Abstract

The role of international financial resource inflows, foreign direct investment (FDI), development foreign assistance (DFA), and personal remittance earnings (PRE) in decisive advancement toward environmental sustainability (SDG13) and economic development is increasingly recognized. However, depending on the situation, their effects on environmental outcomes vary in degree and direction, and are still subject to debate. This research examines how the three main international financial resources impact environmental sustainability, which is measured by the bio-capacity index, with a specific focus on the moderating role of corruption. The system panel generalized method of moments with balanced panel data (2001–2023) was used to attain the objectives of this study. This study focused on 28 developing Organization of Islamic Cooperation member countries because of their significant reliance on these financial inflows, regional/economic variety, and diverse levels of governance, which offer a crucial setting for evaluating the corruption moderation hypothesis. The findings reveal a comprehensive scenario of SDG synergies and trade-offs. In the base model, FDI directly improves the situation, whereas DFA and PRE are initially negligible. When considering internal economic factors, FDI and PRE greatly advance sustainability, whereas domestic financial measures such as domestic credit and fixed capital formation show adverse effects, underscoring a tension between environmental objectives and national financial systems. Importantly, the moderation analysis shows that while the advantages of FDI and PRE continue to be robust, corruption severely reduces the efficacy of DFA. To assure environmental effectiveness, these findings call for distinct policies that encourage green FDI, leverage remittances for green investments at the family level, and above all, fasten development assistance to strict governance changes.

1. Introduction

Growing ecological degradation and climate instability are critical policy concerns. An interdisciplinary understanding of the trade-offs and synergies between conserving the environment and promoting economic growth is necessary to achieve these interrelated objectives. Due to unsustainable resource exploitation and industrial development, developing nations often experience a decline in environmental quality as they pursue economic success. The power of international financial resource inflows (IFR), particularly FDI, DFA, and PRE, to influence environmental sustainability and economic development is being increasingly recognized. However, depending on the situation, their effects on environmental outcomes vary in degree and direction, and are still subject to debate, compelling vigorous quantitative analysis to pinpoint vibrant trails and universal hurdles.

FDI and Remittances are crucial for health outcomes and economic growth, especially in underdeveloped countries [1]. Numerous studies show that FDI’s environmental effect is ambiguous, with evidence of both beneficial impacts [2,3,4,5] and harmful [6], further contextualized by domestic policies, fiscal decentralization [7]. Similarly, a few studies link Remittances to increased CO2 emissions (e.g., Shah et al., 2023 in G-11 [8]; Musah et al., 2024 in ECOWAS [9]; Kibria, 2022 in Bangladesh [10]; in South Asia [11,12]), and energy consumption [13]. The influence of DFA is also context-dependent; aid for renewables can advance decarbonization [14,15], but general aid can degrade ecological quality [14], with outcomes shaped by governance, urbanization, and local objectives like afforestation [16,17,18].

The conflicting findings underscore the critical gap: a unified analysis of all three IFRs.

This research integrates these diverse factors: FDI, DFA, and PRE, along with local financial resources; foreign debt, foreign reserve, and corruption, to offer a comprehensive analysis within a unified SDG framework. This research presents a new method for assessing environmental sustainability using bio-capacity as a proxy, unlike existing studies. This integrative measure indicates a country’s ecological resource base and its ability to regenerate. Bio-capacity extends beyond conventional environmental metrics, such as CO2 emissions, by encompassing a broader ecological perspective. This approach offers an interdisciplinary metric that integrates environmental and economic considerations. Moreover, this analysis implements a pragmatic sustainability aspect, which moves beyond conceptual principles to examine how financial inflows can be tangibly harnessed to balance ecological limits with economic growth and social equity in practice [19,20].

This study focuses on nations that are members of the OICs to explore the intricate relationship between IFRs and environmental sustainability. It argues that corruption is a significant moderating element in governance quality. Since several of its member states continue to experience serious environmental deterioration despite being large recipients of various financial inflows such as foreign aid and remittances, the OIC offers an ideal sample. This creates an empirical conundrum exceedingly applicable to the attainment of the SDGs. Furthermore, the idea that corruption controls whether IFRs result in environmental decline or green growth can be robustly tested due to the bloc’s notable differences in institutional strength and degrees of corruption. Moreover, the OIC’s common sociocultural background provides a controlled environment for separating the effects of IFRs and corruption, addressing a significant gap in the literature and seeking to produce thoughtful, situation-specific policy recommendations for this strategically significant group of developing countries.

The results show a complete picture of SDG connections: FDI directly improves the situation, while DFA and PRE are initially insignificant, based on a base model. When considering internal economic considerations, FDI and PRE significantly improve sustainability, but domestic financial measures like fixed capital formation and domestic credit have negative effects, highlighting a conflict between national economic systems and environmental goals (SDG 13 Climate Action). Crucially, the moderation study demonstrates that corruption significantly lowers the effectiveness of the DFA, even when the benefits of FDI and PRE remain strong.

To prevent economic development from endangering environmental health, the findings will direct the creation of laws intended to balance financial flows with ecological sustainability.

The next section of this study starts by evaluating the literature and stipulating some theoretical background on the connection between FDI, DFA, and PRE on environmental sustainability. Then, an in-depth investigation of the FDI, DFA, and PRE on environmental sustainability is conducted. Next, an empirical investigation of the moderating impact of corruption was carried out. Finally, policy ideas are put forth considering the studies and discussions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This study examines the impact of IFRs (FDI, DFA, PRE) on sustainability within an interdisciplinary theoretical framework. Additionally, we formalise the moderating effects of corruption in these connections using institutional theory. This theoretical trapping allies with pragmatic sustainability, which recognises that the best sustainability outcome is not the boosting of each element, but a context-dependent balance moulded by stakeholder interests, institutional quality, and implementable pathways [19].

2.1.1. Fundamental Theoretical Perspectives on IFRs and Environmental Sustainability

The Environmental Kuznets Curve’s conflicting mechanisms, which balance scale (pollution from economic expansion), composition (sectoral structure), and technique (cleaner technology) effects, are used to theorise the environmental impact of IFRs. The influence of each IFR flow is hypothesized to activate primarily through one or more of these three EKC networks.

However, two opposing theories frame FDI 01. Pollution Haven Hypothesis: Rooted in factor endowment and trade theory, the PHH hypothesises that strict environmental regulations in developed nations adjust the relative advantage, ahead to the transfer of pollution-intensive industries to developing nations with laxer regulations, thereby degrading sustainability, a negative composition effect [21]. 02. Pollution Halo Hypothesis (PHH): Grounded in theories of technology diffusion and spillovers, this hypothesis argues that Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) transfer superior, cleaner technologies and management practices to host countries, enhancing sustainability via a positive technique effect [22,23]. The net effect relies on which theoretical mechanism dominates in a host-country institution’s background.

Examining DFA requires an understanding of institutional theory. The idea of assistance effectiveness expressly says that outcomes depend on the institutional context of the recipient country. The effectiveness of environmental aid is mediated by institutional quality, even though it is intended to provide positive method and composition impacts. While weak institutions result in misallocation and a failure to change production methods, strong institutions guarantee that aid is distributed effectively to green projects.

Household Economics provides a dualistic understanding of PRE: Consumption-Led Degradation: As household expenditure rises, the ecological footprint is amplified by the scale effect. Investment-Led Sustainability: Investments made by households in environmentally friendly assets, such as solar panels, have a positive technique effect that improves sustainability. The trend is theorised to rely on household preferences, access to green technologies, and the macro-institutional setting that outlines investment reassurance.

2.1.2. The Moderating Role of Corruption: An Institutional Theory Perspective

These correlations are believed to be significantly influenced by corruption, which signals institutional failure: 01. FDI and Corruption: Corruption can either reinforce the Pollution Haven Hypothesis by enabling regulatory evasion or weaken it by promoting the adoption of inferior technology [24]. 02. DFA & Corruption: Corruption acts as a serious “leakage” mechanism that results in aid funds being misallocated and diverted from their intended environmental purposes, negating any potential benefits. 03. PRE & Corruption: Compared to FDI and DFA, the PRE-sustainability link is more resilient to macro-level corruption due to the institutional bypass created by the direct-to-household nature of remittances. However, corruption can still weaken the investment-led sustainability channel by eroding public goods and market structures for green technologies.

