Abstract

Coastal ecosystems are among the most biodiverse and economically valuable environments on Earth, yet they face escalating threats from climate change, development, and resource exploitation. Traditional conservation approaches have proven insufficient to address the systemic drivers of biodiversity loss, calling for transformative change that fundamentally reconfigures social–ecological systems. This semi-structured systematic literature review synthesizes current knowledge on transformative change in coastal biodiversity conservation, guided by the Social–Ecological Systems Framework (SESF) and expanded to include behavioral transformation as a central dimension. Behavioral transformation is defined as the sustained embedding of new attitudes, norms, and practices within governance, institutional, and community settings. Through a comprehensive review of academic databases (SCOPUS, Web of Science, CAB Abstracts) and gray literature, 134 studies published between 2010 and 2024 were analyzed. The synthesis identifies four interdependent pathways of transformation: (1) governance innovation and power redistribution, (2) behavioral change and stakeholder engagement, (3) socio-ecological restructuring, and (4) normative and cultural shifts in human–nature relations. Successful initiatives integrate trust-building, social justice, and participatory decision-making, linking behavioral change with institutional redesign and adaptive management. However, critical gaps remain in understanding long-term durability, equity outcomes, and scalability across governance levels. The review proposes three research priorities: (1) embedding behavioral science in conservation design, (2) employing longitudinal and cross-scale analyses, and (3) advancing adaptive, learning-based governance to enhance socio-ecological resilience.

1. Introduction

The global biodiversity crisis has reached unprecedented levels, with extinction rates now estimated to be 100 to 1000 times higher than natural background rates [1,2,3]. Coastal ecosystems are at the forefront of this crisis. They support approximately 40% of the world’s population and contribute over $28 trillion annually to the global economy [4]. They face converging threats such as sea-level rise, ocean acidification, coastal development, pollution, overexploitation of resources, and increasing catastrophic events such as fires, floods, and hurricane winds [5]. Without immediate and transformative action, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that biodiversity loss in these environments will accelerate dramatically, undermining ecosystem services, food security, and human well-being [6].

Traditional conservation measures—such as protected areas, species-specific management, and incremental policy adjustments—have shown limited effectiveness against the systemic drivers of biodiversity decline [7]. Despite decades of conservation, biodiversity loss continues to accelerate, highlighting the need for approaches that address the broader social–ecological systems within which coastal ecosystems exist [8].

Transformative change has emerged as a central concept for halting biodiversity loss. It is defined as a profound, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic, and social dimensions, including paradigms, goals, and values [8,9]. Biodiversity forms the foundation of resilient ecosystems vital for human and non-human well-being [10]. Yet incremental efforts remain insufficient in the face of what has been termed the “sixth extinction wave” [11]. Scholars increasingly call for system-wide shifts in conservation, especially in the Anthropocene [12,13]. However, the concept challenges traditional conservation paradigms that prioritize ecological stability over adaptive transformation [14,15].

Coastal ecosystems, situated at the land–sea interface, are uniquely positioned to benefit from transformative approaches. They are marked by high ecological connectivity, rapid environmental change, and strong human pressures, making them both vulnerable and potentially responsive. Importantly, coastal communities often possess rich cultural connections and traditional ecological knowledge, which can contribute to innovative, place-based conservation strategies [16,17].

Although the need for transformative change is widely acknowledged, the literature on its application in coastal conservation remains fragmented. Existing reviews often focus on terrestrial systems or address transformation only in general terms [18,19,20]. This gap is significant, given the distinct governance challenges, stakeholder dynamics, and ecological complexities that characterize coastal ecosystems.

This paper explores how transformative change is being operationalized in coastal biodiversity conservation. It seeks to synthesize fragmented knowledge, identify critical success factors and barriers, and provide a framework for guiding future interventions. Behavioral transformation is defined as the sustained shift in attitudes, behaviors and practices of individuals, groups or organizations, leading them to adopt new routines, values and modes of operating, which transcend incremental change and support systemic goals [21,22]. This emphasizes that transformation is not simply “doing more of the same” but involves a fundamental reorientation of behavior, culture and governance. Thus, the paper pays particular attention to the potential of the Social–Ecological Systems (SES) Framework [23,24] to structure, monitor, and evaluate transformative initiatives.

The review is guided by three primary questions:

RQ1: What are the key characteristics, mechanisms, and intervention strategies through which behavioral transformation initiatives drive shifts in governance structures, stakeholder participation, and socio-ecological practices in coastal biodiversity conservation?

RQ2: Which social, institutional, and behavioral factors enable or constrain the successful implementation, adoption, and long-term sustainability of transformative initiatives in coastal socio-ecological systems?

RQ3: How can the Social–Ecological Systems (SES) Framework be expanded to integrate behavioral dynamics—such as learning, trust, and norm change—into the design, monitoring, and evaluation of transformative conservation interventions across local, regional, and global scales?

By addressing these research questions, this paper seeks to provide the first comprehensive synthesis of how behavioral transformation is being approached in coastal biodiversity conservation. It develops a typology of transformative strategies that are specifically tailored to the unique characteristics of coastal ecosystems and identifies the critical factors that enable or hinder their success. In addition, the paper evaluates the Social–Ecological Systems (SES) Framework as a practical tool for guiding the design, scaling, and assessment of transformative interventions. Through this work, the paper contributes to both research and practice by offering actionable insights that can support policymakers, practitioners, and local communities in their efforts to halt biodiversity loss and foster more resilient coastal futures.

