Abstract

An assessment of the effectiveness of measures undertaken to make urban road transport more sustainable requires appropriate tools to evaluate the impact of transport on air quality. For this purpose, emission inventories for the road network are prepared using suitable models. In cities without a calibrated travel demand model, the main challenge is obtaining data on traffic parameters. With this in mind, this study proposes a rapid model that enables the estimation of traffic parameters such as average speed, traffic volume, and the percentage share of individual vehicle categories. The proposed method is based on traffic measurements and the aggregation of different road classes into four cumulative categories. A comparison of results obtained from the simplified model and the travel demand model indicates satisfactory accuracy of the estimated parameters, confirming the usefulness of the proposed rapid model in emission inventory calculations. The performed calculations for PM2.5 and NOx show that using traffic parameters derived from the rapid model, instead of those from a travel demand model, may result in an error of 15% in total emission for the traffic network.

1. Introduction

Air quality in urban areas is determined by a number of factors, among which transport-related air pollutants often constitute a key determinant. Implementing effective measures to ensure sustainable urban development requires information on the contribution of individual emission sources. Such information is provided by analyses based on current air pollutant concentration data recorded by monitoring systems or predicted using air pollution forecast models. Model-based data also enable the assessment of the effectiveness of planned emission-reduction scenarios and the selection of optimal strategies within real-world constraints [1,2].

Air quality forecasting models require a wide range of input information. To determine emission generated by road traffic, one of two approaches is used: a top-down approach or a bottom-up data modelling approach. In the top-down approach, the starting point is an aggregated value for a given area, such as the total annual emission of a given pollutant generated by road transport, estimated for a city based on statistical data. The data used may include aggregated parameters such as fuel consumption, number of registered vehicles, mean traffic speed, mean travelled distances, or vehicle fleet structure. In this approach, the total emission is then disaggregated and spatially allocated to a gridded city domain using spatial surrogates such as road density, road classes, population, traffic counts, or land use indicators [3].

The bottom-up approach, on the other hand, is based on locally calculated emission for individual road links using emission factors for specific vehicle categories. This approach is feasible when local traffic data are available or at least a traffic simulation model exists. It enables high spatial and temporal resolution of emission inventories, which is essential for assessing the environmental impacts of traffic on a local scale. The bottom-up approach for estimation of road transport emission is widely applied in the literature—for example, Policarpo et al. [4] applied it to analyse emission changes in the Fortaleza Metropolitan Area; Singh et al. [5] inventoried road emissions for Delhi; Maes et al. [6] used a weighted-factor bottom-up approach for the Florianópolis Metropolitan Area; Jiang et al. [7] evaluated traffic control strategies in the Xiaoshan District using a hyper-fine-resolution model; and Pla et al. [8] estimated traffic-related emission in Valencia.

Implementation of the bottom-up approach, in addition to traffic data, requires the application of an emission model. Emission models provide emission factors for pollutants and vehicle categories, expressed as the mass of pollutant emitted per distance travelled, time, or fuel consumed. Models described in the literature may be classified as static-type and dynamic-type emission models [9].

The total emission of pollutants from road traffic on a given road link is determined by traffic flow rate, current traffic conditions (e.g., level of service, queue lengths), traffic dynamics (frequency of acceleration, deceleration, stop-and-go), and fleet composition. For heavy-duty vehicles and buses, load and occupancy ratios and road grade are also important factors. Additional excess emission occur under cold-start conditions, particularly relevant in urban environments with short-trip passenger car usage. For PMx emission, in addition to exhaust emission, non-exhaust emission from tyre and brake wear, road pavement wear, and resuspension must also be considered. Numerous emission models exist that allow analyses using the bottom-up approach [10,11,12]. Static-type models require only basic aggregated traffic data such as average speed, traffic conditions (urban peak, urban off-peak), and road type. Dynamic-type models require detailed information on instantaneous vehicle speed, acceleration, and driving modes. Consequently, static-type models are computationally more efficient and suitable when computing resources or detailed data are limited. Both model types are used in research: for example, the MOBILE model was applied in a bottom-up inventory for New Haven [13], while COPERT has been used for CO2 emission assessments in Ireland [14] and for emission inventories in Foshan [15]. Ježek et al. [1] applied the static-type EMISENS model for scenario evaluation in Maribor; EMBEV was used to build a high-resolution inventory for Shenzhen [16]. The dynamic-type MOVES model has been applied to analyse emission reduction policies in Hangzhou [17], to develop an emission inventory for Toronto [11], and to estimate traffic related CO2 emission in Beijing [18].

