Abstract

This study validates and applies a quantitative recommendation scale designed to assess the impact of strategies adopted by small and medium-sized aquaculture enterprises (SMEs) during the COVID-19 pandemic. A case study was conducted on the performance of two aquaculture models under crisis conditions: organized shrimp farms in Sinaloa (Mexico) and individual artisanal aquaculture SMEs in El Banco, Magdalena (Colombia). The methodological approach combined a cross-sectional survey, descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha, and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to evaluate the scale’s reliability and construct validity. Results from Sinaloa revealed strong positive correlations between productivity, market adaptation, technological adoption, and contingency strategies, with the highest association observed between contingency strategies and productivity (). In contrast, SMEs in El Banco exhibited lower integration of technologies and weaker links between strategic responses and productivity, reflecting structural constraints such as informality, limited institutional support, and reduced access to financing. The scale showed an acceptable but preliminary level of internal consistency () and acceptable factorial indices for an exploratory validation phase. Complementary convergent validity measures (CR and AVE) indicated low internal coherence, which reinforces the preliminary nature of the scale and the need for future refinement. Due to the heterogeneous nature and descriptive treatment of the Colombian data, the cross-country analysis is interpreted as exploratory rather than strictly statistical. Even so, the findings highlight that technological adoption, market diversification, and the implementation of health protocols were decisive for maintaining resilience and productivity during crisis scenarios. This research contributes theoretically, by providing initial evidence supporting an original measurement instrument, and practically, by offering policymakers and entrepreneurs a contextualized diagnostic tool to design evidence-based strategies that strengthen organizational resilience and sustainable productivity in aquaculture SMEs. Further validation in other regions and productive sectors is recommended to confirm the scale’s broader generalizability.

1. Introduction

In 2022, global aquaculture production reached 130.9 million tonnes, with an estimated value of $312.8 billion, accounting for 59% of the combined global fishery and aquaculture output. Within this landscape, inland aquaculture contributed 62.6% of farmed aquatic animals, while marine and coastal aquaculture contributed 37.4%; for the first time, aquatic animal production through aquaculture surpassed capture fisheries, with 94.4 million tonnes, equivalent to 51% of total global production and reaching a record 57% of the volume destined for human consumption. Despite these advances, aquaculture remains concentrated in a limited number of countries, while many low-income nations in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean have not fully realized their potential in this sector [1].

In the aquaculture sector, interventions are primarily aimed at improving productivity and/or producer income through at least four key strategies: (1) more efficient use of available resources and existing technologies, (2) the development and transfer of new technologies adapted to farmers, (3) increased utilization of production inputs, and (4) expansion of the area dedicated to aquaculture production [2]. However, the effectiveness of these interventions depends on their specificity and the context in which they are implemented. They can result in intermediate advances such as improved access to and use of inputs, technologies, financial and extension services, as well as the adoption of good aquaculture practices, such as more efficient pond management or improved marketing strategies.

These changes can be reflected in increased production volume, reduced waste, or improved quality and diversity of farmed products. Ultimately, the aggregate effect of these interventions should result in a more efficient market system with increased production, productivity, and profitability. This increase in performance can be expressed in a greater supply of aquaculture products for domestic consumption, higher sales income, or the strengthening of employment in the sector for fishermen, generating better salary and economic conditions for the communities involved [3].

The efficient management of productivity during health contingencies constitutes a significant challenge for small and medium-sized aquaculture enterprises, especially in regions such as the State of Sinaloa in Mexico, where aquaculture represents a key economic sector. In this context, the present research aims to design and validate a scale of recommendations aimed at optimizing labor productivity in health crisis scenarios, so that they can be adopted by aquaculture SMEs in order to maintain or improve their productivity during pandemic times, analyzing two different aquaculture models—organized (Sinaloa, Mexico) and individual (El Banco, Colombia)—to assess their performance and adaptive strategies during crisis scenarios. This study not only highlights the need to maintain the operational efficiency of aquaculture SMEs under adverse conditions but also seeks to offer practical and contextualized tools, adapted to the particularities of the aquaculture sector [4]. Problem Statement: Design and validation of a recommendation scale aimed at optimizing labor productivity in aquaculture companies during times of health contingencies.

The problem under investigation is that aquaculture has currently established itself as a priority activity in Mexico, contributing significantly to increasing healthy food production, strengthening regional economies, and improving the well-being of hundreds of thousands of families who depend directly or indirectly on this productive sector [5]. Similarly, this dynamic is observed in Colombia in various coastal towns in the north of the country, particularly in municipalities of the Magdalena department.

These areas have high aquaculture potential thanks to their geographic location, abundant water resources, and favorable environmental conditions for the cultivation of species such as shrimp and bocachico. In this context, micro-, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) dedicated to aquaculture in municipalities like El Banco find opportunities for productive development and local income generation, although they face limitations associated with informality, limited technology, and lack of access to financing and technical assistance [6,7]. This activity represents a strategic opportunity to respond to the growing demand for food with high standards of quality and sustainability, while boosting competitiveness in local, national, and international markets [8].

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the urgent need for companies, regardless of their economic sector, to develop effective mechanisms to preserve productivity in the face of health crises. In the case of the aquaculture sector, this need is heightened, as operational interruptions can seriously affect food security, the income of producer families, and employment associated with this value chain [9].

Small and medium-sized aquaculture businesses in the State of Sinaloa, Mexico, a region nationally and internationally recognized for its well-established industry, have not been immune to the impacts caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. During this period, these organizations faced unprecedented challenges, such as the temporary closure of facilities, shortages of inputs, supply chain disruptions, and mobility restrictions, which seriously compromised the continuity of their operations [10]. Maintaining labor productivity represented a particularly complex task [11]. However, recent studies in the Mexican aquaculture sector have shown that the timely and effective implementation of sanitary protocols, safety practices, and risk mitigation plans contributed positively to productive performance, even in adverse scenarios, as in the case of shrimp farming, where a significant effect on productivity was observed when adequate sanitary measures were adopted [12].

During the COVID-19 contingency, aquaculture SMEs in the municipality of El Banco (Magdalena, Colombia) faced multiple challenges similar to those reported nationally and globally. Most coastal fishing and aquaculture activities experienced a sharp contraction due to market closures, mobility restrictions, and disruptions in supply chains [13]. In El Banco (Magdalena Department, Colombia), these limitations led to a significant reduction in access to inputs, such as fingerlings and feed, as well as in marketing, affecting the operational continuity of farms. Informality and the lack of adequate infrastructure, also identified by the Colombian National Aquaculture and Fisheries Authority (AUNAP) as barriers to aquaculture formalization and development in Magdalena, hampered the implementation of crisis mitigation and adaptation strategies. However, subsequent initiatives, such as the opening of a satellite office of AUNAP in El Banco (Magdalena) and the inclusion of the municipality in the “Blue Route” to strengthen the governance and sustainability of the sector, reflect an institutional effort to support the recovery and revitalization of local aquaculture farms [14].