2. Method

In this paper, designed as a semi-structured literature review following guidelines of Bryman [25] and of Supplementary Materials: PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), we explore the utilization of transformative and behavioral change as interdependent processes, following Nienaber’s integration strategy, which conceptualizes behavioral transformation as the sustained embedding of new attitudes, routines, and practices within broader organizational, cultural, and governance structures to support systemic sustainability transitions. Recognizing the urgent need for innovative solutions in the face of unprecedented threats to coastal ecosystems, we delve into existing literature on conservation strategies between the years 2010 and 2024. We registered the project in the OSF database. Our review examines how transformative change has been employed to counteract the decline of coastal biodiversity, identifying and analyzing various approaches, policy frameworks, and innovative strategies that have shown efficacy in fostering positive outcomes for coastal ecosystems.

To gather relevant literature, we utilized keywords such as “Transformative Change,” “Coastal Biodiversity,” “Conservation Strategies,” “Ecosystem Restoration,” “Innovative Approaches,” and “Halt Biodiversity Loss” across multiple databases, including SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Through this search, applying the combination of “Biodiversity AND loss AND (sustainable OR sustainability) AND (transformation OR change),” we identified a total of more than 300 papers. After implementing our exclusion criteria, which included selecting papers with comparable definitions of transformation, focusing on coastal areas, and excluding those that solely presented practical case reports, we arrived at a final sample of 82 papers. A full list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided below.

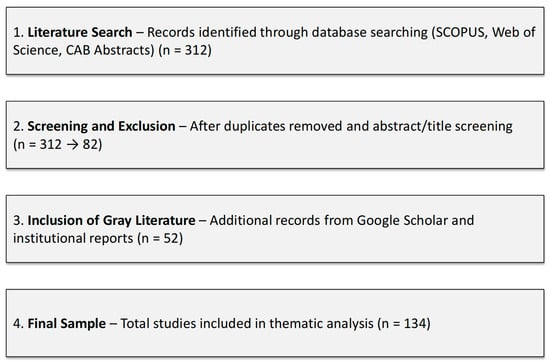

To ensure the inclusion of gray literature, we conducted a search on Google Scholar using the same keyword combination as utilized in SCOPUS, CAB Abstracts, and Web of Science. We meticulously examined the first 150 search results on Google Scholar, as beyond this point, the relevance and quality of the papers diminished significantly. This thorough search process resulted in a final sample of 134 papers. By employing this comprehensive approach, we aimed to capture a diverse array of studies from both ecological and social science disciplines, thus facilitating a thorough exploration of the topic at hand. An overview can be found in the following Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-aligned study selection process.

Applying a semi-systematic or narrative review approach, our focus was on understanding the progression of research within the selected field until March 2024 and identifying relevant research traditions that inform the studied topic. We collected data in the form of descriptive information, such as authors, years published, topic, or type of study, or in the form of effects and findings—beside the form of conceptualizations of a certain idea or theoretical perspective. Importantly, we put huge emphasis on aligning this data gathering with the purpose and research question of this review. Two independent researchers were involved in the procedure to identify and analyze the final sample of papers. We used the following inclusion and exclusion criteria in the selection process. All inclusion and exclusion decisions were documented in a shared review matrix, providing a transparent record of how each study met the selection criteria.

Inclusion Criteria:

- Studies examining transformative change, behavioral change or transformation, or fundamental system change in the context of biodiversity conservation;

- Focus on coastal, marine, or estuarine ecosystems (including studies that address coastal-terrestrial interfaces);

- Empirical studies (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods), theoretical papers, or review articles that contribute to understanding transformative change processes;

- Published in peer-reviewed journals or as gray literature from reputable organizations (e.g., Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES));

- Available in English language.

Exclusion Criteria:

- Studies focusing solely on terrestrial ecosystems without coastal components;

- Studies addressing only incremental or adaptive changes without transformative elements;

- Opinion pieces, editorials, or commentary articles without substantial analytical content;

- Studies focusing exclusively on technological innovations without broader system change considerations;

- Conference abstracts without full-text availability;

- Studies published before 2010 (to focus on contemporary transformative change discourse).

This approach allowed us to synthesize diverse perspectives and methodologies, providing a nuanced understanding of the complexities surrounding transformative change in biodiversity conservation. Utilizing thematic analysis, we identified, analyzed, and reported patterns within the literature, discerning key themes and theoretical perspectives. This method enabled us to map the field of research, synthesize the state of knowledge, and identify gaps for further exploration. Additionally, thematic analysis facilitated the creation of an agenda for future research [25], guiding the development of evidence-based strategies for coastal biodiversity conservation. During the thematic analysis, a structured coding framework was developed to capture recurrent patterns across four dimensions of transformative change—governance innovation, socio-ecological restructuring, behavioral transformation, and paradigmatic shifts. The coding framework was both deductive and inductive: initial categories were derived from established theoretical frameworks [9,22,23], while additional codes emerged inductively through iterative reading and researcher discussion. Each article was coded for (1) contextual information (geographical scope, ecosystem type, governance level), (2) intervention type and mechanisms, (3) behavioral indicators (trust, motivation, participation, learning, and routine change), and (4) outcomes or impacts.

To enhance reliability, two independent coders reviewed the material using an iterative consensus-building process. Both researchers initially coded a subset of 20 articles to test the framework, compared interpretations, and refined coding categories through discussion until full alignment was achieved. The finalized scheme was then applied to the complete sample of 134 studies. Inter-coder agreement exceeded 85%, ensuring consistent identification of themes across the four analytical dimensions—governance innovation, socio-ecological restructuring, behavioral transformation, and paradigmatic shifts. This coding framework provided a robust foundation for synthesizing conceptual linkages between governance structures, behavioral mechanisms, and socio-ecological outcomes.

Overall, our semi-structured literature review contributes valuable insights to the broader discourse on biodiversity conservation and sustainable coastal management. By synthesizing diverse perspectives and methodologies, we provide a comprehensive overview of transformative change in biodiversity conservation, laying the groundwork for future research and practice in this critical field.

