Shallow Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment in the Plain Area of Baoji City, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Research Methods and Data Sources

3.1. Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment Model

3.2. Groundwater Vulnerability Assessment

3.2.1. Pore/Fissure Groundwater Vulnerability Assessment

3.2.2. Karst Groundwater Vulnerability Assessment

3.3. Groundwater Pollution Load Assessment

3.4. Groundwater Value Function Assessment

3.5. Determination of Weight

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Groundwater Vulnerability Assessment Results

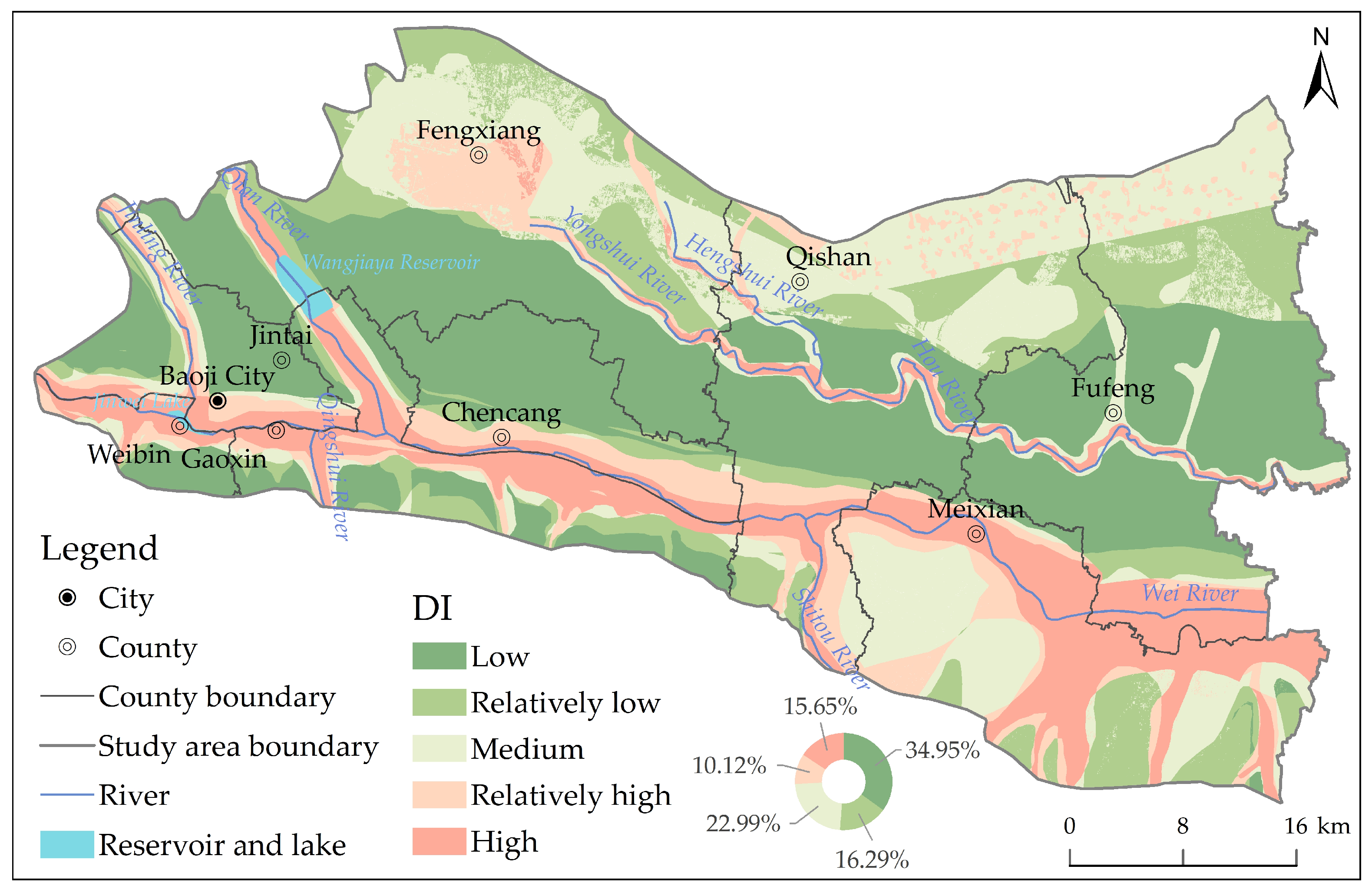

4.2. Groundwater Pollution Load Assessment Results

4.3. Groundwater Value Function Assessment Results

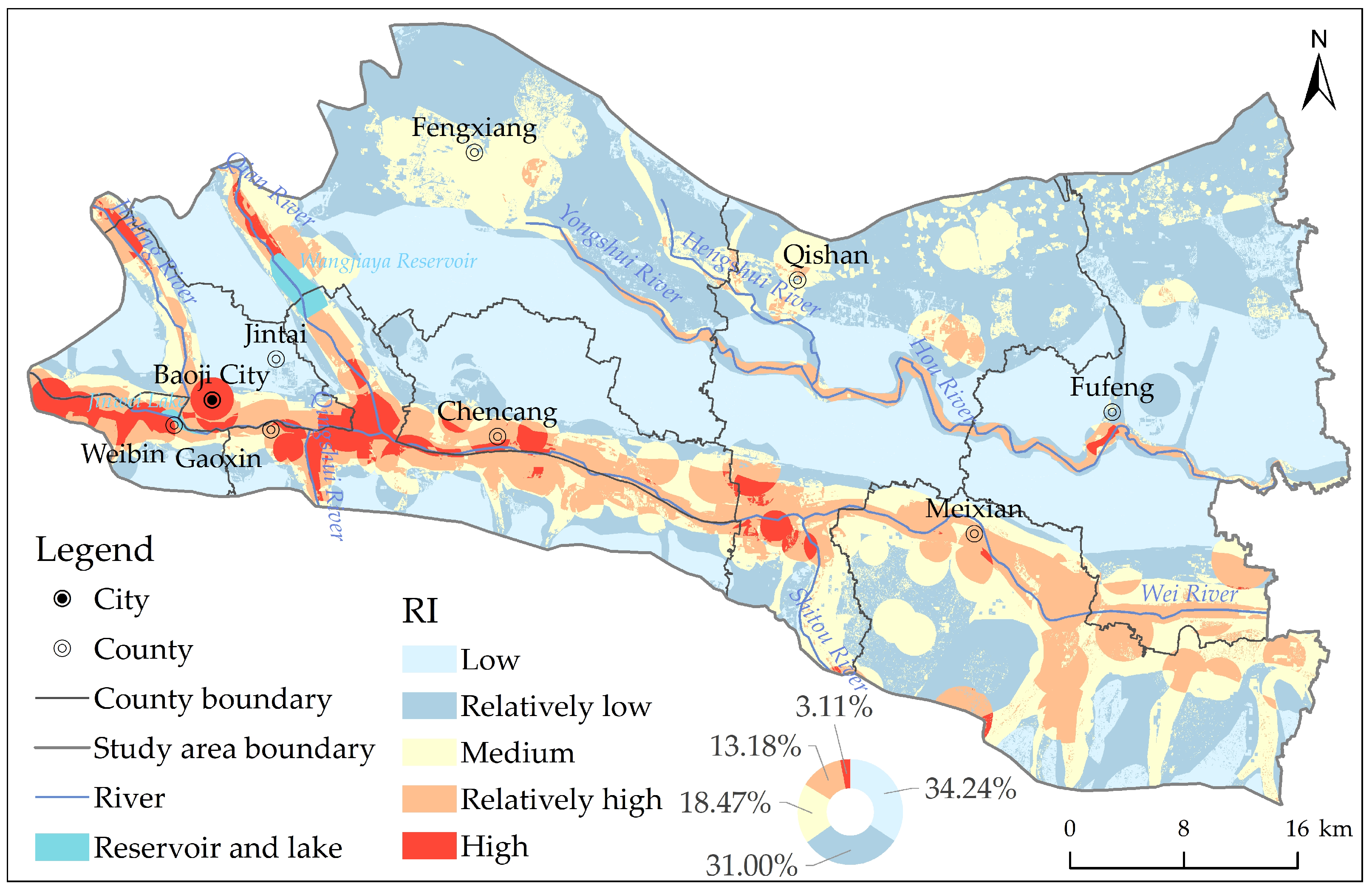

4.4. Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment Results

4.5. Model Comparison

4.6. Single-Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The study area’s groundwater vulnerability is low overall. Areas with high and relatively high vulnerability account for approximately 25.77% of the Baoji Plain and are predominantly located in the floodplain areas along the Wei River and its tributaries, largely due to the shallow groundwater level, highly permeable vadose zone, and high aquifer hydraulic conductivity.

- (2)

- The study area’s groundwater pollution load is generally at a low level. High and relatively high pollution load areas account for approximately 5.15% of the Baoji Plain and are mainly distributed in the banks of the Wei River and its tributaries, primarily due to the superposition of pollutants from industrial activities and gas stations.

