1. Introduction

One of the most pressing challenges facing modern society is highway traffic, along with its numerous associated issues, including delays, traffic accidents, and environmental pollution. Each additional minute spent in traffic represents an irreversible loss of time in a person’s life, significantly diminishing overall quality of life. The impact of traffic congestion is particularly severe in large urban areas. In Türkiye, Istanbul stands out as the most populous city, boasting an official population of 15,655,924 [

1]. This number does not account for irregular migrants or individuals traveling for daily commutes or tourism, which underscores the severity of traffic-related problems in the city. Despite numerous investments in rail systems, the traffic issues in Istanbul continue to worsen. According to data released by INRIX, the average delay experienced by drivers in Istanbul rose by 15.38% in 2024 compared to the previous year, amounting to an astounding 105 h [

2]. This statistic positions Istanbul as the global leader in traffic delays. Addressing these challenges is essential for achieving sustainable urban development and aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

E-scooters are not only a mobility innovation but also a potential enabler of sustainable cities through energy-efficient and low-emission transport modes. Promoting micromobility systems such as e-scooters plays an important role in advancing sustainable transportation by reducing emissions, noise, and congestion. In response to these challenges, individuals facing delays in road traffic are actively seeking innovative solutions. Various micromobility systems, such as bicycles, e-bikes, and e-scooters, have gained traction in this context. E-scooters, in particular, have recently emerged as a popular transportation option in Türkiye. With several rental companies entering the market, the number of users has surged, making e-scooters a practical alternative for various transportation modes, especially over short distances.

However, the regulations governing e-scooter use in urban traffic remain underdeveloped. Notably, the “Electric Scooter Regulation” was published in the Official Gazette [

3], and the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi—IBB) has formulated an e-scooter directive for Istanbul [

4]. Similar initiatives are also underway in other cities across Türkiye.

In recent years, e-scooters have become a favored last-mile transportation option in Türkiye, particularly among young people. Nevertheless, regulations concerning the operating conditions and rules for e-scooters on highways have only recently begun to take shape. Consequently, many e-scooter users and other stakeholders in highway traffic find themselves operating vehicles without full awareness of these regulations. The published guidelines are often informed by examining comparable rules in other countries and are sometimes adapted to suit the Turkish context. However, since traffic conditions in each country are primarily influenced by driver behavior, these conditions can vary significantly. Therefore, it may be beneficial to establish tailored operating conditions for e-scooters specific to each country or city.

Central and local authorities should seek to understand public opinion regarding e-scooters, including user desires and usage patterns. This information is essential for crafting effective regulations. Additionally, insights into user attitudes, behaviors, and preferences are crucial for e-scooter sharing companies, as this understanding can inform their strategic and operational policies, enhance service quality, and increase market share. Well-regulated e-scooter services with improved quality may lead to increased demand, subsequently alleviating problems associated with motor vehicle traffic.

This study examined various preferences of e-scooter users concerning their usage and predicted mode choices under different conditions using machine learning techniques. An online survey was conducted with 462 individuals, either current or potential e-scooter users, residing in Istanbul. The survey results were analyzed utilizing Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Decision Trees (DTs), Random Forest (RF), and Gradient Boosting (GB) methods. The notable success rates of these models, particularly when compared to traditional discrete choice models, highlight their considerable potential as decision-support tools for government authorities and urban planners. This enhanced predictive capability enables more informed policy-making and resource allocation, ultimately leading to improved urban mobility solutions. Additionally, the findings offer valuable insights for shared e-scooter service providers, equipping them with practical strategies to refine their operations and enhance user engagement. By gaining a deeper understanding of user preferences and behaviors, these providers can better tailor their services to meet market demands, increase user satisfaction, and boost overall operational efficiency.

Numerous studies have examined e-scooter mode choice behavior using discrete choice models, such as multinomial logit, mixed logit, and nested logit [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, significant gaps still exist that this study aims to address. Firstly, with a few exceptions [

8], previous research has predominantly relied on traditional discrete choice frameworks, which typically achieve prediction accuracies below 60% when applied to micromobility mode choice. Secondly, most existing datasets consist either of revealed-preference data that offers limited attitudinal insights or stated-preference surveys featuring a small number of hypothetical scenarios (usually ranging from 4 to 9 per respondent), thus constraining the models’ ability to capture heterogeneity in preferences across a broader array of travel time and cost combinations. Thirdly, while machine learning approaches have occasionally been employed for general mode choice prediction, there has yet to be a systematic comparison of multiple ML algorithms (including ANN, DT, RF, and GB) specifically for e-scooter-inclusive mode choice in the literature. Fourthly, no prior research has integrated a large-scale stated-preference experiment (with 462 respondents across 24 orthogonal scenarios, resulting in 11,088 observations) within a megacity context, alongside detailed demographic, attitudinal, and infrastructural variables, to train and compare ML models. Lastly, the application of model outputs within a policy-oriented decision-support interface for municipal authorities and shared-micromobility operators—explicitly showcased as a practical outcome in

Section 6—has not been explored in the existing e-scooter research.

The novelty of the present work therefore lies in four key aspects:

The development of a comprehensive, scenario-rich dataset specifically tailored to the traffic and cost conditions of Istanbul.