This paradigm provides a theory-driven, testable basis for examining how corruption influences the flow of IFRs and their environmental effects by distorting their core theoretical mechanisms (scale, composition, technique).

Existing research on IFRs and the environment is extensive but fragmented, often yielding conflicting results. These conflicts are systematically related to methodological approaches, regional circumstances, and, most critically, inadequate theorisation and modelling of institutional quality. Precisely, previous studies repeatedly neglect to explicitly model how institutional failures like corruption actively alter the theoretical channels (e.g., turning a potential technique effect into a composition effect). This review aims to highlight these conflicts and strongly advocate for the theoretical and methodological significance of the current work.

2.2. Nexus Between FDI and Environmental Sustainability

The theoretical debate between the Pollution Haven Hypothesis (PHH) and the Pollution Halo Hypothesis forms a fundamental framework for research on FDI and environmental sustainability [25,26]. Empirically, the observed effect is the net result of the underlying composition and technique effects. While the PHH argues that multinational firms promote sustainability through cleaner technologies and management practices, it also posits that FDI worsens environmental quality by relocating polluting industries to countries with laxer regulations.

Empirical evidence shows a clear division heavily influenced by institutional and geographical contexts. The Pollution Halo effect is often supported by studies conducted in China, a key recipient of foreign direct investment. For example, a study by [2] found that although FDI initially increased pollution, it ultimately contributed to the adoption of cleaner technologies. Similarly, studies on China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) demonstrate positive environmental impacts for host countries in Asia and Africa, particularly under initiatives like the Belt and Road Programme [5,6]. Another study by [4], which examined OFDI’s impact on domestic environmental technology innovation through provincial panel data (2009–2017) and a modified projection pursuit model, revealed that OFDI initially suppresses innovation before becoming positive as intellectual property protection improves. These contexts suggest institutional conditions that favor the Halo mechanism.

Conversely, evidence from larger African contexts is less optimistic; a study by [26] found that FDI decreased green output, aligning more with the concerns of the PHH. This stark discrepancy underlines that the theoretical mechanism (Haven vs. Halo) stimulated is not inherent to FDI but is largely shaped by host-country circumstances, including the quality of institutions and governance [7,25]. The fact that institutional quality is treated as a background control variable rather than an active, transformative mediator is a significant weakness shared by all these investigations. Few studies conceptually analyze how a particular institutional failure, such as corruption, actively changes the balance from a halo to a haven effect, despite the recognition of the significance of governance.

This study directly addresses this gap by formally hypothesizing, through institutional theory, that corruption is a mechanism of regulatory capture that systematically biases the FDI impact towards the Pollution Haven pathway by undermining environmental enforcement and reducing the cost of polluting. This relationship is especially understudied in the OIC context. Therefore, to fill the gap, the study attempts to test the Hypothesis H1.

H1.

FDI has a significant impact on environmental sustainability in developing countries from OIC member countries.

2.3. Nexus Between Remittance of International Earnings of Immigrants and Environmental Sustainability

The best way to understand the environmental effects of PRE is through the lens of Household Economics, which offers a fundamental theoretical duality: remittances can either enable investment-led sustainability by funding green assets at the household level [11] or fund consumption-led degradation (scale impact) [9,10] by raising demand for energy-intensive goods (a micro-level scale effect).

This disparity is reflected in the empirical evidence, where results are frequently dependent on methodological approach and regional context. Remittances are often associated with increased emissions in studies conducted in areas such as Bangladesh and ECOWAS, highlighting the consumption-driven scale impact [9,10]. Remittances frequently raise household purchasing power, which drives demand for energy-intensive goods and services, contributing to increasing energy consumption and environmental degradation. To support the pollution haven theory, Musah et al. [9], for instance, used second-generation econometric approaches (DCCEMG, AMG, and CCEMG) for ECOWAS nations (1990–2017) and discovered that FDI and remittances worsen environmental deterioration. Their causality studies demonstrated a self-reinforcing loop of consumption-driven emissions by demonstrating bidirectional relationships between remittances and pollution. Similarly, Kibria [10] found asymmetric effects when using a Nonlinear ARDL (NARDL) model on data from Bangladesh (1980–2016): CO2 emissions are reduced by negative shocks and increased by positive remittance shocks. This implies that consumption is frequently given precedence over environmental sustainability in remittance-driven economic activity.

Research employing more sophisticated techniques, however, shows that the link is not always detrimental. For instance, a study of Huang et al. [11] discovered that remittances can lower carbon emissions in the presence of robust financial institutions, indicating an investment effect. Interacting elements that might change the direction of influence, like energy prices, education, and natural resources, further complicate the link [8,12,13,27]. A study of Islam [28] found that both positive and negative remittance shocks lower CO2 emissions over the long term using panel estimators for the top eight remittance-receiving nations. This relationship is further complicated by the function of complementing elements like trade, education, and natural resources. Using the Augmented Mean Group (AMG) technique in four South Asian nations (1988–2021), Li & Yang [12] discovered that while exports and total natural resources lower carbon emissions, remittances, GDP, and forest resources increase carbon emissions. Rani et al. [27] verified that financial development and remittances raise emissions, particularly when combined with the use of fossil fuels, using the FMOLS, DOLS, and FE-OLS estimators in SAARC nations (1990–2020). These results imply that remittances can perpetuate carbon-intensive economic practices in the absence of green structural changes.

Energy prices and education also have moderating effects. According to Chen et al. [13], economic growth and education raise energy consumption, but remittances decrease it. This suggests that energy-intensive lifestyles may be encouraged by education that lacks environmental consciousness. On the other hand, Shah et al. [8] used a nonlinear panel ARDL approach in G-11 countries (1990–2021) and discovered that while remittances and financial inclusion raise emissions, education has a mixed effect, lowering emissions in the short term while raising them in the long term, most likely as a result of increased consumption patterns.

The literature has gradually looked at moderators such as financial development, but it has mainly ignored the significance of institutional failure at the macro level. Understanding whether systematic corruption at the national level affects the overall environmental result of millions of micro-level remittance decisions is severely lacking. This paper presents the original idea of an “institutional bypass” mechanism, hypothesising that, in contrast to other financial flows like FDI and DFA, remittances’ environmental impact is more resistant to corruption at the national level since they go directly to people. Theoretically, this suggests the scale vs. technique effect decision at the household level is less directly distorted by grand corruption, though it may be indirectly affected by a lack of green infrastructure. With this purpose, the study attempts to test the following hypothesis, H2.

H2.

Remittance earnings have a significant impact on environmental sustainability in developing countries from OIC member countries.

2.4. Nexus Between Development Foreign Aid and Environmental Sustainability

The theory of aid effectiveness and institutional theory are the main methods used to examine the connection between environmental sustainability and DFA. The main theoretical tenet is that the effectiveness of DFA depends crucially on the recipient nation’s institutional quality to successfully generate positive technique and/or composition effects.

This institutional contingency is confirmed by a high acceptance. Studies repeatedly demonstrate that the form of help matters, with sector-specific assistance for the environment and energy being more successful [17,29]. Using the ARDL limits test method data from India (1978–2014), Mahalik et al. [30] discovered that, whereas overall foreign aid helped to reduce emissions, energy-specific aid surprisingly increased CO2 emissions.

But an even stronger conclusion is that governance has a significant impact on its efficacy. For instance, Enusah et al. [15] showed that strong institutions increase the efficacy of environmental aid, whereas Nguyen et al. [14] found that aid for trade deteriorated ecological quality, particularly in countries with weak governance, for 100 recipient countries. This aligns with institutional theory, where weak governance leads to the diversion of resources meant for technique/composition effects. Evidence of a reciprocal causal relationship between aid, emissions, and governance lends more credence to this study [18].

A recurrent concern is the significance of institutional quality. According to Ha [31], stronger governance structures lessened the detrimental impact of foreign aid on climate-related financial policies among 28 European nations between 2010 and 2021. Such results are consistent with those of Arvin et al. [18] who used VECM analysis of low/lower-middle income countries (2005–2019) to establish bidirectional causality between aid, emissions and governance, highlighting the need for concurrent institutional reforms to ensure the effectiveness of aid.

