Optimization of Nitrogen Fertilizer Operation for Sustainable Production of Japonica Rice with Different Panicle Types in Liaohe Plain: Yield-Quality Synergy Mechanism and Agronomic Physiological Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Time, Place, and Materials

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Research Items and Measurement Indicators

2.3.1. Photosynthetic Parameters and Leaf Area Index

2.3.2. Dry Matter Accumulation

2.3.3. Yield and Yield Components

2.3.4. Determination of Quality Indicators

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilizer Application on Rice Yield and Quality

3.1.1. Rice Yield

3.1.2. Rice Quality

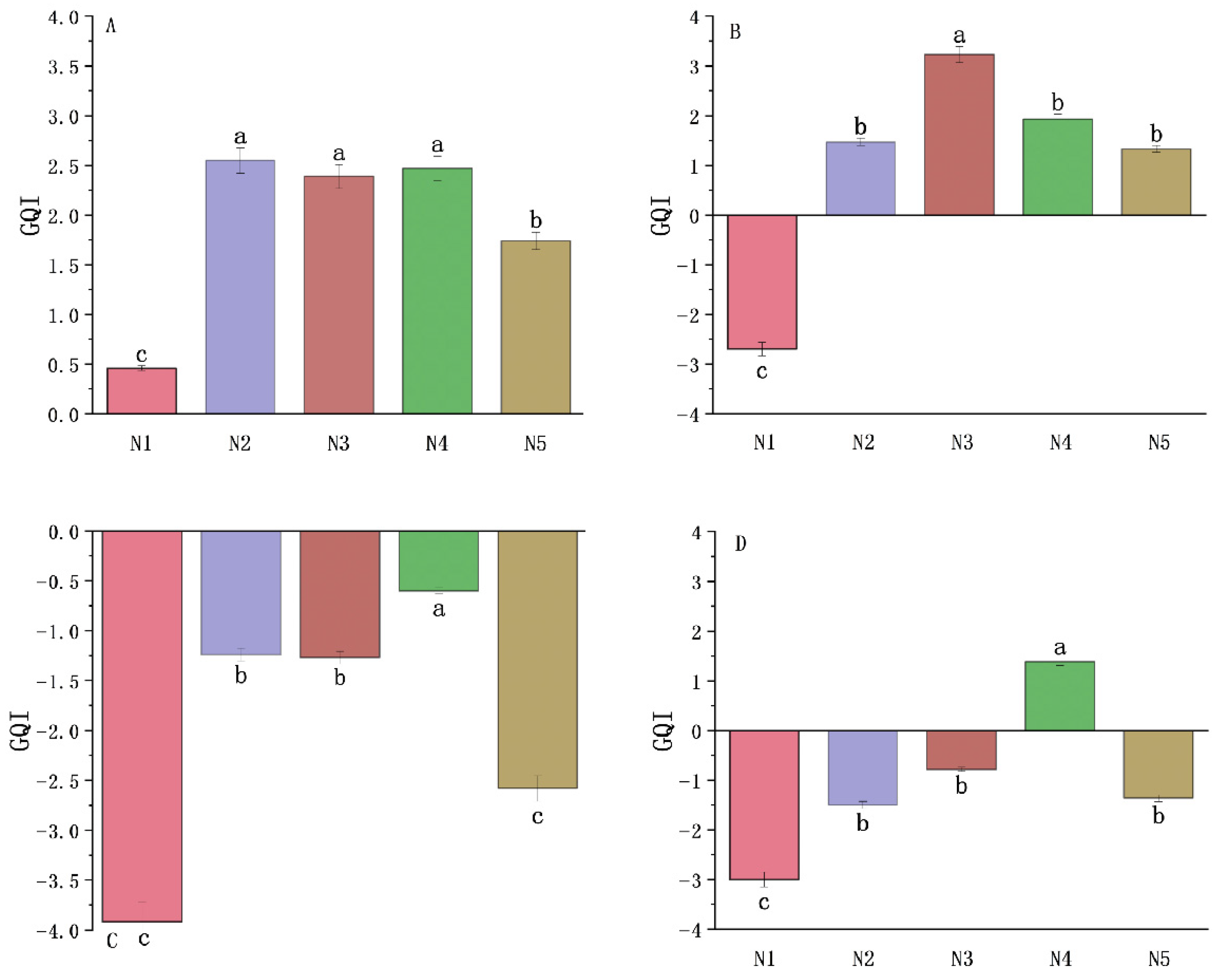

3.1.3. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilizer Operation on GQI

