1. Introduction

In the context of global cooperation on climate change, the relationship between trade development and environmental protection has become a focus for major economies and international organizations. Green trade has become a central topic of discussion [

1]. China is not only the largest developing economy but also a key player in the global chain. During the process of advancing high-quality development and building a unified national market, regional industrial chains are continuously being deepened and restructured. International trade plays important roles in optimizing resource allocation and industrial collaboration and narrowing regional disparities. Moreover, provinces have significant differences in terms of resource endowments, industrial structure, energy intensity, and environmental governance capacity. Spatial separation between production and consumption means that while interprovincial trade promotes economic growth, it also reshapes the distribution of regional pollutant emissions [

2]. Some provinces meet consumption demands through external inputs, whereas the associated pollution emissions from products are concentrated in production-oriented regions. Thus, the environmental pressure between provinces should be redistributed [

3].

In recent decades, supply chain globalization has focused on efficiency and cost reduction, offering both challenges and opportunities for Chinese industries. Driven by the continuous expansion of the domestic market and rapid improvements in transportation and logistics systems, the flow of products and factors between provinces has significantly increased. Provinces have continuously adjusted their industrial structures based on comparative advantages and development positioning, accelerating the evolution of regional division [

4]. With industrial structural adjustments, production activities in some regions have increasingly shifted to provinces with more suitable factor endowments, whereas consumption and service demands are highly concentrated in economically active areas. This leads to further spatial decoupling between production, supply, and consumption [

5]. This interprovincial production and consumption structure leads to a large amount of air pollution emissions associated with final demand in the flow of products [

1]. In response, international organizations have continuously introduced policies and regulations, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, to achieve the goal of preventing and controlling atmospheric pollution. However, differing national emission reduction targets have led to regional discrepancies in environmental regulations. These discrepancies may also facilitate the cross-regional transfer of polluting industries and the intensification of trade-embodied atmospheric pollution [

3]. To address the environmental and social issues stemming from trade-embodied pollution, it is imperative to elucidate the patterns of pollution transfer in interprovincial trade and investigate how industrial restructuring, transfer, and environmental regulations affect trade-embodied atmospheric pollution. This will enable us to propose tailored recommendations for its governance and promote more sustainable development pathways.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

Research on trade-embodied air pollution has focused primarily on the measurement and impact assessment of carbon emissions in international and interprovincial trade [

3]. As research progresses, the governance of trade-embodied atmospheric pollution has emerged as a new hotspot in environmental governance studies, with numerous studies examining the influencing factors and pathways of trade-embodied air pollutants [

1].

Research reveals a close relationship between refined interregional industrial division, diverse industrial distributions, and trade-embodied atmospheric pollution [

6]. First, significant disparities exist among regions in terms of resource endowments and economic development. To optimize the allocation of resources among industries within each region, continuous efforts are being made in industrial division and structural adjustment across various regions [

7]. This refinement, achieved through the rationalization and upgrading of industrial structures [

8,

9], increases interregional trade and facilitates cross-regional pollution transfer. In addition, region-specific environmental policies create cost variations, compelling high-pollution, high-energy industries to concentrate in underdeveloped areas rather than in developed provinces [

10]. To foster local industrial transformation, many governments and enterprises in developed regions shift traditional industries to neighboring or underdeveloped areas, causing cross-regional pollution transfer [

11,

12]. Based on the above analysis, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1. Industrial structural adjustments increase trade-embodied air pollution.

With the continued advancement of economic globalization and the international division of labor, global industrial structural adjustments have sparked a new wave of industry relocation [

13]. Empirical studies have shown that, owing to regional resource misallocation, energy-intensive and heavily polluting industries are often the first to be relocated, resulting in the spatial transfer of embodied pollution [

14,

15]. However, the green production model and strict environmental regulations have shifted the focus from scale to innovation and structural effects, promoting high-quality industrial transfers and partially mitigating trade-embodied pollution [

3]. As industries relocate, regional innovation capacity improves, and entry barriers rise, leading to the more proactive coupling of innovative technologies with environmental quality and ultimately reducing the embodied air pollution in trade. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2. Industrial transfer plays a partial mediating role between industrial structure adjustment and trade-implied air pollution.