3. Key Findings from the Literature Review on Transformative Change

The findings of this structured literature review are presented in line with the three guiding research questions. The literature review develops a taxonomy of objectives to categorize how different studies conceptualize and operationalize transformative change in coastal conservation.

3.1. Publication Patterns and Research Evolution

Our analysis of 134 studies reveals a notable increase in scholarship on transformative change in biodiversity conservation, with the majority of publications emerging after 2015. This timing coincides with broader scientific and policy debates about the Anthropocene, planetary boundaries, and the inadequacy of incremental conservation strategies [9,26,27]. The surge in publications also reflects growing recognition of coastal ecosystems as critical social–ecological systems, given their ecological richness and socioeconomic significance [4,6].

However, the literature remains uneven. While terrestrial systems dominate the discourse, coastal ecosystems are often addressed only tangentially or as case applications of broader theories [11,18]. Fragmentation across disciplines is also evident: ecological studies tend to focus on biophysical resilience and restoration, whereas social sciences emphasize governance, participation, and justice [15,28]. This siloed knowledge limits integrative understanding.

Our synthesis indicates that behavioral transformation manifests along three interconnected pathways: (a) governance innovation, (b) socio-ecological restructuring, and (c) paradigmatic shifts in human–nature relationships. Behavioral change operates both as a catalyst and as an outcome within these pathways—driving and reflecting deeper shifts in norms, values, and practices. In this sense, behavioral transformation does not occur in isolation but emerges through iterative interactions between institutional redesign, ecological adaptation, and cultural reorientation. These intertwined dynamics mirror the principles of complex adaptive systems, which emphasize feedbacks, non-linearity, and emergence [29,30,31].

3.2. RQ1: Characteristics, Approaches, and Mechanisms of Transformative Change

3.2.1. Governance Innovation

The most widely documented pathway involves governance innovation, which inherently interacts with processes of behavioral transformation. Three recurring dimensions were identified:

Institutional redesign—The creation of new organizations or mechanisms that cross sectoral boundaries and facilitate integrated management of coastal zones. Examples include cross-jurisdictional marine spatial planning bodies, ecosystem-based management institutions, and collaborative governance platforms [32,33]. Yet, effectiveness varies. Institutional redesign is more likely to succeed when embedded in supportive political and economic contexts and when it simultaneously fosters new behavioral norms and routines of cooperation among actors.

Power redistribution—Transformative change requires more than new institutions; it also depends on shifts in authority. Successful initiatives often involve empowering marginalized stakeholders—such as indigenous groups and small-scale fishers—granting them decision-making roles in defining priorities, allocating resources, and designing conservation strategies [15,34]. This redistribution of power not only alters institutional arrangements but also triggers behavioral transformation by redefining trust, accountability, and the perceived legitimacy of governance processes [22].

Decision-making transformation—Processes move away from top-down, technocratic models toward adaptive, polycentric, and participatory modes. This includes iterative decision-making, local deliberation, and multilevel governance networks that can respond flexibly to dynamic coastal pressures [35]. Such participatory processes encourage behavioral shifts among stakeholders, enhancing collaboration, shared learning, and collective responsibility, which are essential for sustaining systemic transformation across governance levels [22].

Empirical evidence supports these dynamics. In Latin America, Aguiar and colleagues demonstrate that forest and landscape restoration initiatives succeeded when governance innovation was paired with behavioral engagement—local communities co-designed restoration strategies, internalizing new cooperative norms and shared accountability structures [36]. Conversely, in Pakistan’s Swat Valley, Bacha and colleagues [37] show that despite strong climate awareness, the absence of participatory governance and trust hindered behavioral adaptation. Operationalizing this, the PRO-CLIMATE project introduces the role of designated ‘Change Agents’—local citizens trained to act as intermediaries. This mechanism shifts governance from a top-down consultation to a peer-to-peer mobilization model, effectively redistributing the power to initiate climate action. Together, these studies highlight that governance innovation becomes truly transformative only when it simultaneously fosters behavioral change and trust-based participation.

3.2.2. Socio-Ecological Restructuring

The second pathway entails reconfiguring the material and ecological foundations of coastal systems. This takes three primary forms:

Ecosystem restoration—Traditional restoration efforts aimed at returning ecosystems to historical baselines often deliver limited transformation [11]. By contrast, “transformative restoration” explicitly embraces novel ecosystems designed for future resilience under climate change while also providing socio-economic benefits [6,7].

The case study focuses on Norway’s west coast, within the wider Bergen region, a rugged coastline of rocky shores, shallow bays, fjords, and scattered islands that support diverse marine habitats. A major ecological challenge in this area is the presence of lost fishing gear, particularly abandoned crab and lobster pots, which continue to trap marine life and contribute to ghost fishing. Locating and removing this gear is difficult, yet essential. The region is also shaped by allemannsretten, Norway’s tradition of public access to nature, which reinforces the cultural importance of sea-based recreation, including leisure fishing. Economically, the west coast is home to a strong fisheries and aquaculture sector, alongside a variety of maritime and urban industries. Governance structures include marine protected areas and seasonal fishing regulations designed to protect vulnerable species and fish stocks.

Within this context, the PRO-COAST initiative (PRO-COAST: www.pro-coast.eu, accessed on 24 September 2025). works with Norgesmiljøforbund (NMF) to complement government fisheries policies. The project focuses on two main actions: (1) raising awareness of ghost fishing by promoting prevention, clean-ups, and reporting of lost gear among environmental NGOs, funders, leisure fishers, and public authorities; and (2) conducting large-scale removal of ghost gear along the west coast and developing a best-practice manual to guide future efforts. This socio-ecological restructuring initiative primarily addresses fish stock depletion, but it also links to broader biodiversity and climate concerns [38].

Alternative economic models—Case studies highlight community-driven fisheries management, ecotourism initiatives, and blue economy innovations that align economic incentives with biodiversity outcomes [1,20].

