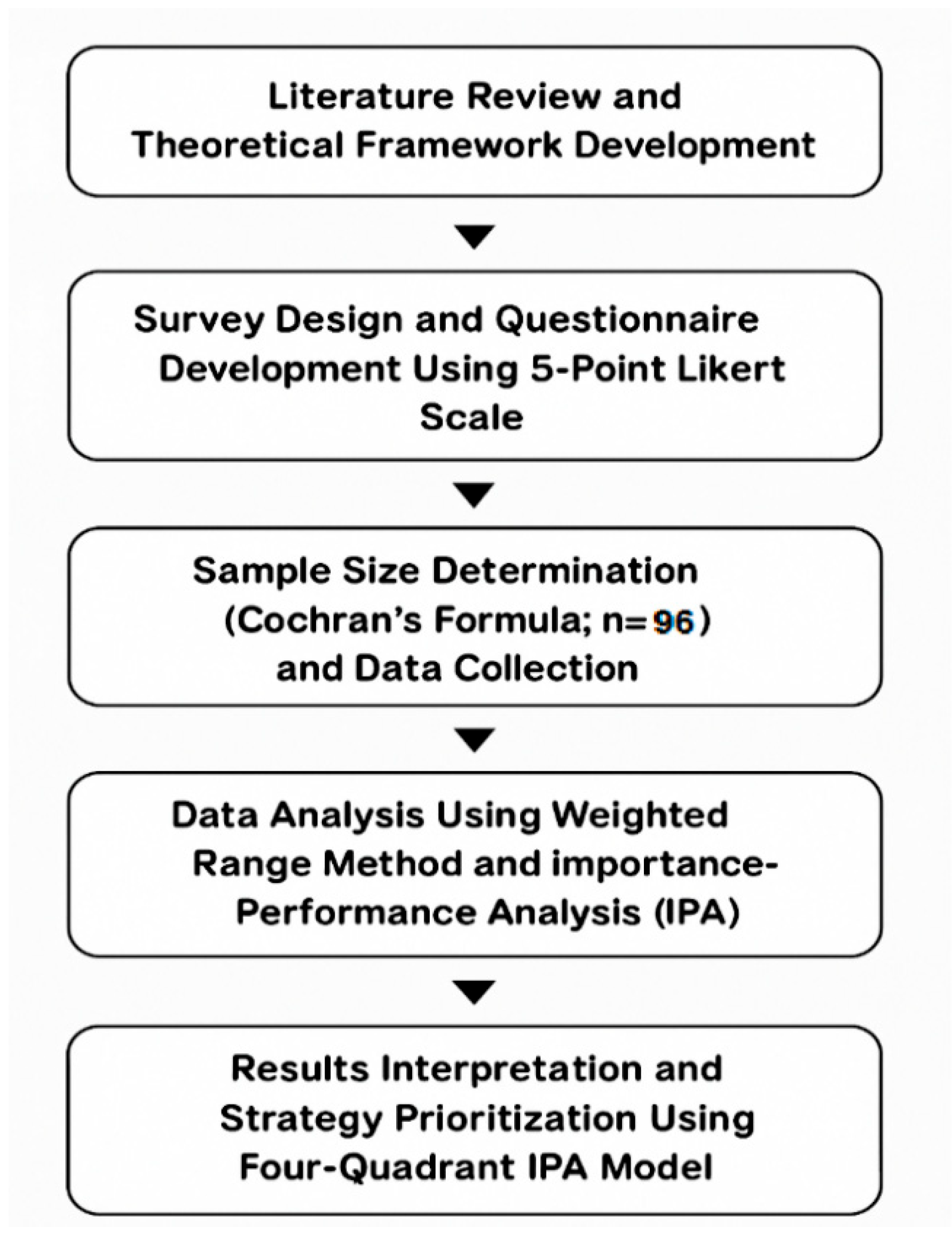

The survey was used to evaluate the criticality of the identified barriers and to assess the importance and effectiveness of the proposed strategies. An analysis of the survey data was then conducted, and the results were discussed to develop conclusive arguments. Figure 1 illustrates the research methodology flowchart.

Figure 1.

Research methodology.

3.2. Data Collection

Through an extensive review of current practices and consultation with experts in the field, this research aims to identify the most significant barriers and propose critical strategies to address them. Surveys with construction experts, including executives and field engineers with 7–20 years of experience, identified barriers and solutions. The research aims to survey various public and private organizations. The questionnaire targets multiple segments, each with specific questions to elicit participants’ views. Research objectives involve designing questions to explore barriers to implementing the green building rating system and proposing solutions. Data collected via surveys from the target audience is compiled and evaluated to inform the conclusion.

As the targeted audience comes from diverse backgrounds and occupations, they are expected to have varying perceptions of both obstacles and strategies; thus, most of the questionnaire used a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” for each proposed statement. The Likert scale is one of the most widely used instruments in research, developed by Rensis Likert [47]. To analyze responses more effectively, each Likert scale point was assigned a numerical value. Table 1 shows the categories, scale values, and weighted ranges used in the analysis.

Table 1.

