Abstract

This study investigates the key success factors of IT project management in an emerging, innovation-oriented economy using evidence from Kazakhstan. Drawing on expert interviews and an anonymous enterprise survey, we rank 59 processes across the project life cycle and test three hypotheses concerning the roles of human factors and professional governance. The results confirm broad alignment with success factors commonly reported in mature economies yet reveal a distinctive pattern at earlier maturity stages: team composition, communication, and collaboration have a stronger impact on project success than formal controlling and detailed financial governance. We also identify a substantial gap between the declared importance of success factors and their actual implementation—particularly in integration-stage budgeting, acceptance testing and quality assurance, and lessons-learned practices—highlighting how limited practical experience constrains the adoption of governance routines. The findings refine contingency perspectives on project success by positioning key success factors along a development trajectory in which people-centric capabilities serve as prerequisites for the subsequent effectiveness of “hard” project-management methods. The study advances understanding of the role of IT project management in countries at an early stage of developing an innovation-driven economy.

1. Introduction

Long-term sustainable economic growth remains a major challenge for countries emerging from centralized, non-democratic, non-market systems. The modern, digitally driven economy requires large numbers of IT specialists. However, shortages of qualified experts and limited experience in implementing IT projects constrain the development of an innovation-driven economy. Effective IT project management is therefore fundamental to building a technology-based economy. In Kazakhstan, it is particularly important, as it underpins the success of national digitalization programs and the transition to a knowledge-based economy. In the absence of research that accounts for the specific context of post-socialist economies, developing context-appropriate approaches to IT project management becomes a key requirement for sustainable technological development. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies on success factors in IT project management in economies that have transitioned from the former socialist bloc.

Project management (PM) is a managerial approach that enables the execution of specific tasks within or across enterprises. It aims to deliver the intended project objectives while avoiding unintended adverse effects. PM emphasizes achieving clearly defined results and the necessary steps to reach them. Project activities follow a process-based approach, integrating implementation and support processes through management processes that include goal setting, planning, organizing, and control [1].

Project management is a rapidly evolving discipline focused on “the ability to define and set goals, plan their achievement, and execute the plan with accountability and control” [2]. Today, PM approaches are formalized and codified across specialized methodologies such as Agile, PRINCE2, and plan-driven (Waterfall) models [3,4]. Flexible, iterative methods follow step-by-step development cycles to quickly produce functional application versions and deliver them to customers for feedback [5]. Each methodology requires specific skill sets, commonly validated through project-management certifications; candidates are expected to demonstrate competencies that enable professional participation in project activities [6,7].

The role of project management in fostering the sustainable development of enterprises is pivotal. According to several authors, PM serves as a vehicle for implementing organizational change [8]. A growing body of literature highlights the contribution of projects to the sustainable development of organizations and society [9,10,11]. Contemporary project management demands capabilities to manage complexity and uncertainty in dynamic business and technological environments.

Recent studies indicate that sustainable IT project management typically combines Agile practices, ESG frameworks, green IT strategies, and data-driven approaches. Zakrzewska et al. [12] show that Agile methods such as design thinking and team rituals enhance efficiency and social sustainability, while Ahmad and Al-Baik [13] highlight the importance of trust, transparency, and organizational culture in large-scale Agile projects. Kyriakogkonas et al. [14] propose integrating ESG criteria into project governance, thereby making sustainability a formal responsibility of project leaders, whereas Ebirim et al. [15] demonstrate that holistic planning and stakeholder engagement are essential for reducing the environmental footprint of data center projects. Complementing these perspectives, Pantović et al. [16] argue that data-driven decision-making promotes sustainability by enabling better resource allocation, risk mitigation, and process optimization in IT projects. Gaweł et al. [17] propose combining risk-mitigation decision-making methods for sustainable project evaluation.

The literature suggests that sustainable IT project management succeeds when operational agility, responsible governance, environmental awareness, and analytics-based decision-making are integrated into a holistic framework that ensures projects are delivered not only on time and within budget but also with enduring social and environmental value.

Scope management—encompassing boundary setting and responsibility allocation—is essential for maintaining control and performance [18,19]. Tools and methods of PM are increasingly evaluated in terms of their strategic value [20]. In Kazakhstan, effective IT project management has been linked to greater technological stability and profitability, pointing to critical success factors embedded in specific processes.

This study aims to identify the key success factors for managing enterprise IT projects in economies pursuing innovative and sustainable growth, using Kazakhstan as the focal case. Despite the limited body of systematic research and practical experience in IT project management, the need to develop this capability in Kazakhstan is increasingly urgent, as effective project management is a prerequisite for successful digital transformation and the emergence of an innovation-driven economy. At the outset, we did not know whether well-defined IT project-management success factors existed, whether they exhibited country-specific characteristics, and whether they differed from those identified in developed economies. Potential success factors can be derived from global project-management standards—A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge [21], The Standard for Portfolio Management [22], and The Standard for Program Management [23]. These standards were formulated in leading, innovation-oriented economies. It remains unclear whether they apply to the same extent in countries pursuing an innovation-driven trajectory. It is also important to examine whether people-related factors are as consequential for project success as formal project-management methods.

This study examines the relationship between process application in Kazakhstani enterprises and IT project success, testing the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1:

Key IT project-management processes can be identified and ranked.

Hypothesis 2:

A well-composed, skilled team is essential to IT projects success.

Hypothesis 3:

Professional process application and communication drive IT projects success.

We employed expert interviews and an anonymous survey of Kazakhstani enterprises.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on project-management standards, methodologies, and international practices, focusing on their relevance to sustainable development. It also analyzes the main challenges of IT project management in Kazakhstan during its transition toward an innovation-driven economy. Section 3 presents the materials and methods. Section 4 reports findings from in-depth expert interviews that identify key practical success factors and presents survey results from IT project professionals in Kazakhstani enterprises, examining the implementation of project-management processes and their perceived effectiveness. Section 5 discusses the confirmation of the proposed hypotheses and reflects on implications for sustainable project management. Section 6 concludes with recommendations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Standards of Project Management

Project management, applied across industries, is an integral part of organizational management systems whose tools are effectively used at both governmental and private levels. When implemented alongside innovation in economic and production sectors, effective and professional project management enables sound planning and successful delivery. It optimizes time and financial resources while accounting for human factors, without compromising the planned quality of project outcomes [24].

Modern project management relies on international standards that integrate best practices, tools, and methodologies. The PMBOK® Guide developed by the Project Management Institute [21] provides a foundational framework adaptable to diverse industries. The Standard for Portfolio Management [22] and the Standard for Program Management [23] support coordination, communication, and accountability in complex project environments. The Organizational Project Management Maturity Model (OPM3) links project activities to strategic goals through maturity assessments. The ISO 9000 series [25] emphasizes quality management, continuous improvement, and auditing standards. The UK’s APM Body of Knowledge (BoK) defines professional competencies through its “Five Dimensions of Professionalism” and offers certified qualifications [26].

