Fourteen-Year-Old Students’ Understanding of Problems Related to Microplastics in the Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

Theoretical Background

- RQ1: Do students achieve more than 50% of all points at the microplastics achievement test?

- RQ2: Do students show low incidence of misconceptions about microplastics and what is the nature of the identified misconceptions?

- RQ3: Are there statistically significant differences between female and male students in their achievements on the microplastics test?

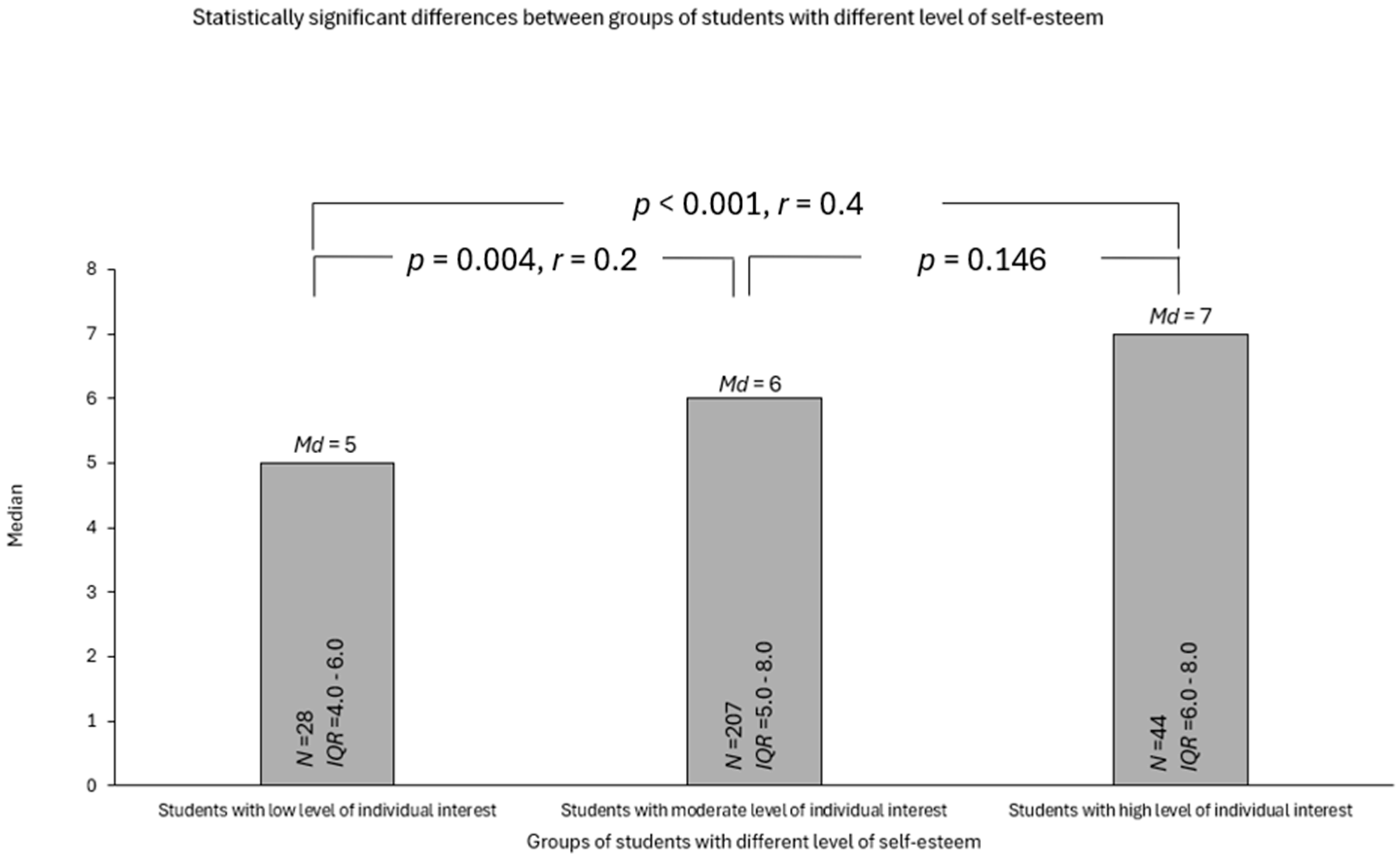

- RQ4: Are there statistically significant differences between students with different levels of individual interest and self-esteem in their achievements on the microplastics test?

