Abstract

In this study, we analyze data from Chinese-listed firms, spanning the period 2011–2021, to address the question of whether analyst coverage reduces environmental, social, and governance (ESG) greenwashing. The results indicated that analysts act as an external governance mechanism that significantly restrains corporate ESG greenwashing. This effect operates through enhanced information transparency and strengthened monitoring. Furthermore, institutional ownership and media attention serve as moderators in this relationship, revealing a substitution effect between different governance mechanisms. Moreover, further analysis into heterogeneous effects uncovers that the effects are markedly stronger in firms with higher financial constraints and that belong to polluting and highly competitive industries. Our findings underscore the unique governance role of financial analysts in mitigating ESG misconduct and advancing corporate sustainability in emerging markets.

1. Introduction

In the background of promoting the sustainable development concept as a consensus [1], for the modern investor, corporate ESG performance has evolved into a central benchmark. It is fundamental for gauging sustainable value creation beyond traditional financial metrics [2]. Furthermore, for firms, strong ESG performance grants firms social legitimacy, which is essential for building a competitive advantage and reputation. Therefore, with the active promotion of stakeholders [3], the number of Chinese-listed firms that have released sustainability or ESG reports has increased [4]. However, the absence of mandatory audits and specific regulatory guidelines for ESG reporting challenges the reliability of disclosed information. This regulatory gap raises critical questions: Does corporate ESG disclosure accurately reflect reality? Does the increase in ESG information disclosure improve corporate ESG performance or just varnish its ESG performance? In fact, the regulatory framework for ESG disclosure in China, a “half-mandatory” policy that initially targeted key polluters, has often been characterized by its voluntary or quasi-mandatory nature. This creates a landscape where firms can legally engage in selective reporting, emphasizing strengths and concealing weaknesses, or forgo public disclosure entirely without facing significant legal penalty [5]. Research evidence, such as the study by Raghunandan and Rajgopal [6], reveals a tendency among firms to overstate their ESG achievements—Business Roundtable signatories often lack hard data for their social responsibility claims. While maintaining strong ESG performance requires sustained capability and investment, the significant burden this imposes may explain why some firms resort to greenwashing instead of implementing substantive measures. Consequently, in the course of engaging in ESG activities, some firms may turn to ESG greenwashing as a corporate strategy. Typically, this practice features misleading environmental claims, where promotional statements outpace actual ESG performance. As a result, a substantial gap emerges between the company’s portrayed image and its true performance, constituting deceptive disclosure [7,8]. This study defines corporate ESG greenwashing as a practice characterized by the disclosure of extensive, seemingly transparent ESG information that belies poor actual performance, aimed at responding to stakeholder expectations and pressures [9]. ESG greenwashing serves as a strategic façade, enabling firms to project an enhanced social image and capitalize on the growing pool of impact-driven investment [10]. Nevertheless, once such conduct is detected by stakeholders, it may lead to various adverse outcomes, including reputational damage, loss of investor trust, and potential regulatory penalties [11,12,13,14].

Existing studies have been devoted to exploring the determinants of corporate ESG greenwashing [7,15,16]. A key unanswered question is the role of financial analysts. Understanding their influence is crucial for detecting unethical practices and helping firms avoid ESG-related controversies. As important third-party participants in capital markets, analysts represent a significant external governance force that should not be overlooked. Previous research has demonstrated that analyst coverage plays a notable monitoring role in constraining corporate misconduct and opportunistic behaviors [17,18,19,20]. Analysts have broadened their evaluative lens, systematically incorporating non-financial disclosures into their comprehensive assessments of corporate value [21]. Existing research has found that analyst coverage influences corporate environmental policies [22] and enhances corporate emphasis on workplace safety and improves employee welfare [23] through their monitoring function. However, another stream in the literature reveals a dark side of analyst coverage on firms’ non-financial performance. They found that pressure from analysts’ earnings forecasts distorts managerial decisions, prompting firms to cut pollutant treatment costs to meet short-term earnings expectations [24]. This divergence in the literature gives rise to our central research questions: how does analyst coverage influences corporate opportunistic behavior within the ESG framework? Does it serve as an external governance mechanism that curbs corporate ESG greenwashing, or does it create short-term profit pressure that promotes such practices? To address these research gaps, this study leverages the distinctive context of China’s capital market to examine the effect of financial analysts on corporate misconduct—specifically, ESG greenwashing. This study draws on data from the Chinese A-share market over the period 2011–2021; we find that analyst coverage significantly curbs corporate ESG greenwashing. The findings are not changed under a suite of endogeneity controls and alternative empirical approaches. Further mechanism analysis reveals that analyst coverage restrains ESG greenwashing through both an information effect and a monitoring effect. In terms of the information effect, analysts collect, interpret, and disseminate corporate ESG information, thereby conveying firms’ authentic ESG performance to investors, mitigating information asymmetry, and enhancing investor awareness of corporate ESG practices. Regarding the monitoring effect, analyst coverage alleviates agency problems and raises the perceived detection risk of ESG-related manipulation. Moreover, we find that institutional ownership and media attention moderate the relationship between analyst coverage and ESG greenwashing, suggesting that different corporate governance mechanisms can serve as substitutes in disciplining such behavior. Cross-sectional analyses further suggest that analyst coverage serves as a stronger constraint for firms facing financial constraints, as well as in those operating in highly polluting and more competitive industries.