These results suggest that factors such as organizational flexibility, the strategic use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), and a solid market structure are crucial for the resilience and sustainability of aquaculture SMEs in crisis contexts. While the importance of structuring quality standards based on dimensions that promote user satisfaction is recognized, in practice there remains a considerable gap regarding the implementation of effective strategies for their application. In this sense, it is essential to develop measurement instruments that guarantee objectivity, reliability, and validity, in order to avoid biases that distort the final results [15].

Rigorous evaluation of the metric properties of these tools, such as internal consistency, construct validity, and precision, is essential to ensure an unbiased measurement of the phenomenon investigated by identifying its fundamental dimensions [16]. Since the central purpose of this type of measurement is to generate objective data that support informed and relevant decisions in organizational and educational contexts, it is equally important to consider the perceptions of workers and their alignment with the expected standards, as well as to evaluate the impact that these standards have on the learning and continuous improvement processes [17]. Therefore, it is necessary to precisely define the degree to which these standards contribute to the development of competencies and, based on this evaluation, design relevant interventions that strengthen the work or institutional environment.

During the health crisis caused by COVID-19, labor productivity was significantly affected in various economic sectors, including aquaculture. This situation highlighted the need for valid and reliable instruments that allow for objectively measuring the affected dimensions of productivity, as well as the strategies implemented to improve them [18]. In this context, the design and validation of specific scales is essential to generate valid and reliable data that support managerial decision-making and facilitate the implementation of effective strategies. These tools allow for the objective evaluation of complex constructs, facilitating the diagnosis of organizational strengths and weaknesses, as well as the design of appropriate interventions to improve labor efficiency and resilience [19]. Furthermore, content validity, based on expert judgment, and internal consistency of the instruments are key components to ensure the psychometric quality of the scales used in productive and social contexts [20]. Therefore, the present research focused on the development of a scale of recommendations aimed at optimizing labor productivity in small and medium-sized aquaculture companies during health crisis scenarios. The purpose was to offer leaders in the aquaculture sector practical, evidence-based tools that respond to their particular needs and strengthen the organizational capacity to adapt to future public health emergencies [4].

From a theoretical perspective, recent literature highlights that the resilience of small aquaculture and fisheries enterprises is shaped by four interrelated dimensions: social capital, organizational structure, access to institutional support, and the level of formality within productive activities. Global assessments of COVID-19 impacts on aquatic food systems show that producers with diversified operations, stronger networks, and more formalized business structures exhibit greater adaptive capacity during crises, while small-scale or informal units tend to experience higher vulnerability due to limited access to credit, insurance, market coordination, and public assistance [21,22]. Resilience therefore depends not only on internal capabilities—such as flexibility in production practices or the ability to reorganize labor and logistics—but also on the broader institutional environment that determines access to financial mitigation programs, transportation infrastructure, market channels, and policy support [21,23]. Importantly, structural heterogeneity and informality, particularly prevalent in Latin American fisheries and aquaculture systems, are not methodological flaws but defining characteristics of these socio-productive contexts. As demonstrated in recent analyses, contrasting organized aquaculture clusters with artisanal fishing communities provides meaningful insights into how different productive models mobilize resilience strategies, face institutional constraints, and experience uneven disruptions during COVID-19 [22,24]. These theoretical foundations justify the comparative design adopted in this study and explain why the structural differences between Mexico and Colombia are analytically significant rather than problematic.

2. Methodology

This research uses a quantitative approach, aimed at measuring the impact of certain recommendations on the productivity of aquaculture SMEs. This approach allows for the systematic collection and analysis of numerical data using standardized scales, in order to establish statistical relationships between variables such as productivity, resilience, and recommendation implementation, among others [25].

In the comparative analysis component between Sinaloa (Mexico) and El Banco (Colombia), the comparative approach is applied as a useful methodological technique in social sciences and law to contrast contexts, public policies, regulatory frameworks, and their influence on productive and organizational outcomes [26,27].

To strengthen the methodological foundations of this study, it is important to clarify that the comparative design employed here follows a contextual and interpretative logic commonly used in resilience research and institutional analysis. Recent methodological literature emphasizes that studies of resilience, institutional robustness, and socio-productive dynamics often involve heterogeneous cases whose differences are analytically meaningful rather than problematic [28,29]. Comparative analysis in such contexts does not aim to establish statistical equivalence between units, but to examine how distinct structural configurations, such as levels of informality, organizational complexity, and institutional support, shape adaptive responses under similar external shocks. As highlighted by emerging research on heterogeneous effects and socio-institutional systems, structural asymmetry between cases is intrinsic to the phenomena under study and may reveal important patterns of divergence and convergence in resilience trajectories [30]. Furthermore, comparative methodologies grounded in social and causal complexity show that cases embedded in different institutional and productive environments can be legitimately contrasted to identify mechanisms of emergence, adaptation, and vulnerability, even when statistical symmetry is not achievable [31]. In this sense, the comparison between organized aquaculture SMEs in Mexico and artisanal aquaculture and fishing producers in Colombia responds to a theory-driven logic of contextual comparison rather than to a requirement of sample equivalence, allowing the study to explore distinct resilience regimes shaped by different institutional and socio-productive conditions.

2.1. Sample Characteristics in the State of Sinaloa (Mexico)

This quantitative, non-experimental study, with a cross-sectional design and correlational approach, analyzed the composition and characteristics of 102 shrimp farms located in the state of Sinaloa, Mexico. All organizations included belong to the private sector. Regarding business size, a predominance of small companies was identified, representing 53.92% (), followed by medium-sized companies with 45.10% (), while only 0.98% () corresponded to a large company. This distribution is consistent with the business structure of the Mexican aquaculture sector, where small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) predominate, which face greater challenges in technological adoption and the professionalization of their processes [1].

Regarding the professional profile of the staff, a higher prevalence of graduates in general areas was observed (41.18%), suggesting a trend toward professionalization, although still with a non-specialized focus. Likewise, the significant presence of accountants (17.65%) and industrial or systems engineers (17.65%) reflects the growing importance of administrative management and the optimization of production processes in companies in the sector, essential elements for improving efficiency and competitiveness in demanding markets [32]. However, the low representation of professionals directly linked to aquaculture, such as biologists (8.82%) and aquaculturists (0.98%), highlights a potential gap in specialized technical expertise for the comprehensive management of shrimp farming. This deficiency could negatively impact key aspects such as the health, sustainability, and productivity of the production system [33].

2.2. Geographic Distribution and Age Profile

The geographic distribution of the shrimp farming companies analyzed shows a clear concentration in municipalities such as Ahome (34.31%), Cospita (16.67%), and Navolato Sur (15.69%). This strategic location suggests the existence of competitive advantages in these territories, such as proximity to fresh or brackish water bodies, favorable climatic conditions for shrimp farming, and the presence of adequate infrastructure for the development of aquaculture activities. Likewise, factors such as local and state public policies, the availability of land suitable for aquaculture, and access to technical or financial support services can significantly influence business concentration in certain regions [1,34].

