Abstract

We investigate the effect of financial openness on corporate resilience. Corporate resilience metrics refer to the processes through which firms respond to crises, encompassing the capabilities developed during adaptation, absorption, innovation, recovery, and development. Using dynamic difference-in-differences (DID) models and panel data on Chinese A-share listed firms from 2009 to 2022, we found that firms included in the Shanghai-Hong Kong and Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SSHK) lists exhibited higher levels of corporate resilience after the openness. Introducing foreign ownership and improving the quality of information disclosure are two plausible pathways through which financial openness can promote corporate resilience. At the same time, the degree of industry competition and level of external financing dependence moderate the results. Importantly, corporate resilience moderates the positive long-term effect of financial openness on firms’ total factor productivity (TFP). These findings highlight that fostering corporate resilience is not merely an outcome but a critical condition for translating financial integration into sustainable productivity gains, enlightening resilience-oriented policymaking in emerging markets undergoing reform.

1. Introduction

Financial openness, as an institutional reform at the national strategic level, reshapes global resource allocation dynamics and contributes to sustainable economic stability by removing cross-border capital flow restrictions and integrating international investors into domestic markets [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Over the past four decades, many developed and emerging economies have gradually relaxed capital controls, sparking widespread scholarly debate on the empirical effects of these policies. Studies have confirmed that financial openness reduces capital costs through risk diversification [1,6,8,9], alleviates resource misallocation [2,3,4,5,7], and increases factor productivity [3,4,5,6,7], thereby boosting economic growth [1]. However, the accelerated economic growth resulting from financial openness cannot be entirely attributed to a slight reduction in the cost of capital and moderate investment growth [1,9]. Bekaert et al. (2011) [4] argue that this growth effect is predominantly permanent rather than temporary, as openness’s influence on factor productivity growth exceeds its impact on detrimental loss in growth. Moshirian et al. (2021) [6] further assert that this productivity growth effect is both temporary and permanent, with increased innovation from openness being a key contributing factor. Although the scholarly literature has documented considerable advances in understanding the impact of financial liberalization on economic growth, some researchers have argued that such liberalization may lead to heightened fluctuations in economic growth [10], short-term market volatility [11], and an escalation of systemic risk for non-financial firms [12]. Therefore, the effects of financial openness remain to be further explored, particularly its role in fostering long-term resilience and sustainable development. Notably, the current literature has not examined how financial openness might influence corporate resilience.

Corporate resilience constitutes a fundamental capability that enables enterprises to endure and thrive amid adversity [13]. In the contemporary BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, Incomprehensible) era, it is imperative to bolster corporate resilience to navigate extreme environmental changes that may threaten organizational survival effectively. The convergence of cross-border capital flows with financial openness, in a volatile international risk environment, offers a unique opportunity to enhance resilience [14]. Both opportunities for global market entry and systemic risks influence corporate resilience. On the one hand, financial openness alleviates restrictions on cross-border capital flows, thereby easing corporate financing constraints and augmenting firms’ capacity to share risks [1,6,7,15,16,17]. This process improves factor productivity, leading to economic growth effects [3,4,6] and offers a solid resource base for strengthening corporate resilience. Furthermore, the involvement of international institutional investors in corporate governance contributes to the improvement of governance practices and the elevation of governance standards [18], thereby enhancing firms’ ability to withstand adversity. Conversely, financial openness enhances the connection between domestic and international markets. In the event of a significant shock to one market, this liquidity fragility can intensify cross-market volatility and contagion through the global risk network [19,20], thereby exposing firms to heightened systemic risk resonance [12] and weakening corporate resilience.

Given the dual nature of financial openness—its ability to both diversify non-systemic risk and increase systemic risk contagion—it is crucial to further examine whether it supports or hampers the development of corporate resilience. Dynamic capability emphasizes the importance of resource reconfiguration and strategic flexibility as critical components of resilience [21]. The existing literature rarely examines the relationship between financial openness and corporate resilience from a dynamic capability perspective. In response to this gap, this study proposes an integrative framework, “institutional reform, resilience generation, and economic consequences”, that elucidates how financial openness can influence corporate resilience and total factor productivity (TFP). This framework provides a foundation for resilience-centered policymaking in emerging markets undergoing institutional transformation. Notably, we found that corporate resilience plays a vital moderating role in the relationship between financial openness and TFP. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of the economic implications of financial openness.

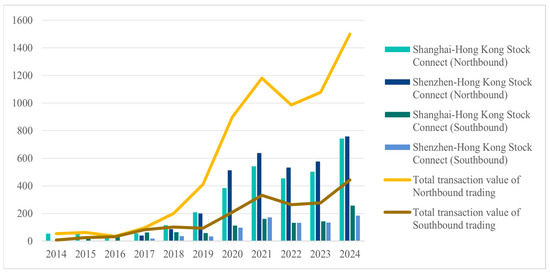

China’s stock market’s systematic openness follows the principle of gradual, prudent reform. The implementation of the “Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect” on 17 November 2014, and the “Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect” on 5 December 2016 (SSHK) marked a period of deep connectivity. The SSHK scheme enables interoperability between the mainland and Hong Kong exchanges through innovations in bidirectional trading. As of 2024, the average daily northbound and southbound capital flows were RMB 150 billion and RMB 44.3 billion (Figure 1). The programs elevated foreign A-share holdings to RMB 2.1 trillion as of 30 June 2024, representing 71% of internationally held A-shares. In June 2018, the inclusion of A-shares in the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) indices amplified northbound trading volumes. Subsequently, sporadic capital outflows happened amid Sino–U.S. trade tensions and pandemic disruptions. Despite the short-term volatility, long-term capital flows exhibit an upward spiral. This “volatile gradualism” underscores the dual role of financial openness. On the one hand, it can enhance market liquidity, increase product diversity, and expand the investor base. On the other hand, it also exposes companies to potential risks. These can be affected by emotions and shifts in overseas markets, which can lead to more market volatility, increasing the risk of widespread financial problems.

Figure 1.

Northbound and southbound trading day flows (Unit: RMB 100 million). The figure illustrates the daily average capital flows between the Chinese A-share markets (Shanghai and Shenzhen) and the Hong Kong stock market from 17 November 2014, to 31 December 2024, including the total daily buy–sell turnover (averaged) for northbound and southbound transactions. Data Source: Compiled by the authors using data from the Wind Database on daily northbound and southbound capital flows.

The institutional openness of China’s stock markets provides a quasi-natural experiment to analyze the impact of financial openness on corporate resilience. Rooted in dynamic capabilities theory, we developed a corporate resilience indicator based on five dimensions: adaptive, absorptive, innovative, restorative, and developmental capacities. This was combined with an entropy weighting method to analyze the influence of openness on resilience. To address endogeneity concerns, we used the staggered implementation of China’s SSHK programs as a quasi-natural experiment, employing a dynamic DID design on longitudinal data from Chinese A-share-listed companies (2009–2022). Our findings reveal that financial openness enhances corporate resilience through two channels: introducing foreign ownership and improving the quality of corporate information disclosure. These results are robust, as confirmed by parallel trend tests, placebo tests, PSM-DID, core variable substitution, and model re-specification. Heterogeneity analyses highlight the moderating effects of industry competition and external financing dependency on policy effectiveness. Finally, economic consequence assessments show that financial openness boosts total factor productivity growth, with this effect moderated by enhanced resilience over the long term.