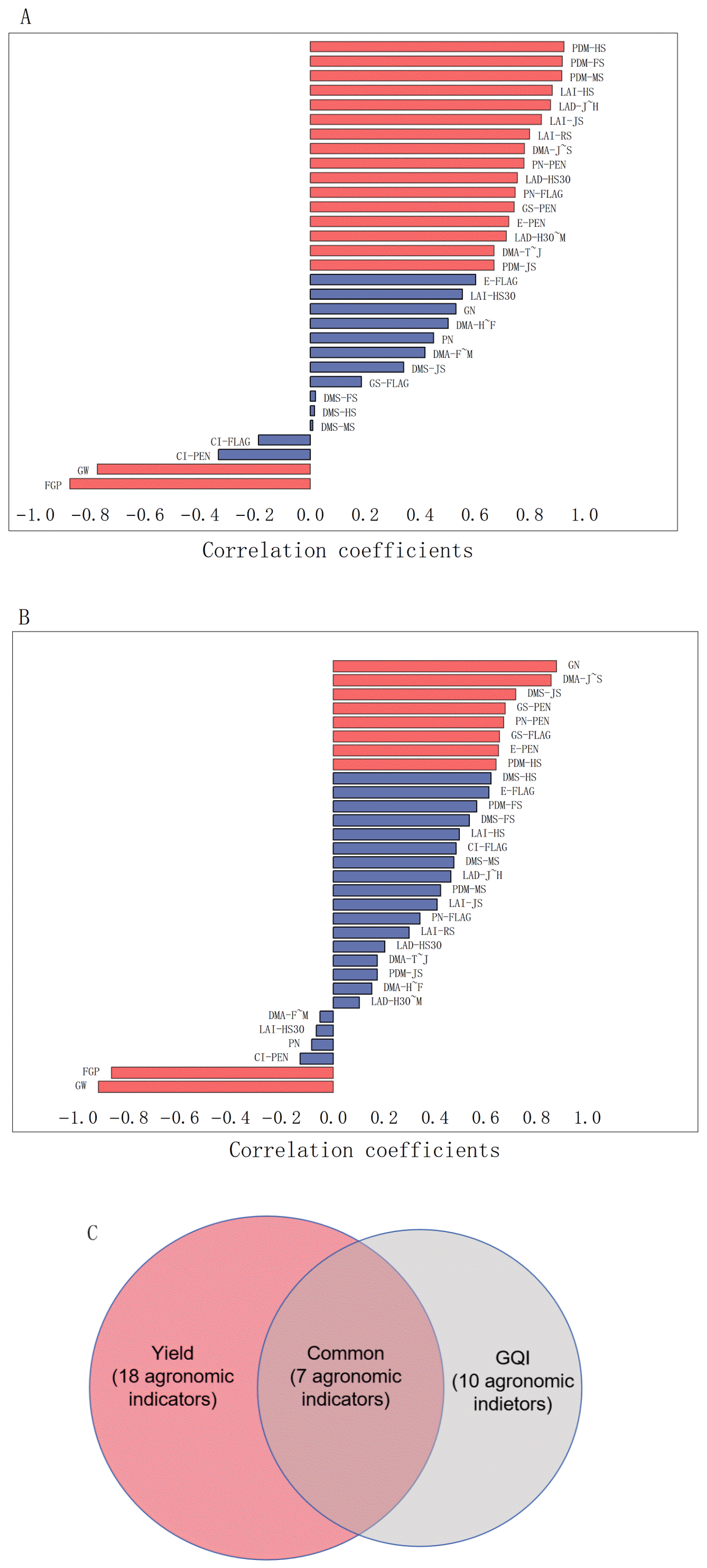

3.2. Correlation Analysis of Rice Yield, Rice Comprehensive Quality (GQI), and Agronomic Indicators Under Nitrogen Application

