Abstract

This research conducts a comparative analysis of the Environmental Impact Assessment’s (EIA’s) legal frameworks in Laos and China, utilising a qualitative methodological approach rooted in comparative law. This research systematically examines primary legal documents, case studies from the hydropower and mining sectors, and recent government data to evaluate the two systems based on three core criteria: the robustness of the legal structure, the effectiveness of enforcement mechanisms, and the depth of public participation. The analysis indicates that although both countries require Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), China’s framework is more structured and efficient, as demonstrated by its clearer legal hierarchy, strict penalties for non-compliance, and established public disclosure procedures. In contrast, Laos’s framework, although established, is marked by its early stage of development, evident in fragmented legislation, limited enforcement due to capacity constraints, and reduced public engagement. The study contributes by providing a direct bilateral comparison and empirically demonstrating how institutional divergences account for disparities in environmental outcomes and foreign investment. Recommendations are provided to improve transparency, enforcement capabilities, and substantive public engagement in both nations. This research is based on comparative legal theory and institutional analysis to transcend a mere descriptive narrative. It utilises a qualitative comparative methodology that combines doctrinal research of legal texts with practical case studies from the hydropower and mining industries. This method enables us to systematically investigate how differing institutional capacity, enforcement mechanisms, and governance models between an emerging and a developed system account for variations in EIA outcomes. The study questions are formulated to evaluate theoretical claims regarding the influence of legal frameworks and administrative authority on the attainment of good environmental governance, providing a transferable analytical model for analogous developing environments.

1. Introduction

The Chinese Environmental Impact Assessment framework has experienced multiple adjustments to incorporate environmental factors into development planning. Scholars observe that, notwithstanding its robust legal framework, it encounters considerable implementation challenges, including local economic–environmental conflicts and the propensity for public participation to devolve into a mere formality rather than a substantive element in decision-making (Johnson, 2020; Yao et al., 2020) [1,2].

Worldwide, development projects are required to conduct an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) to evaluate their possible social and environmental effects. These evaluations seek to recognise and alleviate significant environmental concerns during the planning phase. China and Laos have both established Environmental Impact Assessment frameworks in response to economic growth and environmental issues, but their distinct political, economic, and legal systems have influenced the development of these frameworks differently (UNEP. 2018; Burdett T; Dann, P; Riegner; et al.) [3,4,5].

Laos, a developing nation abundant in mineral, hydropower, and timber resources, instituted its Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system in the 1990s, motivated by the necessity to reconcile resource exploitation with environmental preservation. The Environmental Protection Law (1999) (Phimphanthavong, H. (2014)) [6] and related decrees establish the legal framework for Environmental Impact Assessment procedures, especially with infrastructure, mining, and hydropower projects. Laos encounters considerable obstacles, such as inadequate enforcement, minimal public participation, and restricted institutional capacity, which diminish the efficacy of its EIA system.

Conversely, China’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system, instituted in the late 20th century and formalised by the Environmental Protection Law and the EIA Law (2003), is more systematic and sophisticated. Despite ongoing local economic–environmental tensions and restricted public engagement, China’s Environmental Impact Assessment framework has progressively strengthened. Challenges remain, especially in reconciling environmental protection with GDP-oriented industries (He, X. Mitigation 2021 et al.) [7].

This paper analyzes the Environmental Impact Assessment systems in China and Laos, emphasising their legal frameworks, enforcement mechanisms, and public engagement methods. It seeks to evaluate their effectiveness in tackling the environmental issues arising from swift economic expansion. Utilising worldwide models of EIA efficacy (e.g., Cashmore, 2004; Bond & Pope, 2012) [8,9], the study situates these findings within the global context of sustainable development and environmental governance.

The research, moreover, provides novel empirical material, encompassing the most recent FDI statistics and hydropower effect metrics, to statistically assess the legislation and implementation variances between the two nations. The analysis highlights the contrast between China’s enforcement challenges and Laos’s institutional capacity constraints, offering specific recommendations for enhancing environmental governance and fostering sustainable investment.

Principal research inquiries encompass: (a) What impediments obstruct the implementation of EIA legislation in each nation, and how effective are the corresponding systems in surmounting these challenges? (b) What is the importance of public input in the EIA process, and how can it be improved in both countries? (c) How is the effectiveness of public participation assessed, particularly in relation to its legal basis, consultation methods, and its quantifiable impact on project approvals?

This study uses a qualitative comparative methodology to analyse the legal frameworks and Environmental Impact Assessment processes in both countries. This encompasses an examination of crucial legal texts, such as the Environmental Protection Laws and EIA Regulations, while evaluating the functions of governmental bodies, including China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment and Laos’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (Sajeva, M.; Maidell, M.; Kotta, J.; Peterson et al., 2020) [10]. We will utilise case studies of significant projects in both countries, along with perspectives from practitioners and specialists in environmental legislation. This study seeks to identify the factors contributing to the success or failure of EIA implementation in both nations and proposes recommendations for enhancing public participation, legal frameworks, and institutional efficacy. Policymakers, environmentalists, and foreign investors will gain from the findings, which enhance the overarching discourse on sustainable development and environmental governance in the region.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Progress on Environmental Impact Assessment Legislation in China and Laos

The current body of research provides extensive documentation on China’s and Laos’s separate EIA frameworks; however, it is mostly divided into analyses of individual countries or studies that focus on certain sectors (Patterson, C.; Casasanta Mostaço, F.; Jaeger 2022 Yang, M.; Jun, L.; Hongge, T.; Chengchen, Y.; Jiang, H.; Pan et al., 2025) [11,12]. Without a systematic comparative lens that connects variations in legislative design to disparities in investment patterns and environmental outcomes, this body of work frequently explains legal provisions or implementation issues in isolation (Glasson, J. 2022; Wang, Q; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q. 2025; Chali, 2024; et al.) [13,14,15]. Our research fills this void by bringing together these different threads in a focused bilateral analysis. We analyse how EIA efficacy is determined not only by legal language but also by institutional capability and enforcement rigour.

Despite the widespread respect for the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, recent studies reveal notably inconsistent effectiveness in developing-economy contexts (Governors, B.O. Asian Development Bank 2021; Russel, D.R.; Berger, B et al., 2019) [16,17]. A comparative study of 65 countries engaged in the China Communist Party’s Belt and Road Initiative revealed significant disparities in the quality of Environmental Impact Assessments, highlighting institutional capacity and governance gaps as critical determinants. The text clearly emphasises the gap between legislative frameworks and their practical implementations in both countries. Aung and Fischer’s comparative analysis of Belt and Road countries underscores the substantial impact of institutional capacity on the efficacy of Environmental Impact Assessment systems. This insight is essential for comprehending the divergent approaches adopted by Laos and China (Aung, T. S., & Fischer, T. B. (2020)) [18].

