Integrating Skycourts into Multi-Story Buildings for Enhancing Environmental Performance: A Case Study of a Residential Building in a Hot-Humid Climate

Abstract

1. Introduction

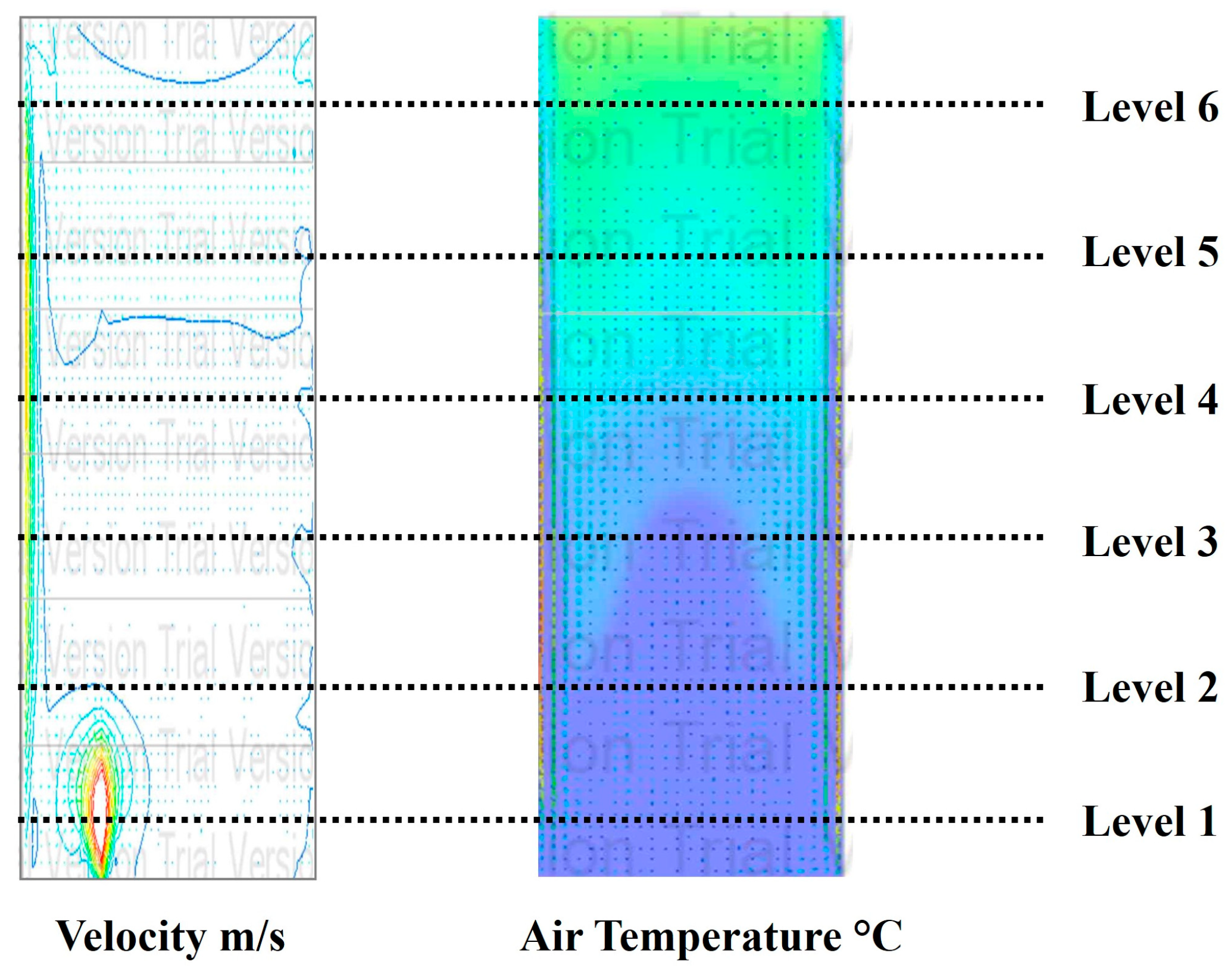

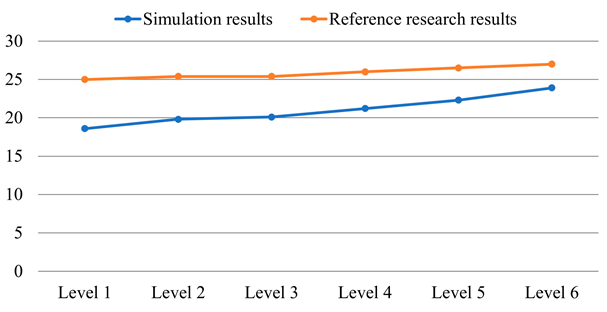

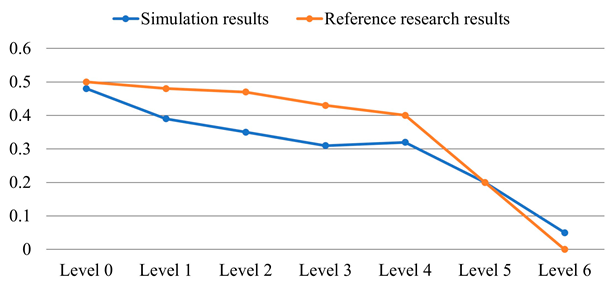

2. Verification Study

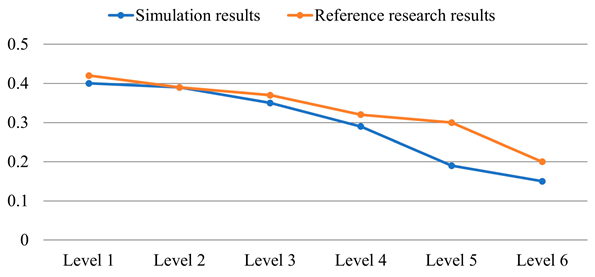

2.1. Verification Reference Case

2.2. Numerical Model

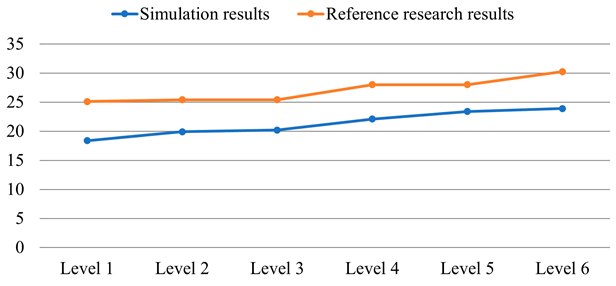

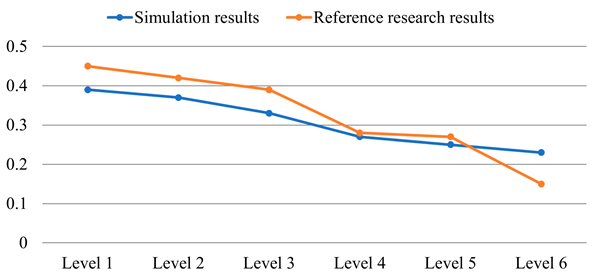

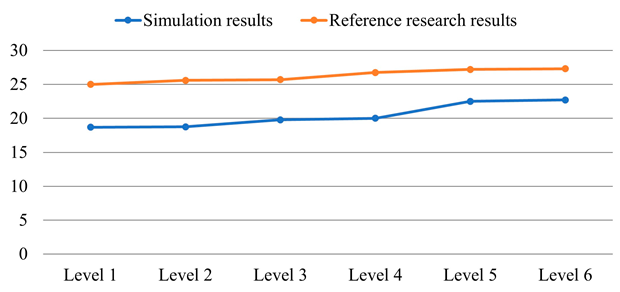

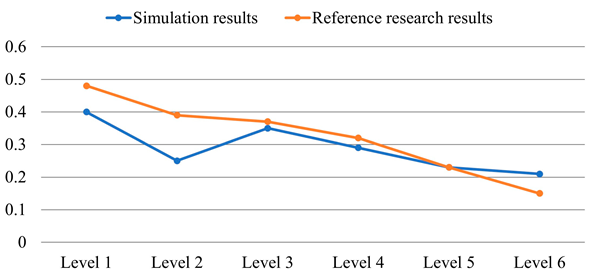

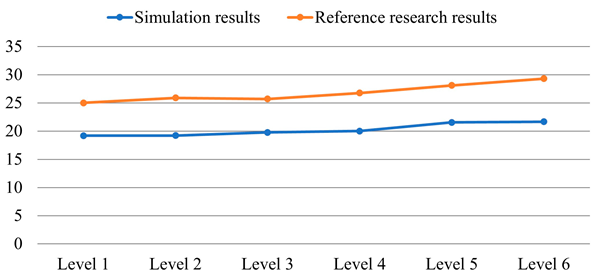

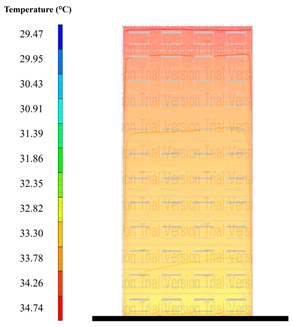

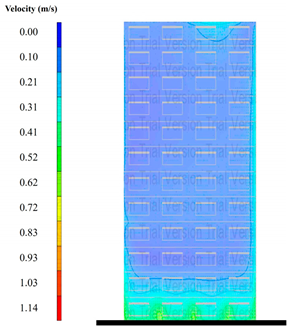

2.3. Verification Results Analysis

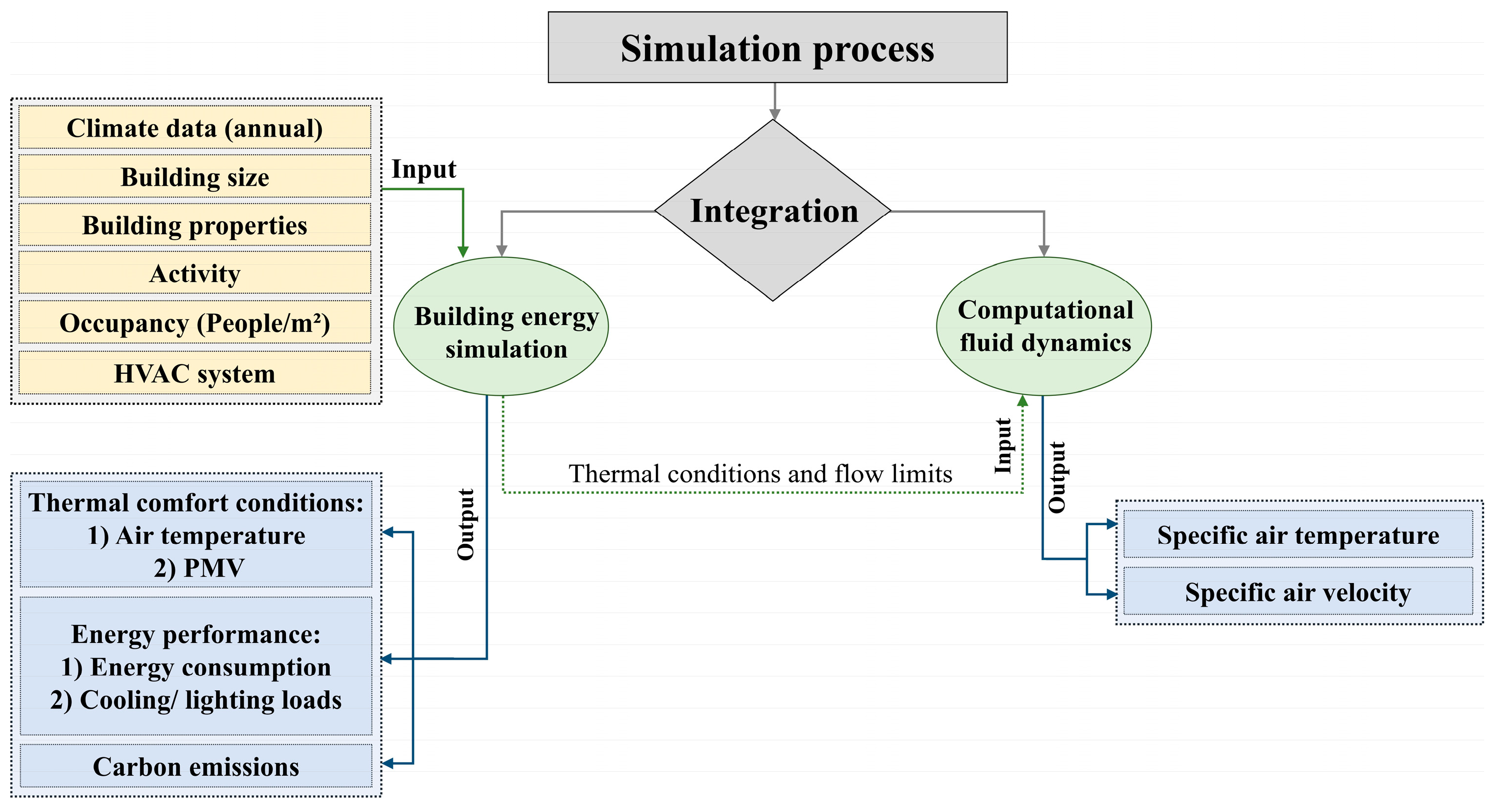

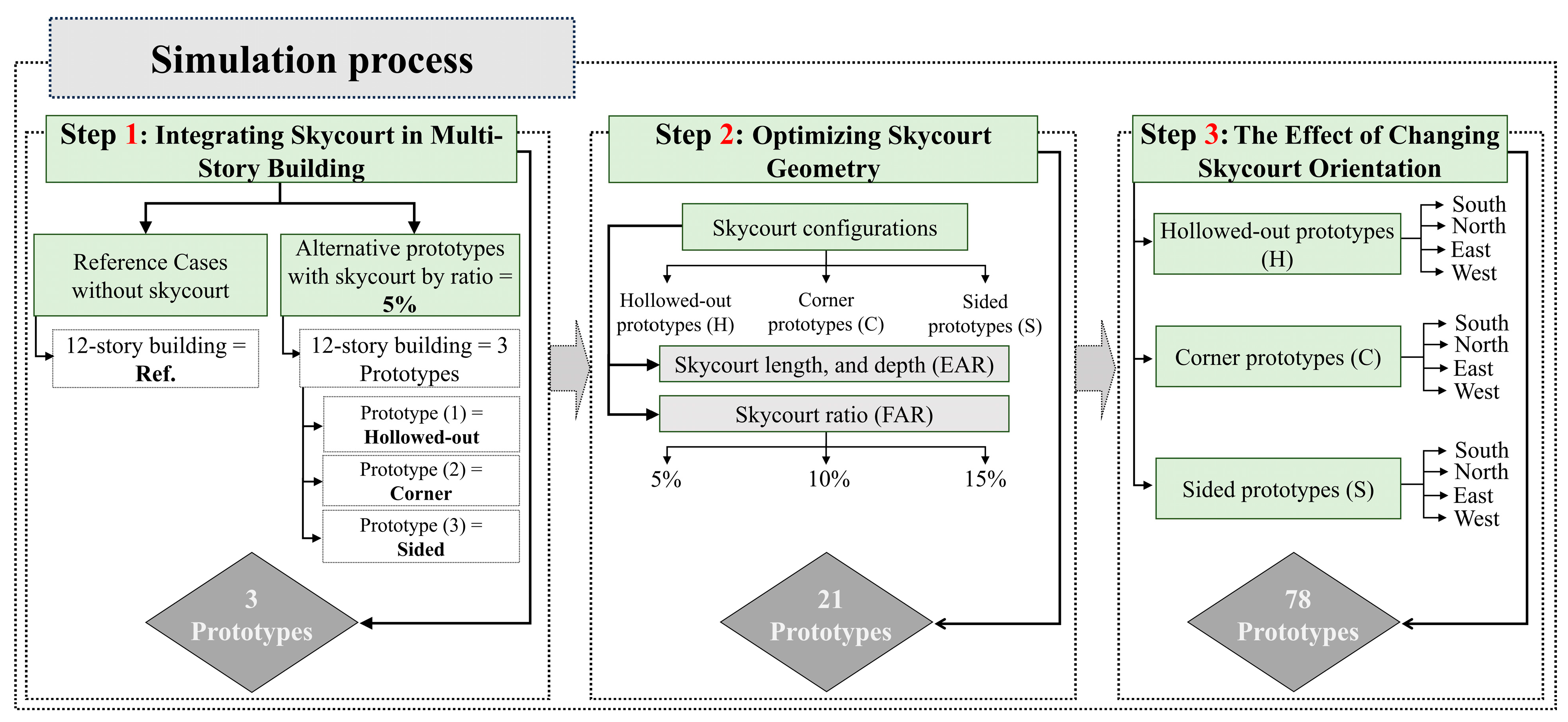

3. Simulation Process

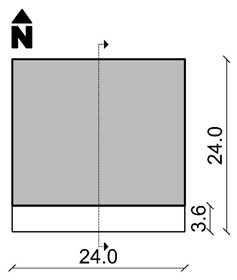

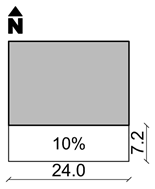

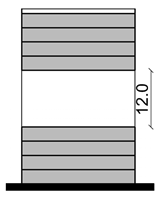

3.1. Case Study: Residential Building in Port Said

3.2. Study Area Climate

3.3. Proposed Building Prototypes

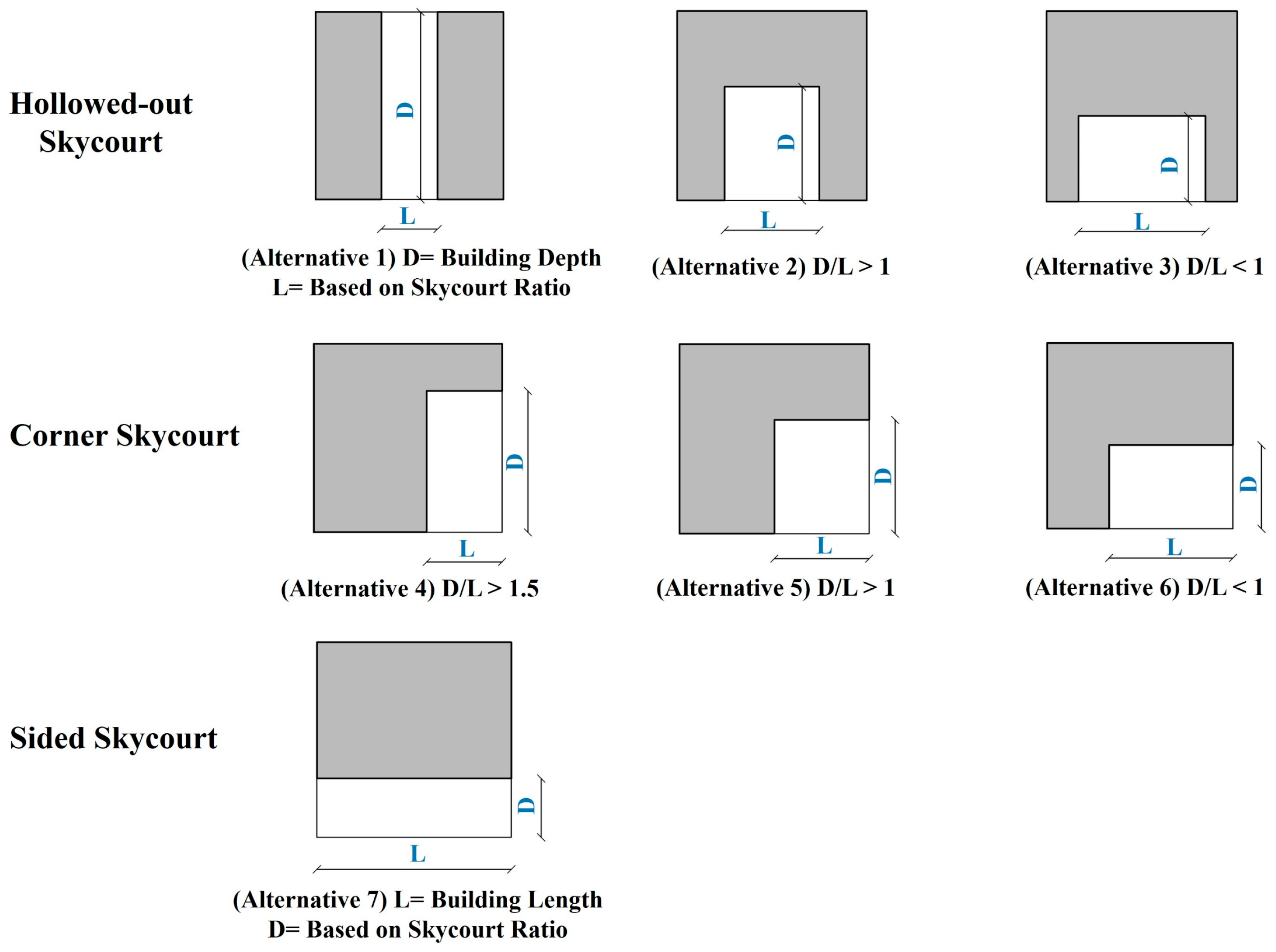

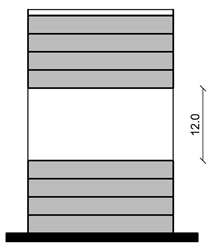

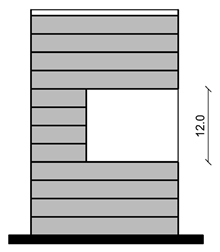

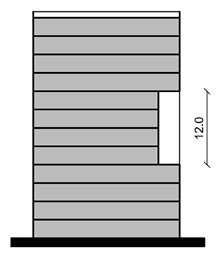

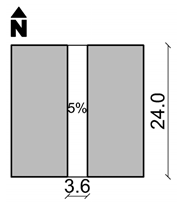

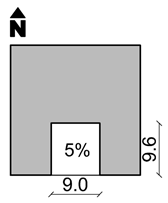

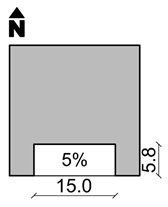

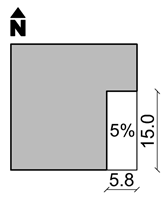

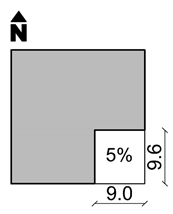

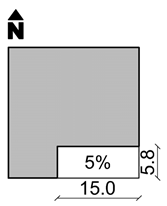

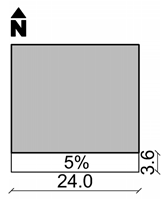

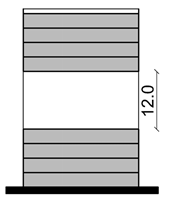

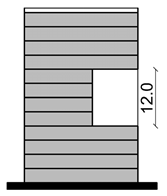

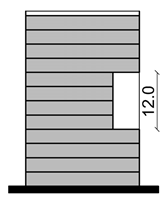

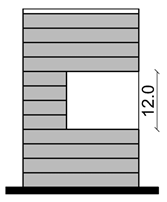

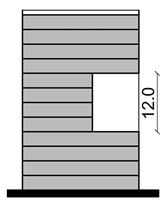

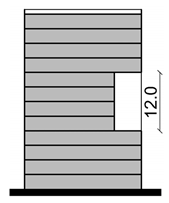

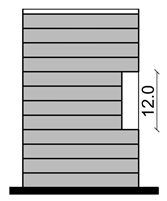

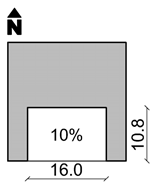

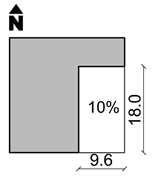

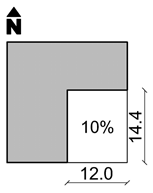

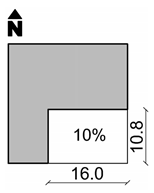

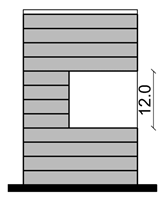

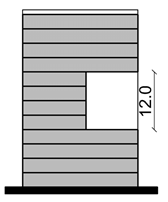

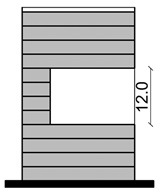

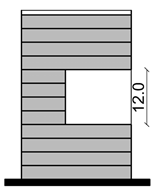

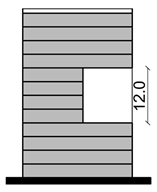