Five-point scale and weights for evaluating barriers.

3.3. Population and Sampling Techniques

Since the size of the target population was unknown, this study estimated the minimum sample size using Cochran’s formula from ‘Sampling Techniques’ [48], as shown below:

- Z = Z value (1.96 used for 95% confidence level);

- P = Percentage picking a choice, expressed as a decimal (0.5 used for sample size needed);

- C = confidence interval, expressed as a decimal (0.1 used for ±10% margin of error)

Therefore, a sample size of 96 has been selected. Survey distribution was conducted directly with a carefully selected audience to obtain the most accurate and valuable input.

3.4. Data Analysis Tool

In the field of research work, there are numerous methods for ranking data, such as the Relative Importance Index (RII); however, this study decides to adopt the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) model, as IPA not only does data ranking but also visualizes the relationship between the importance of strategy and its effectiveness. The proposed strategies are prioritized using the IPA model, which assesses their importance-effectiveness ratio to highlight the high-priority strategies decision-makers should focus on. The model was derived from the importance-performance analysis (IPA), developed by Martilla and James, which identifies the product or service attributes an organization should focus on to enhance customer satisfaction [49].

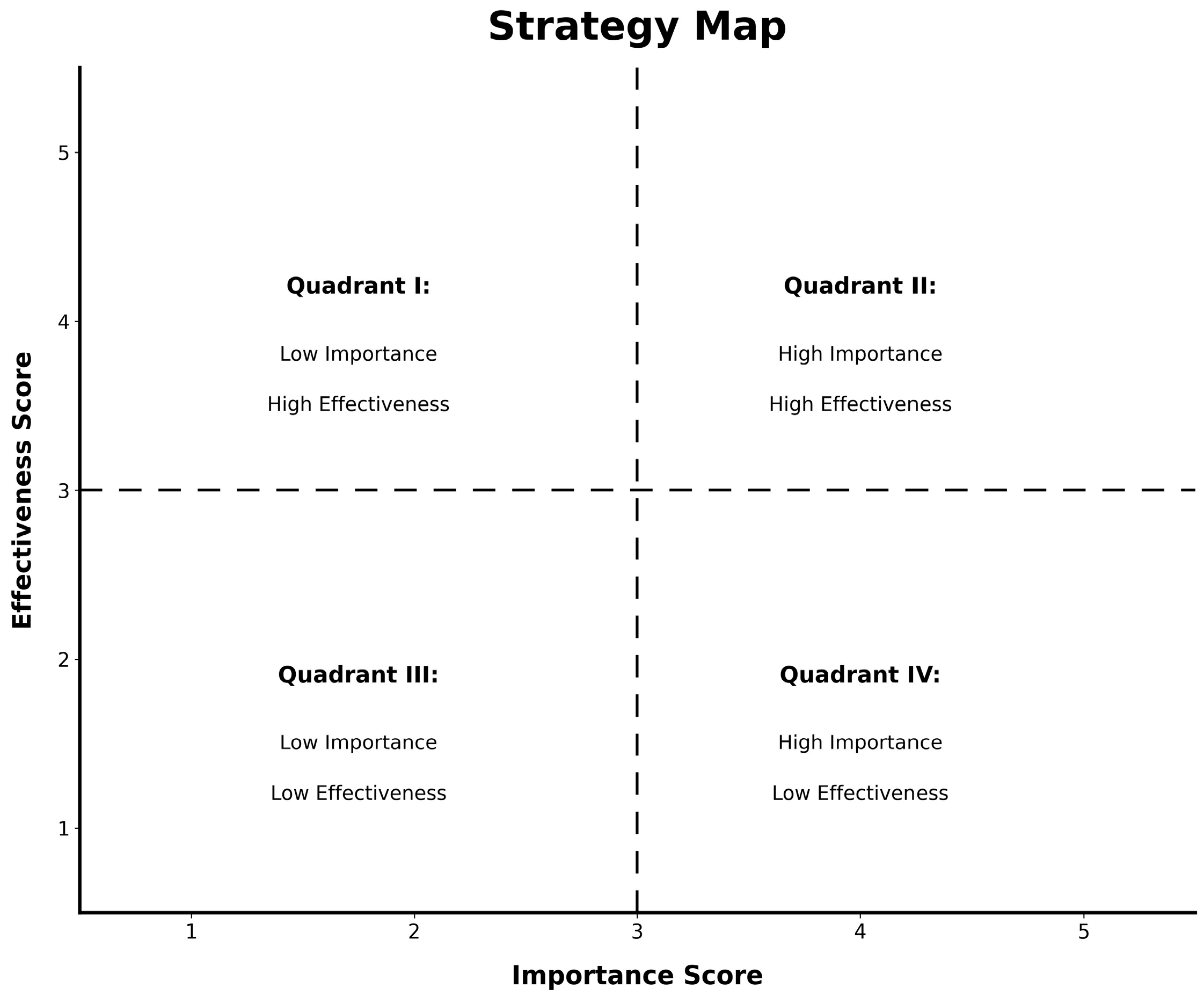

The model is divided into four quadrants based on their importance and effectiveness levels. The axis is determined by importance and effectiveness values, which divide the graph into four quadrants: high importance-high effectiveness, low importance-high effectiveness, high importance-low effectiveness, and low importance-low effectiveness. To determine the threshold values for all importance and effectiveness, this study uses the mean, the overall average score, as it better differentiates between high- and low-performing strategies in the collected data. Importance measures how necessary it is to have this strategy in place, and effectiveness assesses the extent to which it will solve the issue. Figure 2 shows how these strategies are sorted.