The marginal contributions of this study unfold as follows: First, it extends the research paradigm on the micro-level consequences of financial openness. Existing literature focuses on the direct effects of openness on corporate performance, such as green innovation [15,16] and firm operating performance [2]. They overlook the dynamic process through which openness shapes internal organizational capabilities. Departing from this approach, we establish an analytical framework of “institutional reform—resilience generation—economic consequences” from a process-oriented perspective on the development of corporate resilience. Our study provides empirical evidence of the resilience-enhancing effects of financial openness policies. Additionally, building on the research of Moshirian et al. (2021) [6], we incorporate corporate resilience as a channel for analyzing the micro-growth effects of financial openness. This framework allows for a more precise assessment of the policy implications of the institutional stock market opening. Second, this study enriches the literature on the antecedents of corporate resilience. Current literature mainly employs longitudinal case studies or focuses on internal or industry-level factors such as digital transformation [14], corporate social responsibility [22,23,24,25], and open innovation [26]. In contrast, leveraging China’s stock market opening as a quasi-natural experiment, we identify how financial openness—a macro-institutional factor—strengthens resilience through two concrete channels: introducing foreign ownership and improving the quality of information disclosure. This finding expands the study of resilience antecedents from firm-internal factors to exogenous institutional drivers, revealing a new pathway through which macro-level policy shapes organizational resilience. Furthermore, we clarify that enhancing corporate resilience is a critical prerequisite for unlocking the long-term benefits of financial openness, thereby bridging the complete logical chain from antecedents to economic consequences.

The structure of this study is outlined below. Section 2 provides a systematic review of the existing academic literature and formulates testable hypotheses. Subsequently, Section 3 details the data collection methodology, econometric model specification, and variable operationalization, followed by a presentation of preliminary statistical analyses. Section 4 delineates the baseline results and the robustness tests. Section 5 investigates the potential mechanisms by which capital market openness affects corporate resilience. Section 6 presents the findings of the economic consequences analysis, and Section 7 concludes.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Financial Openness

Research on the economic consequences of financial openness primarily focuses on two aspects: the effect of non-systematic risk diversification and that of systematic risk contagion.

From the perspective of the risk diversification effect of unsystematic risk, financial openness accelerates cross-border capital flows and reduces the cost of equity financing through improved risk-sharing [9]. This increases the availability of liquid capital in the market, which helps alleviate the severe financing constraints faced by most firms [16]. With greater access to funding, enterprises can reserve more liquidity to reduce financial vulnerability [25]. At the same time, professional international institutional investors serve as key drivers for improving governance and promoting the convergence of governance practices across borders. They may directly influence management, exercise voting rights, or “vote with their feet” to encourage or pressure firms into adopting more strategic governance practices [18]. These practices include, for example, advancing technological innovation [6] and building digital resilience [14,27], which collectively enhance firms’ flexibility in the face of external shocks. In addition, the need to align with international capital market information disclosure standards, coupled with increased analyst coverage, compels firms to enhance their reporting transparency [28]. This greater transparency subsequently attracts more investor attention and intensifies pressure from stakeholders. This practice deters management from seeking short-term profits through aggressive tax avoidance or financial manipulation [29], which in turn strengthens corporate stability and improves the firm’s capacity to withstand external shocks. Consequently, the risk diversification effect arising from financial openness enhances a firm’s access to liquid capital, attracts professional institutional investors, and aligns information disclosure practices with international standards. These combined forces strengthen firms’ adaptability, operational flexibility, and overall stability in response to market fluctuations, thereby fostering stronger corporate resilience.

However, the adverse consequences of capital market openness may counteract its benefits. From a risk contagion perspective, heightened financial openness in emerging economies tends to compress banks’ short-term profitability, as it increases the volatility of capital inflows and exerts downward pressure on bank lending rates. This situation compels banks to adopt riskier strategies and over-leverage, ultimately increasing the likelihood of banking crises [28]. Banking crises not only amplify contagion but also reinforce cross-market volatility spillovers through internal financial linkages and amplification mechanisms [19,20]. As a result, firms face heightened exposure to systemic risk resonance [12], which significantly constrains their ability to cultivate resilience. First, speculative “hot money” flows driven by short-term arbitrage and high liquidity sensitivity magnify market volatility. When exchange rate shocks or geopolitical risks escalate, speculative capital accelerates capital outflows from emerging markets to avoid currency depreciation, tightening liquidity in the host country’s financial markets and increasing the risk of asset price overshooting [30]. This leads to financial system fragility, thereby reducing firms’ liquidity and improving their financial vulnerability. In addition, imperfections in emerging-market institutions and broader distortions in capital markets can exacerbate risky behavior and crises [11]. Those indirectly undermine the long-term stability of firms. Second, foreign investors’ short-termism pressures firms to prioritize quarterly earnings over sustainable resilience, slashing critical R&D and ESG investments in favor of a precarious “resilience-performance” trade-off. These practices undermine the continuity of firms’ strategies, accumulate business risks, and lead to negative stock market pricing [31]. These frictions limit firms’ adaptability and destabilize them, often weakening their resilience. Therefore, the relationship between financial openness and corporate resilience remains an issue that requires further study.

2.1.2. Corporate Resilience

Resilience is a physical property that denotes a material’s ability to absorb energy during plastic deformation and fracture. It was first applied in ecology to denote an ecosystem’s ability to buffer itself from external shocks and to absorb and evolve. Simultaneously, its fundamental structure and function remain essentially unchanged [32]. However, organizational-level resilience is situational, multidimensional, complex, and dynamic. There is no consensus on the meaning of corporate resilience, and scholars have approached it from multiple perspectives. From a “results perspective”, organizational resilience refers to performance after environmental disruptions, especially the extent of losses and the time required for recovery [33,34]. From a “dynamic process” perspective, resilience is the process of developing and utilizing a firm’s capability endowment in response to adverse disturbances [14,35,36,37]. Currently, the prevailing viewpoint is the “capability perspective”, which considers resilience as the consistent ability to cope with disturbances or shocks [22,27,38,39,40]. Combined with dynamic capability theory, this study adopts a dynamic process perspective. It defines firm resilience as the process of continually upgrading a firm’s dynamic capability and achieving an adaptive leap in the face of adversity by dynamically reconstructing the resource base, optimizing the organizational structure, and repairing the relationship network. Gaining insight into the connotations of firm resilience and its antecedents can provide a more profound understanding of the broader significance of firms within the national economy.

Most current research on the factors affecting firm resilience focuses on how firms reconfigure their dynamic capabilities in response to external shocks (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic, terrorism, geopolitical risks, natural disasters, and financial crises). In crisis-driven adversity, geopolitical risks compounded by policy uncertainty exacerbate corporate financial fragility [41]. Nevertheless, latent risk-buffering functions manifest through digital finance [42], intangible assets [43], organizational culture [44], and CSR initiatives [24]. In comparison, government subsidies accelerate post-crisis recovery [45]. Notably, certain firms thrive under extreme adversity. Addressing this paradox, Branzei and Abdelnour (2010) [46] demonstrated that in developing economies, prolonged exposure to terrorism can cultivate psychological resilience among entrepreneurs. This resilience, in turn, is associated with higher economic returns—an effect particularly pronounced among female entrepreneurs and those with informal or low educational attainment [46]. In contrast, some studies have focused on firm factors, noting that digital infrastructure, ESG performance, corporate social capital, digital transformation, and managers’ attributes are core levers for improving resilience in the face of competition-driven adversity [22,26,38,47,48,49,50,51]. For example, Ambulkar et al. (2015) [52] revealed that resource reconfiguration capabilities mediate resilience outcomes, synergizing with risk management infrastructures. Not all social and environmental practices enhance resilience equally. DesJardine et al. (2019) [33] bifurcated resilience into stability and flexibility and found that strategic practices outperform tactical ones in bolstering resilience.