China and Laos encounter considerable obstacles in environmental governance, notwithstanding their developed Environmental Impact Assessment processes. In China, swift industrialisation and regional economic pressures hinder enforcement, resulting in extensive non-compliance despite robust legal frameworks. In Laos, inadequate institutional frameworks, along with insufficient resources and technical expertise, impede the efficient implementation of EIA requirements. The governance challenges intensify the obstacles to attaining the SDGs in both countries, particularly in industries like hydropower and mining that significantly affect their ecosystems (Yu, X.; He, D.; Phousavanh, P. Case study: 2018; Nickum, J.E.; Brooks, D.B 2018; Kittikhoun, A.; Staubli et al., 2018) [19,20,21].

A recent conceptual review outlines the evolution of the notion of “effectiveness”, shifting from a focus on procedural compliance to emphasising outcomes like environmental protection, public participation, and sustainable development (Sinclair, A.J.; Diduck, 2017; Carew-Reid, J. et al., 2016) [22]. Ana L. Caro-Gonzalez, Andreea Nita, Javier Toro, and Montserrat Zamorano (2023) [18] conducted a study. Evidence from case studies in countries such as Vietnam indicates that stakeholder perceptions frequently underscore issues like weak enforcement, limited transparency, and insufficient technical resources, which ultimately hinder the real-world effectiveness of EIA (Clarke BD, Vu CC. 2021) [23]. Evaluating the effectiveness of EIA in Vietnam: insights from key stakeholders). These studies collectively emphasise that legal instruments by themselves are not enough; strong institutional capacity, committed funding, consistent enforcement, and authentic participation are all essential components. This literature offers a robust comparative framework for analysing the practical performance of EIA systems in China and Laos while also outlining the essential enquiries regarding the factors that promote effective environmental governance in developing settings.

The evolution of EIA systems in Laos and China can be analysed using established effectiveness criteria, which evaluate the shift from procedural compliance to substantive environmental integration (Glasson & Therivel, 2013; Bond, 2013) [24,25]. This framework transcends simple description to assess the translation of legal frameworks into concrete environmental outcomes (Carew-Reid, 2016; Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. et al. 2012) [26,27].

Laos is a landlocked country located in Southeast Asia, bordered by China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar. It is known for its mountainous terrain and rich cultural heritage (Saming, C.; Kaewrungrueng, C.; Kakhai, P. et al., 2025) [28].

The People’s Democratic Republic of Laos (PDR) initiated its Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system in the 1990s, aligning with its resource-intensive economic development strategy. Projects that have significant environmental impacts, such as mining, hydropower, and infrastructure development, must perform Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) as mandated by the Environmental Protection Law (1999, amended 2012) Phimphanthavong, H. (2014) [6]. The 2022 Decree on Environmental Impact Assessment No. 389 further details public consultations and the assessment of potential environmental impacts. From an effectiveness standpoint, Laos’s system is still in the initial phase of development, mainly concentrating on achieving procedural compliance. The primary issue is the considerable disparity between established legal frameworks and their execution, constrained by inadequate institutional capacity and resources (Phaengsuwan, 2018) [29].

China is a country located in East Asia, known for its rich history, diverse culture, and significant global influence. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system in China has experienced a notable formal evolution since its inception in the 1980s, initiated by the 1979 Environmental Protection Law and reaching a critical milestone with the establishment of the Environmental Impact Assessment Law in 2003. This legislation requires Environmental Impact Assessments for all construction projects and highlights the importance of incorporating environmental factors into the planning process. A critical analysis indicates ongoing structural limitations that hinder its effectiveness. Scholars contend that, notwithstanding a strong legal framework, the system is frequently compromised by a “build first, approve later” approach and the significant impact of local economic growth objectives on environmental adherence (Caro-Gonzalez2023) [30]. Moreover, although public participation is required by law, it often becomes a mere procedural formality that exerts little meaningful impact on project results, underscoring a gap between legislative objectives and actual governance (Sosa Rodríguez et al., 2025) [31]. Consequently, China’s system illustrates the difficulty of attaining meaningful effectiveness, even in the context of a developed regulatory framework.

2.2. Problems with EIA Implementation

2.2.1. Laos

Inadequate institutional capacity and resources make it more difficult to enforce EIA regulations in Laos. Although the EIA process is supervised by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE), insufficient monitoring and compliance raise serious concerns about the efficacy of environmental protections. Local case studies provide tangible examples of these difficulties. Research on large hydropower projects, such as the Xayaburi Dam, has revealed persistent worries about sediment transport and the effects on fisheries. Monitoring and mitigation measures are frequently judged inadequate given the size of the projects, underscoring the disconnect between policy and environmental management on the ground (Bond, A.J. 2013) [32].

2.2.2. China

China has a more established EIA framework, but it still has many problems with enforcement. According to scholarly evaluations, sanctions for non-compliance are frequently insufficiently harsh to serve as a deterrent. Thomas Johnson (2020) [1], for instance, describes instances in which developers moved forward with construction without EIA approval, only to be subject to a retrospective assessment requirement and small fines a penalty insignificant in comparison to the project’s financial scope. This point is supported by MEE enforcement reports from 2021–2022, (Wang, Y., Morgan, R. K., & Cashmore, M. (2003)) [33], which frequently highlight cases in the mining and manufacturing industries where businesses opted to pay fines as a “cost of doing business” instead of stopping illegal construction, highlighting a structural problem where financial incentives can take precedence over environmental laws.

2.3. Comparative Analysis

This analysis utilises a structured framework to evaluate the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) systems in Laos and China based on three core criteria: legislative robustness, institutional capacity, and technical rigour.

The EIA Law (2003), which delineates explicit mandates and procedures, primarily governs China’s comprehensive and hierarchical legislative framework. In contrast, Laos’s regulatory framework is fragmented, primarily based on an Environmental Protection Law and supplemented by decrees, which may result in gaps and inconsistencies in its application.

Local economic interests may undermine the efficacy of China’s specialised and influential implementing agency, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE) in Laos encounters significant challenges, such as inadequate funding, a shortage of technical personnel, and restricted administrative authority, which greatly limits its enforcement capabilities.

China’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process increasingly integrates advanced methodologies, such as strategic environmental assessment (SEA), scientific modelling, and cumulative impact assessments. Laos’s system predominantly depends on qualitative evaluations and project-level assessments, which restrict its capacity to anticipate and address complex, long-term environmental impacts.