- RQ5: Are there statistically significant differences between female and male students in their individual interest and self-esteem for learning about microplastics?

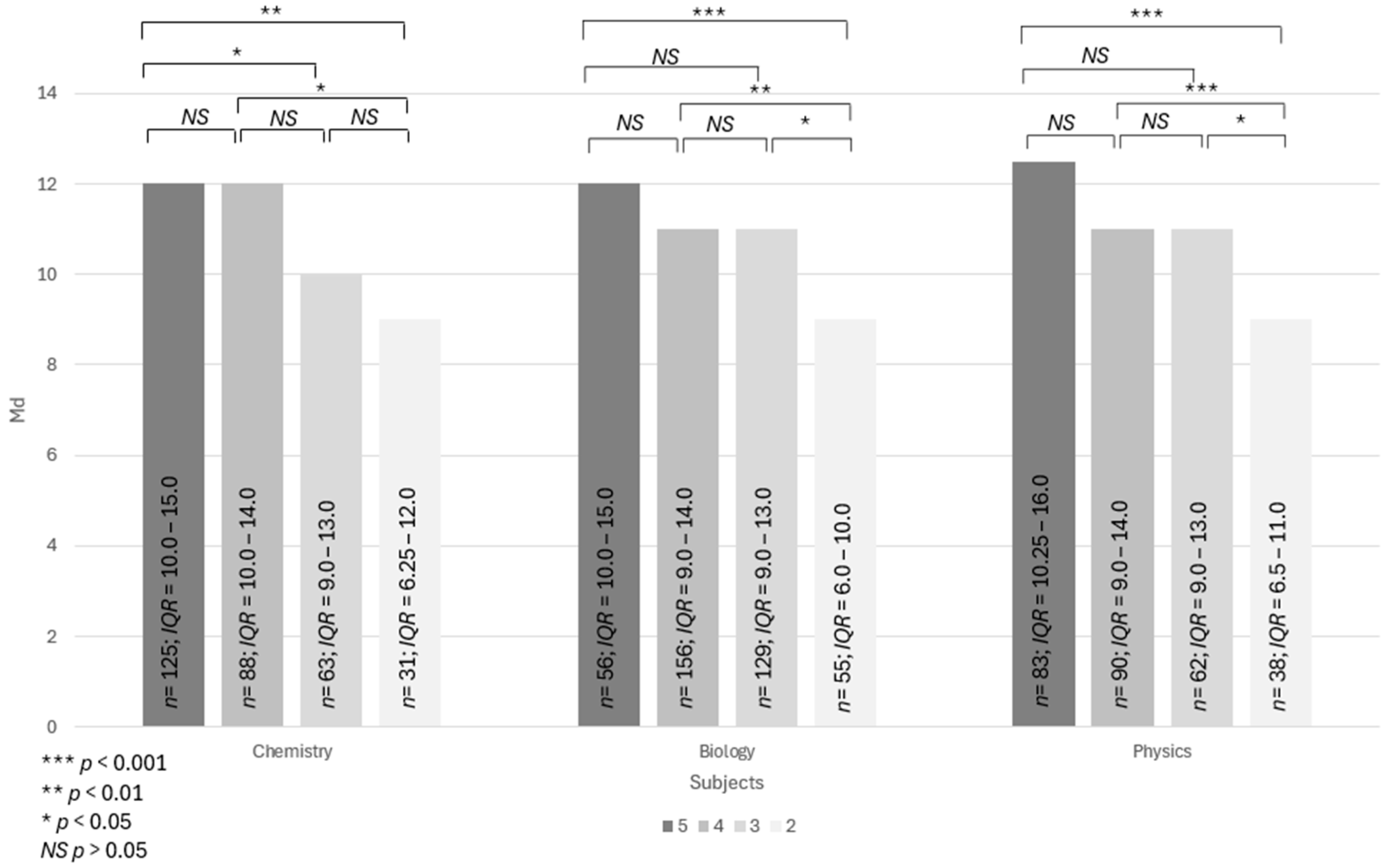

- RQ6: Are there statistically significant differences between students with different biology, chemistry and physics final grade in 8th grade and their achievements on the microplastics test?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

