Abstract

Geomagnetic disturbances are an emerging sustainability challenge for modern, low-carbon and highly interconnected power systems, affecting both grid stability and market performance. We develop a deep causal neural network that fuses geomagnetic observatory measurements with national operational indicators and, via counterfactual inference, traces shock and no-shock trajectories to estimate instantaneous and cumulative impacts. Using Switzerland as a case, shocks significantly change national load, canton-level consumption, cross-border flows, and balancing prices. East–west disturbances have stronger effects than north–south, highlighting the role of grid topology. At the regional scale, the canton of Aargau shows pronounced cumulative consumption responses, revealing spatial heterogeneity. In cross-border exchanges, imports rise after shocks while exports contract and transit flows decline; balancing prices increase markedly, suggesting that market mechanisms can amplify physical stress into economic impacts. The approach goes beyond correlation and exposure metrics by providing system-level, decision-relevant effect sizes. The main contributions are as follows: (i) a deep causal framework that identifies and quantifies the causal effects of geomagnetic disturbances on grid operations and prices; (ii) topology-linked empirical evidence of directional and spatial asymmetries across national, canton-level, and cross-border indicators; and (iii) actionable levers for system operation and market design. These findings inform risk-aware reserve procurement, topology-aware dispatch, and cross-border coordination in highly interconnected, low-carbon grids, helping to enhance reliability, maintain affordability, and facilitate clean-energy integration.

1. Introduction

Ensuring resilience to space weather shocks is essential for the sustainable operation of low-carbon and highly interconnected power systems. Geomagnetic disturbances are a typical manifestation of space weather, and the rapid variations they cause in the ionosphere and the near-Earth electromagnetic environment can induce currents in long transmission lines and conductors. These currents, known as geomagnetically induced currents (GICs), may lead to the half-cycle saturation of transformers, maloperation of protective relays, voltage fluctuations, and in extreme cases, large-scale blackouts. Previous studies have documented these risks extensively [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. A well-known example is the Quebec blackout in March 1989, when a severe geomagnetic storm produced strong geomagnetically induced currents that caused the power grid to collapse within minutes, resulting in substantial economic losses [1]. Since then, the risks associated with geomagnetically induced currents have become a major topic spanning both space weather science and power engineering.

Previous research has examined the vulnerability of power systems to geomagnetically induced currents in various countries and regions, assessing their potential impacts on transmission lines and overall grid stability [1,8,9,10,11,12,13]. These studies highlight the strong spatial variability of geomagnetically induced current effects and offer practical guidance for the mitigation and protection strategies implemented by grid operators.

In Europe, the high level of cross-border interconnection and the geological complexity of transmission corridors create additional uncertainty in how power systems respond to geomagnetic disturbances. Switzerland, located at the center of the European power network, plays a key role in maintaining domestic supply and demand balance while also supporting frequent electricity exchanges with neighboring countries such as France, Germany and Italy. This geographic and infrastructural position makes Switzerland an important conduit for regional electricity markets and an ideal case for studying the influence of geomagnetic disturbances on system operations and market outcomes. Recent investigations of the Finnish and Swedish systems have documented significant geomagnetically induced current effects during severe storms [12,13]. However, most existing studies focus mainly on physical exposure and provide limited insight into how geomagnetic disturbances propagate through load patterns, cross-border flows and electricity prices.

Traditional statistical methods are widely used in energy system analysis. Yu et al. quantify demand-side uncertainty with statistical modeling and show that meter-reading distributions are approximately Gaussian [14]. Cadre and Auliac report that regret-based methods outperform other learning schemes and enable game-theoretic modeling of agent interactions [15]. Seyedshenava et al. propose a compact hybrid of probability, stochastic programming, and chance constraints to handle multiple sources of uncertainty [16]. Despite these advances, correlation-based and optimization-based statistical approaches often face difficulties in handling high-dimensional nonlinearity and nonstationarity, and they typically rely on ad hoc definitions of shocks that may obscure component-specific effects. Neural networks, by contrast, can learn complex nonlinear and high-dimensional relationships directly from data without the need for prespecified functional forms or distributional assumptions. They also capture multi scale temporal dynamics and integrate information from diverse sources, leading to stronger generalization performance and greater robustness in noisy and nonstationary environments.

In recent years, deep representation learning has been increasingly applied to power system research, ranging from forecasting to control and scheduling. Liang et al. formulate real-time dispatch as a Markov decision process and apply a Soft Actor-Critic policy to reduce operating costs while improving renewable integration [17]. Alekhya et al. show that deep learning, by capturing spatiotemporal patterns, outperforms metaheuristics for wind speed/power forecasting, with a New Delhi case confirming higher accuracy and efficiency [18]. Li et al. propose a community energy management framework that uses deep reinforcement learning, such as DQN, to co-ordinate appliances and energy storage and demonstrate gains in profitability and user comfort on Finnish data [19]. Ma et al. employ DQN to optimize energy storage sizing and operational strategies [20]. Collectively, these studies indicate that deep learning handles multivariate coupling, nonlinearity, and high-frequency signals effectively, providing robust modeling and decision support. Building on these advances, causal inference and counterfactual simulation have emerged as powerful tools for assessing external shocks in complex systems [21,22,23,24,25]. Through the potential outcomes framework, it becomes possible to compare system evolution under shock and no-shock conditions while controlling for confounding factors, thereby providing clearer identification of causal effects.

Building on this perspective, the present study develops a causal neural network framework to systematically quantify the dynamic impacts of geomagnetic disturbances on the Swiss power system. The framework combines the temporal modeling capability of gated recurrent units with a causal attention mechanism and predicts system trajectories over a 48 h horizon based on the preceding 72 h of historical information, while at the same time generating counterfactual trajectories under both shock and no-shock conditions. In terms of data design, the model integrates geomagnetic disturbance features from the Black Forest (BFO), Furstenfeldbruck (FUR) and Castello Tesino (CTS) observatories with key operational indicators of the Swiss power system, including total national load, total generation, regional consumption, cross-border imports, exports and transit flows, and balancing prices. Shock events are identified using a percentile-based threshold rule: when the absolute first difference in a geomagnetic component at the BFO station exceeds its ninety-fifth percentile, the corresponding time is classified as a shock event. Within this framework, the causal neural network performs unified estimation across multiple indicators, captures nonlinear and time-varying effects and provides a more robust and fine-grained tool for analyzing the causal influence of geomagnetic disturbances on power system operations.