Scholars have focused primarily on how industrial structural adjustments impact environmental quality. However, recent studies suggest that environmental protection measures can also influence industrial structure, with strict environmental regulations potentially achieving a win–win outcome for both environmental protection and structural transformation [

16]. As one of the important means for managing environmental pollution, environmental regulation policies can effectively address the negative externalities of economic activities and reduce pollution emissions [

17,

18]. However, the implementation of these policies also presents challenges. The policies increase the cost of pollution control for businesses, prompting polluting industries to relocate to regions with less stringent environmental regulations [

19,

20]. Specifically, environmental regulation exhibits spatial heterogeneity. There are significant differences in the intensity of environmental regulations across different countries and even within regions of the same country. Faced with varying levels of environmental regulation, companies weigh the options of reducing emissions onsite or relocating to regions with weaker regulations to reduce costs [

21,

22]. Pollution-intensive firms will relocate across regions when the cost of relocation is lower than the cost of onsite emission reduction [

15,

23]. Domestic pollution transfer does not reduce the total pollution level; it merely alters its spatial distribution. Companies that relocate to areas with weaker environmental regulations may emit more [

19]. Therefore, through the coordinated implementation of environmental regulation policies across regions, the joint prevention and control of trade-embodied pollution can be achieved. On this basis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3. Environmental regulation moderates the relationship between industrial structural adjustments and trade-embodied air pollution.

In addition to investigating industrial structural adjustments, industrial transfer, and environmental regulation, scholars have explored the factors influencing embodied pollution from various perspectives, such as economic development, urbanization, technological progress, energy structure, and total factor productivity [

11,

24]. For example, countries or regions with high economic development levels may transfer pollution by shifting demand toward cleaner products [

25]. In highly urbanized regions, industries are heavily concentrated, and businesses are likely to upgrade locally, reducing both transportation costs and trade-embodied pollution [

26]. Technological progress decreases pollution emissions by improving production efficiency [

27]. Energy structure adjustment reduces pollution by lowering the dependence on fossil fuels, such as coal [

20]. Total factor productivity depends in part on technology transfer and international cooperation, which allows businesses to adopt advanced environmental technologies and management practices from other countries, thereby improving efficiency and environmental friendliness and reducing trade-embodied air pollution [

19].

In 2015, China responded to international calls by proposing comprehensive reforms, one key measure being the shift in regional and corporate development models toward high-quality, high-tech industries [

28]. To assess the impact of industrial structural adjustments before and after the implementation of these reforms, most studies use the difference-in-differences (DID) model. This model mitigates the impact of confounding factors by applying two differences, but its reliability depends heavily on the parallel trend assumption. Traditional DID models may fail to verify this assumption with limited panel data, potentially compromising the validity of the results [

29]. To address this, Ma et al. [

30] introduced the reweighted synthetic difference-in-differences (SDID) method, which balances the treatment and control groups using weighted data in three-period panel studies. In this approach, the changes in outcome variables are compared between the treated and the untreated groups to measure the policy effects, which increases the credibility of the results when the parallel trend assumption is not fully satisfied [

31]. Moreover, in the generalized DID method, the time and treatment dimensions are combined to eliminate fixed effects from time-invariant individual and treatment characteristics. A comparison of pre- and postpolicy differences provides a more accurate estimate of policy effects [

23]. In the generalized DID and SDID methods used in this study, the parallel trend assumption is eliminated, and individual policy group dummies are replaced with a continuous variable to reflect variations in treatment intensity [

32,

33]. Building on this, we further embedded mediation and moderation effect models into the causal analysis framework. The mediation effect model is used to decompose the total effect identified by DID/SDID, exploring how industrial structure adjustment influences trade-embodied pollution through industrial transfer. A moderation effect model is employed to examine the heterogeneous effects of environmental regulation, revealing how it alters the intensity of the impact of structural adjustment on trade-embodied pollution. This combined approach of causal effect identification and mechanism decomposition is still relatively lacking in the literature. This enables this study to identify the net effect of industrial structure adjustment and explain the underlying transmission paths and conditional constraints [

21].

