Effects of Personality Type Tools and Problem-Solving Methods on Engineering Company Project Success

Abstract

1. Introduction and Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

| Variable | Operational Definition | Items | Measurement Scale | Item Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality tools | Use of personality tools in teams, knowledge and experience in different tools; MBTI | 20 | 5-point Likert scale | Personality tools can help project managers to establish good-performing teams. The Myers–Briggs® tool can be used as a guiding tool when forming teams in projects. | [18,65] |

| Problem solving | Use of problem-solving methods in teams, knowledge and experience in different tools | 23 | 5-point Likert scale | When problems occur during the project, problem-solving methods are used. Problem-solving methods help identify and remove problems that have occurred during a project’s life cycle. | [66] |

| Project success | Impact of personality tools and problem-solving methods during project life cycle on termination of projects with success | 22 | 5-point Likert scale | Teams created based on personality tools can help project managers to achieve greater success on projects. Using the right team members (team members with certain profiles) to help solve problems can increase the chances of successful realization of projects. Sharing the results (knowledge sharing) of the solved problems can help achieve project goals with success. | [13,14,35,61,67,68] |

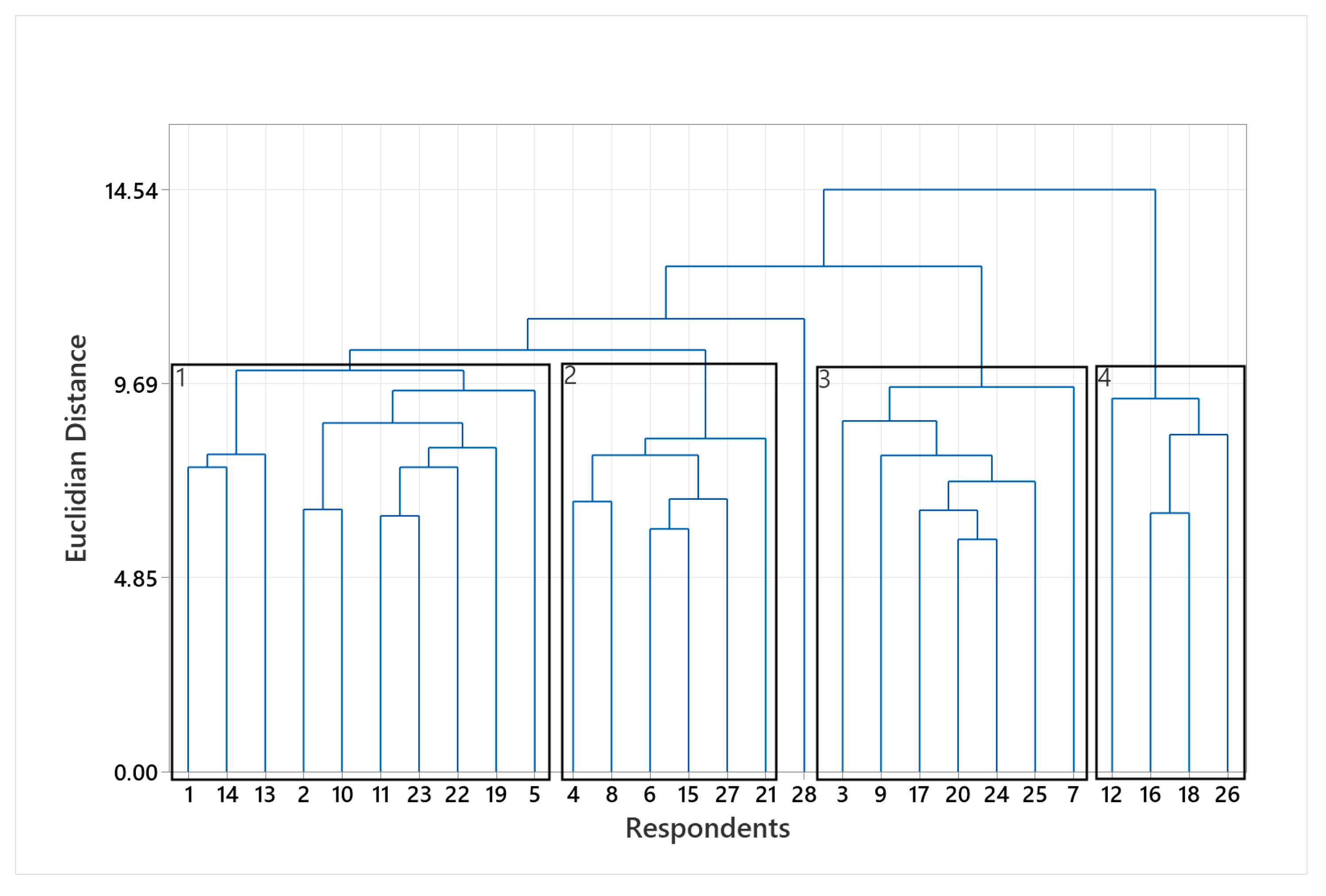

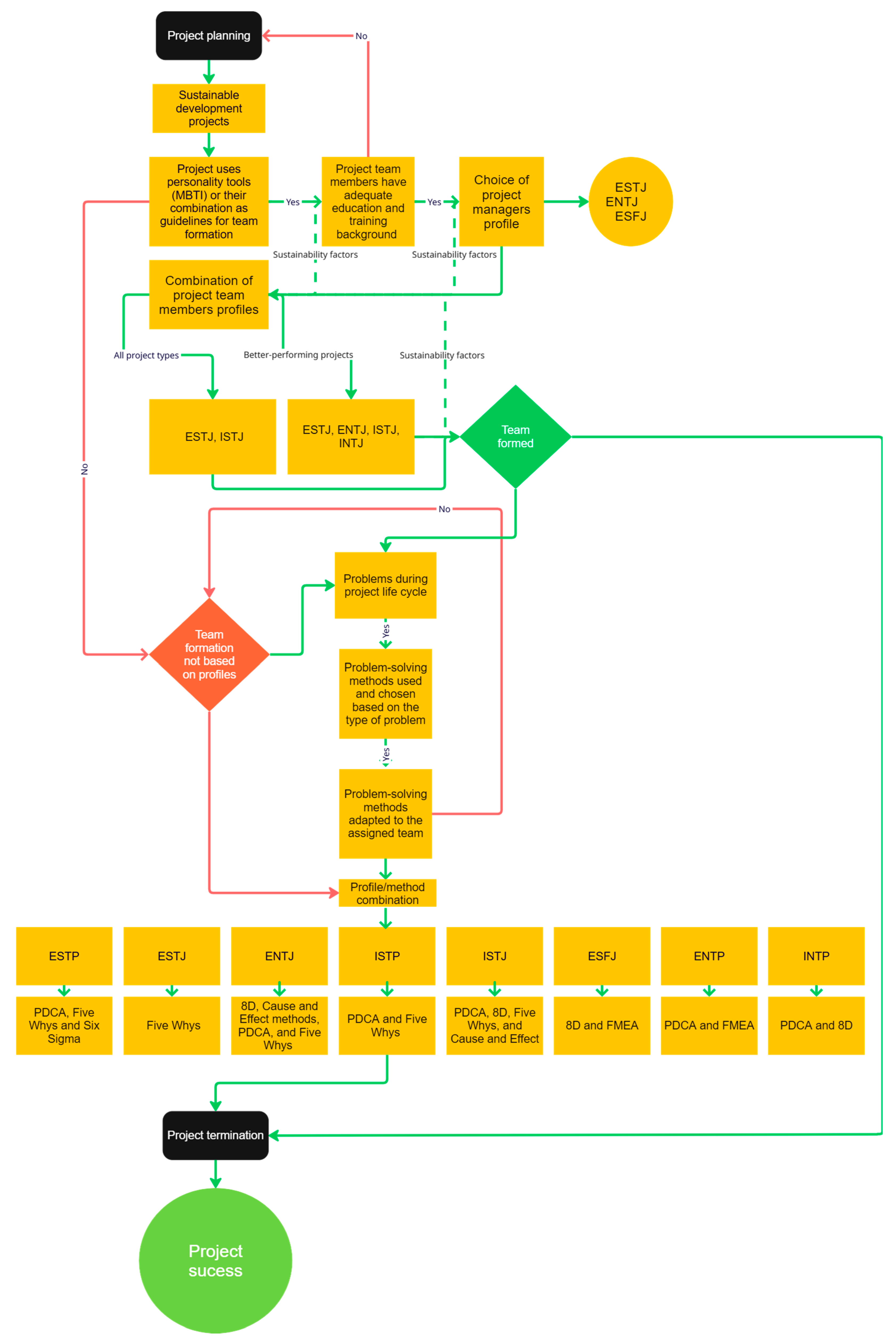

3. Results and Discussion

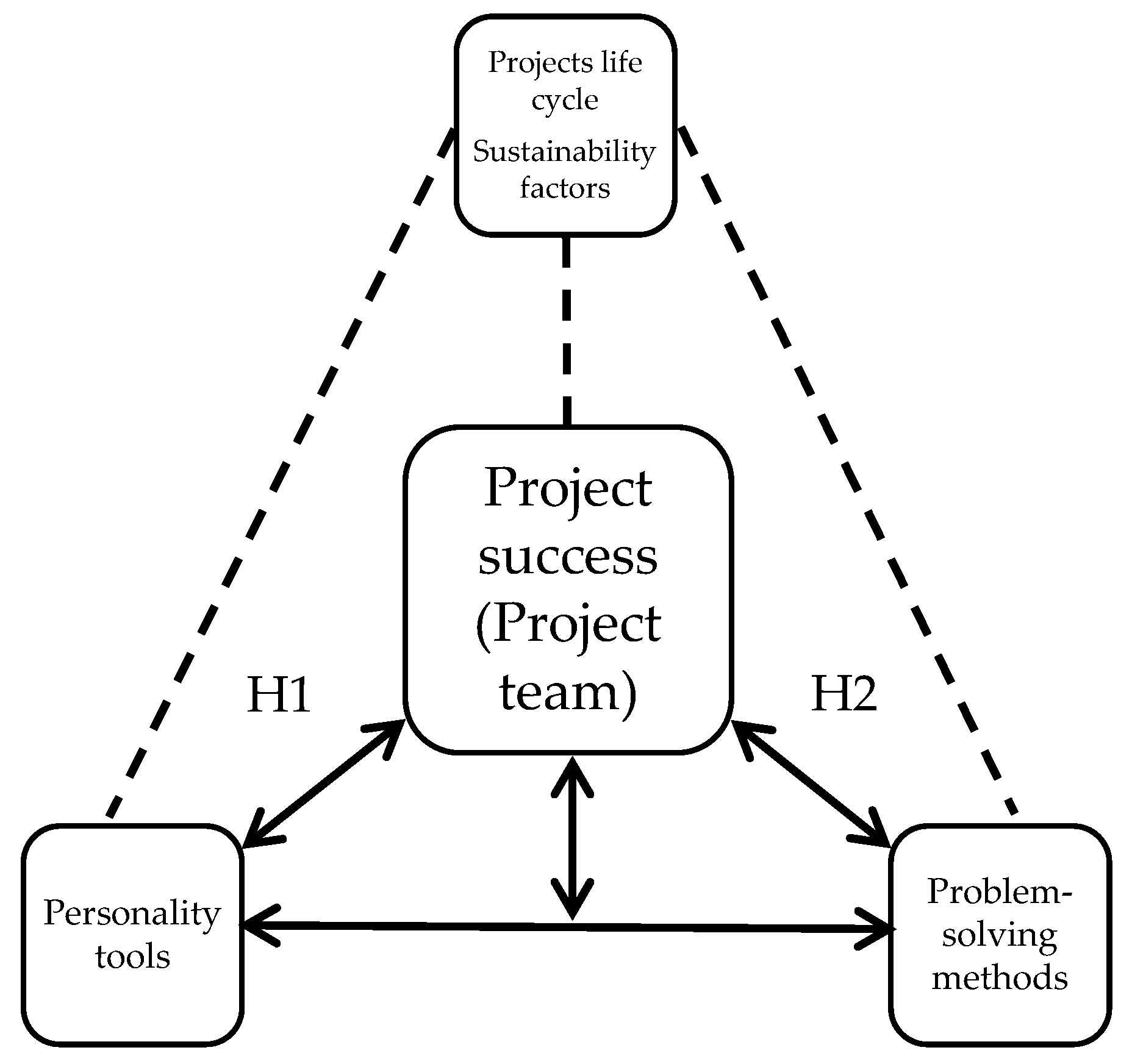

- Objective 1. Personality tools used for project team formation have a positive impact on project success. Expected direction: Positive (direct) relationship; project teams formed based on personality profiles contribute to an increase in successfully terminated projects.

- Objective 2. Problem-solving tools used in projects have a positive impact on project success. Expected direction: Positive relationships; projects and project teams that use problem-solving methods during the project’s life cycle will enable projects to terminate with success.