Figure 2.

IPA model.

4. Results

4.1. Literature Review Results

This research identified 10 barriers encountered in the green rating system through a literature review, which were subsequently incorporated into the questionnaire. The author also categorized these identified barriers into three different categories. To categorize these barriers, a thematic analysis was conducted. The process involved several steps before reaching the final categorization. The initial goal was to learn about the list of barriers. The process then advanced to the second cycle, which systematically analyzed and identified the common pattern of the barriers. These identified barriers were organized under specified patterns, as shown in Table 2. In addition, potential strategies to overcome barriers to implementing the green rating system are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Barriers and Their Categorization.

Table 3.

Potential solutions to overcome barriers to implementing the green rating system.

4.2. Questionnaire Results

4.2.1. Data and Demographic Information of Respondents

The survey questionnaire was distributed to different segments of the target audience via an online, custom-developed questionnaire. Participants came from various professions; 42% managed their organizations, 28% were consultants, 13% were contractors, and the remaining 17% belonged to multiple categories. It was observed that 47% of participants are involved in government sectors through different construction-related activities. Eighteen percent of respondents were from semi-government organizations engaged in construction services, while 31% came from the private sector.

Regarding their prior knowledge, 11% of participants have advanced knowledge of the green building rating system, 41% have intermediate knowledge, 32% are beginners, and 15% indicated they are unaware of such systems. Regarding prior experience with green building projects, only 26% have worked on green building initiatives or projects that consider green building aspects. Meanwhile, 74% have no prior experience with green building projects, highlighting a lack of practical experience among most construction practitioners.

4.2.2. Evaluation of the Implementation Barriers

To assess the identified barriers, participants were asked to rate their level of agreement on a scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The lack of awareness of building rating systems, the absence of technical capacity, and the reluctance of building owners to embrace green buildings emerged as the most widely acknowledged barriers, with over 85% of respondents endorsing them. Interestingly, no disagreements were observed for these top-rated barriers, with only about 15% of respondents expressing neutral opinions.

4.2.3. Barriers Related to Organization and Policy

In the survey, participants noted a lack of national efforts by both the government and private groups to utilize green construction technologies. This is largely because non-governmental and private groups depend on government assistance, particularly for large-scale projects. Participants also highlighted that green-building projects take longer than regular ones, due to poor planning and the slow adoption of green building principles. Finally, most participants felt that green building initiatives lacked sufficient financial assistance. This implies that the issue is serious and is impacting the sector’s progress. Table 4 summarizes the institutional and policy-related barriers, along with their relative importance, as reported by the survey participants.

Table 4.

The rank and score (mean) of barriers related to institutional and policy.

4.2.4. Barriers Related to Financial and Market

Regarding the higher costs of green building materials compared to conventional materials, the majority of participants agreed that green building materials are expensive and not readily available, posing an infrastructure-level challenge. The majority of respondents in the survey agreed that government subsidies for electricity and water prices may reduce the importance of green buildings. Many subsidies lead people to believe that customers do not fully grasp the importance of green buildings, which is why the government should reassess its plans in line with the 2030 vision. 53% of respondents expressed concern that project owners might withhold information, such as project costs, from officials of green building grading systems. The lack of transparency between owners and officials limits the sharing of important technological knowledge, mainly due to owners’ privacy concerns. Survey results indicate that 85% of respondents believe building owners have little incentive to adopt green technology, highlighting low motivation among stakeholders. The lack of a local rating system that meets local needs and conditions was also seen as a major problem. Based on the survey responses, Table 5 presents the rankings and scores for financial and market-related restrictions.

Table 5.

The rank and score (mean) of financial and market-related barriers.

4.2.5. Barriers Related to the Knowledge Gap

The study revealed a lack of awareness among the public and private sectors regarding green building rating systems, indicating that while stakeholders are familiar with sustainability concepts, they are often unaware of established international rating systems. Another reason found in this study was the overall lack of awareness about sustainable building principles, as evidenced by the absence of a sustainability focus in public projects and policy until recently. Regarding technical barriers, such as the lack of professional personnel, information, and reliable sources on green building rating systems, participants reached consensus, indicating a deficiency in specialized resources to provide expert advice to potential customers interested in green buildings. These knowledge-related barriers are quantified and ranked based on the survey results, as shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

The rank, score (mean)of knowledge-related barriers.

The survey results indicate that knowledge-related barriers need to be addressed as a priority, as they are major obstacles. A significant majority of participants identified numerous barriers as the main reason for these challenges, which collectively hinder the achievement of green building sustainability targets. Participants are well aware of their problems and can effectively highlight them when given the opportunity.