To achieve the expected accuracy of emission estimation and air quality forecasts, a suitable macroscopic traffic description is needed for each road link. When using static-type models, which define emission factors as a function of average speed, three parameters are essential for emission estimation: traffic average speed, traffic volume, and the share of individual vehicle categories. Traffic volume and the share of individual vehicle categories vary depending on the time of day and type of day (workday vs. non-workday). Under under-saturated conditions, average speed depends on free-flow speed, traffic volume, and road capacity; under over-saturated conditions, queueing effects must also be accounted for.

Among the previously cited studies using a bottom-up approach for emission modelling at street-scale resolution, traffic volumes for individual road types in the cities were determined based on traffic monitoring [7,8,15,16], travel demand models [6,17], and existing databases [5]. In most studies using traffic monitoring data, the average vehicle speeds were also determined. In the study [7], the calculation of average speed was based on vehicle speeds recorded by the traffic control system. In studies [15,16], the average speed was determined using location data from vehicles equipped with positioning systems. Both approaches to determining average traffic speed are time-consuming and require significant computational resources.

Implementing policies for sustainable mobility in cities requires effective tools that provide the data necessary to evaluate their performance. This paper presents a rapid method for emission estimation in cities using the bottom-up approach. Road networks and road classes are obtained directly from the OpenStreetMap service [19]. The static-type COPERT model [20] is applied to estimate exhaust emission factors. The novelty of the method lies in the proposed estimation of traffic volume and traffic average speed for an urban road network represented by aggregated road categories. The estimation is based on real-world traffic measurements collected on selected road sections of different classes. The method enables emission inventory development for cities where no travel demand model is available. Results of PM2.5 and NOx emission calculations obtained using the proposed approach for a medium-sized city in Poland are compared with the results derived after applying data from the travel demand model.

2. Materials and Methods

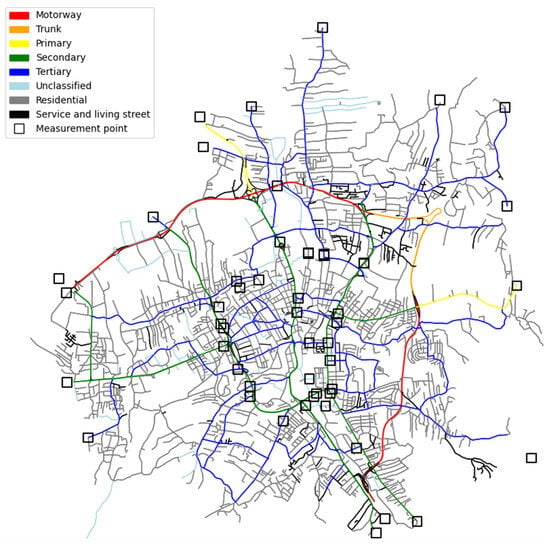

The calculations and analyses presented in this study concern traffic conditions in the city of Bielsko-Biała, located in the southern part of Poland. In this city, road transport is a significant source of emission [21]. According to the data for 2024, the annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 and NOx were 19.5 µg/m3 and 45 µg/m3, respectively [22]. The urban road network is characterised by a high diversity of functional hierarchy. According to the OpenStreetMap (OSM) classification [19], it includes roads ranging from expressways (motorway, trunk) to local and residential streets (residential, service, living street). The layout of the road network, together with the locations of the measurement points, from which data were used in the proposed method, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Road network of the city of Bielsko-Biała with the locations of measurement points.

2.1. Traffic Measurements

To estimate the average traffic volume, data on traffic flow and vehicle fleet composition for the year 2021 [23] were used, obtained from the cordon traffic survey carried out within the city. Measurements were conducted at selected monitoring points with 12 h intervals for unclassified roads and 24 h intervals for trunk, primary, secondary, and tertiary roads. The average traffic volume during the morning and afternoon peak hours for the respective road classes are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average traffic volume during morning and afternoon peak hours for individual road classes.

