Abstract

Developing tools to assess university lecturers on the quality of their teaching practice is a priority for achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4. The aim of this research is therefore to propose a typology of teaching profiles and analyse the factors that influence each of them, with a view to proposing a model for identifying lecturers who need support. Based on 10,938 observations made between August 2021 and June 2025, a heuristic method was used to classify all observations into six quadrants according to student academic performance and student evaluations of their teachers. Based on the classification of all observations into six quadrants, called teacher profiles, logistic regressions were performed in Gretl software version 2024c to identify which characteristics inherent to the teacher, the educational context, and the curricular stage explain the classification of the teacher into a particular profile. The results indicate that full-time teachers and those with higher academic qualifications tend to obtain higher scores on the SET, while online or hybrid modalities are associated with lower scores on the SET. In addition, the six teaching profiles obtained an accuracy of over 80% in the logit models, highlighting significant effects of age, modality, and curricular level (p < 0.05) on the probability of belonging to each quadrant. It is concluded that factors related to curricular advancement, the educational context, and those inherent to the teacher can explain the proposed typology. This typology could serve as a management tool to identify teachers who need specific support to move towards profiles that are ideal for the university institution. Among the main limitations of this study are the heuristic methodology and the fact that the data were obtained from a single educational institution.

1. Introduction

The quality of university education is a strategic priority for educational institutions worldwide [1], encompassing a wide range of practices and considerations that reflect cultural and social influences on higher education systems [2,3]. Quality assessments and reward mechanisms present challenges and opportunities that invite us to better understand teacher profiles in order to design institutional policies and teacher development strategies that promote educational quality and continuous improvement in teaching [4,5,6].

In recent decades, research has been conducted on teacher profiles and their influence on educational quality, whether in terms of educators’ conceptions and effectiveness [7]; the personality, beliefs, self-concepts, and motivation of teachers [8]; and their teaching skills [9]. It has been identified that, in the university context, teacher profiles influence fundamental elements of quality, such as student retention [10], academic performance, and student motivation [11].

Despite extensive research on teacher profiles, there is a knowledge gap in the university setting regarding quantitative models that simultaneously integrate inherent teacher factors, the educational context, and curriculum progress [12] with objective performance metrics [7,13], such as student evaluations of teachers (SET) and group average grades [14]. Most studies have focused on preschool, primary, and secondary education levels [4,15,16] or have prioritised qualitative approaches from only one faculty or field of knowledge [12,17].

For this reason, the aim of this research is to propose a typology of teaching profiles and to conduct a comprehensive, simultaneous and objective analysis of the factors that influence each of them, regardless of the teacher’s area of specialisation and the faculty in which the classes are taught, with the aim of designing an analytical and quantitative model that allows for the identification of teachers who require support in the development of teacher development strategies.

To this end, using the logit model—as a binary model of qualitative dependent variable [18]—and descriptive statistics with a longitudinal approach involving data obtained over four years, the variables that predict the probability of a teacher belonging to one of the profiles proposed in the classification [19] are identified in order to identify consistent trends in the data obtained.

The main contribution of this work is to propose a quantitative typology of teaching profiles based on empirical evidence, which allows us to describe how factors inherent to the teacher, the educational context and curricular advancement relate to academic performance and student evaluations of teaching. In turn, this model can provide a framework for institutional decision-making and is intended to serve as a diagnostic tool to support the design of teacher development strategies, as it is possible to identify profiles that require support. This typology is applicable across the board, regardless of the teacher’s area of specialisation and the faculty in which the classes are taught.

1.1. Educational Quality in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

Educational quality is a strategic and unavoidable necessity in light of global impacts and international commitments under the United Nations 2030 Agenda, which aims to provide equal access to vocational training, promote gender equality, alleviate poverty, and foster universal access to quality higher education [1]. Against this backdrop, higher education institutions play a fundamental role in achieving the objectives set out, as well as in promoting sustainability as a fundamental axis for ensuring quality education that responds to contemporary challenges [20].

In the university setting, the discussion regarding educational quality focuses on the disjunctive question of quality of what, quality for what, and quality for whom, since it is a relative and contextual construct [14]. From a contemporary and global perspective, UNESCO conceives it as a multidimensional concept, that is, the ability to achieve positive results in student learning and personal and professional development, as well as to meet the expectations and needs of society. This implies the dynamic integration of institutional management, curriculum programmes, and university teaching to create inclusive, equitable, relevant, and sustainable environments [1].

Ghamrawi et al. [21] see it as a driver for development due to the positive correlation between a country’s level of development and the quality of its education system, given its potential to empower students and lift them out of poverty.

For the purposes of this study, educational quality in HEIs is understood as the ability to effectively manage their resources and processes to achieve academic excellence while ensuring social relevance and comprehensive training towards balancing economic needs and humanistic essence in light of the demands of society.

1.2. University Education as an Element of Educational Quality

University teaching reflects cultural and social influences from higher education systems [2]. Authors such as Ali et al. [22] argue that university teaching involves much more than what happens in the classroom or in online classes, highlighting the importance of contextual compatibility. While it reflects academic commitment, professional identity, and teacher leadership as fundamental elements in promoting better teaching practices [22], there are conflicting positions with some ambiguities that should be considered.

For example, according to Kelly et al. [23] in the field of university teaching, teachers deliberately prioritise certain behaviours according to their beliefs about their role, with their age predisposing their self-perception in teaching. Romero Cruz [24], meanwhile, identifies that virtual teaching has a positive impact on academic performance, with variations depending on the gender of the teacher. However, Weinert et al. [25] argue that there is no successful pattern for the teaching role, especially since individual strengths and weaknesses influence the way teachers teach and the quality of their practice [26].

