Abstract

Digital transformation is reshaping work and management, yet evidence on how technological innovation interacts with workplace well-being, leadership, organizational culture, and human-centered management remains fragmented. This study aims to integrate these strands of research by examining how innovation and digitalization affect employee well-being and motivation in organizational contexts. A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines, with a protocol registered on INPLASY. The search was performed in the Scopus database and identified 287 eligible studies (1989–February 2025). Bibliometric keyword co-occurrence analysis using VOSviewer (1.6.20), combined with qualitative content and thematic analysis, led to five clusters: (1) innovation and well-being; (2) leadership pathways to workplace well-being; (3) work motivation and job satisfaction; (4) human-centered management in technological progress; and (5) organizational culture. The results show that organizations reconciling innovation and people’s well-being tend to adopt leadership styles and cultures grounded in ethical values, inclusion, psychological safety, and balanced work demands and resources, operationalized through human-centered management practices. These findings offer an integrated framework that goes beyond an instrumental view of technology and provide guidance for leaders, HR professionals, and policymakers designing digital transformation strategies that foster responsible innovation and promote sustainable, health-promoting work environments.

1. Introduction

Digital solutions aimed at enhancing well-being have emerged as important tools for improving employees’ quality of life. Such platforms not only help reduce stress and anxiety but also promote more sustained states of everyday well-being [1]. This shift reveals a growing tendency for automation and digital tools to transcend their traditional role as mere productivity instruments, becoming increasingly recognized for their human and subjective impact in shaping healthier and more sustainable work environments [2].

As environmental concerns gain prominence, strategic business leaders are assuming a crucial role in driving innovation. When sustainability-oriented entrepreneurial orientation is combined with effective resource management, it can enhance both product and process eco-innovation [3]. The implementation of such practices reflects not only a modern leadership approach committed to sustainable management, but also provides firms with a competitive advantage in the face of future challenges [4]. The ability to make informed decisions that integrate environmental performance, technological innovation, and efficient resource use is fundamental to transforming sustainability into tangible organizational value and to improving worker well-being [5,6].

Technological innovation has proven pivotal in increasing motivation and job satisfaction while simultaneously contributing to the creation of organizational environments that are more conducive to performance and employee well-being [7]. Several studies indicate that merely meeting salary expectations is not sufficient to foster innovation [8,9]. Rather, when employees perceive real opportunities for career development and well-being enhancement, they become more willing to contribute innovative ideas and practices [8], reinforcing organizational commitment and social responsibility [10,11].

Another critical aspect is incorporating human factors into the development of artificial intelligence (AI) systems, which is essential to understanding the social, psychological, and organizational impacts of these technologies. This underscores not only the urgency of embedding ethical and human-centered principles throughout the design and implementation cycle, but also the importance of ensuring that such systems are developed to respect human values, build user trust, and foster collective well-being [12,13]. Accordingly, the ethical integration of AI is a crucial condition for ensuring sustainability, equity, and legitimacy in its use across organizational and societal contexts [13]. Technology management guided by human-centered principles is thus not only an ethical requirement but also an essential strategy for ensuring sustainable productivity and maintaining a dynamic balance between technological progress and human needs [3,14,15].

A deliberate organizational culture can enhance employee well-being and play a decisive role in fostering innovation, suggesting that organizations must develop capabilities for resilience to adapt to market and societal disruptions and effectively pursue environmental goals [16]. A culture of knowledge sharing, and effective management practices drives performance, well-being, and organizational success by significantly influencing engagement and behaviour; it encourages creativity and innovation and lowers turnover intentions [9] while also reducing burnout through equitable and respectful interactions [17,18].

In this context, the present study examines how technological innovation affects employee well-being and motivation, and how it interacts with leadership, organizational culture, and human-centered management within organizational strategies. Based on these components, we propose a conceptual analytical model to help future researchers benefit from the findings of this systematic literature review (SLR), identify gaps requiring further inquiry, and receive guidance for future research directions. Although various studies on technology, leadership, organizational culture, and well-being exist in the literature, they often end up being presented in isolation. By integrating these themes, this study generates a holistic view of human sustainability in the digital context. Furthermore, the study advances by overcoming the instrumental view of technology and emphasizing its social impact, effect on well-being, and role in building inclusive and ethical cultures. Its originality lies in the interdisciplinary approach that surpasses the instrumental view of technology, in the articulation between psychosocial mechanisms and innovation, and in the construction of a conceptual model that clarifies how leadership practices and inclusive culture relate to well-being and responsible innovation in digitized contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

In this context, the present study examines how technological innovation affects employee well-being and motivation, and how it interacts with leadership, organizational culture, and human-centered management within organizational strategies. This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) recommendations to ensure transparency, scientific rigor, and reproducibility. The review protocol was previously registered on the INPLASY platform (International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) (Milwaukee, WI, USA) under DOI number 10.37766/inplasy2025.10.0101 and is available as Supplementary Materials. Registering the protocol on international platforms such as INPLASY offers several advantages, such as: transparency, by ensuring that the objectives, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and analysis methods are defined in advance, avoiding biases during the process; Traceability, as it allows all stages of the review to be documented, making it auditable and reproducible; scientific visibility, increasing the credibility of the review, since it is validated in an internationally recognized database; reduction in duplication of efforts, since researchers can check similar protocols and align investigations; greater acceptance in scientific journals, as it reinforces methodological robustness and reviewer confidence [19].

The SLR follows the PRISMA workflow steps described below by [20]. Thus, we began by identifying the need to conduct a systematic review, as there was a gap in the literature, since this is a topic that, although explored, does not bring together all the components in a single study. Observing the methodological criteria of step 1, the Scopus database was defined as a multidisciplinary database with international data collection.

The Scopus database was chosen for the following reasons: (i) it offers the broadest multidisciplinary coverage among indexing databases, including journals with high editorial rigor in the areas of management, organizational behaviour, and technological innovation (it includes more than 25,000 peer-reviewed journals, allowing it to capture both established and emerging literature). As the theme involves innovation, leadership, well-being at work, and management, Scopus is particularly strong in management and business, organizational psychology, technology and innovation, and applied social sciences. (ii) Scopus uses rigorous indexing criteria, with continuous evaluation by independent committees, which ensures traceability, periodic updates, and exclusion of low-quality journals. (iii) Tools such as VOSviewer, CiteSpace, and Bibliometrix are fully optimized for data extracted from Scopus, which improves data cleansing, reference standardization, and the accuracy of co-occurrence maps. (iv) Although they accept articles in several languages, Scopus has a strong predominance of publications in English, reducing the problems of linguistic heterogeneity in bibliometric analyses.

Although methodological recommendations generally highlight the need to search multiple databases to maximize the comprehensiveness of systematic reviews, this study relied exclusively on the Scopus database for the initial identification of records. This decision was grounded in the previous described reasons and in evidence showing that, in certain domains and clearly delimited research questions, a single database can retrieve most relevant studies, with only marginal gains resulting from the addition of further sources [21,22]. Prior research also demonstrates that specific bibliographic databases offer superior and consistent coverage across various fields, supporting pragmatic decisions to reduce the number of sources when adequately justified [23]. Moreover, rapid review guidelines acknowledge that, under time or resource constraints, streamlined strategies, including searching a single database combined with complementary mechanisms, are methodologically acceptable, if transparency and active bias mitigation are ensured [24]. To minimize potential omissions, complementary backward and forward citation-chasing strategies were performed, which are recognized in the literature as effective in retrieving studies not captured in the initial electronic search [25,26]. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that relying on a single database introduces a selection bias, particularly given that the search was restricted to studies published in English. Therefore, we recommend that future updates expand the search to additional databases and gray literature to strengthen the robustness and comprehensiveness of the synthesis [21,24]. Complementing the review protocol, keywords in English were defined and used, as it is the universal language of the academic and scientific community. The search used the following query: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“well-being” AND innovation AND organization) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “SOCI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “BUSI”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “re”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)). The screening process was conducted by two independent reviewers. Screening began after achieving at least 75% agreement between reviewers in a pilot test applied to a sample of ten articles to ensure consistency in the application of the criteria. In case of discrepancies, a third reviewer was consulted to resolve conflicts.

