1. Introduction

Agility in organizations has become a key capability of the companies that have to work in an environment with high dynamism, especially financial institutions that have to face digital transformation and the pressure of regulations and international competition. The Saudi banking industry has been undergoing massive modernization due to Vision 2030, the growth of digital banking facilities, increased customer demands, and increased competition among national and foreign banks in the Gulf region [

1]. These changes have triggered a strategic need by banks to become more flexible internally, faster in making decisions, and more adaptive. The banking sector of Saudi Arabia is one of the most regulated technology-based and internationally integrated sectors, which, unlike most other countries across the region, makes it an appropriate context within which the impact of human-capital practices on the agility of organizations can be studied. Therefore, Saudi Arabia is not only a great and powerful banking system, but it is also a sphere experiencing an extensive structural and digital change, which makes it especially meaningful to the research in comparison to other countries like Jordan, where sectoral changes do not take such an expansive scale and the pressure of digitalization is diversified [

2].

In spite of the fact that the role of agility in modern organizations has been recognized well, the empirical studies on the human resource antecedents of agility that are agility succession planning, talent development, and organizational learning are less prevalent, especially in the Middle-Eastern banking organizations. The available research has focused largely on Western economies or manufacturing environments [

3], and few have undertaken the research on how internal HR systems have a collective contribution to agility in highly regulated service industries [

4]. Additionally, succession planning and talent development have often been studied separately with no attempt to combine and evaluate how organizational learning can strengthen or reduce their impact on agility [

5,

6]. As a result, there exists a significant gap in research, since HR practices do not tend to work alone but instead interact to influence the level of employee preparedness and organizational responsiveness.

Two main issues give rise to the motivation of this study. To begin with, despite the fact that Saudi banks practice organized HR activities, there is little information on whether these activities translate into organizational agility. Second, banking organizations in all parts of the world are facing a skill gap and challenges of pipeline leadership; however, there is a lack of empirical data to explain the role of succession planning and talent development in agility, especially with organizational learning in place. This gap should be bridged by scholars and practitioners who aim to understand how human-capital strategies can be used to facilitate adaptability to actively changing financial contexts.

Based on these observations, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: How does succession planning influence organizational agility in Saudi banking institutions?

RQ2: How does talent development influence organizational agility in Saudi banking institutions?

RQ3: Does organizational learning moderate the relationship between succession planning and organizational agility?

RQ4: Does organizational learning moderate the relationship between talent development and organizational agility?

Answering those questions, the current research contributes to the existing body of knowledge in three key ways: (i) it provides one of the limited number of empirical models, which merge succession planning, talent development, and organizational learning within a single framework; (ii) it extends the understanding of the relationships between HRM and organizational agility in non-Western, highly regulated service industries; and (iii) it provides the empirical evidence based on the very fast-evolving financial market where workforce dynamics are unique.

The key notion discussed in this paper is the connection between human-capital development processes and organizational agility—a notion that is increasingly becoming an absolute requirement of companies operating in open, technology-driven, and highly competitive global markets. The digitalization of the banking industry in the Gulf region and Saudi Arabia in particular have led to an unprecedented organizational change due to the emergence of new financial technologies, regulatory changes, and high customer demands. These forces force the banks to reorganize their work force, accelerate decision-making processes, and also increase their sensitivity to environmental changes. Agility therefore has ceased to be a competitive advantage and it has become a strategic imperative.

It is in this broad context that the paper aims at examining three constructs of human resources that are interrelated: succession planning, talent development, and organizational learning. These constructs were specifically chosen due to the fact that these are the main mechanisms with the help of which organizations maintain a continuity of leadership, establish capabilities of the work force, and share knowledge which is combined together to determine whether the organization will be able to adapt and react well to changes. The previous research on the role of strategic HRM and dynamic capabilities states that agility is not only created through technological investment or structural redesign but also through how ready, developed, and aligned the human capital is towards the organizational objectives.

Succession planning was also chosen as a central construct since the continuity of leadership is a crucial aspect in the banking sector, where any form of disruption in essential positions may impact risk management, adherence, and operational stability. Although the connotation of succession is usually linked with family-based business, the latter-day HRM literature has spread the concept to corporate-based businesses by calling it a strategic process through which people are given a chance to take up key roles. Succession planning, in the context of Saudi banks, which are joint-stock organizations having formalized governance structures, ensures the leadership preparedness and ensures that the organization is least affected by disruptions in the decision-making processes; hence, it leads to organizational agility.

The second construct is talent development, since the banking institutions are increasingly relying on workforce skills including digital literacy, analytical skills, customer experience management, and technical skills. With the adoption of new innovative technologies by the banks, the implementation of AI-based customer service, digital payment infrastructure, and cybersecurity systems, the employees have to be reskilled continuously. This transition is facilitated by talent development processes that help in nurturing employee capabilities, increasing employee engagement, and lowering skills obsolescence, the three factors that are highly associated with agility. Nevertheless, it is not always so simple; some types of talent development can focus on the standardization of procedures and do not pay much attention to adaptive competencies, which makes the construct theoretically well-grounded and deserving of research.

Organizational learning has been included as a possible moderator, since the capacity of learning, unlearning, and relearning is at the core of the creation of dynamic capabilities. The processes of learning influence the way the employees perceive new information, the ability of organizations to revise routines and the flow of knowledge through the department. Organizational learning can also be useful in enhancing the outcome of succession planning and talent development in banking, where the force of regulatory, technological, and customer behavior changes is quickly felt, and only through learning can the employees become productive in their new knowledge application. On the other hand, too strict or formalized learning practices can be counterproductive to flexibility. This two-sidedness of learning makes it a theoretically significant concept for explaining the differences in agility results.

These constructs are not therefore chosen randomly but are based on the HRM theory of strategic HRM, the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, and the Resource-Based View (RBV). They are collectively a coherent conceptual model providing connections between human-capital processes and organizational responsiveness. Moreover, despite their theoretical role, there is a paucity of empirical studies that simultaneously focus on these constructs, especially in the financial sectors of the Middle East. This lack also supports the conceptual orientation of the current research.

The rest of the article is structured in the following way.

Section 2 shows the theoretical background and the previous literature concerning succession planning, talent development, organizational learning, and organizational agility.

Section 3 describes the research design, measurement instruments, sampling procedures, and conceptual model. The data analysis and results of the structural equation model are reported in

Section 4.

Section 5 provides the discussion of the key findings and their implications.

Section 6 ends with contributions, restrictions, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of Succession Planning and Organizational Agility

The literature discussion shows that there is a positive correlation between succession planning and organizational agility. Disregarding arguments of a more philosophical background, and acknowledging the ability of foresight coupled with the ability to engage directly, new leaders have the potential to promote change and hasten the implementation of agility, as outlined by [

7]. Succession planning in the banking sector also considers voids in institutional leadership that are well-established and cause no inconvenience to continuity, as business organizations exist in a tumultuous and uncertain environment, as indicated by [

8]. With the rate of legal and technological revolution in some Saudi banks, succession planning facilitates the alignment of the bank’s strategy with its vision of future market conditions. Authors [

9] advocate the idea that a high degree of flexible adaptability is associated with solid succession planning resulting in agility in a highly dynamic and competitive ecosystem.