Moreover, it is crucial to consider how aid interacts with other developmental processes like urbanization. Using nonlinear panel regression in Sub-Saharan Africa, Wang et al. [16] showed that DFA may lessen the negative environmental effects of urbanization, but its efficacy took the form of an inverted U, first increasing emissions and then decreasing them. This implies that to strike a balance between urban growth and environmental sustainability, aid must be strategically distributed in conjunction with foreign investment and smart city programs. In conclusion, DFA can be a very effective tool for improving environmental quality, but its effectiveness depends on several important aspects.

Even if “governance matters,” many studies approach it as a static, broad index. Our contribution is to logically analyze the active predation and diversion mechanism of corruption, a harmful component of bad governance. This study goes beyond just asserting that governance is crucial to showing how corruption systematically destroys the aid-sustainability link by diverting funds and distorting project delivery, thereby negating the intended technique and composition effects, to provide a more accurate and useful theoretical model for the OIC context.

We drew a hypothesis, H3, to test the relationship between foreign aid and environmental sustainability in developing countries from OIC countries. This theoretical refinement aims to resolve conflicting findings by introducing a key moderating variable. Therefore, the hypotheses H4–H7 were further extended to investigate the mediating effects of corruption on the OIC economies.

H3.

Development of foreign assistance has a significant impact on environmental sustainability in developing countries from OIC member countries.

H4.

FDI × corruption has a significant impact on environmental sustainability in developing countries from OIC member countries.

H5.

Remittance earnings × corruption has a significant impact on environmental sustainability in developing countries from OIC member countries.

H6.

Development of foreign assistance × corruption has a significant impact on environmental sustainability in developing countries from OIC member countries.

H7.

FDI × corruption, Remittance earnings × corruption, and development of foreign aid × corruption have a significant impact on environmental sustainability in OIC member countries.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Selections

To examine the intricate relationship between IFR flows, environmental sustainability, and governance quality, specifically, corruption, it is strategically and methodologically justified to focus on member countries of the OICs (the list of the sample countries is added in Appendix A). Firstly, a sizable portion of the developing economies in the OIC countries are key recipients of a variety of IFR flows. Many member states still face severe environmental problems, such as high carbon emissions, deforestation, and climate change vulnerability, despite this capital inflow. This raises an urgent empirical question: why has significant financial inflow not always resulted in better environmental outcomes? This disparity supports the main research issue and raises the possibility that a mediating factor, like corruption, is impeding sustainable development.

Second, there is significant variation in the governance and institutional quality of the OIC bloc, with some nations having strong institutions and others having inadequate regulatory frameworks and high levels of corruption. This broad range makes it possible to test the main hypothesis that corruption serves as a crucial moderator and ascertain whether IFR contributes to environmental degradation or serves as a tool for green growth. Studying the OIC enables a direct examination of this mechanism, where institutional strength varies greatly. The literature repeatedly emphasizes that institutional quality is a requirement for aid efficacy [15,31].

Lastly, a controlled environment that helps isolate the effects of the variables of interest, IFR, and corruption, while partially holding other cultural and religious factors constant, is provided by the OIC’s shared socio-cultural context and common developmental aspirations, as stated in its charter and various environmental initiatives. This emphasis on a particular but varied group fills this study, employs dynamics within the OIC. This study is therefore not only warranted but also crucial since its conclusions will offer complex, situation-specific policy suggestions for efficiently allocating financial resources to attain environmental sustainability in a sizable and strategically significant group of emerging countries.

3.2. Variable Selections

To assess the association between IFRs and environmental sustainability, this study included the following variables in the analysis: FDI, PRE, and DFA as main independent variables to represent the IFRs; meanwhile, TED, STD, GFC, and DCS are internal financial resources, and EMP represents the social factor. These variables were used as control variables. This study employs bio-capacity as the dependent variable, which represents environmental sustainability. To quantify environmental deterioration, the literature has heavily relied on demand-side measures like CO2 emissions [32], the Ecological Footprint (EF) [33], and the Happy Planet Index [34], which are frequently led by the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory. These measurements are useful for monitoring anthropogenic pressure, but they only provide a demand side. By using bio-capacity (BC) as the primary indicator of environmental sustainability, this study goes beyond this traditional methodology.

BC measures the regenerative capacity of the biosphere, or an ecosystem’s potential to generate biological materials and absorb waste. In contrast, EF and CO2 emissions measure human consumption of that capacity. By concentrating on BC, we change the analytical perspective to the stock of available natural capital, which is an essential but little-studied component of long-term sustainability. Moreover, BC is a more comprehensive metric than a single pollutant like CO2. BC incorporates the productivity of crops, forests, grazing land, and fishing grounds. Therefore, BC is a more comprehensive indicator of a country’s whole ecological asset base.

A nation’s natural asset base can be directly impacted by IFRs, such as FDI, through changes in land use, resource exploitation, and infrastructure development. The condition of these assets is directly measured by BC. Therefore, examining how IFRs impact BC offers special insights into whether these IFR flows are strengthening or weakening the basic ecological basis that underpins all economic activity. Data were collected from World Bank (WB) databases and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) Global Material Flows Database, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptions of Variables and Source.

3.3. Model Specifications and Estimations

The Gretl software, version 2024, was used as an analytical tool for all the models. To estimate the core relationship between IFRs and environmental sustainability, we employed the following baseline empirical model (1)

where country and year are denoted by subscripts i and t, respectively. Following the conversion of the base model variables along with IFRs into their natural logarithm, the static model of this study is specified as follows (2):

In Equation (2), is the intercept, εit is the error term, and are the parameters to be estimated.

3.3.1. Static Panel Estimators: Fixed Effect (FE)

First, the parameters were estimated using the FE technique. The FE estimator allows the intercept to vary across nations by controlling for unobserved country-specific factors that affect the dependent variable. Controlling for time-invariant features, such as institutional quality or geographic considerations, which may differ between nations but remain constant over time, is facilitated by the FE model [35]. FE is used to check the robustness of this study.

3.3.2. Dynamic Panel Estimators: GMM

The static model is extended to a dynamic specification using [27] a system GMM (SGMM) estimation technique to enhance the analysis. The panel dataset’s characteristics, which include a large cross-section (N = 28) and a short time span (T = 15), satisfy the conditions for employing the GMM technique, making the GMM estimator crucial for this study. Dynamic GMM estimators are particularly valuable because they account for the following factors: (i) they use internal tools derived from the lag structure of the regressors to address endogeneity, which may arise from measurement errors, omitted variable bias, or reverse causality. This is especially important for our main independent variables, DFA and FDI, which could be linked to environmental impacts. Both lagged levels and lagged differences in the explanatory variables are utilized in SGMM. This approach is based on the premise that the historical values of the regressors meet the relevance and exogeneity criteria for valid instruments. The orthogonality condition is fulfilled because these lagged values are strongly correlated with the current endogenous variables (ensuring relevance), yet are unlikely to be correlated with the contemporaneous, unobserved error term in the equation (ensuring exogeneity), as past values of FDI and aid are plausibly uncorrelated with current, unobserved shocks to bio-capacity. (ii) Control for unobserved heterogeneity and error structure: SGMM estimators successfully account for serial correlation, heteroscedasticity, and unobserved country-specific heterogeneity in the error terms. (iii) Prevent instrument proliferation and use Roodman’s two-step “collapse” technique to prevent instrument proliferation [36,37]. The Hansen test for instrument exogeneity and the Arellano-Bond test for the lack of second-order serial correlation will be used to empirically confirm the validity of these instruments and the overall model specification.

The dynamic specification is given as follows (3):

3.3.3. Moderation Analysis

To further deepen the analysis, we investigate whether corruption moderates the relationship between the key IFRs and environmental sustainability. The model was modified to include interaction factors between corruption (CC) and each of the important variables (FDI, DFA, and PRE). The following is an expression for the general moderating specification (4):

where the explanatory variables are represented by , and interaction terms that capture the moderating effect of corruption are represented by to determine how CC influences the impact of FDI, DFA, and PRE on environmental sustainability, each interaction term was examined independently. In this stage, we can assess whether corruption increases or decreases the impact of key economic variables on environmental sustainability. Consequently, it offers a profound understanding of how corruption influences environmental sustainability.