In summary, standards such as PMI’s OPM3, ISO 9000 series, and APM BoK strengthen structured project execution, quality assurance, and professional development—enhancing organizational efficiency and ensuring reliable outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Standards used in project management.

Project management follows a classical five-phase model consisting of initiation, planning, development, implementation and testing, and monitoring and completion. Over time, project management has evolved into two main approaches: traditional and flexible. Traditional methods (e.g., PRINCE2) follow linear, milestone-based frameworks suited for predictable contexts [27]. Flexible approaches such as Agile, Scrum, Lean, Kanban, and Six Sigma emphasize adaptability, iteration, and continuous stakeholder feedback [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Agile enables incremental development, while Scrum structures this process through sprints and well-defined roles [35]. Lean focuses on eliminating waste [36], and Six Sigma improves quality through data-driven analysis [37]. PRINCE2 provides a scalable, process-oriented framework. Today, hybrid models combine structure and agility to enhance efficiency and strategic alignment [38,39].

In Kazakhstan, IT project management remains at an early stage of development: traditional methods are used mainly in government and large corporate projects, while flexible approaches—and their integration with modern technologies such as Agile, AI, and blockchain—are still limited. An effective combination of traditional and flexible methods is becoming a key factor for the successful digital transformation and growing competitiveness of Kazakhstan’s IT projects. These issues are further discussed in Section 2.2 and Section 2.3.

2.2. Comparative Analysis Between Selected Countries Using Project Management

In modern socio-economic conditions, building an effective project management system and enhancing its efficiency rely on the use of advanced information and communication technologies and contemporary management approaches. These provide toolsets that improve the quality of project management, ensure decision transparency, and facilitate public access to information. Consequently, project management methods are increasingly applied in both the public and private sectors, enabling the comprehensive coordination of projects that deliver socially significant outcomes regardless of their scope.

Although national approaches differ, the challenges faced by individual countries are often strikingly similar. Each country seeks to adapt globally recognized methodologies to its own cultural, organizational, and community context, yet these adaptations do not always yield the desired results. Findings from high-maturity contexts are not invalid but rather conditional—they presuppose stable teams, clearly defined roles, and prior experience, which may be absent in early-stage ecosystems.

The following section presents a comparative analysis of IT project management theory and practice across several countries. We begin with Japan, representing a highly mature project management environment, and then discuss countries originating from the former socialist bloc, including Kazakhstan, where modern project management practices remain at an early stage of development.

Japan. Japanese project management is internationally recognized, with the P2M standard, developed by Ohara in 2001 [40], serving as the first formal framework for innovation-oriented enterprises. Managed by the Project Management Association of Japan, P2M provides a strategic foundation for enhancing corporate value through flexible, adaptive methodologies. It integrates entry-level project management, program management, and eleven segment-management structures designed to address complexity, uncertainty, and scalability.

P2M is applied across key industries—construction, manufacturing, and information technology—considered vital to Japan’s innovation-driven economy. The Kaikaku Project Management (KPM) model, an advanced version of P2M, emerged as part of Japan’s post-1990s reforms. KPM emphasizes kakushin (innovation), kaihatsu (development), and kaizen (improvement), fostering well-structured project systems that consistently deliver successful outcomes.

P2M covers the full project lifecycle—from idea generation and planning to implementation, investment, recovery, and value creation. In manufacturing, project management supports production-system innovation, AI integration, and automation, focusing on cost reduction, efficiency, and productivity gains. However, maintaining sustainable efficiency remains a continuing challenge.

In IT, the KPM knowledge-based platform enables project visualization, knowledge sharing, and innovation-driven cost and risk reduction. Applications extend to disaster prevention (e.g., earthquake prediction) and to corporate software and service innovation following models such as the 3S scheme. Overall, the P2M and KPM frameworks have proven effective for managing complex projects, supporting competitiveness and sustained innovation across Japan.

Czech Republic. Since the early 2000s, the Czech Republic has increasingly regarded project management as a key instrument for improving governance and organizational efficiency. Foreign investment, innovation pressures, and access to EU funding have driven the adoption of modern methodologies [41]. Project management is most widespread in information technology, telecommunications, and construction, although challenges in implementation remain.

A 2012 national survey of 178 project and portfolio managers from large organizations (budgets above CZK 10 million and more than 100 employees) assessed project success, tool usage, and training practices [42]. The results showed high familiarity (90–98%) with best practices in structuring, time planning, and evaluation, while 43% of respondents reported limited knowledge of Agile methods.

Russian Federation. Similarly to the Czech Republic, Russia began implementing project management in the early 2000s. Over the past two decades, a variety of approaches have been adopted, with strong emphasis on learning from international experience due to a historical lag in domestic practice—especially in information and communication technologies. The legacy of the administrative-command management style hindered large-scale projects, and despite abundant resources, the demand for such projects remained limited [43].

Significant progress occurred between 2000 and 2010, marked by proactive project development, business-process transformation, and growing demand for IT training. Initially, performance-stability issues were common, but project management gradually adapted to industry specifics and shifted toward flexible methodologies. A notable milestone was the successful execution of the 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, recognized internationally as one of Russia’s most successful large-scale projects.

Drawing on global practices, Russia introduced tools such as outsourcing, benchmarking, and re-engineering to enhance project performance. However, persistent challenges include a shortage of certified professionals, low trust in consulting firms, weak motivation to adopt innovations, and resistance to change—often driven by fear or stress at the middle-management level.

Croatia. Certification of project managers in Croatia, aligned with ISO 17024 [44] and administered by IPMA and PMI, plays a crucial role in advancing project management in the country. Croatia considers certification a fundamental component of effective project implementation processes. A national study with statistically significant results examined the impact of certification on the development of project management and assessed the country’s overall project-management maturity.

The research, conducted through semi-structured interviews in two thematic areas—certification processes and the evolution of project management as a profession—revealed that certification enhances knowledge, skills, and competitiveness in the national market. It also facilitates the transfer of accumulated experience to Croatian project managers and strengthens the recognition of project management as a professional discipline delivering higher-quality services.

Certification positively affects labor-market demand by encouraging companies to invest in certified professionals, thereby strengthening both human and structural capital through improved business processes and methodologies. Since the introduction of certification, Croatia has continuously monitored internal motivators and control parameters to guide the further development of project management nationwide.

Kazakhstan. Project management in Kazakhstan originated in the mid-1990s and continues to evolve in alignment with international standards. Its development has been slowed by fragmented implementation and legacy practices that do not meet the needs of modern business and government, thus reducing competitiveness [45]. Some enterprises and consulting firms already apply project management methods, and international organizations have shared experience; however, communication and economic mechanisms with domestic firms remain weak.

Since 2010, the government has supported project management through major investments and international collaborations. The Technical Committee for Standardization of Project Management, operating under the Committee for Technical Regulation and Standardization, has coordinated national efforts and contributed to the 2010–2014 industrial and innovation development program. Kazakhstan is developing its own national standard harmonized with international frameworks, aligning program documentation across ministries and institutions.

