Abstract

Understanding the spatial dynamics of China’s marine economic geography is essential for sustainable coastal development and marine spatial governance. This study examines the spatial distribution patterns and influencing factors of spatial differentiation in China’s marine economy from 2013 to 2023, utilizing AI techniques to facilitate multi-source data fusion and employing a Random Forest analytical method. The research was integrated with AI-based web-scraping, automated data-cleaning procedures, multi-source data preprocessing, Min–Max normalization, and Random Forest regression to accomplish multi-source data fusion and factor-importance analysis. Kernel density estimation, global Moran’s I, Getis-Ord Gi* statistics, and buffer zone analysis were employed to characterize spatial heterogeneity across coastal, island, and maritime economic zones, while Spearman’s correlation was used to quantify the relationships of influencing factors. Results indicate that China’s marine economy exhibits a pronounced “south–hot–north–cold and east–strong–west–weak” spatial gradient, with high-value clusters concentrated in the Bohai Rim, Yangtze River Delta, and Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. The coastal zone economy accounts for over 65% of the national marine GDP and acts as the dominant driver of spatial agglomeration. Policy implications suggest strengthening cross-regional industrial cooperation and optimizing spatial planning to enhance marine economic resilience and sustainability.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid advancement of science and technology has accelerated the exploration and utilization of marine resources and promoted the development of the marine economy, which has increasingly become a global consensus and strategic priority. During the 18th and 20th National Congresses of the Communist Party of China, President Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of advancing China’s marine economy and proposed the strategy of building a maritime power, repeatedly highlighting issues related to marine resource development, industrial transformation, and international cooperation. During the 13th to 14th Five-Year Plan periods, China’s marine economic system has made remarkable progress. However, under the ongoing digital technology revolution, the transformation of the marine economy now faces new opportunities and emerging challenges. Against this backdrop, examining the spatial geography of the marine economy has become increasingly significant. Owing to the complexity and diversity of its spatial distribution and influencing factors, traditional approaches in economic geography are no longer sufficient to reveal its underlying mechanisms. The rapid development of AI and the expanding application of multi-source data fusion provide new analytical perspectives and methodological tools for identifying the spatial characteristics of marine economic geography. Therefore, integrating AI with multi-source data fusion to analyze spatial distribution patterns and influencing mechanisms is crucial for understanding spatial evolution, optimizing spatial configurations, promoting land–sea coordination, and fostering sustainable development in coastal regions.

As an essential technological innovation, AI has become a major driving force shaping the new wave of technological revolution and improving production efficiency [1,2,3]. In the 2024 Report on the Work of the Government, the State Council reiterated the importance of advancing research and application in AI and big data and launched the “AI Plus” initiative to accelerate intelligent development across industries. AI technology contributes significantly to cost reduction, not only by automating repetitive and procedural tasks but also by enhancing analytical capability through visual and intelligent applications [4,5]. Logg [6] noted that in highly repetitive and automation-prone professional domains, individuals tend to rely on AI for decision-making. Liu H [7] further argued that when AI satisfies users’ needs along specific dimensions, it fosters trust and promotes more effective human–machine interaction. Moreover, AI plays a vital role in mitigating information asymmetry and enabling users to access key data and information more efficiently [8,9]. Multi-source data fusion refers to the integration of diverse and complementary data features [10]. Compared with single-source data, it provides richer and more comprehensive characteristics, enabling deeper analysis of complex phenomena. It has been widely applied in information extraction, geographic information classification, spatial recognition, and feature identification [11,12,13], thereby supporting a more accurate representation of real-world spatial patterns. In the era of big data and AI, the synergistic integration of these two technologies provides an enhanced framework for addressing complex analytical tasks and improving the performance of spatial modeling.

Although traditional multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) models have been widely applied in sustainability assessment and comprehensive evaluation, they show evident limitations in handling heterogeneous data, spatial autocorrelation, and dynamic evolution mechanisms. The existing studies on MCDM still rely heavily on expert-based weighting and linear aggregation, resulting in high subjectivity in model evaluation and limited adaptability to the nonlinear relationships and spatial dependencies inherent in economic geography [14,15]. Furthermore, indicators constructed within MCDM frameworks are often treated as independent, neglecting the coupling effects and scale heterogeneity of multidimensional spatial data, which restricts their explanatory capacity and applicability to dynamic spatial-economic problems [16,17]. Against this backdrop, this study proposes a customized AI-driven spatial analysis approach that integrates AI algorithms with multi-source heterogeneous data fusion. The approach uses machine-learning-based procedures to extract indicators from multiple data sources and applies standardized transformation to variables of different formats and units, thereby ensuring data consistency. Subsequently, ArcGIS 10.8 serves as the core analytical platform for spatial visualization and clustering analysis. Compared with traditional MCDM tools, this AI-integrated framework demonstrates greater flexibility and improved analytical performance in addressing spatial–economic problems by enhancing alignment between natural and economic datasets and strengthening the precision and interpretability of spatial heterogeneity and regional differentiation in marine economic geography.

According to comprehensive data from the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the World Bank, and multiple academic studies, approximately 60% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) is generated within 100 km of coastlines. The core of marine economic geography lies in examining the interaction between human economic activities and the marine geographic environment [18]. To systematically illustrate the evolutionary trajectory of China’s marine economic research, this study constructs a chronological framework of China’s marine economic development (see Table 1) based on historical literature and key policy milestones. The timeline outlines the progression from the pre-Qin era to contemporary China, highlighting the institutional evolution and strategic formation of marine economic thought. It reveals China’s historical transition from resource utilization to institutional innovation, and from passive defense to proactive ocean development, demonstrating the continuous strengthening and modernization of the national marine governance system and strategic awareness. Overall, the spatial development of China’s marine economy holds significant practical implications for supporting China’s goal of becoming a maritime power.

Table 1.

Chronological Timeline of China’s Marine Economic Development.

To this end, this study investigates the spatial distribution characteristics of China’s marine economic geography from both spatial and quantitative perspectives. AI techniques are employed to collect and process heterogeneous data from multiple sources, ensuring consistency in scale and format. Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis is utilized to explore spatial distribution patterns and heterogeneity within the marine economy, while machine learning–based quantitative modeling is applied to identify and interpret the driving mechanisms of key influencing factors. Through the integration of AI-driven data processing, spatial analytics, and quantitative modeling, this research provides a methodological framework and theoretical reference for advancing spatial analytical approaches in marine economic geography. Specifically, the study applies AI-based web-scraping techniques, automated data-format unification and preprocessing, Min–Max normalization, and Random Forest (RF) machine learning algorithm to accomplish multi-source data fusion and quantify the relative importance of influencing factors.

2. Study Area and Data Sources

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

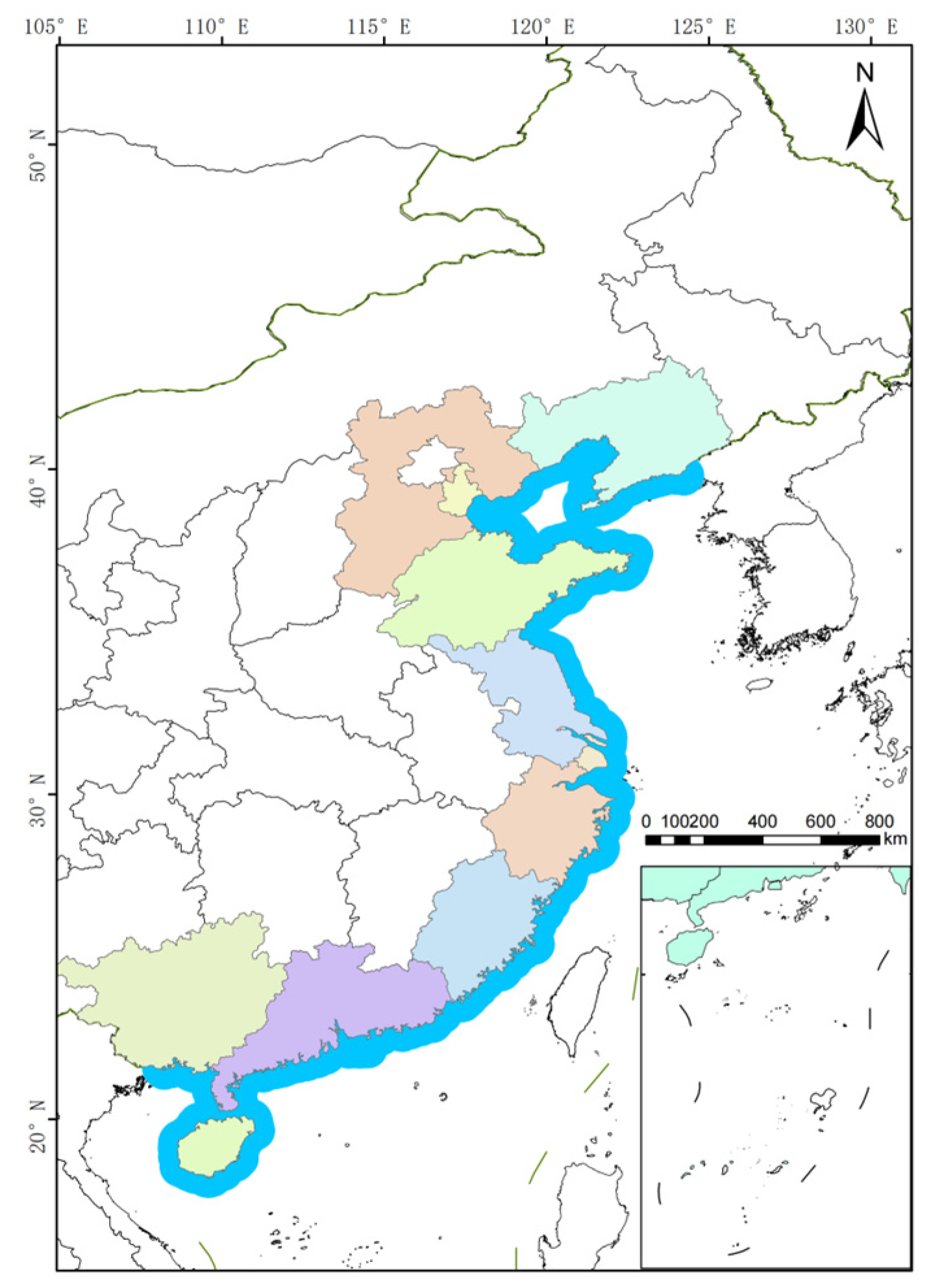

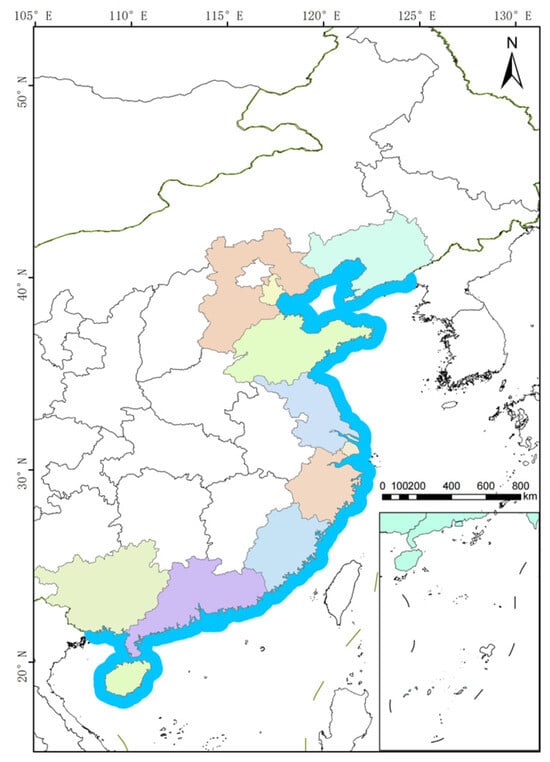

The study area encompasses China’s coastal zones, islands, and adjacent maritime regions, covering eleven coastal provinces and municipalities along the national marine economic belt (see Figure 1). The spatial scope of each province was defined according to its corresponding marine geographic extent. The research area includes five major subregions: the Bohai Rim, the Yangtze River Delta, the Southeast Coastal Zone, the Pearl River Delta, and the North Gulf region. Together, these areas represent the core spatial units of China’s coastal economy and serve as key zones for observing the spatial evolution and regional differentiation of marine economic activities. In total, the geographical scope of this study covers 11 coastal provinces and municipalities in China, namely Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shandong, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan. The temporal span extends from 2013 to 2023, forming an 11-year panel dataset comprising 121 sample observations and 36 indicator variables. This dual-dimensional panel structure captures both spatial and temporal dynamics of China’s coastal marine economy. The dataset was constructed through AI-assisted web scraping and data cleaning, integrating information from multiple sources to ensure temporal continuity and spatial consistency. As a result, the dataset effectively reflects the spatial distribution characteristics of marine economic activities across China’s coastal provinces.

Figure 1.

Study area of marine economic geography in China.

2.2. Data Sources

The data utilized in this study encompass three dimensions of China’s marine economy: the coastal zone economy, island economy, and marine area economy. The data sources include statistical yearbooks, spatial information databases, and web-based data collected through AI-assisted data acquisition. After unifying the measurement scales and spatial references, a standardized indicator system was established. Among these, macroeconomic indicators are derived from secondary data, spatial-geometric and environmental indicators originate from primary observational data, and web information indicators are obtained through AI-based data acquisition and formatting.

Secondary statistical data: Indicators related to social environment, disaster loss, and economic value were collected from official marine economic statistics, including the National Bureau of Statistics of China, provincial statistical bureaus, the China Marine Economy Statistical Yearbook, and the UN Ocean Economy Database. These datasets describe the macroeconomic attributes of marine economic activities.

Primary observational data: Indicators related to water resources, natural environment, land–sea resources, and ecological resources were derived from spatial databases such as the Geographic Information System (GIS) platform, the National Geomatics Center of China (NGCC), and the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS). These datasets were extracted as vector data, cleaned using AI algorithms, and spatially matched with the economic statistics to construct the panel dataset. They reflect the environmental and spatial attributes of marine geography.