2. Data and Method

2.1. Data

The data used in this study consist of power system operation records, geomagnetic observatory measurements and global geomagnetic activity indices. Power system data are obtained from the Swiss transmission system operator Swissgrid, which publishes electricity system operation data at fifteen minute resolutions for 2024 (https://www.swissgrid.ch/en/home/operation/grid-data/generation.html, accessed on 1 May 2025). These records include nationwide electricity load, total generation, regional consumption, cross-border imports, exports and transit flows, as well as secondary and tertiary control energy prices. To ensure consistency with geomagnetic observations, all power system variables are converted to hourly resolution and aggregated into representative indicators at both the national and regional levels, such as the electricity consumption in Geneva and Vaud. Taken together, these indicators provide a comprehensive description of the Swiss power system in terms of demand, supply, cross-border exchanges and price dynamics.

Geomagnetic data are obtained from one-minute observations at the BFO and FUR stations in Germany (http://www.intermagnet.org) and the CTS station in Italy (http://geomag.rm.ingv.it/index.php?op=CTS2, accessed on 1 May 2025). These stations cover key regions around Switzerland and capture geomagnetic activity in Central Europe. From the raw measurements, the X component representing the northward direction and the Y component representing the eastward direction are extracted. All components are averaged to hourly resolution and then differenced over time to construct the indicators diffX and diffY. Here, diffX denotes the first difference in the horizontal X component and diffY denotes the first difference in the horizontal Y component, so that these indicators characterize the instantaneous intensity and directional properties of local geomagnetic field variations. In addition, the analysis incorporates global geomagnetic activity indices, including the Dst and Ap indices published by the World Data Center. These indices summarize geomagnetic storm activity at the global scale and provide both a reference for interpreting local disturbances and a benchmark for validating the identified shock events.

The Industrial Production Index is obtained from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office PXWeb portal (https://www.pxweb.bfs.admin.ch/pxweb/en, accessed on 12 November 2025). Air temperature data are taken from the ECMWF ERA5 reanalysis provided through the Copernicus Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets, accessed on 12 November 2025).

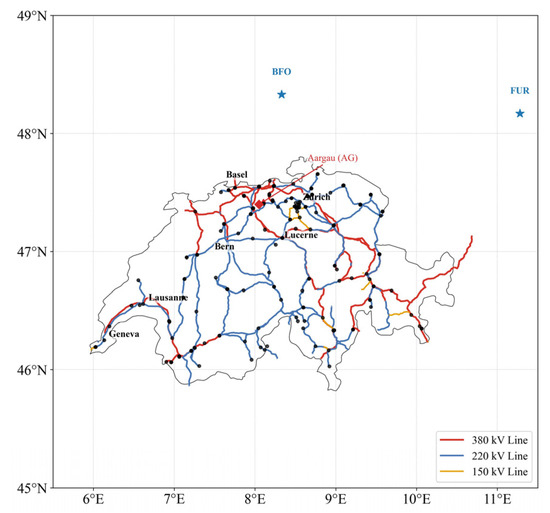

Figure 1 shows the main transmission lines and major nodes of the Swiss power grid. Overall, the grid is densest in highly populated and industrialized regions such as Zurich, Basel and Bern, where it forms a tightly interconnected core network, whereas in the southern mountainous areas, cross-border transmission lines dominate and support energy exchanges with neighboring countries such as France and Italy. The 380 kV backbone lines constitute the skeleton of the system and are responsible for large-scale, long-distance transmission, while the 220 kV and 150 kV lines are used mainly for regional distribution and cross-border interconnections. This spatial configuration provides important context for assessing the potential impacts of geomagnetic disturbances on the grid. Because high-voltage transmission lines extend over long distances and traverse multiple geological units, they are more susceptible to geomagnetically induced currents during strong geomagnetic storm events (GICs). Therefore, understanding the topology of the grid and the distribution of transmission voltage levels is an important prerequisite for conducting causal inference and risk assessment.

Figure 1.

A map of the Swiss high-voltage transmission grid. Red, blue, and yellow lines represent transmission lines with rated voltages of 380 kV, 220 kV, and 150 kV, respectively.

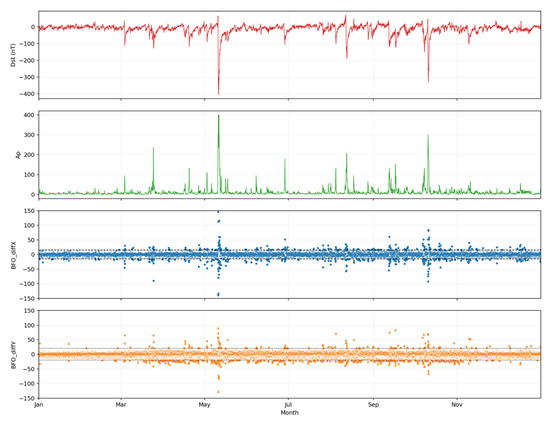

Figure 2 shows that the global-scale geomagnetic storm indices Dst and Ap and the differential components diffX and diffY at BFO station display broadly consistent activity patterns during most periods. Strong storms, characterized by sharp decreases in Dst and rapid increases in Ap, are typically accompanied by pronounced fluctuations in the local horizontal geomagnetic components. This indicates that the local difference-based indicators effectively capture the regional projection of global disturbances in the electromagnetic environment. The ninety-fifth percentile threshold provides a useful benchmark for identifying local shock events: while most disturbance points lie within this range, a small number of extreme anomalies coincide with global-scale storm episodes. The data are split chronologically into training, validation and test sets, with isolation buffers of at least seventy-two hours at each boundary to prevent temporal leakage. All input features are standardized using z score normalization based on statistics computed from the training set.

Figure 2.

Comparison of global and local geomagnetic disturbance indices in 2024. The first and second panels show the hourly variations in global storm indices Dst and Ap, while the third and fourth panels display scatter plots of the differential components diffX and diffY at BFO station, with the 95% quantile thresholds indicated by dashed black lines.