- (3)

- The study area’s groundwater value function level is mainly medium or relatively low. Approximately 6.26% of the study area exhibits high and relatively high value function. Zones along the Wei River are attributed to dense populations and intense economic activities, while those in the northeastern Qishan County, western Fufeng County, and southeastern Mei County are mainly attributable to good water quality.

- (4)

- Compared with the traditional DRASTIC model, the evaluation results of the improved DRSTICW superimposed pollution risk model are more in line with the actual pollution status of groundwater. The optimized assessment shows that the proportion of high and relatively high pollution risk areas accounts for 3.72%, which is 12.57% lower than that of the traditional model. These high and relatively high pollution risk areas are predominantly located in the western floodplain area, where both the groundwater vulnerability and pollution load levels are high. Furthermore, the groundwater here possesses considerable value. If no measures are taken to prevent and control groundwater pollution, it will cause serious health risks and economic losses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Evaluation Type | Data Name | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Pore/fissure groundwater vulnerability assessment (DI1) | Depth to water table (D) |

|

| Net recharge (R) |

| |

| Soil media (S) |

| |

| Topographic slope (T) |

| |

| Impact of the vadose zone (I) |

| |

| Hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer (C) |

| |

| Water abundance of the aquifer (W) |

| |

| Karst groundwater vulnerability assessment (DI2) | Protective cover (P) |

|

| Land use type (L) |

| |

| Epikarst development (E) |

| |

| Recharge condition (I) |

| |

| Karst network development (K) |

| |

| Groundwater pollution load assessment (PI) | Groundwater pollution sources data |

|

| Groundwater value function assessment (FI) | Groundwater quality (Q) |

|

| Nighttime light index (H) |

| |

| Habitat quality index (E) |

|

| Models | Indicators | Application | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRASTIC | Depth to water table, net recharge, aquifer medium soil media, topography slope, impact of vadose zone, hydraulic conductivity of aquifer | Common groundwater vulnerability assessment models |

| The indicators are fixed and require improvement based on the regional hydrogeological conditions. |

| GOD | Groundwater occurrence, overall lithology of the unsaturated zone, depth to water table | Regions with limited data |

| Less accurate than DRASTIC. |

| SI | Depth to water table, net recharge, aquifer medium, topography slope, land use | Regions with agricultural contamination such as nitrate |

| This method omits the effect of groundwater circulation on the accumulation or diffusion of pollutants. |

| SINTACS | SINTACS model adopts identical parameters as DRASTIC | Suitable for Mediterranean conditions and has five diverse weighting methods depending on hydrogeological conditions |

| More complex than DRASTIC and requires detailed input data. |

| PLEIK | Protective cover, land use type, epikarst development, recharge condition, karst network development | Karst groundwater vulnerability assessment |

| Not applicable to non-karst areas. |

| D/m | R/mm·a−1 | S | T/(°) | I | C/mm·d−1 | W/m3·d−1 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >30 | 0 | Bedrock | >10 | Clay | (0,4] | (1000,5000] | 1 |

| (25,30] | (0,51] | Clay | (9,10] | Sub-clay | (4,12] | - | 2 |

| (20,25] | (51,71] | Silty loam | (8,9] | Sub-sand | (12,20] | - | 3 |

| (15,20] | (71,92] | Loam | (7,8] | Silty sand | (20,30] | (100,1000] | 4 |

| (10,15] | (92,117] | Sandy loam | (6,7] | Silty fine sand | (30,35] | - | 5 |

| (8,10] | (117,147] | Swelling or aggregated clay | (5,6] | Fine sand | (35,40] | (10,100] | 6 |

| (6,8] | (147,178] | Silty sand, fine sand | (4,5] | Medium sand | (40,60] | - | 7 |

| (4,6] | (178,216] | Gravel/medium sand, coarse sand | (3,4] | Coarse sand | (60,80] | <10 | 8 |

| (2,4] | (216,235] | Pebble gravel | (2,3] | Sandy gravel | (80,100] | - | 9 |

| ≤2 | >235 | Thin or missing | ≤2 | Pebble gravel | >100 | - | 10 |

| Indexes | Class | Protective Cover Thicknesses | Score Matrix (CEC (meq/100 g)) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A 1 | B 2 | <10 | 10–100 | 100–200 | >200 | |||

| P | P1 | 0–20 cm | 0–20 cm | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | |

| P2 | 20–100 cm | 20–100 cm | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | ||

| P3 | 100–150 cm | 100 cm | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||