Our paper extends the current literature in the following ways: initially, we address a critical gap in the literature on restraining corporate ESG greenwashing. This challenge is especially pronounced in weakly regulated markets like China [25]. While initial inquiries have focused on internal governance factors [7], a comprehensive understanding remains elusive due to the neglect of key external mechanisms. By revealing analyst coverage as a deterrent to ESG greenwashing, our study highlights its direct role as an external monitor of corporate sustainability disclosures. Second, our findings contribute to the evolving literature on the analysts’ governance role. Previous research has established their impact on financial outcomes [26,27,28,29]. Recent work shows analysts also influence non-financial areas like philanthropy and environmental compliance [22,23,30]. We extend this line of inquiry by demonstrating their specific deterrent effect on ESG greenwashing [15]. This provides new evidence that analysts scrutinize non-financial information to mitigate opportunistic reporting in social and environmental domains. Finally, this study informs the debate on whether analyst discipline distorts corporate decisions. Some argue that pressure to meet short-term targets induces myopic behavior [19,31,32]. In contrast, our finding that coverage reduces ESG greenwashing supports the view that their monitoring function prevails. This demonstrates that analysts serve a net governance role, even in emerging markets, by upholding integrity in non-financial disclosure.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review of Corporate ESG Greenwashing Research

In the context of green and sustainable development, increasing social and environmental pressure from stakeholders has prompted corporations to engage more in ESG activities, and more firms take the initiative to release ESG information. Participating in ESG helps companies gain social legitimacy and enhance their reputation. In competitive markets, pressures from regulators and investors prompt firms to elevate their ESG standards [33] as it contributes to building a distinctive market position through enhanced reputation. Companies benefit from good ESG performance, and previous studies have found that corporate ESG performance can lessen the extent of scrutiny from regulators [34], lower corporate’ financial risk during a crisis [35], reduce stock price crash risk [36], inhibit manager misconduct [37], promote corporate green innovation [38], influence corporate lending [39], and cost of debt [40]. ESG transparency boosts firm valuation [41], affects the firm’s financial performance [42], brings higher returns for investors [43], and attracts investments with ESG preferences [10]. However, growing investor expectations for corporate ESG performance [3], coupled with firms’ incentive to leverage ESG’s positive image [44,45,46], have prompted extensive ESG disclosures that often obscure inadequate performance—a practice known as ESG greenwashing. Some firms use ESG primarily for impression management. Studies show that highly rated ESG firms may increase pollution to meet earnings targets [24], selectively report emission reductions despite actual increases [47], symbolically adopt sustainability frameworks without implementation [48], and maintain stagnating performance despite improved disclosures [49].

Despite its potential to temporarily enhance a firm’s social and environmental image, ESG greenwashing carries significant risks when detected by stakeholders. This practice undermines the fundamental credibility of ESG reporting, eroding its value for investors who rely on it to assess sustainability performance and risks. The negative consequences extend to both internal and external stakeholders. Internally, it can lower employee performance [13] while heightening perceptions of corporate hypocrisy and increasing turnover [14]. Externally, it triggers regulatory penalties, damages brand reputation, diminishes consumer loyalty [11], and reduces willingness among partners to cooperate [12]. Ultimately, greenwashing compromises the entire ESG framework, as evidenced by the lower forecast accuracy of analysts covering firms with high ESG controversies [50].

2.2. Research Hypothesis

As an important participant in the capital market, analysts can curb corporate ESG greenwashing through their dual functions as information intermediaries and external monitors.

Analysts fulfill their informational role by leveraging their professional expertise in both gathering and interpreting corporate data. Through multiple channels, including site visits and direct management engagement [51,52], they collect firsthand information that enables them to identify discrepancies between firms’ actual ESG performance and their public disclosures. Moreover, analysts possess the unique ability to translate complex ESG information into comprehensible insights, effectively directing market attention to the most material sustainability issues. When analysts detect and publicize evidence of ESG misrepresentation, they trigger cascading effects across the oversight ecosystem. Their revelations expose firms to intensified scrutiny from media outlets, regulatory bodies, and institutional investors [3,53,54]. This multilayered external pressure significantly raises the reputational and regulatory risks associated with greenwashing, thereby creating powerful disincentives for such corporate behavior.

On the other hand, analyst coverage serves as an effective monitoring mechanism that helps curb corporate ESG greenwashing. In emerging markets like China, with less developed legal and regulatory systems, low compliance costs create opportunities for firms to exaggerate their ESG performance or conceal negative information [20]. As an external governance force, analysts help alleviate principal-agent problems in ESG disclosure. Research shows that firms with extensive analyst coverage face stronger constraints on their ESG conduct and demonstrate reduced opportunistic behavior [55,56]. Empirical evidence confirms that analyst coverage exerts a significant deterrence effect by increasing the likelihood of fraud detection [20], curbing earnings management [18,19], and limiting excessive CEO compensation [17]. Particularly, industry-specialist analysts significantly enhance financial reporting quality and strengthen managerial accountability [56]. In summary, the monitoring effect created by analyst coverage substantially increases the detection risk of ESG information manipulation, thereby effectively discouraging greenwashing practices. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1A:

Analyst coverage is negatively related to the extent of corporate ESG greenwashing.

On the contrary, analyst coverage may promote corporate ESG greenwashing through its pressure effect [57]. When companies fall short of earnings forecasts, they face negative market reactions and managerial reputation damage [53], making meeting analysts’ expectations a critical performance benchmark. Under such pressure, managers are compelled to trade off long-term value for short-term results, resulting in myopic behavior. Substantial evidence shows that analyst pressure distorts corporate decisions [31]. Survey data reveals that most CFOs would sacrifice long-term value to protect their personal wealth and career prospects [58]. Under such pressure, firms tend to reduce investments in social responsibility [59] and environmental initiatives. For instance, research using U.S. EPA data demonstrates that companies increase pollution emissions when cutting environmental spending to meet earnings targets [24], indicating that satisfying analysts takes precedence over environmental protection. Furthermore, to maintain access to management, analysts may remain silent about negative ESG developments, effectively accommodating corporate greenwashing. Thus, to the extent that earnings forecasts create short-term pressure and exacerbate managerial myopia, analyst coverage can inadvertently encourage ESG greenwashing. Accordingly, the opposite research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1B:

Analyst coverage is positively related to the extent of corporate ESG greenwashing.