Regarding the age profile of producers, a majority of aquaculture farmers are between 29 and 39 years old (45.1%), followed by those between 40 and 50 years old (31.37%). 19.61% did not report their age, while only 3.92% are between 51 and 60 years old. This distribution shows that the shrimp farming sector is being boosted by a young and middle-aged workforce, which represents an advantage in terms of the adoption of digital technologies, process innovation, and openness to organizational change [35]. However, the low representation of aquaculture farmers over 50 years old could reflect a limited intergenerational transmission of empirical and technical knowledge, which poses significant challenges for the long-term sustainability of sectoral knowledge [36].

2.3. Company Age and Sector Analysis

An analysis of the age of shrimp farming companies in Sinaloa reveals that a significant portion have managed to remain operational for between 11 and 20 years (57.84%), which could be interpreted as an indicator of relative stability and adaptability in a complex production environment. Meanwhile, the 21.57% of companies with more than 20 years of experience comprise an experienced business core, possibly more resilient to market fluctuations and recurring health or climate crises in the aquaculture sector [1]. Likewise, the presence of young companies, less than 10 years old, represents 20.58%, suggesting that the sector remains attractive to new ventures, although these emerging players may face greater economic, operational, and technical risks due to their limited accumulated experience [32]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the shrimp farming sector in the State of Sinaloa (Mexico) is characterized by its dynamism and its majority composition of small and medium-sized enterprises, which show a trend toward professionalization and technological development in their processes. However, deficiencies persist in specialized technical areas, particularly those related to biological management of the farm, which may compromise the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of the industry [33,34].

To strengthen the methodological clarity of the study, it is important to note that the comparison between Sinaloa (Mexico) and El Banco (Colombia) was not conceived as a statistical equivalence test but as a cross-contextual analytical strategy aligned with established principles in comparative public policy and socio-productive research. As highlighted by Nohlen [27] and Barreto and Lozano [26], comparative analyses in the social sciences may deliberately contrast heterogeneous units to examine how structural conditions—such as informality, institutional density, access to technology, and regulatory frameworks—shape adaptive responses and resilience trajectories. In this sense, the heterogeneity between the two study populations is analytically meaningful rather than problematic. The objective of the comparison is therefore exploratory: to identify convergences, divergences, and resilience mechanisms across distinct socio-productive regimes, rather than to infer causal differences based on parallel quantitative indicators. This approach is consistent with methodological traditions that emphasize contextual interpretation over statistical symmetry and supports the interpretative nature of the comparative findings presented in this study.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out in several stages, beginning with the evaluation of the normality of the variables through the analysis of kurtosis and skewness values, considering a range of standard deviations as an acceptable criterion, as suggested by some authors [37]. Subsequently, a descriptive analysis of the demographic characteristics of the sample was conducted, consisting of aquaculture companies that responded to a structured survey. To examine the reliability of the instruments used, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated, considered a standard indicator of the internal consistency of the scales, with values equal to or greater than 0.70 as acceptable [38].

Multivariate statistical analyses were then applied, including measures such as the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values, to describe the distribution of the data. As a central technique of the study, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to validate the underlying structure of the theoretical dimensions of the instrument and verify the validity of the construct [39]. To evaluate the fit of the factorial model, indicators widely accepted in the literature were used, such as the Chi-square statistic (), the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), following the criteria proposed in methodological studies [40]. Finally, Pearson correlation analyses were performed to examine the relationships between the main study variables. All statistical procedures were executed in the RStudio 4.2.0 programming environment, using the lavaan library for the estimation of structural equation models and semPlot for the graphical visualization of the structural model.

2.5. Sample in El Banco (Magdalena, Colombia)

In El Banco (Magdalena, Colombia), a sample of 200 artisanal fishermen was surveyed. These individuals live in communities such as the corregimientos of Aguaestrada, Algarrobal, Barranco de Chilloa, Caño de Palma, Menchiquejo, and Florida; as well as in the veredas of Garzón, Caimanera, Islitas, and Pueblo Nuevo. Respondents indicated that there are regulations for artisanal fishing in the Magdalena, Cauca, and San Jorge River basins that are applied in 81% of cases, but not in 19%. Similarly, minimum fish catch sizes were respected in 80% of cases, but not in 20%. Most of the respondents (91%) reported fishing for food daily, while 9% did not, and 7% indicated that they do not fish for sale.

As fishermen, they expressed interest in joining a Community School to ensure sustainable fishing practices, seeking access to adequate fishing gear and the transmission of knowledge to future generations. They estimated that such efforts would result in 86% sustainable fishing and 14% non-sustainable practices. Regarding species caught in the Ciénaga de Chilloa, respondents reported: catfish (17%), bocachico (29%), mojarra lora (17%), moncholo (14%), and others (23%). As for the type of gear used, they mentioned: cast net (31%), ralera/sweeper nets (8%), river trammel nets (35%), hook line (calandria, 9%), nasas (8%), and chinchorro (9%).

3. Results

This section develops the analysis categories defined as conceptual parameters of the specific objectives of this research, aimed at evaluating the impact of the recommendations for productivity in aquaculture SMEs in the face of the COVID-19 health crisis, in a comparative study between Sinaloa (Mexico) and El Banco (Magdalena, Colombia) [41].

The first category (A) focuses on the analysis of public regulations and policies—health, labor, commercial, and environmental—that directly influenced the response capacity of aquaculture SMEs to the health emergency in both countries, since it examines how these regulatory provisions facilitated or limited the operation of the sector during the pandemic, and to what extent companies managed to adapt to the established regulatory frameworks. The second category (B) presents the statistical analysis of the collected data, which empirically reinforces the socio-legal approach by showing how structural conditions, public policy measures, and the adaptive capacity of SMEs translate into measurable indicators of productivity, resilience, and crisis management. Finally, the third category (C) addresses the design, application, and validation of an original quantitative scale developed to measure the impact of recommendations implemented by Mexican aquaculture SMEs, compared with the practices adopted by their peers in Colombia. This methodological tool [42] allows for an objective and standardized comparison of the level of implementation of productive strategies and their effectiveness during the health crisis, providing valuable evidence for the design of future public policies differentiated by territorial context.

3.1. A: Examination of Public Regulations and Policies

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Mexican government adopted various public health regulations and policies aimed at preserving the continuity of strategic sectors, including aquaculture production. Aquaculture was recognized as an essential activity through the Agreement establishing extraordinary actions to address the health emergency [43], which allowed aquaculture SMEs to continue operating under strict biosafety measures. However, the implementation of health protocols—such as physical distancing, mandatory use of personal protective equipment, and constant sanitization—represented a challenge for many small businesses that lacked the technical and financial resources necessary to comply with these guidelines [44].

This situation particularly affected rural production units, which faced logistical obstacles, a lack of training, and limited institutional support, limiting their capacity to effectively adapt to the health crisis. In the labor and commercial spheres, Mexican aquaculture SMEs were also severely impacted by mobility restrictions, the temporary closure of local markets, and the decrease in international demand, which caused supply chain disruptions and difficulties in the distribution of aquaculture products. Although the federal government implemented support programs such as credits and tax deferrals, many aquaculture producers were unable to access these benefits due to their informality or lack of registration with official bodies. Regarding the environment, the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) maintained regulatory requirements for the use of water bodies in production [45], which further hampered the operations of those SMEs that faced pending procedures or legalization issues. In short, although public policies sought to mitigate the economic effects of the pandemic, their reach was limited in the aquaculture sector, revealing the need to design differentiated strategies that consider the heterogeneity, scale, and structural conditions of the country’s rural SMEs.