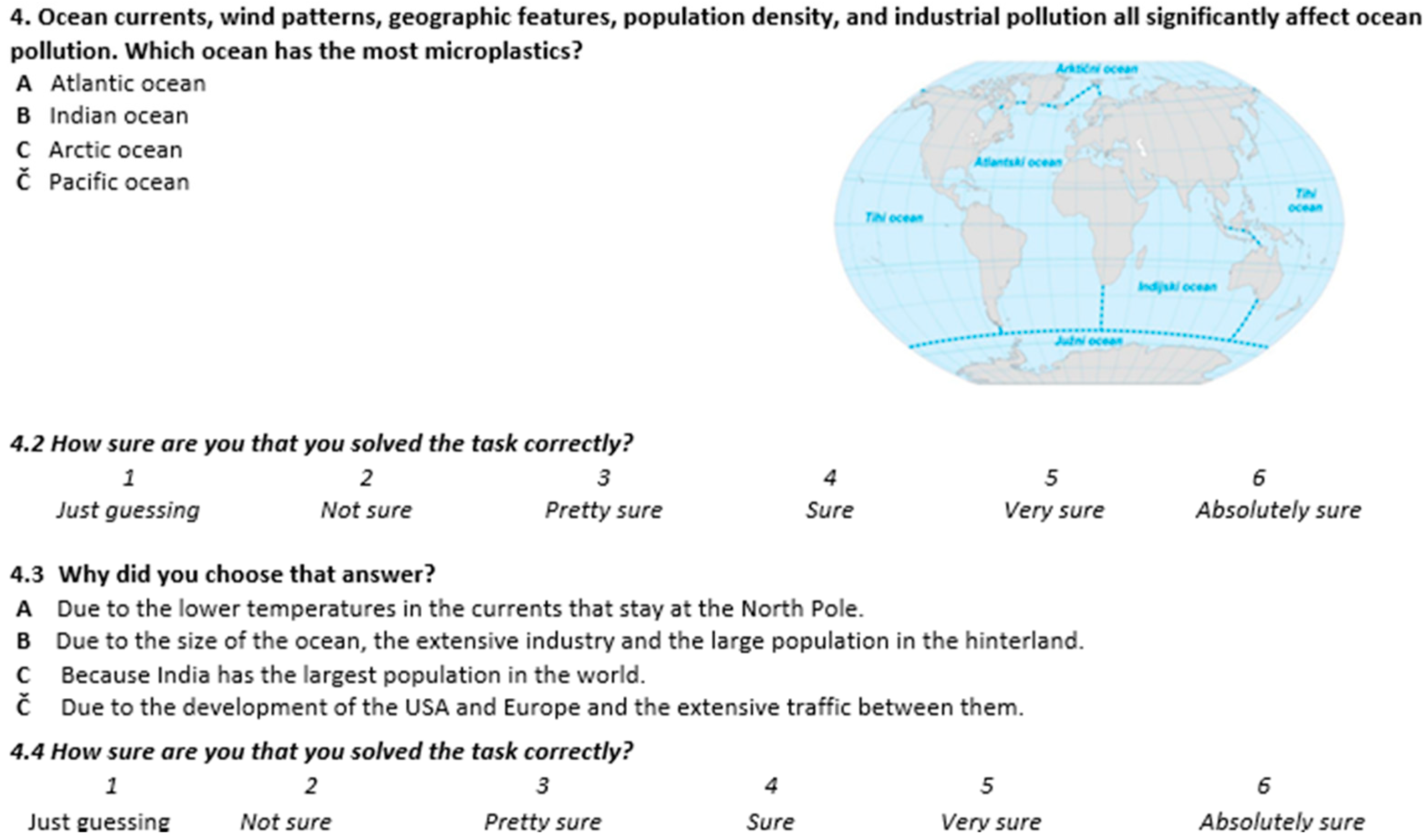

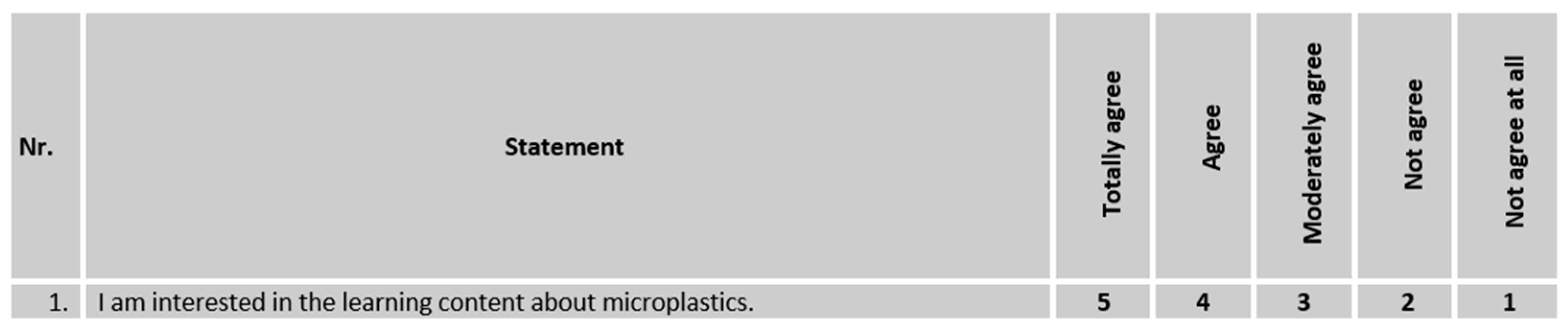

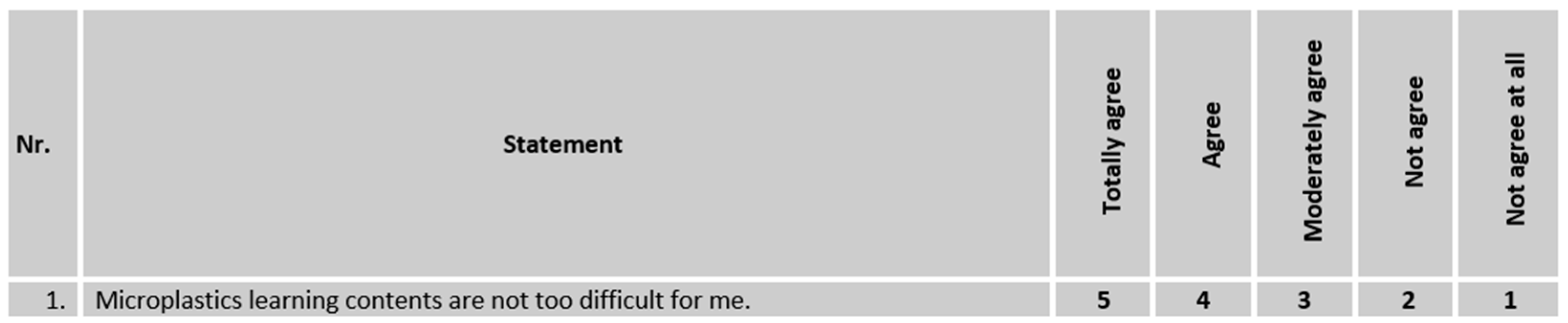

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Research Design

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. RQ1: Students’ Knowledge About Microplastics