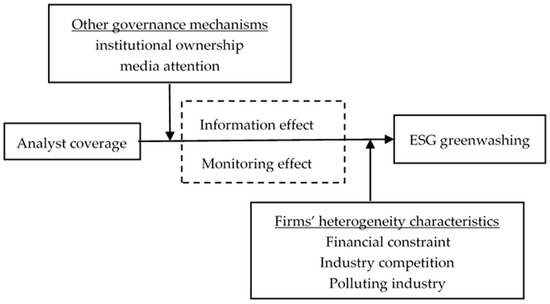

Based on the theoretical framework outlined above, Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model guiding this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Sample and Model Development

3.1. Sample and Data Sources

This study is based on a panel data of firms listed on China’s A-share markets from 2011 to 2021. To construct a robust dataset, we excluded firms in the financial and insurance sectors, company-year entries with missing data for core variables, and entities under special treatment (ST). The resulting sample comprises 1395 unique companies, yielding 10,246 firm-year observations. Following common practice in financial econometrics, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the impact of outliers. Data on analyst coverage and corporate financials were sourced from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. Measures of ESG disclosure quality were drawn from Bloomberg, whereas the Huazheng (Sino-Securities) Database provided the underlying ESG performance scores.

3.2. Variables Definition

3.2.1. Explained Variable

The main dependent variable we focus on is the peer-relative ESG greenwashing score. Following Yu, Van Luu and Chen [7], Zhang [8], we defined corporate “ESG greenwashing” as firms seeking to create an image by disclosing selected ESG data but performing poorly in their actual ESG performance. To quantify corporate ESG greenwashing, we construct a peer-relative measure based on the discrepancy between a firm’s standardized ESG disclosure level (proxied by the Bloomberg ESG disclosure score) and its actual ESG performance (measured by the Huazheng ESG score). This approach captures the extent to which firms overstate their environmental, social, and governance commitments relative to industry peers. This measure is formally defined as follows:

where represents ESG disclosure scores with the average value and standard deviation , represent ESG performance scores with the average value and standard deviation . In Formula (1), ESG greenwashing is calculated with the difference between the scaled ESG disclosure scores and the scaled ESG performance scores. The value directly measures the extent of corporate ESG greenwashing.

3.2.2. Dependent Variable

Our proxy for analyst coverage, Cov1, quantifies the intensity of external monitoring by counting the unique analysts who released earnings forecasts for the firm in the last fiscal year. Following Ali and Hirshleifer [60] and Zhang and Wu [61], when an analyst issued multiple forecasts during this period, only the most recent one is retained. To further ensure robustness, we adopt the total count of earnings forecast reports (Cov2) as an additional metric for analyst coverage.

3.2.3. Control Variables

According to previous relevant studies [7,8,15,62], our model controls for a range of firm-level financial, governance, and external monitoring factors that may influence firm’s ESG greenwashing. Financial controls include firm size (Size), leverage (Lev), profitability (ROA), and growth opportunities (Growth). Governance variables encompass CEO duality (Dual), ownership concentration (Top1_ownership), board independence (Board_Independence), and the share of state ownership (State). External monitoring is accounted for through institutional ownership (Inst), firm age (Age), and whether the firm is audited by a Big Four auditor (Big4_auditor). Industry and year fixed effects are controlled for in all regressions. All variable definitions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions and measures of main variables.

3.3. Empirical Model Design

To analyze the impact of analyst coverage on corporate ESG greenwashing, we estimate the following model (Equation (2)):

where ESG greenwashing represents the degree of a firm’s ESG greenwash and Cov represents an indicator of analyst coverage. To ensure the robustness of our results, two measurement methods were employed, which, respectively, evaluated the number of analysts paying attention and the degree of their efforts devoted to firm i, where Controls denotes a vector of all control variables. Our models include industry and year fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity across sectors and to mitigate the influence of economy-wide temporal shocks, with i and t indexing firms and years, respectively. Standard errors ε are robust and clustered at the firm level. In Equation (2), the coefficient β1 on Cov is the parameter of interest. A significantly negative estimate of β1 would suggest that analyst coverage mitigates corporate ESG greenwashing, while a positive estimate would imply an enhancing effect.

3.4. Summary Statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for the main variables. The mean value of ESG greenwashing is −0.022, with a standard deviation of 1.149, and the variable ranges from −2.289 to 3.283. These figures suggest that while the average level of greenwashing in the sample is relatively low, the phenomenon of ESG greenwashing is common in Chinese-listed companies, and there is a large gap between different enterprises. Our descriptive statistics for ESG greenwashing are comparable to those reported by Zhang [59] and Zhang [63] (mean = −0.019, SD = 1.224). The mean values of board independence variables Cov1 and Cov2 are 11.578 and 25.463, respectively, which is similar to the previous study of Zhang [64] This indicates that Chinese-listed companies have received different degrees of analyst coverage. The remaining variables exhibit distributions consistent with typical empirical ranges.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

The primary regression results, which explore the link between analyst coverage and ESG greenwashing, are summarized in Table 3. The analysis reveals a statistically significant negative association: both measures of analyst coverage (Cov1: β = −0.004, p < 0.01; Cov2: β = −0.001, p < 0.05) are inversely related to the level of corporate greenwashing, as detailed in columns (1) and (2) of the table. These results support the hypothesis H1A, and the economic impact of analyst monitoring is pronounced. A rise in analyst coverage by one standard deviation (about 12.286 analysts) is associated with a 0.0491 unit decrease in the greenwashing. This magnitude is equivalent to approximately 4.3% of the standard deviation of the greenwashing measure itself, confirming that the deterrence effect is not merely statistical but substantial in economics. Consistent with prior research, these results further illustrate that analyst coverage monitors corporate decision-making and uncovers a firm’s misconduct [20]. Extending beyond the literature on social performance in employee welfare, work-related injury rate [23], and emission of toxic pollutants [22] of analyst coverage, our research extends this line of inquiry by demonstrating, within a comprehensive ESG framework, that analyst coverage also constrains broader forms of corporate misconduct.

Table 3.

The effect of analyst coverage on corporate ESG greenwashing.

4.2. Addressing Endogeneity

4.2.1. Two-Stage Least Squares Regression with Instrumental Variables

The regression results may suffer from endogeneity issues. Firms with more ESG engagement and ethical behavior may attract analyst coverage; moreover, analysts might systematically avoid covering firms perceived as socially irresponsible or operating in “sin” industries [65]. To address this potential selection bias, we use the event of whether a firm is added to the CSI300 index as our instrumental variable. According to the prior literature, inclusion to the CSI 300 index will increase a firm’s visibility and attract more analyst attention. CSI300 constituent stocks have more following analysts. However, whether they are added to the CSI 300 has no direct relationship with the firms’ ESG greenwashing. HS300 is a binary indicator that equals 1 if a firm is newly included in the CSI 300 index during the sample period, and 0 otherwise.