Fused and derived data: Indicators such as land resources, tourism resources, and marine resource utilization were obtained from multiple web-based sources, including marine information networks, scientific research databases, and policy documents. These data were automatically collected and standardized through AI-based web scraping and data fusion procedures, forming supplementary variables for the marine economic panel dataset.

Under the unified AI-assisted framework for data crawling and formatting, the three categories of data were integrated into an Excel-based panel dataset with consistent spatial scales and temporal continuity (2013–2023). A range normalization method was applied to ensure comparability and spatial alignment among variables, thereby establishing a robust data foundation for subsequent GIS-based spatial analysis and modeling.

3. Evaluation Index System and Research Methods

3.1. Establishment of the Evaluation Index System

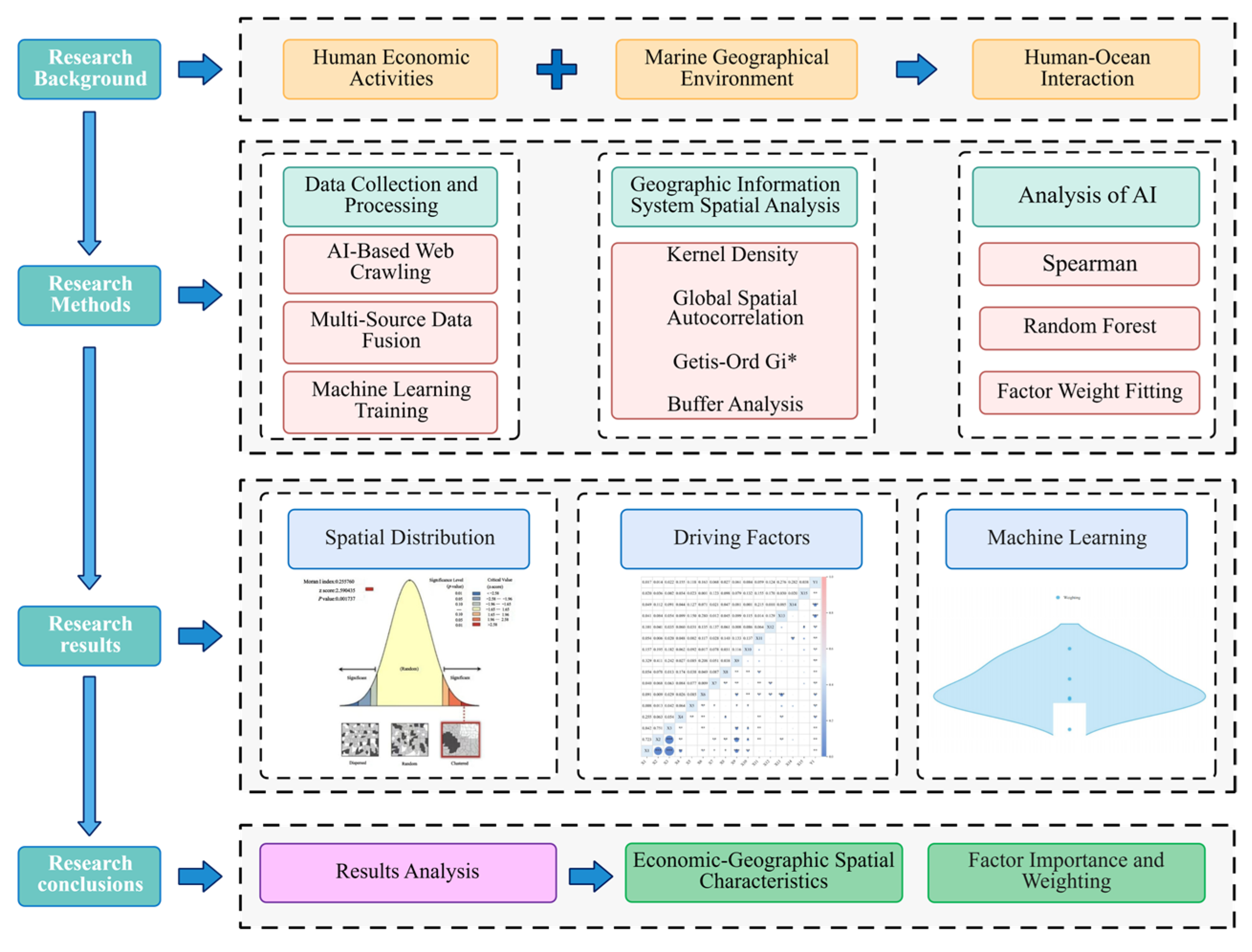

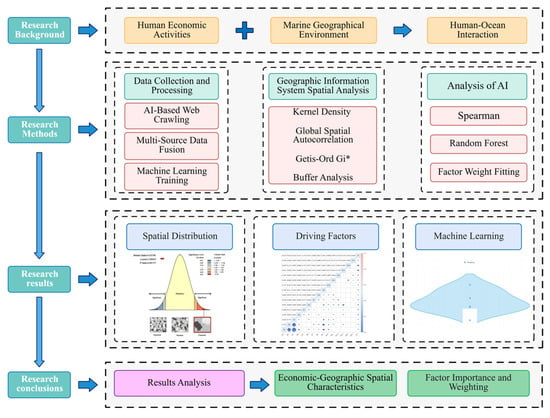

The evaluation index system in this study draws upon the Evaluation Index System for Dynamic Coasts (T/CSES 173–2024) [21] and relevant academic research. Three primary dimensions were selected as the first-level indicators for analyzing the spatial characteristics of China’s marine economic geography, including coastal zone economy, island economy, and maritime economy (see Table 2). The analysis was conducted from a provincial perspective using data covering the marine geographic scope of China’s coastal provinces and municipalities from 2013 to 2023. The detailed technical roadmap is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation Index System for Marine Economic Geography.

Figure 2.

Research Technical Roadmap.

3.1.1. Coastal Zone Economy

The coastal zone economy represents the composite economic system linking marine and terrestrial spaces. With the deepening of globalization and the evolving geopolitical landscape, the coastal zone economy has become a vital component of national development strategies, characterizing by intensive marine economic activities. Existing studies by domestic and international scholars on the spatial distribution of socioeconomic elements in coastal zones often focus on specific nations, cities, islands, or bays. International research has emphasized the impacts of global climate change, sea-level rise, and transnational cooperation on coastal economic development. For instance, Bergh investigated changes in economic and social elements within Finland’s coastal regions [22]; Raid analyzed the economic spatial patterns of bays within Caribbean islands from a micro-scale perspective [23]; Ache focused on coastal population aggregation in U.S. counties [24]; and Boschma discussed how the resilience of coastal economies enables adaptation to economic fluctuations and political uncertainties under globalization [25]. In China, research has primarily concentrated on industrial structure adjustment, economic efficiency, and resilience within coastal areas. Di Qianbin demonstrated that structural transformation in marine industries significantly promotes marine economic growth [26]; Zhao Lin evaluated China’s marine economic efficiency using the SBM and Malmquist productivity index models [27]; Hao Jinlian argued that the integration of terrestrial and marine resources is essential for the sustainable development of coastal urban economies [28]; and Chen Jun et al. proposed leveraging coastal economic spillover effects to stimulate the development of less-advanced regions [29]. Under the context of deepening globalization, a broader analytical perspective is needed to understand the spatiotemporal evolution of socioeconomic factors in global coastal zones.

3.1.2. Island Economy

The island economy constitutes a crucial component of the marine economy, and the progress of marine economic development and maritime power construction largely depends on the advancement of island economies. With the launch of China’s Comprehensive Survey on Island Resources, scholarly attention to islands has markedly increased. Zhang Yaoguang suggested that the industrial structure of island economies exhibits hierarchical characteristics and evolves dynamically over the long term [30]. Zhang Guanghai and Liu Zhenzhen found that industries in island counties have transitioned toward a polycentric structure with a distinct “club convergence” phenomenon [31]. Lin Fazhao emphasized the importance of utilizing island advantages to promote circular economies [32], while Ma Jingwu highlighted that diverse models and pathways should be adopted according to local conditions [33]. Yang Zhengxian proposed enhancing transportation infrastructure and ecological restoration to foster island ecological economies [34]; Yang Wenfeng identified circular economy development as a key pathway for green island growth [35]. International research also underscores similar trends. Thomas tested and demonstrated circular economy practices in island construction and demolition waste management, exploring the creation of closed-loop production and consumption systems [36]. Fiona and colleagues examined island plastic waste management policies and discussed the potential of circular economy development for enhancing territorial sustainability [37]. Globally, studies on island circular economies encompass both coordinated national or regional strategies and the development of individual island economies.

3.1.3. Maritime Economy

The maritime economy refers to economic activities directly related to the ocean and their influence on regional and national economic development, encompassing marine resource exploitation, marine environmental protection, and maritime transport. In 2012, the Report to the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China proposed the Maritime Power Strategy and introduced the National Marine Economy Development Plan, marking a new stage in the rapid expansion of marine economic activities across multiple sectors. Current research on the maritime economy primarily focuses on marine resource utilization, marine environmental conservation, and regional marine economic development. Yan Hongmo classified marine resources into biological, mineral, chemical, and dynamic categories [38]. Yao Chunyu found a significant positive relationship between marine resource endowment and marine economic growth [39]. Bennett emphasized that the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) not only safeguards valuable ocean resources but also promotes local economic development [40]. Li Bo, using a spatial Durbin model to analyze Liaoning Province, confirmed the presence of spatial spillover effects in the quality of marine economic growth across regions [41].

3.2. Research Methods

In recent years, decision-support frameworks jointly driven by hybrid models and AI have rapidly emerged in the field of marine sustainability assessment. In the context of multi-source heterogeneous data, Blasch [42] highlighted the limitations of traditional rule-based data fusion models in terms of robustness and generalization, emphasizing that learning-oriented adaptive fusion methods improve information extraction and inference stability by leveraging feature learning and uncertainty modeling. Meanwhile, Chen [43] integrated real-time observation, process-based simulation, and deep learning into a marine digital-twin architecture, forming a closed-loop system linking data acquisition, predictive cognition, and decision feedback, which marks the transition of marine information systems from simple digital representation to a more dynamic “twin replication” stage. At the methodological level, Song [44] summarized the main pathways for applying AI technologies in marine science and argued that the incorporation of AI substantially improves the dynamic interpretation and spatial explainability of complex geographic systems. From the perspective of computational engineering and system implementation, Senthilkumar [45] discussed issues of security and reliability under high-concurrency and multi-source data environments, noting that AI- and machine-learning-driven architectures provide scalable foundations for complex decision systems. Furthermore, Baghizadeh [46] developed a multi-objective intelligent optimization model using AIS data to improve vessel routing and energy efficiency in offshore wind maintenance, demonstrating the practical value of AI-driven spatiotemporal data fusion for quantitative decision-making in marine engineering management.

From a methodological implementation perspective, this study follows a workflow that integrates AI-assisted multi-source data acquisition and formatting, GIS spatial analysis, and machine-learning-based modeling. Unlike traditional multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods such as TOPSIS, AHP, or RER, the present research does not rely on direct subjective weighting or composite evaluation. Instead, automated web scraping, data cleaning, and format standardization are applied to ensure that heterogeneous data sources become comparable and consistent before spatial modeling. This methodological choice is motivated by the constraints of conventional MCDM frameworks, which often struggle to handle the multi-dimensionality, spatial heterogeneity, and coupling effects inherent in economic yearbook data, text-based information, raster datasets, and environmental variables. In contrast, AI techniques operate through automated data acquisition and self-learning mechanisms, which assists in reducing subjective weighting bias and enhances both data completeness and feature recognition at the preprocessing stage.

Accordingly, this study adopts a hybrid analytical framework that combines AI-supported data fusion with econometric and GIS-based spatial analysis. Specifically, AI methods were applied to acquire and unify the marine economic statistical data, natural environmental data, and multi-source web-based information required by the indicator system, producing a standardized panel dataset. Following range normalization to eliminate dimensional disparities, the dataset was used for kernel density estimation, Moran’s I analysis, buffer zone analysis, and Getis-Ord Gi* spatial analyses. Meanwhile, the indicator data were incorporated into Spearman’s correlation analysis and random forest regression to evaluate and validate the relative importance of influencing factors. This integrated framework enhances methodological rigor and interpretability and ensures the reliability of conclusions regarding the spatial distribution characteristics of China’s marine economy.