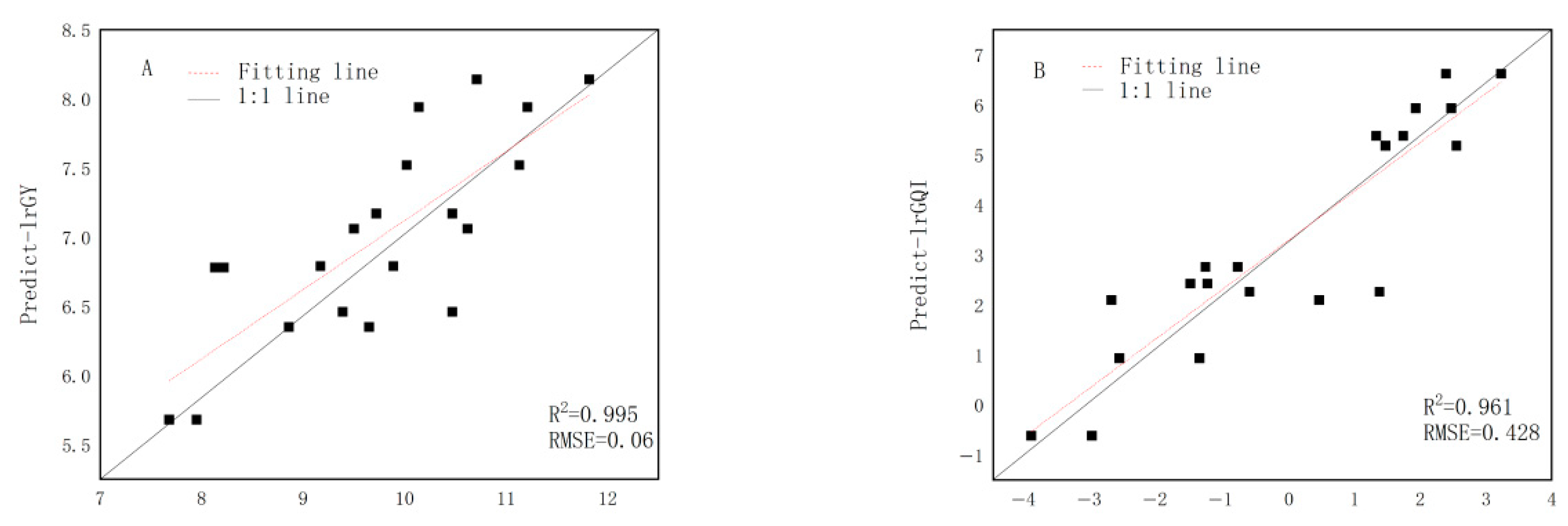

3.3. Evaluation of Agro-Physiological Indices of Rice Yield and Quality Based on the Regression Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect Mechanism of Nitrogen Fertilizer Application on Rice Yield