It is a fact that university teaching is based on models that provide objective guidelines for the university and its teaching staff to evaluate and improve their teaching [27], as it influences multiple factors that shape pedagogical processes, institutional policies and structures, as well as elements more closely related to the teacher and their teaching style, since teachers teach not only what they know but also what they are [28], which influences effective teaching [29].

For the purposes of this study, we will focus on the following factors: 1. The inherent characteristics of the teacher, which include traits such as age, gender, academic degree, and type of contract; 2. The educational context, which encompasses the teaching modality, whether face-to-face, hybrid, or online, as well as the language of instruction (Spanish, born of the context of the study, or English); and 3. Curricular progress, which refers to the stage of the curriculum at which the subject is taught, understood as the student’s proximity to professional practice, and is generally divided into blocks, either basic level (at the beginning of university studies), intermediate level (mid-career) and professionalising level (in the final semesters of university).

Since it is necessary to develop transformative models from a holistic perspective that guide the drive towards quality in university education with a view to proposing solutions to the challenges posed, this requires the professionalisation of the teaching profession with a view to ensuring the sustainability of quality in university education [20].

1.3. Teacher Profiles, an Empirical Perspective as an Element of Educational Quality

The development of teaching profiles is a critical area in educational research, as they reflect the way university teaching is carried out, as well as its educational quality.

For the purposes of this study, we conceive of teaching profiles as consistent patterns inherent to the teacher, the educational context, and progress in the curriculum that are reflected in the educational practice of different teachers [30], or distinctive aspects of a teacher that remain constant from one situation to another, regardless of the content being taught [12].

Some empirical studies address teacher typology from different perspectives, educational levels, and contexts, with both similarities and differences in their results and positions. For example, Sinakou et al. (2024) [16] examined the teaching profiles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in primary and secondary schools in Belgium, based on factors such as their pedagogical beliefs, interests and teaching practices, identifying two main profiles: teachers with a low and a high orientation towards ESD practices. In both profiles, inconsistencies between factors related to pedagogical beliefs and practices stand out.

For their part, Holzberger [30] conducted their study in secondary schools in Germany, identifying teacher profiles according to teaching quality and its relationship with student development in terms of performance and enjoyment of mathematics. They highlighted that students taught by high-quality teachers tended to receive higher grades, with better academic performance and enjoyment of classes. They noted age as an influential factor, with younger teachers showing greater enthusiasm for teaching and students achieving higher academic performance.

In another sense, Gleisner Villasmil et al. [15] explored the differences between teacher profiles with demographic aspects regarding the use of digital learning resources (DLR) in secondary school teachers in Sweden. They identified five teacher profiles ranging from high to low DLR capacity. Their results differ significantly in terms of demographic factors, the teacher’s academic degree and age, as do the studies by Salas-Rodríguez et al. 2025 [31], who found no predictors in demographic factors, subject taught, academic degree and years of teaching experience.

This study analyses university teaching profiles, avoiding the examination of isolated variables with the aim of identifying subpopulations of teachers with similar patterns. It considers all subjects taught in different faculties, as well as trends in these subjects, using logit models and descriptive statistics.

1.4. Research Questions

This study aims to make a scientific contribution by proposing and justifying a typology for the classification of university teachers into six profiles, then indicating the factors that consistently influence each identified profile over time. Therefore, the main research questions are as follows: What teaching profiles can be identified in the context of university teaching, in terms of students’ academic performance and the SET? How do factors inherent to the professor, the educational context, and progress in the curriculum influence the identified teaching profiles? How can a typology of teaching profiles support quality improvement in the context of university teaching?

2. Research Design and Context

2.1. Study Design

This study was conducted using a quantitative methodology covering a longitudinal time frame. Each observation unit was a class taught by a teacher in a specific semester, and the database was formed from observations of classes taught between August 2021 and June 2025. The dependent variable was the binary variable that allowed a class to be classified as belonging or not to a specific quadrant of the teaching profiles proposed by this study. The independent variables used were: the average academic performance of the students, the student evaluations of teachers, the teacher’s highest level of education, the number of students enrolled in the class, the level to which the subject belongs (basic, intermediate, professional, or elective), the teacher’s contract (full-time or part-time), the language in which the subject was taught (Spanish or English), the format of the subject (face-to-face, online, or hybrid), the teacher’s age, and the teacher’s gender (female or male).

2.2. Data Collection and Sampling

The data collected for this study consists of 10,938 observations, with each observation being associated with a class taught by a specific teacher. Of the total number of classes analyzed, 36% were taught by women and the average age of the teachers was 48.6 years. While 10.8% of the subjects were taught in English as a foreign language, the rest were taught in the teachers’ mother tongue, which is Spanish. Thirty-six percent of the teachers had doctoral degrees. The average grade of the students in all the classes observed was 8.32 on a scale of 0 to 10, and the teachers had an average rating from their students of 9.49 on a scale of 1 to 10.

Regarding inclusion criteria, all classes taught by teachers between August 2021 and June 2025 were used. Observations by full-time and part-time teachers were considered. Regarding exclusion criteria, observation units that did not have complete information on their dependent and independent variables, SET, or final grade were not considered in the analysis.

Regarding the instruments used, specifically for the SET, an institutional questionnaire based on a scale of 1–10 was implemented, with 11 items grouped into the dimensions of teaching practice, course organisation, course evaluation and teaching attitudes. The reliability of this instrument had previously been argued by Ref. [14].