2.2. Method

This study employs a deep-learning-based causal inference framework. All power system and geomagnetic data are first aligned to universal time and resampled uniformly into hourly sequences. The input features are standardized using z score normalization to ensure comparability across variables with different units and to prevent numerical instability caused by scale differences. Shock events are identified from the BFO station in Germany, which is selected because of its geographic proximity to Switzerland. In contrast, the FUR and CTS stations are located farther away and capture disturbances that are less directly representative of the Swiss grid conditions. Geomagnetic data from both stations are nevertheless included as model inputs, ensuring that while BFO guides event detection, the wider regional disturbance environment is also reflected in the causal neural network.

To identify geomagnetic shock events, a shock is defined as occurring when the absolute first difference in a geomagnetic component at the BFO station exceeds its ninety-fifth percentile threshold. This criterion filters out routine small fluctuations and ensures a focus on extreme disturbance events.

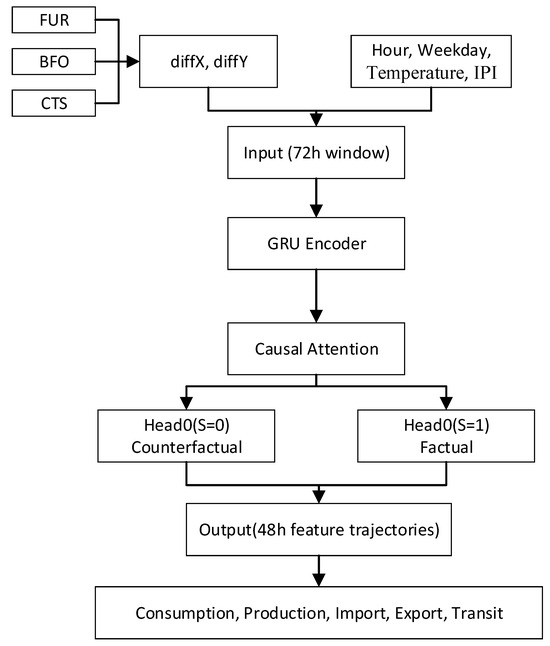

At the modeling stage, a causal recurrent network is employed that integrates gated recurrent units with a causal attention mechanism. The overall architecture of the model is illustrated in Figure 3. The model uses seventy two hours of historical data to predict the subsequent forty-eight-hour trajectory of the power system. Its output adopts a dual-head structure that separately predicts the trajectory under the shock condition and the counterfactual trajectory under the no-shock condition. The difference between these two trajectories is interpreted as the causal effect of geomagnetic shocks on the power system. During training, the loss function combines prediction error, shock classification error and a smoothness constraint on the predicted trajectories. This design helps the model capture causal relationships accurately while avoiding overfitting and unstable fluctuations. Unlike traditional machine learning models that predict only conditional means, the proposed architecture explicitly estimates counterfactual trajectories to quantify dynamic causal effects over one to forty-eight hours, enabling more robust identification of nonlinear, high-frequency and direction-specific responses and revealing spatial heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the model.

Within the modeling framework, the design of the inputs, the treatment variable and the outputs carries explicit causal meaning. The inputs consist of the previous seventy-two hours of historical information, including disturbance features from multiple geomagnetic stations and temporal control variables. The geomagnetic features are obtained from observations at the BFO, FUR and CTS stations. After aggregation to hourly resolution and differencing, indicators such as diffX and diffY are constructed to characterize the instantaneous intensity of local geomagnetic disturbances. In addition, control variables including the hour of the day and weekday indicators are incorporated to capture regular diurnal and weekly patterns in electricity demand. It is important to note that shock events themselves are not directly included as input features but are instead represented through an independent treatment variable.

In this study, the treatment variable S indicates whether a geomagnetic shock occurs at a given time. When the absolute first difference in a geomagnetic component at the BFO station exceeds its ninety-fifth percentile threshold, S is set to one; otherwise, S is set to zero. Within the model architecture, the treatment variable distinguishes between two potential outcomes: the predicted trajectory under the factual shock condition and the counterfactual trajectory under the no-shock condition. The outputs consist of predicted trajectories for multiple dimensions of the power system over the following forty-eight hours, including consumption, production, cross-border electricity imports, exports and transit flows, as well as market level balancing prices.

Under the causal inference framework, the difference between these two potential outcomes is interpreted as the causal effect of geomagnetic shocks. For a given set of inputs and background conditions, the model generates predicted trajectories under both shock and no-shock scenarios, denoted as Ŷ(S = 1) and Ŷ(S = 0). Their difference, ΔY = Ŷ(S = 1) minus Ŷ(S = 0), represents the average causal effect of geomagnetic shocks on the target variables. A single-layer GRU with a hidden size of one hundred and twenty-eight encodes the seventy-two-hour input history. On top of this, a lightweight causal attention module applies separate linear projections to the temporal states and to the feature summary, followed by softmax weighting. The mechanism uses a single head. The decoder contains two parallel MLP heads that map the aggregated state to forty-eight-step trajectories for the no-shock and shock counterfactuals, respectively, with ReLU activations throughout. A third MLP outputs the shock propensity. Mean squared error is used as the loss function. The causal effect can be computed on an hourly scale to obtain instantaneous effects or accumulated to obtain cumulative effects. Through this design, the model separates the natural evolution of the power system from the effects of shocks, thereby controlling for confounding factors and revealing the dynamic mechanisms through which geomagnetic disturbances affect power system operations.

