Abstract

The demolition of historic residential buildings generates substantial construction and demolition waste, the effective management of which is essential for advancing circular economy objectives. This study presents a BIM-based waste management framework developed for European residential buildings constructed around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, reflecting their characteristic construction methods and material use. The framework employs a predefined structural and material database to automatically quantify waste streams from BIM data at LOD 300. Demolition materials are classified into eight categories consistent with the waste hierarchy: reuse, recycling, energy recovery, and disposal. The model also accounts for the influence of demolition techniques, enabling comparative scenario analysis of recovery outcomes. A Budapest case study demonstrated that selective manual demolition increases the proportion of high-value reuse from 19.6% to 56.8% compared to mechanical demolition, while preserving 88% of salvaged bricks and 90% of architectural stone elements. Although the framework was tested on a building in Budapest, the results are extendable to the wider Central European (Austro-Hungarian) building stock due to typological similarities. The findings confirm the framework’s capacity to support sustainable, circular waste management strategies in historic building demolition.

1. Introduction

The European building stock accounts for approximately 40% of the continent’s primary energy consumption [1] and is responsible for 3% of energy-related greenhouse gas emissions [2]. Moreover, construction and demolition activities generate more than one-third of the total waste produced in the European Union, which highlights that the success of the circular economy is largely determined by the performance of the construction industry [3]. The Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP), adopted in 2020, along with the Renovation Wave, identifies the “construction and buildings” sector as a priority area, promoting longer product and material life cycles [4]. The major cities of Central and Eastern Europe—including Budapest (Hungary)—face particularly complex challenges in this regard. A vast number of residential buildings with significant cultural value require intervention, yet market dynamics often favor complete demolition over the more costly process of rehabilitation. In Budapest, buildings constructed around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries are especially at risk. Although many of them are officially protected as cultural heritage, decades of neglect have brought them increasingly close to a state of disrepair that renders demolition imminent. In Hungary, there are approximately 4.59 million dwellings, nearly two-thirds of which were built before 1980 [5]—a proportion that is similarly high in many major European cities. A significant share of this stock is outdated in terms of energy performance, structural integrity, and comfort. Consequently, large-scale renovation activities are anticipated, which are expected to substantially increase the volume of construction and demolition waste (CDW). In this context, circular material management, logistics, and waste recycling represent strategic challenges. The capital city plays a pivotal role in shaping national energy, housing, and urban policies. Budapest alone accounts for one-fifth of the country’s total housing stock: as of 1 January 2025, 973.656 dwellings were registered, 38.9% of which were built before 1945 according to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office [6,7]. This represents a remarkable heritage value, yet these buildings often suffer from significant shortcomings in terms of comfort (such as elevators and accessibility) and energy performance. The inadequacy of historic building maintenance is particularly evident in the inner districts of Budapest, where a high proportion of the building stock consists of brick tenement houses constructed at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. These tenement houses were originally developed by private investors for rental purposes; however, many of them were transferred to state and later municipal ownership during the socialist period. After the mass privatizations of the 1990s, most of these buildings now function as condominiums, yet a substantial part of the remaining municipal housing stock is still concentrated within them. While these buildings possess considerable architectural character, they are structurally deteriorated and highly energy-inefficient [8]. Due to the underfunded maintenance during the socialist era and the mass privatization following the political transition, the renovation of these buildings has often been neglected. In the early decades of the 21st century, investor-driven logic has frequently favored complete demolition over modernization. However, such decisions also carry significant environmental implications: in the European Union, construction and demolition activities generate 820–858 million tonnes of waste annually, accounting for 25–30% of total waste [9]. Hungary’s recycling rate in this sector remains below 30%, falling far short of the EU’s 70% target. The deteriorated condition of many buildings is partly due to the absence of standardized renovation methodologies, and partly to the opacity of housing conditions and ownership structures. A substantial number of dwellings (102,468) are under municipal ownership [10], and due to their deteriorating condition, the number of rentable dwellings is steadily decreasing, while a significant proportion of the municipal housing stock remains vacant and unrented—amounting to 20,764 units. This is partly attributable to the lack of state-funded support programs or financial resources dedicated to the modernization and expansion of the municipal housing stock [11]. In contrast, regulatory pressure is continuously increasing: the Renovation Wave strategy aims to renovate 35 million buildings across Europe by 2030, at least doubling the annual renovation rate. At the same time, it seeks to reduce energy poverty and strengthen the green economy by relying on domestic labor [12,13]. All of this conveys that the renewal of the building stock is no longer merely a technical or aesthetic undertaking, but a strategic instrument in Europe’s climate and resource policy.

International studies have demonstrated that selective, material-based demolition can reduce climate change impact by 77%, acidification potential by 57%, and photochemical oxidation by as much as 81% [14]. In Hungary, a unified waste management and decision-support framework tailored to the specific characteristics of the building stock has so far been lacking—one that would transparently rank intervention alternatives. The novelty of this study lies not in the creation of waste calculation principles per se, but in their specific adaptation and automation for this challenging historic building typology, where standard BIM tools often prove insufficient. This research aims to address this gap by developing a BIM-based circular demolition decision-support model. The novelty of this study lies not in the creation of waste calculation principles per se, but in their specific adaptation and automation for this challenging historic building typology, where standard BIM tools often prove insufficient.

Consequently, the primary objective of this research is to establish a methodology for automating the quantification of demolition waste in historic buildings by leveraging LOD 300 BIM data. Furthermore, the study seeks to evaluate the quantifiable impact of different demolition technologies—specifically contrasting selective deconstruction with mechanical demolition—on the circular potential of building materials characteristic of the Austro-Hungarian heritage. This paper proposes an automated system specifically optimized for European urban residential buildings constructed in the mid-19th and early 20th centuries—a typology representing a significant portion of the building stock. Starting from a Level of Development (LOD) 300 Building Information Modeling (BIM) model, in accordance with the BIM forum specification [15], the system enables the quantification of demolition waste generated during building dismantling and the classification of this waste according to sustainability criteria. Classification is performed following relevant waste management categories (reuse, recycling, recovery, disposal) aligned with the European Waste Catalogue [16]. A key objective in the system’s design was the integration of environmental factors—such as minimizing carbon footprint, protecting the health of surrounding communities, and maximizing the reuse and recycling of demolished materials—into the decision-support algorithm with optimized weighting. This paper presents the circular demolition decision-support model, providing a framework applicable at the European level for minimizing construction and demolition waste and promoting value-added recycling. After a literature review, the fundamental components of the system, the applied methodologies, and computational approaches are described. The system’s operation is demonstrated through a case study of a residential building located in Budapest’s 7th district.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Residential Buildings in Budapest from the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries

