Integrating Remote Sensing, GIS, and Citizen Science to Map Illegal Waste Dumping Susceptibility in Dakar, Senegal

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

1.2. Recent Findings

1.3. Gaps and Research Question

1.4. Research Objectives and Manuscript Workplan

2. Materials and Methods

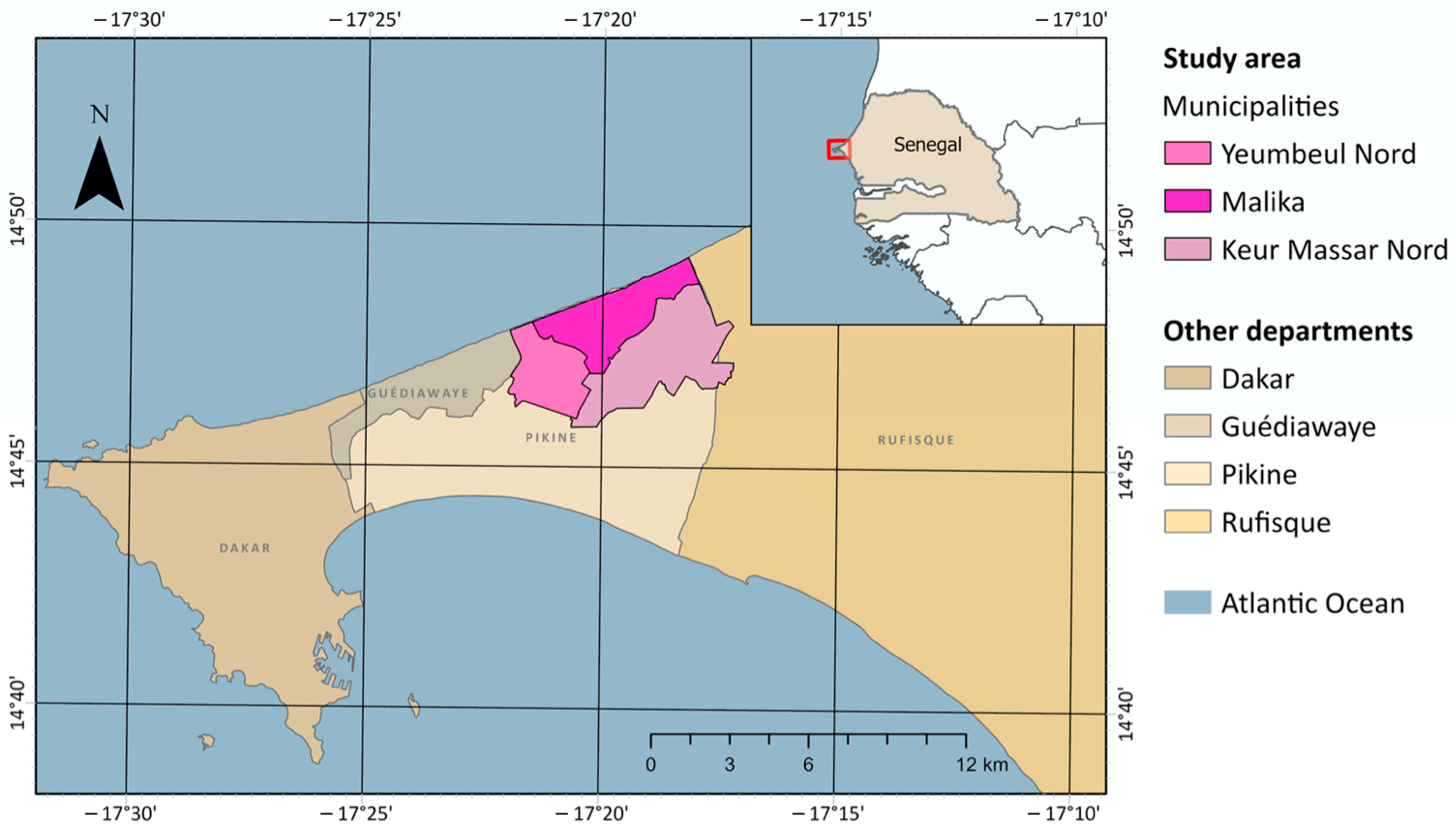

2.1. Study Area

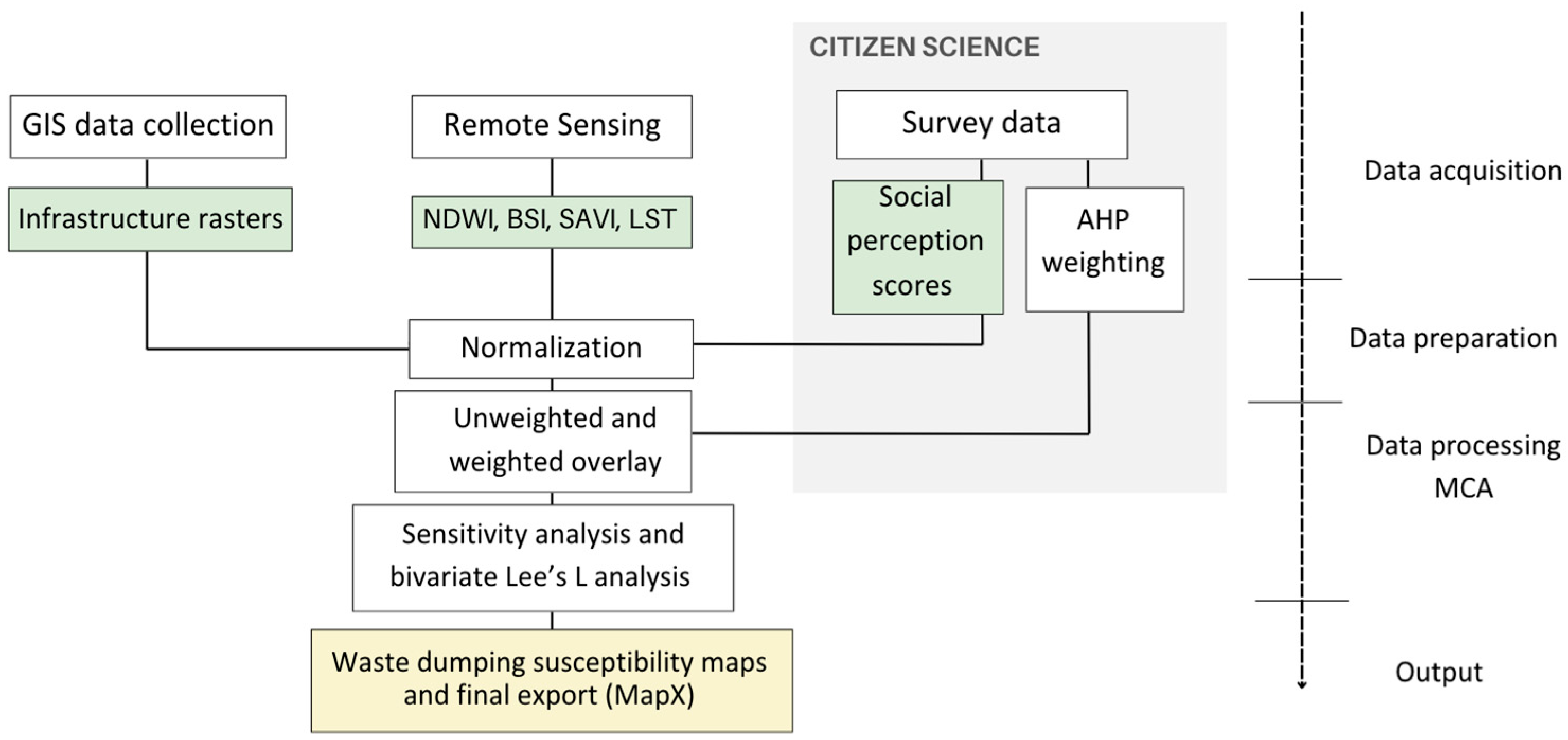

2.2. Analytical Framework

2.3. Criteria and Data Sources

2.4. Citizen Science Component

2.5. Weighting and Analytic Hierarchy Process

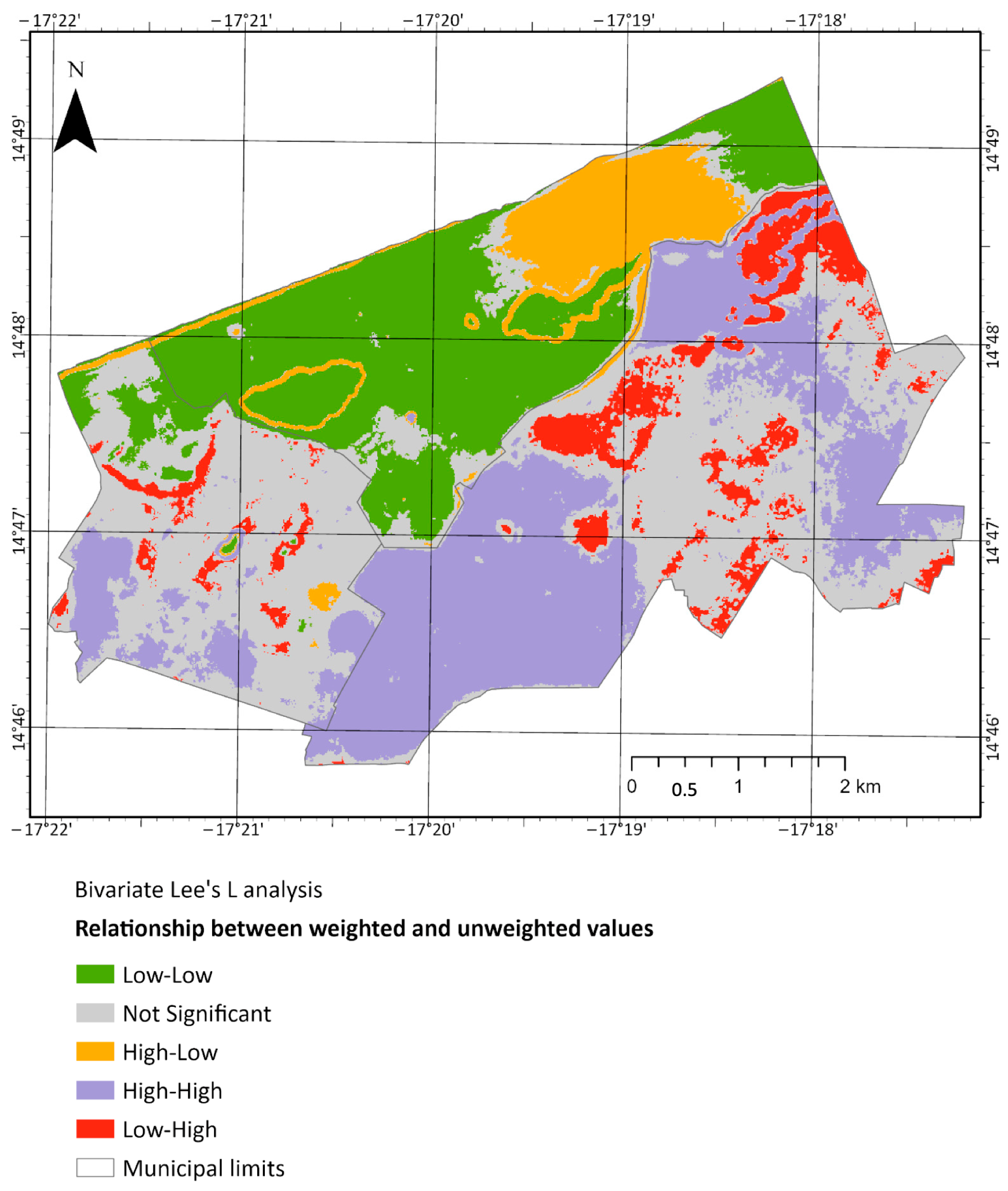

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

2.7. Dissemination on a Cartographic Application

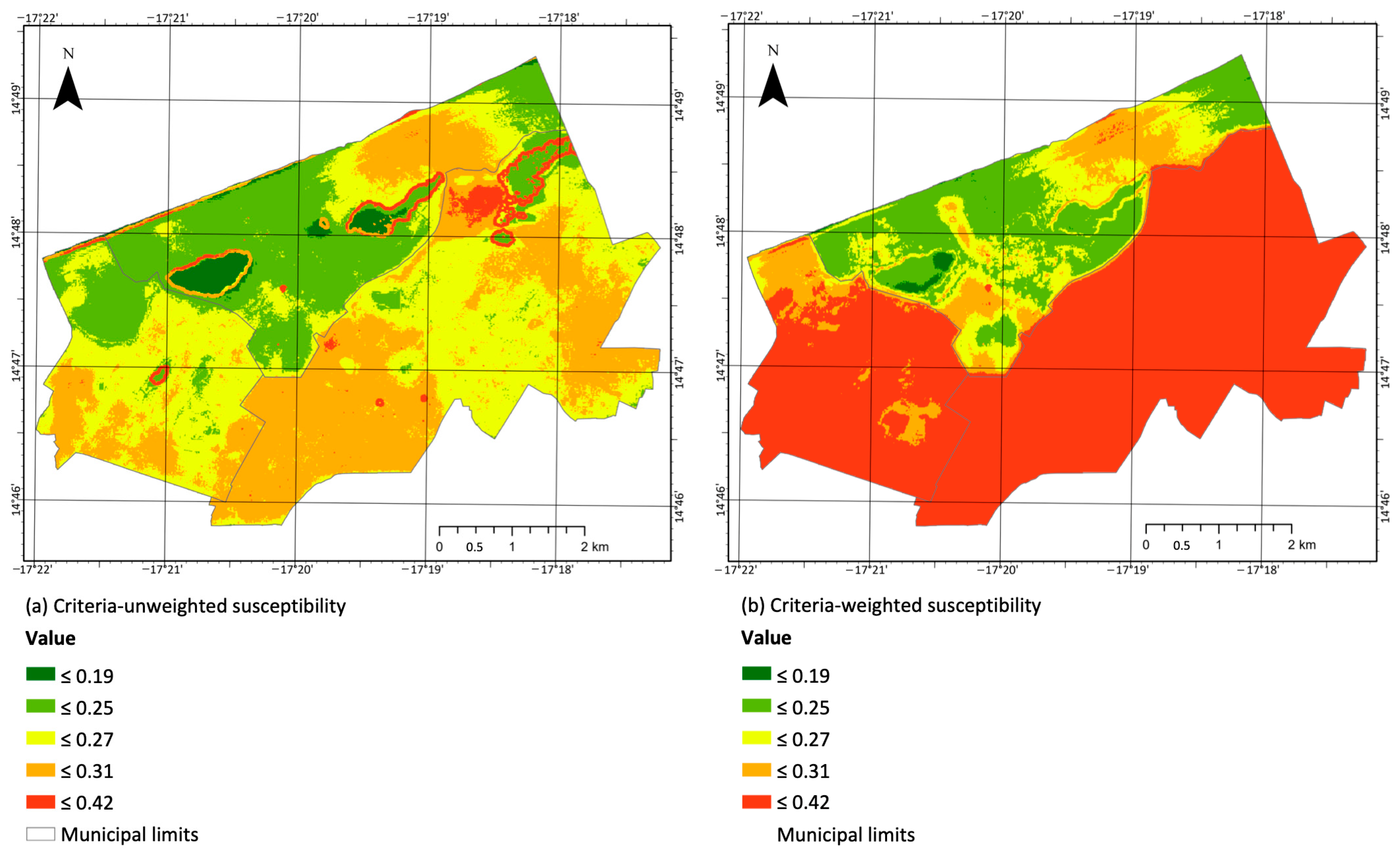