This tripartite framework demonstrates that although both systems exhibit procedural similarities, the differences in legislative cohesion, institutional authority, and technical sophistication account for the significant disparity in their overall effectiveness and environmental results.

3. Methodology

This research makes use of a comparative legal examination of the EIA frameworks in Laos and China as its technique. Examining the evolution, execution, obstacles, and public engagement processes of the EIA systems in the two nations is the primary objective. The research methodology is crafted to offer a comprehensive analysis of the practical implementation of EIA regulations in both nations and to identify potential areas for enhancement.

The comparative methodology was selected to assess the EIA systems according to three fundamental criteria: legal soundness, institutional competence, and public engagement. The criteria were chosen after evaluating the substantial differences in governance structures between an emerging system (Laos) and a developed system (China). Sources were chosen based on their pertinence to these criteria, encompassing primary law texts, case studies of significant development projects, and expert interviews from both nations.

The selection of legal documents, including the Environmental Protection Law and EIA Regulations from China and Laos, was determined by their pertinence to the established criteria of legal framework, enforcement mechanisms, and public engagement. Case studies were selected based on the substantial environmental implications of the projects and the accessibility of comprehensive EIA data. Alongide these legislative documents, interviews with practitioners and experts yielded significant qualitative insights into the practical issues encountered by the two countries in executing EIA procedures.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) systems in China and Laos were assessed and contrasted in this study using a comparative legal analysis methodology. The study uses a range of primary and secondary sources, including government publications, court records, and case studies from the mining and hydropower industries. We go into greater depth about each component of the process below.

Legal and policy document sources: Primary sources, including the Environmental Protection Law (China 1979, amended 2014), the Environmental Impact Assessment Law (China 2003), (Wang, Y., Morgan, R. K., & Cashmore, M. (2003)) [33] and the Environmental Protection Law of Laos (1999, amended 2012), Phimphanthavong, H. (2014) [6] as well as particular decrees on environmental impact assessment in both nations, were used to review the legal framework for EIA in China and Laos. These records were sourced from official publications, government websites, and national legal databases. The 2020 Environmental Protection Regulations in China and the 2022 Decree on Environmental Impact Assessment in Laos, for instance, were crucial in evaluating the EIA procedural frameworks. To guarantee accuracy and clarity, the publication years and legal citations of these documents are cited throughout the article.

Selection of the Case Study and Time Period: The analysis spans 1990–2022, showing how the EIA systems in both nations have changed since their founding. Case studies were chosen on the basis of recent data availability, project type (mining and hydropower), and significance (large infrastructure projects in both nations). Due to their significant environmental effect and the high frequency of EIA usage in both nations, these industries were selected. Key insights into the application and difficulties of the EIA procedures in major development projects may be gained from the case studies of the Three Gorges Dam (China) and the Xayaburi Dam (Laos).

Numerical Data Sources: Official government reports, yearly environmental assessments, and international publications like the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and OECD were the sources of all numerical data points, including compliance rates, foreign direct investment (FDI) figures, and environmental impact metrics. For instance, as stated in Table 1 the FDI numbers for mining and hydropower projects were taken from national economic reports covering the years 2020–2022. These figures were computed using government data on environmental performance metrics and project funding. Additionally, Environmental and Social Effect Assessment (ESIA) assessments of projects like the Nam Theun 2 and Xiaowan dams included particular environmental effect statistics, such as deforestation rates and biodiversity loss in large hydroelectric projects.

Table 1.

Show that Hydropower Environmental and Social Impacts.

3.1. An Intersectional Legal Perspective

This research makes use of a comparative legal technique to compare and contrast the legal systems of China and Laos in order to spot commonalities and differences as well as difficulties. By taking this tack, we can learn more about the specific political, economic, and environmental circumstances of each nation and how their legal systems handle environmental protection via EIA legislation (Dang, A.; Soe, K.N.; Inthakoun, L, et al., 2016) [34]. In this comparison, we will look at:

This study establishes a structured framework of three fundamental comparative criteria based on foundational environmental governance theory to facilitate systematic examination.

- Legal Framework: Analysing the hierarchy, specificity, and coherence of Environmental Impact Assessment statutes and regulations.

- Enforcement Mechanisms: Evaluating the efficacy of monitoring, compliance frameworks, and sanctions for non-compliance.

- Public Participation: Assessing legal frameworks and the practical execution of stakeholder involvement and information transparency.

This paradigm advances the analysis from anecdotal observation to a systematic assessment of how various legal-institutional architecture influence EIA effectiveness.

Legal Structure: Investigating the two nations’ guiding EIA statutes, rules, and regulatory systems from a legal perspective. This encompasses applicable decrees in both China and Laos as well as the Environmental Impact Assessment Law in China.

Enforcement Mechanisms: The effectiveness of monitoring and compliance systems, the role of government agencies (such as China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment and Laos’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment), and penalties for non-compliance are all factors to be considered when analysing the enforcement mechanisms of each country’s EIA laws.

Public Participation: The role of the public: contrasting the EIA procedures’ incorporation of public consultations and stakeholder involvement. Investigating the two nations’ approaches to public engagement, levels of openness, and legislative protections for such endeavours are all part of this process.

This study employs a comparative legal analysis based on a defined analytical framework to guarantee a systematic rather than anecdotal evaluation. The comparison is structured around three fundamental criteria based on environmental governance theory: (1) legal structure, analysing the hierarchy and coherence of environmental impact assessment laws and regulations; (2) enforcement mechanisms, evaluating the strengths of monitoring, compliance systems, and penalties; and (3) public participation, assessing both legal frameworks and practical execution for stakeholder involvement. This methodology is uniformly implemented across all data, including law documents, case studies, and official reports, directing the content analysis to directly compare Laos and China on each criterion. This approach guarantees that our conclusions about the discrepancies in EIA effectiveness are consistent, comparable, and experimentally substantiated.

3.2. Data Sources

The information used in this research came from a wide range of primary and secondary resources, such as:

- Legal Documents: Examined for Laos were the Mineral Law, the Decree on Environmental Impact Assessment (2020), and the Environmental Protection Law (1999).

The following laws and regulations pertaining to China were examined: the Environmental Impact Assessment Law (2003), the Environmental Protection Law (1979, revised 1989), (Wang, Y., Morgan, R. K., & Cashmore, M. (2003) [33] and others. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Regulations, national Environmental Protection Laws of Laos and China, and other related decrees provide a wealth of information. Understanding the statutory frameworks that govern environmental protection requires familiarity with these papers, which offer the legal basis for EIA systems in both nations.

- 2.

