Do Carbon Emissions Hurt? Novel Insights of Financial Development and Economic Growth Nexus in China

Abstract

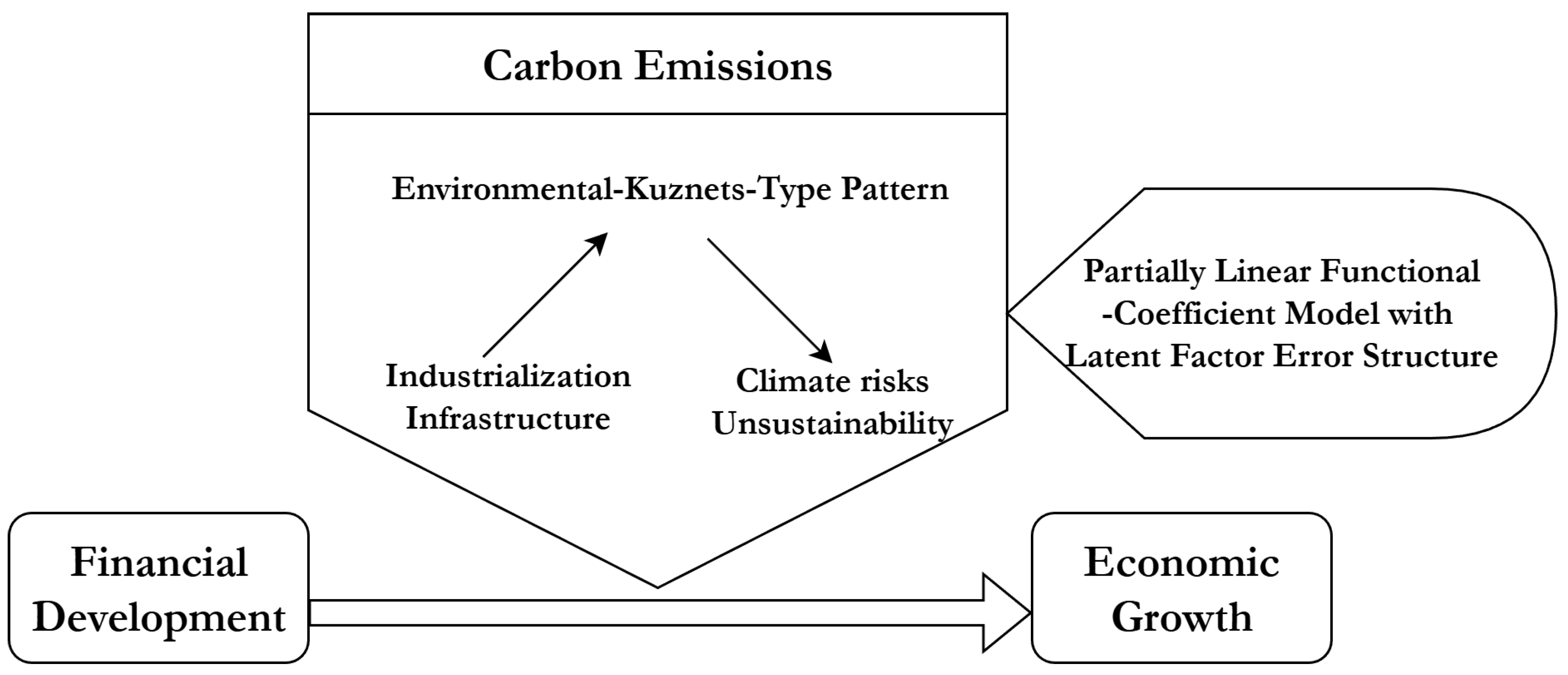

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

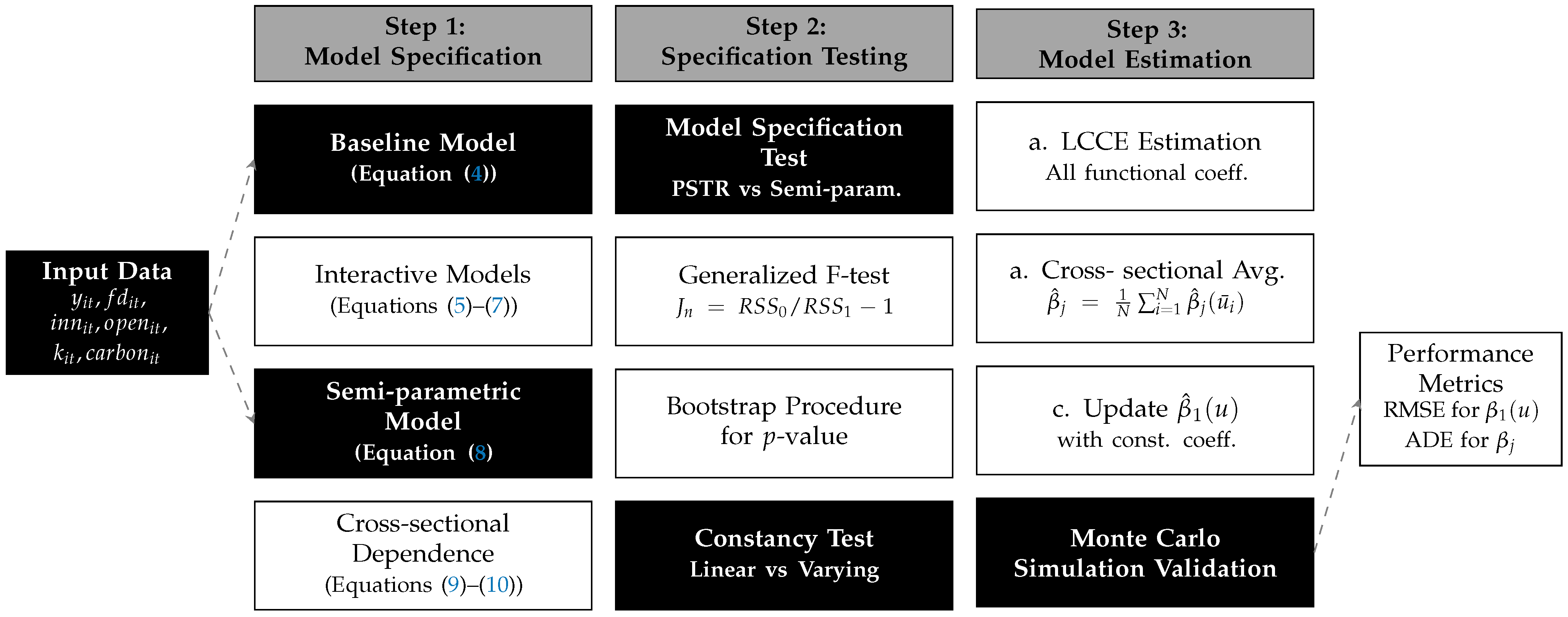

3. Methodology

3.1. The Baseline Model

3.2. The Semi-Parametric Model with Cross-Sectional Dependence

3.3. Model Specification Test

- Let , , , , and denote the estimators of the corresponding parameters under the null hypothesis. Calculate the residuals for observed data by .

- Resample from the empirical distribution of the centered residuals to obtain bootstrap residuals , where denotes the sample mean of .

- Generate bootstrap sample by .

- Based on the sample , calculate the test statistic .

- Compute the bootstrap p-value of by the frequency of the event among the bootstrap sampling.