The first systematic application and performance evaluation of four widely adopted machine learning algorithms for predicting e-scooter-inclusive mode choice.

The attainment of significantly higher predictive accuracy (92.40% with DT) compared to previously reported discrete choice models.

The clear translation of the resulting high-performance model into actionable policy and operational recommendations, which includes potential integration into traffic simulation platforms and the creation of a user-friendly interface for planners and micromobility providers.

The second chapter of the study reviews literature on models utilized in mode choice and their applications in micromobility. The third chapter details the survey and data collection process, while the fourth chapter focuses on the machine learning methods employed. The fifth chapter presents the model development process and compares the performance of the various models. Finally, the sixth chapter summarizes and discusses the findings of the study.

2. Literature Review

In transportation planning, discrete choice models (DCMs) are widely employed to analyze mode selection. These models have been utilized across various contexts, including urban and intercity travel [

16], freight transport [

17], airport access preferences [

18,

19], traffic safety research [

20], route selection decisions [

21,

22], and the evaluation of new transportation modes [

23]. Among the various models, Binary Logit (BL), Multinomial Logit (MNL), and Nested Logit (NL) models are the most commonly used [

16], while Mixed Logit (ML) models have increasingly gained traction since the early 2000s [

23,

24].

Discrete choice models (DCMs) are based on the assumption that individuals seek to maximize their utility [

16]. Multinomial logistic (MNL) models assume that coefficients are homogeneous across individuals, while mixed logit (ML) models account for variations that reflect behavioral differences among users [

25]. Although these methods are well-established and easy to interpret, they often face challenges in capturing the complex interactions between user characteristics, contextual conditions, and emerging micromobility behaviors, such as the use of e-scooters.

Recent studies have examined e-scooter mode choice across various contexts. Research by Reck et al. investigated user preferences for e-scooters and e-bikes in Zurich through MNL and ML frameworks, revealing a strong inclination toward micromobility solutions, particularly with parking available during peak periods—an approach that could effectively reduce car trips [

5]. Zuniga-Garcia et al. highlighted the importance of infrastructure-focused modeling for e-scooters [

26]. Additional research [

6,

7,

27,

28] indicates that usage patterns differ based on demographics and accessibility, with e-scooters primarily replacing short trips of under 15 min [

6]. While these studies offer valuable insights, traditional discrete choice models often struggle to adequately capture individual-level variability or travel decisions that depend on specific scenarios [

8].

Demographic analyses indicate that young, educated men constitute the primary users of e-scooters [

9,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Furthermore, the types of transportation modes replaced by e-scooters differ by region, with journeys shorter than 8 km accounting for approximately half of these substituted trips [

10]. Additional research underscores that e-scooters are often favored over walking or public transport for certain types of trips [

24,

25,

28,

29,

30], and the availability of parking further enhances their appeal [

5,

13,

14,

15].

Recent studies extend beyond mode choice to explore environmental and ergonomic impacts. For instance, Karpenko et al. investigated the vertical vibrations experienced by e-scooter riders across different pavement types, revealing potential long-term musculoskeletal risks [

33]. Similarly, Danilevičius et al. highlighted that traditional traffic noise models tend to underestimate peak noise exposure, emphasizing the necessity for dynamic mapping and infrastructure enhancements [

34,

35]. These studies illustrate both the strengths (such as experimental rigor and scenario-specific insights) and limitations (including restricted generalizability and a narrow focus on specific variables) of current research.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of key studies on e-scooter mode choice, highlighting their methodologies, contexts, advantages, and limitations. This overview underscores both the contributions and shortcomings in the existing literature, thus informing the methodology adopted in the current study. By integrating demographic, behavioral, and scenario-based data, our approach effectively addresses these gaps and establishes a more adaptable and precise framework for predicting transportation preferences in urban environments.

There is a notable scarcity of studies that explicitly explore e-scooter mode choice from a sustainability perspective, revealing a significant area for further investigation. The present study seeks to fill this gap by combining scenario-based travel choices, demographic traits, and behavioral data to develop predictive machine learning models suitable for integration into traffic simulation and policy evaluation frameworks.

3. Methodology

An online survey was conducted using Google Forms as part of the study, which received approval from the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Okan University during meeting number 158 on 21 September 2022. The survey was administered between 1 September 2023, and 1 May 2024, and included 512 participants. However, in accordance with the requirements of the TÜBİTAK 1001 project (project number 123M063), responses from individuals outside of Istanbul were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 462 participants.

This number exceeds the minimum required sample size of 384 for a population of over 500,000 in a heterogeneous context [

36,

37]. While definitive data on the total number of e-scooter users in Istanbul is lacking, one of the leading e-scooter sharing companies, Martı, reported through its founder, Oğuz Alper Öktem, that its user base surpassed 5 million as of 2021 [

38]. Considering potential users who have yet to try e-scooters, it is estimated that the total population exceeds 500,000. Therefore, the sample size of 462 is deemed sufficient for this study.

3.1. Survey Design

The first section of the survey gathered demographic information about e-scooter users, including details such as gender, age, income level, education level, and car ownership.

The second section focused on questions related to e-scooter usage, covering the following aspects:

Whether there is a bike lane within 250 m of their residence.

Their primary mode of transportation for daily travel.

The primary purpose of their trips (e.g., work, school, health, shopping).