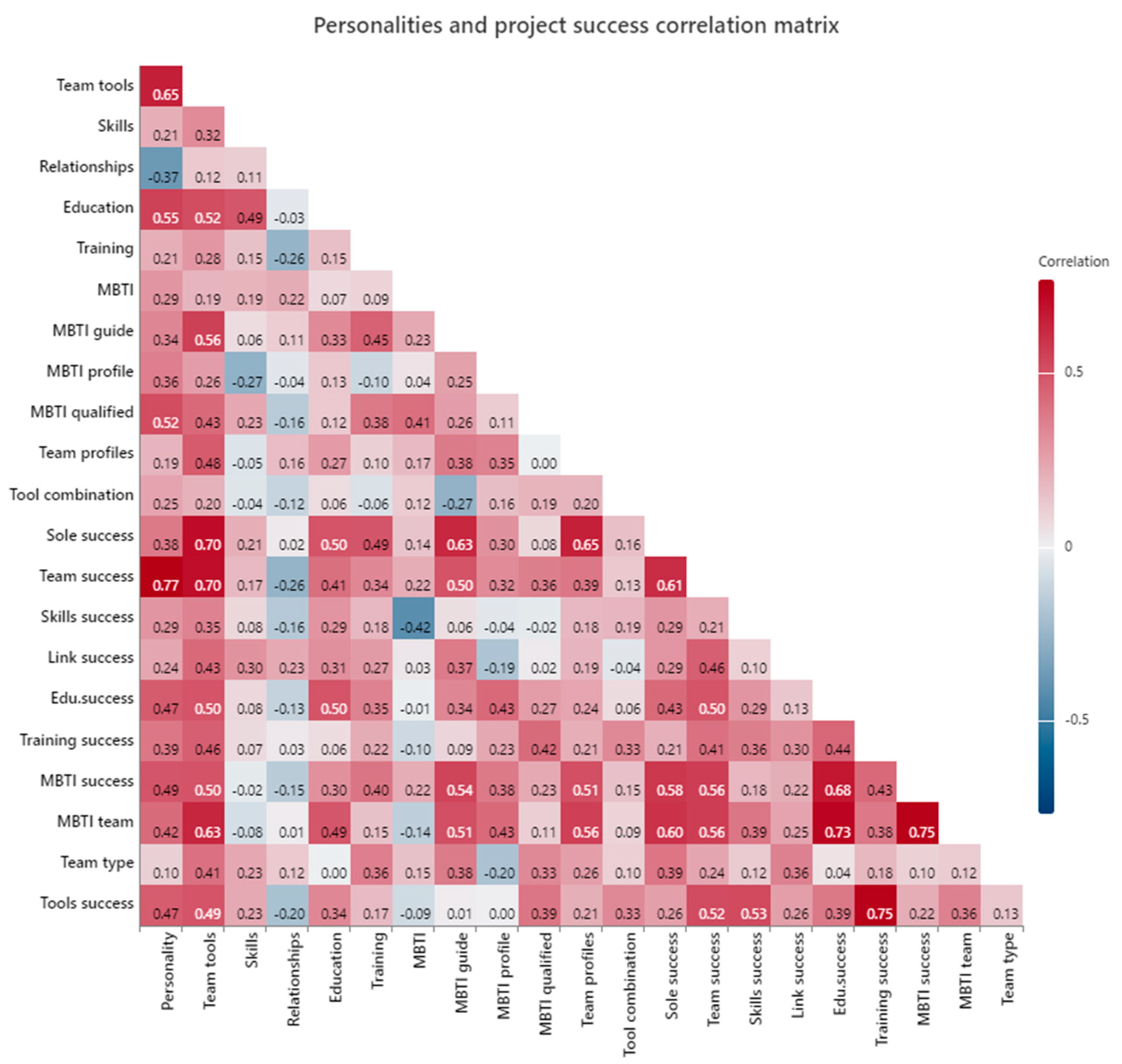

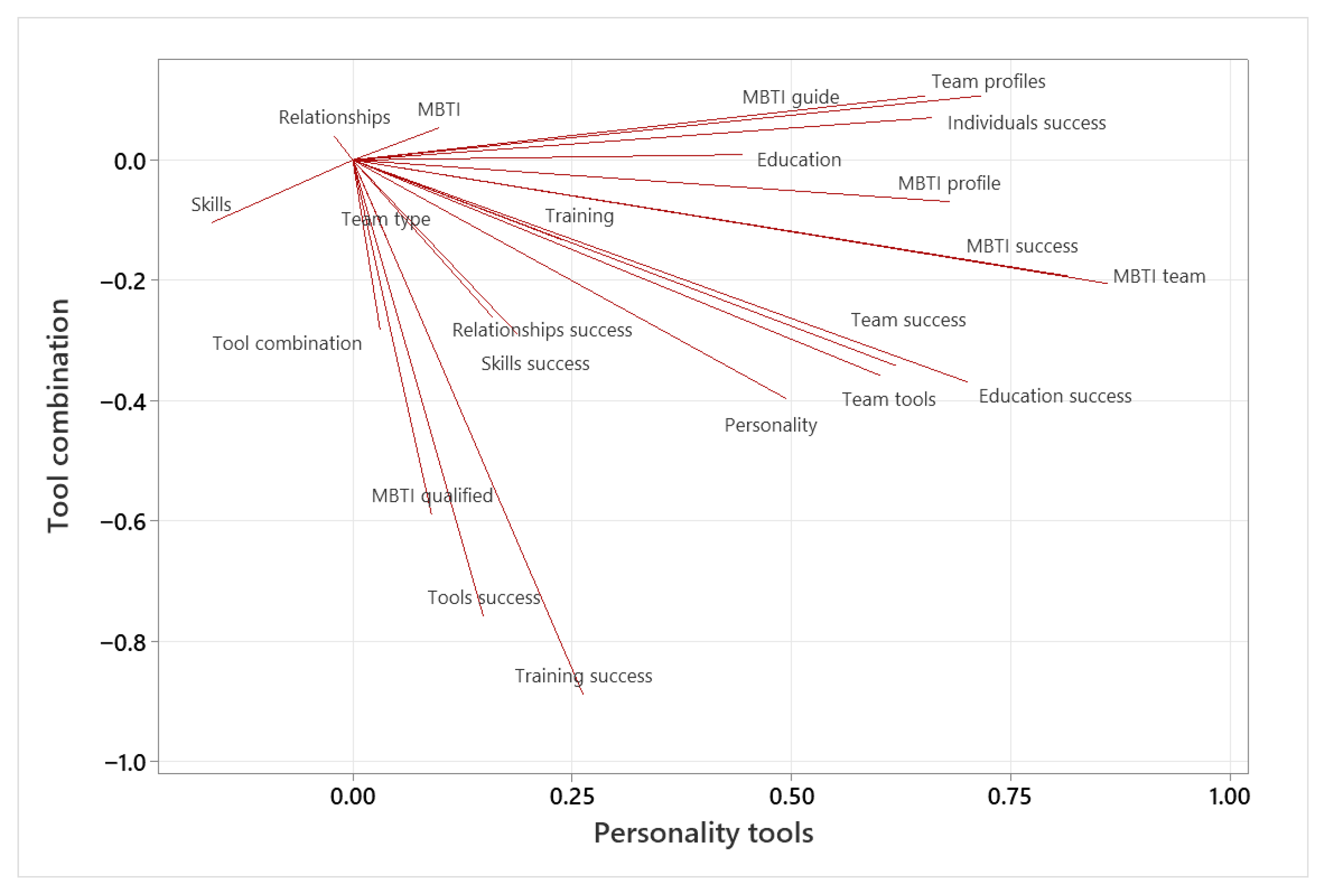

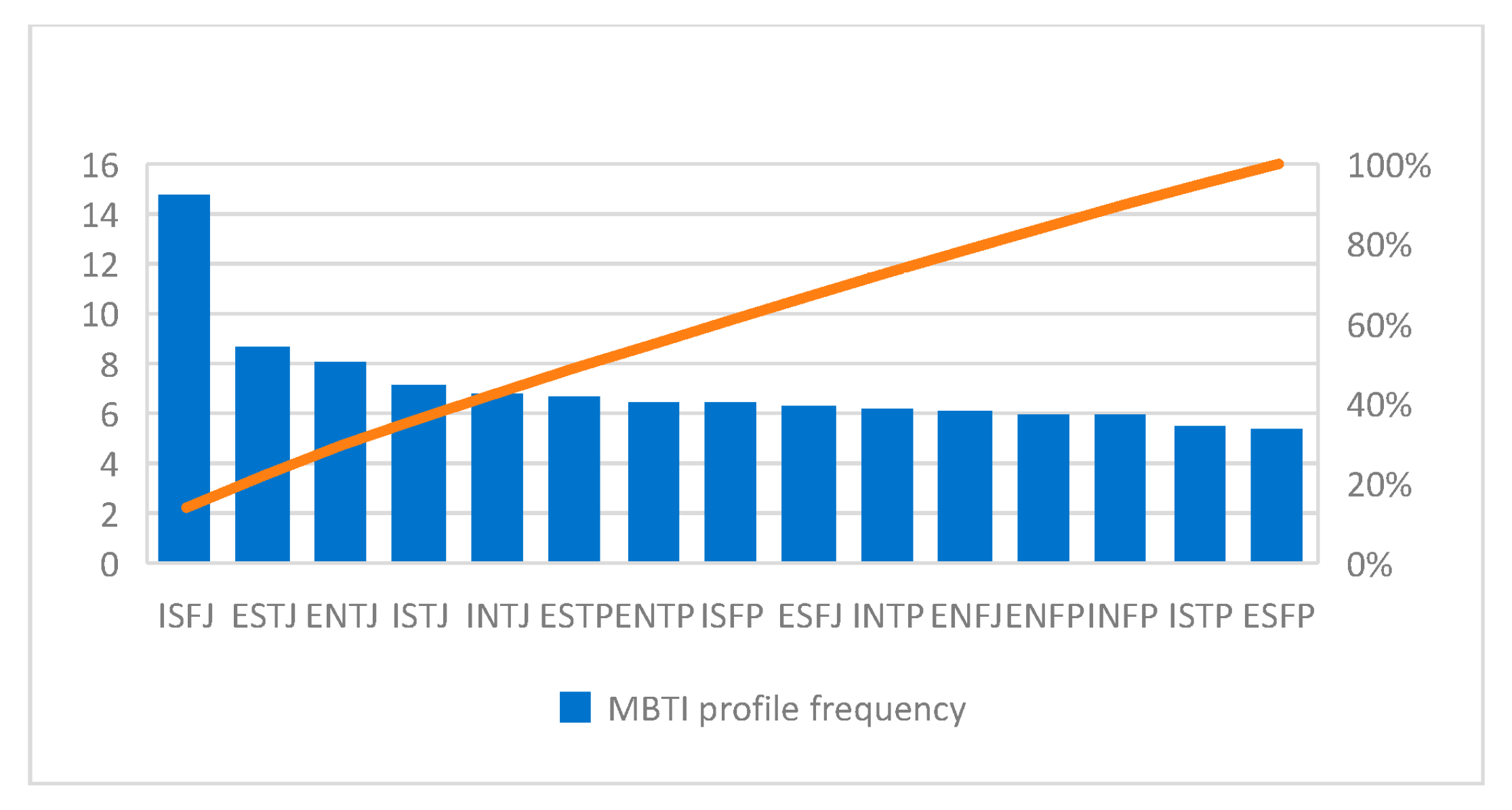

3.1. Objective 1: Influence of Personality Tools on Project Success

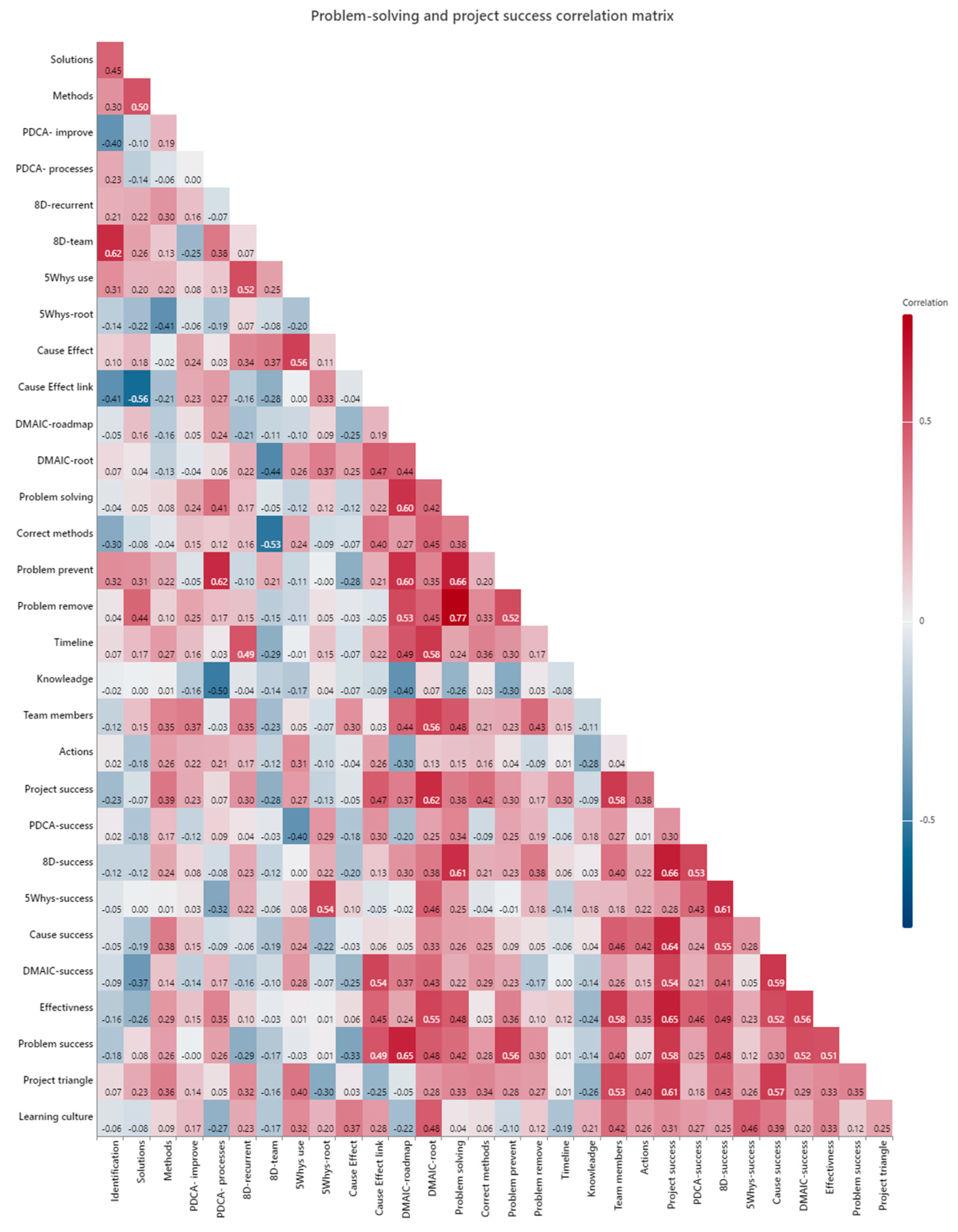

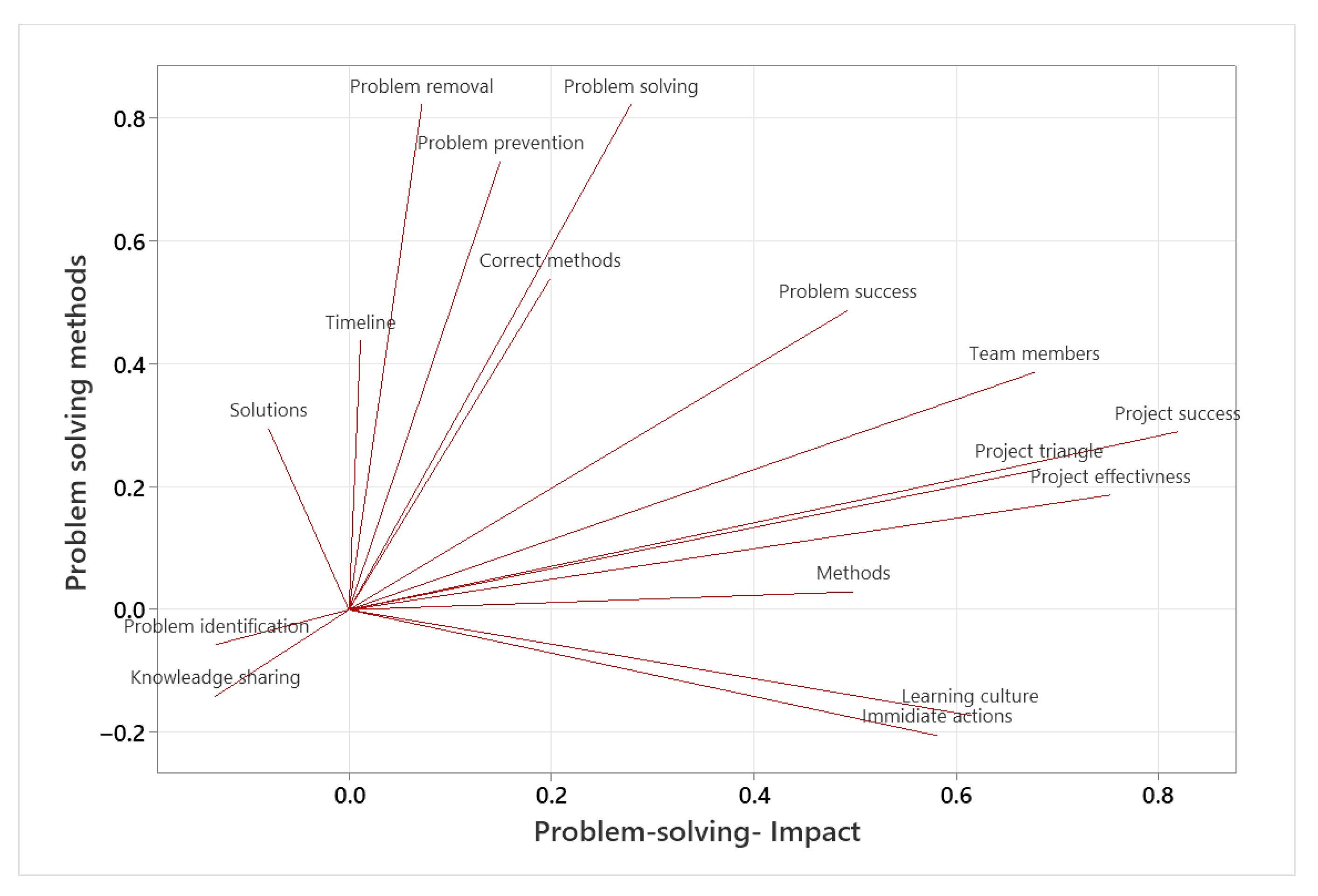

3.2. Objective 2: Influence of Problem-Solving Methods on Project Success

4. Conclusions

- Personality tools have a distinct and significant relationship with project success;

- Problem-solving methods have an observed significant influence on project success.

4.1. Sustainable Development Projects, Sustainability, and Project Success

4.2. Future Recommendations

- Similar research should be conducted where the influence of the matrix organization on the project outcome is also observed.

- Similar research should be conducted on personality tools, focusing on how different identified personality tools affect project success in the observed research area, while also mitigating subjectivity during personality profile assessments.

- Similar research should be conducted on problem-solving methods, with a greater emphasis on enabling problem-solving methods to influence the outcome of projects than on examining their impact, enabling organizations to gain a competitive advantage by investing in the resource dynamic capability building [109].

- Sustainability-related recommendations:

- Similar research should be conducted on individual personality types and their influence on success, with a focus on identifying internal unique resources and capabilities that contribute to achieving sustainable competitive advantage [110].

- Current research could be broadened to take all sustainability factors (environmental, social, and governmental) into consideration to understand the full impact of sustainable practices, personality tools, and problem-solving methods on project success.

- Similar research could be conducted to investigate the impact of personality tools and problem-solving methods on sustainable project success.