3. Results

3.1. Causal Effects

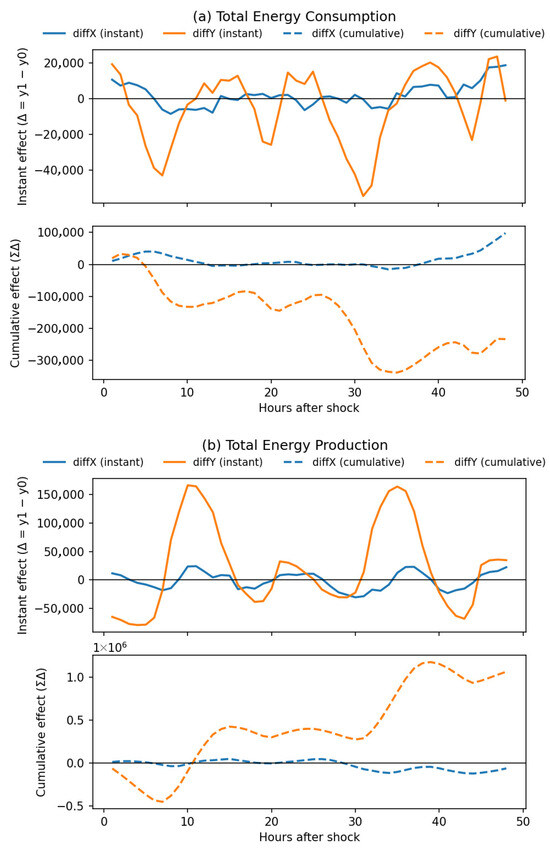

Figure 4 presents the average causal effects of geomagnetic shocks on total electricity consumption in Switzerland. For the instantaneous response, diffY shocks generate pronounced fluctuations in demand that alternate in sign and recur across the 48 h horizon. The maximum hourly deviation reaches nearly ±40,000 kWh, indicating that Y direction disturbances may impose rapid and intense short-term impacts on electricity demand and system dispatch. By contrast, the instantaneous effects of diffX shocks are much smaller, generally within ±10,000 kWh, which suggests a relatively moderate direct influence.

Figure 4.

Instantaneous and cumulative effects of geomagnetic shocks (diffX and diffY, with shocks identified at BFO station) on Switzerland’s total electricity consumption and production. The upper panel shows the instantaneous effect (Δ = y1 − y0) following the shock, while the lower panel depicts the cumulative effect (ΣΔ) over a 48 h horizon. Blue lines represent responses to diffX shocks, and orange lines represent responses to diffY shocks; solid lines denote instantaneous effects, while dashed lines indicate cumulative effects. Here, y1 = Ŷ(S = 1) denotes the predicted trajectory under shock conditions, and y0 = Ŷ(S = 0) denotes the counterfactual trajectory under the no-shock assumption. Y-direction shocks exhibit a more pronounced and persistent impact on production, while X-direction shocks have limited and short-lived effects overall.

The cumulative effects further reveal the overall impact over the 48 h horizon. diffY shocks exhibit strong persistence, with cumulative increases exceeding 360,000 kWh at around 34 h after the shock, followed by a partial decline, while still showing substantial oscillations throughout the period. This pattern suggests that Y direction disturbances exert both sustained and accumulative influences on electricity consumption. In comparison, diffX shocks mainly produce a modest negative cumulative effect, declining to about −250,000 kWh after roughly 20 h and then stabilizing at a low level, which indicates a more uniform impact with weaker overall magnitude.

Taken together, these results show that Y direction disturbances have more pronounced and complex effects on electricity consumption, capable of triggering both sharp short term fluctuations and strong medium term cumulative impacts, whereas X direction disturbances display comparatively modest effects. This contrast highlights the need to pay greater attention to the sudden and accumulative risks associated with diffY in power system operation and risk assessment.

3.2. Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the robustness of our causal estimates, we conduct two complementary sensitivity analyses: (i) varying the set of control inputs (Temperature and economy) and (ii) varying the shock-identification threshold (90th/95th/99th percentiles). In all exercises, we keep the network architecture, window length, optimization settings, and evaluation protocol unchanged.

Baseline (all inputs) uses the full covariate set: geomagnetic drivers, time controls, and both temperature and the Industrial Production Index (IPI). The comparison specs drop key covariates from this baseline: Baseline − Temperature excludes Temperature; Baseline—IPI excludes IPI; Baseline—Temperature and IPI excludes both of Temperature and IPI.

From Table 1 and Table 2, a consistent pattern emerges across all specifications. Y direction shocks generate larger effects than X direction shocks. On the consumption side, Y direction shocks lead to large negative peaks and sizable cumulative decreases, whereas the effects of X direction shocks are small and short-lived. On the production side, Y direction shocks generate cumulative gains on the order of 1 × 106 kWh, while the effects of X direction shocks are moderate or close to zero. Adding temperature and the Industrial Production Index mainly rescales the magnitudes: temperature absorbs seasonal variation in demand and the Industrial Production Index accentuates production responses. However, the signs of the effects and the ordering, with Y direction larger than X direction, remain unchanged. These results indicate a clear directional asymmetry that is robust to the choice of covariates.

Table 1.

Consumption—sensitivity to inputs.

Table 2.

Production—sensitivity to inputs.

From Table 3 and Table 4, the threshold sensitivity analysis shows consistent patterns at the 90 percent and 95 percent cutoffs. On the consumption side, Y direction disturbances generate larger negative instantaneous and cumulative effects than X direction shocks. On the production side, Y direction disturbances yield pronounced positive cumulative gains, whereas the effects of X direction shocks are weaker and often slightly negative. Raising the cutoff from 90 percent to 95 percent reduces the number of shock events. The magnitudes attenuate but remain on the order of 105 to 106 kWh for consumption, and the cumulative production gains associated with Y direction disturbances remain around 106 kWh, so the main conclusions hold. At the 99 percent cutoff, some series show jumps or changes in sign, which is attributable to the very small number of events and increased variance. For this reason, the 99 percent results are treated as an extreme stress test, and the 95 percent cutoff is used as the primary specification. Overall, the dominance of diffY over diffX is robust to the choice of threshold.

Table 3.

Consumption—threshold sensitivity to local geomagnetic shocks.

Table 4.

Production—threshold sensitivity to local geomagnetic shocks.

3.3. Robustness Validation

To evaluate the credibility of the counterfactual trajectories and guard against spurious associations driven by random fluctuations, we implement two complementary robustness checks. First, we compute 48 h forecast errors, measured by mean absolute error and root mean squared error, during non-shock periods, that is, periods with no diffX or diffY exceedances, in order to assess how well the model fits the baseline dynamics. Second, we generate multiple sets of placebo shocks that mirror the number and temporal structure of the real events. The placebo shocks are required to have a minimum spacing of at least 72 h and to match the hour-of-day and day-of-week distributions of the actual events. For each placebo set, we estimate the 48 h cumulative effects and use the resulting placebo distribution to obtain two-sided p values. Smaller p values together with lower non-shock forecast errors provide stronger evidence for the robustness of the findings. The specific results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Non-shock MAE/RMSE and placebo tests for geomagnetic shock impact.