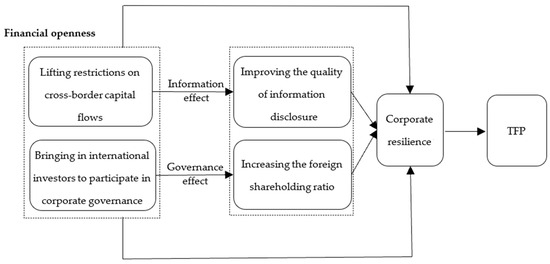

In summary, corporate resilience management underscores the importance of firms’ ability to proactively adapt and reconfigure resources, rather than passively accepting external shocks. This aligns with Brunnermeier’s view that macroeconomic and financial development should shift towards resilience management beyond the scope of traditional risk management [53]. While existing literature has contributed to understanding corporate resilience’s connotations and influencing factors. Corporate resilience as a dynamic, multidimensional, and process-oriented concept may be affected by different factors across scenarios. Due to limitations in research contexts, quantitative studies on enterprise resilience based on corporate data and practical observations are relatively scarce. In light of this, our study leverages the quasi-natural experiment of China’s stock market opening to investigate the impact of financial openness on corporate resilience. Furthermore, it explores how resilience moderates the effect of openness on firms’ TFP. The logical framework of this study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The logical framework.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

From a macro perspective on institutional change, China’s policy-driven stock market opening does not merely introduce capital as an additional factor of production. Rather, it constitutes a process of systemic empowerment that strengthens enterprises’ fundamental capabilities. This process reshapes both the external resource environment and the internal operating mechanisms of enterprises by introducing foreign ownership and international rules and standards. The competitive pressure and demonstration effect stemming from financial openness compelled firms to move beyond their established practices, thereby prompting the development of more resilient business models. More importantly, it enhances corporate governance, information transparency, and the resource bases [6,15,54,55], providing firms with both the strategic assets and the dynamic capabilities essential for shock absorption. This enables firms not only to withstand external shocks effectively but also to achieve adaptive growth. Therefore, we anticipate that financial openness acts as a key external institutional shock capable of comprehensively empowering firms, which significantly enhances their overall resilience. Accordingly, we propose the basic hypothesis:

H1.

Financial openness enhances corporate resilience.

First, drawing on corporate governance and resource dependence theories, financial openness—facilitated by introducing foreign ownership—strengthens internal oversight and redefines the firm’s strategic resource boundaries. Corporate governance theory emphasizes that the involvement of foreign shareholders can effectively mitigate agency conflicts, limit managerial short-term focus, and encourage strong corporate governance practices [18]. International investors, upon their introduction, not only enforce market discipline through “voting with their feet”, but also reshape the allocation of decision-making power by vying for board seats [56]. This dual “exit–voice” market mechanism simultaneously deters managerial rent-seeking and encourages more capable managers to improve corporate governance practices further [57]. During exogenous shocks, better corporate governance practices can help reduce market volatility [43]. Foreign investors’ governance oversight boosts ESG transparency, easing financing [57], and deters managerial rent-seeking by penalizing governance issues [29]. This oversight thereby functions as a buffer against systemic risks. This paradigm shift from “passive defense” to “proactive adaptation” is, in essence, an organizational leap in resilience driven by the optimization of governance structures. Resource dependence theory further argues that companies, as open systems, rely on acquiring critical resources from their external environment to survive and grow. Limited domestic financial resources mainly constrain firms that are highly dependent on external financing. By incorporating foreign shareholders, financial openness furnishes firms with essential economic and strategic resources, including expertise in international markets and access to advanced technology channels [6]. This development substantially diminishes reliance on domestic financing channels and strengthens resource autonomy and bargaining power in the face of external shocks. Therefore, the governance and resource effects of foreign ownership are mutually reinforcing, collectively expanding firms’ strategic options. This enables proactive strategies— such as counter-cyclical investments and cross-border mergers and acquisitions—in response to shocks, marking a decisive shift from passive defense to active adaptation. Based on the analysis mentioned above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

Financial openness enhances corporate resilience by introducing foreign ownership participation and enhancing corporate governance practices.

Second, integrating insights from information asymmetry and dynamic capability theories, we argue that higher-quality corporate information disclosure lowers capital costs while simultaneously enhancing the firm’s capacity for dynamic adjustment. According to information asymmetry theory, high-quality information disclosure can alleviate external financing constraints and provide resources to support resilience. Meanwhile, the dynamic capability theory further elucidates that corporate resilience fundamentally manifests as the organization’s dynamic capacity to perceive, acquire, and reconfigure resources in response to rapid environmental changes [21]. Financial openness compels companies to adhere to higher international disclosure standards—such as ESG disclosures and detailed explanations of risk factors—which in turn triggers increased analyst coverage and media attention [58]. The resulting gains in information transparency, reliability, and comparability are vital for developing dynamic capabilities. Transparent and timely information flow enhances management’s awareness of external market trends, technological advancements, and supply chain risks, facilitating the early identification of both crises and opportunities. Conversely, it also transmits clear performance pressures throughout the organization, which fosters internal process optimization and guides the efficient allocation of resources. For instance, firms may accelerate digital transformation to boost operational flexibility [14] or restructure R&D resources to drive technological innovation [6,15,16]. This enhancement in disclosure quality thus directly empowers the entire dynamic adaptation cycle—from perception to execution—transforming informational advantages into concrete strategic and operational adjustment capabilities. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

Financial openness strengthens corporate resilience by improving the quality of firms’ information disclosure.

3. Data and Empirical Model

3.1. Data and Sample

The sample examined in this study encompassed the 2009–2022 timeframe. Our analysis used financial data for Chinese A-share listed companies from two authoritative sources: the CSMAR and Wind Database (WIND), and the eligible stock list for the SSHK scheme on the website of the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited. Provincial-level data were sourced from China’s National Bureau of Statistics (CNBS), and institutional quality metrics (Market) were based on the marketization index of Wang et al. [59]. Consistent with prior methodology [29], the treatment group comprised firms that entered the SSHK scheme at its inception and maintained continuous participation. Our analysis excludes post-2014 listings on the Chinese Stock market and firms with B-share or H-share issuances to control for cross-listing effects. After deleting sample observations with significant missingness in core variables, our baseline full sample consisted of 15,762 firm-year observations. All continuous variables were constrained to the upper and lower 1% of the interquartile range to minimize the effects of extreme values.

3.2. Empirical Model

The impact of stock market liberalization on corporate innovation takes effect three years after the official announcement year [6]. Corporate resilience, like enterprise innovation, is the result of long-term accumulation. The impact of financial openness on firm resilience may not be immediately evident. Drawing on the views of Moshirian et al. (2021) [6], this study hence assumes that the impacts of financial openness manifest within three years after opening. We employed the following dynamic difference-in-differences (DID) model to investigate the effect of China’s capital market openness on corporate resilience:

where Resi,t represents the resilience level of company i in year t. SSHKi,t−3 is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 when the company participates in the SSHK scheme at the end of each year and 0 otherwise, observed at t − 3. The coefficient estimate β captures the overall impact of financial openness on corporate resilience. This study controlled for unobservable heterogeneity at both the individual and temporal levels by incorporating firm-fixed effects and year-fixed effects. Additionally, we controlled for firm-level variables measured in year t − 1.

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

Corporate resilience (Res) describes an organization’s dynamic process of building capacity to reorganize resources, processes, and relationships during crises, while maintaining, repairing, and strengthening adaptability and flexibility to achieve growth despite adversity. This reconfiguration capability is critical for firms to withstand the impacts of crises and has significant implications for sustainable development. Current methods for assessing corporate resilience fall into three primary categories. The first type involves variable substitution methods, such as using Z-scores to indicate financial fragility [41], evaluating the severity of stock price losses and recovery times as measures of corporate resilience [33,38,42], and measuring corporate resilience using profitability and employment figures [60]. The second approach employs project scales to measure organizational resilience [22]. The third method uses a composite index. For instance, Zou et al. (2024) [51] measured corporate resilience across five dimensions: adaptability, innovation capacity, absorptive capacity, recovery capability, and financial capacity. Each of these three methods has its merits; however, the composite index system approach can avoid the partiality of single-variable analyses and the subjectivity of scale selection. Furthermore, it is essential to consider a firm’s ability-building process when confronting challenges and shocks from a process-oriented perspective within resilience theory. In comparison, the comprehensive indicator system method has the advantage of holistically considering the formation process of enterprise resilience. Building on this rationale, we adopted Zou et al.’s measure framework [51], utilizing the dynamic capabilities related to adaptation, innovation, absorption, recovery, and development from adversity across five processes. Additionally, we integrated an entropy-weighting method to assess corporate resilience.