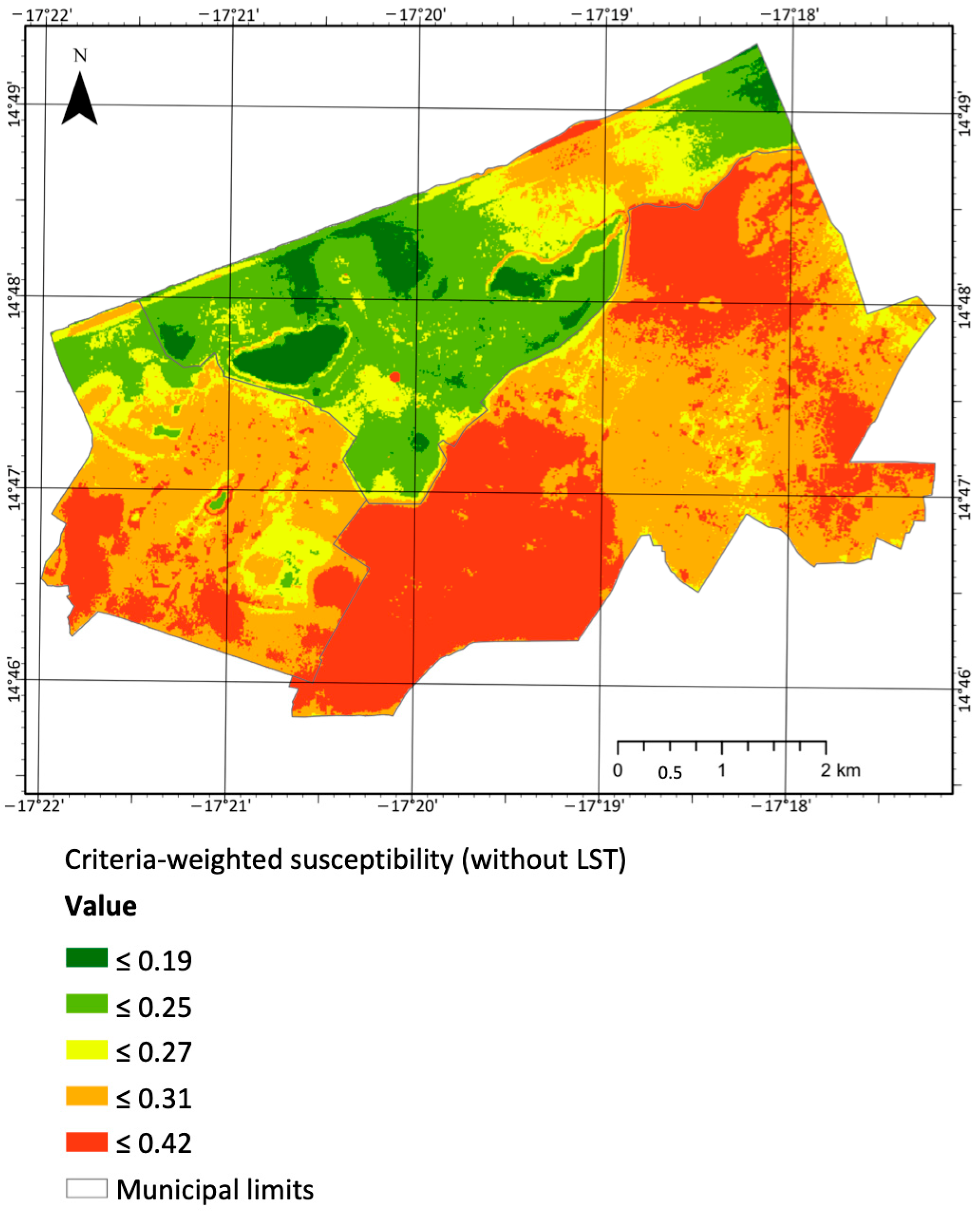

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Patterns of Illegal Dumping Susceptibility

4.2. Role of Social Perception and Participatory Weighting

4.3. Integration with MapX and Transparency Data

4.4. Transferability and Replicability of the Methodological Framework

4.5. Supporting Evidence from Comparative Studies

4.6. Integration of Remote Sensing, GIS and Citizen Science

4.7. Methodological Limitations

4.8. Unaddressed Systemic Drivers and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Debrah, J.K.; Teye, G.K.; Dinis, M.A.P. Barriers and Challenges to Waste Management Hindering the Circular Economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoezie, E.I.; Eludoyin, A.O.; Udeh, E.B.; Onanuga, M.Y.; Salami, O.O.; Adebayo, A.A. Climate, Urbanization