The literature that was reviewed has consistently implemented succession planning as a strategic human resource method that ensures continuity in leadership capacity, operational stability, and knowledge within the institution. The role of succession planning becomes yet more important in Saudi banking, where the requirements of regulatory factors, digitalization, and nationalization of the workforce (Saudization) exacerbate the necessity of a leader being prepared to succeed. Succession planning is not just a process of preparing people to be at a higher level of position; it brings about clarity of expectations, less ambiguity in leadership, and the increased responsiveness of an organization. These criteria are the direct benefit of agility, as it allows making decisions more rapidly and making the transition between change periods easier. Therefore, building on theoretical insights and contextual realities, it is assumed that succession planning should have a significant positive relationship with organizational agility, leading to the first hypothesis.

2.2. The Influence of Talent Development and Organizational Agility

There is evidence in the literature confirming a close association between “developing talent” and organizational agility. For example, ref. [

3] suggests that the use of training modules tailored to specific needs, such as digital literacy in conjunction with training in customer relationship management, allows employees to contribute to the organization’s change purposefully. Furthermore, the scientific studies [

4] stated that the talent management systems in Saudi banks contribute to the maintenance of the banks’ market position and reduce the damage of any potential downturn in the local economy. These systems help firms achieve a high degree of cross-functional integration, which is one of the solutions to a firm’s ability to adapt to its surrounding environment. Hence, for a more practically oriented human resource, talent management helps generate organizational flexibility, which is of great importance within the context of the changing financial climate.

Prior studies highlight that talent development enhances employee competencies, strengthens strategic capabilities, and equips the workforce with the skills needed to perform in dynamic environments. In the Saudi financial sector, where digital banking, cybersecurity, AI-based solutions, and customer-centric service models are rapidly evolving, talent development ensures that employees possess up-to-date technical, analytical, and adaptive competencies [

5]. Talent development should theoretically promote agility by increasing the organization’s capacity to innovate, respond to disruptions, and reconfigure processes [

6]. While some literature suggests that developmental programs can become rigid or compliance-oriented, the expected theoretical relationship remains positive in well-structured banking environments. Thus, the evidence supports the assumption that talent development contributes positively to organizational agility, forming the basis for the second hypothesis.

2.3. Organizational Learning Moderates the Relationship Between Succession Planning and Organizational Agility

Prior research has shown that organizational learning can moderate this relationship. Ref. [

7] states that succession planning is one of the most significant contributing factors to agility, because it enables the organization to strategically replace people who are most capable of change and innovation. This is even more the case when the organization also embraces a learning culture. Ref. [

8] argues that the collection and organizational structuring of feedback arising from leadership development, as well as its consequent organizational strategic integration, are crucial. These systems hold the feedback, and the collective belief systems are also the most widespread type of organizational learning, contributing to the development of organizational adaptive capacity. Although [

9] studied Jordanian banks rather than Saudi ones, their results on HRM practices and organizational culture suggest that a strong learning-oriented culture can positively influence HR effectiveness—which may be analogous to how a workplace learning culture could support succession planning and organizational flexibility in other banking contexts. They proposed that embedding a workplace learning culture throughout banking organizations would enable the banks to reap the benefits of succession planning and, in turn, improve the organization’s responsiveness and flexibility to changing technology and the market. The moderation process suggests that the relationship between succession planning and agility is moderated by organizational learning, thereby ensuring that succession planning enables the sustained competitive position of the leadership shift in the continually changing financial landscape over time.

Organizational learning enables employees and teams to acquire, interpret, and apply new knowledge to improve performance and adapt to environmental changes. The literature positions learning as both a capability and a culture that enhances the translation of HR practices into meaningful behavioral outcomes. In Saudi banking organizations—characterized by regulatory complexity, rapid digitalization, and shifting customer expectations—organizational learning becomes essential for reinforcing the effectiveness of succession planning and talent development. When learning mechanisms are strong, employees are more capable of applying developmental experiences and leadership guidance to real operational challenges, thereby enhancing agility. Conversely, weak or overly formalized learning systems may limit the benefits of HR practices. Therefore, it is assumed that organizational learning moderates the effect of HR practices on agility, leading to the third and fourth hypotheses.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Organizational Learning in the Relationship Between Talent Development and Organizational Agility

Organizational Agility

Organizational learning remains a possible moderator of the association between talent development and organizational agility. According to [

10], for arms of the organization whose learning culture is well-developed, integrating talent development for organizational agility is a relatively easy task, as employees register new knowledge and, therefore, make better, more responsive decisions. In addition, as stated by [

11], flexibility within an organization and nurturing talents are increasingly linked, as much of the learning outcome is formed within the organizational context of knowledge sharing and other collaborative learning. Learning organizations, as per [

12]’s study, have a greater ease in responding to unpredictable markets and driving digital transformation. It has also been observed that any investment that would focus on building human resources will definitely bring about strategic balance. This will make the devices have the right currency to fight with the increasingly complex global economy.

According to the findings in the existing literature, organizational agility refers to the ability of a firm to identify changes, develop a timely decision, and restructure resources effectively. Agility is a key to survival and a competitive edge in a Saudi banking business where technological, regulatory, and market forces change fast. There has been empirical research showing that agility is not an independent phenomenon, but it is supported by leadership readiness, workforce competence, and learning-orientated cultures.

Agility is a consequence of strategic HR practices that make the company ready to keep adapting. This comprehension forms the conceptual framework of the current research, that agility is a dependent variable that is predetermined by succession planning, talent development, and organizational learning.

3. Theoretical Foundation and Model Development

The present study is based on the Resource-Based View (RBV) and the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, which are two complementary theoretical frameworks that bring an understanding of the way organizations create and maintain a competitive advantage in the context of dynamic environments. Collectively, the theories offer an effective basis of the proposed model, which bridges the relationship between succession planning, talent development, and organizational learning to organizational agility in the Saudi banking industry.

3.1. Resource-Based View (RBV)

The RBV assumes that the higher an organization’s performance levels, the more valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources it has. Human skills, leadership pipelines, and institutional knowledge make up the human capital and are generally well-known as a strategic resource under RBV [

13]. Organizations develop, retain, and protect such strategic human resources through succession planning, as well as talent development. Organizations can increase the strength of the internal resource base by training high-potential employees, strategically developing workforce resources, and enhancing the response capability to market changes.

RBV embraces the notion that not only succession planning but also talent development has a direct effect on the agility of an organization, since an organization that has prepared human capital is in a better position to respond promptly to challenges, reformulate processes, and make sound decisions in response to the new challenges [

14]. In some of the most controlled and technological industries like banking, the presence of good leaders and talented workers becomes critical in the process of sustaining competitiveness, hence connecting such HR practices to the agility results [

15].

3.2. Dynamic Capabilities Theory

The Resource-Based View is furthered by the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, which focuses on the way organizations combine, reorganize, and redeploy resources in response to the ever-changing environments [

16]. Organizational agility is considered to be one of the key expressions of dynamic capabilities, since it is used to describe how an organization can identify the opportunities, capture them, and adjust internal structures to them [

17].

Organizational learning can be positioned under this concept, since it is a higher-order competency that can empower employees and teams to learn, share, and use knowledge. Learning helps to keep the competencies up to date constantly, facilitates innovation, solves problems faster, and increases adaptability [

18]. As a result, organizational learning can be considered a direct agility enhancer, as well as a moderator that determines the intensity of the correlation between the HR practices and agility.