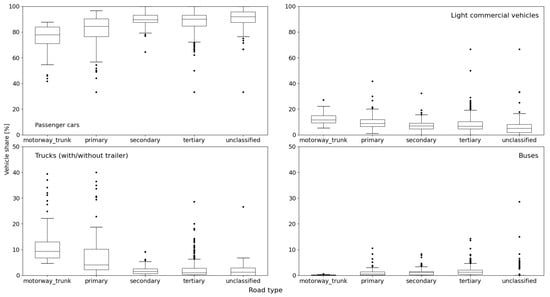

The share of individual vehicle categories in traffic for each OSM road class is presented in Figure 2. The respective segments illustrate the percentage contribution of passenger cars, light commercial vehicles, buses, and heavy-duty vehicles to the total traffic volume. Motorcycles were excluded due to their very low traffic intensity (on average 1.5 veh./h during peak hours).

Figure 2.

The share of vehicle categories in traffic for each road class. The boxes represent the interquartile range (from the first to the third quartile), the middle line indicates the median, and the whiskers show the calculated minimum (Q1 − 1.5 IQR) and maximum (Q3 + 1.5 IQR) observed values. Individual points outside the whiskers represent statistical outliers.

In the considered urban road network, the share of heavy-duty vehicles (HDVs) is highest on motorway and trunk roads, averaging 12.4%. For primary road, the share of HDVs is 7.6%. For the remaining three road classes, the average share does not exceed 2.5%. The average share of buses is lowest on motorway and trunk roads, with an average below 0.2%. Similar average shares slightly above 1% were observed for primary and unclassified roads, while the highest bus share of 1.7% occurs on tertiary roads.

Regarding light-duty vehicles (LDVs), their average share ranges from 6.7% on unclassified roads to 12.3% on motorway and trunk roads. On primary roads, the average LDV share is slightly lower at 9.9%, on tertiary roads it is 8.1%, and on secondary roads it is approximately 1% lower than tertiary.

For passenger cars, the average share is around 90% on secondary, tertiary, and unclassified roads. On primary roads, the average share does not exceed 82%, while on motorway and trunk roads, it is approximately 75%.

2.2. The Method for Traffic Parameters Computation

The rapid traffic parameter estimation method proposed in this study is based on estimating traffic volume, the share of individual vehicle categories, and traffic speed for aggregated road categories. Aggregated road categories include roads of classes defined in OSM, for which the primary emission determinant, vehicle speed, is statistically similar. Using the speed limit known for each road class as a starting point, the following aggregated categories are distinguished:

- (1)

- Category (1) including roads classified as motorway and trunk in OSM;

- (2)

- Category (2) including roads classified as primary and secondary in OSM with a speed limit of at least 70 km/h;

- (3)

- Category (3) including roads classified as primary and secondary in OSM with a speed limit below 70 km/h, as well as roads classified as tertiary;

- (4)

- Category (4) corresponding to unclassified roads in OSM.

Other road classes (residential and service roads) are omitted from the calculations, as they typically carry very low traffic volumes.

Traffic volume for a given road segment of a specific OSM class in the transport network is determined as follows:

where —average traffic volume of vehicles on the i-th aggregated road category during the j-th hour per lane, expressed in vehicles per hour, —number of traffic lanes.

The values of were directly determined based on traffic measurement results collected at monitoring points located on roads of OSM classes included in the aggregated category. For individual road segments, the traffic volume of a particular vehicle category is determined according to the following relationship:

where —average share factor of the k-th vehicle category in traffic on the i-th aggregated road category during the j-th hour. The value of the factor is determined based on the traffic measurements.

Next, the equivalent traffic volume is calculated using the following formula:

where —conversion factor for the k-th vehicle category (passenger cars—1, LDVs—1.2, trucks—3, buses—2.0).

To calculate traffic speed on road segments, the BPR2 function [24] was applied, which takes into account the free-flow speed (), traffic volume expressed in passenger car equivalents (, and the segment capacity (). It was assumed that speed is calculated separately for light vehicles (LV: passenger cars and LDVs) and heavy vehicles (HV: HDVs and buses).

The traffic speed on the i-th aggregated road category during the j-th hour is calculated as follows:

where are empirical coefficients adopted. To ensure the universality of the traffic speed estimation method, the default values described in [25,26] were used, with and , or 0.8 if .