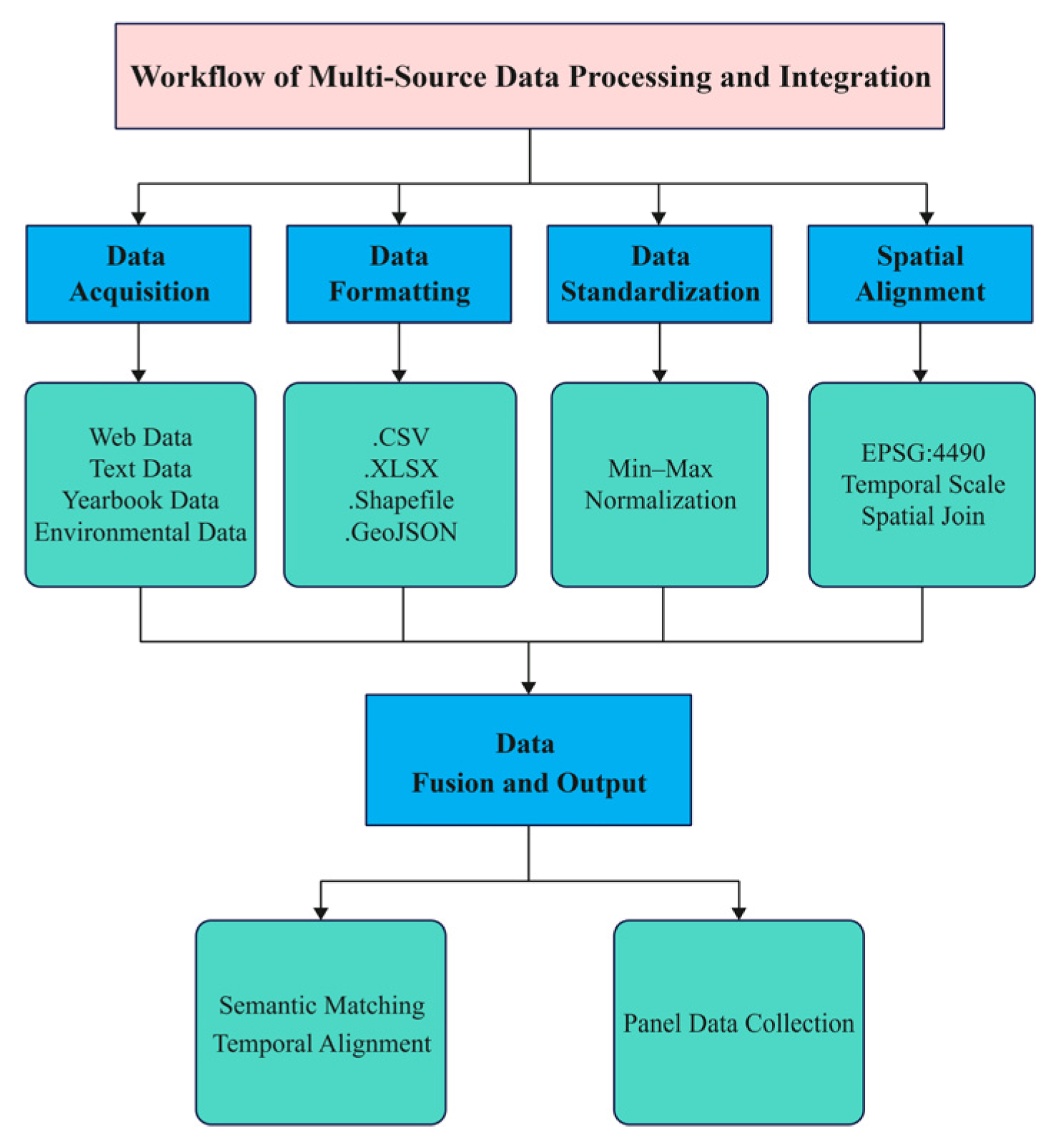

3.2.1. Data Preprocessing

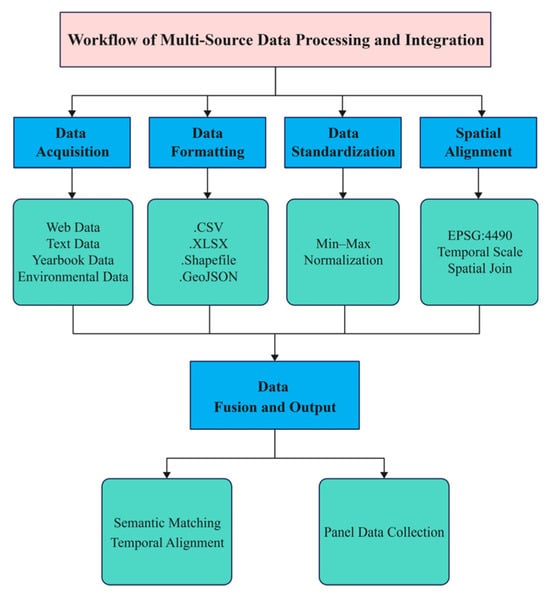

The three categories of data were integrated through an AI-based multi-source data fusion algorithm, ensuring a unified spatial reference system (EPSG:4490) [47] and temporal scale (2013–2023). During the data fusion phase, variables from diverse sources were standardized in units and format, resulting in a panel dataset with consistent temporal and spatial attributes, which was spatially linked and visualized in ArcGIS using the Spatial Join function.

Data Acquisition: automated data collection was performed using AI-powered web scraping and AI Agent frameworks, extracting economic, geographic, and ecological indicators from websites, policy documents, statistical yearbooks, and marine databases. This process enabled intelligent and large-scale data retrieval across multiple sources.

Data Formatting: under the Python 3.10.11 environment, the pandas and geopandas libraries were employed to clean and reformat multi-source data in CSV, XLSX, Shapefile, and GeoJSON formats. Field naming conventions, date formats, and coordinate attributes were standardized to ensure structural consistency among heterogeneous datasets.

Unit Standardization: to ensure cross-variable comparability, range standardization was applied to harmonize units and eliminate dimensional disparities across all variables.

Spatial Matching: a unified coordinate system (EPSG:4490) was applied to ensure spatial alignment between vector geographic elements, including provincial boundaries, coastlines, islands, and marine zones, and the associated economic attribute data by means of spatial joins.

Data Fusion and Output: through semantic matching and temporal alignment, multi-source data were integrated into a consistent structure, generating a standardized Excel-based panel dataset. This dataset provides a robust foundation for subsequent GIS spatial analysis and machine learning-based modeling of marine economic spatial distribution.

In the different stages of data preprocessing, a series of specialized tools and software environments were employed to ensure accuracy, consistency, and reproducibility. Web Scrape tools and AI Agent frameworks were first utilized for data acquisition, enabling the automated retrieval of the diverse datasets required by the constructed indicator system. These tools provided the initial multi-source raw data supporting the analysis of marine economic geography. Subsequently, the “pandas” and “geopandas” libraries in Python, executed within the Jupyter development environment, were applied to clean structured tabular data and to integrate vector-based spatial datasets. This step produced an unstandardized panel dataset of marine economic geographic information. During the unit standardization stage, the Jupyter environment continued to serve as the operational platform. The Min–Max normalization procedure, implemented through the command “x_norm = (x − x.min())/(x.max() − x.min())”, was applied to eliminate the dimensional heterogeneity across indicators. This process yielded a dimensionless and comparable panel dataset suitable for subsequent spatial and statistical analysis. Finally, ArcGIS 10.8.1 was used to perform spatial linkage between the processed panel dataset and vector geographic features, completing the multi-source data fusion process and establishing a unified spatial database for marine economic geographic analysis(see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Workflow of Multi-source Data Fusion.

3.2.2. Range Standardization

Following the AI-assisted data acquisition and format unification process, the weights of marine economic spatial indicators were derived based on standardized panel data. To eliminate dimensional discrepancies and ensure the comparability of heterogeneous indicators, the range standardization method was applied for normalization. This approach effectively preserves the relative differences among variables while aligning them within a common evaluation framework suitable for spatial and machine learning analyses. The standardization formula is expressed as

where represents the original value of indicator for province (or sample) ; and denote the maximum and minimum values of indicator respectively; is the normalized, dimensionless value scaled between 0 and 1.

3.2.3. Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) is a non-parametric statistical method used to estimate the probability density function of a random variable [48]. By applying the kernel density tool, this method analyzes the spatial density characteristics and distribution trends of point-based or polygonal features. It provides an intuitive representation of spatial clustering intensity and distribution patterns, thereby revealing the overall spatial structure and heterogeneity within the study area.

where represents the kernel density estimation value at the aggregation point, denotes the kernel function, is the bandwidth, refers to the total number of sample points, and indicates the distance between the sample point and the estimation point.

3.2.4. Global Spatial Autocorrelation

Global spatial autocorrelation is a fundamental concept in spatial statistics that measures the degree to which a geographical phenomenon is correlated across space. It evaluates the spatial relationship and differentiation within a study area based on both the attribute values of spatial features and their geographic locations [49].

The Global Moran’s I index is commonly used to quantify spatial autocorrelation, with values ranging from −1 to 1. When the Moran’s I value is greater than 0, it indicates a positive spatial correlation, meaning that similar values (e.g., high–high or low–low clusters) tend to be spatially aggregated. As the value approaches 1, the degree of clustering becomes stronger. Conversely, when Moran’s I is less than 0, it suggests a negative spatial correlation, implying that dissimilar values are spatially dispersed; as the value approaches −1, the level of dispersion increases. When Moran’s I is close to 0, the spatial distribution is considered random, indicating the absence of a significant spatial pattern.

where represents the observed value of region (); denotes the total number of observed regions; and is the spatial weight matrix describing the spatial relationships between regions and . To ensure spatial consistency and comparability of the analytical results, this study adopts a contiguity-based spatial weight matrix. Two provincial polygons are defined as neighbors when they share either a boundary or a vertex, where if adjacent and otherwise, with the diagonal elements set to . The weight matrix was row-standardized to eliminate the scale effects caused by varying numbers of neighboring units. Statistical significance was assessed through 999 random permutations, producing the corresponding Z-scores and p-values. This contiguity-based specification captures both rook and queen adjacency relationships, reflecting the intrinsic spatial linkages among administrative units, and is particularly suitable for province-level marine economic spatial analysis [50].

3.2.5. Buffer Zone Analysis

Buffer zone analysis is a spatial analytical method that establishes buffer zones of specified widths within the study area based on defined distance thresholds, enabling the examination of spatial characteristics within these zones [51].

where represents the buffer zone, denotes the set of points, is a point within the buffer zone, refers to the target object, and is the neighborhood radius measured in meters.

3.2.6. Getis–Ord Gi* Analysis

The Getis–Ord Gi* analysis is a type of spatial autocorrelation analysis that identifies statistically significant spatial clusters of high and low values within a dataset [52]. By calculating the Gi* statistic for each spatial feature and its corresponding Z-score, this method determines the presence of hot spots and cold spots under spatial weighting conditions. It is therefore an effective tool for detecting the intensity and significance of spatial clustering patterns in geographic phenomena.

where represents the Z-score of the Getis–Ord statistic, denotes the mean value of the attribute under analysis, is the standard deviation of all features, represents the attribute value of feature , indicates the spatial weight between features and , and is the total number of spatial features included in the analysis.

3.2.7. Spearman Correlation Analysis

Spearman correlation analysis is employed to examine the monotonic relationship between two variables. Given that the influencing factors selected in this study exhibit nonlinear associations [53], the Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the strength and direction of relationships among variables and their corresponding spatial distributions.

where and represent the rank values of variables and , respectively; and denote the mean ranks of and , respectively; and represents the correlation coefficient that measures the strength and direction of the association between the two ranked variables.

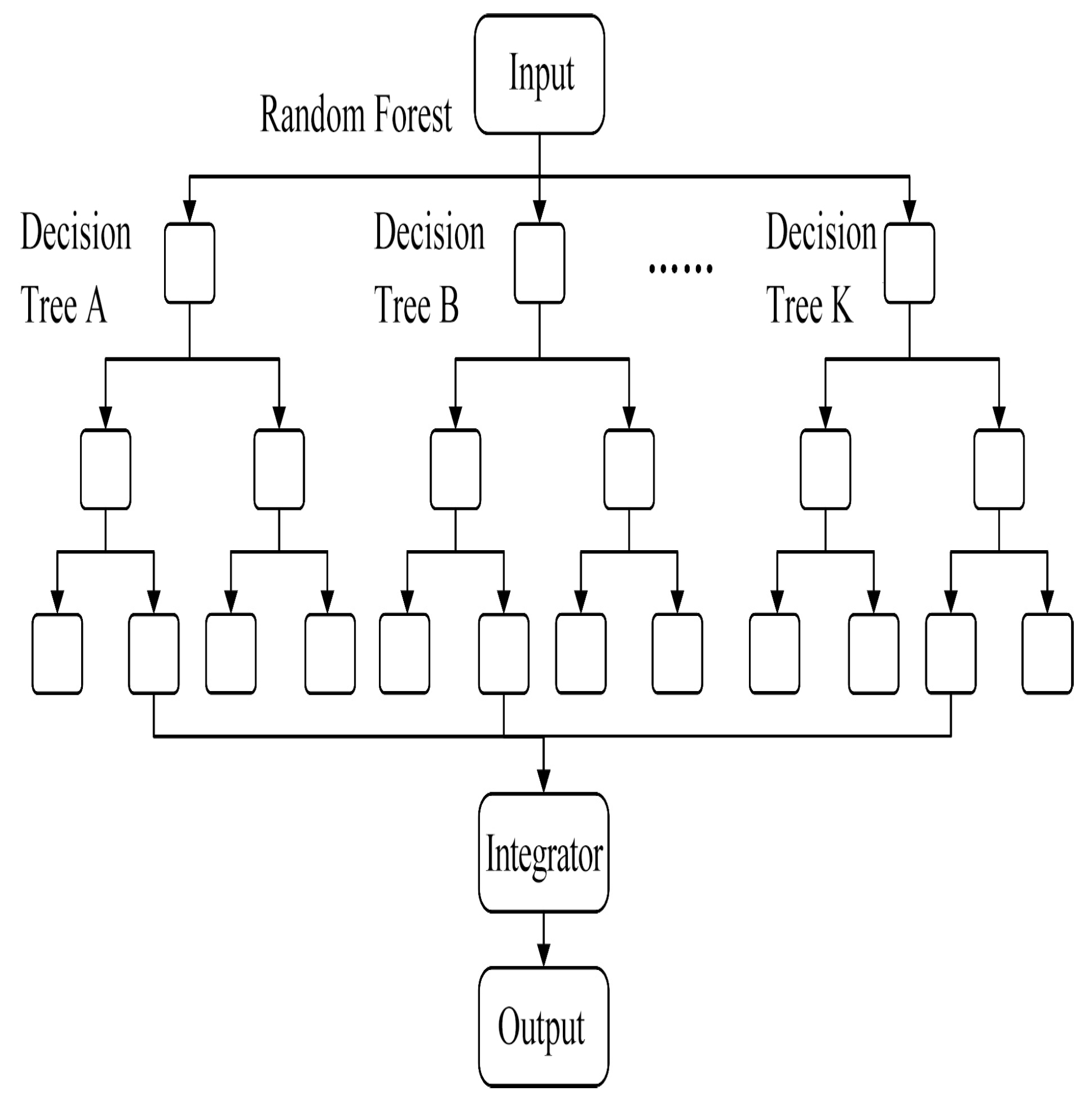

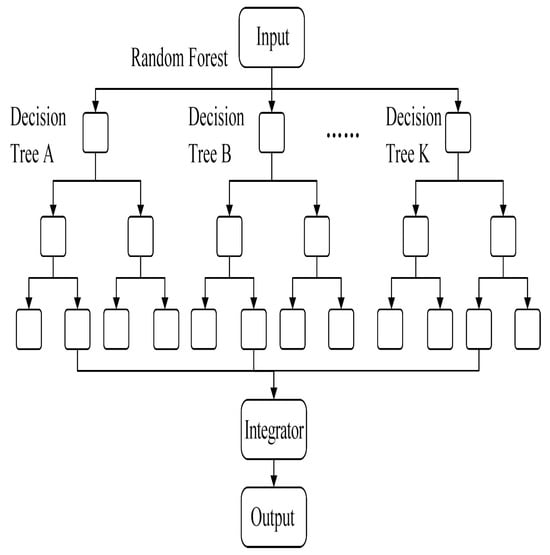

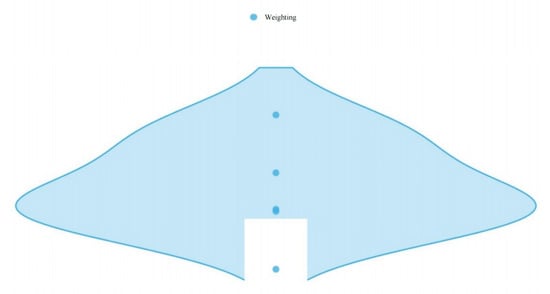

3.2.8. Random Forest Regression

Random Forest Regression is a machine learning method within the field of AI that constructs an ensemble of multiple decision trees to predict the target variable by aggregating their outputs [54]. Compared with traditional econometric regression models, the random forest approach introduces stochasticity, effectively reducing the risk of overfitting and enhancing the model’s generalization ability.

