Abstract

Despite intensified global efforts to accelerate the renewable energy (RE) transition, the influence of artificial intelligence (AI) and energy security risk (ESR) on RE adoption remains underexplored in the United States. This study examines the nonlinear and time-varying effects of AI, ESR, financial development (FD), and economic growth (GDP) on RE consumption from 1990Q1 to 2020Q4. Annual data were converted to quarterly frequency using the quadratic match sum method, and the Wavelet Cross Quantile Regression (WCQR) technique was employed to capture dynamic relationships across quantiles and time scales. The results show that AI and FD consistently stimulate RE adoption, while ESR shifts from a negative short-term influence to a positive long-term effect. Similarly, GDP initially reduces RE consumption but becomes supportive over longer horizons. This study offers new contributions by providing the first empirical evidence on the role of AI in shaping the U.S. renewable energy transition and by jointly examining technological, financial development, and energy security determinants within a unified framework. Policy implications suggest prioritizing investment in AI-based grid and storage systems, expanding green financing tools to lower capital barriers, and adopting long-term energy security strategies to sustain progress toward a low-carbon energy system.

1. Introduction

To fortify the global response to the perils of climate change within the framework of sustainable development, the Paris Accord advocates for the limitation of the global average temperature rise to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, with efforts directed at capping the upsurge to 1.5 °C [1]. The three primary greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters, namely China, the EU, and the United States have now unequivocally embraced carbon neutrality as their overarching objective. Specifically, the EU has committed to achieving climate neutrality by 2050, while China has pledged to peak its emissions “before 2030” and attain “carbon neutrality before 2060.” Similarly, former President Joe Biden of the United States prioritized climate change as a central issue and articulated a steadfast pledge to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 [1]. Realizing the carbon neutrality objective amidst global population growth and escalating consumption patterns necessitates a transition to zero-carbon energy sources, including renewable energy (RE) and nuclear power.

In 2019, RE comprised 19.7% of the energy consumption in the EU-27, narrowly missing the 2020 target of 20% by just 0.3% [2]. In the United States, renewables accounted for approximately 13.1% (see Figure 1) of energy production, surpassing coal consumption for the first time since prior to 1885, with RE in 2019 nearly tripling compared to 2000 levels [1]. Developed nations, including the United States, are collaborating to double the share of RE in the global energy mix by 2030. Similarly, Europe aims to lead as the world’s first climate-neutral continent by 2050, with the European Green Deal serving as the blueprint for ensuring the EU economy’s sustainability [3]. The United States Energy Information Administration forecasts a continued upsurge in United States RE through 2050 [1]. This emphasis on RE is vindicated by its potential economic and ecological benefits, including the lessening of GHG and certain types of diversification of energy sources, air contamination, the promotion of job creation in green technologies and economic development.

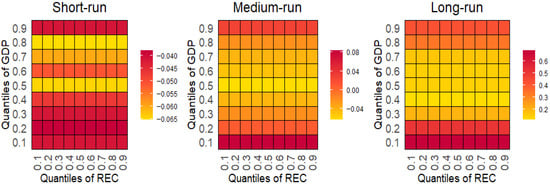

Figure 1.

Trend of variables.

One of the primary hurdles to the extensive adoption of RE is the issue of capital costs. Undeniably, the initial investment required for RE projects tends to be relatively high compared to traditional energy sources. Moreover, RE projects often entail extended payback periods, necessitating substantial levels of financing. In this context, the role of financial development (FD) emerges as a critical factor influencing the uptake of RE. Financial infrastructure plays a pivotal role in shaping energy demand and fostering economic growth [4]. A robust financial system comprising well-developed banking institutions, equity markets and financial markets can significantly augment the availability of funds for investment [5]. Research consistently indicates that more advanced financial systems enhance both economic development and investment flows, which indirectly shape energy demand patterns [6]. Through mechanisms such as the “level effect,” whereby financial markets mobilize funds for high-yield projects, and the “efficiency effect,” which improves resource allocation and liquidity, FD contributes to more sustainable investment behaviors.

FD also influences energy consumption through direct, business, and wealth effects [7,8]. Enhanced financial development reduces borrowing rates and enables households to purchase durable goods—often energy-intensive—while also enabling firms to invest in technology that may either increase or reduce energy use depending on the nature of the investment. Thus, FD’s impact on renewable energy development remains theoretically ambiguous, underscoring the need for empirical investigation. Energy security risk (ESR) has similarly been identified as a factor affecting renewable energy. ESR denotes a nation’s vulnerability to disruptions that could affect its energy supply, potentially leading to adverse social, economic, or political consequences. These risks stem from geopolitical conflicts, natural disasters, cybercrime, and supply-chain disruptions. Recent studies [9,10,11] have demonstrated a substantial correlation between RE and ESR. ESR may also alter financing costs for renewable energy projects [12], with higher perceived risks elevating interest rates and complicating project development. Understanding whether ESR ultimately hinders or promotes RE adoption remains an unresolved and policy-relevant question, particularly for countries seeking to transition their energy systems. Despite growing interest in AI and sustainability, the literature offers only scant empirical evidence quantifying how AI advancements, measured through actual indicators such as AI-related patent counts, influence renewable energy consumption.

The evaluation of the impact of ESR on RE is to address current knowledge deficiencies in research and provide a cohesive policy viewpoint concerning the relationship between ESR and RE. Concerns over energy security can either promote or inhibit investments in the renewable energy sector. In this study, artificial intelligence (AI) refers specifically to technological innovation and digital automation capabilities captured through the U.S. Artificial Intelligence Patent Database (AIPD). Accordingly, AI is operationalized using quarterly counts of AI-related patents, which serve as a recognized proxy for AI-driven technological development and diffusion across the energy sector. An increase in AI patents therefore reflects heightened technological progress that can influence renewable energy optimization, forecasting, and integration into power systems.

A notable factor affecting renewable energy is artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence is the simulation of human cognitive functions by computers, particularly computer systems. These technologies enable machines to do activities often linked to human intelligence, such as experiential learning, pattern recognition, natural language understanding, and decision-making [13]. Although artificial intelligence plays a significant role in transforming several industries, its relationship with RE has been inadequately explored in the literature. AI is expected to significantly influence the development and enhancement of renewable energy systems and technology [14]. AI systems can reduce dependence on fossil fuel-based power generation during peak demand while simultaneously enhancing the use of renewable energy by aligning energy usage with its availability. AI technology enhances the reliability and efficiency of energy storage systems, such as batteries and pumped hydro storage [15,16]. AI systems provide the efficient storage of renewable energy generated during low-demand periods for subsequent use during peak-demand times by optimising charging and discharging schedules according to demand projections and grid circumstances.

Prior empirical research has predominantly focused on elucidating the factors influencing renewable energy, including economic policy uncertainty, financial development, trade openness, economic growth, and public–private investment in energy [17,18,19,20,21]. The work of [5] is significant for elucidating the connection between energy security risk and renewable energy. Nonetheless, a significant gap exists in the research about the influence of artificial intelligence and financial globalisation on renewable energy, with no current studies examining this issue. Thus, our research broadens the existing literature by integrating these essential factors to clarify the dynamics of renewable energy in the United States. The primary research questions are outlined below. The aim of this study is to empirically examine how artificial intelligence, energy security risk, and financial development jointly affect renewable energy consumption in the United States across different quantiles and time horizons, thereby providing a multidimensional understanding of the technological, structural, and security-related determinants of renewable energy transition. Accordingly, this study addresses two key research questions:

- To what extent does artificial intelligence (AI) influence renewable energy consumption (REC) across different quantiles and time horizons in the United States?

