Abstract

With global climate warming, reports of glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs) have become increasingly frequent, highlighting the crucial need for robust GLOF sensitivity assessment methods for disaster prevention and mitigation. A reliable GLOF susceptibility assessment method was developed and applied in the Palong Zangbu River Basin in the Nagqu region of the Tibetan Plateau, integrating Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), glacier data, remote sensing imagery, and field survey data. The assessment evaluated the potential hazard levels of glacier lakes. Between 2000 and 2023, both the number and area of glacier lakes in the basin showed an increasing trend. Specifically, the number of glacier lakes larger than 0.08 km2 increased by 32, with an area expansion of 14.17 km2, corresponding to a growth rate of 43.95%. Based on the GLOF susceptibility assessment, 15 glacier lakes were identified as potentially hazardous in the study area, with the robustness of the method validated through ROC curve analysis. Therefore, it is recommended to regularly apply this method for GLOF susceptibility assessments in the Palong Zangbu River Basin, updating monitoring data and remote sensing imagery. This research provides valuable insights for GLOF susceptibility assessments in the High Mountain Asia (HMA) region.

1. Introduction

Glacial lakes, formed by glacial processes or primarily supplied by glacial meltwater, are vulnerable to outburst flooding due to the active nature of glaciers and the instability of the moraine dams that confine these lakes [1]. Such outbursts can result in catastrophic events, including glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) and associated debris flows, which pose significant geological hazards. These disasters are often of large scale, many times greater than typical floods or debris flows, and due to their sudden onset, they leave little time for downstream warning [2]. As a result, they present a substantial threat to downstream populations and infrastructure [3]. Hydroelectric plants located directly along riverbeds are especially vulnerable, as their critical infrastructure may be directly impacted by GLOF events. Given their role in water storage, reservoirs could amplify the downstream threats posed by glacial lake outbursts [4].

In recent decades, accelerated glacier retreat driven by global warming has increased both the number and volume of glacial lakes, heightening the risk of outburst events [5]. The Palong Zangbu River Basin on the Tibetan Plateau is especially vulnerable, as abundant moisture from the Indian Ocean promotes glacier development and lake formation. With multiple hydropower projects planned in the basin, understanding the distribution and characteristics of glacial lakes is critical. Assessing their outburst potential and associated impacts provides essential guidance for hydropower planning and disaster mitigation. In China’s high-altitude regions, major infrastructure projects—such as hydropower plants, railways, and highways—are often subjected to the severe threat of GLOFs [6]. This necessitates enhanced research into the impact and mitigation strategies for glacial lake disasters. The Yigong Zangbu Basin, located in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau, is greatly influenced by Indian Ocean moisture, which supports the development of glaciers in the region [7]. Under the context of rising global temperatures, GLOFs have become a serious, unpredictable mountain hazard in this area. The characteristics of GLOFs include their sudden onset, low frequency, high destructiveness, and wide-ranging impact [8,9,10]. Historically, the Yigong Zangbu Basin has experienced several catastrophic GLOF events [11,12,13], causing significant damage to infrastructure and communities downstream [14] (Clague and Evans, 2000 [15]). For instance, on 5 July 2013, the Ranrizhi Lake in the Yigong Zangbu Basin burst, resulting in severe damage to downstream infrastructure, including bridges and roads, with direct economic losses amounting to CNY 270 million. Similarly, the 2020 GLOF event in Jinuco Lake caused severe damage to roads and bridges, resulting in significant economic losses [16]. Therefore, conducting thorough research on the spatiotemporal changes in glacial lakes and their potential impact on hydropower projects is essential for ensuring the safety and resilience of such critical infrastructure.

Traditionally, glacial lake investigations have relied on field surveys, but the remoteness of high-altitude regions and the incompleteness of historical GLOF records [15,17] have limited their adequacy; the advent of satellite-based Earth observation missions, particularly long time-series and high-resolution imagery, has nevertheless greatly improved the detection and assessment of GLOF hazards [18]. For example, Komori used imagery from Corona KH-4A, Hexagon KH9-9, Landsat7/ETM+, and ALOS/PRISM in combination with field surveys to study GLOFs in Bhutan [19]. Nie et al. [10] reviewed and verified more than 60 historical GLOF events in the Himalayas using remote sensing and field investigations, identifying several previously unreported events and correcting others. Veh et al. [20] applied automatic detection methods on Landsat imagery (1988–2016) to identify 10 previously unreported GLOF events in the Himalayan region. Liu et al. [21] identified 37 GLOF events from 33 lakes in Tibet, correcting three previously unreported events. These studies highlight the incomplete nature of existing GLOF records and underscore the need for further exploration to uncover potentially unreported GLOF events.

The triggering factors for GLOFs are classified into external factors (such as snow/ice avalanches, rainfall, rockslides, mudflows, upstream flooding, and earthquakes) and internal factors (such as the melting of buried ice within moraine dams or piping) [22]. Research indicates that snow/ice avalanches are the primary triggers for GLOFs. For instance, 34 out of 38 known GLOF events in the Himalayas were triggered by ice avalanches [10]. GLOFs are often the result of multiple interacting factors. For example, the 1988 GLOF event in Nepal’s Tam Pokhari Lake was triggered by a combination of seismic activity weakening the dam’s stability, followed by strong rainfall and a landslide that eroded the dam, causing the outburst [23]. Similarly, the 2015 GLOF event in Bhutan’s Lemthang Tsho Lake was triggered by two days of heavy rainfall, which led to the collapse of an ice dam, connecting two glacial lakes, and causing a subsequent outburst [24]. In most cases, these triggering events are sudden and difficult to monitor in real time, especially as many glacial lakes are located at high altitudes, far from populated areas. This lack of direct observation, coupled with the scarcity of definitive evidence from snow/ice avalanches, rockslides, or mudflows, means that many historical GLOF events are inferred or speculative, with ongoing debates about their true causes [25].

Early identification of potentially hazardous glacial lakes is crucial for improving disaster prevention capabilities, particularly for major infrastructure projects like hydropower plants. Early identification relies heavily on understanding the development characteristics of these lakes. As glacial lakes are typically located at high altitudes, where accessibility is limited, remote sensing has become an important tool for studying their characteristics [26]. For example, studies on glacial lakes in the Chinese Himalayas [27] and in the Hengduan Mountains [28] have utilized remote sensing for analysis. However, due to limitations in temporal and spatial resolution, remote sensing is often insufficient for comprehensive, multi-temporal studies of glacial lakes. Traditional remote sensing methods, particularly manual interpretation, can be time-consuming and prone to errors, particularly in boundary delineation [29]. To address these limitations, automated remote sensing methods for glacial lake information extraction are continuously improving, enhancing both mapping efficiency and accuracy, and supporting early identification of potential hazards [5].

In Tibet, glacial lakes that have burst are primarily terminal moraine lakes. The most common outburst mechanisms are moraine dam failure, either through internal processes or the inflow of material from upstream [30]. These material inputs typically include landslides, ice avalanches, snow avalanches, and debris from upstream GLOFs [31]. The understanding of glacial lake hazard mechanisms, distribution patterns, and disaster modes provides essential data for risk assessment models. Previous studies have mapped historical GLOF events in Tibet [32] and used remote sensing and geomorphological methods to create disaster databases for the entire Himalayan region [10], providing valuable theoretical foundations for GLOF hazard identification. Existing research has focused primarily on the Himalayan region of China [33], Nepal [31], and the Hengduan Mountains. However, most existing approaches rely solely on optical remote sensing indicators or utilize probabilistic models that do not systematically address multicollinearity, factor coupling, or regional heterogeneity. These limitations reduce robustness, particularly in complex high-mountain environments. To overcome these constraints, our study introduces an integrated framework that combines grey relational analysis with logistic regression, enabling optimized factor weighting, enhanced interpretability, and improved model stability. This design represents a methodological advance over traditional pure remote sensing extraction or single-model susceptibility assessments and offers a more reliable basis for evaluating glacial lake hazard susceptibility in data-limited alpine regions.