Specifically, adaptive capacity refers to an organization’s core ability to adjust its strategies, products, services, and operations to evolving market conditions. The capacity enhances responsiveness to technological change and allows the organization to transform disruptions into growth opportunities. Adaptive capacity is measured by the coefficients of variation in annual expenditures on research and development (R&D), capital, and advertising. Lower values of these coefficients correspond to greater adaptive capacity. Innovative capacity denotes a firm’s ability for self-renewal through reconfiguring organizational structures and processes, as well as fostering new operational paradigms and value creation, even amid adversity. We approximate innovative capacity by aggregating standardized metrics of R&D expenditure, R&D personnel intensity, and invention patent counts. Higher composite scores indicate greater innovation capability. Absorptive capacity reflects an organization’s ability to internalize external knowledge and resources, thereby enhancing risk identification and enabling agile responses to market fluctuations. This capacity is proxied by R&D intensity, measured as the ratio of annual R&D expenditures to total revenue. A higher ratio indicates greater absorptive capacity. Recovery capacity refers to how quickly an organization can regain operational stability after a disruption. This ability is vital for maintaining supply chain robustness. It is quantified by the three-year industry-adjusted standard deviation of return on assets (Roa). Lower standard deviation values indicate a superior recovery capacity. Developmental capacity enhances a firm’s financial resilience during crises. It is defined as financial flexibility, which comprises two components: cash flexibility (measured as the firm’s cash ratio minus the industry average), and debt flexibility (max [0, industry leverage ratio minus the firm’s leverage]). Higher values represent stronger developmental capacity. To mitigate subjective bias in weighting, we employed entropy weighting. This data-driven method assigns objective weights to the five dimensions based on their information content to compute the composite corporate resilience index.

3.3.2. Independent Variable

SSHK is a proxy for financial openness. It is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 when the company participates in the SSHK scheme at the end of each year and 0 otherwise, measured in year t − 3.

3.3.3. Control Variable

Following the literature on financial openness and corporate resilience [15,22,31], we controlled for several corporate characteristics that may be related to both. These included corporate size (Size), leverage (Lev), return on assets (Roa), growth (Sales), market-to-book ratio (MB), listing age (Listage), board size (Board), and cash holdings (Cash) as control variables. Appendix A provides detailed definitions of all variables used in our analysis.

3.4. Summary Statistics

Table 1 reports a mean corporate resilience score (Res) of 0.325, indicating that most listed companies exhibited relatively low levels of corporate resilience, with substantial variation among companies (the maximum difference was approximately 0.675). Additionally, 31.4% of the firms in the sample were included in this scheme.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regressions

4.1.1. The Impact of Financial Openness on Corporate Resilience

Table 2 presents the impact of financial openness on corporate resilience, along with the estimated results for Model (1). Columns (1) and (2) demonstrate statistically significant positive coefficients for SSHKt−3 at the 1% level, indicating that the implementation of SSHK programs enhanced the resilience levels of eligible firms. Economically, the programs increased the resilience level of treated firms (relative to control firms) by 10.22% of the standard deviation of firm resilience (=0.0138/0.135). This demonstrates that financial openness has a substantial economic impact on strengthening firm resilience. In Column (3), following the approach of previous research [6], our empirical specification accounts for industry-specific growth potential and competitive edges, and further includes the mean resilience (Res_meant−1) for each one-digit CSIC industry (with manufacturing reported as a two-digit code) in the regression equation. The estimated coefficient for SSHKt−3 remained significantly positive, reaffirming that financial openness improves corporate resilience. In Column (4), we introduce the interaction term between the industry mean resilience and the core explanatory variable (SSHKt−3 × Res_meant−1) into Model (1) and continue with the regression. The positive, statistically significant coefficient indicates that resilience intensity increased from the 25th percentile (0.223) to the 75th percentile (0.401), representing a 4.71% improvement above the mean level after openness. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. The control variable coefficients broadly align with the prior literature.

Table 2.

The impact of capital market openness on corporate resilience.

4.1.2. The Impacts of Financial Openness on Five Sub-Dimensions of Corporate Resilience

This study further investigated the impact of financial openness on the five sub-dimensions of corporate resilience, exploring potential correlations between these abilities and financial openness. As shown in Table 3, the estimated coefficients for SSHKt−3 were statistically significant in the regressions for these five sub-dimensions, except for adaptability (Ada_capacity) and developmental capacity (Dev_capacity). Notably, the regression coefficients for innovation capability and absorptive capacity were significantly positive, whereas the coefficient for recovery capability was significantly negative. This is because recovery ability is a negative indicator. These results indicate that financial openness enhances corporate resilience in terms of absorptive capacity, innovation capability, and recovery ability, but has no significant impact on adaptability and developmental capacity. A plausible explanation for this finding is that, following financial openness, the influx of liquid capital, global investors, and advanced technology alleviates the financing constraints faced by domestic firms and improves corporate governance. This leads to global learning effects and technology spillovers [6], which positively impact firms’ absorptive, innovative, and recovery capacities.

Table 3.

The impact of capital market openness on the five sub-dimensions of corporate resilience.

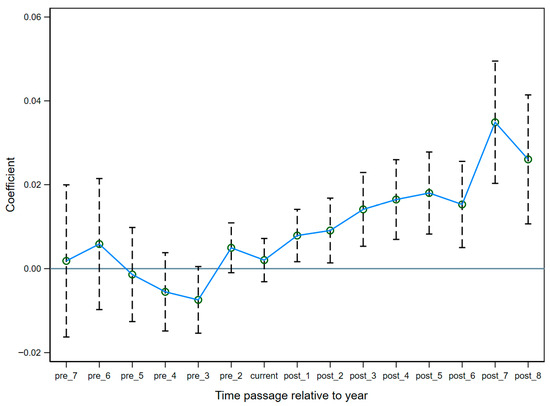

4.1.3. Parallel-Trend Tests

To test whether the change in the treatment group’s resilience before and after the SSHK policy was caused by the policy itself rather than a purely temporal effect, a parallel trend test was conducted to validate the untreated group serving as the comparison for the treatment group using the specified regression framework:

SSHKi,t are event-time dummies that equal 1 if firm i is t years relative to the SSHK inclusion year, and 0 otherwise. Where t = −7, −6, −5, −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, meaning seven years pre-implementation (pre_7–pre_1), the enactment year (current), and eight years after implementation (post_1–post_8). Other variables maintain the original in Equation (1). The period t = −1 is omitted as the benchmark to avoid multicollinearity. The coefficients βt for t < 0 should be statistically insignificant to support the parallel-trend assumption. The empirical results after deletion are displayed in Figure 3. The coefficient estimates for pre_7-pre_2 and current are statistically insignificant, indicating that the parallel trend test has passed. More importantly, the estimated coefficient for post_1 becomes statistically significant, and the coefficients for post_2 to post_8 are significantly positive at the 5% or 1% level, suggesting that corporate resilience increases following the opening. In brief, our findings indicate that a country’s financial openness enhances corporate resilience, not vice versa.

Figure 3.

Parallel-trend tests.

4.2. Robustness Checks

Drawing on previous research [6,15,16], we conducted robustness tests to verify the causal relationship between financial openness and corporate resilience.