Given the above issues, we use the MRIO model to estimate the emissions of nine pollutants from both the production and consumption sides for the years 2012, 2015, and 2017. Then, the generalized DID and SDID models are applied to analyze the impact of industrial structure adjustments on trade-embodied air pollution. We also employ mediation and moderation effect models to explore the pathways of industrial transfer and environmental regulation. The main contributions of this study are as follows. (1) We reconstruct the mapping relationship between China’s multiscale emission inventory (MEIC) and input–output sectors and use the MRIO model to calculate the emissions of multiple pollutants from both the production and consumption sides. This approach supports a comprehensive analysis of the interprovincial trade patterns of trade-embodied air pollution. (2) We estimate pollution emissions for 2012, 2015, and 2017, providing an in-depth analysis of the spatiotemporal characteristics and trends of changes in pollution due to policy implementation. This study provides a solid foundation for the formulation of effective long-term environmental policies and strategies. (3) By combining the generalized DID and SDID methods, we investigate the relationship between industrial structure adjustments and trade-embodied air pollution, further revealing the mechanisms of industrial transfer and environmental regulation. This clarifies the available pathways for industrial structural adjustments.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Air Pollution Embodied in Trade

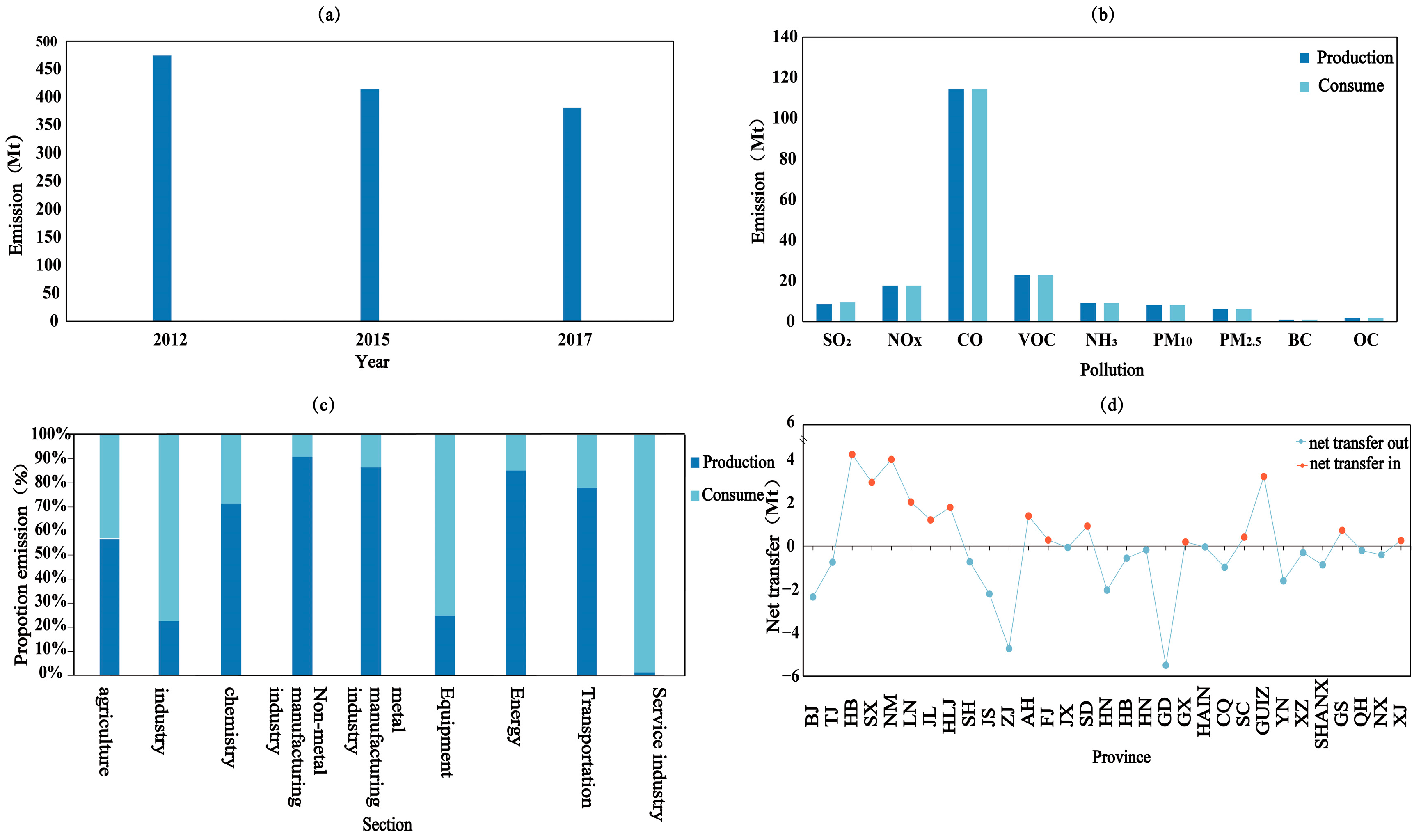

To analyze the air pollution embodied in trade, MATLAB R2019a was used to calculate the transfer amount. The trade-embodied air pollution emissions and transfer patterns are illustrated in

Figure 1, which presents the changes in trade-embodied pollutants over time, by pollutant type, by sector, and in terms of net transfer. The chart in

Figure 1a shows the time series of total emissions for each year. The chart in

Figure 1b displays the total emissions of different pollutants from both the production and consumption sides in all sectors across 31 provinces in China in 2017. The chart in

Figure 1c illustrates the production- and consumption-side emissions by sector in 2017, using data from nine sectors across 31 provinces. The line chart in

Figure 1d presents the net transfer of pollutants across provinces, which is calculated using MATLAB R2019a.

