Abstract

Eco-friendly farming, which minimizes chemical inputs, is critical for environmental sustainability but often exceeds the capacity of individual farmers, requiring collective action. This study examines how leadership facilitates collective adoption of eco-friendly practices in rural contexts, focusing on the Wufeng District Farmers’ Association in central Taiwan. Based on field observations and semi-structured interviews, the research identifies three key drivers: leaders’ shared vision and incentive mechanisms, technical support from the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute, and effective mobilization by production and marketing group leaders. Leaders functioned as managers and intermediaries, fostering cooperation, managing uncertainty, and encouraging innovation. Consequently, eco-friendly farmland expanded, and value-added products, such as rice-based wine, were developed. The findings highlight that adaptive and entrepreneurial leadership, combining transformational inspiration with transactional accountability, is essential to sustaining collective action and advancing long-term rural sustainability.

1. Introduction

In recent years, growing global concern over food safety and the resilience of agri-food systems has renewed interest in producing food that is both healthy and reliable. This trend has stimulated the expansion of farming approaches emphasizing natural processes and minimal chemical use. Among them, organic agriculture is widely viewed as a comprehensive model of sustainable farming that can generate environmental, economic, and social benefits under climate challenges [1,2,3]. Nevertheless, its widespread adoption remains difficult because of constraints such as regional production limits, complicated farm management, and demanding certification procedures. As a result, developing non-toxic or eco-friendly “natural farming” models may represent a more feasible starting point for the transition toward sustainable agriculture [4]. Although definitions vary, natural or eco-friendly farming generally refers to cultivation systems that avoid synthetic inputs, minimize tillage or weeding, and enhance soil fertility through biological processes. Yet, for conventional farmers accustomed to high-input production, shifting toward such practices poses major challenges.

Against this background, the present study investigates how leadership contributes to collective action in advancing eco-friendly farming, using the Wufeng District in central Taiwan as a case example. Wufeng demonstrates a locally driven process of agricultural change in which farmers, aware of the ecological harm caused by intensive practices, began to promote natural farming methods. This transformation required collective coordination rather than individual efforts, highlighting the essential role of leadership in mobilizing farmers, integrating fragmented plots, and aligning actions toward sustainability goals.

A central actor in this transition is the Director-General of the Wufeng Farmers’ Association (coded as FA1), who joined the association in 1995 and assumed the position in 2001. Responding to national discussions on food safety and ecological protection, he initiated the Five-Hectare Natural Farming Project (Wu-Jia-Di), which promoted the aromatic rice variety Tainung 71 (“Yihchuan aromatic rice”) in honor of Dr. Yihchuan Kuo [5]. Through financial incentives, the Association encouraged farmers to grow rice without chemical fertilizers or pesticides, aiming to restore the agro-ecological balance of the region. The initiative evolved as a community-based, bottom-up process, heavily relying on FA1’s capacity to mobilize participants, coordinate collective tasks, and navigate uncertainty. In subsequent years, government programs supplemented these grassroots efforts with external resources.

The Wu-Jia-Di case illustrates how entrepreneurial and adaptive leadership—combining vision, coordination, and resource integration—can foster institutional innovation within rural communities. Leaders functioned as intermediaries linking farmers with technical knowledge, funding, and market access, thereby reinforcing cooperation and eco-friendly production. Mechanisms such as contract arrangements and incentive pricing further supported the adoption of sustainable practices.

This paper aims to explore the key factors that facilitated the promotion of eco-friendly farming in Wufeng District, focusing on how adaptive and entrepreneurial leadership enabled collective action and sustained innovation. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews prior research on leadership, entrepreneurship, and collective action; Section 3 presents the research design and case background; Section 4 describes the transformation process in Wufeng; Section 5 analyzes leadership mechanisms, implementation challenges, and economic outcomes; and Section 6 concludes with implications for sustainable agricultural development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Eco-Friendly Farming

Since the Green Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, intensive conventional farming—marked by heavy use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides—has contributed to ecosystem degradation by disrupting soil microbial communities, reducing soil fertility, and causing water pollution and landscape deterioration [6,7,8]. To address these challenges, sustainable, eco-friendly farming practices are essential, aiming to reduce environmental impact and greenhouse gas emissions while enhancing soil and ecosystem health.

Eco-friendly farming “ensures healthy farming and healthy food for today and tomorrow, by protecting soil, water and climate, promotes biodiversity, and does not contaminate the environment with chemical inputs or genetic engineering” [9]. It also encourages crop diversity to support beneficial insects, reduce pesticide use, and improve overall ecosystem health, while prioritizing efficient resource use and maintaining soil fertility [10]. In essence, eco-friendly farming is a holistic system that balances productivity with environmental stewardship.

Successful adoption of eco-friendly practices depends on iterative learning, local adaptation, and socio-economic incentives [4,11]. Governments worldwide, including the European Union, have promoted measures such as reduced fertilizer use, no-tillage practices, and organic farming, often supported by financial subsidies to offset costs and encourage compliance [4].

In Taiwan, organic farming represents the most significant form of eco-friendly agriculture, although strict certification requirements and proximity to conventional farms often make immediate conversion challenging. Consequently, gradual transitions toward reduced chemical input or fully chemical-free cultivation are often more feasible pathways.

In Wufeng District, the Farmers’ Association has actively guided farmers in adopting eco-friendly practices [12]. Initiatives include eliminating chemical inputs, implementing crop rotation and fallow periods, supporting contract farming systems, and promoting environmental education. These efforts help farmers harmonize agricultural production with ecological processes, strengthen local environmental resilience, and foster community-based, sustainable farming systems. Importantly, this context provides a foundation to investigate how leadership and collective action. It links ecological goals with social and economic outcomes.

2.2. Leadership and Entrepreneurship in Collective Action

In the literature on collective action, leaders are individuals who mobilize resources, motivate commitments, identify opportunities, formulate strategies, express needs, and influence outcomes [13,14]. In this context, leaders embody the essence of entrepreneurship that drives social and economic development. Imaginative entrepreneurs can discover or create selective incentives to support moderate-sized and stable organizations, highlighting that imagination and creativity are key entrepreneurial traits [15].

Regarding system innovation in common resource management, public entrepreneurs expand collective action plans under uncertainty [16]. Similarly, social entrepreneurs provide solutions to social problems to create social value while recognizing the importance of economic value to sustain these initiatives. Economic results enable social entrepreneurs to accumulate sufficient financial resources to achieve their primary mission. Successful entrepreneurship also requires effective leadership, adequate resources, and smooth processes to generate new value [17].

Leadership plays a pivotal role in motivating followers, mobilizing resources to accomplish organizational goals, and promoting innovation, adaptability, and performance across national, organizational, and community levels [18,19]. Leadership can be classified into transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire styles, which continue to inform models linking leadership to organizational outcomes [19,20]. Local leaders typically adopt transformational or transactional styles, with laissez-faire leadership largely absent in collective action contexts.

Transformational leadership emphasizes vision, intellectual stimulation, individualized consideration, and inspirational motivation, fostering follower commitment that transcends personal interests and facilitates organizational change [19,20,21]. Transactional leadership is results-oriented, grounded in clear task expectations, contingent rewards, and active or passive monitoring to ensure compliance and performance [22,23,24]. Transfor-sactional leadership combines elements of both transformational and transactional approaches, aligning visionary guidance with performance oversight [25].