Following Lei, et al. [66] and Zhang and Wang [67], we employ expected analyst coverage as an instrumental variable. Broker size—proxied by the number of employed analysts—reflects business performance and is plausibly exogenous to firm-level ESG greenwashing. To construct this instrument, we first record the number of analysts in each brokerage during a benchmark year. We then scale this figure by the broker’s subsequent analyst growth and finally aggregate across all brokers covering the firm to obtain its total expected analyst coverage.

where denotes the expected analyst coverage of firm i by broker j in year t. This measure is constructed using the number of analysts employed by broker j in year t ( relative to that in a benchmark year 0 ), scaled by the actual coverage of firm I by broker j in year 0 (. Aggregating across all brokers yields the total expected coverage for firm I in year t, denoted as . Following He and Tian [31], we use the beginning year of our sample (2011) as the benchmark year, which requires that a firm be covered by at least one analyst report in the year 2011. The 2SLS estimation results are presented in Table 4. columns (1) and (3) show significantly positive coefficients on HS300 for both Cov1 and Cov2, indicating that inclusion in the CSI 300 index enhances analyst coverage. In columns (2) and (4), the coefficients on ESG greenwashing are negative and significant (−0.053 and −0.021, respectively). The associated Cragg–Donald Wald F-statistics (107.2 and 88.18) surpass the common threshold of 10, suggesting the instruments are strong. column (5) reports a positive and significant coefficient on Exp_cov (β = 0.074, p < 0.01), supported by a high F-statistic of 435.62. The second-stage estimate for Cov1 remains significantly negative (β = −0.012, p < 0.05). Collectively, these findings alleviate endogeneity concerns and reinforce a causal link between analyst coverage and reduced ESG greenwashing.

Table 4.

Instrumental variables tests.

4.2.2. A Quasi-Natural Experiment

Referring to the research of Lei, Guo and Fu [66] and Zhang and Wang [67], to capture exogenous variation in analyst coverage, we employ brokerage closures and mergers as exogenous shocks that disrupt established coverage patterns, thereby enabling causal inference regarding the effect on corporate ESG greenwashing. The brokerage closures and mergers are mainly affected by their business ability and industry factors; they have nothing to do with the traits of listed companies covered by the analysts, which provides a suitable quasi-natural experiment for the relevant research about analyst coverage. From 2011 to 2021, we identified the brokerage list from the CSMAR database year by year to determine the brokerages that disappeared, and by searching through Baidu to confirm the events. Finally, we find six brokerage merger events during our research interval, with 60 listed firms affected. The treatment group comprises firms whose analyst coverage declines following brokerage mergers. A control group is then constructed, consisting of firms with similar fundamental characteristics but unaffected by such coverage reductions. Propensity score matching (PSM) based on variables such as size, leverage, age, return on assets, and growth was used to construct the control group. Next, a difference-in-differences (DID) framework is employed to examine how reductions in analyst coverage affect corporate ESG greenwashing. The Treated represent the firms which are affected by the merger events; Post is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for the period after the event, and 0 otherwise. Our interest term is DID, which measures the real impact of analyst reduction on corporate ESG greenwashing. The coefficient on the DID term in column (1) of Table 5 is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05), which reveals that the exogenous shock causing the dropping of analyst coverage does increase the corporate ESG greenwashing.

Table 5.

The result of the quasi-natural experiment.

Following Chen, et al. [68] and Lei, Guo and Fu [66], to test the parallel trends assumption underlying our DID design, we conduct an event study analysis. The results, presented in column (2) of Table 5, are as follows: the coefficients of Treated × Pre2 and Treated × Pre1 are insignificant, illustrating that before the brokerage merger event, causing analyst coverage decrease, the difference between the treated and the control group is not significant. In contrast, the coefficients of Treated × Post1 and Treated × Post2 are significantly positive, illustrating that after the brokerage merger event, causing analyst coverage decrease, it indeed has an impact on corporate ESG greenwashing. The differences between the pre and after events confirm the validity of the DID method.

4.2.3. Heckman Selection Model

To address potential sample selection bias, we employ the Heckman two-step procedure. In the first stage, we include the instrument variable of HS300 and all control variables, combining the analyst coverage dummy variables to construct a probit regression to obtain the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). A binary indicator is set to 1 if the firm is covered by analysts, and 0 otherwise. In the second stage, the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) estimated from the selection equation is incorporated into the baseline specification as a control variable and re-estimates the coefficients of Cov1 and Cov2. The Heckman selection model results present in Table 6, columns (1) and (2), validate the existence of sample selection bias, as evidenced by the significant IMR. Nonetheless, after this correction, the negative and significant coefficients on Cov1 and Cov2 persist, underscoring the robustness of the main relationship.

Table 6.

Heckman and entropy balancing tests of analyst coverage effect.

4.2.4. Entropy Balance Test

To strengthen the results’ robustness, we employ entropy balancing to address potential disparities in analyst coverage between the experimental group and the control group. Following the approach outlined by Hainmueller [69], this method relaxes many of the parametric restrictions required by conventional matching techniques and provides improved covariate balance. Specifically, we weight control group observations using a logistic model that incorporates all covariates from our baseline specification, then conduct regression analysis on the matched sample. As shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 6, the results obtained from the entropy-balanced sample remain consistent with our main findings. This additional test further supports the robustness of our results.

4.3. Tests for Robustness

4.3.1. Change Measurement of Analyst Coverage

To further verify our findings, we re-estimate the empirical model using two other measures of analyst coverage: Cov1 is constructed as the natural logarithm of (1 + the annual count of analysts following the firm); Cov2 is calculated analogously, using the natural logarithm of (1 + the total annual number of analyst reports). As shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7, the key coefficients continue to hold their significance and direction with the baseline findings, confirming the robustness of our conclusions.