This study aims to systematically assess the susceptibility of glacial lakes in the Palong Zangbu River Basin to outburst flooding using remote sensing and geological engineering methods. By integrating regional geological conditions and climate change trends, the research will predict the potential risks associated with glacial lake outbursts. First, a detailed survey of the distribution and developmental characteristics of glacial lakes provides important insights into their spatial patterns and evolutionary processes. Second, the integration of remote sensing data and Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) provides a robust basis for evaluating the susceptibility of glacial lakes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

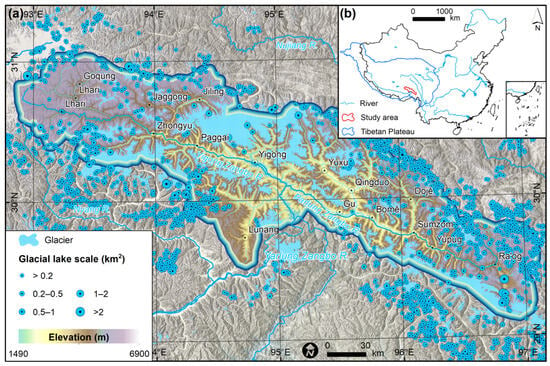

The Palong Zangbu River, located in southeastern Tibet, is a major left-bank tributary of the Yarlung Zangbo River, and its basin is the largest in terms of water volume. Originating from the Azagongla Glacier near Ranwu Town in Baxoi County, it flows northward into Angon Lake, then northwest into Ranwu Lake. It passes through Bomi and Tongmai, where it joins the Yigong Zangbu River at the Tongmai Bridge, continuing southwest to meet the Yarlung Zangbo River. The basin lies between longitudes 92°53′ E and 97°07′ E, and latitudes 29°07′ N and 31°03′ N, stretching about 430 km east to west and 110 km north to south. To the north lie the Nyainqêntanglha Mountains, separating it from the Nujiang River basin; to the south, the Gangri Garbo Mountains separate it from the Yarlung Zangbo and its tributaries; to the west, it borders the Lhasa River basin; and to the east, the Boshula Range separates it from the Nujiang basin. The basin area is 28,941 km2, with the Yigong Zangbu River Basin covering 13,787 km2. The main Palong Zangbu River extends 289 km, with a natural drop of 3360 m, an average gradient of 11.63%. The area is characterized by rugged mountains and numerous valleys, with extensive glacial and snow cover, covering about 6800 km2, the largest modern glacial area in Tibet. The region is known for its valley glaciers, cirque glaciers, and hanging glaciers, with prominent glacial erosion landforms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. Overview of the Study Area (a) Elevation, glacial lakes, and glacier distribution; (b) Location of the study area.

This study utilized multispectral remote sensing data from Landsat 5 TM, Landsat 8 OLI, and Sentinel 2A to extract glacier and glacial lake information in the Palong Zangbu River Basin from 2000 to 2023, with a spatial resolution of 10 m × 10 m. These datasets were obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS, https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and the Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn/). Historical imagery from Google Earth was sourced from BIGEMAP.

For image selection, we focused on autumn and winter (September to November) when glacial lakes exhibit relatively stable morphology. To minimize the impact of cloud cover on boundary extraction, images with minimal cloud presence were chosen. Additionally, the study used ASTER GDEM with a horizontal resolution of 30 × 30 m, downloaded from the International Data Service Platform. The ASTER GDEM was processed from global stereoscopic imagery obtained by the ASTER sensor aboard the Terra satellite, providing near-complete global coverage of terrestrial regions (https://glovis.usgs.gov/). Other auxiliary data, including the boundaries of the Palong Zangbu River Basin and lake area information, were also collected. The administrative geographic data for China was sourced from the National Fundamental Geographic Information System’s 1:4 million national database.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Identification of Potentially Dangerous Glacial Lakes

To investigate the spatiotemporal evolution of glacial lakes in the Palong Zangbu River Basin, this study employs a classification-based overlay extraction method for automated glacial lake information retrieval. By organizing and analyzing the changes in glacier and glacial lake areas, as well as their distribution characteristics over the 20-year period from 2000 to 2023, the study also explores the response mechanisms between glacial lakes and other influencing factors. The methods used in this study are described in detail below.

- Index-based Method for Extracting Glacial Lake Boundaries

- Unfrozen Frozen Lake Boundary Extraction

This study employs the NDWI method in conjunction with a thresholding approach to extract the boundaries of ice-free glacial lakes. The Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), which utilizes the ratio of the green and near-infrared bands, effectively highlights water body information in the image while minimizing the interference from vegetation. The calculation formula is as follows:

where BandGreen is the reflectance in the green band (Landsat TM, Landsat7 ETM+ band2, Landsat8 OLI band3) and BandNIR is the reflectance value in the NIR band (Landsat TM, Landsat7 ETM+ band4, Landsat8 OLI band5). The whole image is subjected to NDWI operation, and the brightness of different features is divided. Extraction of the unfrozen lake was implemented through threshold filter. This paper establishes a significant threshold value (0.28) for extraction. In this way, all ground objects except the water of the unfrozen glacial lake were filtered as the background, with only the unfrozen glacial lake remaining. Finally, the entire boundary of the unfrozen part of the glacial lake water body was obtained.

NDWI = (BandGreen − BandNIR)/(BandGreen + BandNIR)

- Single-band Threshold Boundary Extraction

After obtaining the boundaries of the ice-free portions of the glacial lakes, the boundaries of the ice-covered lakes are derived based on the spectral characteristics of the glacial lakes. Specifically, the difference in reflectance between the red and near-infrared bands for ice-covered glacial lakes exceeds a certain threshold, and their reflectance in the red band is typically greater than a specific value. Using these two spectral characteristics of ice-covered glacial lakes, Formulas (2) and (3) were developed. Continuous analysis of glacial lakes in the Palong Zangbu Basin revealed that when a = 1800 and b = 9100, the extracted boundaries of the ice-covered lakes were relatively complete. Glacial lakes are mostly formed by the accumulation of meltwater from retreating glaciers, and they are generally located near glaciers. Given that glaciers exhibit a strong reflectance in the red band, this study leverages this characteristic by setting an appropriate threshold in the red band to minimize the influence of glaciers. Using Formula (4), continuous analysis of the glacial lakes in the Palong Zangbu Basin demonstrated that when c = 12,000, the impact of glaciers on the extraction process of glacial lakes is effectively reduced.

In the formula, BandRed refers to the reflectance in the red band, and BandNIR refers to the reflectance in the near-infrared band. Since the environment surrounding glacial lakes is generally relatively flat with minimal terrain relief and typically low slopes, which are nearly zero, the shadow of mountain ridges, on the other hand, is located on the back side of the ridge, where terrain relief is significant and slope variations are pronounced. Based on these characteristics, Li Junli used DEM data to generate slope and terrain shading maps to differentiate between lake pixels and water pixels.

- 2.

- Deep Learning-Based Extraction Method

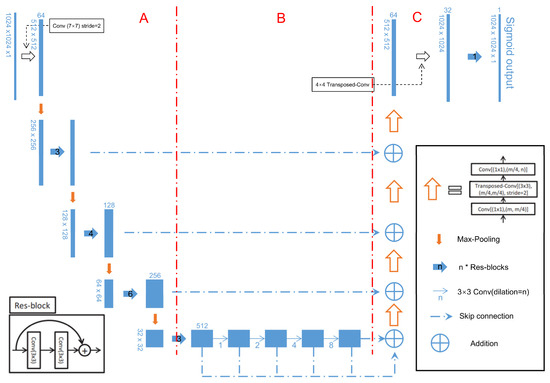

D-LinkNet is a deep learning-based semantic segmentation network originally designed for road extraction, and it was awarded in the 2018 DeepGlobe Road Extraction Challenge. UNet, as a fundamental deep learning model, has already demonstrated promising results in lake extraction. D-LinkNet, as an enhanced encoder–decoder model, retains the lightweight advantages of UNet while incorporating a pre-trained encoder and dilated convolution layers to improve efficiency and performance. Given the similarities between roads and lakes—such as connectivity, discrete distribution, and distinct contours—this inspired us to apply D-LinkNet to lake extraction (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Deep learning technology roadmap. The asterisk “*” represents the convolution operation. Part A is the encoder of D-LinkNet. D-LinkNet uses ResNet34 as encoder. Part C is the decoder of D-LinkNet, it is set the same as LinkNet decoder. Original LinkNet only has Part A and Part C. D-LinkNet has an additional Part B which can enlarge the receptive field and as well as preserve the detailed spatial information.

In this study, three complementary techniques were used to construct the glacial lake inventory: manual digitization, semi-automated classification, and DEM-based extraction. Manual digitization using high-resolution imagery provided the baseline dataset. Semi-automated classification was then applied to validate and refine the manually delineated boundaries, particularly in areas where spectral features were complex. DEM-based extraction was further employed to identify topographic depressions connected to glacial meltwater, serving as an auxiliary verification step. Some overlaps between the inventories were identified; however, these redundancies were systematically removed through a consistency-checking procedure. The final inventory was generated by integrating the results of all three methods, and discrepancies were resolved using higher-resolution satellite images and, where available, field observations. Any redundancies or inconsistencies among the outputs were systematically resolved, and the final inventory was further verified using high-resolution satellite imagery and, where available, field observations. This integrated approach ensured higher accuracy and minimized uncertainties compared with relying on a single method.