Their preferred type of infrastructure for riding e-scooters (e.g., roads, sidewalks, bike lanes).

Whether they currently use or would consider using e-scooters on sidewalks.

The transportation modes they currently replace or would consider replacing with e-scooters.

The traffic conditions under which they prefer to use e-scooters (e.g., light, moderate, congested).

The maximum duration, in minutes, they prefer for a one-way e-scooter trip.

Their perception of the safety of using e-scooters.

Their opinions on the use of e-scooters on sidewalks.

Whether they currently use or would use e-scooters on roads with one-way or two-way traffic.

Their views on parking locations for e-scooters.

Whether they currently park or would park e-scooters in designated parking spots.

Their level of compliance with traffic rules.

Whether cost or safety is the primary factor influencing their preference for e-scooters.

The maximum hourly cost (in Turkish Lira–TL) they find acceptable for using e-scooters.

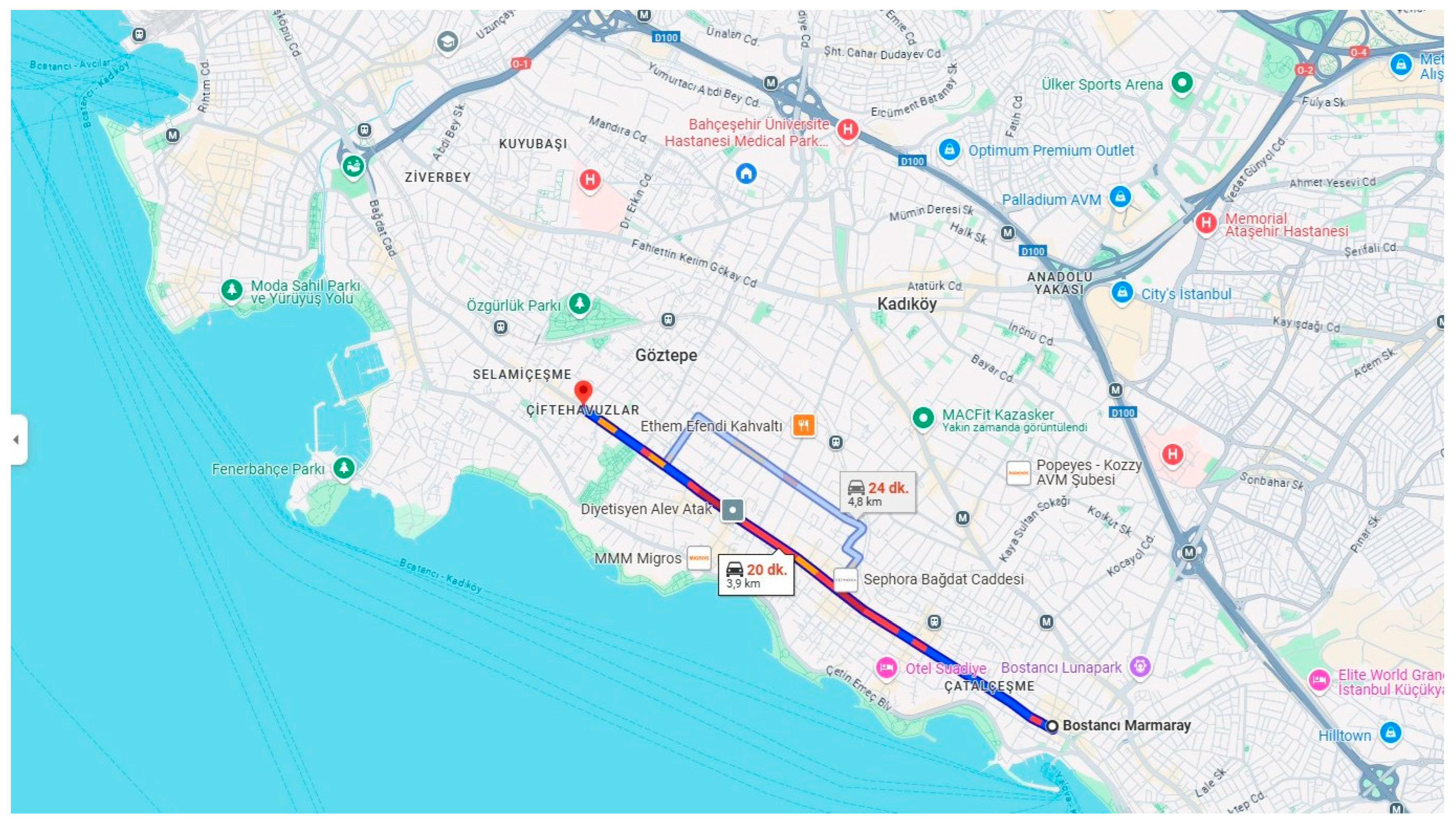

In the third and final section of the survey, respondents were presented with scenarios that included varying travel times and costs for private cars, public transportation, taxis, and e-scooters. For each scenario, participants were asked to indicate their preferred mode of transportation. These scenarios were based on a 4 km distance along Bağdat Avenue, specifically between the neighborhoods of Bostancı and Selamiçeşme in Istanbul.

Because participants were not familiar with traffic engineering terms, traffic conditions were described using three verbal categories: light, moderate, and congested. Travel times for these conditions along the 4 km route were obtained from Google Maps.