| P4 | >150 cm | >100 cm or non-karst strata | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||

| L | Class | Land use | Score | |||||

| L1 | Forest | 1 | ||||||

| L2 | Grass land | 3 | ||||||

| L3 | Garden land | 5 | ||||||

| L4 | Farmland | 7 | ||||||

| L5 | Bare land | 9 | ||||||

| L6 | Urban and industrial land | 10 | ||||||

| E | Class | Epikarst development | Score | |||||

| E1 | Strongly developed epikarst zone | 10 | ||||||

| E2 | Highly developed epikarst zone | 8 | ||||||

| E3 | Moderately developed epikarst zone | 6 | ||||||

| E4 | Mildly developed epikarst zone | 4 | ||||||

| E5 | Modestly developed epikarst zone | 2 | ||||||

| I | Class | Infiltration conditions | Score matrix (rain intensity (mm/d)) | |||||

| <10 | 10–25 | >25 | ||||||

| I1 | 500 m area around the sinkhole or subterranean stream | 4 | [5,9] | 10 | ||||

| I2 | 500 m–1000 m area around the sinkhole or subterranean stream, farming area with confluence slope > 10%, grass area with slope > 25% | 3 | [4,7] | 8 | ||||

| I3 | 500 m–1000 m area around the sinkhole or subterranean stream, farming area with confluence slope > 10%, grass area with slope > 25% | 2 | [3,5] | 6 | ||||

| I4 | The rest of the catchment | 1 | [2,3] | 4 | ||||

| K | Class | Karst network | Moduli (L·s−1·km−2) | Score | ||||

| K1 | Strongly developed karst network | >15 | [8,10] | |||||

| K2 | Moderately developed karst network | 7~15 | [6,7] | |||||

| K3 | Weakly developed karst network | 1~7 | [4,5] | |||||

| K4 | Mixed and fractured aquifers | <1 | [1,3] | |||||

| Pollution Source | Toxicity Category | Score (Ti) | Buffer Radius/km | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial pollution source | Industry of oil processing and cooking, industry of nuclear fuel processing | 2.5 | 1.5 | |

| Industry of colored metals smelting and pressing | 3 | 1 | ||

| Industry of black metals smelting and pressing | 2 | 1 | ||

| Chemicals and chemical products | 2.5 | 2 | ||

| Industry of spinning | 1 | 2 | ||

| Industry of leather, fur, feathers, and their products | 1 | 2 | ||

| Fabricated metal products | 1.5 | 1 | ||

| Other industry | 0.2 | 1 | ||

| Landfill site | Domestic waste | 1.5 | 2 | |

| Gas station | Petroleum hydrocarbon, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon | 2.5 | 1.5 | |

| Agricultural pollution source | Agricultural cultivation zone | Fertilizer, pesticide, heavy metals | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Large-scale livestock farms | Antibiotic drugs | 1 | 1 | |

| Pollution Sources | Likelihood of Release | Score (Li) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial pollution source (build time of the factory) | >2011 | 0.2 | |

| 1998–2011 | 0.6 | ||

| <1998 or no protective measures | 1.0 | ||

| Landfill site (operation period and standard) | ≤5 years, formal qualification of class I | 0.1 | |

| >5 years, formal qualification of class I | 0.2 | ||

| ≤5 years, formal qualification of class II | 0.2 | ||

| >5 years, formal qualification of class II | 0.4 | ||

| ≤5 years, formal qualification of class III | 0.4 | ||

| >5 years, formal qualification of class III | 0.5 | ||

| Informal, simple protection (class IV) | 0.6 | ||

| Informal, no protection (class IV) | 1 | ||

| Gas station (operation period and protection measures) | ≤5 years, dual tanks or anti-seepage pool | 0.1 | |

| (5,15] years, dual tanks or anti-seepage pool | 0.2 | ||

| >15 years, dual tanks or anti-seepage pool | 0.5 | ||

| ≤5 years, single tank without anti-seepage pool | 0.2 | ||

| (5,15] years, single tank without anti-seepage pool | 0.6 | ||

| >15 years, single tank without anti-seepage pool | 1.0 | ||

| Agricultural pollution source | Agricultural cultivation zone | Paddy field | 0.3 |

| Irrigated land | 0.5 | ||

| Dry land | 0.7 | ||

| Large-scale livestock farms | With protective measures | 0.3 | |

| No protective measures | 1.0 | ||

| Pollution Sources | Class | Score (Qi) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial pollution source (discharge quantity of wastewater; unit: 103 t/a) | ≤1 | 1 | |