A shortage of qualified specialists persists, though public and private universities now offer project management programs at all levels, and the Competence Center at the Academy of Public Administration trains senior managers [46]. The non-profit Project Manager Club, established in 2007 in Almaty, includes 157 members—academics, executives, and certified professionals (IPMA, PMI).

Despite progress, Kazakhstan still lags behind leading countries in project, portfolio, and program management. The 2010–2020 Development Program set out priorities to integrate national practices with global standards, expand education and retraining, promote motivation and certification, and strengthen cooperation between international and domestic organizations.

2.3. Prospects for Success in IT Project Management

Project management comprises a coordinated set of actions and tasks aimed at achieving specific objectives through the application of appropriate knowledge, skills, tools, and methods. The PMBOK® Guide [21], first introduced in 1983, has continuously evolved, expanding its knowledge areas across successive editions and emphasizing five process groups: initiation, planning, execution, monitoring and controlling, and closing. The Association for Project Management (APM) proposes a broader perspective that incorporates goals, strategy, technology, people, business, and environmental factors—viewing the PMI model as comparatively narrower in scope. Despite these developments, a unified theory of project management has yet to emerge, and project management (PM) and Management of Portfolios (MoP) still offer distinct perspectives on what constitutes project success [47].

Complex projects often require a multi-stage, cross-functional organization involving multiple departments and areas of specialization, which increases both vertical and horizontal differentiation. The organizational structure of a project defines relationships among participants, communication channels, coordination mechanisms, and role allocation—all of which influence both complexity and managerial effectiveness. Project managers must therefore consider the broader context and external environmental changes, adapting structures and governance mechanisms to ensure successful project execution.

In the digital era, information technology project management (IT-PM) plays a strategic role by aligning digital initiatives with governance objectives and focusing on value creation rather than mere task execution [48]. Collaboration is essential [49], yet communication gaps remain a persistent challenge [50]. Cross-sectoral experience, for example, from healthcare, highlights the importance of knowledge sharing [51]. In knowledge-intensive work such as IT, clan-based control—built on shared values and trust—enhances employee engagement [52]. Communication serves as the link between governance, teamwork, and control, while digital environments require a balanced combination of formal and informal information flows [53]. Agile methodologies further enhance adaptability through iteration and continuous stakeholder input [54].

Project size significantly affects risk: large projects struggle with coordination and integration, whereas smaller ones often bear proportionally higher strategic stakes [55]. Outsourcing relationships depend on transparency and trust [56]. The project manager occupies a central role, combining soft skills with technical expertise to ensure success [57,58].

Digital tools such as Project Management Information Systems (PMIS) facilitate coordination and integration, though well-structured communication plans remain indispensable [59]. In essence, IT-PM requires integrated governance, adaptive teams, strategic communication, and contextual control. Continued empirical research is needed to deepen understanding of these dynamics and refine success models for real-world practice.

Project Management Information Systems have evolved into comprehensive strategic platforms that integrate planning, budgeting, scheduling, and risk management based on real-time data [60]. Particularly valuable in agile and distributed environments, PMIS enhance transparency, traceability, and control [61]. Core functionalities—such as dashboards, templates, and automated scheduling—enable synchronization across teams and proactive deviation management [62]. Centralized systems replace fragmented tools, reinforcing auditability, institutional memory, and knowledge retention.

Managerial competence remains critical: communication, innovation, and customer satisfaction all depend on effective leadership [63,64]. Project leaders must also possess domain knowledge to align IT initiatives with strategic business goals [65]. Modern PMIS solutions are therefore seen as strategic assets—diagnostic tools that promote stability and interactive systems that foster agility. The next stage of their evolution will likely involve the integration of artificial intelligence, Agile analytics, and blockchain technologies.

Existing research does not point to a universally accepted set of project management success factors. Although project management standards increasingly provide up-to-date and comprehensive guidelines for managerial practices, their practical implementation in enterprises may vary considerably and often departs from the prescribed model. Standards may therefore constitute an essential reference framework, but they do not guarantee uniform outcomes when transferred into organizational practice.

According to the literature, project success is shaped by two broad categories of factors. The first group comprises human-capital-related factors, including the competencies of employees and project leaders. Within this category, communication emerges as one of the most critical components: communication among project team members, between the project manager and the team, and between the team and external stakeholders. Effective communication facilitates knowledge sharing, enhances coordination, and reduces the risk of misunderstandings that may jeopardize project execution. The role of the project leader is equally emphasized in prior studies, as leadership quality influences team motivation, decision-making, and the ability to manage risks and conflicts.

The second group of determinants includes tools, methods, and organizational practices that support project execution. These encompass formalized project management methodologies, governance procedures, documentation standards, and information systems used to monitor, coordinate, and control project activities. Appropriate methodological and technological support enhances transparency, enables more accurate planning, and strengthens the organization’s ability to respond effectively to emerging challenges.

Taken together, these findings indicate that project success results from the interplay between people-centric capabilities and formalized managerial instruments. However, the relative importance of these factors may differ across countries and organizational contexts, particularly in economies at an early stage of developing project management maturity.

Building on these insights, this study adopts a staged capability perspective—people-centric competencies, such as team composition, communication, and collaboration, which are treated as foundational success factors during the early stages of project-management maturity. These precede the so-called “hard” success factors—governance, controlling, budgeting, and formal quality assurance—that dominate in more mature project-management environments. We test this assumption within an emerging-economy context, where capability accumulation is uneven and the gap between declared and implemented success factors remains substantial. The aim of our research is to develop a comparative ranking of key success factors by project-management maturity level, identify implementation gaps in widely cited practices, and verify whether soft factors exert greater influence on project success than formal control mechanisms.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Challenges of IT Project Management During the Transition to Innovative and Sustainable Economy in Kazakhstan in the Period of Digitalization

In the early stages of IT management development across many post-Soviet countries, including Kazakhstan, enterprises began establishing dedicated IT departments to align technological efforts with strategic business goals. Although formal IT project management was still in its infancy in the early 2000s, these units contributed significantly to national economic development by delivering industry-specific digital solutions. As digital infrastructure expanded, former CIS countries gradually adopted broader IT management frameworks. By the mid-2000s, the increasing demand for structured technological initiatives led to the emergence of IT project management as a distinct discipline essential for supporting economic modernization.

However, the growing demand for modern information technology implementation has faced major obstacles—particularly a shortage of qualified specialists and the absence of national project-management standards during the transition from a centrally planned to a market economy. Additionally, many practitioners lack awareness of sustainable development principles and their relevance to economic transformation.

To achieve its goal of joining the world’s top 30 economies by 2050, Kazakhstan must adopt global best practices, including advanced project management methodologies [66]. Project management (PM) emerged globally with the establishment of PMI in 1969 and the subsequent publication of the PMBOK® Guide [21]. Kazakhstan formalized project management practices through the national standard ST RK ISO 21500-2014; however, the cultural neutrality of this framework limits its contextual adaptation to local realities [67].