4.2.6. Evaluation of Proposed Solutions

This section focuses on the solution component of the research, in which various solutions were presented through a survey, and participants were invited to evaluate them and provide feedback. The majority of respondents concurred with the proposed solution and regarded it as the most significant for the Kingdom. The survey results provide valuable insights into the proposed solution, particularly regarding the available options. Participants agreed with the concept of implementing the proposed solutions to achieve the established objectives.

In this research, the majority of participants agreed with the proposed solution to allocate special funding to support emerging businesses and innovative technologies in the green building field. The government needs to allocate special funds for green building projects to encourage public participation. 83% of respondents of this study believe that this is an extremely important element of the solution for the adoption of the green building rating system.

To improve knowledge and implementation of green construction concepts, professional education is essential. Raising student awareness at the school, college, and university levels is essential. Even though it is late, it is still the right move to raise awareness of shifting patterns and how we can better prepare ourselves to meet obstacles head-on.

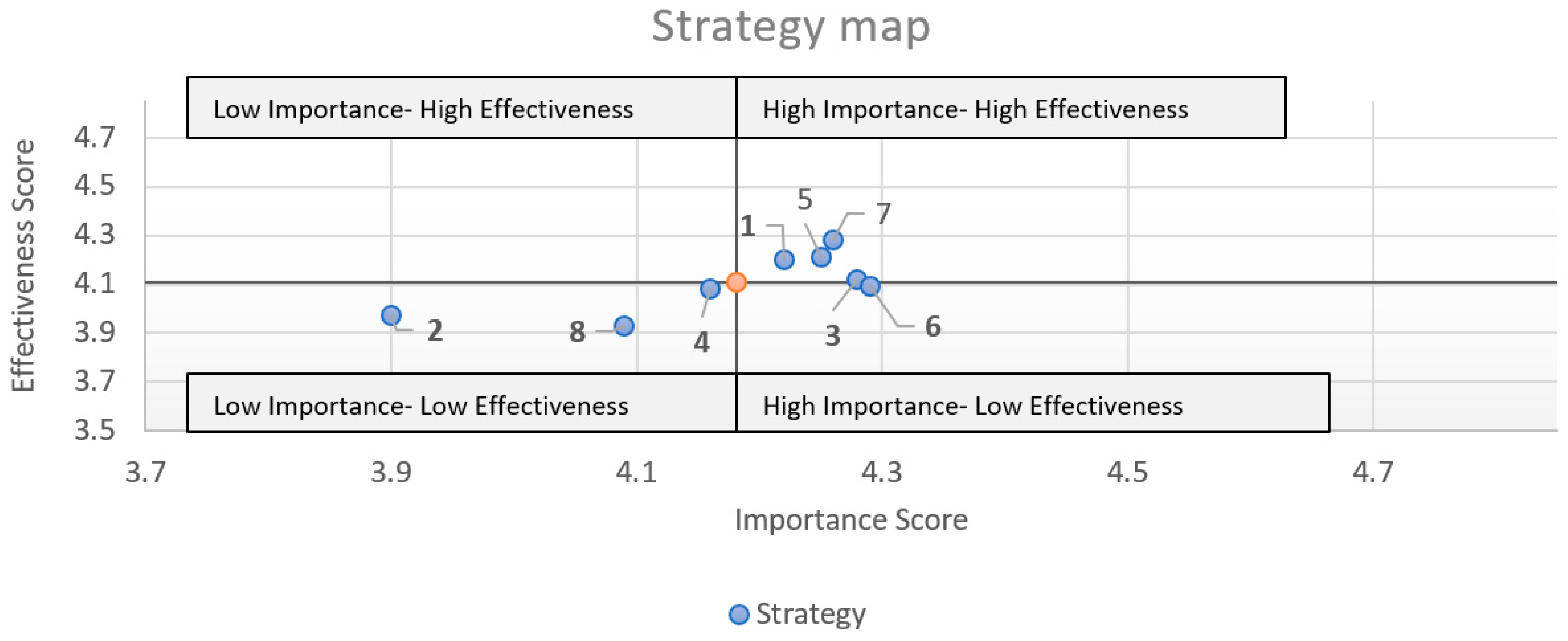

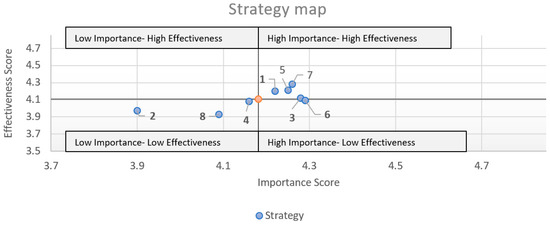

Table 7 presents the proposed strategies, each evaluated using importance and effectiveness scores, yielding averages for both. Figure 3, a “Strategy map for the strategies,” visually summarizes the key strategies identified by the respondent in this research via a survey on promoting green building practices. The strategy map was divided into four quadrants illustrating the relationships and priorities among different approaches.

Table 7.

The importance and effectiveness score of the proposed strategies.

Figure 3.

Strategy map for the strategies.