3.3. How the Model Is Derived from Theory

According to the RBV, the conceptualization of succession planning and talent development lies in the strategy of strategic HR resources capable of developing leadership preparedness, profundity of skill, and the strength of the human capital [

19,

20]. The Dynamic Capabilities Theory also implies that the effectiveness of these resources depends on the ability of an organization to learn and adapt [

16]. As such, succession planning and talent development are suggested to have direct impact on organizational agility, with organizational learning acting as a mediator, strengthening or altering such relationships.

According to the model, organizational learning is stronger; in that case, the employees can more easily apply the experience of development, transfer knowledge across units, and adapt processes more quickly, which enhances the connection between HR practices and agility. On the other hand, developmental practices may fail to translate properly into adaptive capabilities when learning is weak or rigid.

The research results of this paper provide subtle information about the RBV and the Dynamic Capabilities Theory:

3.3.1. Support for Theory

The high positive effect of succession planning on the agility of an organization is in line with the Resource-Based View (RBV), and as such, it validates the fact that leadership preparedness is a valuable resource, enhancing the adaptive ability of an organization [

14]. Similarly, the positive moderating role of organizational learning supports the findings of the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, that postulates learning aids in reconfiguration and mobilization of resources [

17].

3.3.2. Partial Support and Theoretical Tension

The negative impact on talent development of organizational agility establishes a challenge to the traditional RBV beliefs, according to which all developmental human resource practices have inherent advantages of strengthening human capital [

15]. This rather surprising finding suggests that certain forms of developing talent, especially that which is too formalized or one that is compliance-based, might reduce flexibility or encourage the specialization of skills that limit agility. On the same note, the negative moderating effect of organizational learning implies that the processes of learning can at times strengthen the inflexible patterns, instead of enabling adjustment.

The findings underline the fact that, although the RBV and the Dynamic Capabilities Theory can be a helpful conceptual base, the interaction between the HR practices and organizational agility is not always linear and positive. Rather, the effectiveness of HR resources depends on the congruency of practices, organizational environment, and the nature of learning processes.

3.4. Contribution to Theory

There are three key ways in which this study is related to the theoretical literature:

3.4.1. Extending RBV

The results represent the fact that strategic HR practices do not uniformly contribute to agility, unless properly aligned with organizational needs.

3.4.2. Enriching Dynamic Capabilities Theory

The moderating role of organizational learning shows that learning capabilities can either strengthen or weaken agility-related outcomes, offering a more differentiated view of learning as a dynamic capability.

3.4.3. Contextualizing Theory in the Saudi Banking Sector

The findings introduce empirical evidence from a highly regulated, fast-evolving, non-Western financial sector—an underrepresented context in the current HRM and dynamic capability literature.

This research describes succession planning and talent development as a strategic resource that can increase organizational agility and organizational learning as a moderator [

13,

21]. With these organizational capacities, banking and financial services sector firms can develop the agility that is needed to cope with the evolving conditions of their environment.

This study describes the theoretical constructs that direct the inter-relationships of these variables. Consequently, there is a positive relationship between succession planning and organizational agility, whereby organizational effectiveness is the ability to adapt to changing market conditions, advances in technology, and regulatory requirements [

22]. Organizational learning is the totality of all the practices that are learning and knowledge-oriented. These practices include succession planning and knowledge retention systems, team training and feedback, which are systems that are designed to enhance the external assimilation framework [

23]. Hence, for the banking and financial services sector in Saudi Arabia, where the main forces for change are the market conditions and technology, this framework is effective in showing the relation between the organizational adaptability and integrated talent management and learning.

This study constructs such a framework and utilizes the RBV theory to examine how succession planning, talent development and organizational learning are resources in achieving agility in a given turbulent and dynamic industry. This framework emphasizes the importance of matching talent management and learning organizations to develop resilience and agility that can benefit from constructive research and practice. The theoretical relationships are illustrated in

Figure 1.

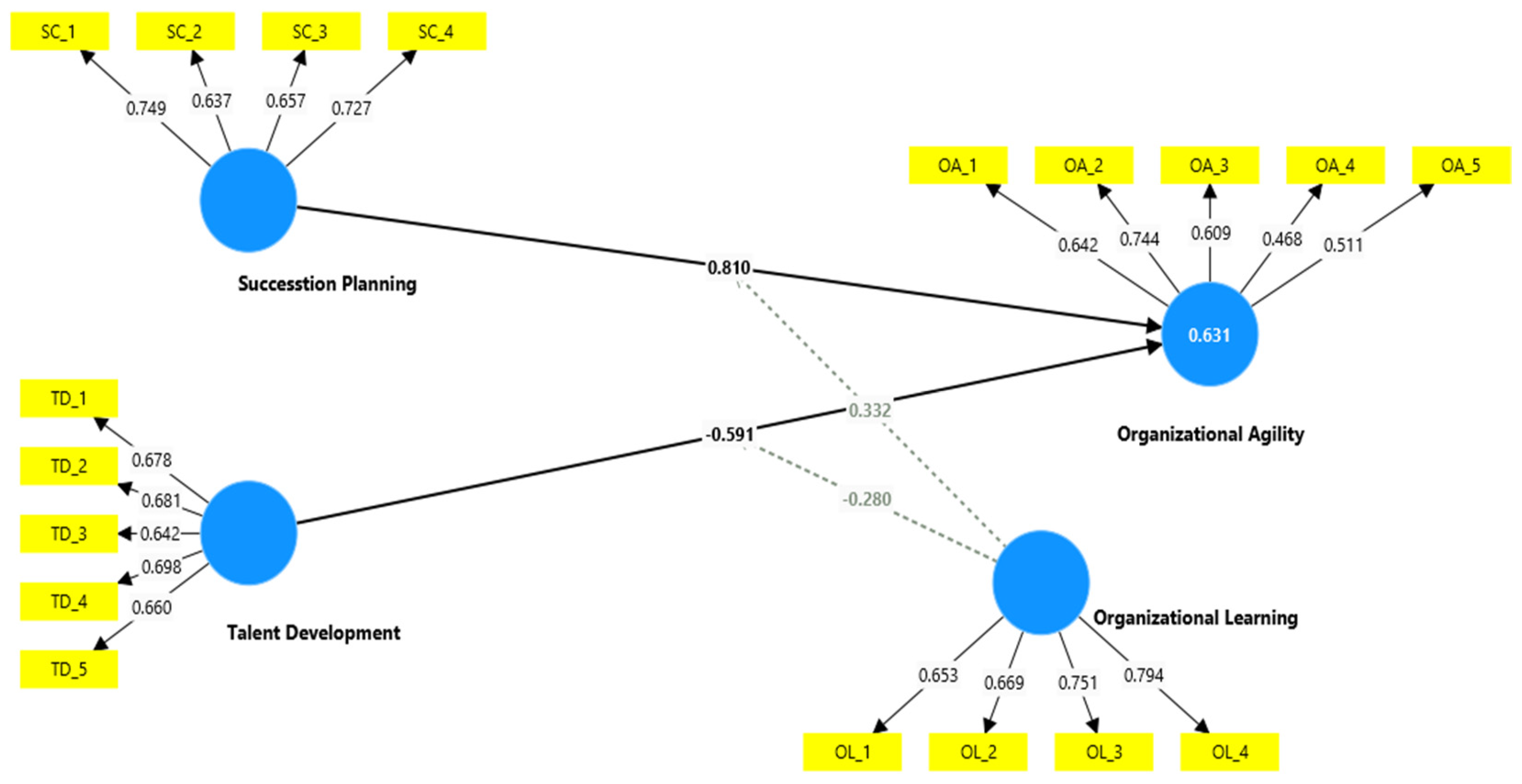

Figure 2 presents the structural model used to guide the empirical analysis. Succession planning and talent development are modeled as exogenous variables, organizational agility as the endogenous variable, and organizational learning as a moderator influencing both relationships.

