Abstract

The intensification of urban heat islands in high-density coastal slope areas poses significant challenges to sustainable development. From the perspective of sustainable urban design, this study investigates adaptive greening strategies to mitigate thermal stress, aiming to elucidate the key microclimate mechanisms under the combined influence of sea breezes and complex terrain to develop sustainable solutions that synergistically improve the thermal environment and energy efficiency. Combining field measurements with ENVI-met numerical simulations, this research systematically evaluates the thermal impacts of various greening strategies, including current conditions, lawns, shrubs, and tree configurations with different canopy coverages and leaf area indexes. During summer afternoon heat episodes, the highest temperatures within the building-dense sites were recorded in unshaded open areas, reaching 31.6 °C with a UTCI of 43.95 °C. While green shading provided some cooling, the contribution of natural ventilation was more significant (shrubs and lawns reduced temperatures by 0.23 °C and 0.15 °C on average, respectively, whereas various tree planting schemes yielded minimal reductions of only 0.012–0.015 °C). Consequently, this study proposes a climate-adaptive sustainable design paradigm: in areas aligned with the prevailing sea breeze, lower tree coverage should be maintained to create ventilation corridors that maximize passive cooling through natural wind resources; conversely, in densely built areas with continuous urban interfaces, higher tree coverage is essential to enhance shading and reduce solar radiant heat loads.

1. Introduction

It is widely recognized that the urban heat island (UHI) effect, a phenomenon inherent to urbanization, now poses a critical challenge to sustainable societal development [1]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Sixth Assessment Report underscored that with a global surface temperature 1.1 °C above pre-industrial levels (1850–1900), warming was projected to surpass the critical threshold of 1.5 °C in the near term (2021–2040) [2]. By amplifying the frequency and intensity of heatwaves, the UHI effect compounds the health risks faced by urban populations [3]. This phenomenon contributes directly to heat-related morbidity and mortality [4,5], while simultaneously driving increased energy consumption.

Located along the extensive eastern coastline of China, Qingdao in Shandong Province is a city of sloped terrain. It is characterized by extensive urban construction, polycentric and high-density development, and an ever-increasing intensity of coastal development. The characteristic urban morphology of high-density coastal cities could block the inland penetration of cool sea air during summer, a phenomenon where the mitigating effect on heat is significantly reduced. This serves as a direct driver for the prolonged UHI effect observed in Shenzhen, which has extended up to seven months [6]. The central urban area of Dalian likewise confronts considerable environmental challenges, marked by a severe UHI effect and elevated levels of air pollution [7]. It is imperative to conduct thermal environment studies in sloped coastal cities characterized by high-intensity development and to explore pathways for mitigating the UHI effect. This research is essential to meet the practical demands of urban growth and ecological livability.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the UHI effect could be effectively mitigated through various strategies, including optimized greening [8], improved water conditions [9], the implementation of green roofs and facades [10,11], the use of advanced building materials [12], and the optimization of underlying surfaces [13]. Green spaces influence the urban microclimate through cooling, shading, humidity regulation, and the alteration in wind speed and direction, which can even induce local wind circulation. A study in Germany found that summer grassland reduced the diurnal average physiological equivalent temperature (PET) by 1 °C [14]. A study in Hong Kong demonstrated that a single tree (Ficus microcarpa) reduced the mean daytime PET and Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) by 3.9 °C and 2.5 °C, respectively [15]. However, many scholars have proved that the cooling effect of green space can be determined by a variety of external urban environmental factors (such as the urban climate, building density, building height, impermeable surface, etc.), and this effect varies greatly [16,17]. Dense building configurations impede air circulation, reduce shortwave radiation absorption, and diminish longwave radiation loss, thereby suppressing heat dissipation. Therefore, the cooling effect of plants in densely built areas may be inhibited [18]. In addition, due to its high heat capacity and low thermal conductivity, water influences the urban microclimate through evaporative cooling, temperature stabilization, land–water breeze formation, and humidity regulation. The blue space of the city can produce an urban cold island and have a cooling effect on the surrounding areas. A study in India showed that blue space could reduce the Land Surface Temperature (LST) of the surrounding urban areas by 3.01 °C in summer and 1.25 °C in winter [19]. A study in Nanjing demonstrated that rivers provide a cooling effect extending over 0.68 ha during daytime and 0.78 ha at night to adjacent residential areas in summer, with average temperature reductions of 0.98 °C and 0.17 °C, respectively [20]. In the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao greater area, a study revealed a contrasting phenomenon: a night warming effect from the ocean was observed in nine of the eleven coastal cities [21]. In the same city as the present study, our research group previously demonstrated that in coastal open spaces, introducing trees could reduce the ambient temperature on flat terrain, whereas the opposite effect was observed on sloped terrain [22,23].

The objective of this study was to examine the cooling effects of greening strategies within high-density urban built-up areas under the combined influence of mountain and sea effects. A coastal high-density residential area in Qingdao, an eastern Chinese city, was selected as the study site. The ENVI-met model was employed to simulate the microclimatic effects of vegetation within a high-density built-up area under the influence of slope terrain and coastal topography. A quantitative analysis of thermal comfort was conducted to elucidate the mechanisms involved, leading to the proposal of greening strategies aimed at thermal environment optimization. Drawing upon empirical data from the selected site, the findings of this study are intended to inform and advance sustainable urban development practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

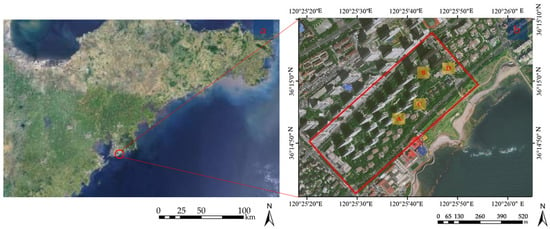

Qingdao is a coastal city in eastern China, with longitude 119°30′–121° E and latitude 35°35′–37°09′ N (Figure 1). The average maximum temperature in the urban area during summer is between 23.0 and 32.0 °C, and the average minimum temperature during winter is between −7.0 and 1.0 °C [24]. A southeast wind prevails in summer, and a northwest wind prevails in winter. The average wind speed in urban areas along the southeast coast ranges from 3.4 to 5.4 m/s in summer [25]. The study area is situated in a representative urban zone, bordered by the sea to the southeast and characterized by a general slope gradient of 3–7%. The site is occupied by high-density residential buildings of varying heights (12–140 m), while the green infrastructure coverage within the area is about 40%. The research was conducted in a locally typical coastal sloped area, defined as a high-density built-up environment, serving as a representative case for the thermal conditions. The selection of the measurement points should fully consider the diversity of building types and vegetation coverage in the survey site. Finally, four typical locations of a forested area between multi-story buildings, a forested area between high-rise buildings, an unshaded area between multi-story buildings, and an unshaded area between high-rise buildings were determined to accurately analyze the specific impact of the difference between building and vegetation coverage on the microenvironment.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the survey site, depicting the locations of the four measurement points: (A) a forested area between multi-story buildings, (B) a forested area between high-rise buildings, (C) an unshaded area between multi-story buildings, and (D) an unshaded area between high-rise buildings. (a) Schematic diagram of coastline in the study area, (b) Overall plan of the study area.