4.2. Regulation of Nitrogen Fertilizer Application on Rice Quality

4.3. Physiological Mechanism of Synergistic Improvement of Yield and Quality

4.4. Practical Significance of Nitrogen Fertilizer Application in Liaohe Plain Japonica Rice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, N.; Pan, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, R.; Yu, L.; Shi, W.; Li, A.; et al. Genomic insight into balancing high yield, good quality, and blast resistance of japonica rice. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Q.; Guo, H.; Li, J.; Han, S.; Khan, N.U.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; et al. Cold-adaptive evolution at the reproductive stage in Geng/japonica subspecies reveals the role of OsMAPK3 and OsLEA9. Plant J. 2022, 111, 1032–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liao, P.; Wang, W.; Xu, K.; Dai, Q.; et al. Excessive nitrogen application leads to lower rice yield and grain quality by inhibiting the grain filling of inferior grains. Agriculture 2022, 12, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tong, T.; Potcho, P.M.; Huang, S.; Ma, L.; Tang, X. Nitrogen effects on yield, quality and physiological characteristics of giant rice. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, C.; Su, Y.; Peng, W.; Lu, R.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; He, X.; Yang, M.; Zhu, S. Soil Acidification caused by excessive application of nitrogen fertilizer aggravates soil-borne diseases: Evidence from literature review and field t rials. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tao, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Song, J.; Yu, C.; Peng, X. Nitrogen application after low-temperature exposure alleviates tiller decrease in rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 158, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Guo, W.; Chen, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Ninomiya, S.; Mu, Y. Analyzing nitrogen effects on rice panicle development by panicle detection and time-series tracking. Plant Phenomics 2023, 5, 0048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Huang, A.; Sang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yang, Z. Carbon–nitrogen interaction modulates plant growth and expression of metabolic genes in rice. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Guan, X.; Han, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Asad, M.A.; Wang, Z.; Jin, R.; Pan, G.; Cheng, F. Combined effect of nitrogen fertilizer application and high temperature on grain quality properties of cooked rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 874033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, K.; Zhuo, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, L. Optimizing nitrogen regime improves dry matter and nitrogen accumulation during grain filling to increase rice yield. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Zhu, M.; Yu, J.; Kou, L.; Ahmad, S.; Wei, X.; Jiao, G.; Hu, S.; Sheng, Z.; Hu, P.; et al. Photosynthesis regulates tillering bud elongation and nitrogen-use efficiency via sugar-induced NGR5 in rice. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 1440–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, E.; Yuan, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Gu, J. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer on structure and physicochemical properties of ‘super’ rice starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 239, 116237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huai, Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Mao, G.J.; Xu, J.F. Fertilizer reduction of paddy rice in Japan: Experience and implications. China Rice 2018, 24, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Ma, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, C.; Deng, R.; Liang, K.; Qi, L. Smartphone-based detection of leaf color levels in rice plants. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Tao, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, Z.; Sun, W. Nitrogen fertilizer application rate impacts eating and cooking quality of rice after storage. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.H.; Ge, J.L.; Zhang, X.B.; Wang, Z.H.U.; Fei, D.E.N.G.; Ren, W.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Meng, T.Y.; Dai, Q.G. Decreased panicle N application alleviates the negative effects of shading on rice grain yield and grain quality. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Jiang, C.; Shou, N.; Gao, W.; Yang, X. An optimized nitrogen application rate and basal topdressing ratio improves yield, quality, and water-and N-use efficiencies for forage maize (Zea mays L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yang, C.; Ji, Q.; Jiang, L.; Tan, J.; Li, Y. Tillering responses of rice to plant density and nitrogen rate in a subtropical environment of southern China. Field Crops Res. 2013, 149, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Song, N.Y.; Chen, Q.L.; Sun, H.Z.; Peng, T.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Q.Z. Response of grain-filling rate and grain quality of mid-season indica rice to nitrogen application. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, G.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer on the eating quality of indica rice with different amylose content. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 118, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hou, D.P.; Peng, X.L.; Shao, S.M.; Jing, W.J.; Gu, J.F.; Liu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Q.; Liu, Y.Y.; Yang, J.C.; et al. Optimizing integrative cultivation management improves grain quality while increasing yield and nitrogen use efficiency in rice. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 2716–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Jia, X.; Zheng, H. The effects of different water and nitrogen managements on yield and nitrogen use efficiency in hybrid rice of China. Field Crops Res. 2012, 127, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, S.; Ohkubo, S.; San, N.S.; Nakkasame, A.; Tomisawa, K.; Katsura, K.; Ookawa, T.; Nagano, A.J.; Adachi, S. Maintaining higher leaf photosynthesis after heading stage could promote biomass accumulation in rice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Keira, M.; Yoon, D.K.; Mae, T.; Ishida, H.; Makino, A.; Ishiyama, K. Photosynthetic enhancement, lifespan extension, and leaf area enlargement in flag leaves increased the yield of transgenic rice plants overproducing Rubisco under sufficient N fertilization. Rice 2022, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Lan, Y.; Lv, X.; Fan, P.; Yang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, R.; Ma, J. Reasonable nitrogen fertilizer management improves rice yield and quality under a rapeseed/wheat–rice rotation system. Agriculture 2021, 11, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Tang, S.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Ding, C.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. Application of nitrogen fertilizer at heading stage improves rice quality under elevated temperature during grain-filling stage. Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 2183–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Ali, A.; Shi, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Tan, X.; Shang, Q.; Huang, S.; Xie, X.; Zeng, Y. Response of chalkiness in high-quality rice (Oryza sativa L.) to temperature across different ecological regions. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 87, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yuan, X.; Yan, F.; Xiang, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, L.; Fan, P.; Ma, J.; et al. Nitrogen application rate affects the accumulation of carbohydrates in functional leaves and grains to improve grain filling and reduce the occurrence of chalkiness. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 921130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zheng, J.; Sun, Y.; Chi, D. Soil nitrogen regulation using clinoptilolite for grain filling and grain quality improvements in rice. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 199, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The, S.V.; Snyder, R.; Tegeder, M. Targeting nitrogen metabolism and transport processes to improve plant nitrogen use efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 628366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Xu, M.; Li, R.; Zheng, L.; Liu, S.; Reis, S.; Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; et al. Optimizing nitrogen fertilizer use for more grain and less pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 132180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Jiang, Y.; Cao, C. Balance rice yield and eating quality by changing the traditional nitrogen management for sustainable production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Bin, S.; Iqbal, A.; He, L.; Wei, S.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, P.; Liang, H.; Ali, I.; Xie, D.; et al. High sink capacity improves rice grain yield by promoting nitrogen and dry matter accumulation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Yang, L.; Yan, T.; Xue, F.; Zhao, D. Rice dry matter and nitrogen accumulation, soil mineral N around root and N leaching, with increasing application rates of fertilizer. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 49, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; You, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. Nitrogen fertilizer increases spikelet number per panicle by enhancing cytokinin synthesis in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 33, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, P.K.; Panigrahi, R.; Turner, N.C. Physiology of spikelet development on the rice panicle: Is manipulation of apical dominance crucial for grain yield improvement? Adv. Agron. 2011, 110, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Zhang, D.; Chu, C. Interplay of light and nitrogen for plant growth and development. Crop J. 2025, 13, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.A.; Handley, L.L.; Andrews, M. Global aspects of C/N interactions determining plant–environment interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Ren, J.; Shi, X.; Xu, A.; Zhang, P.; Guo, F.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yu, H.; Jiang, C. Optimized nitrogen application ameliorates the photosynthetic performance and yield potential in peanuts as revealed by OJIP chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Ke, J.; He, H.; Wu, L.; You, C. Effects of Exogenous Trehalose on Grain Filling Characteristics and Yield Formation of japonica Rice Cultivar W1844. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2023, 37, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenabadu, M.W. Influence of time and level of nitrogen application of growth and yield of rice. Plant Soil 1972, 36, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Gao, J.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q. Nitrogen fertilization application strategies improve yield of the rice cultivars with different yield types by regulating phytohormones. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TN (g/kg) | PH | SOM (g/kg) | AP (mg/kg) | AK (mg/kg) | AN (mg/kg) | EC (μs·cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.22 | 6.8 | 26.91 | 40.84 | 91.35 | 85.59 | 0.30 |