| (1,5] | 2 | ||

| (5,10] | 4 | ||

| (10,50] | 6 | ||

| (50,100] | 8 | ||

| (100,500] | 9 | ||

| (500,1000] | 10 | ||

| >1000 | 12 | ||

| Landfill site (capacity of the landfill; unit: 103 m3) | ≤1000 | 4 | |

| (1000,5000] | 7 | ||

| >5000 | 9 | ||

| Gas station (the number of tanks with the capacity of 30 m3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Agricultural pollution source | Agricultural cultivation zone (amount of fertilizer; unit: kg/ha) | ≤180 | 1 |

| (180,225] | 3 | ||

| (225,400] | 5 | ||

| >400 | 7 | ||

| Large-scale livestock farms (COD emissions; unit: t/a) | ≤2 | 1 | |

| (2,10] | 2 | ||

| (10,50] | 4 | ||

| (50,100] | 6 | ||

| (100,150] | 8 | ||

| (150,200] | 9 | ||

| >200 | 10 | ||

| Groundwater Quality Class (Q) | Nighttime Light Index (H) | Habitat Quality (E) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Score | Range | Score | Range | Score |

| V | 1 | 0–4.78 | 1 | 0–0.14 | 1 |

| VI | 2 | 4.78–12.08 | 2 | 0.14–0.29 | 2 |

| III | 3 | 12.08–22.82 | 3 | 0.29–0.44 | 3 |

| II | 4 | 22.82–40.30 | 4 | ||

| I | 5 | 40.30–75.92 | 5 | ||

Appendix B

References

- Anonymous. World Water Day—making the invisible visible. Civ. Eng. Mag. South Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2022, 30, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Fannakh, A.; Károly, B.; Farsang, A.; Ben Ali, M. Evaluation of index-overlay methods for assessing shallow groundwater vulnerability in southeast Hungary. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirlas, M.C.; Karpouzos, D.K.; Georgiou, P.E.; Katsifarakis, K.L. A comparative study of groundwater vulnerability methods in a porous aquifer in Greece. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.X.; Liu, J.G.; Scanlon, B.R.; Jiao, J.J.; Jasechko, S.; Lancia, M.; Biskaborn, B.K.; Wada, Y.; Li, H.L.; Zeng, Z.Z.; et al. The changing nature of groundwater in the global water cycle. Science 2024, 383, eadf0630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.; Mishra, S.K.; Pandey, A.; Kalura, P. Inclusion of groundwater and socio-economic factors for assessing comprehensive drought vulnerability over Narmada River Basin, India: A geospatial approach. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF; World Health Organization. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2022: Special Focus on Gender; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Adimalla, N.; Qian, H. Groundwater quality and contamination: An application of GIS. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.A.; Shrestha, S.; Pandey, V.P. Groundwater vulnerability to climate change: A review of the assessment methodology. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 853–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Q.W.; Lin, Y.L.; Fang, Y.; Qian, H.; Liu, R.P.; Ma, H.Y. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics and Quality Assessment of Groundwater in an Irrigated Region, Northwest China. Water 2019, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haied, N.; Khadri, S.; Foufou, A.; Azlaoui, M.; Chaab, S.; Bougherira, N. Assessment of Groundwater Pollution Vulnerability, Hazard and Risk in a Semi-Arid Region. J. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Osta, M.; Niyazi, B.; Masoud, M. Groundwater evolution and vulnerability in semi-arid regions using modeling and GIS tools for sustainable development: Case study of Wadi Fatimah, Saudi Arabia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Ali, M. GIS-DRASTIC integrated approach for groundwater vulnerability assessment under soil erosion hot spot areas in Northern Pakistan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mena, B.; Morán-Ramírez, J.; Almanza-Tovar, O.G.; López-Alvarez, B.; Martínez-Morales, M.; Ramos-Leal, J.A. Aquifer vulnerability assessment in the oaxacan complex: Integrating the DRASTIC methodology, TEM, and water quality analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.S.; Zhang, J.W.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.H. Groundwater contamination risk assessment based on intrinsic vulnerability, pollution source assessment, and groundwater function zoning. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2019, 25, 1907–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margat, J. Vulnérabilité des Nappes D’eau Souterraine à la Pollution; BRGM Publication: Orleans, France, 1968; Volume 68. [Google Scholar]