In non-shock hours, the model tracks the baseline dynamics in a stable manner. For consumption, the mean absolute error is 1.08 × 105 kWh for X direction shocks and 1.10 × 105 kWh for Y direction shocks, and the root mean squared error is 1.35 × 105 kWh and 1.37 × 105 kWh, respectively. For production, the mean absolute error is 3.57 × 105 kWh for X direction shocks and 3.54 × 105 kWh for Y direction shocks, and the root mean squared error is 4.44 × 105 kWh and 4.40 ×105 kWh, respectively. These errors support the plausibility of the counterfactual trajectories.

The placebo experiment shows statistical significance only for production under Y direction shocks, with a 48 h cumulative effect of 10.66 × 105 kWh and a p value of 0.002, whereas the other three cases are not significant with p values greater than or equal to 0.92. Taken together, Y direction disturbances exhibit clearer and economically meaningful supply-side impacts, demand responses are weaker and heterogeneous in sign, and X direction shocks have small aggregate effects. Overall, the model remains accurate outside shock periods and yields effect estimates that are consistent with physical and market mechanisms.

3.4. Cross-Border Flows and Price Effects

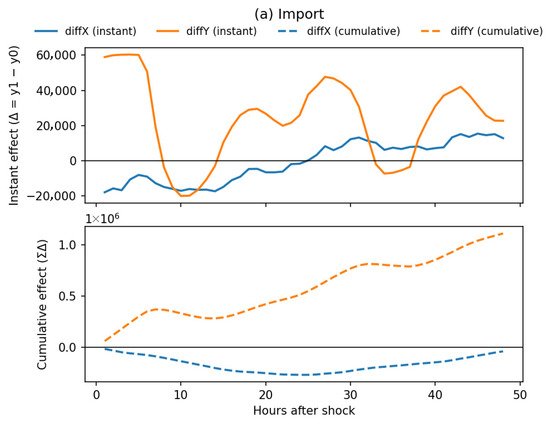

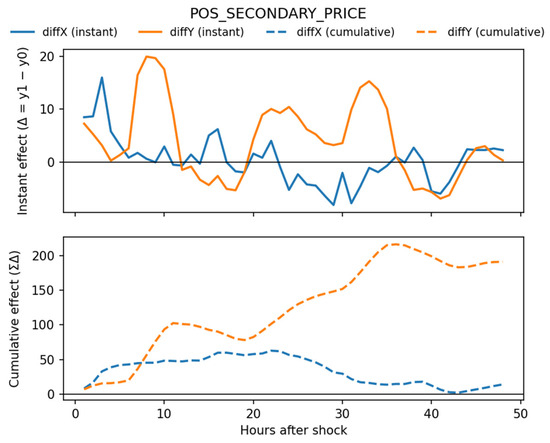

Figure 5 shows the average responses of cross-border electricity flows to geomagnetic disturbances. Overall, cross-border exchanges display pronounced sensitivity to geomagnetic shocks, with clear differences across imports, exports and transit flows.

Figure 5.

Instantaneous and cumulative effects of geomagnetic shocks (diffX and diffY, with shocks identified at BFO station) on Switzerland’s cross-border electricity flows. Each subfigure corresponds to a different cross-border variable: (a) imports, (b) exports, and (c) transit. The upper panels display the instantaneous effects (Δ = y1 − y0) following the shock, while the lower panels show the cumulative effects (ΣΔ) over a 48 h horizon. Blue lines represent diffX shocks and orange lines represent diffY shocks; solid lines denote instantaneous effects, while dashed lines indicate cumulative effects. Overall, cross-border exchanges are highly sensitive to geomagnetic disturbances: diffY shocks generate alternating positive deviations in imports, consistent with imports partially compensating for domestic deficits; diffY shocks lead to persistent contractions in exports; and transit flows exhibit sharp negative deviations and pronounced negative cumulative effects, indicating a disruption of Switzerland’s role as a transit corridor.

For imports, Y direction disturbances generate alternating positive deviations, suggesting that part of the domestic electricity shortfall may be offset by an increase in imports. By contrast, the cumulative response to X direction disturbances remains nearly flat, indicating a negligible influence on import dynamics.

Exports follow a different pattern. Y direction disturbances lead to substantial reductions in exported electricity across several periods, and the cumulative response shows a persistent downward trend over the 48 h horizon. This indicates that Switzerland’s export capacity becomes constrained under geomagnetic disturbances. X direction disturbances also contribute to a prolonged decline, reinforcing the contraction in export flows.

Transit flows exhibit particularly volatile instantaneous responses, with Y direction disturbances producing several sharp negative deviations. The cumulative effect remains strongly negative throughout the observation window, suggesting that Switzerland’s role as a transit corridor for European electricity is disrupted, with potential spillover consequences for the broader power market.

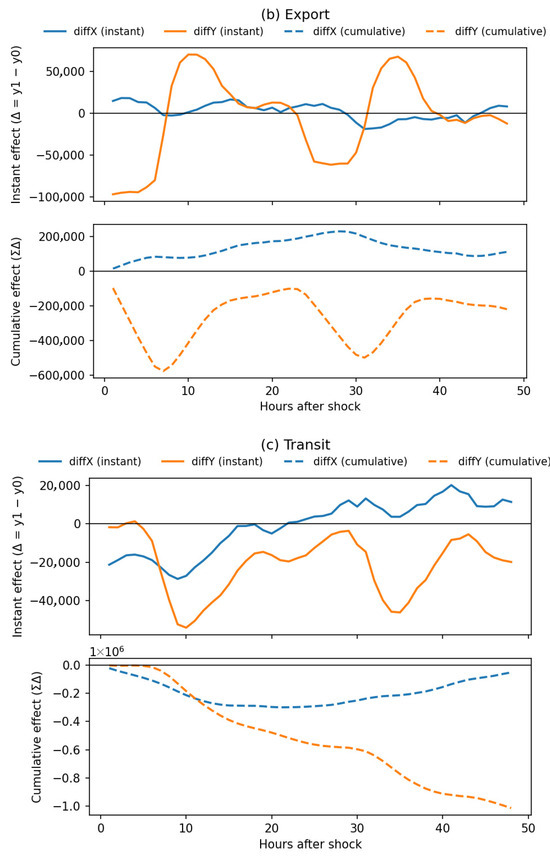

Figure 6 shows that geomagnetic disturbances exert significant and asymmetric impacts on the positive secondary control energy price. For the instantaneous effects, diffY shocks trigger repeated short term oscillations with alternating positive and negative deviations, whereas diffX shocks remain comparatively muted and close to zero. This indicates that market prices are more sensitive to Y direction disturbances, with the immediate responses reflecting imbalances in reserve activation and cross-border power flows.