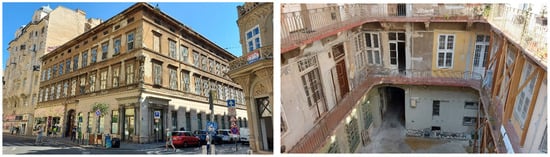

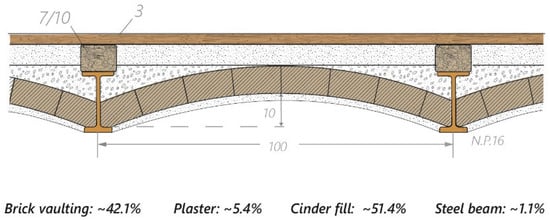

The tenement houses of Pest constructed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise [8], represent characteristic and outstanding examples of European architecture from the period. Originally constructed as multi-story, closed-row buildings with internal courtyards, they embody the urban lifestyle and social structure of their era. Their distinctive spatial organization and high-quality materials—including brick walls, Prussian vaults, and timber joist floor—continue to distinguish these buildings within Budapest’s architectural heritage (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Typical residential buildings in Budapest constructed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, in the early decades of the 21st century, this building stock has come under considerable threat, as urban development and investment priorities have at times favored complete demolition over modernization [9]. While demolition may initially appear to be more cost-effective, it entails significant losses from urban, historical, and sustainability perspectives. The greatest value lies, on the one hand, in the structural system and material quality—the robust masonry walls and floor structures remain suitable for contemporary upgrades—and, on the other hand, in the characteristic interior layout, which, with appropriate design and carefully negotiated compromises, can be adapted to meet modern functional requirements. Following the neglect of historic urban districts during the mid-20th century, the second half of the century saw a renewed focus on their revitalization. In this context, several blocks in the inner city of Budapest underwent a combination of demolition, renovation, and new construction [10]—including, for instance, the 7th district, which is also addressed later in the case study. The building stock was surveyed, and most of the inner wings of the blocks were demolished, while the remaining buildings were renovated. Although the development brought significant progress to the area, the replacement of the original population and the disappearance of the historic streetscapes remain subjects of criticism to this day [11]. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that nowadays a large proportion of these buildings are under local or national heritage protection. In Hungary, heritage buildings are currently classified into two main categories: monuments of outstanding national importance and protected monuments. According to Act LXIV of 2001 on the Protection of Cultural Heritage, protected buildings are considered part of the national cultural heritage, and their legal protection is intended to ensure their preservation. The number of residential buildings in Budapest constructed before 1945 approaches 116,000, accounting for approximately 61% of the city’s 190,000 built properties [6]. According to the official national heritage register, approximately 15,000 properties in Hungary are under monument protection, of which around 2400 are located in Budapest. In addition, the capital’s municipal register of locally protected buildings lists approximately 1300 individual buildings, encompassing nearly 1500 structures when building complexes are included. However, the actual number of residential buildings with historical value is significantly higher—estimated at 60,000 to 70,000—of which only a small fraction are currently under any form of legal protection.

Through the digitalization of the construction sector, architects have gained access to advanced tools that enable the sustainable rehabilitation of neglected tenement buildings of significant architectural value. These tools facilitate the integration of environmental, architectural, social, and economic considerations into the design process, thereby supporting a holistic and contemporary approach to urban renewal. A compelling example is a one-story tenement building constructed in 1845 in Budapest’s 6th district, for which multiple development scenarios were examined—ranging from complete demolition to full preservation [17]. The adopted strategy retained the historical street façade, combined with the internal renovation of the existing structure and the addition of new building elements. This approach allowed for the preservation of key architectural values while enabling functional and technical modernization. The use of the Scan-to-BIM methodology provided an effective tool for the accurate documentation and informed decision-making required for the project’s implementation. Although such projects represent exemplary cases of heritage-sensitive urban renewal, the set of evaluation criteria applied in the assessment of alternative development scenarios could be further extended—particularly through the inclusion of construction and demolition waste management, energy performance and sustainability-related considerations. The integration of these additional aspects would enable a more comprehensive and multidimensional evaluation process, thereby enhancing the quality of decision support. However, a practically applicable and integrated framework to support such complex assessments is currently lacking.

2.2. Trends and Tools of Demolition Waste Management

The volume and management practices of demolition waste vary significantly across Europe, which can be attributed to a range of factors, including differences in national waste management practices, regulatory frameworks, and infrastructural capacities. While countries such as Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Austria report recycling rates exceeding 70% for demolition waste, this rate remains considerably lower in Eastern Europe, typically below 30% [14,18]. According to Hungary’s National Waste Management Plan [19], the recycling rate of construction waste in the country falls below the European average. This underscores the need for sustainable waste management strategies that are aligned with the principles of the circular economy [14,16,20].

The Waste Framework Directive [21] lays down the basis for waste management in Europe; this is a hierarchical system with the prevention of waste generation at the top. This is followed by preparing for re-use, which involves inspecting, cleaning, or repairing waste materials to make them suitable for recovery operations, allowing them to be re-used without any additional pre-processing. If this is not possible, the next preferred option is recycling, which refers to any recovery process in which waste materials are transformed into products, materials, or substances, either for their original purpose or for other uses. Recent research, such as the work by Hussien et al. [22], highlights how reincorporating waste additives—including agricultural or construction by-products—into structural materials can enhance their physical properties, thereby actively supporting the practical implementation of circular economy principles. The next option is recovery, which refers to any operation where waste is used for a useful purpose by replacing other materials that would otherwise have been used to fulfill a specific function, or where waste is prepared to serve that function, either within the plant or in the broader economy. This includes backfilling, which involves using suitable waste for reclamation in excavated areas or for engineering purposes in landscaping or construction, replacing other non-waste materials that would otherwise be needed for these tasks. This also includes energy recovery, where the waste materials are used as fuels. At the bottom of the hierarchy is disposal, which involves transporting waste to a landfill and is considered the least desirable option.

The application of circular economy principles in demolition waste management can lead to significant improvements, particularly in urban environments. A key aspect of this approach is the accurate quantitative and qualitative assessment of materials contained in buildings slated for demolition, the identification of hazardous substances, and the use of Building Information Modeling (BIM), which provides detailed material inventories and rich data content. These methods enable the structured and sustainable reuse and recycling of materials, thereby substantially reducing the environmental impact of demolition waste [23]. Ideally, this approach is integrated already during the design phase of the building, for which numerous examples can be found in the international literature [24]. This is the concept of Design for Deconstruction (DfD), which can significantly contribute to minimizing end-of-life building waste [25]; however, it does not offer a solution for the management of existing buildings.

The literature highlights that selective demolition—i.e., the separation and collection of waste materials during the demolition process—can yield substantial environmental benefits, particularly in terms of mitigating impacts related to climate change, acidification, and the formation of summer smog [20,26]. The careful deconstruction of existing buildings and the segregation of materials for potential reuse is a process that requires considerable time and space, making it economically unfeasible in most cases [27]—except for certain particularly valuable components. Nevertheless, salvaged elements with inherent value—such as architectural ornaments or historically significant timber flooring—could be marketed within the heritage restoration sector or the high-end residential construction market [28], while other parts of the building can be reused or recycled. Rose and Stegeman [29] demonstrated that one of the main challenge of selective deconstruction is that valuable building parts are not known in advance, which problem could be solved through the application of BIM. Nowadays an increasing number of research focuses on managing construction and demolition waste using BIM. Among the digital tools of the CDW management Kabirfar et al. [18] lists BIM first, alongside Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), Global Positioning System (GPS), Big Data (BD), and Geographic Information System (GIS). Recent studies, such as Schamne et al. [30], emphasize that BIM-based conceptual models utilizing the IFC standard can effectively address limitations in CDW management by automating waste quantification and indicator analysis. For instance, phase planning (4D simulation), quantity take-off and site utilization planning can help to avoid double material handling and time-consuming and non-systematic CDW quantification, while BIM-based design review and construction system design can increase the reuse and recycling rates [31]. Kang et al. [32] developed a conceptual framework for waste quantity assessment, demolition process planning and waste transportation system using point cloud-based BIM models and IoT (Internet of Things) tools on site. Shi and Xu [33] demonstrated a BIM-based CDW information system using Revit software to predict disposal costs and carbon emissions.

However, there are still many limitations and challenges of adopting BIM in CDW management, particularly in the case of existing buildings. Research has primarily focused on construction waste, while studies aiming to minimize demolition waste are less prevalent [34], which can be attributed to several factors. On the one hand, an important limiting factor is that effective demolition waste management requires a BIM model reflecting the existing condition of the building, the creation of which is highly time-consuming. Although the issue of waste management is particularly important in the context of the renovation or demolition of existing buildings, current BIM systems primarily target new constructions, Heritage Building Information Modelling (HBIM) approaches adapted for historic buildings remain underdeveloped. The HBIM literature consistently highlights that current BIM authoring tools are inadequately aligned with the specific conditions of historic fabric, as most of these applications were primarily developed for the design of contemporary buildings and therefore prove ill-suited to the requirements of historic contexts [35]. J. Edwards [36] aims to address this issue by proposing the introduction of Existing Building Information Modelling (EBIM), which focuses on the general maintenance and management of buildings. Existing BIM protocols are not adequately suited to the specific data management and preservation requirements of historical structures. The current functionalities of digital models are limited, and the stringent accuracy requirements combined with the complexity of data integration hinder the applicability of HBIM. On the other hand, significant barriers include the lack of interoperability between BIM systems and waste management tools, as well as the limited availability of the necessary know-how to implement such solutions.