2.2.2. Susceptibility to Moraine Lake Outburst Flood Disasters

Susceptibility assessment (i.e., sensitivity analysis) evaluates the geographic and geomorphic conditions of the study area to infer the likelihood of natural disasters and provides a static basis for subsequent hazard and risk assessments. However, assessing the susceptibility of moraine-dammed lake outburst floods (GLOFs) is particularly challenging due to their nonlinear behaviour, complex triggering mechanisms, and limited environmental data, which constrains the applicability of traditional deterministic methods. To address these limitations, this study integrates the Grey Relational Model (GRM) and Logistic Regression (LR). GRM is employed to quantify and rank the influence of key environmental and geomorphological factors, while LR estimates outburst probability using a binary classification framework (1 = outburst, 0 = no outburst). Documented outburst lakes serve as training samples, and stable lakes are used for model validation. The selected factors encompass lake size, glacier–lake connectivity, moraine-dam stability indicators, and hydrometeorological conditions. The resulting probabilities are further categorized into four susceptibility levels (low, moderate, high, very high) to support effective GLOF risk identification and management.

- Grey Relational Model

Grey relational analysis is a core component of grey system theory. The grey system exists between the completely uncertain black system and the completely determined white system. Introduced by Professor Deng Julong in 1982, it is used to process partially known and partially unknown information, making it particularly suitable for addressing uncertainty under conditions of limited data and helping to extract valuable insights. Since moraine-dammed lake outburst disasters involve multiple uncertain or vague disaster-inducing factors, the Grey Relational Model is employed to identify key factors in vulnerability assessment. The model is constructed as follows:

Let there be i research objects, and each research object is composed of j evaluation factors, forming an array:

Under the influence of i study objects, select a certain sequence as the reference sequence:

Simultaneously, define the comparison sequence {}, i = 1, 2, 3 …j0:

Let the correlation coefficient be μ(k), that is, the k-point correlation coefficient is:

In the formula, || represents the absolute difference between the x0 sequence and the xi sequence at the k-point; || is the secondary minimum difference; |)| is the primary minimum difference, i.e., the smallest value of the y0 sequence difference at the k-point; represents the secondary maximum difference; ρ is the resolution coefficient, with 0 ≤ ρ ≤ 1, generally taken as ρ = 0.5. The correlation degree is represented as:

Based on the correlation degree, a sequence is formed, with the factor having the highest correlation degree placed at the front, and the correlation degree decreasing sequentially. To construct a glacier lake outburst flood (GLOF) susceptibility assessment model using the Grey Relational Model (GRM), the process begins by creating a dataset of sample glacier lakes and their corresponding susceptibility factors. These factors are normalized to make them dimensionless. A reference sequence is chosen, and the absolute differences between it and the comparison sequences (other disaster-causing factors) are calculated. The minimum and maximum differences are used to compute correlation coefficients, and the grey relational degree is determined by averaging these coefficients. Each factor’s correlation degree is calculated, ranked, and arranged in order of highest relevance to GLOF susceptibility. This process is repeated for each reference sequence, generating a correlation matrix. The final analysis is performed using this matrix, producing a ranked list of factors based on their significance to GLOF susceptibility. Subsequently, the remaining sequences are used as reference sequences, and their correlation degrees and rankings are obtained, resulting in an updated matrix for further analysis.

- 2.

- Logistic Regression Model

The logistic regression model, based on maximum likelihood estimation, analyzes the relationship between dependent and independent variables to calculate the probability of an event occurring. The dependent variable is typically binary, with 1 representing the occurrence of an event and 0 representing its non-occurrence. This model is simple, adaptable, and can handle both discrete and continuous variables, making it widely used for assessing geological hazards like landslides and debris flows. Since moraine lake outburst floods are influenced by geographical and climatic factors, logistic regression models have been widely applied in susceptibility assessments. This study uses the logistic regression model to analyze moraine lake outburst flood susceptibility, with a binary variable, Y, where Y = 1 indicates an outburst and Y = 0 indicates no outburst. The model formula is as follows:

In the formula, P is the probability value of the dependent variable occurring, which is calculated from the independent variables, i.e., the probability of glacier lake outburst, with a range of 0 to 1; x1, x2, x3, …, xn are the various evaluation factors, i.e., the independent variables; n is the number of evaluation factors; α represents the intercept; and β1, β2, β3, …, βn represent the regression coefficients of the independent variables computed by the logistic regression model. Taking the natural logarithm of both sides of Equation (11) results in Equation (12):

In the formula, p/1 − p represents the maximum likelihood; α represents the intercept; β1, β2, β3, …, βn are the polynomial coefficients of the independent variables, and x1, x2, x3, …, xn are the various evaluation factors, i.e., the independent variables.

Following the above procedure, the evaluation factors were sequentially selected using the following reference sequences: parent glacier area (X1), mean slope of the glacier accumulation zone (X2), glacier tongue slope (X3), degree of crevasse development (X4), distance from the glacier tongue to the moraine-dammed lake (X5), lake area (X6), lake water volume (X7), dam crest width (X8), dam backwater slope (X9), and the development degree of landslides along the lake banks and rear slopes (X10). Grey relational analysis was then performed for each factor, and a final factor correlation matrix was constructed. The ten evaluation factors considered in this study were selected based on their mechanistic relevance to GLOF initiation. Morphological factors, including lake area, volume, and dam height, govern water storage and hydraulic pressure on moraine dams, directly affecting their stability [34,35]. Slope characteristics, such as angle and curvature, together with glacier dynamics, including retreat rate and ice front proximity, influence the likelihood of ice or rock avalanches capable of triggering sudden lake outbursts [14,36]. Hydrological factors, including meltwater inflow and precipitation, as well as external triggers such as seismic activity and permafrost degradation, can further destabilize moraine dams [15]. Debris content and vegetation cover modify dam strength and erosion resistance, shaping the potential for dam failure [37]. Together, these factors provide a physically meaningful and empirically grounded framework for assessing GLOF susceptibility across the Palong Zangbu Basin.

In this study, grey relational analysis (GRA) and logistic regression (LR) are integrated to enhance both factor selection and hazard classification. GRA is first employed to quantify the association between each potential conditioning factor—including geomorphological, hydrological, and glacier lake dynamic variables—and observed glacial lake outburst occurrences. For each factor, the grey relational coefficient is calculated to measure its closeness to the hazard occurrence sequence, and the resulting grey relational grades are used to rank and select the most relevant factors. Factors with low grades, which contribute minimally or are highly correlated with others, are excluded, effectively reducing multicollinearity and noise. The optimized factor set is then input into LR, which estimates the probability of hazard occurrence and produces a precise susceptibility classification. By combining GRA-based factor optimization with LR-based probabilistic modelling, the framework not only improves the reliability and interpretability of factor selection but also enhances the predictive performance of glacial lake outburst susceptibility assessment.

- 3.

- Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) Susceptibility Evaluation Model

The susceptibility evaluation model was established using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 22). Before constructing the logistic regression model, a collinearity diagnostic analysis of the evaluation factors in the model is necessary. Two commonly used diagnostic methods were employed: the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance (TOL). If the VIF is less than 10 and the TOL is greater than 0.10, it indicates that there is no collinearity problem among the independent variables, meaning that the linear correlation between them is weak and will not affect the ability of the logistic regression model to provide accurate evaluations. Table 1 presents the collinearity diagnostic results for the evaluation factors. As shown in the table, none of the factors involved in the evaluation exhibit multicollinearity.

Table 1.

Evaluation sample data for glacial lake outburst floods.

After performing collinearity diagnostics, the independent and dependent variables were imported into SPSS for Binary Logistic Regression analysis. Using the forward stepwise likelihood ratio test method, the independent variables underwent multiple iterations. The results showed that the significance (Sig) values for the backwater slope of the terminal moraine (Z4) and the area of the parent glacier (Z7) were 0.186 and 0.138, respectively, both of which are greater than 0.05 and were therefore excluded due to their lack of significance. The Sig values for the remaining five evaluation factors were all less than 0.05. Thus, the final susceptibility evaluation model for glacial lake outburst was constructed using the following factors: the degree of slope and sliding development on both sides and behind the glacial lake (Z1), the average slope of the parent glacier’s snowfield (Z2), the slope of the parent glacier’s ice tongue (Z3), the degree of fissure development in the parent glacier (Z5), and the area of the glacial lake (Z6). The model is shown in Equation (14).