- Replication and generalization:

- The current research should be directly replicated using the original methods on a larger sample with diverse personality traits across various countries with differing project management practices. Additionally, the existing hypothesis should be expanded to encompass multiple problems to enhance generalizability and advance scientific knowledge. In evaluating replication across different sectors and nations, the reliability of the original study, its methodologies, materials, and sample size were considered. Consequently, the country’s status, cultural and economic development, impact of consumer and industrial goods sectors, and use of global project management practices should be considered essential prerequisites for direct replication. The research should also be replicated to validate the novel frameworks presented in this paper.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBTI® | Myers–Briggs Type Indicator |

| DISC | Dominance, Influence, Stamina, and Conscientiousness |

| PDCA | Plan–Do–Check–Act |

| DMAIC | Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control |

| FMEA | Failure Mode and Effect Analysis |

References

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 7th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, M. The Effect of Project Manager’s Soft Skills on Success of Project in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W. Study of the Effects of Personality Traits on Team Collaboration and Organizational Performance. Highlights Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 37, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, C.; Pereira, L.; Fernandes, A.; Martinho, R. Complex Problem Solving as a Source of Competitive Advantage. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ranjan, S. Genetic and Environmental Factors Shaping The Personalities Of Students Critical Analysis. Libr. Prog. Int. 2024, 44, 28870–28887. [Google Scholar]

- Ameer, A.; Naz, F.; Taj, B.; Ameer, I. The Impact of Manager’s Personality Traits on Project Success through Affective Professional Commitment: The Moderating Role of Organizational Project Management Maturity System. J. Facil. Manag. 2021. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, T.; Marion, J.; Bourdeau, D. Researching MBTI Personality Types: Project Management Master’ s Degree Students. J. Hum. Resour. Adult Learn. 2015, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kathayat, B.B.; Rawat, D.; Gurung, B. Impact of Personality Traits on Sustainable Entrepreneurship Development. Interdiscip. J. Innov. Nepal. Acad. 2023, 2, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Aldaihani, A.; Shah, A. Big-Five Personality Traits Mapped with Software Development Tasks to Find Most Productive Software Development Teams. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, J.M.; Gutiérrez, G.; Cano, E.L.; Garzás, J.; González de Lena, M.T.; Moguerza, J.M.; Fernández Muñoz, J.J. Effects of Personality Types on the Performance of Educational Teams. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.M.; Xu, L.; de Vrieze, P.T. The Impact of Personality Traits on Scrum Team Effectiveness: Insights from Vietnamese Software Development Companies. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2025, 188, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Ornoy, H.; Keren, B. MBTI Personality Types of Project Managers and Their Success: A Field Survey. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Lo, D.; Bao, L.; Sharma, A.; Li, S. Personality and Project Success: Insights from a Large-Scale Study with Professionals. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution, ICSME 2017, Shanghai, China, 17–22 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovic, S.; Matić, J.; Opacic, G. Personality Traits Composition and Team Performance. Manag. Sustain. Bus. Manag. Solut. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 25, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Mason, B.; Carducci, B.; Nave, C. Myers Briggs Type Indicator. In Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Volume II; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. A Study on Effective Team Composition Strategies Based on MBTI Personality Types. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2025, 15, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendra, I.; Blessing, L.; Silva, A.; Ang, R. Exploring the Link between Students’ MBTI Personality Types and Design Team Performance. Proc. Des. Soc. 2025, 5, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.; Swan, A. Evaluating the Validity of Myers–Briggs Type Indicator Theory: A Teaching Tool and Window into Intuitive Psychology. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2019, 13, e12434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, G.J. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI): Some Psychometric Limitations. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Pap. 1995, 30, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H. A Study on the MBTI Personality Type Change of the Korean Medical Students. J. Orient. Neuropsychiatry 2019, 30, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, D.; Beck, T. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Profile of Undergraduate Therapeutic Recreation Students. Ther. Recreation J. 2020, 54, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, D.J.; Fisher, M.L.; Salmon, C. What Do Evolutionary Researchers Believe about Human Psychology and Behavior? Evol. Hum. Behav. 2023, 44, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.J.; Yadav, A.K.; Gupta, M. Role of Personality in Team Formation for Engineering Project Success. TPM Testing Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2025, 32, 768–773. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Ciarapica, F.; Germani, M.; Paciarotti, C. Relation of Project Managers’ Personality and Project Performance: An Approach Based on Value Stream Mapping. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2014, 7, 857–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. The Big Five Facets and the MBTI: The Relationship between the 30 NEO-PI (R) Facets and the Four Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) Scores. Psychology 2022, 13, 1504–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmaier, D.; Messerli, M. Preference Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-009-47579-2. [Google Scholar]