Moreover, the random forest regression model demonstrates high predictive accuracy and robustness when handling heterogeneous, multi-source datasets, without requiring extensive data preprocessing. The model also provides feature importance rankings, which reveal the contribution of each variable to the overall prediction process(see Figure 4). These characteristics enable the random forest regression model to effectively capture the intrinsic mechanisms underlying the spatial distribution patterns of China’s marine economic geography [55].

where denotes the random forest regression model; represents the sample set; refers to the decision tree; denotes the decision value obtained from the tree for sample ; and the function represents the voting (or aggregation) mechanism that integrates the predictions of all decision trees to produce the final output of the model.

Figure 4.

Random Forest Decision Tree Flowchart.

In configuring the Random Forest model, the primary hyperparameters were selected by balancing the sample size and model complexity to ensure both model stability and interpretability. The model was implemented using the following specification:

rf = RandomForestRegressor(

n_estimators = 500

max_depth = 10

min_samples_split = 2

min_samples_leaf = 1

random_state = 42

)

To evaluate the robustness and generalization capability of the RF model, the dataset was divided into a training set (70%) and a testing set (30%), and a 5-fold cross-validation procedure was implemented for model selection and performance assessment. In each fold, the model was trained on four subsets and validated on the remaining one, with the coefficient of determination (R2) and other performance metrics computed for each iteration. The mean and standard deviation across the five folds were then calculated, and 95% confidence intervals were derived based on the t-distribution to quantify the stability and statistical significance of model performance. To ensure full reproducibility, all stochastic processes were controlled by fixing the random seed at 42. This design enhances comparability across runs and ensures that the reported results reflect intrinsic model performance rather than random variation.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Spatial Distribution Density Characteristics

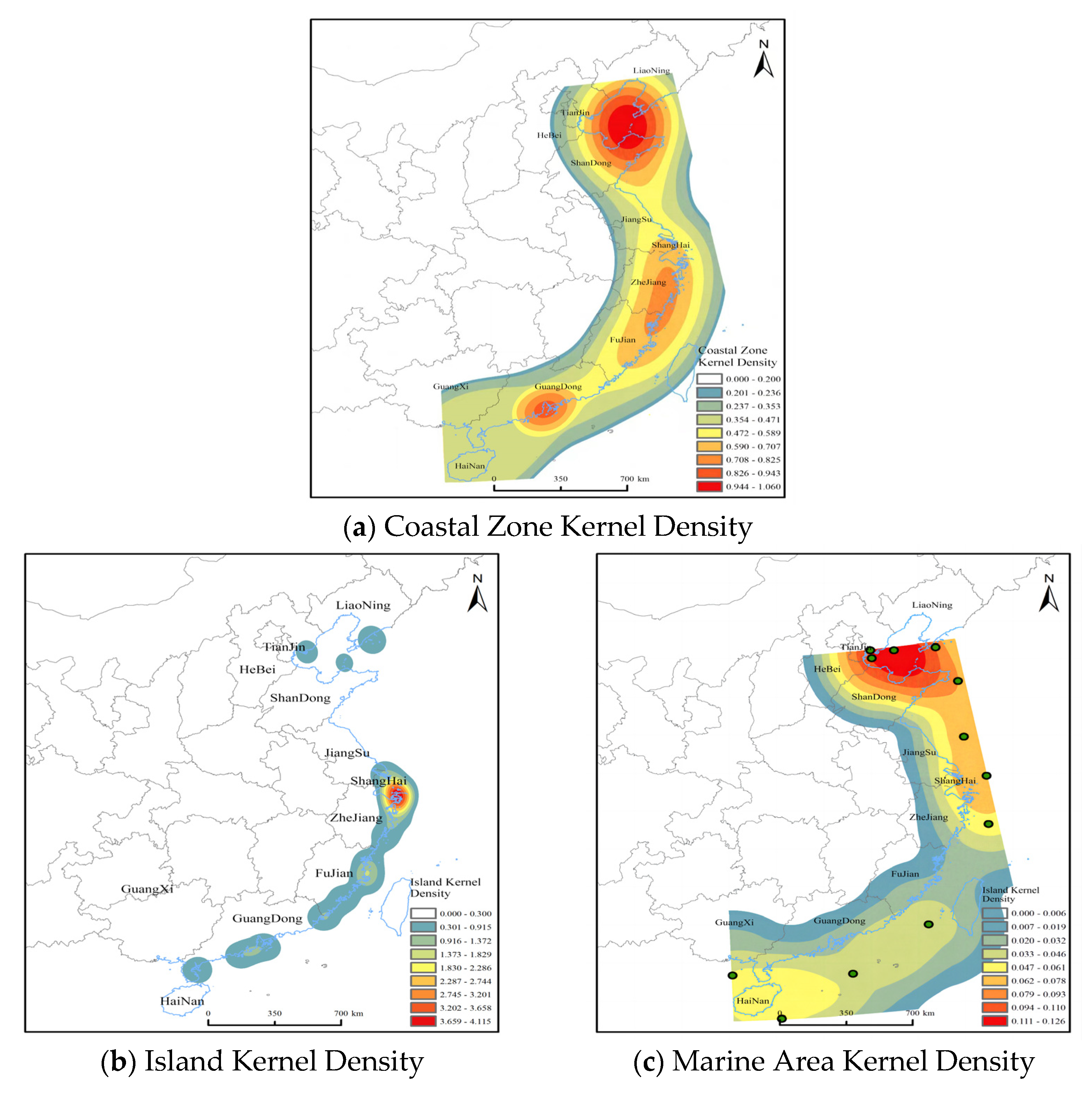

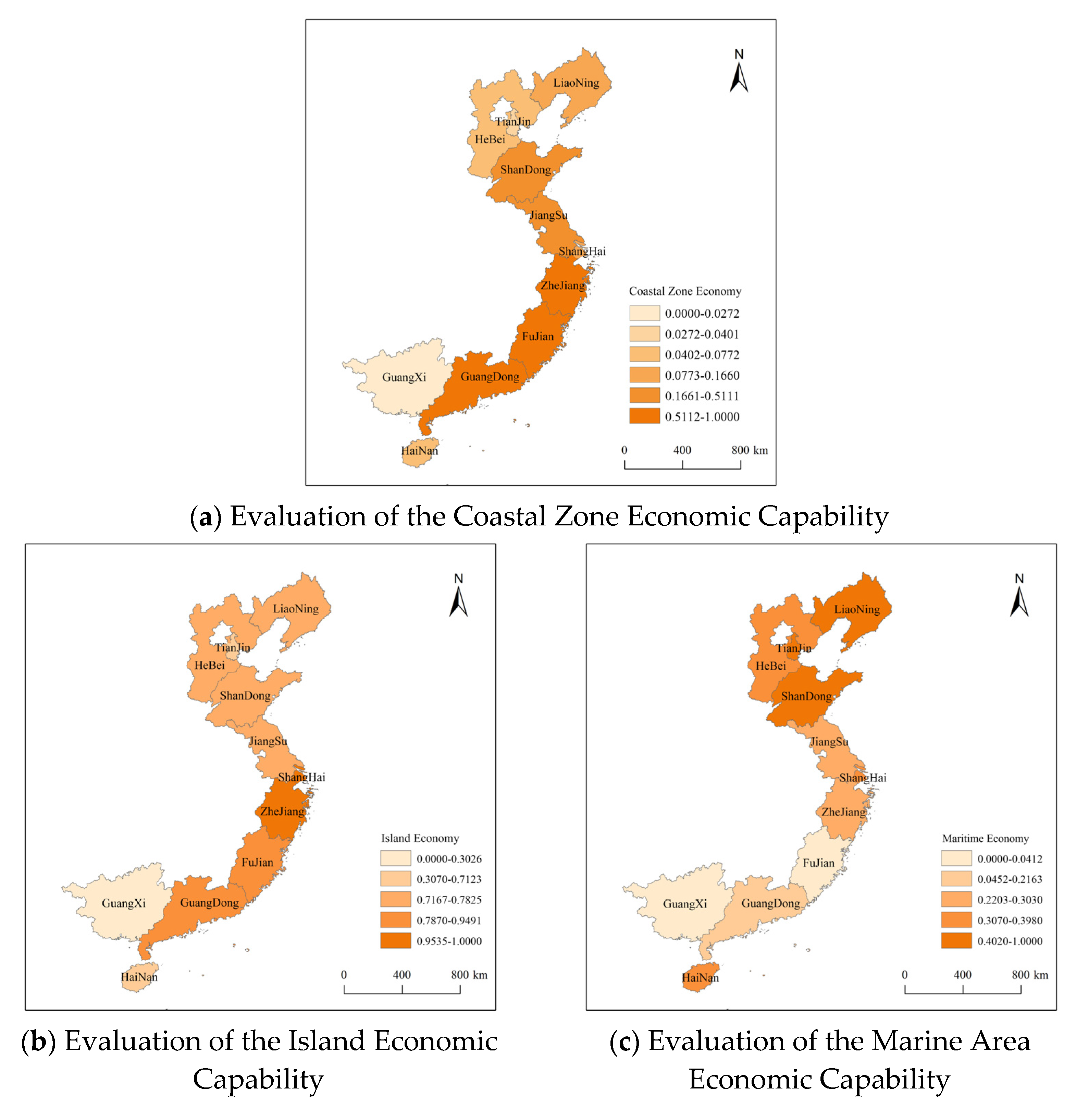

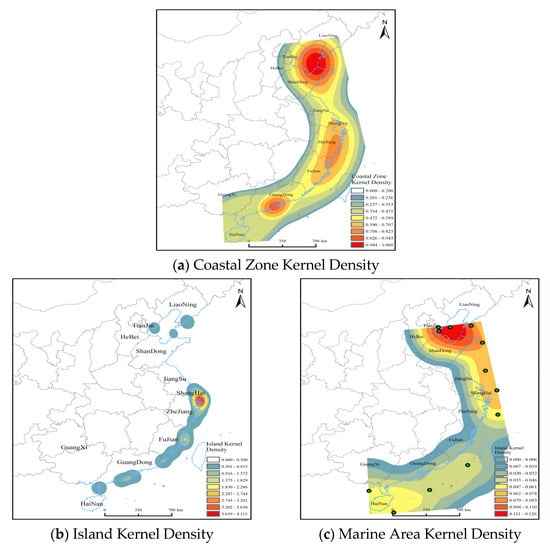

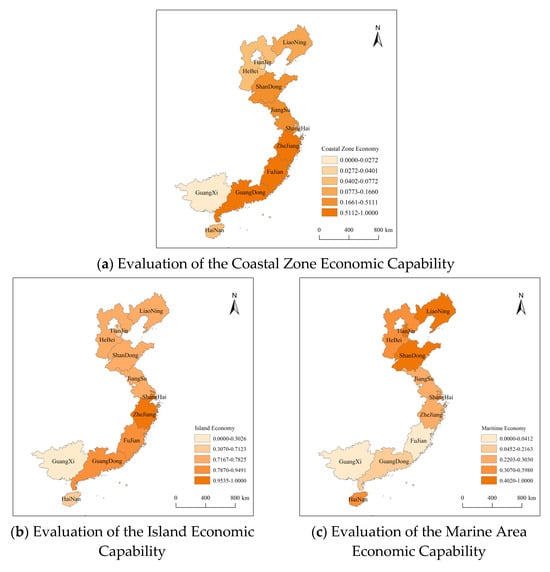

Kernel density estimation (KDE) is a non-parametric spatial analysis method used to identify the degree of concentration of geographic elements; higher values indicate greater spatial clustering intensity. Using ArcGIS 10.8, kernel density maps were constructed for coastal-zone, island, and marine economic activities (see Figure 5). The results reveal significant regional heterogeneity in the intensity and spatial distribution of marine economic activities along China’s coastal provinces. Overall, the spatial distribution of the marine economy exhibits a “point–belt–surface” structure. The specific statistical indicators for the kernel density analysis are presented in Table 3.

Figure 5.

Spatial Kernel Density Distribution of Marine Economic Geography.

Table 3.

Statistical Indicators of Kernel Density Estimation.

From the perspective of coastal-zone economic density, hotspot clusters are mainly concentrated in three areas: the Bohai Rim, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta. These regions form high density agglomerations. Within the northern coastal provinces of Liaoning, Tianjin, Hebei, and Shandong, the Bohai Rim presents a point-like breakthrough spatial pattern, with kernel density values distributed between 0.708 and 1.060 per 10,000 km2. The Jiaodong and Liaodong Peninsulas stand out due to their deep-water port advantages and national marine economic demonstration policies, which foster the formation of belt-shaped growth poles driven by emerging industries such as marine equipment and biomedicine. The Yangtze River Delta exhibits similar medium-to-high density levels, exceeding 0.708 per 10,000 km2, primarily concentrated along the Zhejiang coast, with two additional sub-clusters in Shanghai and northern Fujian (0.590 per 10,000 km2). The coastal zones of Jiangsu also show a “belt-to-surface” expansion trend, reflecting a multi-center synergistic development pattern under the region’s integrated marine economic strategy. The Pearl River Delta forms another medium-to-high-density cluster (0.472–0.943 per 10,000 km2), characterized by intensive coastal resource utilization linked to the Greater Bay Area’s port system, tourism development, and high intensity marine industries.