2.3. Algorithm for Classifying Each Class into a Teaching Profile

The first step in developing this typology was to classify the set of observations, each consisting of a class taught by a university teacher in a specific semester and at a particular school or faculty. It is important to note that this classification algorithm is heuristic. It follows a set of practical rules that were developed with the support of the university’s deans, whose institutional experience guided the definition of the ideal profile and the decision thresholds. In the second step, logit models were developed for each teaching profile, allowing for validation of whether different variables could predict that a teacher belonged to a specific classification. Subsequently, conclusions were drawn regarding the variables that accurately predict the probability of a teacher belonging to a certain teaching profile. Finally, the upper center teaching profile was proposed with the objective of quality improvement in university teaching; in particular,, the classification is based on the academic performance of the group (reflecting both the demands of the teacher and assimilation by the student), for which an intermediate value is sought, and the student evaluation of teaching (SET), for which a high value is desirable. In other words, this model can support institutional decisions and educational policies in a way that promotes quality in university education, encouraging professors to migrate from any profile to the upper center. It should be noted that the proposed algorithm can adapt to new observations (understood as a professor’s class in a specific group) and iteratively concentrates less than 80% of the faculty in the upper center quadrant, which could thus facilitate a process of continuous improvement. Although different thresholds could be used, the 80% rule was selected based on institutional practice and expert judgment. Given the exploratory nature of the study, a sensitivity analysis of alternative thresholds was not performed, which represents a limitation.

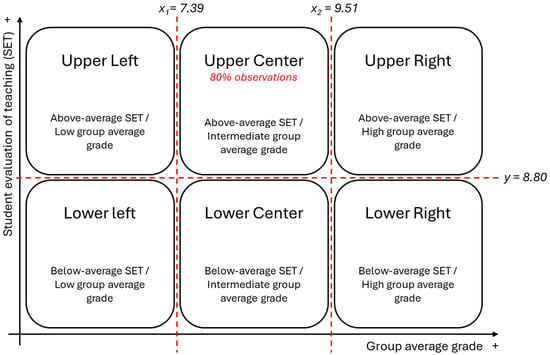

The algorithm is intended to serve as a classification procedure that indicates certain defined steps and offers decision criteria that facilitate its replicability. Thus, the first step consists of constructing a scatter plot based on two variables of interest: the group’s average grade, represented on the horizontal axis, and the student evaluations of teachers, located on the vertical axis. In this way, each class is visualized as a point. Considering all the observations together makes it possible to identify trends, detect outliers, and generate a comparative framework of teaching performance for each school or faculty (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the six teaching profile quadrants.

Once the diagram has been drawn up, all observations are classified into six quadrants, with 80% of classes concentrated in the upper central quadrant. Among the multiple solutions that meet this criterion, the one that represents the smallest area but contains 80% of the observations is selected. The reason for classifying all observations into six quadrants is that the upper central quadrant is considered the ideal profile. In this upper central quadrant, a teacher is well regarded by their students but, at the same time, the grades they give their students are not extreme. Therefore, if 80% of the observations are concentrated in this quadrant, the objective is to analyze the other five quadrants to identify the factors that may define them and how they can be addressed to help teachers move toward the upper central profile, thus facilitating continuous improvement in teaching quality.

To obtain the various solutions, the upper and lower limits of both axes are gradually adjusted until the box containing the required percentage is found, while groups with unusually high academic averages (above 1.5 standard deviations from the mean)—which are thus considered unrepresentative—are excluded from the right quadrants. Once this central box has been defined, its limits are used to divide the graph into six quadrants that distinguish different combinations of academic performance and student evaluations of teachers, which facilitates the detection of general patterns as well as notable or problematic cases that deserve special attention. With respect to the data collected for this study, the resulting limits were x1 = 7.39, x2 = 9.51, and y = 8.80 w.

The 80% was used as a threshold because it helps to identify a broad and representative group of classes with a balanced combination of academic performance and SET scores. This value helps to define a high-performance zone without being too strict or excluding most teachers. It also supports a process of continuous improvement, because teachers who are not inside the 80% of the UPPER-CENTER quadrant can work on specific actions to move closer to this ideal profile. As more teachers remain close to the central area, those who appear at the extremes receive a clearer signal that they may need additional support or professional development. Percentile-based criteria are common in educational analysis because they offer a simple and practical way to classify results and compare them with institutional expectations. For this reason, the 80% threshold was considered a reasonable reference to define the ideal quadrant.

It is also important to justify that values greater than 1.5 standard deviations from the mean were excluded from the CENTER quadrants to form the RIGHT quadrants, as these were perceived as statistical outliers that could distort the limits used to form the quadrant representing the UPPER CENTER. The use of 1.5 SD as a criterion is common in simple methods for detecting outliers and, in this study, helped to keep the classification more stable and realistic. On the other hand, the UPPER CENTER sought a teaching profile that had a balance between demands and teaching, so that students’ grades could not be at the low or high ends of the scale.

2.4. Data Analysis

To explain the factors that influence whether a teacher belongs to one quadrant or another, six logistic regression models were constructed (one per quadrant). The variable to be explained is the prior classification of a university teacher as belonging to a specific quadrant, with a binary value of 1 if they belong to the profile and 0 if they do not correspond to that profile. Given these characteristics of the data, it was decided to use a logit model, as a binary qualitative dependent variable model [18], with the objective of identifying the probability that a university professor with certain characteristics belongs to a given profile in the proposed typology based on the variables that positively or negatively influence each of the factors describing the profile.

All categorical variables were coded using dummy variables. For each group of categories, one was selected as a reference to facilitate interpretation. Age was grouped into ranges of 10 years, as usual, to identify any possible influence of each age block on the dependent variable. The dependent variable in each model was binary, coded as 1 when the class belonged to the corresponding quadrant and 0 otherwise. SET scores and group academic averages were used as continuous variables on their original scales.

Continuous variables were not standardised because their original scales are easy to interpret for academic decision-making. Since the logit model does not require standardisation and the variables share similar numerical ranges, maintaining the original units allowed for a more direct understanding of the coefficients.