3. Framework for Demolition Waste Management

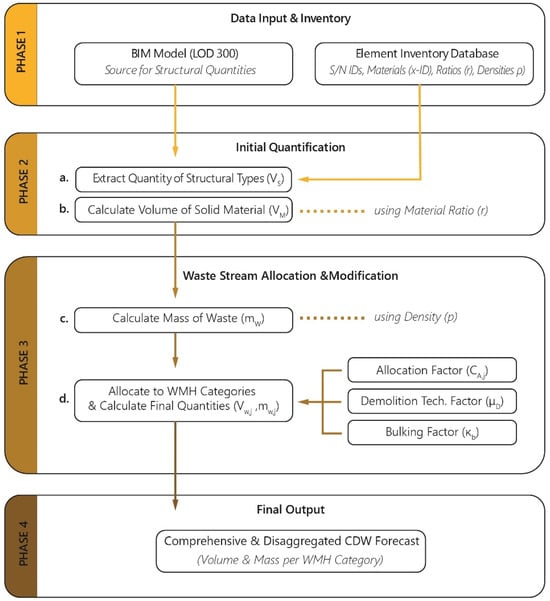

This chapter details the methodology of the automated framework developed for the quantification and categorization of construction and demolition waste (CDW) generated from historic buildings. The system is based on a structured, multi-layered approach that integrates BIM data with a predefined material and component database in order to predict waste streams in accordance with the European waste hierarchy. The operational logic of the framework—illustrated in Figure 2—comprises several key stages, from initial data collection to the final categorization of waste streams. The algorithmic logic follows a four-step sequence: (1) ID matching: the script scans BIM elements and matches their ‘Structural ID’ with the external material database. (2) Decomposition: composite elements (e.g., S401 Prussian Vault) are decomposed into constituent materials (bricks, steel beams) using the predefined ratios (r). (3) Conversion: volumes are converted to mass using specific density values (r). (4) Allocation: finally, the mass is distributed into waste categories based on the demolition technology factor (mD) assigned to the specific scenario.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the BIM-based framework for demolition waste quantification.

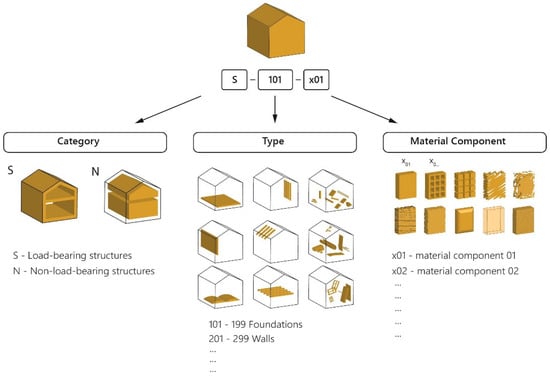

The methodology begins with a detailed inventory of the building components characteristic of the examined building type—namely, multi-story residential buildings constructed in Central Europe between the mid-19th and early 20th centuries. These structural elements are first classified into two main categories: (1) load-bearing structures and (2) non-load-bearing structures. Both categories are further subdivided into specific structural types (e.g., Prussian vaults, timber beam floors) that are representative of the construction practices of the period. For each structural type, the constituent materials and their volumetric proportions (r) within the composite element are determined based on historical construction practices. To ensure systematic data management and traceability, a hierarchical identification system is employed, assigning a unique identifier to each structural type and its constituent materials.

The initial volumes of these structural types (Vs) are directly extracted from a BIM model developed to Level of Development (LOD) 300 according to the specification of the BIMforum [15]. While the model is capable of processing data in various units (m3, m2, m), all quantities are subsequently normalized to volumetric units (m3) to ensure consistency. The volume of each solid material component (VM) is then calculated by multiplying the total structural volume (Vs) with the corresponding material ratio (r). Following this, the mass of each waste component (mw) is determined by applying the appropriate material density (ρ), sourced from an internal database comprising 13 distinct waste types (W01–W13). The final stage of the framework involves classifying these quantified material flows into eight waste management categories, in accordance with the principles of the EU waste hierarchy [21] (i.e., reuse, recycling, energy recovery, and disposal). This classification is governed by a set of material-specific allocation factors (CA,j), derived from a reference scenario. To account for real-world conditions, the model integrates two critical modifying parameters: the demolition correction factor (μD), which quantifies the impact of the selected demolition method (e.g., manual vs. mechanical) on material integrity, and the bulking factor (kb), which adjusts for the volumetric expansion of materials during the transition from solid to loose state. The output of the framework is a comprehensive and detailed prediction of CDW, specifying the volume and mass of individual material flows, as well as their distribution across the defined waste management categories. This systematic approach provides a robust foundation for the sustainable planning and execution of deconstruction projects involving historic buildings.

3.1. Data Input and Element Inventory

The applicability of the model was validated for multi-story residential buildings constructed using traditional technologies between 1850 and 1920 in Central Europe, with particular focus on the Hungarian capital, Budapest. This building stock represents a well-defined and specific local typology shaped by the rapid urbanization of the period, as well as by local construction practices and regulatory frameworks. A characteristic feature of this typology is the built form organized around closed or semi-closed inner courtyards, typically complemented by lateral and rear building wings. As a result—unlike in many other European cities—these buildings commonly incorporate side corridors or balconies, which provide circulation to the courtyard-facing apartments. Another defining aspect of the typology is the absence of reinforced concrete load-bearing elements in their original structural systems, which reflects the construction techniques of the era.

The basis of the developed system is a detailed Element Inventory, empirically informed by case studies conducted in cooperation with a district municipality in Budapest. In compiling the inventory, the model’s scope was restricted to those structural element types that are characteristic of the examined building typology and historical period, thereby excluding atypical components introduced during later renovations. The structural elements included in the inventory were classified into two main categories: load-bearing (S) and non-load-bearing structures (N). The load-bearing category comprises foundations, wall structures, lintels, floor structures, balconies and side corridors, staircases, and roof structures. The non-load-bearing category includes floor and wall finishes, windows and doors, railings, and various building services and installation components. Within each category, the relevant specific structural types were defined. Table 1 lists the structural types found in the case study building located at Király Street 29, Budapest, Hungary, which is discussed in greater detail in Section 4.

Table 1.

Element Inventory.

To ensure clear data management within the database, a hierarchical identification system was introduced. Load-bearing structures are denoted with the prefix S (structural), while non-load-bearing structures are marked with the prefix N (non-structural). Each structural type is linked to its constituent building materials, which are identified using an x prefix followed by a serial number. As a result, a classification system was established (Figure 3) that clearly indicates the structural origin of each material. This is essential for determining both the applicable demolition technologies and the feasible reuse or recycling pathways. The system is designed to be flexible and scalable: the identifier structure can be extended to accommodate additional building types. For instance, a Prussian vault floor present in this building is assigned the identifier S401 and comprises five primary material components: steel beam (x01), large-format brick (x02), mortar (x03), plaster (x04), and slag fill (x05). Accordingly, the large-format brick used in this specific floor structure is uniquely identified in the model as S401-x02.

Figure 3.

Logic of the applied hierarchic material classification system.

This classification system can be easily imported into BIM software environments, enabling the automated categorization of model elements and facilitating more efficient quantity take-offs. The purpose of developing the Element Inventory at such a detailed level was to establish a robust and expandable database that encompasses all building components likely to generate significant waste streams during demolition. This comprehensive approach provides a solid foundation for ensuring both the accuracy and the granularity of the CDW management model.