In the equation, x1 represents the degree of landslide and rockfall development on both shores and the back side of the glacial lake, x2 represents the average slope of the parent glacier snow area, x3 represents the slope of the parent glacier tongue, x4 represents the development degree of crevices in the parent glacier, and x5 represents the area of the glacial lake.

Building on the identification of 15 high-risk moraine-dammed lakes and their monitoring priorities, the proposed framework demonstrates transferability across High Mountain Asia through region-specific adjustments of remote sensing inputs and geomorphological parameters. Limitations include reliance on high-quality imagery and field data, and the potential omission of localized hazard triggers not captured by the selected evaluation factors. The results also inform systematic risk mitigation under climate warming, including targeted monitoring, integration with early warning systems, engineering stabilization of moraine dams, and community preparedness. These measures are increasingly critical as accelerated glacier retreat and lake instability heighten GLOF risks, supporting both scientific decision-making and practical hazard management in the region.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Glacial Lake Changes in the Palong Zangbu Basin

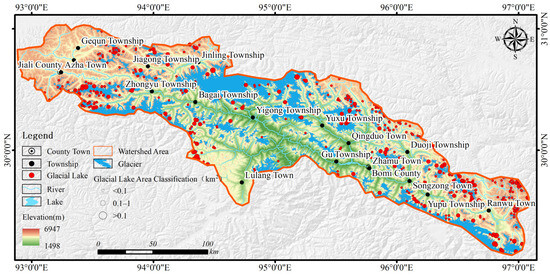

The glacial lake inventory for the Palong Zangbu Basin was derived using the D-LinkNet deep learning framework to ensure accurate and reproducible extraction. The model was trained on 193 manually annotated glacial lake samples, divided into 70% for training and 30% for validation, with a learning rate of 0.0005, batch size of 16, and 200 epochs, optimized via the ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler. Model performance was quantitatively assessed: overall accuracy 0.89, F1-score 0.88, and Kappa coefficient 0.85, indicating strong agreement with manual delineations. The confusion matrix showed that 91% of glacial lake pixels were correctly classified, with commission and omission errors below 6%. Extracted boundaries were further cross-verified with high-resolution Google Earth imagery and field survey data, confirming high spatial consistency and temporal reliability. Using the above method, glacial lake information for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 was obtained (Figure 3). The glacial lakes in the study area are primarily distributed around the Azha Town—Zhongyu Township and Duoji Township—Ranwu Town regions, with most having an area smaller than 0.1 km2. A statistical analysis of the results reveals the changes in the number and area of glacial lakes larger than 0.08 km2 between 2000 and 2023 (Table 2). Over the 20 years from 2000 to 2023, the number of glacial lakes larger than 0.08 km2 in the Palong Zangbu Basin increased by 32, and the total area increased by 14.17 km2, corresponding to a growth rate of 43.95%. This indicates a consistent increase in both the number and area of glacial lakes over the past two decades. Notably, the period between 2010 and 2015 saw the fastest growth in glacial lake area, with a growth rate of 0.51 km2·(5 years)−1.

Figure 3.

Distribution of glacial lakes in the Palong Zangbu Basin.

Table 2.

Changes in the number and area of glacial lakes from 1990 to 2020.

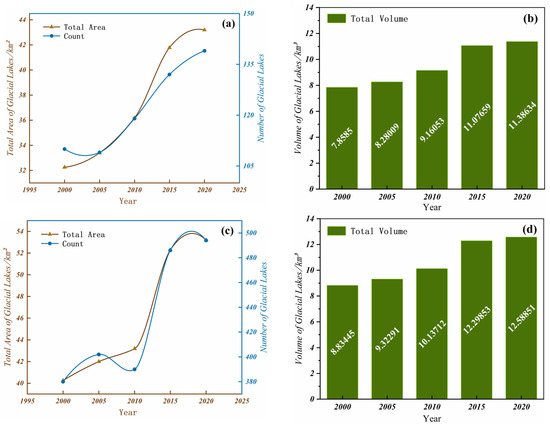

The following figure illustrates the changes in the number, area, and water storage capacity of glacial lakes larger than 0.08 km2 in the Palong Zangbu Basin from 2000 to 2023. During the period from 2005 to 2010, although the number of glacial lakes decreased, the total area and water storage capacity still increased. This indicates that the rate of glacial lake expansion far exceeded the rate of glacial lake disappearance. The number of glacial lakes larger than 0.08 km2 increased from 110 in 2000 to 142 in 2023, while the total number of glacial lakes grew from 383 in 2000 to 496 in 2023. The growth rate of the total number of glacial lakes is notably higher than the increase in the number of glacial lakes larger than 0.08 km2, suggesting that the newly formed glacial lakes over the past two decades are primarily small lakes with an area smaller than 0.08 km2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Greater than 0.08 km2 line chart of glacial lake area and number. (b) Greater than 0.08 km2 glacial lake volume histogram. (c) Line chart of glacial lake area and number. (d) Glacial lake volume histogram.

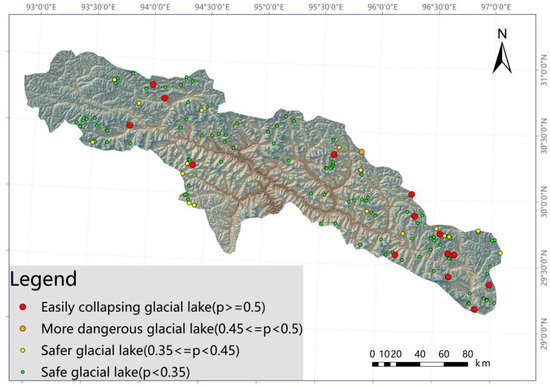

3.2. Susceptibility Assessment of GLOFs

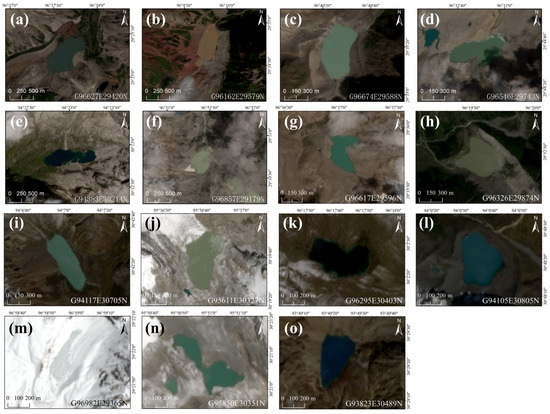

Fifteen moraine-dammed lakes with high outburst susceptibility were identified across the study area (Figure 5), based on lake expansion patterns, dam geometry, and surrounding glacier dynamics. The glacial lakes in the study area are generally influenced by upstream glacier collapses and the extension of ice tongues, with a higher risk of icefall debris collapsing into the lakes. This could trigger waves, which, in turn, may compromise the stability of the glacial lake’s terminal moraine. Most of the glacial lakes are located close to their parent glaciers, with distances ranging from approximately 300 to 500 m. Some glacial lakes even come into direct contact with the ice tongues. In the event of a glacier collapse, the debris would directly enter the lake, forming waves that severely threaten the stability of the terminal moraine. The glacial lakes studied are primarily situated in steep terrain, particularly on the northern or southwestern slopes, where the average slope exceeds 40° and is accompanied by loose deposits. These deposits are highly prone to collapsing into the lake, further exacerbating the risk of moraine failure. Many of the glacial lakes have terminal moraines made of soil and rock, which, under the influence of extreme rainfall and wave impacts, are particularly vulnerable to failure, potentially leading to glacial lake outburst floods. For example, the Gongga Cuo, unnamed glacial lake G96162E29579N, and unnamed glacial lake G96674E29588N all present a high risk of damage to the terminal moraine. Some lakes, such as the unnamed glacial lake G96617E29596N and Meiduolong Cuo, have terminal moraines located at the water outlet, where the water flow passage is narrow, increasing the possibility of moraine failure. Overall, extreme climate events and wave impacts from glacial lakes are the primary factors contributing to glacial lake outburst floods.

Figure 5.

Moraine lakes prone to outburst (a–o).

Remote sensing image analysis shows that multiple collapse paths of loose debris into the lakes are found around most of the glacial lakes, especially in areas where glacier retreat is more pronounced. As the distance between the parent glacier and the glacial lake increases and glacier stability declines, the likelihood of icefall events rises. The stability of the glacial lakes is affected by multiple factors, including glacier activity, terrain slope, deposit types, and extreme rainfall. Therefore, risk assessment and monitoring of these lakes need to comprehensively consider these factors to provide more comprehensive early warning information on potential disasters.