During the health emergency caused by COVID-19, aquaculture SMEs in the municipality of El Banco, Magdalena, Colombia, faced multiple challenges arising from the implementation of national health and labor regulations and public policies. Although the Colombian government recognized fishing and aquaculture as essential sectors through Decree 457 of 2020, in practice, many rural production units lacked the minimum conditions to implement the required biosafety protocols, such as the use of PPE, equipment disinfection, and social distancing [46]. The lack of institutional coordination and the limited presence of technical agencies in peripheral territories such as El Banco hindered access to timely information and specialized support. Furthermore, the prevailing informality in rural aquaculture employment limited the coverage of state support programs such as the Formal Employment Support Program (PAEF), excluding a significant number of workers and microentrepreneurs in the sector [47]. Regarding trade and environmental policies, aquaculture SMEs in the southern Magdalena River faced restrictions in the marketing chain, both due to the closure of local markets and the logistical difficulties of transporting inputs and products under restricted mobility conditions. Although entities such as the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Authority (AUNAP) attempted to keep productive activities operational through guidance and flexible procedures, their impact was uneven due to connectivity barriers, technological gaps, and poor business formalization [48]. On the other hand, the requirements of environmental regulations for the use of water resources and the management of discharges remained in force during the pandemic, generating operational difficulties for companies that were already facing sanctioning processes or unresolved requirements before regional environmental authorities [49]. This situation highlighted the need for public policies adapted to territorial realities and differentiated by production scales, which allow strengthening the technical and legal capacities of aquaculture SMEs in rural areas such as El Banco (Magdalena).

3.2. B: Statistical Analysis of Collected Data

This section presents the statistical analysis of the data collected through the application of a validated scale to small and medium-sized aquaculture enterprises in Mexico. This analysis aims to empirically reinforce the socio-legal approach adopted in the research by demonstrating how structural conditions, public policy measures implemented during the COVID-19 health emergency, and the adaptive capacity of productive organizations translate into quantifiable indicators of productivity, resilience, and crisis management.

Through descriptive statistical techniques, correlation tests, and confirmatory factor analysis, patterns of organizational behavior and differentiated responses to the regulatory and socioeconomic context are evident. These findings not only validate the measurement instrument but also provide solid evidence for understanding the relationships between law, public policy, and business performance in times of crisis.

The internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s ) obtained from the questionnaire applied in this study was 0.64, which is considered within a “questionable” range of reliability, particularly for an instrument in the validation phase [38]. Although this figure reflects a certain coherence between the items, it also indicates the need to enrich the instrument through a greater number of items, improve the thematic homogeneity, and expand the sample, in order to increase its power and psychometric stability [39]. Although the obtained value of Cronbach’s (0.64) is slightly below the conventional 0.70 threshold, it is considered acceptable for instruments under development and exploratory validation stages [38]. This result can be attributed to the limited number of items per dimension and to the heterogeneity of the analyzed sample. Therefore, the coefficient is interpreted as indicating an acceptable level of internal consistency for a newly developed scale, while suggesting the need for future refinement and retesting. To further investigate the instrument’s reliability, a bootstrap analysis was performed with 1000 replicates, estimating a 95% confidence interval for Cronbach’s , which ranged from 0.547 to 0.755. This procedure provides a more robust estimate of the actual reliability value, as it does not depend on strict assumptions of normality in the sample and allows for a better assessment of the coefficient’s precision [50]. Although the result places the alpha within the limits of what is acceptable, the interval suggests that, through adjustments and refinement, the instrument can achieve adequate levels of internal consistency.

The questionnaire used in this study consists of 20 items on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 4, designed to evaluate the strategies implemented by aquaculture companies during the COVID-19 contingency [51]. The use of an even-numbered (four-point) Likert scale was intentional to encourage respondents to express a clear positive or negative position, avoiding neutral or undecided answers. Although odd-numbered scales are traditionally common, several studies in the social sciences have shown that even-numbered formats can provide valid and reliable data when the objective is to obtain more decisive responses [51,52]. The statistical results are summarized in Table 1, in which it is identified that the items corresponding to the strategies adopted during the pandemic show the lowest mean values, suggesting a lower adoption of these measures, while those associated with business productivity reach the highest scores, with averages close to 4, especially in question 3 [53].

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the recommendation scale for productivity during health contingencies.

These results are consistent with recent research highlighting how perceptions of productivity can remain relatively high even when mitigating strategies, such as the implementation of health protocols or operational reorganization, are applied to a limited extent [54]. This pattern reveals that, although companies perceive acceptable productive performance, there is a significant gap in the implementation of specific strategies to address the health crisis.

The results of the Pearson correlation analysis are summarized in Table 2, which shows the relationships between productivity, market, use of technologies, and contingency strategies. First, a strong positive correlation is observed between productivity and market share (), indicating that an increase in productivity levels is associated with improved market response or market share. This relationship is consistent with the economic logic that greater production capacity allows for more efficient demand response, strengthening a company’s commercial position.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation matrix between the main study variables.

Productivity also exhibits a strong positive correlation with the use of technology (), suggesting that companies that have incorporated advanced technological tools tend to achieve better production results, likely thanks to automation, process efficiency, and the reduction of operational errors. Notably, the strongest correlation was found between productivity and the strategies implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (), indicating a direct and robust relationship between adequate strategic management in the face of the health crisis and the maintenance—or even improvement—of business productivity. This finding reinforces the idea that an organization’s ability to adapt and respond to emergencies can directly impact economic performance.

Finally, a very high correlation is evident between the use of technologies and market presence (), suggesting that digital transformation not only has internal effects on efficiency but also on external competitiveness, facilitating access to new marketing channels, improved response times, and improved competitive positioning. Although the correlation between the market and COVID-19 strategies is positive and moderate (), this value suggests that companies that adapted their operations to address the pandemic managed to exert some influence on the market, although not as marked as in other dimensions. Similarly, the correlation between the use of technologies and COVID-19 strategies is also high (), indicating that organizations that integrated technological tools into their operational management were able to improve their response capacity to the health emergency. These relationships confirm that the capacity for technological adaptation was closely linked to the implementation of effective strategic measures in a crisis context.

Overall, the results of the correlation analysis reflect significant interactions between productivity, market, use of technologies, and pandemic strategies, suggesting that companies that effectively integrated these dimensions tended to show better overall performance and greater resilience to disruptive external factors. Recent studies confirm this trend [55] by identifying that many companies increased their productivity during the pandemic, particularly those that adopted digitalization and automation processes, despite registering drops in their sales. However, other authors [56] showed that, in aggregate terms, the total production of many companies decreased, especially in those whose processes were highly dependent on face-to-face work, which underlines the importance of digital transformation as a way to maintain efficiency in environments of high uncertainty.