Figure 6.

Average instantaneous and cumulative effects of geomagnetic shocks (diffX and diffY, with shocks identified at BFO station) on the positive secondary control energy price. The top panel illustrates the hour-by-hour price changes (instantaneous effects, Δ = y1 − y0) following a shock, while the bottom panel shows the cumulative effect (ΣΔ) over a 48 h horizon. Blue lines denote diffX shocks and orange lines denote diffY shocks; solid lines represent instantaneous effects, while dashed lines indicate cumulative effects. The figure shows that geomagnetic disturbances have significant and asymmetric impacts on reserve prices: diffY shocks cause pronounced short-term oscillations and a strong, persistent upward cumulative trajectory, whereas diffX shocks remain close to zero instantaneously and exhibit only a slight, temporary downward drift, indicating much weaker effects.

For the cumulative effects, the divergence between the two shock directions becomes even more pronounced. diffX shocks exhibit only a slight downward trend that stabilizes after several dozen hours, suggesting a limited and temporary influence on reserve pricing. By contrast, diffY shocks display a persistent and pronounced upward trajectory, with cumulative increases exceeding 200 within 48 h. This indicates that Y direction disturbances can systematically elevate prices, likely reflecting their stronger physical impacts on consumption, production and transmission corridors.

Overall, geomagnetic disturbances substantially affect reserve market prices. Y direction shocks generate sustained positive cumulative effects, driving systematic increases in the positive secondary control energy price and indicating greater reserve deployment pressure under such conditions. In contrast, X direction shocks exert only minor and relatively stable effects.

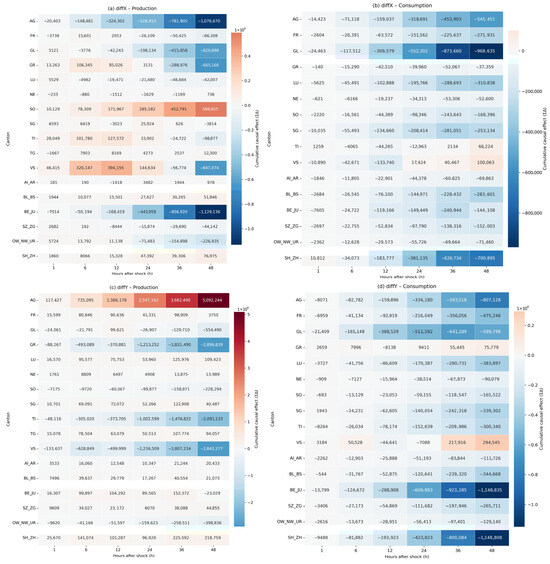

3.5. Canton-Level Cumulative Effects

Figure 7 shows heatmaps of the cumulative effects on electricity consumption and production across Swiss cantons in response to geomagnetic disturbances. The results indicate that diffX shocks exert only limited impacts on both consumption and production, with fluctuations confined to a few cantons and lacking persistence or systematic spatial patterns. In contrast, diffY shocks generate much stronger responses.

Figure 7.

Heatmaps of cumulative effects in electricity consumption and production across Swiss cantons under geomagnetic shocks (diffX and diffY, with shocks identified at BFO station). Panels (a,b) show the effects of diffX shocks on consumption and production, while panels (c,d) illustrate the corresponding effects of diffY shocks. The horizontal axis denotes the forecast horizon (hours after the shock), the vertical axis represents cantons, and the color scale indicates cumulative effects relative to the shock onset. Overall, diffX shocks have only limited and spatially confined impacts, whereas diffY shocks generate widespread and persistent suppression of consumption and strong, spatially heterogeneous amplification of production. For the canton abbreviations, please refer to Abbreviations Section.

On the consumption side, diffY shocks produce widespread and sustained negative deviations, with cumulative declines reaching several tens of thousands of kilowatt hours within 48 h. This indicates a persistent suppressive effect on electricity demand. On the production side, diffY shocks generate pronounced overshooting, with some cantons, such as Aargau, experiencing cumulative increases exceeding 5 × 106 kWh, while others show only moderate changes. These results demonstrate that diffY shocks exert a stronger and more spatially heterogeneous influence on production.

In summary, while the effects of diffX shocks remain limited in scope, diffY shocks are characterized by persistent suppression of consumption and substantial and uneven amplification of production.

4. Discussion

This study employs a causal neural network to systematically quantify the multidimensional impacts of geomagnetic disturbances on the Swiss power system, revealing compounded risks across both the physical grid and electricity markets. First, in terms of directionality, diffY disturbances exert much stronger effects than diffX. This difference is not only statistical but also physically grounded. The prevalence of long east west 380 kV backbones and the electrical anisotropy between the northern sedimentary basin and the Alpine crystalline massif increase the grid’s susceptibility to sustained geomagnetically induced currents, thereby amplifying cumulative deviations in both consumption and production.

At the regional scale, the results highlight substantial spatial heterogeneity behind the national averages. The heatmaps show that diffX shocks have only limited effects, with minor and short lived fluctuations in a few cantons, whereas diffY shocks induce widespread negative responses in consumption and pronounced amplification in production. For example, Aargau exhibits pronounced cumulative positive deviations in production, whereas several central cantons remain comparatively stable. Consistent with the grid skeleton in Figure 1, Aargau lies at the hub of the northern Swiss high-voltage network, where multiple 380 and 220 kV trunk corridors intersect. Long east–west corridors constitute a sizable share of the network and inter cantonal connections are dense. Under the geomagnetically induced current mechanism, greater line length, higher network connectivity and alignment of line orientation with the induced geoelectric field promote larger quasi-direct current flows, triggering reactive power compensation and redispatch. This mechanism is consistent with the amplified cumulative production response observed in Aargau and highlights marked spatial heterogeneity. Moreover, Aargau lies within the north-central Swiss sedimentary belt, where crustal resistivity is generally lower than in the Alpine highlands, facilitating the closure of geoelectric current loops and further magnifying the disturbance response.