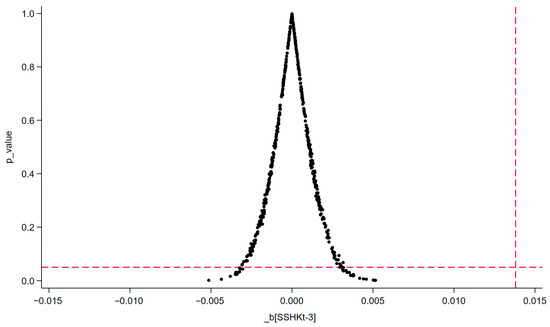

4.2.1. The Placebo Tests

We conducted a placebo test to rigorously assess the significance of financial openness on corporate resilience while controlling for the potential confounding effects of random factors. Following established methodologies, we randomly assigned 500 placebo treatment groups by replicating the distribution pattern of the core explanatory variable SSHKt−3 from the baseline regression. Using Model (1), we re-estimated these placebo groups and analyzed the distribution of coefficients and p-values. As shown in Figure 4, the mean regression coefficient for the placebo treatment groups was approximately zero, significantly smaller than the baseline coefficient of 0.0138, and followed a distribution close to normal. Furthermore, most p-values lay outside the conventional significance thresholds, with only a tiny fraction (indicated by the horizontal red dashed line) falling below the 5% significance level. This confirms that the observed resilience-enhancing effect is not spurious but is robustly attributable to financial openness.

Figure 4.

The placebo tests.

4.2.2. Replacing Explanatory Variables

The date of financial openness poses a challenge, as various factors can obscure its significance. A landmark event in the opening of China’s stock markets was the inclusion of Chinese A-shares in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index in June 2018. Building on existing research [20], we utilized the date of China’s SSHK scheme and conducted additional robustness checks based on the milestone of A-share inclusion in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. We constructed a binary variable (SSHK_MSCIt) in which, during the sample period, a value of 1 was assigned if a sampled firm is included among the MSCI index’s constituent stocks at year-end and 0 otherwise. There are differences in the status of the SSHK and the inclusion of China A-shares in the MSCI Index, which serve as proxy indicators for China’s financial openness. The SSHK is the “cause” and “path” of China’s financial openness, while the inclusion of China A-shares in the MSCI Index is the “result” and “symbol” recognized by the international community. Therefore, for outcome-oriented financial openness variables, we set their impact effect to arise in the same year as the official announcement. We then re-estimated Regression Equation (1). The results are shown in Table 4, Panel A. Column (1) demonstrates that the estimated coefficient for SSHK_MSCIt was significantly positive. Our analysis suggests that the alternative identification of the financial opening date is both robust and reliable.

Table 4.

Panel A: Replacing explanatory variables, controlling for omitted macroeconomic variables, and multidimensional fixed effects. Panel B: PSM-DID and model replacement.

4.2.3. Incorporating Macroeconomic Variables

Our empirical strategy includes additional macroeconomic controls omitted from the baseline specification. As financial openness is often correlated with local financial market development [4,6,8], we measured the provincial financial market depth using the ratio of aggregate bank loans and deposits to regional GDP (FD). To capture regional economic conditions, we followed prior research and employed log per capita GDP (PGDP) and five-year GDP growth volatility (VGDP) as proxies for development levels and macroeconomic risk [6]. The liberalization of stock markets is likely to occur alongside changes in local legal and regulatory environments [4]. Therefore, we included institutional quality in the baseline regression. We augmented the specification with institutional quality measures by constructing a composite index (Market) that captured regional market-intermediary development and the quality of the legal system. This was derived from the market intermediary development and legal environment index, as reported in the NERI Report on Marketization Index of China’s Provinces (e.g., Wang et al., 2021 [59]), a series of achievements from the research project led by the National Economic Research Institute. Additionally, we controlled for the average industry resilience in this context. Finally, the baseline specification incorporated industry and province-fixed effects to account for non-time-varying heterogeneity across sectors and regions.

The regression results in Table 4, Panel A, demonstrated persistently significant positive coefficients for SSHKt−3 across Columns (2) to (4) (p < 0.01). This robustness holds after accounting for critical omitted variables, mean industry resilience, and province and industry fixed effects, verifying the resilience-enhancing impact of financial openness. Additionally, the directions of these supplementary control variables typically aligned with prior research.

4.2.4. PSM-DID

This study employed propensity score matching to mitigate selection bias. We used nearest-neighbor (1:3) and kernel-matching techniques to reconstitute treatment–control pairs to enhance the robustness of causal inference. The regression results are presented in Table 4, Panel B, Columns (1) and (2), demonstrating that the estimated coefficients for SSHKt−3 remained significantly positive. This finding indicates that, even after addressing sample selection bias, the baseline regression conclusions remain valid.

4.2.5. Replacement Model

The structural characteristics of the dependent variable exhibited a pronounced left-skew, with a substantial mass concentrated in the left tail and a continuous distribution of positive values between 0 and 1. This study modified the regression model to employ a dual restrictions random effects panel Tobit model and a Clad model to re-evaluate the results. As shown in Table 4, Panel B, Columns (3) and (4), the estimated coefficients for SSHKt−3 were statistically significant at the 1% level, confirming the robustness of the baseline effects across alternative model specifications.

5. Further Analysis

5.1. Mediation Mechanism Analysis

Financial openness removes restrictions on cross-border capital flows and introduces international investors into domestic markets. This process leverages the governance and information effects provided by external actors, thereby enhancing firms’ dynamic adjustment capabilities and ultimately strengthening corporate resilience. Drawing on previous research [15], this study built Model (3) and Model (4) based on Model (1) to examine the mechanism through which financial openness empowers corporate resilience.

where Mi,t denotes the mediating variables, encompassing the proportion of foreign ownership (FO) and the quality of public information disclosure (DA). Specifically, FO shows the proportion of foreign shareholders in companies listed under the SSHK scheme, which partly indicates their level of involvement in corporate governance practices. In this study, the proportion of foreign ownership was measured by the shareholding ratio held by overseas investors through “Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited” among the top ten shareholders of the listed companies. The higher this indicator, the greater the involvement of foreign investors in the target company’s governance practices. DA refers to the quality of public information disclosure. Drawing on the approaches of Raman and Shahrur (2008) and Fan (2012) [61,62], this study measured the absolute value of discretionary accruals (DA) using the modified Jones model while considering firm performance and growth. The higher this indicator, the lower the quality of public information disclosure. Other variable settings remained consistent with model (1).

Table 5 reports the results of the mechanism analysis. Column (1) shows that the estimated coefficient of financial openness on foreign ownership was significantly positive, indicating that financial openness increases the proportion of foreign ownership and encourages foreign investors to participate in corporate governance. Column (2) shows that the estimated coefficient of foreign ownership on corporate resilience was significantly positive. As discussed in the previous theoretical discussion, foreign ownership participation improves corporate governance by strengthening internal checks and balances and reshaping the firm’s strategic resource boundaries. This influence is gradually internalized, forming a structural buffering capacity that contributes to the cultivation of corporate resilience. Column (3) shows that the estimated coefficient for financial openness was significantly negative, indicating that financial openness improves the quality of corporate information disclosure. Column (4) shows that the estimated coefficient of information disclosure quality on corporate resilience was significantly negative. According to information asymmetry theory, high-quality information disclosure can alleviate external financing constraints and provide resources to build corporate resilience. All of the above mediating variables passed the Bootstrap test. These results suggest that financial openness can enhance corporate resilience through two channels: introducing foreign ownership into governance and improving the quality of corporate information disclosure.

Table 5.

Mediating mechanism.