3.2. RQ2: Students’ Misconceptions About Microplastics

3.3. RQ3: Male and Female Students’ Knowledge on Microplastics

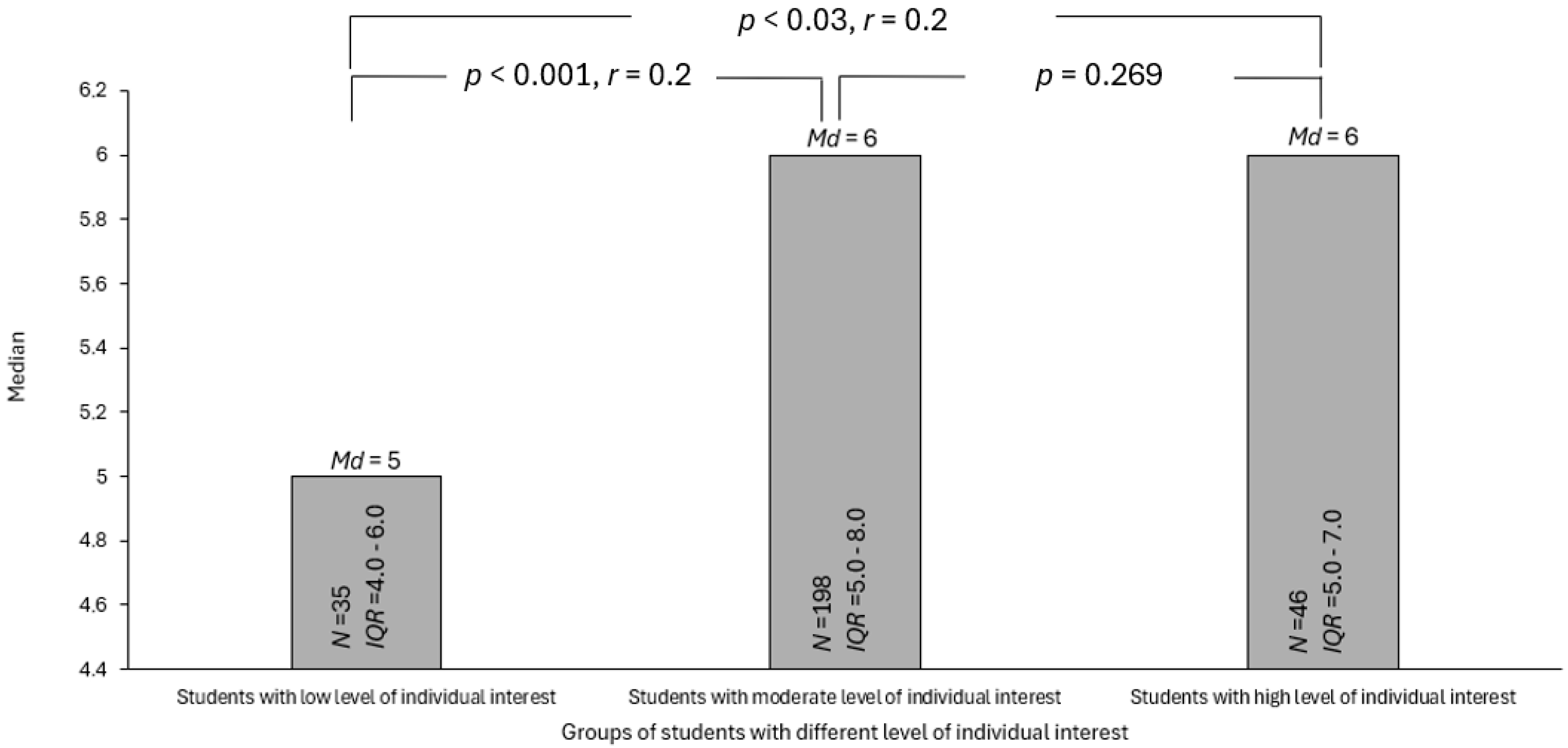

3.4. RQ4: Students’ Individual Interest and Self-Esteem and Their Knowledge on Microplastics

3.5. RQ5: Students Gender and Their Individual Interest and Self-Esteem for Learning the Topic of Microplastics

3.6. RQ6: Students’ Final Grades and Their Knowledge on Microplastics

4. Conclusions

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Guidelines for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zárate Rueda, R.; Beltrán Villamizar, Y.I.; Becerra Ardila, L.E. A Retrospective Approach to Pro-Environmental Behavior from Environmental Education: An Alternative from Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, S.; Eirdosh, D. Behavioral Science and Education for Sustainable Development: Towards Metacognitive Competency. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradač Hojnik, B. Integrating Playful Learning to Enhance Education for Sustainability: Case Study of a Business School in Slovenia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila Echeverry, M.P.; Gauthier, A.; Hartikainen, H.; Vasalou, A. Designing for Digital Education Futures: Design Thinking for Fostering Higher Education Students’ Sustainability Competencies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Shahbaz, P.; Haq, S.u.; Boz, I. Exploring the Moderating Role of Environmental Education in Promoting a Clean Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajj-Hassan, M.; Chaker, R.; Cederqvist, A.M. Environmental Education: A Systematic Review on the Use of Digital Tools for Fostering Sustainability Awareness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, L.; Aagaard, T.; Wiig, A.C. Highlighting Practices and Dialogic Moves: Investigating Simulation-Based Learning in Online Teacher Education. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2025, 51, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hamidian, A.H.; Tubić, A.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.K.H.; Wu, C.; Lam, P.K.S. Understanding Plastic Degradation and Microplastic Formation in the Environment: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 274, 116554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L.; Green, C. Making Sense of Microplastics? Public Understandings of Plastic Pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 152, 110908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Yang, J.E.; Kim, H.; Moon, J.; Ryu, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Effective Environmental Education for Sustainable Development beyond the Plastic Age in South Korea. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 1328–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.R. (Micro)Plastics and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 30, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janouškova, S.; Teplý, P.; Fatka, D.; Teplá, M.; Cajthaml, T.; Hák, T. Microplastics—How and What Do University Students Know about the Emerging Environmental Sustainability Issue? Sustainability 2020, 12, 9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukma, E.; Ramadhan, S.; Indriyani, V. Integration of Environmental Education in Elementary Schools. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1481, 012136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkar, G.; Debevec, V.; Johnson, B.; Manoli, C. Assessing Children’s Environmental Worldviews and Concerns. CEPS J. 2021, 11, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spork, H. Environmental Education: A Mismatch Between Theory and Practice. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 1992, 8, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter-Mackenzie, A.; Smith, R. Ecological Literacy: The ‘Missing Paradigm’ in Environmental Education (Part One). Environ. Educ. Res. 2003, 9, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šorgo, A.; Kamenšek, A. Implementation of a Curriculum for Environmental Education as Education for Sustainable Development in Slovenian Upper Secondary Schools. Energy Educ. Sci. Technol. Part B Soc. Educ. Stud. 2012, 4, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Slovenia. Predmetnik za Osnovno šolo [Curriculum for Elementary School]; Ministry of Education, Science, and Sport: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MVI/Dokumenti/Osnovna-sola/Ucni-nacrti/Predmetnik-OS/Predmetnik-za-osnovno-solo.