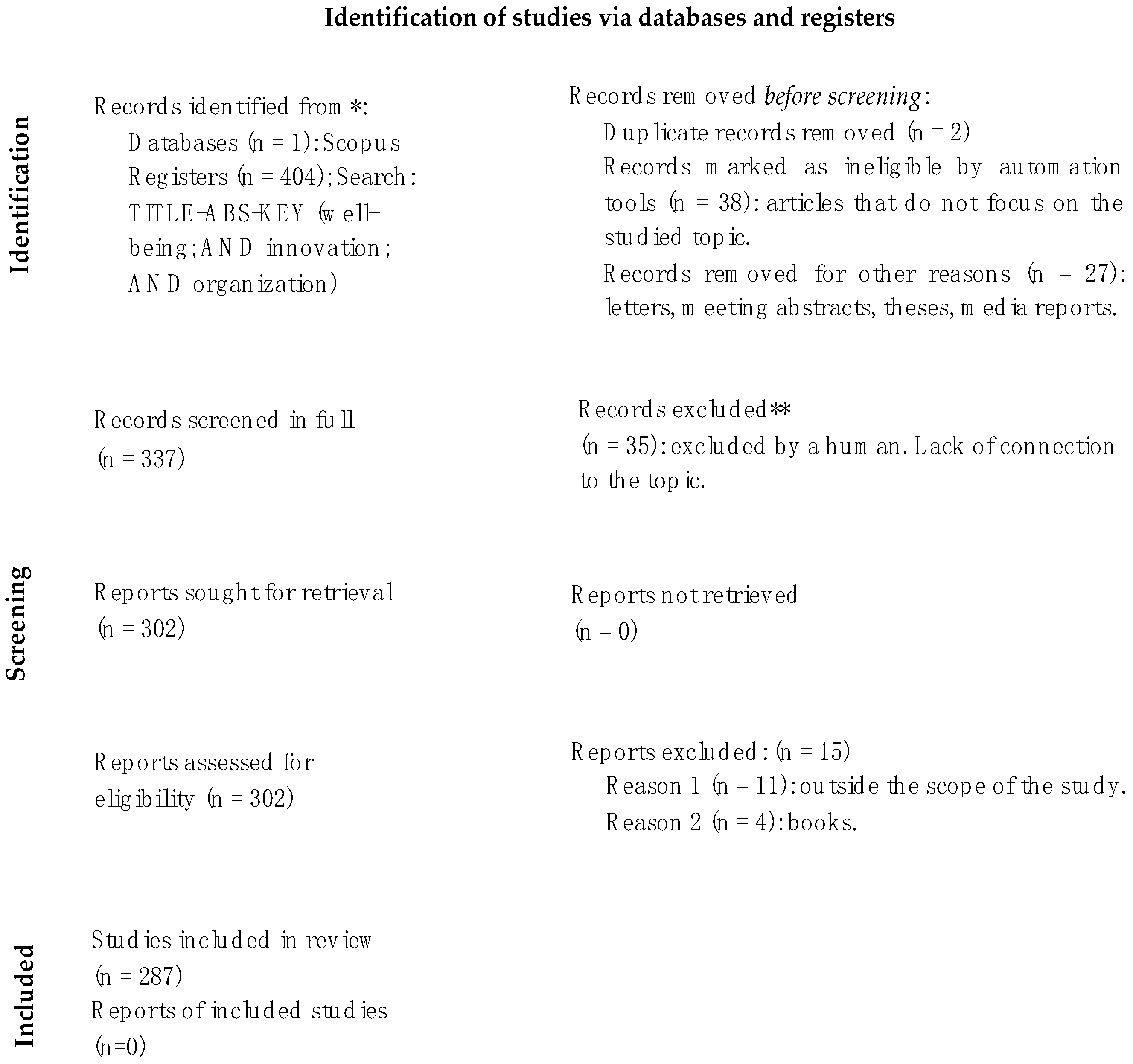

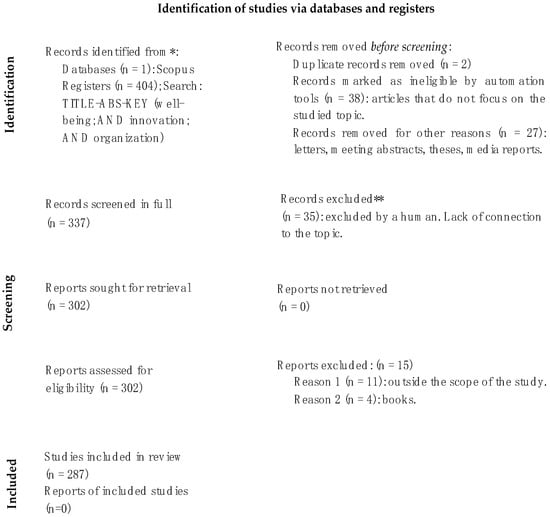

The systematic search in the database was conducted on 14 February 2025, the deadline for inclusion of the analyzed studies. The mention of 2025 in the text refers, therefore, to the effective date of data collection and not to a projection of future publications (404 results were identified in Scopus). Records removed before screening included duplicate records (n = 2), records flagged as ineligible by automation tools (n = 38), articles not addressing the topic under investigation and records removed for other reasons (n = 27), such as letters, conference abstracts, theses, and media reports, leaving 337 studies. Of these, 35 were excluded by the reviewers after abstract screening due to lack of relevance to the research topic. The remaining 302 studies were read in full and evaluated by two independent reviewers, resulting in the exclusion of an additional 11 studies for being outside the scope of the review and four others for being books. Inter-rater agreement was substantial (κ = 0.74; 95% CI: 0.68–0.81). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus with a third reviewer. The final number of studies included in the review was 287 (Figure 1), and classified according to keyword analysis, using the VOSviewer software.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow Diagram 2020. Records identified from databases (*) represent records retrieved before duplicate removal; records excluded (**) refer to records excluded by human reviewers during title and abstract screening.

The inclusion criteria were (1) peer-reviewed scientific articles; (2) papers presented at conferences; (3) original studies (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods); (4) reviews, such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses; (5) studies published in English, without date restriction. The following were excluded: (1) letters, meeting abstracts, theses, media reports, content feeds; (2) articles that do not focus on the studied topic; (3) essays or opinions; (4) books.

To assess the quality of the studies and minimize the risk of bias, two reviewers independently evaluated the risk of bias: for qualitative articles, we used the guidelines defined by [26]; for quantitative articles, we used the approach described by [27]; and for systematic review articles, we applied the AMSTAR-2 tool [28], although tools such as JBI, NIH, or RoB 2 provide robust alternatives for appraising observational and experimental study designs, the critical assessment revealed meaningful heterogeneity in the distribution of methodological quality across design clusters. Qualitative studies demonstrated greater internal robustness, with two-thirds rated as high quality. In contrast, cross-sectional quantitative studies were predominantly classified as moderate quality, reflecting typical limitations of this design, such as the absence of temporal control. Cohort studies showed an intermediate profile, with a predominance of moderate risk of bias according to the criteria assessed. Systematic reviews exhibited the greatest variability, with ratings ranging from high to low quality. The narrative synthesis explicitly considered the risk of bias. Studies rated as low quality contributed only to contextualization and not to central claims. This differentiated distribution guided the synthesis process, which assigned greater interpretive weight to studies judged as having lower risk of bias within each cluster.

In the bibliometric analysis stage, specific clustering criteria and a minimum threshold for keyword co-occurrence were adopted, based on methodological recommendations previously used in similar studies. To ensure the reproducibility of the process, we established (i) a minimum of five keyword occurrences for inclusion in the network, (ii) the choice of the normalization method (association strength), and (iii) for thematic cluster identification, VOSviewer employs the proprietary VOS clustering algorithm developed by [29], which optimizes a quality function specific to the VOS method. It is important to note that this procedure does not correspond to the Louvain algorithm nor to its variants (e.g., Leiden). To ensure semantic consistency, we implemented a thesaurus of equivalences that merged common conceptual variants (e.g., well-being/wellbeing, organization/organisation, AI/artificial intelligence, HR/HRM/HRIS). Terms occurring fewer than two times were removed. This process reduced the vocabulary to a stable and interpretable set suitable for clustering and thematic modeling analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Overview

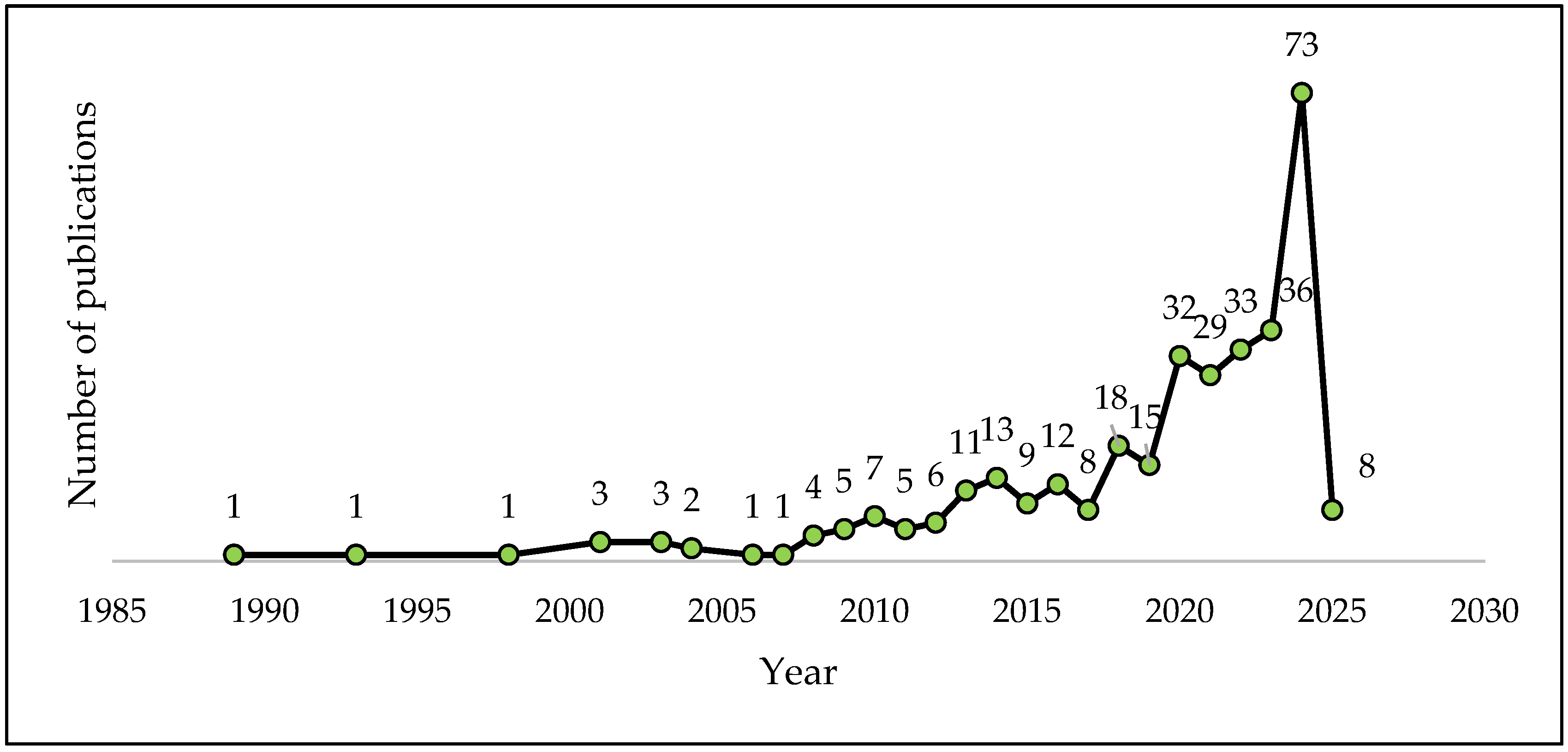

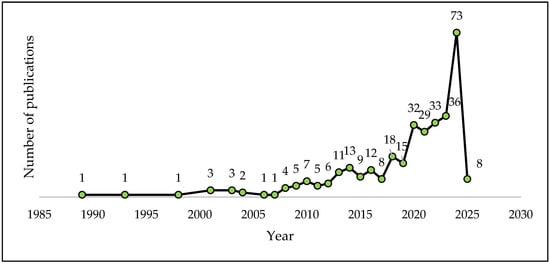

This section examines trends in publication and citation volumes, leading institutions and producing countries, outlet journals, core research methodologies, and the field’s most-cited articles and authors. Annual publication counts (Figure 2) remained minimal through the mid-2000s, increased steadily from 2007 to 2017, and then shifted to a higher plateau from 2018 onward, culminating in a peak in 2024 (58 papers). The low value for 2025 (4) reflects partial-year coverage.