Adaptive leadership complements these models by focusing on complex, rapidly changing contexts, where uncertainty, multiple stakeholder interests, and evolving challenges require flexible, context-sensitive strategies [26]. According to Heifetz (1994) [27] and subsequent literature, adaptive leadership is and subsequent adaptive leadership scholarship, adaptive leadership is not defined by leader traits but by a set of practices that enable people to address complex, value-laden challenges. These practices include: [21,27,28]:

- Flexibility and problem-solving: adjusting strategies based on situational demands and emerging obstacles

- Context awareness: understanding the socio-ecological and institutional environment

- Empathy and stakeholder engagement: incorporating diverse perspectives to facilitate collective decision-making

- Transparent communication: maintaining trust and clarity in the face of ambiguity

- Commitment to innovation and learning: fostering experimentation and adaptive change

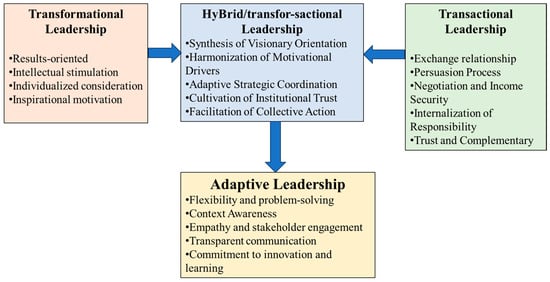

Adaptive leadership interacts with transformational, transactional, and transfor-sactional leadership by providing the mechanisms needed to navigate complexity, reconcile competing interests, and sustain both long-term vision and operational accountability. Whereas transformational leaders articulate shared purpose and transactional leaders ensure performance through structured incentives, adaptive leaders diagnose emerging challenges, mobilize collective problem-solving, and adjust strategies in real time. In this study, the Wufeng District case illustrates these dynamics: local leaders balanced transformational vision (revitalizing rural industries), transactional elements (coordinating responsibilities, monitoring progress), and adaptive responses to shifting resource constraints, stakeholder needs, and uncertain market conditions. These interactions are summarized in the conceptual framework (Figure 1), which provides the analytical foundation for understanding leadership practices discussed in Section 5, where the Wufeng case demonstrates how transformational and transactional dimensions become intertwined within adaptive, context-specific leadership processes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating the integration of transformational, transactional, transfor-sactional, and adaptive leadership in collective action contexts.

These international and theoretical perspectives provide a foundation for understanding how leadership functions in context-specific settings, such as Taiwanese farmers’ associations, where institutional, social, and market dynamics intersect to shape collective action outcomes. This framework will be directly applied in Section 2.3 to analyze hybrid leadership in eco-friendly agricultural transitions, including policy-driven and multi-regional examples.

2.3. International and Taiwan-Specific Insights on Leadership in Eco-Friendly Agricultural Transitions

International research underscores that leadership is central to enabling eco-friendly farming transitions in contexts marked by land reallocation, institutional voids, and market constraints [10,29,30,31]. As outlined in Section 2.2, transformational leadership fosters shared environmental values, experimentation, and farmer innovation [32,33,34,35], whereas transactional leadership ensures procedural stability, compliance, and equitable distribution of risks and benefits [34,35,36,37]. Adaptive and transfor-sactional leadership models explain how leaders integrate vision with pragmatic coordination, continuously adjusting strategies as ecological, institutional, or market conditions shift [21,25,26,27,28,29]. These strands of research converge to support a hybrid leadership perspective in understanding how leaders mobilize farmers, coordinate resources, and sustain eco-friendly farming initiatives across diverse socio-ecological settings. Leadership in this context also encompasses social and economic entrepreneurial traits, enabling leaders to identify opportunities, mobilize resources, negotiate with stakeholders, and innovate both technically and organizationally. Empirical studies highlight that distributed and network-based leadership strengthens institutional resilience, knowledge sharing, and competitiveness in agricultural systems [29,30,38].

In the context of Taiwan, local Farmers’ Associations provide a tangible example of leadership driving agricultural innovation. Sun (2023) demonstrates how association leaders implemented innovative management strategies to repurpose idle grain warehouse spaces, facilitating both organizational transformation and community-level agricultural development [39]. Lee et al. (2026) illustrate how the Satoyama Partnership in Wufeng leveraged multi-stakeholder collaboration and adaptive leadership to achieve sustainable transformation in the rice industry while protecting ecosystem services [32]. Cao et al. (2023) show that multi-layered leadership structures, including general managers, mid-tier staff, and production–marketing coordinators, are essential for coordinating irrigation collective action and maintaining compliance under fragmented land and institutional conditions [31]. Similarly, Chi et al. (2023) provide empirical evidence from Taiwan that farmers’ organizations enhance competitiveness through effective leadership, business policy, and organizational coordination [38]. Together, these cases collectively show that leadership not only motivates collective participation but also adapts practices to local institutional, ecological, and market constraints [31].

Following the promulgation of the Organic Agriculture Promotion Act in 2019, farmers’ associations became eligible—upon official review—to be certified as “eco-friendly farming groups” responsible for promoting agricultural practices that comply with environmentally friendly cultivation principles. Beyond the Wufeng Farmers’ Association, several associations in Chiayi, Changhua, Hualien, Yunlin, and Taitung have already received accreditation under this framework [40]. This nationwide expansion provides empirical support for the leadership models described in Section 2.2: transformational elements appear in vision setting and farmer motivation, while transactional mechanisms underpin certification compliance, recordkeeping, and incentive allocation [32,33,39], whereas transactional mechanisms guide certification compliance, recordkeeping, and incentive allocation [31,32,33,34,35,36,38]. These developments illustrate how policy shifts facilitate cross-regional collective action and institutional coordination.

Leadership in these associations is multi-layered: general managers formulate strategic directions; mid-tier staff provide operational coordination; and production–marketing coordinators directly interface with farmers to build trust, facilitate knowledge transfer, and maintain production quality. Transformational elements are evident in vision setting and farmer motivation [33,35], whereas transactional mechanisms guide certification compliance, recordkeeping, and incentive allocation [31,33,35]. Leaders also exhibit social entrepreneurship traits, such as building networks, fostering collective norms, and enhancing community engagement, and economic entrepreneurship traits, including resource mobilization, innovation adoption, and market-oriented strategies. Empirical studies after 2018 highlight how distributed and network-based leadership strengthens innovation capacity, institutional resilience, and agricultural competitiveness [40,41,42]. Comparative analyses across different rural regions reveal that leadership effectiveness is context-sensitive—shaped by local institutional arrangements, farmer networks, and resource availability—echoing the adaptive leadership dynamics detailed in Section 2.2.

Recent studies emphasize that collective action in eco-friendly farming is driven not only by economic incentives but also by relational factors such as trust, reciprocity, and shared norms [35]. Farmers’ associations reduce uncertainties associated with eco-friendly practices by offering coordinated production planning, technical assistance, environmental education, and risk-sharing mechanisms. These institutional supports create conditions where hybrid leadership—combining vision, accountability, and adaptive coordination—effectively mobilizes farmers toward sustainable practices.

However, challenges remain in the practical implementation of organic agriculture. Chen (2020) [43] studied the Xingjian Organic Cooperative in Sanxing, Yilan, which aimed to establish an organic promotion zone but faced contamination risks from adjacent conventional fields due to insufficient buffer strips. The study also found that noncompliance among cooperative members undermined the effective operation of the cooperative [43].

A more recent example from southern Taiwan further underscores these vulnerabilities. The Zhongqi Organic Agriculture Promotion Zone in Kaohsiung was formally designated for organic development yet subsequently displaced in 2023 due to the expansion of the Qiaotou Science Park, forcing farmers to relocate to the Yanchao Organic Agriculture Park [44]. Despite significant long-term investment in soil management and ecological restoration, the promotion zone lacked adequate institutional protection when confronted with competing industrial land-use priorities. This case demonstrates that even well-established organic zones remain precarious without stronger cross-sector coordination, long-term land security, and policy instruments that safeguard agricultural land against higher-value development pressures.

These local cases mirror broader structural issues identified in national policy analyses. As Liu (2025) [45] notes, existing sustainability-oriented initiatives in Taiwan remain limited in scale, lack long-term institutional and financial support, and suffer from weak cross-ministerial coordination. Such constraints restrict the stability and effectiveness of eco-friendly farming initiatives at the local level [45].