2.2. Research Method

2.2.1. Research Steps

This study investigates mitigation measures for the UHI effect in high-density built-up areas within coastal slope terrain. It aims to identify the dominant factors and mechanisms governing the local microclimate under the combined influence of sea and topographic forcing. Consequently, the study seeks to derive greening strategies suitable for high-temperature summer conditions, with the ultimate goal of achieving improved thermal comfort. The specific research procedure is outlined as follows:

- a.

- Field measurements and numerical simulations of the air temperature, relative humidity, and solar radiation were conducted. The monitoring points were systematically selected to capture the site’s geometric characteristics, encompassing locations under tree canopies in both multi-story and high-rise building districts, an open area within the built-up zone (devoid of vegetation), and an external roadway;

- b.

- ENVI-met 5.5 was utilized for the modeling, simulation, and validation of the study area;

- c.

- A series of simulations was performed to study the thermal effects and mechanisms of different greening strategies in the high-density coastal slope area. The strategies included the following:

- Baseline (current condition),

- Lawn,

- Shrubs,

- Increased/decreased tree canopy cover,

- Enhanced Leaf Area Index (LAI).

The differences of the Ta and UTCI (including average value and extreme value) under each greening strategy were compared and analyzed to form the optimal strategy;

- d.

- A comparative analysis was performed between the optimized design scenarios simulated with ENVI-met and the baseline data to evaluate the mitigation effect on the UHI.

2.2.2. On-Site Measurement

The validity of the software simulation results was verified through on-site measurements. The model parameters were then calibrated based on a comparative analysis of the collected data. The measurement was carried out during a typical summer day (8 August 2022). The date selection was from the typical meteorological year data from the “China Standard Weather Data for Building Thermal Environment Analysis”, which could represent the local long-term average climate conditions [26]. The two consecutive days before the measurement day and the measurement day were sunny. A field campaign was carried out with Kestrel NK 5500 and TES-1333R to monitor the meteorological parameters—including the air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation—at 1.5 m above ground level. The measurements were conducted at four locations within the site. Data were automatically recorded at 5 s intervals within a 5 min window surrounding each hour from 00:00 to 23:00. The hourly average values were subsequently calculated (Figure 1). A 27 h simulation was conducted, starting at 21:00 on the preceding day, which included a model warm-up period of 3 h.

In terms of plants, Pinus thunbergii and Koelreuteria paniculata are widely selected as representative species in the Qingdao coastal high-density built-up area. Pinus thunbergii, with its strong resistance to sea tide, salt spray, and barren soil, constitutes the regional ecological framework; Koelreuteria paniculata is the best choice for deciduous trees, because of its environmental resistance and symbolic seasonal changes. The LAI of Koelreuteria paniculata and Pinus thunbergii was measured using a plant canopy analyzer (LAI-2200 (LI-COR Environmental, Lincoln, NE, USA)). Subsequently, the Leaf Area Density (LAD) at corresponding heights was calculated for plants with given height, width, and trunk height values (Table 1) using Formula (1).

where is the Leaf Area Index, is the Leaf Area Density, is the height interval of a canopy layer (in meters), and is the total canopy height (in meters).

Table 1.

Plant model parameters.

2.2.3. Simulation and Validation Methods

The ENVI-met model is defined as a grid-based three-dimensional system for simulating the urban microenvironment. The simulations are performed by resolving the interactions between atmosphere, vegetation, buildings, and materials at configurable horizontal resolutions (0.5–10 m) and temporal steps (down to 10 s). The model requires the specification of physical parameters for buildings, underlying surfaces, and vegetation, along with the input of meteorological data, including the wind speed/direction, initial air temperature, relative humidity, and cloud cover. Air temperature (Ta) was the most frequently evaluated meteorological variable, followed by the relative humidity (RH), wind speed (WS), and solar radiation (SR) [27].

The accuracy of the model in simulating the air temperature and relative humidity was quantitatively evaluated using the following metrics: Index of Agreement (d), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Systematic Root Mean Square Error (RMSEs), and Unsystematic Root Mean Square Error (RMSEu). The value of d, which measures the probability of agreement between the simulated and measured values (i.e., the model’s predictive accuracy), ranges from 0 to 1, with d = 1 denoting perfect concordance. The RMSEs represents the component of the total error caused by specific recurring sources, such as instability in boundary conditions within the ENVI-met model—an issue that can be addressed by configuring nested grids. The RMSEu is usually caused by the influence of model parameters, climate conditions, etc. The mathematical definitions of the evaluation metrics are provided as follows [28,29,30]:

where is the sample size, denotes the simulated value, represents the the observed value, and is the vector of the simulated value.

2.3. Model Parameters

The three-dimensional model was established in the ENVI-met Space file, incorporating the geometry of buildings, vegetation, and underlying surfaces. The model grid was configured with 119 × 120 × 41 cells and a constant resolution of 5 m. Furthermore, a nesting grid count of 10 was utilized. The specific parameter configurations are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

ENVI-met simulation initial condition settings.

2.4. Simulation Verification

The model’s performance was validated by comparing the simulated Ta, RH, and SR at 1.5 m height against the measured data from four monitoring sites. The value of d exceeded 0.69 at all locations. The RMSE of the simulated Ta was 0.4–0.9 °C, the RMSEs was 0.39–0.87 °C, and the RMSEu value was 0.05–0.55 °C. The RMSE of the simulated RH was 1.2–4.3%, the RMSEs of RH was 1.18–4.04%, and the RMSEu of RH was 0.24–3.58%. The RMSE value of the simulated SR was 32–57 w/m2, the RMSEs value of SR was 10.19–53.13 w/m2, and the RMSEu value of SR was 0.31–4.67 w/m2. According to the statistics of 130 published scientific papers from 2006 to 2019 [31], in the numerical simulation of microclimates by ENVI-met, the RMSE of Ta, RH, and SR were 0.4–3.7 °C, 0.76–13% and 16–106 w/m2 respectively, which indicated that the error of this study was within the acceptable range. These results demonstrated consistent trends between the simulated and observed values, indicating the model’s reliable predictive capability for site-specific microclimate conditions. However, it must be noted that the relatively higher RMSE associated with the relative humidity simulation introduces significant uncertainty into the UTCI results, due to the index’s high sensitivity to humidity variations.