First, from the perspective of the temporal trend, the total pollutant emissions across Chinese provinces tended to decrease from 2012 to 2017. Specifically, total emissions decreased from 474 Mt in 2012 to 415 Mt in 2015 and further to 381 Mt in 2017. This decline indicates a reduction in pollution over the years. This can be attributed to increased environmental awareness among residents, technological advancements by enterprises, the application of pollution control facilities, industrial structure adjustments, and the effective implementation of policies and regulations.

Second, from the perspective of pollutant types, overall, the differences between the production and consumption sides are relatively small. Among the nine pollutants, carbon monoxide (CO) has the highest level of trade-embodied pollution, with total emissions of 229.12 Mt, accounting for 60% of the total pollutant emissions. This highlights CO as a key target for trade-embodied air pollution control. The second most significant pollutants are volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), with emissions of 46.01 Mt and 35.51 Mt, respectively. As both VOCs and NOx are precursors to PM2.5 and ozone (O3), they have a critical impact on alleviating air pollution. Therefore, regions across China need to implement more decisive and coordinated emission reduction strategies for the precise control of VOCs and NOx. BC is the least emitted pollutant among the nine pollutants, with a total emission of 1.93 Mt, accounting for 0.5% of the total pollutant emissions.

From the perspective of sectors, the production side primarily generates trade-embodied pollution in industries such as manufacturing, energy, transportation, and metal manufacturing. The energy sector is particularly significant, accounting for more than 42.45%. This indicates the need to strengthen environmental protection and pollution control in the energy sector. By adopting clean energy in production processes and enhancing energy utilization efficiency, we can mitigate the adverse environmental impacts of the energy industry. On the consumption side, pollution is concentrated mainly in the industrial, equipment, and service sectors. The significant differences in sectoral shares between the production and consumption sides highlight the imbalance in trade-embodied air pollution. Therefore, targeted control measures should be implemented according to the specific characteristics and factors influencing each sector to achieve balanced and sustainable development.

Finally, regarding interregional transfers, developed regions, such as Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Jiangsu, are primarily net exporters of trade-embodied pollution. Guangdong has the greatest net export volume. This suggests that developed regions tend to import resource-intensive and high-pollution products while exporting high-tech, low-pollution products. Therefore, they transfer embodied air pollution to other regions [

38]. In contrast, underdeveloped regions, such as Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Ningxia, and Xinjiang, are often net importers of trade-embodied pollution. Hebei has the largest net import volume. For example, Hebei absorbs high-pollution, high-energy-consuming industries transferred from neighboring Beijing and Tianjin. Conversely, owing to its own resource endowments and industrial structure differences, Hebei’s industrial grade is relatively low, and the rationality of its industrial structure is poor [

39]. Pollution-exporting regions should focus on long-term goals. They should emphasize scientific industrial structural adjustments to achieve innovation-driven growth and industrial upgrades locally rather than simply relocating high-pollution industries. For pollution-importing regions, enhancing technological capabilities and innovation, strictly enforcing environmental standards, and rigorously filtering and controlling new projects are essential.

4.2. Regression Results

In accordance with Equation (11), we combine data from the years 2012, 2015, and 2017 to comprehensively identify the impact of industrial structural adjustment policies on the transfer of trade-embodied pollution. The empirical results are presented in

Table 2.

The table above shows that the coefficient of the DID interaction term is significantly positive, indicating that regional industrial structure adjustment tends to increase trade-embodied air pollution. Some regions adjust their industrial layout through industrial upgrading and transfer; however, the types of products consumed do not change significantly. This leads to a separation between production and consumption, thereby causing the issue of embodied pollution in trade: pollution is indirectly transferred to other regions through trade channels. These findings support Hypothesis 1. This further suggests that the positive effects of industrial structure adjustment on reducing embodied pollution have not yet fully materialized; instead, such adjustment has exacerbated embodied pollution. Therefore, attention should be given to the direction of industrial structure adjustment, with a focus on local technological innovation and industrial upgrading to reduce the impact of industrial structure adjustments on trade-embodied pollution.