In contrast, the Wufeng case reflects this combination of opportunities and constraints. Its eco-friendly rice transformation demonstrates how institutional coordination, technical support systems, and farmer mobilization were orchestrated through leaders who enacted complementary transformational, transactional, and adaptive roles—precisely as the outlined in Section 2.2 [29]. Consistent with Fulton and Giannakas’s (2013) [29] analysis, leadership in Wufeng required not only the articulation of a shared environmental vision and the enforcement of necessary production standards, but also the social and economic entrepreneurial capacities of leaders enabled them to navigate organizational, environmental and market challenges effectively [29,45]. Integrating international and Taiwan-specific literature, including Chen’s (2020) case [43], the Zhongqi experience, reinforces the need for a hybrid leadership lens to understand eco-friendly agricultural transitions and highlights concrete organizational and environmental challenges that must be addressed for sustainable implementation.

These findings also highlight the role of relational factors—trust, reciprocity, and shared norms—in facilitating eco-friendly farming. Farmers’ associations reduce uncertainties by coordinating production planning, providing technical assistance, fostering environmental education, and offering risk-sharing mechanisms [32,35]. Such institutional support creates enabling conditions in which hybrid leadership—combining vision, accountability, and adaptive coordination—mobilizes farmers toward sustainable practices.

Taken together, the post-2018 literature and Taiwan-specific cases illustrate both the strengths and limitations of current leadership models in eco-friendly agricultural transitions. While hybrid leadership emerges as a consistent enabler of collective action, gaps remain in understanding cross-regional scalability, policy-driven institutional coordination, and long-term sustainability of farmer networks. These insights justify the selection of the Wufeng District as a case study and underscore the need to examine context-specific leadership mechanisms that effectively integrate transformational, transactional, and adaptive elements across multiple socio-ecological settings.

3. Research Methods and Case Background

3.1. Research Methodology

This study employed a single case study approach to gain an in-depth understanding of the contextual and characteristic features of the Wufeng District case. By elaborating and comparing relevant theoretical frameworks, the study further investigates the role of leadership in facilitating collective action toward eco-friendly farming. The semi-structured in-depth interview served as the primary source of empirical data, supplemented by secondary documentary materials.

3.1.1. Data Collection

- 1.

- Sampling strategy and participant selection.This study adopted a purposive and role-based sampling strategy, selecting participants who were directly involved in the promotion, coordination, or implementation of eco-friendly farming initiatives in the Wufeng District. Data saturation was achieved after several interviews, as later participants largely reiterated previously observed themes, and no new insights emerged across leadership, coordination, and implementation domains, indicating that the sample size of sixteen participants was sufficient to capture relevant perspectives. The purposive sampling approach ensured the inclusion of information-rich cases representing diverse organizational roles, decision-making levels, and on-the-ground experiences relevant to the study objectives.To ensure diverse stakeholder representation, participants were selected across multiple institutional and operational levels: leadership (Director General, department chiefs), technical and coordination staff (section chiefs and coordinators), and farmer group leaders and members. Certain groups, such as small non-participating farmers or local consumers, were excluded because they were not directly involved in collective decision-making or implementation processes and including them would not provide relevant insights into leadership and collective action dynamics. The selection strategy therefore ensured adequate depth, relevance, and diversity for examining leadership mechanisms in collective eco-friendly farming.A total of sixteen key participants were interviewed, comprising:

- The Director General (General Secretary) of the Wufeng Farmers’ Association.

- The Chief of the Promotion Department and five section chiefs or staff members responsible for eco-friendly farming promotion within the Farmers’ Association.

- The Convener of the Azhaowu Natural Farming Group; former researcher at the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute and former Chairman of the Community Development Association.

- Six farmer members, including the leader, deputy leader, cadre members, and general members of the Agricultural Production and Marketing Group.

- 2.

- Sampling strategy and participant selection.Potential participants were first identified through institutional contacts and public documents. After receiving an invitation and a consent form, participants scheduled interviews at their convenience.The observation and data collection period extended from November 2016 to October 2025. Several key informants were interviewed more than once to capture evolving perspectives and institutional dynamics, while the farmer group members participated in three rounds of focus group or individual interviews. Each interview lasted approximately 1.5 to 3 h.

- 3.

- Interview guide and thematic designA semi-structured interview guide (Appendix A) was developed in advance to ensure consistency while allowing flexibility for probing. Questions were adjusted dynamically based on participants’ responses to encourage deeper reflection and clarification. The interview topics were organized around four main themes:

- 1.

- Characteristics and roles of leaders at different levels.

- 2.

- Factors that trigger the initiation of collective action.

- 3.

- Strategies for overcoming obstacles.

- 4.

- Influence of external and institutional environments.

- 4.

- Temporal tracing and data triangulation.To capture the temporal evolution of leadership, interviews were time-stamped and organized chronologically. Data from multiple time points were compared to identify changes in leadership roles, organizational processes, and stakeholder collaboration. Secondary sources—including official documents, meeting minutes, and evaluation reports—were used to triangulate interview findings and verify longitudinal consistency.

- 5.

- Ethical considerations and anonymization.All participants provided informed consent before participation. To protect participants’ privacy and comply with research ethics, all interviewees were anonymized using identification codes. Codes were assigned according to institutional affiliation:

- FA1–FA7 for Farmers’ Association staff;

- FM1–FM6 for farmer members;

- GO1 for the village head;

- AR1–AR2 for researchers from the Agricultural Research Institute.

These anonymized codes are consistently used throughout the analysis and quotations to ensure confidentiality while maintaining analytical clarity.In addition to the interview data, secondary sources —including official documents of the Farmers’ Association, meeting minutes, and relevant evaluation reports, which were used to supplement and triangulate the primary interview findings.All participants provided informed consent before participation. Personally identifiable information was removed during transcription and analysis to maintain anonymity and uphold research ethics. The study involved multiple stakeholders, including Farmers’ Association staff (FA1–FA7), farmer members (FM1–FM6), local village heads (GO1), and Agricultural Research Institute researchers (AR1–AR2), as summarized in Appendix B. Additional details on the interview questions and coding framework are provided in Appendix C.

3.1.2. Data Analysis

The qualitative data were analyzed through a systematic and rigorous process to ensure analytical transparency, validity, and reliability. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed repeatedly to achieve a comprehensive understanding of participants’ narratives and to identify recurring expressions, actions, and events relevant to the research questions.

Following transcription, each transcript was coded using the anonymized participant identifiers (FA, FM, GO, and AR) as described in Section 3.1.1. This ensured traceability of perspectives across different organizational and professional backgrounds while maintaining confidentiality.

The study adopted the hybrid thematic analysis method developed by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane [46], which integrates both inductive and deductive analytical approaches. This method allows the researchers to interpret the data through predefined theoretical frameworks while remaining open to emergent, data-driven themes.

All interview recordings were first transcribed verbatim, and the transcripts were read repeatedly to gain familiarity with the data and identify recurring expressions, actions, or events relevant to the research objectives.

During the initial coding stage, meaningful text segments were identified and labeled with preliminary codes that captured core ideas or patterns. These codes were compared iteratively across participants (e.g., FA1–FA7, FM1–FM6, GO1, and AR1–AR2) to detect both convergent and divergent viewpoints regarding leadership roles and collective action processes.

Subsequently, thematic categorization was conducted to integrate these codes into broader conceptual themes aligned with the analytical framework, including:

- Leadership characteristics,

- Triggering factors of collective action,

- Strategies for overcoming obstacles, and

- External and institutional influences.

To enhance robustness and reliability, two researchers cross-checked a subset of transcripts, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion of the findings, data triangulation was performed by cross-verifying findings with secondary materials such as meeting minutes, Farmers’ Association reports, and government documents. This triangulation strengthened the credibility and validity of the interpretations.