3. Results

3.1. The Effects of Ocean and Terrain on Site Microclimate

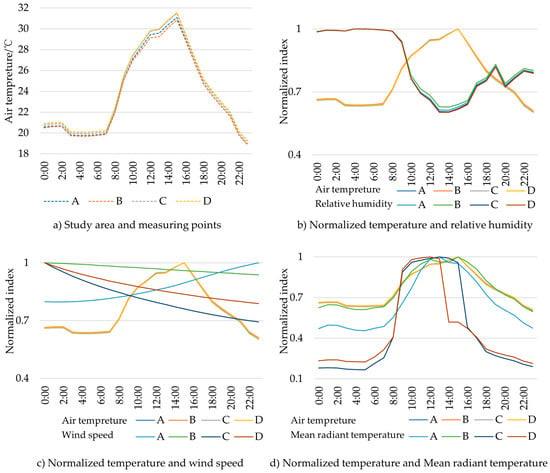

This section examined the spatial profiles of air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and mean radiant temperature from a field transect measured at 15:00 on the existing site (Figure 2a). The area analyzed in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 was the pedestrian height of densely built-up areas, which was the height of z = 17.50 m in the model. The selection of this height was based on the unique urban morphological characteristics and atmospheric physical processes in the region. This area was 16 m above sea level, with dense buildings (including 47 of 51 buildings), forming a typical urban canopy structure. In such a high-density built environment, the near surface thermal field was dominated by the canopy scale energy exchange process. The height layer of 17.50 m was the key role of the urban canopy—it could not only effectively avoid the local interference of the ground layer (such as direct solar radiation, surface material heterogeneity, etc.) but also completely capture the heat exchange process between the building facade and the street space. The thermal environment parameters obtained from this height could characterize the core mechanism driving the distribution of thermal field in the whole canopy; so, it could be used as a representative area of the thermal environment at pedestrian height. In terms of the diurnal temperature patterns, the two unshaded sites (C and D) exhibited consistently higher temperatures than the two tree-shaded sites (A and B). Despite being located among high-rise buildings, Site B recorded the lowest temperatures among all observation sites during the warmer daytime period (10:00–16:00). The data of Ta, RH, WS, and Mean Radiant Temperature (Tmrt) from the four observation points were normalized to clarify the correlations between the temperature and the other microclimatic variables (Figure 2b–d). The Ta decreases with the increase in RH, increases with the increase in Tmrt, and has no obvious rule with the change in WS. It was noteworthy that, at the two tree-shaded sites, the Ta at pedestrian height closely followed the trend of Tmrt. In contrast, at the unshaded sites C and D, a noticeable time lag in Ta decrease was observed following a rapid drop in Tmrt. This phenomenon could be potentially attributed to the continuous heat release from the surface paving, surrounding buildings, and vegetation.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of Ta, RH, WS, and Tmrt at the 17.50 m level across the current site at 15:00: (A) a forested area between multi-story buildings, (B) a forested area between high-rise buildings, (C) an unshaded area between multi-story buildings, and (D) an unshaded area between high-rise buildings.

It was evident from the distribution of Ta that the hottest area coincided with the densely built-up area, with the maximum temperature across the site peaking at 31.6 °C (Figure 3a). Cool air from the ocean could enter the site relatively unobstructed in regions of low building density, while denser urban fabric hindered this ventilation. Along streets aligned with the sea breeze direction, cool air also penetrated inland with relative ease. Conversely, the distribution of RH exhibited a negative correlation with Ta (Figure 3b). A maximum RH of 64.49% was recorded in the inlet zone facing the oncoming sea breeze, an area characterized by low Ta and high RH. The vegetation significantly enhanced the humidity levels. In contrast, non-vegetated areas enclosed by buildings were characterized by high temperatures and low humidity. Elevated Tmrt were observed in the southwestern part of buildings, peaking at 75.07 °C (Figure 3c). Additionally, high Tmrt were observed in unshaded paved zones, with recorded values of up to 62.04 °C. A significant positive correlation was observed between the distribution of Ta and Tmrt. This was primarily attributed to shading and the albedo of ground surface. Areas with shadows and those with lower surface reflectivity consequently developed lower radiant temperatures. Regarding the wind field, the windward slopes significantly reduced the WS on the building’s windward facade and in upslope areas. Additionally, both buildings and vegetation contributed to WS reduction. Areas downwind of the sea breeze-aligned streets and certain building corners developed significant turbulence with enhanced wind speed. However, a temperature reduction was observed only within the street areas (Figure 3d). This finding further indicated that the ventilation corridors associated with green spaces and water were more effective in maintaining the transfer of cool air [32].

Figure 3.

(a) Ta distribution of the current scene at pedestrian height; (b) RH distribution of the current scene at pedestrian height; (c) WS distribution of the current scene at pedestrian height; (d) Tmrt distribution of the current scene at pedestrian height.

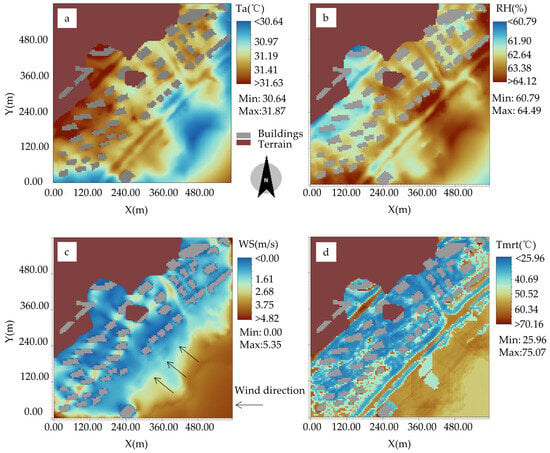

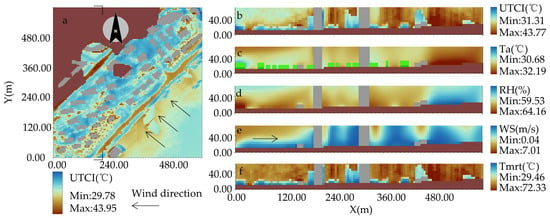

In the current scenario, the higher UTCIs were located in the low-rise buildings at the front and the non-vegetated areas within the rear high-rise building clusters, peaking at 43.95 °C. Additional thermal hotspots were characterized by their proximity to buildings and a lack of street-tree shading, with the most pronounced effects observed along roads oriented perpendicular to the dominant wind (Figure 4a). By examining a cross-sectional profile of the site, the influence of various environmental factors on the UTCI could be more clearly discerned. Lower UTCIs were observed in tree-covered areas and within shadows cast by buildings (Figure 4b). Areas with elevated UTCIs and Ta coincided with the locations of building facades near the cross section. Furthermore, higher UTCIs were observed near the ground level in areas devoid of buildings and vegetation (Figure 4c). A pronounced inverse relationship between the RH and UTCI was observed in the open ends of the transect, while this correlation became weaker or insignificant in zones with dense buildings and vegetation (Figure 4d). In terms of the wind field, both buildings and vegetation along the transect significantly reduced the WS. However, no clear influence of the WS on the UTCI was detected (Figure 4e). Finally, our observations indicated that the spatial distribution of the Tmrt closely resembled that of the UTCI (Figure 4f). In summary, the solar radiation was the dominant factor influencing UTCI on the coastal slope during summer afternoons. Effective shading strategies could significantly reduce the site-level UTCI. Tree planting exerted a cooling influence on Ta, extending radially to approximately 2–3 times the tree height, and reduced the UTCI at and below the canopy level. However, it induced a warming effect on the UTCI above the canopy.