- How does energy security risk (ESR) affect renewable energy consumption in the short, medium, and long term?

The contributions of this study are fourfold. First, this research provides the first empirical evidence on how AI-driven technological innovation—captured through AI— shapes renewable energy consumption in the United States, thereby demonstrating AI’s strategic role in accelerating energy transition. Second, we reveal how the influence of ESR evolves across time scales, documenting a shift from restrictive short-term effects to supportive long-term effects. Third, we show that FD promotes renewable energy development across different distributional conditions and time frequencies, highlighting its structural importance beyond mean-based relationships. Finally, by employing the Wavelet Cross-Quantile Regression (WCQR) framework [22,23], this study introduces a novel methodological approach that jointly captures time-frequency dynamics and quantile-specific dependence, yielding richer insights than conventional econometric techniques.

The remaining portion of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 offers an extensive literature evaluation grounded in the existing body of literature. Section 3 presents the empirical model and describes the estimating process used. Section 4 presents the empirical findings, while Section 5 provides the policy implications.

2. Theoretical Underpinning and Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Underpinning

The transition to renewable energy is fundamental to sustainable development and is shaped by a wide range of economic, technological, and institutional factors. To investigate how artificial intelligence (AI), financial development (FD), energy security risk (ESR), and renewable energy consumption (REC) influence the renewable energy transition in the United States, this study draws on four classical theoretical frameworks—endogenous growth theory, financial intermediation theory, risk aversion and energy diversification theory, and innovation diffusion theory. In addition, the study incorporates the distributional heterogeneity principles underlying the Cross-Quantile Regression (CQR) framework, which provides the methodological foundation for analysing the dynamic and nonlinear interactions among these factors.

Endogenous growth theory [24] posits that technological advancement serves as an internal driver of long-term economic and structural transformation. Innovation and the accumulation of knowledge—often supported by investments in research and development—are essential for sustaining growth. Within this framework, AI represents a transformative general-purpose technology that enhances the efficiency, intelligence, and stability of renewable energy systems. AI-based algorithms improve energy demand forecasting, optimise smart grid operations, and enhance the performance of storage and distribution networks [15]. These improvements strengthen decision-making processes, increase system responsiveness, and ultimately facilitate a scalable and resilient renewable energy infrastructure. Financial intermediation theory [7] highlights the critical role of a well-developed financial system in mobilising savings, reducing transaction costs, and allocating resources efficiently. Renewable energy projects are highly capital-intensive and often characterised by long investment horizons, making financial development essential for expanding renewable capacity. Advanced financial markets promote clean-energy investment by lowering financing constraints, reducing capital costs, and facilitating access to sustainable finance instruments such as green bonds and renewable energy funds [25,26]. Accordingly, FD is expected to positively influence the renewable energy transition by enhancing investment incentives and supporting risk-sharing mechanisms.

Energy security risk—which encompasses price volatility, geopolitical tensions, supply disruptions, and infrastructural vulnerabilities—also plays an important role in shaping energy transitions. Drawing on risk aversion theory and the energy diversification hypothesis [9], high levels of uncertainty in fossil-fuel-based energy systems may initially deter investment in renewables due to perceived risk. However, persistent or systemic energy insecurity frequently prompts policy reforms and strategic diversification toward more stable, domestically available renewable alternatives [27]. Thus, ESR exerts a nonlinear influence, imposing short-run constraints while fostering long-run structural shifts toward renewables. Innovation diffusion theory provides additional insight into the behavioral and learning mechanisms associated with technological adoption. Rising REC enhances familiarity with renewable technologies, stimulates cost reductions through scale effects, facilitates learning-by-using dynamics, and strengthens network externalities. These processes accelerate the diffusion of renewable technologies and reinforce adoption across sectors. While these theories explain why each variable affects the renewable energy transition, they collectively imply that these effects are heterogeneous, nonlinear, and state-dependent. Such complexity underscores the need for an empirical approach that captures variations across different levels of the renewable energy distribution. The Cross-Quantile Regression (CQR) framework by [27] responds to this need by extending the logic of quantile regression [27] and modelling how different quantiles of the predictors influence different quantiles of the dependent variable. Building upon the distribution-to-distribution logic in Quantile-on-Quantile Regression [28] and the parametric refinements introduced by [29,30], the CQR approach allows the dynamic, asymmetric, and time-varying relationships among AI, FD, ESR, and REC to be examined with greater precision.

2.2. Literature Review

The unchecked expansion of fossil fuel use poses significant risks by accelerating global climate change. However, accelerating the transition toward renewable energy provides a critical means of reducing these risks and reinforcing climate mitigation initiatives. Empirical evidence prominently underlines the pivotal role of transitioning to RE in achieving SDG-7, as depicted in extant literature. For instance, various studies have elucidated how factors such as energy security risk [28], globalization [11], and economic growth [12] can stimulate RE usage [19,29]. Ref. [30] found that renewable energy can reduce energy market uncertainty when supported by strong policies and mature technologies. However, in contexts of weak institutional support or technological instability, renewable energy may initially amplify uncertainty. Using a time-varying Granger causality approach, ref. [31] showed that the relationship between energy-related uncertainty and renewable energy shifts over time. Their results revealed that uncertainty can initially stimulate renewable adoption but persistent high uncertainty discourages investment, underscoring the need for stable policy support. Ref. [32] examined whether the circular economy supports energy security and renewable energy development in Europe, applying 2SLS and SGMM estimators using recent panel data. Their findings showed that circular economy practices and innovation reduce energy security risks and significantly enhance renewable energy production, while factors like FDI and carbon emissions increase security vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the significance of technological innovations and financial development in bolstering the RE sector’s growth trajectory should not be underestimated [30,31].

Several studies documented regarding the drivers of RE have produced inconsistent results, leading to further investigation. For instance, ref. [29] used 28 EU nations and data from 1990–2015 in investigating the determinants of RE using a panel estimator, with the result unveiling that FDI, FD EG and energy price directly impacting RE positively. Likewise [32], using the VECM and data from 1980–2019, examined the determinants of RE for the Turkish case with the result supporting the RE intensifying role of FD. The authors also offer suitable strategies for Turkey to enhance investments in RE, thereby fostering sustainable economic and social development. The investigation of [28], also validates the perspective of [32], who emphasized that FDI and FD promote RE in the 39 nations from 2000–2019. The study of [20] for the case of 27 transition nations from 1990–2014 considers the role of unemployment and government debt in the RE model, with the result showing that EG, government and unemployment promote RE.