Finally, the analytical results were organized systematically to facilitate subsequent discussion and theoretical reflection. This iterative and evidence-based process ensured that the study’s conclusions were firmly grounded in the empirical data collected from the Wufeng District case.

3.2. Background of Case Study

3.2.1. The Cradle of Rice Seeds: The Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute

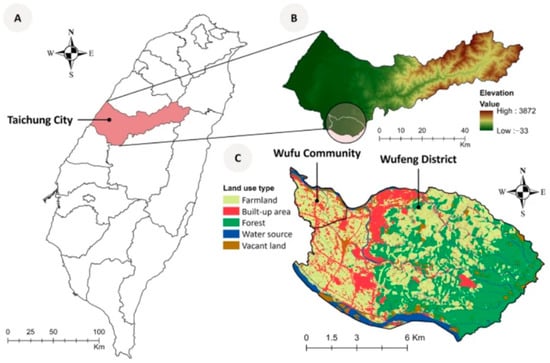

The study area, Wufeng District of Taichung City, central Taiwan, is shown in Figure 2. The map, reproduced from Lee et al. (2026) under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, illustrates the spatial distribution of farmland, built-up areas, forests, and water resources in the Wufu Community [32]. The district is geographically divided by Highway No. 3 into two halves [47]:

Figure 2.

Location of the study area: Wufeng District and Wufu Community, Taichung City, Taiwan. Source: Lee, C.Y. et al. (2026) [32], reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Note: (A) Taichung City in central Taiwan (magenta). (B) Wufeng District in the southwestern part of Taichung City, showing elevation: highlands in brown (up to 3872 m) and lowlands in green (down to −33 m). (C) Land use: farmland (yellow), built-up areas (red), forest (green), water bodies (blue), and vacant land (brown). Farmland and forest dominate, built-up areas are scattered, and water bodies follow river courses.

- Eastern Wufeng: Characterized by mountainous terrain, including the Huoyan Mountain Range and Jiujiu Peak. Agriculture in this area primarily focuses on fruit tree cultivation due to hillside terrain and limited water resources.

- Western Wufeng: A plain area traversed by a tributary of the Wu/Wuxi River, forming an alluvial delta suitable for farmland. This region supports double-harvest-a-year rice cultivation due to adequate water supply.

The district receives an annual rainfall of 1400–1665 mm, with an average temperature of approximately 22.5 °C.

The Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute (TARI), located in Wufeng District, plays a pivotal role in rice variety research and development. In 1992, Dr. Kuo Yih-chuan led a research team engaged in rice breeding. In 2000, the team successfully cultivated the aromatic rice variety “Tainung 71”, developed by hybridizing the native Taikeng 4 and the Japanese Kinuhikari (“Junguand”). This variety exhibits high eating quality with a taro-scented flavor, short, round, and plump grains, excellent appearance, drought tolerance, and strong resistance to pests and diseases. Former President Chen Shui-bian officially named the variety “Yihchuan Aromatic Rice” in honor of Dr. Kuo’s efforts, marking the first rice variety in Taiwan with both a commercial and personal name [5].

3.2.2. Enlightenment of Agricultural Transformation: Azhaowu Natural Farming Group

The Azhaowu Natural Farming Group is an informal organization composed of smallholder farmers focused on sustainable, people-centered agricultural development. Their efforts began in the Wufeng District but also involved farmers from surrounding areas such as Nantou, Wuri, Taiping, and Dali.

The group embraces natural (ecological) farming methods, with the fundamental principle of no chemical pesticides (natural or organic materials are used when necessary), no chemical fertilizers, and no herbicides. They employ methods like “organic cultivation” and the more stringent “Humei (Xiu Ming) Natural Farming,” which also prohibits fertilizers.

The group’s leader, R1, a former TARI employee and later a university faculty member, was prompted by the destruction of the natural ecological environment caused by conventional farming. While serving as chairman of the Gio-cheng (Jiuzheng) Community Development Association in 2011, R1 began actively promoting natural farming techniques in the community.

A key development occurred in 2014, when the group received approval and subsidy from the Soil and Water Conservation Bureau of the Council of Agriculture for a Rural Rejuvenation Plan. This led to the “Natural Ecologic Farming of Paddy Rice Education Workshop,” which was attended by over 30 participants, including small farmers from various districts. The enthusiastic response prompted the participants and teachers to form the Azhaowu Natural Farming Group to share knowledge and achievements. By then, nearly half of the members were workshop participants, with diverse activities including planting rice (3 farmers), fruit trees (6 farmers), and vegetables (7 farmers), and processing agricultural products (5 members).

With the support of FA1, and FA2, the “Azhaowu Natural Farmers Market” was experimentally hosted at the Wufeng FA for six months starting on 1 July 2015. This market aimed to promote community-supported agriculture (CSA) and the philosophy of local production and local consumption, reducing the carbon footprint and promoting environmental protection. The “Taichung City Azhaowu Natural Farming Development Association” was formally established on 20 June 2018, to promote concepts of eco-friendly farming, local production, local consumption, and the weekly farmers’ market continues to operate [45,48].

3.2.3. Transformation of Wu-Jia-Di in Natural Farming: Promotion by Wufeng Farmers’ Association

In 2001, anticipating the potential impact of Taiwan’s accession to the WTO on local agriculture, the Wufeng Farmers’ Association established a rice production and marketing group the following year. The group promoted Yihchuan Aromatic Rice under a contract farming system to facilitate rice industry transformation. Over more than a decade, the cultivated area expanded from 7 hectares to nearly 300 hectares, establishing a strong brand and reputation.

The FA1, emphasized rice quality and production safety, contracting farmers at guaranteed prices above market rates to ensure high-quality output and increase farmer income. Inspired by the Humei (Xiu Ming) Natural Farming methods of the Azhaowu Natural Farming Group, the Wufeng FA launched a pilot rice area for eco-friendly farming, aiming to cultivate crops without chemical fertilizers, pesticides, or herbicides, thereby reducing environmental and ecological damage and raising public awareness of sustainable agriculture.

FA1 and colleagues explained the concepts of natural farming and encouraged farmer participation. Initially, willingness was low due to conventional farming habits, and eco-friendly fields required a buffer of over three meters from neighboring fields to avoid pesticide contamination.

After a year of outreach, advertising, and communication, the Wufeng Fammers’ Association, with mobilization by former leaders of the rice production group, secured higher-than-market contract prices and identified a five-hectare plot (Wu-Jia-Di) in Wufu Village. In 2015, the Wufeng Farmmers’ Association signed a contract with farmers to gradually adopt natural farming methods. This contract evolved into Natural Farming in 2016 and was later codified under the Eco-Friendly Farming in early 2019.

To institutionalize good farming practices, the Wufeng Farmers’ Association established the “Standards for Eco-Friendly Farming Practices” in 2018, specifying standards for production environment, education, crop management, soil and fertilization management, pest and weed control, and audit procedures. The Ministry of Agriculture certified the Wufeng Farmers’ Association as a Friendly Farming Promotion Group, with certification renewed through 2027 [39].

4. Case Study Analysis and Leaders of Collective Action

Based on in-depth interviews with the FA1, the Chief of the Promotion Department (FA2), researchers from the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute (R1), and the leaders of the rice production and marketing group (FM1, FM2), this section illustrates how different leadership roles and cooperative actions contributed to the transformation toward natural farming. The qualitative coding of interview data reveals three major dimensions that drive this transformation process.

4.1. Shaping Vision and Designing Incentive Mechanisms

Leaders often define a vision and communicate it in ways that inspire followers to pursue shared goals [49]. Effective leadership requires long-term strategic planning and the capacity to translate ideas into actionable objectives, enabling followers to understand values, challenges, and timeframes [23,49]. Leaders must also clearly articulate their visions to motivate action, even when outcomes remain uncertain [50].