- First Quadrant: (High Importance, High Effectiveness)

According to survey responses, strategies S1, S3, S5, and S7 are performing well and are highly regarded by stakeholders. Respondents believe that both government funding and financial incentives are important and effective. Allocating special government funding to support emerging businesses and innovative technologies in the green building field; Prequalifying specialized consultants in the field of green buildings to achieve the rating systems classification; Introducing financial incentives (for example, tax exemption) to owners to adopt green building principles. The hierarchy of these four strategies can help decision-makers identify the most critical strategies for effective implementation, particularly when managing time and financial priorities.

- Second Quadrant: (High Importance, Low Effectiveness)

According to the survey results, the second quadrant represents high-performance, low-effectiveness solutions. The solution that falls in this quadrant is “S6,” which is establishing standards, processes, operations, and protocols for sustainable construction. [62] A similar result was found, while another study, conducted in the context of green building accreditation during operational phases, suggested a comparable solution [63]. The current approach is insufficiently stringent, underpublicized, and not widely adopted by stakeholders. Policy revisions, better communication, and clearer mandates improved their effectiveness.

- Third Quadrant: (Low Importance, Low Effectiveness)

Solutions in this quadrant are put into the “low importance and low effectiveness” category because these techniques are not highly appreciated or thought to be useful. Solutions that fall in this quadrant include “S4,” which is launching green building achievement awards and recognition programs. Ref. [64] in his research, also highlighted the need for certification programs, whereas another researcher [54] insisted on the need for building codes to promote green buildings. “S2” is another solution in this quadrant. It suggests that gaining knowledge about green building practice should be a priority to highlight the importance of green rating practice. “S8” is also one of the solutions that suggests that all new government building projects meet basic sustainability standards. Professional education is important, but its lower rankings may be due to market saturation, uncertainty about its direct effects, or the perception that current offerings are good enough. Unless strategies like S2, S4, and S8 are resourcefully redesigned, resources might be better directed to higher-impact strategies.

- Fourth Quadrant: (Low Importance, High Effectiveness)

Solutions of this quadrant are categorized with low importance and high effectiveness, as shown in Figure 3. These strategies might work well, but they are not really important. According to the respondent, none of the strategies in this study fall within this quadrant.

5. Discussion

This research aims to investigate the barriers to the adoption of green building rating systems and to propose strategic solutions to overcome them. This research has found that a lack of awareness across the public and private sectors is one of the most critical barriers. This finding is parallel to the study by [29], which was conducted in Ghana, where low public demand was identified as a primary obstacle. However, it contradicts studies conducted in developed countries such as the United States and the UK, where awareness levels are high. Technical implementation and regulatory complexity act as barriers to implementing GBRS in the studies by [19]. For the Saudi Context, A possible explanation for the lack of awareness barrier is that stakeholders are not fully aware of the long-term financial and environmental advantages, leading to low demand for implementing these systems in their projects. To address this issue, 45% of the respondents in this research emphasized the importance of launching public awareness campaigns on green building in collaboration with leading construction firms and the government. These programs would open new doors for economic expansion and foster beneficial cooperation between the public and private sectors. A clear distinction emerged regarding the nature of these barriers. The findings of this research highlight that economic barriers, specifically initial high costs, are a common challenge shared worldwide. Similarly, they have been identified by research consistent with findings in the US, the UK [19], and Ghana [29]. However, one finding specific to the Saudi context is the high ranking of ‘Government Funding’ as a critical solution (Quadrant I). In developed markets where private financing models often drive adoption, this study shows that the Saudi market differs because it relies on centralized government intervention, likely due to the top-down approach of the Vision 2030 program.

Technical barriers include a lack of professional personnel, information, and reliable sources related to green building rating systems, which is another major obstacle. It is crucial to start green building achievement awards and recognition initiatives. Establishing rewards and incentive programs that emphasize the creation of creative projects and the promotion of new entrants is crucial. Government-sponsored programs could help reduce the numerous obstacles new players face, enabling them to introduce their goods and services.

It is crucial to prequalify green building experts to receive the rating system classification. Remarkably, 46% of those surveyed think it is very important. By offering their professional insights to the public seeking assistance with green building solutions, consultants, advisors, and certifying organizations play a vital role. The government might start offering certification courses and training programs that would educate prospective applicants on cutting-edge concepts and emerging trends.

According to the participants’ responses, most are in favor of establishing standards, procedures, operations, and protocols for sustainable construction. Of those surveyed, 47% think it is very important, 37% think it is quite important, and 14% think it is somewhat important.

A lack of funding and financing solutions for green building projects is another challenge identified in this study. To counter this, 51% of respondents believe it is very important to introduce financial incentives, such as tax exemptions, to encourage owners to adopt green building principles. In comparison, 28% say it is quite important, and 17% feel it is somewhat important. Just 17% believe it to be somewhat important. In general, 79% of respondents support offering monetary rewards to encourage property owners to adopt green building practices.

Establishing minimal sustainable construction standards (calling for a minimum rating level) for all new government projects. It is noteworthy that 39% of those surveyed think it is very essential. Establishing fundamental standards for green buildings is essential because it empowers all parties involved to act at any scale.