For the respective aggregated road classes, it is proposed to adopt the capacity and free-flow speed values as given in Table 2. For road category 1, these values were adopted based on the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) guidelines [27]. For urban roads (categories 2–3), the free-flow speed values are based on the upper limit of the speed for the corresponding aggregated road category. In the case of category 4, the free-flow speed for LV vehicles was increased by 5 km/h compared to the statutory speed limit in built-up areas to better represent the expected free-flow conditions on such roads.

Table 2.

Proposed capacity and free-flow speed values for the respective aggregated road classes.

2.3. Emission Modelling

The proposed traffic parameter estimation method enables the calculation of exhaust pollutant emission for a road network using an average speed emission model.

The hourly emission rate of a given pollutant, in g /(km·h), for a road segment (link) of the i-th aggregated category during the j-th hour is calculated as

where is the number of vehicle categories considered, and is the exhaust emission factor of the given pollutant for vehicle of the k-th category travelling at the average speed .

One of the main sources of PM2.5 and NOx emissions in cities is road traffic. Therefore, in this study, emission calculations were performed for these pollutants. It was assumed that the vehicle age (environmental) structure in the analysed urban network corresponds to the national structure [28,29]. In the case of PM2.5, it was also assumed that emission arise solely from fuel combustion.

The vehicle age structure is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Vehicle age structure [28].

To determine the exhaust emission factor , the COPERT model [20] was applied, assuming the following conditions [29]:

- Passenger cars operate with a warmed-up engine. The share of vehicles in this group powered by gasoline is 50.4%, by diesel—32.3%, and by LPG—17.3%;

- Within the light-duty vehicles group, the share of individual weight subcategories is assumed equal. The share of vehicles in this group powered by gasoline is 22.9%, and by diesel—77.1%.

- Only urban buses are considered in the bus group. The share of buses in this group with a gross vehicle weight (GVW) below 18 Mg is 88.1%, while the remaining share consists of vehicles with GVW above 18 Mg.

- For heavy-duty vehicles, the share of rigid (without trailers) and articulated trucks is assumed equal. The most numerous subcategories in the rigid trucks group are vehicles with GVW in the range of 7.5–12 Mg (32.4%), vehicles with GVW in the range 14–20 Mg (21.7%), and vehicles with GVW below 7.5 Mg (19.5%). In the articulated trucks group, the largest subcategory consists of vehicles with GVW below 20 Mg (96%).

- For trucks and buses, vehicle load (occupancy) is assumed at 50%.

The PM2.5 and NOx exhaust emission factors calculated for vehicles of a particular category, taking into account the above assumptions and the presented vehicle age structure, are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Calculated emission factors for PM2.5 and NOx.

The presented PM2.5 emission factor values for passenger cars reflect the fact that more than 70% of the vehicle fleet is 10 years old or older, among which the share of diesel-engine vehicles is higher compared to the group of younger vehicles. In the group of gasoline-powered vehicles, medium-size passenger cars of Euro 4 and Euro 6 categories with direct injection (GDI) as well as port injection (PFI) have non-zero PM2.5 emission factors.

3. Results and Discussion

Using the procedure described in Chapter 2, aggregated road categories were determined for the considered urban road network. The length of the road network broken down by the respective aggregated road categories is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Lengths of roads in each aggregated category in the considered network (total length including number of lanes).

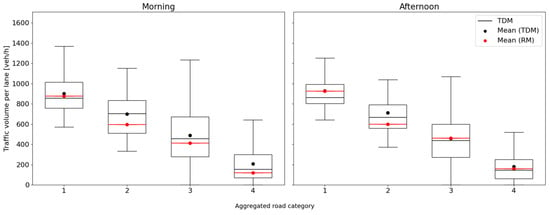

The traffic parameters obtained using the proposed model (hereafter referred to as the Rapid Model—RM) were compared with data from the travel demand model (hereafter referred to as TDM). The TDM data were provided to the authors by the Municipal Road Authority in Bielsko-Biała. The average traffic volume estimated by the RM (red circular marker) along with the statistical distribution of traffic volumes calculated by the TDM during morning and afternoon peak hours is shown in Figure 3. For the TDM data, the boxes represent the interquartile range (from the first to the third quartile), the middle line indicates the median, the black circular marker shows the mean, and the whiskers indicate the observed minimum and maximum values.