Historically, due to the high quality of Yihchuan Aromatic Rice, the Wufeng Fammers’ Association offered high contract prices, leading farmers to overuse fertilizers and pesticides to increase yields. However, climate change, environmental degradation, and market competition in Taiwan forced the association to reconsider this model. FA1 began questioning whether “Yihchuan aromatic rice” could remain competitive in the next decade. He also realized that continuous use of chemical fertilizers would ultimately harm both the soil and crop health.

Through discussions with R1 from the TARI, FA1 realized the principles of natural farming. Collaborating with Chief of Promotion FA2, and group leaders FM1 and FM2, they drafted the “Wufeng Aromatic Rice 2.0 Plan,” which aimed to replace conventional farming with natural practices—eliminating synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides—to restore soil vitality and environmental quality.

FM1, now the Wufeng Fammers’ Association Chairperson, recalled:

“When the Director-General first told us about natural farming, it was hard to accept because of our long-term habits. But after ongoing discussions, we realized it was important to protect the environment. Together, we found fields suitable for this new method.”

FA1 also designed an incentive mechanism to ensure farmers’ income and participation:

“One of the tasks of the Farmers’ Association is to protect the rights and income of farmers. So we planned mechanisms to increase income, manage farmland effectively, and set clear rules for participation.”

The 2015 contract for Tainung 71 Non-toxic Aromatic Rice specified cultivation standards, variety, area, and compliance requirements. Farmers violating regulations could lose purchase eligibility. The Wufeng Fammers’ Assciation offered a guaranteed price of NT$18,000 per one-tenth hectare (NT$1,280 per 60 kg of wet grains). In 2016, the guarantee was revised to NT$14,000, with the Wufeng FA covering costs of organic fertilizers and biological pest control.

As FA1 explained:

“We shifted the production risk from farmers to the Wufeng Fammers’ Assciation. Farmers only pay basic costs such as soil preparation and transplanting, while the Wufeng Fammers’ Assciation provides organic fertilizers and pest control to reduce risks and maintain quality.”

In 2018, Wufeng Fammers’ Assciation was recognized as an Eco-Friendly Farming Promotion Group by the Council of Agriculture. That same year, Taiwan enacted the Organic Agriculture Promotion Act, reinforcing these efforts. Contracts were updated in 2019 to include disaster insurance and free supply of organic fertilizers and pest-control materials, further lowering farmers’ costs and risks. The certification period for the Wufeng Farmers’ Association eco-friendly farming recognition has been extended until 8 February 2027, ensuring continued support and oversight for participating farmers.

To address rodent infestations common in ecological farming, the Wufeng Farmers’ Association collaborated with the Wildlife Conservation Center at Pingtung University of Science and Technology to install bird perches that attract black-winged kites, achieving biological pest control and enhancing biodiversity [51]. The successful conservation initiative led Huang to brand the rice as “Black-Winged Kite Rice,” symbolizing the harmony between agriculture and ecology. According to Wufeng Farmers’ Association Carbon Footprint Study Report in 2025, the CAS Wufeng Aromatic Rice report, the overall Data Quality Rating (DQR) is classified as high quality, indicating that the promotion has achieved good effectiveness [52,53].

Although direct quantitative data on pesticide reduction, soil organic matter, or biodiversity were not collected in this study, Lee et al. (2026) found that maintaining ecological corridors 50–500 m wide supports movement, while reducing pesticide use by 30–50% enhances ecological health and sustainable land management [32]. Furthermore, life-cycle carbon footprint analysis provides quantitative evidence of environmental impact reduction. The total carbon footprint of Wufeng Organic Aromatic rice (5.10 kg CO2e) was lower than that of CAS Wufeng Aromatic Rice (6.50 kg CO2e), and the emission distribution indicates that organic cultivation reduces dependence on chemical and energy-intensive inputs in the raw material stage (49.24% vs. 79.73%). These findings quantitatively support the ecological benefits observed in the field and align with the biodiversity enhancement achieved through the black-winged kite conservation initiative [52,53].

4.2. Providing Cultivation Management and Expert Guidance from the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute

Successful collective action requires leaders to leverage institutional support and technical expertise. Since FA1 lacked natural farming experience, he sought assistance from agricultural researchers. Although R1 inspired FA1, he had retired from TARI, prompting collaboration with other experts, notably R2.

R2 had previously served on the Aromatic Rice Variety Tainung No. 71 project team. After the variety’s success, he promoted it further, emphasizing its resistance to pests and suitability for eco-friendly farming. At FA1’s request, R2 developed training programs on pesticide-free cultivation and natural farming education.

In 2015, under R2’s guidance, nine farmers in Wufu Village adopted non-toxic farming, establishing the first natural rice production area. The Wufeng Famers’ Association co-organized workshops and field visits to organic rice farms in Taichung’s Waipu and Dajia Districts to strengthen technical exchange.

A year later, a large demonstration workshop at Wu-Jjia-Di attracted hundreds of farmers. R2 emphasized that reliance on chemicals was no longer sustainable under global climate pressures, noting:

“The principles of natural farming are like health management—for both people and the land. It’s a dual healing process that ensures long-term sustainability.”

From 2015 to 2025, the contract required farmers to participate in training organized by the FA. To support this, the FA invited experts from the Council of Agriculture (now is Ministry of Agriculture), the Taichung District Agricultural Improvement Station, the Agricultural Research Institute, National Chung Hsing University, and the Changhua Wild Bird Society to provide guidance. These continuous efforts aim to improve cultivation practices, increase rice yields, and maintain a healthy environment.

4.3. Leadership and Mobilization by the Production and Marketing Group

Leadership, defined as “the process by which an individual influences a group to achieve common goals through mutual interaction” [21], was critical in the Wufeng case. While the Wufeng Farmers’ Association provided institutional support as external leaders, internal mobilization depended on the production and marketing group’s leadership.

FA2 first approached group leaders FM1and FM2 to discuss adopting natural farming. They began by coordinating with nearby farmers and selecting test fields in Wufu Village. FM1 recalled:

“Most farmers thought we were crazy to give up fertilizers and pesticides. They were worried about reduced yields and uncertain market prices.”

FM2 emphasized determination despite challenges:

“Nothing happens without action. We had to take the first step. In 2015, nine members joined, but cold weather caused low yields of 180–240 kg per tenth hectare. Without the Director-General’s persistence, we could not have continued.”

Under conventional farming, yields average 840–900 kg per tenth hectare, while natural farming averages 540–600 kg. Despite lower yields, the Association’s price guarantees made natural farming viable. When typhoons struck, natural farms experienced less damage than conventional ones. As FM2 explained:

“With natural farming, rice roots are stronger, and the plants resist storms better. The yield variation is smaller than in conventional systems, even under climate change.”

Beyond yield, farmers witnessed ecological recovery. FM1 observed:

“Since switching to natural farming, fireflies have returned, biodiversity has improved, and the air feels fresher. This reflects not only environmental recovery but a higher quality of life for rural residents.”

These findings reveal three key drivers of agricultural transformation: (1) visionary leadership and incentive mechanisms from the Farmers’ Association, (2) technical support from the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute, and (3) grassroots mobilization by production group leaders. Leadership thus emerges as the central factor enabling organizational effectiveness and successful collective action.

4.4. Leadership Evolution over Time

The leadership within the Wufeng community and association exhibited a clear evolution over the study period (November 2016–October 2025), responding dynamically to both community needs and organizational challenges. Based on semi-structured in-depth interviews with key stakeholders, we identified three main phases:

- 1.

- 2016–2018: Formation and Initial Mobilization

- The initial phase focused on organizing the association and establishing trust among farmers.

- Leaders played a coordinating role, bridging communication between community members and external authorities.

- Interview data highlighted early challenges, such as varying levels of engagement and limited resources.

- 2.

- 2019–2021: Consolidation and Project Implementation

- Leadership shifted toward facilitating collective action and implementing environmentally friendly farming practices.