- Machiwal, D.; Jha, M.K.; Singh, V.P.; Mohan, C. Assessment and mapping of groundwater vulnerability to pollution: Current status and challenges. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 901–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.N.; Wang, D.Q.; Xu, H.L.; Ding, Z.B.; Shi, Y.; Lu, Z.; Cheng, Z.J. Groundwater pollution risk assessment based on groundwater vulnerability and pollution load on an isolated island. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachniew, P.; Zurek, A.J.; Stumpp, C.; Gemitzi, A.; Gargini, A.; Filippini, M.; Rozanski, K.; Meeks, J.; Kværner, J.; Witczak, S. Toward operational methods for the assessment of intrinsic groundwater vulnerability: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 827–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anane, M.; Abidi, B.; Lachaal, F.; Limam, A.; Jellali, S. GIS-based DRASTIC, Pesticide DRASTIC and the Susceptibility Index (SI): Comparative study for evaluation of pollution potential in the Nabeul-Hammamet shallow aquifer, Tunisia. Hydrogeol. J. 2013, 21, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.N.; Liu, J.C.; Yuan, W.C.; Liu, W.J.; Ma, S.B.; Wang, Z.Y.; Li, T.T.; Wang, Y.W.; Wu, J. Groundwater Contamination Risk Assessment Based on Groundwater Vulnerability and Pollution Loading: A Case Study of Typical Karst Areas in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana-Macías, J.M.; Roselló, M.J.P. Assessment of Risk and Social Impact on Groundwater Pollution by Nitrates. Implementation in the Gallocanta Groundwater Body (NE Spain). Water 2022, 14, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabeo, A.; Pizzol, L.; Agostini, P.; Critto, A.; Giove, S.; Marcomini, A. Regional risk assessment for contaminated sites Part 1: Vulnerability assessment by multicriteria decision analysis. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, Z.G.; Zhao, S.Y.; Ma, Y.L.; Li, X.; Gao, H. Assessment of Groundwater Contamination Risk in Oilfield Drilling Sites Based on Groundwater Vulnerability, Pollution Source Hazard, and Groundwater Value Function in Yitong County. Water 2022, 14, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Fu, K.; Zhang, H.; He, G.Y.; Zhao, R.; Yang, C. A GIS-based analysis of intrinsic vulnerability, pollution load, and function value for the assessment of groundwater pollution and health risk. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2022, 28, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.W.; Qian, H.; Xu, P.P.; Hou, K. Hydrochemical Characteristic of Groundwater and Its Impact on Crop Yields in the Baojixia Irrigation Area, China. Water 2020, 12, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Z.Z.; Li, M.; Wu, H.M. Distributions and interactions of dissolved organic matter and heavy metals in shallow groundwater in Guanzhong basin of China. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsabimana, A.; Li, P.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Alam, S.M.K. Variation and multi-time series prediction of total hardness in groundwater of the Guanzhong Plain (China) using grey Markov model. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, L.; Lei, K.; Huang, J.; Zhai, Y. Contamination assessment of copper, lead, zinc, manganese and nickel in street dust of Baoji, NW China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.L.; Song, H.L.; Zhu, C.C.; Zhang, B.B.; Zhang, M. Spatio-temporal evolution of drought and flood disaster chains in Baoji area from 1368 to 1911. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, C.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, J. Inventory and Distribution Characteristics of Large-Scale Landslides in Baoji City, Shaanxi Province, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Y.; Qian, H.; Huo, C.C.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.K. Assessing natural background levels in shallow groundwater in a large semiarid drainage Basin. J. Hydrol. 2020, 584, 124638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.P.; Feng, W.W.; Qian, H.; Zhang, Q.Y. Hydrogeochemical Characterization and Irrigation Quality Assessment of Shallow Groundwater in the Central-Western Guanzhong Basin, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, H.; Zhang, B.T.; Kong, H.M.; Li, M.X.; Wang, W.; Xi, B.D.; Wang, G.Q. Comprehensive assessment of groundwater pollution risk based on HVF model: A case study in Jilin City of northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Kafle, R.; Pandey, V.P. Evaluation of index-overlay methods for groundwater vulnerability and risk assessment in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, M.; Jia, L. Geographical detection of groundwater pollution vulnerability and hazard in karst areas of Guangxi Province, China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, L.; Bennett, T.; Lehr, J.; Petty, R.; Hackett, G. Drastic: A Standardized System for Evaluating Ground Water Pollution Potential Using Hydrogeologic Settings; EPA/60012-87/035; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; Volume 455.