Nature-based solutions—Initiatives such as mangrove rehabilitation and wetland buffers provide dual benefits: enhancing biodiversity while protecting communities from flooding and sea-level rise. These solutions illustrate how ecological restructuring can simultaneously deliver social and ecological resilience [e.g., City of Gdanks SCORE project: www.score-eu-project.eu (accessed on 24 September 2025) or PRO-CLIMATE: www.pro-climate.eu (accessed on 24 January 2025)].

In the PRO-CLIMATE Living Lab in the City of Gdańsk, nature-based adaptation was intentionally coupled with social learning and community engagement. Local residents, schools, and policymakers co-designed green infrastructure interventions aimed at reducing urban flooding, creating not only ecological benefits but also a collective sense of responsibility and new behavioral norms around water use and local stewardship. While the preceding SCORE project had focused on the more “hard” restructuring of flood-mitigation zones, PRO-CLIMATE concentrated on the “soft” restructuring of community norms and practices. Similarly, in the Gdańsk SCORE project, coastal areas were restored through participatory design workshops in which community input directly shaped the layout and monitoring of flood-mitigation zones. Together, these examples demonstrate that successful nature-based solutions depend not only on ecological and technical design but also on behavioral transformation rooted in trust, participation, and shared ownership.

Paradigmatic Shifts in Human–Nature Relationships—The third pathway concerns deeper cultural, normative, and behavioral change. Several studies document a move from anthropocentric conservation approaches toward ecocentric perspectives that recognize the intrinsic rights of ecosystems [14,15]. Examples include granting legal personhood to rivers or marine areas, recognition of indigenous ecological knowledge, and grassroots social movements advocating radical alternatives to growth-oriented paradigms [28,39]. Such paradigmatic shifts are not merely ideological but are reflected in behavioral transformation -in the ways individuals, communities, and institutions internalize and enact new value systems. As [21,22,31] emphasize, behavioral transformation occurs when these normative changes become embedded in social practices, organizational routines, and decision-making cultures, thereby reinforcing trust, shared responsibility, and collective action. In coastal conservation, this interplay between cultural meaning and behavioral adaptation is central to building resilient, future-oriented governance systems that align ecological ethics with everyday human behavior.

Although difficult to measure, paradigmatic shifts are crucial because they underpin governance and ecological restructuring. Without changes in values, behaviors, and social norms, institutional and ecological reforms risk being superficial or temporary.

3.3. RQ2: Enabling and Constraining Factors

3.3.1. Enabling Factors

Leadership—Visionary, inclusive, and context-sensitive leadership emerged as the single most critical enabler. Leaders who can inspire collective vision, navigate political complexity, and respect local knowledge are more likely to catalyze transformation [35,39]. From a behavioral transformation perspective, effective leadership also models new norms and practices, creating the psychological safety and shared motivation necessary for stakeholders to adopt and sustain new behaviors [31,40].

Social capital and trust—Strong relational networks, reciprocity, and trust across stakeholder groups foster collaboration, reduce conflict, and enable collective problem-solving [29,30]. Trust plays a pivotal role in behavioral transformation, functioning as both a precondition and an outcome of participatory processes [31]. As Nienaber and colleagues argue, trust facilitates openness to behavioral change by lowering perceived risks, enhancing legitimacy, and enabling social learning.

Knowledge integration—Combining scientific research with traditional ecological knowledge enhances legitimacy and local buy-in [33,41]. Beyond epistemic integration, this process supports behavioral learning, encouraging mutual adaptation among scientists, policymakers, and communities as they co-create actionable knowledge for sustainable practice [21,22,31].

Empirical studies support these findings. In Latin America, Aguiar and colleagues document how participatory governance structures fostered behavioral change among rural stakeholders, aligning ecological restoration goals with livelihood practices. Conversely, in Swat Valley, Pakistan [37], limited institutional trust and education hindered the translation of climate awareness into behavioral adaptation. These contrasting cases illustrate that enabling behavioral transformation requires both institutional redesign and strong relational infrastructure.

3.3.2. Constraining Factors

Institutional inertia—Formal rules, bureaucratic processes, and entrenched norms often resist change. Inertia manifests both in ecological management (rigid restoration baselines) and governance (sectoral silos) [42]. From a behavioral transformation perspective, such inertia also reflects deeply embedded routines and cognitive resistance to change, where established habits, organizational cultures, and power dependencies discourage experimentation and innovation [22].

Vested interests—Economic and political elites frequently oppose transformative reforms that threaten established resource use patterns, especially in fisheries, tourism, and coastal development [43].

Fragmentation—Limited cross-sectoral coordination hampers transformative initiatives, leading to piecemeal interventions with limited system-wide impact [11]. Behaviorally, fragmentation erodes trust and weakens shared purpose among stakeholders, making it more difficult to align values, incentives, and actions across governance levels, a dynamic that Nienaber and colleagues identifies as critical to overcoming behavioral barriers to systemic change.

3.4. RQ3: The Utility and Limits of the Social–Ecological Systems (SES) Framework

The SES Framework [24,44] provides a valuable tool for structuring the analysis of transformation by identifying action situations, actor interactions, and feedback across ecological and social domains. It helps trace leverage points for systemic change and highlights interdependencies.

Yet, the framework also has limitations. First, it tends to underemphasize power dynamics, equity concerns, and historical legacies of exclusion [15,45]. Moreover, the SES Framework has been critiqued for insufficiently addressing the behavioral dimension of transformation, that is, how individuals and groups change their attitudes, routines, and interactions within evolving social–ecological contexts. As Nienaber and colleagues [22,31] emphasize, behavioral transformation is both a driver and a reflection of systemic change: it occurs when trust, motivation, and shared learning are intentionally embedded in institutional processes. Integrating this behavioral perspective enhances the SES Framework’s capacity to capture agency, relational dynamics, and the micro-level mechanisms through which macro-level transformation emerges.