- Case Studies: In order to evaluate the practical implementation of EIA rules, we looked at specific case studies of development projects in China and Laos, including mining, hydropower, and infrastructural projects. Through the examination of specific cases, both the difficulties and the triumphs that have resulted from implementing the EIA legislation can be better understood.

- 3.

- Government Publications: To gain a better understanding of the laws’ application and enforcement in both nations, we looked at government publications like policy documents, EIA monitoring reports, and yearly environmental reports. These reports provide information regarding the efficacy and execution of EIA rules.

- 4.

- Academic Articles and Research Papers: Studies on EIA systems in China and Laos were based on a thorough literature evaluation of scholarly articles and reports. Books and scholarly articles on the subject cover the history, difficulties, and outcomes of EIA frameworks in the two nations. Research on Laos by Aung, T. S., Fischer, T. B., & Shengji, L. (2020) [18] and are important references.

3.3. Data Analysis

Legal documents are analysed using content analysis to uncover important provisions concerning EIA processes, enforcement mechanisms, and public engagement. This data analysis is then used to inform policymaking. Examining the EIA regulations and procedures of the two nations is the primary goal of this study. Here are the stages of the analysis: We evaluate the rules and regulations regarding environmental impact assessments (EIAs), public involvement, and penalties for noncompliance, as well as their goals and specific elements. The comparative analysis reveals the relative merits of the legal systems of the two nations. Reviewing case studies, government records, and expert opinions, we assess the efficiency of enforcement systems in both countries. This is part of our enforcement and compliance analysis. Examining factors including resource constraints, corruption, and insufficient supervision, this examination delves into the effectiveness of the laws’ implementation. Examining the legal protections for public involvement, the consultation procedures employed, and the level of public engagement in the EIA process in both nations allows us to assess the significance of public participation.

For each criterion, particular development projects were examined as case studies to ensure that the comparison framework was used practically. For example, the enforcement mechanisms and environmental results of the Three Gorges and Xiaowan dams in China and the Xayaburi and Nam Theun 2 dams in Laos were compared (Table 1). The quantitative information included in the results (such as FDI numbers and deforestation percentages) was methodically taken from government statistical yearbooks, World Bank documents, and official Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) reports for these projects. By validating and standardising the data for cross-national comparisons, this triangulation of sources made sure the research progressed from anecdotal evidence to an empirical, case-based assessment.

3.4. Limitations

There are some problems with the study, even though it does a good job of comparing a lot of things. The main problem is that it’s hard to get and use up-to-date government reports and statistics on EIA enforcement in both countries. There may also be differences in how EIA rules are applied in different parts of both Laos and China, which the study might not fully capture. This approach enables a comprehensive analysis of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) systems in China and Laos, illuminating their respective legislative frameworks, enforcement procedures, and the efficacy of public engagement. The purpose of this study is to review the EIA frameworks in both nations and draw conclusions about their relative merits and shortcomings. The research will draw from a variety of sources, including case studies, expert interviews, legal documents, and academic literature, in an effort to promote sustainable development and better environmental governance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. A Comparison of Legal Systems

While both China and Laos have implemented EIA frameworks to safeguard the environment and foster sustainable development, the two countries’ approaches to implementing these policies couldn’t be more different. The Environmental Protection Law and the Decree on Environmental Impact Assessment form the backbone of Laos’s EIA legal framework. In charge of regulating EIA procedures is the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MoNRE). Before a project can be greenlit, its developers must submit an ESIA report to the Ministry of Environment and Rural Employment (MoNRE). Limited institutional coordination, overlapping duties, and a dearth of robust enforcement mechanisms are, however, hallmarks of the Laotian system. Especially in areas that rely heavily on mining and are located in rural areas, this has led to a disconnect between policy and practice. China, on the other hand, has an EIA legal structure that is both more developed and thorough. It is based on two laws: the Environmental Impact Assessment Law (2003) and the Environmental Protection Law (1979, amended 2014) (Fisher, E. (2016)) [33,35]. Both the MEE and municipal environmental bureaus have their roles and duties laid out in these statutes. There are serious implications for failing to comply with China’s EIA mandate, which applies to all projects that may have an impact on the environment. The system of checks and balances is designed to make sure that bigger projects are reviewed at the federal level, while smaller ones are dealt with at the provincial or local level. There are a number of points in the project approval process where public involvement and disclosure are mandated by law.

Although there are some structural variations, there are also some important shared concepts between the two countries. For example, both countries need EIAs before project clearance, public input is highly valued, and environmental monitoring is included into both systems after approval. In contrast to China’s system, which places an emphasis on inter-agency accountability and procedural enforcement, Laos’ EIA framework is nevertheless constrained by a lack of human resources, inconsistent laws, and insufficient administrative authority.

Although EIA frameworks have been used in both China and Laos to protect the environment and promote sustainable development, the two countries’ strategies differ greatly in terms of both design and actual implementation (Aung, M.T.; Aung, M.M, et al., 2020) [36].

The Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MoNRE) is in charge of the Environmental Protection Law and the Decree on Environmental Impact Assessment. These two laws make up the basis of Laos’ EIA system (PDR Development Report et al., 2010 [37]. However, the administrative capacity to execute this system faces significant limitations. Certain indicators clearly demonstrate the magnitude of the problem: MoNRE’s relevant departments are frequently said to function with a small technical staff (typically less than 20 dedicated EIA officers nationwide), have severely constrained field monitoring budgets, and rely on crude, qualitative assessment tools (Phaengsuwan, 2018; Campbell, 2011) [29,38]. This circumstance leads to a system where enforcement is frequently reactive rather than proactive, and project approvals may be delayed due to a lack of resources rather than rigour.

The Environmental Protection Law (1979, modified 2014) and the Environmental Impact Assessment Law (2003) serve as the foundation for China’s more advanced and extensive EIA framework, which defines the responsibilities of local bureaus and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). However, practical implementation issues constantly put this strong legal foundation to the test. The efficacy of the system is frequently weakened by ongoing post-approval audit delays, intense financial pressure on local governments to expedite projects for GDP development, and pervasive conflicts of interest in the EIA consulting industry (Johnson, 2020; Wu et al., 2023) [1,39]. Even though the law requires public involvement and harsh penalties, these systemic problems frequently cause a discrepancy between what is required by law and what really occurs, especially in areas that place a high priority on rapid industrial development.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system in China has a clear legal framework, including the EIA Law (2003) [35] and the Environmental Protection Law (1979). These laws make it clear who is responsible for enforcing them and who is responsible. Laos, on the other hand, has a fragmented system that is mostly based on the Environmental Protection Law (1999, revised 2012) [40] and doesn’t have the same level of coherence as China’s system. Institutional capacity continues to be a major problem in Laos, as shown by the fact that there aren’t enough EIA officials and the budget isn’t big enough for monitoring.