Figure 2.

Number of annual publications.

Analysis of publishing outlets (Table 1) shows that Sustainability (Switzerland), with 12 publications, and the European Journal of Innovation Management, with 6 publications, are the most prominent venues. Nonetheless, the topic is disseminated across a wide range of journals, many with an interdisciplinary perspective, underscoring the breadth and cross-disciplinary relevance of the field.

Table 1.

Main journals according to number of publications.

Table 2 lists the most-cited contributions. The citation counts presented are raw and global. This criterion favors older articles, those from fields with higher citation intensity, or those published in higher-visibility journals, thereby introducing temporal and disciplinary bias. Led by Iansiti and Levien [30] with 1288 citations, followed by two highly influential studies by Ostrom et al. [31,32] with 1141 and 1132 citations, respectively. These studies represent core references shaping the field. Iansiti and Levien [30] introduced the concept of a “business ecosystem”, a biological metaphor applied to strategic management and innovation. They argue that organizations do not compete in isolation but rather within interdependent, value-creating networks composed of companies, suppliers, customers, and other actors. The studies led by Ostrom and colleagues [31,32] are fundamental in-service research and human-centered management. They consolidated the concept of value co-creation—that is, value is created not only by the company itself but also through interaction with employees, customers, and other stakeholders.

Table 2.

Most cited articles.

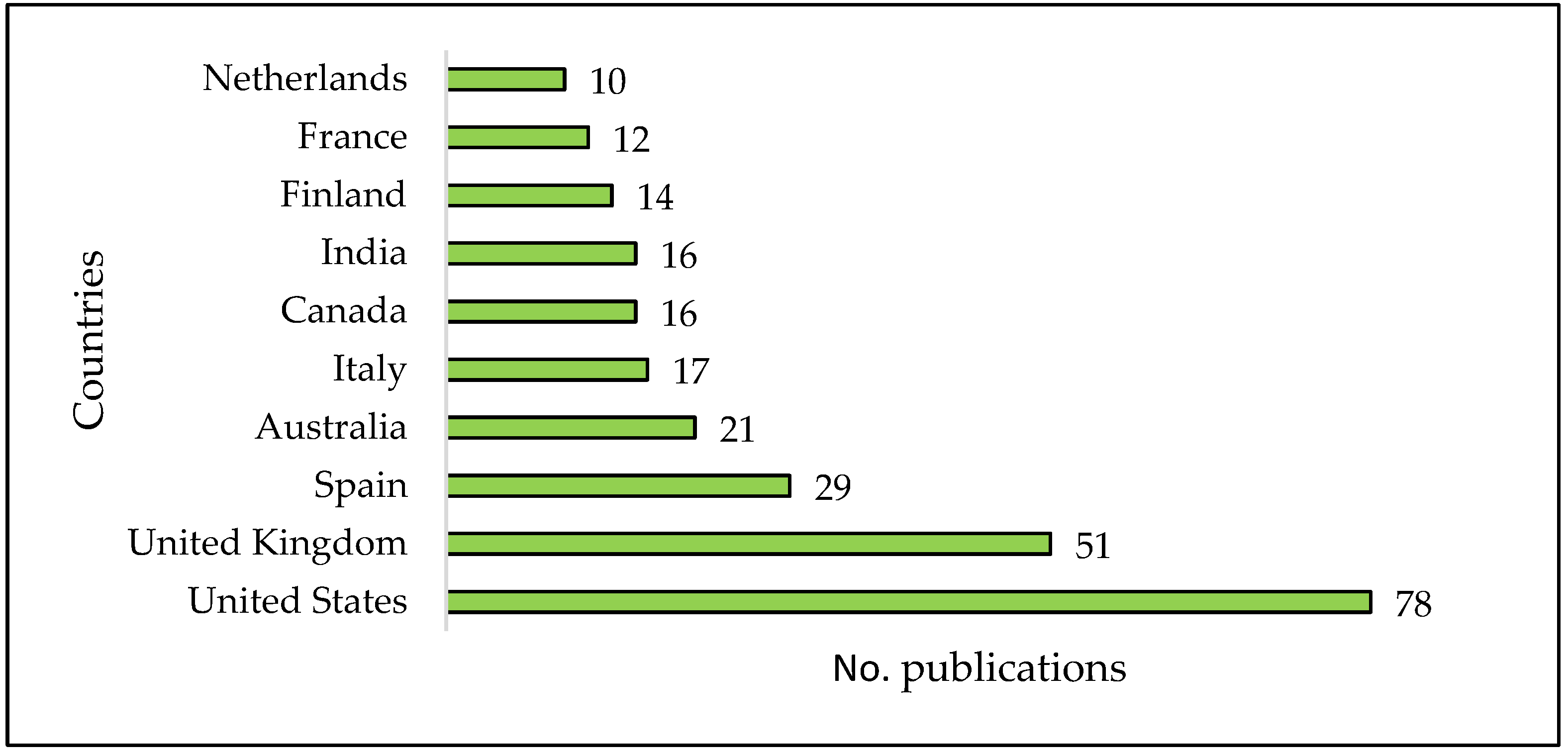

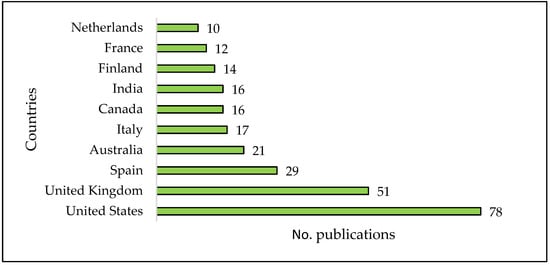

The geographical distribution of publishing outlets (Figure 3) indicates that the United States (78 publications) and the United Kingdom (51 publications) clearly dominate the field. This pattern underscores the pivotal role of these countries in shaping scholarly discourse and advancing research in this area. Both the US and the UK have a long tradition of research in management, organizational psychology, and leadership, with highly recognized universities and research centers (e.g., Harvard, MIT, Oxford, LSE). The US and the UK also tend to have more individualistic and distinctive organizational cultures for innovation, which is reflected in their research agendas. Furthermore, management practices of Anglo-Saxon origin have become a global reference since the post-war period through the globalization of multinational companies and business schools.

Figure 3.

Countries with the highest number of publications.