Figure 4.

(a) UTCI distribution of the current scene at pedestrian height; (b) UTCI distribution at the cutting position; (c) Ta distribution at the cutting position; (d) RH distribution at the cutting position; (e) WS distribution at the cutting position; (f) Tmrt distribution at the cutting position.

Based on the comprehensive analysis of Ta and UTCI, this study revealed the synergy of terrain, wind field, and vegetation system in the coastal slope environment. The results showed that the site slope and buildings jointly controlled the penetration efficiency of the sea breeze: in the area with a low building density and the road corridor parallel to the direction of sea breeze, the cold air could effectively penetrate inland, forming an obvious low temperature zone (2–3 °C lower than the surrounding area) and a UTCI comfort zone; However, the tall and dense buildings had a blocking effect, significantly reducing the wind speed, and led to high Ta accumulation in the leeward area and the roads perpendicular to the dominant wind direction (the maximum Ta was 31.6 °C, and the maximum UTCI was 43.95 °C).

The vegetation in this system had dual regulation characteristics: the average value of the Tmrt and UTCI in the area under the canopy of trees decreased through shading. However, a warmer zone was formed at the top of the canopy due to the absorption of solar radiation. At the same time, the ecological corridor composed of vegetation and water showed significant advantages in maintaining cold air transmission, and its effect was significantly better than the ventilation path formed only by the building interface. It should be noted that, in summer at noon, the solar radiation became the dominant factor in the formation of the thermal environment, and the effect of shading measures (including building shading and vegetation shading) on improving the thermal comfort was significantly better than that of measures relying solely on wind field optimization.

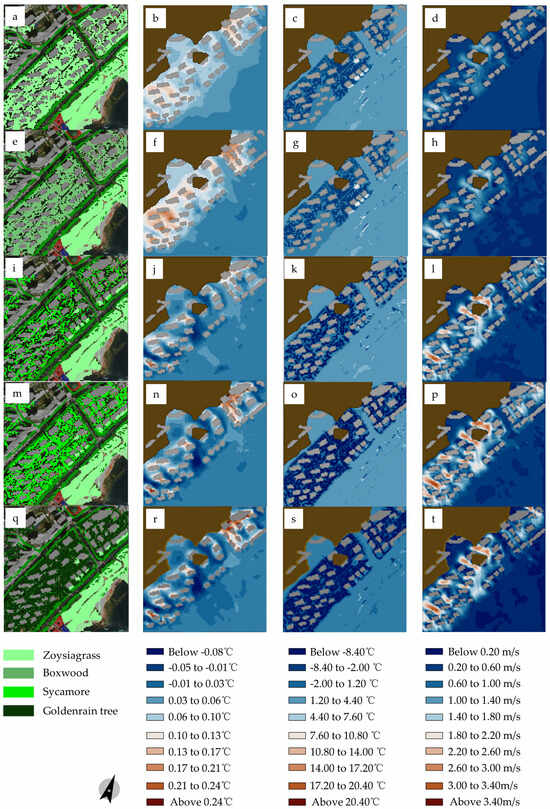

3.2. The Effects of Greening Strategies on Site Microclimate and Optimization Strategies

A comparative microclimatic analysis was conducted for different greening strategies at the pedestrian level (15:00), using the current scenario as a reference. The strategies, implemented within the current vegetation zones, were as follows: lawn (Figure 5a), shrubs (Figure 5e), trees with reduced coverage (Figure 5i), trees with high coverage but low LAI (Figure 5m), and trees with both high coverage and high LAI (Figure 5m). It could be observed that both the lawn and shrubs strategies reduced the site temperature. The maximum Ta reductions were 0.15 °C and 0.23 °C, respectively, with corresponding average reductions of 0.029 °C and 0.031 °C. The cooling effect was primarily observed within building-enclosed areas. The cooling effect of shrubs was slightly more pronounced than that of lawn grass (Figure 5b,f). The superior cooling performance of shrubs stemmed from the higher green volume relative to the lawn, resulting in stronger transpiration-driven cooling and humidification. Among the three tree-scenarios, increased tree planting created a larger spatial extent of warming. Notably, the scenario with higher tree coverage exhibited a more pronounced warming effect (Figure 5i,n). The maximum Ta reductions for the low-coverage trees, high-coverage trees with low LAI, and high-coverage trees with high LAI scenarios were 0.33 °C, 0.33 °C, and 0.32 °C, respectively. The corresponding average Ta reductions were 0.012 °C, 0.014 °C, and 0.015 °C. In terms of the average cooling effectiveness, the shrubs scenario yielded the most effective Ta reduction among all scenarios. The lawn scenario also significantly outperformed all tree-planting scenarios. The cooling effect was comparable across tree-scenarios with different coverage rates. Furthermore, increasing the LAI did not yield a significant additional cooling effect under the same coverage rate. Regarding Tmrt, an increase was observed in all scenarios, with values of 0.93 °C, 1.13 °C, 1.97 °C, 2.89 °C, and 2.91 °C, respectively. However, the performance in reducing the maximum Tmrt followed the order: shrubs > low-coverage trees > high-coverage and high-LAI trees > high-coverage and low-LAI trees > lawn (Figure 5c,g,k,o). Analysis of the turbulent flow conditions revealed that introducing vegetation creates flow obstruction within building gaps. This obstructive effect intensified with increasing tree coverage and LAI. This indicated that the tree canopy impedes the advection of pre-cooled air from the sea and coastal green spaces into the site. Furthermore, in vegetated scenarios, the surfaces absorbed solar radiation and gained heat from the scattering by ground covers; this heat, however, became trapped and could not dissipate rapidly due to the overhead shading and obstruction by the vegetation. In the coastal slope terrain intensive built-up area of this study, the warming effect of trees stemmed from the synergistic effect of the “long-wave radiation trapping” and “sea-breeze circulation blocking” mechanism, and the latter was particularly critical. The key mechanism was that the dense buildings and high canopy trees together increased the surface roughness and seriously dissipated the kinetic energy of the daytime sea breeze. This not only hindered the effective penetration of the sea breeze as a cold source and ventilation channel but also made it difficult to remove heat. It also caused the long-wave radiation heat captured by the canopy to be detained at the pedestrian height near the ground for a long time due to the lack of sufficient advection and turbulence exchange. Therefore, trees not only failed to help introduce a cool sea breeze in this environment but also weakened this most important natural cooling process in coordination with buildings.

Figure 5.