- Leaders increasingly acted as mediators, providing guidance and resolving conflicts within the community.

- Semi-structured interviews captured stakeholders’ reflections on leadership strategies, illustrating how adaptive approaches were employed.

- 3.

- 2022–2025: Expansion and Institutional Integration

- Leadership roles further evolved to integrate long-term sustainability and institutional collaboration.

- Leaders focused on strategic planning, fostering partnerships, and promoting community-wide adoption of best practices.

- Follow-up interviews documented both successes and ongoing challenges, highlighting iterative adjustments in leadership approach.

The study employed a sequence of interviews, including initial in-depth discussions, mid-period follow-ups, and final reflections, ensuring temporal changes in leadership were captured. Participants were selected to represent diverse roles within the association and the broader community, allowing a comprehensive view of leadership evolution.

5. The Role of Leaders in Collective Action

Building upon the theoretical framework of “transfor-sactional leadership” introduced in Section 2.2, this section empirically examines how leadership in Wufeng integrates transformational vision with transactional coordination to promote eco-friendly rice farming. This hybrid approach reflects the adaptive capacity of rural leaders to translate long-term sustainability ideals into actionable programs through institutional incentives, network mobilization, and participatory engagement.

Regarding the key role of leadership in collective action, Lobo et al. (2016) [14] identified two main dimensions: the centrality of leaders and leaders as functional brokers. The first emphasizes leader’s importance in fulfilling members’ needs and mobilizing efforts to achieve common goals, while the second underscores their ability to acquire resources and build network relationships among diverse stakeholders [14]. In the cases examined in this study, each organization has its own leaders;; however, leadership effectiveness ultimately depends on the engagement of followers. The shared objective among these organizations is the adoption of natural farming and eco-friendly practices. Thus, during the transition of farming methods, leadership must first focus on building consensus.

This study suggests that the centrality dimension parallels the managerial role of transformational leaders, whereas the brokerage function aligns more closely to the transactional role in collective action. In this case, leaders alternated between these roles at different stages of the transition process, demonstrating a “transfor-sactional” management approach. Their complementary collaboration was crucial in overcoming challenges and gradually mobilizing collective efforts, as discussed below.

5.1. The Managerial Status of the Transformative Tendency Leadership

Transformational leadership inspires its members to actively participate in their activities so that they can transform and go beyond expectations. Leadership will also actively transform itself when expressing their shared vision for the future. In addition, they will act as role models and encourage acceptance of collective goals. They also set high expectations and support intellectual stimulation and support for the personal development needs of the members [33,34]. Transformational leadership can facilitate knowledge sharing in teams [49], resembling an entrepreneurial system in which social value is generated while organizational objectives are simultaneously achieved.

5.1.1. Strategic Orientation and Incentive Mechanisms

In the transformation of farming practices in Wufeng, FA1 initiated the shift from conventional farming to sustainable agriculture. Early discussions on promoting organic rice met resistance from farmers accustomed to traditional methods. The Association adopted a stepwise transition, transitioning from non-toxic farming to natural farming. Such reform requires strong leadership in lobbying, supporting research of supplementary measures, and creating incentive mechanisms to encourage adoption while safeguarding farmers’ livelihoods.

Key incentives included:

- Positive incentives: Guaranteed purchase price contingent on compliance with eco-friendly farming practices, such as using organic manure, adhering to technical guidance, and maintaining production records.

- Negative incentives: Non-compliance resulted in termination of contracts and loss of eligibility for guaranteed purchase.

After establishing the incentive mechanisms, Director-General FA1 implemented them rigorously, and it continues to be enforced to this day. Taking the 2025 cultivation as an example (Table 1), the total income per hectare under the eco-farming contract was slightly lower than that of other conventional farming areas. However, because eco-farming did not require chemical fertilizers or pesticides, production costs were relatively low, so the net income remained close to expectations. Although the first-crop yield was slightly lower, the second-crop yield improved, and the rice quality was also better. The guaranteed purchase price provided by the Farmers’ Association enabled farmers to continue practicing eco-farming consistently.

Table 1.

The cost–benefit analysis of rice production per Hector in diverse modes of operation of the Wufeng Farmers’ Association.

5.1.2. Expansion and Corporate Participation

Encouraged by the benefits of transitioning to eco-friendly farming, the cultivated area in Wu-Jia-Di gradually expanded from approximately 5 hectares in 2015. Through the promotion of the “Hundred-Hectare Farmland Revitalization Project,” local enterprises were invited to sponsor rice produced in Wu-Jia-Di, encouraging corporate participation in sustainable agriculture. This enterprise adoption not only provided financial support but also strengthened local collaboration, enabling farmers to continue eco-friendly practices with reduced risk. As a result, the cultivated area increased to 58 hectares by 2020 and further expanded aggressively to nearly 100 hectares by 2025, reflecting growing adoption among both farmers and local enterprises. The scale of farmers’ participation is summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Expansion of contracted farmland under the Hundred-Hectare Farmland Revitalization Project in Wujia Di (October 2025). Unit: hectares.

In the past three years, around 30 enterprises have continuously sponsored for two consecutive years, with several supporting as many as five units, demonstrating a strong level of commitment. This data demonstrates the project’s significant impact in promoting eco-friendly farming and engaging the local community.

5.1.3. Hybrid Leadership in Practice

FA1’s transformational leadership was not limited to the transition of farming techniques but extended to value-chain innovation and local revitalization. To enhance the added value of “Yihchuan Aromatic Rice”, the Wufeng Farmers’ Association established a winery in 2007, integrating local agricultural products and learning Japanese sake brewing techniques. After adopting non-toxic, natural farming in 2015, they began brewing sake with Wujia rice. Their first product, “Azhaowu First Brew,” combined local culture with Japanese sake aesthetics, expressing gratitude for the land and its bounty. This approach not only created a market for aromatic rice but also fostered creative agricultural industries. The sake produced went on to win three major international gold awards in 2018, highlighting both market innovation and cultural significance. Between 2020 and 2025, the winery has won international liquor awards almost every year, demonstrating the high acclaim of its products and serving as a guarantee of strong sales performance.

Building upon this momentum, the Association transformed the old Minsheng Clinic into the Wufeng Minsheng Story House in 2016. The site featured the Agri-Culinary Hall, where eco-friendly ingredients were showcased through food–agriculture education, farmers’ markets, and experiential learning, deepening public engagement with sustainable farming. In 2017, the FA launched the Puli Gonghao Super Mall (Co-Prosperity Platform), an e-commerce initiative connecting farmers and consumers to promote natural, high-quality, and co-beneficial products. This platform embodied the principle of shared prosperity while expanding market access for sustainable producers.

Following certification by the Ministry of Agriculture as a promoting environmentally friendly farming practices organization in 2018, the Association obtained transitional organic certification in 2020, advancing Wujia rice toward full organic status. Furthermore, under the theme “Rural Community and Farmers’ Association Collaboration in Developing an Ecological Organic Rice Industry,” ecological monitoring and habitat maintenance were conducted for the endangered Black-winged Kite.

This initiative promoted eco-friendly fields, farmland landscapes, and biodiversity-friendly practices, based on the autonomous beliefs of Wufu community farmers. In December 2022, the project was recognized by the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) and included as an international case study, highlighting Wufeng’s achievement in linking ecological resilience, local innovation, and collective action [32,51,54].

Together, these initiatives reflect a hybrid, transfor-sactional leadership model, integrating transformational vision with transactional coordination. FA1 and his team acted as social and economic entrepreneurs, integrating cultural creativity, market innovation, and ecological responsibility. Their adaptive management transformed challenges into opportunities, fostering both economic vitality and social legitimacy for eco-friendly farming, and establishing Wufeng as a model for sustainable rural transformation. All of these initiatives exemplify hybrid, transfor-sactional leadership and are consistent with international studies indicating that transformational leadership fosters commitment and drives innovation in sustainability transitions [21,26].