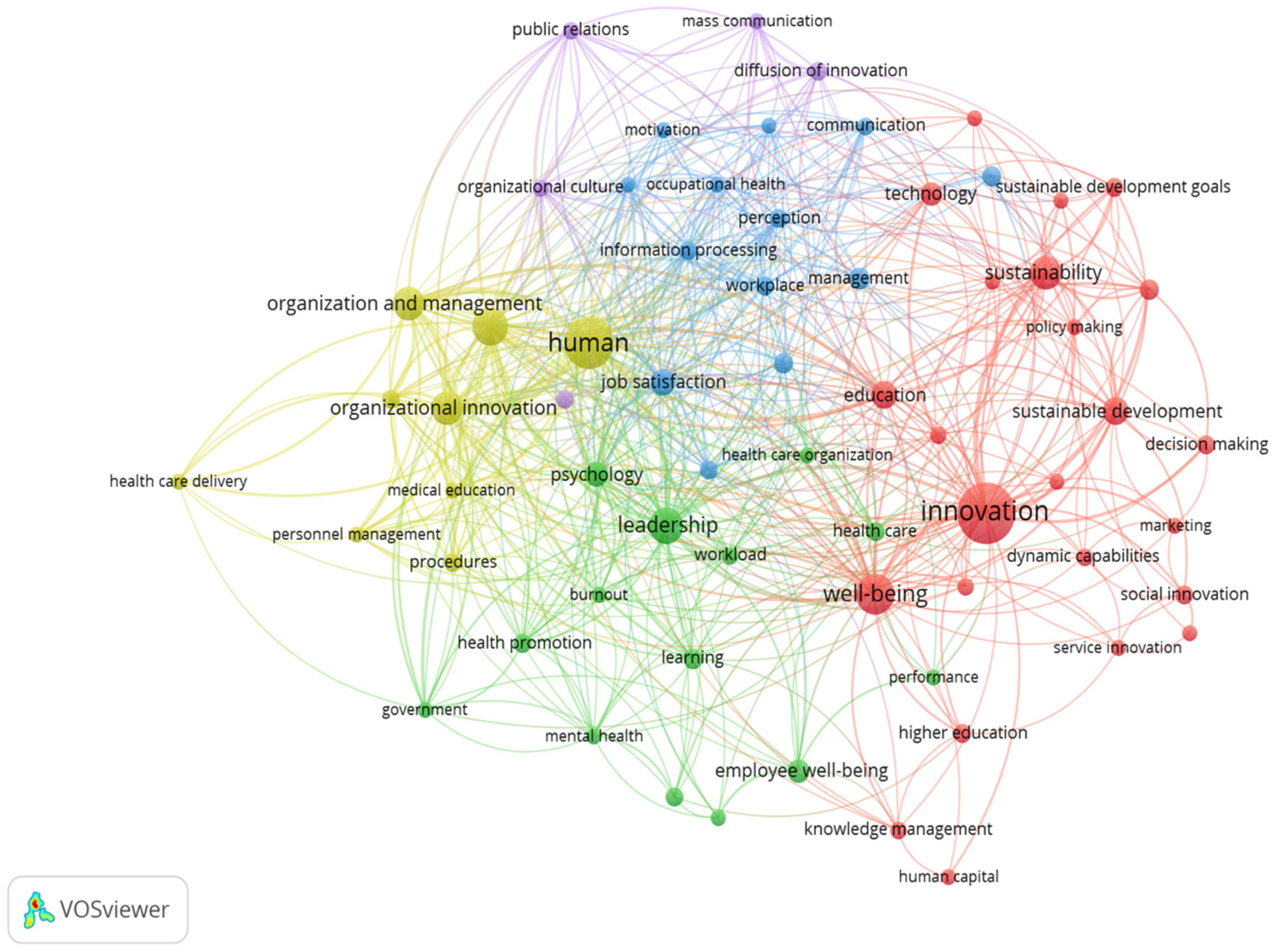

3.2. Analysis of Keyword Co-Occurrence and Formation of Thematic Groups

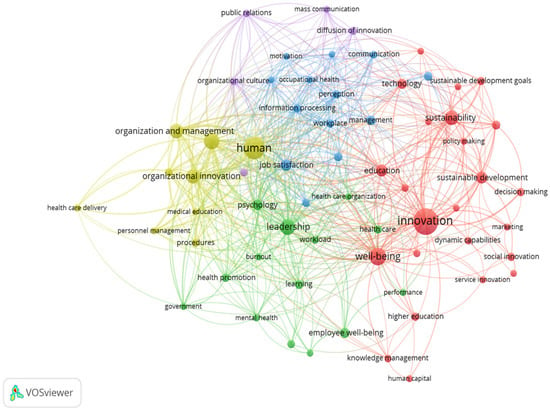

After selecting the articles, the second stage was carried out, which consisted of applying the bibliometric technique of co-occurrence of authors’ keywords. In this analysis, the unit of observation is the article itself, with the terms present in the title, abstract, and keywords of the 287 documents considered as variables. The technique is based on identifying the co-occurrence of terms, allowing the generation of a relational map that highlights the associations between different terms and their organization into clusters. The terms were extracted using the VOSviewer software, which calculates the strength of association between them based on the distance represented on the map: the stronger the relationship between two terms, the smaller the distance between them. To form the clusters, the software produces a colored diagram, in which each color corresponds to the concentration of terms belonging to a given cluster. Thus, articles that have the same colors share greater co-occurrence between their terms than those represented by different colors [35]. We adopted the binary counting method, widely used in previous studies, which considers the simple occurrence of a term in multiple documents. The application of this method resulted in the identification of 9143 terms. After verifying the eligibility of the full texts (n = 287 documents), published between 1989 and February 2025, the clusters related to the emerging thematic terms were identified. Next, a criterion of five minimum occurrences was defined, which reduced the set to 187 eligible terms. Finally, VOSviewer automatically selected the most relevant terms, returning a final total of 82 cases [36]. The map presented in Figure 4 illustrates the relationships between the terms and their associations within the thematic clusters. The resulting network consists of five clusters.

Figure 4.

Co-occurrence map analysis.

Consistent with the objectives of the present SLR and through the VOSviewer Weight <Total Link Strength> analysis (analysis in ascending order of numerical values), we performed content and thematic analyses of the studies. The qualitative coding of the clusters derived from VOSviewer followed a hybrid content-thematic approach that combined inductive strategies (identifying themes emerging from the material) and deductive strategies (applying pre-existing theoretical categories related to workplace well-being and innovation). The primary units of analysis were the items represented as nodes in each map (e.g., publications, keywords, authors, or institutions, depending on the specific network), complemented by examination of the corresponding titles, abstracts, and main findings. Coding was conducted independently by two researchers. The codebook was developed iteratively: following an exploratory review of the clusters generated by VOSviewer’s proprietary clustering algorithm, preliminary thematic categories were assigned, discussed, and refined until consensus was reached. Inter-coder reliability, calculated on a subsample of studies, was satisfactory (Krippendorff’s alpha α = 0.82), indicating high agreement between coders. Residual disagreements were resolved through discussion, ensuring that the final cluster interpretations were both data-driven and aligned with the conceptual focus of the study.

As an illustrative example, within the “Innovation and Well-Being” cluster, VOSviewer grouped terms such as well-being, mental health, workload, innovation, organizational innovation, service innovation, and performance. Building on these terms and on the information extracted from the corresponding article abstracts, we coded core concepts that capture how employees feel and function at work (e.g., workplace well-being, strain, resilience) and how they contribute to innovation (e.g., innovative behaviour, creativity). These codes, together with those related to motivation and job satisfaction (Cluster 3), support the interpretation that workplace well-being enhances motivation and job satisfaction, which in turn foster higher engagement and innovative behaviour. Accordingly, we formulated a proposition stating that workplace well-being is positively associated with employees’ innovative behaviour, with this relationship being mediated by employees’ motivation, satisfaction, and engagement.

Thematic groups emerged from this recognition: (1) Innovation and well-being (Cluster 1, red); (2) Leadership pathways to workplace well-being (Cluster 2, green); (3) Work motivation and job satisfaction (Cluster 3, blue); (4) Human-centered management in technological progress (Cluster 4, yellow); and (5) Organizational culture (Cluster 5, purple). In the subsequent sections, each of these clusters is examined in detail, with a focus on the predominant themes, conceptual patterns, and key findings of the studies grouped within each cluster. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of how the literature in each thematic domain has evolved and how these domains collectively inform the broader field.

3.2.1. Innovation and Well-Being (Cluster 1, Red)

Digital innovation is profoundly transforming the socio-technical architecture of work, producing heterogeneous but globally promising effects on the quality of work life. On the one hand, technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and algorithmic management are redefining central human resource management decisions, including recruitment, performance evaluation, and time planning, while raising concerns about privacy, bias, and discrimination, as well as the risk of widening skills gaps among less adaptable workers [37]. On the other hand, the spread of digital services has been associated with macroeconomic growth and community well-being, especially in developing contexts, with indirect effects on frontline workers, as customer incivility tends to decrease when interactions become mediated or partially protected by digital technologies [38].

Several lines of research mechanically explain how digital technologies influence the quality of work life. First, the integration of AI into human resources (HR) processes allows for continuous detection of engagement and affect, enabling more timely and personalized interventions [39]. Second, digital HR infrastructures, such as HR information systems (HRIS), enhance fundamental work resources—such as clarity of expectations, feedback, and development opportunities—promoting engagement and well-being [40]. Third, specialized tools, such as Building Information Modeling, strengthen coordination, reduce rework, and decrease stress, increasing predictability and shared understanding, especially when introduced gradually through clear guidelines and pilot projects [41].

The benefits of digitalization also extend to the task and work environment levels. Activity-based work environments, when strategically designed, tend to improve satisfaction and perceived fit among employees [42]. Wearables and smart textiles offer ergonomic gains and reductions in injuries, connecting digitalization to physical well-being [43]. “Bring Your Own Device” (BYOD) policies, if managed carefully, can reinforce autonomy and perceived control, contributing to greater satisfaction, performance, and organizational commitment [44]. Digital mental health applications, in turn, provide accessible and scalable emotional support, reducing suffering and stabilizing positive affects in daily life, transforming automation into a tool for human support, and not just productivity [1]. Added to this picture is evidence that organizational cultures that promote curiosity, creativity, and clarity tend to sustain successful innovative processes and, simultaneously, higher levels of quality of life at work [45,46].

However, the risks are not negligible. Technostress is a consistent predictor of decreased psychological well-being among workers and students [47,48]. AI-induced job insecurity compromises the psychological contract, reducing trust and engagement [8]. In the education sector, accelerated digital transitions have revealed inequalities in equity and capacity—namely between rural and urban areas and between levels of digital competence—deteriorating well-being and performance when institutional support is insufficient [49,50,51]. Other socio-technical vulnerabilities, including cognitive overload, manipulation, and new vectors of intrusion, indicate that technology can simultaneously increase efficiency and expose workers to emerging psychosocial risks [18]. Such observations converge with sustainability perspectives that advocate adaptive governance to mitigate the social and environmental externalities of ubiquitous digitalization [52].

The literature also highlights the existence of contingencies and non-linear relationships. Employees’ expectations regarding performance and well-being directly influence their predisposition to support digital transformation processes, demonstrating that perceptions and change management strategies are as decisive as the technologies themselves [53]. It is crucial to note that the relationship between technological innovation and psychological well-being can assume an inverted U-shaped pattern: moderate levels of innovation enrich resources and meaning, while excessive and poorly planned changes erode well-being [54]. Along these lines, the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model constitutes an integrative lens, suggesting that digitalization can both expand resources—such as autonomy, feedback, and collaboration—and intensify demands—such as cognitive overload and uncertainty; the final effect on the quality of work life therefore depends on the balance between the two [46]. At the organizational and ecosystem levels, innovation, competitiveness, and social well-being mutually reinforce each other when continuous investments in research, development (R&D), and training are maintained [55,56,57,58]. Entrepreneurial ecosystems that value creativity and continuous improvement often incorporate well-being as a driver and outcome of innovative growth [59]. Still, innovative HR practices can generate trade-offs between the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of work; in these cases, the quality of work life plays an essential mediating role in relation to performance, requiring careful planning and monitoring [60]. Research in ergonomics and human factors reinforces this need, advocating preventive attention to the structural impacts of automation and the design of human, safe, and sustainable work [61].