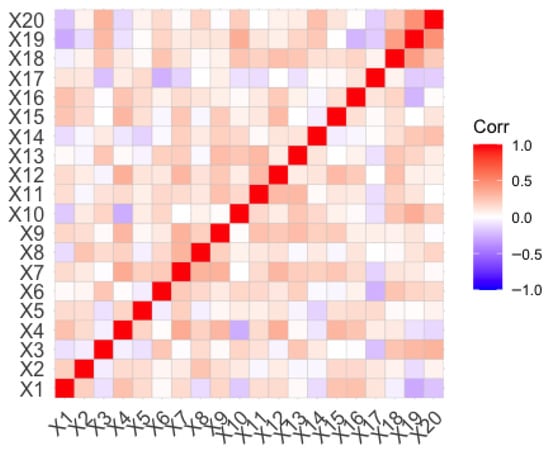

Figure 1 presents the correlation matrix between the 20 questionnaire items, intended to identify potential redundancies and ensure the integrity of the statistical model. This visualization allows us to observe which items show excessively high correlations with each other, which could indicate that they are assessing similar or repetitive constructs, generating risks of multicollinearity.

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix between the 20 questionnaire items applied to aquaculture SMEs.

Analyzing these correlations is essential to ensure that each item contributes in a unique and complementary way to the measurement of the phenomenon of interest, avoiding the overrepresentation of a single dimension. In this way, we seek to validate that the items adequately capture the diversity of factors involved in business strategies and their relationship with productivity, without compromising the robustness of the statistical model.

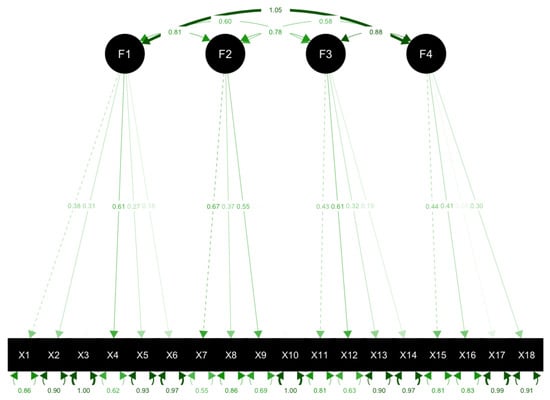

Figure 2 presents the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) applied to the proposed theoretical model. Items 19 and 20 were excluded to optimize the model structure and improve the identification of latent factors. This figure illustrates the model that analyzes the impact of the strategies adopted in response to the health emergency on the productivity of aquaculture SMEs in the State of Sinaloa, Mexico, as well as the interactions between the different items and dimensions evaluated.

Figure 2.

Model of the effect of COVID-19 strategies on aquaculture enterprises. Goodness-of-fit indices: (129 d.f.); ; GFI = 0.829; RMSEA = 0.067.

The results reveal a high positive correlation between the factors, particularly highlighting the relationship between contingency strategies and productivity, with a coefficient of 0.95, representing the strongest association in the model. This finding suggests that the implementation of specific strategies to address the pandemic had a significant effect on companies’ productive performance. Additionally, factors such as the market and the use of technologies also showed significant contributions to productivity, strengthening the validity of the proposed conceptual model.

Regarding factor loadings, diverse values are observed: for example, item 17 within factor F4: Contingency Strategies presents a low loading (0.08), which could indicate poor representativeness or the need to revise the item. In contrast, items such as X7, associated with factor F2: Market, showed high loadings, indicating a strong relationship with the construct to which they belong.

The model’s goodness-of-fit was assessed using various statistical indices. The chi-square statistic yielded a value of 187.559, with 129 degrees of freedom and a p-value < 0.0001, indicating that the model is statistically significant. Complementary fit indices, such as the GFI = 0.829 and the RMSEA = 0.067, are within acceptable ranges, suggesting that the model adequately represents the structural relationships between the factors and observed variables [39,57].

To complement the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), additional measures of convergent reliability were computed following [58]. Standardized factor loadings () and error variances () were obtained directly from the CFA model (Figure 2). The explained variance for each item was computed as . Table 3 presents the standardized loadings, error variances, and explained variance () for all items.

Table 3.

Standardized factor loadings (), error variances (), and explained variance () for each item of the recommendation scale.

Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were calculated using the following expressions [58].

Table 4 reports the CR and AVE values for the four latent factors. As expected in an exploratory validation phase, CR (0.30–0.45) and AVE (0.11–0.22) fell below conventional thresholds, which reflects the presence of several weak indicators (e.g., Item 17 = 0.08). These limitations have now been incorporated into the discussion and recommendations for future refinement of the scale.

Table 4.

Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for the four latent factors.

3.3. Comparative Results: Mexico vs. Colombia

Confirmatory factor analysis applied to aquaculture SMEs in the State of Sinaloa, Mexico, reveals a strong structure around the relationship between strategies to address the health crisis and productivity, with a significant correlation of 0.95 between these factors. This suggests a high capacity for organizational adaptation, likely facilitated by a more robust institutional environment, access to technologies, and more targeted sector policies [44]. Furthermore, market integration and the use of technologies showed similarly high correlations, demonstrating that many Sinaloa companies not only implemented biosafety protocols but also incorporated digital tools to maintain or even improve their operational performance during the crisis [59].

These findings reflect a business ecosystem that is better prepared and better resourced to confront disruptive events such as the pandemic. In contrast, aquaculture SMEs in El Banco, Magdalena, Colombia, although also recognized as part of the essential sector in Colombia (Decree 457 of 2020), faced structural limitations that affected their response to COVID-19. These limitations included lower technical skills, limited access to digital marketing channels, and a low level of business formalization, which hindered their participation in state financial or technical support programs [48]. Although individual adaptation efforts were identified, such as adjusting working hours and improving water resource management, no strong correlations were observed between the strategies implemented and productivity.

This contrast shows that, while there is a willingness to adapt in both contexts, institutional conditions, access to technology, and the articulation of differentiated public policies are determining factors in the effectiveness of business responses to health crises.

Given the heterogeneity of the populations analyzed, the comparative approach adopted in this study should be understood as exploratory rather than inferential. The Mexican sample represents organized aquaculture SMEs, while the Colombian data correspond mainly to artisanal fishing and small-scale aquaculture producers. Although these groups differ structurally, their inclusion provides complementary evidence on how various productive models within the aquaculture and fisheries sectors respond to crisis conditions, thus enriching the understanding of resilience and adaptive strategies across contexts.

It is important to note that the Colombian data did not undergo the same level of quantitative testing as the Mexican sample, particularly regarding Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and reliability assessment. Consequently, the comparative approach adopted in this study should be understood as exploratory rather than inferential. The Mexican sample represents organized aquaculture SMEs, while the Colombian data correspond mainly to artisanal fishing and small-scale aquaculture producers. Although these groups differ structurally, their inclusion provides complementary evidence on how various productive models within the aquaculture and fisheries sectors respond to crisis conditions. Despite these methodological differences, the contrast remains valuable for identifying shared adaptive strategies and resilience mechanisms across diverse socio-productive contexts, thus enriching the understanding of resilience and adaptive capacity across cases.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to validate a scale designed to assess recommendations aimed at improving productivity in small and medium-sized aquaculture enterprises (SMEs) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings show that the health crisis had a significant impact on the Sinaloa aquaculture industry, revealing a dynamic relationship between markets, technology adoption, and business productivity levels [56]. Furthermore, the results confirm the relevance of the strategies adopted during the health crisis to mitigate its negative effects, which is especially relevant in a sector exposed to external and unpredictable factors [60].