The kernel density results for island economies reveal a dispersed pattern with an one core and multiple nodes structure. The Hangzhou Bay area forms the primary concentration core, with several secondary density spots coexisting across the region. The high density peak exceeds 3.659 per 10,000 km2, displaying notable spatial heterogeneity. Economic and demographic activities are highly active around islands along both the northern and southern coasts of Hangzhou Bay. Medium density regions are mainly distributed among islands in central Fujian, eastern Guangdong (Chaozhou–Shantou), and central Guangdong, with density values ranging between 0.916 and 2.286 per 10,000 km2. In contrast, islands belonging to the Liaodong, Jiaodong, and Leizhou Peninsulas exhibit relatively low density (≤0.915 per 10,000 km2). The absence of clear medium or high value clusters in other coastal areas suggests sparse spatial development and limited economic functionality of islands in these regions.

For marine area economies, kernel density distribution exhibits pronounced regional differentiation, following a “high-in-the-north, low-in-the-south” clustering pattern. High-density areas are mainly located near coastal waters and zones with intensive economic activity, whereas low-density regions appear farther offshore. In northern waters, density values range between 0.047 and 0.126 per 10,000 km2, with the Bohai Sea showing the highest concentration, characterized by a “ring-like gradient decay” pattern centered on Bohai Bay, Liaodong Bay, and Laizhou Bay. Density gradually decreases radially outward from the core area. In southern waters, values range from 0.007 to 0.061 per 10,000 km2, exhibiting a “belt-like increasing” trend extending from Fujian’s coastal waters toward those of Hainan, indicating progressive intensification of marine economic activities along the southern seaboard.

The results of the kernel density analysis clearly delineate the gradient differentiation pattern of marine economic spatial development across China’s coastal provinces. The coastal zone economy has formed extensive high-density agglomeration belts driven by the three major urban clusters, with its spatial structure evolving from “point breakthroughs” toward a coordinated “belt-to-surface” expansion. The island economy exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity, characterized by a core concentration around Hangzhou Bay accompanied by multiple scattered high-density nodes, indicating significant regional imbalance. The marine area economy presents a distinct north–south gradient, where the northern Bohai Sea displays a radial attenuation pattern from a central core, contrasting with the southern coastal waters that demonstrate a belt-shaped increasing trend. Overall, the spatial distribution characteristics of the marine economic kernel density reflect the combined effects of resource endowment, policy orientation, locational conditions, and economic foundation, jointly shaping the observed spatial agglomeration effects.

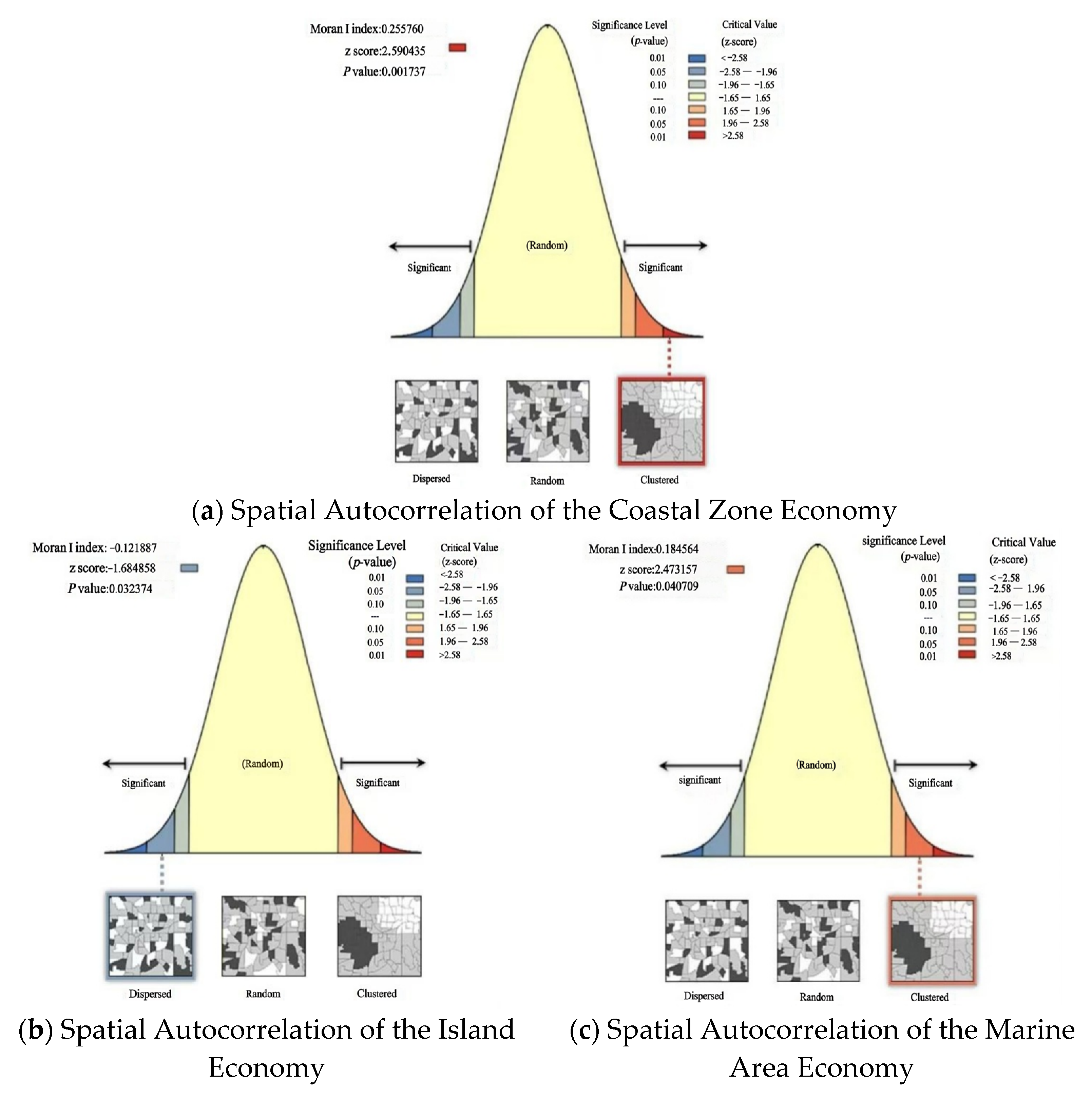

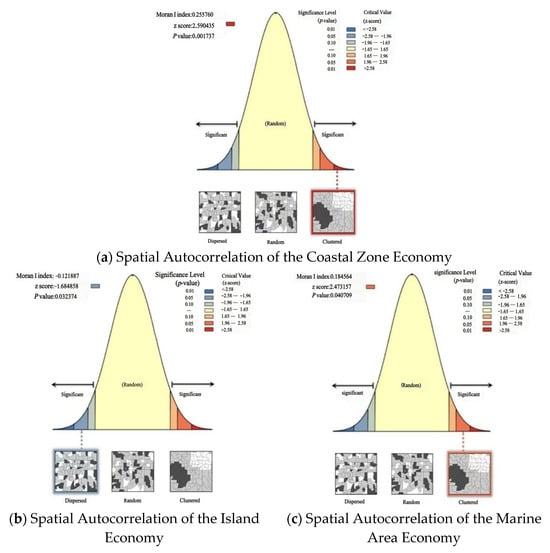

4.2. Spatial Association Distribution Characteristics

To investigate the spatial autocorrelation characteristics of China’s marine economic geography, GIS technology was employed to perform a global spatial autocorrelation analysis based on the Global Moran’s I index for the spatial distribution patterns of the coastal zone economy, island economy, and marine area economy. As shown in Table 4, the calculated Moran’s I values for all three indicators within the marine economic geographic space have passed the significance test, indicating that the spatial distribution of China’s marine economy exhibits a significant degree of spatial autocorrelation(see Figure 6).

Table 4.

Global Moran’s I of Marine Economic Geography.

Figure 6.

Spatial Autocorrelation Distribution of Marine Economic Geography.

The results of the Global Moran’s I analysis reveal that the coastal zone economy (Moran’s I = 0.256, p < 0.01) exhibits a significant positive spatial autocorrelation, with a z-score of 2.59 (>2.58), indicating a highly clustered spatial distribution pattern. Core port cities such as Qingdao and Shenzhen, together with major coastal industrial belts like the Yangtze River Delta and the Pearl River Delta, have formed economic high-value clusters through industrial chain synergies and increased population density (population density weight = 0.098). Moreover, policy guidance represented by the establishment of Free Trade Zones, combined with improved infrastructure connectivity indicated by a transportation network density weight of 0.106, further strengthens the clustering effect.

The island economy (Moran’s I = –0.122, p = 0.032) shows a negative spatial autocorrelation, with a z-score of −1.68, suggesting a dispersed spatial distribution. The relatively low level of significance reflects the influence of geographical isolation (offshore distance weight = 0.118) and natural disaster impacts (disaster loss weight = 0.156). The dispersed pattern of economic activity hinders large-scale industrial clustering, and the economy remains heavily dependent on local resources, particularly the fisheries sector (fishery output weight = 0.201). Consequently, most islands exhibit a typical “isolated-island” spatial pattern.

The marine area economy (Moran’s I = 0.185, p = 0.041) also demonstrates a positive spatial autocorrelation, although weaker than that of the coastal zone economy. The z-score of 2.47 indicates a moderate degree of localized spatial clustering. The concentration of energy exploitation hotspots (marine oil and gas development weight = 0.117) and logistical hubs (port throughput weight = 0.109) contributes to the formation of belt-shaped clustering zones, exemplified by the South China Sea oilfields and the Bohai Bay port cluster.

To further reveal the local spatial clustering characteristics of different types of marine economic activities, this study applied the Local Moran’s I (LISA) analysis based on the results of the global Moran’s I. The LISA method captures spatial similarity or dissimilarity between each observation unit and its neighboring units, identifying local clustering patterns such as High–High (H–H), Low–Low (L–L), High–Low (H–L), and Low–High (L–H). The results are presented in Table 5. The findings demonstrate significant differentiation in the local spatial structures among the three types of marine economies. For the coastal economy, H–H clusters (0.284126) dominate, primarily concentrated along the Bohai Rim and Pearl River Estuary, indicating a strong spatial concentration of coastal economic activities. L–L clusters (0.176034) are mainly distributed along the Guangxi and Hainan coasts, reflecting relatively weak economic activity in southern coastal areas. The island economy is mainly characterized by L–L clustering (0.297803), accompanied by notable H–L (0.112658) and L–H (0.105702) outlier regions. This suggests pronounced spatial heterogeneity and uneven development levels among islands, consistent with the global Moran’s I results and revealing the overall spatial dispersion of island economic systems. The maritime economy exhibits a clear belt-shaped clustering pattern, with H–H clusters (0.246713) concentrated near the Shandong Peninsula and Pearl River Estuary, and L–L clusters (0.211406) distributed in the offshore waters of Guangxi and Hainan. This indicates a typical nearshore high-value and offshore low-value spatial pattern, reflecting the gradient transition of marine economic intensity from the coast to the open sea.

Table 5.

Local Moran’s I Index of Marine Economic Spatial Geography.