Figure 3.

Comparison of traffic volume for a given aggregated road category between TDM data and estimated by the RM: morning peak (left) and afternoon peak (right).

The analysis of results for the morning and afternoon peak traffic conditions indicates that the mean traffic volume estimated by the RM for each aggregated road category falls within the interquartile range (between the first and third quartiles) of the TDM data. It is also noticeable that the mean traffic volume for the RM model for the morning peak traffic conditions is for any road category lower than the value for the TDM model. The differences are in the range of 22–108 veh./h. The largest difference in mean traffic volume occurs for the second road category.

During the afternoon peak, mean traffic volumes in both models are higher compared to the morning peak for three out of four aggregated road categories. Again, the largest difference in mean traffic volume is observed for the second road category, while differences for the other categories are much smaller. The differences are in the range of 2–113 veh./h. The relative differences in mean traffic volumes between the two models for each category remain comparable to those observed in the morning peak.

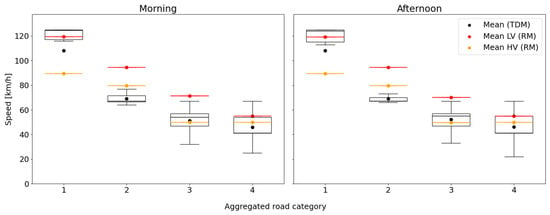

The estimated mean traffic speeds for light and heavy vehicles on road segments of the respective aggregated categories in the RM (red and orange circular markers, respectively), along with the traffic speed statistics from the TDM are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of traffic speeds for a given aggregated road category between TDM data and RM estimates: morning peak (left) and afternoon peak (right).

Analysing the data presented in Figure 4, it can be observed that within each model, mean traffic speeds during the morning and afternoon peaks differ negligibly. The mean speeds for LV and HV vehicles in the RM for the fourth aggregated category fall within the interquartile range of the TDM data. The interquartile range of TDM data also contains the mean speed for HV vehicles generated by the RM for the third category and the mean speed for LV vehicles in the first category.

The mean traffic speed calculated for the first road category during morning and afternoon peak traffic conditions is almost the same for both models. For the other road categories, the mean traffic speed for the RM model is higher than the corresponding value for the TDM model. The differences range from 4 to 18 km/h. The largest difference between the models was observed for the second road category and afternoon peak traffic conditions.

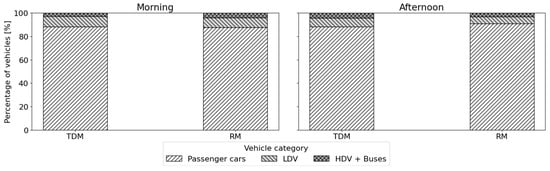

A comparison with TDM data can also be made regarding the averaged percentage share of each vehicle category for the respective aggregated road categories. The comparison of average percentage shares of vehicle categories during the morning and afternoon peaks for both models is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Averaged percentage shares of vehicle categories on the road network during the morning peak (left) and afternoon peak (right).

The data presented in Figure 5 indicate that differences in the averaged percentage shares of vehicle categories estimated by the two models during the morning peak for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles do not exceed 1%, with the RM slightly underestimating the shares. In contrast, for the combined truck and bus category, the RM estimates a higher share of 4%, compared to 2.9% in the TDM. Slightly larger differences between the two models are observed for the afternoon peak conditions. In this case, the differences for the LDV and truck and bus categories are similar, with the RM indicating lower shares, while for passenger cars, the TDM shows a 1.5% lower share.

In summary, the comparison of traffic parameters estimated using the proposed simplified model with the calibrated TDM for the analysed urban road network indicates a satisfactory accuracy. To assess the impact of using the simplified model for traffic parameter estimation instead of a calibrated TDM, calculations of the emission in the urban road network were performed.

Calculated total hourly emission of PM2.5 and NOx during the morning and afternoon peaks for all roads within each aggregated road category are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Hourly emission of PM2.5 and NOx for the urban road network during morning and afternoon peak hours according to the proposed RM and the calibrated TDM, broken down by aggregated road categories.