Scholars increasingly argue that SES analysis must therefore be complemented with critical social science and behavioral perspectives to fully capture the justice, equity, and agency dimensions of transformative change [22,28].

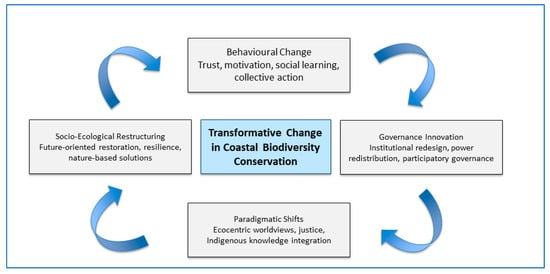

4. Synthesis: Towards a Complex Understanding of Transformation in Coastal Conservation

This review demonstrates that transformative change in coastal biodiversity conservation is neither a single intervention nor a linear process. Rather, it unfolds as a multidimensional and dynamic phenomenon shaped by the interplay of governance innovation, behavioral transformation, socio-ecological restructuring, and paradigmatic shifts in human–nature relations. While each pathway operates through distinct mechanisms, evidence across 134 studies highlights that isolated actions within any one domain rarely achieve lasting transformation. The most effective initiatives integrate institutional redesign, ecological reconfiguration, behavioral adoption, and cultural value change in mutually reinforcing ways.

At the governance level, this article demonstrates that institutional restructuring must be coupled with a redistribution of power to move beyond purely symbolic participation. This has important implications for practice: environmental protection cannot be treated as a purely technical or managerial endeavor but must be recognized as a deeply political process in which authority, legitimacy, and trust are continuously negotiated [15,22]. Transformative governance therefore demands an explicit focus on inclusion, deliberation, and empowerment of marginalized actors—particularly coastal communities, Indigenous peoples, and local resource users—whose knowledge, rights, and practices are often overlooked.

From a behavioral perspective, transformation involves the reconfiguration of individual and collective practices, motivations, and norms that underpin sustainable action. Behavioral change is not merely an outcome of governance or ecological restructuring but a core mechanism through which transformation becomes socially embedded and durable. Drawing on Nienaber’s [21,22,31] integration strategy and social–psychological theory (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior) [46], behavioral transformation can be understood as the sustained adoption of new routines, trust-based collaboration, and reflexive learning that align with long-term ecological and social objectives. Evidence from coastal initiatives demonstrates that participatory education, peer modeling, and collective sense-making enable communities to replace extractive or reactive behaviors with stewardship practices that reinforce resilience [21,22,35]. Importantly, these behavioral mechanisms operate across scales—linking personal commitment with institutional accountability—and act as both drivers and outcomes of systemic change.

From a socio-ecological perspective, restructuring efforts reveal that restoration practices anchored too rigidly in historical baselines can inadvertently perpetuate system fragility. Transformative approaches, by contrast, emphasize future-oriented resilience, integrating climate adaptation, ecosystem services, and socio-economic benefits [6]. Such approaches require flexible, iterative management systems that embrace uncertainty, support learning-by-doing, and link local restoration efforts with larger-scale ocean and climate governance frameworks. This implies shifting conservation planning from static preservation models toward dynamic, adaptive systems capable of evolving alongside ecological and behavioral change.

Finally, paradigmatic shifts—though difficult to measure—provide the normative foundation for both governance and ecological restructuring. They signal that sustainable futures depend on cultural transformations toward ecocentric worldviews, ecological justice, and recognition of Indigenous and local knowledge systems [28,39]. These shifts reframe conservation not as “saving nature from people,” but as fostering coexistence, reciprocity, and care within human–nature relationships.

Together (see Figure 2), these insights challenge dominant narratives that treat transformation as a staged or sequential process and instead support perspectives grounded in complex adaptive systems that emphasize feedbacks, uncertainty, and non-linearity [29,30].

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of transformative and behavioral pathways.

From a research perspective, the synthesis highlights four key contributions of this review:

- Integration across fragmented literature—By mapping governance, ecological, and normative pathways together, the review provides the first comprehensive synthesis of how transformation is operationalized in coastal conservation, offering a typology that connects ecological sciences, political ecology, and social sciences.

- Identification of enabling and constraining dynamics—The review reveals consistent patterns of enablers (leadership, social capital, knowledge integration) and barriers (institutional inertia, vested interests, fragmentation) that operate across scales. This contributes a theoretically grounded framework for analyzing conditions under which transformation succeeds or fails.

- Recognition of behavioral transformation as a systemic process—Behavioral change emerges as both an enabler and an outcome of transformative conservation, linking structural reforms with shifts in values, attitudes, and everyday practices [22,40].

- Critical engagement with frameworks—While the Social–Ecological Systems Framework offers analytical structure, the review shows its blind spots regarding politics, power, and justice. This invites future research to hybridize SES with critical governance and justice perspectives, thereby strengthening its capacity as a tool for transformative practice.

4.1. Implications for Practice

The implications for practice are equally significant. The findings underscore that achieving transformative change in coastal conservation requires systemic realignment across governance structures, management strategies, and cultural foundations.

- Repoliticizing Conservation Practice

- Conservation professionals must recognize that technical interventions (such as marine zoning, protected area designation, or ecosystem restoration) are inherently political acts that shape access, rights, and responsibilities.

- Practitioners should adopt reflexive approaches that explicitly confront issues of power, representation, and legitimacy in decision-making.

- Building equitable partnerships with local and Indigenous communities is essential—not through consultative tokenism but through genuine co-management, shared decision-making, and redistribution of authority.