Furthermore, no formal sensitivity tests were performed in this study, as the main objective was to describe the general patterns of teaching profiles using the available institutional data. The classification procedure and logit models were applied consistently across all observations, and the results remained stable when reviewed internally during the analysis process. Given that the study is exploratory in nature and works with a large data set spanning several semesters, we considered that it was not essential to perform additional sensitivity checks for the conclusions presented.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study used anonymised administrative data provided by the university. No personal identification of teachers or students was included. The project was reviewed and approved by institutional authorities, who confirmed that it met the ethical requirements for studies based on internal academic records. Given that the data was not identifiable and was collected as part of normal academic processes and continuous improvement, and that both teachers and students had given their prior consent in both their employment contracts and the institution’s enrolment form, it was not necessary to obtain individual informed consent.

3. Analysis and Results

Table 1 details the 24 variables obtained for each observation, with the different columns indicating the different quadrants representing the teaching profiles proposed in this study. The purpose of Table 1 is to summarize the distribution in each group of variables for each quadrant; for example, the first row in the first column shows the percentages of academics who have a master’s degree, a doctorate, a bachelor’s degree, and a specialization for the classes in the “lower-left” quadrant. This can be useful, at a descriptive level, to simply identify quadrants or variables that break with the trend.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for each variable of interest and quadrant.

In this regard, it should be noted that the percentage of teachers with master’s degrees is significantly higher in the “lower right” quadrant than in the other quadrants, while the rate of those with doctorates in the same teaching profile is considerably lower. In terms of the contract variable, the lower right quadrant showed a marked pattern of 100% full-time teachers and 0% part-time teachers, in contrast to the other quadrants. In terms of age, the highest average was found in the lower central block and the lowest average in the lower right block. When analyzing the age range, it can be seen that the 31–40 age group was most frequently found in the lower left, while the 41–50 age group had the highest percentage in the upper right, in comparative terms. The same phenomenon was observed for the 51–60 age group, where the highest value was also identified in the upper right. Furthermore, in the case of teachers over 60, the highest value was found in the lower left. Finally, in the gender variable, it can be seen that the lower left quadrant had the highest proportion of women, while the upper right quadrant had the lowest proportion of women.

As for the enrollment variable, the highest average number of students per class was in the lower-left quadrant, while the lowest was in the lower-right quadrant. The distribution of the language variable did not indicate significantly different behaviors between the different teaching profiles. This contrasts with the phenomenon observed in the modality variables, where the online variable had the highest participation in the lower-right quadrant, while the upper-left quadrant had the lowest percentage.

Regarding the curricular level variables, the lower-left and upper-left quadrants showed significantly increased frequencies in the basic block, while the lower-right quadrant tended to have a higher frequency in the intermediate block. It should be noted that the table and associated descriptions do not indicate a significant pattern; they only allow us to identify some trends per quadrant, which were validated in terms of their significance in later stages of the analysis.

Table 2 presents the results of the six logit models, in each of which the dependent variable is one of the six proposed teaching profiles, categorized according to the average teaching evaluation and average academic performance of the group. The amount of data available varied between each model, due to missing values during data collection. For each variable, its relative weight, type of relationship (positive or negative), and corresponding p-value (in parentheses) are shown. The last row of Table 2 shows the percentages of correct predictions—a recommended measure for identifying the goodness of fit and predictive power of each model. In all cases, this percentage was greater than 80%.

Table 2.

Logit models, calculated with standard deviations based on the Hessian.

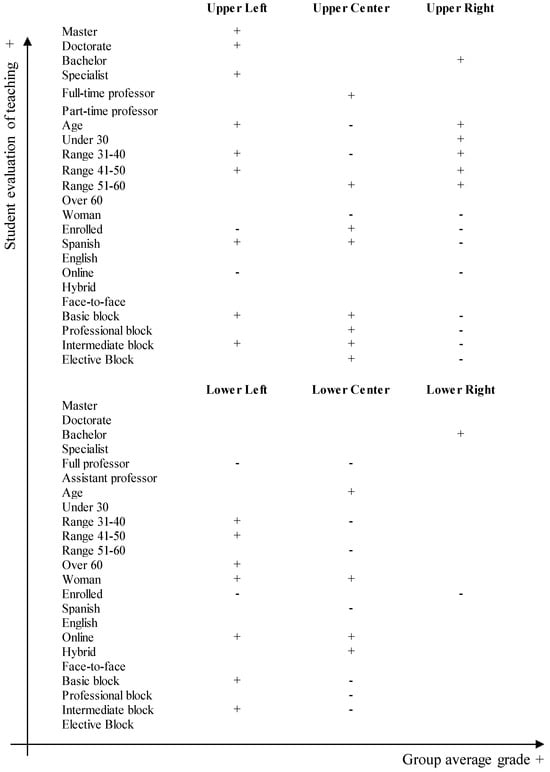

Figure 2 illustrates the variables that had a significant positive or negative effect on each quadrant. For the lower-left quadrant, the age ranges of 31 to 40, 41 to 50, and 60 or older, being female, online modality, the basic block, and the intermediate block had a positive influence, while being a full-time professor and the number of students enrolled had a negative influence. For the lower-center quadrant, the variables age, female, online modality, and hybrid modality had a positive influence; while full-time teacher, age from 31 to 40 and from 51 to 60, Spanish as the language of instruction, basic block, professional block, and intermediate block had a negative influence. For the lower-right quadrant, only two variables were significant: bachelor’s degree, with a positive influence; and enrolled, with a negative influence.

Figure 2.

Summary of the variables found to significantly influence each quadrant. A + is shown when the relationship is significantly positive and − when the relationship is significantly negative.

As for the upper quadrants, for the upper-left quadrant, master’s degrees, doctorates, specializations, being a full-time teacher, age ranging from 31 to 50, Spanish, basic blocks, and intermediate blocks had a positive influence, while enrollment and online modality had a negative influence. For the upper-center quadrant, the significant positive variables were full-time professor, age ranging from 51 to 60, enrolled, Spanish, basic block, professional block, intermediate block, and elective block, while the variables age ranging from 31 to 40 and female were identified as variables with a significant negative influence. Finally, for the upper-right quadrant, the variables identified as significantly positive were bachelor’s degree, age, and all age ranges except 60 years or older; while being female, enrolled, Spanish, online modality, basic block, professional block, intermediate block, and elective block had a negative influence.