The validated scale also demonstrated adequate psychometric properties for application in a Spanish-speaking population, being effective in measuring key dimensions such as productivity, market management, technology use, and business resilience strategies [25,61]. However, it is essential to note that these strategies are not universally effective. The diversity of responses observed suggests that variables such as business size, geographic location, and access to financial and technological resources have a decisive impact on the effectiveness of the measures adopted, as is the case in the Municipality of El Banco in the Department of Magdalena, Colombia.

Recent international evidence reinforces the relevance of linking productivity and resilience in aquaculture SMEs. In Asia and Africa, Belton et al. documented how COVID-19 severely disrupted aquatic food value chains, yet enterprises responded through both reactive and proactive strategies, highlighting the importance of adaptive capacity for long-term sustainability [23]. Similarly, Kabir et al. found that resilience among Bangladeshi fish and shrimp value chain actors was shaped by diversification, scale, and vertical integration, but also showed that clustering could undermine resilience under covariate shocks [62]. In Africa, Brown-Webb demonstrated that South African aquaculture enterprises struggle to achieve self-sustainability without strong enabling environments, institutional support, and access to finance [63]. Relatedly, Mfono highlighted that medium-sized fishing aquaculture SMEs in the Eastern Cape build resilience through diversification, partnerships, and cost control, but remain constrained by regulatory and financial barriers [64]. From a European perspective, research has stressed that SME resilience depends on digitalization, supply chain adaptability, and sustainability policies aligned with carbon neutrality goals [65]. Compared with these global findings, our validated recommendation scale contributes by integrating technological, market, contingency, and regulatory dimensions into a single instrument, offering a comprehensive and operational framework applicable not only in Latin America but also adaptable to other regions and productive sectors facing systemic shocks.

Among the main limitations of this study is its geographic scope, focused exclusively on the State of Sinaloa in Mexico, which could restrict the possibility of generalizing the results to other regions with distinct economic and social characteristics, such as Colombia. Similarly, the use of cross-sectional data limits the ability to analyze the evolution of variables over time; therefore, the inclusion of longitudinal studies in future research is recommended to enrich the understanding of adaptation and change processes in crisis contexts [58].

The findings of this study indicate that aquaculture companies in the State of Sinaloa, Mexico, that adopted effective strategies during the pandemic and took advantage of diversified markets were able to significantly mitigate the adverse impacts of the health context, maintaining and even increasing their productive performance. In particular, a strong relationship was identified between market diversification and the strategic use of technologies, reflecting a synergy between innovation and organizational adaptation in contexts of high uncertainty [1,59]. Strengthening these capabilities enabled small and medium-sized enterprises (aquaculture SMEs) to respond with greater agility and resilience to the disruptions generated by the pandemic, especially in terms of operational continuity and productive sustainability.

In this context, the use of technologies emerged as a cross-cutting and determining component. Digitalization not only facilitated access to new markets and process automation, but also improved companies’ ability to manage resources and make data-driven decisions. Authors [66] argue that, following the outbreak of COVID-19, aquaculture SMEs that incorporated digital technologies were able to reduce costs, optimize inventory control, and maintain active relationships with customers and suppliers, factors that contributed to preserving and even improving their productivity. These findings are consistent with the results of this research, which observe that technological adoption was key to cushioning the negative effects of the crisis and consolidating a competitive advantage in the aquaculture sector in the State of Sinaloa, Mexico [58,67]. In this sense, the validation of the proposed scale provides a reliable and contextually relevant instrument for assessing productivity improvement strategies in aquaculture SMEs during crisis scenarios such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The evidence gathered highlights the decisive role of technological adoption, market diversification, and organizational adaptability in sustaining productivity under conditions of uncertainty. Although the findings are geographically limited to Sinaloa, Mexico, the comparative perspective with the Colombian aquaculture sector reinforces the importance of preparedness, digitalization, and resilience as key drivers of continuity and growth. Consequently, this study contributes both methodologically and empirically to understanding how aquaculture enterprises can strengthen their adaptive capacities to face future global disruptions.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the development and validation of a recommendation scale aimed at optimizing labor productivity in small and medium-sized aquaculture enterprises constitutes a significant contribution to organizational management in the context of a health crisis. This tool allows for the identification and strengthening of key dimensions such as the adoption of technologies, the implementation of health measures, market reconfiguration, and the design of contingency strategies, aspects that have proven to be interrelated and decisive in maintaining operations in emergency situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The empirical results provide preliminary evidence supporting the validity and reliability of the scale, indicating that it presents acceptable psychometric properties for application in the analyzed aquaculture context. However, its generalization to other populations or productive sectors should be approached with caution until further testing and validation are conducted. The scale not only facilitates internal evaluation of companies but also offers a framework for designing more effective and sustainable interventions. By identifying critical areas for improvement, this tool becomes a strategic resource for strengthening organizational resilience and fostering evidence-based decision-making.

Finally, this research highlights the need for specific tools to guide aquaculture SMEs in their adaptation to adverse contexts. As global crises, such as health and climate, become more frequent, it is essential to develop diagnostic tools that allow for anticipating risks and building adaptive organizational capacities. The proposed scale can be replicated and adjusted to other productive sectors, thus contributing to strengthening the business fabric and promoting an organizational culture prepared to face future scenarios of uncertainty.

The proposal and validation of an original quantitative scale has made it possible to rigorously measure the impact of the recommendations implemented by Mexican aquaculture SMEs in response to the health crisis generated by COVID-19, comparing these results with the experience of aquaculture SMEs in Colombia. This instrument represents a significant methodological advance, integrating key dimensions such as productivity, contingency strategies, the use of technologies, and market adaptation in highly vulnerable contexts. The comparison between the two countries has allowed us to identify structural similarities and contextual differences in the way organizations dealt with the effects of the pandemic.

The results obtained show that, while there are common strategies in Latin America—such as strengthening health protocols and digitizing processes—factors such as access to technological resources, the degree of business formalization, and institutional support differentially influence the effectiveness of these recommendations. The validated scale proved to be a reliable and applicable tool in diverse production contexts, allowing for clear correlations between the variables analyzed and facilitating a more precise diagnosis of aquaculture SMEs adaptive capacity in the face of health crises.

In summary, this scale not only constitutes an academic and technical contribution to the study of organizational resilience but also offers a practical tool for aquaculture SMEs and government agencies to design more efficient and contextualized action plans. The possibility of replicating this measurement in other production sectors and countries expands its usefulness as a comparative and continuous monitoring tool. In a global environment marked by uncertainty, having mechanisms that allow for objective evaluation of the impact of implemented recommendations and strategies becomes essential to strengthening business sustainability and regional food security.