Table 7.

Robustness checks.

4.3.2. Change Measurement of ESG Greenwashing

We reconstruct the ESG greenwashing measure using ESG scores sourced from the Wind database. As presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 7, the results based on this alternative measurement remain consistent with our main findings.

4.3.3. Eliminate Samples Without Analyst Coverage

To address potential sample selection concerns, we exclude firms with no analyst coverage from the regression sample. Results displayed in columns (5) and (6) of Table 7 remain qualitatively unchanged.

4.3.4. Placebo Test

To address potential concerns regarding spurious correlation, we follow the approach of randomly matching the Cov1 and Cov2 to the company code to test the validity. Finally, regression was performed on Equation (2) again. If placebo effects exist, Cov1 and Cov2 treatments should still positively correlate with the target firm’s ESG greenwashing, driven by unperceived study design limitations. The results are presented in Table 7, columns (7) and (8). The ESG greenwashing coefficient is not significant, this suggests the absence of a placebo effect, thereby further supporting the robustness of our conclusions.

5. Further Research

5.1. Mechanism Tests

5.1.1. Information Effect

Financial analysts serve as critical information intermediaries in capital markets, mitigating information asymmetry between corporate insiders and external investors [70,71,72]. By gathering information through public and private channels, analysts generate incremental, high-quality insights that are valued by investors [73]. Moreover, their ability to uncover and reveal negative corporate information [53] helps lower information opacity, thereby constraining managerial opportunism. Through this informational mechanism, analyst coverage reduces the likelihood of corporate ESG greenwashing.

We follow in using Opaque to measure corporate information transparency, where a higher value indicates greater information opacity. The interaction terms reported in Table 8 columns (1) and (2), Opaque × Cov1 and Opaque × Cov2 are both significantly negative (coefficients = −0.011 and −0.004, respectively; p < 0.1 and p < 0.01). These results support the information mechanism: by enhancing information transparency, enhanced analyst coverage mitigates information asymmetry and consequently raises the probability of detecting managerial misconduct in ESG practices.

Table 8.

The results of mechanism tests.

5.1.2. Monitoring Effect

Beyond the information role, analysts further serve as external monitors that mitigate agency problems. Evidence shows they help detect corporate fraud [20], curb excessive CEO pay [17], and constrain earnings management [18,19]. Through this monitoring function, analysts deter opportunistic behavior by raising the detection risk of ESG manipulation, thereby reducing firms’ propensity for ESG greenwashing.

Consistent with Dechow, et al. [74], we measure earnings management using the modified Jones model, defined as the absolute value of discretionary accruals (total accruals minus non-discretionary accruals). The estimated coefficients on the interaction terms, presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 8, are as follows: ABDA×Cov1 and ABDA×Cov2 are both significantly negative (coefficients = −0.301 and −0.258, respectively; p < 0.1), supporting our monitoring hypothesis that analyst scrutiny reduces firms’ capacity to use accounting discretion for ESG greenwashing.

5.2. Moderating Effects of Other Governance Mechanisms

5.2.1. Institutional Ownership

Institutional investors, acting as sophisticated market participants, serve a crucial monitoring function in alleviating corporate agency issues [75]. Driven by the pursuit of both financial and social returns, they engage actively in assessing corporate non-financial performance [76]. Evidence shows institutional ownership improves CSR performance [77], enhances ES scores globally [78], and reduces carbon emissions [79]. Consequently, in firms with substantial institutional ownership—where external governance is already strong—analyst coverage provides limited incremental power in curbing ESG greenwashing.

Our analysis further considers the interactive influence of institutional ownership, testing how it conditions the main relationship under study. We partition the sample annually according to the median level of institutional ownership. The results are reported in columns (1) and (2) of Table 9; the coefficients of Cov1 × Inst and Cov2 × Inst are 0.084 and 0.078, respectively, both significant positive. In line with the previous findings on institutional investors’ concern about corporate non-financial performance. This validates the moderating role of institutional ownership, revealing that analyst coverage functions as a more potent restraint against ESG greenwashing in firms with weaker institutional oversight. This pattern implies that the monitoring role of analysts becomes particularly salient when alternative governance mechanisms are relatively weaker.

Table 9.

Moderation role of other corporate governance mechanisms.

5.2.2. Media Attention

As an external governance mechanism, media scrutiny significantly influences corporate ESG practices through its dual function as information intermediary and reputation monitor [80,81,82,83,84,85]. By reducing information asymmetry and directing public attention to corporate behavior, media coverage creates stakeholder pressure that promotes sustainable initiatives while deterring misconduct. Empirical studies confirm that negative media exposure reduces corporate environmental violations [86] and motivates improved performance through heightened public and regulatory scrutiny [87]. When media exposure reveals ESG misconduct, it damages corporate reputation and impacts executive career prospects and compensation arrangements [88,89]. Consequently, in firms subject to intensive media monitoring—where external oversight is already well-established—analyst coverage demonstrates a diminished incremental effect in curbing ESG greenwashing. This pattern suggests a substitution relationship between governance mechanisms, where robust monitoring by one reduces the marginal benefit of additional oversight by others.

We examine media attention as a key boundary condition that may alter the strength of the relationship between analyst coverage and ESG misconduct; the measure of media attention is calculated by applying a log transformation to the yearly count of news reports focused on the firm, specifically as ln (1 + total news count). The full sample is stratified into two groups—high versus low media attention—dichotomized by the annual median value of the metric. Media attention data are obtained from the Chinese Research Data Services Platform (CNRDS), a leading database in this research context. Table 9 presents these findings in columns (3) and (4). The significantly positive interaction terms between Media attention and analyst coverage (Media attention × Cov1 and Media attention × Cov2) provide evidence supporting our hypothesis that the restraining effect of analyst coverage on greenwashing is conditional on the media environment, being significantly weakened in firms under heightened media attention. This suggests that analysts’ influence on ESG greenwashing becomes more substantial when alternative external monitoring is less intensive.