- Embedding Justice, Equity, and Behavioral Transformation in Governance

- Policies should embed social justice and behavioral inclusion as core criteria for success, ensuring that the costs and benefits of conservation are distributed fairly across social groups. Embedding behavioral principles—such as transparency, reciprocity, and shared responsibility -can strengthen trust between institutions and communities [40,47].

- Mechanisms such as community-led monitoring, participatory budgeting, and co-design of management plans not only institutionalize equity but also encourage collective behavioral change by fostering ownership, legitimacy, and long-term engagement. These participatory processes translate abstract equity goals into everyday practices of cooperation and shared governance.

- Capacity-building programs should strengthen both structural and behavioral agency among historically marginalized groups, enhancing their ability to shape conservation priorities and decision-making. Empowering communities in this way promotes self-efficacy, a key behavioral condition for sustained engagement and transformation.

- Adopting Future-Oriented Restoration Practices

- Restoration must move beyond recreating historical ecosystems toward designing resilient futures that integrate human well-being with ecological integrity.

- Nature-based solutions—such as mangrove rehabilitation, living shorelines, and blue carbon initiatives—should be implemented as adaptive, multifunctional systems that deliver both ecological and social benefits.

- Long-term monitoring frameworks should be established to track adaptive outcomes and learn from ecological feedbacks, rather than measuring success solely against fixed benchmarks.

- Institutionalizing Learning, Adaptation, and Behavioral Transformation

- Transformation requires iterative learning processes embedded in governance, where experimentation, feedback, and reflexivity are normalized as part of everyday practice. Embedding behavioral learning loops—through reflection, adaptation, and mutual accountability—enables institutions and stakeholders to internalize change and sustain it over time [22].

- Cross-sectoral collaboration among scientists, policymakers, communities, and NGOs fosters collective behavioral intelligence, reducing policy fragmentation and strengthening the social infrastructure for transformation. This collaboration encourages openness, empathy, and perspective-taking—key behavioral enablers of systemic learning.

- Practitioners should cultivate “transformative leadership” that models behavioral flexibility, builds trust, and encourages innovation rather than rigid adherence to established norms. Such leadership helps create psychologically safe environments where stakeholders can experiment, make mistakes, and learn collectively—conditions essential for long-term adaptation and resilience.

- Leveraging Cultural and Normative Change

- Conservation practice must integrate cultural narratives, traditional knowledge, and local worldviews into decision-making frameworks.

- Education and communication strategies should promote values of stewardship, interdependence, and ecological justice, shifting public perception from control of nature toward coexistence.

- Engaging art, storytelling, and place-based learning can help translate abstract sustainability goals into meaningful community action.

Collectively, these implications move the field beyond technocratic or managerial paradigms and toward transformative governance that is participatory, adaptive, and justice-oriented.

Building on these insights, the review introduces a Transition Toolkit for Practice to support practitioners, policymakers, and communities in operationalizing transformative change:

- Power Redistribution: Establish Indigenous and local co-management committees to ensure equitable decision-making and accountability.

- Behavioral Empowerment: Foster trust-building, participatory education, and peer learning to anchor behavioral transformation within community practice.

- Institutional Learning: Embed reflexive monitoring and adaptive governance cycles to sustain long-term transformation and learning-by-doing.

- Cross-Scale Integration: Connect local initiatives to regional and global policy frameworks to enhance coherence, scalability, and systemic impact.

- Justice and Inclusion: Mainstream social justice and equity criteria in all stages of conservation planning and implementation to ensure fair distribution of benefits and responsibilities.

4.2. Research Directions

The synthesis highlights that while the discourse on transformation in coastal conservation has expanded considerably, empirical and methodological gaps remain. Addressing these is crucial for translating conceptual advances into actionable knowledge. Four major research priorities emerge:

- 1.

- Longitudinal and Comparative Studies

Future research should prioritize long-term, comparative analyses that capture the durability, reversibility, and unintended consequences of transformative initiatives. Current studies often focus on short-term project outcomes, overlooking how institutional, ecological, and cultural changes evolve over time. Longitudinal data are essential to understand whether transformations remain resilient under shifting political regimes, climate pressures, and socio-economic changes. The transition from the SCORE project (establishing baselines) to the PRO-CLIMATE project (implementing behavioral change) offers a rare model of longitudinal continuity. By extending the observation window across two funding cycles, such initiatives allow researchers to trace whether behavioral changes persist after the initial technical interventions are complete. Comparative research across geographies—such as small island states, deltas, and estuaries—would also help to identify context-dependent dynamics and transferable lessons.

- 2.

- Cross-Scale Governance and Multi-Level Interactions

Transformation is inherently multi-scalar, linking local experimentation with regional and global governance architectures and behavioral dynamics. Research should therefore investigate how innovations at community or municipal levels interact with national policies, international conventions, and market-based mechanisms (e.g., blue carbon finance, marine spatial planning), and how behavioral alignment, trust-building, and collective motivation mediate these interactions across scales. Understanding how behavioral transformation is reinforced or constrained by institutional and policy architectures will be essential for designing coherent, multi-level strategies for sustainable coastal governance.

- 3.

- Equity, Power, and Justice in Behavioral Transformation

A key research frontier lies in equity-centered approaches that interrogate how benefits, risks, and responsibilities are distributed throughout transformative processes. Scholars should explore who defines transformation, whose values are prioritized, and who gains or loses from institutional or ecological reconfigurations. Critical methodologies—from feminist political ecology to decolonial and intersectional frameworks—can expose hidden power dynamics and reveal alternative pathways grounded in justice and inclusion. Empirical work should also examine mechanisms and behaviors that operationalize equity, such as community-led governance, co-management, and rights-based approaches.

- 4.