Sectoral examples illustrate these dynamics. In civil construction, the phased adoption of BIM has demonstrated complementarities between efficiency and well-being [41]. In the health and public services sectors, co-creation processes with users, especially older people, have improved service value and well-being outcomes [57,62]. Cultural organizations that innovate for aging audiences reveal how inclusive and human-centered practices can convert digital and organizational creativity into intergenerational well-being benefits [63]. Across all sectors, alignment between digital projects, organizational strategy, risk management, and human performance remains central [14,64,65].

3.2.2. Leadership Pathways to Workplace Well-Being (Cluster 2, Green)

A growing body of evidence positions leadership not only as a contextual element of innovation, but as a primary antecedent of employee well-being, determining resources, climate, and changing trajectories. Agile leadership mindsets, for example, predict higher performance and innovative behaviour, and are also positively associated with well-being, especially increased vigor [66]. At the strategic level, leaders who articulate innovation with social and environmental objectives translate technological gains into broader forms of collective well-being. Dynamic capabilities, stakeholder engagement, and responsible governance make well-being a central outcome of sustainable innovation [67,68]. In this sense, instruments such as the Balanced Scorecard, when driven by visionary leaders, simultaneously operationalize sustainability (such as UN SDG 3) and economic objectives, institutionalizing health and well-being in everyday decision-making [11].

Despite conceptual diversity, multiple approaches to leadership converge on similar socio-psychological mechanisms. Authentic, inclusive, servant, spiritual, and health-promoting leadership styles promote psychological safety, reduce role ambiguity, and increase subjective well-being; these effects, in turn, enhance creativity and innovative performance [4,69,70,71]. Catalytic leadership explicitly reinforces an ethic of “safe error,” a critical element of innovative cultures and closely linked to psychological safety [12]. Leader-member exchange relationships enhance both innovative behaviour and well-being, being indirectly strengthened by job rewards [72]. Furthermore, perceived organizational support—derived from fair leadership behaviour and HR practices—continues to be a strong simultaneous predictor of well-being and performance [73]. In the healthcare sector, engaging leadership has been shown to reduce burnout and increase nurse engagement, highlighting the importance of leadership in contexts of high emotional demand [74]. Health-promoting leadership affects innovation both directly and indirectly, through psychological well-being and constructive conflict [71]. In parallel, transformational leadership mobilizes a shared vision and reinforces commitment, mitigating fatigue and burnout in high-pressure contexts [75], while inclusive leadership strengthens the recognition and psychological safety that underpin knowledge sharing and pro-social behaviours [76].

The relevance of leadership is equally critical in digital and green transitions. Successful digital transformation requires strong leadership, stakeholder engagement, and intentional communication, accompanied by explicit efforts to mitigate digital inequality, ensuring that well-being benefits are distributed equitably [77]. Hybrid leaders, who simultaneously invest in trust, skills development, and well-being safeguards, enable adaptive and people-centered change in times of uncertainty [14]. Managing remote work can also unlock creativity and access diverse talent pools, provided that leadership ensures adequate cohesion and support [78]. In the environmental domain, strategically entrepreneurial and resource-orchestrating leaders amplify green innovation, especially process innovation, converting sustainability into social and competitive value [5]. More broadly, digitally savvy and cross-sectoral leaders use data, service science, and inter-organizational collaboration to reshape systems with a view to social well-being [31,32,79,80,81].

At the team and micro-behavioral levels, leadership emotional competence and organizational climate management drive personal initiative and affective well-being that underpin innovation; conversely, intra-team conflict undermines these foundations [82]. Team climate may even outperform transformational leadership in predicting satisfaction in interprofessional care, although leadership remains fundamental to creating collaborative conditions that promote well-being and innovation [83]. Servant leadership strengthens psychological safety and flourishing, driving innovative behaviours through subjective well-being [70], while spiritual leadership cultivates integrity and harmony, promoting knowledge sharing in collectivist contexts and strengthening innovation [69,84]. Leadership development programs that foster ambidexterity—balancing exploration and execution—help teams navigate innovation paradoxes, simultaneously protecting social and well-being outcomes [85]. However, the literature also highlights important contingencies and warnings. Overly ambitious organizational aspirations in the public sector can stimulate radical innovation but deteriorate employee well-being [86,87]. Benevolent-patriarchal leadership models may generate initial stability and emotional security, but if not balanced with empowerment practices, they produce dependency, reduce autonomy, and can lead to stagnation, threatening creativity and increasing the risk of burnout and turnover [88,89]. In higher education, function overload and resource scarcity harm the well-being of leaders and the quality of decisions, compromising institutional innovation [90]. In crisis contexts, leadership that prioritizes human well-being while coordinating digital capabilities and responding flexibly to the market becomes necessary [91]. Finally, well-being-oriented leadership models advocate integrating task-focused and relationship-focused behaviours into selection, development, and evaluation systems, incorporating well-being as an explicit criterion of leadership effectiveness [92].

3.2.3. Work Motivation and Job Satisfaction (Cluster 3, Blue)

Innovation that sustains motivation and job satisfaction goes beyond the technological dimension, incorporating broader social and organizational transformations. At the societal level, innovation is characterized by the ability to respond to community needs, promote transdisciplinary collaboration, generate scalability, and create social, economic, and environmental value strengthens both problem-solving and civic development, stimulating employee engagement and adaptability [93]. In the organizational context, the combination of technological innovation and intrapreneurship fuels creativity, purpose, and professional fulfilment, especially when experimentation is encouraged, and the social impact of innovation is recognized and valued [7]. Evidence from the public sector reveals a similar pattern: innovation is driven less by financial incentives and more by relational conditions, such as career development opportunities and well-being support, indicating that a positive climate aligned with the aspirations of professionals is crucial for innovative behaviours and job satisfaction [8].

Human resource architecture plays a central role in channeling these dynamics towards sustainable performance. High-Performance Work Systems (HPWS) reinforce lasting results by promoting innovative behaviours and placing employee engagement and well-being as critical mechanisms [94]. HR management based on commitment strengthens intrinsic motivation, stabilizes innovative behaviours, and consolidates a positive culture congruent with organizational values [95]. Furthermore, well-being acts as an essential mediator between HPWS and performance [96]. At the team level, processes such as constructive conflict management, open expression of opinions, and “consideration of opinions” reinforce satisfaction and, subsequently, engagement [97]. The valuing of enthusiasm and learning agility on the part of managers—rather than exclusively formal credentials—aligns motivation with meaningful tasks and opportunities for growth [98]. The distinction between satisfaction and engagement is equally instructive: autonomy and challenge, more present among independent workers, increase engagement even when satisfaction levels are similar, linking innovative demands to the motivational quality of work [99]. Consistent attention to employee needs remains a decisive factor, influencing positive attitudes, motivation, and retention [100].

Technological and spatial design choices also shape these processes. Remote work tends to improve work–life balance and mental health, contributing to greater satisfaction and engagement [78]. In face-to-face contexts, interior design inspired by SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), combined with hybrid work policies, agile methods, and digital collaboration infrastructures, strengthens dignified, efficient, and innovative work practices [101]. However, technology only generates benefits when embedded in appropriate institutional capabilities and structures. The success of Building Information Modeling, for example, depends on the development of strategic competencies that integrate tools, structures, and teams [102]. Similarly, the adoption of HR Information Systems is associated with workplace well-being, which, in turn, drives engagement [40]. More broadly, institutional preparedness is crucial for the effectiveness of innovation; without this foundation, even promising advances can compromise motivation and competitiveness [103]. The motivational effects of innovation also manifest themselves in mission- and sustainability-oriented contexts. Organizations that co-create value with stakeholders and prioritize transparency and collaboration generate benefits that transcend profit, reinforcing collective and environmental well-being, as well as the sense of purpose of workers [10]. In the public sector, pro-environmental innovations developed by employees can stimulate engagement, but face resistance when sustainability is not fully integrated into routines, highlighting the importance of aligning discourse and practice to unleash creativity and satisfaction [104]. The development of community capacities—such as strengthening the data infrastructures of non-profit organizations to demonstrate impact—simultaneously enhances purpose and accountability, triggering positive motivational effects [105]. Implementation science adds that evidence-based innovations are more easily adopted when adapted to local values and made testable and observable, promoting professional and community satisfaction [106].

Sectoral evidence reinforces this logic. AI applications, especially natural language processing and text mining, have enabled health systems to identify research priorities, leadership mechanisms, professional well-being, and quality of care, aligning with broader organizational goals of motivation and satisfaction [107]. In parallel, technology supports improvements in products and services that enhance motivation and social outcomes, especially when supported by collaborations between the State and organizations [108].

Finally, regional development studies demonstrate that connected and functionally articulated innovation ecosystems strengthen local economies while improving the well-being of workers and communities [109]. Education and professional training also play a strategic role: integrating social entrepreneurship and innovation skills, such as problem mapping, into social work training empowers professionals to create impactful and ethically grounded solutions, aligning work with purpose and sustaining motivation [110]. Finally, innovation teams composed of diverse personality profiles expand the capacity for ideation and implementation, enriching the work environment and satisfaction [111].