3.3.4. Diagnostic and Robustness Checks

The Arellano–Bond test for autocorrelation is used in this study to verify that there is no second-order serial correlation in the differenced residuals [36,38]. The Sargan tests and Wald (joint) Test of over-identifying restrictions are also used to evaluate the instruments’ validity [39,40] to guarantee the validity and robustness of the GMM estimators.

3.3.5. Methodological Framework and Model Progression Logic

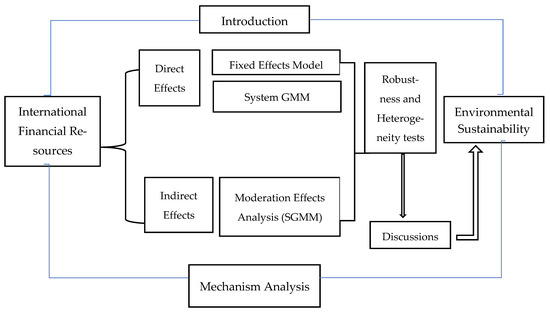

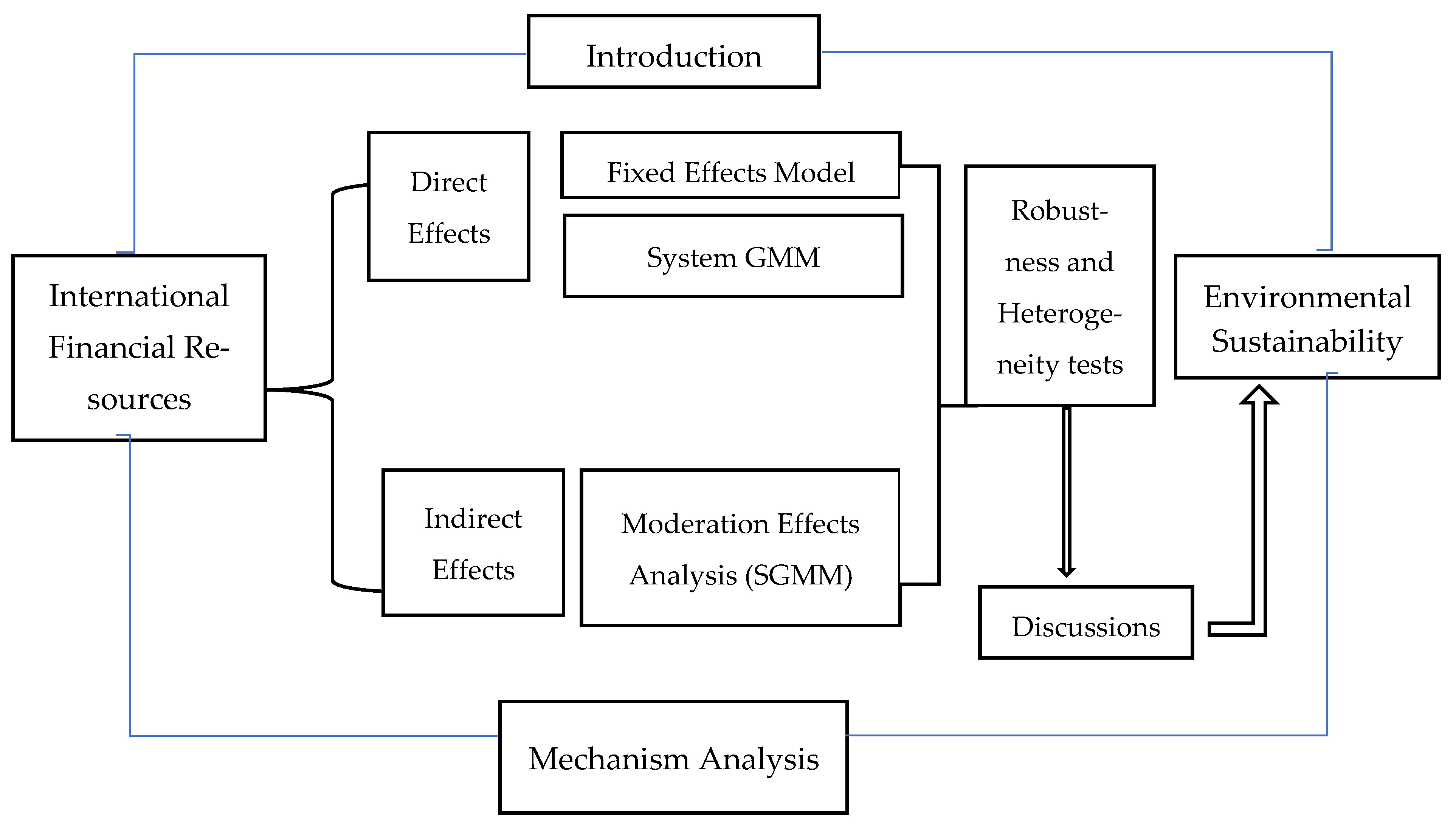

The methodological procedure is summarised in the conceptual framework of the study in Figure 1. The order of estimated models follows a rational development to confirm a robust and layered investigation:

- Fixed Model: Introduce country-specific fixed effects to control for unobserved, time-invariant heterogeneity across nations, testing the robustness of the initial findings.

- Base Model (SGMM): Recognising potential endogeneity and the persistence of environmental conditions, we extend the model to a dynamic specification. This is our preferred model as it addresses reverse causality, omitted variable bias, and introduces the lagged dependent variable (Model 1) to estimate a foundational understanding of the relationships between IFRs and environmental sustainability.

- Extended Model SGMM: This study then introduced control variables (Model 2) to understand the influence of internal factors, together with IFRs and environmental sustainability.

- Moderating Models (Interaction Effects): Building on the robust dynamic framework, we introduce interaction terms between corruption and each IFR (FDI, DFA, PRE) to create separate models (Models 3–6). This final step moves from establishing if a relationship exists to understanding how it is conditioned by the critical factor of corruption.

This multi-step approach guarantees resilience by comparing static and dynamic estimators, eliminating possible errors, and verifying the dependability of the results using diagnostic tests.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study.

4. Results and Discussions

The descriptive analysis in Table A2 (Appendix B) and the statistics on the chosen variables’ associations, along with the results of the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test, are summarised in this study before the results are discussed. Table A2 presents the summary statistics for all variables used in the study. The results reveal several key characteristics of the data. The dependent variable, bio-capacity (lnBC), has a mean of 16.27, indicating the average level of biological resource supply across the sample of developing economies. The core independent variables, Personal Remittances (lnPRE), Development Foreign Assistance (lnDFA), and Foreign Direct Investment (lnFDI), all exhibit high mean values (20.54, 20.18, and 20.51, respectively). Employment (lnEMP) is 1.31, Total reserves (lnTED), Short-term debt, Gross fixed capital formation (lnGFC), and Domestic credit to private sector (lnDCS), all exhibit low mean values (3.68, 3.25, 3.10, and 3.20, respectively). The results suggest that, on average, these international financial flows represent significant economic phenomena, while domestic financial status is likely to be a weak economic phenomenon in the sampled countries.

However, the standard deviations, particularly for lnPRE (2.34) and lnFDI (1.79), highlight notable variation in reliance on these flows across different economies. Regarding the moderation variables, the mean for the Corruption Control index (CC) is −0.77. This value, which is significantly below zero, confirms that the sample is characterised by a generally high level of perceived corruption, which is a common feature in many developing economies, as expected.

The correlation coefficients for the variables are presented in Table 2. The correlation results illustrate that lnFDI (0.77), lnPRE (0.29), lnDFA (0.06), lnCC (0.13), lnDCP (0.02), and lnSTD (0.06) have a direct link with BC emissions. However, lnEMP (−0.11), lnTED (−0.08), and lnGFC (−0.02) have an indirect association with BC. Furthermore, the coefficients of the relationship between the exogenous indicators were found to be less than 0.0.8, indicating that there are no multicollinearity issues. Following the correlation test, the ADF test was conducted to ensure the variables used in the analysis are stationary. The results show that all the variables are stationary at the level of first order, as presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Correlation Analysis.