4.2. Implementation and Challenges

4.2.1. Enforcement and Administrative Capacity

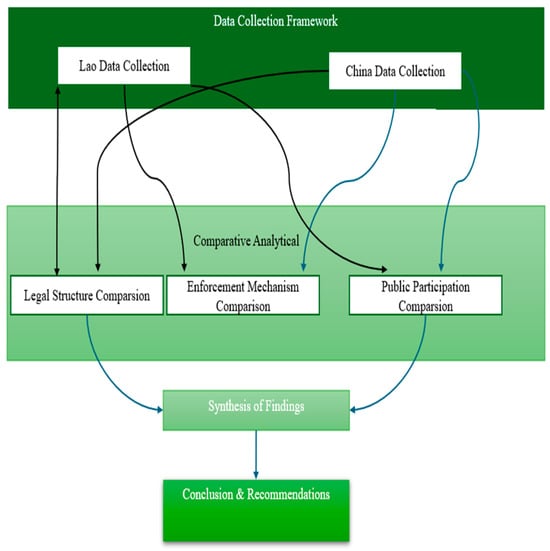

The fundamental obstacle in both nations is still implementation. Institutional flaws and competing priorities between national and provincial governments in Laos frequently impede the country’s law enforcement efforts. Local governments, motivated by short-term economic interests, often authorise projects that violate environmental norms, despite the fact that the federal government places an emphasis on environmental protection. Because of this, there is a fundamental misalignment between economic expansion and environmental sustainability [17,18,19]. Equally lacking in both vertical power and horizontal coordination are the administrative divisions at the local level. Provincial governors frequently have sway over environmental authorities, which results in lax enforcement and uneven monitoring. Damage control, not prevention, is the primary goal of the environmental regulatory system. Further limiting enforcement operations are insufficient training, low technical expertise, and little money. The difficulty in enforcing laws in China is due to the intricate bureaucracy and meddling of local governments. In order to entice investment, local authorities on occasion ignore infractions of China’s EIA Law, despite the law’s severe penalties (such as the suspension of projects, fines, and legal prosecution). Falsified EIA reports and the “build first, approve later” mentality are examples of the disconnect between legislation and practice. EIA approval times in China are far faster than in Laos. China processes most hydroelectric projects in 12 months, while Laos takes 24 months (see This difference reflects both countries’ EIA systems’ institutional capacity and efficiency. As depicted Figure 1. Mapping Data Collection: A visual representation of the process of gathering and comparing legal structures, enforcement mechanisms, and public participation in Laos and China.”. in our examination of particular case studies, including the Xayaburi and Nam Theun 2 dams in Laos and the Three Gorges and Xiaowan dams in China, reveals that Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) approval processes for significant hydroelectric projects may require approximately 24 months in Laos, in contrast to an average of 12 months for similar projects in China. This gap, evident in project documentation and highlighted in previous evaluations (e.g., Middleton, 2022) [41], signifies variations in institutional capability and procedural complexity between the two systems. Implementation is still a major issue in both countries. In China, enforcement gaps often challenge the complexity of the legal system. The common “build first, approve later” (xiān jiàn hòu pī) practice, in which projects begin development without EIA permission in the hopes that the financial advantages will outweigh any penalties later on, is a notable example of this. Academic research has extensively documented this practice, pointing out that local governments, under pressure to achieve economic growth goals, frequently tacitly allow such violations, resulting in retroactive assessments that fall short of the EIA law’s preventive goals (Johnson, 2020; Wu & Chang, 2020) [1,42].

Figure 1.

Mapping Data Collection: A visual representation of the process of gathering and comparing legal structures, enforcement mechanisms, and public participation in Laos and China.”.

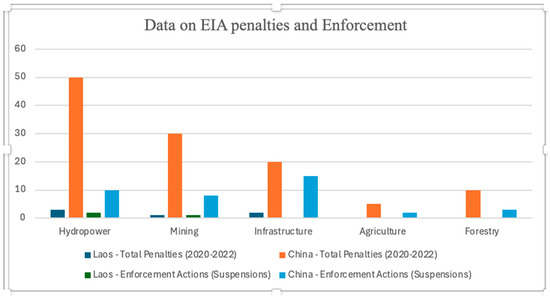

Project approval timelines reflect the differences in institutional efficiency. Although there are few direct comparative statistics, an examination of particular large hydropower projects, like the Xiaowan dam in China and the Xayaburi dam in Laos, shows that the approval process for similar projects in China typically takes 12 months, while in Laos it typically takes about 24 months (Middleton, 2022; Hennig et al., 2016) [41,43]. This discrepancy highlights the Chinese system’s increased bureaucratic capability and simplified, if not trouble-free, processes. Institutional weaknesses and conflicting national and provincial government goals further hampered enforcement in Laos. There is a fundamental imbalance between economic growth and environmental sustainability because local authorities, driven by short-term economic goals, regularly approve projects that defy environmental standards. Figure 2 presents the facts on Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) penalties and enforcement actions for Laos and China from 2020 to 2022. The graphic delineates the aggregate penalties and enforcement actions, particularly suspensions, across diverse industries, including hydropower, mining, infrastructure, agriculture, and forestry. The data reveals a notable disparity between the two countries, with Laos exhibiting a greater incidence of penalties in industries like hydropower and mining. Conversely, China exhibits a more equitable allocation of enforcement actions and penalties among sectors, especially in infrastructure.

Figure 2.

Show that Data on EIA penalties and Enforcement.

4.2.2. Motivation and Supervision

The absence of strong oversight and incentive systems is a big obstacle to successful implementation in both nations. Performance measures for local officials in China still place an emphasis on GDP growth rather than environmental compliance, in contrast to Laos where enforcement outcomes are seldom used to grade environmental officers. There is less of a need for stringent enforcement when there is no one to blame. Academics propose that government officials’ environmental protection performance be included in their evaluations in order to encourage more stringent compliance [42,44].

4.3. Public Engagement

Public engagement is legal in both systems but undeveloped. Citizens of Laos can report environmental issues, although few do. Citizens are discouraged from participating due to legal uncertainty and political risk. The public cannot get timely EIA project updates due to insufficient government information transparency. Due of insufficient input, EIAs can cause local populations and developers to distrust each other. In contrast, obligatory hearings and disclosure have institutionalised public engagement in China. The 2018 EIA Law changes emphasise digital feedback and information sharing mechanisms. Since decisions are determined before consultation, public involvement is sometimes procedural rather than influential. This gives the public a sense of “token participation,” acknowledging their role but rarely affecting approvals. To improve accountability, experts advocate increasing public access to environmental information, NGO involvement, and citizen litigation tools [23,24,25].