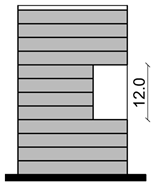

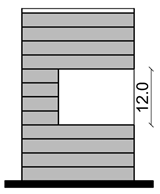

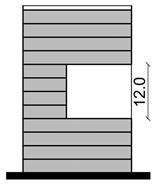

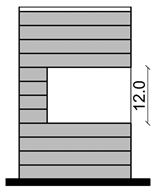

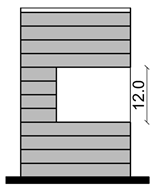

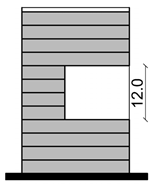

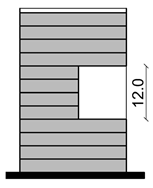

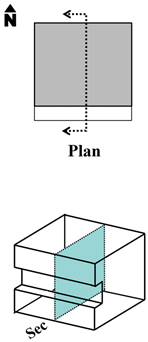

3.3.1. Step One: Integrating a Skycourt in a Multi-Story Building

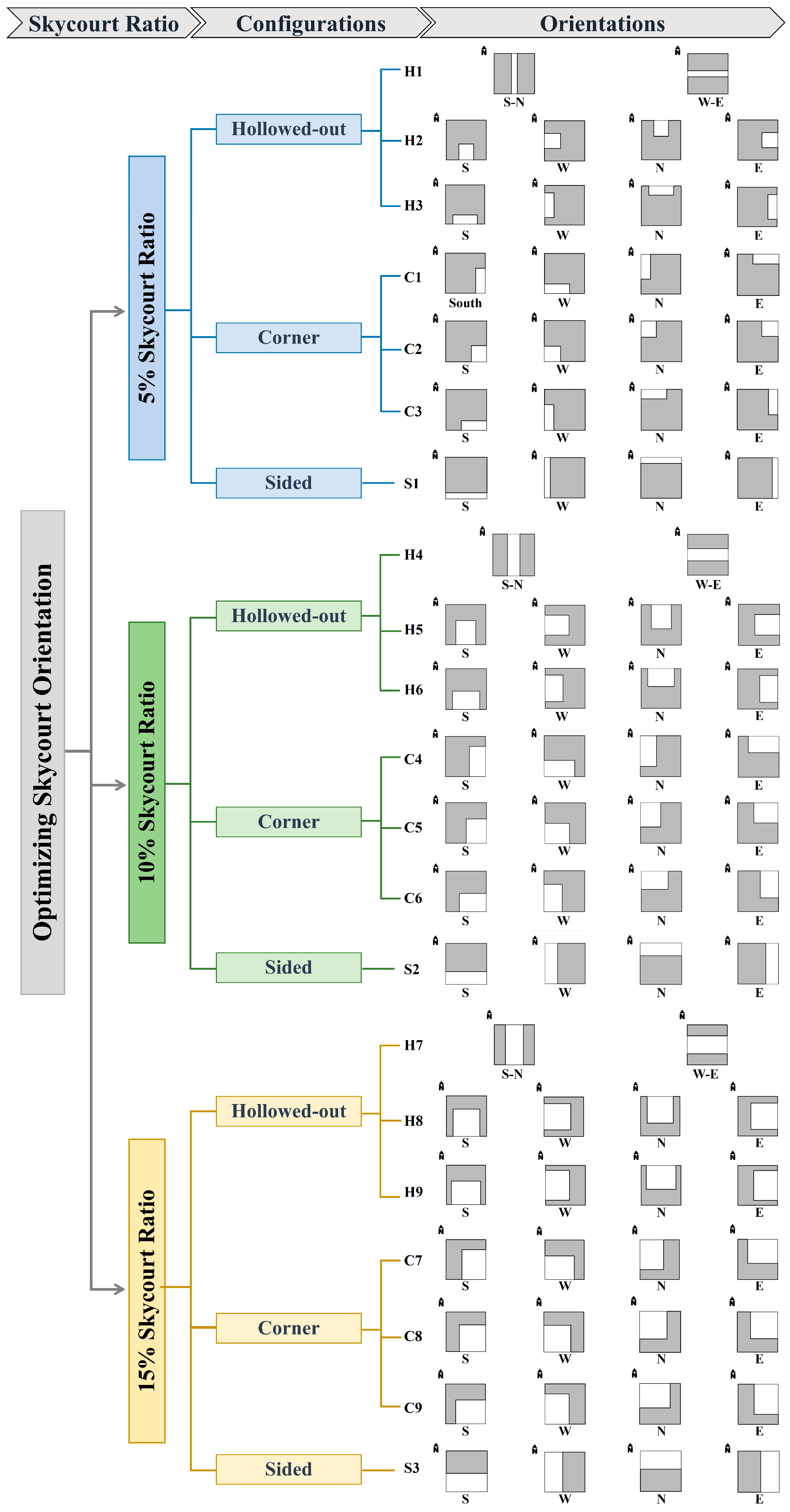

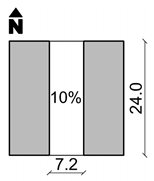

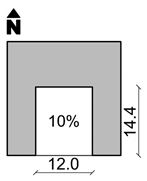

3.3.2. Step Two: Optimizing Skycourt Geometry

3.3.3. Step Three: Optimizing Skycourt Orientation

3.4. Computational Settings

4. Analysis of Results

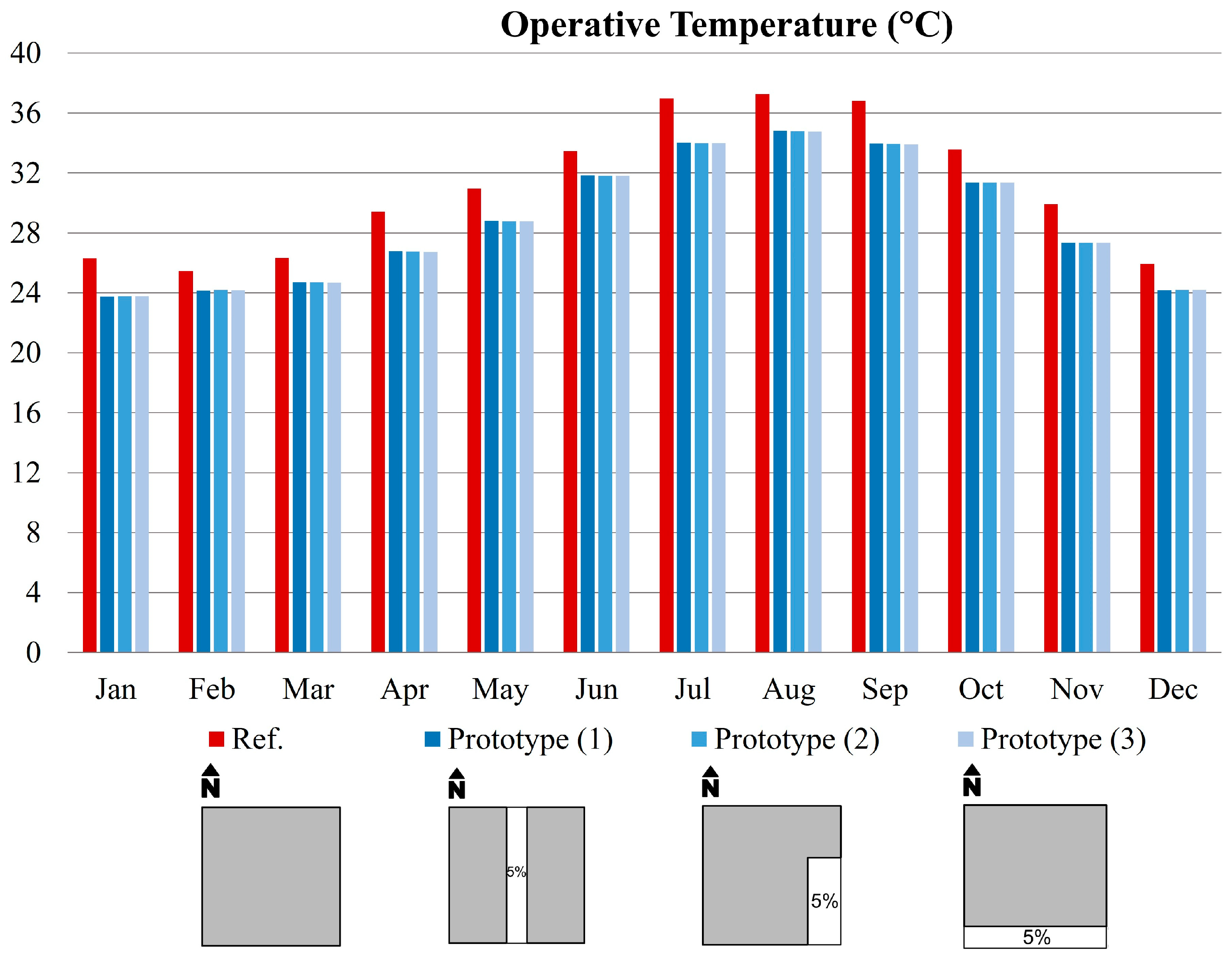

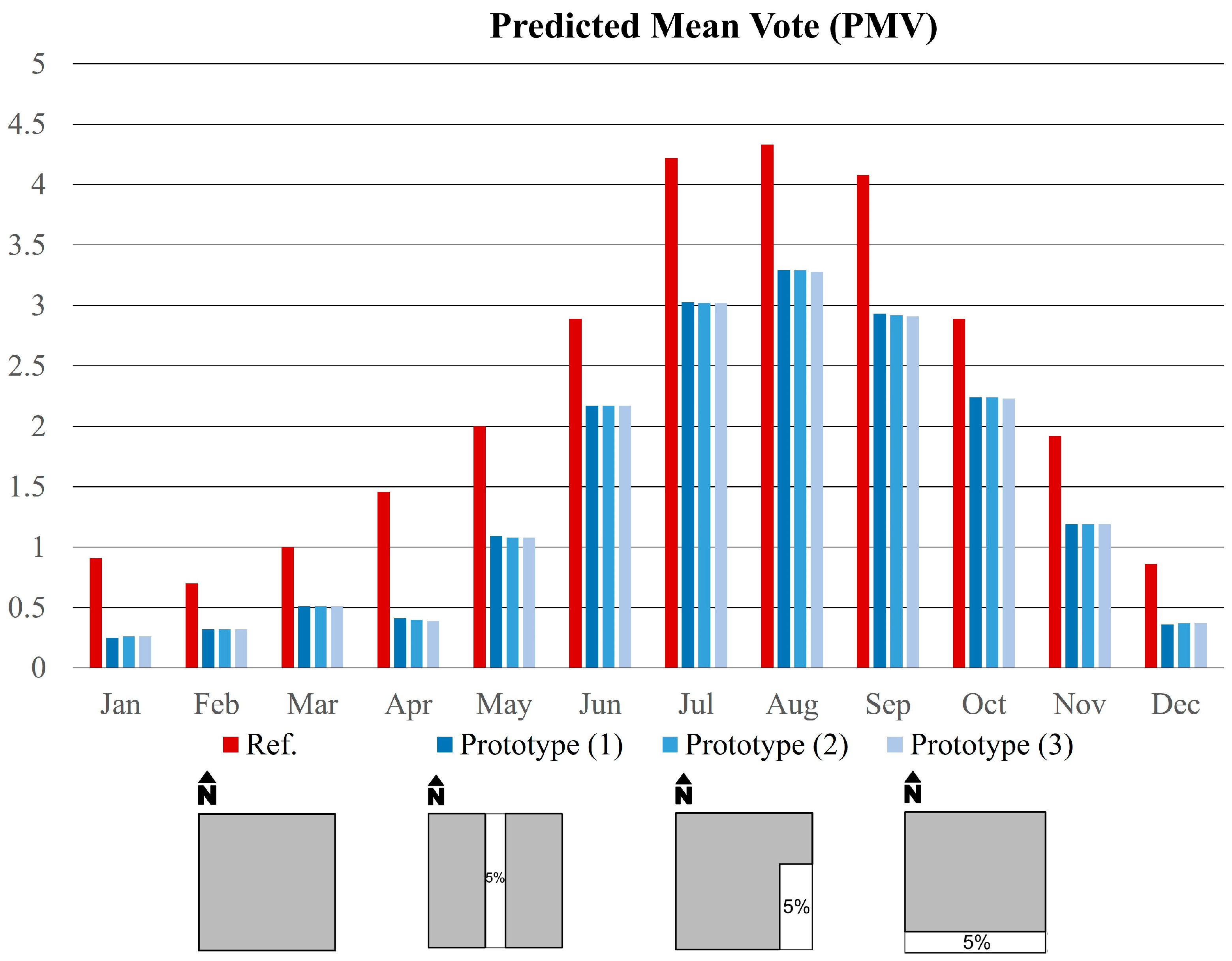

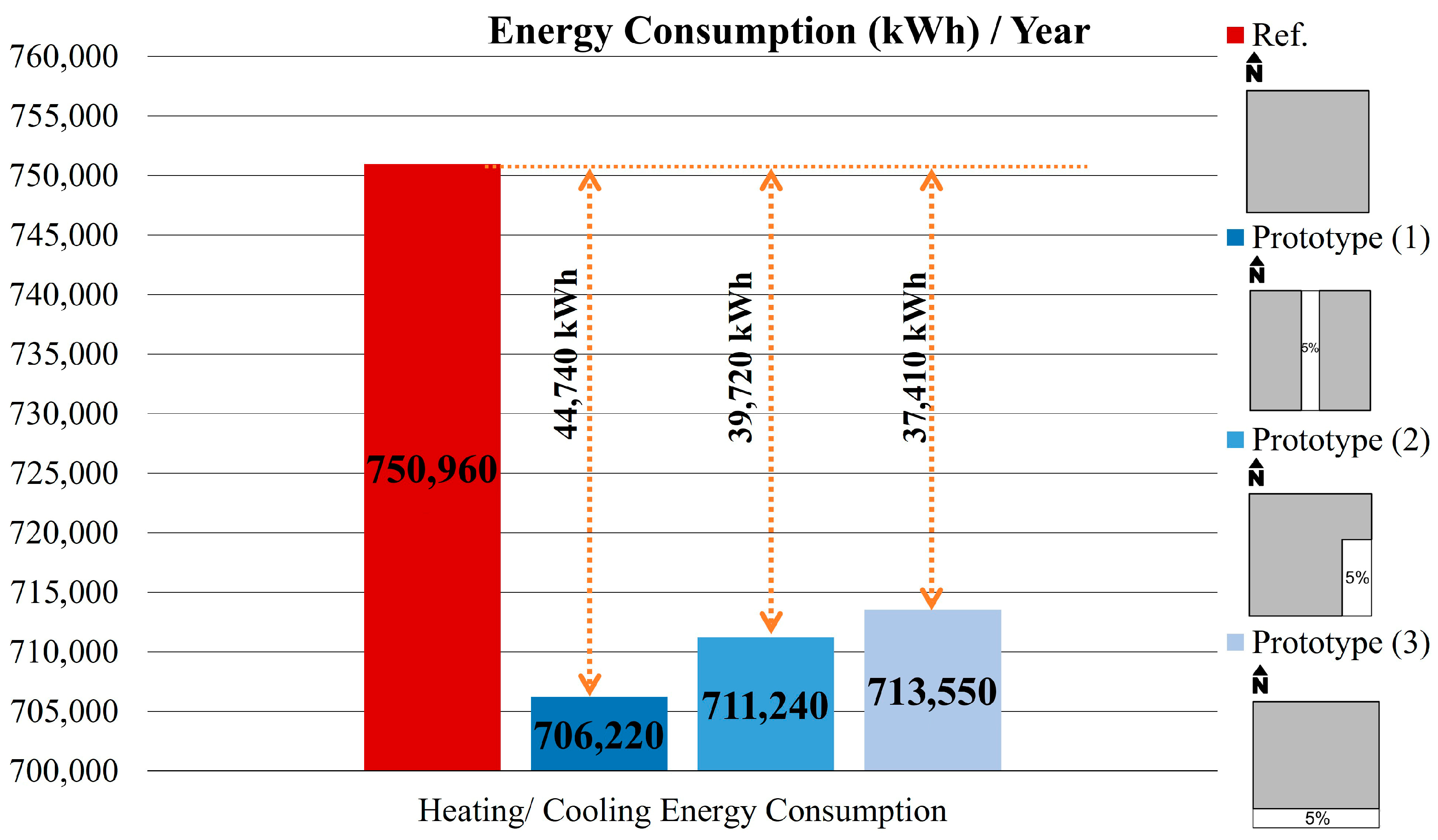

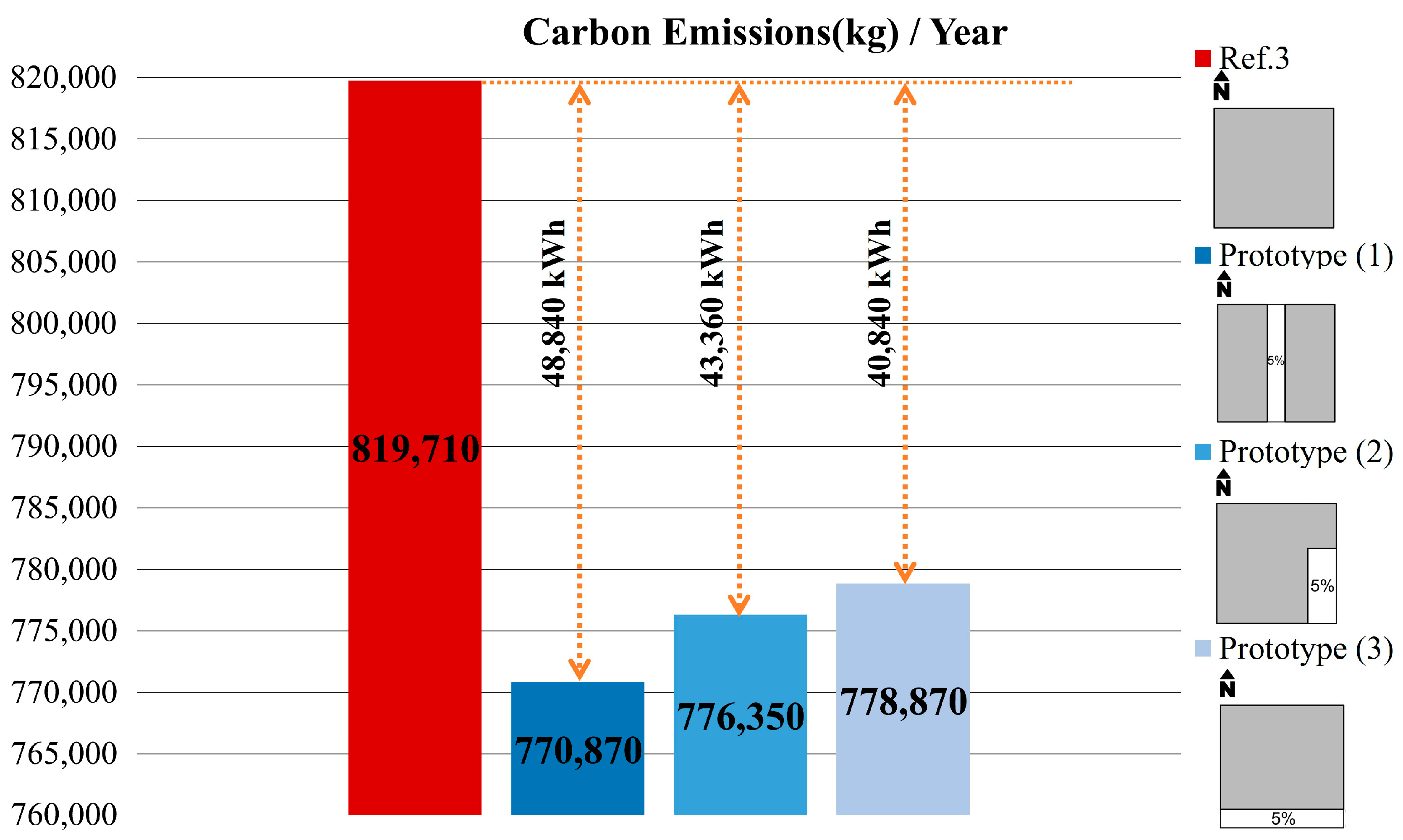

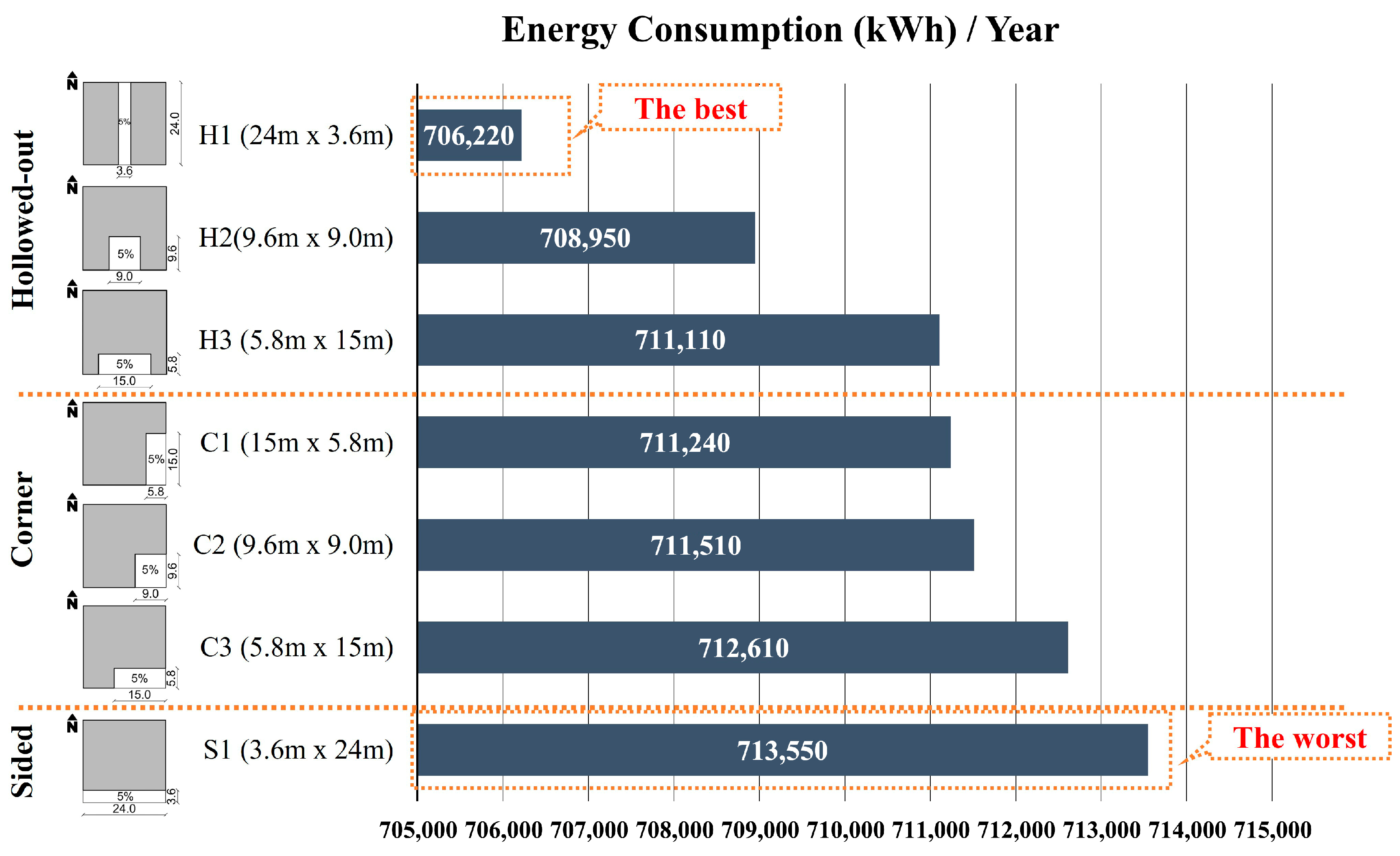

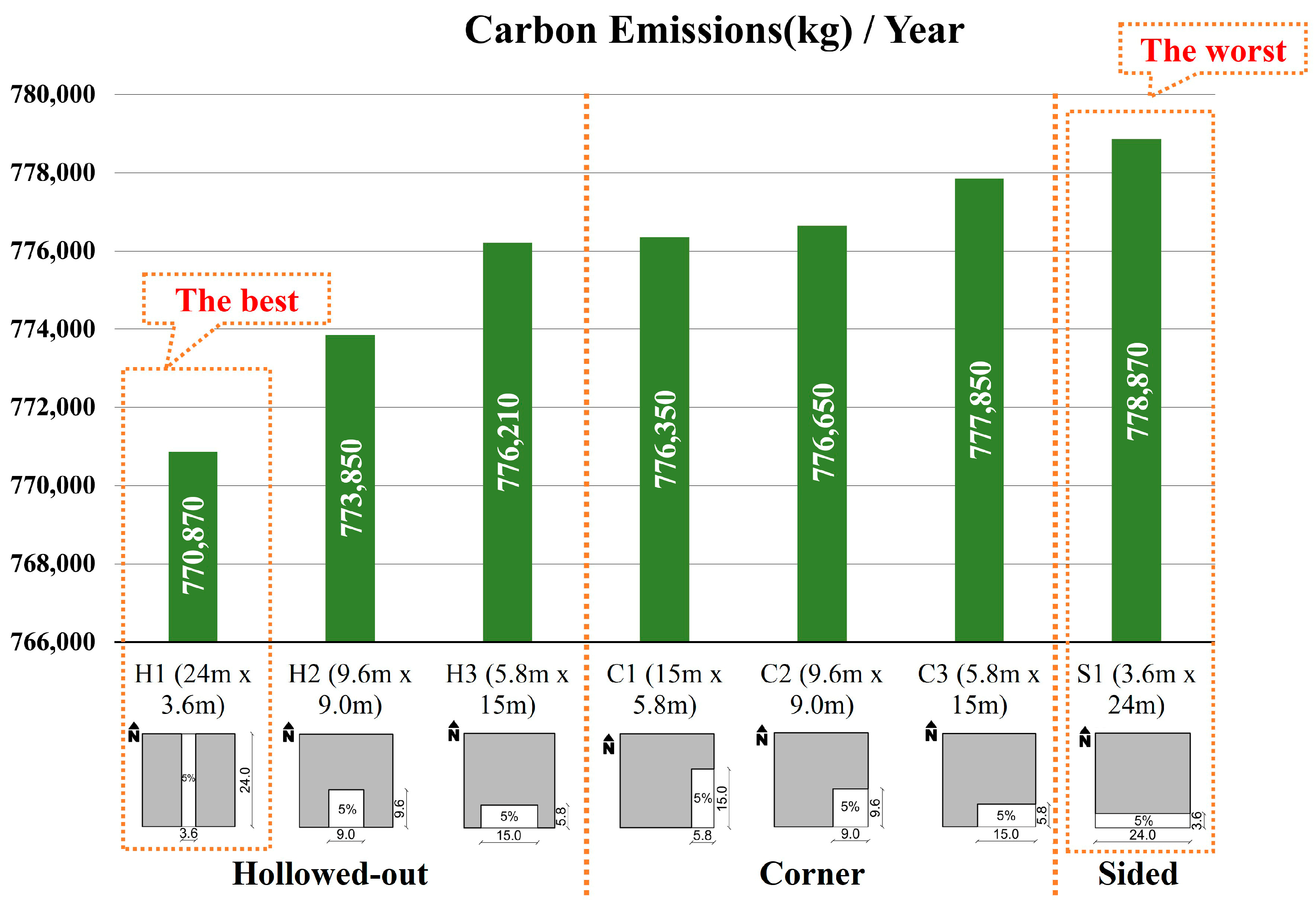

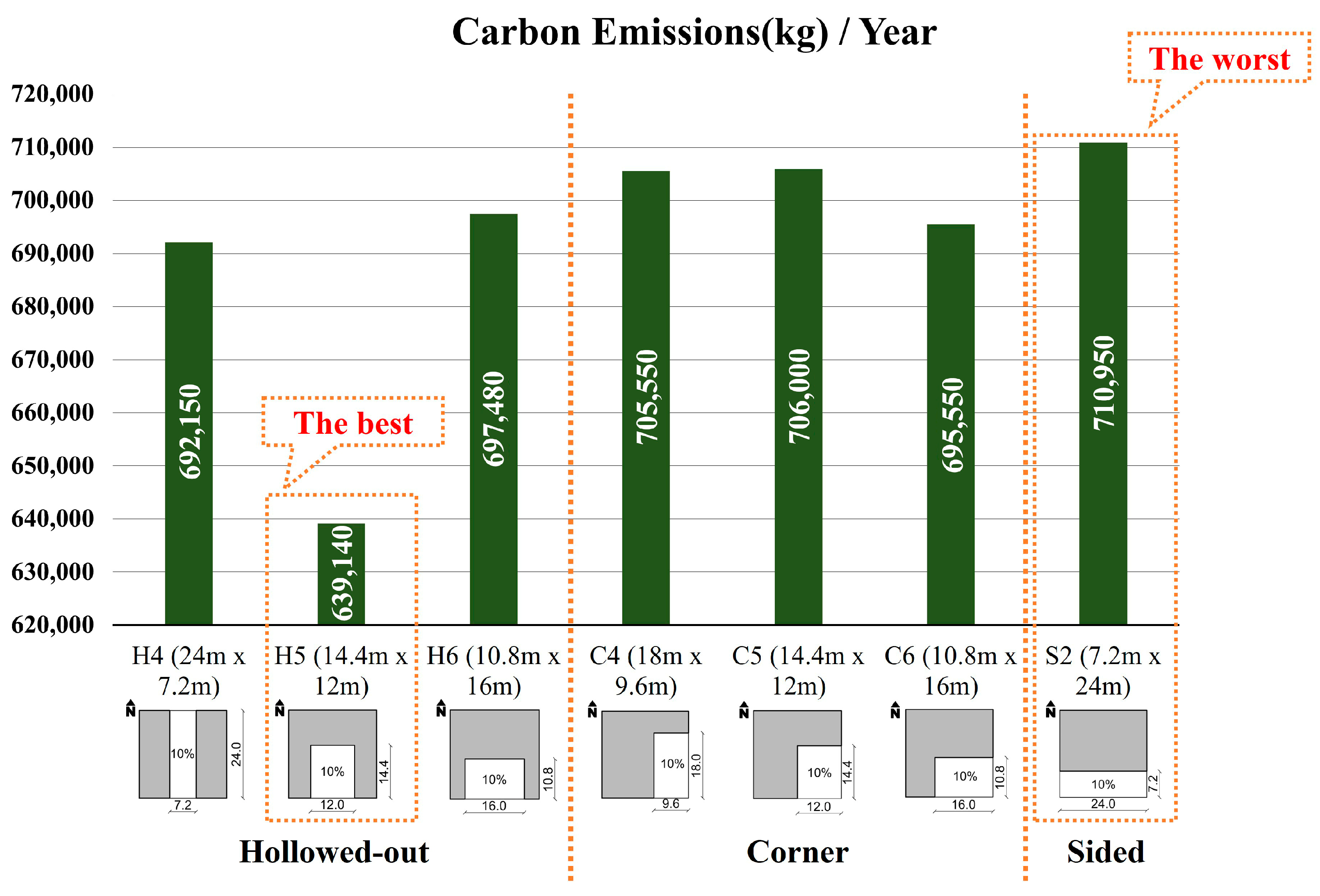

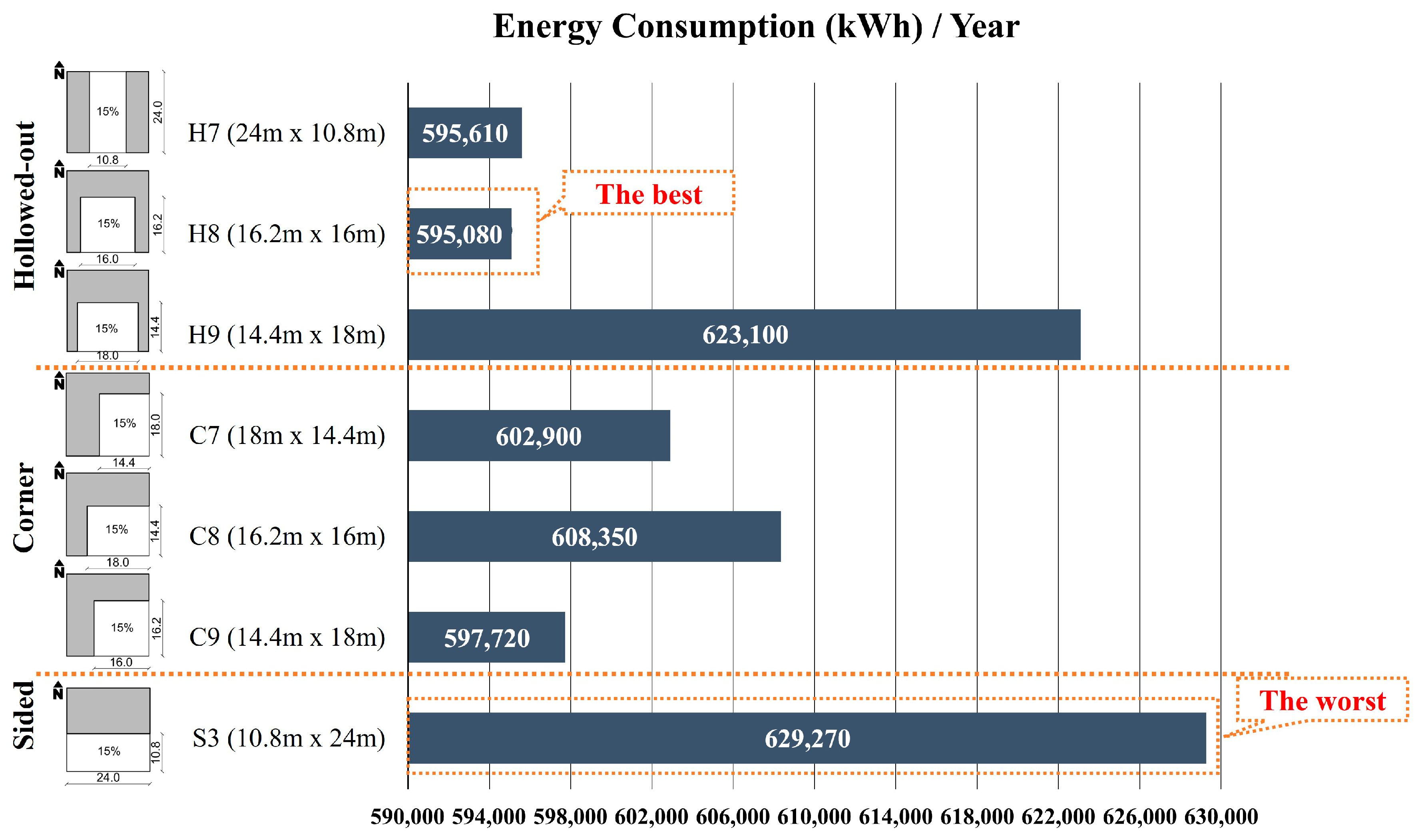

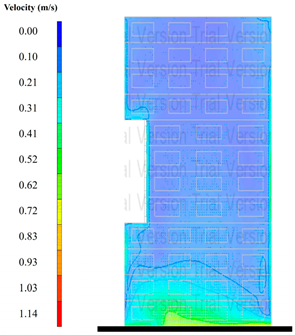

Results of Integrating a Skycourt in a Multi-Story Building

5. Discussion, Limitations, Practical Implications, and Future Work

5.1. Optimizing Skycourt Geometry

5.2. Optimizing Skycourt Dimensions

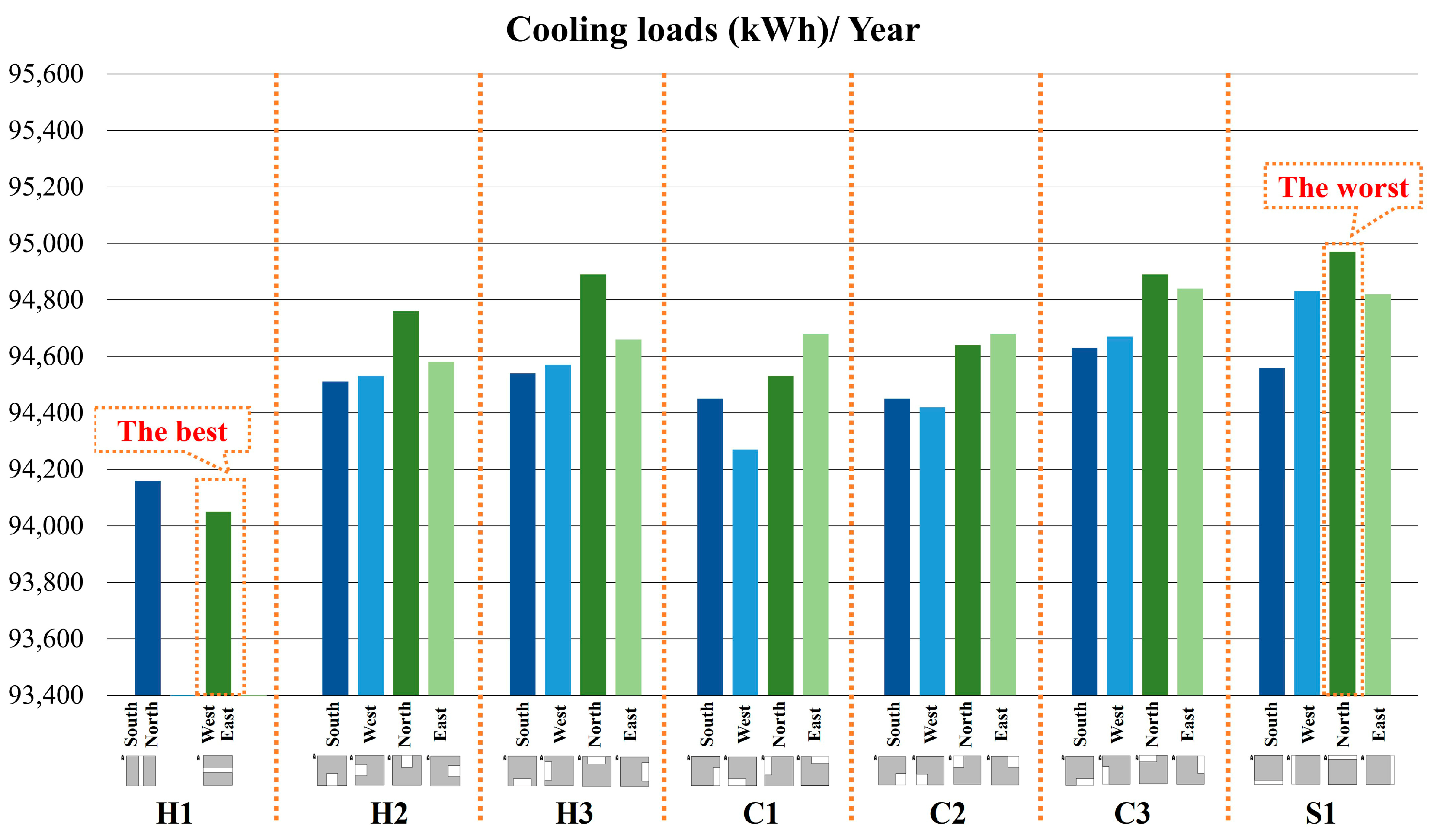

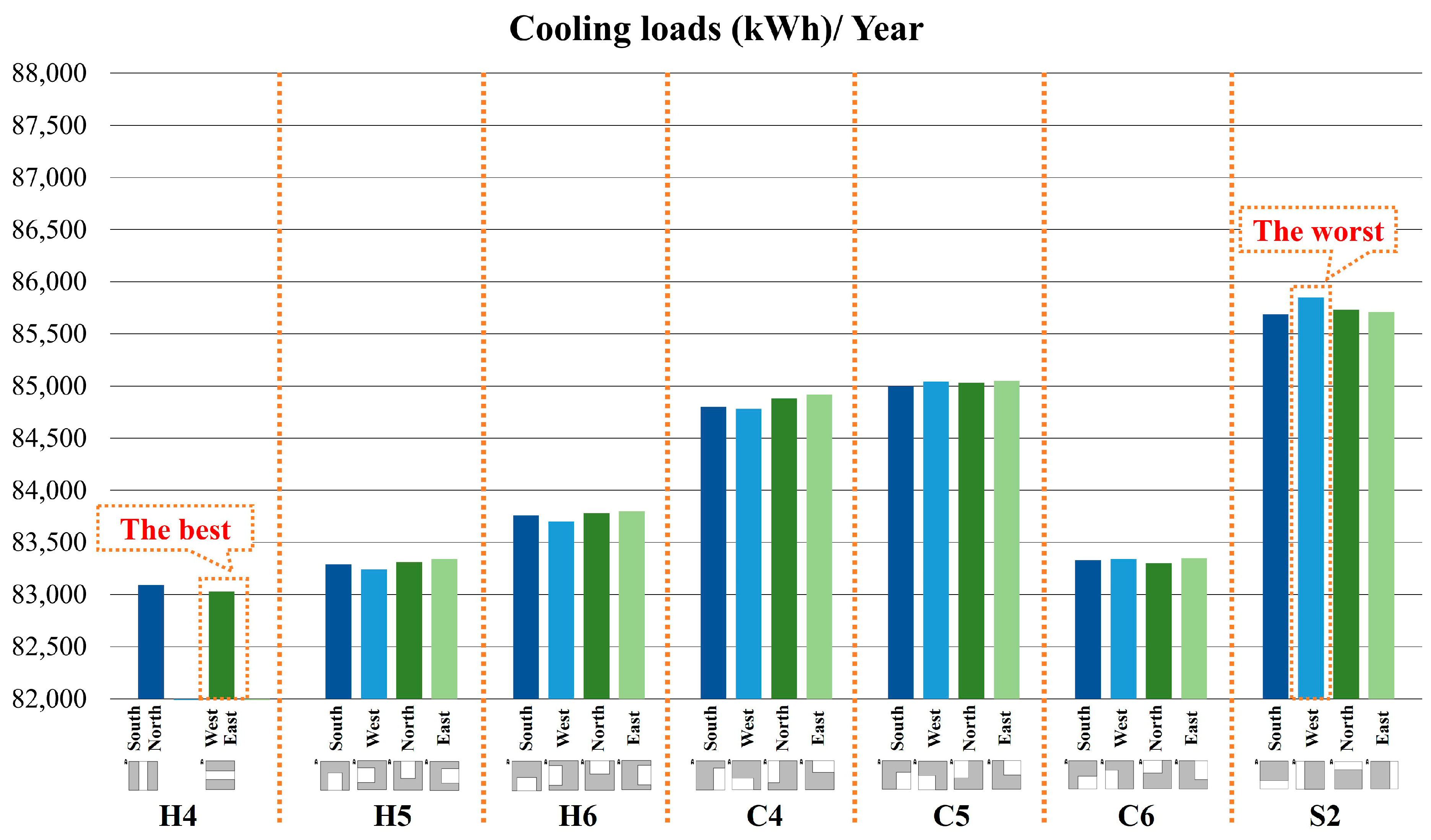

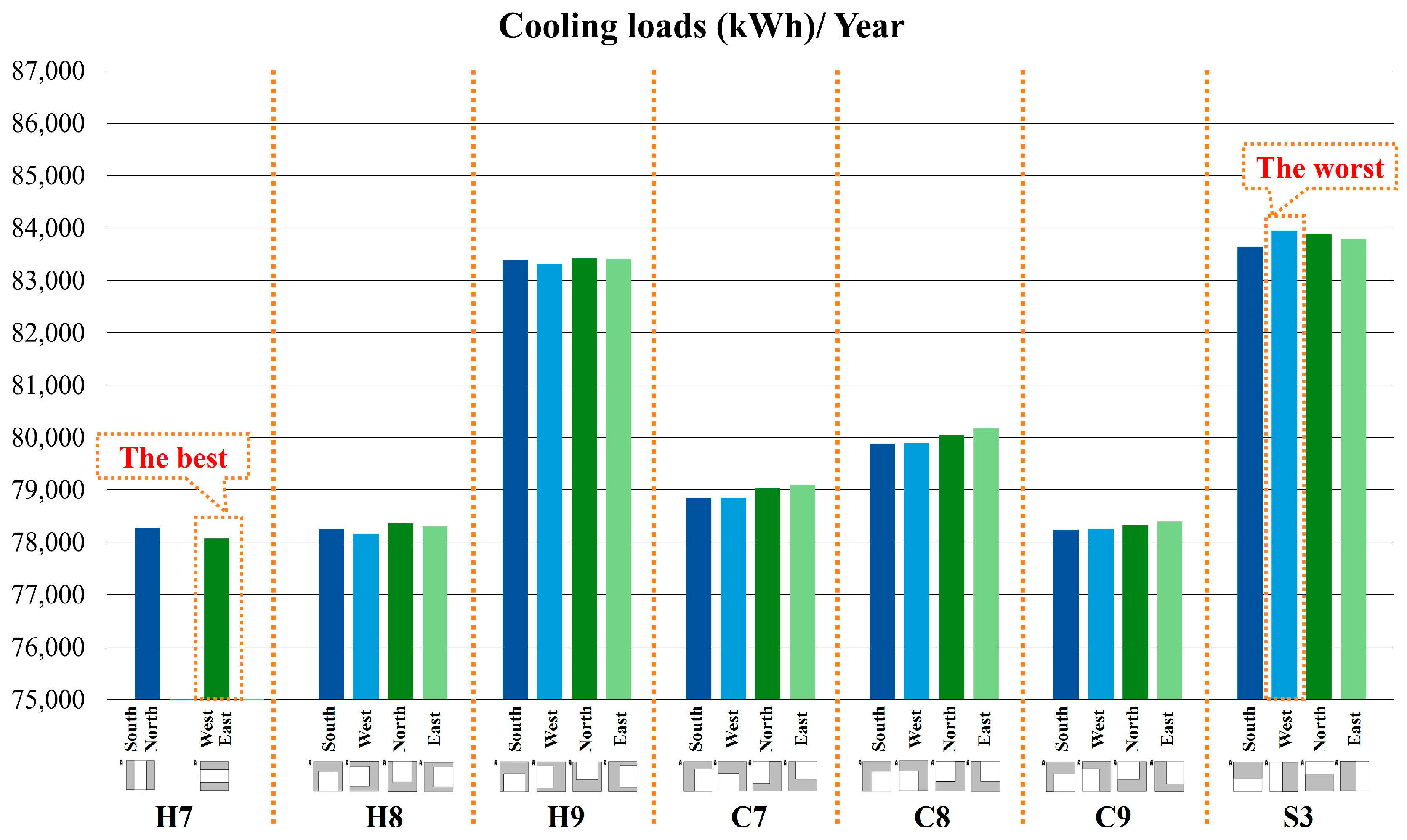

5.3. Optimizing Skycourt Orientation

5.4. Proposed Matrix

5.5. Limitations, Practical Implications, and Future Work

5.6. Main Findings and Contributions to Sustainability

6. Conclusions

- The verification results of the Design Builder simulation indicated a high correlation between reference research results and simulation results for air temperature and velocity. The average deviation rate ranged from 3.6 to 4.9%, which provides the ability to use the model of Design Builder simulation software as a tool to evaluate the environmental and functional role of skycourt spaces for the building.

- The results of the simulation process demonstrated the effect of skycourt spaces, especially the hollowed-out skycourt, in reducing air temperature by up to 3 °C during the hottest summers and reducing energy consumption by rates ranging between 8 and 10% annually in most alternative prototypes and reducing carbon emissions by ratios of up to 10% annually.