Also, some studies incorporate the role of innovations in their investigation of drivers of RE. For example, ref. [33] employed OECD economies over the period between 1990 and 2017 to examine the effect of innovations, FD, human capital, and EG on RE using the CSARDL. The study’s discoveries showcase those innovations, such as FD and HC, foster RE in the long run. Furthermore, Ref. [34], analysed how oil efficiency, hydro energy, and fiscal decentralization influence Iceland’s environmental sustainability over 1999Q1–2021Q4. Using wavelet quantile regression and quantile-on-quantile Granger causality, they assess the dynamic relationships among these factors across time and quantiles. Their findings show that renewable energy expansion, improved oil-use efficiency, and decentralized governance jointly reduce CO2 emissions and provide a replicable low-carbon policy framework. Ref. [35], in a similar way, used the nonlinear ARDL in examining the RE drivers for the Pakistan case using data between 1980 and 2019. The drivers considered include EG, FD and CO2, with the outcomes showcasing that FD, CO2 and EG impact RE positively and significantly in the long run.

Recently, some studies have also identified the role of energy security risk and energy price as a significant driver of RE. The investigation initiated by [36], highlighted the significant connection between RE and ESR. In the investigation of [37] on the effect of energy security risk, income, FD and trade openness, the investigators using the panel estimators showed that ESR and FD intensify RE in the selected economies. A study by [9] on the nexus between RE and ESR showed a significant interrelationship between risk and RE. Ref. [10] conducted a study on the G7 countries from 1980 to 2018 to examine the relationship between RE and ESR. They used the QQR and Granger causality methods and found that there is a one-way causal link from RE to ESR in the short term. Furthermore, they discovered that RE significantly decreases the risks that pose a threat to energy security in the long term.

In similar way, ref. [38] used the GMM estimator for the BRI economies to explain how FD, innovations and income impact RE, with the outcomes showing that income and innovation foster RE while FD impacts RE negatively. Moreover, ref. [16] used the most populous nations in Africa to explain the determinants of RE using data from 1996–2016. The results based on the Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) disclosed that urban population, innovations and electric power consumption increase RE.

2.3. Gap in the Literature

Despite the vast literature on renewable energy, a substantial knowledge gap persists about the complex interactions among renewable energy, energy security risk, financial development, and economic growth in the United States. Current research mostly examines these components in isolation or in restricted combinations, leading to a disjointed comprehension of their intricate dynamics. Furthermore, an important amount of the literature concentrates on larger groups of nations, such as developed and emerging countries, therefore lacking insights pertinent to a single country like the United States.

Moreover, none of these studies examined the function of artificial intelligence, hence offering additional research opportunities. This work seeks to rectify this deficiency by contributing to the under-explored domain. For example, prior research [39,40,41] mostly utilised linear methodologies. Nonetheless, due to the nonlinear characteristics of time series and panel data, the application of linear approaches may be insufficient. This work distinguishes itself from previous studies by utilising wavelet quantile regression, a nonlinear methodology, to examine the determinants of RE. This methodology enables the examination of the influence of diverse variables on RE over many quantiles (from 0.05 to 0.95) and temporal spans (short, medium, and long-term). This paper represents the first empirical examination of the impact artificial intelligence on RE, especially within the United States, using data from 1990Q1 to 2020Q4. This research aims to address these knowledge gaps by a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the interconnections among these elements within the specific setting of the United States. It seeks to enhance the theoretical understanding of sustainable energy transitions and provide insights to assist the creation of more inclusive and effective practices and policies.

3. Data Sources and Methodological Construction

3.1. Data Sources

This study examines how artificial intelligence and energy security risk influence renewable energy consumption in the United States, alongside the roles of economic growth and financial development. The analysis is conducted using quarterly data covering the period 1990Q1–2020Q4. A description of all variables is provided in Table 1, and their temporal patterns are depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Data Description.

3.2. Methodological Construction

Cross-Quantile Regression (CQR), building on the quantile regression framework of [43], examines how specific quantiles of an explanatory variable are associated with different quantiles of a response variable . In its parametric form, the CQR model can be written as:

where denotes the -th conditional quantile of given that is at its -th quantile represents the -th quantile of , which serves as the cross-quantile regressor in this specification; and and are quantile-specific intercept and slope coefficients, respectively. The coefficient captures the cross-quantile effect, that is, how the -th quantile of influences the -th quantile of . This formulation follows the distribution-to-distribution perspective introduced in quantile-on-quantile analysis [29] and its parametric cross-quantile extensions [30], allowing the relationship between and to vary flexibly across the entire joint quantile space .

Recent studies have significantly advanced the integration of wavelet decomposition with quantile-based econometric techniques. Notable contributions include [44], who introduced the Wavelet Cross-Quantile Correlation (WCQC), [45], who proposed the Wavelet Quantile Regression (WQR), [46], who developed the Wavelet Quantile-on-Quantile Regression (WQQR). While these methods have enriched the literature, each exhibits specific limitations. WQQR focuses on pairwise quantile relationships, WQR investigates the effects of independent variables on specific quantiles of the dependent variable without addressing cross-quantile dynamics, and WCQC captures the strength of cross-quantile relationships but fails to provide insights into causal or directional effects. To address these gaps, we introduce the Wavelet Cross-Quantile Regression (WCQR) [47]. This flexible framework examines how a specific quantile of one variable influence multiple quantiles of another, allowing researchers to target specific cross-quantile dynamics with enhanced analytical flexibility [48].

In the application process, the series are decomposed using the MODWT from the first level up to the maximum scale of decomposition () (The maximum depth (or scale) of the decomposition () is determined using the formula , suggested by [49]. Where represents the total length of the sample period). The MODWT of [50] is used to decompose and . Let a signal with a length of , where for an integer . Consider as the low-pass filter and as the high-pass filter. At the initial stage, is convolved with a low-pass filter to obtain approximation coefficients , and with a high-pass filter to produce detail coefficients , both of length . The process is expressed as:

This process is recursively applied to using upsampled filters , derived from . For ranging from , the coefficients are calculated as:

Here, represents approximation coefficients at the -th level, and represents detail coefficients at the same level. are the upsampled low-pass and high-pass filters from the previous level, . The up-sampling operation inserts zeros between elements, doubling the filter length to adapt it for the next level.

Furthermore, the study applied [47] quantile estimation method to calculate the conditional quantile series for the decomposed series. Third, the decomposed series from the wavelet transform are integrated into the cross-quantile regression framework at each scale as inputs, allowing for the analysis of cross-quantile dependencies between variables across different time-frequency domains:

where refers to the decomposition level, represents the -th conditional quantile of the wavelet-decomposed at scale , given the ν\nuν-th quantile of the wavelet-decomposed . denotes -th quantile of at scale , derived using wavelet decomposition and showcases coefficients that vary by quantile levels , as well as wavelet scale .

- Steps For Executing Wavelet Cross-Quantile Regression

- (1)

- Wavelet Decomposition: Decompose both using MODWT to obtain components at different scales .

- (2)

- Quantile Estimation: For each scale , calculate the quantiles of the wavelet-decomposed series for .

- (3)

- Cross-Quantile Regression at Each Scale: Perform cross-quantile regression between Y’s -th -th quantile for each wavelet scale .