The prior analysis details the procedural aspects of public participation; however, a more comprehensive understanding necessitates an examination of the socio-political contexts that influence its effectiveness. In Laos, restricted participation is not simply a procedural deficiency but rather a consequence of its centralised political framework, characterised by constrained civil society spaces and heavily state-mediated access to information. In China, ‘token participation’ emerges from a governance model that emphasises social stability and top-down control, directing public input into managed, non-confrontational avenues. In both countries, public participation functions primarily as a tool within a state-directed development framework rather than as an independent governance mechanism. Enhancing its meaningfulness requires more than just legal reforms; it necessitates shifts in political culture towards greater transparency and the legitimization of public dissent in environmental decision-making, as indicated in studies on civic engagement [26,27,28].

4.4. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

These countries need EIAs for projects that may significantly impact the environment, but their implementation scope differs. Laos’ Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) method combines EIAs and SIAs. Developers must assess ecosystem, community, and public health impacts in ESIA reports. Processes are confusing, and monitoring following project approval is insufficient. Hydropower and mining, which fuel Lao economic growth, often degrade because to inadequate follow-up assessments and restoration financing. Chinese EIAs include strategic environmental assessments (SEAs) for regional planning and industrial strategy, making them more thorough. Regular audits impose post-approval monitoring, and projects that violate EIA criteria are suspended. China demands quarterly environmental indicator reporting and local environmental bureau verification.

China uses scientific modelling, GIS-based risk mapping, and cumulative effect assessments in its EIA process, while Laos uses qualitative evaluations. Laos cannot adequately foresee long-term environmental effects because of this difference. Table 1 shows how the big electricity projects in China and Laos affect the environment. It shows that projects in Laos like Nam Theun 2 and Xayaburi destroy more trees, kill more species, and change the quality of the water more than China’s Three Gorges and Xiaowan dams. Ten percent of trees are cut down for Nam Theun 2 and eight percent of trees are cut down for Xayaburi. On the other hand, only five percent of trees are cut down for Three Gorges and four percent are cut down for Xiaowan. These differences show how different countries’ hydropower growth projects handle the environment in different ways [45,46].

The two EIA processes differ in two important ways: the range and depth of their impact assessments. Although assessments are necessary for projects with major environmental effects in both nations, China’s procedure uses more sophisticated technical techniques and includes strategic environmental assessments (SEAs) for regional planning.

Table 1 shows a comparison of important hydropower projects using data that has been standardised from current Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) reports and peer-reviewed publications. This is to show the different environmental effects. We estimate the percentages for deforestation, biodiversity loss, and water quality change from these published sources to directly compare the impact magnitude.

Data on the impact of biodiversity loss and forest loss in Laos (Nam Theun 2) comes from the project’s official ESIA and later monitoring studies that were examined by the World Bank (Campbell, 2011) [38]. The substantial reservoir area directly correlates with the high percentage of deforestation.

Laos (Xayaburi): The project’s ESIA and independent studies on Mekong hydropower have combined to provide impact figures that emphasise environmental harm and silt trapping (Middleton, 2022) [41].

China (Three Gorges & Xiaowan): The Chinese government gathers information from peer-reviewed analyses and environmental impact statements. Although the ecological effects of the projects were significant, they were lessened by investing in mitigation infrastructure and conducting more thorough pre-construction modelling (Hennig et al., 2016) [43].

The fact that these numbers are standardised measurements for comparison is important to remember. The percentage of forest cover lost in the project’s direct reservoir and construction zone is shown by the symbol “deforestation”. The impacted terrestrial species richness is estimated using “Biodiversity Loss”. Even though the data is imprecise, it is evident that projects in Laos, which have a less stringent EIA procedure, routinely report greater relative environmental impacts than their Chinese counterparts. This highlights the practical repercussions of disparate assessment capabilities.

4.5. Compliance and Cross-Border Cooperation

Both nations understand that environmental governance requires cooperation. Cross-border investment in Laos’ mining and hydropower sectors has increased since CAFTA was established. Therefore, environmental governance must handle transboundary consequences and shared ecosystems. Due to China’s participation in Lao infrastructure projects, bilateral negotiations on EIA standards, transparency, and coopertive oversight have begun. China has made headway in aligning its EIA standards with international best practices, but resource constraints and institutional expertise have hampered implementation in Laos. Regional cooperation, data exchange, and law harmonisation could boost both nations’ environmental performance [47,48].

The relationship between cross-border cooperation and compliance is becoming more and more important, especially in light of China’s significant investment in Laos’ vital industries. This collaboration has progressed to specific frameworks from broad declarations [33,34,35]. The Memorandum of Understanding on Environmental Cooperation between China and Laos is a good example since it creates a formal forum for discussion on environmental governance, including EIA criteria. Additionally, both countries participate in the “Lancang-Mekong Environmental Cooperation Centre”, which is part of the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) mechanism. Its goal is to share best practices in environmental management and encourage green development, which has a direct impact on transboundary project assessments (Hongzhou, Z. (2022)) [49].

Project-level criteria are starting to take shape as a result of these agreements. As an example of a new type of collaborative oversight, significant Chinese-funded projects in Laos, including the China-Laos Railway, have been subject to agreed-upon environmental and social safeguards as well as shared environmental monitoring committees [41,50]. These tangible memorandums and cooperative bodies offer a fundamental framework for coordinating EIA standards, enhancing transparency, and controlling the joint environmental impact of their economic partnership, even though implementation is still developing and resource-related issues continue to occur [37,38,39].

4.6. Summary of Findings

When it comes to Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), Laos and China are very similar from a legal standpoint. For example, before approving a project, both countries require EIAs to be completed. Additionally, public consultation is highly valued in both systems, and environmental compliance is ensured through post-approval monitoring mechanisms. But in terms of structure and enforcement, the two regimes couldn’t be more different. Laos’s EIA system is still in its early stages, marked by poor coordination across agencies, low administrative capacity, and relatively light consequences for non-compliance; in contrast, China’s system is more institutionalised and has a clearly defined legal framework and strong enforcement mechanisms. Problems with bureaucratic red tape, conflicting laws, and meddling from local governments that put profit before the environment are major obstacles to Laos’s efforts to put environmental protection into practice [40,41,42]. But China has a far loftier environmental policy agenda, and the country’s enforcement procedures must be in perfect harmony with it. Although both nations recognise the significance of public involvement in the EIA process, there has been very little genuine interaction. Public engagement in China is formalised but often procedural, with little impact on final project decisions, in contrast to Laos’s insufficient transparency and frequent lack of access to important environmental information [43,44,45]. To improve the efficiency of their EIA systems and attain sustainable development in the long run, Laos and China must work together to strengthen cross-border cooperation, use EIA tools that are more data-driven and quantitative, and incorporate environmental performance indicators into policy and governance evaluations [47,48,49,50].