5.1. Research Limitations

This research presents some methodological limitations that should be considered. First, the data were obtained through self-reports, which implies that the perceptions of aquaculture plant employees and owners may be influenced by subjective biases. Second, the restrictions imposed by social distancing during the pandemic made it difficult to access a large and representative sample, which limits the generalization of the results to other regions or productive sectors. Therefore, it is recommended that future research expand the sample size and consider the inclusion of other states, in order to enrich the understanding of the sectoral impacts of COVID-19 and validate the scale in different productive contexts.

Additionally, it is important to acknowledge that the study faced issues of relatively low scale reliability and non-comparable samples between contexts. Although the scale demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties in the Sinaloa sample, its reliability might decrease when applied across heterogeneous or adverse environments, which could introduce potential measurement errors. Moreover, the comparative analysis between aquaculture SMEs in Sinaloa (Mexico) and El Banco (Colombia) should be interpreted with caution due to structural differences in firm size, access to resources, and socio-economic characteristics. These contextual disparities may generate selection bias and limit the external validity and generalization of the conclusions.

Beyond these psychometric and sampling considerations, additional methodological constraints were also present during data collection. The use of self-reported data can introduce subjective perceptions, memory recall, and social desirability effects among aquaculture plant employees and owners. Furthermore, the restrictions derived from social distancing and mobility limitations during the COVID-19 pandemic constrained the research to access a larger and more representative sample. Despite these constraints, the study provides valuable empirical evidence and a validated measurement scale that can serve as a foundation for future investigations. It is recommended that subsequent research expand the sample size, include additional regions or countries, and incorporate longitudinal designs to assess the stability and evolution of these factors over time.

The additional analysis of Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) also revealed limited internal consistency and weak convergent validity for the current configuration of the scale. These results reflect the presence of poorly performing items (e.g., Item 17) and confirm that the measurement instrument is in an exploratory validation phase. Future research should refine problematic items, reassess construct dimensionality, and re-estimate the CFA to improve CR and AVE.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

While this study analyzed the impact of COVID-19 on productivity, markets, contingency strategies, and the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in shrimp aquaculture companies, it is important to recognize that other factors could significantly influence production processes. In this sense, future research should explore additional variables such as the impact of the pandemic on workers’ mental health, the socioeconomic implications in rural areas, and changes in labor and consumption dynamics. The results obtained here contribute to the improvement of organizational and production processes by highlighting the strategic role of organizational flexibility and technological innovation in the face of health crises. Furthermore, it identifies fertile ground for research into human behavior in the face of contingency situations, as well as the role of public policies in building organizational resilience and promoting territorial development.

5.3. Practical Contribution

The most significant practical contribution of this research lies in the design and validation of an original quantitative scale that allows for an objective and contextualized measurement of the impact of recommendations implemented by aquaculture SMEs in the face of health crises such as COVID-19. This tool represents a useful diagnostic instrument for entrepreneurs, sector technicians, and public policymakers, as it facilitates the identification of organizational strengths and weaknesses in key dimensions such as productivity, use of technologies, contingency strategies, and market adaptation. Having a validated instrument promotes evidence-based decision-making and optimizes resource allocation in emergency situations. Furthermore, the possibility of applying this scale in different geographical contexts—such as Mexico and Colombia in this comparative study—expands its practical relevance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.C.-E.; methodology, N.Y.T.-S. and G.E.B.-H.; validation, F.G.S.-V.; formal analysis, E.F.P.-T.; investigation, J.C.C.-E. and N.Y.T.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.C.-E.; writing—review and editing, E.R.-L., F.G.S.-V. and E.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it did not involve experiments with humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to privacy or institutional restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating aquaculture producers in Sinaloa (Mexico) and El Banco (Colombia) for their collaboration during data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SMEs | Small and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| GFI | Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: The Blue Transformation in Action; Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson, P.J.G.; Troell, M.; Banks, L.K.; Belton, B.; Beveridge, M.C.M.; Klinger, D.H.; Pelletier, N.; Phillips, M.J.; Tran, N. Interventions for improving the productivity and environmental performance of global aquaculture for future food security. One Earth 2021, 4, 1220–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime Muñiz, R.; del Río, J.A.J. The fishing and aquaculture production of Latin America with respect to the trade balance and foreign investment. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 10891–10908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Vera, L.; Chávez-Carreño, P. Diagnóstico de la Acuacultura en México; Fondo Mexicano Para la Conservación de la Naturaleza, A.C.: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Amezcua, F.; Soto, M.F. Current State of Aquaculture in México. Fisheries 2014, 39, 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. National Plan for Sustainable Aquaculture Development 2020–2030; Government of Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020.

- Ríos-Castaño, M.; Rodríguez, H.; Pérez, L. Diagnosis of aquaculture development in the Colombian Caribbean region: Challenges and opportunities. Colomb. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nava-Rogel, R.M.; Romero, S.I.M.; Huerta-Mata, J.J. Sostenibilidad ambiental en la acuicultura del centro de México: Factores que afectan su desarrollo. Rev. Esp. Estud. Agrosoc. Pesq. 2025, 265, 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.J.; Mamun, M.A.; Rahman, M.M. Impact of COVID-19 on aquaculture and fisheries in developing countries: Lessons for building resilience. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 22, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Technical Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Strategic Sectors: Aquaculture and Fisheries; Government of Mexico: Cuauhtémoc, Mexico, 2024.

- Ruiz-Velazco, J.M.J.; Estrada-Perez, M.; Estrada-Perez, N.; Hernández-Llamas, A. Estimating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on alternative semi-intensive shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) production schedules in Mexico: A stochastic bioeconomic approach. Aquac. Int. 2022, 30, 3107–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintergalen, D. Labor Productivity Management in Aquaculture Sectors During Pandemics: Lessons Learned; Universidad del Pacífico Press: Jesús María, Argentina, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. Impact and Repercussions of COVID-19 on the Ocean Economy and Trade Strategy; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Aquaculture and Fisheries Authority (AUNAP). Important Announcements to Strengthen the Fishing and Aquaculture Sector in the Middle Magdalena River; AUNAP statement; AUNAP: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024.