Figure 1 provides a screenshot of the measurements, and

Table 2 presents the travel times assigned to the four transportation modes.

Two levels have been established for travel costs across four modes of transportation: the current costs and the increased costs. The increase has been set at 65%, reflecting the inflation rate for 2023. The calculation of fees for a 4 km journey has been conducted as follows:

In Equation (1),

Fprivatecar represents the travel cost for using a private car. The variables involved are as follows:

BF is the price of one liter of gasoline in Turkish Lira (TL),

BS is the average fuel consumption in liters per kilometer, and

P is the average parking fee for a round trip per hour. In 2023,

BF was set at 34.48 TL [

40], BS was 8 L, and

P was 52 TL [

41].

For Public Transport:

In Istanbul, the price of a full ticket fare is 15 TL [

42].

In Equation (2),

Ftaxi denotes the taxi fare, where

A represents the starting fee,

M is the charge per kilometer,

Z is the hourly rate,

x is the distance traveled in kilometers, and t is the travel time in hours. In 2023, the rates in Istanbul were set as follows:

A was 19.17 TL,

M was 13.75 TL, and

Z was 152.73 TL [

43].

In Equation (3), Fescooter represents the fare for e-scooter rides, where B is the starting fee, C is the per-minute usage charge, and d is the duration of usage in minutes.

The average fare for a 4 km journey was determined by calculating the prices from three different companies. Based on this, a journey at the legal speed limit of 15 km/h would take approximately 16 min. In 2023, Binbin and Hop priced this distance at 75 TL, whereas Martı charged 82 TL. The mean fare of 77 TL was rounded down to 75 TL to make survey responses easier. The fares presented in

Table 3 were derived from Equations (1)–(3).

When assessing the number of scenarios, it is crucial to recognize that accounting for the combinations of travel time levels across various modes of transportation proves challenging. This is because cars, taxis, and public transit modes will be similarly influenced at each traffic speed level. In essence, while one mode may be traveling swiftly, the others cannot simultaneously be moving at a significantly slower pace. The e-scooter’s speed is held constant at 15 km/h across all congestion levels, consistent with the national legal speed limit for such vehicles. As illustrated in

Table 2, the travel time remains consistent across different traffic conditions, calculated at 16 min.

However, when examining travel cost levels, combinations among the modes are feasible. Utilizing a full factorial experimental design for each travel time [

14], the total number of scenarios would be calculated as 24 × 1 = 24. Consequently, the overall total becomes 24 × 3 = 72. Nevertheless, this substantial number could overwhelm respondents, prompting the use of an alternative experimental design to streamline the total.

In this case, a fractional factorial design was employed, resulting in a total of 24 scenarios for respondents to address. The fractional factorial design is typically employed when a full factorial design generates an unmanageable number of scenarios. It retains the orthogonality characteristic of the full factorial design while significantly reducing the total combinations. In this case, a ½ fraction was used, indicating that only half of the possible variable combinations from the full factorial design were included. The scenarios shown to survey participants are listed in

Table 4.

While the survey did not directly measure environmental attitudes, questions related to micromobility usage indirectly reflect participants’ sustainable mobility preferences.

3.2. Survey Analysis

Table 5 presents the percentage distribution of survey participants categorized by gender, driving license possession, income level, preferred infrastructure for e-scooter usage, and their perceptions of e-scooter safety. The gender distribution among participants is nearly balanced. A significant majority possess a driving license, whereas only about 30% of respondents own a car. In terms of income, most participants report having no income or earning at a minimum wage level, primarily because 60% of the survey respondents are students. When asked about their preferred infrastructure for e-scooter use, a substantial majority (68.3%) favor bike lanes.

However, the survey responses reveal that e-scooters are not regarded as very safe, with only approximately 8% of participants considering them safe or very safe. This perception is likely influenced by the absence of dedicated bike lanes in Istanbul, as e-scooters primarily operate on main roads and sidewalks, which raises safety concerns.

4. Machine Learning Models

This section outlines the theoretical foundations and mathematical formulations of four machine learning methods used in this study: Artificial Neural Networks, Decision Trees, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting. Each method is explained with its operational mechanism and mathematical principles.

4.1. Artificial Neural Networks

ANNs mimic the structure of biological neural networks and are used to model intricate, non-linear data relationships in both classification and regression applications. They are built from linked neurons structured into an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and a final output layer.

The input layer receives feature vectors x = [x1, x2, …, xn]. In each hidden layer, neurons take the weighted input values, add a bias, and process them through an activation function to enable non-linearity, while the output layer provides the ultimate prediction or classification. Training of ANNs is carried out using backpropagation and gradient descent, aimed at minimizing a specified loss function.

For a neuron in layer l, the weighted sum is computed as:

where

are weights,

are activations from the previous layer, and

is the bias. The activation is:

where

g(

·) is an activation function, such as Rectified Linear Unit (

ReLU) (

g(

z) =

max(0,

z)) or sigmoid

. The loss function for regression typically is mean squared error (MSE):

For classification, cross-entropy loss is used:

Weights are updated via gradient descent:

where

η is the learning rate [

44].