3.2. Initial Quantification

It is assumed that a model of the examined building is developed at LOD 300 according to the LOD Specification published by the BIMforum [15], including the main load-bearing elements, such as foundations, walls, columns, slabs, beams, roof structures, the chimneys, the partition walls, the stairs, the openings, and the railings. LOD300 means that individual components are represented with accurate dimensions; however, subcomponents (e.g., the joists in a timber floor structure) are not modeled separately. Furthermore, the model does not include composite structures, mechanical or electrical equipment, or furniture. This level of detail can still be considered realistic in the context of surveying existing buildings; constructing a model with higher accuracy, however, becomes extremely time-consuming and may not be economically justified.

Waste management planning typically requires two types of material quantities: on the one hand, the net volume of a given building element, from which the amount of waste generated can be directly calculated; and on the other hand, the gross volume, which is derived from the element’s bounding dimensions and is necessary for estimating storage and transportation needs. For several elements—such as wall structures, brick vaults, balconies, stair structures, roof structures, and railings—both the net and gross volumes can be extracted directly from the model elements. However, in the case of elements that were either not modeled or not represented in sufficient detail to allow for accurate quantity extraction, derived quantities and estimations can be used.

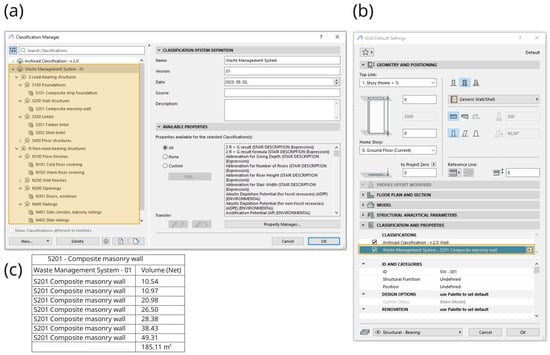

For the development of the method, Archicad 27 was used, which enables the import and application of custom classification systems. The hierarchical classification system presented in Chapter 3.1 was imported into the software in XML format (Figure 4a), and during the modeling process, each element was assigned to the appropriate class (Figure 4b). In addition, an attribute was created that, based on the assigned class, generates a precise identifier for each element by concatenating the identifiers of the higher-level categories. This identifier is also included in the quantity take-off (Figure 4c), thereby facilitating the identification and categorization of elements within the waste management hierarchy (see Section 3.3).

Figure 4.

(a) Imported classification system, (b) Assigning class to the elements, (c) Quantity take-off using the created ID system.

This method is suitable for generating an initial quantity take-off of the elements represented in the model. However, waste management requires information on the quantities of the individual materials composing each building element (see Table 1). There are just a few elements for which no additional calculations are required. These include, for example, stair structures, side corridors (side corridors) and their supports, as well as the timber components of the roof structure, all of which can be accurately extracted from the model. In other cases, using these lists as a basis, the quantities of the components can be determined through calculations and engineering judgment-based estimations.

For example, the foundation level is typically unknown, as excavation is generally not carried out. Although original 19th-century plans are often available in archives, they rarely accurately document the current foundation depth. Therefore, using a standardized estimation formula based on wall thickness provides a more consistent database for waste calculation than relying on uncertain archival data. However, in the case of the examined building type, it is known that usually strip foundations were used. Based on practical experience, the width of the foundation was estimated to be 20% greater than the thickness of the wall above, and its depth was estimated as 40 cm for parts of the building with a basement and 80 cm for parts without a basement. To perform this calculation, the thickness and length of the ground floor walls must be extracted from the BIM model. The volume of the foundation can then be determined using Formula (1):

where lw,G is the length of the walls on the ground floor in building parts without a basement; bw,G is the thickness of the walls on the ground floor in building parts without a basement; lw,B is the length of the walls on the ground floor in building parts with a basement; bw,B is the thickness of the walls on the ground floor in building parts with a basement.

In the case of slab structures, additional calculations are typically required to determine the quantities of individual components. However, since the structural configurations of the slab types characteristic of the period are well known, the floor area—which can be accurately obtained from the model—is sufficient for the quantity calculations. An example of this is the Prussian vault, where the quantities of the steel beams, brick vault, slag infill, and plaster can be derived from the area of the modeled slab element. To support this, a detailed calculation was performed on a selected slab section, during which the specific quantities of each component per square meter of slab area were determined (Figure 5). Based on this approach, the exact material quantities can also be calculated for other floor structures with similar configurations.

Figure 5.

Determination of the quantities of the components of the Prussian vault.

Building elements such as finishes and their components can also be derived from the model, based on the areas obtained from individual rooms. Similarly, the volume of the components constituting the openings can be estimated based on the surface area extracted from the model, applying average values and distinguishing only between windows and doors.

The framework also accounts for kitchen furniture, sanitary installations, rainwater drainage systems, the electrical network, and other building services such as heating and wastewater systems. These elements are not represented in the model; therefore, a standardized configuration is assumed for each apartment. Quantities are estimated based on floor area and room function, using data from the literature and professional experience. It is important to note, however, that significant variations may exist between individual apartments, as many have undergone multiple alterations or renovations over time. Consequently, the calculated values should be considered approximations in these cases. An example of this is the electrical system, where an average wiring length of 0.6 m/m2 was assumed based on the floor area of the apartments. The proportion of each component within the corresponding building element, as determined through this method, has been recorded within the framework, allowing it to be applied to similar buildings in future analyses.

3.3. Waste Stream Allocation

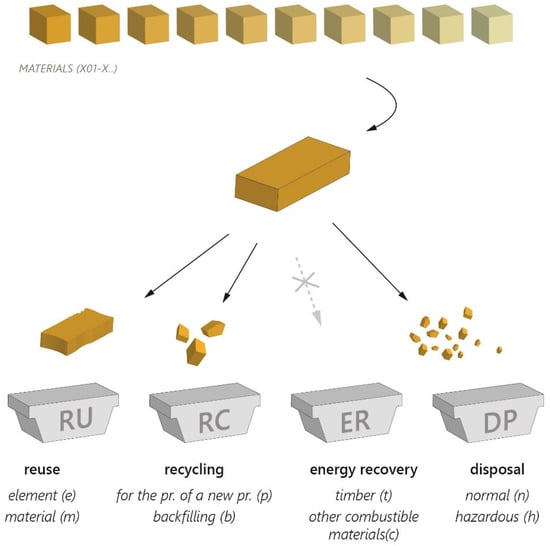

Waste Management Hierarchy

The applicability of waste management categories was examined for CDW generated from the deconstruction of multi-story urban residential buildings constructed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The analysis was conducted not only at the material level but also at the building element level, with particular attention given to typology-specific components characteristic of this building stock (e.g., limestone cantilevers and slabs of side corridors, steel beams of Prussian vault floors, etc.). For each structural element, all applicable waste management categories were identified, depending on the post-demolition condition of the element. A waste management hierarchy comprising four main categories—reuse, recycling, energy recovery, and disposal—was adopted, with each category further subdivided into two subcategories (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The applied Waste Management Hierarchy—Applicable to pre-modern masonry multi-story residential buildings from the 19th and early 20th centuries, constructed with traditional techniques.

The reuse/element subcategory includes architecturally or structurally significant components that can be directly reintegrated into new construction in their original or similar function. Examples include floor beams, stair treads, stone slabs of side corridors, ornamental façade elements, and railings. The reuse/material subcategory within reuse encompasses materials such as undamaged salvaged bricks or roof tiles that may be reused without the need for further industrial processing. Reuse is contingent upon the elements’ physical integrity and their resistance to damage during the deconstruction process.