The analysis of the calculation results presented in Table 6 indicates that using traffic parameters estimated with the RM leads to higher total PM2.5 emission and lower NOx emission compared to the results obtained with parameters estimated by the TDM. The total hourly PM2.5 emission calculated for RM data during the morning and afternoon peaks are approximately 16% and 13% higher, respectively. In turn, the total hourly NOx emission during the morning and afternoon peaks are approximately 4% and 9% lower, respectively.

The differences between the calculated emission of PM2.5 and NOx are relatively small for the second aggregated road category, which constitutes 63% of the network. The largest percentage differences for PM2.5 occur in the case of the third aggregated road category, which constitutes 5.5% of the network. In turn, the largest percentage differences for NOx occur in the case of the fourth aggregated road category, which constitutes 14% of the network.

In summary, the results obtained for both models indicate that roads belonging to the first and second aggregated categories account for 90% of the total network emission for both PM2.5 and NOx. The remaining 10% of emissions are generated on approximately 20% of the network, which consists of roads belonging to the third and fourth aggregated categories.

Therefore, assuming that the TDM result is the reference value, the use of the proposed RM allows for estimating emissions for the entire network with an error of approximately 15%. This error is at an acceptable level, considering that the RM model does not account for speed and traffic volume variations within a given aggregated road category. Due to the wider variability of traffic flow than traffic speed within roads belonging to given aggregated category, differences in traffic volume will have a greater impact on emission error than differences in speed. At the same time, the estimated total emission for the second aggregated road category clearly indicate that partial errors may offset each other. Despite the largest differences between the average speed and traffic volume values provided by the two models for this category, the final difference in total estimated emission is the smallest.

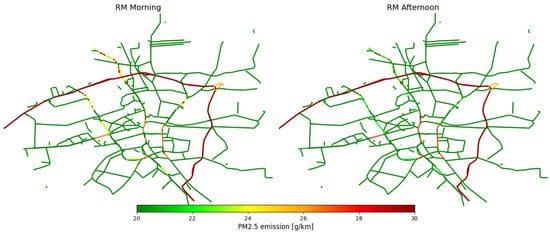

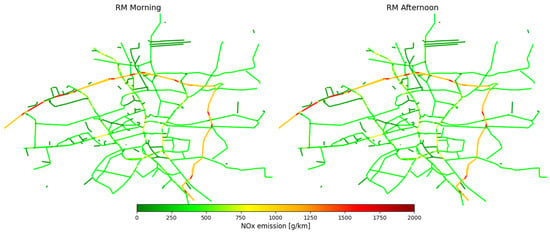

Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the distribution of PM2.5 and NOx emissions, respectively, in the Bielsko-Biała road network, obtained with the RM data for the morning and afternoon peak hours.

Figure 6.

Distribution of road traffic PM2.5 emissions in the urban road network during morning and afternoon peak hours.

Figure 7.

Distribution of road traffic NOx emissions in the urban road network during morning and afternoon peak hours.

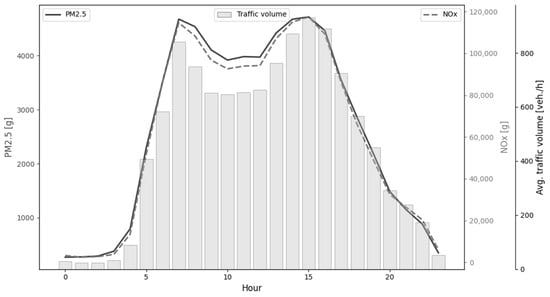

The RM proposed in this study, due to the use of traffic measurement data collected over a full day, allows for the calculation of the emission for any hour of the day. The histogram of hourly traffic volume and estimated emission of PM2.5 and NOx obtained with the RM data for the urban road network is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Hourly emission of PM2.5 and NOx and the average traffic volume in the urban road network for each hour of the day.

The analysis of the data presented in Figure 8 indicates significant emission levels not only during the morning peak (7 a.m.), but also in the following hour after the peak. For the afternoon peak (3 p.m.), similar total emission levels in the network are observed during the two hours preceding the peak and the hour following it. The results allow for the assessment that approximately 70% of the daily emission of PM2.5 and NOx in the entire network occur within a 10 h period from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m.