3.2.1. ARDL Model Specification (Robustness Check)

To verify the stability and consistency of the WCQR results, the study employs the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) modelling framework as a parametric robustness check. The ARDL approach, originally developed by Pesaran and Shin and formalised in the bounds-testing procedure of [51,52], is particularly suitable for small samples and for systems in which the regressors are a mixture of and processes. Including lags both captures dynamic interactions and allows explanatory variables in the ARDL model between short-run adjustments and long-run equilibrium relationships. In the present context, the long-run equilibrium relationship between renewable energy consumption (or transition) and its determinants—artificial intelligence , energy security risk , financial development , and economic growth —can be written as:

where is the equilibrium error term and represent the long-run elasticities of with respect to each explanatory variable. The corresponding ARDL error-correction representation that captures the short-run dynamics is specified as Equation (8) as the short-run ARDL-ECM form:

with the error-correction term defined as Equation (9):

where denotes first differences (short-run effects), is the speed of adjustment parameter (expected ), showing how quickly deviations from longrun equilibrium are corrected, and E is the lagged residual from the long-run Equation (7), i.e., the disequilibrium term. Through this structure, the ARDL model flexibly represents variable interactions: current and lagged values of AI, ESR, FD, and GDP affect both the short-run changes and the long-run level of renewable energy, while the error-correction mechanism links short-run deviations to long-run equilibrium, allowing us to assess whether the directions and strengths of relationships obtained from the WCQR framework remain robust under a parametric dynamic specification.

3.2.2. TVP-SV-VAR Model Specification (Time-Varying Robustness)

To capture structural evolution and policy-driven dynamics, the Time-Varying Parameter Structural VAR with Stochastic Volatility (TVP-SV-VAR) is employed. The model takes the form:

where is the vector of system variables, is a time-varying coefficient matrix, is a time-varying volatility matrix. The parameters evolve according to:

allowing both coefficients and shock variances to adjust over time, capturing transitions such as policy regime shifts, market development, and technological adoption phases.

4. Empirical Results

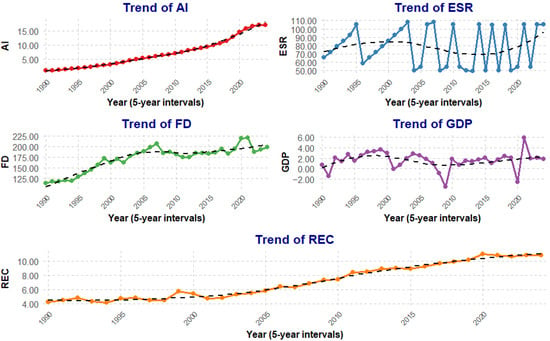

As an initial assessment, it is imperative to scrutinize the statistical characteristics of the variables under study. Figure 2 provides comprehensive information on these variables. The mean values of REC, AI, GDP, ESR, and FD are approximately 7.11, 7.03, 6.56, 78.22, and 172.01, respectively. In terms of standard deviation, FD (28.8) and ESR (23.67) display higher volatility compared to REC (2.4) and AI (4.97), indicating greater fluctuations over the sample period. The skewness and kurtosis values suggest that none of the variables follow a normal distribution, as most show asymmetric behavior and peakedness that deviate from the Gaussian pattern. Specifically, GDP shows a negatively skewed distribution, while FD exhibits the highest positive skewness and kurtosis. These characteristics emphasize the need for robust estimation methods that accommodate non-normal data behavior.

Figure 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

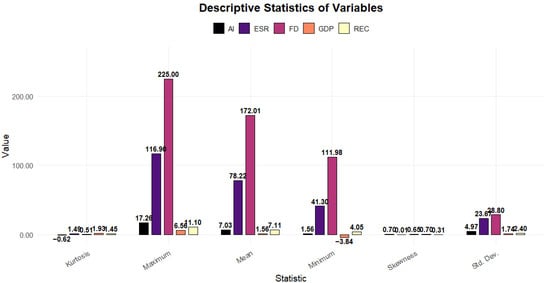

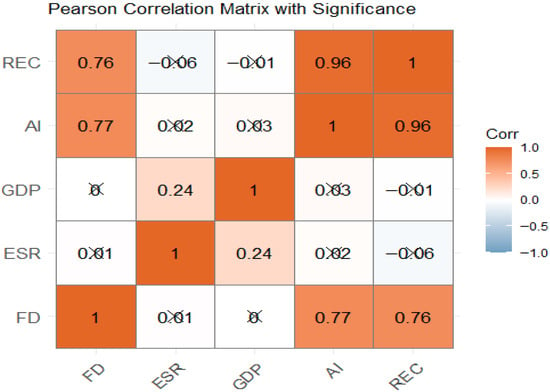

Q-Q plot analysis reveals significant departures from normality across all series (see Figure 3). Renewable Energy (RE), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Energy Security Risk (ESR), and Financial Development (FD) show the most notable deviations from the normal line, indicating strong non-normality. Economic Growth (EG) and FD display moderate tail distortions. Figure 4 presents the correlation matrix, revealing a strong and significant positive relationship between Financial Development (FD), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Renewable Energy Consumption (REC), suggesting that these factors collectively promote sustainability. Notably, the correlation between AI and REC is exceptionally high (0.96), indicating that AI investments strongly drive renewable energy adoption. In contrast, Energy Security Risk (ESR) and Economic Growth (GDP) exhibit weak and statistically insignificant correlations with all other variables. This implies that neither energy risk nor economic growth is linearly associated with AI, REC, or FD. Overall, the significant relationships underscore the pivotal role of financial and technological investments in accelerating clean energy transitions.

Figure 3.

Q-Q Plots.

Figure 4.

Pearson Correlation Matrix. Note: Crosses (×) on cells where correlation is not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

It is crucial to examine the non-linear features of the variables given their non-normal distribution. For this reason, the BDS test proposed by [48] is employed in Table 2. As shown in Table 3, the Z-statistics across embedding dimensions M2 to M6 for all variables—REC, AI, GDP, ESR, and FD—are statistically significant at the 1% level. Specifically, the BDS statistics range from 10.101 to 28.467 for REC, 19.00 to 41.125 for AI, 13.258 to 43.285 for GDP, 11.739 to 44.804 for ESR, and 15.347 to 34.910 for FD. These consistent and highly significant results confirm the presence of nonlinear dependence in all series. Therefore, relying on linear estimation techniques would lead to misleading conclusions. In line with existing literature [53] this study adopts robust quantile-based methods, including the Wavelet Quantile Unit Root Test, and Wavelet Cross-Quantile Regression (WCQR), to effectively capture the nonlinear and time-varying dynamics within the data.

Table 2.

Non-Linearity Test (BDS Test).

Table 3.

ARDL Model (Long-run and Short-run Estimates).