(a) Lawn scenario; (b) Ta difference distribution between the current scenario (CS) and the lawn scenario; (c) Tmrt difference distribution between CS and the lawn scenario; (d) WS difference distribution between CS and the lawn scenario; (e) shrub scenario; (f) Ta difference distribution between CS and the shrub scenario; (g) Tmrt difference distribution between CS and the shrub scenario; (h) WS difference distribution between CS and the shrub scenario; (i) Low tree coverage (LTC) scenario; (j) Ta difference distribution between CS and LTC; (k) Tmrt difference distribution between CS and LTC; (l) WS difference distribution between CS and LTC; (m) High tree coverage with low LAI (HTC-1) scenario; (n) Ta difference distribution between CS and HTC-1; (o) Tmrt difference distribution between CS and HTC-1; (p) WS difference distribution between CS and HTC-1; (q) high tree coverage with high LAI (HTC-2) scenario; (r) Ta difference distribution between CS and HTC-2; (s) Tmrt difference distribution between CS and HTC-2; (t) WS difference distribution between CS and HTC-2.

Based on the above analysis, this study compared the performance of different greening strategies in terms of three key indicators: cooling efficiency, radiation regulation, and ventilation effect. The results showed that the shading benefit of vegetation is limited in the highly densely built-up coastal area, and its blocking effect on ventilation has become the dominant factor affecting the thermal environment. The results showed the following:

Low vegetation (shrub/lawn) had better performance in the average Ta drop (0.03 °C) and the maximum Tmrt reduction and had less interference with the wind environment.

Although trees could provide shade, in this case, their high canopy coverage (especially the high LAI scenario) significantly hindered the entry of the sea breeze, resulting in an increase in the average Tmrt of up to 2.91 °C and inhibiting the heat dissipation of the site, resulting in a comprehensive warming effect.

Therefore, the optimal strategy was not to pursue the maximum amount of green or coverage but to give priority to maintaining the ventilation efficiency of the area while ensuring the necessary shade. The specific scheme was as follows:

The optimal strategy needed to control the arbor coverage rate at about 35% (the minimum arbor coverage rate required by Qingdao residential area construction standard document) had to balance the shading demand and ventilation requirements.

The “downwind channel” layout was adopted to keep the tree planting direction consistent with the direction of the dominant sea breeze (135°), forming a ventilation corridor, effectively guiding the sea breeze to penetrate the building gap and improving the overall thermal comfort of the site.

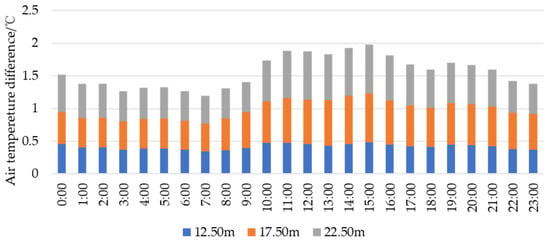

3.3. Cooling Effect Under the Optimal Greening Strategy

The thermal environment differences between the optimization strategy and the current state of the study area were analyzed to evaluate the Ta differences between the proposed and existing conditions. Due to the influence of elevation and the ocean, the average Ta differences at three height planes—12.50 m, 17.50 m, and 22.50 m (which also represent pedestrian-level heights under topographic influence)—were accumulated to analyze the optimized cooling effect. The optimization simulation exhibited a cooling effect throughout the day, with the most significant reduction observed at 15:00. The maximum temperature decreases across the three heights were 0.49 °C, 0.74 °C, and 0.75 °C, respectively (Figure 6). By accumulating the hourly average Ta drop of each altitude layer throughout the day, the daily cumulative Ta drop was calculated to be 12.48 °C. This significant cooling rate indicated considerable carbon emission reduction and energy saving benefits. Among the three investigated heights, the most pronounced cooling effect was observed at 17.50 m, followed by 22.50 m, with the 12.50 m level showing the least reduction. Given that the 17.50 m height level featured the highest building density and the greatest variation in building heights, it could be inferred that the optimization greening strategy has a significant cooling effect in high-density built-up areas on coastal slopes.

Figure 6.

The full-day Ta difference under the current scenario and optimized scenario at three different heights.

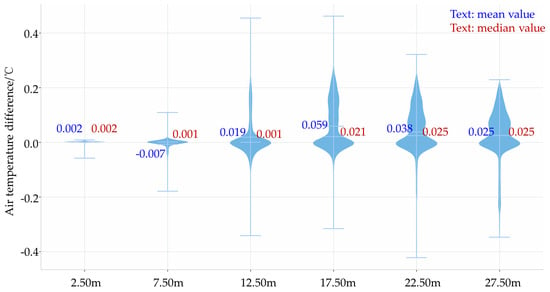

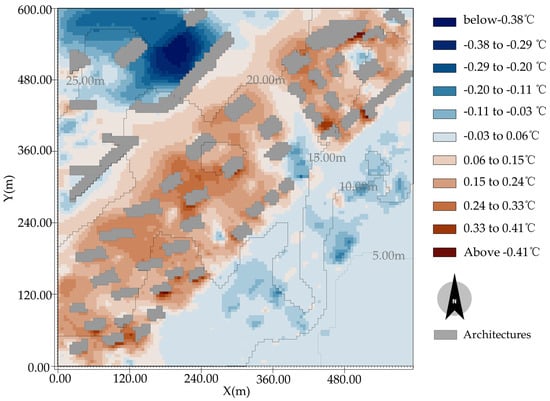

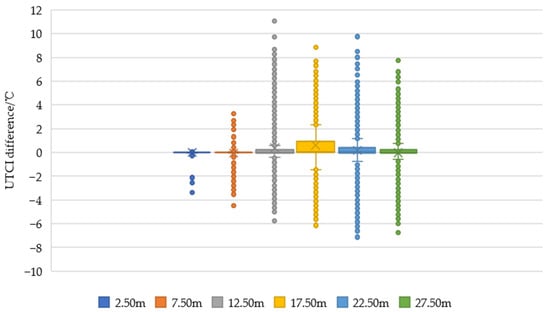

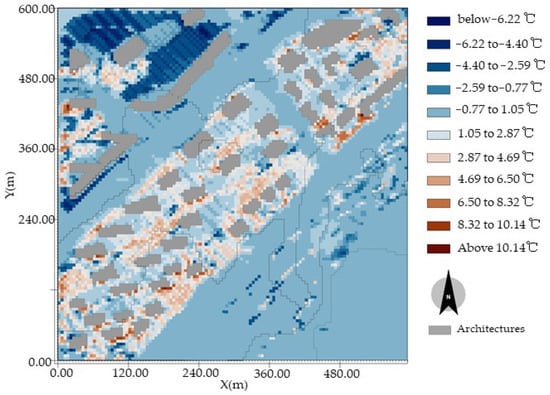

Following the implementation of the optimal greening strategy, an analysis of the thermal environment at six height levels (2.50 m to 27.50 m) at 15:00 in summer was conducted. The results showed that the average Ta and UTCI could be reduced by 0.034 °C and 0.245 °C, respectively, with maximum reductions of 0.462 °C and 11.069 °C (Figure 7). Among all height levels, a slight cooling effect was observed at 2.50 m. In contrast, the 7.50 m layer was the only one that exhibited a warming trend, with an average Ta change of −0.007 °C. The 17.50 m layer exhibited the most pronounced cooling trend, with a mean value of 0.059 °C and a median of 0.021 °C. A significant portion of the area experienced cooling effects, with 43.93% of the region showing statistically significant cooling and 32.19% exhibiting strong cooling, indicating that the majority of the total area demonstrated some level of temperature reduction. Cooling was primarily observed in building-dense areas, particularly to the south of the buildings (Figure 8). The mean temperature reductions at the 22.50 m and 27.50 m heights were 0.038 °C and 0.025 °C, respectively, with cooling proportions of approximately 60–62%. However, the spatial distribution of the cooling intensity differed significantly between these two levels.