4.3. Parallel Trend Test and Robustness Test

4.3.1. Parallel Trend Test

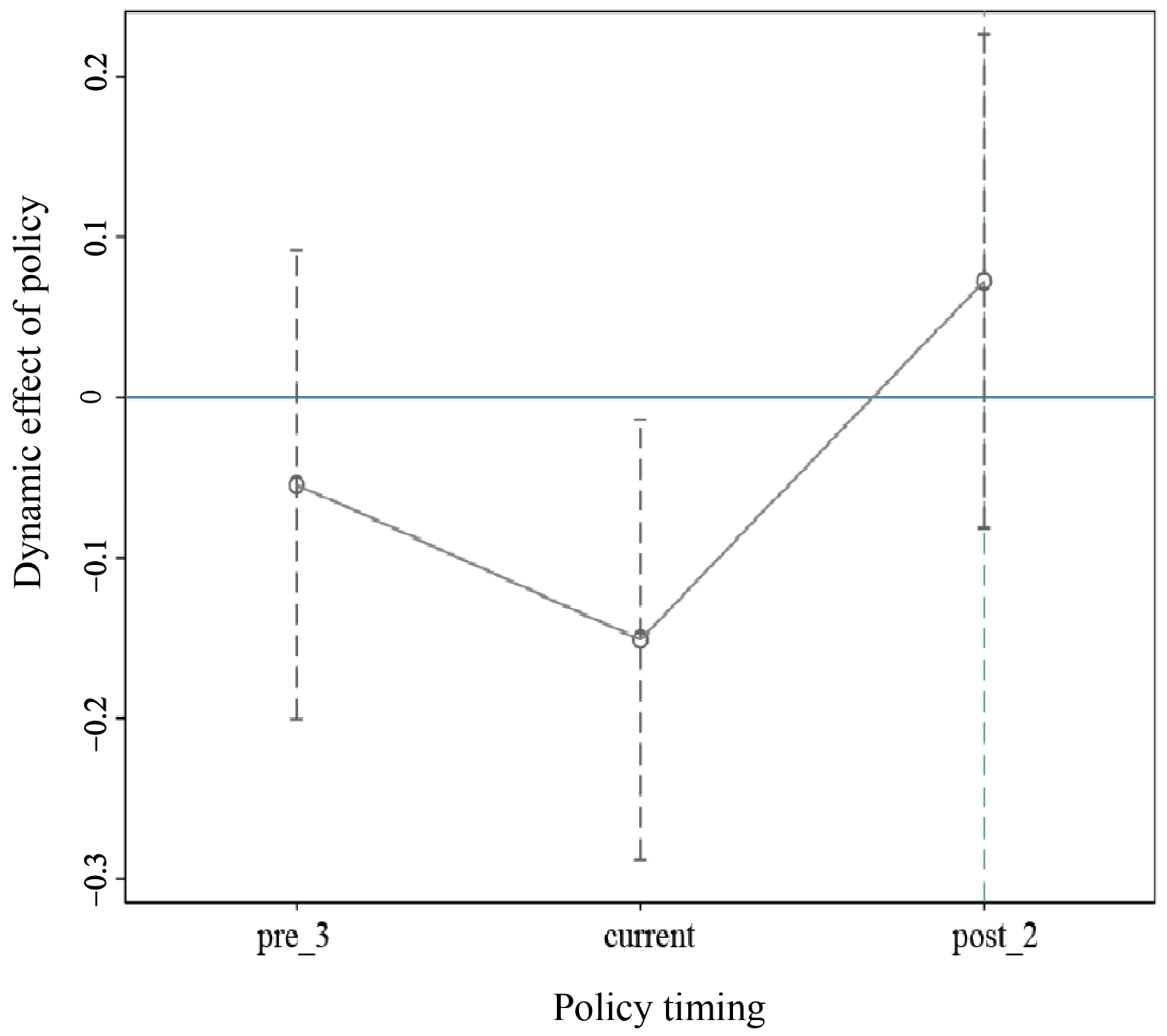

The baseline regression results may not reliably indicate whether the industrial structure adjustment policy influences trade-embodied air pollution, and the mechanism could be overestimated. To ensure the reliability of the estimated results, the event study method proposed by Jacobson et al. [

40] is used to conduct a parallel trend test (see

Figure 2). This method can be expressed as follows:

where

is the year dummy variable, which takes the values of 2012 and 2017.

is the key focus of this study, as it helps identify the dynamic relationship between industrial structure adjustment and trade-embodied carbon air pollution. The remaining terms are as previously defined.