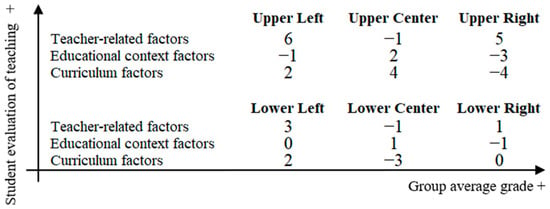

Figure 3 illustrates the net value of the significant variables influencing each quadrant, where the value for a variable with positive influence is +1 and that for a variable with negative impact is −1. It should be noted that the left quadrants present high values for factors related to teachers and curricular level. In the central quadrants, the values associated with teacher- and educational context-related factors tend to be close to 0. Furthermore, there are considerable differences between the upper- and lower-right quadrants and, comparing the upper quadrants with the lower ones, it can be seen that the upper quadrants have values which are significantly greater in magnitude (both positive and negative).

Figure 3.

Net value of the impact of significant variables on each quadrant.

4. Discussion

This study identifies six teacher profiles in relation to students’ academic performance and the SET. For each of these profiles, a series of factors that significantly define it were identified, with each showing different patterns. Once the factors that significantly and consistently characterize each quadrant are identified, it can be assumed that such a classification can be perceived as a teaching typology [4,15].

This typology was developed based on the classification of a set of observations corresponding to the set of classes taught by faculty members in the period from August 2021 to June 2025, according to the student evaluations of teachers and the average academic performance of the groups. This classification reveals factors inherent to the teacher, the educational context, and the curriculum that differ for each quadrant. For example, being a full-time teacher tends to have a positive impact on the upper quadrants; that is, in those characterized by high SET levels. On the other hand, the lower quadrants tend to be negatively influenced by the full-time teacher variable. This is in agreement with previous studies conducted by Holzberger et al. [30] and Yoshida et al. [12], who identified that the quality perceived by students tends to coincide with the stability of the teacher. However, it is important to clarify that being a full-time professor is not equivalent to having pedagogical stability, and the present study cannot determine whether the observed associations arise from contractual conditions, instructional continuity, or other unobserved factors. The characteristics that differentiate each teaching profile in the proposed typology are detailed below.

4.1. Typology of Teaching Profiles

Delving deeper into the teaching profiles segmented by the SET and student academic performance not only “makes the invisible visible” [32] but also allows us to understand the associated phenomena in the context of a typology and could offer greater precision in the description of diverse types of university teaching. Thus, the proposed typology could serve as a basis for strategic training and improvement frameworks, promoting academic quality in educational institutions. As Sim and Mohd Matore [33] suggested, such a typology can be used in initial training or academic support, where the challenges change depending on the stage of teaching at which teachers find themselves. This study presents a typology of teaching profiles that could allow the analysis and profiling of factors inherent to the university educator, the educational context, and progress in the curriculum, as well as their possible impacts on student academic performance.

In the upper left profile, characterized by high SET scores and low academic performance, factors inherent to the faculty member stand out, such as academic degree (master’s and doctorate), age (31 to 50 years), and male gender. Regarding the educational context factor, only the face-to-face modality has an influence. In terms of the curricular level, the phenomenon is significantly positive in the first few semesters of a university course, which correspond to the basic blocks (1st to 3rd semester). The inferential statistics derived from the linear regression model were found to coincide with the descriptive results, with higher degrees, ages between 31 and 50, and male gender also appearing as significant variables. These results coincide with the study of Sohr-Preston et al. (2016) [34], in which the gender and age of the professor was found to affect academic performance in the case of first-year university students, who are still contextualizing themselves to the academic pace of the university. However, these associations should be interpreted with caution, as previous research shows mixed evidence regarding the effect of gender on SET scores (e.g., Salas-Rodríguez et al. [31]), and some of these differences may reflect student biases rather than true instructional quality.

In the lower-left profile, characterized by low SET scores and poor performance, factors inherent to the faculty member also stand out; in particular, this profile comprises a greater proportion of women (56%), thus differing greatly from the previous one. Although age is significant, it is not concentrated on any specific range, with faculty members ranging in age from 31 to 60 or older. Interestingly, of the educational context factors, the online modality is highlighted, as well as the significant influences of the number of enrolled students and curricular level factors—reflected not only in the basic but also the intermediate block (1st to 3rd semester and 4th to 6th semester, respectively). The influence of class modality also aligns partially with prior research, but causal mechanisms cannot be established from the present data. The linear regression models agree in identifying women as being more likely to belong to this profile, but they also identify that classes in Spanish (the natural language of the context) decrease the probability of being in this profile, while online or hybrid modalities increase the probability. This coincides with previous studies [6,35] which mention that educational technology and interactions are essential for maintaining student engagement; this, in turn, explains why online learning without a quality instructional design is perceived negatively.

Thus, we identified that factors inherent to the faculty member (e.g., age and academic degree) and the educational context (e.g., in relation to the teaching modality) influence students’ academic performance, as well as their enjoyment of teaching and their assessment of its quality. This is in agreement with the studies of Boring et al. [36] and Clayson [37], and is complemented by the study of Gleisner Villasmil et al. [15] who reported the influence of not only demographic aspects but also self-reported skills and ease of use of digital learning resources (DLR) for online classes on the phenomena associated with a particular typology. It is also worth noting that these students tend to belong to the basic block of the curriculum and, thus, are only beginning their studies at the university and lack academic habits and greater adaptation to the demanding university system, which may ultimately influence their evaluation of teachers with low academic performance. This differs from the results of Zipser et al. [3] who found no evidence of gender-related differences in quantitative SET scores. However, when analyzing the content of the comments, a variation was observed according to the gender of the educator, although they specified that this may reflect a bias on the part of the students, for example, different expectations according to gender.