Figure 7.

Analysis of Ta difference at 15:00 under current scenario and optimization strategy.

Figure 8.

Ta Difference at 15:00 between current and optimized scenarios (2.50–27.50 m height).

An analysis was performed on the UTCI differences between the current and optimized scenarios across all height levels from 2.50 m to 27.50 m at 15:00, including both statistical and distributional assessments (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The overall performance indicated an average UTCI reduction of 0.183 °C, suggesting a slight cooling trend across the system. The cooling contribution varied significantly with the height, and the strongest effect was observed at 17.50 m, with an average UTCI reduction of 0.608 °C. This was followed by the 12.50 m height, with an average UTCI reduction of 0.379 °C. Distinct from the Ta analysis, the UTCI under the optimization strategy exhibited a slight warming trend at heights of 2.50 m, 7.50 m, and 27.50 m, with average increases of 0.001 °C, 0.064 °C, and 0.015 °C, respectively. At heights where cooling effects were observed, the standard deviation exceeded 1.475 °C, and the cooling area ratio was approximately 63–68%.

Figure 9.

Statistics of UTCI differences at 15:00 between the optimized strategy and the current scenario across all height levels.

Figure 10.

Comparative spatial distribution of UTCI differences at 15:00 between the optimized and current scenarios across all height levels.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Greening Species on the Thermal Environment

Coastal cities typically experience cooling effects due to the influx of cool air under monsoon influence. However, this phenomenon is modulated by the urban surface morphology, generally characterized by a weakening of the sea cooling effect in densely built areas and a prolongation of that effect in vegetated areas [33]. Furthermore, research has shown that in coastal urban–rural areas, where vegetation interacts synergistically with built elements, the cooling dominance of vegetation compared to other structures was not consistent, and in some cases, vegetation’s cooling effect becomes insignificant [34]. Based on the findings from Section 3.2, this study revealed that in high-density built-up coastal sloped areas, the prevalence of extensive building shadows enabled ground-cover vegetation with better ventilation effects to achieve lower Ta. In contrast, trees contributed to warming due to wind blockage and impeded heat dissipation. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that trees with a higher LAI exhibit limited cooling effects, which could be attributed to their enhanced capacity for long-wave radiation trapping and ventilation obstruction. These findings were consistent with prior research by Morakinyo et al. [35], as well as with the thermal performance patterns observed in vegetated coastal slope areas documented in our previous study [23]. This finding appeared to contradict the results of another study conducted in very close proximity to our site. In that study, thermal perception voting indicated that areas with higher vegetation coverage provided better thermal comfort. However, the same study also revealed a positive correlation between the vegetation coverage and Ta in areas with steeper terrain [36]. During summer afternoons, the significant land–sea thermal contrast drove cool sea breezes to ascend slopes, generating a cooling effect under unobstructed conditions. However, the tree canopy caused an abrupt reduction in wind speed, leading to heat accumulation beneath the canopy. Additionally, the canopy intercepted the sea breeze, preventing it from skimming the ground surface and thereby blocking cool air from reaching the understory area. Furthermore, although the canopy itself dissipated some heat through transpiration, the cooling efficiency of this process was lower at midday due to the increased leaf boundary layer resistance and partial stomatal closure, rendering it less effective than the cooling achieved by wind-exposed bare slopes. Combined with the downward long-wave radiation emitted by the canopy, the Ta under the trees in the optimized scenario was higher than that of grassland areas at the same time and altitude, resulting in a maximum Ta increase of 0.17 °C.

4.2. Influence of Greening Layout on the Thermal Environment

Based on locally common greening species and general residential area landscaping standards, an approach that reduces canopy coverage and arranges trees in corridors that facilitate the passage of sea breezes was proposed. The study revealed that this approach can generate extensive cooling coverage in high-density built-up areas facing the sea. Although the UTCI showed a slight increase in areas with sparse tree canopy coverage, it exhibited an overall cooling effect in terms of both the spatial average and cumulative cooling magnitude across the entire study area. Particularly in front of low-rise buildings within coastal areas, the unobstructed passage of cool sea breezes through tree-formed ventilation channels, followed by their entrapment by buildings, created zones of significantly improved thermal comfort. The maximum UTCI reduction recorded at the 17.50 m height reached 10.14 °C, occurring in the wake region of southern buildings. This finding underscored the critical role of sea cooling effects in densely built-up coastal areas. The unobstructed ingress of cool sea breezes into the site could lead to significant Ta and UTCI reduction. Furthermore, maintaining high WS in building wake regions also played a significant role in reducing UTCI during hot summer conditions. Simultaneously, it was observed that in the lee of the continuous buildings at the northwestern corner of the site, the sea breezes were completely blocked. Within this zone, both the Ta and UTCI exhibited warming under the optimized strategy. The maximum Ta and UTCI increases were observed at the 27.50 m height, reaching 0.42 °C and 7.74 °C, respectively. When sea breezes failed to provide cooling for the site, the solar radiation intensity became the primary determinant of the thermal environment. The low tree canopy coverage facilitated stronger long-wave radiation, consequently leading to site warming [37]. This observed warming effect associated with reduced greening coverage was consistent with the findings from other studies [38]. In the western corner of the site, where building openings allowed sea breezes to penetrate unimpeded, both the Ta and UTCI decreased under the optimized strategy—consistent with patterns observed in most densely built areas of the site. However, downwind of the continuous buildings in the northwestern corner, the greening strategy led to warming. Thus, under the combined influence of sea and built environments, the ability of summer sea breezes to penetrate densely built areas becomes a critical factor in shaping the local thermal environment. Where building heights are low and sea breezes readily entered the site, aligning tree planting with the wind direction to form ventilation corridors could improve the thermal conditions and enhance comfort. In contrast, where buildings are taller and form continuous windward facades, greater tree canopy coverage is needed to provide sufficient shading and thereby improve the thermal environment.