5. Conclusions

Laos and China’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) legislative systems were compared in this study, which concluded that while both systems had commonalities, there were also notable distinctions in terms of structure, enforcement, and public involvement. According to the research, even while both countries acknowledge EIA as a crucial tool for advancing sustainable development, there is a significant difference in their institutional maturity, administrative competence, and actual implementation. The results highlight the significance of pre-assessment, public consultation, and post-implementation monitoring, as well as the fact that EIA procedures are legally mandated in both Laos and China prior to project approval. Nevertheless, the EIA system in China is more developed and established, with a robust legislative framework that guarantees accountability and procedural rigour. This structure is based on the Environmental Protection Law and the Environmental Impact Assessment Law. On the flip side, inconsistent enforcement, a lack of coordination among agencies, and fragmented legislation continue to impede the Lao EIA system, despite its good intentions. Although Laos’s principal authority is the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE), obstacles to effective implementation include a lack of resources, inadequate training, and overlapping jurisdictions. From 2020 to 2022, shows how Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in different areas between Laos and China compared. In all areas, China gets a lot more foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, China gets $1,200,000,000 in FDI for hydropower, while Laos only gets $300,000,000 USD. In the same way, China’s Mining, Infrastructure, and Agriculture sectors get a lot more investments. This shows that China has a stronger EIA system and policies that encourage investment. Laos, on the other hand, has less FDI in these areas, which is a sign of problems with environmental management and investor trust.

Although Laos and China have a fundamental commitment to EIA protocols, this comparative analysis indicates that there is a significant institutional maturity gap between their systems. The difference is not only legal but also fundamental, stemming from China’s stronger administrative capabilities and better-established (although frequently contested) enforcement systems in comparison to Laos’s difficulties with basic resources and coordination. Patterns of investment reflect the differences in results. In contrast to Laos, China draws substantially more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in industries like mining and hydropower, as shown by World Bank and national investment reports (2020–2022). This trend indicates investor confidence in China’s more predictable, albeit imperfect, regulatory environment.

The theoretical implication of this study is that a robust Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system arises from a confluence of institutional authority, political will, and legislative design, rather than solely from legal frameworks. This framework should be expanded upon in future studies to perform in-depth case studies of particular China-Laos joint ventures, investigate how power dynamics in investment agreements affect EIA adherence, and quantitatively test the relationship between long-term project sustainability and the strength of public participation mechanisms.

Another common deficiency is the level of public involvement. Meaningful engagement is still mostly symbolic, despite the fact that both nations acknowledge its importance in legislation. Citizens are discouraged from actively participating in environmental decision-making due to the lack of openness and legal protection in Laos. Although procedural engagement is guaranteed under Chinese legal frameworks through public disclosure and hearings, this participation seldom has any impact on the final approvals of projects. Improving accountability in both institutions requires a stronger public involvement through more openness, education, and participatory processes.

5.1. Acknowledgement of Limitations

This study has a few drawbacks. First, there were limitations on the availability of current government reports and information on EIA enforcement in China and Laos, which could have an impact on how thorough the research is. Furthermore, because of different reporting requirements and degrees of transparency in the two nations, the information obtained from case studies and official publications may be biassed by nature. There is a dearth of institutional capacity data, especially for Laos, because the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE) frequently lacks adequate monitoring resources, which may affect how well EIA enforcement is evaluated. The results should be interpreted with these factors in mind. Notwithstanding these drawbacks, the report highlights opportunities for environmental governance reform and offers insightful information about the EIA frameworks of both countries.

5.2. Recommendations for Improvement

The following suggestions are made to improve the efficiency of EIA systems in both nations:

I. Strengthening Enforcement Mechanisms: In order to discourage infractions and guarantee compliance with environmental standards, Laos and China should think about implementing stronger penalties for failing to comply with EIA laws.

II. Enhancing Public Participation: In order to discourage infractions and guarantee compliance with environmental standards, Laos and China should think about implementing stronger penalties for failing to comply with EIA laws.

III. Capacity Building: Improving the quality and consistency of assessments and monitoring operations can be achieved through capacity building initiatives that provide training and resources to organisations responsible for environmental impact assessments (EIA).

IV. International Collaboration: Laos and China can improve their environmental impact assessment (EIA) frameworks and advance sustainable development through international collaboration, which includes participating in regional cooperation and studying other nations’ best practices.

5.3. Future Recommendations

5.3.1. Strengthen Enforcement Mechanisms

In order to make EIA enforcement more successful, both nations should increase fines for noncompliance and give environmental agencies more autonomy. China needs to make sure that laws are actually enforced, and Laos needs to make sure that their monitoring system is well-funded, transparent, and integrated.

5.3.2. Enhance Institutional Capacity

Governments around the world, including Laos, need to put money into training programmes, technology, and other resources so that environmental impact assessments are more accurate. Another way to make people more accountable is to set up environmental courts or authorities.

5.3.3. Promote Meaningful Public Participation

Both countries should establish systems to promote early and ongoing community involvement in order to promote meaningful public participation. Chinese public hearings should be more than just a formality; they should be opportunities for meaningful discourse that impact policymaking; Laos should bolster its legal protections for public participation and access to information.

5.3.4. Encourage Cross-Border Cooperation

With their increasing economic connections, China and Laos should cooperate together on transboundary environmental management and exchange best practices through regional cooperation programmes like the China-ASEAN collaboration.