Table 3.

Unit Root Analysis.

A fixed-effect test was used in this study to assess the robustness and support the validity of empirical research (Table A3, Appendix C). We used six models in the fixed-effect test as per the SGMM. Except for the moderating effects, the outcomes of all the models are comparable. In the fixed-effects model, FDI × CC and DFA × CC are important relationships. One could argue that models with endogeneity, measurement error, and other biases can be handled by the SGMM. Furthermore, by employing a set of moment conditions, the SGMM can take these biases into consideration and produce accurate estimates of the model parameters. A sequence of moment conditions is minimised using the SGMM until they come as near to zero as is practical. Therefore, going forward, the discussion, conclusions, and policy implications parts of this study strictly adhere to the SGMM’s findings.

4.1. Base Model of SGMM

This section illustrates the base model results, analysing the link between IFR flow, FDI, DFA, and PRE, key drivers of specific SDGs and the environmental sustainability, proxied by BC. There are conflicting theoretical predictions; the Pollution Halo Hypothesis contends that FDI could improve the environment, whereas the Pollution Haven Hypothesis indicates the opposite. The impact of PRE is unclear because of competing income and substitution impacts at the family level, whereas the success of DFA is thought to depend on the absorptive capacity of recipient countries. The result shows that only FDI has a positive relationship with environmental sustainability. DFA and PRE are insignificant.

The “Pollution Halo Effect” in the chosen developing nations is strongly supported by the statistically significant and positive relationship between FDI and environmental sustainability. This result is consistent with theories of conditional convergence and technology transfer, indicating that multinational corporations (MNCs) contribute better, environmentally sound technologies (ESTs) and management techniques that improve the production function of the host nation. The main cause of this finding is the introduction of advanced ESTs and management techniques into host nations by MNCs, which frequently outperform local norms in terms of pollution control and energy efficiency [41,42]. This has a positive technique effect where the scale of increased economic activity is outweighed by cleaner production methods [43]. This fundamental discovery in the context of the OIC indicates that, overall, the entering FDI is bringing in cleaner industrial capabilities rather than being mostly of the “pollution-haven” variety. This preliminary finding establishes a crucial baseline and shows that these financial flows could transfer green technology.

The statistically negligible correlation between environmental sustainability and DFA implies that aid flows have not consistently resulted in better environmental results for the chosen nations. This can be understood through the lens of Absorptive Capacity Theory, which suggests that the reoccurrences of IFR inflow weaken beyond a country’s institutional and technological capability to develop them commendably.

This is probably because a significant amount of DFA is distributed to more general sectors like infrastructure, health, and education rather than being specifically designated for environmental initiatives and is subject to structural issues in recipient countries, such as institutional weakness, which can hinder its effectiveness [44,45]. Therefore, the results highlight the crucial importance of underlying institutional integrity rather than supporting the premise that DFA simply translates into increased environmental public goods.

PRE and environmental sustainability do not significantly correlate. This impartial result reveals the anxiety between microeconomic theory’s income effect (which could fund cleaner consumption) and scale effect (which increases overall consumption). This insignificance can be explained by conflicting behavioural forces: remittances may facilitate investments in cleaner cooking fuels, energy-efficient appliances, and better housing, which represent a positive technique effect, yet they may also finance increased consumption of goods and energy (a scale effect that undermines sustainability) [46,47,48]. Since these conflicting household-level behaviours probably cancel each other out, the overall macroeconomic impact is unclear, and their diffuse impact is difficult to capture in an aggregate model [49].

These outcomes emphasize a pragmatic sustainability awareness: achieving environmental purposes compels identifying which financial flows bring solid green outcomes and which involve balancing institutional or policy interferences to recognize their potential [19].

In a nutshell, FDI emerges as the main direct driver of environmental sustainability in the initial definition of the base model, which provides a fundamental hierarchy among IFR inflow in the OIC context. The fact that DFA and PRE are insignificant in this model does not rule out their potential; rather, it suggests that their impacts are more complicated and dependent on other factors like the domestic economic structure and, as will be severely analysed later (Models 2–6), the widespread impact of corruption.

4.2. Extended Model with the Incorporation of Internal Economic Variables and SDG

This section expands the quantitative analysis by incorporating other internal economic variables such as employment, Total reserves (% of Total External Debt), Short-term debt (% of total reserves), Gross fixed capital formation (% of GDP), and Domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP). It offers an interdisciplinary investigation of how internal financial structures mediate the relationship between IFR flow and environmental sustainability (SDG 13). The results demonstrate that FDI, PRE, and EMP (employment) have a positive and significant effect on the sustainable environment, as shown in Table 4, in Model 2.

Table 4.

Empirical Results of System GMM and Robust Test Results.

Meantime, total reserves, short-term debt, gross fixed capital formation, and domestic credit to the private sector have a negative and significant impact on the sustainable environment in selected countries.

In terms of economics, the addition of these control variables offers a more comprehensive view of these economies’ financial structures and production functions, enabling a more precise isolation of the IFR effects. When the domestic economic backdrop is considered, the positive and significant coefficients for FDI and PRE in Model 2, as opposed to their mixed findings in the base model, indicate that their positive environmental benefits are more completely realized. From a pragmatic sustainability viewpoint, these outcomes underline the significance of domestic economic structures in mediating the environmental impact of IFR flows, highlighting that application background establishes whether financial resources translate into balanced triple-bottom-line outcomes [19,20].

FDI’s ongoing positive upward trend, when combined with domestic controls, adds credence to the “Pollution Halo Effect.” It suggests that, regardless of domestic financial circumstances, the technological transfer and improved environmental standards connected to international firms are strong forces behind sustainability. This is consistent with new research that indicates FDI in developing nations is increasingly flowing into greener industries and is subject to strict environmental, social, and governance (ESG) requirements from investing companies [41,50]. This positive FDI impact within the OIC is evidence of a shift in the organization’s makeup toward environmentally friendly industries like waste management and renewable energy. Global ESG regulations and strong national initiatives, like Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the UAE’s Masdar City, Egypt’s Benban Solar Park, and significant renewable projects in Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and Indonesia, are the driving forces behind this.

One important finding in Model 2 is the positive relevance of PRE. It suggests that the domestic economic context acts as a mediator between remittances and their environmental impact. A theory that makes sense is the “Investment Effect.” This result is consistent with theories of liquidity constraints; by giving households non-debt funding, remittances mitigate credit market failures and make previously unaffordable investments in sustainable technologies possible. Remittances may bypass established banking channels to directly finance green initiatives at the home level when variables such as local credit are considered. Remittance revenue enables families to purchase energy-efficient appliances, water purification systems, and cleaner energy sources (such as moving from biomass to LPG), which directly improve the local environment [50,51]. Due to intimate family relationships, the “Investment Effect” is more pronounced in the OIC setting, where senders frequently focus remittances on environmentally friendly household improvements.

The positive link between employment and environmental sustainability may reflect an “Informal to Formal Transition.” This can be explained via the framework of structural change theory, economic progress entails shifting workers from conventional, resource-intensive industries to more productive, frequently less polluting industries. As employment increases, particularly in formal sectors like services and light manufacturing, it moves labor away from more environmentally destructive informal activities such as subsistence agriculture, illegal logging, or artisanal mining. Formal employment is also associated with higher productivity and often more regulated, less polluting production processes than informal counterparts, contributing to overall sustainability [42].

The internal financial variables’ glaringly negative coefficients highlight the possible environmental implications of specific forms of financial development and economic expansion in developing nations. These findings raise doubt on the notion that financial development inevitably improves the environment and instead lend credence to the “financial resource curse” theory, which holds that in the lack of rigorous environmental standards, IFR inflow encourages polluting activities.