3.2.4. Human-Centered Management in Technological Progress (Cluster 4, Yellow)

Human-centered management constitutes an integrative governance approach capable of guiding technological progress towards objectives of safety, usability, equity, and sustainable productivity [13,14]. In the specific domain of AI, the vast body of knowledge accumulated by ergonomics and human factors over several decades remains underutilized. The systematic incorporation of these principles into data-driven design and practices contributes to reducing the gap between development and implementation, while operationalizing ethics in daily work [13,112]. The relevance of person-centered design becomes even more evident in contexts with high user heterogeneity—such as the elderly population—which requires age-appropriate solutions, not merely digitized ones [50]. At the management level, personalized technological advances can evoke positive emotions and reinforce workers’ identification with the organization [3]. In the health sector, the integration between AI and health information literacy requires continuous training, critical thinking, and explicit ethical responsibility, essential elements for building safer, more autonomous, and less stressful clinical environments [113].

A practical, human-centered management agenda presupposes the deliberate alignment of work systems with a functional balance between people and technology, aiming for dignified, creative, and sustainable work practices [14]. Organizational structures that institutionalize flexibility, collaboration, and innovation facilitate the translation of this balance into routines and culture [15]. Empirical evidence shows that small and medium-sized enterprises that articulate technological innovation with consistent employee support have superior psychological indicators [54]. In crisis contexts, cross-sectoral and socially innovative collaborations, based on the development of shared narratives, can simultaneously protect community well-being and that of the workforce, without compromising productivity [114]. Ethical aspirations must also become operational: incorporating techno moral virtues into the daily practice of data science builds bridges between normative principles and concrete engineering decisions [112]. The increasing digitalization of work also requires adapting leadership styles and communication practices, with greater emphasis on clarity and emotional awareness, to sustain individual well-being in virtual environments [115].

Sectoral and policy-driven perspectives converge on the same guiding principle. In the agro-industrial complex, governance models that combine technological modernization with social and professional support tend to reduce inequalities, increase competitiveness, and strengthen the well-being of rural communities [116]. Ergonomic indicators anchored in sustainability principles provide organizations with measurable tools to align occupational health, decent work, and human development with technological adoption [117]. At the micro-organizational level, environments that promote authenticity—reducing self-alienation and allowing the expression of the “true self”—improve both well-being and performance, underscoring the psychosocial foundations of humanized technology management [118]. In parallel, operations management is gradually broadening its traditional focus, incorporating dimensions of sustainability and justice, especially in emerging economies, and more explicitly integrating the human, social, and environmental dimensions of productivity [34]. In the healthcare sector, organizational evidence demonstrates that perceived support and transparent communication during structural transitions reduce turnover and simultaneously increase motivation and proactive innovation, essential characteristics of people-centered technological and organizational change processes [119]. Translational linkages between research and care also contribute to improving the quality of care and patient well-being, highlighting the capacity of knowledge flows to humanize innovation in practice [120]. Finally, Finland’s political experience shows that participatory, human-centered innovation ecosystems—based on worker involvement, autonomy and well-being—can simultaneously increase productivity, job satisfaction and quality of life at work [121].

3.2.5. Organizational Culture (Cluster 5, Purple)

A growing body of evidence positions organizational culture as a central determinant of employee well-being and, consequently, the innovative capacity of organizations. The persistent conceptual and measurement gaps associated with “corporate burnout” illustrate the critical relevance of culture for prevention, sustainability, and performance [122]. In parallel, human resource management systems oriented towards support—which include compensation policies, job design, training, participation, and service quality—promote positive organizational climates associated with efficiency, innovation, and customer satisfaction [123]. Intentional cultural transformations that integrate mentoring practices, inclusive leadership, learning infrastructures, and participatory governance mechanisms reduce burnout and turnover, while strengthening professional growth in different organizational contexts [124]. From a functional perspective, psychological safety protects workers from the impacts of toxic leadership and facilitates knowledge sharing and collaboration [125], while curiosity translates leadership support into active engagement and problem-solving, weakening when such support is absent [126]. Cultures that cultivate resilience and innovation capabilities also exhibit better environmental performance [16]; simultaneously, knowledge-sharing norms and strong psychological contracts increase performance, creativity, and talent retention [9].

Boundary conditions and risk factors refine this culture–well-being–innovation relationship. Alignment between organizational values and professional identities reinforces a sense of belonging, excellence, and creativity, even when workers are exposed to the risk of overload to meet customer needs, despite low well-being [127]. While digital systems and AI-enabled human resources can increase productivity, they can also intensify technostress and depersonalization if designed without human-centered safeguards [39]. Organizational justice and respectful treatment consistently predict greater happiness at work [17]. Socially responsible organizations report lower levels of burnout and higher levels of radical innovation [128], while age-inclusive climates mitigate technostress and protect the mental health of older workers during technological transitions [129]. Structured innovation training improves employee experience and engagement [12]; similarly, cultures that explicitly prioritize mental health reduce intrusive cognitions that impair productivity and interpersonal relationships [18]. Inclusive practices also prove essential in both agile and remote startups [130] and educational systems, where autonomy, debureaucratization, and pedagogical leadership foster well-being and innovation [131]. Complementary mechanisms—such as wellness programs that reinforce perceived organizational support and affective commitment [132], internal marketing initiatives that reduce turnover [133], and leadership development that strengthens social cohesion [134]—operate within this cultural architecture. Nevertheless, High-Performance Work Systems (HPWS) can produce ambivalent effects on well-being, which underscores the need for context-sensitive assessments [135]. Psychological capital and personal accomplishment protect against burnout [136], while inclusive climates enhance satisfaction and creativity [137]. Additionally, holistic knowledge governance, by recognizing human values, promotes more inclusive academic cultures and simultaneously reduces organizational costs [138]. Sectoral and structural elements also come into play: non-profit organizations tend to cultivate healthier environments than public organizations [139], and the physical location of work proves to be only a weak predictor of culture and innovation when compared with the broader influence of socio-technical systems [78]. Converging evidence from healthcare reforms and community-based approaches further demonstrates that culturally sensitive governance, coupled with equity and stakeholder participation, improves well-being and fosters innovation [139,140,141,142,143,144].

4. Discussion

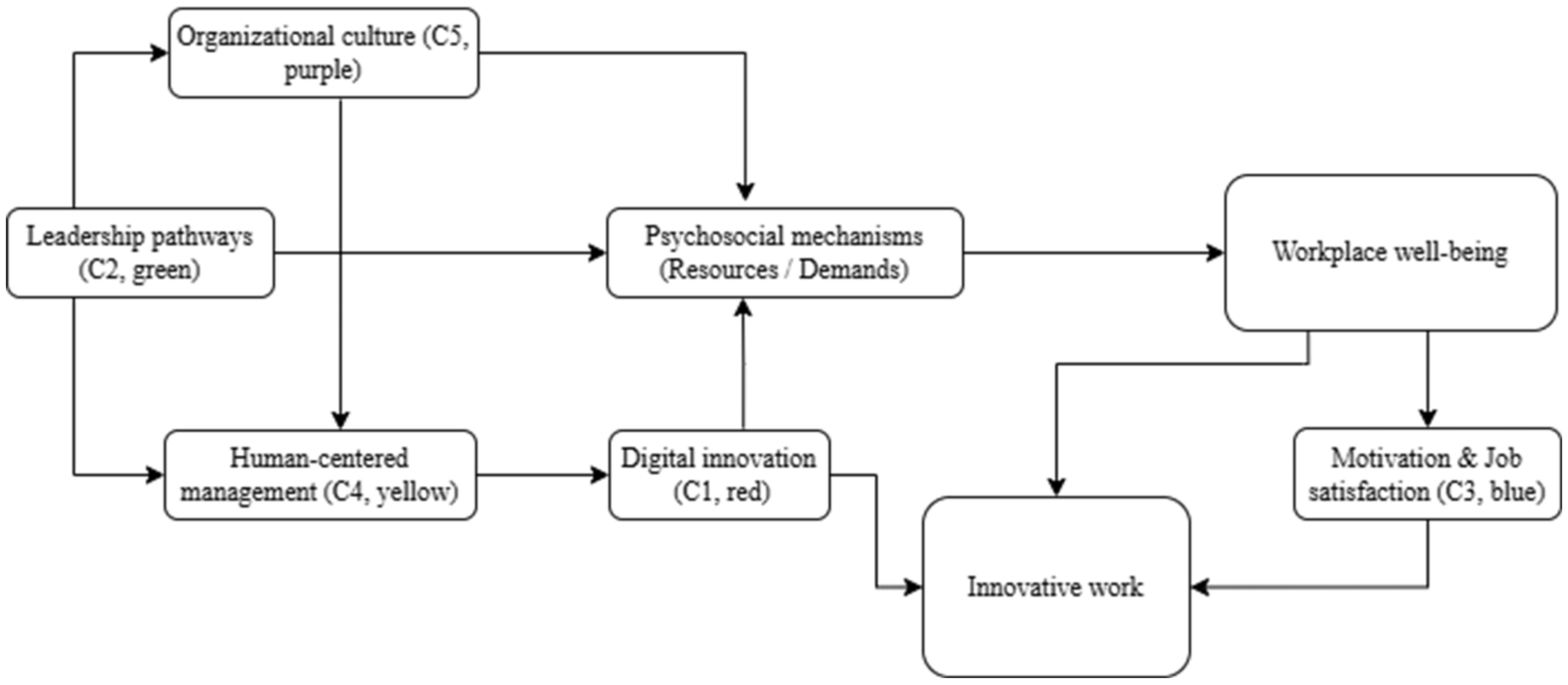

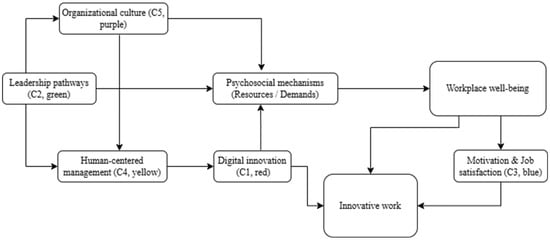

The conceptual model presented (Figure 5) was developed from a qualitative content analysis of the studies included in the SLR, empirically supported by the clustering (C1–C5) structures and co-occurrence networks generated with VOSviewer. These relationships provided the analytical and theoretical foundation for consolidating the proposed conceptual model, which synthesizes—integratively—the main axes of interaction emerging from the examined corpus. Workplace well-being may enhance innovative behaviour, consistent with the JD-R model, which posits that psychological and motivational resources promote engagement and performance [145,146], and with Conservation of Resources theory, which suggests that individuals with sufficient resources tend to invest in proactive behaviours, including innovation [147]. In addition, psychological safety [148] and a supportive organizational climate [149,150] strengthen this relationship, reinforcing the notion that positive work environments facilitate innovative behaviours [151,152].