4. Conclusions

Assessing the effectiveness of measures aimed at promoting sustainable urban mobility with respect to the environmental impact of road transport requires appropriate tools for comprehensive analyses. To evaluate the effects of various transport scenarios on air quality, an emission model is an essential tool. For the emission inventory, such a model requires traffic parameters as inputs. In some cities, traffic managers have access to a calibrated TDM, which provides traffic information, though this data is often limited to peak hours. In such cases, estimating emission for other hours of the day requires an additional tool. More importantly, in areas where a TDM has not been developed, there is a need for an alternative tool that is less time-consuming to prepare. The model presented in this study offers such a solution, with key features including the following:

- Simplification of the network representation into four aggregated road categories based on the original OSM classification and permissible traffic speeds;

- Traffic volumes based on empirical data collected on network segments representing each aggregated class;

- Consideration of different average speeds for light and heavy vehicles within the traffic stream;

- Estimation of traffic parameters for any hour of the day;

- Low time requirements for model preparation.

These features make the proposed solution suitable as a screening model for various analyses concerning urban air quality in the context of sustainable transport. The approach based on aggregated road categories allows the application of the model to the transport network of any city, provided that traffic volume data are available. The presented emission factors, derived according to the COPERT model, reflect the vehicle fleet structure in Poland under the assumption of equal numbers in certain subcategories and strictly defined percentage shares of specific fuel types. This assumption results from the lack of detailed data and, of course, constitutes a significant factor affecting the accuracy of emission estimation. Another source of uncertainty is the adopted traffic parameters. A particular challenge is determining the traffic speed for different traffic volumes and segment capacities. In order to increase the accuracy of traffic speed estimation, the model can be calibrated by appropriately adjusting the empirical parameters of function (4) or by using another function linking free-flow speed, traffic volume, and average traffic speed. In both cases, additional measurement data are necessary to determine the required parameters. Nevertheless, even after extending the procedure to include calibration of the speed estimation function, the range of data required to run the model is significantly smaller compared to the dataset needed for developing a TDM.