Total Reserves and Short-Term Debt have a negative association with sustainability, which suggests a possible “Policy Trade-off.” Governments may be taking public monies away from important environmental protection and green infrastructure projects in favor of increasing their foreign exchange reserves to protect against external shocks. This is a frequent practice in developing countries. Similarly, macroeconomic fragility is indicated by a high short-term debt to reserve ratio. Governments are likely to put short-term economic stability and debt repayment ahead of long-term environmental objectives in such a setting, which could result in a loose enforcement of environmental laws to draw in immediate investment [52]. This embodies a straight trade-off between the financial resilience aspects of SDG 17 (international partnership) and the objectives of SDG 13.

There is a negative impact on gross fixed capital flow, which gauges domestic investment in tangible assets like machinery and infrastructure. This clearly indicates that the investment’s nature in the chosen nations is primarily “brown” rather than “green.” Without sufficient environmental protections, investment is probably going toward carbon-intensive industries like heavy industry, fossil fuel-based transportation networks, and traditional energy. This result supports research demonstrating that capital formation in poor economies frequently duplicates polluting developmental routes in the absence of robust green policy directives [53]. In contrast with the findings of [45,54], capital formation appreciably boosts environmental quality by dropping CO2 releases in G7 nations.

The domestic credit negative sign is very instructive. It questions the idea that improved environmental results are a direct result of financial progress. Rather, it shows that the banking industry in the countries under study is mostly financing private companies that are involved in traditional, and perhaps polluting, economic activities. Finance for extractive industries, non-green manufacturing, and consumption-led lending that increases demand for energy-intensive products are a few examples of this. This research backs up the “Scale Effect” theory of financial development, which holds that before economies shift to a cleaner structure, credit expansion first drives environmentally harmful industry expansion [55].

For the extended model, which adds the crucial moderating variable of corruption, this creates the ideal environment. It is conceivable that corruption serves as the “missing link,” which would account for the DFA’s ineffectiveness and the failure to realise the anticipated beneficial consumption shifts from PRE.

4.3. Moderation Role of Corruption Model

This section presents the quantitative results of our investigation into how corruption, a major systemic obstacle, influences the relationship between IFR flows and environmental sustainability. While assessing corruption’s moderating effect, the interaction terms for FDI × Corruption, PRE × Corruption, and DFA × Corruption were all statistically insignificant in the initial Models (3, 4, and 5), which evaluated the moderating effects separately. A more complex picture emerged from Model 6, which simultaneously included all three interaction terms. Although the interactions between FDI and PRE were negligible, the relationship between corruption and DFA was found to be highly unfavourable in this comprehensive model. These outcomes provide valuable insights into the various ways corruption impacts progress towards achieving the SDGs.

Theoretically, these findings deepen the discussion of the “grease the wheels” versus “sand the wheels” debate on corruption, illustrating a clear hierarchy in how different financial flows interact with institutional quality.

Based on the negligible FDI × Corruption interaction, the beneficial “Pollution Halo Effect” of FDI demonstrates a moderately strong interaction between SDG 9 and SDG 13, which is partly resilient to corruption as a systemic barrier. The theory of firm-specific advantages helps explain this; multinational corporations’ (MNCs) global reputational capital and proprietary technologies act as buffers against local institutional weaknesses, allowing them to maintain internal environmental standards. This may be due to internal MNC factors that are partly unaffected by corruption in the host country. Increasingly, international investors and their parent companies are exerting pressure on multinationals to adhere to global Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards [47]. Their adoption of greener technologies often results from global corporate efficiency and policy, which are difficult to negotiate with local authorities. Essentially, compared to public funds, technology transfer might be “sticky” and less vulnerable to corruption-related diversion or erosion. The nature of FDI further reinforces this resistance to corruption. If, as previously proposed, significant FDI in OICs is directed towards green technology sectors, these projects typically involve sophisticated, proprietary technologies overseen by parent companies and international partners. Since these investments are less flexible and less attractive targets for corrupt activities, owing to the intense external oversight and technical complexity, they are less susceptible to systemic corruption issues.

Similarly, the direct, household-level nature of remittance flows explains the negligible PRE × Corruption interaction. Remittances, being private transfers, are less vulnerable to rent-seeking behaviour affecting public and corporate channels. This aligns with the concept of “social remittances” and the tendency to avoid formal institutions. The direct relationship between PRE and sustainability (a synergy between SDG 1 and SDG 13) operates through a channel that largely bypasses corrupt bureaucratic organisations. Remittances are sent directly to families, avoiding official project implementations and government processes. Their utilisation for small-scale investments or cleaner consumption (such as purchasing LPG) is less likely to be directly intercepted or altered by systemic corruption, as they are not routed through government institutions susceptible to graft. The environmental effects of PRE are further underscored by household preferences than by institutional quality; national-level corruption indexes are less able to moderate it [56]. This straightforward, unofficial channel offers a convincing explanation for why corruption does not compromise PRE’s advantages. The money goes straight to end consumers, whose purchasing decisions on clean energy and energy-efficient equipment are not influenced by corrupt middlemen, bypassing the official financial and political channels where corruption is most deeply ingrained.

The DFA × Corruption interaction term’s significant negative coefficient is the main finding of Model 6. This suggests that the quality of governance has a significant impact on the effectiveness of the DFA (A key tool for SDG17), and that corruption serves as a perverse filter, reducing or even undoing the potential benefits it could have for the environment (SDG 13). In terms of the efficacy of aid, this finding strongly supports the “Sand the Wheels” theory. Since the DFA is administered through public channels, it is extremely vulnerable to corruption.

Moreover, this outcome is an unambiguous economic establishment of the “public choice” hypothesis of corruption, which holds that rent-seeking officials drain public resources for private benefit and cause a catastrophic failure in the public goods provision mechanism or environmental sustainability.

According to the negative moderation effect, in severely corrupt settings. This finding is in line with the study of [57], corruption straight obstructs growth concerning the public poverty decline goals of both donor assistance and aid beneficiary nations. Aid funds designated for environmental initiatives (such as waste management systems, forest protection, and renewable energy plants) may be diverted for personal benefit, decreasing the amount of resources being used for their intended use [58]. This misallocation represents a straight disappointment in translating financial resources into tangible SDG progress. Illegitimate officials can redirect aid contracts away from companies with the strongest technical and environmental qualifications [59] and toward politically connected but ineffective companies. This leads to poor initiatives that do not have any positive effects on the environment. Even with proper funding allocation, corruption can result in careless oversight and enforcement of project requirements, enabling contractors to skimp on environmental protections with no repercussions.

It is important to note that this effect is only noticeable in Model 6, when all moderators are considered. This methodological insight highlights the significance of an integrated, interdisciplinary enumerative methodology for exposing complex systemic interactions. It implies that when evaluating the relative efficacy of various IFRs, corruption’s impact is most noticeable. The detrimental impact of corruption on the DFA may be obscured or confused by other factors when examined separately (Model 5). However, the special susceptibility of aid to corrupt institutions is brought into stark relief when compared to the more robust channels of FDI and PRE. A strong, empirically supported argument for adapting development techniques to governance environments is provided by this comparative analysis. According to the findings, coherent policy frameworks must channel development assistance through governance-sensitive mechanisms while utilising the inherent resilience of private and household-level flows. A summary of Hypothesis Tests and the Results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of Hypothesis Tests and the Results.

Our hierarchical findings, which show that DFA is particularly susceptible to corruption, PRE indicates a context-dependent beneficial impact, and FDI exhibits a corruption-resilient “Halo” effect, offer a sophisticated theoretical answer to contradictory patterns in the existing research. First, the recurrent positive effect of FDI supports the technology-driven Pollution Halo Hypothesis prevalent in studies of monitored nations [2,5,6], while its aversion to corruption indicates why this finding contradicts Pollution Haven outcomes in weaker institutional settings [26]: global ESG standards and specific benefits of businesses may guard against local institutional weakness [60]. Second, the improvement of PRE from insignificant in the base model to significantly positive in the extended model correlates directly with the conflict in Household Economics [9,11]; it suggests the positive ‘investment effect’ may predominate the ‘scale effect,’ but only when mediated by a favorable domestic economic structure, an essential requirement frequently neglected in previous macro-level studies. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the substantial negative moderation of corruption on DFA provides empirical support for the long-theorized but challenging-to-isolate “leakage” mechanism of institutional theory [57,58]. This advances beyond basic claims that “governance matters” to illustrate how a single institutional failure actively undermines a specific SDG instrument, hence presenting a more precise theoretical model than investigations relying on general governance indices [18,31]. By treating corruption as an active moderator instead of a passive control, this work overcomes important discrepancies among previous research and provides an obvious structure in the institutional sensitivity of international financial flows. This hierarchy of corruption’s impact reflects a pragmatic sustainability principle: successful sustainability execution obliges consideration of which networks are institutionally vigorous and which are weak to governance failures, enabling smarter, context-sensitive policy design [19,20].