In contrast, the recycling/for the production of a new product subcategory includes materials such as steel or timber waste, which are processed into entirely new products through industrial means (e.g., melting, reprocessing). The most valuable and frequently recycled fraction is metal waste. Cast iron and steel waste streams may include cast-iron radiators, wastewater and heating pipes, and hot-rolled steel beams or railings. Following smelting in foundries, these materials can yield nearly 100% material recovery. Non-ferrous metals, such as copper and zinc, recovered from wiring, fittings, or plumbing components, can also be remanufactured into new products through similar metallurgical processes. Clean, untreated timber can be processed through shredding to produce a key raw material for engineered wood products. Only timber that is free from chemical treatments—such as fungicides, insecticides, or fire retardants—is considered suitable for recycling. The recycling/backfilling subcategory includes clean, inert demolition debris (e.g., brick, concrete), which can be mechanically crushed and graded, then used as construction aggregate for applications such as sub-base layers, grading, or excavation backfilling. The energy recovery/timber subcategory comprises clean and untreated wood that cannot be reused or recycled otherwise but can be combusted to generate heat and/or electricity. The energy recovery/other combustive material subcategory includes other non-hazardous combustible materials for which energy recovery through incineration is the only viable reuse pathway. The disposal/normal subcategory includes non-hazardous demolition waste that cannot be reused or recycled by any other means and is therefore disposed of in regulated landfills. While this group predominantly consists of inert demolition debris, untreated wood (e.g., structural timber, doors and windows), metal waste, glass waste, as well as soil and slag excavated during demolition works may also be included. The disposal/hazardous subcategory comprises waste classified as hazardous to human health or the environment, such as asbestos-containing materials or bauxite concrete. These materials must be collected, treated, and permanently disposed of or destroyed in accordance with legal regulations, typically in sealed and secure landfill sites designed for hazardous waste.

3.4. Demolition Waste Calculation

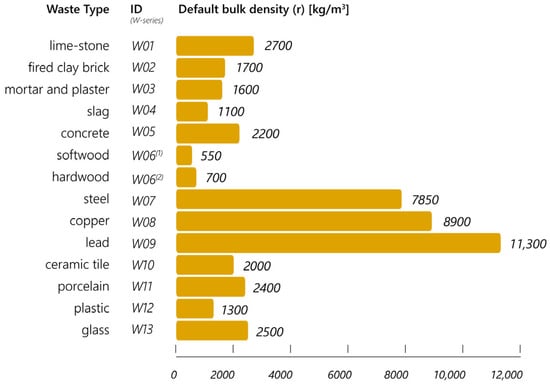

3.4.1. Determination of Waste Types and Bulk Density of Materials

As part of the research methodology, each constituent material of the examined structural element types was assigned to a relevant demolition waste category, based on its anticipated post-demolition treatment pathway. A total of 13 primary waste categories were defined for the classification of the entire demolition material stream. Figure 7 summarizes the applied waste types, their corresponding identification codes, and the default bulk density values (kg/m3) assigned to each category for calculation purposes. These bulk density values were used to convert volumetric estimates into mass-based quantities, thereby enabling a comprehensive quantification of the potential CDW generated.

Figure 7.

Applied waste types and their corresponding default bulk densities. (W06(1): softwood subcategory, W06(2): hardwood subcategory).

In the case of metal waste (e.g., steel, copper, lead), density values can be considered constant due to the relatively low variability in their physical properties. In contrast, the bulk density of other waste categories is subject to significant variation. Accordingly, the selection of representative density values was based on a detailed analysis of historical construction practices, including the typical materials and technologies used during the relevant period.

For wood waste (W06), bulk density is known to vary widely—from 350 to 1080 kg/m3—depending on wood species, moisture content, and material quality. Based on the characteristic use of timber in the examined building typology, two subcategories were distinguished:

- (a)

- Softwood (W06/1): Roof structures were typically constructed from coniferous species, primarily Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), with smaller proportions of spruce and fir. The density of these species generally ranges between 430 and 650 kg/m3. According to The Wood Database [37], the average oven-dry density of Scots pine is approximately 550 kg/m3, which corresponds to the value adopted in the present calculations. This value is considered to represent a realistic average for timber of varying quality and origin.

- (b)

- Hardwood (W06/2): The load-bearing elements of heavily loaded floor structures (e.g., tenon-jointed beam floors) were predominantly made from higher-density hardwood species, most commonly oak (Quercus spp.), and to a lesser extent beech or ash. While the use of softwood has occasionally been observed in intermediate floors—due to the reduced load requirements—the predominance of hardwood in intermediate floors justified the use of a single representative density value for all such applications. The density of these hardwood species typically falls between 650 and 750 kg/m3 [38], with a value of 700 kg/m3 applied in the model.

The density of mortar and plaster (W03) is known to vary widely—typically between 1400 and 2000 kg/m3—depending on the binder-to-aggregate ratio and the composition of raw materials. In these buildings, pure lime mortars and plasters made from natural hydraulic limes were commonly used. These materials tend to have lower densities due to their higher porosity and the lower specific weight of lime as a binder [39]. During later renovations—particularly those carried out from the early 20th century onwards, and in post-war repair works—repair mortars and plasters containing early forms of Portland cement were frequently applied, resulting in materials of higher density [40].

Considering the mixed use of materials typical of the analyzed building type—both during initial construction and subsequent repairs—a uniform density value of 1600 kg/m3 was defined for the calculations. The density values for the remaining waste types were determined in an analogous manner, based on an assessment of historical construction techniques and the materials typically used during the relevant period.

3.4.2. Methodology for Waste Stream Classification

Construction and demolition waste constitutes a heterogeneous material flow, the components of which must be classified according to different levels of the waste management hierarchy [41]. The proportional distribution of material flows among the various categories is determined by numerous interacting factors. The developed methodology addresses the effects of these factors at a systems level. The most significant influencing factors are the following:

- Demolition technology and selectivity: The technological implementation of demolition fundamentally determines the integrity of the recovered structural elements and materials. Selective demolition (e.g., manual dismantling) enables the extraction of elements (e.g., bricks, timber beams) with minimal or no damage, thereby maximizing the potential for element-level reuse (reuse/element). In contrast, mechanical demolition typically results in fragmentation of the elements, which leads to the classification of materials into lower levels of the waste hierarchy, such as recycling or disposal categories.

- Physical condition of structural elements: Pre-demolition condition assessments play a crucial role. Degradation processes impairing the integrity of structural elements—such as advanced corrosion of steel structures or biological damage caused by pests (e.g., fungi, insects) to wooden components—can exclude their reuse. While elements in sound condition are preferably assigned to the reuse/element category, damaged components are generally suitable only for material recovery (recycling) or energy recovery.

- Material properties and bonding between components: The demolishability of complex structures (e.g., foundations, masonry, vaults) and the recoverability of their components are closely dependent on the type and quality of the applied binding materials. In the case of weak hydraulic, loose lime mortars, a relatively high recovery rate of masonry elements (brick, stone) in intact condition is enabled. In contrast, when high-strength cement mortars are used, the probability of damage to masonry elements during demolition is increased, resulting in a decreased proportion of reusable fractions.

- Cultural and historical value: Architectural or heritage-significant structural elements (e.g., carved stone cantilevers, ornate facade decorations) are given priority for element-level reuse (reuse/element), even if this requires minor restoration interventions. The preservation and secondary reuse of such elements are justified from sustainability and cultural heritage protection perspectives, regardless of the building’s protection status [42].

The developed framework is based on a waste management reference scenario selected from a sustainability perspective. This scenario is built upon the following basic assumptions:

- The physical and technical condition of the examined structural elements is assumed to be adequate, allowing for treatment at the highest levels of the waste hierarchy.

- The demolition process is carried out using selective technology, minimizing damage to the elements.

- The classification of each waste fraction is performed according to the most favorable option defined by the waste management hierarchy, in order to maximize sustainability.