For cross-border electricity flows, the results show highly asymmetric dynamics. Imports partially offset domestic shortfalls, whereas exports and transit flows contract significantly. This suggests that geomagnetic disturbances affect not only domestic supply and demand balance but also the broader European electricity market through cross-border channels, amplifying regional risks. Given the high level of interconnection in the European grid, such spillover effects imply that local disturbances may trigger systemic cascading responses.

At the market level, prices exhibit a different type of sensitivity compared with physical indicators. The positive secondary control energy price rises significantly under Y direction disturbances and shows a sustained cumulative increase. This suggests that strong geomagnetic shocks place additional stress on reserve deployment, with the pricing mechanism reflecting risk premia under disturbed conditions. However, instead of smoothing external shocks, the rapid and pronounced price adjustments may amplify short term volatility, underscoring the tight coupling between physical disturbances and economic feedbacks.

Taken together, geomagnetic disturbances create a compound risk through multiple channels. Grid topology and geological factors determine the pathways and persistence of physical effects. Regional heterogeneity reveals localized vulnerabilities. Cross-border interconnections amplify the transmission of disturbances. Market mechanisms further magnify system instability. Based on these findings, three actionable measures are recommended: risk-aware reserve procurement triggered by direction-specific thresholds, topology-aware dispatch and remedial actions prioritizing vulnerable east–west corridors, and cross-border coordination of flexibility ahead of disturbance windows. These measures support sustainable operation in highly interconnected low-carbon grids by enhancing reliability, maintaining affordability and facilitating clean energy integration.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a causal neural network framework to quantify the causal impacts of geomagnetic disturbances on the Swiss power system. The framework integrates geomagnetic station records with power system operation indicators and simulates both shock and no-shock trajectories through counterfactual inference. This enables a systematic assessment of time-varying responses in national load, cross-border electricity flows and market prices. The results show that geomagnetic disturbances can substantially alter electricity demand and import and export patterns in the short term and can also influence balancing prices. These findings confirm the dual risks posed by geomagnetic activity to both system security and economic operation.

- (1)

- Directional asymmetry: The Y component at the BFO station produces substantially stronger effects than the X component, reflecting the spatial configuration of the Swiss grid. East–west disturbances propagate more intensively within the system, consistent with the directional characteristics of geomagnetically induced current paths and underscoring the central role of grid topology and geological setting in shaping system sensitivity.

- (2)

- Regional heterogeneity: Significant differences arise between national and regional electricity indicators. While total national load and generation display relatively smooth average effects, regional indicators, particularly in cantons with dense cross-border interconnections such as Aargau, show more pronounced and asymmetric responses. This suggests that structural features of regional subsystems can either amplify or mitigate the impacts of geomagnetic disturbances.

- (3)

- Cross-border dynamics: Imports, exports and transit flows exhibit complex and asymmetric responses following shocks. Imports can partially offset domestic shortfalls, whereas exports and transit flows often contract. These patterns indicate that geomagnetic disturbances disrupt domestic supply and demand balance and reshape electricity exchanges across borders, potentially affecting the stability of the interconnected European power market.

- (4)

- Market sensitivity: The positive secondary control energy price rises persistently under Y direction disturbances, highlighting the stress placed on reserve deployment and the pricing of risk premia under disturbed conditions. This finding shows that market mechanisms can act not only as buffers but also as amplifiers, transmitting physical disturbances into economic risks and creating challenges for system operation and regulatory design.

The main contributions are three-fold: (i) a deep-learning-based causal inference framework that formulates the relation between geomagnetic disturbances and power system indicators as a dynamic counterfactual problem and jointly estimates instantaneous and cumulative effects across operations and prices; (ii) topology-linked empirical evidence of directional and spatial asymmetries across national, canton-level and cross-border indicators; and (iii) actionable measures including risk-aware reserve procurement, topology-aware dispatch on vulnerable east–west corridors and cross-border pre positioning and coordination of flexibility. These contributions support reliable, affordable and clean operation in highly interconnected low-carbon grids. Future work will extend the framework to multi-country settings and examine performance across voltage levels to strengthen the resilience of interconnected power systems.

To operationalize these recommendations, a concrete pathway is proposed. In the day-ahead and intraday horizons, couple the geomagnetic risk signals defined by percentile thresholds with load and renewable forecasts, moderately increasing aFRR and mFRR procurement by risk tier and securing minimum outputs for critical units during high-risk windows. Before and during real-time operations, prioritize phase-shifting transformer adjustments, reactive compensation switching, flow caps and targeted temporary topology reconfiguration on vulnerable east–west 380 kV corridors to suppress geomagnetically induced voltage and power flow deviations. On the cross-border side, and consistent with ENTSO E frameworks, share risk windows with neighboring transmission system operators and pre-position reserve exchange or redispatch quotas so that high-risk up-regulation can be supported across areas to maintain N minus 1 and voltage stability. In parallel, establish a monitor–trigger–evaluate loop: publish risk and 48 h effect bands, automatically execute measures when thresholds are met and recalibrate thresholds and coefficients ex post using non-shock forecast errors and placebo p values. This embeds risk awareness, topology awareness and cross-border coordination into routine dispatch in a practical and compliant manner.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F., J.T. and D.Y. (Ding Yang); methodology, Z.F. and J.T.; validation, Z.F., J.T. and D.Y. (Ding Yuan); formal analysis, Z.F.; investigation, Z.F.; resources, J.T. and D.Y. (Ding Yang); data curation, Z.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.F.; writing—review and editing, J.T., D.Y. (Ding Yang) and D.Y. (Ding Yuan); visualization, Z.F.; supervision, J.T. and D.Y. (Ding Yang); project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, D.Y. (Ding Yang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42404179) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Zhejiang (GK249909299001-034).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The electricity system data used in this study were obtained from the Swissgrid open data platform (https://www.swissgrid.ch/en/home/operation/grid-data/generation.html, accessed on 1 May 2025). Geomagnetic observations were sourced from one-minute resolution data at the BFO and FUR stations in Germany, available via the INTERMAGNET consortium (http://www.intermagnet.org, accessed on 1 May 2025) and CTS in Italy (http://geomag.rm.ingv.it/index.php?op=CTS2, accessed on 1 May 2025). IPI is sourced from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office PXWeb portal (https://www.pxweb.bfs.admin.ch/pxweb/en, accessed on 12 November 2025). Air temperature uses the ECMWF ERA5 2 m reanalysis from the Copernicus Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets, accessed on 12 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Swissgrid for providing electricity system data, and INTERMAGNET for providing Geomagnetic data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