In summary, the method for rapid computation of transport-related emission presented in this study combines measurement-based and simulation-based approaches. Measurements are conducted to collect data on vehicle flow, while the average vehicle speed is determined analogously to macroscopic traffic models. The method requires access to data from the open OSM service and the assignment of roads of various classes to four aggregated categories. This approach reduces the number of required traffic cross-section measurements. Consequently, the application of this method for emission inventory lowers both the financial costs and the time needed to carry out this task compared to other solutions proposed in the literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B. and A.R.; Methodology, K.B. and A.R.; Software, A.R.; Validation, A.R.; Formal analysis, K.B.; Investigation, K.B.; Writing–original draft, K.B.; Writing–review & editing, A.R.; Visualization, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ježek, I.; Blond, N.; Skupinski, G.; Močnik, G. The traffic emission-dispersion model for a Central-European city agrees with measured black carbon apportioned to traffic. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 184, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, K.; Drąg, Ł. Using an operational air pollution forecast system for evaluation of local emission abatement policy scenarios. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 361, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saide, P.; Zah, R.; Osses, M.; Ossés de Eicker, M. Spatial disaggregation of traffic emission inventories in large cities using simplified top–down methods. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 4914–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policarpo, N.A.; Silva, C.; Lopes, T.F.A.; dos Santos Araújo, R.; Cavalcante, F.S.A.; Pitombo, C.S.; de Oliveira, M.L.M. Road vehicle emission inventory of a Brazilian metropolitan area and insights for other emerging economies. Transp. Res. Part D 2018, 58, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Sahu, S.K.; Kesarkar, A.P.; Biswal, A. Estimation of high resolution emissions from road transport sector in a megacity Delhi. Urban Clim. 2018, 26, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Maes, A.; Hoinaski, L.; Meirelles, T.B.; Carlson, R.C. A methodology for high resolution vehicular emissions inventories in metropolitan areas: Evaluating the effect of automotive technologies improvement. Transp. Res. Part D 2019, 77, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xia, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Ye, J.; Hou, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; et al. Hyperfine-resolution mapping of on-road vehicle emissions with comprehensive traffic monitoring and an intelligent transportation system. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 16985–17002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, M.A.M.; Lorenzo-Sáez, E.; Luzuriaga, J.E.; Prats, S.M.; Moreno-Pérez, J.A.; Urchueguía, J.F.; Oliver-Villanueva, J.V.; Lemus, L.G. From traffic data to GHG emissions: A novel bottom-up methodology and its application to Valencia city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Szeto, W.Y.; Han, K.; Friesz, T.L. Dynamic traffic assignment: A review of the methodological advances for environmentally sustainable road transportation applications. Transp. Res. Part B 2018, 111, 370–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, K. Multipoint source method in air pollution modelling of cold start emission. Environ. Model. Assess. 2006, 11, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, R.; Kamel, I.; Wang, A.; Abdulhai, B.; Hatzopoulou, M. Development of a hybrid modelling approach for the generation of an urban on-road transportation emission inventory. Transp. Res. Part D 2018, 62, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.A.; Kumar, P.; Alonso, M.F.; Andreão, W.L.; Pedruzzi, R.; dos Santos, F.S.; Moreira, D.M.; de Almeida Albuquerque, T.T. Traffic data in air quality modeling: A review of key variables, improvements in results, open problems and challenges in current research. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.; Isakov, V.; Touma, J.S.; Benjey, W.; Thurman, J.; Kinnee, E.; Ensley, D. Resolving Local-Scale Emissions for Modeling Air Quality near Roadways. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2008, 58, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Duffy, P.; Hyde, B.; McNabola, A. Improvement in the estimation and back-extrapolation of CO2 emissions from the Irish road transport sector using a bottom-up data modelling approach. Transp. Res. Part D 2017, 56, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Ma, J.-L.; Li, L.; Lin, X.-F.; Xu, W.-J.; Ding, H. A high temporal-spatial vehicle emission inventory based on detailed hourly traffic data in a medium-sized city of China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Bao, S.; Wu, X.; Yang, D.; Wu, Y. Mapping dynamic road emissions for a megacity by using open-access traffic congestion index data. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, A. Impact of license plate restriction policy on emission reduction in Hangzhou using a bottom-up approach. Transp. Res. Part D 2015, 34, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, J.; Dong, S.; Wen, X.; Jin, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, X. Temporal variations of local traffic CO2 emissions and its relationship with CO2 flux in Beijing, China. Transp. Res. Part D 2019, 67, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSM. OpenStreetMap. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- EMEP/EEA. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2023 (Updated 2024), 1.A.3.b.i-iv Road Transport 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/emep-eea-guidebook-2023 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Brzozowski, K.; Ryguła, A.; Maczyński, A. An integrated system for simultaneous monitoring of traffic and pollution concentration—Lessons learned for Bielsko-Biała, Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Air Quality Statistics. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/air-quality-statistics-dashboards (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- INKOM. Wykonanie Kordonowych Pomiarów Ruchu Kołowego na Ulicach Miasta Bielsko-Biała. Available online: https://mzd.bielsko.pl/miejski-zarzad-drog-w-bielsku-bialej-dysponuje-najnowszymi-danymi-obrazujacymi-natezenie-ruchu-pojazdow-w-kluczowych-dla-miasta-punktach-taka-wiedza-pozwala-skutecznie-korygowac-i-usprawniac-plynnosc/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Oskarbski, J.; Jamroz, K.; Smolarek, L.; Zawisza, M.; Żarski, K. Analysis of Possibilities for the Use of Volume-delay Functions in the Planning Module of the TRISTAR System. Transp. Probl. 2017, 12, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, N.; Arkatkar, S.; Joshi, G.; Antoniou, C. Modified Bureau of Public Roads Link Function. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2677, 966–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniz, A.; Kocianova, A. Analysis in the field of volume-delay function research. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transportation Research Board. Highway Capacity Manual 2010, 5th ed.; National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Transport—Activity Results in 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/transport-i-lacznosc/transport/transport-wyniki-dzialalnosci-w-2024-r-,9,24.html (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- GUS. Final Report: Development of the Methodology and Estimation of the External Costs of Air Pollution Emitted from Road Transport at National Level; Research and Statistical Education Centre: Szczecin, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/6334/6/1/1/raport_opracowanie_metodyki_i_oszacowanie_kosztow_zewnetrznych_emisji_zanieczyszczen.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).