5.2. The Intermediary Role of Transactional Leadership

Transactional leadership emphasizes the exchange relationship between leaders and followers, in which leaders communicate clear expectations and provide rewards based on followers’ achievement of pre-established goals [55,56,57]. Similar to transformational leadership, transactional leaders also expect members to commit to organizational objectives and assume responsibility for the results [58,59].

5.2.1. Persuasion and the Challenge of Adoption

In this case, the leader and deputy leader of the production and marketing group aimed to persuade members to accept and participate in the innovative plan of adopting natural farming. The “reward,” however, was not merely monetary but referred to the incentive mechanisms provided by the Farmers’ Association. Such mechanisms aligned with the concept of “societies in harmony with nature” proposed by the Satoyama Initiative, which emphasizes institutional support and community collaboration to sustain both the productive and ecological functions of agricultural landscapes [54,60,61].

At the initial stage of promoting natural farming, many farmers were reluctant to accept the concept. The then group leader, FM1, explained that the FA1 of the Farmers’ Association proposed a guaranteed purchase price equivalent to that of conventional farming. This policy was intended to protect farmers’ income and reduce the risks of adopting new farming methods.

5.2.2. Negotiation and Income Security

Despite the guaranteed price policy, the first year of promotion in 2015 suffered from poor yields caused by low temperatures and typhoons. Farmers were unable to recover their production costs, while the Farmers’ Association faced pressure to purchase rice of low yield but high cost. The FA1 dispatched two representatives, along with Leader FM1, to negotiate the purchase price with farmers.

As the offered price fell below farmers’ expectations, some farmers considered withdrawing and entrusted FM1 to renegotiate on their behalf. To address farmers’ concerns and ensure continued participation, FM1proposed that the promotional policy should take into account the basic income of farmers. He calculated that conventional farming typically generated profits of NT$5000–10,000 per tenth of a hectare, averaging about NT$8000. The Farmers’ Association subsequently increased the guaranteed price to NT$8500, supplemented by a NT$250 bonus, for a total of NT$8750. Considering production expenses such as plowing, transplanting, harvesting, transportation, and seedlings (approximately NT$5000), he argued that farmers’ total income should reach at least NT$13,750. Consequently, the Farmers’ Association adopted a guaranteed price of NT$14,000 per tenth hectare to stabilize farmers’ income and support the transition to natural farming.

Although this guaranteed price helped secure income stability, many farmers continued to manage their farmland diligently. When the quality of seedlings was poor and they withered after transplanting, farmers voluntarily purchased new seedlings to maintain natural farming practices, even though the Association did not require them to do so. This demonstrated the internalization of responsibility and trust between leaders and members.

5.2.3. Trust, Complementary Leadership, and Social Capital Formation

Beyond financial incentives, leadership credibility and interpersonal trust became decisive factors in sustaining collective action. When seedlings failed after transplanting, many farmers voluntarily purchased replacements to uphold natural farming standards, demonstrating the internalization of collective responsibility.

With more than fifty years of farming experience, Deputy Leader FM2 himself was recognized for his openness, reliability, and commitment to collective benefit. His collaboration with Leader FM1 exemplified complementary leadership, combining negotiation skills and practical experience. Together, they successfully persuaded members to engage in natural farming, thereby strengthening cooperation, enhancing the integration of production, livelihood, and ecology, and ultimately contributing to the accumulation of social capital within the community.

Thus, transactional leadership served as an effective intermediary mechanism, bridging the gap between institutional incentives and farmers’ trust, and laying the foundation for deeper collective engagement and the emergence of transformational leadership in the subsequent stage. This intermediary function also resonates with the Satoyama Initiative framework, which emphasizes multi-level collaboration and adaptive governance in socio-ecological production landscapes [54,61,62,63]. These findings are also consistent with international studies highlighting how transactional leadership facilitates trust-building and collaboration during sustainability transitions [64].

5.3. Implementation Challenges and Hybrid Leadership

5.3.1. Leadership Mechanisms, Hybrid Approach, and Economic Outcomes

The adoption of natural farming and eco-friendly cultivation methods in the Wufeng District demonstrates successful collective mobilization, driven by hybrid, adaptive leadership. FA1and his team, together with production and marketing team leaders FM1 and FM2, exemplified transfor-sactional leadership, blending transformational inspiration with transactional accountability. They guided farmers from the Wu-Jia-Di experimental base, establishing incentive mechanisms, reducing operational risks, and gradually expanding eco-friendly farming across the district [26,31,34,35,36]. No farmers were disqualified for violations, and there were no major conflicts during the transition process, setting a precedent for effective collective action. Nevertheless, the implementation of this initiative faced multiple challenges, which were successfully overcome due to the wise leadership of local leaders [19,21].

At the outset, only nine households agreed to participate due to uncertainty over yields and financial risks. Early setbacks, including cold fronts and typhoons, caused significant yield losses, prompting some farmers to consider withdrawal. Through persistent persuasion, trust-building, and transparent communication, FA1 and his leadership team convinced farmers to persevere. Transitioning to eco-friendly farming increased labor-intensive tasks, particularly for weeding and irrigation. To address these challenges, FA1 introduced a reward-based contract mechanism, guaranteeing stable purchase prices while requiring adherence to specific cultivation standards. Under this system, FM1 and FM2 implemented soft supervision, ensuring compliance without undermining farmer motivation [33].

Additionally, FA1 also leveraged personal networks to invite environmentally conscious enterprises to sponsor eco-friendly farmland, further reducing financial risk for participants. These sponsorships encouraged broader participation and demonstrated the economic viability of sustainable farming. To enhance the value of eco-farming rice, the Wufeng Famers’ Association established a winery, transforming the rice into high-quality sake. Staff were trained in Japan over two years to acquire brewing techniques, which were adapted locally. The resulting products won international gold medals, strengthening brand reputation, expanding markets, and increasing farmer confidence [64,65].

The Association also restructured internally, establishing departments for marketing, tourism, brewing, and planning, while training staff to support a vertically integrated eco-agricultural system. Despite continued financial pressures, investments in independent processing equipment, land acquisition, and professional development demonstrate a long-term commitment to sustainable innovation.

The impact of these leadership mechanisms is evident in both the scale of adoption and the financial outcomes of the “Hundred-Hectare Farmland Revitalization Project.” Eco-friendly cultivation expanded from 5 hectares in 2015 to 58 hectares in 2020, and nearly 100 hectares by 2025, with 57.72 hectares certified organic, 29.38 hectares in transition, and 9.4 hectares newly adopting eco-friendly practices (see Table 1).

Two key economic benefits are particularly notable (see Table 2):

- Increased net income per hectare: Despite initially lower yields, eco-friendly farming achieved a net income of 218,600 TWD per hectare in 2025, surpassing the 174,306 TWD of conventional contract farmers. This increase resulted from reduced input costs, FA subsidies of 21,100 TWD per hectare, and a guaranteed purchase price, which collectively lowered financial risk and incentivized continued participation.

- Enhanced market value through product diversification: The establishment of the winery and branding of premium rice for sake production added a value-added revenue stream, improving profitability and expanding market opportunities beyond standard rice sales. This approach demonstrates how leadership-driven innovation can integrate ecological sustainability with tangible economic returns.

Together, these outcomes show that hybrid leadership not only promoted ecological adoption but also generated measurable financial incentives that reinforced farmer commitment and long-term sustainability. These results also echo international findings that hybrid leadership models enhance both the effectiveness and durability of sustainability transitions in agriculture [14,59,64].

5.3.2. Adaptive Leadership Traits in Practice

The Wufeng District case illustrates how adaptive leadership complements transformational and transactional approaches in practice. The following table summarizes the key traits of adaptive leadership, their manifestation in the Wufeng case, illustrating how leaders identified emerging challenges, mobilized resources, and coordinated actors across multiple levels of the local agri-food system.