Gongga Cuo, Meiduolong Cuo, and Yaya Cuo Gong Glacial Lakes, located in different regions of the Palong Zangbu Basin, all face potential dangers triggered by glacier collapses, and the terrain, glacier activity, and deposit characteristics significantly influence the stability of these glacial lakes. Gongga Cuo is located in the eastern part (96.32° E, 29.87° N) at an elevation of 4124 m, with an area of 0.147 km2. Although the distance between the glacial lake and its parent glacier reaches 969 m, if a collapse occurs in the parent glacier’s ice tongue, the debris is likely to slide into the lake, generating waves that severely impact the stability of the terminal moraine. The steep terrain on the northern side of Gongga Cuo is composed of weathered debris, and the loose deposits are highly prone to collapsing, further increasing the risk of moraine failure. The outflow of the glacial lake is about 5 m wide, and under the combined impact of extreme rainfall and wave action, moraine failure is highly likely, which could lead to a glacial lake outburst flood. Meiduolong Cuo is located in the eastern part (94.12° E, 30.70° N) at an elevation of 4746 m, with an area of 0.138 km2. The upstream glacier has a relatively steep slope, and the retreat of the parent glacier is evident. Although it does not directly contact the lake, the ice tongue’s front is about 460 m away from the lake. In the event of a glacier collapse, the debris is highly likely to enter the lake, similarly triggering waves that impact the moraine’s stability. The steep terrain on both the eastern and western sides of Meiduolong Cuo and the loose deposits that are prone to collapsing into the lake pose a threat to the moraine’s stability, particularly under extreme weather conditions, which significantly increases the likelihood of moraine failure. Yaya Cuo Gong Glacial Lake is located in the western part (96.29° E, 30.04° N) at an elevation of 4878 m, with an area of 0.120 km2. This glacial lake is in direct contact with its parent glacier, with the ice tongue extending into the lake, and the glacier’s terrain is steep. Once a collapse occurs in the parent glacier, the debris is likely to directly slide into the lake, generating waves that impact the moraine’s stability. The steep terrain and loose deposits on both sides of Yaya Cuo Gong pose a threat to the moraine’s stability, particularly after a glacier collapse, as the loose debris is easily prone to collapsing into the lake, increasing the risk of moraine failure. The characteristics of these glacial lakes suggest that icefalls, extreme climate conditions, and terrain factors together may cause moraine instability, leading to a glacial lake outburst flood (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Susceptibility evaluation of moraine lake outburst.

3.3. Analysis of Outburst Susceptibility Evaluation Results

Based on statistical analysis theory and previous research, the accuracy of the logistic regression model was validated by setting a classification threshold of 50%. If the p-value is greater than 0.5, the moraine lake is classified as having experienced an outburst, with a value of 1 assigned; if the p-value is less than 0.5, the moraine lake is classified as having not experienced an outburst [38,39]. As shown in Table 3, the susceptibility evaluation model for moraine lake outbursts correctly predicted 70% of the historical moraine lake outburst samples, 91% of the non-outburst samples, and an overall accuracy rate of 84% for all samples. Previous studies indicate that when the model’s prediction accuracy for all evaluated samples exceeds 70%, the model is considered to have achieved a good performance [40]. However, eight observed outburst lakes were misclassified as “safe”, and statistical inspection of these cases reveals structural blind spots in the model. These lakes typically show moderate sizes, limited interannual expansion, and stable surface morphology, placing them within the low-risk feature space defined by surface-based predictors. Their actual failures were likely driven by factors not observable from remote sensing alone—such as subsurface moraine-dam instabilities (e.g., ice cores, weakly consolidated sediments, or internal drainage conduits) or short-term external triggers such as glacier-calving impacts or extreme precipitation events. These misclassifications therefore suggest that remote sensing-based susceptibility models may be limited in detecting failure mechanisms dominated by subsurface dam properties or rapid perturbations, indicating the value of incorporating complementary monitoring approaches (e.g., InSAR deformation or dam-structure characterization) to better constrain residual outburst risk.

Table 3.

Cross-validation results of the moraine lake outburst susceptibility evaluation model.

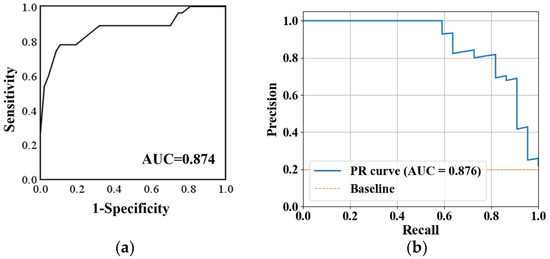

To further validate the rationality of the moraine lake outburst susceptibility evaluation model, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which is widely used in model validation, was selected. In the ROC curve, the x-axis represents the false positive rate (the false alarm rate, 1-specificity), and the y-axis represents the true positive rate (sensitivity). The closer the x-axis is to zero and the higher the y-axis, the higher the accuracy. The ROC curve generated by SPSS is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

(a) ROC Curve for the moraine lake outburst susceptibility evaluation model. (b) Precision–recall curve for the moraine lake outburst susceptibility evaluation model.

Additionally, this method uses the area under the curve in the ROC chart to represent the accuracy of the model evaluation, referred to as the AUC (Area Under Curve). A higher AUC value indicates better model performance. Intuitively, the closer the ROC curve is to the upper-left corner, the higher the accuracy of the model’s evaluation results. The AUC for the moraine lake outburst susceptibility evaluation model is calculated to be 0.874, indicating that the model performs well in predicting the target variable. Based on its sensitivity and specificity, the Youden Index is calculated to be 0.699, with the optimal cutoff point at 0.509, as shown in Table 4. The model performance was comprehensively evaluated using multiple metrics. The moraine lake outburst susceptibility model achieved an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.874, indicating strong predictive capability and excellent discrimination between outburst and stable lakes. The optimal ROC threshold of 0.509 is nearly identical to the default threshold of 0.5, which reflects the class imbalance in the dataset where stable lakes outnumber outburst lakes, while effectively balancing sensitivity and specificity.

Table 4.

ROC curve area values.

Further validation through F1-score and precision–recall analyses confirms that the selected cutoff maintains robust classification performance despite sample imbalance. The model achieves an F1-score of 0.87 at the default threshold, demonstrating an optimal balance between precision and recall. Additionally, the PR curves show consistently high precision across varying recall levels, underscoring the model’s reliability in discriminating between outburst and stable lakes even in the presence of class imbalance. These comprehensive metrics have been incorporated into the revised manuscript to provide a thorough evaluation of model performance.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Assessment Model

The Palong Zangbu River Basin, located in the southeastern part of the Tibet Autonomous Region, has experienced multiple glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs). Stimulated by the 2021 GLOF event at Gionco Lake, this study’s risk assessment methodology was implemented in 2024 through a comprehensive survey and hazard assessment in areas with a high concentration of glacial lakes in the Palong Zangbu River Basin. The GLOF event at Jinwucuo Lake in 2020 provided new insights into this assessment method, as Jinwucuo received the highest risk score in the analysis. This suggests that the methodology has the potential to yield more accurate results. Therefore, this study offers valuable clues for improving the accuracy of GLOF sensitivity assessments. Ongoing follow-up work includes gathering additional evidence related to the dominant factors and further clarifying the triggering mechanisms, with the aim of optimizing the GLOF sensitivity assessment method presented in this study (Table 5).

Table 5.

Glacier lake disaster events in the Palong Zangbu River Basin since the 20th Century.

Unlike current popular studies, such as those employing large-scale automation [49], remote sensing techniques [31,50], probability models [51], dam breach scenario simulations or reconstructions [52], and process chain simulations of glacier lake outburst floods (GLOF) [53], the assessment method used in this study presents a typical semi-quantitative approach, relying on remote sensing monitoring, field investigations, and relevant literature analysis. Although similar assessment methods have been applied in other studies [54], this study establishes a logistic regression model by analyzing the factors influencing the vulnerability to glacier lake outburst floods, selecting appropriate indicators as variables for the vulnerability assessment, and then analyzing the results.

As a foundational framework for evaluating GLOF susceptibility, indicator selection prioritizes both data availability and representativeness. Certain indicators incorporate field measurements to align with the latest survey findings in specific sub-basins of High Mountain Asia (HMA), such as recorded water storage volumes of select lakes [9,55]. However, due to the incomplete understanding of GLOFs in HMA, some uncertainty remains in the assessment framework. In basins lacking direct measurements of glacial lake water storage, lake area serves as a proxy for estimating volume, thereby increasing its weight as an indicator. Given its sensitivity to climate warming [56], lake expansion is assigned the highest weight, emphasizing its role in climate-induced GLOF events. Other indicators, including ice fissures and potential triggering topography, may be constrained by image resolution or expert interpretation. While expert assessments, informed by extensive research on glacier lake outbursts in the Tibetan Plateau [57], can improve rating accuracy, they may still be subject to biases stemming from educational background or field experience. Therefore, further validation with additional GLOF event data is needed to assess the robustness of this susceptibility evaluation method.