- Methodological Integration and Knowledge Co-Production

There is a need for mixed-methods and transdisciplinary approaches that bridge ecological, social, and cultural domains. Quantitative ecological metrics (e.g., biodiversity indices, habitat recovery rates) must be complemented with qualitative insights into governance processes, community perceptions, and cultural narratives. Participatory action research, scenario co-development, and indigenous-led methodologies can enhance knowledge legitimacy and foster mutual learning. Methodological pluralism—linking natural sciences, social sciences, and the humanities—strengthen the empirical basis for understanding complex, adaptive change.

- 5.

- Theorizing Transformation as Process, Not Outcome

Finally, theoretical work should move beyond framing transformation as a discrete end-state and instead conceptualize it as an ongoing process of behavioral, institutional, and systemic adaptation, negotiation, and emergence. Transformation unfolds through the continuous alignment of structures and behaviors where shifts in norms, trust, and collective motivation reinforce institutional and ecological change [22].

Integrating complex systems theory with critical governance, social justice, and behavioral change perspectives can yield richer explanations of how transformations unfold, stabilize, or regress. This conceptual shift calls for analytical frameworks that accommodate uncertainty, feedbacks, and multiple forms of knowledge—capturing not only structural dynamics but also the behavioral mechanisms through which stakeholders learn, adapt, and co-create sustainable futures.

While this review advances an integrative understanding of transformative and behavioral change, several limitations highlight directions for future research. The evidence base remains fragmented, with heterogeneous outcome measures and limited longitudinal data that hinder cross-case comparison and causal inference. Future studies should therefore adopt long-term and mixed-methods approaches to trace how behavioral, institutional, and ecological transformations interact and endure over time. Expanding geographical and linguistic coverage will also be critical to include underrepresented perspectives, particularly from coastal communities in the Global South. By doing so, the field can move toward a more integrated and justice-oriented science of transformation, capable of guiding the cultivation of resilient and equitable coastal futures.

In sum, this review positions coastal biodiversity conservation not as an effort to preserve ecological stability but as the active cultivation of resilient, just, and adaptive socio-ecological futures. The following Table 1 provides an overview.

Table 1.

Synthesis of the Literature Review Findings.

5. Conclusions

This review demonstrates that transformative change in coastal biodiversity conservation is both urgently needed and increasingly recognized as a central pathway to address accelerating ecological crises. The synthesis of 134 studies reveals that transformation does not occur through linear or isolated processes but instead emerges from the interplay of governance innovation, behavioral transformation, socio-ecological restructuring, and paradigmatic shifts in human–nature relationships. While each pathway provides critical leverage points, their combined operation highlights the complexity of coastal systems as dynamic, adaptive, and politically contested arenas.

The review contributes to scholarship by offering the first structured synthesis of transformative approaches specifically in coastal contexts, developing a typology of interventions and identifying enabling and constraining factors across scales. The analysis underscores that transformation requires more than technical solutions: it is deeply embedded in power relations, equity considerations, and cultural worldviews. The Social–Ecological Systems (SES) Framework provides a useful lens for understanding these dynamics, yet our findings caution against overlooking the political dimensions and historical legacies that shape transformation processes.

For research, the review identifies pressing priorities: the need for longitudinal studies to assess durability of interventions, systematic integration of equity and justice analyses, attention to the political economy of transformation, cross-scale governance dynamics, and meaningful incorporation of indigenous and local knowledge. Addressing these gaps will strengthen both the theoretical depth and practical relevance of transformative biodiversity research.

For practice, the findings carry important implications for policymakers, practitioners, and communities. Effective transformative action demands inclusive governance structures that empower marginalized voices, innovative restoration approaches that go beyond historical baselines, and paradigmatic shifts that embed ecological values into societal norms. Such approaches will be critical for ensuring resilience in coastal systems that face escalating pressures from climate change, development, and resource exploitation.