- Zhang, J.J.; Zhai, Y.Z.; Xue, P.W.; Huan, H.; Zhao, X.B.; Teng, Y.G.; Wang, J.S. A GIS-based LVF model for semiquantitative assessment of groundwater pollution risk: A case study in Shenyang, NE China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2017, 23, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, J.; Sun, A.; Zhong, X. Inadequacies of DRASTIC model and discussion of improvement. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2010, 37, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Khalid, P.; Ehsan, M.I.; Qureshi, J.; Farooq, S. Evaluation of aquifer parameters through integrated approach of geophysical investigations, pumping test analysis and Dar-Zarrouk parameters in the central part of Bari Doab, Punjab, Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuit, J.É.J. Études Théoriques et Pratiques sur le Mouvement des Eaux Dans les Canaux Découverts et à Travers les Terrains Perméables: Avec des Considérations Relatives au Régime des Grandes Eaux, au Débouché à Leur Donner, et à la Marche des Alluvions Dans les Rivières à Fond Mobile; Dunod Éditeur: Paris, France, 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.X.; Li, P.Y.; Lyu, Q.F.; Ren, X.F.; He, S. Groundwater contamination risk assessment using a modified DRATICL model and pollution loading: A case study in the Guanzhong Basin of China. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Rong, S.; Xiong, Y.; Teng, Y. Groundwater Vulnerability and Groundwater Contamination Risk in Karst Area of Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huan, H.; Li, H.X.; Liu, W.J.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.B.; Zhou, A.X.; Xie, X.J. Quantitative Assessment and Validation of Groundwater Pollution Risk in Southwest Karst Area. Expo. Health 2025, 17, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Integrated Risk Information System. 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/iris (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- US EPA. Health Effects Assessment Summary Tables (Heast); US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- GB/T 14848-17; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Quality Standard for Groundwater. Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision of China: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese)

- Bian, J.H.; Khan, T.A.; Li, A.N.; Zhao, J.P.; Deng, Y.; Lei, G.B.; Zhang, Z.J.; Nan, X.; Naboureh, A.; Khan, M.U. A new spatiotemporal fusion model for integrating VIIRS and SDGSAT-1 Nighttime light data to generate daily SDGSAT-1 like observations. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2472912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, C.; Martin, D.A.; Vargas, J.F. Measuring the size and growth of cities using nighttime light. J. Urban Econ. 2021, 125, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.M.; Seto, K.C.; Zhou, Y.Y.; You, S.X.; Weng, Q.H. Nighttime light remote sensing for urban applications: Progress, challenges, and prospects. ISPRS-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 202, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruederle, A.; Hodler, R. Nighttime lights as a proxy for human development at the local level. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, L.-q.; Cheng, Y.-p.; Yi, Q.; Wen, X.-r.; Dong, H.; Liu, K.; Zhang, J.-k. Research on groundwater ecological environment mapping based on ecological service function: A case study of five Central Asian countries and neighboring regions of China. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xiao, Y.Z.; Ding, G.C.; Liao, L.Y.; Yan, C.; Liu, Q.Y.; Gao, Y.L.; Xie, X.C. Comprehensive Evaluation of Island Habitat Quality Based on the Invest Model and Terrain Diversity: A Case Study of Haitan Island, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shao, H.Y.; Lim, H. Analysis of Water Conservation Mechanisms in the River Source Area of Northwest Sichuan from the Perspective of Vegetation Cover Zoning. Water 2025, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüke, A.; Hack, J. Comparing the Applicability of Commonly Used Hydrological Ecosystem Services Models for Integrated Decision-Support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, Y.Y.; Zhou, J.L.; Yan, Z.Y.; Bai, F. Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment in Plain Area of Barkol-Yiwu Basin. Environ. Sci. 2023, 44, 6778–6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patoni, K.; Esteller, M.V.; Expósito, J.L.; Fonseca, R.M.G. Spatial design of groundwater quality monitoring network using multicriteria analysis based on pollution risk map. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorol, L.; Gupta, S.K. Evaluation of groundwater heavy metal pollution index through analytical hierarchy process and its health risk assessment via Monte Carlo simulation. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2023, 170, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, P.; Fabbri, A. Single-parameter sensitivity analysis for aquifer vulnerability assessment using DRASTIC and SINTACS. IAHS Publ.-Ser. Proc. Rep.-Intern Assoc Hydrol. Sci. 1996, 235, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.J.; Ma, C.M.; Huang, P.; Guo, X. Ecological vulnerability assessment based on AHP-PSR method and analysis of its single parameter sensitivity and spatial autocorrelation for ecological protection ? A case of Weifang City, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, E.; Conicelli, B.; Moulatlet, G.M.; Hirata, R. Comparative analysis of EPIK, DRASTIC, and DRASTIC-LUC methods for groundwater vulnerability assessment in karst aquifers of the Western Amazon Basin. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Wu, H.; Qian, H. Groundwater contamination risk assessment using intrinsic vulnerability, pollution loading and groundwater value: A case study in Yinchuan plain, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 45591–45604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.J.; Yu, X.P.; Zhang, W.J.; Huan, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y. Risk Assessment of Groundwater Organic Pollution Using Hazard, Intrinsic Vulnerability, and Groundwater Value, Suzhou City in China. Expo. Health 2018, 10, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, K.; Amin, D. Vulnerability of groundwater quantity for an arid coastal aquifer under the climate change and extensive exploitation. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Weight | Indicator | Weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groundwater pollution risk index RI | Groundwater vulnerability index DI | 0.580 | Pore/fissure groundwater vulnerability index DI1 | D | 0.267 |