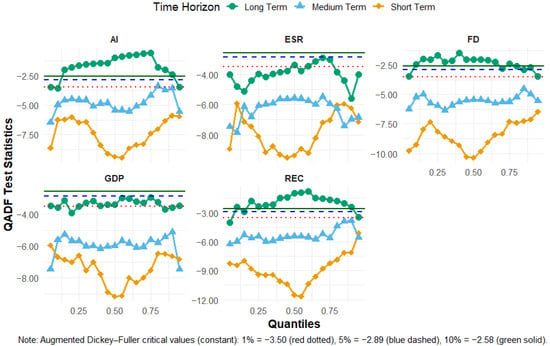

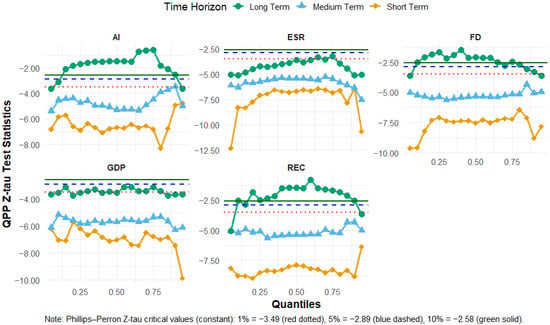

4.1. Wavelet Quantile Unit Root Test Results

The Wavelet Quantile ADF and Wavelet Quantile Phillips-Perron (WQPP) test results presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6 confirm that all variables—AI, ESR, FD, GDP, and REC—are stationary across most quantiles and time horizons. Test statistics consistently fall below the critical values, particularly in the short- and medium-term, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis of a unit root. While short-term components display greater variability, long-term components are relatively stable. Unlike traditional ADF and PP tests, WQADF and WQPP account for nonlinearities, distributional asymmetries, and time-scale variations, making them more effective in detecting localized stationarity [45]. These results validate the use of wavelet quantile-based techniques in modeling the dynamic behavior of the variables.

Figure 5.

Wavelet Quantile ADF Test Results.

Figure 6.

WQPP Results.

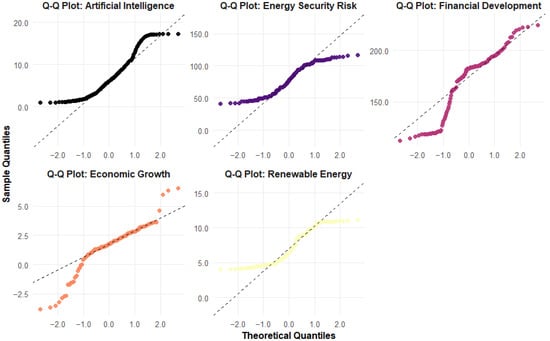

4.2. Wavelet Cross-Quantile Regression

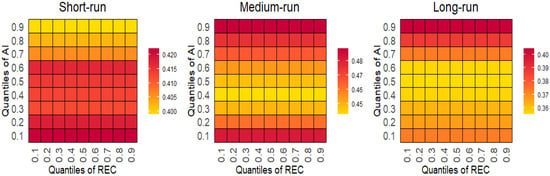

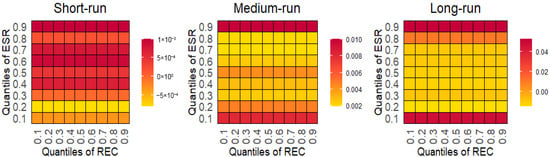

In the subsequent stage of the analysis, we employed the recently developed Wavelet Cross Quantile Regression (WCQR) technique to examine how AI, GDP, ESR, and FD influence Renewable Energy Consumption (REC). The WQR approach is particularly effective for handling nonlinear and non-normally distributed data. Unlike traditional Quantile Regression (QR), which does not consider time-scale dynamics, WQR captures effects across short-, medium-, and long-term periods, making it especially valuable for designing time-sensitive policies. The outcomes of the WQR analysis are illustrated in Figure 7, where the horizontal axis denotes the quantiles of REC, and the vertical axis represents the regression coefficients across different time scales.

Figure 7.

WCQR between REC and AI.

Figure 7 illustrates the wavelet cross-quantile relationship between Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Renewable Energy Consumption (REC) across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons. In the short run, AI exerts a relatively uniform and moderate positive impact on REC across most quantiles, with slightly stronger effects at higher AI quantiles (e.g., 0.7–0.9), as indicated by the shift toward darker red shades. The medium run presents a more intensified and consistent positive relationship, particularly around the central quantiles (0.3–0.7) of both AI and REC, suggesting that AI has its strongest influence during average conditions. In the long run, the effect of AI on REC slightly decreases in magnitude compared to the medium run, though it remains consistently positive across all quantile combinations.

Contrary to the original claim of increasing impact over time, the heatmaps show that the medium-term period exhibits the strongest positive effect, not the long-term one. Nonetheless, the consistently positive influence of AI on REC across all time horizons supports the idea that AI contributes to enhancing renewable energy utilization in the U.S. This aligns with prior studies [54,55], which emphasize AI’s potential to optimize energy usage patterns, improve grid integration, and enhance the efficiency of storage systems [56]. By forecasting demand, managing storage systems, and simulating advanced RE designs, AI continues to play a pivotal role in supporting clean energy transitions.

Figure 8 displays the cross-quantile relationship between Energy Security Risk (ESR) and Renewable Energy Consumption (REC) across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons in the United States. In the short run, ESR exhibits a mildly negative to neutral effect on REC, particularly at the lower quantiles of ESR (0.1–0.3), as shown by the yellow-orange gradients. In the medium term, the impact becomes more positive and widespread, especially around the mid-quantiles (0.3–0.7), indicating that as energy security stabilizes, REC improves. In the long run, the effect of ESR on REC becomes consistently positive across most quantiles, with stronger intensities seen in the upper quantiles of ESR and REC. This progression suggests that the initially weak or negative effects of ESR on REC dissipate over time, giving way to more favorable dynamics in the long term. These findings partially challenge the initial interpretation claiming a strong negative impact across all periods. Instead, the plots show a transition from negligible/negative effects in the short term to positive associations in the medium and long term. This evolution aligns with earlier research [25,45] which emphasizes that while energy security concerns initially pose a barrier to RE expansion, their long-run resolution—through stable policy, regulatory reforms, and risk mitigation—can facilitate RE growth. Moreover, addressing geopolitical risks, improving cybersecurity resilience, and strengthening legislative support may reduce investor uncertainty, lower capital costs, and increase confidence in RE infrastructure [31].

Figure 8.

WCQR between RE and ESR.

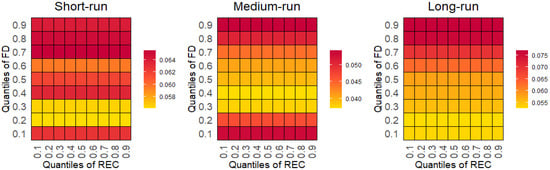

Figure 9 illustrates the impact of Financial Development (FD) on Renewable Energy Consumption (REC) across quantiles and time horizons. In the short run, FD demonstrates a consistently positive and relatively strong effect on REC across all quantiles, especially at higher levels of FD (quantiles 0.6–0.9), as reflected by darker red gradients. In the medium run, the positive relationship persists, particularly concentrated around the mid-quantiles (0.3–0.7), suggesting that FD remains an important driver of REC during average conditions. Interestingly, in the long run, the effect of FD intensifies further, especially at lower quantiles of FD and REC, implying that financial deepening becomes increasingly effective over time in supporting renewable energy uptake across broader distributional ranges. Contrary to the original interpretation, the heatmaps show that the impact of FD does not weaken but rather becomes more pronounced in the long term, particularly for lower quantiles. These results emphasize the persistent and growing role of FD in fostering REC in the U.S., in line with previous [30,32,51]. Enhanced financial systems lower the cost of capital and improve access to funding, making RE projects more financially viable. Moreover, innovative instruments such as green bonds, renewable energy funds, and RE-specific financial products help channel investment into the clean energy sector, reduce financing risk, and accelerate the transition to sustainable energy.