4.2. Decision Trees

DTs are models that segment the input space into distinct regions based on feature values. They apply to both regression and classification tasks. The internal nodes of the tree represent splits determined by different features, while the leaf nodes indicate the output classes or values. The root node encompasses the entire dataset. Classification trees rely on metrics such as Gini impurity and information gain to create splits, whereas regression trees use variance reduction Additionally, pruning can be employed to simplify the model.

For classification, Gini impurity is calculated as:

where

pi is the proportion of class

i, and

C is the number of classes. Information gain, based on entropy, is:

where

Nj is the number of samples in child node

j, and

N is the total number of samples. For regression, variance reduction is used:

Splits are chosen to minimize the weighted variance of child nodes [

45].

4.3. Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble technique that aggregates the outputs of multiple decision trees to enhance prediction performance. It employs bootstrap aggregating (bagging) and introduces feature randomness into the process.

Multiple bootstrap samples are created from the training data, with each decision tree being trained on a different sample. At each split in the tree, a random subset of features is considered (typically √p, where p is the total number of features). For classification tasks, the final predictions from the trees are determined through majority voting, while for regression tasks, the predictions are averaged.

Given B bootstrap datasets D1, D2, …, DB, each tree Tb (for b = 1, 2,…, B) outputs a prediction . The final prediction is:

Out-of-bag (OOB) error is estimated using samples excluded from each tree’s bootstrap sample [

46].

4.4. Gradient Boosting

GB is an ensemble method that builds decision trees in a sequential manner, where each tree aims to rectify the errors made by its predecessors by minimizing a loss function through gradient descent.

The algorithm begins with a constant prediction and then iteratively adds trees that predict the negative gradient of the loss function. The final output is generated by combining the predictions from all trees, each weighted by a learning rate [

47].

For regression, the loss function is typically MSE:

For classification, log-loss is used:

where

. The model is initialized with

F0(

x), such as the mean for regression. For each tree

m = 1, 2, …,

M:

5. Model Development and Comparison of Model Performances

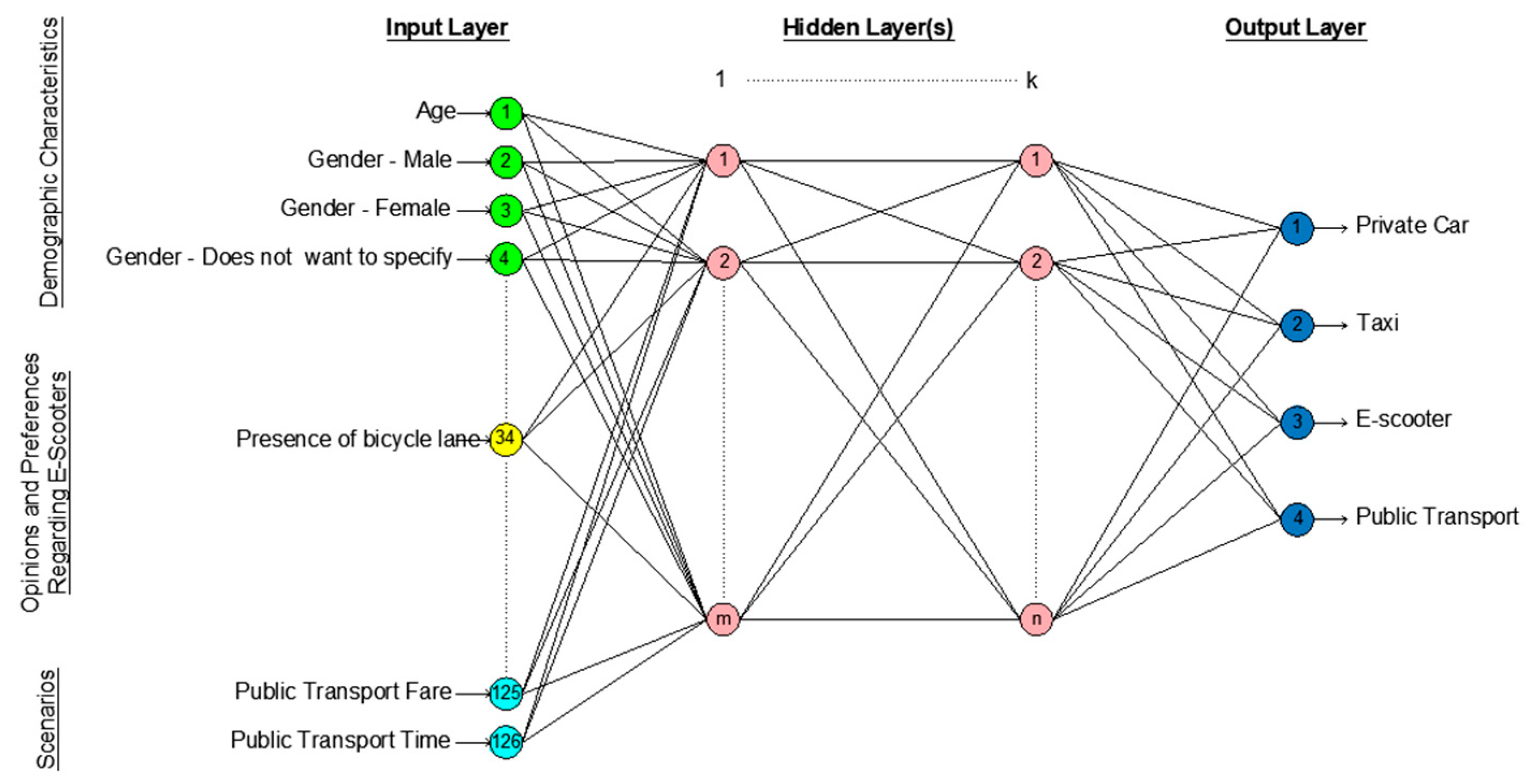

In this study, the input data for the developed models were derived from two sections of the survey: the “Demographic Characteristics” section and the “Opinions and Preferences Regarding E-Scooters” section. Additionally, travel times and costs defined in the scenarios (see

Table 3) were utilized as inputs for the models.