- Latief, Y.; Ichsan, M.; Hadi, D.A. Analysis of Relationship between Construction Project Manager’s Characters and Project Schedule Performance Using MBTI Approach. SSRN Electron. J. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykourentzou, I.; Antoniou, A.; Naudet, Y.; Dow, S.P. Personality Matters: Balancing for Personality Types Leads to Better Outcomes for Crowd Teams. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW 2016, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Krieger, F.; Kim, S.; Nixon, N.; Greiff, S. Revisiting the Relationship between Team Members’ Personality and Their Team’s Performance: A Meta-Analysis. J. Res. Personal. 2024, 112, 104526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maric, A. Comparison of Personality Type Tools and Their Relationship with Project Success. In Proceedings of the 4th International Scientific Conference LEAN Spring Summit, Lovran, Croatia, 4–5 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, Z.; Jie, L.; Yan, R.; Li, M. Personality Analysis Based on Multi-Characteristic EEG Signals. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 102, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostál, J. Theory of Problem Solving. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 174, 2798–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, S.; Seth, M. Do Soft Skills Matter?—Implications for Educators Based on Recruiters’ Perspective. IUP J. Soft Ski. 2013, 7, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Morandini, S.; Fraboni, F.; De Angelis, M.; Puzzo, G.; Giusino, D.; Pietrantoni, L. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Workers’ Skills: Upskilling and Reskilling in Organisations. Informing Sci. 2023, 26, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Chen, C.M.; Hsu, J.S.C.; Fu, T.W. The Impact of Team Knowledge on Problem Solving Competence in Information Systems Development Team. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1692–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maric, A. Effects of Problem-Solving Methods on Project Success. In Proceedings of the 4th International Scientific Conference LEAN Spring Summit, Lovran, Croatia, 4–5 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Doskočil, R.; Lacko, B. Root Cause Analysis in Post Project Phases as Application of Knowledge Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peças, P.; Encarnação, J.; Gambôa, M.; Sampayo, M.; Jorge, D. PDCA 4.0: A New Conceptual Approach for Continuous Improvement in the Industry 4.0 Paradigm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipupo, O.; Adeyinka, A.; Durodola, O. Exploring Lean Six Sigma: A Comprehensive Review of Methodology and Its Role in Business Improvement. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 2023, 4, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdiyah, S.; Eltivia, N.; Afandi, A. Root Cause Analysis Using Fishbone Diagram: Company Management Decision Making. J. Appl. Bus. Tax. Econ. Res. 2022, 1, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirtina, L.-M.; Dumitrascu, A.-E.; Cazacu, D.V.; Ianasi, C.A.; Rădulescu, C.; Tătar, A.M.; Pasăre, M.M.; Nioață, A.; Cirtina, D. Eight-Disciplines Analysis Method and Quality Planning for Optimizing Problem-Solving in the Automotive Sector: A Case Study. Processes 2025, 13, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchia, M.; Sacchi, P.; Marvulli, L.N.; Ragazzoni, L.; Muzzi, A.; Polo, L.; Bruno, R.; Salio, F. Healthcare Application of Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA): Is There Room in the Infectious Disease Setting? A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, M.N.; Harry, K.D. Leveraging Kaizen with Process Mining in Healthcare Settings: A Conceptual Framework for Data-Driven Continuous Improvement. Healthcare 2025, 13, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, F. The Appreciative Inquiry Method—A Suitable Candidate for Action Research? Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2013, 30, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malykhin, O.; Aristova, N.; Kalinina, L.; Opaliuk, T. Developing Soft Skills among Potential Employees: A Theoretical Review on Best International Practices. Postmod. Open. 2021, 12, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, R.; Saggi, K. Incorporating “Soft Skills” Into the Collaborative Problem-Solving Equation. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Chirino Chace, B.; Wright, J. Cultural Diversity Drives Innovation: Empowering Teams for Success. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2020, 12, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Analysis of the Application of MBTI in Society and the Workplace. Lect. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2025, 85, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesheim, T. Exploring the Resource Manager Role in a Project-Based Organization. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 1626–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerio, C.A. Sustainability and Sustainable Development: A Review of Principles and Definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith, J.; Zwikael, O. When Is a Project Successful? IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2019, 47, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevin, D.; Pinto, J. The Project Implementation Profile: New Tool for Project Managers. Proj. Manag. J. 1986, 17, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.K.; Slevin, D.P. Critical Success Factors in Effective Project Implementation. In Project Management Handbook; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi Rad, M.; Mojtahedi, M.; Ostwald, M.J.; Wilkinson, S. A Conceptual Framework for Implementing Lean Construction in Infrastructure Recovery Projects. Buildings 2022, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Raman, A.; Sambamoorthy, N.; Prashanth, K. Research Methodology (Methods, Approaches and Techniques); San International Book Publication: Tamil Nadu, India, 2023; ISBN 978-81-965552-8-3. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Park, M. Qualitative versus Quantitative Research Methods: Discovery or Justification? J. Mark. Thought 2016, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Zubkov, P. Quantitative Research Designs. In Quantitative Research for Practical Theology; Andrews University Faculty: Berrien Springs, MI, USA, 2023; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Designing a Questionnaire for a Research Paper: A Comprehensive Guide to Design and Develop an Effective Questionnaire. Asian J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 11, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, A. How to Design, Implement, and Analyse a Survey; Edward Elgar Publishing: Glos, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-80037-616-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.K. Project Implementation Profile: A Tool to Aid Project Tracking and Control. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1990, 8, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D. Enhancing Project Performance through Effective Team Communication: A Comprehensive Study Integrating Project Management Quotient, Trust, and Management Information Systems. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2024, 9, 25574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipulu, M.; Ojiako, U.; Gardiner, P.; Williams, T.; Mota, C.; Maguire, S.; Shou, Y.; Stamati, T.; Marshall, A. Exploring the Impact of Cultural Values on Project Performance: The Effects of Cultural Values, Age and Gender on the Perceived Importance of Project Success/Failure Factors. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 364–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, L.; McMahan, C. The Influence of Project Manager’s Age on Project Success. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2019, 9, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample Size Justification. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, K.; Isaacson, M.; Ciro, C. Validity and Reliability of the Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Best Pract. Health Prof. Divers. 2017, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lutfauziah, A.; Handriyan, A.; Fitriyah, F.K. Assessment of Problem-Solving Skills in the Topic of Environment: Its Validity and Reliability. J. Pena Sains 2023, 10, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, M.H.; Klein, G.; Chen, H.G. The Role of Team Problem Solving Competency in Information System Development Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blak Bernat, G.; Qualharini, E.L.; Castro, M.S.; Barcaui, A.B.; Soares, R.R. Sustainability in Project Management and Project Success with Virtual Teams: A Quantitative Analysis Considering Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatz, I. Assumption-Checking Rather than (Just) Testing: The Importance of Visualization and Effect Size in Statistical Diagnostics. Behav. Res. Methods 2023, 56, 826–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, T.; Yi, S. A Comparison of Normality Testing Methods by Empirical Power and Distribution of P-Values. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2023, 52, 4445–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, C. Levene’s Test for Verifying Homoscedasticity Between Groups in Quasi-Experiments in Social Sciences. South East. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 25, 2119–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Abd Al-Hameed, K. Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient in Statistical Analysis. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2022, 13, 3249–3255. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, J.; Choi, K.; Lavy, S.; Rybkowski, Z.; Bigelow, B.; Li, W. Effects of Front-End Planning under Fast-Tracked Project Delivery Systems for Industrial Projects. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2017, 14, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.; Barbalho, S.; Silva, G.; Toledo, J. Benefits Management as a Path for Project Management Offices Contribute to Programs and Influence on Project Performance. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2018, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B.; Choi, S. The Effect of Learning Orientation and Business Model Innovation on Entrepreneurial Performance: Focused on South Korean Start-Up Companies. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Wetzel, A. Factor Analysis: A Means for Theory and Instrument Development in Support of Construct Validity. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2020, 11, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.; Hilton, A. Multiple Linear Regression. In Statistical Analysis in Microbiology: Statnotes; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 127–133. ISBN 978-0-470-55930-7. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Best (but Oft-Forgotten) Practices: The Multiple Problems of Multiplicity—Whether and How to Correct for Many Statistical Tests1. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesthuis, P.; Howe, M.L.; Otgaar, H. Meaningful Approaches to Assessing the Size of Effects in Memory Research: Applications and Recommendations for Study Design, Interpretation, and Analysis. Memory 2025, 33, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, M. Research Note: Interpreting Confidence Intervals. J. Physiother. 2024, 70, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. Optimal Two-Stage Group Sequential Designs Based on Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon Test. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyvanali, M.; Ardi, A.; Berlianto, M.P.; Sunarjo, R.A. Strengthening Job Performance through Social Cognitive Factors: The Roles of Self-Efficacy, Work Engagement, and Knowledge-Oriented Leadership. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 12, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.C.; Abreu, P.H.; Rodrigues, P.P.; Figueiredo, M.A.T. Imputation of Data Missing Not at Random: Artificial Generation and Benchmark Analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Gattone, S.; Fortuna, F.; Battista, T. Cluster Analysis as a Decision-Making Tool: A Methodological Review. In Decision Economics: In the Tradition of Herbert A. Simon’s Heritage; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2018; pp. 48–55. ISBN 978-3-319-60881-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, A.; Banks, D. Cluster Analysis: A Modern Statistical Review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2023, 15, e1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackhouse, M.; Rickley, M.; Liu, Y.; Taras, V. Homogeneity, Heterogeneity, or Independence? A Multilevel Exploration of Big Five Personality Traits and Cultural Values in 40 Nations. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2024, 230, 112795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, M.; Dubey, D. Methodology and Technique of 8D’s to Solve the Problem. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. IJARSCT 2023, 3, 2581–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behaz, A.; Djoudi, M. Adaptation of Learning Resources Based on the MBTI Theory of Psychological Types. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Issues 2012, 9, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Huzooree, G.; Yadav, M. Sustainable Project Management and Organizational Resilience. In Enhancing Resilience in Business Continuity Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 137–172. ISBN 979-8-3693-8809-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, J.; Knuts, S. Sustainability Impact and Effects Analysis—A Risk Management Tool for Sustainable Product Development. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus-Rosińska, A.; Iwko, J. Stakeholder Management—One of the Clues of Sustainable Project Management—As an Underestimated Factor of Project Success in Small Construction Companies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvijović, J.; Obradović, V.; Todorović, M. Stakeholder Management and Project Sustainability—A Throw of the Dice. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A.J.G.; Schipper, R.P.J. Exploring the Relationship between Sustainability and Project Success—Conceptual Model and Expected Relationships. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2016, 4, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.; Al-Adwan, A.S.; Alrousan, M.K.; Yaseen, H.; Mathani, B.; Wahsheh, F.R. Exploring the Nexus of Sustainability and Project Success: A Proposed Framework for the Software Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, M.; Latif, F.; Sajjad, A.; Eweje, G. Revisiting the Relationship between Sustainable Project Management and Project Success: The Moderating Role of Stakeholder Engagement and Team Building. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 30, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrzygłocka-Chojnacka, J.; Stanek, S.; Kuchta, D. Defining a Successful Project in Sustainable Project Management through Simulation—A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunawat, R.M.; Elmarzouky, M.; Shohaieb, D. Integrating Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Factors into the Investment Returns of American Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, A.; Taglialatela, J.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Determinants of Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, R.; Bansal, R.; Pruthi, N. Embedding Sustainability in Project Management: A Comprehensive Overview Embedding Sustainability in Project Management. In Multidisciplinary Approaches in AI, Creativity, Innovation, and Green Collaboration; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-6684-6366-6. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassani, F.; Saleem, M.R.; Messner, J. Integrating Sustainability in Engineering: A Global Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.; Farrell, P.; Al-edenat, M. The Impact of Project Sustainability Management (PSM) on Project Success: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Manag. Dev. 2020. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarez, R.P.F.; do Valle, C.G.B.; Alvarenga, J.C.; da Dias, F.C.; Vasco, D.A.; Guedes, A.L.A.; Chinelli, C.K.; Haddad, A.N.; Soares, C.A.P. Key Practices for Incorporating Sustainability in Project Management from the Perspective of Brazilian Professionals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, J.; Pappas, E. The Sustainable Personality: Values and Behaviors in Individual Sustainability. Int. J. High. Educ. 2014, 4, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Jamil, M.; Farooq, M.U.; Asim, M.; Rafique, M.Z.; Pruncu, C.I. Project Managers’ Personality and Project Success: Moderating Role of External Environmental Factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, F.S.; AlDhaen, E.; Yakymchuk, A. Enhancing Organizational Social Sustainability: Exploring the Effect of Sustainable Leadership and the Moderating Role of Micro-Level CSR. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S. Assessing the Impact of Social Sustainability Practices in Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives. Innov. Res. Thoughts 2024, 10, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.C.; Zailani, S.; Rahman, M.K.; Qiannan, Z.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Patwary, A.K. Impact of Sustainable Project Management on Project Plan and Project Success of the Manufacturing Firm: Structural Model Assessment. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Silvius, A.J.G.; Silva, C.; Leite, Â. The Contribution of Project Management to a More Sustainable Society: Exploring the Perception of Project Managers. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Holmen, E.; Havenvid, M.; De Boer, L.; Hermundsdottir, F. Open for Business: Towards an Interactive View on Dynamic Capabilities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 107, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailani, D.; Hulu, M.; Simamora, M.; Kesuma, S. Resource-Based View Theory to Achieve a Sustainable Competitive Advantage of the Firm: Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Entrep. Sustain. Stud. 2024, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 | 32.1 |