Figure 9.

WCQR between REC and FD.

Figure 10 illustrates the dynamic impact of economic growth (GDP) on renewable energy consumption (REC) across different quantiles and time horizons. In the short run, GDP shows a consistently negative effect on REC across all quantiles, particularly concentrated between the 0.4 and 0.7 quantiles, as reflected in the darker red tones. However, in the medium term, the relationship becomes more neutral to slightly positive, especially in the mid-quantile ranges, suggesting a transitional phase where the impact of GDP on REC begins to shift. In the long run, the relationship turns decisively positive, with the strongest effects observed between the 0.3 and 0.7 quantiles of both GDP and REC, indicating that over time, economic growth significantly supports the expansion of renewable energy. Contrary to the original interpretation which suggested a weakening influence in the long term, the WCQR plots show a clear strengthening of the positive effect of GDP on REC over time. This finding aligns with previous studies [6,57], which highlight how expanding economies drive energy demand and facilitate investment in renewable infrastructure. Economic growth often leads to increased funding for R&D, lowering the cost of technologies like wind turbines, solar panels, and energy storage systems [43]. It also fosters greater public and private awareness of the environmental costs of fossil fuels, encouraging a transition toward sustainable energy sources [58]. As a result, economic expansion not only raises energy demand but also enhances the financial and technological conditions necessary for scaling renewable energy adoption.

4.3. Robustness Tests

Discussion of the Findings

To verify the consistency of the WCQR results, two additional robustness checks were performed. First, the Dynamic ARDL model was estimated to assess both the short-run and long-run interactions among the variables. Table 3 presents the long-run and short-run estimates of the ARDL model used as a robustness check for the WCQR findings. The long-run results show that AI, ESR, FD, and GDP all exert statistically significant positive influences on renewable energy consumption (REC). Specifically, AI demonstrates a strong long-run elasticity (0.35, p < 0.01), indicating that technological enhancement significantly strengthens renewable energy adoption by improving system efficiency and operational intelligence. These results are consistent with recent studies showing that digitalisation and AI-driven optimisation significantly accelerate clean energy integration [25,59]. ESR also shows a positive effect (0.18, p < 0.05), suggesting that heightened energy supply risks encourage a structural shift toward more stable renewable sources in the long run, which aligns with evidence from energy insecurity–driven transitions reported by [60,61].

Financial development records the largest long-run effect (0.42, p < 0.01), confirming that deeper financial markets enhance access to capital, reduce financing constraints, and facilitate large-scale investment in renewable infrastructure. This finding is supported by empirical research demonstrating that financial deepening promotes green investment and renewable deployment across advanced economies [5,62,63]. GDP exerts a moderate but positive long-run elasticity (0.15, p < 0.10), implying that economic expansion creates capacity for renewable deployment—consistent with growth-driven energy transition patterns observed in recent empirical analyses [11,37].

The short-run dynamics reveal mixed immediate responses. AI (0.12, p < 0.01) and FD (0.21, p < 0.01) positively and significantly affect short-run changes in REC, indicating rapid system responsiveness to technological and financial conditions. Similar short-run elasticities are reported in studies examining technology–energy interactions [64] and green finance mechanisms [65,66]. ESR exhibits a negative short-run effect (−0.07, p < 0.05), implying temporary disruptions in renewable investments during periods of heightened risk or market volatility. This aligns with evidence suggesting that geopolitical shocks and market turbulence temporarily reduce renewable investment flows [67,68,69,70]. The effect of GDP (−0.05, p < 0.10) is also negative and marginally significant, suggesting that in the short term, economic activity may temporarily prioritise conventional energy to meet immediate demand, consistent with findings by [47]. The ECM (−1) coefficient (−0.32, p < 0.01) is negative and highly significant, confirming the presence of a stable long-run equilibrium relationship. The magnitude indicates that approximately 32% of short-run deviations from the long-run path are corrected within one period, implying a moderate speed of adjustment.

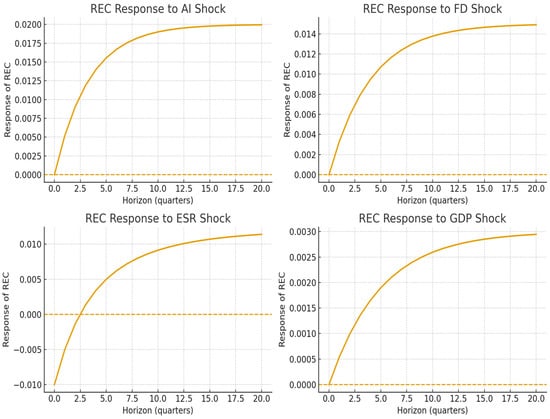

Second, the TVP-SV-VAR model (Figure 11) was employed to capture time-varying relationships and structural dynamics among the variables [71]. The impulse response results show that the influence of artificial intelligence on renewable energy consumption is consistently positive and becomes stronger over longer horizons, indicating that technological diffusion and digital optimization increasingly support clean energy adoption. Similarly, the positive effect of financial development intensifies over time, reflecting the growing role of credit access, green financing instruments, and investment capacity in sustaining renewable energy transitions. In contrast, the impact of energy security risk initially exerts a negative influence, suggesting short-run reliance on conventional energy sources when stability concerns are high. However, as policies mature and market structures adjust, this effect gradually shifts toward a positive contribution, implying that long-term improvements in energy planning and resilience encourage diversification toward renewables. The response of renewable energy consumption to economic growth remains positive but relatively moderate, suggesting that growth facilitates the clean energy transition primarily when supported by innovation and financial development. Overall, these dynamic patterns validate the WCQR results, confirming that the relationships are persistent, time-varying, and robust across model specifications.

Figure 11.

TVP-SV-VAR.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

This study investigates the time-varying effects of artificial intelligence (AI), financial development (FD), energy security risk (ESR), and economic growth (GDP) on renewable energy consumption (REC) in the United States using Wavelet Cross-Quantile Regression (WCQR), ARDL, and TVP-SV-VAR techniques. The findings provide robust evidence that these factors collectively shape the long-term trajectory of the U.S. renewable energy transition. The empirical results show that AI plays a consistently positive role in enhancing REC across all time horizons, with its influence being strongest in the medium run. This underscores the transformative value of AI-enabled technologies—such as smart grid optimization, predictive maintenance, and intelligent storage—in improving the efficiency and reliability of renewable energy systems. Similarly, FD emerges as a long-run driver of REC, demonstrating that a deep and flexible financial system is essential for mobilizing capital, reducing investment risks, and scaling renewable energy deployment. The effects of ESR and GDP are more nuanced. ESR exhibits short-term disruptions that weaken REC but becomes a strong positive determinant in the long run, indicating that persistent energy insecurity ultimately encourages diversification toward renewables. GDP also shifts from having adverse short-run effects—likely due to increased reliance on conventional energy—to supporting REC in the long run as economic expansion enables structural shifts toward cleaner energy.