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Ribič, L.; Devetak, I.; Vošnjak, M. Students’ Understanding of Lithosphere and Pedosphere Concepts at the End of Lower Secondary School in Slovenia. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, J.; Slapničar, M.; Devetak, I. Assessment of the 14- And 15-Year-Old Students’ Understanding of the Atmospheric Phenomena. Acta Chim. Slov. 2019, 66, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Wahab, A.; Mapa, M.T. Profil Literasi Alam Sekitar: Perspektif Pelajar Sekolah Menengah Di Tawau, Sabah. Malaysian J. Soc. Space. 2020, 16, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örs, M. A Measurement of the Environmental Literacy of Nursing Students for a Sustainable Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, P.; Bogner, F.X. Conceptions of University Students on Microplastics in Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleksiuk, K.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Wypych-Ślusarska, A.; Głogowska-Ligus, J.; Spychała, A.; Słowiński, J. Microplastic in Food and Water: Current Knowledge and Awareness of Consumers. Nutrient 2022, 14, 4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, L.; Kubalewski, M.; Clark, R.; Statza, E.; Goyne, T.; Leach, K.; Peller, J. Detecting Microplastics in Soil and Sediment in an Undergraduate Environmental Chemistry Laboratory Experiment That Promotes Skill Building and Encourages Environmental Awareness. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribič, L.; Devetak, I.; Slapničar, M. Assessing 15-Year-Olds’ Understanding of Chemical Concepts in the Context of the Lithosphere and Pedosphere. Acta Chim. Slov. 2024, 71, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidi, S.; Renninger, K.A.; Krapp, A. Interest, A Motivational Variable That Combines Affective and Cognitive Functioning. In Motivation, Emotion, And Cognition: Integrative Perspectives on Intellectual Functioning and Development; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Krapp, A. Entwicklung Und Förderung von Interessen Im Unterricht. Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 1998, 45, 186–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rotgans, J.I.; Schmidt, H.G. The Relation between Individual Interest and Knowledge Acquisition. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 43, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, C.; Lentillon-Kaestner, V.; Pasco, D. Students’ Individual Interest in Physical Education: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire. Scand. J. Psychol. 2021, 62, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidi, S.; Ann Renninger, K. The Four-Phase Model of Interest Development. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 41, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukayoua, Z.; Kaddari, F.; Bennis, N. Students’ Interest in Science Learning and Measurement Practices. Questions for Research in the Moroccan School Context. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 119, 05006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadabi, A. Science Interest, Utility, Self-Efficacy, Identity, and Science Achievement Among High School Students: An Application of SEM Tree. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 634120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitto, A.; Juuti, K.; Lavonen, J.; Byman, R.; Meisalo, V. Secondary School Students’ Interests, Attitudes and Values Concerning School Science Related to Environmental Issues in Finland. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.E.; Schweingruber, H.; Stevenson, H.W. Gender differences in interest and knowledge acquisition: The United States, Taiwan and Japan. Sex Roles 2002, 47, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.M.; Johnson, K.E.; Kelley, K. Longitudinal analysis of the relations between opportunities to learn about science and the development of interests related to science. Sci. Educ. 2012, 96, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, E.; Veermans, M.; Gegenfurtner, A.; Veermans, K. Individual Interest and Learning in Secondary School Stem Education. Frontline Learn. Res. 2020, 8, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cast, A.D.; Burke, P.J. A Theory of Self-Esteem. Soc. Forces 2002, 80, 1041–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.; Schooler, C.; Schoenbach, C.; Rosenberg, F. Global Self-Esteem and Specific Self-Esteem: Different Concepts, Different Outcomes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995, 60, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.H.; Phillips, L.J. The Influence of Motivation and Adaptation on Students’ Subjective Well-Being, Meaning in Life and Academic Performance. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, F.; Almeida, L.S. Self-Concept, Self-Esteem and Academic Achievement: Strategies for Maintaining Self-Esteem in Students Experiencing Academic Failure. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2010, 25, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuffiano, A.; Alessandri, G.; Gerbino, M.; Luengo Kanacri, B.P.; Di Giunta, L.; Milioni, M.; Caprara, G.V. Academic Achievement: The Unique Contribution of Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Self-Regulated Learning beyond Intelligence, Personality Traits, and Self-Esteem. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2013, 23, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, H.; Abdullah, R.; Hamid, T.A.; Jamaluddin, S.; Aizan, H.T.; Sharir, J.; Kumar, V. Self Esteem, Gender and Academic Achievement of Undergraduate Students. Am. J. Sci. Res. 2009, 3, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulghani, A.H.; Almelhem, M.; Basmaih, G.; Alhumud, A.; Alotaibi, R.; Wali, A.; Abdulghani, H.M. Does Self-Esteem Lead to High Achievement of the Science College’s Students? A Study from the Six Health Science Colleges. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R.A.; Dorle, J.; Sandige, S. Self-esteem and school performance. Psychol. Sch. 1977, 14, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahranavard, M.; Hassan, S.A. The Relationship Betweenself-Concept, Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Anxietyand Science Performance among Iranian Students. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2012, 12, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriam Mamah, I.; Ezugwu, I.J.; Ezeudu, F.O.; Christian, S. Self-Esteem as a Predictor of Science Students’ Academic Achievement in Enugu State, Nigeria: Implication for Educational Foundations. Webology 2022, 19, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Dolenc-Orbanič, N.; Batteli, C. With appropriate approaches to transforming alternative concepts. Vodenje Vzgoji Izobr. 2011, 13, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, H. Misconceptions in physics amongst South African students. Phys. Educ. 1980, 15, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghini, A.; Pieraccioni, F.; Bastiani, L.; Bonaccorsi, E.; Gioncada, A. Geoscience Knowledge at the End of Upper-Secondary School in Italy. Rev. Sci. Math. ICT Educ. 2019, 16, 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fertika Putri, C.; Sutiarso, S.; Koestoro, B.; Fertika, C. Student Difficulties Based on Literacy Skills and Interpreting Social Problems or Mathematical Data Using Graphs. IOSR J. Math. 2018, 14, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, J.E. Students’ Alternative Conceptions in Earth Science: A Review of Research and Implications for Teaching and Learning. Res. Pap. Educ. 1998, 13, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, H.R.; Reynolds, C.J.; Lewis, A.; Muller-Karger, F.; Alsharif, K.; Mastenbrook, K. Examining Youth Perceptions and Social Contexts of Litter to Improve Marine Debris Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 1400–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, S.; Rudman, L. Reconfiguring the Everyday: Plastic Waste as Performance Art in Addressing the Incongruity between the ‘Talk’ and the ‘Walk’ in the Plastic Crisis. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1487–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juriševič, M.; Vogrinc, J.; Glažar, S.A. Targeted Research Project: Analysis of Factors Affecting More Permanent Knowledge Through Understanding of Natural Science and Technical Content; Faculty of Education: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, J.K. The study of student misunderstandings in the physical sciences. Res. Sci. Educ. 1977, 7, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltakci Gurel, D.; Eryilmaz, A.; McDermott, L.C. A Review and Comparison of Diagnostic Instruments to Identify Students’ Misconceptions in Science. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2015, 11, 989–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, R.; Indriyanti, D.R.; Mindyarto, B.H. Development of a Diagnostic Test for Student Misconception Detection of Coordination System Material Using Four-Tier Multiple Choice. J. Innov. Sci. Educ. 2021, 10, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Percentage of Correctly Solved Tasks | Level of Knowledge |