| Male | 19 | 67.9 |

| Age bracket | ||

| >45 | 8 | 28.6 |

| 18–24 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 25–34 | 6 | 21.4 |

| 35–44 | 14 | 50.0 |

| Number of projects | ||

| >10 | 20 | 71.4 |

| 2–3 | 2 | 7.1 |

| 3–5 | 5 | 17.9 |

| 5–10 | 1 | 3.6 |

| Size of project team | ||

| >30 people | 2 | 7.1 |

| 10 people | 12 | 42.9 |

| 10–30 people | 10 | 35.7 |

| <10 people | 3 | 10.8 |

| Mixed | 1 | 3.5 |

| >30 people | 2 | 7.1 |

| Work experience | ||

| >10 years | 19 | 67.9 |

| 3 to 5 years | 1 | 3.6 |

| 5 to 10 years | 8 | 28.6 |

| >10 years | 19 | 67.9 |

| Experience in project management | ||

| <1 year | 6 | 21.4 |

| >10 years | 7 | 25.0 |

| 1 to 3 years | 4 | 14.3 |

| 3 to 5 years | 1 | 3.6 |

| 5 to 10 years | 10 | 35.7 |

| Project duration | ||

| <1 year | 10 | 35.7 |

| >1 year | 13 | 46.4 |

| Both | 5 | 17.9 |

| Acquaintance with Personality Methods | Use of Personality Tools in the Project | Training in Personality Tools | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Myers–Briggs® personality type theory | 27 | 96.4% | 20 | 71.4% | 24 | 85.7% |

| Keirsey’s personality type theory | 2 | 7.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Katherine Benziger’s Brain Type theory | 1 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| The ‘Big Five’ Factors personality model | 2 | 7.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| The Four Temperaments/Four Humors | 1 | 3.6% | 1 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Carl Jung’s Psychological Types | 6 | 25.0% | 1 | 3.6% | 1 | 3.6% |

| Hans Eysenck’s personality type theory | 1 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| William Moulton Marston’s DiSC 1 personality theory | 14 | 53.6% | 5 | 17.9% | 10 | 35.7% |

| Belbin Team Roles and personality type theory | 14 | 53.6% | 3 | 10.7% | 9 | 32.1% |

| The Birkman Method® | 1 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 3.6% |

| Acquaintance with Problem-Solving Methods | Use of Problem-Solving Methods in the Project | Training in Problem-Solving Methods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| The Deming Cycle (PDCA 1) | 25 | 89.3% | 20 | 71.4% | 17 | 60.7% |

| The Eight Discipline Methodology (8D) | 23 | 82.1% | 17 | 60.7% | 21 | 75.0% |

| Five Whys | 25 | 89.3% | 17 | 60.7% | 18 | 64.3% |

| The Four-Step Innovation Process | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) | 21 | 75.0% | 13 | 46.4% | 10 | 35.7% |

| Appreciative Inquiry | 3 | 10.7% | 1 | 3.7% | 2 | 7.1% |

| Cause and Effect Analysis | 24 | 85.7% | 14 | 50.0% | 13 | 46.4% |

| Kepner–Tregoe Decision Analysis | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Kaizen | 12 | 42.9% | 4 | 14.3% | 5 | 17.9% |

| Six Sigma–DMAIC 2 | 15 | 53.6% | 10 | 35.7% | 8 | 28.6% |

| Respondent MBTI Profiles | Choice of Project Manager MBTI for Successful Projects | Choice of Team Member MBTI for Better-Performing Projects | Choice of Team Member MBTI Regardless of Project Type | Undesired Team Member MBTI for Projects Requiring Fast and Successful Outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| ESTP * | 3 | 10.7% | 15 | 53.6% | 15 | 55.6% | 14 | 50.0% | 10 | 35.7% |

| ESTJ | 2 | 7.1% | 22 | 78.6% | 22 | 81.5% | 18 | 64.3% | 10 | 35.7% |

| ENFJ | 0 | 0% | 15 | 53.6% | 16 | 59.3% | 13 | 46.4% | 8 | 28.6% |

| ENTJ | 3 | 10.7% | 21 | 75.0% | 19 | 70.4% | 16 | 57.1% | 10 | 35.7% |

| ISTP | 2 | 7.1% | 12 | 42.9% | 13 | 48.1% | 11 | 39.3% | 9 | 32.1% |

| ISTJ | 3 | 10.7% | 13 | 46.4% | 19 | 70.4% | 19 | 67.9% | 7 | 25% |

| INFJ | 0 | 0% | 10 | 35.7% | 15 | 55.6% | 9 | 32.1% | 9 | 32.1% |

| INTJ | 3 | 10.7% | 13 | 46.4% | 18 | 66.7% | 16 | 57.1% | 8 | 28.6% |

| ESFP | 0 | 0% | 13 | 46.4% | 14 | 51.9% | 10 | 35.7% | 9 | 32.1% |

| ESFJ | 3 | 10.7% | 17 | 60.7% | 16 | 59.3% | 12 | 42.9% | 6 | 21.4% |

| ENFP | 0 | 0% | 11 | 39.3% | 16 | 59.3% | 13 | 46.4% | 11 | 39.3% |

| ENTP | 6 | 21.4% | 13 | 46.4% | 16 | 59.3% | 13 | 46.4% | 7 | 25.0% |

| ISFP | 1 | 3.6% | 9 | 32.1% | 13 | 48.1% | 8 | 28.6% | 12 | 42.9% |

| ISFJ | 0 | 0% | 10 | 35.7% | 14 | 51.9% | 8 | 28.6% | 8 | 28.6% |

| INFP | 0 | 0% | 11 | 39.3% | 15 | 55.6% | 9 | 32.1% | 16 | 57.1% |

| INTP | 2 | 7.1% | 11 | 39.3% | 16 | 59.3% | 14 | 50.0% | 10 | 35.7% |

| n | Correlation | 95% CI for ρ | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality tools useful for assessing and understanding individuals | 28 | 0.283 | (−0.108; 0.599) | 0.144 |

| Personality tools can help establish good-performing teams | 28 | 0.665 | (0.353; 0.844) | <0.001 |

| Project leaders focus on interpersonal skills, technical skills, and administrative skills of team members | 28 | 0.066 | (−0.315; 0.429) | 0.740 |

| Project leaders give more importance to team member relationships | 28 | 0.171 | (−0.219; 0.514) | 0.384 |

| Educating employees regarding personalities | 28 | 0.482 | (0.111; 0.735) | 0.009 |

| Training in different methods | 28 | 0.208 | (−0.183; 0.542) | 0.287 |

| Myers–Briggs® is enough for complete understanding of personalities | 28 | 0.186 | (−0.204; 0.526) | 0.342 |

| Myers–Briggs® tool used as a guiding tool | 28 | 0.407 | (0.024; 0.686) | 0.031 |

| Myers–Briggs® profile is the most qualified tool | 28 | 0.054 | (−0.326; 0.419) | 0.784 |