Among the demographic characteristics, age was treated as a continuous variable. It was normalized to a range between 0 and 1 by dividing each participant’s age by 100, and a single input neuron represented this. Similarly, the number of household members and the number of cars in the household were normalized by dividing by 10, resulting in values between 0 and 1, with each represented by a single input.

Questions regarding ownership of a driving license, private car, and e-scooter were binary (yes/no) and represented by a single input value. A dummy variable was used, where 1 indicated “yes” and 0 indicated “no.”

For questions that include more than two response options—such as education level, income level, and perceptions of safety—one-hot encoding was utilized. Each category was assigned a separate input, with the selected category marked as 1 and all others as 0. For instance, in the case of gender, if a participant identified as male, the first input for gender would be set to 1, while the other two inputs would be set to 0. Conversely, if a participant identified as female, the second input would be 1, with the remaining inputs set to 0. If a participant chose not to disclose their gender, the third input would be set to 1, and the others would be 0. Similarly, for ordinal variables like income level and safety perceptions, one-hot encoding was applied, allowing the model to process all response options without imposing a numerical order.

Due to the numerous alternatives available, variables such as the participant’s district of residence and profession detail were not included in the models.

In the “Opinions and Preferences Regarding E-Scooters” section, six questions with binary responses (yes/no) were represented by a single input each. For the remaining 17 questions, the number of inputs corresponded to the number of selectable answers for each question.

The study defined eight scenarios, each representing different traffic conditions (light, moderate, or congested), as individual data points. Consequently, for each participant, the combination of three traffic conditions and eight scenarios resulted in a total of 24 different scenarios. Participants were asked to choose their preferred mode of transportation—options included private car, taxi, e-scooter, or public transportation—under each scenario. The costs and travel times for each transportation mode were also specified for the different conditions, with the last eight input values reflecting these variables. These values were normalized to a range of 0 to 1 by dividing the cost values by 200 and the time values by 60.

As a result, each model utilized 126 inputs. All 126 input variables used in the models, along with their type and encoding method, are summarized in

Table 6. The model’s output indicates the preferred mode of transportation for a user, given the current conditions. Since there are four possible modes, a separate output was defined for each. The output corresponding to the chosen category receives a value of 1, while all other categories are assigned a value of 0.