Considering the data scarcity before and after the policy implementation, we exclude the missing years and select data from three years before the policy implementation (2012) and two years after the policy implementation (2017). The results indicate that the common efficiency estimates of trade-embodied air pollution for each period before the policy implementation are not significant. This suggests that before the policy implementation, there were no significant differences in trade-embodied air pollution. Therefore, the research sample passes the parallel trend test. Additionally, we employ dynamic tests to verify the parallel trend, which is also passed. For the sake of brevity, the results are not presented in the main text.

4.3.2. Robustness Tests

To enhance reliability, we conduct robustness checks in the following aspects. First, based on relevant studies on economic regionalization, the 31 provinces of China are divided into seven major regions (corresponding to Model 1). Second, additional control variables are introduced, including the number of patents (R&D) to reflect the impact of regional technological differences on trade-embodied pollution (corresponding to Model 2). Third, given that the sample sizes of the treatment and control groups are small, there may be outliers that interfere with the significance of the data. In the above analysis, the impact of outliers was considered, and truncation of extreme values was applied. In the robustness analysis, no truncation of extreme values is performed, and the SDID method is used for regression (corresponding to Model 3). The results of the three robustness checks are shown in

Table 3, and the findings remain robust. In conclusion, industrial structure adjustment is a positive driver of trade-embodied air pollution.

4.3.3. Placebo Test

Another potential threat is that the differences in trade-induced pollution might be driven by market changes rather than policy interventions. To verify the accuracy of the regression results, we shift the policy implementation point by year, setting 2013 as the policy onset, and conduct a placebo test (corresponding to Model 1). The regression results show that when the policy point is shifted to 2013, the results are significant, which confirms that the previous regression results are indeed attributable to the policy implementation. A robustness check is conducted by replacing the variables (corresponding to Model 2), and the results are significant. Additionally, given the limitation of having only three periods of data, the traditional approach of shifting the policy year forward has certain constraints. To further strengthen the robustness of our identification, we therefore adopt a stratified placebo (corresponding to Model 3) [

41]. Specifically, while keeping regional location, economic development level, and industrial structure characteristics unchanged, we randomly reassign “treated” provinces within each stratum and repeatedly re-estimate the SDID model to generate an empirical distribution of pseudo-policy effects. The results show that most pseudo-treatment coefficients are statistically insignificant and symmetrically centered around zero, whereas the true policy effect lies well outside this distribution. This indicates that the estimated policy impact is unlikely to be driven by random fluctuations or model artifacts, thereby reinforcing the credibility of our findings. The results are shown in

Table 4.

4.4. Analysis of the Mediating Effect of Industrial Transfer

To further explore whether industrial structure adjustment can indirectly affect trade-embodied pollution through industrial transfer, a mediation effect model is established to verify whether industrial transfer serves as a mediating factor. The results are presented in

Table 5. First, the impact of industrial structure adjustment on trade-embodied pollution is examined (corresponding to Model 1). Second, the effect of industrial transfer on trade-embodied pollution is analyzed (corresponding to Model 2). Finally, the combined impact of industrial structure adjustment and industrial transfer on trade-embodied pollution is assessed (corresponding to Model 3).

Column (1) of

Table 5 shows that the regression result of

DID is significant at the 5% level, with a coefficient of 0.0952, indicating that industrial structure adjustment has a significant positive effect on trade-related pollution. Column (2) shows that

DID is significantly negative at the 5% significance level, indicating that industrial structure adjustment has a negative effect on industrial transfer. This may be due to the existence of industrial agglomeration effects in the region. Industrial structure adjustment can induce dynamic adjustment mechanisms in high-polluting industries to some extent. This encourages industries to focus on local technological and industrial upgrading rather than transferring to other regions [

42]. Column (3) shows that industrial transfer serves as a partial mediator in the relationship between structural adjustment and trade-embodied pollution. Under the current sample, the mediation effect is negative, indicating that structural adjustment suppresses industrial transfer and thereby amplifies trade-embodied pollution during the adjustment phase [

43]. In columns (2) and (3) of

Table 5, both the

DID and

TRF results are significant, indicating the presence of a mediating effect. Furthermore, the sign of

is consistent with that of

, which suggests the existence of a partial mediation effect. Hypothesis 2 is thus confirmed.