Based on the theoretical background and the prior empirical literature, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1. Succession planning has a positive and significant effect on organizational agility.

H2. Talent development has a positive and significant effect on organizational agility.

H3. Organizational learning positively moderates the relationship between succession planning and organizational agility.

H4. Organizational learning moderates the relationship between talent development and organizational agility.

These hypotheses collectively represent the structural relationships tested in this study and establish a clear foundation for the subsequent PLS-SEM analysis.

4. Research Methodology

The current research was conducted among the employees of Saudi banking and financial services organizations, which formed the study’s population. It was estimated that the total population of this sector was about 3500 workers. A sample size table of 400 respondents was considered sufficient to obtain a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error.

The Simple Random Sampling technique is recommended to enhance the chance of the research subjects being oblivious, because all population members have equal chances to be selected, which [

24] supports. This was where the population strata were specific or where the population was made of subpopulations with different proportions and sizes, for which stratified sampling was used [

25]. In addition, it is possible to minimize the costs of making responses by employing cluster sampling for the scattered respondents in geographical locations and institutions [

19]. To achieve the right balance, proportional representation was ensured to complement all other institutions that were obviously out of balance, especially when exploiting larger institutions’ templates.

Although gaining fully unrestricted random access to employees in Saudi Arabian banks can be challenging due to regulatory and organizational approval processes, the present study applied a practical form of stratified random sampling within the constraints of the banking environment. The researcher first obtained permission from selected banks and HR departments that agreed to support the study. Each participating bank provided access to employees across different departments and hierarchical levels. Within these strata, questionnaires were distributed randomly to employees who were available during the data collection window.

This approach does not represent pure probability sampling in a statistical sense, but it reflects a controlled randomization process within accessible clusters, which has been widely used in organizational studies where full population lists cannot be obtained. The justification for maintaining the term “random sampling” is that the selection of employees within each participating bank was not based on convenience or personal networks, but on random distribution within predefined strata such as department, role, and branch.

According to scholars who have used this method to conduct studies in service areas of the Middle East, it is a hybrid method that is considered suitable when organizations have control over the access of employees and the researcher has no option but to use internal gatekeepers [

8,

11]. As a result, although attending to the practical limitations of the Saudi banking setting, the process of the sampling has sufficient randomness to help reduce the selection bias and increase the representativeness of the end sample.

This study relied on a structured employee survey as the source of data that was carried out in various Saudi banking and financial institutions. The collection of data entailed both online distribution and controlled physical circulation to make certain the data is accessible to more employees who have different job descriptions and timetables. The research was conducted voluntarily and anonymously, and the respondents were assured that their answers would be utilized only for academic research.

Four hundred and fifty questionnaires were given to participants and four hundred and twenty-three were replied to. Following the screening of incomplete responses, patterned responses, and missing demographical data, 400 valid responses carried on to analysis. The sample size is satisfactory, since it is sufficient and beyond the minimum acceptable quantifiable amount in PLS-SEM procedures; thus, it has sufficient statistical power.

The survey involved the employees of various levels of hierarchy, including entry-level workers, supervisors, managers, and heads of different departments, in order to obtain a variety of different views on the topic of succession planning, talent development programs, and organizational learning activities. Age, gender, educational level, occupation, and work experience were used as demographic variables to describe the sample and determine the possibility of bias in the responses.

The lack of data was solved with the help of a two-step procedure. To begin with, the questionnaires with more than 20% missing answers were not included. Second, where the cases had low levels of missing values (less than 5 percent of cases per construct), mean substitution was used, which is recommended to use Likert-scale data in organizational studies. This approach did not destroy any of the data sets in terms of integrity, variance, or internal consistency. Structural variables did not require any imputation because all the cases retained provided entire responses.

In order to address the common method bias, which is a very relevant issue in employee surveys, a number of procedural controls were put in place, such as assurance of anonymity, randomization of the order in which the items were presented, alternation of an affirmative and negatively presented statement, and separation of dependent and independent variables through the questionnaire structure. These controls bring down the social desirability and consistency biases, hence improving the reliability of the employee-reported data.

This, in turn, makes this data a strong and structurally obtained sample of employees in the banking sector in Saudi Arabia, and it includes the organizational practices and perceptions necessary for the empirical analysis of the conceptual model.

The research design is an exploratory, deductive, and quantitative research design. The exploratory element indicates the lack of empirical research to connect the factors of succession planning, talent development, organizational learning, and organizational agility to the Saudi banking industry and the research attempts to spot the trends and clarify the relationships that lack empirical studies. The deductive aspect is based on the derivation of the conceptual framework and hypotheses based on the pre-existing theories, i.e., the Resource-Based View and the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, and then testing them in an empirical study using survey data. The quantitative aspect is expressed by the measures of constructs using numerical values of constructs by the use of the items of the structured questionnaires, and the use of PLS-SEM to provide a statistical analysis of the proposed relations.

4.1. Operational Definitions

To ensure that the concept is clear and there is a conceptual fit between theory and measurement, the following operational definitions define the understanding and measurement of each construct in this study.

4.1.1. Succession Planning (SP)

Succession planning is the process of identification, training, and equipping employees to fill important leadership and critical positions within an organization in the future in a formal and systematic manner. Operationally, in the present research, succession planning is considered to be the level of how the banks maintain transparent promotion channels, how they recognize a potential successor well in advance, how they cultivate the high-potential employees, and how they revise leadership continuity plans. It includes preparedness, organized talent-pipes, and transparency of promotional procedures [

14].

4.1.2. Talent Development (TD)

Talent development refers to the deliberate and continuous organizational practices aimed at supplementing employees’ knowledge, skills, and competencies, as well as their career development. Practically, this inquiry stipulates talent development as the provision of organized training courses and learning chances, upskilling interventions, and competency-development engagements that support the professional progress and performance of employees [

13].

4.1.3. Organizational Learning (OL)

Organizational learning refers to the overall organizational ability to gain, distribute, decipher, and utilize knowledge to improve processes, practices, and products. Operationally, this construct focuses on the existence of learning cultures, knowledge-sharing systems, team-based learning practices, reflective activities, and mechanisms which promote continuous improvement. Organizational learning is also a moderating capability in this study that can determine the impact of HR practices on agility [

11].

4.1.4. Organizational Agility (OA)

Organizational agility is the capability of the organization to detect changes, react swiftly to the situation, proactively adapt, and redirect resources in response to changing environmental demand. As an indicator of OA, in this study, operationality is quantified using indicators that describe responsiveness, decision-making speed, process flexibility, technological/market changes adaptability, and ability to reallocate resources quickly [

10,

15].

4.2. Measurement of Study

Multi-item Likert scales based on the previous, well-tested scales were used to measure all constructs used in this study. All items have been rated on a five-point Likert scale with the possible options of 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree. The questions were pre-tested by reviewing the measures by academic experts and the HR professionals in the Saudi banking industry to provide contextual clarity and content validity. A pilot was performed on 30 respondents to ensure that the items were readable and appropriate. There have been slight changes in wording made depending on their feedback, but nothing has been included or omitted without theoretical reasons. The description of the constructs and their measures indicators is given below.