and Environmental Pollution in West Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemajou, A.; Chenal, J.; Meylan, F.; Naji, S.; Felder, N. Villes Africaines et Technologies Numériques: Entre Risques et Potentiels; EPFL|Centre Excellence in Africa (EXAF): Dakar, Senegal, 2023; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, G. The Politics and Technologies of Urban Waste. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miraftab, F. Neoliberalism and Casualization of Public Sector Services: The Case of Waste Collection Services in Cape Town, South Africa. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 874–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, R. Disorderly Dakar: The Cultural Politics of Household Waste in Senegal’s Capital City. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2013, 51, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, R. Anthropocenic Discards: Embodied Infrastructures and Uncanny Exposures at Dakar’s Dump. Antipode 2021, 57, 1663–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JICA. Ministry of Urban Renewal, Housing and Living Environment. In Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035; Final Report Summary; Department of Urbanization and Architecture (DUA): Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IIED. Improving Solid Waste Management Practices and Addressing Associated Health Risks in Dakar, Senegal. In Urban Africa: Risk Knowledge; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ANSD. Rapport National Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat (RGPH-5, 2023); Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie: Dakar, Senegal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Tahir, M.; Ullah, F.; Rehman, M.; Albattah, M. Identifying and Ranking Landfill Sites for Municipal Solid Waste Management: An Integrated Remote Sensing and GIS Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, M.; Sarr, K.A.; Toure, M.N. Système d’Information Géographique (SIG) et Gestion des Déchets Ménagers dans la Commune de Malika (Région de Dakar, Sénégal). Rev. ACAREF 2024, 3, 349–380. [Google Scholar]