5.2. The Heterogeneity Analysis

5.2.1. The Moderating Effect of the Degree of Industry Competition

Financial openness, accompanied by increased industry competition, can effectively reduce the rate of resource mismatch and promote the growth of new firms [3,7]. Firms in highly competitive industries (with low Herfindahl indices) that face continuous survival pressure and demand for innovation are more likely to amplify the benefits of liberalization through good governance practices. Cross-border capital flows to high-productivity agents via information screening mechanisms [4]. Foreign ownership governance compels firms to develop agile supply chains [14]. Digital technology embeddedness boosts knowledge reorganization and the iteration of dynamic capabilities [27,63], enhancing firms’ adaptability and resilience in competitive industries. However, in low-competitive (higher Herfindahl index) industries, firms may use the policy dividend of financial openness to consolidate their market position rather than build resilience. The influx of foreign capital often leads to capital concentration within a limited number of large firms, rather than being distributed competitively across the industry to absorb economic shocks. This concentration, coupled with an overreliance on foreign financing, can further amplify the contagion effect of financial losses throughout the sector [12,19]. Particularly in adverse situations, the detrimental aggregate shock is further compounded in firms with monopolistic positions, such as the discount rate increases [64]. Thus, the degree of industry competition constitutes a structural constraint on the resilience-enabling effect of financial openness. While monopoly power tends to reinforce path dependence, a competitive ecology fosters dynamic adaptation. These opposing forces significantly shape the pathway through which financial openness builds resilience.

Drawing on existing research methodologies [15], this study incorporated the interaction between the degree of industry competition and the key explanatory variable into the baseline regression model (1) for re-estimation. Table 6 reports the results of the hierarchical regression analysis. Column (1) reveals a significantly negative coefficient for the interaction term (SSHKt−3 × HHIt−1), suggesting that a higher industry concentration weakens the resilience-enhancing impact of financial openness.

Table 6.

Moderating mechanism.

5.2.2. The Moderating Effect of External Financing Dependence

The heterogeneity of firms’ external financing dependence reflects the sensitivity and adaptability of their capital structures to cross-border capital flows. It may affect the efficiency with which firms utilize financial openness dividends to cope with external shocks. According to prior research [61], firms with high external financing dependence are more susceptible to local credit rationing and institutional frictions, given the capital-intensive nature of technological innovation and supply chain maintenance. This structural vulnerability tends to form a mechanism for shock transmission during cyclical fluctuations in domestic capital markets [65]. Notably, financial openness reshapes the logic of corporate resilience generation through dual paths. On the one hand, international capital inflows bypass traditional credit quota restrictions, injecting scarce capital into financing-poor firms [3]. On the other hand, the participation of foreign shareholders through the dual “exit-appeal” mechanism and strengthened disclosure requirements optimizes corporate governance practices [57]. As high-financial-dependence firms face tighter initial constraints, they derive greater benefits from increased market transparency than low-financial-dependence firms [66]. This enables capital elements to be precisely injected into the weak links of corporate resilience. In the short-term, it enhances liquidity buffers, thereby reducing the risk of operational disruption caused by cash flow volatility. In the long-term, it becomes an endogenous driver of sustained investment in technological innovation, supply chain digitalization, and structural restructuring. Consequently, the resilience-enhancing effect of high-financial-dependency firms in an open capital market environment is greater than that of low-financial-dependency firms.

Following previous research [29,66], this study measured firms’ dependence on external financing as the gap between (Sizet − Sizet−1) and ROEt/(1 − ROEt). It extends Model (1) by incorporating the interaction term (SSHKt−3 × EFDt−1), which captures the moderating role of external financing dependence in this relationship. The empirical outcomes are reported in Table 6, Column (2). The positive sign of the interaction effect (SSHKt−3 × EFDt−1) was statistically significant at the 10% level. This indicates that high external financing dependence amplifies the resilience gains from financial openness compared to low-dependence firms. Therefore, enterprises that rely more on external financing to meet their investment needs experience faster improvement in resilience following financial openness.

6. Analysis of Economic Consequences

Our findings demonstrate that financial openness enhances corporate resilience. However, it remains unclear whether the previously documented positive effects of financial openness on economic growth operate through resilience mechanisms. Prior research has shown that financial openness promotes green innovation without improving firm value [15]. Suppose the resilience enhancement we identify reflects post-openness productivity gains. In that case, we hypothesize that openness boosts total factor productivity (TFP) through corporate resilience channels, with more potent and long-term effects.

To test this conjecture, we first examined the impact of openness on TFP using four estimation methods: Olley–Pakes’s production method (OP), Levinsohn–Petrin’s (LP) production function, OLS, and GMM. The estimated results are demonstrated in Table 7, Panel A. The first four columns indicate that these interaction terms (SSHKt−3 × Rest−1) were significantly positive. This suggests that corporate resilience positively moderates the relationship between financial openness and TFP. The negative coefficient of SSHKt−3 indicates that, without accounting for resilience conditions or time factors, financial openness exerts a negative impact on corporate TFP. This finding aligns with prior research. Financial openness leads to short-term market volatility [11] and increases firms’ exposure to systemic risk [12], which may potentially harm their TFP, especially for low-resilience firms. However, fostering corporate resilience is not merely an outcome but a critical condition for translating financial integration into sustainable productivity gains. Furthermore, we distinguish between temporary (SSHK_temp) and permanent (SSHK_perm) growth effects. Following Moshirian et al. (2021) [6], we define the first three years after capital market openness as representing its temporary effects, while the period beyond three years is categorized as indicative of its permanent effect. The results, presented in Table 7, Panel B, Columns (1) to (4), reveal that the coefficient of the interaction term for temporary differences and corporate resilience (SSHK_temp × Rest−1) was not significant. Still, the coefficient for the interaction term of permanent differences and corporate resilience (SSHK_perm × Rest−1) was positive at the 5% level. This finding suggests that the positive moderating effect of resilience is permanent rather than temporary. In other words, enhancing firm resilience continuously mitigates the negative impact of financial openness on TFP and yields a positive long-term net benefit.

Table 7.

Panel A: Capital market openness, corporate resilience and TFP. Panel B: Difference between temporary and permanent effects.

One explanation for these findings is that financial openness has both non-systemic risk diversification and systemic risk contagion effects [6,12,30]. The development of financial openness may limit firms’ TFP due to increased systemic risk, especially in the short-term [11,12]. Most firms’ resilience in the sample is only slightly above the average level, remaining well below the “critical threshold” needed to shift the effect of openness on TFP from negative to positive. Notably, more resilient firms can enhance their dynamic capacities and transform strategic resources into productivity gains after financial openness. Resilience-driven risk-hedging systems, such as diversified financing portfolios and flexible production networks, can mitigate volatility shocks in an open environment, enhance recovery capabilities, and boost TFP in the long-term. Additionally, financial openness can encourage more innovative firms to increase R&D investments and patent outputs [6]. For instance, in China’s photovoltaic industry, low-resilience firms became trapped in low-end segments; however, high-resilience firms achieved significant TFP improvements through a “technology import–digestion–innovation” pathway, such as Longi Green Energy Technology Co., Ltd. (Xi’an, China). These findings highlight the need to couple financial openness with resilient cultivation to prevent total TFP erosion. Institutional coordination that facilitates the evolution of organizational resilience from defensive redundancy to adaptive capacity can fully unlock the productivity dividends of capital market openness.

7. Conclusions

Financial openness has two features: risk diversification and contagion effects [19,67]. These features affect macroeconomic stability, corporate performance, and societal welfare [68]. To address this duality, economic systems must shift from traditional risk management to resilience-focused governance. Consequently, this study examined the impact of financial openness on corporate resilience using the staggered implementation of the Shanghai-Hong Kong and Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SSHK) programs in China as quasi-natural experiments. Using dynamic DID models on Chinese A-share listed companies from 2009 to 2022, we found that financial openness generates resilient gains, and that the degree of industry competition and external financing dependence moderate the main effect. We identified two underlying mechanisms that explain how financial openness positively affects corporate resilience: introducing foreign ownership and improving the quality of corporate information disclosure. Analysis of the economic consequences indicates that fostering corporate resilience is not merely an outcome but a critical condition for translating financial integration into sustainable productivity gains, though this transformation requires time. Our findings offer insights for global market participants that enhancing firm resilience is a critical prerequisite for unlocking the benefits of financial openness.