Study Implications

The implications of this research are important for all construction industry stakeholders who prefer to adopt green building rating systems (GBRS) in their respective projects in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In terms of real-world effects, the research’s outcomes provide stakeholders with a roadmap for adopting the green rating system. The study highlights that while implementing the high-importance strategies of this research, stakeholders can put themselves in a position where they can obtain economic benefits established in the broader literature, such as saving operational expenses by 8–9%, increasing the overall value of the building by 7.5%, and improving return on investment by 6.6%. GBRS adoption benefits human capital in more ways than just financial ones. It also makes interior spaces healthier, increasing employee productivity by up to 8% [18]. These benefits make it a powerful strategy to improve business performance and support the national goals of Saudi Vision 2030, as it enhances the sustainability and productivity of the physical environment.

Theoretical implications: this study identifies several areas for researchers to address, thereby overcoming the topic’s research limitations in future studies. These areas include understanding the adaptation framework of GBRS in a rapidly developing economy, performing a thorough performance-based evaluation of the existing standard to analyze how it affects the real world, and performing an in-depth analysis to measure the number of job creations, as it is one of the growing concerns, and to understand how culture is affecting the adaptation of GBRS. Additionally, more strategies and different analysis methods could be used to compare and recommend the best result.

This study offers a definitive, actionable framework for decision-makers in government, business, and project ownership concerning managerial implications. The study’s findings suggest that the government and policymakers should make it easier for green projects to be funded, offer tax exemptions and other financial incentives to encourage the adoption of green buildings, and mandate that all new government projects meet minimum sustainable building standards. The top priority for industry leaders and professionals is to close the knowledge gap. The study suggests achieving this by launching public awareness campaigns to highlight the long-term benefits of green buildings, making prequalification programs mandatory for specialized consultants, and introducing green education subjects at universities to develop professional experts in this field. Another finding of this study suggests that project owners and stakeholders should shift their focus from initial costs to long-term value. They can achieve this by employing a lifecycle cost analysis, leveraging available financial incentives, and engaging a qualified green building consultant early in the design process to mitigate risks and optimize outcomes.

6. Conclusions

As significant energy users, buildings have contributed to the development of global sustainable building standards. Saudi Vision 2030 encompasses initiatives to improve sustainability in energy, housing, and water sectors, with green building standards promoting more environmentally friendly practices. This study used the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) model to evaluate the identified barriers to the adoption of Green Building Rating Systems (GBRS) in Saudi Arabia and to prioritize eight strategic solutions. These strategies offered a targeted roadmap for policymakers aligned with Vision 2030. A survey of stakeholders revealed key barriers, including a lack of awareness and experience with green buildings, which highlights the need for awareness campaigns and training. Infrastructure challenges are critical, suggesting the creation of a government or private sector committee to investigate root causes and develop solutions. Collaboration across sectors is vital to the successful adoption of green building systems.

The survey results in this research show a significant increase in the use of green building ratings in Saudi Arabia compared to 2014. Despite this positive trend, many areas require improvement and have untapped potential for future growth. It is worth noting that the survey participants had varying levels of familiarity with green building rating systems, with the majority expressing a lack of awareness. In addition, it was surprising to discover that the majority of construction practitioners had not been involved in any prior green building projects, highlighting a significant lack of practical experience in the sector. These findings offer opportunities for targeted initiatives that aim to increase awareness and develop practical expertise, further advancing sustainable construction in the region.

To more effectively advance green building initiatives in Saudi Arabia and overcome current study limitations, future research should take a wider perspective. This includes evaluating current green building standards to understand their impact on design and construction, engaging a broad range of stakeholders to identify problems and solutions, and examining economic effects such as job creation, financial benefits, and cost savings from green practices. Moreover, addressing overlooked cultural and regulatory barriers with targeted strategies is crucial, supported by high-level government and private-sector commissions that research and consult on these obstacles. Given the rapid evolution of the Saudi construction sector, it is recommended that this IPA evaluation be conducted annually to establish updated standards and track the shifting priorities of industry stakeholders. This collaborative, research-based strategy will help inform decisions, develop policies, and promote sustainable practices nationwide and globally.