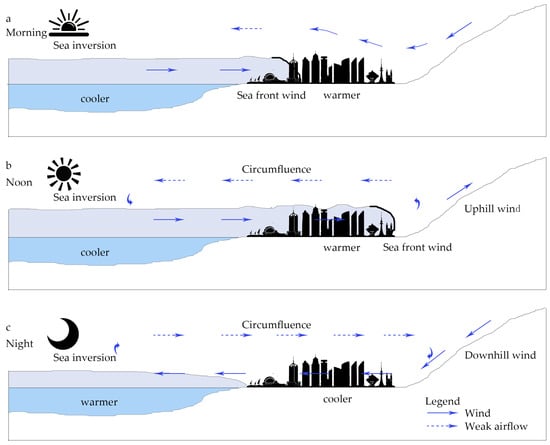

4.3. Thermal Performance Under the Combined Influence of Sea and Slope Terrain

In coastal cities, sea–land breezes, generated by the differing thermal properties of ocean and land surface, exert a considerable influence on urban climate and thermal environment. During the morning hours, when the sea is cooler than the urban area, the onshore breeze introduces cooler air into the city (Figure 11a). During the midday period, the sea breeze front reaches the slope base, generating upslope winds and establishing a return flow from the urban area toward the sea above the urban boundary layer. In this study, the limited penetration of cool sea breezes into the densely built-up areas during midday can also be attributed to this mechanism. Under the combined influence of this circumfluence and the local topography, air pollutants generated within the urban area experience limited dispersion and exert a partial blocking effect on direct solar radiation (Figure 11b). This mechanism also explains the relatively moderate high temperatures observed during summer midday in coastal hilly terrain. During this period, the reduction in canopy coverage and the establishment of ventilation corridors diminished the airflow resistance, facilitating the unobstructed penetration of sea-cooled air through the built-up areas and thereby enhancing sensible heat dissipation. Simultaneously, trees in low-lying areas maintained cooling through evapotranspiration while also avoiding the obstruction of the sky cold source by canopies, thus promoting effective surface heat dissipation via long-wave radiation. Furthermore, persistent airflow continuously transports air that has been cooled and humidified by evapotranspiration, displacing downstream saturated hot air, thereby enhancing the intensity and spatial extent of latent heat cooling. During the night, as the sea becomes warmer than the urban area, a near-surface offshore flow develops, while a circumfluence from the sea toward the land forms within the boundary layer (Figure 11c). This persistent ventilation throughout the day prevents heat accumulation, thereby achieving continuous cooling from daytime to nighttime.

Figure 11.

Diurnal variation of urban sea–land breeze circulation. (a) Urban sea–land breeze circulation in the morning, (b) Urban sea–land breeze circulation at noon, (c) Urban sea–land breeze circulation at night.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

Under the optimization strategy, both the Ta and UTCI exhibited their maximum cooling magnitude and most extensive cooling coverage at the 17.50 m height level, indicating the significant effectiveness of the strategy in this specific region and altitude. As mentioned above, this height was the core layer of the urban canopy heat exchange in this region. This result confirmed the significant effectiveness of the optimization strategy. At the same time, it also revealed the key driving effect of this strategy on improving the thermal environment of urban canopy in a similar environment. In contrast, at the more sea-detached 22.50 m level, a warming effect was observed in the wake of continuous buildings. This finding demonstrated that, in densely built-up coastal slope areas, multiple factors—including the distance from the sea, the layout and parameters of buildings, and the initial thermal conditions of air preheated by passage through built-up areas (including urban roads)—collectively influence the effectiveness of greening-based cooling strategies. Multiple studies on coastal thermal environments have established that background climate and shoreline conditions exert substantial influences on sea–land breeze circulation patterns. For example, investigations in Shanghai revealed that when the sea breeze speeds remained below Force 3 (3.4–5.4 m/s), the LST dynamics were predominantly governed by global warming and urbanization effects. Conversely, parallel research conducted in Guangzhou identified that a minimum threshold of Force 4 was required for the sea breeze to manifest a discernible cooling influence [39]. Based on these findings, more detailed research efforts will require further classification of site types and longer-term extensive investigations. Additionally, constrained by computational resources, the sea area in this model was limited to approximately 8% of the total domain, and simulations under other sea area proportions were not conducted. It remains unknown whether the cooling effect of the sea on downwind densely built-up areas exhibits scale-dependent thresholds in modeling simulations conducted at different spatial scales. In this study, only two kinds of tree coverage and LAI levels were set for analysis. The results showed that the cooling effect was better under the scenario of lower tree coverage and LAI. However, a more detailed parameter gradient was not discussed in this study. Therefore, it is necessary to further explore whether there is an optimal tree coverage and LAI value and whether there is an optimal synergistic ratio between the two.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted a simulation-based investigation of greening cooling strategies in densely built-up areas on coastal sloping terrain. The conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- On coastal slopes, the sea exerts a cooling effect on densely built-up areas when located upwind. This cooling effect intensifies with increasing proximity to the coastline. During hot summer midday conditions, the cooling effect of the sea was diminished by a higher building density, greater windward building height, and the formation of continuous building facades [40].

- (2)

- At 15:00 in summer, the highest Ta in the current scenario was recorded in exposed open spaces within densely built-up areas, with a Ta of 31.6 °C and UTCI of 43.95 °C. This indicated that solar radiation dominated the thermal environment at this time. Nevertheless, when different greening strategies were implemented, the average Ta reduction followed this order: shrubs > lawn > high-coverage and high-LAI trees > high-coverage and low-LAI trees > low-coverage trees. The former two strategies achieved average cooling of 0.15 °C and 0.23 °C, respectively, while the latter three yielded smaller reductions of approximately 0.012–0.015 °C. In summary, for high-density built-up coastal areas, the cooling effect achieved by facilitating the penetration of sea breezes surpasses that obtained through shading by trees.

- (3)

- Based on the findings, the optimal greening strategy for densely built-up areas on coastal slope terrain can be summarized as follows: buildings should be staggered in the direction of prevailing sea breezes to facilitate marine airflow penetration. Under such configurations, reducing the canopy coverage and utilizing tree planting to form ventilation corridors can improve the thermal environment quality. Conversely, where buildings form continuous facades, increasing the canopy coverage is recommended to enhance shading. Therefore, implementing differentiated greening configurations based on building layout patterns is essential for achieving sustainable cooling in high-density coastal areas. This study validated the co-benefits of this strategy in simultaneously improving thermal comfort and reducing energy demand, thereby providing an actionable planning and design framework to enhance urban climate resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z. and S.L.; validation, Y.Z. and X.L.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z. and S.L.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and Y.L.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.Z. and X.L.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Qingdao Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology, grant number 2325039/662. The project is part of the Qingdao Science and Technology Benefiting the People Demonstration Special Project. It is entitled “Research and Demonstration of Low-Carbon Technologies in Qingdao Residential Areas under the Carbon Neutrality Goal”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UHI | Urban heat island |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental panel on climate change |

| PET | Physiological equivalent temperature |

| UTCI | Universal thermal climate index |

| LST | Land surface temperature |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| LAD | Leaf area density |

| Ta | Air temperature |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| WS | Wind speed |

| SR | Solar radiation |

| d | Index of agreement |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| RMSEs | Systematic root mean square error |