The waste management classification of non-load-bearing structures requires a thorough understanding of the examined building type. In Central Europe, particularly in residential buildings constructed before 1950, wooden windows, doors, and other timber fittings were commonly treated with lead-based oil paints, typically containing lead carbonate [43]. The presence of lead may be indicated by thick, layered, and cracked paint coatings, as well as yellowish-white, grey, or heavily pigmented (e.g., dark green, red) coloration. In cases of suspicion, on-site lead testing is recommended. If the presence of lead in the paint is confirmed, the affected timber must be classified as hazardous waste (disposal/hazardous). The energy recovery of such materials through incineration is strictly prohibited due to the emission of toxic lead vapors. In the model, based on literature data and on-site observations, 80% of wooden windows and doors were considered to be coated with lead-based paint. This conservative estimate (80%) is based on the historical prevalence of lead-based primers (e.g., minimum) widely used in the region during the 19th and 20th centuries. Following a ‘safety first’ principle, the aim was to avoid underestimating the amount of hazardous waste, as chemical testing of every element is not feasible during demolition. The remaining 20% were assumed to be non-hazardous and suitable for energy recovery (energy recovery/timber). The potential waste management routes have been determined for each building component. For example, when demolishing a composite masonry wall, the brick and stone materials can be allocated to the reuse (material), recycling (backfilling), or disposal (normal) categories (Figure 8). Mortar debris is typically assigned to the backfilling or disposal categories, whereas plaster—due to its potential content of paint and other contaminants—can only be classified as disposal (normal).

Figure 8.

Possible waste management streams of a brick.

Based on the principles described, the optimal distribution of waste types generated from the dismantling of each structural element has been defined according to the reference scenario (hereinafter: “Scenario A”). During the execution of the model, this ideal distribution is modified by correction factors (Table 2) that account for real-world conditions (e.g., non-selective demolition technology, bulking factor). The detailed methodology for determining these proportions is presented in Section 3.4.3 and Section 3.4.4.

Table 2.

Allocation factors.

3.4.3. The Impact of Demolition Technology on Waste Stream Distribution

The CDW streams and their reuse potential are fundamentally influenced by the demolition technology applied. The literature clearly distinguishes between selective deconstruction (typically manual or low-mechanization demolition) and conventional mechanical demolition, with the former enabling significantly higher rates of material- and element-level reuse [44]. The developed model accounts for this impact through a dedicated modification factor.

Definition and Application of the Demolition Technology Modification Factor (μD)

The model’s starting point is an ideal scenario (“Scenario A”) that is most favorable from the perspective of the waste hierarchy, assuming selective deconstruction. The impact of conventional mechanical demolition (e.g., the use of a hydraulic hammer), which involves greater damage and fragmentation of elements, is quantified by the demolition technology modification factor (μD). This factor is applied in cases where a given building material would, under the ideal scenario, be partially or entirely allocated to the reuse/element or reuse/material waste management categories (WMC). The μD factor is a value between 0 and 1, representing the fraction of the originally reusable portion that actually remains in the reuse category after mechanical demolition. The calculation methodology is as follows:

- For manual demolition (selective deconstruction), μD = 1, meaning the distribution among WMCs is not modified.

- For mechanical demolition, the new proportion for the reuse category is calculated by multiplying the original proportion by the modification factor.

The fraction lost from the reuse category increases the proportion of the next relevant category in the waste hierarchy, which is typically recycling. The μD values assigned to different structural types and materials are summarized in Table 3. The μD factors in Table 3 were calibrated based on a synthesis of empirical data from the literature and expert estimations regarding the behavior of historical structures [45].

Table 3.

Demolition technology-dependent correction factors (μD).

Methodological Assumption: The Role of Mortar Type

A fundamental assumption in the development of the model is that the masonry structures of the historical buildings studied were predominantly constructed with lime mortar. This assumption is critical because the lower compressive strength and greater flexibility of lime mortar—in contrast to modern, high-strength cement mortars—allow for a significantly higher recovery rate of masonry units (e.g., bricks) during demolition. The brittle, strong bond of cement mortar causes a substantial portion of bricks to break, drastically reducing their reuse potential, even with selective demolition [46]. Although later repairs using cement-based mortars may be present in the building stock under investigation, their proportion is considered negligible; thus, the model uniformly assumes the use of lime mortar.

Application of the Modification Factor: Case Studies

Composite Masonry Wall (S201): This structure consists of limestone and large-format bricks. Under mechanical demolition, the reuse (material) share of limestone decreases from 60% to 40%, and that of brick from 85% to 10%. This change is modeled using the modification factors mD,stone = 0.66 and mD,brick = 0.12.

Prussian Vault Floor (S402): Ideally, 90% of the steel beams are reusable as elements (reuse/element). During mechanical demolition, this proportion is reduced to 65% due to deformation. The applied modification factor is mD,steel = 0.72.

Brick Vault (S401): With selective demolition, 80% of the bricks can be salvaged (reuse/material). In mechanical demolition, this rate drops to 10% due to severe fragmentation. The corresponding modification factor is mD,brick,vault = 0.13.

The WMC classification of mortar, plaster, and slag infill is not affected by the demolition technology, as these materials are not allocated to the reuse category in the first place.

3.4.4. The Role and Application of the Bulking Factor (kb)

When planning the logistics and subsequent management (e.g., reuse, recycling) of demolished building materials, converting their volume from a solid, in situ state to a loose, bulk state is a crucial step. This increase in volume, which occurs due to the fragmentation of materials and the increase in void space between particles, is accounted for by the dimensionless bulking factor (kb) [47]. The kb parameter is essential for determining the volume of waste to be transported and the required transport capacity, as well as for accurately quantifying the amount of material fed into recycling processes.

The value of the bulking factor is not a universal constant; it is influenced by several factors, including the type of material, particle size distribution, moisture content, and the demolition technology used. The bulking factors applied in the model were determined based on literature data and empirical values from building demolition projects, taking into account selective material handling and the typical demolition procedure for the given component [48]. Table 4 summarizes the differentiated kb values used in the model for each material type.

Table 4.

Applied bulking factors (kb) by material and component.

The differences in the values presented in the table can be attributed to physical reasons. Timber and steel elements have exceptionally high bulking factors. Elongated, rigid, and regularly shaped elements (e.g., I-beams) form an irregular pile, enclosing a significant volume of void space. The bulking factor for steel elements varies slightly depending on whether they are intended for element-level reuse (reuse/element, kb = 4.0) or material recycling (recycling, kb = 5.0). The reason lies in logistics: elements designated for reuse are more valuable and are therefore stacked and transported in an orderly manner to prevent damage, allowing for a more compact arrangement than the bulk piling of materials intended for recycling [49,50]. In the current system, the bulking factor for steel elements is taken as the average of these two values. In contrast, plaster and mortar (kb = 1.3) pulverize to a large extent during demolition, and the fine-grained fractions can efficiently fill the voids between larger pieces, resulting in a lower volume increase. Materials that break into irregular pieces from a solid structure (brick, concrete, limestone) fall into the medium range (kb = 1.5).

3.4.5. Determination of the Volume and Mass of Demolition Waste

Section 3.4.5 presents the mathematical framework for quantifying the volume and mass of waste streams originating from demolition. The model is built upon the basic quantities defined in previous sections (e.g., structural volume, (Vs), material ratios (r), densities (ρ)), as well as the developed modification factors (bulking factor (kb), demolition technology factor (μD)) and allocation ratios (CA,j). This chapter first illustrates the calculation logic using the reuse category and then outlines a generalized model that can be extended to all categories of the waste management hierarchy.