The opposite extreme in the upper-right profile, characterized by high grades and high academic performance, indicates significantly high values in factors inherent to both the faculty member and progress in the curriculum. In this profile, male gender stands out as a factor, especially in the professionalization block (7th, 8th, and 9th semesters, i.e., students who are about to graduate from university and who have more practical experience in the workplace). In terms of inferential statistical analysis, it was identified that faculty members with a bachelor’s degree, in the younger age range (30 years or younger), and male gender have increased likelihood of fitting this profile. This coincides with the study of Holzberger et al. [30] who identified that high-quality teachers receive high ratings with higher academic achievements, generally being younger male teachers; in contrast, in another study Salas-Rodríguez et al. [31] individual demographic factors such as gender, school grade, and years of teaching were found not to be significant.

As for the lower-right profile, characterized by low ratings and high academic performance, the predominant factors inherent to the teaching staff are a master’s degree (67%), full-time contract, higher frequency in the 31–50 age range (average age: 44.9 years), and male gender (on average, 55% were men). In terms of educational context factors, on average, there were 14.1 students enrolled in their groups (the lowest average of all profiles), only a small percentage of classes in this profile were taught in English (consistent with the descriptive statistics in Table 1), and 27% were online (the highest percentage of online education among all teaching profiles). In terms of curricular factors, the intermediate block predominates for this profile. The linear regression model highlighted having a bachelor’s degree as the highest educational level and the small number of students enrolled as significant positive variables predicting this profile. This coincides with the fact that classes are typically taught in specific practical laboratories or workshops. Further studies are needed to determine whether the qualities of teachers perceived by their students correspond to the characteristics listed in previous studies [3,38] as being associated with helpful and friendly people or whether the assessment differs from these adjectives, which is expected to help in understanding the reason for the low assessment scores in this profile.

In addition, there are two quadrants in the center of the horizontal axis which refer to academic performance. In this sense, the upper-central profile, with high grades and intermediate academic performance, is characterized by factors inherent to the teacher: having a master’s degree (56%), full-time contract (92%), the 41 to 50 age range (average age, 48.7 years), and male gender (being women in only 35% of cases). In terms of educational context factors, there was an average of 19.9 students enrolled, 93% of these classes were taught in English, and 12% were online. In terms of curricular factors, it should be noted that these classes are mainly in the basic block (43%). In this profile, statistical inference using the linear regression model identified that being a full-time teacher, being between 51 and 60 years old, and teaching classes in Spanish have a positive influence. On the other hand, being a woman had a negative influence.

Finally, the lower-central teaching profile, with low grades and intermediate academic performance, is characterized by a qualification at the master’s level, full-time contract (87%), age range of 41 to 50 (average age, 50.3), and a slightly lower proportion of women (44%). In terms of educational context factors, it should be noted that those with this profile tended to have 19.7 students enrolled per class, 8% of these classes were taught in English, and 18% were online. In terms of curricular factors, 44% of these subjects were taught in the basic block. The linear regression model allowed us to identify that being a woman, as well as an online or hybrid teaching modality, increases the probability of being characterized by this profile. On the other hand, being a full-time teacher and teaching classes in Spanish (the native language of the country where the study was conducted) decreased this probability.

Beyond statistical significance, it is necessary to consider the magnitude of the observed effects. Several coefficients in the logit models—particularly those above 1.0—suggest moderate to substantial changes in the probability of belonging to certain profiles. For example, age ranges 31–40 and 41–50 in the lower-left and upper-left quadrants show coefficients between 0.9 and 1.7, indicating non-trivial increases in the likelihood of falling into these profiles when compared to the reference category. Similarly, the positive effect of being a full-time professor in the upper quadrants (coefficients between 0.49 and 1.30) reflects a meaningful, although not determinative, association with higher SET levels. In contrast, other effects—such as language of instruction or the online modality—present smaller coefficients (typically between 0.2 and 0.5), which, although statistically significant, should be interpreted as modest in practical terms. These patterns suggest that the typology is influenced by combinations of variables with varying degrees of practical importance, and that the explanatory power of the models should be understood in relative rather than absolute terms, particularly considering that some statistically significant predictors produce only limited shifts in probability.

It is important to clarify that, although the typology identified in this study offers a structured way to understand patterns that link academic performance and SET scores, the potential uses mentioned in terms of teacher training, instructional improvement, or course assignment should be understood as hypothetical applications rather than empirically demonstrated effects. The analyses conducted are descriptive and associative in nature; therefore, the results do not allow us to infer causality, nor to conclude that implementing actions based on this typology will necessarily improve teaching quality or modify the distribution of profiles in practice.

Other considerations that must be made in relation to this model are those concerning the validity of the SET. This is because various authors have pointed out the biases that the SET may have due to factors unrelated to teaching evaluation [3,38], that the SET measures the degree to which students like a class [37] rather than the effectiveness of teaching, and that this indicator is more a measure of popularity than of academic quality [36,37]. However, its institutional and academic use is well established in the literature [14,27], it is a complementary but not absolute measure [30,36], and perhaps not primarily, but secondarily, it can reflect the quality and satisfaction of students with the teaching process experienced in a specific class [39].

4.2. Implications for Practice

This study contributes to the growing body of research aimed at understanding teaching profiles and their typologies but with the particularity of being carried out at the university level. These contributions are aimed especially at higher education managers, such as academic directors, who oversee the academic quality of their institutions, whether at the institutional level, by schools and faculties, or by groups of academics under their charge.