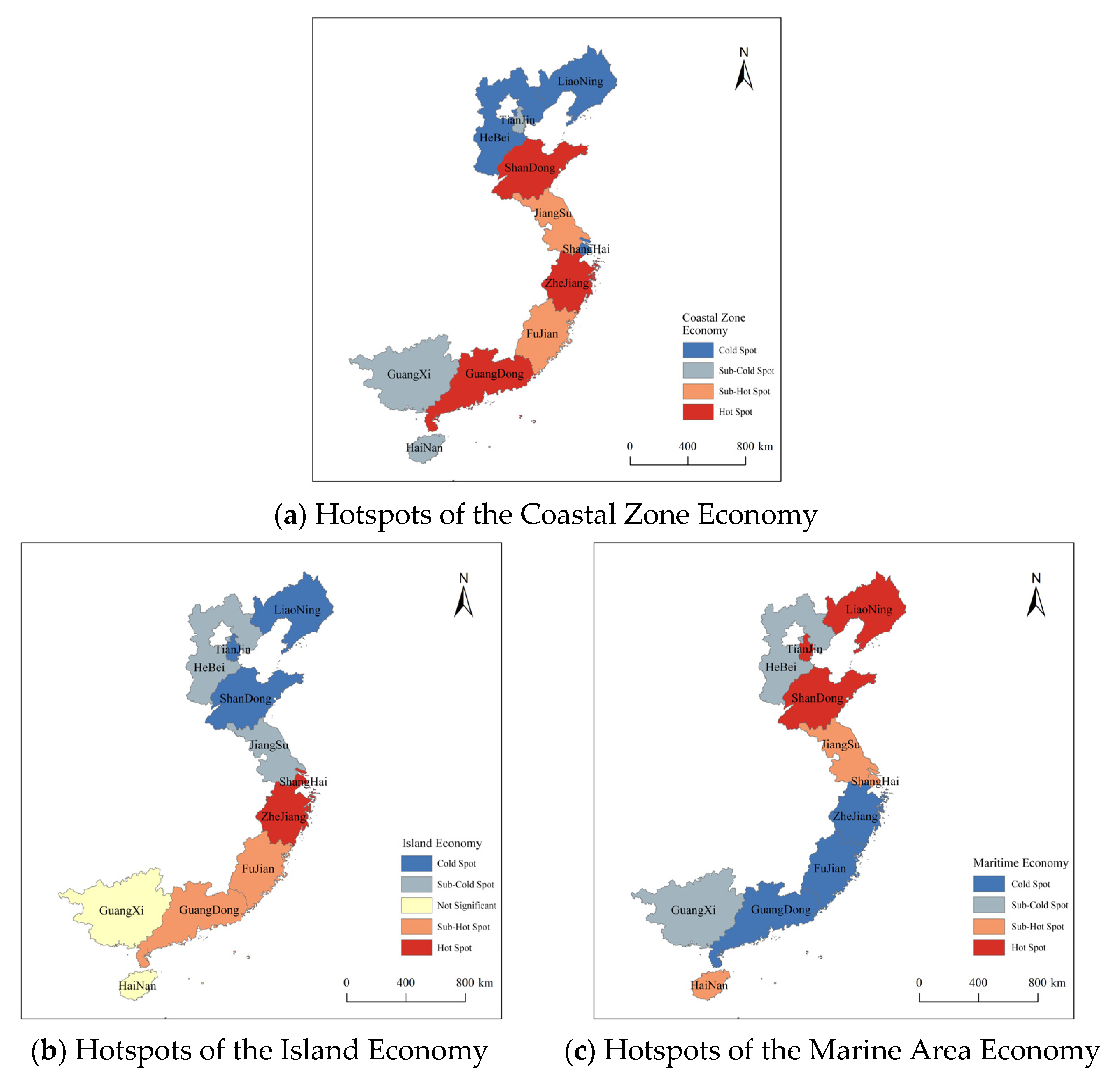

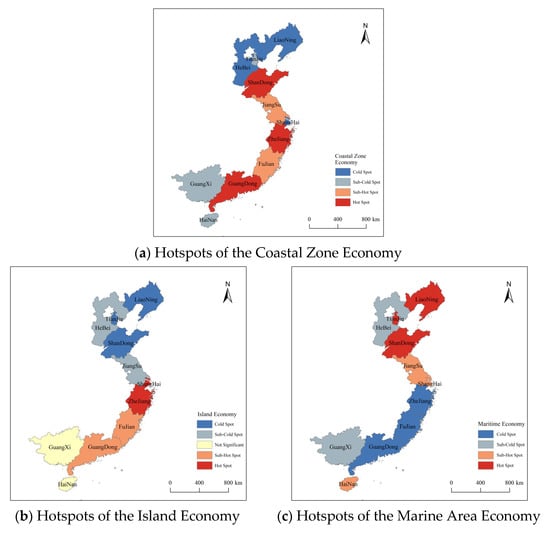

Building upon the results of the global spatial autocorrelation analysis, it is necessary to further examine how spatial associations manifest among different coastal provinces. To this end, a hotspot analysis was conducted to identify spatial clustering characteristics across multiple indicator layers within China’s marine economic geography. Using the GiZScore field as the statistical variable and applying the natural breaks classification method (see Table 6), various hotspot regions were categorized, and the spatial hotspot maps of China’s marine economic geography were generated (see Figure 7). To ensure the scientific validity and comparability of the hotspot analysis results, this study employed the Getis–Ord Gi* statistic to test the significance of spatial clustering in China’s marine economic geography. By calculating Z-scores, the spatial aggregation characteristics were identified, and regions were classified into different significance levels according to the standard normal distribution thresholds. To minimize potential bias caused by spatial scale effects, a Monte Carlo simulation with 1000 random permutations was conducted to verify the robustness of the results, and the standard error (σ ≈ 0.041) remained within a fluctuation range of ±2%, indicating that the findings possess high confidence and reproducibility. Overall, the spatial distribution of the marine economy exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity and gradient differentiation, with an overall pattern characterized as “hot in the south, cold in the north; strong in the east, weak in the west”.

Table 6.

Classification Criteria for Getis–Ord Gi* Hotspot Analysis.

Figure 7.

Hotspot Distribution of Marine Economic Geography Based on the Getis–Ord Gi*.

As shown in Figure 7, the coastal zone economy hotspots are primarily concentrated in three major urban clusters—the Yangtze River Delta (Zhejiang), the Shandong Peninsula (Shandong), and the Pearl River Delta (Guangdong). All of these areas exhibit Z-values greater than 2.58, corresponding to a confidence level above 99%. The average Gi* value of these regions is 0.312 ± 0.024, indicating a high-density clustering of coastal economic activities. These regions demonstrate advanced coastal zone economic development, diversified industrial structures, highly developed port economies, well-established coastal industrial systems, and favorable policy synergies, indicating a high level of economic activity and spatial clustering. Conversely, the Bohai Rim region (Liaoning, Hebei, Tianjin) and the North Gulf region (Guangxi) are identified as cold or sub-cold spots, with Z-values < −2.58 and −2.58 ≤ Z ≤ −1.96. The Bohai Rim faces the challenge of transforming its traditional heavy industries, while emerging marine industries have yet to achieve significant scale effects. Although Guangxi benefits from proximity to ASEAN markets, its port infrastructure and industrial synergy remain limited, constraining the full potential of its “marine-oriented economy.” Hainan, despite being designated as a Free Trade Port, remains a cold spot, reflecting the early-stage transition from policy advantage to tangible industrial outcomes.

The island economy shows distinct spatial heterogeneity. Southeastern coastal provinces such as Fujian, Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Shanghai exhibit “hotspot” or “sub-hotspot” patterns at confidence levels exceeding 95%, with Z-values ranging between 1.96 ≤ Z ≤ 2.58 and Z > 2.58, indicating strong island economic activity and more advanced utilization of island resources compared to other provinces. In contrast, northern coastal provinces including Hebei, Shandong, and Liaoning are categorized as “coldspots” or “sub-coldspots,” each exceeding 90% confidence levels. Notably, Guangxi and Hainan did not pass the significance threshold, with Z-values between −1.96 and 1.96, and thus are identified as statistically non-significant regions in the hotspot analysis.

Regarding the marine area economy, the northern marine regions display significant hotspot clustering at a 99% confidence level, particularly in Liaoning and Shandong, whereas Hebei appears as a sub-coldspot region. Most eastern and southern marine areas are classified as coldspots or sub-coldspots, with only Jiangsu and Hainan showing sub-hotspot characteristics at a 95% confidence level. The spatial differentiation of marine area hotspots is closely associated with regional disparities in marine resources, such as oil and natural gas reserves, and the varying influence of industrial structure on the intensity of marine resource exploitation.

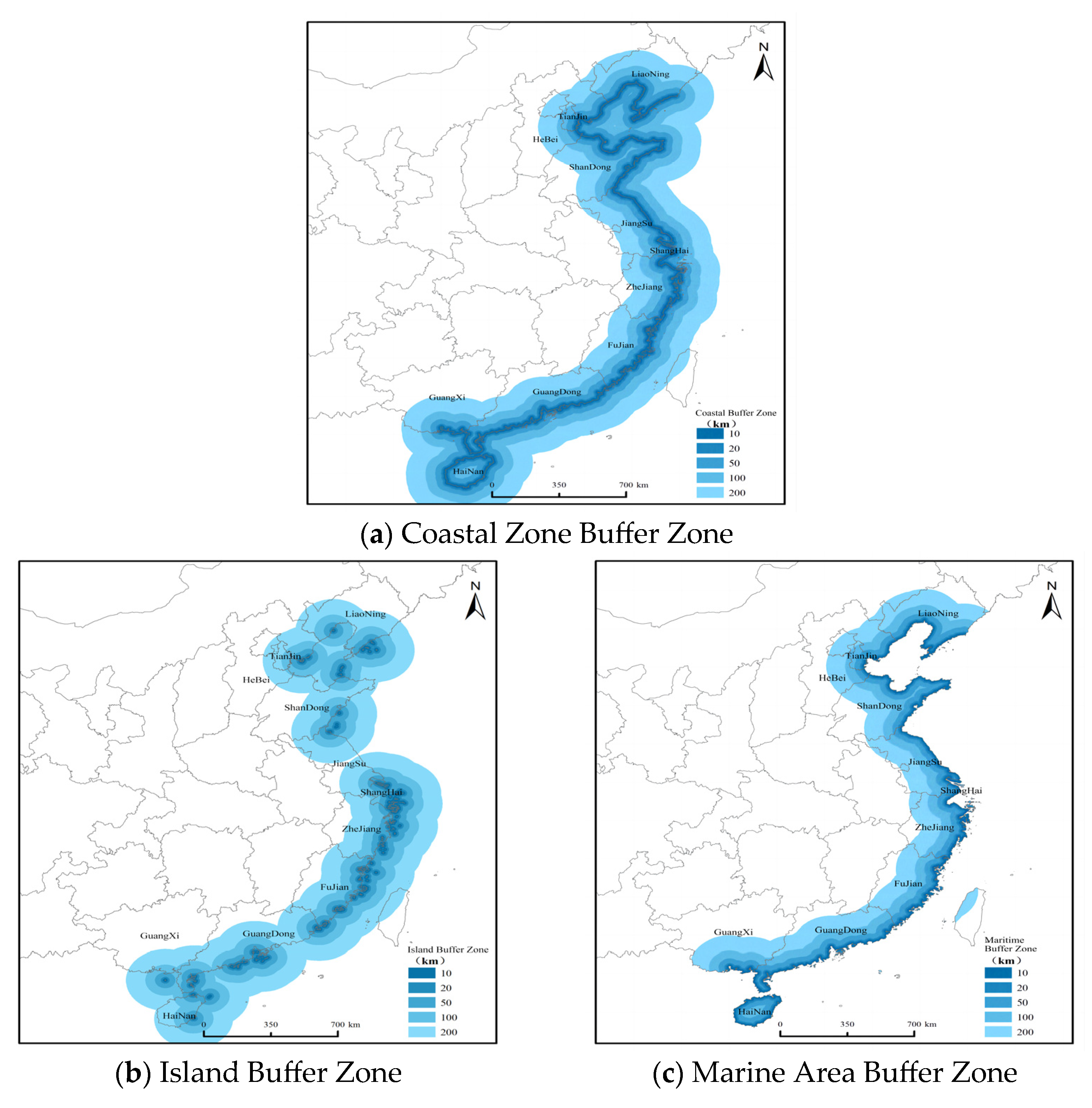

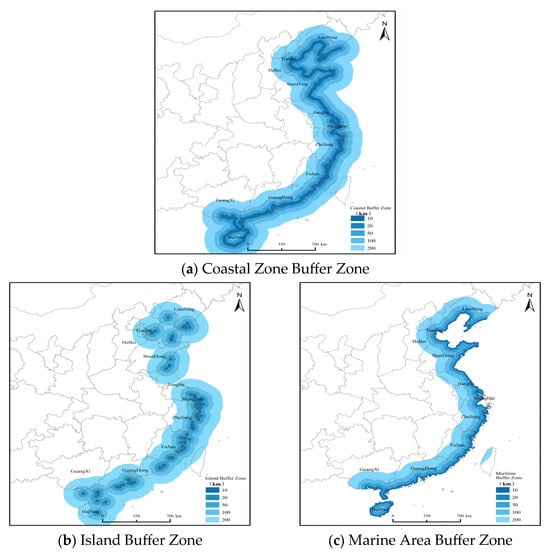

4.3. Spatial Buffer Zone Distribution

Buffer analysis is commonly employed to explore spatial proximity relationships and to reveal the influence range and interaction mechanisms among geographical elements. The fundamental principle involves constructing buffer zones of specific widths around a given spatial feature, thereby expanding its two-dimensional spatial extent and performing overlay analysis with target elements to uncover spatial interactions and impact mechanisms [56]. The spatial buffer structure effectively delineates a three-tier zonal system of China’s marine economy, progressing sequentially from the nearshore resource utilization zone, to the mid-range industrial upgrading zone, and ultimately to the deep-sea strategic expansion zone. With increasing buffer distance, the economic complexity, technological intensity, and global connectivity of marine economic activities steadily intensify.

Using the ArcGIS 10.8 platform, the buffer zones of coastlines, islands, and marine areas across China’s coastal provinces were defined from 0 km to 200 km, divided into six hierarchical levels: 0 km, 10 km, 20 km, 50 km, 100 km, and 200 km. The spatial buffer analysis results reveal significant distance-decay effects and functional gradient differentiation in the activity levels of coastal, island, and marine economies. Specifically, larger buffer ranges correspond to higher levels of economic agglomeration intensity and industrial advancement(see Table 7).

Table 7.

Statistical Results of Spatial Intensity of Marine Economic Activities in Different Buffer Zones.

Consistent with Liu’s global-scale findings that revealed a positive correlation between buffer zone width and industrial activity intensity, indicating that wider buffer zones correspond to stronger spatially concentrated economic activities [57], this study further verifies such patterns within China’s coastal and marine economic systems. As shown in Figure 8, the coastal zone, island, and marine area economies exhibit stronger economic vitality in regions with broader buffer coverage. For the coastal zone buffers, regions within 0–20 km (e.g., Hainan, Guangxi) are dominated by fisheries, coastal tourism, and small-scale ports, characterized by dispersed economic activities highly dependent on natural resource consumption. The 20–50 km buffer zones (e.g., Hebei, Tianjin) represent medium-distance coastal belts, where port logistics, seafood processing, and coastal industries are concentrated. The 100–200 km buffer zones (e.g., Jiangsu, Guangdong, Shandong, Shanghai) constitute wide-range radiation areas, encompassing major port clusters (e.g., Shanghai Port, Ningbo–Zhoushan Port), advanced manufacturing bases (e.g., Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta), and marine technology innovation centers, exhibiting strong agglomeration effects and robust economic spillover capacity toward inland provinces.

Figure 8.

Spatial Buffer Zone Analysis of Marine Economic Geography.

For the island buffer zones, the 0–20 km near-island areas (e.g., Sanya in Hainan, Gulangyu in Fujian) focus on island tourism and aquaculture, yet are constrained by resource carrying capacity and transport limitations (e.g., Weizhou Island in Guangxi). The 20–50 km mid-range buffer zones feature port development and offshore renewable energy projects such as wind power, with some regions connected to the mainland via cross-sea bridges to enhance inland linkages. The 100–200 km deep-impact buffer zones cover archipelagos such as the Zhoushan Islands, characterized by the establishment of marine science parks and bulk commodity logistics hubs through coordinated land–sea industrial integration.