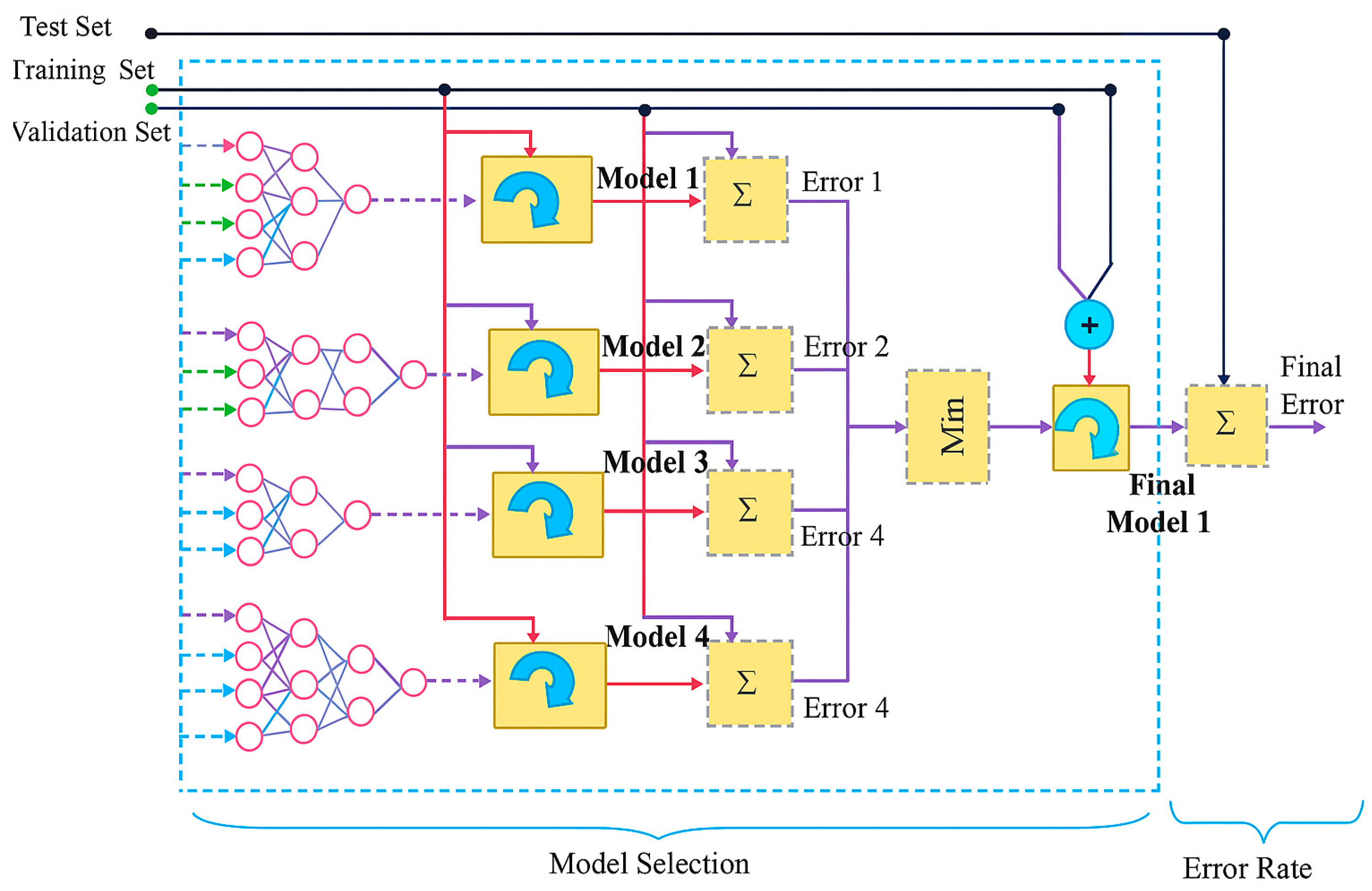

The models were therefore designed to predict four outputs based on 126 inputs. With 462 participants evaluating 24 scenarios each, a total of 11,088 data points were generated. For all models, the data was split into three parts: 70% was used for training, 15% for testing, and the remaining 15% for validation.

The study employed ANN, DT, RF, and GB algorithms to forecast participants’ transportation preferences across various scenarios and conditions. In the revised analysis, the dataset was segmented by participants, ensuring that all 24 responses from any given individual were assigned exclusively to either the training, validation, or test set. The data was divided, allocating 70% for training, 15% for testing, and 15% for validation.

As detailed in

Table 7, models were developed for five distinct datasets, with the model exhibiting the highest performance selected as the base model. The predictive capabilities of these models were evaluated using all 11,088 data points while preserving the integrity of each participant’s responses by confining them to a single data split. This modification facilitates a more accurate assessment of model performance, thereby better reflecting true generalization to unseen participants.

The ANN model is composed of 126 input neurons and four output neurons. The number of hidden layers, along with the number of neurons in each layer, was optimized using a grid search method. Various configurations were evaluated, including one or two hidden layers, with each layer containing between 1 and 50 neurons. The architecture of the developed ANN is depicted in

Figure 2. The green color represents the neurons corresponding to the demographic characteristics in the input layer; the yellow color represents the opinions and preferences regarding e-scooters; the light blue color represents the scenarios; the pink color represents the neurons in the hidden layer; and the dark blue color represents the neurons in the output layer. The numbers indicate the index of each neuron within its respective layer.

A three-way data split method was utilized to mitigate overfitting and to determine the optimal network architecture.

Figure 3 illustrates the flowchart of this three-way data split approach. Initially, the data was randomly shuffled and divided into three distinct sets: training (70%), testing (15%), and validation (15%). The assessment of the most effective network architecture was performed based on the dataset combinations detailed in

Table 7. The optimal architecture for each ANN model was chosen based on the MSE performance metric.

The most effective architecture for the ANN model comprised 126 neurons in the input layer, two hidden layers each containing 50 neurons, and four output neurons.

To assess the performance of the developed models, we first calculated the True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) values for each class. These terms can be defined as follows:

TP (True Positive) → Correctly predicting the positive class

TN (True Negative) → Correctly predicting the negative class

FP (False Positive) → Incorrectly predicting the negative class as positive

FN (False Negative) → Incorrectly predicting the positive class as negative

Using these values, we computed the support, weight, as well as the macro and weighted accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score metrics for each class. The formulas employed in these calculations can be found in Equations (20)–(29).

Table 8 and

Table 9 present the confusion matrices and performance metrics of the four developed models—ANN, DT, RF, and CB—used to predict users’ preferred travel mode: Private Car, Public Transport, Taxi, and E-scooter.

Table 8 and

Table 9 illustrate the imbalance within the dataset: the Taxi class has the fewest observations, with a support of 640 and a weight of 0.058. In contrast, the Public Transport class (5186 observations, weight = 0.467) and E-scooter class (3663 observations, weight = 0.330) represent the majority. Meanwhile, the Private Car class is a minority, comprising 1599 observations and a weight of 0.144.

The confusion matrices reveal distinct patterns of misclassification across the models. For instance, the ANN model shows substantial confusion between the majority classes (Public Transport and E-scooter) and the minority classes (Taxi and Private Car). Notably, many trips classified as Private Car are misidentified as E-scooter (184 instances) or Taxi (640 instances), resulting in a relatively low macro recall of 0.509 and a macro F1-score of 0.505. In contrast, the weighted metrics are higher—reflecting an accuracy of 0.872 and a weighted recall of 0.704—due to the model’s better performance on the classes with higher support.