Swiss cantons and their abbreviations.

| Abbr. | Cantons |

| AG | Aargau |

| FR | Fribourg |

| GL | Glarus |

| GR | Graubünden |

| JU | Jura |

| LU | Lucerne |

| SG | Sankt Gallen |

| SO | Solothurn |

| TG | Thurgau |

| TI | Ticino |

| VS | Valais |

| AI_AR | Appenzell Innerrhoden and Appenzell Ausserrhoden |

| BE_JU | Bern and Jura |

| BL_BS | Basel-Landschaft and Basel-Stadt |

| OW_NW_UR | Obwalden, Nidwalden and Uri |

| SH_ZH | Schaffhausen and Zurich |

| SZ_ZG | Schwyz and Zug |

References

- Bolduc, L. GIC observations and studies in the Hydro-Québec power system. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2002, 64, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinski, T.S. Why utilities respect geomagnetically induced currents. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2002, 64, 1765–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boteler, D.; Shier, R.; Watanabe, T.; Horita, R. Effects of geomagnetically induced currents in the BC Hydro 500 kV system. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1989, 4, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirjola, R. Geomagnetically induced currents during magnetic storms. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2000, 28, 1867–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirjola, R.; Boteler, D.; Viljanen, A.; Amm, O. Prediction of geomagnetically induced currents in power transmission systems. Adv. Space Res. 2000, 26, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirjola, R. Review on the Calculation of Surface Electric and Magnetic Fields and of Geomagnetically Induced Currents in Ground-Based Technological Systems. Surv. Geophys. 2002, 23, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wik, M.; Viljanen, A.; Pirjola, R.; Pulkkinen, A.; Wintoft, P.; Lundstedt, H. Calculation of geomagnetically induced currents in the 400 kV power grid in southern Sweden. Space Weather. Int. J. Res. Appl. 2008, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.; Angling, M.; Barclay, L.; Curry, C.; Dyer, C.; Edwards, R.; Greene, G.; Hapgood, M.; Horne, R.; Jackson, D.; et al. Extreme Space Weather: Impacts on Engineered Systems and Infrastructure; Royal Academy of Engineering: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Juusola, L.; Viljanen, A.; van de Kamp, M.; Tanskanen, E.I.; Vanhamäki, H.; Partamies, N.; Kauristie, K. High-latitude ionospheric equivalent currents during strong space storms: Regional perspective. Space Weather. 2015, 13, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai-Rang, W.; Lian-Guang, L.; Yan, L. Preliminary Analysis on the Interplanetary Cause of Geomagnetically Induced Current and Its Effect on Power Systems. Chin. Astron. Astrophys. 2015, 39, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-M.; Liu, L.-G.; Pirjola, R. Geomagnetically Induced Currents in the High-Voltage Power Grid in China. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2009, 24, 2368–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, A.; Lindahl, S.; Viljanen, A.; Pirjola, R. Geomagnetic storm of 29–31 October 2003: Geomagnetically induced currents and their relation to problems in the Swedish high-voltage power transmission system. Space Weather. Int. J. Res. Appl. 2005, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljanen, A.; Pirjola, R. Statistics on geomagnetically-induced currents in the Finnish 400 kV power system based on recordings of geomagnetic variations. J. Geomagn. Geoelectr. 2010, 41, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; An, D.; Griffith, D.; Yang, Q.; Xu, G. On statistical Modeling and Forecasting of Energy Usage in Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the Conference on Research in Adaptive & Convergent Systems, Towson, MD, USA, 5–8 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cadre, H.L.; Auliac, C. Energy Demand Prediction in a Charge Station: A Comparison of Statistical Learning Approaches. In Proceedings of the European Electric Vehicle Congress, Brussels, Belgium, 19–22 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- SeyedShenava, S.; Zare, P.; Davoudkhani, I.F. Integrating hybrid stochastic and statistical methods for efficient deployment of electric bicycle charging stations in urban power distribution networks: A coordinated expansion planning approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Zhang, X.; Tan, J.; Jing, Y.; Liangnian, L. Deep reinforcement learning-based optimal scheduling of integrated energy systems for electricity, heat, and hydrogen storage. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 233, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekhya, V.; Anandhi, R.J.; Jain, A.; Gupta, N.; Singh, S.V.; Begum, R. Leveraging Deep Learning Architectures for Accurate Wind Speed and Power Prediction in Renewable Energy Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I), Greater Noida, India, 18–20 September 2024; pp. 656–660. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Cheng, L. CuEMS: Deep reinforcement learning for community control of energy management systems in microgrids. Energy Build. 2024, 304, 113865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lv, Q.; Zhao, L.; Ma, M.; Zhou, Q. Energy management strategies based on deep learning in grid-forming energy storage systems. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2025, 20, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bica, I.; Alaa, A.; Van Der Schaar, M. Time Series Deconfounder: Estimating Treatment Effects over Time in the Presence of Hidden Confounders. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning: ICML 2020, Online, 13–18 July 2020. Part 2 of 15. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschinis, E.; Maresic, D.; Sobol, K.; Azizolah, A.; Rashedi, A.A. Increasing the Billet Productivity on a Multi-Section Continuous Casting Machine: Internal Development Case at Emirates Steel. In Proceedings of the AISTech Steel Conference 2018, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7–10 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shalit, U.; Johansson, F.; Sontag, D. Estimating Individual Treatment Effect: Generalization Bounds and Algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, B.J.; Sainburg, T.; Bastías, P.G.; Jiang, S.; Sun, Y.; Foster, J.G. A Primer on Deep Learning for Causal Inference. Sociol. Methods Res. 2024, 54, 397–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Shadaydeh, M.; Denzler, J. Deep Learning-based Group Causal Inference in Multivariate Time-series. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.08386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).