PM development in Kazakhstan continues to lag behind that of Western countries due to slow digitalization and persistent legacy governance structures. Although project management was officially recognized in 1993 [68], the current ecosystem—encompassing ministries, universities, and professional associations such as the Union of Project Managers—remains fragmented. Innovation-oriented project management is still underdeveloped, and professional terminology remains inconsistent.

Keeping pace with the rapid transformation of the global economy requires identifying the key success factors for IT project implementation and diagnosing weaknesses in Kazakhstan’s project-management ecosystem.

Project management in Kazakhstan gained renewed momentum after the 2008–2010 financial crisis, but development has remained uneven, hindered by the absence of centralized authority and unified methodology [69]. While international frameworks such as PMBOK and PRINCE2 have been introduced, their practical implementation has been inconsistent. Major national corporations, including KazMunayGas (Astana, Kazakhstan) and Kazatomprom (Astana, Kazakhstan), established project offices with international assistance, yet standardization at the national level progressed slowly until the introduction of ST RK ISO 21500-2014, which still lacks critical components such as business-case development [70].

Persistent challenges include vague feasibility studies, low stakeholder engagement, and frequent project delays—symptoms of broader structural inefficiencies. Government projects, often unique and non-repetitive, make it difficult to standardize methodologies [71]. Furthermore, the consulting market remains small and heavily dependent on public-sector demand.

A turning point came in 2016, when Zerde (Almaty, Kazakhstan) was designated as the lead integrator for public IT projects. The subsequent Digital Kazakhstan program prioritized e-government development, digital literacy, and national technology infrastructure [72]. These initiatives accelerated the adoption of structured project-management approaches, particularly in areas such as risk analysis, governance, and performance evaluation.

Today, Kazakhstan’s project-management ecosystem—shaped by collaboration between foreign experts, domestic professionals, and consulting organizations—is gradually evolving into a formalized, strategically oriented discipline. Continued emphasis on capacity building, contextual adaptation of global standards, and the integration of sustainability principles will be crucial to ensuring effective digital transformation and long-term socio-economic growth.

3.2. Methodology and Sample Description

The literature review enabled the preliminary identification of IT project-management processes and success factors that significantly influence project implementation outcomes. The next research stage aimed to empirically verify these factors through in-depth interviews with experienced IT project managers. This provided initial confirmation of the list of key success factors and their relevance to Kazakhstan’s specific organizational and economic context.

The subsequent stage consisted of a structured survey conducted among professionals with practical experience in IT project management. The survey questions were developed based on insights from the literature review and refined using the findings from the expert interviews.

At the first empirical stage, qualitative in-depth interviews were conducted with five experts representing limited liability partnerships (LLPs) and joint-stock companies (JSCs) from the industrial, governmental, and consulting sectors. The respondents were selected purposefully, based on verified information about their positions and professional roles. All participants were required to have active involvement in enterprise-level project management. The group consisted of two men and three women occupying senior positions (e.g., project managers, department heads), all possessing substantial practical experience in managing IT projects. The interviews were conducted between 2020 and 2021.

A semi-structured interview format was adopted to ensure consistency while allowing flexibility for open discussion [73]. Respondents received open-ended questions in advance to enable thoughtful reflection (see Appendix A). This approach generated experience-based insights into practical challenges and success factors in IT project management. The interviewer remained neutral to minimize bias and encourage candid input. Thematic analysis of the collected responses identified recurring patterns critical to IT project success, enriching the empirical understanding of PM practices within Kazakhstan’s evolving IT ecosystem.

The expert interviews served a dual purpose: (1) to identify and categorize the most relevant success factors in IT project management, and (2) to refine and validate the questionnaire used in the subsequent survey phase.

The scope of the survey research encompassed organizations with established experience in executing IT projects using a project-oriented approach. Most surveyed enterprises described themselves as sufficiently mature to apply formal project-management methodologies in IT implementation. All organizations adhered to the national standard ST RK ISO 21500-2014 [74], while several additionally employed hybrid methodologies that combined international standards such as PRINCE2 (common in quasi-governmental organizations) and Agile frameworks.

To ensure reliability, enterprises and respondents were selected according to three criteria:

- The organization maintains a structural unit (e.g., a project office) responsible for IT project implementation.

- The organization employs certified or experienced project managers within this project office.

- The project office staff have prior experience implementing IT projects using a project-based approach.

In total, 13 enterprises were included in the study. These organizations were chosen based on their active use of project-management practices in developing information systems and on the presence of at least one certified project manager.

This stage employed anonymous paper-based surveys of project managers and IT analysts, focusing on the practical application of PM methods across the IT system lifecycle. Respondents provided qualitative, experience-driven assessments of how different lifecycle stages affect enterprise performance. The survey was conducted between 2020 and 2021.

The questionnaire addressed several thematic areas: domain analysis, team formation, financial planning, communication, the role of PM, monitoring, quality assurance, and project closure. It was divided into two sections:

- Part A: Respondents rated the impact of PM practices on project success using a six-point scale (from “highly positive” to “negative influence” or “no opinion”).

- Part B: Respondents indicated whether specific practices were applied in their enterprises (“yes”, “no”, “don’t know”).

The survey instrument was based on prior academic research and refined following a comprehensive review of international and Kazakhstani literature (Appendix B).

The target population consisted of professionals directly involved in IT project implementation within enterprises that apply structured project-management methodologies. The sample included project managers, IT department heads, business analysts, and project-office staff.

Due to the relatively small number of enterprises with specialized IT project-management departments and certified professionals, the sample size was limited. Out of 40 distributed questionnaires, 30 valid responses were received. Most respondents (74%, n = 22) represented medium-sized enterprises, 23% (n = 7) small businesses, and 4% (n = 1) a large enterprise.

Regarding industry affiliation, 63% (n = 19) of respondents worked in information and communication enterprises, while others represented international consulting firms and private IT companies (10%), human-resource development centers and data centers (7%), and postal-service IT departments (3%).

By role, project managers constituted the largest group (40%), followed by IT managers (27%), department directors (17%), and IT analysts (10%). One head of a project office and one deputy IT director accounted for the remaining 6%. Although no board-level executives participated, all respondents held substantial responsibility for project outcomes and coordination with senior leadership.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of In-Depth Interviews with Experts

The expert interviews revealed a set of key success factors in project management, grounded in practitioners’ professional experience. Providing interview prompts in advance allowed respondents to prepare focused, reflective answers. Although individual perspectives varied, several consistent themes emerged across all interviews.

Clear communication, effective negotiation, and strong team alignment were identified as essential for timely project delivery, while conflict resolution and inclusive dialogue were seen as crucial for minimizing delays. Respondents emphasized the importance of team competence, mentorship for less-experienced members, and proactive management of underperformance.

The use of Project Management Information Systems (PMIS) was unanimously recognized as a major enabler of workflow efficiency, transparency, and coordination. Two respondents also highlighted the need for regulatory adaptability—particularly the ability to adjust project documentation and governance procedures in response to evolving legal requirements.

Taken together, these insights reflect practical strategies employed in Kazakhstan’s public and private sectors for managing IT projects within complex and dynamic environments. The most frequently cited success factors are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key factors of project management according to experts.