The negative significance of the industrial transfer can be explained theoretically by the following analysis. Through industrial transfer, some enterprises are relocated to underdeveloped regions through industrial structure adjustment. The receiving local governments can obtain more favorable conditions provided by the state. Additionally, owing to the performance assessments of local officials, there is high enthusiasm for supporting technology diffusion effects, which can reduce trade-related pollution [

38]. Furthermore, underdeveloped regions have adopted the concepts of ecological priority and circular development, increased industrial entry thresholds and strengthened green supply chain construction. These measures can effectively prevent the relocation of high-pollution industries. As a result, industrial transfer not only prevents the pollution shifting effect of the beggar-thy-neighbor strategy but can also drive improvements in the environmental quality of surrounding areas [

44]. We further analyzed the data from three perspectives: micro, meso, and macro. From a micro perspective, industrial transfer promotes the expansion of domestic and international markets, where enterprises innovate to capture market shares, thus forming competitive advantages. From a meso perspective, industrial transfer inevitably involves interindustry replacement, with traditional industries undergoing advanced transformation and emerging and high-tech industries rapidly becoming new driving forces. This drives increased social capital and accelerates investments in research and development and the output of technological innovation. From a macro perspective, to enhance industrial competitiveness and promote industrial transfer, the government encourages independent innovation in the formulation, improvement, and implementation of relevant industrial policies while also fostering a policy environment for collaborative innovation and increasing fiscal spending on R&D. This, in turn, increases the demand for technological innovation capabilities [

45]. Overall, under the mechanism of promoting technological progress and industrial upgrading, industrial transfer is more likely to have a net positive effect on regional environmental quality. These findings contradict the findings of existing research, which suggest that industrial structure adjustment may lead to the relocation of high-pollution industries to nearby regions and thereby exacerbate trade-related atmospheric pollution [

46]. These results indicate that environmental protection and economic development are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In fact, achieving a win–win outcome for both the economy and the environment is possible.

4.5. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Environmental Regulation

To explore the mechanism through which environmental regulation affects the relationship between industrial structure adjustment and trade-related pollution, we construct a moderating effect model. According to the three-step approach for testing moderating effects, the first step of the test yields results that are consistent with those in Column (1) in

Table 5. The results of the subsequent steps are presented in

Table 6. First, we conduct a main effect analysis of the impact of industrial structure adjustment on trade-related pollution (Model 1). Second, we analyze the moderating effect of environmental regulation on trade-related pollution (Model 2). The regression results are displayed in the following table (

Table 6).

As shown in the table above, the interaction term between environmental regulation and industrial structure adjustment (M) is significantly positive. These findings indicate that environmental regulation may temporarily play a significant positive moderating role in the process of industrial structure adjustment. This suggests that during the structural adjustment phase, the stronger the environmental regulation is, the more likely the industrial structure is to adjust, and the greater the contribution of industrial structure adjustment to trade-related atmospheric pollution. Hypothesis 3 is thus validated. The findings indicate that China’s industrial structure adjustment is heavily influenced by industrial policies and interventions. Local governments are subject to mandatory requirements from the central government, and enterprises are constrained by pressures from local governments. This series of passive transmissions results in a lack of internal incentives for structural adjustments in enterprises. In this context, environmental regulation plays a constraining role. In China’s current stage, the country has set different emission reduction targets for different provinces, leading to variations in regional environmental regulations. The differences in the intensity of environmental regulations across provinces can promote industrial structure adjustments, but this may also lead to the transfer of polluting industries across regions. During the adjustment process, exporting regions consume products from importing regions, leading to the transfer of pollution through interregional trade. These findings indicate that environmental regulations indeed trigger pollution transfer effects. When structural adjustment leads to the reallocation of production factors, industry chain restructuring, and the entry and exit of firms, stringent regulations prompt firms to accelerate investments in clean technologies, equipment upgrades, and compliance improvements. These activities often involve additional energy consumption, emissions from the reform process, and disturbances in the short term, thereby amplifying pollution pressure in the early stages of structural adjustment [

47]. Simultaneously, strict environmental regulations accelerate the elimination of outdated capacity and increase the regulatory intensity of pollution emissions. This makes the crowding-out effect of previously pollution-intensive sectors more apparent during the adjustment process, thereby reinforcing the short-term correlation between structural adjustment and pollution fluctuations. In other words, the positive moderating effect of environmental regulation reflects the fact that, in the early stages of structural adjustment, strict regulation accelerates the adjustment process. This amplifies the temporary pollution pressure caused by the adjustment rather than leading to a long-term increase in pollution levels [

17].