| Choosing team members dependent on the project type | 28 | 0.321 | (−0.069; 0.626) | 0.095 |

| Combining tools for better definition of personality types | 28 | 0.080 | (−0.303; 0.440) | 0.686 |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Personality tools | Personality tools useful for assessing and understanding individuals | 0.742 |

| Personality tools can help establish good-performing teams | 0.864 | |

| Educating employees regarding personalities | 0.709 | |

| Myers–Briggs® is enough for complete understanding of personalities | 0.850 | |

| Myers–Briggs® tool used as a guiding tool | 0.900 | |

| Tool combination | Combining tools for better definition of personality types | −0.796 |

| Training in different methods | −0.845 | |

| Myers–Briggs® profile the most qualified tool | −0.575 | |

| Team formation | Training in different methods | −0.612 |

| Choosing team members dependent on the project type | −0.693 | |

| Education | Project leaders focus on interpersonal skills, technical skills, and administrative skills of team members | −0.618 |

| Educating employees regarding personalities | −0.893 | |

| Myers–Briggs® profiles Team relationships | Myers–Briggs® is enough for complete understanding of personalities | −0.964 |

| Project leaders give more importance to team member relationships | −0.864 |

| Independent Variable | Coefficient | Hodge g (CI for η 1) | Adjusted CI for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality tools can help establish good-performing teams | 2.192 (0.411) * | 0.431 [95% CI: 0.000, 0.500] * | [95% CI: −0.107, 0.857] * |

| Educating employees regarding personalities | 2.961 (0.542) * | 0.483 [95% CI: 0.000, 0.500] * | [95% CI: 0.000, 0.821] * |

| Myers–Briggs® tool used as a guiding tool | 1.912 (0.687) * | 0.186 [95% CI: 0.000, 0.500] | [95% CI: −0.285, 0.678] |

| Constant 0.958 R2 = 0.435 F-ratio = 4.430 * n = 27 |

| n | Correlation | 95% CI for ρ | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project team members know where to go for assistance | 28 | −0.149 | (−0.496; 0.240) | 0.450 |

| Taking immediate actions | 28 | −0.097 | (−0.455; 0.287) | 0.622 |

| Problem-solving methods are used in projects | 28 | 0.371 | (−0.016; 0.661) | 0.052 |

| Deming Cycle used for process improvement | 24 | −0.109 | (−0.492; 0.309) | 0.612 |

| Deming Cycle is continuous process | 24 | 0.069 | (−0.344; 0.460) | 0.749 |

| The Eight Discipline Methodology used for recurrent problems | 24 | 0.160 | (−0.263; 0.531) | 0.956 |

| The Eight Discipline Methodology is a team-based approach | 23 | 0.121 | (−0.308; 0.509) | 0.455 |

| Five Whys is used for manufacturing problems | 25 | 0.078 | (−0.328; 0.459) | 0.711 |

| Five Whys make root cause definition | 25 | 0.526 | (0.137; 0.774) | 0.007 |

| Cause and Effect Analysis used as a quality control tool | 21 | −0.069 | (−0.487; 0.374) | 0.766 |

| Cause and Effect Analysis identifies causes of problems | 21 | 0.064 | (−0.379; 0.482) | 0.784 |

| Six Sigma used for roadmap projects or quality improvements | 17 | 0.364 | (−0.158; 0.727) | 0.151 |

| Six Sigma is a synonym for root cause analysis | 16 | 0.421 | (−0.118; 0.768) | 0.105 |

| Problem-solving benefits through increasing efficiency or project effectiveness | 28 | 0.569 | (0.220; 0.789) | 0.002 |

| Right problem-solving methods chosen for solving problems | 28 | 0.268 | (−0.124; 0.587) | 0.005 |

| Problem-solving methods prevent the problems from occurring or reoccurring | 28 | 0.231 | (−0.160; 0.560) | 0.153 |

| Problem-solving methods identify and remove occurred problems | 28 | 0.123 | (−0.264; 0.475) | 0.241 |

| Problems are solved completely and in a given time | 28 | −0.009 | (−0.381; 0.365) | 0.963 |

| Results published and distributed | 28 | 0.252 | (−0.139; 0.576) | 0.195 |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Problem solving impact | Problem solving benefits through increasing efficiency or project effectiveness | 0.880 |

| Right problem-solving methods chosen for solving problems | 0.622 | |

| Problem-solving methods prevent the problems from occurring or reoccurring | 0.792 | |

| Problem-solving methods identify and remove occurred problems | 0.794 | |

| Problem-solving methods | Project team members know where to go for assistance | −0.798 |

| Taking immediate actions | −0.817 | |

| Problem-solving methods are used in projects | −0.652 | |

| Project success | Taking immediate actions | 0.827 |

| Problem-solving methods are used in projects | 0.644 | |

| Problems are solved completely and in a given time | 0.564 | |

| Learning culture | Project team members know where to go for assistance | −0.778 |

| Results published and distributed | −0.776 |

| Independent Variable | Coefficient | Hodge g (CI for η 1) | Adjusted CI for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem-solving methods are used in Projects | 0.170 (1.350) * | 1.360 [95% CI: −1.500, −1.000] * | [95% CI: −1.821, −0.821] * |

| Five Whys make root cause definition | 2.144 (0.719) * | 0.544 [95% CI: −0.000, 0.500] * | [95% CI: −0.014, 0.894] * |

| Problem solving benefits through increasing efficiency or project effectiveness | 1.320 (0.930) * | 0.424 [95% CI: −0.500, 0.000] * | [95% CI: −0.821, 0.071] |

| Right problem-solving methods chosen for solving problems | 0.730 (1.090) * | 1.522 [95% CI: −2.000, −1.000] * | [95% CI: −2.035, −1.000] * |

| Constant 0.380 R2 = 0.314 F-ratio = 2.63 * n = 27 |

| Respondents MBTI Profile | Use of Problem-Solving Methods in Teams | Training in Problem-Solving Methods | Choice of Method that Solves all Problems | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDCA | 8D | Five Whys | FMEA | Appreciative Inquiry | Cause and Effect Analysis | Kaizen | DMAIC | PDCA | 8D | Five Whys | FMEA | Appreciative Inquiry | Cause and Effect Analysis | Kaizen | DMAIC | PDCA | 8D | Five Whys | FMEA | Appreciative Inquiry | Cause and Effect Analysis | Kaizen | DMAIC | |

| ESTP n = 3 | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 3 100% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | ||||||||||

| ESTJ n = 2 | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 2 100% | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | |||||||||||

| ENTJ n = 3 | n = 2 70% | n = 3 100% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 3 100% | n = 2 70% | n = 3 100% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 3 100% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | ||||||||

| ISTP n = 2 | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | |||||||||

| ISTJ n = 3 | n = 3 100% | n = 3 100% | n = 3 100% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 3 100% | n = 3 100% | n = 3 100% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 3 100% | n = 3 100% | n = 3 100% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | |||

| INTJ n = 3 | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | ||||||

| ESFJ n = 3 | n = 1 30% | n = 3 100% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | n = 2 70% | |||||||||

| ENTP n = 6 | n = 5 80% | n = 3 50% | n = 3 50% | n = 4 70% | n = 2 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 30% | n = 4 70% | n = 3 50% | n = 3 50% | n = 2 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 30% | n = 2 30% | n = 2 30% | n = 2 30% | n = 3 50% | n = 1 30% | n = 2 30% | n = 1 30% | n = 3 50% | |||

| ISFP n = 1 | n = 1 100% | n = 1 100% | n = 1 100% | n = 1 100% | n = 1 100% | n = 1 100% | ||||||||||||||||||

| INTP n = 2 | n = 2 100% | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 2 100% | n = 2 100% | n = 1 50% | n = 1 50% | n = 2 100% | ||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maric, A.; Cajner, H. Effects of Personality Type Tools and Problem-Solving Methods on Engineering Company Project Success. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411185

Maric A, Cajner H. Effects of Personality Type Tools and Problem-Solving Methods on Engineering Company Project Success. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411185

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaric, Anamarija, and Hrvoje Cajner. 2025. "Effects of Personality Type Tools and Problem-Solving Methods on Engineering Company Project Success" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411185

APA StyleMaric, A., & Cajner, H. (2025). Effects of Personality Type Tools and Problem-Solving Methods on Engineering Company Project Success. Sustainability, 17(24), 11185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411185