|---|---|

| 75–100% | Adequate knowledge |

| 74–50% | Roughly adequate knowledge |

| 49–25% | Inadequate knowledge |

| 24–0% | Completely inadequate knowledge |

| Number of Points | Level of Individual Interest/Self-Esteem |

|---|---|

| <M − SD | Low level of individual interest/self-esteem |

| <M ± SD> | Middle level of individual interest/self-esteem |

| >M + SD | High level of individual interest/self-esteem |

| <17.7 | Low level of individual interest (Gp1) |

| 17.7–34.3 | Middle level of individual interest (Gp2) |

| >34.3 | High level of individual interest (Gp3) |

| <7.6 | Low level of self-esteem (Gp1) |

| 7.6–14.4 | Middle level of self-esteem (Gp2) |

| >14.4 | High level of self-esteem (Gp3) |

| 1. Tier: Answer | 2. Tier: Confidence in the Answers * | 3. Tier: Reason | 4. Tier: Confidence in the Reason * | Level of Knowledge About Microplastics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | >3 | Correct | >3 | Adequate knowledge |

| Correct | >3 | Wrong | >3 | False positive knowledge |

| Wrong | >3 | Correct | >3 | False negative knowledge |

| Wrong | >3 | Wrong | >3 | Misconception |

| All other combinations | Lack of knowledge | |||

| Percentage (%) | Category |

|---|---|

| 0–30 | Low incidence of misconceptions about microplastics |

| 31–70 | Moderate incidence of misconceptions about microplastics |

| 71–100 | High incidence of misconceptions about microplastics |

| Number of the Task | Task Content | Knowledge (f, f%) | Lack of Knowledge (f, f%) | False Positive (f, f%) | False Negative (f, f%) | Misconceptions (f, f%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Consuming of microplastics | 8 2.9 | 203 72.7 | 2 0.7 | 22 7.9 | 16 5.8 |

| 2. | Microplastics removal from water | 42 15.1 | 222 79.5 | 3 1.1 | 3 1.1 | 9 3.2 |

| 3. | Drink water pollution with microplastics | 38 13.6 | 190 68.1 | 50 17.9 | 1 0.4 | 00 |

| 4. | Ocean pollution with microplastics | 18 6.5 | 217 77.7 | 2 0.7 | 13 4.7 | 29 10.4 |

| 5. | Life on land and microplastics | 17 6.1 | 212 76.0 | 2 0.7 | 4 1.4 | 44 15.8 |

| 6. | Formation of microplastics and its impact | 79 28.3 | 177 63.5 | 4 1.4 | 12 4.3 | 7 2.5 |

| 7. | River pollution with microplastics | 26 9.3 | 240 86.1 | 6 2.1 | 2 0.7 | 5 1.8 |

| 8. | Formation of microplastics | 9 3.2 | 236 84.6 | 3 1.1 | 4 1.4 | 27 9.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribič, L.; Devetak, I.; Hergan, I. Fourteen-Year-Old Students’ Understanding of Problems Related to Microplastics in the Environment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411139

Ribič L, Devetak I, Hergan I. Fourteen-Year-Old Students’ Understanding of Problems Related to Microplastics in the Environment. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411139

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibič, Luka, Iztok Devetak, and Irena Hergan. 2025. "Fourteen-Year-Old Students’ Understanding of Problems Related to Microplastics in the Environment" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411139

APA StyleRibič, L., Devetak, I., & Hergan, I. (2025). Fourteen-Year-Old Students’ Understanding of Problems Related to Microplastics in the Environment. Sustainability, 17(24), 11139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411139