5.2. Policy Implications

The empirical results of this study offer several important practical and policy implications for the United States as it advances its renewable energy agenda. First, the consistent positive influence of artificial intelligence on renewable energy consumption highlights the need for greater investment in AI-driven energy technologies. Policymakers should encourage the integration of AI into grid management, energy storage, and demand-response systems by providing targeted incentives, tax credits, or public–private partnerships that support digital innovation. Energy companies can also leverage AI tools to optimize generation efficiency, reduce operational costs, and improve forecasting accuracy, thereby strengthening the reliability of renewable energy systems.

The strong long-run contribution of financial development to renewable energy consumption underscores the importance of deepening financial markets and expanding access to sustainable financing instruments. Policymakers should promote the development of green bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and climate-related financial disclosure frameworks to mobilize private capital toward renewable energy projects. Strengthening the regulatory environment and reducing financial barriers can help de-risk large-scale renewable investments and attract both domestic and foreign investors. Improving financial inclusion can also empower households and small businesses to adopt decentralized renewable technologies such as rooftop solar and microgrids.

The findings regarding energy security risk demonstrate that while short-term disruptions may temporarily weaken renewable energy consumption, long-run energy insecurity ultimately accelerates the shift away from fossil fuel reliance. This suggests that policymakers should adopt proactive strategies to reduce vulnerability to energy shocks by diversifying the energy mix, expanding grid resilience programs, and accelerating the deployment of renewable infrastructure. Strengthening strategic energy reserves, expanding inter-state transmission networks, and incentivizing distributed generation can further enhance national security while supporting clean energy goals.

Economic growth also plays a dual role that policymakers must consider. While growth initially increases reliance on conventional energy sources, the long-run relationship indicates that sustained economic expansion supports renewable energy adoption as economies transition toward cleaner production structures. Therefore, growth-oriented policies should be coupled with environmental objectives to ensure that economic expansion reinforces—rather than undermines—the renewable energy transition. This can be achieved by embedding sustainability requirements into industrial policies, offering green investment tax credits, and supporting innovation ecosystems that integrate AI, advanced manufacturing, and clean energy technologies.