- Lavender, S. Detection of Waste Plastics in the Environment: Application of Copernicus Earth Observation Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vambol, S.; Vambol, V.; Sundararajan, M.; Ansari, I. The Nature and Detection of Unauthorized Waste Dump Sites Using Remote Sensing. Ecol. Quest. 2019, 30, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraternali, P.; Morandini, L.; Herrera González, S.L. Solid Waste Detection, Monitoring and Mapping in Remote Sensing Images: A Survey. Waste Manag. 2024, 189, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, N.; Al-Sharif, M.; Briezat, M.A. Mapping the Thermal Footprint of a Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Using Remote Sensing and Artificial Intelligence. Appl. Geomat. 2024, 16, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, B.; Frischknecht, C.; Dao, H.; Consuegra, D.; Giuliani, G. Flood Hazard Assessment and the Role of Citizen Science. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 12, e12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craglia, M.; Shanley, L. Data Democracy—Increased Supply of Geospatial Information and Expanded Participatory Processes in the Production of Data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2015, 8, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananta, M.T.; Rohidah, S.; Brata, K.C.; Abidin, Z. Mobile Crowdsourcing App Design: Managing Waste Through Waste Bank in Rural Area of Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Sustainable Information Engineering and Technology, Badung, Indonesia, 24–25 October 2023; pp. 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigo, G.; Zurbrügg, C.; Juwana, I.; Binder, C.R. Where Does Plastic Waste Go? Local Dynamics of Waste Flows in Indonesian Neighbourhoods. Environ. Chall. 2025, 19, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choplin, A.; Lozivit, M. Mapping a slum: Learning from participatory mapping and digital innovation in Cotonou (Benin): Questioning participatory approaches and the digital shift in southern cities. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.; Shonowo, A.; De Sherbinin, A.; Hultquist, C.; Danielsen, F.; Cooper, C.; Mondardini, M.; Faustman, E.; Browser, A.; Minster, J.-B.; et al. Mapping the Landscape of Citizen Science in Africa: Assessing Its Potential Contributions to Sustainable Development Goals 6 and 11 on Access to Clean Water and Sanitation and Sustainable Cities. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2023, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asingizwe, D.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Koenraadt, C.J.M.; Van Vliet, A.J.H.; Ingabire, C.M.; Mutesa, L.; Leeuwis, C. Why (Not) Participate in Citizen Science? Motivational Factors and Barriers to Participate in a Citizen Science Program for Malaria Control in Rwanda. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisma, J.A.; Schoups, G.; Davids, J.C.; Van De Giesen, N. A Bayesian Model for Quantifying Errors in Citizen Science Data: Application to Rainfall Observations from Nepal. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 3565–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosako, A.; Miyazaki, S.; Inoue, U.; Tasaki, T.; Osako, M.; Tamura, M. Detection of Illegal Dumping Sites by Using Vegetation Index and Land Surface Feature from High Resolution Satellite Images. J. Remote Sens. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 29, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.R.; Brust, A.V. Mapping Illegal Waste Dumping Sites with Neural-Network Classification of Satellite Imagery. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.08599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biotto, G.; Silvestri, S.; Gobbo, L.; Furlan, E.; Valenti, S.; Rosselli, R. GIS, Multi-criteria and Multi-factor Spatial Analysis for the Probability Assessment of the Existence of Illegal Landfills. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2009, 23, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, K.; Chang, H.-C. Mapping Illegal Domestic Waste Disposal Potential to Support Waste Management Efforts in Queensland, Australia. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 29, 1042–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Ng, K.T.W.; Richter, A. Development and Application of an Analytical Framework for Mapping Probable Illegal Dumping Sites Using Nighttime Light Imagery and Various Remote Sensing Indices. Waste Manag. 2022, 143, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. International Development Association Project Paper on a Proposed Additional to the Republic of Senegal for the Credit Stormwater Management and Climate Change Adaptation Project 2; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ndour, M.M.M.; Ndao, M.L.; Ndonky, A. Urban Dynamics and Emergence of New Centers in the Dakar Region (Senegal). J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2024, 16, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faty, A.; Diop, C.; Faye, W. Rainwater and Wastewater Management: A Case Study of Dakar’s Built-up Area, Senegal. Preprints 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissé, O.; Sèye, M. Flooding in the Suburbs of Dakar: Impacts on the Assets and Adaptation Strategies of Households or Communities. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Implementation Completion and Results Report to the Republic of Senegal for the Stormwater Management and Climate Change Adaptation Project; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Breaking Cycles of Risk Accumulation in African Cities. In United Nations Human Settlements Programme; UN-Habitat, in collaboration with Urban Africa Risk Knowledge: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sy, B.; Mbow, M.; Aw, S. Cartographie de La Susceptibilité d’inondation En Utilisant l’analyse Multicritère Basée Sur La Procédure d’analyse Hiérarchique Dans Les Départements de Pikine et de Keur Massar, Sénégal. In VertigO—la Revue Électronique en Sciences de L’environnement; VertigO: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Diémé, L.P.M.; Bouvier, C.; Bodian, A.; Sidibé, A. Modelling Urban Stormwater Drainage Overflows for Assessing Flood Hazards: Application to the Urban Area of Dakar (Senegal). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Sector Brief Senegal: Solid Waste Management and Recycling; GIZ: Bonn, Germany., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. International Development Association Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Credit to the Republic of Senegal for a Senegal Municipal Solid Waste Management Project; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- IIED. Practices and Perceptions around Solid Waste Management in Dakar. In Urban Africa: Risk Knowledge; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- APHRC. Solid Waste Management and Risks to Health in Urban Africa; African Population and Health Research Center: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- PROMOGED. “You Only See Garbage. We See a Treasure”, or Why Waste Management in Senegal Is a Key Issue for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.promoged.sn/en/fr/node/124?utm (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Walker, S. Dakar Has Lost Its Lungs: What the Spatialised Inequalities of Waste Can Tell Us about Climate (Im)Mobilities. Environ. Plan. C Polit. Space 2024, 42, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abizaid, O.; Diop, M.; Soumaré, A.; Wilson, E.; Institute of Development Studies. Waste Pickers Are Part of the Solution to Solid Waste Management in Senegal; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jordá-Borrell, R.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, F.; Lucendo-Monedero, Á.L. Factor Analysis and Geographic Information System for Determining Probability Areas of Presence of Illegal Landfills. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 37, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrat, A. Les lieux de l’ordure de Dakar et d’Addis Abeba. In Territoires Urbains et Valorisation Non Institutionnelle des Déchets Dans Deux Capitales Africaines; Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, J.; Faisal, K.; Shaker, A.; Yan, W.Y. Detection of Waste Dumping Locations in Landfill Using Multi-Temporal Landsat Thermal Images. Waste Manag. 2019, 37, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobrino, J.A.; Jiménez-Muñoz, J.C.; Paolini, L. Land Surface Temperature Retrieval from LANDSAT TM 5. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S.K. The Use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the Delineation of Open Water Features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikimaru, A.; Roy, P.S.; Miyatake, S. Tropical Forest Cover Density Mapping. Trop. Ecol. 2002, 43, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, N.; Ng, K.T.W. Mapping and Prioritizing Potential Illegal Dump Sites Using Geographic Information System Network Analysis and Multiple Remote Sensing Indices. Earth 2022, 3, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, C.; Karanja, E.; Omojah, S.; Chishala, C.; Oniosun, T.I. Wastesites.io: Mapping Solid Waste to Meet Sustainable Development Goals. In Open Mapping towards Sustainable Development Goals: Voices of YouthMappers on Community Engaged Scholarship; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, T.; Defe, R.; Mavugara, R.; Mupepi, O.; Shabani, T. Application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Remote Sensing (RS) in Solid Waste Management in Southern Africa: A Review. SN Soc. Sci. 2024, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carioli, A.; Schiavina, M.; Melchiorri, M.; Kemper, T. GHSL Country Statistics by Degree of Urbanization: Public Release of GHS COUNTRY STATS R2024A; European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L.; Wind, Y. Marketing Applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Manag. Sci. 1980, 26, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, W. An Integrated Framework Comprising of AHP, Expert Questionnaire Survey and Sensitivity Analysis for Risk Assessment in Mining Projects. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2019, 14, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.A.; Munir, A.; Imran, S.; Nasir, M.K.; Muhayyuddin, M.G.; Javed, A.; Mehmood, A.; Habila, M.A.; Fayaz, H.; Qazi, A. Evaluating Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management Scenarios: A Multicriteria Decision Making Approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.E.; Harrison, S.R.; Wegener, M.K. Validation of Multicriteria Analysis Models. Agric. Syst. 1999, 62, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-I. Developing a Bivariate Spatial Association Measure: An Integration of Pearson’s r and Moran’s I. J. Geogr. Syst. 2001, 3, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, P.; Moser, F.; Benvenuti, A.; Piller, T.; Jensen, D.; Petersen, I.; Planque, M.; Ray, N. MapX: An Open Geospatial Platform to Manage, Analyze and Visualize Data on Natural Resources and the Environment. SoftwareX 2019, 9, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/GRID-Geneva. Global Resource Information Database (GRID) Geneva. Available online: https://www.unepgrid.ch (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Tsheleza, V.; Nakin, M.D.V.; Ndhleve, S.; Kabiti, H.M.; Musampa, C.M. Vulnerability of Growing Cities to Solid Waste-Related Environmental Hazards: The Case of Mthatha, South Africa. Jamba J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2019, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntlangula, L.; Xelelo, Z.; Chitongo, L. Evaluating Enforcement Strategies for Curbing Illegal Waste Dumping: A Case Study of King Sabata Dalindyebo Local Municipality, South Africa. IRASD J. Manag. 2025, 7, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakeni, Y.; Maphanga, T.; Madonsela, B.S.; Malakane, K.C. Identification of Illegal Dumping and Community Views in Informal Settlements, Cape Town: South Africa. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, B. Approche Multidisciplinaire de l’Évaluation de l’Aléa D’inondation à Yeumbeul Nord, Dakar, Sénégal: La Contribution de la Science Citoyenne; Université de Genève: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Antofie, T.; Doherty, B.; Marin Ferrer, M. Mapping of Risk Web-Platforms and Risk Data: Collection of Good Practices; Publications Office of the European Eunion: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-80171-6. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler, P.; Larsen, T.A.; Maurer, M.; Staufer, P.; Lienert, J. A Participatory Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework Reveals Transition Potential towards Non-Grid Wastewater Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 121962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, M.; Arrighi, C.; Piragino, F.; Castelli, F. Participatory Multi-Criteria Decision Making for Optimal Siting of Multipurpose Artificial Reservoirs. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferla, G.; Mura, B.; Falasco, S.; Caputo, P.; Matarazzo, A. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) for Sustainability Assessment in Food Sector. A Systematic Literature Review on Methods, Indicators and Tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, H.-M.; Cohen, B.; Harrison, S.T.L.; Broadhurst, J.L. Validity of Using Expert Judgements to Inform Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: Selecting Technologies for Sulfide-Enriched Fine Coal Waste Reuse. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Source | Format | Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population density | GHS-POP R2023A Global Human Settlement Layer | GeoTIFF, 100 m raster | 2025 |