The complete research questionnaire and measurement items used for all constructs are provided in

Appendix A.

4.2.1. Succession Planning (SP)

The measure of succession planning was determined through the use of items modified, based on the body of research on human resource management and the leadership pipeline, such as the works of Rothwell and Garman. These are products that measure the degree to which an organization is systematic in identifying, preparing, and training employees in key leadership and technical roles. The signs include a structured succession program, the availability of the promotion channels, the willingness of the future successors, and a formalization of the continuity plans of leadership [

14,

16,

22].

4.2.2. Talent Development (TD)

The evaluation of the talent development was performed on the basis of items based on the frameworks that were relevant to human capital development and competency development. The indicators represent the degree to which the organization offers structured learning opportunities, upskilling, career development, professional training, and continuous improvement support. These items gauge the organizational commitment to increase the knowledge, skills, and career preparedness of the employees in the fast-changing banking environment [

13].

4.2.3. Organizational Learning (OL)

Organizational learning was measured using the items based on the existing models of learning organizations. The indicators are reflective of a continuous learning culture, learning in teams, open communication, shared knowledge practices, and institutionalizing the learning processes. These items measure the effectiveness of how the organization purchases, shares, and uses knowledge in improving individual and team performance [

11].

4.2.4. Organizational Agility (OA)

The indicators of organizational agility were based on the dynamic capabilities and agility literature modified to measure organizational agility. They represent the capability of the organization to react fast to any alteration, reallocate resources, take a quick decision, be innovative, and adjust the operational processes when necessary. The indicators focus on speed, flexibility, adaptability, and proactive responsiveness—skills that are especially valuable in the volatile banking market in the Saudi context [

17,

18].

4.2.5. Reliability and Validity

All constructs were measured for internal consistency using Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability, with all values exceeding 0.70, which is the recommended threshold. Factor loadings and Average Variance Extracted (AVE ≥ 0.50) was implemented for convergent validity. Discriminant validity was examined using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, HTMT ratio, and cross-loadings. These steps ensure that the measures accurately represent the theoretical constructs and are statistically robust for structural equation modeling.

5. Data Analysis

In this section, the survey data used Smart PLS (partial least squares structural equation modeling). This is because the models in this case are intricate, and evaluating models of this type under non-normal conditions is somewhat tricky. The cleaning of the data was the first step in the analysis process. This is the point at which the missing data items associated with outliers and other anomalies are identified, and any data deemed unclean is excluded from the analysis. Central tendencies and variability were also calculated and summarized in order to give a quick overview of the data.

Also, the reliability of the constructs was measured within the scope of Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR). As stated by [

20], CR values should be above 0.7. This study also computes Average Variance Extracted and total values of greater than 0.4, which is deemed acceptable for convergent validity. The factor loadings of these indicators were also determined and checked regarding performance. Cut-off points of 0.7 and above were considered satisfactory. Nevertheless, a visual appraisal or item omission dealt with any factor loading below the 0.7 cut-off to enhance construct validity. The factor loadings showed the significance level of each item based on its construct, and the results of the loadings were also documented in the analysis. Therefore, the mediation analysis was conducted after the measurement model assessment to conduct structural equation modeling (SEM) with the direct relationship between organizational learning, succession planning, and talent development on organizational agility in the Saudi banking and financial services sector context.

Given that the results should be reliable and robust, the data was resampled using the bootstrapping procedure available in SMART PLS. Compared to the previous techniques, this one provides better and more precise estimates of parameters [

26]. The SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) measured the model’s goodness of fit, where an SRMR of less than 0.08 is recommended [

27]. Furthermore, the path coefficients and factor loadings that explain the connection/relationship of the variables were analyzed, and the role of organizational learning in modulating the linkage between succession planning and talent development to organizational agility in the Saudi banking and financial services sector was analyzed.

6. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

Each construct in this study was operationalized using established theoretical foundations and previously validated measurement scales. The indicators were adapted to fit the banking and financial context of Saudi Arabia while maintaining conceptual clarity and measurement reliability.

6.1. Succession Planning (SP)

Succession planning indicators were based on the developed human resource development literature, especially on leadership pipeline preparedness models, strategic workforce continuity, and the identification of employees with high potential. In past research, the conceptualization of succession planning is the systematic process that guarantees the availability of qualified persons to fill the major positions [

27]. It is on these theoretical bases that items were developed in order to reflect formal planning practices, structured talent pipelines, and the open identification of successors. Changes were only made in accordance with organizational terminology that is prevalent in the Saudi banking industry.

6.2. Talent Development (TD)

Indicators of talent development were based on the human capital theory as well as competency-based development frameworks, which consider the employee skills, knowledge, and capabilities as strategic resources. The classical literature [

19] characterizes talent development as ongoing learning activities, professional growth patterns, and skill enhancement opportunities. In this regard, the indicators used in the present study measure structured training, career growth support, and development opportunities that help to improve the performance of the employees. The items were modified with those which were tested, but were re-phrased to suit current talent management programs within the banking industry.

6.3. Organizational Learning (OL)

The indicators of organizational learning were evaluated based on the adapted version of well-established models, including those cited in source [

24], which point out unceasing learning, open sharing of information, and institutionalizing the knowledge. The chosen indicators demonstrate the existence of a learning culture, sharing knowledge in a team, and the processes by which organizations can acquire, transfer, and use knowledge. These items have been selected based on the fact that they focus on individual and organizational learning processes which are the focus of moderation effects in human resource research.

6.4. Organizational Agility (OA)

The process of the operationalization of organizational agility was based on the theoretical definitions based on the theory of dynamic capabilities and the recent literature on agility that the concept of agility is the ability of an organization to recognize opportunities, react quickly, and restructure resources whenever it is needed [

26]. The indicators were based on the available validated scales that are used in strategic management and organizational behavior studies [

28]. Products are responsive, flexible, rapid-deciding, and adaptive-changing items, all of which are highly relevant to the banking industry and its competitiveness.

All indicators were sourced from prior peer-reviewed studies and adapted using a structured translation and contextualization process. A panel of three HR experts and two industry practitioners reviewed the adapted items for clarity, cultural relevance, and construct representation. A pilot test with 30 employees further ensured readability and face validity. Minor linguistic adjustments were made, but no indicators were added or removed without theoretical justification, ensuring that the operationalization remains consistent with established construct definitions.

The constructs were subjected to content and construct validity assessment, factor loading, and reliability analysis, which included Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability.

The demographic details of the respondents of this study are captured in

Table 1 regarding the participants’ gender, age, educational status, field of study, and work experience. This information is essential, as it gives the characteristics of the respondent’s sample to increase the demographic data of the sample size.

The demographic data given in

Table 1 shows that the sample is really diversified and more or less evenly distributed. The participants are divided almost equally by gender, age is quite diverse, and participants have diverse education levels, work experience, and occupations, which allows us to make conclusions applicable to multiple settings. Such diversity provides a basis for increasing the applicability of the study and a promising foundation for a meaningful analysis and interpretation of the results of the research.