For the marine area buffers, the 0–20 km nearshore zones host fisheries and coastal wetland conservation activities; the 20–50 km zones represent intensive marine development areas, focusing on large-scale operations such as offshore oil and gas extraction (e.g., Bohai Oilfield) and navigation channel maintenance (e.g., Yangshan Deep-Water Port in Shanghai). The 100–200 km strategic expansion zones encompass distant-water fishing bases (e.g., Wenling, Zhejiang) and international shipping hubs (e.g., Nansha Port, Guangdong), reflecting China’s deep integration into the global marine economic network.

4.4. Overall Spatial Capability Evaluation

From the provincial perspective, GIS-based natural breaks classification was applied to evaluate multi-level indicators of China’s marine economic geography, resulting in the overall spatial capability evaluation map for coastal provinces (See Figure 9). The multi-tier assessment reveals significant provincial disparities and spatial differentiation patterns, demonstrating that marine economic activities exhibit spatially driven characteristics of “land–sea linkage”, “core–balance structure”, and “gradient–polarization effects.”

Figure 9.

Overall Spatial Capability Evaluation of Marine Economic Geography.

To ensure the comparability of indicators across different dimensions, the range standardization method was applied to normalize all raw variables to a dimensionless range of [0, 1]. The standardized dataset was then subjected to GIS-based natural breaks classification to spatially categorize the hierarchical indicators of China’s marine economic geography(see Table 8), thereby revealing the regional heterogeneity and spatial gradient structure of overall marine economic capacity. The results indicate that the spatial patterns of the comprehensive capability evaluation are consistent with the spatial distribution of each indicator. Distinct provincial differences are observed across the three economic dimensions. In the coastal zone economy, the gradient differentiation is pronounced, showing a clear north–south divide. Southeastern coastal provinces such as Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang possess substantially higher coastal zone economic levels (>929.32) compared with northern provinces such as Liaoning, Hebei, and Tianjin (>78.79). The island economy of coastal provinces generally ranks at an upper–middle level, with Zhejiang Province demonstrating the highest island economic performance (>5.65), serving as a benchmark region. Apart from Guangxi (>3.58) and Hainan (>4.25), other provinces display relatively balanced island economic capacities (>5.14). In contrast, the marine area economy exhibits pronounced advantages in northern coastal regions (>4.55), while eastern and southern marine economic levels show a gradual north-to-south gradient transition, with Hainan emerging as a regional leader in the southern marine economy.

Table 8.

Hierarchical Intervals of Normalized Marine Economic Geography Indices.

Overall, the hierarchical differentiation of spatial capability is jointly shaped by locational conditions, resource endowments, and policy orientation, reflecting the comprehensive influence of both natural and socio-economic drivers on the spatial evolution of China’s marine economic geography.

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis

To verify the robustness of the spatial analysis results of marine economic geography, this study conducted a sensitivity analysis for the three spatial subsystems of the coastal zone economy, the island economy, and the marine area economy, using panel data and spatial analysis models. By performing perturbation tests on indicator weights, spatial parameters, and model thresholds, the variations in model outputs under different conditions were evaluated to assess the consistency and reliability of spatial patterns, hotspot distributions, and correlation indices. When the observed variations in model outputs remain minimal under parameter perturbations, the spatial analysis results can be considered highly stable and robust.

Sensitivity Analysis of the Coastal Zone Economy: To examine the sensitivity of the coastal zone economy, the indicator weights were perturbed by ±10%, and the bandwidth of the kernel density estimation and spatial threshold parameters were adjusted. Subsequently, Moran’s I, hotspot distributions, and spatial clustering patterns were recalculated. The results indicate that the spatial changes in coastal economic hotspots were minimal, with a spatial overlap ratio of 87.5%, a Moran’s I variation rate of only 4.8%, a rank correlation coefficient (ρ) of 0.91, and an average hotspot center displacement of 35 km. These results demonstrate that the spatial aggregation pattern of the coastal zone economy remains highly consistent under different parameter settings, indicating strong model stability, low sensitivity to parameter changes, and robust spatial reliability.

Sensitivity Analysis of the Island Economy: The sensitivity analysis of the island economy was performed by perturbing indicator weights by ±10% and adjusting the buffer radius to assess the spatial response. The results show that after perturbation, the hotspot overlap ratio was 82.3%, with a rank correlation coefficient (ρ) of 0.88 and an average hotspot displacement of 60 km. These findings indicate that the island economy exhibits moderate-to-high stability under varying parameter conditions, with only minor spatial fluctuations occurring along the peripheral zones. Overall, the island economy demonstrates a reasonable level of robustness; however, compared to the coastal zone, its spatial response is more sensitive to geographic scale variations due to the inherent discreteness of island distribution.

Sensitivity Analysis of the Marine Area Economy: For the marine area economy, sensitivity testing was performed by applying ±10% perturbations to both indicator weights and spatial threshold parameters, followed by recalculation of the hotspot overlap ratio, Moran’s I variation, and hotspot displacement distance. The results reveal that after perturbation, the Moran’s I variation rate was 4.2%, the hotspot overlap ratio was 85.1%, the rank correlation coefficient (ρ) reached 0.86, and the average hotspot displacement was 43 km. These outcomes suggest that the spatial configuration of the marine area economy experiences only minor changes under parameter variations, with a stable hotspot clustering trend and strong spatial interpretability of the model.

To further compare the spatial stability of the three marine economic subsystems under different perturbation scenarios, a sensitivity indicator matrix (see Table 9) was constructed, evaluating robustness across four dimensions: changes in clustering intensity, spatial consistency, rank order stability, and hotspot center displacement. The results show that the coastal zone economy exhibits the highest robustness, indicating that its spatial aggregation structure is insensitive to parameter perturbations. The island economy displays moderate sensitivity, primarily influenced by the spatial discreteness of island distribution, whereas the marine area economy demonstrates overall stability with minimal hotspot displacement, reflecting its relatively consistent spatial clustering behavior.

Table 9.

Robustness Test Results of Marine Economic Spatial Systems.

5. Influencing Factors of Marine Economic Geography

5.1. Correlation Analysis of Influencing Factors

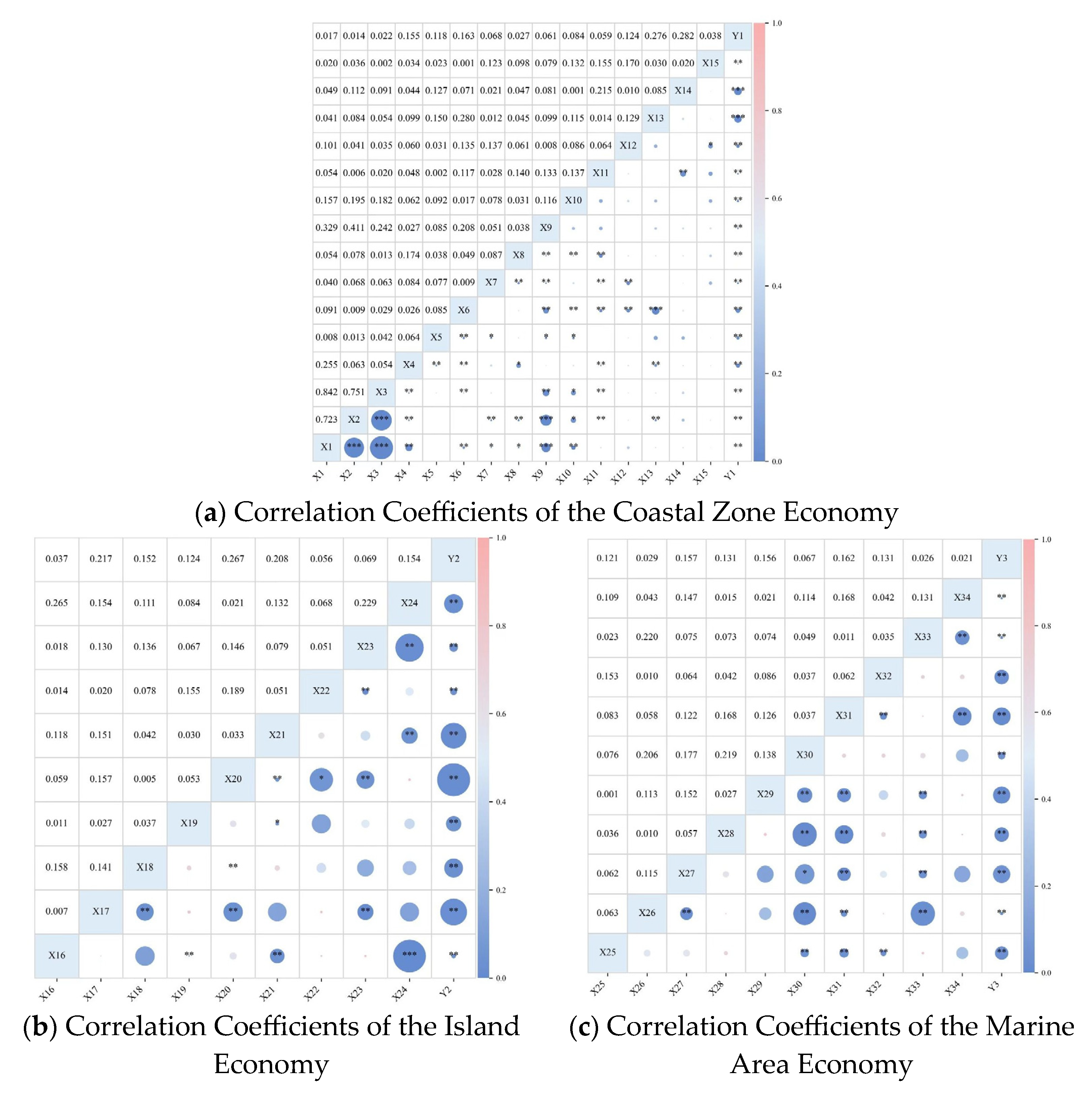

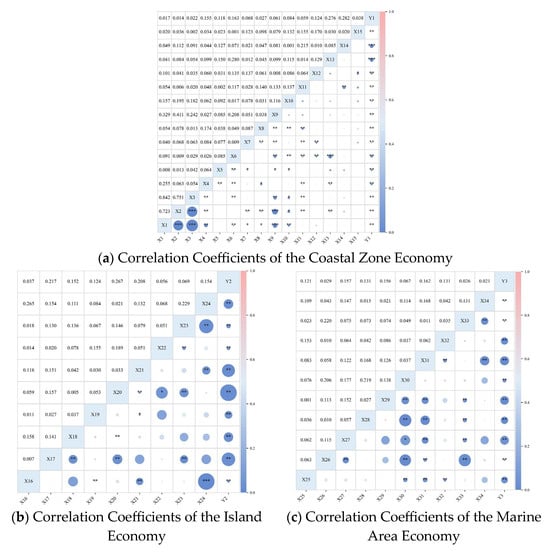

The spatial distribution pattern of China’s marine economic geography is the result of multiple interacting factors. Based on the indicator system constructed in Table 1, this study employed the Spearman correlation coefficient in Python 3.10.11 (via the “scipy” library) to evaluate the relationships among influencing factors within three dimensions: coastal zone economy (Y1), island economy (Y2), and marine area economy (Y3). The analysis was conducted to assess the degree of correlation between each factor and its corresponding indicator layer. As shown in Figure 10, significant differences were observed in the influence intensity of various factors across different indicator dimensions. Overall, all dimensions exhibited a positive correlation with the spatial distribution of China’s marine economic geography. From the perspective of indicator hierarchies, the most influential drivers of the marine economic spatial pattern are primarily associated with social environment, land–sea resource endowment, and economic value dimensions. It is noteworthy that the Spearman correlation coefficients among variables are generally below 0.3, indicating relatively weak linear or monotonic relationships between individual explanatory variables and the dependent variable. This outcome reflects the complexity and nonlinear nature of the marine economic system, in which development is shaped by the combined effects of natural geography, industrial structure, policy orientation, and socio-cultural factors. The interactions among these drivers are often characterized by nonlinear superposition, threshold effects, and spatial heterogeneity, leading to non-significant simple correlations between variables. Against this backdrop, the use of the Spearman correlation analysis in this study serves to identify the overall direction and significance of the relationships between variables and indicator dimensions, thereby confirming their statistical associations. This lays a foundation for the subsequent introduction of nonlinear machine learning models, which can capture latent nonlinear interactions and complex cross-factor effects among weakly correlated variables, ultimately enabling a more comprehensive interpretation of the spatial configuration of China’s marine economy.

Figure 10.

Correlation Coefficients of Marine Economic Geography(“*, **, ***” indicate significance levels at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels).

Across all three dimensions, most influencing factors exhibit positive correlations with the marine economic spatial distribution. In the coastal zone economy, the proportion of non-agricultural industries (X14) and per capita GDP (X13) show the highest correlations (0.282 and 0.276, respectively). These are followed by per capita available land resources (X6, 0.163), while per capita arable land (X4) and transportation network density (X12) display weaker correlations (0.155 and 0.124). The lowest correlation is observed for river runoff (X1, 0.017), suggesting that industrial restructuring and regional economic development exert a stronger influence on coastal economic performance than natural environmental variables. Factors such as river runoff, precipitation, and per capita water availability show correlations below 0.1, implying that natural conditions have limited short-term impacts on coastal economic growth. Therefore, the optimization and upgrading of the marine industrial structure emerge as key drivers shaping the spatial layout of the coastal zone economy. The share of non-agricultural industries (X14) serves as a critical indicator reflecting the level of industrial structure optimization and economic transformation in coastal regions, exhibiting a clear positive correlation with the coastal zone economy (Y1). This relationship reveals a chain-effect mechanism in which regional economies progress from industrial upgrading to factor agglomeration and productivity enhancement [58]. An increasing proportion of the secondary and tertiary sectors promotes spatial concentration and specialization of production factors, thereby stimulating the agglomeration of port economies, coastal manufacturing, and modern service industries. During the structural adjustment phase, the rise in non-agricultural industry share represents the spatial reallocation of capital and technology, directing labor and investment toward high value-added sectors. Subsequently, in the diffusion phase, industrial clustering enhances productivity and factor mobility, which in turn drives economic spillover effects and the spatial expansion of surrounding urban economies. From an interactional perspective, the synergistic relationship between the non-agricultural industry share, transportation network density, and regional GDP underscores the coupled amplification effect between industrial upgrading and locational advantages [59]. This suggests that under favorable geographical and infrastructural conditions, industrial restructuring can maximize spatial economic efficiency, reinforcing the combined influence of industrial structure optimization and spatial accessibility in shaping coastal economic development.