| RMSEu | Unsystematic root mean square error |

| CS | Current scenario |

| LTC | Low tree coverage scenario |

| HTC-1 | High tree coverage with low LAI scenario |

| HTC-2 | High tree coverage with high LAI scenario |

References

- Clare, H.; Helen, M.; Sotiris, V. The Urban Heat Island: Implications for Health in a Changing Environment. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronwyn, W. Reflecting on AR6. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13, 890–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.A. An energy and mortality impact assessment of the urban heat island in the US. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 56, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Nitschke, M.; Weinstein, P.; Pisaniello, D.L.; Parton, K.A.; Bi, P. The impact of summer temperatures and heatwaves on mortality and morbidity in Perth, Australia 1994–2008. Environ. Int. 2012, 40, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nitschke, M.; Bi, P. Risk factors for direct heat-related hospitalization during the 2009 Adelaide heatwave: A case crossover study. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 442, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.T. Application of Urban Climate Assessment in Spatial Planning. Master’s Thesis, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China, 2017. Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/ndscholar/browse/detail?paperid=bd6a66aa1a399cc2a8ce799f0612aeeb&site=xueshu_se (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Zhang, H.C. Identification and Design Strategies of Ventilation Corridors in Coastal Mountainous Cities Based on Frontal Area Index. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Martins, H.; Marta-Almeida, M.; Rocha, A.; Borrego, C. Urban resilience to future urban heat waves under a climate change scenario: A case study for Porto urban area (Portugal). Urban Clim. 2017, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Vejre, H. Strong contribution of rapid urbanization and urban agglomeration development to regional thermal environment dynamics and evolution. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 446, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Kolokotsa, D. Three decades of urban heat islands and mitigation technologies research. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solcerova, A.; van de Ven, F.; Wang, M.; Rijsdijk, M.; van de Giesen, N. Do green roofs cool the air? Build. Environ. 2017, 111, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, H.; Mandel, B.H.; Levinson, R. Keeping California cool: Recent cool community developments. Energy Build. 2016, 114, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Pisello, A.L.; Nicolini, A.; Filipponi, M.; Palombo, M. Analysis of retro-reflective surfaces for urban heat island mitigation: A new analytical model. Appl. Energy 2014, 114, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Mayer, H.; Chen, L. Contribution of trees and grasslands to the mitigation of human heat stress in a residential district of Freiburg, Southwest Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.K.; Jim, C.Y. Comparing the cooling effects of a tree and a concrete shelter using PET and UTCI. Build. Environ. 2018, 130, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Khouakhi, A.; Corstanje, R.; Johnston, A.S. Greater local cooling effects of trees across globally distributed urban green spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 911, 168494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hami, A.; Abdi, B.; Zarehaghi, D.; Maulan, S.B. Assessing the thermal comfort effects of green spaces: A systematic review of methods, parameters, and plants’ attributes. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongrui, H.; Xiaohuan, Y.; Hongyan, C.; Xinliang, X. Impacts of Neighboring Buildings on the Cold Island Effect of Central Parks: A Case Study of Beijing, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A.; Rajjak, A.; Singha, S. Understanding the seasonal pattern and factors affecting cooling effect of blue spaces: A case from a Mega Metropolitan Area (India). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Feng, L.; Huang, F.; Sun, J.; Chen, J. Synergistic cooling effects of urban blue-green spaces at microscale: Using the synergistic cooling composite index. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 131, 106768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Qiu, H.; Yang, Y. Thermal environment disparities across 11 cities in the greater bay area: Nonlinear relationships and urban greening-based solutions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 133, 106867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Xijun, H.; Xilun, C.; Zheng, L. Numerical Simulation of the Thermal Environment during Summer in Coastal Open Space and Research on Evaluating the Cooling Effect: A Case Study of May Fourth Square, Qingdao. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Xijun, H.; Zheng, L.; Chunling, Z.; Hong, L. A Greening Strategy of Mitigation of the Thermal Environment for Coastal Sloping Urban Space. Sustainability 2022, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Sun, X.X.; Zhang, G.T.; Tang, H.B.; Liu, Q.; Li, G.M. Long Term Changes of Meteorological and Hydrological Elements in Jiaozhou Bay. Ocean. Lakes 2011, 42, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Guo, F.Y.; Guo, L.N.; Huang, R.; Bi, W.; Zhang, K.J. Variation Characteristics of Wind Environment in Qingdao Based on Observation Data from 1899 to 2015. J. Mar. Meteorol. 2018, 38, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meteorological data room of meteorological information center of China Meteorological Administration. Special Meteorological Data Set for Building Thermal Environment Analysis in China; Meteorological Data Room of Meteorological Information Center of China Meteorological Administration: Beijing, China, 2005.

- Liu, Z.; Cheng, W.; Jim, C.Y.; Morakinyo, T.E.; Shi, Y.; Ng, E. Heat mitigation benefits of urban green and blue infrastructures: A systematic review of modeling techniques, validation and scenario simulation in ENVI-met V4. Build. Environ. 2021, 200, 107939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.G. Judging Air Quality Model Performance. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1981, 62, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J. Some Comments on the Evaluation of Model Performance. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 63, 1309–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunder, M.; Sethuraman, S. A statistical evaluation and comparison of coastal point source Dispersion Models. Atmos. Environ. 1986, 20, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K.C.; Lee, H.; Yang, S.R.; Park, S. A review on the significance and perspective of the numerical simulations of outdoor thermal environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunhao, F.; Liyuan, Z.; Biying, D.; Yao, L.; Shuxian, W. Circuit VRC: A circuit theory-based ventilation corridor model for mitigating the urban heat islands. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Watanabe, H. Spatiotemporal Variation of Outdoor Heat Stress in Typical Coastal Cities Under the Influence of Summer Sea Breezes: An Analysis Based on Thermal Comfort Maps. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, C.; Li, L. Creating a Thermally Comfortable Environment for Public Spaces in Coastal Villages Considering Both Spatial Genetics and Landscape Elements. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakinyo, T.E.; Dahanayake, K.W.D.K.C.; Adegun, O.B.; Balogun, A.A. Modelling the effect of tree-shading on summer indoor and outdoor thermal condition of two similar buildings in a Nigerian university. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Ruirui, Z.; Lei, Y.; Xiaotong, Z.; Yibin, L.; Xi, M.; Weijun, G. Correlation Analysis of Thermal Comfort and Landscape Characteristics: A Case Study of the Coastal Greenway in Qingdao, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, K.M. Is Integrating Tree-Planting Strategies with Building Array Sufficient to Mitigate Heat Risks in a Sub-Tropical Future City? Buildings 2025, 15, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.S.H.; Mahmoud, R.M.A. Sustainable Mitigation Strategies for Enhancing Student Thermal Comfort in the Educational Buildings of Sohag University. Buildings 2025, 15, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, E.; Che, Y.; Wu, Y. Segregation of sea breezes and cooling effects on land-surface temperatures in a coastal city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 118, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, J.; Zhu, P.; Lau, S.S.Y. Effects of urban form on sea cooling capacity under the heatwave. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 88, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).