| Treatment | Total Pure Nitrogen (kg/hm2) | Base Fertilizer (%) (kg/hm2) | Green Fertilizer (%) (kg/hm2) | Tillering Fertilizer (%) (kg/hm2) | Ear Fertilizer (%) (kg/hm2) | Granular Fertilizer (%) (kg/hm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N2 | 165 | 82.5 (50%) | 0 | 57.75 (35%) | 24.75 (15%) | 0 |

| N3 | 195 | 97.5 (50%) | 0 | 68.25 (35%) | 29.25 (15%) | 0 |

| N4 | 225 | 112.5 (50%) | 0 | 78.75 (35%) | 33.75 (15%) | 0 |

| N5 | 195 | 78.0 (40%) | 29.25 (15%) | 48.75 (25%) | 29.25 (15%) | 9.75 (5%) |

| Variety Cultivars | Nitrogen Application Rate Amount of N Application | In 2023 | In 2024 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown Rice Rate BR (%) | Polished Rice Rate MR (%) | Head Milled Rice Rate HR (%) | Brown Rice Rate BR (%) | Polished Rice Rate MR (%) | Head Milled Rice Rate HR (%) | ||

| Shendao 11 | N1 | 81.83b | 72.97b | 63.51b | 81.86c | 72.01b | 64.31b |

| N2 | 82.88a | 74.14a | 68.16a | 83.28a | 74.10a | 68.13a | |

| N3 | 83.36a | 74.77a | 67.11ab | 82.89ab | 73.88a | 68.03a | |

| N4 | 82.94a | 73.89ab | 66.63ab | 82.57b | 73.51a | 66.29ab | |

| N5 | 82.78a | 73.97ab | 68.01a | 83.20a | 74.40a | 68.42a | |

| average | 82.76 | 73.95 | 66.68 | 82.76 | 73.58 | 67.03 | |

| Shendao 47 | N1 | 81.33b | 73.35b | 65.70b | 81.76a | 73.10a | 65.49a |

| N2 | 82.36ab | 74.46ab | 70.33a | 81.65a | 73.02a | 68.98a | |

| N3 | 82.34ab | 74.44ab | 68.99ab | 81.64a | 72.24a | 66.95a | |

| N4 | 82.34ab | 74.37ab | 69.76a | 82.32a | 73.55a | 68.99a | |

| N5 | 82.79a | 74.94a | 69.59a | 81.65a | 72.96a | 67.75a | |

| average | 82.23 | 74.31 | 68.87 | 81.8 | 72.97 | 67.63 | |

| Variety Cultivars | Nitrogen Application Rate Amount of N Application | In 2023 | In 2024 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length/Width | Chalkiness Rate | Chalkiness | Length/Width | Chalkiness Rate | Chalkiness | ||

| L/W | CR (%) | CD (%) | L/W | CR (%) | CD (%) | ||

| Shendao 11 | N1 | 1.95a | 17.33a | 17.33a | 2.08a | 12.60a | 11.23a |

| N2 | 1.90a | 19.07a | 19.07a | 2.09a | 24.30a | 11.70a | |

| N3 | 1.97a | 17.40a | 17.40a | 2.42a | 22.70a | 10.30a | |

| N4 | 2.08a | 18.20a | 18.20a | 2.33a | 30.03a | 10.50a | |

| N5 | 1.91a | 15.33a | 15.33a | 2.28a | 21.33a | 6.27a | |

| average | 1.96 | 17.47 | 17.47 | 2.24 | 29.79 | 9.53 | |

| Shendao 47 | N1 | 1.79b | 7.10b | 7.10b | 2.17a | 12.57b | 2.57a |

| N2 | 1.75b | 10.50ab | 10.50ab | 2.01a | 16.33ab | 5.83a | |

| N3 | 2.72a | 8.80b | 10.00ab | 2.23a | 15.97ab | 5.30a | |

| N4 | 2.13ab | 14.17a | 14.17a | 2.28a | 22.17a | 4.50a | |

| N5 | 1.97ab | 8.20b | 9.13ab | 2.17a | 14.90ab | 3.17a | |

| average | 2.07 | 9.94 | 10.18 | 2.17 | 16.39 | 4.01 | |

| Variety Cultivars | Nitrogen Application Rate Amount of N Application | In 2023 | In 2024 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein DM Pr (%) | Fatty Acid Fatty Acid (%) | Protein DM Pr (%) | Fatty Acid Fatty Acid (%) | ||