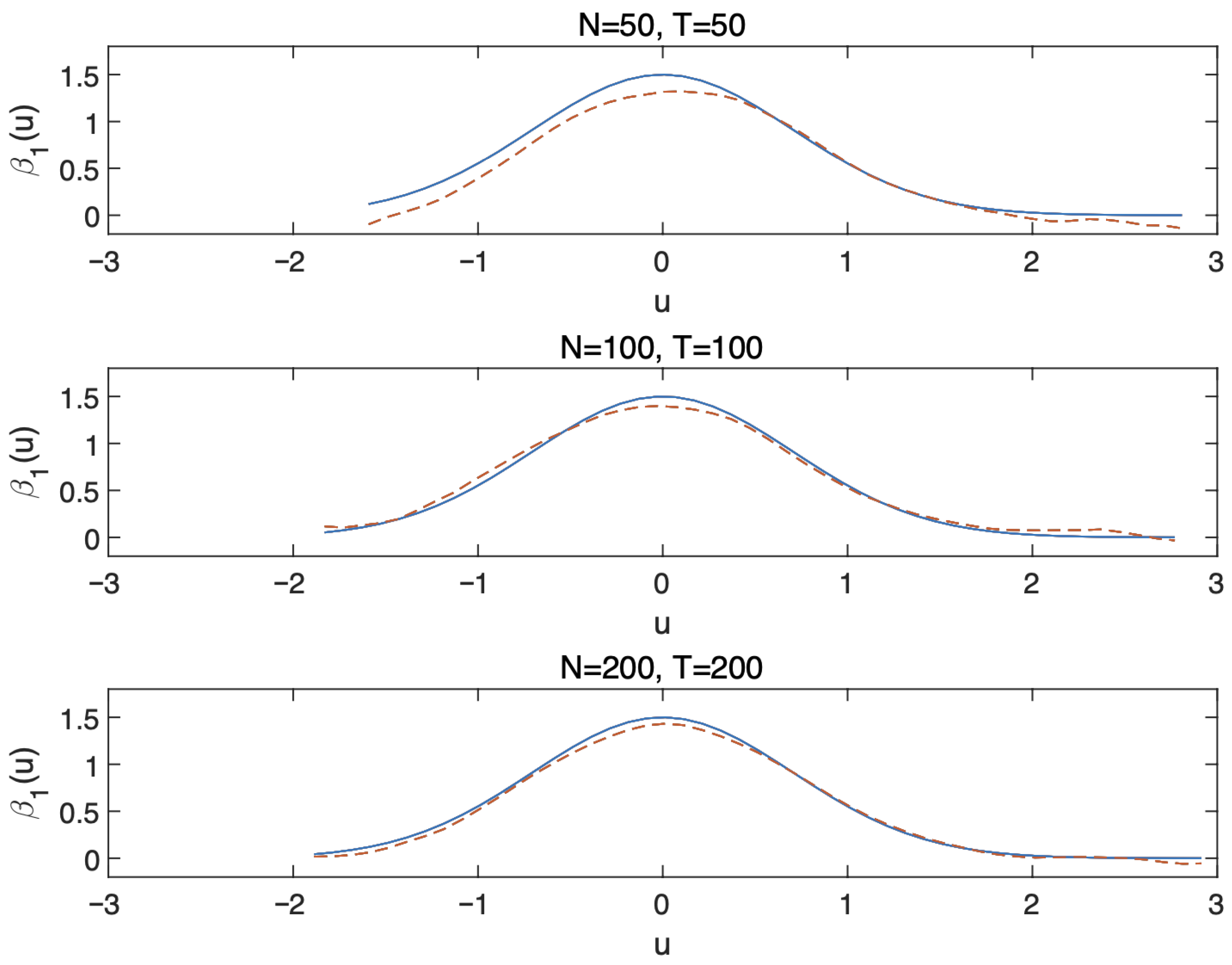

3.4. Estimation Procedure

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

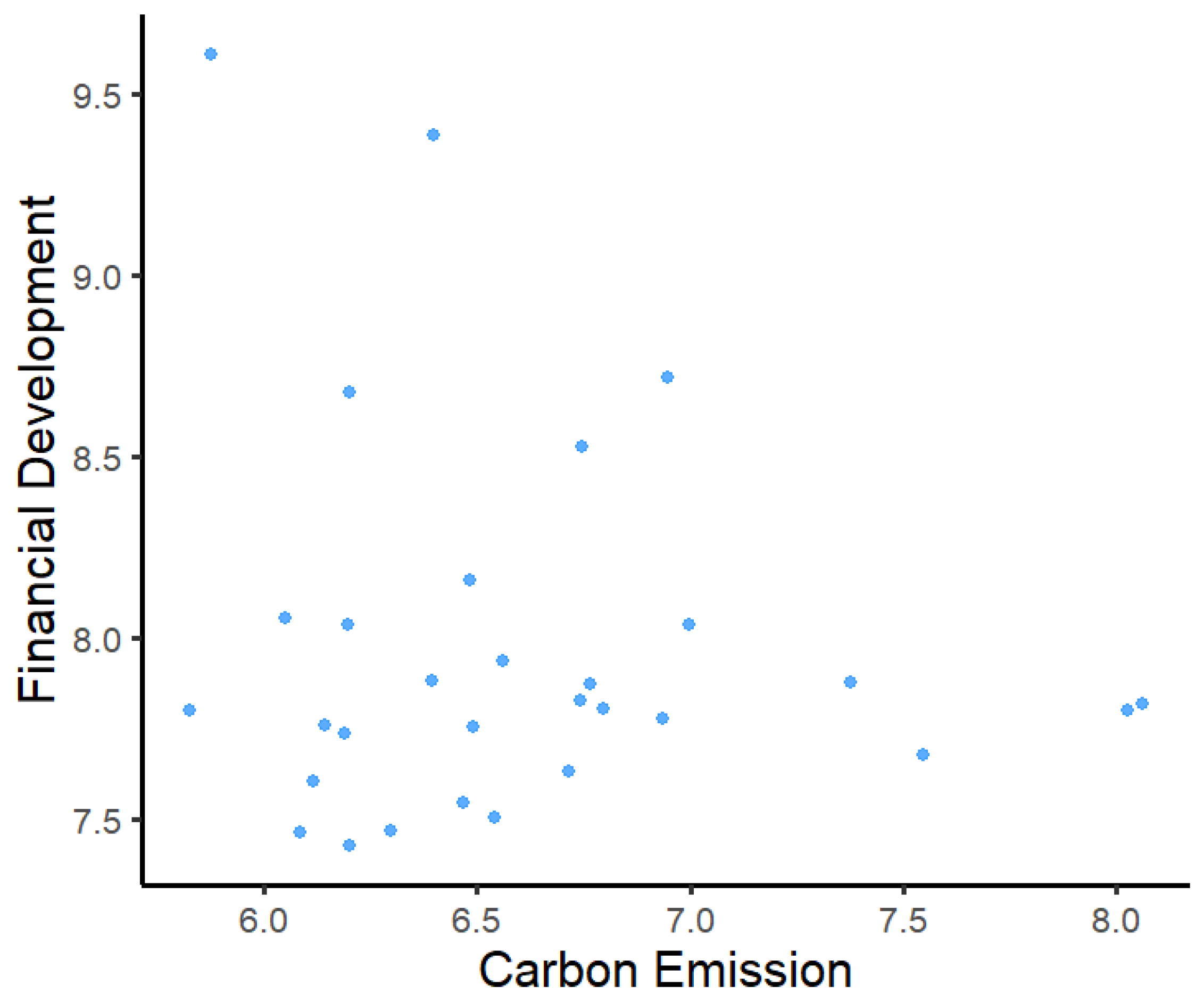

4.1. Data and Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Results of Baseline Models

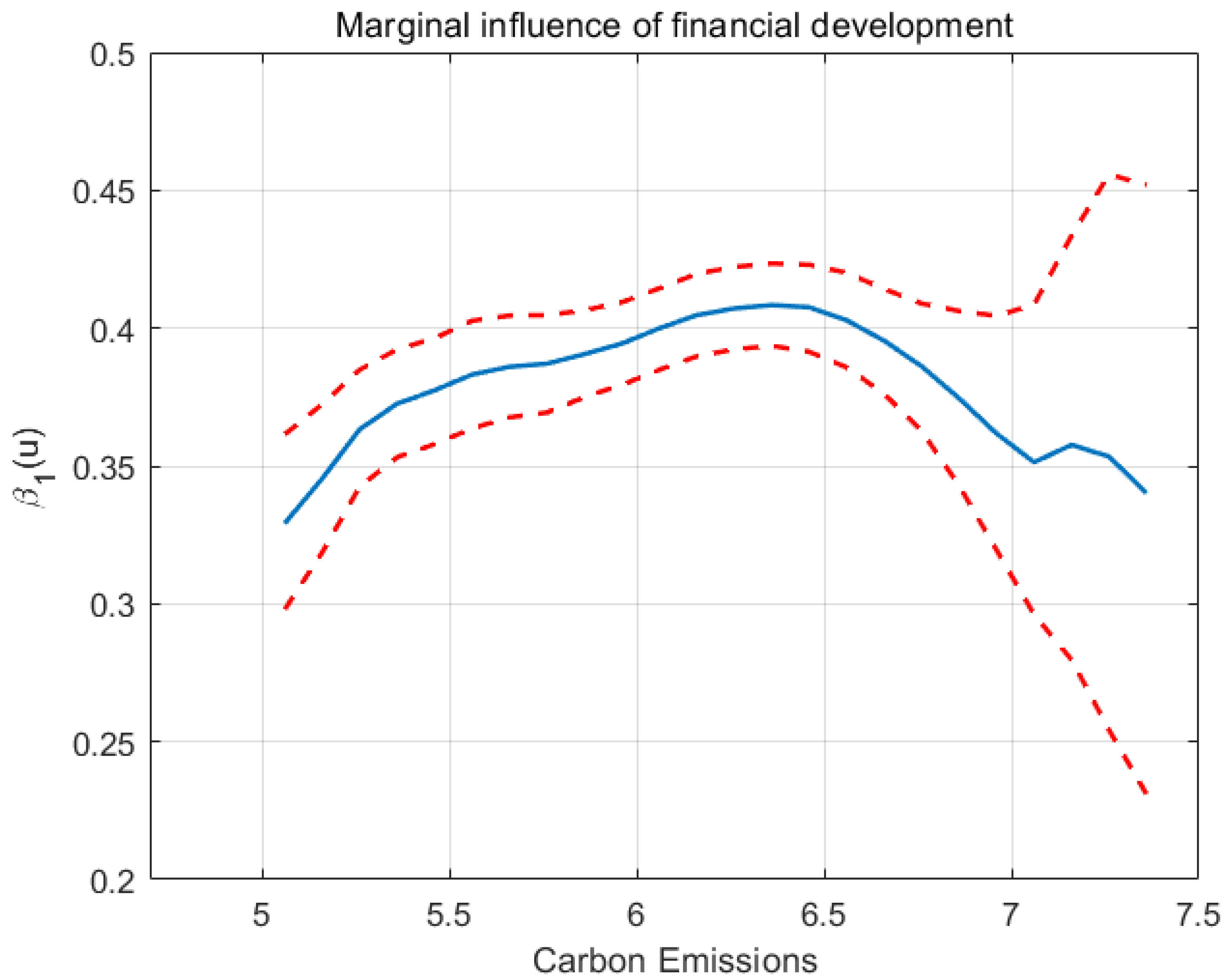

4.3. Results of Semi-Parametric Model

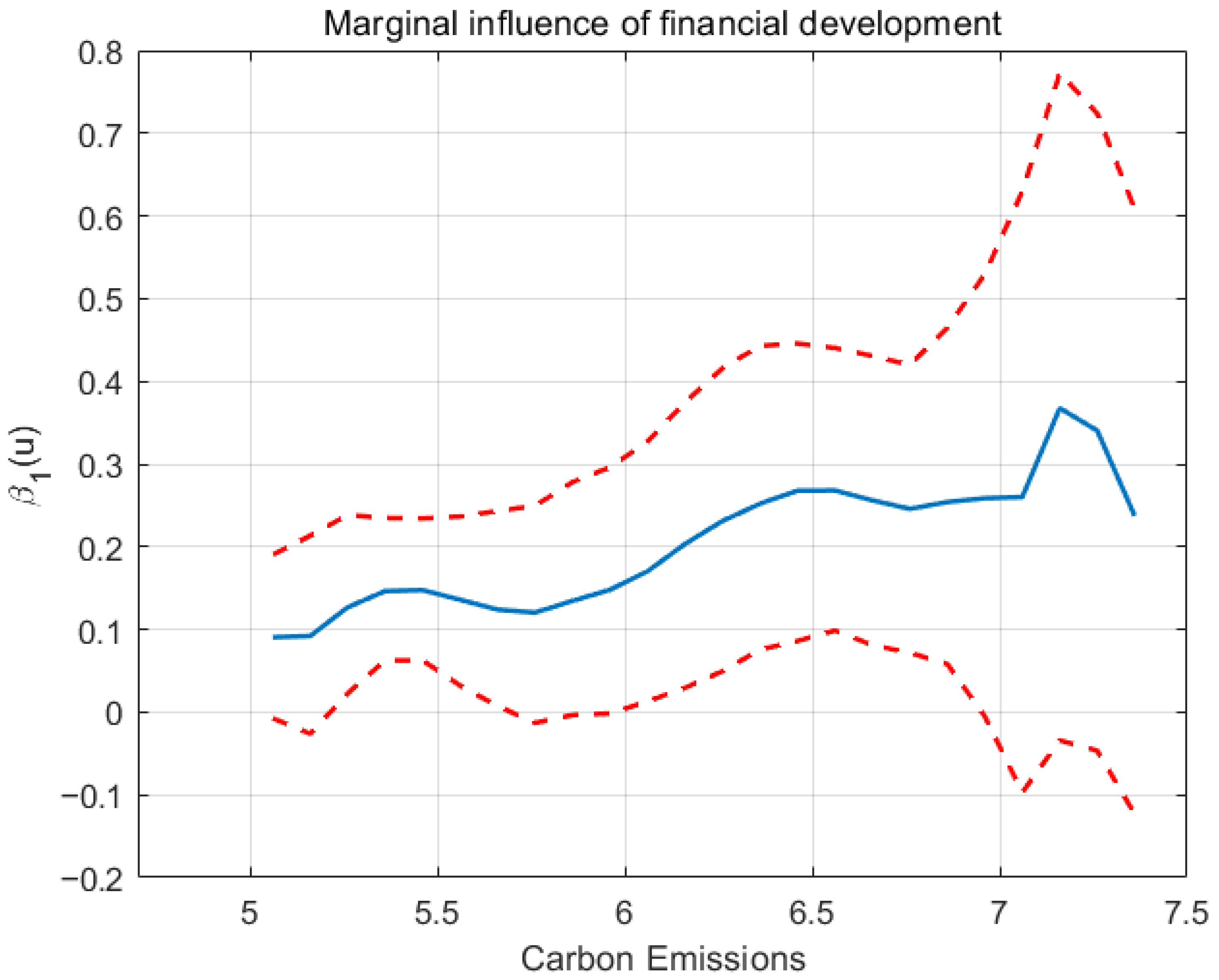

4.4. Robust Test

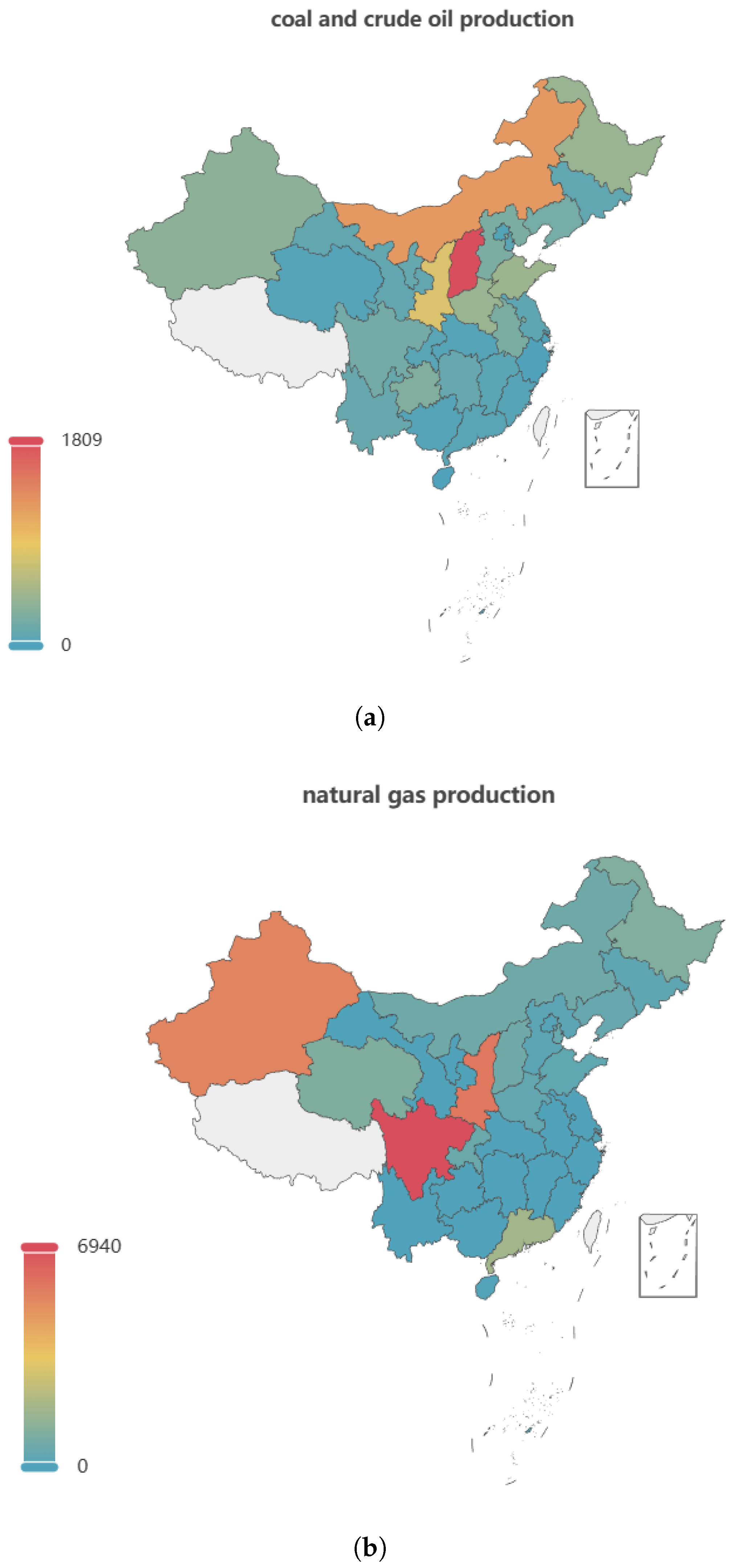

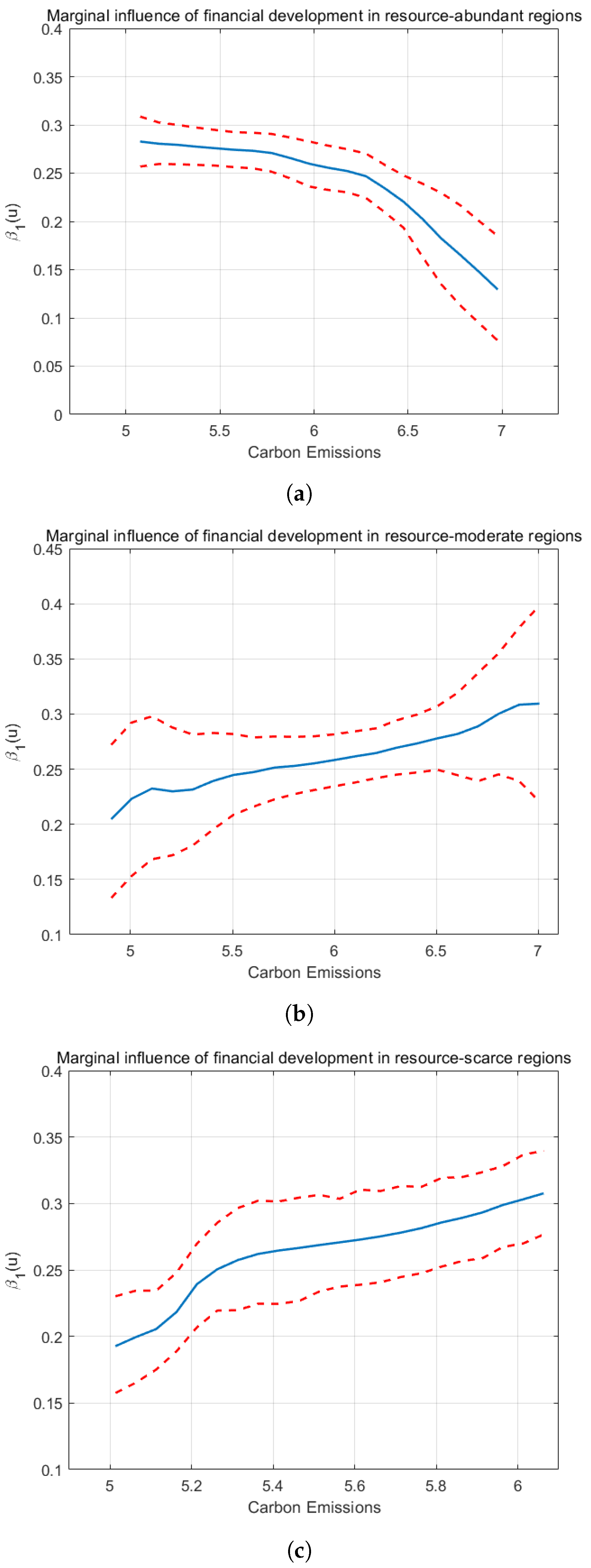

4.5. Further Discussion

4.5.1. Cross-Country Comparison

4.5.2. Other Econometrics Methodology

4.5.3. Connections to Frontier Environmental Studies

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- King, R.G.; Levine, R. Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Q. J. Econ. 1993, 108, 717–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhabib, J.; Spiegel, M.M. The role of financial development in growth and investment. J. Econ. Growth 2000, 5, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R. Finance and growth: Theory and evidence. Handb. Econ. Growth 2005, 1, 865–934. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, A.; Schiantarelli, F.; Weiss, A. Does financial liberalization improve the allocation of investment?: Micro-evidence from developing countries. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 83, 562–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhaus, W.D. A review of the Stern review on the economics of climate change. J. Econ. Lit. 2007, 45, 686–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Van Hoang, T.H.; Mahalik, M.K.; Roubaud, D. Energy consumption, financial development and economic growth in India: New evidence from a nonlinear and asymmetric analysis. Energy Econ. 2017, 63, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botev, J.; Égert, B.; Jawadi, F. The nonlinear relationship between economic growth and financial development: Evidence from developing, emerging and advanced economies. Int. Econ. 2019, 160, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wei, W. Financial development, openness, innovation, carbon emissions, and economic growth in China. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Bai, D.; Cong, X. Modeling the dynamic influences of economic growth and financial development on energy consumption in emerging economies: Insights from dynamic nonlinear approaches. Energy Econ. 2022, 116, 106404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Jahanger, A.; Makhdum, M.S.A.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Bashir, A. How do financial development, energy consumption, natural resources, and globalization affect Arctic countries’ economic growth and environmental quality? An advanced panel data simulation. Energy 2022, 241, 122515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeigbe, K.B.; Ganda, F. The impact of pollution and carbon emission control on financial development, environmental quality, and economic growth: A global analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashof, D.A.; Ahuja, D.R. Relative contributions of greenhouse gas emissions to global warming. Nature 1990, 344, 529–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.D.; Gillett, N.P.; Stott, P.A.; Zickfeld, K. The proportionality of global warming to cumulative carbon emissions. Nature 2009, 459, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, R.; Tiwari, A.K.; Khalid, U.; Shahbaz, M. Nexus between carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth in G7 countries: Fresh insights via wavelet coherence analysis. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66, 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, T.; Kayani, U.N.; Gul, A.; Haider, S.A.; Ahmad, S. Carbon emissions, environmental distortions, and impact on growth. Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 107040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-González, J.; Vivanco, D.F.; Jin, Y. World economies’ progress in decoupling from CO2 emissions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 71101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigas, A. The impact of CO2 emissions and climate on economic growth and productivity: International evidence. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2024, 28, e13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yi, X. China’s Economic Growth under the “Dual Carbon” Target: Influencing Mechanisms, Trend Characteristics and Countermeasures Suggestions. Economist 2022, 7, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A. Trade, the pollution haven hypothesis and the environmental Kuznets curve: Examining the linkages. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, S.; Mandel, A.; Monasterolo, I.; Schütze, F.; Visentin, G. A climate stress-test of the financial system. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Understanding openness and productivity growth in China: An empirical study of the Chinese provinces. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Fang, Y.; Xu, Q. Testing capital asset pricing models using functional-coefficient panel data models with cross-sectional dependence. J. Econom. 2022, 227, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. Panel data models with interactive fixed effects. Econometrica 2009, 77, 1229–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.S. Financial Deepening in Economic Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, M.J. Money and Capital or Financial Deepening in Economic Development? J. Money Credit. Bank. 1978, 10, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.S. Financial development and economic growth: International evidence. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 1986, 34, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R. Financial development and economic growth: Views and agenda. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 688–726. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, P.L.; Wachtel, P. What is happening to the impact of financial deepening on economic growth? Econ. Inq. 2011, 49, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.; Georgiadis, G.; Straub, R. The finance and growth nexus revisited. Econ. Lett. 2014, 124, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.H.; Singh, N. Does too much finance harm economic growth? J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Alagidede, P. Nonlinearities in financial development–economic growth nexus: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2018, 46, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous technological change. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.; Kortum, S. Trade in ideas Patenting and productivity in the OECD. J. Int. Econ. 1996, 40, 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, P. The role of creative innovation in economic growth: Some international comparisons. J. Asian Econ. 2008, 19, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. Do technological innovations promote urban green development?–A spatial econometric analysis of 105 cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, W. How do economic openness and R&D investment affect green economic growth?–Evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Yanikkaya, H. Trade openness and economic growth: A cross-country empirical investigation. J. Dev. Econ. 2003, 72, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, C. Trade as a threshold variable for multiple regimes. Econ. Lett. 2002, 77, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menyah, K.; Nazlioglu, S.; Wolde-Rufael, Y. Financial development, trade openness and economic growth in African countries: New insights from a panel causality approach. Econ. Model. 2014, 37, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M. Does environmental degradation shackle economic growth? A panel data investigation on 11 Asian countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Examining carbon emissions economic growth nexus for India: A multivariate cointegration approach. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3008–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Song, G. Exploring carbon emissions, economic growth, energy and R&D investment in China by ARDL approach. In Proceedings of the 2013 21st International Conference on Geoinformatics, Kaifeng, China, 20–22 June 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Pinar, M.; Stengos, T. Renewable energy consumption and economic growth nexus: Evidence from a threshold model. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM); COM (2021) 564 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M. Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon—Climate Change and Financial Stability; Speech at Lloyd’s of London; Bank of England: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Campiglio, E.; Dafermos, Y.; Monnin, P.; Ryan-Collins, J.; Schotten, G.; Tanaka, M. Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition. Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing and Competitiveness. World Bank, 2019. License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/32419 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Lu, W.; Huang, J.; Musshoff, O. Climate threshold, financial hoarding and economic growth. Appl. Econ. 2015, 47, 4535–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zou, B.; Du, K.; Li, K. Do renewable energy technology innovations promote China’s green productivity growth? Fresh evidence from partially linear functional-coefficient models. Energy Econ. 2020, 90, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, Q.; Lean, H.H.; Smyth, R. CO2 emissions, energy consumption and economic growth in the ASEAN-5 countries: A cross-sectional dependence approach. Energy Econ. 2020, 85, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E., Jr. On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Capital Accumulation in the Theory of Long Run Growth; Working Paper No. 123; University of Rochester—Center for Economic Research (RCER): Rochester, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Belazreg, W.; Mtar, K. Modelling the causal linkages between trade openness, innovation, financial development and economic growth in OECD Countries. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2020, 27, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Tiwari, R.C. Application of a local linear autoregressive model to BOD time series. Environmetrics 2000, 11, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Fan, J.; Yao, Q. Functional-coefficient regression models for nonlinear time series. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2000, 95, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. Estimation and inference in large heterogeneous panels with a multifactor error structure. Econometrica 2006, 74, 967–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, G.A.; Peixoto, M.G.M.; Barbosa, S.B.; Mendonça, M.C.A.; Nogueira, T.H.; Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.A.; de Castro Júnior, L.G.; Serrano, A.L.M.; Ferreira, L.O.G. Fuel flow logistics: An empirical analysis of performance in a network of gas stations using principal component analysis and data envelopment analysis. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2024, 21, 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Guan, D.; Zheng, H.; Ou, J.; Li, Y.; Meng, J.; Mi, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q. China CO2 emission accounts 1997–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Shao, S.; Wang, P.; Guan, D. New provincial CO2 emission inventories in China based on apparent energy consumption data and updated emission factors. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Guan, D.; Hubacek, K. China CO2 emission accounts 2016–2017. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Shan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Hubacek, K. Assessment to China’s recent emission pattern shifts. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2021EF002241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Guan, Y.; Oldfield, J.; Guan, D.; Shan, Y. China carbon emission accounts 2020–2021. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 122837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K.; Saboori, B.; Soleymani, A. Economic growth and carbon emissions. Econ. Model. 2016, 53, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurohit, S.S.; Sharma, R. Impact of economic and financial development on carbon emissions: Evidence from emerging Asian economies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, D.G. Corporate Governance and Climate Change: The Banking Sector; Ceres Report; Ceres: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F.; Qian, J.; Qian, M. Law, finance, and economic growth in China. J. Financ. Econ. 2005, 77, 57–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Storesletten, K.; Zilibotti, F. Growing like China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 196–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R. Bank-based or market-based financial systems: Which is better? J. Financ. Intermediat. 2002, 11, 398–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T. The importance of climate risks for institutional investors. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1067–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities. 2020. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- He, G.; Lin, J.; Sifuentes, F.; Liu, X.; Abhyankar, N.; Phadke, A. Rapid cost decrease of renewables and storage accelerates the decarbonization of China’s power system. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2022. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Trends and Projections in Europe 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/trends-and-projections-in-europe-2025 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Gupta, N.C.; Tanwar, R.; Dipesh; Kaushik, A.; Singh, R.; Patra, A.K.; Sar, P.; Khakharia, P. Perspectives on CCUS deployment on large scale in India: Insights for low carbon pathways. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, B.G. Can We Price Carbon? MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute of Green Finance. China Green Finance Research Report 2024. Central University of Finance and Economics, 2024. Available online: https://iigf.cufe.edu.cn/info/1014/9340.htm (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Nedopil, C.; Dordi, T.; Weber, O. The nature of global green finance standards—Evolution, differences, and three models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Strategy for Financing the Transition to a Sustainable Economy. 2021. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/strategy-financing-transition-sustainable-economy_en (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Bos, K.; Gupta, J. Stranded assets and stranded resources: Implications for climate change mitigation and global sustainable development. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 56, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Meltzer, J.P.; Oppenheim, J.; Qureshi, Z.; Stern, N. Delivering on Sustainable Infrastructure for Better Development and Better Climate. Brookings Institution. 2016. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/delivering-on-sustainable-infrastructure-for-better-development-and-better-climate/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Sample splitting and threshold estimation. Econometrica 2000, 68, 575–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caner, M.; Hansen, B.E. Instrumental variable estimation of a threshold model. Econom. Theory 2004, 20, 813–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R. Quantile regression for longitudinal data. J. Multivar. Anal. 2004, 91, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canay, I.A. A simple approach to quantile regression for panel data. Econom. J. 2011, 14, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvao, A.F.; Kato, K. Smoothed quantile regression for panel data. J. Econom. 2016, 193, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, D.; Van Dijk, D.; Franses, P.H. A multi-level panel STAR model for US manufacturing sectors. J. Appl. Econom. 2005, 20, 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Loayza, N.; Beck, T. Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes. J. Monet. Econ. 2000, 46, 31–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, M.; Presbitero, A.F. This Time They’re Different: Heterogeneity and Nonlinearity in the Relationship between Debt and Growth; IMF Working Paper; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Athey, S.; Imbens, G.W. Design-based analysis in difference-in-differences settings with staggered adoption. J. Econom. 2022, 226, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Abraham, S. Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chaisemartin, C.; D’Haultfœuille, X. Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2964–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C.; Bilinski, A.; Poe, J. What’s trending in difference-in-differences? A synthesis of the recent econometrics literature. J. Econom. 2023, 235, 2218–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Bacon, A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. The Green Function of Finance: From Doctrinal History to Theoretical Modelling. Manag. World 2025, 41, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Lemieux, T. Regression discontinuity designs in economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2010, 48, 281–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M.D.; Idrobo, N.; Titiunik, R. A Practical Introduction to Regression Discontinuity Designs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, C.; Rapson, D.S. Regression discontinuity in time: Considerations for empirical applications. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Yin, J. Research on the Impact of ESG Informal Institutions on the Financial Sustainable Development of Manufacturing Enterprises—Based on Regression Discontinuity Design. Stat. Manag. 2025, 40, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Does the Increase in Pollution Levy Hinder Enterprise Exports—A Study Based on Geographic Regression Discontinuity Method. China Econ. Q. 2025, 25, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. Taking Responsibility or Free-Riding: How Does Air Pollution Affect Corporate ESG Performance? Account. Res. 2025, 1, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Keele, L.J.; Titiunik, R. Geographic boundaries as regression discontinuities. Political Anal. 2015, 23, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N.; Brandt, L.; Henderson, J.V.; Turner, M.A.; Zhang, Q. Roads, railroads, and decentralization of Chinese cities. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2017, 99, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, M. The persistent effects of Peru’s mining mita. Econometrica 2010, 78, 1863–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, A.I.; Lindo, J.M.; Waddell, G.R. Heaping-induced bias in regression-discontinuity designs. Econ. Inq. 2016, 54, 268–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Spatial Econometrics: From Cross-Sectional Data to Spatial Panels; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- LeSage, J.; Pace, R.K. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y. A Review of Frontier Theories, Methods and Applied Research in Spatial Econometrics. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2024, 46, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- LeSage, J.P.; Pace, R.K. The biggest myth in spatial econometrics. Econometrics 2014, 2, 217–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; De Jong, R.; Lee, L.F. Estimation for spatial dynamic panel data with fixed effects. J. Econom. 2015, 167, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, S.; Clemens, M.A. Blunt instruments: Avoiding common pitfalls in identifying the causes of economic growth. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2013, 5, 152–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Jin, S. Sieve estimation of panel data models with cross section dependence. J. Econom. 2012, 169, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.R.; Weidner, M. Linear regression for panel with unknown number of factors as interactive fixed effects. Econometrica 2015, 83, 1543–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbens, G.W.; Rubin, D.B. Causal Inference in Statistics, Social, and Biomedical Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, P.; Kacperczyk, M. Do investors care about carbon risk? J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 517–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, D.; Schramade, W. Principles of Sustainable Finance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Semieniuk, G.; Campiglio, E.; Mercure, J.F.; Volz, U.; Edwards, N.R. Low-carbon transition risks for finance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercure, J.F.; Pollitt, H.; Viñuales, J.E.; Edwards, N.R.; Holden, P.B.; Chewpreecha, U.; Salas, P.; Sognnaes, I.; Lam, A.; Knobloch, F. Macroeconomic impact of stranded fossil fuel assets. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y. Challenges to the development of carbon markets in China. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, W.; Zhu, B.; Wei, Y. Examining the impact factors of energy-related CO2 emissions using the STIRPAT model in Guangdong Province, China. Appl. Energy 2013, 106, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Paterson, M. Climate Capitalism: Global Warming and the Transformation of the Global Economy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ciplet, D.; Roberts, J.T.; Khan, M.R. Power in a Warming World: The New Global Politics of Climate Change and the Remaking of Environmental Inequality; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, N. A time for action on climate change and a time for change in economics. Econ. J. 2022, 132, 1259–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Theme | Representative Studies | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Development and Growth | |||