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study employed a dynamic panel data approach to explore the complex and nuanced relationships between IFRs and environmental sustainability among selected OIC nations, a choice justified by their structural reliance on these financial flows and significant variation in governance quality. Grounded in a pragmatic sustainability approach, this research’s outcomes emphasize that achieving SDG 13 obliges balancing environmental, economic, and social priorities through stakeholder-sensitive, implementable policies tailored to the distinct governance and economic contexts of OIC countries. Six models were utilised to meet the objectives, beginning with a basic model that included fundamental IFRs, progressing to an extended model that incorporated internal economic factors, and culminating with a series of models assessing the moderating influence of corruption.

Our analysis yields numerous significant theoretical and empirical insights. First, the results indicate that FDI acts as an intermediary for positive environmental outcomes, likely through technology transfer, which robustly supports the Pollution Halo Hypothesis in this context. This finding, consistent across all model configurations, suggests that the composition of FDI in these OIC countries is more skewed towards industries that integrate better environmental technology and practices, probably driven by global ESG standards.

Second, the study clarifies the conditional nature of other financial flows, offering a thoughtful theoretical explanation for the diverse estimation results. The effectiveness of development foreign aid (DFA) is critically dependent on solid institutions, as its impact is significantly undermined by corruption. This starkly illustrates the public choice theory, where rent-seeking behaviour diverts public funds, thereby crippling progress on SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) and, by extension, SDG 13 (Climate Action). Conversely, remittances (PRE) influence household-level investments, which are less susceptible to macro-level institutional failures. This private network openly supports SDG 1 (No Poverty) and can be influenced for SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) through decentralized investments, demonstrating resilience where public institutions are weak.

Third, this study enhances the understanding of finance and environmental interactions by demonstrating how the structure of domestic financial systems can create important trade-offs. The negative coefficients observed for domestic credit and fixed capital formation are not merely statistical artefacts but empirical evidence of the “financial resource curse” in an environmental context. They show that without strong green policy directives, domestic financial systems tend to drive a scale effect of polluting economic activities, directly threatening environmental objectives and designing a serious trade-off between short-term economic growth, Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8) and long-term environmental health (SDGs 13).

The extended model uncovered a key synergy; when controlling for the domestic economic structure, the positive impacts of FDI and PRE were amplified, whereas internal financial variables exhibited significant negative effects. This highlights a tension where international private flows promote sustainability (SDG 9, Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure & Climate Action), yet domestic financial systems currently act as a barrier, exposing the establishment of “SDG trade-offs” within the national economy itself.

An extensive understanding of how governance influences financial flows was achieved through the moderation analysis. The path to accomplishing environmental goals (SDG 13) is intrinsically related to the quality of governance (SDG 16), and this gradation of sensitivity to corruption is a crucial understanding for planning SDG finance. These findings immediately lead to the following evidence-based policy recommendations, which are intended to manage trade-offs and optimize SDG synergies:

The study’s quantitative findings provide the world community and policymakers in OIC nations with important, evidence-based recommendations for designing coherent development strategies. A multifaceted strategic approach is required due to the unique functions of different financial flows and the crucial impact of domestic governance. To harness positive forces and prevent negative repercussions on environmental sustainability, and to steer SDG synergies and trade-offs, the following policy implications are suggested.

Instead of taking a general approach to foreign capital, policymakers need to develop methods that are specific to each kind of IFR flow. OIC nations should aggressively work to develop an alluring environment for sustainable investment to promote Green FDI, whose strong and beneficial effects are comparatively resistant to corruption. This can be accomplished by creating “Green FDI Promotion Packages” that offer tax breaks for renewable energy projects and expedited clearances for sustainable technologies, thereby establishing the synergy between SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). At the same time, environmental regulations can be strengthened to prevent a race to the bottom and lock in the “Pollution Halo Effect”.

Additionally, governments should use their direct household-level influence to harness PRE for decentralised green projects by developing financial instruments such as “Green Remittance Bonds” and providing subsidised loans for energy-efficient appliances. This will increase the capital’s beneficial technique effect and influence the bond between SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 13. Above all, the discovery that corruption seriously jeopardises the DFA necessitates a fundamental change in the way aid is managed. While recipient governments must use the DFA as a catalyst to strengthen institutional capacity and show a commitment to anti-corruption, donor institutions must tie the DFA to governance reforms by tying aid to transparency measures like independent audits and civil society monitoring.

The detrimental effects of domestic financial factors highlight the pressing need to match environmental objectives with national economic ambitions. Central banks and financial authorities must put in place thorough Green Finance Frameworks to offset the negative impacts of domestic credit and investment trends that support polluting businesses. Redirecting capital from brown to green sectors has been demonstrated through the implementation of statutory Green Credit Guidelines, which mandate that banks report on the environmental risk of their loan portfolios and establish goals for funding sustainable businesses.

At the same time, it is crucial to prioritise investments in low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure and to require Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs) for all major public infrastructure projects to encourage Sustainable Gross Fixed Capital Formation. Furthermore, incorporating “Green Budgeting” practices into fiscal policy is necessary to address the trade-off between accumulating reserves for macroeconomic stability and environmental health.

Since this study emphasises that strong institutions are an unavoidable requirement for successful policy implementation, the imperative need to strengthen governance serves as the foundation for all other recommendations. Prioritizing anti-corruption and transparency is a cross-cutting necessity due to the moderating influence of corruption, especially its ability to offset the advantages of development aid.

Since transparent institutions have been shown to increase the effectiveness of environmental expenditures and regulations, the effectiveness of policies intended to leverage IFRs, or green domestic financial systems, will ultimately be seriously jeopardised in the absence of this fundamental pillar of institutional integrity.

This study is not exceptional from limitations. The mechanisms which allow these resources to affect the environment may be somewhat susceptible to corrupt practices, or at the very least, the consequences are not deliberately altered by the level of corruption in the way it is conducted, as suggested by the lack of a significant moderating effect of corruption on the FDI-Sustainability and PRE-Sustainability relationships. The intricate relationships between various money flows and governance might be further examined using more detailed, sub-national, or sector-specific quantitative data on corruption, which presents both a methodological constraint and a promising direction for future research. To capture the corruption, some other direct and indirect measures can be incorporated in future studies using disaggregated indices or firm-level surveys to improve the computation of this systemic obstruction. This study can be extended to other regions, such as SARRCs, African countries that rely more on IFRs, empowering a virtual quantitative analysis of how diverse official and economic settings outline the sustainability outcomes of IFR flow.

Funding

This research project was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R865), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is openly available and was downloaded from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 3 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R865), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of the Sample Countries.

Table A1.

List of the Sample Countries.

| Bangladesh | Djibouti | Guinea | Kazakhstan | Maldives | Togo |

| Azerbaijan | Egypt | Guyana | Kenya | Pakistan | Uganda |

| Bosnia | Gabon | Indonesia | Kyrgyz Republic | Sudan | Uzbekistan |

| Cambodia | Gambia | Iraq | Lebanon | Tajikistan | |

| Comoros | Ghana | Jordan | Malawi | Tanzania |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Descriptive Analysis.

Table A2.