For the island economy, offshore distance (X20) exhibits the strongest positive correlation (0.267), indicating that islands closer to the mainland benefit from enhanced resource connectivity and economic integration. This is followed by annual tourist arrivals (X17) and per capita fishery output (X21), highlighting the importance of tourism and fisheries in shaping island economic patterns. In contrast, natural environment factors such as per capita island area (X16), vegetation coverage (X22), and air quality (X23) show weak correlations (0.037–0.069), suggesting limited direct influence on island economic performance. The offshore distance (X20), which serves as an indicator of geographical accessibility, plays a critical constraining role in shaping the spatial configuration of island economies. A shorter offshore distance effectively reduces transportation and transaction costs between islands and the mainland, thereby strengthening industrial chain extensions and regional linkages. This process forms a spatial proximity mechanism characterized by enhanced factor mobility, economic synergy, and network connectivity [60]. Through improvements in transportation infrastructure and network accessibility, offshore proximity facilitates the spatial diffusion of tourism, fisheries, and service industries, promoting continuous convergence of goods, information, and human flows. The economic relationship between islands and the mainland exhibits a cooperative and symbiotic nature, supported by resource complementarity and industrial outsourcing. Consequently, the reduction in offshore distance not only enhances the absorptive capacity of island economies toward inland urban economic spillovers but also drives industrial integration and structural upgrading, reinforcing the spatial coupling between geographical accessibility and economic development.

In the marine area economy, the per capita marine GDP (X31) has the highest correlation coefficient (0.162), followed by per capita marine product output (X27) and per capita sea sand extraction (X29). These findings indicate that the level of marine economic productivity and the extent of resource exploitation play central roles in promoting marine economic development. Conversely, factors such as per capita mariculture area (X26), polluted sea area ratio (X30), share of marine-related employment (X33), and port cargo throughput (X34) exhibit low correlations (<0.1), reflecting their limited direct influence on the spatial structure of marine economic activity. The per capita marine GDP (X31) serves as a key indicator of the comprehensive capacity for resource utilization and industrial upgrading in coastal regions. A higher level of marine GDP per capita reflects an economy’s ability to reinforce itself through capital reinvestment and investment diffusion, manifesting in a three-phase mechanism of resource-driven development, industrial transmission, and economic feedback [61]. In the resource-driven phase, marine resources are capitalized through industries such as fisheries, marine mining, and ocean engineering, driving the vertical extension of the industrial chain. During the industrial transmission phase, accumulated capital facilitates the transition toward processing, manufacturing, and high-tech sectors, generating a “secondary growth effect” within the marine economy. Finally, in the economic feedback phase, industrial revenues are reinvested into ecological governance and infrastructure development, establishing a regenerative feedback loop that sustains both economic growth and marine environmental resilience.

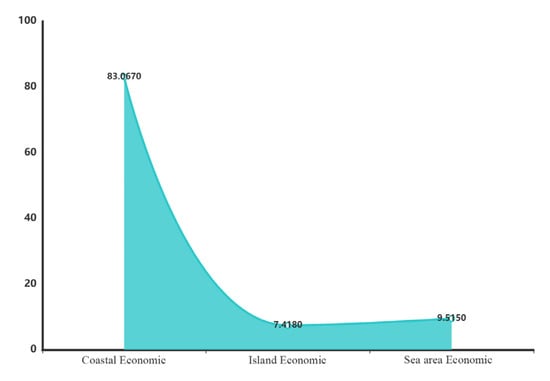

5.2. Analysis of the Importance of Influencing Factors

As a machine learning technique, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm operates based on an ensemble of numerous decision trees [62]. Each tree is trained using randomly selected variables and sub-samples from the dataset, and the importance of influencing factors is evaluated through weighted analysis of the resulting predictions [54]. To quantify the relative contribution of each factor to spatial differentiation within China’s marine economic geography, this study constructed and trained a random forest regression model, applying it to assess the importance of first-level indicators influencing the marine economic spatial structure. In this model, the overall marine economic geography served as the dependent variable, while the coastal zone economy, island economy, and marine area economy were treated as independent variables. Each influencing factor within the corresponding indicator layers was considered as a feature dimension in the model. The cross-validation results of the random forest model in this study are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Cross-validation results of the Random Forest Model.

The Random Forest Regressor package in R was employed for model training, producing a determination coefficient of R2 = 0.926 (see Table 11). Since R2 ranges between [0, 1], the obtained value indicates a high degree of model fit. Furthermore, the performance on the test set surpassed that of the training set, confirming that the model did not exhibit overfitting, and the R2 value is considered reliable.

Table 11.

Evaluation Results of the Random Forest Regression Model.

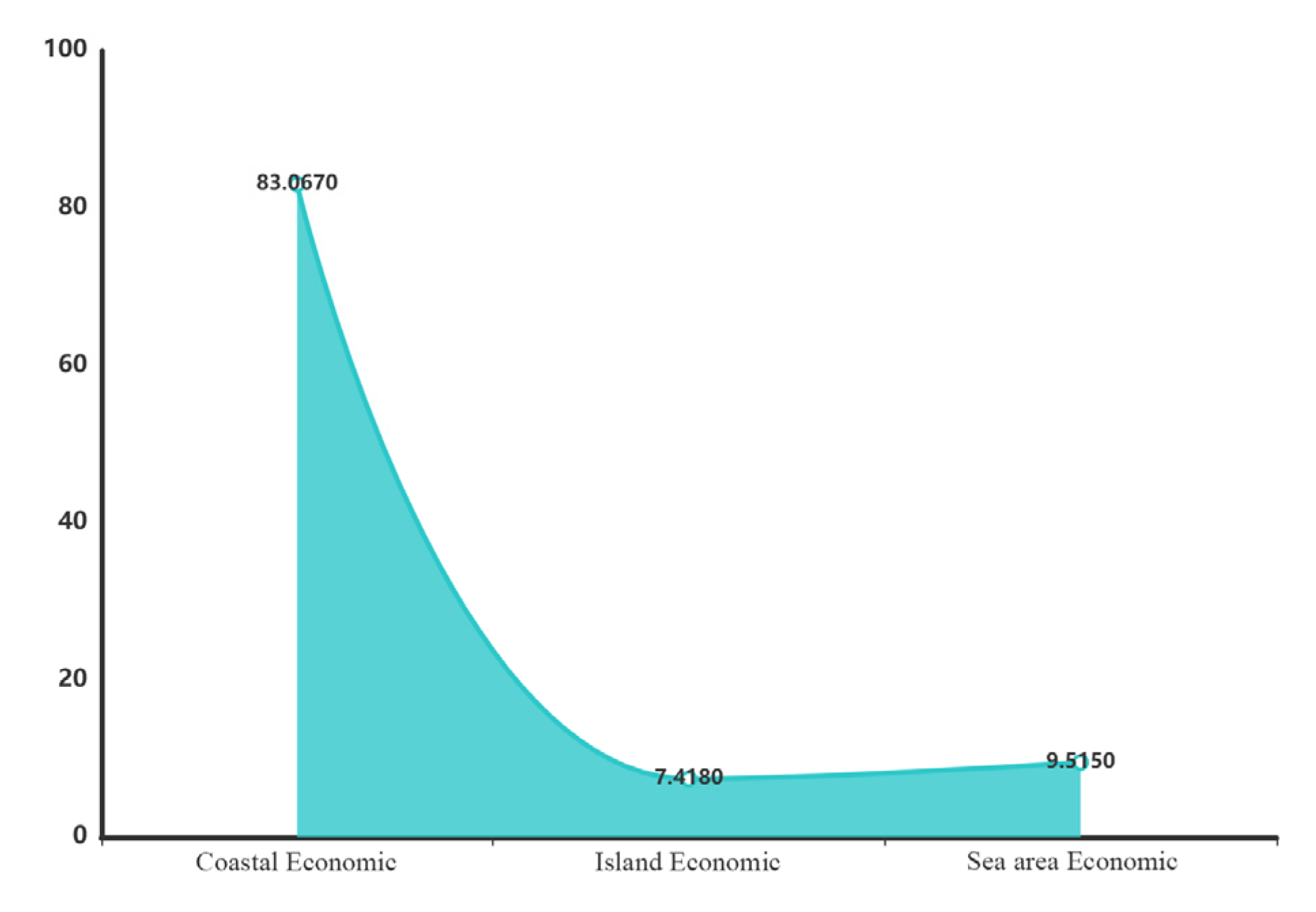

In evaluating the importance of influencing factors within the indicator layer of China’s marine economic geography, the Gini importance measure was adopted to quantify each feature’s contribution to model performance. Specifically, the Gini index reflects the degree of improvement in node purity during the decision tree’s splitting process, and features that contribute more substantially to prediction accuracy are assigned higher importance scores. This approach effectively captures the relative contribution of different variables to the overall model and has been widely applied in spatial econometrics and environmental economics research. To mitigate the scale effect arising from heterogeneous feature magnitudes, all input variables were standardized using the Min–Max normalization method, rescaling values linearly to the interval [0, 1] prior to model training. This preprocessing eliminates biases introduced by unit differences and ensures comparability of feature importance under a unified dimensional scale. After normalization and model fitting, the stability of feature importance rankings indicates that variations in feature weights primarily stem from the structural influence of marine economic spatial indicators rather than numerical scale discrepancies. This outcome confirms the robustness and interpretability of the feature contribution analysis.

The results indicate that the coastal zone economy serves as the core driver of spatial differentiation in China’s marine economy. This dominance arises from the concentration of port clusters, advanced manufacturing, and marine technological innovation along major coastal gateways, forming high-density industrial belts characterized by strong economic concentration and spatial spillover effects. In contrast, the marine area economy, though endowed with strategic resources such as oil and gas, demonstrates relatively low spatial complexity and limited industrial diversification due to the insufficient penetration of technology-intensive industries. Meanwhile, the island economy shows the weakest contribution, constrained by limited resource endowment and a predominantly primary industrial structure, which restricts its capacity to form large-scale economic units and reduces its overall spatial influence (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Weighted Fitting Results of the Random Forest Model.

According to the importance weights obtained from the random forest regression model (see Figure 12), the influencing factors of China’s marine economic geographic space can be ranked in the following order of importance: coastal zone economy > marine area economy > island economy. Among them, the coastal zone economy exerts the strongest impact on the spatial distribution of the marine economy, with an importance weight of 83.0670, which is substantially higher than that of the marine area economy (9.5150) and the island economy (7.4180).

Figure 12.

Distribution of Random Forest Feature Weights.

This result demonstrates that the coastal zone economy is the dominant factor shaping the spatial configuration of China’s marine economic geography. The primary reason lies in the concentration of major economic cores within coastal regions such as the Bohai Rim, Yangtze River Delta, and Pearl River Delta, where diverse industrial clusters have formed along the coastline, resulting in higher economic agglomeration intensity compared to marine and island areas.

Although the marine area economy benefits from abundant offshore oil and gas resources, its industrial structure remains relatively homogeneous, which constrains the spatial expansion and diversification of marine economic activities. Meanwhile, the island economy, despite China’s large number of islands, contributes less to overall spatial differentiation due to their small size, limited resources, and a predominantly primary industrial structure centered on fisheries, tourism, and small-scale port industries. Consequently, its spatial weight and influence on the marine economic geography are minor.

6. Research Results

By applying AI technology and multi-source data fusion methods, this study systematically analyzed the spatial distribution characteristics and spatial differentiation mechanisms of China’s marine economic geography from multiple analytical perspectives. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The spatial differentiation of China’s coastal marine economy exhibits a composite pattern characterized by gradient agglomeration, multi-core linkage, and land–sea coordination. This configuration is jointly driven by resource endowment, locational conditions, and policy orientation.

(2) Based on the analysis of the global Moran’s I index, China’s marine economic geographic space demonstrates pronounced spatial heterogeneity and a clear gradient pattern, showing an overall trend of “hot in the south, cold in the north, strong in the east, and weak in the west”.

(3) Significant differences exist in the economic activities and types across different buffer zones of the coastal zone, island, and marine area economies. Regions with broader buffer coverage exhibit higher levels of economic activity. A three-tier spatial structure is observed: nearshore resource utilization in the coastal zone, mid-range industrial upgrading in the island economy, and offshore strategic expansion in the marine economy.

(4) In the overall spatial capability evaluation, the coastal zone economy presents a distinct north–south differentiation and hierarchical gradient, primarily influenced by locational advantages, resource endowments, and policy guidance.

(5) The effects of influencing factors vary significantly across indicator layers. Among them, social environment, land–sea resources, and economic value exert the most substantial impacts on the spatial distribution of China’s marine economic geography.

(6) According to the random forest importance analysis, the ranking of the indicator layers in terms of their contribution to spatial differentiation is: coastal zone economy > marine area economy > island economy. The coastal zone economy is identified as the dominant factor shaping the spatial structure of China’s marine economy, while the island and marine area economies play relatively minor roles in influencing the overall spatial configuration.

7. Policy Recommendations

Based on the preceding spatial analysis and empirical findings, this study proposes a set of actionable and internationally comparable policy recommendations for the spatial optimization of China’s marine economy. Drawing upon domestic experiences and international marine spatial governance frameworks, the proposed policies emphasize five dimensions—spatial layout optimization, graded buffer zone management, regional coordination, factor regulation, and policy prioritization adjustment. Unlike previous studies that merely generalized results from empirical analyses, this research further integrates comparative insights from the European Union, the United States, and Japan, whose mature marine spatial planning systems provide valuable references for China. Under these international frameworks, the proposed strategies aim to explore feasible pathways for optimizing China’s marine economic spatial structure, enhancing cross-regional coordination, and strengthening adaptive and sustainable marine governance.

7.1. Optimize the Spatial Layout of the Marine Economy