The triggering mechanisms of glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs) are multifaceted [58,59], involving factors like ice/snow/rock avalanches, landslides, glacier surges, and seepage expansion. These events are often triggered by a combination of interconnected factors, which may include geological processes like earthquakes or freeze–thaw weathering, as well as extreme climatic conditions, such as sustained high temperatures and sudden heavy rainfall. The assessment method in this study takes into account indicators closely associated with these factors and categorizes them into three groups: the glacier lake itself, the parent glacier, and the surrounding area of the lake (excluding glaciated regions). This classification clarifies the three types of factors that influence GLOF susceptibility. The model for evaluating the susceptibility of moraine-dammed lakes to failure was ultimately constructed using the development extent of the moraines on both shores and the rear slope (Z1), the average slope of the parent glacier’s snow accumulation zone (Z2), the slope of the glacier tongue (Z3), the degree of development of crevasses in the parent glacier (Z5), and the lake area (Z6). Nevertheless, further investigation into the triggering mechanisms is still needed. While it is difficult to accurately predict the timing of a glacier lake’s breach, the proposed method allows for dynamic assessment of the glacier lakes in the study area, providing recommendations for relevant management bodies to closely monitor potentially high-risk glacier lakes. The method is easy to apply to dynamic evaluations of glacier lakes in target basins, which contributes to regional safety and the continued refinement of basin evaluation methods. A distinctive feature of this assessment method is its potential use as a reference for similar basins or in combination with other approaches, particularly in regions with sparse data.

This study also indicates that some glacier lakes assessed as having moderate or low potential hazard still have the possibility of dam failure due to various factors such as earthquakes, avalanches, and glacier surges, highlighting the need for increased attention to lakes with high potential hazards. Furthermore, by screening key glacier lakes, this study identifies areas within the basin with higher risks of dam failure. However, the causal relationships of glacier lake failure are complex and remain difficult to assess comprehensively in quantitative terms. Additionally, key indicators such as freeboard height were not considered in the evaluation process, leading to certain uncertainties. Compared with conventional remote sensing-based monitoring or probabilistic assessments, the proposed approach represents a notable methodological advancement. By integrating geomorphological, hydrological, and glacier–lake interaction variables that have rarely been combined in previous studies, the factor framework offers a more complete representation of hazard-conditioning processes. To examine whether spatial dependence affects the reliability of the susceptibility model, spatial autocorrelation of the logistic regression residuals was assessed using Moran’s I. The test revealed no statistically significant positive autocorrelation at the 0.05 level, indicating that the residuals do not exhibit a clustered spatial structure. This result suggests that the selected conditioning factors sufficiently capture the dominant spatial patterns within the Palong Zangbu Basin and that the logistic regression model provides a stable fit without substantial unmodeled spatial dependence. Although the absence of spatial clustering supports the adequacy of the current framework, future work may benefit from incorporating spatially explicit approaches—such as spatial autoregressive logistic models or Bayesian spatial formulations—as more detailed field-based datasets become available, thereby enabling a finer characterization of localized geomorphological controls. Our proposed framework further enhances model stability by integrating grey relational analysis with logistic regression, which reduces multicollinearity and improves the reliability of factor contribution evaluations, thereby strengthening the robustness of the susceptibility predictions. Moreover, the framework demonstrates strong adaptability to the highly variable terrain and diverse lake types of the Palong Zangbu Basin, effectively mitigating the limited regional transferability often observed in single-source or single-model approaches. Collectively, these methodological enhancements improve both the scalability and the scientific value of the proposed approach.

Although the multi-source remote sensing framework developed in this study provides consistent and spatially extensive detection of glacial lakes, the absence of dedicated field observations remains an important limitation. Direct measurements of moraine structure, lake bathymetry, outlet conditions, and glacier–lake interactions were not available due to the extreme remoteness and logistical constraints of the Palong Zangbu Basin and other test regions. As a result, interpretations of certain geomorphological processes—particularly moraine stability, sedimentary composition, and short-term lake expansion mechanisms—are based solely on vertical satellite imagery and numerical inferences. This reliance may introduce uncertainties when evaluating fine-scale hydrological pathways or subaqueous features. Future work will prioritize targeted field campaigns, including UAV photography, differential GPS surveys, and bathymetric measurements, complemented by collaboration with local scientific stations. Integrating these in situ datasets with the proposed deep learning framework will further strengthen model validation, improve process-level understanding, and reduce uncertainties in hazard-related assessments.

4.2. Future High-Risk Glacial Lakes in the Basin

The triggers for glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) in the Palong Zangbu River Basin are diverse. Apart from the GLOF induced by glacier retreat and melting at Dagonglongba Glacier Lake, the triggers for moraine lakes such as Guangxiecuo can be categorized into four types: ice avalanche/ice landslide, buried ice melting, debris flow, and landslide. According to statistical analysis, there have been three GLOF events triggered by ice avalanches/ice landslides and related combinations, accounting for 43% of the total events. Two GLOF events were triggered by buried ice melting and related combinations, accounting for 29%. One event each was triggered by debris flow and landslide, each accounting for 14%. Additionally, one event occurred due to glacier lake outburst, also accounting for 14% of the total.

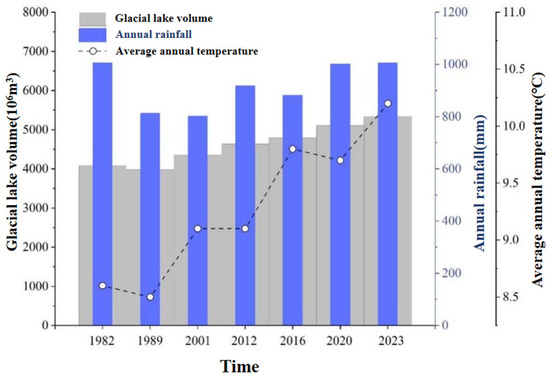

With the ongoing climate change and the occurrence of GLOFs in the Palong Zangbu River Basin over the past decade, the risk of dam failures in glacial lakes in the region has increased significantly. The climate data used in this study is based on rainfall and temperature measurements from the Bomi station. The average annual temperature in the study area has risen from 8.6 °C in 1982 to 10.2 °C in 2023, an increase of +1.6 °C, reflecting a consistent upward trend. Annual rainfall in 1982 was 1005.8 mm. From 1989 onwards, it increased from 812.2 mm to 1005.8 mm in 2023, with a total increase of 193.6 mm, showing an oscillating upward trend.

Using the formula for glacial lake volume, it is found that since 1989, the total volume of glacial lakes has increased annually, from 3979.41 × 106 m3 in 1989 to 5345.29 × 106 m3 in 2023, representing a change of 1365.88 × 106 m3 (34.32% increase) and an average annual increase of 40.18 × 106 m3. Comparisons indicate that the total glacial lake volume has grown in parallel with rising temperatures and rainfall, showing a positive correlation. To further explore this relationship, a lag-effect analysis was conducted between the annual glacial lake area growth rate and climate variables, considering 1–3-year time lags. The results show that the lake-area growth rate responds most strongly to temperature increases with a 1–2-year lag, while precipitation shows a weaker but still significant lagged effect of 2–3 years. This suggests that the expansion of glacial lakes is not only directly driven by current climate conditions but also influenced by cumulative climate effects over preceding years. Despite the increase in total volume, the average volume of glacial lakes has shown a decreasing trend annually, which is related to both the increasing number of lakes and the occurrence of GLOFs. Individual GLOFs reduce the water volume of specific lakes, while new lakes form as a result of ongoing glacier retreat and melting. In 2023, the largest glacial lake volume was 2.4 times that in 1982. Consequently, total glacial lake volume has increased, whereas average volume per lake has decreased, indicating that the observed changes are closely linked to both lake expansion and climate-driven hydrological accumulation over multiple years (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Relationship between the total glacier lake volume, precipitation, and temperature.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) highlights that global average temperatures from 1980 to 2020 were higher than those from 1850 to 1979, with a significant rise of 0.99 °C between 2000 and 2020 [60], far exceeding the increase recorded between 1850 and 1900. The High Mountain Asia (HMA) region, often referred to as the “third pole”, is particularly impacted by these changes, with glacier mass loss [61] and rapid alterations in glacial lakes [62] becoming more common. These shifts are destabilizing the region’s bedrock, talus slopes, and steep glaciers (Huggel et al., 2003 [63]). Increasing temperatures and human interventions have further heightened the region’s hydrological sensitivity and raised the risk of severe flooding events [64,65]. Numerous hazardous glacial lakes have been identified in the HMA [37,49], all of which face unprecedented challenges. To mitigate the impacts of climate change and potential future disasters, effective methods for assessing glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) susceptibility must be implemented. These methods can aid governments in decision-making and implementing strategies to reduce losses, such as real-time monitoring, artificial drainage, and evacuating at-risk populations. While large-scale studies of GLOF risks provide broad insights, a more detailed focus on local regions is necessary. Thus, establishing region-specific GLOF susceptibility assessment systems, based on natural zoning, could be advantageous. This approach would allow neighbouring regions to learn from GLOF-validated areas and refine response protocols. Our assessment method is well-suited for such research, especially as field surveys and real-time monitoring are feasible in small, populated regions.