| Satellite imagery | Copernicus Browser, Sentinel-2 Level-1C | JP2 file, 10–20 m raster | April 2025 |

| Land surface temperature (LST) | Landsat product Planetary Computer, Landsat 8 | GeoTIFF, 100 m raster | January 2025–June 2025 |

| Collection and sweeping routes | SONAGED | Vector layer, polyline | 2025 |

| Waste collection points | SONAGED | Vector layer, points | 2025 |

| Markets of Keur Massar, Malika and Yeumbeul Nord | Dakar municipal authorities | Vector layer, points | N/A |

| Highways | GéoSénégal, “Dakar, Voirie” | Vector layer, polyline | 2019 |

| Social perception | Citizen responses to waste-related survey | Google Forms Survey, CSV | July 2025 |

| Municipality | Aggregated Scores |

|---|---|

| Yeumbeul Nord | 0.59 |

| Malika | 0.33 |

| Keur Massar | 0.79 |

| Criteria | Derived Weights |

|---|---|

| Social perception | 0.29 |

| Population density | 0.21 |

| Vegetation index | 0.15 |

| Collection circuits | 0.11 |

| Markets | 0.08 |

| Waste collection points | 0.06 |

| Bare soil | 0.04 |

| Water index | 0.03 |

| Highways | 0.02 |

| LST | 0.02 |

| Criteria | Derived Weights |

|---|---|

| Social perception | 0.20 |

| Population density | 0.18 |

| Vegetation index | 0.16 |

| Collection circuits | 0.13 |

| Markets | 0.11 |

| Waste collection points | 0.09 |

| Bare soil | 0.07 |

| Water index | 0.04 |

| Highways | 0.02 |

| Study/Model | Model Type | % Population/Areas of Highest Vulnerability | Interpretation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted criteria | Unweighted | Keur Massar: 98.5%, Yeumbeul Nord: 94.2%, Malika: 35.7% | Very high susceptibility in densely populated/poorly serviced zones | This study |

| Weighted criteria (with LST) | Weighted | Keur Massar: 99.88%, Yeumbeul Nord: 97.67%, Malika: 28.4% | LST (Land Surface Temperature) increases weights in hot/urbanized zones | This study |

| Weighted criteria (without LST) | Weighted | Keur Massar: 98.7%, Yeumbeul Nord: 95.3%, Malika: 31.5% | Variant to test effect of excluding LST | This study |

| Mthatha, South Africa | Unweighted (socio-economic vulnerability) | High vulnerability in informal/dense settlements (~not exactly “very high %” map, but strong risk) | Low-density informal and high-density formal settlements face higher waste and environmental risk | [63] |

| King Sabata Dalindyebo municipality, South Africa | Weighted-like (spatial + socio-economic analysis) | The study finds illegal dumping is over-represented in low-income/informal areas (no exact % “very high” susceptibility map) | Combines GIS, survey, and enforcement analysis but lacks a classic LST-based susceptibility map. | [64] |

| Cape Town, South Africa (informal settlements) | Weighted (spatial + community-based) | ~52 dumpsites identified within high-risk buffer zones near populated areas (43.18% of residents lacked proper refuse containers) | Uses GIS and community surveys to map vulnerability to illegal dumping | [65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scharf, N.; Ducry, B.; Sy, B.; Djim, A.; Lacroix, P. Integrating Remote Sensing, GIS, and Citizen Science to Map Illegal Waste Dumping Susceptibility in Dakar, Senegal. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11137. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411137

Scharf N, Ducry B, Sy B, Djim A, Lacroix P. Integrating Remote Sensing, GIS, and Citizen Science to Map Illegal Waste Dumping Susceptibility in Dakar, Senegal. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11137. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411137

Chicago/Turabian StyleScharf, Norma, Bénédicte Ducry, Bocar Sy, Abdoulaye Djim, and Pierre Lacroix. 2025. "Integrating Remote Sensing, GIS, and Citizen Science to Map Illegal Waste Dumping Susceptibility in Dakar, Senegal" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11137. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411137

APA StyleScharf, N., Ducry, B., Sy, B., Djim, A., & Lacroix, P. (2025). Integrating Remote Sensing, GIS, and Citizen Science to Map Illegal Waste Dumping Susceptibility in Dakar, Senegal. Sustainability, 17(24), 11137. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411137

_Li.png)