Figure 5.

Conceptual model proposal.

Leadership is associated with higher levels of well-being, just as well-being appears consistently related to innovative behaviours. The literature suggests potential pathways between well-being and innovation. Most of the included studies present cross-sectional and correlational designs, which limits causal inferences. Thus, the relationships discussed refer to consistent associations observed in the literature, and not to established causal effects. The leadership → well-being → innovation chain should be interpreted as an emerging integrative theoretical model in the literature, and not as a proven causal mechanism.

The proposed model reflects an emerging theoretical framework, supported by the thematic convergence of studies, but lacks validation in longitudinal, experimental, or methodologically triangulated research. Leadership pathways (C2, green) and organizational culture (C5, purple) emerge in the literature as factors consistently associated with the psychosocial mechanisms of work—particularly the balance between resources and demands—and appear related to the promotion of human-centered management practices (HCM; C4, yellow). Human-centered management, in turn, is often described as a framework that guides quality, equity, and the pace of change, coinciding with organizational environments where digital innovation develops (C1, red). Digital innovation emerges in the analyzed studies as an element that relates both to psychosocial characteristics of work (e.g., autonomy, clarity, cognitive load) and to different forms of innovative work. Psychosocial mechanisms, in this context, are frequently identified as intermediary elements that articulate the associations between leadership, organizational culture, innovation, and well-being in the workplace. Similarly, well-being appears linked to two sets of outcomes: (i) direct associations with innovative behaviours and (ii) indirect associations via motivation and job satisfaction (C3, blue). Finally, the studies also describe a reciprocal relationship, suggesting that higher levels of innovative work tend to coexist with greater motivation and satisfaction, configuring a cycle interpreted in the literature as a cumulative process that can sustain innovative behaviour over time.

4.1. Leadership and Culture as Upstream Drivers of Human-Centered Management

Supportive leadership and organizational culture consistently emerge as antecedents of human-centered management. Inclusive, authentic, servant, transformational, spiritual, engaging, and catalytic leadership styles build psychological safety, clarity, fairness, and support. Conditions that make human-centered management feasible in practice [4,12,69,70,71,74]. In parallel, cultures that institutionalize mentoring, learning infrastructures, participation, and justice reduce burnout and turnover and enable people-centered change [17,123,124,138]. Together, leadership and culture therefore complement each other in predicting human-centered management adoption.

Proposition 1.

Supportive leadership and organizational culture are both positively associated with the adoption of human-centered management, and their joint presence is associated with even higher levels of human-centered management.

The convergence of multiple studies linking participative and supportive leadership to the creation of fundamental psychosocial resources consistently demonstrates that both factors are systematically linked to the adoption of human-centered management practices, justifying Proposition 1.

4.2. Human-Centered Management Governs Change to Enhance Resources and Contain Demands

Human-centered management translates ethical and ergonomic principles into the day-to-day governance of technological and organizational change, improving quality, fairness, and pacing and, in turn, enhancing job resources while containing demands. The review shows that integrating human factors/ergonomics and technomoral guidance into AI/data work, along with participatory, person-centered design, yields safer, clearer, and less stressful systems [13,50,112]. Managerially, human-centered management frameworks that promote flexibility, collaboration, transparent communication, and learning orient work systems toward dignity and sustainable productivity [14,15,115].

Proposition 2.

Human-centered management is associated with higher levels of quality, equity, and pace of technological and organizational change, as well as being related to a more efficient use of labor resources and greater integration of work demands into the psychosocial system.

The recurring association between human-centered practices, improved sociotechnical systems, and reduced psychosocial burdens provides a robust empirical basis to support Proposition 2.

4.3. Leadership and Culture Directly Shape Psychosocial Mechanisms (More Resources, Fewer Demands)

Beyond governance, leadership and culture directly configure psychosocial mechanisms by increasing resources (e.g., autonomy, clarity, participation, perceived organizational support) and lowering demands (e.g., role ambiguity, interpersonal risk). Evidence links leader–member exchange, engaging/health-promoting leadership, and inclusive practices to psychological safety, recognition, and justice climates that bolster well-being [72,73,74,76]. Cultural levers (safety, justice, inclusion, resilience, and knowledge-sharing norms) buffer toxic leadership, stimulate voice, and strengthen collaboration [9,16,125,126].

Proposition 3.

In addition to human-centered management, leadership and culture are associated with psychosocial mechanisms (more resources; fewer demands), and are related to perceived levels of clarity, participation, fairness, and psychological safety.

Leadership and culture are linked to greater autonomy, less ambiguity, lower interpersonal risk, and a climate of justice and psychological safety, corroborated by the JD-R, positive leadership, and organizational justice models. The recurrence of these findings supports Proposition 3.

4.4. The Resources–Demands Balance Mediates Effects on Workplace Well-Being

The balance of resources and demands mediates the effects of leadership, culture, and human-centered management on workplace well-being. In line with JD-R and Conservation of Resources (COR) frameworks, organizational climates that enhance autonomy, feedback, development opportunities, and support, while simultaneously reducing ambiguity and overload, are associated with higher engagement and lower burnout [46]. Review findings show that leadership styles elevating psychological safety and fairness, together with supportive cultures and human-centered management routines, channel their influence through these psychosocial mechanisms to improve well-being [14,70,71,124].

Proposition 4.

The relationship between leadership, culture, and human-centered management with well-being at work (greater engagement and vigor; less burnout and stress) appears to be associated with the balance between resources and demands in the work environment.

The consistent association between autonomy, feedback, and support with higher levels of engagement and lower levels of burnout, widely documented in the literature, is directly aligned with the central mechanism proposed by the JD-R and COR models, reinforcing the theoretical robustness of these relationships (Proposition 4).

4.5. Workplace Well-Being Promotes Innovative Work Directly and via Motivation/Satisfaction

Well-being acts as a proximal driver of innovative work, directly and via motivation/satisfaction. Evidence from healthcare and service-intensive settings shows that higher engagement and lower burnout promote creativity, knowledge sharing, and constructive conflict management, all of which serve as precursors to innovative behaviour [71,74,83]. The SLR also indicates that higher well-being lifts motivation and job satisfaction, which then translate into innovative work and sustainable performance [94,95,96,99,100].

Proposition 5.

Well-being at work is associated with higher levels of innovative behaviour, and this relationship may also be linked to higher levels of motivation and job satisfaction.

Empirical evidence demonstrates that high levels of engagement, vigor, and low burnout rates are systematically associated with greater creativity, intensified knowledge sharing, constructive conflict, and innovative behaviours, which is fully consistent with the premises of expansion and development and prosperity models, as well as with the classic literature on job satisfaction (Proposition 5).

4.6. How Leadership and Culture Cascade to Innovation via Human-Centered Management and Well-Being

Leadership and culture set conditions for human-centered management [4,69,124]. Human-centered management shapes change quality and psychosocial load [13,14], the resources–demands balance raises well-being [46], and well-being, often via motivation/satisfaction, drives innovative behaviour and performance [83,94,96]. This serial chain integrates the social architecture with implementation governance and worker states into a single explanatory route.

Proposition 6.

The primary pathway to innovative work appears to unfold through a sequential pattern in which leadership and organizational culture are associated with human-centered management practices, which, in turn, relate to more favorable psychosocial mechanisms, higher well-being, greater motivation and satisfaction, and, ultimately, higher levels of innovative work behaviour.

The accumulated evidence in Propositions 1–5, consistent with integrative models of organizational psychology, reveals a chain of associative—not causal—effects whose sequential articulation, repeatedly documented in the literature, supports the formulation of Proposition 6.

5. Study Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Despite the methodological efforts undertaken, this study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the search strategy relied on a single database and included only publications in English, which may have excluded relevant studies published in other languages or indexed in other sources, thereby limiting the global representativeness of the sample. Second, the predominance of cross-sectional study designs restricts the ability to infer causal relationships among the concepts analyzed. In addition, the inclusion of reviews alongside primary studies may potentially result in double counting of findings; to mitigate this effect, a careful approach was implemented to identify and separate redundant data, although some degree of overlap may remain. Another relevant issue concerns the biases inherent in keyword-based bibliometrics, which depend on how terms are indexed, terminological heterogeneity, and database coverage—all of which may influence cluster formation and the interpretation of themes. Taken together, these limitations underscore the need for caution when generalizing the results and suggest that future research should incorporate multiple databases, multilingual approaches, longitudinal designs, and detailed documentation of bibliometric coding reliability.

Emerging issues, such as diversity, intersectional inclusion, and the impact of AI on psychological well-being, remain underexplored. From a methodological standpoint, there is a shortage of qualitative and mixed-methods research that captures the subjective perceptions of workers and leaders regarding the balance between innovation and humanity.

The findings provide a basis for outlining a future research agenda, summarizing the main guidelines that emerge in each of the five groups (Table 3), as well as the cross-cutting themes that link them.

Table 3.

Suggestions for future research.