In alpine environments, performing 3D water segmentation by jointly using DEM and optical imagery remains non-trivial because DEM vertical errors (particularly on steep moraine slopes) can distort derived hydrological gradients, while geometric misalignments between DEM grids and multispectral images may introduce artificial depressions or eliminate real ones. In this study, we adopt a DEM-first constraint to ensure that only hydrologically plausible depressions are retained, which effectively suppresses false water detections on glacier surfaces, shadowed slopes, and debris-covered ice—scenarios where spectral classifiers alone frequently fail. Our approach conceptually aligns with hydrodynamic-consistent flood segmentation methods such as Pastor Escuredo et al. [66], which stressed the need to couple image-based water detection with terrain-driven connectivity rules; however, our framework extends these ideas to high-mountain lake systems where water bodies are small, spectrally heterogeneous, and strongly controlled by micro-topography. To further contextualize our results, we note that outburst floods from high-risk moraine lakes can generate substantial downstream impacts, including channel erosion and sediment surges, disruptions to local infrastructure, and economic losses affecting hydropower and agricultural systems. These cascading effects underscore the importance of accurate lake delineation and susceptibility assessment for regional hazard mitigation.

5. Conclusions

Based on Landsat TM/ETM+/OLI remote sensing images and Sentinel data, we obtained the glacier and glacier lake contours in the Palong Zangbu River Basin from 2000 to 2023. Specifically, in 2000, there were 110 glaciers and glacier lakes larger than 0.08 km2, with a total area of 32.25 km2. From 2000 to 2023, during a 20-year period, the number of glaciers and glacier lakes larger than 0.08 km2 increased by 32, and the total area expanded by 14.17 km2, representing a growth rate of 43.95%. This indicates a general upward trend in both the number and area of glacier lakes over the past two decades. Notably, from 2010 to 2015, the area of glacier lakes increased at the fastest rate, with a growth speed of 0.51 km2·(5 years)−1. During the overall study period from 1988 to 2023, small-scale glacier lakes showed dramatic changes in both number and area, while the number of large glacier lakes remained stable, with a significant increase in area. Glacier lakes in different altitude ranges tended to expand, with slight fluctuations in number.

The following conclusions can be drawn from this study:

(1) The GLOF susceptibility assessment method, based on the Grey Relational Model and logistic regression model, indicates the presence of 15 potentially high-risk glacier lakes in the Palong Zangbu River Basin.

(2) The proposed method accounts for both the inherent susceptibility factors of glacier lakes and climate-sensitive factors, ultimately constructing a GLOF susceptibility assessment model based on factors such as the development degree of morainic lake slopes and back slopes (Z1), average slope of the glacier’s snow accumulation area (Z2), slope of the glacier tongue (Z3), degree of fissure development in the parent glacier (Z5), and morainic lake area (Z6). Therefore, this model is applicable in the HMA region, where GLOF events are common due to climate change.