5.3. Heterogeneity Tests

5.3.1. Financial Constraints

Financial constraints can lead firms to curtail investments with limited short-term returns, potentially creating negative externalities. Firms faced with financial constraints do not have the ability to invest in ESG programs. Xu and Kim [90] found that, resulting from decreased investment in pollution abatement, firms that face financial constraint emit more toxic pollution. By mitigating financial pressures, firms are incentivized to adopt more proactive environmental management practices, including robust pollution abatement and regulatory compliance [91]. Previous studies have established that analysts contribute to lowering firms’ costs of both debt and equity [92,93]. If analyst coverage facilitates the firms’ access to external financial opportunities, it is reasonable to anticipate that the constraining effect of analyst scrutiny on ESG greenwashing is particularly evident among firms facing significant financial constraints

To examine this argument, referring to Hadlock and Pierce [94], financial constraints are measured using the SA index, where a higher index value corresponds to greater financial constraint severity. The results are presented in Table 10. The significantly negative interaction terms between financial constraints and analyst coverage (SA × Cov1 and SA × Cov2) demonstrate that the influence of analyst coverage in curbing ESG greenwashing is particularly substantial for firms under significant financial constraints.

Table 10.

The results of heterogeneity Tests.

5.3.2. Industry Competition

Previous studies have suggested that in the fierce market competition, firms regard ESG performance as a competitive strategy, and competition increases will promote managers who perceive ESG practices as a means of profit maximization to invest more in ESG and promote firms’ ESG performance [95]. Firms with bad financial conditions are significantly incentivized by ESG greenwashing in intense competition. The analyst’s deep understanding of the ESG information will uncover the firm’s strategic ESG behavior and inhibit enterprise ESG greenwashing.

We divide heavy competition industries based on the revenue to calculate the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) [96]. If the corporation is in a heavy competition industry, the dummy variable HHI equals 1, otherwise 0. These findings are presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 10. The significantly positive interaction terms between industry competition and analyst coverage (HHI × Cov1 and HHI × Cov2) indicate that analyst coverage exerts a stronger inhibitory effect on ESG greenwashing among firms in highly competitive industries

5.3.3. Polluting Industry

Previous studies indicate that companies’ propensity to engage in greenwashing varies across industries [97]. Firms in heavily polluting industries face substantial pollution abatement costs and must comply with stringent environmental regulations, whereas those in less polluting industries encounter comparatively fewer challenges [8]. To gain legitimacy, companies in environmentally and socially controversial industries are more inclined to disclose corporate social responsibility (CSR) information strategically, often exaggerating their actual performance. Consequently, analysts are likely to intensify their scrutiny of ESG performance in high-pollution industries, thereby exerting a restraining effect on corporate ESG greenwashing practices in these sectors.

Following Hu, Hua, Liu and Wang [97], heavy-pollution industries are classified according to the Guidelines for Environmental Information Disclosure of Listed Companies (2010), which designates 16 sectors: thermal power, steel, cement, electrolytic aluminum, coal, metallurgy, chemical engineering, petrochemicals, building materials, papermaking, brewing, pharmaceuticals, fermentation, textiles, leather manufacturing, and mining as heavily polluting. With regards to Polluting_Ind, this binary indicator is coded as 1 for firms operating in any of these sectors, and 0 otherwise. As reported in Table 10 (columns 5–6), the significantly negative interaction terms between polluting industry and analyst coverage (Polluting_Ind × Cov1 and Polluting_Ind × Cov2), which implies that analysts exert a stronger disciplinary effect on ESG greenwashing in firms operating within heavily polluting industries.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

The “dual carbon” targets in China have expedited the integration of ESG practices among corporations, yet they have also spurred a rise in greenwashing. Such practices mislead stakeholders and erode long-term value, underscoring the critical need to identify governance mechanisms that can effectively curb ESG greenwashing and to catalyze the achievement of genuine sustainability outcomes.

This study analyzes the effect of analyst coverage on ESG greenwashing using a sample of Chinese A-share listed firms from 2011 to 2021. The empirical results reveal that greater analyst coverage significantly curtails ESG greenwashing in Chinese firms through both monitoring and information effects. A series of robustness and endogeneity checks corroborate our results. These findings align with the view that analysts serve as an external governance mechanism in the corporate non-financial governance decisions. Furthermore, the restraining effect of analyst coverage is moderated by other governance forces; it weakens under high institutional ownership or media attention, indicating a substitutive relationship among multiple governance mechanisms. Furthermore, this effect is particularly strong among firms under significant financial constraints, in highly competitive environments, or within heavily polluting sectors.

6.2. Implications

The results provide practical guidance for stakeholders seeking to achieve the transparency and credibility of ESG reporting:

First, for firms, it is essential to recognize that authentic ESG integration, rather than selective disclosure, forms the foundation for sustainable competitive advantage. Management should institutionalize ESG practices throughout operational and strategic processes, moving beyond symbolic reporting. Second, for investors and analysts, our results underscore the critical importance of scrutinizing the substance behind ESG disclosures. Developing stronger capabilities to assess greenwashing risks is necessary for accurate corporate valuation and investment decision-making. Third, for regulators, ESG has developed rapidly in China; however, the development of policies and regulatory frameworks lags behind the rapid evolution of ESG practices. Our findings highlight the urgent need to complement China’s current ESG policy framework with mandatory disclosure standards, third-party assurance mechanisms, and clear penalties for misrepresentation. Such measures would significantly raise the credibility of corporate ESG reporting.