Every study has limitations; this study has some as well. Firstly, the data relies solely on stakeholders’ perceptions, whereas market sentiment may differ from objective performance data. Secondly, while the sample size of 96 in this study is statistically sufficient, as calculated using Cochran’s formula, a larger sample in future studies would allow for a more granular segmentation analysis, such as comparing government vs. private-sector views. Due to the sampling limitation, the study did not study the relation between occupational background and scoring outcome, which can be addressed in future work. Lastly, the study is context-specific to Saudi Arabia, so its results should be cautiously generalized to other GCC nations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.M. and S.A. (Saad Aljadhai); Methodology, A.B.M. and S.A. (Saad Aljadhai); Validation, S.A. (Salman Akhtar); Formal analysis, T.A. and Salman Akhtar; Investigation, S.A. (Salman Akhtar) and S.A. (Saad Aljadhai); Data curation, T.A.; Writing—original draft, A.B.M., T.A. and S.A. (Salman Akhtar); Writing—review & editing, S.A. (Saad Aljadhai); Visualization, T.A.; Supervision, A.B.M. and S.A. (Saad Aljadhai); Project administration, A.B.M.; Funding acquisition, A.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Nesma and Partners’ Chair for Construction Research and Building Technologies for funding this research work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approval obtained (approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of King Saud University (KSU-HE-25-1285) on 11 November 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gupta, J.; Bai, X.; Liverman, D.M.; Rockström, J.; Qin, D.; Stewart-Koster, B.; Rocha, J.C.; Jacobson, L.; Abrams, J.F.; Andersen, L.S.; et al. A just world on a safe planet: A Lancet Planetary Health–Earth Commission report on Earth-system boundaries, translations, and transformations. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e813–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flachenecker, F.; Rentschler, J. From barriers to opportunities: Enabling investments in resource efficiency for sustainable development. Public Sect. Econ. 2019, 43, 346–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.A.; Ahmad, M.I.; Yusup, Y. Issues, impacts, and mitigation strategies for carbon dioxide emissions in the building sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klufallah, M.M.A.; Nuruddin, M.F.; Khamidi, M.F.; Jamaludin, N. Assessment of carbon emission reduction for buildings projects in Malaysia-A Comparative Analysis. E3S Web Conf. 2014, 3, 01016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelisti, L.; De Cristo, E.; Guattari, C.; Gori, P.; De Rubeis, T.; Monteleone, S. Preliminary development of a non-contact method for thermal characterization of building walls: Laboratory evaluation. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 69, 106012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGI (Saudi Green Initiative). SGI Target: Reduce Carbon Emissions by 278 Mtpa by 2030. 2021. Available online: https://www.sgi.gov.sa/about-sgi/sgi-targets/reduce-carbon-emissions// (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Hailemariam, A.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O. Towards a circular economy: Implications for emission reduction and environmental sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 1951–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh US Green Building Council, “Directory: Projects,”. 2014. Available online: http://www.usgbc.org/projects (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L. Research on sustainable green building space design model integrating IoT technology. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A.; Wargocki, P.; Rismanchi, B. Ten questions concerning green buildings and indoor air quality. Build. Environ. 2016, 112, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikar, A.A.; Joshi, D.A.; Menon, R. International Scenario of Certifications and Rating Systems for Green Buildings. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2020, 9, 1678–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaudin, A.; Elias, E.; Saifudin, A. A comparison of the green building’s criteria. E3S Web Conf. 2014, 3, 01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanoff, D. Color, light, and birth space design: An integrative review. Color Res. Appl. 2023, 48, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Building Council of Australia. Home—Green Building Council of Australia. Available online: https://www.gbca.au/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Heerwagen, J. Investing in People: The Social Benefits of Sustainable Design. Washington. 2006. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/68454440/Investing_In_People_The_Social_Benefits_of_Sustainable_Design?uc-g-sw=90647814 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Paevere, P.J. Impact of Indoor Environment Quality on Occupant Productivity and Well-Being in Office Buildings. Environment Design Guide, 2008, 1–9. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26151865 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Reddy, V.S. Sustainable Construction: Analysis of its costs and financial benefits. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Manag. 2016, 3, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klufallah, M.M.A.; Ibrahim, I.S.; Moayedi, F. Sustainable practices barriers towards green projects in Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 220, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosly, I. Barriers to the diffusion and adoption of green buildings in Saudi Arabia. J. Manag. Sustain. 2015, 5, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, S.; Lange, M.A.; Artopoulos, G.; Albuflasa, H.M.; Assimakopoulos, M.; Attia, S.; Azar, E.; Cuce, E.; Hajiah, A.; Meir, I.A.; et al. Characteristics of the built environment in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East and related energy and climate policies. Energy Effic. 2024, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, N.; Abbar, S.D.A. Sustainability in the Middle East: Achievements and challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2015, 6, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubba, S. LEEDTM Professional Accreditation, Standards, and Codes. In LEED v4 Practices, Certification, and Accreditation Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 113–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Osman, A.I.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L.; Ihara, I.; Yap, P.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies to save energy in the context of the energy crisis: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2003–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, F.R.; Csala, D. GCC countries’ renewable energy penetration and the progress of their energy sector projects. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 211986–212002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Top 10 Countries for LEED in 2023 Demonstrate That the Green Building Movement Is Truly Global|U.S. Green Building Council. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/articles/top-10-countries-leed-2023-demonstrate-green-building-movement-truly-global (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency). Power Reactor Information System (PRIS) (Database). 2020. Available online: https://pris.iaea.org/PRIS/home.aspx (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Ribeiro, L.M.L.; Scolaro, T.P.; Ghisi, E. LEED Certification in building Energy Efficiency: A review of its performance efficacy and global applicability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Darko, A.; Olanipekun, A.O.; Ameyaw, E.E. Critical barriers to green building technologies adoption in developing countries: The case of Ghana. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 172, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwaikat, L.N.; Ali, K.N. Green buildings cost premium: A review of empirical evidence. Energy Build. 2015, 110, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, T.; Mollaoğlu-Korkmaz, S.; Cotner, R.; Goldsberry, A.D. Public Policy and Impacts on Adoption of Sustainable Built Environments: Learning from the Constuction Industry Playmakers. J. Green Build. 2014, 9, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of barriers to green building adoption. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 25, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikyema, G.A.; Blouin, V.Y. Barriers to the adoption of green building materials and technologies in developing countries: The case of Burkina Faso. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 410, 012079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Zhu, L.; Tan, J.S.H. Green business park project management: Barriers and solutions for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Wang, L.M.; Waters, C.E.; Bovaird, J.A. A need for evidence-based and multidisciplinary research to study the effects of the interaction of school environmental conditions on student achievement. Indoor Built Environ. 2016, 25, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence Provides Market Research—Consulting, Reports, Advisory, Sizing; Consulting—Client Research, Market Analysis, Competitive Landscape Analysis, Global Strategic Business Reports and Custom Market Research. Contact Us Now for Any Kind of Report! Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/market-analysis (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Mordor Intelligence Research & Advisory. Market Size & Share Analysis—Growth Trends & Forecasts (2024–2029). November 2023. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/construction-sector-in-the-kingdom-of-saudi-arabia-industry (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A. Role of Urban Greening Strategies for Environmental Sustainability—A Review and Assessment in the context of Saudi Arabian Megacities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Riediger, N. BIM as a tool for Green Building Certifications: An evaluation of the energy category of LEED, BREEAM and DGNB. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1425, 012162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Pourhashemi, S.O.; Nilashi, M.; Abdullah, R.; Samad, S.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Aljojo, N.; Razali, N.S. Investigating influence of green innovation on sustainability performance: A case on Malaysian hotel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, E.; Adamu, Z.; Al-Otaibi, A. Exploring the nature and impact of Client-Related delays on contemporary Saudi construction projects. Buildings 2022, 12, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, A.; De Soto, B.G. Estidama and the Pearl Rating System: A Comprehensive Review and Alignment with LCA. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabel, A.; Alwetaishi, M. Towards sustainable residential buildings in Saudi Arabia according to the conceptual framework of “MostAdam” Rating System and Vision 2030. Sustainability 2021, 13, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirror, H.; Dwidar, S.; Derbali, A.; Abdelsattar, A.; Abdel-Gawad, D. Market transformation towards sustainability in Saudi Arabia: A comparison between Mostadam and LEED rating systems. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1026, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Surf, M.; Balabel, A.; Alwetaishi, M.; Abdelhafiz, A.; Issa, U.; Sharaky, I.; Shamseldin, A.; Al-Harthi, M. Stakeholder’s perspective on green building rating systems in Saudi Arabia: The case of LEED, Mostadam, and the SDGs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, H.Z.H.; Tong, S. Green Product Innovation Strategies for Environmental Sustainability in the Construction Sector. J. Contemp. Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 1, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjundeswaraswamy, T.S.; Divakar, S. Determination of Sample Size and Sampling Methods in Applied Research. Proc. Eng. Sci. 2021, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H. Revisiting importance–performance analysis. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Chen, L. The incentive effects of different government subsidy policies on green buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 135, 110123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Kukah, A.S.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Pariafsai, F. Green finance for green buildings: A systematic review and conceptual foundation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalirazar, S.; Sabzi, Z. Barriers to sustainable development: Critical social factors influencing the sustainable building development based on Swedish experts’ perspectives. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1963–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.; Shamayleh, A.; El-Sayegh, S.; Formaneck, S. Prioritizing risks in sustainable construction projects using a risk matrix-based Monte Carlo Simulation approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 65, 102576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Sandanayake, M.; Miao, P.; Shi, Y.; Yap, P. Sustainability Considerations of Green Buildings: A detailed overview on current advancements and future considerations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, B.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. A financing model to solve financial barriers for implementing green building projects. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 240394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Payne, S. Green housing transition in the Chinese housing market: A behavioural analysis of real estate enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, N.; Olanipekun, A.O.; Omotayo, T. Reward and compensation incentives for enhancing green building construction. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 11, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgun, A.P.; Koc, K. Contractor prequalification for green buildings—Evidence from Turkey. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 1377–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino-Sádaba, S.; González-Jaen, L.F.; Pérez-Ezcurdia, A. Using project management as a way to sustainability. From a comprehensive review to a framework definition. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Kassem, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Ali, K.N. Study on Green Building Promotion Incentive Strategy Based on Evolutionary Game between Government and Construction Unit. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcoe, T.; Toffel, M.W. Government green procurement spillovers: Evidence from municipal building policies in California. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 68, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Hua, J.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; et al. Green building practices to integrate renewable energy in the construction sector: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 22, 751–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamoozian, M.; Zhang, H. Obstacles to green building accreditation during operating phases: Identifying Challenges and solutions for sustainable development. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 24, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isimbi, D.; Park, J. The analysis of the EDGE Certification System on Residential Complexes to improve Sustainability and Affordability. Buildings 2022, 12, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).