| R | 0.165 | ||||

| S | 0.061 | ||||

| T | 0.040 | ||||

| I | 0.267 | ||||

| C | 0.100 | ||||

| W | 0.100 | ||||

| Karst groundwater vulnerability index DI2 | P | 0.361 | |||

| L | 0.253 | ||||

| E | 0.177 | ||||

| I | 0.123 | ||||

| K | 0.086 | ||||

| Groundwater pollution load index PI | 0.240 | Groundwater pollution load index PI | Industrial pollution source | 0.392 | |

| Landfill site | 0.248 | ||||

| Gas station | 0.237 | ||||

| Agricultural pollution source | 0.123 | ||||

| Groundwater value function index FI | 0.190 | Groundwater value function index FI | Q | 0.320 | |

| H | 0.270 | ||||

| E | 0.410 | ||||

| Pore/Fissure Groundwater Vulnerability Index (DI1) | Karst Groundwater Vulnerability Index (DI2) | Groundwater Pollution Load Index (PI) | Groundwater Value Function Index (FI) | Groundwater Pollution Risk Index (RI) | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.96–3.43 | - | 0.00–2.27 | 1–1.41 | 0.31–2.71 | Low |

| 3.43–4.32 | - | 2.27–4.44 | 1.41–1.91 | 2.71–4.10 | Relatively low |

| 4.32–5.15 | 4.00–6.00 | 4.44–6.92 | 1.91–2.27 | 4.10–5.50 | Medium |

| 5.15–6.09 | 6.00–8.00 | 6.92–10.21 | 2.27–2.64 | 5.50–6.91 | Relatively high |

| 6.09–7.60 | - | 10.21–16.81 | 2.64–3.13 | 6.91–8.62 | High |

| Indicators | Theoretical Weight (%) | Effective Weights (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Standard Deviation | |||

| DI1 | D | 26.7 | 24.4 | 4.9 | 54.6 | 12.0 |

| R | 16.5 | 23.5 | 10.4 | 48.8 | 8.6 | |

| S | 6.1 | 7.1 | 4.5 | 15.6 | 1.6 | |

| T | 4.0 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 15.1 | 2.2 | |

| I | 26.7 | 20.9 | 11.2 | 38.2 | 5.6 | |

| C | 10.0 | 7.4 | 1.9 | 18.8 | 3.3 | |

| W | 10.0 | 11.1 | 1.4 | 13.3 | 4.6 | |

| DI2 | P | 36.1 | 42.2 | 36.9 | 56.9 | 8.3 |

| L | 25.3 | 22.6 | 5.6 | 39.4 | 13.1 | |

| E | 17.7 | 14.1 | 7.8 | 16.8 | 1.8 | |

| I | 12.3 | 12.7 | 7.7 | 15.7 | 2.8 | |

| K | 8.6 | 8.4 | 5.2 | 11.3 | 1.7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Z.; Chen, J.; Pang, J.; Li, T.; Ren, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zou, J. Shallow Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment in the Plain Area of Baoji City, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411213

Jia Z, Chen J, Pang J, Li T, Ren Y, Liu H, Zhang L, Zhang T, Zou J. Shallow Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment in the Plain Area of Baoji City, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411213

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Zhifeng, Jia Chen, Jialu Pang, Ting Li, Yuze Ren, Hao Liu, Linhui Zhang, Tianhao Zhang, and Jie Zou. 2025. "Shallow Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment in the Plain Area of Baoji City, China" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411213

APA StyleJia, Z., Chen, J., Pang, J., Li, T., Ren, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, L., Zhang, T., & Zou, J. (2025). Shallow Groundwater Pollution Risk Assessment in the Plain Area of Baoji City, China. Sustainability, 17(24), 11213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411213