5.3. Future Research Directions

Although this study provides comprehensive insights, several avenues remain for future work. First, future studies could examine sector-specific renewable energy responses to AI and FD, such as wind, solar, or geothermal systems. Second, the analysis could be extended to multi-country comparisons to assess whether similar patterns exist in other advanced or emerging economies. Third, incorporating additional variables—such as climate policies, carbon pricing, or technological innovation indices—may provide deeper insights into the mechanisms driving REC. Finally, future research could employ machine learning-based forecasting techniques to enhance predictive accuracy regarding energy transitions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H. and Y.T.; methodology, X.L.; software, W.D.; validation, X.L.; formal analysis, Y.T.; investigation, Y.T.; data curation, W.D.; writing—original draft preparation, W.D.; writing—review and editing, C.H.; supervision, C.H.; project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- EIA. Energy Information Administration. Renewable Energy Explained; United States Renewable Energy: Washington, DC, 2024. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/renewable-sources (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Eurostat. EU and Russia Trade Profile. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=558089#:~:text=The%20value%20of%20exports%20to,2023%20at%20%E2%82%AC0.2%20billion (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- European Commission A European Green Deal, Striving to Be the First Climate-Neutral Continent. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Shahbaz, M.; Hye, Q.M.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Leitão, N.C. Economic growth, energy consumption, financial development, international trade and CO2 emissions in Indonesia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Eweade, B.S.; Özkan, O.; Uzun Ozsahin, D. Effects of energy security and financial development on load capacity factor in the USA: A wavelet kernel-based regularized least squares approach. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 4215–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Solarin, S.A.; Ozturk, I. Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis and the Role of Globalization in Selected African Countries. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, K.R.; Hussain, K.; Haddad, A.M.; Salman, A.; Ozturk, I. The Role of Financial Development and Technological Innovation Towards Sustainable Development in Pakistan: Fresh Insights from Consumption and Territory-Based Emissions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovski, K.; Marinucci, N. Policy uncertainty and renewable energy: Exploring the implications for global energy transitions, energy security, and environmental risk management. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel Tugcu, C.; Menegaki, A.N. The impact of renewable energy generation on energy security: Evidence from the G7 countries. Gondwana Res. 2024, 125, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-W.; Chung, Y.-F.; Wu, T.-H. Analyzing the relationship between energy security performance and decoupling of economic growth from CO2 emissions for OECD countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, L.; Afaq, A.; Arora, G.K.; Khan, N. Artificial intelligence for carbon emissions using system of systems theory. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 76, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, K.; Fujii, H.; Liu, J. Artificial intelligence and energy intensity in China’s industrial sector: Effect and transmission channel. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 70, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.L.D.; Hille, E.; Nasir, M.A. Diversification in the age of the 4th industrial revolution: The role of artificial intelligence, green bonds and cryptocurrencies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 159, 120188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.K.; Abakah, E.J.A.; Le, T.-L.; Leyva-de la Hiz, D.I. Markov-switching dependence between artificial intelligence and carbon price: The role of policy uncertainty in the era of the 4th industrial revolution and the effect of COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintande, O.J.; Olubusoye, O.E.; Adenikinju, A.F.; Olanrewaju, B.T. Modeling the determinants of renewable energy consumption: Evidence from the five most populous nations in Africa. Energy 2020, 206, 117992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, N.; Brandt, N. Determinants of households’ investment in energy efficiency and renewables: Evidence from the OECD survey on household environmental behaviour and attitudes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Altinoz, B.; Dogan, E. Analyzing the determinants of carbon emissions from transportation in European countries: The role of renewable energy and urbanization. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2020, 22, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekun, F.V.; Alola, A.A. Determinants of renewable energy consumption in agrarian Sub-Sahara African economies. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2022, 7, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przychodzen, W.; Przychodzen, J. Determinants of renewable energy production in transition economies: A panel data approach. Energy 2020, 191, 116583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Olanrewaju, V.O.; Uzun, B. Safe havens or fragile investments? Navigating sustainable energy assets in times of policy uncertainty. Investig. Anal. J. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweade, B.S.; Akadiri, A.C.; Olusoga, K.O.; Bamidele, R.O. The symbiotic effects of energy consumption, globalization, and combustible renewables and waste on ecological footprint in the United Kingdom. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2024; Volume 48, pp. 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. The Origins of Endogenous Growth. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. The impact of financial development on energy consumption in emerging economies. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2528–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Guo, J.; Zhou, H. Digital financial inclusion development, investment diversification, and household extreme portfolio risk. Account. Finance 2021, 61, 6225–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweade, B.S. Do Investments in Artificial Intelligence, Economic Policy Uncertainty and Economic Growth Hurt or Help Biodiversity in the United States? Geol. J. 2025, gj.70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.K.; Doğan, B.; Abakah, E.J.A.; Ghosh, S.; Albeni, M. Impact of economic policy uncertainty, geopolitical risk, and economic complexity on carbon emissions and ecological footprint: An investigation of the E7 countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 34406–34427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Özkan, O.; Olanrewaju, V.O.; Uzun, B. Do fossil-fuel subsidies, Fintech innovation, and digital ICT transform ecological quality in Turkey? Evidence from modified cross-quantile regression. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Acheampong, A.O. Modelling the globalization-CO2 emission nexus in Australia: Evidence from quantile-on-quantile approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 9867–9882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenker, R.; Bassett, G. Regression Quantiles. Econometrica 1978, 46, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, N.; Zhou, H. Oil prices, US stock return, and the dependence between their quantiles. J. Bank. Finance 2015, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troster, V. Testing for Granger-causality in quantiles. Econom. Rev. 2018, 37, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.K.; Ghosh, S.; Doğan, B.; Nguyen, N.H.; Shahbaz, M. Energy security as new determinant of renewable energy: The role of economic complexity in top energy users. Energy 2023, 263, 125799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Shahbaz, M.; Bashir, M.F.; Abbas, S.; Ghosh, S. Formulating energy security strategies for a sustainable environment: Evidence from the newly industrialized economies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 184, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.A.; Eweade, B.S.; Awosusi, A.A.; Kirikkaleli, D. Beyond Fossil Fuels: How Iceland’s Oil Efficiency, Hydro Energy, and Fiscal Decentralization Propel a Cleaner Environment: Evidence from Wavelet Quantile Methods. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 28, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.G.; Afloarei Nucu, A.E. The effect of financial development on renewable energy consumption. A panel data approach. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Li, K.; Qin, M.; Albu, L.L. Towards energy security: Could renewable energy endure uncertainties in the energy market? Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 86, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-W.; Wu, Y.; Qin, M. Preserving energy security: Can renewable energy withstand the energy-related uncertainty risk? Energy 2025, 320, 135349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.T.; Ullah, S.; Sohail, S. How does the circular economy affect energy security and renewable energy development? Energy 2025, 320, 135348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, M.; Sarıgül, S.S.; Topcu, B.A.; Alvarado, R.; Karataser, B. Does globalization mitigate environmental degradation in selected emerging economies? assessment of the role of financial development, economic growth, renewable energy consumption and urbanization. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 100340–100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Chenggang, Y.; Hussain, J.; Kui, Z. Impact of technological innovation, financial development and foreign direct investment on renewable energy, non-renewable energy and the environment in belt & Road Initiative countries. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevinç, H.; Kizildere, C.; Eweade, B.S.; Gyamfi, B.A. Drivers of ecological quality: Do environmental policy stringency and urbanization play a role? Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslej, N.; Fattorini, L.; Perrault, R.; Gil, Y.; Parli, V.; Kariuki, N.; Capstick, E.; Reuel, A.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Etchemendy, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtarov, S.; Yüksel, S.; Dinçer, H. The impact of financial development on renewable energy consumption: Evidence from Turkey. Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, P.; Sethi, L.; Sethi, N. Balancing India’s energy trilemma: Assessing the role of renewable energy and green technology innovation for sustainable development. Energy 2024, 308, 132842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, V.O.; Adebayo, T.S.; Uzun, B. Navigating the impact of ESG sustainability uncertainty on fossil fuel prices: Evidence from wavelet cross-quantile regression. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Wang, Y.; Ali, S.; Haider, M.A.; Amin, N. Shifting to a green economy: Asymmetric macroeconomic determinants of renewable energy production in Pakistan. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Okolo, C.V.; Ugwuoke, I.C.; Kolani, K. Research on influencing factors of renewable energy, energy efficiency, on technological innovation. Does trade, investment and human capital development matter? Energy Policy 2022, 160, 112718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Nouman, M.; Popp, J.; Khan, M.A.; Ur Rehman, F.; Oláh, J. Link between Technically Derived Energy Efficiency and Ecological Footprint: Empirical Evidence from the ASEAN Region. Energies 2021, 14, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, O.; Usman, O.; Eweade, B.S. Global evidence on the energy–environment dilemma: The role of energy-related uncertainty across diverse environmental indicators. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 1128–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishti, M.Z.; Xia, X.; Du, A.M.; Özkan, O. Digital financial inclusion, the belt and road initiative, and the Paris agreement: Impacts on energy transition grid costs. Finance Res. Lett. 2025, 72, 106517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Cointegration and speed of convergence to equilibrium. J. Econom. 1996, 71, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Özkan, O. Investigating the influence of socioeconomic conditions, renewable energy and eco-innovation on environmental degradation in the United States: A wavelet quantile-based analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanco-Martínez, J.M. VisualDom: An R package for estimating dominant variables in dynamical systems. Softw. Impacts 2023, 16, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, D.B.; Walden, A.T. Wavelet Methods for Time Series Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; 628p, ISBN 978-0-521-68508-5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Shi, C.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H. Evaluating Dynamic Conditional Quantile Treatment Effects with Applications in Ridesharing. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2024, 119, 1736–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broock, W.A.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Dechert, W.D.; LeBaron, B. A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Econom. Rev. 1996, 15, 197–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F.; Elsayed, A.H.; Omri, A. Key drivers of renewable energy deployment in the MENA Region: Empirical evidence using panel quantile regression. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2021, 57, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R.; Xiao, Z. Unit Root Quantile Autoregression Inference. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004, 99, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.N.; Nazir, M.S.; Tao, H.; Cao, S.; Ji, R.; Jiang, M.; Yao, L. Integration of energy storage system and renewable energy sources based on artificial intelligence: An overview. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şerban, A.C.; Lytras, M.D. Artificial Intelligence for Smart Renewable Energy Sector in Europe—Smart Energy Infrastructures for Next Generation Smart Cities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 77364–77377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Galal, M. Using Artificial neural networks to recognize the determinants of economic growth: New approach “evidence from developing countries”. Indian J. Econ. Bus. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Eweade, B.S.; Aghazadeh, S.; Bamidele, R.O.; Xu, Y. Pathways to environmental sustainability: Do fintech, natural resources, and environmental patents matter in E−7 nations? Renew. Energy 2025, 247, 122987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, B.M.; Taspinar, N.; Gokmenoglu, K.K. The impact of financial development and economic growth on renewable energy consumption: Empirical analysis of India. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 663, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirikkaleli, D.; Adebayo, T.S.; Khan, Z.; Ali, S. Does globalization matter for ecological footprint in Turkey? Evidence from dual adjustment approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 14009–14017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Rana, N. The Convergence of Nanotechnology and Artificial Intelligence: Unlocking Future Innovations. Recent Innov. Chem. Eng. Former. Recent Pat. Chem. Eng. 2025, 18, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Yong, L.; Ashraf, J. Financial development and energy security risk: Do human capital and institutional quality make a difference? Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2025, 25, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, M.S.; Al-Maadid, A.; Bergougui, B. Climate Change and Energy Security Risk: Do Green Patents, Institutional Quality, and Human Capital Make a Difference? Sustain. Dev. 2025, sd.70244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ramzan, M.; Awosusi, A.A.; Eweade, B.S.; Ojekemi, O.S. Unraveling causal dynamics: Exploring resource efficiency and biomass utilization in Malaysia’s context. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Khan, K.A.; Eweade, B.S.; Adebayo, T.S. Role of eco-innovation and financial globalization on ecological quality in China: A wavelet analysis. Energy Environ. 2025, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Siddik, A.B.; Guo, L.; Li, H. Dynamic relationship among climate policy uncertainty, oil price and renewable energy consumption—Findings from TVP-SV-VAR approach. Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).