While we elucidate that financial openness seems to have a beneficial causative impact on corporate resilience, we address two significant caveats when interpreting or generalizing our findings. First, although this choice aligns with the need to reflect the institutional characteristics of emerging economies, our study’s sample is restricted to China’s A-share market. This may limit the external validity of the conclusions for developed markets and transitional economies. Future research could extend cross-national comparisons (e.g., OECD or BRICS economies). Second, our measurement framework for corporate resilience—which encompasses capacities to adapt, absorb, innovate, recover, and develop in response to external shocks—does not explicitly isolate a digitization dimension. In an era marked by rapid technological advances, such as AI-driven risk management and blockchain-enabled supply chain transparency, this omission may lead existing frameworks to undervalue the strategic role of openness policies in strengthening firms’ digital capabilities. Developing a universally applicable digital resilience metric is methodologically challenging as digital resilience varies significantly across sectors and resists oversimplification. Future research could address this by incorporating proxy measures—such as corporate digital investment intensity or algorithmic governance maturity—into a dynamic model to trace the causal pathways between financial openness and the development of corporate digital resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.P.; methodology, X.P. and J.H.; validation, X.P. and X.P.; formal analysis, X.P., J.H. and Y.W.; resources, X.P. and J.H.; data curation, X.P. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.P. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, X.P., J.H. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Science and Technology Fund Project of the Gansu Provincial Basic Research Plan of China (grant number 24JRRA542).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variable definition.

Table A1.

Variable definition.

| Variables | Definitions | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Res | We employed entropy weighting that assigns objective weights to these five dimensions based on their informational value to compute a composite corporate resilience index in year t. Res = 0.1235 Ada_capacity + 0.2073 Inn_capacity + 0.5106 Abs_capacity + 0.0743 Res_capacity + 0.0843 Dev_capacity | CSMAR database |

| Ada_capacity | The coefficient of variation in annual R&D, capital, and advertising expenditures, in year t, where lower coefficients indicate stronger adaptability. | CSMAR database |

| Inn_capacity | Aggregating standardized metrics of R&D expenditure, R&D personnel intensity, and invention patent counts, in year t, where higher values indicate greater innovation capability. | CSMAR database |

| Abs_capacity | The ratio of annual R&D expenditures to total revenue in year t, where higher ratios indicate a greater absorptive capacity. | CSMAR database |

| Res_capacity | The three-year industry-adjusted standard deviation of return on assets (ROA) in year t, with lower variability indicating stronger recovery capacity. | CSMAR database |

| Dev_capacity | It is defined as financial flexibility, i.e., the sum of cash flexibility and liability flexibility, to measure development capability in year t, with the larger value indicating stronger development capability. Where, cash flexibility = enterprise cash ratio—industry average cash ratio, and liability flexibility = max (0, industry average debt ratio—enterprise debt ratio). | CSMAR database |

| SSHK | A binary indicator that equals one if the firm is included in the SSHK scheme at the end of each year and zero otherwise, observed at t − 3. | https://www.hkex.com.hk (accessed on 3 December 2025). |

| Size | Natural logarithm of the company size, observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| Lev | Total liabilities divided by total assets, observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| Roa | Net profit divided by average total assets, observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| Sales | Natural logarithm of the company’s operating revenue plus one, observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| MB | The company’s book value divided by its market value, observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| Listage | Natural logarithm of the company’s listing age plus one, observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| Board | The number of board members observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| Cash | The ratio of the sum of monetary funds and trading financial assets to total assets, observed at t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| Res_mean | The average resilience of each one-digit CSIC industry (with manufacturing reported as a two-digit code) within industries in year t − 1. | CSMAR database |

| SSHKMSCI | A binary indicator that equals 1 if the firm is included in the MSCI China index at year-end t and 0 otherwise. | Manual collect |

| FD | The banking sector’s credit-to-GDP ratio in year t − 1. | CNBS |

| PGDP | The log-transformed per-capita GDP in year t − 1. | CNBS |

| VGDP | The five-year rolling standard deviations of per capita GDP growth in year t. | CNBS |

| Market | Institutional quality through market intermediary development and legal environment metrics in t−1, following Wang et al. (2021) [59]. | Manual collect |

| DA | Drawing on the approaches of Raman and Shahrur (2008) [61] and Fan (2012) [62], this study measures the absolute value of discretionary accruals using the modified Jones model while considering firm performance and growth. | Manual collect |

| FO | Foreign ownership, measured as the percentage of shares held by foreign investors in the eligible companies through Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Ltd. (Hong Kong, China), following the launch of the programs. | WIND database |

| HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, summing the squared market shares of firms’ core business revenues in their respective industries. | CSMAR database |

| EFD | External financing dependency, measured as the gap between observed corporate growth (St − St−1) and realized endogenous growth capacity (Roet/(1 − Roet)) following Chen et al. (2023) [29], where S is the total asset size and Roe is the return on equity. | CSMAR database |

| TFP_OP | Estimation of total factor productivity uses the Olley–Pakes’s production method (OP). | CSMAR database |

| TFP_LP | Estimation of total factor productivity uses the semiparametric methodology of Levinsohn and Petrin (LP). | CSMAR database |

| TFP_OLS | Estimation of total factor productivity uses the OLS estimation methodology. | CSMAR database |

| TFP_GMM | Estimation of total factor productivity uses the GMM estimation methodology. | CSMAR database |

Table A2.

Causal effects of the explained variables after 1–7 periods of lagging.

Table A2.

Causal effects of the explained variables after 1–7 periods of lagging.

| Variables | Res | Res | Res | Res | Res | Res | Res |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| L1_SSHK | 0.0137 *** | ||||||

| (0.0044) | |||||||

| L2_SSHK | 0.0135 *** | ||||||

| (0.0043) | |||||||

| L3_SSHK | 0.0138 *** | ||||||

| (0.0042) | |||||||

| L4_SSHK | 0.0129 *** | ||||||

| (0.0041) | |||||||

| L5_SSHK | 0.0111 *** | ||||||

| (0.0041) | |||||||

| L6_SSHK | 0.0111 ** | ||||||

| (0.0043) | |||||||

| L7_SSHK | 0.0171 ** | ||||||

| (0.0067) | |||||||

| Sizet−1 | 0.0403 *** | 0.0405 *** | 0.0405 *** | 0.0406 *** | 0.0409 *** | 0.0410 *** | 0.0411 *** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0051) | (0.0051) | (0.0051) | (0.0051) | (0.0051) | (0.0051) | |

| Levt−1 | −0.0800 *** | −0.0800 *** | −0.0799 *** | −0.0798 *** | −0.0798 *** | −0.0797 *** | −0.0795 *** |

| (0.0121) | (0.0121) | (0.0121) | (0.0121) | (0.0121) | (0.0121) | (0.0122) | |

| Roat−1 | −0.0186 | −0.0183 | −0.0185 | −0.0194 | −0.0208 | −0.0212 | −0.0222 |

| (0.0181) | (0.0181) | (0.0181) | (0.0181) | (0.0181) | (0.0181) | (0.0181) | |

| Salest−1 | −0.0201 *** | −0.0201 *** | −0.0200 *** | −0.0200 *** | −0.0200 *** | −0.0200 *** | −0.0200 *** |

| (0.0040) | (0.0039) | (0.0040) | (0.0040) | (0.0040) | (0.0040) | (0.0040) | |

| MBt−1 | −0.0359 *** | −0.0356 *** | −0.0350 *** | −0.0345 *** | −0.0347 *** | −0.0347 *** | −0.0345 *** |