6.3. Reflections on Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the results are particularly relevant to China’s context, where rapid ESG growth coexists with underdeveloped regulatory frameworks. While the governance function of analysts may generalize across markets, China’s unique institutional landscape—including dominant state-owned enterprises and policy-driven governance—may moderate its effects. A central question for subsequent research is the boundary conditions of these relationships—specifically, whether they persist across emerging economies with different regulatory traditions and market structures. We mainly focus on the pre-pandemic era, which may limit the immediate generalizability of our results to the post-pandemic landscape, which is shaped by accelerated regulatory changes and heightened market expectations. We explicitly encourage future research to build upon our baseline findings by replicating this analysis with post-2020 data, which would offer valuable insights into how exogenous shocks and regulatory leaps moderate the governance–ESG nexus. Furthermore, while consistent with methodological conventions, our use of analyst following as a proxy fails to capture individual-level heterogeneity. Subsequent research could incorporate qualitative methods—such as interviews with analysts and sustainability officers—to better uncover the underlying mechanisms through which monitoring influences corporate ESG decisions. Such mixed-method approaches would complement large-sample evidence with nuanced insights into causal pathways. Looking forward, the rapid development of financial technology offers compelling new research directions. Future studies could investigate how AI-driven ESG rating systems and algorithm-based trading platforms are transforming corporate monitoring mechanisms. These technological forces may fundamentally reshape the information environment in which analysts operate, potentially creating new pathways—or obstacles—for effective ESG governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.; methodology, C.Z.; software, C.Z.; validation, C.Z.; formal analysis, C.Z.; investigation, C.Z.; resources, C.Z.; data curation, C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.Z.; visualization, C.Z.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, X.W. funding acquisition, C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