In conclusion, Laos and China have made good progress in developing EIA frameworks for sustainable development. Truly effective environmental governance requires enforcement, transparency, and engagement beyond legal formalities. Both countries may improve their EIA procedures by learning from each other and aligning their systems with worldwide best practices, ensuring that economic success and environmental protection go hand in hand for a sustainable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.V.; methodology, O.V.; validation, H.N.V.; formal analysis, S.K.S.; investigation, O.V.; resources, H.N.V.; data curation, O.V. and H.N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.; writing—review and editing, M.W.; visualization, S.K.S.; supervision, M.W.; project administration, M.W.; funding acquisition, M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnson, T. Public participation and dispute resolution in China’s EIA. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 82, 106379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; He, J.; Bao, C. Public participation modes in China’s environmental impact assessment process: An analytical framework based on participation extent and conflict level. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 84, 106400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Assessing Environmental Impacts: A Global Review of Legislation; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Burdett, T. Community engagement, public participation and social impact assessment. In Handbook of Social Impact Assessment and Management; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 308–324. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, P.; Riegner, M. The World Bank’s Environmental and Social Safeguards and the evolution of global order. Leiden J. Int. Law 2019, 32, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phimphanthavong, H. The determinants of sustainable development in Laos. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2014, 3, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- He, X. Mitigation and adaptation through environmental impact assessment litigation: Rethinking the prospect of climate change litigation in China. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2021, 10, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashmore, M. The role of science in environmental impact assessment: Process and procedure versus purpose in the development of theory. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.; Morrison-Saunders, A.; Pope, J. Sustainability assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeva, M.; Maidell, M.; Kotta, J.; Peterson, A. An Eco-GAME meta-evaluation of existing methods for the appreciation of ecosystem services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C.; Casasanta Mostaço, F.; Jaeger, J.A. Lack of consideration of ecological connectivity in Canadian environmental impact assessment: Current practice and need for improvement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2022, 40, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Jun, L.; Hongge, T.; Chengchen, Y.; Jiang, H.; Pan, T. Wheat-Crab Cultivation Results in Earlier Maturation and Better Health of Female Crabs (Eriocheir Sinensis). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2396. [Google Scholar]

- Glasson, J. Follow-up: Post-decision learning in EIA. In Handbook of Environmental Impact Assessment; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 198–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q. China is actively implementing health impact assessment legislation. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1531208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chali, A. Assessment of Environmental Impacts of Kuyyu Cement Factory, Kuyyu District, North Showa, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. Doctoral Dissertation, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lao and China Governors, B.O. Development Effectiveness Review; Asian Development Bank—ADB: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Russel, D.R.; Berger, B. Navigating the Belt and Road Initiative; Asia Society Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, T.S.; Fischer, T.B. Quality of environmental impact assessment systems and economic growth in countries participating in the belt and road initiatives. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2020, 38, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; He, D.; Phousavanh, P. Case study: Experience sharing in Laos. In Balancing River Health and Hydropower Requirements in the Lancang River Basin; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Nickum, J.E.; Brooks, D.B.; Turton, A.; Esterhuyse, S. (Eds.) The Water Legacies of Conventional Mining; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kittikhoun, A.; Staubli, D.M. Water diplomacy and conflict management in the Mekong: From rivalries to cooperation. J. Hydrol. 2018, 567, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Diduck, A.P. Reconceptualizing public participation in environmental assessment as EA civics. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 62, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B.D.; Vu, C.C. EIA effectiveness in Vietnam: Key stakeholder perceptions. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Therivel, R. Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, T.C.; Doherty, S.J.; Fahey, D.W.; Forster, P.M.; Berntsen, T.; DeAngelo, B.J.; Flanner, M.G.; Ghan, S.; Kärcher, B.; Koch, D.; et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 5380–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carew-Reid, J. The Mekong: Strategic environmental assessment of mainstream hydropower development in an international river basin. In Routledge Handbook of the Environment in Southeast Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 352–373. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saming, C.; Kaewrungrueng, C.; Kakhai, P. Legal Issues of Mekong Water Allocation: The Case Study of Thailand. In Proceedings of the International Academic Multidisciplinary Research Conference, Beijing, China, 18–20 January 2025; pp. 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Phaengsuwan, A. The Effectiveness of the Laotian EIA System in the Context of Sustainability and Hydropower Development. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Caro-Gonzalez, A.L.; Nita, A.; Toro, J.; Zamorano, M. From procedural to transformative: A review of the evolution of effectiveness in EIA. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 103, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa Rodríguez, M.; Aguilera Flores, M.M.; Ávila Vázquez, V.; Sánchez Mata, O.; Chávez Soto, M.J. Environmental impact assessment before and after implementing mitigation and prevention measures on two final waste disposal sites. Case study: Zacatecas, Mexico. Rev. Int. De Contam. Ambient. 2025, 41, 55236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.J. Sustainability Assessment: Pluralism, Practice and Progress; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Morgan, R.K.; Cashmore, M. Environmental impact assessment of projects in the People’s Republic of China: New law, old problems. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2003, 23, 543–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells-Dang, A.; Soe, K.N.; Inthakoun, L.; Tola, P.; Socheat, P.; Van, T.T.; Chabada, A.; Youttananukorn, W. A political economy of environmental impact assessment in the Mekong Region. Water Altern. 2016, 9, 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, E. Environmental impact assessment: ‘setting the law ablaze’. In Research Handbook on Fundamental Concepts of Environmental Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 422–448. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, M.T.; Aung, M.M.; San, S. V Women’s rights and contributions to the enjoyment of the human right to a healthy environment. Prosperous Green Anthr. 2020, 54, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Resource, N. Lao PDR Development Report 2010; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, L. The Use of Environmental Impact Assessment in Laos and Its Implications for the Mekong River Hydropower Debate; Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2011. Available online: https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/3655 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Wu, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, J. China’s environmental impact assessment reform from the perspective of public-private collaboration. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 100, 107089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, H.N.; Borja, A.; Fonseca, V.F.; Harrison, T.D.; Teichert, N.; Lepage, M.; Leal, M.C. Fishes and estuarine environmental health. In Fish and Fisheries in Estuaries: A Global Perspective; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 332–379. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, C. The Political Ecology of Large Hydropower Dams in the Mekong Basin: A Comprehensive Review. Water Altern. 2022, 15, 251–289. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Chang, I.S. Environmental Management in China; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig, T.; Wang, W.; Magee, D.; He, D. Yunnan’s fast-paced large hydropower development: A powershed-based approach to critically assessing generation and consumption paradigms. Water 2016, 8, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M. Annual review of Chinese environmental law developments: 2017. Environ. Law Report. News Anal. 2018, 48, 10389. [Google Scholar]

- Buhmann, K.; Fonseca, A.; Andrews, N.; Amatulli, G. Meaningful stakeholder engagement: The concept, practice and governance. In The Routledge Handbook on Meaningful Stakeholder Engagement; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dogmus, Ö.C. Water Politics and the On-Paper Hydropower Boom: Power, Corruption, and Sustainability in Emerging Economies; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Xiao, Y.; Rong, B.; Zhang, P. Evaluating the land-sea coordination in Chinese coastal cities from an integrated and water eco-environmental perspective. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 1501–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahatab, S.; Debata, A. The Role of Public Participation in Shaping Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) in India: A Review. Int. J. Integr. Res. 2025, 3, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Cross-Border Resource Governance in China and the Role of the Provincial Governments: A Three-part Case Study; National University of Singapore: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Olszynski, M. Monitoring, Follow-Up, Adaptive Management, and Compliance in the Post-Decision Phase. Impact Assess. Act, 2020; forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).