4.2. Analysis of the Survey Results

4.2.1. The Quality of Project Management in the Surveyed Enterprises

Respondents identified several IT project-management processes that they considered important yet often missing in their enterprises. Out of 59 analyzed processes, only six were implemented by all 13 surveyed organizations:

- communicating project goals and plans,

- distributing work within the team,

- tracking project progress,

- conducting stakeholder meetings,

- participating in client-requested events, and

- monitoring tasks against the project plan.

Other processes commonly in use included progress reporting (30 responses), business requirements definition (28), project documentation management (29), regular team meetings (30), and collaboration with suppliers (28).

In contrast, some processes were applied infrequently. Preparing the production environment—including downtime budgeting, overtime pay, and managerial supervision—was reported by only five respondents, while environmental and technical requirements were defined in just eight enterprises.

The identified processes correspond to the five Project Management Process Groups defined in the PMBOK® Guide:

- Initiating—defining and authorizing the project;

- Planning—determining scope, strategy, and resource allocation;

- Executing—delivering outputs and achieving objectives;

- Monitoring and Controlling—tracking progress and managing change;

- Closing—formally completing project work and documenting outcomes.

These process groups are interconnected through logical flows in which the outputs of one serve as inputs to another. They operate as functional categories rather than strictly sequential project phases. Table 3 summarizes the extent of process implementation across enterprises by Process Group.

Table 3.

Degree of implementation of project management processes groups in the surveyed enterprises.

The comparative analysis of process implementation across enterprises showed that only one company applied all 59 identified project-management processes. Another implemented 58, two implemented 56, while the remaining nine enterprises reported using fewer than 55 processes, with one organization applying as few as five.

Communication management emerged as a recurring challenge in IT project execution. Respondents were asked to indicate the communication approaches used in their organizations. The most frequently mentioned were:

- interaction with project teams (reported in 9 out of 13 enterprises, 20 mentions),

- stakeholder meetings (conducted in 7 enterprises, 18 mentions).

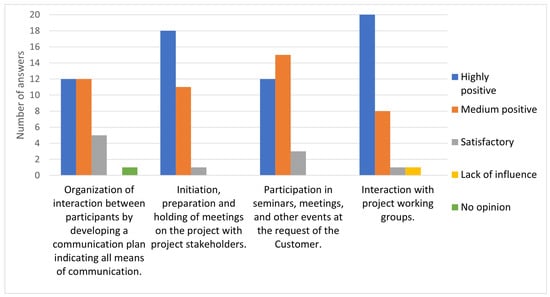

The results on communication practices and their perceived influence on IT project implementation are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Communication management—impact of communication on IT project implementation.

4.2.2. Evaluation of Project Management in the Surveyed Enterprises

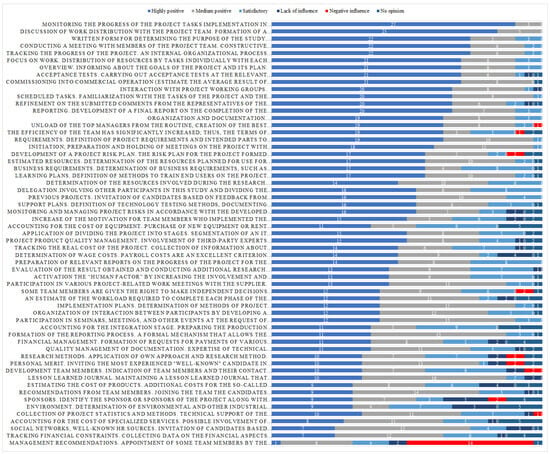

To assess the effectiveness of project-management processes in IT projects, respondents evaluated each of the 59 processes using a six-point scale ranging from “highly positive” to “negative influence” or “no opinion”. The results, summarized in Figure 2 and Table 4, indicate that all processes were perceived positively, albeit with varying degrees of significance.

Figure 2.

Impact of selected project-management processes on the success of IT projects, according to respondents (the full names of the processes are provided in Table 3).

Table 4.

Top-rated project-management processes and their implementation in surveyed enterprises.

The processes most frequently identified as highly influential included:

- Clear documentation of project objectives;

- Informing the team about project goals and plans;

- Team discussions on work distribution;

- Tracking project progress;

- Meetings with stakeholders;

- Participation in client-requested events;

- Monitoring tasks according to the project plan.

At the lower end of the ranking were processes related to:

- Definition of environmental and technical requirements;

- Product quality management;

- Integration-stage planning (e.g., preparation of production environments, downtime budgeting, overtime pay, and managerial supervision).

Despite differences in assessment, no sharp distinction was observed between critical and secondary processes—their perceived value changed gradually. Consequently, all surveyed processes appear to contribute to project success, though the nine highest-rated ones warrant particular managerial attention. To deepen the analysis, we compared these top-rated processes with the number of enterprises implementing them.

Table 4 presents the nine project-management processes that respondents rated as most influential, along with the number of enterprises that applied them. While most top-rated processes were widely adopted, two remained underutilized—tracking task progress against the project plan and team work-allocation discussions—each implemented in only 9 of the 13 enterprises. Given their perceived impact on IT project success, these practices merit prioritization by organizations aiming to improve management performance.

Interestingly, respondents assigned lower importance to processes related to financial control, project budgeting, and detailed monitoring or reporting of project implementation. The findings suggest that practitioners in Kazakhstan place greater emphasis on overall project completion and successful delivery than on strict efficiency and control mechanisms. This contrasts with patterns observed in more economically mature countries, where structured financial governance plays a larger role. The difference likely reflects both the shortage of qualified specialists and limited practical experience in IT project management, as discussed earlier.

4.2.3. The Relationship Between the Declared Rank of Key Project Management Processes and the Degree of Their Implementation

The final stage of the survey-data analysis examined the relationship between the extent to which project-management processes were used in the surveyed enterprises and the perceived overall impact of project-management practices on IT project success.

A total of 59 project-management processes were identified and analyzed in terms of both their frequency of use and their perceived influence as potential key success factors. These processes were grouped according to the five Process Groups defined in the PMBOK® Guide–Sixth Edition [21], which conceptualizes each group as a logical collection of inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs related to project management.

The processes are interrelated through their outputs and may include overlapping activities across different phases of the project lifecycle. The degree of process use was measured by counting how many of the 59 processes were implemented by each enterprise.

In addition to identifying which processes were used, respondents assessed the overall impact of implementing project-management practices in their organizations. The possible responses were:

- highly positive,

- moderately positive,

- satisfactory,

- no influence,

- negative influence,

- no opinion.

Based on 30 completed questionnaires, we calculated, for each enterprise, the total number of implemented processes and conducted Spearman’s rank correlation analysis to examine the association between the degree of process implementation and the perceived effectiveness of project management in IT projects. Table 5 presents the strongest correlations (ρ) identified between the level of process implementation and the overall impact rating.

Table 5.

Spearman’s correlation between selected project-management processes and their actual implementation in IT projects.