| (0.0086) | (0.0086) | (0.0086) | (0.0086) | (0.0086) | (0.0086) | (0.0086) | |

| Listaget−1 | −0.0174 *** | −0.0172 *** | −0.0171 *** | −0.0172 *** | −0.0175 *** | −0.0176 *** | −0.0174 *** |

| (0.0044) | (0.0044) | (0.0044) | (0.0044) | (0.0044) | (0.0044) | (0.0044) | |

| Boardt−1 | 0.0033 *** | 0.0033 *** | 0.0034 *** | 0.0033 *** | 0.0033 *** | 0.0033 *** | 0.0033 *** |

| (0.0011) | (0.0011) | (0.0011) | (0.0011) | (0.0011) | (0.0011) | (0.0011) | |

| Casht−1 | 0.0221 * | 0.0219 * | 0.0218 * | 0.0215 * | 0.0212 * | 0.0210 * | 0.0210 * |

| (0.0116) | (0.0116) | (0.0116) | (0.0116) | (0.0116) | (0.0117) | (0.0117) | |

| Constant | −0.0789 | −0.0833 | −0.0857 | −0.0882 | −0.0911 | −0.0934 | −0.0966 |

| (0.0698) | (0.0697) | (0.0698) | (0.0699) | (0.0701) | (0.0702) | (0.0703) | |

| Firm FE & Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 15,762 | 15,762 | 15,762 | 15,762 | 15,762 | 15,762 | 15,762 |

| R2 | 0.725 | 0.725 | 0.725 | 0.725 | 0.725 | 0.724 | 0.725 |

***, ** and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

References

- Henry, P.B. Capital-Account Liberalization, the Cost of Capital, and Economic Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitton, T. Stock Market Liberalization and Operating Performance at the Firm Level. J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 81, 625–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Yuan, K. On the Growth Effect of Stock Market Liberalizations. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 4715–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, G.; Harvey, C.R.; Lundblad, C. Financial Openness and Productivity. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrain, M.; Stumpner, S. Capital Account Liberalization and Aggregate Productivity: The Role of Firm Capital Allocation. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1825–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirian, F.; Tian, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W. Stock Market Liberalization and Innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 139, 985–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, N.; Matray, A. Misallocation and Capital Market Integration: Evidence from India. Econometrica 2023, 91, 67–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, P.B. Stock Market Liberalization, Economic Reform, and Emerging Market Equity Prices. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 529–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, G.; Harvey, C.R. Foreign Speculators and Emerging Equity Markets. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 565–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Mohapatra, S. Income Inequality: The Aftermath of Stock Market Liberalization in Emerging Markets. J. Empir. Financ. 2003, 10, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, G.L.; Schmukler, S.L. Short-Run Pain, Long-Run Gain: Financial Liberalization and Stock Market Cycles. Rev. Financ. 2007, 12, 253–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Ge, X.; Si, D. Capital Market Liberalization and Systemic Risk of Non-Financial Firms: Evidence from Chinese Stock Connect Scheme. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 82, 102190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J.; Guenther, E. Organizational Resilience: A Valuable Construct for Management Research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, R.E.; Dwyer, S.M.; Koch, H. Upgrading Adaptation: How Digital Transformation Promotes Organizational Resilience. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2024, 18, 128–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y. Capital Market Opening and Green Innovation—Evidence from Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect and the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect. Energy Econ. 2022, 111, 106048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.-F.; Niu, P.; Wang, J.-Z.; Liu, J. Capital Market Liberalization and Green Innovation for Sustainability: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 75, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Han, L.; Yang, Q. Capital Market Liberalization and Firms’ OFDI Performance: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 59, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Erel, I.; Ferreira, M.; Matos, P. Does Governance Travel around the World? Evidence from Institutional Investors. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 100, 154–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Ozdaglar, A.; Tahbaz-Salehi, A. Systemic Risk and Stability in Financial Networks. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 564–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, W.; Zheng, S. Capital Market Opening and Share Repurchases: Evidence from China’s Listed Companies Absorbed in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 66, 105722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rojas, R.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; García-Morales, V.J. Social Media Use, Corporate Entrepreneurship and Organizational Resilience: A Recipe for SMEs Success in a Post-Covid Scenario. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 190, 122421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, S.; Nguyen, L.T. Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Resilience to COVID-19 Crisis: An Empirical Study of Chinese Firms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, B.; McDowell, W.C. The Impact of Digital Corporate Social Responsibility on Social Entrepreneurship and Organizational Resilience. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 2621–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, G.; Bendinelli, E.; Torluccio, G. COVID-19, ESG Investing, and the Resilience of More Sustainable Stocks: Evidence from European Firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 602–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, J. Does “Going International” Enhance Corporate Resilience in the Era of VUCA? Evidence from Chinese a-Share Listed Firms. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boh, W.; Constantinides, P.; Padmanabhan, B.; Viswanathan, S. Building Digital Resilience against Major Shocks. MIS Q. 2023, 47, 343–360. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti, M. Financial Liberalization and Banking Crises: The Role of Capital Inflows and Lack of Transparency. J. Financ. intermed. 2007, 16, 32–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Ni, X. Financial Market Opening and Corporate Tax Avoidance: Evidence from Staggered Quasi-Natural Experiments. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 54, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, D. Capital Market Openness and Bank Credit Risk: Evidence from Listed Commercial Banks. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 63, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Levine, R.; Lin, C.; Xie, W. Corporate Immunity to the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 141, 802–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesJardine, M.; Bansal, P.; Yang, Y. Bouncing Back: Building Resilience Through Social and Environmental Practices in the Context of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florez-Jimenez, M.P.; Lleo, A.; Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Muñoz-Villamizar, A.F. Corporate Sustainability, Organizational Resilience, and Corporate Purpose: A Review of the Academic Traditions Connecting Them. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2025, 19, 67–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, T.; Atkova, I.; Gabrielsson, P. Business Modeling under Adversity: Resilience in International Firms. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2023, 17, 802–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Dong, S.; Zhou, R. The Impact of Digitalization on Corporate Resilience. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 97, 103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajko, M.; Boone, C.; Buyl, T. CEO Greed, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Organizational Resilience to Systemic Shocks. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 957–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Su, H.; Chen, L. Does Environmental Concern Drive Financial Assets? Evidence from China. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2025, 25, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yeung, A.C.L.; Han, Z.; Huo, B. The Effect of Customer and Supplier Concentrations on Firm Resilience during the COVID–19 Pandemic: Resource Dependence and Power Balancing. J. Oper. Manag. 2023, 69, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.; Küçükşahin, Y.; Çitil, M. Impact of Geopolitical Risk on Firm Financial Fragility: International Evidence from Listed Companies. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2025, 25, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Xie, G. Corporate Resilience to the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Digital Financ. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2022, 74, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.R.; Hasan, M.M.; Abadi, N. Do Intangible Assets Provide Corporate Resilience? New Evidence from Infectious Disease Pandemics. Econ. Model. 2022, 110, 105806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Hua, X.; Wang, Q. Corporate Culture and Firm Resilience in China: Evidence from the Sino-US Trade War. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 79, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Xue, Z. The Impact of Government Subsidies on Corporate Resilience: Evidence from the COVID-19 Shock. Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 4199–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzei, O.; Abdelnour, S. Another Day, Another Dollar: Enterprise Resilience under Terrorism in Developing Countries. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 804–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyl, T.; Boone, C.; Wade, J.B. CEO Narcissism, Risk-Taking, and Resilience: An Empirical Analysis in U.S. Commercial Banks. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1372–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Augusto, M. Attention to Social Issues and CEO Duality as Enablers of Resilience to Exogenous Shocks in the Tourism Industry. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.; Coviello, N.; Rouziou, M. Weathering a Crisis: A Multi-Level Analysis of Resilience in Young Ventures. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2023, 47, 864–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]