- Optimizing morphological indicators of skycourt usage, like EAR and FAR, indicated that the prototype of the hollowed-out skycourt also retained the best performance in most of the alternatives, followed by the second alternative in the hollowed-out skycourt. Also, the sided skycourt cannot be considered the best alternative in most cases, owing to the resulting high energy consumption. These results indicate a direct relationship between both indicators, EAR and FAR, and the increased environmental performance of the skycourt.

- For the skycourt orientation, it was found that the southern and western orientations had the best effect in increasing the performance of the skycourt. Orienting the skycourt to the south helps in providing a greater amount of shade and reducing solar gain. In addition, orienting the skycourt to the west helps in taking advantage of the favorable winds inside the spaces.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tolba, L.; Mokadem, A.; Badawy, N.; Shahda, M. A Retrofitting Framework for Improving Curtain Wall Performance by the Integration of Adaptive Technologies. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejat, P.; Jomehzadeh, F.; Taheri, M.M.; Gohari, M.; Majid, M.Z.A. A Global Review of Energy Consumption, CO2 Emissions and Policy in the Residential Sector (with an Overview of the Top Ten CO2 Emitting Countries). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 843–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Garg, A.; Mei, G.; Jiang, M.; Wang, H.; Huang, S.; Gan, L. Thermal Performance and Energy Consumption Analysis of Eight Types of Extensive Green Roofs in Subtropical Monsoon Climate. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 108982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, C.; Han, Y. Impact of Outdoor Microclimate on the Performance of High-Rise Multi-Family Dwellings in Cold Areas and Optimization of Building Passive Design. Build. Environ. 2024, 248, 111038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, L.; Sun, B. Comparison Analysis on Simplification Methods of Building Performance Optimization for Passive Building Design. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 108990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M. UMC-Based Models: An Integrating UMC Performance Analysis and Numerical Methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 181, 113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Marsono, A.K. Optimization of Building Energy Performance through Passive Design Strategies. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, A.; Eleinen, O.; Eltarabily, S.; Elgheznawy, D. Enhancing Urban Resilience in Hot Humid Climates: A Conceptual Framework for Exploring the Environmental Performance of Vertical Greening Systems (VGS). Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1260–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabadkani, A.; Aghasizadeh, S.; Banihashemi, S.; Hajirasouli, A. Courtyard Design Impact on Indoor Thermal Comfort and Utility Costs for Residential Households: Comparative Analysis and Deep-Learning Predictive Model. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabesh, T.; Sertyesilisik, B. An Investigation into Energy Performance with the Integrated Usage of a Courtyard and Atrium. Buildings 2016, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgheznawy, D.; Eltarabily, S. The Impact of Sun Sail-Shading Strategy on the Thermal Comfort in School Courtyards. Build. Environ. 2021, 202, 108046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrani, S.; Garcia-Hansen, V.; Capra, B.; Drogemuller, R. Natural Ventilation in Multi-Storey Buildings: Design Process and Review of Evaluation Tools. Build. Environ. 2017, 116, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masri, N.; Abu-Hijleh, B. Courtyard Housing in Midrise Buildings: An Environmental Assessment in Hot-Arid Climate. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jin, Y.; Guo, J. Dynamic Characteristics and Adaptive Design Methods of Enclosed Courtyard: A Case Study of a Single-Story Courtyard Dwelling in China. Build. Environ. 2022, 223, 109445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagneid, A. The Creation of a Courtyard Microclimate Thermal Model for the Analysis of Courtyard Houses. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, J. Skycourts as Transitional Space: Using Space Syntax as a Predictive Theory. In Proceedings of the Congress Proceedings, Tall and Green: Typology for a Sustainable Urban Future, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–5 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, R.; Buys, L.; Miller, E. Residents’ Experiences of Privacy and Comfort in Multi-Storey Apartment Dwellings in Subtropical Brisbane. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7741–7761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnusairat, S.; Jones, P.; Hou, S. Skycourt as a Ventilated Buffer Zone in Office Buildings: Assessing Energy Performance and Thermal Comfort. In Proceedings of the Design to Thrive, PLEA 2017 Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 2–5 July 2017; pp. 4901–4908. [Google Scholar]

- Sev, A.; Aslan, G. Natural Ventilation for the Sustainable Tall Office Buildings of the Future. Int. J. Archit. Environ. Eng. 2014, 8, 897–909. [Google Scholar]

- Alnusairat, S.; Jones, P. The Influence of Skycourt as Part of Combined Ventilation Strategy in High-Rise Office Buildings. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Sustainability, Energy & Environment 2017, Brighton, UK, 7–9 July 2017; The International Academic Forum: Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Du, H.; Sezer, C. Sky Gardens, Public Spaces and Urban Sustainability in Dense Cities: Shenzhen, Hong Kong and Singapore. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, P.; Trabucco, D.; Wood, A. Five Energy Generations of Tall Buildings: An Historical Analysis of Energy Consumption in High-Rise Buildings. J. Archit. 2009, 14, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, K. The Green Skycraper–The Basis for Designing Sustainable Intensive Buildings; Prestel: Munich, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fezi, B.A. Health Engaged Architecture in the Context of COVID-19. J. Green Build. 2020, 15, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnusairat, S. Approaches to Skycourt Design and Performance in High-Rise Office Buildings in a Temperate Climate. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, J. The Sky Court: A Viable Alternative Civic Space for the 21St Century? CTBUH J. 2007, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbat, N. The Courtyard House: From Cultural Reference to Universal Relevance; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 1351545388. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, J. The Skycourt and Skygarden: Greening the Urban Habitat; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781315881645. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, M.; Tien, P.W.; Calautit, J.K. Numerical Evaluation of the Use of Vegetation as a Shelterbelt for Enhancing the Wind and Thermal Comfort in Peripheral and Lateral-Type Skygardens in Highrise Buildings. Build. Simul. 2023, 16, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.-Q.; He, B.-J.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, D.-X.; Darko, A.; Zhao, Z.-Q. Sensitivity Analysis of Wind Pressure Coefficients on CAARC Standard Tall Buildings in CFD Simulations. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 16, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnusairat, S.; Jones, P. Ventilated Skycourts to Enhance Energy Savings in High-Rise Office Buildings. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2020, 63, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, P.W.; Calautit, J.K. Numerical Analysis of the Wind and Thermal Comfort in Courtyards “Skycourts” in High Rise Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 24, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnew, A.K.; Bitsuamalk, G.T.; Merrick, R. Computational Evaluation of Wind Pressures on Tall Buildings. In Proceedings of the 11th Americas Conference on Wind Engineering, San Juan, PR, USA, 22–26 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Z.; Chen, Q. Solution Characters of Iterative Coupling between Energy Simulation and CFD Programs. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbason, M.; Reiter, S. Coupling Building Energy Simulation and Computational Fluid Dynamics: Application to a Two-Storey House in a Temperate Climate. Build. Environ. 2014, 75, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropper, P.; Yang, T.; Cook, M.; Fiala, D.; Yousaf, R. Coupling a Model of Human Thermoregulation with Computational Fluid Dynamics for Predicting Human-Environment Interaction. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2010, 3, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahda, M.; Megahed, N. Post-Pandemic Architecture: A Critical Review of the Expected Feasibility of Skyscraper-Integrated Vertical Farming (SIVF). Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2022, 19, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asawy, M.; Ahmed, E.B. Environmental Assessment of the Egyptian Building Law Environmental Impact Study of the Residential Building’s Law in Egypt. J. Urban Res. 2022, 45, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Megahed, N.; Eltarabily, S. Numerical Investigation of the Indoor Thermal Behaviour Based on PCMs in a Hot Climate. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2022, 65, 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Samaty, H.S.; Waseef, A.A.E.; Badawy, N.M. The Effects of City Morphology on Airborne Transmission of COVID-19. Case Study: Port Said City, Egypt. Urban Clim. 2023, 50, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, R.Y.; El-Rayes, A.E.; Sultan, Y.M.; Aziz, A.M. Mapping of Soil Geochemistry in Port Said Governorate, Egypt Utilizing GIS and Remote Sensing Techniques. Imperial J. Interdiscip. Res. 2017, 3, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.; Omran, E.-S. Modelling of Land-Use Changes and Their Effects by Climate Change at the Southern Region of Port Said Governorate, Egypt. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- meteoblue. Climate Port Said. Available online: https://www.meteoblue.com/en/weather/historyclimate/climatemodelled/port-said_egypt_358619 (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Wikepedia Port Said. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Said (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Elzeni, M.; Elmokadem, A.; Badawy, N. Classification of Urban Morphology Indicators towards Urban Generation. Port-Said Eng. Res. J. 2021, 26, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Method | Tool | Validation Method | Validated with Ref. | Climate | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | Simulation | ANSYS® FLUENT 18.1 software | Wind tunnel | [30] | ــــــــــــــ | Velocity and temperature. |