| Classical positive view | [1,26,29] | Regression analysis | Financial development promotes growth through improved resource allocation and investment |

| Challenged relationships | [30,31,32] | Threshold models | Finance-growth linkage has weakened; negative impacts beyond certain thresholds |

| Carbon Emissions and Growth | |||

| Mixed direct effects | [42,43,44] | Panel/time-series analysis | Negative, neutral, or positive effects depending on context and time horizon |

| Interaction Effects: Carbon Emissions, Finance, and Growth | |||

| Theoretical mechanisms | [5,19,22] | Theoretical models | Emissions reflect structural transformation but create transition and physical risks at high levels |

| Policy factors | [46,47,48] | Policy/regulatory analysis | Carbon pricing and green finance policies redirect capital away from high-carbon sectors |

| Methodological Approaches to Nonlinearity | |||

| Nonlinear models | [8,32,45,51] | Threshold/smooth transition/functional- coefficient models | Nonlinear relationships exist but cross-sectional dependence often ignored |

| 50 | 100 | 200 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0.1144 | 0.0436 | 0.0867 | 0.0323 | 0.0671 | 0.0274 |

| 100 | 0.0894 | 0.0286 | 0.0645 | 0.0214 | 0.0515 | 0.0200 |

| 200 | 0.0679 | 0.0217 | 0.0503 | 0.0161 | 0.0389 | 0.0136 |

| Variable | Definition | Min | Mean | Max | S.D. | Obs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 emissions in million tons | 3.5794 | 6.0196 | 8.0615 | 0.7252 | 990 | |

| y | Real GDP per capita | 6.6797 | 9.6061 | 12.1392 | 1.2492 | 990 |

| Deposits and loans per capita | 1.9194 | 5.8867 | 10.1239 | 1.8590 | 990 | |

| Imports and exports per capita | 2.3073 | 5.9329 | 9.6108 | 1.5251 | 990 | |

| Number of patents per 1,000,000 people | −0.9750 | 2.6071 | 6.8333 | 1.7825 | 990 | |

| k | Capital stock per capita | 1.5733 | 5.7334 | 8.7737 | 1.7668 | 990 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8297 *** | 0.7532 *** | 0.7765 *** | 0.5079 *** | |

| (0.0028) | (0.0090) | (0.0122) | (0.0199) | |

| 0.0859 *** | 0.0886 *** | 0.0702 *** | ||

| (0.0097) | (0.0097) | (0.0087) | ||

| −0.0241 ** | −0.0247 ** | |||

| (0.0085) | (0.0075) | |||

| k | 0.2350 *** | |||

| (0.0145) |

| Variable | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0024 | |||

| (0.0021) | |||

| 0.0191 | |||

| (0.0173) | |||

| −0.0037 * | |||

| (0.0018) | |||

| 0.4969 *** | 0.4969 *** | 0.4998 *** | |

| (0.0222) | (0.0222) | (0.0202) | |

| 0.0694 *** | 0.0694 *** | 0.0735 *** | |

| (0.0087) | (0.0087) | (0.0088) | |

| −0.0260 *** | −0.0260 *** | −0.0215 ** | |

| (0.0076) | (0.0076) | (0.0076) | |

| k | 0.2301 *** | 0.2301 *** | 0.2417 *** |

| (0.0152) | (0.0152) | (0.0149) |

| Variable | Coefficient Estimation | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0647 | (, ) | |

| (, ) | ||

| k | 0.3375 | (, ) |

| Variable | Coefficient Estimation | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1338 | (0.0004, 0.2668) | |

| 0.0372 | (, 0.1787) | |

| k | 0.5113 | (0.3549, 0.6689) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, Y.; Song, Z. Do Carbon Emissions Hurt? Novel Insights of Financial Development and Economic Growth Nexus in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411249

Qin Y, Song Z. Do Carbon Emissions Hurt? Novel Insights of Financial Development and Economic Growth Nexus in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411249

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Yiyi, and Zhihui Song. 2025. "Do Carbon Emissions Hurt? Novel Insights of Financial Development and Economic Growth Nexus in China" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411249

APA StyleQin, Y., & Song, Z. (2025). Do Carbon Emissions Hurt? Novel Insights of Financial Development and Economic Growth Nexus in China. Sustainability, 17(24), 11249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411249