The correlation analysis revealed that five process pairs exhibited strong correlations (ρ ≈ 0.80) and seventeen others showed moderately strong relationships (ρ ≈ 0.70), confirming that key project-management practices consistently reinforce project success.

The general finding from this analysis is that information sharing, direct communication, and collaboration among managers, project teams, and other stakeholders at all stages of implementation are fundamental to IT project success. The evidence underscores that communication and cooperation among all participants form the foundation of successful project delivery.

Further analysis showed a particularly high impact of processes related to project evaluation and follow-up research, which correlated strongly with team-selection mechanisms and requirements definition—elements crucial at the early stages of project maturity [21]. Clearly defined team roles were linked to accurate cost estimation and sponsor identification, suggesting that strong coordination supports both financial and strategic alignment.

Motivation also emerged as a central factor, interconnecting with individual research, resource planning, environmental requirements, and implementation strategies. Evaluation and communication—especially post-project review and delegated decision-making—were identified as key components of iterative learning and improvement.

In total, 148 pairwise associations (ρ ≥ 0.50) were recorded, demonstrating the highly interconnected nature of effective project management. Success does not depend on isolated activities but on their synergistic interaction—particularly across domains such as finance, human resources, motivation, communication, and strategic oversight.

Respondents also highlighted several important project-management processes that are currently not implemented in their enterprises, despite being rated as highly beneficial. These are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Processes considered important in project management but not implemented in the surveyed enterprises.

The main conclusion from analyzing the relationship between the declared importance of project-management processes and their actual implementation is that a substantial gap exists between stated priorities and practical application. Although managers and specialists acknowledge the significance of individual success factors, their implementation within enterprises remains limited due to insufficient experience in executing IT projects.

Based on this analysis, processes not yet implemented but rated highly by respondents should be prioritized for future adoption, particularly in IT project management. Spearman’s rank correlations for team-related processes indicated moderate yet statistically significant positive associations (p < 0.05).

Table 7 shows detailed results for correlations between team-related success factors and process implementation.

Table 7.

Spearman’s correlations between team-related success factors and process implementation impact.

A clear, though modest, association was observed between declared and implemented team-formation factors—especially those drawing on prior project experience and managerial or peer recommendations. These findings suggest that IT project-management specialists in Kazakhstan recognize the importance of such success factors, yet face practical challenges in applying them consistently.

The gap between awareness and implementation likely stems from limited project-management maturity, insufficient experience, and constrained institutional capacity within enterprises. Addressing these barriers through systematic training, certification, and the contextual adaptation of global standards will be essential for improving IT project success in Kazakhstan.

5. Discussion

To test the hypotheses proposed at the outset, we applied three complementary research methods: a review of academic literature (Kazakhstani and international), in-depth interviews with senior managers experienced in IT project implementation, and an anonymous survey of practitioners actively involved in IT projects. This mixed-method approach enabled triangulation of results and strengthened the validity of the findings.

Hypothesis 1 was confirmed by evidence that 59 project-management processes were identified as core to effective IT project implementation—ten more than the 49 processes defined in the PMBOK® Guide–Sixth Edition. These processes, grouped by logical function, were recognized as essential throughout the entire project life cycle. Insights from top managers further underscored the importance of several specific processes—communication, motivation, delegation, risk management, and change control—as key success factors in their professional practice.

Hypothesis 2, which focused on the role of the project team, also received strong support. Both the literature and the expert interviews emphasized team competence, cohesion, and interdisciplinary collaboration as prerequisites for project success. The interviews confirmed that careful team selection, motivation, and healthy internal dynamics significantly influence outcomes. Statistical analysis revealed modest but clear positive correlations between team-related management processes and project results, reinforcing the conclusion that the project team is a major success factor in IT projects.

Hypothesis 3 addressed the influence of professional process application and effective communication. Both theoretical sources and interview data identified communication as a critical component of project success. Senior managers highlighted the value of face-to-face interactions, constructive discussions, team cohesion, and shared decision-making. However, the quantitative results revealed only weak correlations for communication-related processes, suggesting that further research is required to examine their measurable impact. The collected data also exposed weaknesses in the implementation of professional project-management standards—particularly in planning, budgeting, and control.

Overall, the findings drawn from literature analysis, expert interviews, and survey data provide strong confirmation of Hypotheses 1 and 2 and moderate support for Hypothesis 3.

The results for Hypotheses 1 and 2 indicate that the success factors for IT project management in Kazakhstan broadly correspond to those observed in developed economies [21,22,23]. The main difference concerns Hypothesis 3: limited national experience and a shortage of certified professionals increase the importance of the ability to apply project-management standards effectively, particularly in controlling the use of financial and human resources.

The results further demonstrate that an orientation toward project completion and success outweighs the emphasis on efficiency and resource optimization. The implementation of IT projects in Kazakhstan is primarily viewed as a vehicle for achieving digital transformation and accelerating the development of an innovation-driven economy that fosters long-term socio-economic sustainability. By contrast, the literature highlights the critical role of governance and monitoring in project management (planning, scheduling, control, and feedback), with control and monitoring often identified as key components alongside goal achievement, executive sponsorship, and communication [16,75].

Improvements in the efficiency of IT project management can be expected as project teams gain experience and the economy develops. Hence the prominent role in our study of the human factor, communication, and collaboration—capabilities that are essential while building nationwide, practical experience in IT project management.

This study advances the literature on IT project management success factors by providing a context-sensitive ranking of 59 processes across the full life cycle, and identifying a distinctive pattern for an emerging, innovation-oriented economy: human-centric drivers (communication, team composition, collaboration, motivation) carry greater leverage for success than formal controlling and detailed financial governance. While mainstream research usually treats “people factors” and governance/monitoring as co-equal pillars, our results show a shifted balance at earlier maturity stages, thereby refining contingency views of project success. In particular, we document a systematic gap between what respondents declare as important and what is actually implemented—most notably for integration-stage budgeting, external quality assurance, and lessons-learned practices—and show how this gap mediates the impact of process maturity on outcomes.

We also extend theoretical understanding at the intersection of innovation and sustainability. By linking success factors to capability building, we show that “soft” competencies (team and stakeholder engagement, knowledge sharing, role clarity) enable organizations to absorb and routinize “hard” governance practices over time, creating a pathway from ad hoc delivery to repeatable, resource-efficient execution. In an economy pursuing digital transformation, such people-centric capabilities are not merely ancillary: they are prerequisites for later gains in eco-efficiency (resource accounting, integration-stage planning) and organizational resilience (risk management, post-project learning).

Relative to prior studies focused on mature settings, our evidence from Kazakhstan clarifies boundary conditions: when national and organizational PM maturity is low, success hinges on coordination, motivation, and sponsor–team dialogue, whereas formal financial and control mechanisms are underused despite being perceived as valuable.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this research was to identify the key success factors for the sustainable implementation of IT projects. Through an extensive literature review, 59 project-management processes were identified and categorized into five Process Groups: Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing. Overall, these processes were associated with positive project outcomes and appear to contribute to effective project management.