Calculation of Reusable Waste Quantity

The model determines the volume and mass of waste from a given material m originating from a structure type s that falls into the reusable category using separate formulas. The calculation of the bulked volume of reusable waste (VW,RU) requires the inclusion of the bulking factor (kb), while the calculation of mass (mW,RU) involves density (ρ). The general formula for the volume of reusable waste for material m from structure s is (Equation (2)):

where VW,RU (s,m) is the bulked volume of reusable waste to be transported, originating from material component m of structure type s (m3); Vs(s) is the total solid (in situ) volume of structure type s (m3); r(s,m) is the percentage of material m within structure type s (%); CA,RU(s,m) is the reuse allocation factor for material m of structure s according to “Criterion A”, based on the waste management hierarchy, which is a dimensionless multiplier indicating the fraction of the material to be reused; μD(s,m) is the correction factor dependent on the demolition technology, expressing the degree of material damage (dimensionless); kb(s,m) is the bulking factor characteristic of material m, describing the post-demolition increase in volume (dimensionless).

The general formula for the mass of reusable waste is (Equation (3)):

where is the mass of reusable waste to be transported, originating from material component m of structure type s; is the density of material m (kg/m3).

At the total project level, the total quantity of all reusable waste is obtained by summing the values calculated for each structure-material pair. The total reusable volume (VW,RU,total) and mass (mW,RU,total) can be aggregated as follows (Equations (4) and (5)):

Generalized Model for Waste Stream Determination

The calculation logic demonstrated for reuse can be extended to all categories of the waste management hierarchy. By introducing an index j, we define a comprehensive, generalized model capable of estimating the quantity and mass of all possible waste streams from demolition. To more accurately model the impact of demolition technology, the framework is supplemented with a new dimensionless factor, the flow redistribution factor (φD(s,m)). The role of this factor is twofold: first, it ensures that the effect of the demolition technology modification factor (μD) is applied at the appropriate levels of the waste hierarchy, and second, it mathematically handles the redistribution of material flows between categories. The volume (VW,j) of waste of material m from structure type s belonging to category j is determined by the following general formula (Equation (6)):

where VW,j(s,m) is the bulked volume of waste from material m of structure s, classified into category j (m3); CA,j(s,m) is the general allocation factor for material m of structure s according to “Criterion A”. which specifies the fraction of the material allocated to category j (dimensionless), is the flow redistribution factor, which handles the material flow redistribution resulting from the impact of demolition technology (dimensionless); j is the index of the waste management category, identifying the possible treatment routes.

The mass (mW,j) of waste belonging to category j is given by the following formula (Equation (7)):

where mW,j(s,m) is the mass of waste from material m of structure s, classified into category j (t).

The value of the φD(s,m) factor is defined by a piecewise function, which depends on the waste management category j and its corresponding allocation factor. It is the flow redistribution factor, which handles the material flow redistribution resulting from the impact of demolition technology. To ensure the mathematical validity of the model, the demolition technology modification factor must satisfy the condition 0 < μD(s,m) ≤ 1. (Equation (8)):

The index j and its corresponding allocation factors in this research cover the following 8 categories (Table 5).

Table 5.

Allocation factors.

A fundamental condition for the internal consistency of the model is that the total quantity of a given (s,m) structure-material pair must be fully distributed among the possible treatment categories. This is ensured by the following condition (Equation (9)):

The total volume (VW,total) and mass (mW,total) of all waste generated during the entire demolition project can be determined by summing the quantities across all structures, materials, and waste management categories (Equations (10) and (11)):

This generalized approach allows for a detailed yet systemic analysis of heterogeneous waste streams from demolition projects, providing a solid foundation for the planning and evaluation of circular economy strategies.

4. Case Study: Application and Validation of the Framework

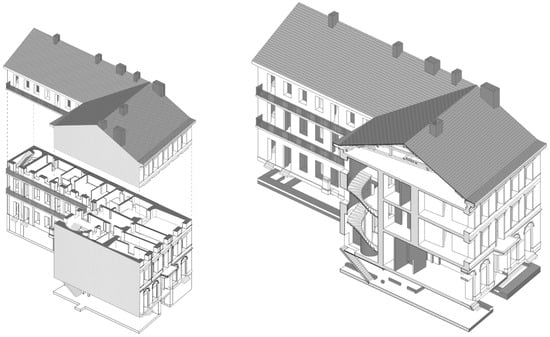

To demonstrate and validate the practical applicability of the developed BIM-based waste management model, a case study is presented. The subject of the investigation is a late 19th-century residential building located in downtown Budapest (Király u. 29), which is representative of the typology central to this research. This chapter describes the building, the operation of the framework, and quantifies the impact of different demolition technologies on the distribution of the resulting waste streams.

4.1. Building Description

The residential building was constructed between 1843 and 1847 based on the designs of József Hild, a renowned Hungarian architect of the era. The closed-row building, executed in the Classicist style, is flanked by a three-story structure to the northeast and a two-story building to the southwest. The street-facing wing contains two commercial premises on the ground floor, both accessible from the street. The property is entirely owned by the local municipality.

The building features a ground floor plus two upper stories, a full basement, and a pitched roof with tile covering; access to courtyard-facing flats is provided by side corridors. The structure is organized around an internal courtyard with a side wing, creating an L-shaped floor plan. On the first and second floors, the street-facing wing is designed with two and three tracts, respectively, while the side wing has a single-tract layout. The main staircase is situated in the street-facing wing, whereas a secondary staircase is located at the end of the side wing. With the exception of the section beneath the carriage gateway, the entire building is equipped with a cellar. The apartments in the side wing are accessible via the side corridors.

4.2. Investigated Demolition Scenarios

The input data for determining the structural quantities (Vs) were provided by the LOD 300 BIM model of the building (Figure 9). The model was developed using Archicad 27, where quantity take-offs were generated using the method described in Section 3.2.

Figure 9.

Model of the building.

To analyze the impact of demolition technology, two fundamental scenarios were examined:

- Scenario 1 (Selective deconstruction): This assumes manual and small-scale mechanical demolition methods aimed at the maximum, non-destructive recovery of building materials and structural elements. In this case, the value of the demolition technology modification factor is μD = 1.

- Scenario 2 (Conventional mechanical demolition): This models conventional, heavy-machinery demolition (e.g., hydraulic hammer), which is faster but results in significant fragmentation of materials. In this case, the values of the μD factor are the material-differentiated values defined in Table 4.

4.3. Results

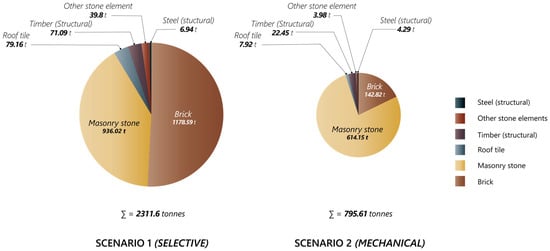

The results of the case study are summarized in Table 6 and Table 7. The calculations present the quantity and distribution of the resulting waste streams for the two basic scenarios introduced in Section 4.2: (1) Selective deconstruction and (2) Conventional mechanical demolition. The results clearly confirm that the choice of demolition technology fundamentally determines the circular potential of the recovered materials. Table 6 illustrates the percentage distribution of the total demolition waste mass across the four main categories of the waste management hierarchy.

Table 6.

Distribution of waste streams by demolition technology (mass %).

Table 7.

Variation in the quantity of key reusable materials (in tonnes).

From the table, it can be observed that selective deconstruction allows more than half (56.8%) of the building’s total demolition waste to be allocated to the highest value-added reuse category. In contrast, conventional mechanical demolition drastically reduces this proportion by 37.2 percentage points. Almost the entire displaced fraction is devalued into the lower-value recycling category, whose share increases from 36.5% to 73.7%. The proportion of materials designated for energy recovery and disposal is not affected by the demolition technology in the current phase of the model. Table 7 examines the most affected category, Reuse, in more detail, showing the change in the absolute quantity of the most important recoverable materials.