In the measurement model evaluation of this study, the data was checked by comparing each item to the existing empirical model to determine the model’s fitness. Cronbach’s Alpha (α) coefficients were used in the analysis of internal consistency reliability, accepting an alpha of 0.70 and above as having adequate construct validity. All the constructed scales had a Cronbach’s Alpha of more than 0.70, indicating reliability. When testing for convergent validity, we examined all the factor loadings of the indicators except the AVE. The appropriate AVE benchmark is 0.50, and as the value of each construct explains more than half of the variation in its measures, coefficients higher than 0.7 are desirable [

29]. The AVE of each construct was found to be between 0.80 and 0.82; hence, the convergent validity was confirmed by comparing the values with the threshold of 0.50. From

Table 2, AVE values show that organizational learning is influenced by succession planning and talent development on organizational agility in the Saudi banking and financial services sector, which are stereotypically classified in the literature as having contributed towards enhancing the measurement model of the constructs. Therefore, there is evidence of convergent validity among these constructs.

6.5. Structural Model

The last table again shows the HTMT values, indicating the overall confirmatory criterion for discriminant validity, especially for SEM analysis. In essence, discriminant validity evaluates the extent to which measures of different constructs differ [

30]. To do this, HTMT provides a more accurate measure than the existing methods, such as the Fornell–Larcker criterion and cross-loadings, which require threshold values of 0.85 for strict assessment and 0.90 for liberal assessment. All constructs are above the HTMT recommended values of 0.90, which suggests that the models have satisfactory discriminant validity [

31]. For example, the HTMT value between organizational agility and organizational learning is 0.840, which is slightly below the strict threshold and, for that reason, should be of interest; on the other hand, the relationship between talent development and organizational learning has a low HTMT value of 0.220, which confirms their discriminant validity. But some pairings are even beyond the more stringent threshold. Specifically, the correlation coefficient between succession planning and organizational agility is 0.897, which is above the threshold of 0.85 and closely approaching the relatively liberal threshold of 0.90, which indicates potential conceptual redundancy that may threaten construct distinctiveness. The same can be noticed for succession planning and talent development, where the HTMT value was 0.379, slightly higher than the expected correlation coefficient. The interaction terms organizational learning × succession planning and organizational learning × talent development have relatively low HTMT values of 0.167 and 0.132, respectively, which support their discriminant validity and the overall model. In contrast, the interaction term organizational learning × talent development has an HTMT value of 0.655, supporting its discriminant validity. Although the study maintains an average HTMT value below the threshold of 0.90, two constructs, succession planning, and organizational agility, show a high HTMT value of 0.897, which suggests that there may be a measure of construct redundancy between them.

Table 3 presents the HTMT values supporting discriminant validity.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion is a valid procedure for establishing discriminant validity in structural equation modeling. It increases the focused content of a construct in that it explains more of the variance by the construct’s indicators than by other indicators. This method compares the Average Variance Extracted scores presented along the diagonal with the inter-construct correlations presented off the diagonal. Based on [

32], discriminant validity exists if a construct’s AVE value is greater than that construct’s correlation with any other construct.

Table 4 presents the AVE square roots for each construct along the diagonal: organizational agility scored 0.803, organizational learning scored 0.719, succession planning scored 0.734, and talent development scored 0.672. The Fornell–Larcker criterion was employed in the discriminant validity assessment when the square root of the AVE of a construct is higher than all the correlations between this construct and other constructs [

32]. The examination of the table shows that discriminant validity has both positive and negative results.

Organizational agility shows satisfactory discriminant validity, since all its AVE (0.803) is higher than the square of the correlation between organizational agility and the other constructs, organizational learning (0.727) and succession planning (0.698). This implies that organizational agility is measurably unique and is not overly synonymous with different concepts. Consequently, organizational learning meets the Fornell–Larcker criterion, since the AVE exceeds the correlations with talent development (0.652) and succession planning (0.734). This evidence further corroborates organizational learning as a separate and unique construct.

A major issue comes when trying to explore the correlation between succession planning and talent development. The correlation between these two constructs is 0.936, which is greater than the squared AVEs for both succession planning (0.734) and talent development (0.672). This violates the Fornell–Larcker criterion, indicating a high degree of multicollinearity between these constructs, which is inappropriate for establishing discriminant validity. Moreover, the coefficient of succession planning and organizational learning (0.734) is equal to the succession planning AVE, which suggests a degree of overlap which, although not severe, is still worth addressing.

According to [

29], the connection between succession planning and talent development may be due to construct ambiguity, a standard measurement foundation, or conceptual redundancy. This results in difficulty when defining measurement models, as the constructs may be interrelated and lack theoretical uniqueness. Therefore, it is recommended that scholars employ various methods to establish validity. One such method, the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT), is more sensitive to discriminant validity problems than the Fornell–Larcker criterion. It provides much greater separation of competing constructs. Further evidence regarding the validity of the bootstrapping technique is when correlation constructs are created and confidence intervals are computed. If the upper bounds of the intervals exceed the arbitrary thresholds of 0.85 or 0.90, evidence of discriminant validity would be available [

29].

Therefore,

Table 4 shows that constructs such as organizational agility and organizational learning fulfill the Fornell–Larcker criterion. However, the high R-square value for succession planning and talent development presents a major discriminant validity problem. It may be necessary to fine-tune these constructs, change their measures, or use a more credible measure such as HTMT. The following steps will be taken to ensure that the constructs are kept distinct at the conceptual and operational levels, thus improving the credibility of the research.

Table 5 presents the R-square (R

2) and adjusted R-square values for the organizational agility model, reflecting the explanatory power of the model.

According to

Table 5, the model accounted for about 63.1% of the variance in organizational agility, with an R-square of 0.631. This justifies the fact that the independent variables can explain the variations well in the dependent variable, as indicated above. The adjusted R-square value is also used and is slightly lower at 0.625; it incorporates the number of predictors and also looks at the complexity of the model and gives a better and less prejudiced estimation of the variance that the model explains. The R

2 and the adjusted R

2 values are very close (the difference is only 0.006), meaning that all predictors included in the model are both significant and valuable; they enrich the model without overdetermining it.

The findings support the hypothesis that the model is reasonably well-specified and viable for describing the relationships between organizational agility and its antecedents. A minimal decline in the adjusted R2 shows that including other predictor variables has not weakened the fit. This supports the assertion that the predictors are well-captured and consistent with the theoretical framework for the model proposed.

This high R2 indicates that the independent variables applied in the model are useful in explaining most organizational agility. However, further analyses, such as t-tests for comparing individual predictors’ regression coefficients and fit indices, such as RMSEA and SRMR, can also be employed to assess the model fit.

In sum,

Table 4 shows that the model can explain organizational agility based on the high R

2 and adjusted R

2 values. The small gap between these values also supports the model’s validity, reliability, and usability in practice, proving that the model represents the connections between the variables and can be applied to academic and practical settings.

7. Hypotheses Testing

The importance of the path hypotheses was determined by the importance of path coefficients (similar to the “beta weights” in standard metric regression analysis). Coefficients show how, and how much, one variable is related to another variable. These values are limited to between −1 and +1 only. A zero coefficient represents no correlation, and coefficients close to −1 and 1 represent strong negative and positive correlation, respectively. When considering the statistical significance of these path coefficients, the coefficient, standard error, T value, and

p value were carefully considered. Based on this research, there is a significant relationship between the variables in question at a 95% confidence level, that is, if the

p value < 0.05. This affirms the theoretical relationship posited in this study at a 0.05 significance level. This construction allows for the testing of the proposed hypotheses by estimating the weights of the loadings and examining the size of the relationships within the core of the structural model. The findings of this research are graphically depicted in

Figure 2.