By systematically integrating behavioral transformation into the SES Framework, this review provides a novel analytical bridge between conservation science and social behavioral theory.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411186/s1. Reference [48] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-M.N. and D.I.-K.; Methodology, A.-M.N.; Formal analysis, A.-M.N. and D.I.-K.; Writing—original draft, A.-M.N. and D.I.-K.; Writing—review & editing, D.I.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union under the Horizon Europe Programme 1531 (HORIZON-CL6-2022-BIODIV-01), grant number 101082327 (PRO-COAST). Additionally, this paper contains one example of the Pro-Climate project (grant number 101137967) European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA) under the Horizon Europe Programme (HORIZON-CL5-2023-D1-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the first author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, 1547 GPT-4, 2024) to support the translation and linguistic refinement of selected passages. The tool was primarily used to ensure clarity and accuracy in English. The second author did not use this tool in their contributions. The authors have reviewed and edited all output thoroughly. This literature review was developed within the framework of the PRO-COAST project (Work Package 2: Theoretical framework research design). The authors would like to thank the wider project team in PRO-COAST and PRO-CLIMATE for their valuable input, especially in refining the keyword strategy and supporting the literature selection process. Further, the authors thank Katarzyna Barańczuk, at the Coastal City Living Lab–Poland, University of Gdańsk and David Herbert for their contributions to the paper through providing information on Poland’s Living Lab in relation to the PRO-CLIMATE project and Norway’s Case Study in relation to the PRO-COAST project. Finally, the authors thank both coordinators of PRO-COAST (Robert Kenwall; Anatrack Ltd. (Wareham, MA, USA) and Judie Ewald; Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (Fortinbridge, UK)/European Sustainable Use Group) and PRO-CLIMATE (Iason Tamiakis; Tero Ltd., Kirkenes, Norway) for their support in finalizing this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Barnosky, A.D.; García, A.; Pringle, R.M.; Palmer, T.M. Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schickhoff, U.; Bobrowski, M.; Offen, I.A.; Mal, S. The biodiversity crisis in the Anthropocene. In Geography and the Anthropocene; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 79–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardakas, L.; Perdikaris, C.; Freyhof, J.; Zimmerman, B.; Ford, M.; Vlachopoulos, K.; Giamas, C.; Economou, A.N.; Kalogianni, E. Global patterns and drivers of freshwater fish extinctions: Can we learn from our losses? Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Making Peace with Nature: Ascientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate Biodiversity Pollution Emergencies, Nairobi; UNEP 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/making-peace-nature (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- He, Q.; Silliman, B.R.; Liu, Z. Climate change, human impacts, and coastal ecosystems: Implications for the future. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R972–R982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Agusti, S.; Barbier, E.; Britten, G.L.; Castilla, J.C.; Gattuso, J.P.; Fulweiler, R.W.; Hughes, T.P.; Knowlton, N.; Lovelock, C.E.; et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature 2020, 580, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmi, N.; Sutherland, M.; Farahmand, S.; Haraldsson, G.; van Doorn, E.; Ernst, E.; Allemand, D.; Bax, N.; Calcinai, B.; Carvalho, S.; et al. Deep sea nature-based solutions to climate change. Front. Clim. 2023, 5, 1169665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Transformative Change Assessment—Summary for Policymakers: Thematic Assessment of the Underlying Causes of Biodiversity Loss, Determinants of Transformative Change, and Options for Achieving the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity Ecosystem Services; Brondizio, E.S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivian, E.; Bernstein, A. (Eds.) Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dirzo, R.; Young, H.S.; Galetti, M.; Ceballos, F.; Isaac, N.J.B.; Collen, B. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 2014, 345, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclère, D.; Obersteiner, M.; Alkemade, R.; Almond, R.; Barrett, M.; Bunting, G.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Cramer, W.; Drouet, L.; Dürauer, M.; et al. Towards pathways bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity trends within the 21st century. Nature 2018, 585, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, L.; Böhm, M. Biodiversity: The decline in global biodiversity and how education can be part of the solution. In Meeting the Challenges of Existential Threats Through Educational Innovation; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2021; pp. 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marris, E. Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World; Bloomsbury Publishing (BMY): New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, B.; Fletcher, R. Towards convivial conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 17, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Bessinger, M.; Dayaram, A.; Holness, S.; Kirkman, S.; Livingstone, T.-C.; Lombard, A.; Lück-Vogel, M.; Pfaff, M.; Sink, K.; et al. Advancing land-sea integration for ecologically meaningful marine management. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 236, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.D.; Megonigal, J.P.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Bailey, V.L.; Butman, D.E.; Canuel, E.A.; Diefenderfer, H.L.; Kroeger, K.D.; Mayorga, E.; Neumann, R.B.; et al. Representing the function and sensitivity of coastal interfaces in global Earth-system models. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, L.; Rahman, M.F.; McCraine, S.; Krause, D.; Hossain, M.F.; Bahadur, A.V.; Huq, S. Transformational adaptation in the context of coastal cities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 449–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refulio-Coronado, S.; Lacasse, K.; Dalton, T.; Humphries, A.; Basu, S.; Uchida, H.; Uchida, E. Coastal and marine socio-ecological systems: A systematic review of the literature. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 648006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M.A.; Islam, A.R.M.T. Review of coastal land transformation: Factors, impacts, adaptation strategies, and future scopes. Geogr. Sustain. 2024, 5, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, A.; Spundflasch, S.; Soares, A. Sustainable Urban Mobility in Europe—Implementation Needs Behavioral Change; SUITS Policy Brief 3a. 2020. Available online: https://www.suits-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/SUITS_Policy-brief-3a.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Nienaber, A.-M.; Spundflasch, S.; Soares, A.E.; Woodcock, A. Behavioral change in local authorities to increase organisational capacity. In Capacity Building in Local Authorities for Sustainable Transport Planning; Woodcock, A., Saunders, J., Fadden-Hopper, K., Eds.; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 319, pp. 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social–ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, G.; Walker, B.; Perego, P. Planetary boundaries: Ecological foundations for corporate sustainability. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 307–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temper, L.; Walter, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Kothari, A.; Turhan, E. A perspective on radical transformations to sustainability: Resistances, movements and alternatives. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Colding, J.; Berkes, F. Synthesis: Building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. In Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 352–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopín, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, A.; Spundflasch, S.; Soares, A.; Woodcock, A. Distrust as a hazard for future sustainable mobility planning: Rethinking employees’ vulnerability when introducing new technologies in local authorities. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Rethinking community-based conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keahey, J. Sustainable development and participatory action research: A systematic review. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2021, 34, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, O.-L.; Olsson, P.; Nilsson, W.; Rose, L.; Westley, F.R. Navigating emergence and system reflexivity as key transformative capacities. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, S.; Mastrángelo, M.E.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Meli, P. Transformative governance for linking forest and landscape restoration to human well-being in Latin America. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacha, M.S.; Muhammad, M.; Kılıç, Z.; Nafees, M. The dynamics of public perceptions and climate change in Swat Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwertsson, A.; Lindström, U.; Aune, M.; Berg, E.; Skarðhamar, J.; Varpe, Ø.; Primicerio, R. Rapid climate change increases diversity and homogenizes composition of coastal fish at high latitudes. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, M.; Borgström, S.; Farrelly, M. Urban transformative capacity: From concept to practice. Ambio 2019, 48, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, A.-M.; Hofeditz, M.; Romeike, P.D. Vulnerability and trust in leader–follower relationships. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. The politics of development and conservation: Legacies of colonialism. Peace Change 1997, 22, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G. Societal transformation in response to global environmental change: A review of emerging concepts. Ambio 2015, 44, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J. Vulnerability before adaptation: Toward transformative climate action. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, A.M.; Romeike, P.D.; Searle, R.; Schewe, G. A qualitative meta-analysis of trust in supervisorrsubordinate relationships. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 507–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).