The results highlight that the impact of mechanical demolition is highly material-specific (Figure 10). The most drastic loss is observed in the case of salvaged brick (nearly −88%), as well as in elements with architectural value, such as limestone cantilevers and slabs. These building materials are prone to breaking and fragmenting under mechanical impact, thereby losing a significant part of their reuse potential. In contrast, the more robust masonry stones (−34.39%) and the more ductile steel structures (−38.20%) are the least sensitive to the technology. This variation is a consequence of applying different demolition technology modification factors (μD) characteristic of the various materials. The model is capable of not only demonstrating the redistribution of waste streams but also identifying which materials are most sensitive to the selection of an inappropriate demolition technology.

Figure 10.

Loss or reusable materials due to mechanical demolition.

The results highlight a critical finding: while both scenarios achieve high overall recovery rates, the quality of this recovery is fundamentally different. Mechanical demolition leads to a significant devaluation of materials, shifting nearly 40% of the total waste mass from the high-value reuse category to the lower-value recycling category. The most drastic losses, approaching 90%, are seen in brittle, historically significant components such as salvaged brick, roof tiles, and stone elements (e.g., carved limestone cantilever of the side corridor), indicating that conventional demolition practices irreversibly destroy the highest-potential circular value inherent in historic buildings.

5. Discussion

This chapter places the obtained results into a broader context, interprets the relationships revealed by the model, and defines the limitations of the current research and directions for future development.

5.1. Evaluation of the Framework

The practical implementation of the proposed system does not require any additional tools beyond those commonly used in current engineering practice. The integration of the collected data into a database enables straightforward application as well as interoperability with BIM software. In the case study, Archicad 27 and Microsoft Excel were employed; however, most BIM authoring tools support the import and export of tabular or text-based data, which means that the method is not restricted to a single software environment.

Although the developed element inventory was tailored to a specific building type that is widely represented in Europe, the applied identification system allows for extensibility and adaptation to additional building types. It is important to emphasize that while the current database is built on Hungarian historical standards, the structure of the framework is universal. Specific material characteristics (e.g., density, component ratios) can be easily substituted with local historical data from other European regions without modifying the central calculation algorithm. Furthermore, since the ‘Budapest typology’ (solid brick masonry, Prussian vault floors) is the standardized legacy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the model is directly applicable to the historic districts of Vienna, Prague, or Krakow. It is also worth noting that the selected building type, a substantial knowledge base has been established, drawing on both literature and extensive professional experience, which enables the estimation of the quantity and type of demolition waste generated.

This approach requires a BIM model with a level of detail corresponding to LOD300, which is commonly applied in the documentation of existing buildings. Supplemented with engineering estimations, such a model allows for the quantification of building materials and their classification into waste categories without significant additional time investment. In the case study, material quantities were exported into Excel following their categorization, where further processing, data aggregation, and evaluation were performed. Nevertheless, the methodology also allows for a more advanced level of BIM implementation: if the required data (such as bulk density or potential waste stream options) are defined as attributes within the BIM software, the calculations can be performed directly in the BIM environment, with the additional possibility of visual representation.

5.2. The Relationship Between Demolition Technology and the Circular Economy

The case study results quantitatively support the widely accepted thesis in the literature that the choice of demolition technology is one of the most critical factors determining the success of keeping materials from historic buildings in circulation. The model demonstrated that the “loss” incurred during mechanical demolition is not merely quantitative but also qualitative: materials are devalued from higher levels of the waste hierarchy (Reuse) to lower levels (Recycling, Disposal). This highlights the importance of planning deconstruction projects, where the demolition plan must integrate material recovery goals from the very beginning. The presented BIM-based framework provides an effective decision-support tool for designers and contractors, enabling the comparison of different scenarios and the selection of the most sustainable strategy.

It is important to emphasize that our research does not support or encourage the demolition of historic buildings. On the contrary: we consider their preservation a priority. It must be emphasized that from a holistic Circular Economy perspective, the renovation of historic buildings is generally environmentally superior to demolition due to the high embodied carbon of new construction. Our framework does not promote demolition but offers a ‘damage mitigation’ tool for cases where demolition is unavoidable due to structural deterioration. Future research should analyze the comparative cumulative carbon footprint of demolition versus renovation. The present study addresses only those rare cases where a structure is already deemed irretrievably damaged and demolition cannot be avoided. In such situations, our focus is on how the dismantling process can be carried out in a professional and responsible way, ensuring that as many valuable materials and structural elements as possible are salvaged and reused.

However, the scope of this analysis extends beyond simply optimizing an undesirable outcome. Establishing a detailed, data-driven model for the “full demolition” scenario serves as a critical baseline for a more ambitious, long-term research objective. Our ultimate goal is to evolve the current system into a comprehensive, multi-criteria decision-support tool. Such a framework would be capable of evaluating and comparing a range of potential intervention scenarios that influence a building’s fate including—not only demolition but also full-scale renovation, adaptive reuse, or attic conversions. A thorough understanding of the material flows, costs, and environmental impacts of a complete demolition is a methodologically indispensable prerequisite for quantifying the relative benefits of preservation-oriented alternatives. Without this baseline, a holistic and objective comparison of different strategies would not be possible.

Our findings highlight a critical limitation in current waste management policies, especially concerning the specific historic building stock under investigation, as these policies often focus solely on quantitative recovery targets, such as the EU’s 70% goal. The case study demonstrates that while mechanical demolition may achieve a high total recovery rate, it does so primarily through low-value downcycling, a process during which elements of architectural and heritage value (e.g., carved stone cantilevers, salvaged bricks) are irreversibly destroyed. In contrast, selective deconstruction preserves these materials for high-value reuse, aligning far better not only with the true principles of the circular economy but also with the principles of heritage preservation. This suggests that future policies should incorporate quality-based metrics -distinguishing between reuse, high-grade recycling, and backfilling—to incentivize the preservation of both material and architectural value rather than mere waste diversion from landfills. Our BIM-based model provides a practical tool for implementing and monitoring such nuanced policies at the project level.

While this study analyzes a single building, its findings can be scaled to illustrate a challenge extending across the entirety of a city’s historic districts, particularly in the case of a historical building stock with a unique character like that of Budapest. Given that a significant portion of these buildings contain structures of heritage or architectural value—such as ornate railings, carved stone structural elements, or decorative façade components—the material loss quantified in our case study represents a fraction of a much larger potential loss of resources and cultural value. Extrapolating these findings suggests that conventional demolition practices at an urban scale could lead to the irreversible loss of hundreds of thousands of tonnes of valuable, irreplaceable historic building materials annually. This underscores that for this specific building typology, selective deconstruction is not just a policy for sustainable urban renewal and resource management, but also a key tool for the preservation of built heritage.

5.3. Limitations of the Framework and Future Research Directions

Although the presented model provides a robust framework, it is important to highlight its current limitations, which also outline directions for future research:

- Neglect of structural condition: The current model assumes an ideal, impeccable physical and technical condition. In reality, the degradation of structural elements (e.g., corrosion, biological damage) can significantly affect their reuse potential. The next phase of the research aims to supplement the model with a condition assessment module capable of quantifying the extent of damage and modeling its impact through the allocation factors. In practice, we envision this in the form of integration with the CBDF system [51].

- Cultural and architectural value: The model currently does not differentiate between unique elements with architectural value and those forming a mass structure. In the future, we plan to integrate a “heritage” factor that identifies elements of particular importance from a cultural heritage perspective, mandating manual demolition and reuse (reuse/element) for them, overriding purely economic or technological considerations.

- Flexibility of input data: The system is currently based on LOD 300 BIM models. The next development step is to create a module that can also import data from traditional 2D survey documentation (floor plans, sections), thereby significantly increasing the model’s applicability for less-documented building stock.

- Refinement of parameters: Further refinement of the modification factors used in the model (e.g., kb, μD) is necessary. We plan to differentiate the bulking factor according to waste management categories (e.g., a different kb value for orderly stacked reusable beams versus bulk metal scrap for recycling), which would further improve the accuracy of logistics planning.