The proposed typology could serve as a reference or starting point for university institutions seeking to improve the quality and scope of teaching with the corresponding programming of subjects by type of teaching (profiles and types of teaching). In this regard, the present study proposes a frame of reference for universities and educational institutions. For example, for managers of academic institutions, the proposed teaching typology could serve as a diagnostic tool to identify possible characteristics that, if an educator possesses or tends to possess, a work plan should be established to influence them and bring them to a more suitable profile. This recognition of less favorable profiles could enable the development of specific strategies to promote growth and improvement in teaching practice among all members of the teaching staff.

In addition, mentoring, training, or even appropriate subject assignment strategies could be implemented according to each teacher’s profile. The typology could be used as a framework to explore how to support teachers in moving closer to the upper-middle profile, which is identified as ideal not only because of its high acceptance among students, but also because of its balance between academic demands and student learning strategies. This allows for an iterative process of continuous improvement, thus promoting the quality of university teaching.

In conclusion, this typology helps to describe and classify different teaching profiles, but it does not allow causal interpretations. The results cannot show that moving teachers from one profile to another will produce better learning or higher teaching quality. Therefore, the value of this typology is mainly descriptive and diagnostic, and its practical use should be considered with caution.

4.3. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

This study also presents several methodological limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the classification algorithm has a heuristic nature, as it relies on expert judgement from institutional authorities rather than on statistical optimisation; therefore, its generalisability may be limited. In the same way, the 80% threshold used to define the ideal quadrant is an arbitrary decision based on institutional practice, and alternative thresholds were not tested. In addition, the typology was not subjected to external validation, cross-validation, or sensitivity analyses, which limits the statistical robustness of the model and may introduce biases derived from the chosen decision rules and outlier treatment. Another limitation relates to the SET, which, despite its wide institutional use, has recognised validity issues and potential biases that may influence the typology. The results also stem from data collected in a single private university, which restricts the generalisation of the findings to other institutional contexts. Finally, although the study was approved by institutional authorities and used anonymised administrative data, no formal ethics committee approval was required, which should also be recognised as a limitation of the research design.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusion of this study lies in the proposed typology, which allows teaching profiles to be classified as they are found in the real educational environment. The typology consists of six distinct profiles, each with clearly defined characteristics:

- Upper left, with high SET scores and low academic performance;

- Lower left, with low SET scores and low performance;

- Upper right, with high scores and high academic performance;

- Lower right with low scores and high academic performance;

- Upper center, with high scores and intermediate academic performance;

- Lower center with low scores and intermediate academic performance.

After segmenting all observations by professor and academic group into six quadrants (representing teaching profiles), it was determined that each profile is characterised by unique factors inherent to the teaching staff, the educational context, and the curricular level.

This typology not only helps to identify the relationship between Student Evaluation of Teaching (SET) and academic performance, but also to understand the phenomenon of university teaching within the institutional context in HEIs as a first approach. This is possible by identifying trends and influencing factors in each typology in general, and, in particular, those teachers who tend to appear repeatedly in a certain typology, especially at the extremes.

This facilitates academic managers in diagnosing university teaching among their teaching staff in order to generate improvement and support strategies, as well as to delve deeper into the phenomenon by type, allowing for the establishment of continuous and personalised improvement plans with the aim of increasing the quality of teaching while maintaining an adequate level of academic rigour. This is with a view to promoting the necessary improvement to bring them to the higher education profile considered ideal for its balance between academic performance and teaching assessment, which favours dynamic and continuous improvement in teaching patterns, beyond identifying whether the subject taught by each professor is the most suitable according to the typology trend in which it usually appears.

The development of this typology expands the theory and practice related to teaching profiles in the university setting. The literature lacked a comprehensive and integrative perspective on the analysis of teaching profiles when considering the university environment with three types of factors: characteristics inherent to the teacher, the educational context and curricular advancement, with predictive models that would allow for a quantitative and objective approach to the phenomenon of university teaching. Unlike previous studies, the results are not directly comparable with the existing literature, beyond the context of the study, due to the methodology used and the variables considered.