The structural model reveals significant findings about the interconnection of succession planning, talent development, organizational learning, and organizational agility in the JSFCs. For H1, the path coefficient of 0.810 shows a significant positive link between succession planning and organizational agility. This indicates that proper succession planning means that organizations have prepared leaders ready to sail through challenging times and manage uncertainties critical to the volatile environment of a dynamic industry that involves technology and markets. H1 is well-grounded, as it underlines that proper succession planning is essential to increase organizational agility.

However, as shown in

Figure 2, H2 talent development has a negative relationship with organizational agility, with a path coefficient of −0.591. This finding may suggest that the existing models of talent development may be too rigid or simply not in line with the goals of the creative economy. Due to these, it becomes difficult to be sensitive to markets, thus underlining the importance of having more fluid and unique talent management approaches.

For H3, organizational learning can positively moderate the relationship between succession planning and organizational agility. This paper has established that organizations’ efforts to create a learning culture increase the effectiveness of succession planning by providing leaders with elasticity and knowledge sharing, which is crucial in Saudi financial industry. H3 is therefore substantiated, hence underlining the need to link learning with succession planning. Last, H4 talent development and organizational learning have a negative moderation effect (−0.280) on talent development, organizational learning, and organizational agility in the Saudi banking and financial services. For H1, the path coefficient of 0.810 demonstrates a positive relationship between succession planning and organizational agility. This means that, if succession planning is conducted well, organizations have leaders who can cope with change and handle the unexpected. This is important, especially for organizational agility in a highly technological and market turbulence sector. H1 is therefore well-supported, as it shows that sound succession planning increases organizational flexibility.

Conversely, the linkage between H2 talent development and organizational agility is negative, with a path coefficient of (−) 0.591. This means that the current talent development policies are not well-suited to the fluid nature of the sector. Due to this, standardized programs may limit the organization’s quick response, which requires more fluid and practical talent management approaches.

Organizational learning has a positive moderation effect on the relationship between succession planning and organizational agility for H3. With the help of the learning culture, the implementation of succession planning improves, the leaders acquire specific skills functional in adaptation, and the knowledge is shared within the organization, which is very important in the context of the financial services of Saudi Arabia. Therefore, H3 has been supported, meaning learning should be integrated with succession planning. Finally, H4 talent development and organizational learning also have a negative moderation effect (−0.280).pt on changes and managing uncertainties. This is important for agility in a fast and ever-changing industry due to technological and market changes. H1 is thus well-substantiated, underlining the importance of a clear succession planning process to organizational agility.

On the other hand, as presented by the path coefficient of −0.591, H2 talent development is inversely related to organizational agility. This implies that the current talent development system might be relatively structured, or that the process may not be effective to accommodate the dynamics of the media industry. Convenience-based strategies might not allow organizations to be nimble and swift, hence demanding more sustainable talent management strategies.

For H3, organizational learning positively moderates the relationship between succession planning and organizational agility. The author’s view is that enhancing the learning culture in organizations enhances the effectiveness of the succession planning process by giving leaders contextual knowledge and knowledge transfer, which is relevant for the financial services industry in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, H3 has been supported, implying learning should be associated with succession management.

Last but not least, H4 talent development and organizational learning reveal a negative moderated effect (−0.280). This is an inefficiency that points towards the fact that the organization’s existing strategies might need a closer look so that talent development is in sync with the learning and agility strategies of the organization. This gap should be filled in an effort to assist organizations to have a more integrated and sustainable workforce.

Organizational agility in the model has an R

2 value of 0.631. This indicates that 63.1% of the variance in organizational agility is explained by the predictors included in the model: succession management, talent management, and organizational development.

Table 6 provides robust evidence for the structural relationships among the variables, including path coefficients, significance levels, and t-statistics.

Table 6 presents the relationships and moderating effects of the variables that affect organizational agility in the Saudi banking and financial services sector. It is revealed that succession planning has a strong positive relationship to the dependent variables, with organizational agility being the highest of all, with a regression coefficient of β = 0.810 and

p = 0.000, thus supporting the practice’s role in providing organizational leadership in dynamic environments. This means that better succession planning strategies must be developed if the organization is to improve its ability to respond to change.

Organizational learning also has a very high positive impact on organizational agility (β = 0.600, p = 0.001). This shows that culture change that embraces learning is key to forming adaptive organizations that can easily change and innovate.

Nevertheless, as predicted, talent development negatively relates to organizational agility (β = −0.591, p = 0.001). This implies that some talent development practices may be undesirable for organizational flexibility, possibly because they are prescriptive or the strategy is not well-coordinated.

The moderating effects help to explain more of the results. The results also demonstrate that organizational learning has positive moderation effect on the relationship between succession planning and organizational agility (beta = 0.332,

p = 0.002), to strengthen the effect of leadership development planning by providing adequate knowledge and skills to leaders in the organization. On the other hand, organizational learning is a negative moderator of the talent development and organizational agility relationship (beta = −0.280,

p = 0.006), meaning that talent strategies may not be optimally integrated with learning initiatives, and this may reduce the impact of the two practices on organizational agility (see the

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

In general, the results suggest that the development of strategic leadership and the creation of a learning climate are critical to organizational flexibility. Nonetheless, the disadvantages of talent development as well as organizational learning require reconsideration and re-architecting talent development according to agility objectives. These findings have theoretical and practical implications for developing organizational agility by focusing on leadership planning, learning, and talent management alignment.

8. Discussion

This paper investigates the relationship between succession planning, talent development, and organizational agility among Saudi banking and financial services organizations using organizational learning as a moderator. The results have important implications for managers on how human resource practices and learning processes can be successfully implemented to facilitate organizational adaptability as a competitive advantage in turbulent settings.

8.1. Succession Planning and Organizational Agility

The hypothesis also supports the results, as there is a positive correlation between succession planning and organizational agility (p = 0.000) (whereas beta = 0.810). This means that, although succession planning is a powerful way of maintaining organizational leadership, it is also a way for organizations to be prepared to cope with environmental changes. This is in sync with the fact that succession planning helps in creating flexibility, because the organization will develop a pool of leaders who are able to handle uncertainties. This paper aims to analyze how succession planning helps to meet the challenges of technological change and regulatory pressures in the Saudi banking industry. Leaders who are selected from systematic succession planning are in a vantage position to make decisions that improve the effectiveness of the organization in terms of flexibility and sustainability. This is the reason why the present study highlights the need to consider specific HR strategies that are related to leadership preparedness to maintain competitiveness in a time of financial turmoil.

8.2. Talent Development and Organizational Agility

Surprisingly, talent development was a strong and negative predictor of organizational agility (β = −0.591,

p = 0.001), which confirmed Hypothesis 2. This means that the current talent management processes within the Saudi banking organizations are not consonant with the agility objectives of the organizations. This would reduce the flexibility of employees in responding to changes, because the training would be too structured towards following specific procedures or rules and regulations. This finding poses a question to current talent development practices recommending new training models that foster problem-solving, creativity, and collaboration. Due to the increased dynamism of the financial services environment, organizations should move towards more fluid and adaptable forms of talent management [

33,

34].