The highest-rated factors include communication, pre-project analysis, planning, continuous stakeholder engagement, project control, change management, domain expertise, risk management, delegation, and the delivery of planned outcomes. Taken together, these top factors underscore the importance of inclusive engagement of team members and stakeholders throughout the entire project lifecycle.

Our results indicate that IT project-management success factors are context-dependent: in economies at earlier stages of project-management maturity, human factors—such as teamwork and collaboration—have a greater impact, whereas formal controlling mechanisms tend to be relatively less decisive.

The identified success factors in IT project management not only enhance organizational efficiency but also contribute directly to sustainable development. Clear communication, stakeholder engagement, and continuous knowledge sharing foster transparency and long-term trust, which are essential for socially responsible project execution. Similarly, effective risk management, team competence, and motivation promote resilience and adaptability—key qualities for enterprises operating in dynamic and resource-constrained environments. By embedding these practices, IT project management supports not only the achievement of immediate business objectives but also the broader goals of innovation-driven and sustainable economic growth. However, a clear challenge remains: the limited focus on efficient resource utilization during project execution, an issue that must be addressed as IT project-management practice continues to develop in the Kazakhstani economy under study.

It is recommended that future research compare enterprises that apply the project-based approach with those that do not—starting with financial metrics—to evaluate its broader organizational impact. However, limited data availability from Kazakhstani enterprises remains a significant challenge. Attention should also be paid to processes recognized as important by survey respondents but not yet implemented in practice, as these may play a critical role in future project success. Our study reveals a substantial gap between the project success factors declared as important and those actually implemented in IT project-management practice.

Another limitation of this research is that it focuses on factors associated with internal project success, rather than directly evaluating projects’ contributions to broader social, environmental, or long-term economic sustainability. Understanding how the maturity of IT project-management practices in enterprises influences socio-economic and environmental development will require additional longitudinal research over the coming years.

The results of this study yield several practical implications and recommendations. First, organizations should stabilize collaboration and information flow by institutionalizing brief goal and plan updates, establishing regular stakeholder touchpoints, clarifying roles and handoffs, and adopting a lightweight communication plan that ensures visibility of progress. Second, they should introduce minimum viable governance—pilot basic integration-stage budgeting and cost tracking, add simple acceptance gates, and maintain a concise lessons-learned log after each iteration. Third, to scale sustainably, organizations should implement a Project Management Information System (PMIS) for unified reporting and risk oversight, align training with rollout to accelerate adoption, and embed environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and resource-efficiency requirements directly into project plans.

In closing, project management in IT remains a developing area within Kazakhstan’s digital transformation. As the country moves toward an innovation-driven and sustainable economy, greater knowledge and application of modern project-management methods are essential, warranting continued research and practical guidance. The findings presented here may also be relevant for other countries pursuing sustainable digital transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.; methodology, S.A. and A.P.; formal analysis, S.A. and A.P.; investigation, S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P.; supervision, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded under subvention funds for the Faculty of Management and by- program “Excellence Initiative—Research University” for the AGH University of Krakow.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

In-depth interview with top IT managers

Competence

- How experienced are you as a Project Manager? (number of years)

- Do you have a project management qualification, certification, or membership?

- What is the most desired skill that is required to become a successful project manager according to your experience? Please give a couple of examples regarding your past projects.

Experience

- 4.

- How mature do you think your organization is in terms of project management?

- 5.

- What’s your preferred project management methodology?

- 6.

- What project management software (tools) do you prefer?

- 7.

- Which specific products do you currently use?

- 8.

- What methods would help you deliver projects better?

- 9.

- Did you have a difficult project in your experience? What was this complex project about, and how did you manage to implement it?

- 10.

- What are the greatest challenges in delivering projects?

- 11.

- How do you deal when you’re overwhelmed or underperforming?

Remote work experience

- 12.

- Have you managed remote teams and outsourced resources?

- 13.

- Work from home has become the new reality in the post-COVID-19 world. How well are you prepared to manage a remote team?

- 14.

- What difficulties did you encounter while working remotely? (team, Internet, communication)

- 15.

- Do you think that remote project management work can be as effective as office (traditional) work?

Clear Communication

- 16.

- What is your communication style with your team?

- 17.

- What were the communication challenges during your projects?

- 18.

- How do you manage team members who are not working to their full potential?

- 19.

- What is your strategy for working with an underperforming team member?

Consistency and Integrity

- 20.

- Do you report “bad” news? If yes, how do you report bad news?

- 21.

- How have you handled disgruntled employees?

- 22.

- What are some examples of times you’ve kept your promise even when that might have been difficult?

Customer Orientation

- 23.

- How do you ensure you and your team deliver or exceed customer expectations?

- 24.

- Suppose the project has gone off the rails. What steps would you take to get it back on track?

- 25.

- Suppose the customer is not happy about the quality of the project outcomes. How do you handle the situation? What is your way of handling an unhappy stakeholder?

Focus on results

- 26.

- How do you go about managing the performance of your team?

- 27.

- How do you motivate team members?

- 28.

- What are some of the tools and resources you’ve used to develop your team?

Effective Delegation

- 29.

- Do you delegate?

- 30.

- How easily do you delegate responsibility?

- 31.

- How do you monitor and review the delegated responsibilities?

Goal Focus

- 32.

- How do you set goals for your team? How do you track these goals?

- 33.

- What are the techniques you may use to define the scope of a project?

- 34.

- Describe the team forming process you follow in project management.

- 35.

- What general metrics do you use to determine if a project is progressing on track?

Managing Ambiguity and Risks

- 36.

- Describe two areas in your current project, where there is a high level of uncertainty. How do you tackle these uncertainties?

- 37.

- How do you control changes to your project?

- 38.

- Do you seek help outside of the project team?

- 39.

- What approach do you take when a project hits a roadblock and does not go according to plan, despite the team’s best efforts?

Prioritizing and Time Management

- 40.

- How do you ensure that your project is always on track?

- 41.

- What tools do you use as a manager to plan your activities as well as that of your team?

- 42.

- How do you help the team prioritize competing or simultaneously urgent tasks?

- 43.

- How do you prioritize tasks on a project?

- 44.

- What is your strategy for prioritizing the tasks?

Proactive Decision Making

- 45.

- Give a few examples of proactive decision-making in your past projects

- 46.

- Can you give a few examples of a time when you made a tough decision, and it backfired?

Conflicts

- 47.

- What is your strategy to deal with internal conflicts among the team members?

- 48.

- Do conflicts affect the overall project outcome?

- 49.

- How do you gain agreement with teams?

Appendix B

Survey of respondents from the IT field

The survey questionnaire was divided vertically into two parts.

Part “A”. What impact on the success and degree of implementation of an IT project has a phased study of the subject area? Possible answers: Highly, positive, Moderately positive, Satisfactory, Lack of influence, Negative influence, No opinion.

Part “B”. Are similar research stages used at your enterprise? Possible answers: Yes, No, Do not know.