The main contribution lies in identifying trends in the proposed teaching typology at the university level. This typology helps to describe and classify different teaching profiles. The value of this typology is mainly descriptive and diagnostic, as a starting point for a quantitative in-depth study of the phenomenon of teaching profiles in the university environment. Its practical use should be considered as a guide rather than a determining factor. The proposed typology of teaching profiles can be used to expand theory, research, and teaching practice in the university environment. Specifically, it can support educational managers responsible for the academic improvement of their educational organisations and thus promote academic quality, either through teacher professionalisation or educational reflection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.-H. and E.M.-O.; Methodology, E.M.-O.; Software, M.S.-P.; Validation, M.S.-P.; Investigation, C.L.-H., E.M.-O. and M.S.-P.; Resources, E.M.-O.; Data curation, M.S.-P.; Writing—original draft, E.M.-O. and M.S.-P.; Writing—review & editing, E.M.-O. and M.S.-P.; Supervision, C.L.-H., E.M.-O. and M.S.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by Institution Committee due to Legal Regulations (https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/regley/Reg_LGS_MIS.pdf, accessed on 8 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO. Higher Education Global Data Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Forest, J.J.F. (Ed.) University Teaching; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipser, N.; Kurochkin, D.; Yu, K.W.; Mincieli, L.A. Exploring Relationships Between Qualitative Student Evaluation Comments and Quantitative Instructor Ratings: A Structural Topic Modeling Framework. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.N.; Blocker, M.S.; Gittens, O.S.; Long, A.C.J. Profiles of teachers’ classroom management style: Differences in perceived school climate and professional characteristics. J. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 100, 101239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. Profiles of Mathematics Teachers’ Job Satisfaction and Stress and Their Association with Dialogic Instruction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidot-Lefler, N. Teacher Responsiveness in Inclusive Education: A Participatory Study of Pedagogical Practice, Well-Being, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.C.G.; Van Luijk, S.J.; Galindo-Garre, F.; Muijtjens, A.M.M.; Van Der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Croiset, G.; Scheele, F. Five teacher profiles in student-centred curricula based on their conceptions of learning and teaching. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nushi, M.; Momeni, A.; Roshanbin, M. Characteristics of an Effective University Professor From Students’ Perspective: Are the Qualities Changing? Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 842640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo López, B.; Sánchez Peris, F.; Ros Ros, C.; Ferreras Remesal, A. Estilos docentes de los profesores universitarios. La percepción de los alumnos de los buenos profesores. Rev. Iberoam. De Educ. 2010, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano-Larrea, P.; Basantes-Vásquez, M.; Ruiz-Lapuerta, I. Autorregulación del aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios: Un estudio descriptivo. Cátedra 2021, 4, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, H. Institutional Profiling for Educational Development: Identifying Which Conditions for Student Success to Address in a Given Educational Setting—A Case Study. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2025, 26, 1100–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, F.; Conti, G.J.; Yamauchi, T.; Kawanishi, M. A Teaching Styles Typology of Practicing Teachers. J. Educ. Learn. 2023, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y. Mitigation of Regional Disparities in Quality Education for Maintaining Sustainable Development at Local Study Centres: Diagnosis and Remedies for Open Universities in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Orozco, E.; López-Hernández, C.; Briseño, H.; Soto-Pérez, M. Contextual differences in the student evaluation of teaching (SET) in Mexico: Comparing education face to face and online classes between different faculties. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2025, 19, 552–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleisner Villasmil, L.; Lindvall, J.; Sund, L.; Sert, O. Teacher profiles concerning upper secondary school teachers’ views on and use of digital learning resources for teaching—A cluster analysis. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 68, 596–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Donche, V.; Van Petegem, P. Teachers’ profiles in education for sustainable development: Interests, instructional beliefs, and instructional practices. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 30, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pill, S.; SueSee, B.; Davies, M. The Spectrum of Teaching Styles and Models-Based Practice for Physical Edu-cation. Eur Phy Educ Rev 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, J.T.; Leitner, D.W. A comparison of ordinary least squares and logistic regression. Ohio J. Sci. 2003, 103, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, C.I.; Rothmann, S.; Kloppers, M.M.; Chen, S. Promoting Sustainable Well-Being: Burnout and Engagement in South African Learners. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Echeverría, S.; Canales-Lacruz, I.; Murillo-Pardo, B. Whole Systems Thinking and Context of the University Teacher on Curricular Sustainability in Primary Education Teaching Degrees at the University of Zaragoza. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamrawi, N.; Abu-Tineh, A.; Shal, T. Teaching Licensure and Education Quality: Teachers’ Perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Tariq, R.H.; Topping, J. Students’ Perception of University Teaching Behaviours. Teach. High. Educ. 2009, 14, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.L.; Yeigh, T.; Hudson, S. Secondary teachers’ beliefs about the importance of teaching strategies that support behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement in the classroom. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 9, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Cruz, I. Efecto de la enseñanza virtual sobre el rendimiento académico universitario: Un análisis de regresiones de Difference in Difference (Effect of virtual teaching on university academic performance: A Difference in Difference regression analysis). Pixel-Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2024, 70, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, F.E.; Schrader, F.W.; Helmke, A. Quality of instruction and achievement outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1989, 13, 895–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, P.F.; Kieffer, M.J. Describing Profiles of Instructional Practice: A New Approach to Analyzing Classroom Observation Data. Educ. Res. 2015, 44, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A.S.; Boysen, G.A.; Gurung, R.A.R. An Evidence-Based Guide to College and University Teaching; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara Salcedo, L.M.; Rodríguez Ávila, G.I.; Parada Ramírez, A.; Pinzón Niño, O.I.; Valderrama Castiblanco, J.J. Clima de Aula, Estilo Docente y Educación Para la Convivencia y la Ciudadanía; Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concina, E. Effective Music Teachers and Effective Music Teaching Today: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzberger, D.; Praetorius, A.K.; Seidel, T.; Kunter, M. Identifying effective teachers: The relation between teaching profiles and students’ development in achievement and enjoyment. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Rodriguez, F.; Lara, S.; Martínez, M. Teacher Efficacy Beliefs: A Multilevel Analysis of Teacher-and School-Level Predictors in Mexico. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.K.; Samavedham, L. The learning process matter: A sequence analysis perspective of examining procrastination using learning management system. Comput. Educ. Open 2022, 3, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.H.; Mohd Matore, M.E.E. The relationship of Grasha–Riechmann Teaching Styles with teaching experience of National-Type Chinese Primary Schools Mathematics Teacher. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1028145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohr-Preston, S.L.; Boswell, S.S.; McCaleb, K.; Robertson, D. Professor Gender, Age, and “Hotness” in Influencing College Students’ Generation and Interpretation of Professor Ratings. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasić, N.; Glušac, D.; Makitan, V.; Jokić, S.; Ljubojev, N.; Vignjević, K. Promoting Sustainable Education Through the Educational Software Scratch: Enhancing Attention Span Among Primary School Students in the Context of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boring, A.; Ottoboni, K.; Stark, P. Student Evaluations of Teaching (Mostly) Do Not Measure Teaching Effectiveness. Sci. Res. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayson, D. The student evaluation of teaching and likability: What the evaluations actually measure. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelber, K.; Brennan, K.; Duriesmith, D.; Fenton, E. Gendered mundanities: Gender bias in student evaluations of teaching in political science. Aust. J. Political Sci. 2022, 57, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safapour, E.; Kermanshachi, S.; Taneja, P. A Review of Nontraditional Teaching Methods: Flipped Classroom, Gamification, Case Study, Self-Learning, and Social Media. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).