8.3. The Moderating Role of Organizational Learning

Organizational learning was also found to have a positive interaction with succession planning on organizational agility, which is postulated in Hypothesis 3 (β = 0.332, p = 0.002). This result highlights the role of learning cultures in enhancing the power of succession planning. A positive learning culture assists organizations in internalizing the knowledge and skills that are enhanced through succession planning and to apply them to organizational strategic objectives. For example, leadership readiness can help shift shared knowledge systems, feedback loops, and training opportunities into practical agility. This is especially true in the context of the Saudi banking industry, as there is ongoing technological transformation and change in customer needs, hence the need for innovation from the leaders.

On the other hand, the moderating effect of organizational learning on talent development and organizational agility was negative (beta = −0.280, p = 0.006), implying that there is a misfit between talent development and organizational learning strategies. This finding may imply that the learning approaches that are currently in place might not always extend to the intended outcomes of talent management interventions and, therefore, might create a gap between training undertakings and organizational adaptability. In this case, organizations are in need of redesigning the relationship between learning interventions and talent management in order to overcome these inefficiencies. For example, the use of plugging in real-time feedback and collaborative learning tools in talent development interventions can ensure that they are more impactful and align with the agility agenda.

9. Practical Implications

The empirical results indicate that structured succession planning is a reliable enabler of organizational agility, while current talent development approaches in many banks appear to be misaligned with agility goals. Organizational learning can amplify positive effects where aligned, but may also entrench rigidity when misapplied. The following recommendations translate these findings into actionable policy—and practice-level steps intended to improve agility across Saudi banks.

9.1. Priority 1—Reorient Talent Development toward Adaptive Competencies

Problem: Traditional, compliance-centric training produces procedural skills but not the adaptive, cross-functional capabilities needed for agility.

The actions that can be taken are as follows: Redesign curricula to prioritize adaptive competencies: problem-solving, digital literacy, customer-centric design, agile project methods, cross-functional collaboration, and decision-making under uncertainty; Shift from long, classroom-based modules to modular, short-format learning (bootcamps, micro-credentials, e-learning micro-modules) that are job-embedded and immediately applicable; Introduce experiential learning: stretch assignments, job rotations, hackathons, live projects with cross-functional teams, and secondments to digital or innovation units; Replace “one-size-fits-all” mandatory courses with individual learning plans based on competency gap analyses; Responsible: bank HR + learning and development (L&D) teams; Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development (for sector guidance); training providers and universities (for micro-credentials); KPIs: % of learning hours on adaptive skills; internal mobility rate; % employees with micro-credentials; time-to-proficiency for new digital skills. The timeline to redesign pilots is between 3 and 6 months and scale is between 6 and 18 months.

9.2. Priority 2—Strengthen and Institutionalize Professional Succession Planning

Problem: When succession is informal or unclear, agility and continuity suffer.

The suggested actions are as follows: Implement a competency-based succession framework: define role profiles, readiness levels (ready-now, ready-in-1yr, ready-in-3yr), and required adaptive competencies; Maintain a dynamic talent-pool dashboard (centralized, HR-driven) with readiness scores, development plans, and rotation history—integrated with HRIS; Require succession “readiness audits” annually for all critical roles, with board-level oversight for top-tier positions; Formalize emergency succession protocols for critical operational roles to reduce response time during shocks; Responsible: bank HR + executive committees; board remuneration and nomination committees (oversight); Central Bank of Saudi Arabia (SAMA)—recommend as best practice guidance rather than heavy-handed regulation.

KPIs: leadership readiness index; % critical roles with at least two ready successors; mean time to fill leadership vacancy; post-transition performance.

Timeline: competency framework (1–3 months); dashboard and audits (3–9 months); embed in governance (6–12 months).

9.3. Priority 3—Make Organizational Learning Exploratory and Iteration-Focused

Problem: Learning systems that emphasize documentation and compliance can entrench routines rather than promote adaptation.

Actions that are practical are as follows: Rebalance L&D investment to support exploratory learning (pilot-and-learn, small-scale experiments) alongside exploitative learning (process improvement); Create communities of practice (CoPs) and cross-functional learning squads that meet regularly to solve current operational problems and share lessons; Implement rapid feedback loops: short reflection sessions after projects, learning retrospectives, and publish “lessons-learned” briefs that encourage experimentation; Use learning analytics to measure which learning activities lead to behavior change (apply learning transfer metrics, on-the-job application rates); Responsible: L&D departments; innovation or transformation units; middle managers (as learning sponsors).

KPIs: number of experiments run/year; percent of pilots scaled; learning transfer rate (self-reported + manager-validated); reduction in cycle time for process improvements.

Timeline: pilots for CoPs and retrospectives (1–3 months); learning analytics setup (3–6 months).

9.4. Priority 4—Align Learning and Talent Systems with Succession Goals (Close the Loop)

Problem: Misalignment between talent development content and succession requirements can produce negative net effects on agility.

Action that can be implemented: Map competency frameworks used in succession planning to talent development curricula so training builds successor readiness; Incentivize managers to nominate staff for stretch assignments that count toward readiness (make rotations and projects visible in promotion criteria); Require that a portion of training budgets be allocated to cross-functional and experiential programs that feed succession pools; Responsible: HR strategy teams; line managers; compensation and rewards units.

KPIs: % of successors who completed role-relevant experiential learning; correlation between participation in development programs and succession readiness scores.

Timeline: mapping and policy change (2–4 months); incentives and budget alignment (next fiscal cycle).

9.5. Priority 5—Modernize Systems and Data to Support Evidence-Based HR Decisions

Problem: Without real-time data, HR decisions are slow and opaque.

Several actions are as follows: Invest in HR analytics platforms that integrate performance, learning, mobility, and readiness data. Use dashboards to track critical KPIs and early-warning signals; Standardize reporting mechanisms for succession readiness and workforce agility metrics to senior management and boards; Pilot simple predictive analytics to identify flight risk, skill decay, and training ROI; Responsible: HR + IT; external analytics vendors; SAMA (recommend standard KPIs for sector benchmarking).

KPIs: % of HR decisions supported by analytics; reduction in time to identify skill gaps; improvements in training ROI.

Timeline: analytics pilot (3–6 months); roll-out (6–12 months).

9.6. Priority 6—Policy and Ecosystem-Level Actions (For Regulators and Policymakers)

Problem: Systemic incentives and supply-side constraints can limit bank-level action.

For the policy and ecosystem level, these actions can be implemented: Guidance, not heavy regulation: SAMA and Ministry of HR can issue best-practice guidance on succession planning and learning-aligned talent development, including recommended minimal governance standards for critical positions; Public–private reskilling funds: Create co-funded reskilling initiatives (banks + government + universities) to accelerate upskilling in digital and analytics skills needed across the sector; Accreditation and recognition: Encourage recognized micro-credentials or competency badges that link to career ladders—make them part of Saudization-friendly workforce planning; Sectoral benchmarking: Facilitate anonymized benchmarking across banks for leadership readiness, internal mobility, and learning-transfer metrics to create healthy competition and knowledge sharing; Responsible: SAMA; Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development; banking associations; universities and training providers.

KPIs: number of co-funded programs; uptake of accredited micro-credentials; sector-wide improvements in leadership readiness.

Timeline: policy guidance (3–6 months); reskilling fund design and launch (6–12 months).

10. Theoretical Contributions