- Moreno Murcia, J.A.; de Paula Borges, L.; Huéscar Hernández, E. Design and validation of the Scale to Measure Aquatic Competence in Children (SMACC). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A. Statistics with Applications in R for Health Sciences; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Olivetti, J.K. The Psychometric Properties of the Professionalism Assessment Rating Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cano, F.; Enríquez-Espinoza, T.; Encinas-García, T.; Sánchez-Paz, A. Prevalence of the infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus in shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) broodstock in northwestern Mexico. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 117, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, M.M.; Shrotryia, V.; Dhanda, U. Scale development and content validity assessment for manufacturing performance: A Delphi based study. Int. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chhetri, D.B.; Khanal, B. A pilot study approach to assessing the reliability and validity of relevancy and efficacy survey scale. Janabhawana Res. J. 2024, 3, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Azra, M.N. Aquaculture Production and Value Chains in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2022, 9, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangano, M.C.; Berlino, M.; Corbari, L.; Milisenda, G.; Lucchese, M.; Terzo, S.; Bosch-Belmar, M.; Azaza, M.S.; Babarro, J.M.F.; Sarà, G.; et al. The Aquaculture Supply Chain in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: Vulnerability, Resilience, Solutions and Priorities at the Global Scale. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 127, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belton, B.; Rosen, L.; Middleton, L.; Ghazali, S.; Mamun, A.A.; Shieh, J.; Noronha, H.S.; Dhar, G.; Ilyas, M.; Thilsted, S.H.; et al. COVID-19 Impacts and Adaptations in Asia and Africa’s Aquatic Food Value Chains. Mar. Policy 2021, 129, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjelal, M.; Almajed, F.; Salman, A.M.; Alharbi, N.K.; Colangelo, M.; Michelotti, J.M.; Olinger, G.; Baker, M.; Hill, A.V.S.; Alaskar, A. COVID-19 vaccines: Global challenges and prospects forum recommendations. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 105, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Research Methodology, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto Rozo, A.; Lozano Rodríguez, E. (Eds.) Legal Research Methodologies: Experiences and Challenges of Legal Research; Ediciones Uniandes: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohlen, D. The Comparative Method in Political and Legal Sciences; National Autonomous University of Mexico: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zelčāne, E.; Pipere, A. Finding a path in a methodological jungle: A qualitative research of resilience. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2164948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rageth, L.; Caves, K.M.; Renold, U. Operationalizing institutions: A theoretical framework and methodological approach for assessing the robustness of social institutions. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 31, 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, D.R.; Cavallero, L.; Carranza, C.; Easdale, M.H.; Peri, P.L. Resilience management at the landscape level: Fostering mitigation and adaptations to global change based on forest socio-ecosystems. In Integrating Landscapes: Agroforestry for Biodiversity Conservation and Food Sovereignty; Montagnini, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrits, L.; Pagliarin, S. Social and Causal Complexity in Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Strategies to Account for Emergence. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.J.H. Articulación productiva para la innovación en las pequeñas empresas acuícolas de la región occidente de México. Ágora USB 2011, 11, 403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Canales, J.M. Technological capabilities for the adoption of new technologies in the agri-food sector of Mexico. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.; Herrera, R.; Cruz, F. Geographical and political factors that influence the location of aquaculture production units. Aquac. Lat. Am. 2019, 23, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Urías-Camacho, A.; Peinado Guevara, H.J.; Rodríguez-Montes de Oca, G.A.; Peinado-Guevara, V.M.; Herrera Barrientos, J.; Sánchez Alcalde, M.C.; González-Félix, G.K.; Cuadras-Berrelleza, A.A. Sustainable technological incorporation in aquaculture: Attitudinal and motivational perceptions of entrepreneurs in the Northwest region of Mexico. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Jeziorska-Biel, P.; Czapiewski, K. Between words: A generational discussion about farming knowledge sources. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 67, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schrepp, M. On the usage of Cronbach’s Alpha to measure reliability of UX scales. J. Usability Stud. 2020, 15, 246–261. [Google Scholar]

- McNeish, D.; Wolf, M.G. Dynamic fit index cutoffs for confirmatory factor analysis models. Psychol. Methods 2023, 28, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.M.; López Fernández, O. Lavaangui: A Web Based Graphical Interface for Specifying lavaan Models. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2024, 32, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Pérez, V.J.; Salinas-Martínez, J.A.; Vega Sánchez, V.; Zepeda-Velázquez, A.P.; Reyes-Rodríguez, N.E.; Gómez-de Anda, F.R.; De-laRosa Arana, J.L.; López-Rivera, M.I. Aquaculture and COVID-19: Impacts on the production of tilapia in the central zone of the State of Hidalgo, Mexico. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2025, 22, 34–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, G.M.M.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Kamal, M.A.S.; Khatun, M.N.; Bhandari, H. Impact of COVID 19 on Smallholder Aquaculture Farmers and Their Response Strategies: Empirical Evidence from Bangladesh. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOF. Agreement Establishing Extraordinary Actions to Address the Health Emergency Caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Virus; Official Gazette of the Federation: Abuja, Nigeria, 2020.

- SADER. Operating Guide for Food Production During the COVID-19 Health Emergency; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CONAPESCA. Annual Activities Report 2020–2021; National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021.

- Ministry of Health. General Biosafety Protocol to Mitigate the Risk of COVID-19 in Productive Sectors; Government of Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020.

- DNP. Review of Economic and Social Measures Against the Pandemic in COLOMBIA; National Planning Department: Parramatta, Australia, 2021.

- AUNAP. Institutional Management Report 2020–2021; National Aquaculture and Fisheries Authority: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021.

- CVS. Environmental Compliance Report in Aquaculture Units in the Colombian Caribbean; Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Sinú and San Jorge Valleys: Córdoba, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pfadt, J.M.; van den Bergh, D.; Sijtsma, K.; Moshagen, M.; Wagenmakers, E.J. Bayesian estimation of single-test reliability coefficients. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2021, 57, 620–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.; Abe, J. Using Likert type scales for measuring organizational adaptation strategies: Psychometric considerations. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmaryono, I.; Wijayanti, D.; Maharani, H.R. Number of response options, reliability, validity, and potential bias in the use of the likert scale education and social science research: A literature review. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2022, 8, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afşar Doğrusöz, L.; Yazıcı, S. Measuring organisational governance capacity in healthcare organisations: A scale development and validation study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, B.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H. Culture, institution, and COVID-19 first-response policy: A qualitative comparative analysis of thirty-one countries. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2021, 23, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, N.; El Herradi, M.; Sakha, S. Digitalization and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, N.; Bunn, P.; Chen, S.; Mizen, P.; Smietanka, P. The Impact of COVID-19 on Productivity; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Hwang, H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Cutoff criteria for overall model fit indexes in generalized structured component analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate data analysis: An overview. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 904–907. [Google Scholar]

- ECLAC. Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSMEs) in Latin America: An Overview; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean: Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano, C.; Rodríguez, M.; Pérez, L. Impact of COVID-19 on the productivity of SMEs in the primary sector in Mexico. J. Econ. Soc. 2020, 28, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R.I.; Khaled, M.N.B.; Narayanan, S.; Rashid, S. Shocks and the determinants of resilience: Fish and shrimp value chains in Bangladesh after Covid-19. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2023, 45, 1835–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Webb, N. Creating a model to develop self-sustainable aquaculture agribusiness enterprises in South Africa. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 29, 101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mfono, V.N. Investigating the Factors Influencing the Resilience of Medium-Sized Commercial Fishing Enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province. Master’s Thesis, Rhodes University, Eastern Cape, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Phuong, N.; Hashimoto, K.; Yusuf, A.; Phong, T.; Linh, H. SMEs and carbon neutrality in ASEAN: The need to revisit sustainability policies. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 413, 137699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.A. Technology and business productivity in times of pandemic: A perspective from SMEs. J. Bus. Sci. 2020, 12, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, F.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Márquez, D. Business resilience in aquaculture SMEs in the face of COVID-19: Analysis of adaptive strategies. Lat. Am. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 6, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).