The hybrid leadership traits demonstrated in Wufeng (Table 3) align closely with the conceptual framework illustrated in Figure 1 (Section 2.2), where transformational, transactional, and adaptive elements integrate to enable effective eco-friendly agricultural transitions. Leaders’ social and economic entrepreneurial capacities were crucial in navigating organizational and environmental challenges, coordinating farmers, and leveraging institutional resources.

Table 3.

Adaptive leadership traits and their manifestation in the Wufeng District case.

However, the Wufeng case also reveals the limits of leadership in the absence of supportive institutional structures. In contrast to Wufeng’s relative stability, the Zhongqi Organic Agriculture Promotion Zone in Kaohsiung illustrates how eco-friendly agriculture remains highly vulnerable when cross-sector governance is weak. Despite years of investment in ecological management and organizational development, the promotion zone was displaced in 2023 due to the expansion of the Qiaotou Science Park [44]. The forced relocation underscores how agricultural and ecological objectives can be overridden by competing land-use priorities when legal safeguards, land security, and inter-agency coordination are insufficient.

This contrast highlights a critical point: adaptive leadership can mobilize farmers, coordinate innovation, and mitigate local risks, but it cannot compensate for structural deficiencies in spatial and institutional governance. Effective eco-friendly agricultural transitions require not only capable hybrid leadership, but also:

- coherent cross-ministerial coordination,

- long-term institutional and financial support, and

- robust regulatory mechanisms that protect agricultural land from displacement.

Without these enabling conditions, even well-led initiatives remain precarious, limiting the scalability and long-term sustainability of eco-friendly farming efforts.

5.3.3. Implementation Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions

Building on the adaptive and hybrid leadership traits identified in Table 3, the Wufeng Farmers’ Association has translated these capacities into tangible organizational innovations. In 2020, it partnered with 13 other farmers’ and fisheries associations and agricultural enterprises, collectively establishing Taiwan Value-Added Agriculture Co., Ltd. (TVAA) and the Nong-Chuang-Chia brand, the association strengthened resource integration, expanded market channels, and enhanced value creation. These innovations provide the foundation for understanding the implementation challenges and limitations discussed below.

- Farmer engagement and risk management

Selecting suitable experimental sites and persuading farmers to participate initially proved difficult due to uncertainty over yields and potential financial losses. Early cold fronts and typhoons caused yield reductions, prompting some households to consider withdrawal. Persistent persuasion, clear communication, and trust-building by FA1, FM1, and FM2 were critical to maintaining commitment and ensuring continued participation.

- 2.

- Labor-intensive practices and operational management

Transitioning from conventional to eco-friendly farming increased labor demands, particularly for manual weeding, irrigation, and seedling management. FA1 implemented reward-based contracts with guaranteed purchase prices, while FM1 and FM2 provided soft supervision, which minimized violations, ensured adherence to cultivation standards, and reinforced farmers’ accountability. These mechanisms effectively balanced autonomy with structured oversight, demonstrating the complementary roles of transformational and transactional leadership.

- 3.

- Financial pressures and market development

Although enterprise sponsorships, guaranteed prices, and Famers’ Association subsidies mitigated risks, rice procurement and processing remained costly. Maintaining a nearly 100-hectare eco-friendly cultivation area required ongoing investments in land, machinery, personnel training, and market expansion, including sake production, branding of “Black-Winged Kite Rice,” and e-commerce initiatives such as the Puli Gonghao Super Mall. Continuous financial planning and leadership engagement were essential to sustain these operations.

- 4.

- Quality improvement and ecological management

Achieving organic certification and high-quality standards demands consistent application of optimal farming practices. Effective control of plowing, irrigation, and seedling growth is crucial to suppress weeds without herbicides. Moreover, ecological initiatives such as habitat monitoring for the endangered Black Kite required ongoing leadership coordination and community participation to integrate biodiversity conservation with production practices.

- 5.

- Future directions and leadership development

Current eco-friendly practices focus primarily on rice, but future expansion could include vegetables, fruits, and agri-tourism to enhance multifunctionality and income diversification. Sustained leadership is required to cultivate talent, support innovation, and guide farmers through evolving challenges. The hybrid, adaptive “transfor-sactional” leadership approach—combining visionary guidance, structured management, and flexible problem-solving—remains essential for addressing operational, environmental, and economic obstacles while fostering collective action and social cohesion.

Overall, FA1 and his core team exemplify hybrid, adaptive leadership, integrating transformational vision, transactional oversight, and entrepreneurial traits. This approach has been critical for sustaining eco-friendly practices, overcoming challenges, and linking economic, ecological, social, and cultural values into a coherent, community-based model of sustainable agriculture.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

In recent decades, conventional agriculture has increasingly contributed to the deterioration of social and ecological environments. This operational model has been recognized as detrimental to both human and environmental health, prompting a shift toward natural farming and eco-friendly cultivation practices to promote sustainable agricultural development. However, the successful transition in farming practices cannot rely solely on individual efforts; it requires coordinated collective action among farmers within a regional context.

6.1. Conclusions

This study aimed to explore the role of leadership in promoting collective action for natural agriculture through qualitative research, focusing on Wufeng District in Taichung City as a case study. Three critical driving factors were identified that facilitate the transformation of farming practices: (1) the Farmers’ Association’s vision and incentive mechanisms, (2) technical support from agricultural research institutes, and (3) mobilization by production and marketing team leaders. Key findings include:

- Leadership as managers, intermediaries and entrepreneurs

The Wufeng case highlights leadership as both managerial and intermediary. FA1 exemplifies transfor-sactional leadership, blending transformational vision with transactional oversight. He acted as a social entrepreneur, pursuing sustainable solutions that benefited the community and environment, and as an economic entrepreneur, designing incentive mechanisms such as guaranteed purchase prices and compliance-based penalties to align farmers’ actions with collective goals. Production and marketing team leaders (FM1, FM2, and others) performed intermediary functions, conveying information, negotiating agreements, and stabilizing farmers’ incomes. Both transformational and transactional roles were essential to initiate, maintain, and scale collective adoption of eco-friendly farming practices [31,41]. Unlike some rural leadership models in China, the Wufeng leadership team entrusts communication and coordination to production and marketing leaders, effectively fulfilling personal responsibilities and encouraging collective action [66].

- 2.

- Addressing sustainable development challenges.

Leaders in Wufeng have strengthened follower awareness, secured resources, and motivated farmers to engage in eco-friendly farming while maintaining income. However, transitioning from conventional farming is challenging due to the proximity of chemically farmed fields and labor-intensive practices like manual weeding. Production and marketing leaders continuously adjust mobilization strategies to ensure commitment and prevent reversion to conventional methods.

- 3.

- Expansion of eco-friendly cultivation and product value.

Under the leadership of FA1, eco-friendly cultivation areas have expanded annually. Branding initiatives, such as Wujia Rice and Black-Winged Kite Rice, have enabled high-quality rice to be used for premium sake that has won international awards, maximizing product value. These initiatives enhance land utilization, environmental benefits, economic returns, and social welfare. Farmers who previously hesitated now actively inquire about participation, demonstrating the effectiveness of leadership in promoting sustainable practices despite the high costs of rice procurement and market imbalances.

- 4.

- Integrating cross-case insights

Taken together, these findings justify the selection of Wufeng as a case study and underscore the importance of context-specific leadership mechanisms that integrate transformational, transactional, and adaptive elements. At the same time, evidence from the Xingjian (Chen, 2020 [43]) and Zhongqi cases highlights that even effective hybrid leadership may be insufficient without complementary institutional safeguards, regulatory compliance, and spatial governance. Therefore, sustainable eco-friendly and organic agricultural transitions require a dual focus on leadership capacity and robust policy and land-use frameworks to secure long-term environmental integrity and organizational effectiveness.

6.2. Policy Implication