QUESTIONS

Basic principles of conducting a domain survey before implementing an IT project. Based on your own experience, evaluate the impact of the following research that affects the implementation of the IT project (part “a”). In addition, for each step of the IT project research, indicate whether the research is generally used at your enterprise (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Written form for determining the purpose of the study.

Documentation of the goals set allows to accurately focus on a certain range of the studied area, which will allow to successfully carry out the work.

- 2.

- Determination of the resources involved during the research.Maintaining a list of viewed publications. Information sources include the following:

- -

- previous experience;

- -

- the experience of other people;

- -

- proven and high-quality Internet sites;

- -

- specialized magazines;

- -

- professional literature on relevant topics.

- 3.

- Delegation.

Involving other participants in this study and dividing the study area into sectors with assigning them to each participant from the team.

- 4.

- Research methods.

Application of own approach and research method.

- 5.

- Organization and documentation.

Collection of joint information accumulated personally and by members of the project team.

- 6.

- Evaluation of the result obtained and conducting additional research.

Checking the jointly collected information on the subject area of the project being implemented. In case of missing information, continuation of the study at an unscheduled date.

The relationship of the project manager with the management and the project team. Based on your own experience, evaluate the effectiveness of tasks when using the function of delegating responsibilities and tasks on the project (part “a”). In addition, for each of the presented characteristics of delegation, is it used at your enterprise in the implementation of IT projects (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Unload of the top managers from the routine, creation of the best conditions for solving strategic management tasks.

- Activation the “human factor” by increasing the involvement and interest of the project team.

- Some team members are given the right to make independent decisions that were effectively reflected in the result of the project.

- The efficiency of the team has significantly increased; thus, the terms of the project were met on time for the Customer.

- Increase in the motivation for team members who implemented the project and were able to reveal new professional qualities of team members.

The stages of the design of the financial part used for the implementation of the IT project. Based on your own experience, evaluate the stages of project budgeting of an IT project as part of its design (part “a”). In addition, is there a specific methodology for calculating the budget for each IT project at your enterprise (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Application of dividing the project into stages. Segmentation of an IT project into its component parts, which makes it easier to determine characteristic points and estimate the amount of work at each stage.

- Accounting for the integration stage. Preparing the production environment for the implementation of the project requires budgeting for system shutdown times, delays, overtime payment and time required for the project manager to supervise the work carried out on schedule.

- An estimate of the workload required to complete each phase of the project. Tariff rates for time tracking of each team member are planned at each stage of the project.

- Accounting for the cost of specialized services. Possible involvement of consulting or subcontracting team members.

- Accounting for the cost of equipment. Purchase of new equipment or rent of host premises and servers for the deployment of an IT project.

- Estimating the cost of products. Additional costs for the so-called “office work” that are required at all stages of the IT project.

- Development of a project risk plan. The risk plan for the project formed during the study.

Formation of an IT project development team. Based on your own experience, evaluate the criteria for selecting candidates for the IT project development team (part “a”). In addition, is there a certain criterion for selecting an IT team for the successful implementation of an IT project (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Previous projects. Invitation of candidates based on feedback from colleagues from previous projects. Selection of candidates based on the opinion of colleagues.

- Personal merit. Inviting the most experienced “well-known” candidate in the field of IT to give a future project a certain status or fame.

- Management recommendations. Appointment of some team members by the management despite some lack of competence of these candidates in the part of the project that is planned in the future.

- Recommendations from team members. Joining the team the candidates invited by the team members, who recommended them.

- Social networks, well-known HR sources. Invitation of candidates based on submitted CVs from Internet sources. Based on the results of the interview, a general project team is formed.

Formation of an IT project plan. Based on your own experience, evaluate the main stages of the IT project plan that was implemented at your enterprise (part “a”). In addition, does the project plan apply at all at your enterprise (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Overview. Informing about the goals of the project and its plan.

- Sponsors. Identify the sponsor or sponsors of the project along with their contact information.

- Development team members. Indication of team members and their contact information.

- Requirements. Definition of project requirements and intended parts to be supplied.

- Scheduled tasks. Familiarization with the tasks of the project and the work division scheme. May contain a chart.

- Estimated resources. Determination of the resources planned for use for the implementation of the project. Resources include users, equipment and services.

- Environment. Determination of environmental and other industrial requirements for the project plan.

- Business requirements. Determination of business requirements, such as accounted business cycles, anticipated project deliverables, and meeting schedule.

- Implementation plans. Determination of methods of project implementation to the state of industrial use.

- Support plans. Definition of technology testing methods, documenting methods, and support methods by own- or third-party companies.

- Learning plans. Definition of methods to train end users on the project supplied parts.

Implementation of the IT project plan. Based on your own experience, evaluate the application of the presented approaches in the implementation of the project plan (part “a”). In addition, is the plan for the implementation of the project applied at your enterprise (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Discussion of work distribution with the project team. Formation of a responsible team, whose members build trusting relationships with each other. Regular general meeting defined by formal regulations, as well as the use of informal types of communication with the team.

- Focus on work. Distribution of resources by tasks individually with each member of the project team.

- Conducting a meeting with members of the project team. Constructive meeting on project tasks with the ability to present reports from each member of the project team on the work performed.

- Tracking the progress of the project. An internal organizational process for team reporting on completed tasks, which reflects the progress of the project and allows to analyze the amount of work done, the budget and the time remaining until the completion of the project.

- Formation of the reporting process. A formal mechanism that allows the team to regularly report to the manager on the progress of the project schedule.

- Collection of project statistics and methods. Technical support of the process of collecting data on the spent working time and the percentage of tasks completed. The methods can be different, for example, e-mail, spreadsheets, web application (form), Microsoft project, Microsoft Project Central, etc.

- Tracking financial constraints. Collecting data on the financial aspects of the project by the project manager for the project sponsor.

- Financial management. Formation of requests for payments of various nature related to the project, purchase orders, payments, invoices, etc.

- Tracking the real cost of the project. Collection of information about payment of invoices to vendors and consultants, as well as the time spent by team members on tasks already completed.

- Determination of wage costs. Payroll costs are an excellent criterion for constantly checking the completion of a project against the budget cost of the project.

Communications management. Based on your own experience, evaluate the impact of communication on the implementation of the project (part “a”). In addition, whether certain characteristics of communication management are applied to the implementation of the project at your enterprise (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Organization of interaction between participants by developing a communication plan indicating all means of communication.

- Initiation, preparation and holding of meetings on the project with project stakeholders.

- Participation in seminars, meetings, and other events at the request of the Customer.

- Interaction with project working groups.

Implementation and control of the project. Based on your own experience, evaluate the management of project implementation according to the presented criteria, as well as tracking project risks (part “a”). In addition, is the monitoring of project implementation and risks applied at your enterprise (part “b”). Please fill out both parts of the survey (part “a”, “b”).

- Monitoring the progress of the project tasks implementation in accordance with the project work plan.

- Participation in various project-related work meetings with the Supplier.

- Preparation of relevant reports on the progress of the project for the Sponsor and the Customer of the project.