DT model demonstrates the best overall performance as shown with bold in

Table 9, among the evaluated methods, achieving the highest macro accuracy of 0.924 and a macro F1-score of 0.829. Its confusion matrix reflects strong discrimination across all travel modes, particularly for the low-support taxi class, which is classified more consistently than in the cases of ANN, RF, and CB. The weighted metrics, including an accuracy of 0.897 and a recall of 0.890, indicate robust performance across both majority and minority classes.

RF exhibits moderate performance, with a macro recall of 0.553 and a macro F1-score of 0.575, which highlights persistent misclassifications among private car, e-scooter, and taxi trips. While its weighted metrics show better results—accuracy of 0.827 and recall of 0.723—this is largely due to the correct identification of majority classes, revealing ongoing challenges with the minority taxi class.

CB model presents mixed results. Its macro precision of 0.706 and macro recall of 0.725 suggest competent performance for balanced evaluations. However, the low weighted recall of 0.524 signifies difficulties with the minority taxi class and some misclassification of private car trips. The confusion matrix indicates that taxi trips are especially vulnerable to being misclassified as other modes, aligning with its low support.

In summary, the DT model emerges as the most balanced and reliable performer across all evaluation metrics. All four methods significantly surpassed the 54% success rate reported by Günay et al. [

21], who utilized the same dataset, but the DT model stands out as the most effective approach among those assessed in this study. Both ANN and RF achieved reasonable weighted scores yet struggled with minority classes, while CB performed well in macro-level metrics but remained sensitive to class imbalances in weighted evaluations.

6. Discussions and Conclusions

An online survey was conducted as part of the study, garnering responses from 512 participants, of whom 462 residents of Istanbul were included in the analysis. The survey comprised three sections: the first section collected demographic information about the participants, the second focused on e-scooter usage, and the third presented various scenarios along with questions regarding the transportation modes the participants would choose in those situations.

To develop predictive models for transportation mode choices based on demographic characteristics, e-scooter usage, and varying scenario conditions, we utilized methodologies such as ANN, DT, RF, and CB. All models significantly surpassed the 54% accuracy rate reported for discrete choice models by Günay et al. [

21], which utilized the same dataset. Among the models assessed, the Decision Tree (DT) exhibited the highest accuracy and overall performance, demonstrating its effectiveness in capturing travel mode preferences across diverse user types and scenarios.

The models developed are crucial in traffic simulation, particularly for analyzing the impacts of e-scooters on urban traffic patterns. They have the capability to generate synthetic populations and simulate distributions, thereby predicting transportation preferences under various conditions. The resulting outputs can be seamlessly integrated into traffic simulation software, enhancing our understanding and facilitating the evaluation of alternative future scenarios.

By adding a user-friendly interface, this model can become accessible to both central and local governments. It will help decision-makers predict how the public might react to strategic transportation or pricing policies. For example, it can show how transportation choices might change if public transit prices rise. Additionally, the model can evaluate the potential effects of initiatives aimed at increasing micromobility usage, especially for e-scooters, which can help reduce the negative environmental impacts of transportation. This makes the model a valuable tool for policymakers.

The intuitive interface will help companies that offer shared e-scooter services predict potential returns on investment. It can also help shape policies to improve customer satisfaction. This study used data from e-scooter users in Istanbul, but its methods and findings may be relevant to other urban areas. The model development process includes demographic information, specific travel times and costs for different modes, infrastructure conditions, and user perceptions. This approach offers a way to predict transportation mode preferences in cities with similar micromobility shares or those that are growing.

The impressive accuracy of machine learning methods, particularly DT, in forecasting mode choices indicates that these models can serve as dependable tools for public authorities and private micromobility providers. By applying the same survey design and model structure in different cities, the models can capture local user profiles, travel behaviors, and environmental factors. This strategy would enable cities to anticipate user responses to changes in pricing, infrastructure investments, or regulations.

Moreover, by incorporating additional variables such as population density, topography, and climate, future iterations of the model could be tailored for various urban settings. The outcomes from these models could be seamlessly integrated into traffic simulation platforms to evaluate policy scenarios and devise effective mobility strategies. Furthermore, developing a web-based, user-friendly interface would empower city officials and operators to explore the implications of various transportation decisions in real-time interactively.

Furthermore, future efforts will emphasize enhancing the interpretability of machine learning models. While this study has prioritized prediction accuracy, grasping the key factors influencing mode choice is still crucial. We intend to assess the impact of demographic, attitudinal, and scenario variables through feature importance analyses and other innovative or advanced machine learning techniques. This approach aims to deliver actionable insights while preserving robust predictive performance. Ultimately, this will enable decision-makers and micromobility providers to gain a clearer understanding of user behavior, informing both policy and operational strategies.

In conclusion, although this study is anchored in Istanbul, its methods and insights are broadly applicable and adaptable. Future research involving multi-city data collection and cross-validation will enhance the transition of this work into a robust, general-purpose micromobility planning tool. In future work, incorporating sustainability indicators—such as emission reduction, energy efficiency, and shared mobility potential—could further strengthen the link between user preferences and environmental outcomes.