In addition to the suggestions described for each cluster, we recommend preregistered longitudinal field studies to test the propositions (Propositions 1–6), cross-cultural comparisons, and mixed-methods case studies on human-centered digital transformation.

6. Conclusions

This systematic literature review identified and integrated the main dimensions that structure the contemporary debate on workplace well-being, leadership, motivation, organizational culture, and human-centered management in contexts of technological transformation. The results show that organizations seeking to reconcile innovation and human sustainability tend to adopt management models based on ethical values, inclusion, psychological safety, and a balance between work demands and resources.

In general, the analysis reveals that leadership and organizational culture are factors frequently associated with the psychosocial climate and the ability to respond to change. Authentic, transformative, and inclusive leadership appear in the literature associated with environments of trust and fairness, essential for promoting well-being and motivation. In turn, organizational cultures that value learning, collaboration, and equity are described as related to lower levels of burnout and a greater likelihood of innovative behaviours.

Human-centered management emerges as an integrating axis, translating ethical and ergonomic principles into organizational practices frequently described as promoting healthier and more meaningful work experiences. This approach is particularly relevant in the context of digitalization and smart technologies, since the literature suggests that it is related to technological use processes perceived as clearer, more dignified, and empowerment oriented. The integration of human-centered management, well-being, and innovation is described as a characteristic of organizations considered more adaptable, especially when they demonstrate a balance between technical performance and human sensitivity.

This study contributes to broadening the understanding of the relationship between technological innovation and organizational well-being, presenting an integrated framework that goes beyond an instrumental view of technology and emphasizes its social and human role. In conclusion, sustainable development in the digital age is often associated in the literature not only with the adoption of new technologies but also with how these are managed, integrated, and articulated with principles of humanization, something that many studies describe as contributing to work environments that reconcile responsible innovation, well-being, and the creation of collective value.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411181/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 checklist. Reference [153] is cited in the Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.P.M.; methodology, I.C.P.M. and Â.M.P.; software, I.C.P.M.; validation, P.D., I.C.P.M. and Â.M.P.; formal analysis, P.D.; investigation, P.D.; resources, P.D.; data curation, I.C.P.M.; writing—preparation of the original draft, P.D. and I.C.P.M.; writing—revision and editing, P.D., I.C.P.M. and Â.M.P.; visualization, Â.M.P.; supervision, I.C.P.M.; project management, P.D.; acquisition of funding, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Portuguese nationals fund through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under project UIDB /00713/2020. NECE and this work are supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. by project reference UIDB/04630/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Data supporting this study are openly available in Zenodo at [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17735750], DOI [10.5281/zenodo.17735750], including search strategies, Scopus exports, PRISMA flow, study inclusion/exclusion lists, VOSviewer files, codebook, keyword mapping, and the registered protocol. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of AIETORG—Associcação Internacional de Estudos Transculturais e Organizacionais/Well-being and Mental Health Group, whose guidance, collaboration, and commitment to advancing research were essential to the accomplishment of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| HCM | human-centered management |

| HPWS | High-performance work systems |

| HR | Human resource |

| JD-R | Job demands-resources model |

| SDG | Sustainable development goal |

| SLR | systematic literature review |

References

- Mojica, M.; Palos-Sanchez, P.R.; Cabanas, E. Is there innovation management of emotions or just the commodification of happiness? A sentiment analysis of happiness apps. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 28, 3238–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Casanova, C.; Lechuga Sancho, M.P.; Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R. What science says about entrepreneurs’ well-being: A conceptual structure review. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2024, 37, 355–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, M.; Ravina-Ripoll, R. How can tourism managers’ happiness be generated through personal and innovative tourism services? Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 751–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J. Authentic leadership & PsyCap’s role in tackling events that impact well-being and environmental sustainability. Organ. Dyn. 2024, 53, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Koliby, I.S.; Al-Hakimi, M.A.; Zaid, M.A.K.; Khan, M.F.; Hasan, M.B.; Alshadadi, M.A. Green entrepreneurial orientation and technological green innovation: Does resources orchestration capability matter? Bottom Line 2024, 37, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y.; Kominis, G.; Ashton-Sayers, J. Authentic leadership, psychological capital, acceptance of change, and innovative work behaviour in non-profit organisations. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2024, 83, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Saxena, N. A study of motivations, practices, and innovations of intrapreneurs: Handling crisis situations. Financ. India 2023, 37, 747–772. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, J. Code green: Ethical leadership’s role in reconciling AI-induced job insecurity with pro-environmental behavior in the digital workplace. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawir, A.; Suseno, B.D. Employee performance: Exploring the nexus of nonstandard services, psychological contracts, and knowledge sharing. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 2024, 6746963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakshappa, N.; Dodds, S.; Stangl, L.M. Understanding sustainable service ecosystems: A meso-level perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2024, 38, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhana, R.; Van Caillie, D. How do performance monitoring systems support sustainability in healthcare? Soc. Bus. Rev. 2025, 20, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.; Cutrona, S.L.; Lafferty, M.; Lerner, B.; Vashi, A.A.; Jackson, G.L.; Amrhein, A.; Cole, B.; Tuepker, A. This has reinvigorated me”: Perceived impacts of an innovation training program on employee experience and innovation support. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2024, 39, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.P.J.; Parnell, C.J.; Patel, M. We have to go back, back to the future! Reflecting on 75 years of human factors in the UK to shape a future of responsible artificial intelligence innovation. Ergonomics 2025, 68, 968–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Torres, F.J.; Schiuma, G. Measuring the impact of remote working adaptation on employees’ well-being during COVID-19: Insights for innovation management environments. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M. Smarter organizations: Insights from a smart city hybrid framework. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1281–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, F.; Khan, M.R.; Khan, I.; Khan, N.R.; Keoy, K.H. Organizational resilience and green innovation for environmental performance: Evidence from manufacturing organizations. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravina-Ripoll, R.; Balderas-Cejudo, A.; Núñez-Barriopedro, E.; Galván-Vela, E. Are chefs happiness providers? Exploring the impact of organisational support, intrapreneurship and interactional justice from the perspective of happiness management. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadrawi, B.K.; Al-Hadrawi, K.K.; Ezzerouali, S.; Al-Hadraawy, S.K.; Aldhalmi, H.K.; Muhta, M.H. Mind intruders: Psychological, legal, and social effects of human parasites in the age of technological progress. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. 2024, 22, 5564–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, D.; Rombey, T. Where to Prospectively Register a Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoobane, P.; Masinde, M.; Mabhaudhi, T. Predicting Infectious Diseases: A Bibliometric Review on Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevinson, C.; Lawlor, D.A. Searching multiple databases for systematic reviews: Added value or diminishing returns? Complement. Ther. Med. 2004, 12, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frandsen, T.F.; Gildberg, F.A.; Tingleff, E.B. Searching for qualitative health research required several databases and alternative search strategies: A study of coverage in bibliographic databases. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 114, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, V.J.; Stevens, A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Kamel, C.; Garritty, C. Paper 2: Performing rapid reviews. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Grainger, M.J.; Gray, C.T. Citationchaser: A tool for transparent and efficient forward and backward citation chasing in systematic searching. J. Res. Synth. Methodol. 2022, 13, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, L.; Wilkins, S.; Law, M.; Stewart, D.; Bosch, J.; Westmorland, M. Critical Review Form—Qualitative Studies, Version 2.0; McMaster University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iansiti, M.; Levien, R. Strategy as ecology. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Brown, S.W.; Burkhard, K.A.; Goul, M.; Smith-Daniels, V.; Demirkan, H.; Rabinovich, E. Moving forward and making a difference: Research priorities for the science of service. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 4–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Parasuraman, A.; Bowen, D.E.; Patrício, L.; Voss, C.A. Service research priorities in a rapidly changing context. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.L.; Maynard, M.T.; Jones Young, N.C.; Vartiainen, M.; Hakonen, M. Virtual teams research: 10 years, 10 themes, and 10 opportunities. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.L.; Tang, C.S. Socially and environmentally responsible value chain innovations: New operations management research opportunities. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, M.C.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; Perez-Perez, M. Research in Entrepreneurship and Family Business: A Bibliometric Analysis of an Emerging Field. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.S.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Ferreira, J.J. What’s New in Research on Agricultural Entrepreneurship? J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 65, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N. “Humanity’s new frontier”: Human rights implications of artificial intelligence and new technologies. Hung. J. Leg. Stud. 2023, 64, 236–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramony, M.; Rosenbaum, M.S. SDG commentary: Economic services for work and growth for all humans. J. Serv. Mark. 2024, 38, 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tairov, I.; Stefanova, N.; Aleksandrova, A. Artificial intelligence application in human resources management. Bus. Manag. 2024, 2024, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammupriya, A.; Subrahmanyan, P. Enhancement of work engagement through HRIS adoption mediated by workplace well-being. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 20, e20231499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, E.L.; Booth, C.; Agyekum, K.; Al-Tarazi, D.; Pittri, H. A phenomenological inquiry of Building Information Modelling macro-adoption in Uruguay. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Manag. Procure. Law 2024, 177, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfö, L.; Eklund, J.; Jahncke, H. Perceptions of performance and satisfaction after relocation to an activity-based office. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakurel, J.; Melkas, H.; Porras, J. Tapping into the wearable device revolution in the work environment: A systematic review. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 31, 791–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doargajudhur, M.S.; Dell, P. Impact of BYOD on organizational commitment: An empirical investigation. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Knott, P.; Collins, J. The driving mindsets of innovation: Curiosity, creativity and clarity. J. Bus. Strategy 2022, 43, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkaniemi, L.; Lehtonen, M.H.; Hasu, M. Well-being and innovativeness: Motivational trigger points for mutual enhancement. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2015, 39, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Lakhera, G.; Sharma, M. Examining the impact of artificial intelligence on employee performance in the digital era: An analysis and future research direction. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2024, 35, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]