| [31] | Simulation | HTB2 and WinAir(version 4) software | ــــــــــــــ | ــــــــــــــ | Temperate | Energy consumption, temperature, and velocity. |

| [32] | Simulation | ANSYS Fluent 18 | Experimental and numerical data | [33] | Warm-humid | Pressure and velocity. |

| [18] | Simulation | HTB2 and WinAir(version 4) software | ــــــــــــــ | ــــــــــــــ | Temperate | Heating and cooling demand, temperature, and velocity. |

| Internal Heat Gain | Building Fabric | Ventilation Setting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupancy (People/m2) | 0.083 | Glazing (U-value) | 1.5 W/m2 C | Infiltration rate | 3.5 m3/(m2 h) at 50 Pa |

| Window-to-wall ratio | 70% | Air supply rate | 10 L/s per person | ||

| People | 12 W/m2 | External wall (U-value) | 0.18 W/m2 C | Heating set point | 18 °C |

| Equipment | 15 W/m2 | Internal wall (U-value) | 0.22 W/m2 C | Cooling set point | 25 °C |

| Lighting | 12 W/m2 | Floor/ceiling (U-value) | 0.20 W/m2 C | Operating time | 08:00 a.m.–02:00 p.m. |

| Output | Air Temperature °C | Velocity m/s |

|---|---|---|

North |  |  |

| Deviation rate | 1.11% | 0.45% |

South |  |  |

| Deviation rate | 1.095% | 0.43% |

West |  |  |

| Deviation rate | 1.23% | 0.52% |

East |  |  |

| Deviation rate | 1.16% | 0.35% |

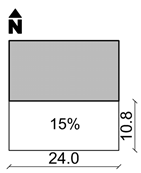

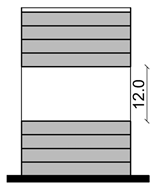

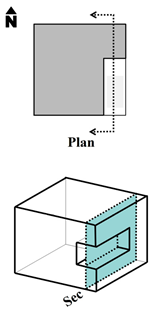

| Prototype (1) Hollowed-Out | Prototype (2) Corner | Prototype (3) Sided | Skycourt Area | Skycourt Volume | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

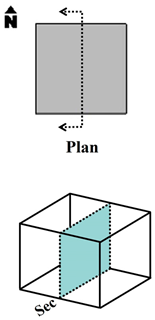

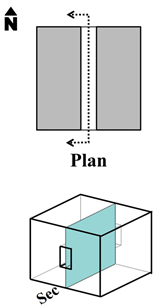

| Plan |  |  |  | 86.4 m2 | 345.6 m3 |

| Sec |  |  |  | ||

| The Skycourt Is 5% of the Building Volume in the South Façade of the 12-Story Building. | |||||||

| Hollowed-Out | Corner | Sided | |||||

| H1 | H2 | H3 | C1 | C2 | C3 | S1 | |

| Plan |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Sec |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| EAR | 6.7 | 1.07 | 0.39 | 2.6 | 1.07 | 0.39 | 0.15 |

| FAR | 5% | ||||||

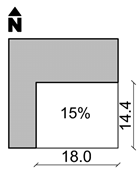

| The Skycourt is 10% of the Building Volume in the South Façade of the 12-Story Building. | |||||||

| Hollowed-Out | Corner | Sided | |||||

| H4 | H5 | H6 | C4 | C5 | C6 | S2 | |

| Plan |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Sec |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| EAR | 3.3 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| FAR | 10% | ||||||

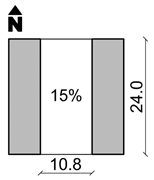

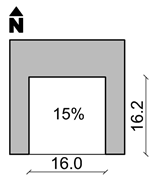

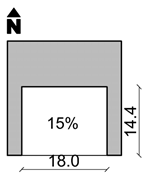

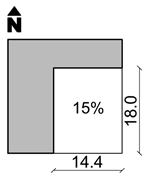

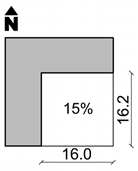

| The Skycourt is 15% of the Building Volume in the South Façade of the 12-Story Building. | |||||||

| Hollowed-Out | Corner | Sided | |||||

| H7 | H8 | H9 | C7 | C8 | C9 | S3 | |

| Plan |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Sec |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| EAR | 2.2 | 1.01 | 0.8 | 1.25 | 1.01 | 0.8 | 0.45 |

| FAR | 15% | ||||||

| Building Characteristics | |||

| Location | Port Said, Egypt | Activity | Residential |

| Occupancy (People/m2) | 0.06 | Window (30% glazed) | Sgl Clr 6 mm |

| Lighting | T8 (25 mm diam) Fluorescent | HVAC System | Natural ventilation |

| Building Construction | |||

| Ground floor (U-value = 0.8 W/m2 K) | 0.02 m ceramic tiles 0.08 sand/mortar/Plaster 0.02 m membrane 0.10 m light-reinforced concrete 0.15 m base-course stone | External walls (U-value = 0.9 W/m2 K) | 0.02 m plaster with paint 0.25 m concrete block 0.02 m plaster with paint (light) |

| Internal wall (U-value = 1.21 W/m2 K) | 0.02 m thick plaster (light) 0.12 m thick concrete blocks 0.02 m thick plaster (light) | Roof (U-value = 0.74 W/m2 K) | 0.02 m cement tiles 0.02 m cement mortar 0.06 m of sand for roof leveling 0.04 m MW Stone Wool 0.02 m Bitumen, pure 0.15 m reinforced concrete 0.02 m plaster with paint (light) |

| Ceilings (U-value = 0.85 W/m2 K) | 0.02 m ceramic tiles 0.08 mortar/Plaster 0.10 m reinforced concrete 0.02 m plaster with paint (light) | ||

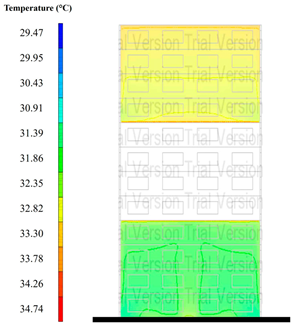

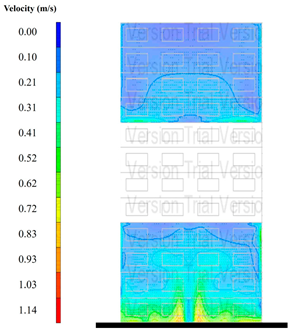

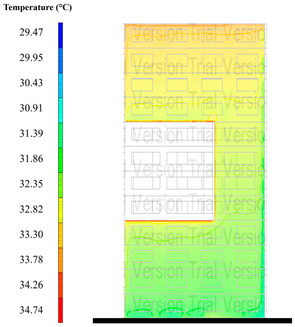

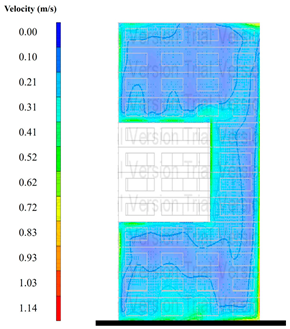

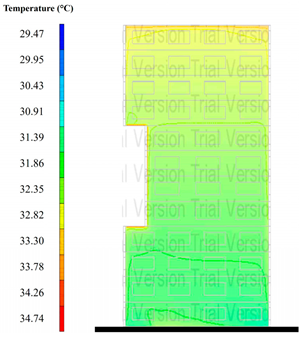

| Temperature (°C) | Velocity (m/s) | Figures | |

| Ref. |  |  |  |

| Prototype 1 |  |  |  |

| Prototype 2 |  |  |  |

| Prototype 3 |  |  |  |

| No.of. Floors | Skycourt Ratio | Hollowed-Out Skycourt | Corner Skycourt | Sided Skycourt | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3 | Alternative 4 | Alternative 5 | Alternative 6 | Alternative 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| S-N | W-E | S | W | N | E | S | W | N | E | S | W | N | E | S | W | N | E | S | W | N | E | S | W | N | E | ||

| 12-story building | 5% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The optimal alternative |  | The middle alternative |  | The last alternative | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No.of. Floors | Orientation | 5% | 10% | 15% | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3 | Alternative 4 | Alternative 5 | Alternative 6 | Alternative 7 | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3 | Alternative 4 | Alternative 5 | Alternative 6 | Alternative 7 | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3 | Alternative 4 | Alternative 5 | Alternative 6 | Alternative 7 | ||

| 12-story building | S | |||||||||||||||||||||

| W | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| N | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| E | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The optimal alternative |  | The middle alternative |  | The last alternative | |||||||||||||||||

| No.of. Floors | Skycourt Configuration | Prototype | 5% | 10% | 15% | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | W | N | E | S | W | N | E | S | W | N | E | |||||||

| 12-story building | Hollowed-out Skycourt | Alternative 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alternative 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Corner Skycourt | Alternative 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Alternative 5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sided Skycourt | Alternative 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| The optimal alternative |  | The middle alternative |  | The last alternative | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Megahed, N.A.; Ali, R.A.; Shahda, M.M.; Hassan, A.M. Integrating Skycourts into Multi-Story Buildings for Enhancing Environmental Performance: A Case Study of a Residential Building in a Hot-Humid Climate. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411061

Megahed NA, Ali RA, Shahda MM, Hassan AM. Integrating Skycourts into Multi-Story Buildings for Enhancing Environmental Performance: A Case Study of a Residential Building in a Hot-Humid Climate. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411061

Chicago/Turabian StyleMegahed, Naglaa A., Rasha A. Ali, Merhan M. Shahda, and Asmaa M. Hassan. 2025. "Integrating Skycourts into Multi-Story Buildings for Enhancing Environmental Performance: A Case Study of a Residential Building in a Hot-Humid Climate" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411061

APA StyleMegahed, N. A., Ali, R. A., Shahda, M. M., & Hassan, A. M. (2025). Integrating Skycourts into Multi-Story Buildings for Enhancing Environmental Performance: A Case Study of a Residential Building in a Hot-Humid Climate. Sustainability, 17(24), 11061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411061