Descriptive Analysis.

| Variables | Observation | Mean | Std. Dev | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnBC | 420 | 16.27 | 1.66 | 12.31 | 19.63 |

| lnPRE | 420 | 20.54 | 2.34 | 0.69 | 24.17 |

| lnDFA | 417 | 20.18 | 1.35 | 16.09 | 22.79 |

| lnFDI | 400 | 20.51 | 1.79 | 12.15 | 23.95 |

| lnEMP | 420 | 1.31 | 0.83 | −1.51 | 3.06 |

| lnTED | 420 | 3.68 | 1.04 | −0.24 | 7.86 |

| lnGFC | 420 | 3.25 | 4.44 | −4.61 | 24.28 |

| lnDCP | 420 | 3.10 | 0.85 | −0.71 | 4.89 |

| lnSTD | 420 | 3.20 | 1.55 | −1.97 | 8.02 |

| CC | 420 | −0.77 | 0.41 | −1.5 | 0.25 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Empirical Results of Fixed Model.

Table A3.

Empirical Results of Fixed Model.

| Variables | Base Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Const | −4.1234 *** (0.0011) | −11.996 *** (0.0000) | −8.904 *** (0.0000) | −8.842 *** (0.0000) | −8.804 *** (0.0000) | −8.926 *** (0.0000) |

| Ln PRE | 0.0391 (0.1587) | 0.127 *** (0.009) | 0.127 *** (0.009) | 0.118 ** (0.021) | 0.126 ** (0.01057) | 0.324 *** (0.020) |

| Ln DFA | 0.0391 *** (0.0000) | 0.112 (0.101) | 0.112 (0.101) | 0.113 * (0.098) | 0.1017 (0.30006) | −0.349 ** (0.1469) |

| Ln FDI | 0.5043 *** (0.0000) | 0.489 *** (0.0000) | 0.489 *** (0.0000) | 0.569 *** (0.0000) | 0.590 *** (0.0000) | 0.816 *** (0.000) |

| Ln EMP | - | −0.290 *** (0.0005) | −0.290 *** (0.0005) | −0.29 *** (0.0000) | −0.288 *** (0.0000) | −0.25 *** (0.0000) |

| Ln TED | - | −0.007 *** (0.923) | −0.007 *** (0.923) | −0.005 (0.0000) | −0.006 (0.9929) | 0.0765 (0.3521) |

| Ln GFC | - | −0.061 *** (0.0001) | −0.061 *** (0.0001) | −0.06 *** (0.0026) | −0.062 *** (0.0000) | −0.0525 (0.0001) |

| Ln DCP | - | −1.659 *** (0.0000) | −1.659 *** (0.0000) | −0.66 *** (0.0000) | −0.653 *** (0.0000) | −0.6475 *** (0.0000) |

| Ln STD | - | 0.165 *** (0.0526) | 0.165 *** (0.0526) | −0.165 ** (0.0411) | −0.0167 *** (0.0000) | −0.175 * (0.0887) |

| LnFDI × CC | - | −0.0125 *** (0.008) | 0.3210 *** (0.003) | |||

| Ln PRE × CC | - | 0.013 (0.2269) | 0.0.2737 ** (0.017) | |||

| LnDFA × CC | - | 0.0147 *** (0.0034) | −0.61750 ** (0.0003) | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.398 | 0.536 | 0.545 | 0.536 | 0.538 | 0.58 |

Note: *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%.

References

- Islam, M.S.; Azad, A.K. The Impact of Personal Remittance and RMG Export Income on Income Inequality in Bangladesh: Evidence from an ARDL Approach. Rev. Econ. Political Sci. 2024, 9, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayamba, E.C.; Haibo, C.; Abdul-Rahaman, A.-R.; Serwaa, O.E.; Osei-Agyemang, A. The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Sustainable Development in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 25625–25637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Ullah, M.R.; Zulfiqar, M.; Parveen, S.; Kibria, U. Financial Development, Trade Openness, and Foreign Direct Investment: A Battle between the Measures of Environmental Sustainability. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 851290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B. Does China’s OFDI Successfully Promote Environmental Technology Innovation? Complexity 2021, 2021, 8389560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Nankpan, M.N.; Zhou, B.; Forson, J.A.; Nkrumah, E.N.K.; Adjavon, S.E. A Cop28 Perspective: Does Chinese Investment and Fintech Help to Achieve the SDGs of African Economies? Sustainability 2024, 16, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R. Research on the Environmental Effects of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI): Empirical Evidence Based on the Implementation of the “Belt and Road” Initiative (BRI). Sustainability 2022, 14, 12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeagha, M.C.; Breitenbach, M.C. Revisiting the Nexus between Fiscal Decentralization and CO2 Emissions in South Africa: Fresh Policy Insights. Financ. Innov. 2023, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Q.A.; Waris, U.; Ahmed, S.; Agyekum, E.B.; Hussien, A.G.; Kamal, M.; ur Rehman, M.; Kamel, S. What Is the Role of Remittance and Education for Environmental Pollution? Analyzing in the Presence of Financial Inclusion and Natural Resource Extraction. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musah, M.; Boateng, F.; Kumah, E.A.; Adebayo, T.S. Financial Flows and Environmental Quality in Ecowas Member States: Accounting for Residual Cross-Sectional Dependence and Slope Heterogeneity. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 1195–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.G. Environmental Downfall in Bangladesh: Revealing the Asymmetric Effectiveness of Remittance Inflow in the Presence of Foreign Aid. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Dong, D.; Dong, X. Natural Resources Extraction, Financial Expansion and Remittances: South Asian Economies Perspective of Sustainable Development. Resour. Policy 2023, 84, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, L. Natural Resources, Remittances and Carbon Emissions: A Dutch Disease Perspective with Remittances for South Asia. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Raza, K.; Alharthi, M. The Nexus between Remittances, Education, and Energy Consumption: Evidence from Developing Countries. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 46, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.T.; Nguyen, V.A.; Ly-My, D. Does Aid for Trade Affect the Quality of the Environment? Evidence from Aid for Trade Recipient Countries. J. Int. Dev. 2023, 35, 2465–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enusah, A.; Aboagye-Otchere, F.; Agyenim-Boateng, C. The Effect of Renewable Energy Aid and Governance Quality on Environmental Tax Effort in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 4165–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, R. Does Official Development Assistance Alleviate the Environmental Pressures During the Urbanization of Recipient Countries? Evidence from the Sub-Saharan Africa Countries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ali, S.; Anser, M.K.; Nassani, A.A.; Al-Aiban, K.M.; ur Rahman, S.; Zaman, K. From Desolation to Preservation: Investigating Longitudinal Trends in Forest Coverage and Implications for Future Environmental Strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, M.B.; Pradhan, R.P.; Nair, M.S.; Dabir-Alai, P. Exploring the Temporal Links between Foreign Aid, Institutional Quality, and CO2 Emissions for Poorer Countries. Energy Build. 2022, 270, 112287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Nallapaneni, M.K. Europe Moves toward Pragmatic Sustainability: A More Human and Fraternal Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A. Assessing the Theoretical Scope of Environmental Justice in Contemporary Literature and Developing a Pragmatic Monitoring Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-B. Emission Transfers, Pollution Havens, and Environmental Regulations. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2025, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, R.; Ghosh, C.; Sinha Ray, R. Can Governance Moderate FDI Inflows to Convert the Pollution Haven to a Halo? Revisiting the BRICS Context Using the Panel ARDL Approach. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, F.J.; Ranocchia, C.; Rubio, S.J. Porter Hypothesis Vs. Pollution Haven Hypothesis: Can an Environmental Policy Generate a Win-Win Solution? Energy Econ. 2025, 146, 108477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Kazak, J. Energy Poverty and Environmental Degradation in South Asian Countries with the Role of Poverty, Globalization and Institutional Quality: Static Panel Data Approach. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, P.H.; Marques, A.C.; Shahbaz, M. Does Climate Finance and Foreign Capital Inflows Drive De-Carbonisation in Developing Economies? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amowine, N.; Balezentis, T.; Zhou, Z.; Streimikiene, D. Transitions Towards Green Productivity in Africa: Do Sovereign Debt Vulnerability, Eco-Entrepreneurship, and Institutional Quality Matter? Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 3405–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, T.; Wang, F.; Rauf, F.; Ain, Q.U.; Ali, H. Linking Personal Remittance and Fossil Fuels Energy Consumption to Environmental Degradation: Evidence from All SAARC Countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 8447–8468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]