| Shendao 11 | N1 | 9.40b | 15.63a | 6.67c | 18.57a |

| N2 | 10.23ab | 15.43a | 7.07bc | 18.67a | |

| N3 | 10.47ab | 15.60a | 7.80a | 18.43a | |

| N4 | 10.17ab | 15.17a | 7.27b | 19.67a | |

| N5 | 10.20ab | 15.33a | 7.00bc | 18.57a | |

| average | 10.09 | 15.43 | 7.16 | 18.78 | |

| Shendao 47 | N1 | 8.80ab | 16.40a | 6.30b | 19.57a |

| N2 | 9.27a | 15.63a | 6.83ab | 18.33b | |

| N3 | 9.43a | 15.60a | 7.23a | 18.23b | |

| N4 | 9.53a | 15.67a | 7.37a | 19.10ab | |

| N5 | 9.30a | 16.43a | 6.90ab | 18.97ab | |

| average | 9.27 | 15.95 | 6.93 | 18.84 | |

| Variety Cultivars | Nitrogen Application Rate Amount of N Application | In 2023 | In 2024 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylose AC (%) | Taste Value Taste Value | Amylose AC (%) | Taste Value Taste Value | ||

| Shendao 11 | N1 | 19.20a | 64.67a | 19.70a | 77.67a |

| N2 | 19.23a | 60.67ab | 19.70a | 75.33ab | |

| N3 | 19.33a | 59.67b | 19.70a | 72.00c | |

| N4 | 19.27a | 61.00ab | 19.87a | 74.33bc | |

| N5 | 19.27a | 60.67ab | 19.63a | 76.00ab | |

| average | 19.26 | 61.33 | 19.72 | 75.07 | |

| Shendao 47 | N1 | 19.37a | 67.33a | 19.77a | 79.00a |

| N2 | 19.30a | 65.00b | 19.63a | 76.67ab | |

| N3 | 19.33a | 64.33b | 19.77a | 74.67ab | |

| N4 | 19.43a | 63.67b | 19.90a | 74.00b | |

| N5 | 19.47a | 65.00b | 19.83a | 76.33ab | |

| average | 19.38 | 65.07 | 19.78 | 76.13 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lou, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Jia, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Y. Optimization of Nitrogen Fertilizer Operation for Sustainable Production of Japonica Rice with Different Panicle Types in Liaohe Plain: Yield-Quality Synergy Mechanism and Agronomic Physiological Regulation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411152

Lou X, Li M, Zhang L, Jia B, Wang S, Wang Y, Huang Y, Zhou C, Wang Y. Optimization of Nitrogen Fertilizer Operation for Sustainable Production of Japonica Rice with Different Panicle Types in Liaohe Plain: Yield-Quality Synergy Mechanism and Agronomic Physiological Regulation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411152

Chicago/Turabian StyleLou, Xinyi, Meiling Li, Lin Zhang, Baoyan Jia, Shu Wang, Yan Wang, Yuancai Huang, Chanchan Zhou, and Yun Wang. 2025. "Optimization of Nitrogen Fertilizer Operation for Sustainable Production of Japonica Rice with Different Panicle Types in Liaohe Plain: Yield-Quality Synergy Mechanism and Agronomic Physiological Regulation" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411152

APA StyleLou, X., Li, M., Zhang, L., Jia, B., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Zhou, C., & Wang, Y. (2025). Optimization of Nitrogen Fertilizer Operation for Sustainable Production of Japonica Rice with Different Panicle Types in Liaohe Plain: Yield-Quality Synergy Mechanism and Agronomic Physiological Regulation. Sustainability, 17(24), 11152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411152