(1) This project is funded by the doctoral research project of Beihua University: the research of analyst coverage impact on corporate sustainable development (160325166). (2) This project was funded by the 2025 university-level research project on educational and teaching reform project of Beihua University, titled “Research on the Development and Practice of Financial Management Courses Integrating Environment, Society and Governance (ESG) in the Context of New Liberal Arts Construction”. (3) This project was funded by the 2025 annual university-level research project on educational reform for graduate students at Beihua University: titled “Research on the Mechanism for Cultivating Academic Innovation Ability of Graduate Students in Accounting under the backdrop of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG)” (JG[2025]040).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank editors and reviewers for their comments and suggestions that greatly improved our studying.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shen, H.; Feng, H.; Xiao, Q.; Ma, S.; Guo, H. Research on the Dual Effects of Corporate Physical and Transition Climate Risks on Total Factor Productivity. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2025, 61, 4247–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zeng, G.; Zhao, Y. Digital finance and corporate ESG performance: Empirical evidence from listed companies in China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 79, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why is Corporate Virtue in the Eye of The Beholder? The Case of ESG Ratings. Account. Rev. 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; de Sousa-Filho, J.M. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y.J. A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunandan, A.; Rajgopal, S. Do socially responsible firms walk the talk? J. Law. Econ. 2024, 67, 767–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.-y.; Van Luu, B.; Chen, C.H. Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 52, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Environmental regulation and firm product quality improvement: How does the greenwashing response? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 80, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, A.; Saleh, A.; Eliwa, Y. Does mandating ESG reporting reduce ESG decoupling? Evidence from the European Union’s Directive 2014/95. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 1305–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, A.; Smeets, P. Why do investors hold socially responsible mutual funds? J. Financ. 2017, 72, 2505–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janney, J.J.; Gove, S. Reputation and Corporate Social Responsibility Aberrations, Trends, and Hypocrisy: Reactions to Firm Choices in the Stock Option Backdating Scandal. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1562–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrón-Vílchez, V.; Valero-Gil, J.; Suárez-Perales, I. How does greenwashing influence managers’ decision-making? An experimental approach under stakeholder view. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 860–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, W.N.; Seppanen, V.; Koivumaki, T. How and when does perceived greenwashing affect employees’ job performance? Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1722–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Montgomery, A.W.; Ozbilir, T. Employees’ response to corporate greenwashing. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 4015–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Aboud, A.; Saleh, A. Board gender diversity and ESG decoupling: Does religiosity matter? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 4046–4067. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.P.; Li, W.A.; Meng, Q.K. Influence of distracted mutual fund investors on corporate ESG decoupling: Evidence from China. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Harford, J.; Lin, C. Do analysts matter for governance? Evidence from natural experiments. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.F. Analyst coverage and earnings management. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 88, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, R.M.; Oesch, D. Analyst coverage and real earnings management: Quasi-experimental evidence. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2016, 51, 589–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Morse, A.; Zingales, L. Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? J. Financ. 2010, 65, 2213–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Qasem, A.; Aripin, N.; Ariffin, M.S.M. Corporate Responsibility Disclosure, Information Environment and Analysts’ Recommendations: Evidence from Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Keasey, K.; Lim, I.; Xu, B. Analyst Coverage and Corporate Environmental Policies. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. Forthcom. 2022, 59, 1586–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Mao, C.X.; Zhang, C. Does Analyst Coverage Affect Workplace Safety? Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 3464–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Yao, W.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, W. Meet, beat, and pollute. Rev. Account. Stud. 2022, 27, 1038–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Dasgupta, S.; Hilary, G. Analyst coverage and financing decisions. J. Financ. 2006, 61, 3009–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xie, L.; Zhang, Y. How does analysts’ forecast quality relate to corporate investment efficiency? J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 43, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, T.Y.; Navone, M.; Wu, E. Analyst coverage and the quality of corporate investment decisions. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 51, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Analyst reputation and management earnings forecasts. J. Account. Public. Policy 2021, 40, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tong, L.; Su, J.; Cui, Z. Analyst coverage and corporate social performance: Evidence from China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2015, 32, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.J.; Tian, X. The dark side of analyst coverage: The case of innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 109, 856–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhong, X.; Wan, L. Missing analyst forecasts and corporate fraud: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 181, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, H.; Lin, L.; Hu, D.J.J.; Liu, H. ESG standards in China: Bibliometric analysis, development status research, and future research directions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, R.; Sam, A.G. Voluntary Pollution Reductions and the Enforcement of Environmental Law: An Empirical Study of the 33/50 Program. J. Law Econ. 2008, 51, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.W.; Goodell, J.W.; Shen, D.H. ESG rating and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Du, H.Y.; Yu, B. Corporate ESG performance and manager misconduct: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 82, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Shen, H.; Guo, H. Research on the impact of ESG scores on corporate substantive and strategic green innovation. Innov. Green. Dev. 2025, 4, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.F.; Shan, H.Y. Corporate ESG Profiles and Banking Relationships. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 35, 3373–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Aboud, A.; Saleh, A. ESG practices and the cost of debt: Evidence from EU countries. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2021, 79, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.Y.; Guo, C.Q.; Luu, B.V. Environmental, social and governance transparency and firm value. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Nozawa, W.; Yagi, M.; Fujii, H.; Managi, S. Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Han, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.L.; Zhao, X.J. ESG investment in China: Doing well by doing good. Pac.-Basin. Financ. J. 2023, 77, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; Gong, M.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Koh, L. The impact of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on firm value: The role of CEO power. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Shi, B.J.; Song, Y.L.; Wu, H. ESG performance and loan contracting in an emerging market. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Kirkerud, S.; Theresa, K.; Ahsan, T. The impact of sustainability (environmental, social, and governance) disclosure and board diversity on firm value: The moderating role of industry sensitivity. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Lyon, T.P. Strategic environmental disclosure: Evidence from the DOE’s voluntary greenhouse gas registry. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 61, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F.; Ntim, C.G. Environmental Policy, Sustainable Development, Governance Mechanisms and Environmental Performance. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiemann, F.; Tietmeyer, R. ESG Controversies, ESG Disclosure and Analyst Forecast Accuracy. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Du, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.T. Seeing is believing: Analysts’ corporate site visits. Rev. Account. Stud. 2016, 21, 1245–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Du, F.; Wang, B.Y.T.; Wang, X. Do Corporate Site Visits Impact Stock Prices? Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Lim, T.; Stein, J.C. Bad news travels slowly: Size, analyst coverage, and the profitability of momentum strategies. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T. The Importance of Climate Risks for Institutional Investors. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1067–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, R.J.; Shen, W. The impacts of performance relative to analyst forecasts and analyst coverage on firm R&D intensity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, D.; Gokkaya, S.; Liu, X.; Xie, F. Are all analysts created equal? Industry expertise and monitoring effectiveness of financial analysts. J. Account. Econ. 2017, 63, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Harvey, C.R.; Rajgopal, S. The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J. Account. Econ. 2005, 40, 3–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.L.; Lu, L.Y.; Yu, Y.X. Financial analyst coverage and corporate social performance: Evidence from natural experiments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 2271–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Hirshleifer, D. Shared analyst coverage: Unifying momentum spillover effects. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 136, 649–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, X. Analyst coverage and corporate ESG performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.R.; Qian, H.; Wu, Q.Q.; Han, F. Research on the masking effect of vertical interlock on ESG greenwashing in the context of sustainable Enterprise development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Can environmental monitoring power transition curb corporate greenwashing behavior? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2023, 212, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Analyst coverage and corporate social responsibility decoupling: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Guo, X.M.; Fu, X.F. How Does Analyst Coverage Affect Corporate Social Responsibility? Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 2036–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.R. The bright side of analyst coverage on corporate innovation: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 89, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hung, M.Y.; Wang, Y.X. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainmueller, J. Entropy Balancing for Causal Effects: A Multivariate Reweighting Method to Produce Balanced Samples in Observational Studies. Political Anal. 2012, 20, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.; Li, X. Characteristics of a firm’s information environment and the information asymmetry between insiders and outsiders. J. Account. Econ. 2004, 37, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, A.; Panayides, M. Do financial analysts restrain insiders’ informational advantage? J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2018, 53, 203–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, F.; Kecskés, A. The real effects of financial shocks: Evidence from exogenous changes in analyst coverage. J. Financ. 2013, 68, 1407–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Ljungqvist, A. Testing asymmetric-information asset pricing models. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2012, 25, 1366–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.M.; Sloan, R.G.; Sweeney, A.P. Detecting earnings management. Account. Rev. 1995, 70, 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell, J.C.; Starks, L.T. Institutional investors and executive compensation. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 2351–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Guo, C.; Fan, Y. Institutional investor networks and ESG performance: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2024, 60, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Dong, H.; Lin, C. Institutional shareholders and corporate social responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Lins, K.V.; Roth, L.; Wagner, H.F. Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiullah, M.; Alam, M.S.; Islam, M.S. Do all institutional investors care about corporate carbon emissions? Energ. Econ. 2022, 115, 106376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, J.S.; Hsu, C.; Tang, D.; Wu, C. The role of social media in corporate governance. Account. Rev. 2021, 96, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.S. The press as a watchdog for accounting fraud. J. Account. Res. 2006, 44, 1001–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.X.; McConnell, J.J. The role of the media in corporate governance: Do the media influence managers’ capital allocation decisions? J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 110, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Volchkova, N.; Zingales, L. The corporate governance role of the media: Evidence from Russia. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1093–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.G.; Guo, J. Influence of media coverage and sentiment on seasoned equity offerings. Account. Financ. 2020, 60, 557–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, N.M. The Information Role of the Media in Earnings News. J. Account. Res. 2021, 59, 1021–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipilov, A.V.; Greve, H.R.; Rowley, T.J. Is all publicity good publicity? The impact of direct and indirect media pressure on the adoption of governance practices. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1368–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Tong, L.; Viswanath, P.; Zhang, Z. Word power: The impact of negative media coverage on disciplining corporate pollution. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, M.K. Watchdog or lapdog? A behavioral view of the media as a corporate governance mechanism. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.J. Do Boards Take Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues Seriously? Evidence from Media Coverage and CEO Dismissals. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 176, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Kim, T. Financial constraints and corporate environmental policies. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 35, 576–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.R. Financing conditions and toxic emissions. In SAFE Working Paper Series; Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer, R.C.; Chatfield, R.E.; Sisneros, P.M. Security analyst monitoring activity: Agency costs and information demands. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1989, 24, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, F.; Kecskés, A.; Mansi, S.A. Information asymmetry, the cost of debt, and credit events: Evidence from quasi-random analyst disappearances. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 39, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, C.J.; Pierce, J.R. New Evidence on Measuring Financial Constraints: Moving Beyond the KZ Index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.K.; Yang, Y.C. Market competition and firms’ social performance. Econ. Model. 2020, 91, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, M. Capital structure and product markets interactions: Evidence from business cycles. J. Financ. Econ. 2003, 68, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hua, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C. The green fog: Environmental rating disagreement and corporate greenwashing. Pac-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).