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

Based on an MRIO model and emission inventory data, we quantitatively measure trade-induced atmospheric pollution and analyze its influencing factors to address the environmental inequity caused by pollution transfer. The main conclusions of this study are as follows.

- (1)

First, from a temporal perspective, the total pollutant emissions across China’s provinces show an overall decreasing trend. Second, in terms of pollutant types, CO accounts for the greatest proportion of trade-induced pollution, followed by VOCs and NOx. From an industrial perspective, pollution transfers on the production side are concentrated primarily in industries such as manufacturing, energy, transportation, and metal production, whereas those on the consumption side are concentrated mainly in industries such as manufacturing, equipment, and services. With respect to the transfer situation, developed regions, such as Beijing and Tianjin, are generally net exporters of trade-induced pollution, whereas provinces such as Hebei and Shanxi are mostly net importers.

- (2)

Based on the model fitting results, regional industrial structure adjustments lead to an increase in trade-induced atmospheric pollution. Following the implementation of industrial structure adjustment policies, the amount of trade-induced atmospheric pollution increases in parallel. Other factors, such as the urbanization level, energy structure, and total factor productivity, are not significant. The reliability of these results is confirmed through parallel trend tests, robustness checks, and placebo tests.

- (3)

According to the mediation and moderation effect models, industrial transfer plays a partial mediating role. Industrial structure adjustment positively affects interregional trade-induced pollution through industrial transfer, meaning that industrial structure adjustment reduces trade-induced pollution via industrial transfer. Environmental regulation may temporarily play a positive moderating role in the relationship between industrial structure adjustment and trade-induced atmospheric pollution.

5.2. Policy Implications

Based on the above analysis, three types of policy recommendations can be made, namely, promoting joint prevention and control, improving the quality of industrial structure adjustment, and strengthening regional environmental regulation, to reduce the negative impacts of trade-induced pollution.

- (1)

Focus on key industries and pollutants to promote joint prevention and control.

The government can use big data and scientific assessment tools to analyze the emission status of various industries and accurately identify the key industries and pollutants that have the most significant impact on regional environmental quality. This approach will enable a dual focus on both industries and pollutants. On this basis, differentiated and refined prevention and control strategies should be developed for each region. Local governments should integrate resources and efforts from multiple sectors to jointly design and implement pollution control measures, including information sharing, collaborative monitoring, joint law enforcement, and establishing cross-regional joint prevention and control mechanisms. This approach will help break through administrative boundaries, enhance regional cooperation, and more effectively control pollution emissions transmitted through interprovincial trade.

- (2)

Improving the quality of industrial structure adjustment and preventing ineffective transfer.

At the current critical stage of industrial structure adjustment, the core task should be a focus on improving quality. By relying on technological innovation, the upgrading and optimization of the industrial structure should be accelerated to overcome the constraints of an unreasonable industrial structure. On the one hand, by increasing R&D investment and promoting technological innovation, enterprises should be supported in upgrading their equipment and digital transformation. In addition, the development of high-value-added, low-emission industries should be accelerated, thereby reducing the inherent pollution intensity per unit of output at the source. On the other hand, it is necessary to optimize the spatial layout of industries and regional divisions by scientifically planning industrial parks, strengthening cross-regional industrial coordination, and connecting upstream and downstream industries to achieve efficient resource utilization. These measures will reduce pollution spillovers caused by blind or inefficient transfers and prevent economic growth and industrial adjustments from simultaneously exacerbating environmental pressures.

- (3)

Enhancing the level of industrial transfer and optimizing environmental regulation.

The government should simultaneously focus on industrial transfer pathways and environmental regulation design. First, by setting entry thresholds and emission intensity constraints, the government should guide industrial transfer toward more technologically advanced, energy-efficient, and low-emission industries and sectors. In addition, simple relocation of high-pollution industries should be avoided, and industrial transfer should be turned into a pollution reduction channel. Second, while the intensity of environmental regulation should steadily increase, the government should strengthen coordination and support between regions. They should avoid causing firms to migrate in response to regulatory discrepancies or to escape tightening regulations, which could lead to short-term emission shocks. This approach will help weaken the amplifying effect of environmental regulations on trade-embodied pollution.