(3) In the Palong Zangbu River Basin, the GONGGA Cuo and MEIDUO Long Cuo lakes have relatively high susceptibility assessment scores, and thus require close attention and monitoring. GONGGA Cuo is located in the eastern part of the Palong Zangbu River Basin (96.32° E, 29.87° N), at an elevation of 4124 m, with an area of 0.147 km2. The parent glacier has recently been retreating, and the steep slope upstream of the lake is large, with the glacier terminus 969 m from the lake. In the event of a collapse, debris could enter the lake, generating waves that might impact the stability of the dam. The terrain on the northern side is steep, and loose deposits are prone to collapse. The outflow of the lake is approximately 5 m wide and could easily breach under the influence of rainfall or waves. MEIDUO Long Cuo is located at 94.12° E, 30.70° N, with an elevation of 4746 m and an area of 0.138 km2. The parent glacier is significantly melting, and the terminus is 460 m from the lake. A collapse could result in debris entering the lake, generating waves that would affect the dam’s stability. The terrain on both the east and west sides is steep, with loose deposits prone to collapse. In contrast, other glaciers assessed as potentially medium-risk do not exhibit expansion trends, and their future potential failure risk is relatively low.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and G.Q.; methodology, C.L. and G.Q.; software, C.L.; formal analysis, G.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., G.Q., and W.L.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; supervision, S.L. and Z.L.; investigation—C.L., G.Q., S.L., Z.L. and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Project of China Power Engineering Consulting Group Northwest Engineering Co., Ltd. (Grant No. XBY-ZDKJ-2023-9).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from the Project of China Power Engineering Consulting Group Northwest Engineering Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Yao, X.; Liu, S.; Han, L.; Sun, M.; Zhao, L. Definition and Classification System of Glacial Lake for Inventory and Hazards Study. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouli, M.R.; Hu, K.; Khadka, N.; Liu, S.; Yifan, S.; Adhikari, M.; Talchabhadel, R. Quantitative Assessment of the GLOF Risk along China-Nepal Transboundary Basins by Integrating Remote Sensing, Machine Learning, and Hydrodynamic Model. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 118, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Robinson, T.R.; Dunning, S.; Rachel Carr, J.; Westoby, M. Glacial Lake Outburst Floods Threaten Millions Globally. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadka, N.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; Gouli, M.R.; Zhang, C.; Shrestha, B.; Sharma, S. Glacial Lake Outburst Floods Threaten China-Nepal Connectivity: Synergistic Study of Remote Sensing, GIS and Hydrodynamic Modeling with Regional Implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Song, C. A Regional-Scale Assessment of Himalayan Glacial Lake Changes Using Satellite Observations from 1990 to 2015. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 189, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; An, B.; Wei, L. Enhanced Glacial Lake Activity Threatens Numerous Communities and Infrastructure in the Third Pole. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, M.; Wei, J.; Guo, W. Volume Calculation and Analysis of the Changes in Moraine-Dammed Lakes in the North Himalaya: A Case Study of Longbasaba Lake. J. Glaciol. 2012, 58, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.J.; Quincey, D.J. Estimating the Volume of Alpine Glacial Lakes. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2015, 3, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, H.; Wang, Q.; Du, Z.; Hu, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q. Lake Volume and Potential Hazards of Moraine-Dammed Glacial Lakes—A Case Study of Bienong Co, Southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 2023, 17, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, S. An Inventory of Historical Glacial Lake Outburst Floods in the Himalayas Based on Remote Sensing Observations and Geomorphological Analysis. Geomorphology 2018, 308, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.G.; Delaney, K.B. Characterization of the 2000 Yigong Zangbo River (Tibet) Landslide Dam and Impoundment by Remote Sensing. In Natural and Artificial Rockslide Dams; Evans, S.G., Hermanns, R.L., Strom, A., Scarascia-Mugnozza, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 543–559. ISBN 978-3-642-04764-0. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Ke, L.; Madson, A.; Nie, Y. Heterogeneous Glacial Lake Changes and Links of Lake Expansions to the Rapid Thinning of Adjacent Glacier Termini in the Himalayas. Geomorphology 2017, 280, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Wang, N.; Chang, J.; Zhou, S.; Shi, C.; Zhao, M. Spatiotemporal Changes of Glaciers in the Yigong Zangbo River Basin over the Period of the 1970s to 2023 and Their Driving Factors. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrivick, J.L.; Tweed, F.S. A Global Assessment of the Societal Impacts of Glacier Outburst Floods. Glob. Planet. Change 2016, 144, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clague, J.J.; Evans, S.G. A Review of Catastrophic Drainage of Moraine-Dammed Lakes in British Columbia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2000, 19, 1763–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Mergili, M.; Emmer, A.; Allen, S.; Bao, A.; Guo, H.; Stoffel, M. The 2020 Glacial Lake Outburst Flood at Jinwuco, Tibet: Causes, Impacts, and Implications for Hazard and Risk Assessment. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 3159–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanghart, W.; Bernhardt, A.; Stolle, A.; Hoelzmann, P.; Adhikari, B.R.; Andermann, C.; Tofelde, S.; Merchel, S.; Rugel, G.; Fort, M.; et al. Repeated Catastrophic Valley Infill Following Medieval Earthquakes in the Nepal Himalaya. Science 2016, 351, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, N.; Liu, W.; Shrestha, M.; Watson, C.S.; Acharya, S.; Chen, X.; Gouli, M.R. Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Understanding Himalayan Glacial Lakes in a Climate Challenged World. Inf. Geogr. 2025, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, D.; Nakamura, S.; Kiguchi, M.; Nishijima, A.; Yamazaki, D.; Suzuki, S.; Kawasaki, A.; Oki, K.; Oki, T. Characteristics of the 2011 Chao Phraya River Flood in Central Thailand. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2012, 6, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veh, G.; Korup, O.; Roessner, S.; Walz, A. Detecting Himalayan Glacial Lake Outburst Floods from Landsat Time Series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 207, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, N.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, M. Glacial Lake Inventory and Lake Outburst Flood/Debris Flow Hazard Assessment after the Gorkha Earthquake in the Bhote Koshi Basin. Water 2020, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoby, M.J.; Glasser, N.F.; Brasington, J.; Hambrey, M.J.; Quincey, D.J.; Reynolds, J.M. Modelling Outburst Floods from Moraine-Dammed Glacial Lakes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 134, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, R.; Egashira, S.; Miyake, K.; Bhattarai, T.N. Field Assessment of Tam Pokhari Glacial Lake Outburst Flood in Khumbu Region, Nepal. J. Disaster Res. 2010, 5, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, D.R.; Maharjan, S.B.; Shrestha, A.B.; Shrestha, M.S.; Bajracharya, S.R.; Murthy, M.S.R. Climate and Topographic Controls on Snow Cover Dynamics in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 3873–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, R.; Egashira, S.; Adikari, Y. Prediction and Assessment of Multiple Glacial Lake Outburst Floods Scenario in Pho Chu River Basin, Bhutan. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmer, A. GLOFs in the WOS: Bibliometrics, Geographies and Global Trends of Research on Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (Web of Science, 1979–2016). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Ding, Y.; Guo, W.; Jiang, Z.; Lin, J.; Han, Y. An Approach for Estimating the Breach Probabilities of Moraine-Dammed Lakes in the Chinese Himalayas Using Remote-Sensing Data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 3109–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q. Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Net Primary Productivity in Hengduan Mountains Area, China: Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Shum, C.K.; Yi, S.; Yang, K.; Xie, H.; Feng, W.; Bolch, T.; Wang, L.; Behrangi, A.; et al. Lake Volume and Groundwater Storage Variations in Tibetan Plateau’s Endorheic Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 5550–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, X.; Guo, W.; Xu, J.; Shangguan, D.; Wei, J.; Bao, W.; Wu, L. The contemporary glaciers in China based on the Second Chinese Glacier Inventory. ACTA Geogr. Sin. 2015, 70, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounce, D.R.; McKinney, D.C.; Lala, J.M.; Byers, A.C.; Watson, C.S. A New Remote Hazard and Risk Assessment Framework for Glacial Lakes in the Nepal Himalaya. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 3455–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-J.; Cheng, Z.-L.; Su, P.-C. The Relationship between Air Temperature Fluctuation and Glacial Lake Outburst Floods in Tibet, China. Quat. Int. 2014, 321, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Iribarren Anacona, P.; Lei, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, S.; Lu, A. Integrated Hazard Assessment of Cirenmaco Glacial Lake in Zhangzangbo Valley, Central Himalayas. Geomorphology 2018, 306, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmer, A.; Cochachin, A. The Causes and Mechanisms of Moraine-Dammed Lake Failures in the Cordillera Blanca, North American Cordillera, and Himalayas. AUC Geogr. 2013, 48, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.D.; Reynolds, J.M. Degradation of Ice-Cored Moraine Dams: Implications for Hazard Development. IAHS Publ. 2000, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Haeberli, W.; Schaub, Y.; Huggel, C. Increasing Risks Related to Landslides from Degrading Permafrost into New Lakes in De-Glaciating Mountain Ranges. Geomorphology 2017, 293, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Che, Y.; Xinggang, M. Integrated Risk Assessment of Glacier Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) Disaster over the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau (QTP). Landslides 2020, 17, 2849–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Singh, S.K.; Kanga, S.; Sajan, B.; Meraj, G.; Kumar, P. Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Susceptibility Mapping in Sikkim: A Comparison of AHP and Fuzzy AHP Models. Climate 2024, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, G.; Li, W.; Han, L.; Zhang, S.; Yao, X.; Duan, H. A Robust Glacial Lake Outburst Susceptibility Assessment Approach Validated by GLOF Event in 2020 in the Nidu Zangbo Basin, Tibetan Plateau. Catena 2023, 220, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguería, S.; Lorente, A. Distribución espacial del riesgo de precipitaciones extremas en el Pirineo Aragonés Occidental. Geographicalia 2016, 37, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deji, L.; Yong, Y. A preliminary discussion on the outburst of the Midui Glacier Lake in Bomi, Tibet. Mt. Res. 1992, 219–224. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Guo, G.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, G.; Dang, C.; Liu, J. Typical glacial lakes along the southern route of the Sichuan–Tibet Highway and assessment of their outburst hazards. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2009, 16, 50–55. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lü, R. Debris Flows and Environment in Tibet; University of Science and Technology Press: Chengdu, China, 1999; pp. 69–109. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Wujin, D.; Zhuo, L. A review of glacial lake outburst disasters in the Tibet region of China. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2019, 41, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wang, W. Changes, Hazards, and Impact Analysis of Glacial Lakes in the Bosula Range of Southeastern Tibet; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Yao, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X. A review of glacial lake outburst flood events in Tibet since the 20th century. J. Nat. Resour. 2014, 29, 1377–1390. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Sun, M.; Liu, S.; Yao, X.; Li, L. Causes and potential hazards of the “7.5” glacial lake outburst flood in Jiali County, Tibet, in 2013. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2014, 36, 158–165. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W. Characteristics of the outburst mechanism of the Jiongcuo Glacier Lake in Jiali, Tibet. Geol. Rev. 2021, 67, 2. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Dubey, S.; Goyal, M.K. Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Hazard, Downstream Impact, and Risk Over the Indian Himalayas. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounce, D.R.; Watson, C.S.; McKinney, D.C. Identification of Hazard and Risk for Glacial Lakes in the Nepal Himalaya Using Satellite Imagery from 2000–2015. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, L.K.; Maiti, S. Glacial Lake Formation Probability Mapping in the Himalayan Glacier: A Probabilistic Approach. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 131, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Duan, H.; Wang, Q. Simulation of Glacial Lake Outburst Flood in Southeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau—A Case Study of JiwenCo Glacial Lake. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 819526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilca, O.; Mergili, M.; Emmer, A.; Frey, H.; Huggel, C. The 2020 Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Process Chain at Lake Salkantaycocha (Cordillera Vilcabamba, Peru). Landslides 2021, 18, 2211–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Rai, S.C.; Thakur, P.K.; Emmer, A. Inventory and Recently Increasing GLOF Susceptibility of Glacial Lakes in Sikkim, Eastern Himalaya. Geomorphology 2017, 295, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Liu, S.; Wu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, F.; Jin, H.; Gao, Y.; Yao, X. Improving the Accuracy of Glacial Lake Volume Estimation: A Case Study in the Poiqu Basin, Central Himalayas. J. Hydrol. 2022, 610, 127973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yao, X.; Duan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T. Temporal and Spatial Changes and GLOF Susceptibility Assessment of Glacial Lakes in Nepal from 2000 to 2020. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Korup, O.; Veh, G.; Walz, A. Controls of Outbursts of Moraine-Dammed Lakes in the Greater Himalayan Region. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 4145–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y.; Pu, T.; Ma, X. Rapid Changes to Glaciers Increased the Outburst Flood Risk in Guangxieco Proglacial Lake in the Kangri Karpo Mountains, Southeast Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Hazards 2022, 110, 2163–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääb, A.; Leinss, S.; Gilbert, A.; Bühler, Y.; Gascoin, S.; Evans, S.G.; Bartelt, P.; Berthier, E.; Brun, F.; Chao, W.-A.; et al. Massive Collapse of Two Glaciers in Western Tibet in 2016 after Surge-like Instability. Nat. Geosci 2018, 11, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-009-15789-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hugonnet, R.; McNabb, R.; Berthier, E.; Menounos, B.; Nuth, C.; Girod, L.; Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Dussaillant, I.; Brun, F.; et al. Accelerated Global Glacier Mass Loss in the Early Twenty-First Century. Nature 2021, 592, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]