Managing Coastal Erosion and Exposure in Sandy Beaches of a Tropical Estuarine System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. High-Resolution Morphological Monitoring (GNSS-PPK and DoD)

3.1.1. GNSS-PPK Survey and Data Acquisition

3.1.2. Data Processing and Accuracy Assessment

3.1.3. GIS Processing and Morphological Change Quantification

3.2. Multi-Temporal Coastal and Heritage Assessment

3.3. ICZM Strategies and Sustainability Framework

4. Results

4.1. High-Resolution Coastal Morphodynamics (GNSS-PPK and DoD)

4.1.1. Seasonal Altimetric Patterns (Figure 3)

| Period | Relief Variation (Max/Min) | Morphological Changes |

|---|---|---|

| April 2017 | 3.70 m/−1.28 m | Formation of two distinct sandbanks; indicates calm summer accretion. |

| September 2017 | 3.10 m/−1.00 m | Energetic winter conditions; formation of storm-profile terraces and sandbanks (shift from accretion to erosion). |

| November 2017 | 3.00 m/−0.70 m | Sandbank expansion; new eastern sections formed (indicating a lag in seasonal transition). |

| April 2018 | 2.90 m/−1.40 m | Persistent NE-E depression; central sandbanks nearly merged (continued offshore sediment storage). |

| September 2018 | 3.00 m/−0.80 m | Sandbank separation; formation of a new portion; landward sediment shift (onset of seasonal reversal). |

| December 2018 | 3.20 m/−1.00 m | Sandbank-beach connectivity; central terrace linkage (active dry-season sediment return to beach). |

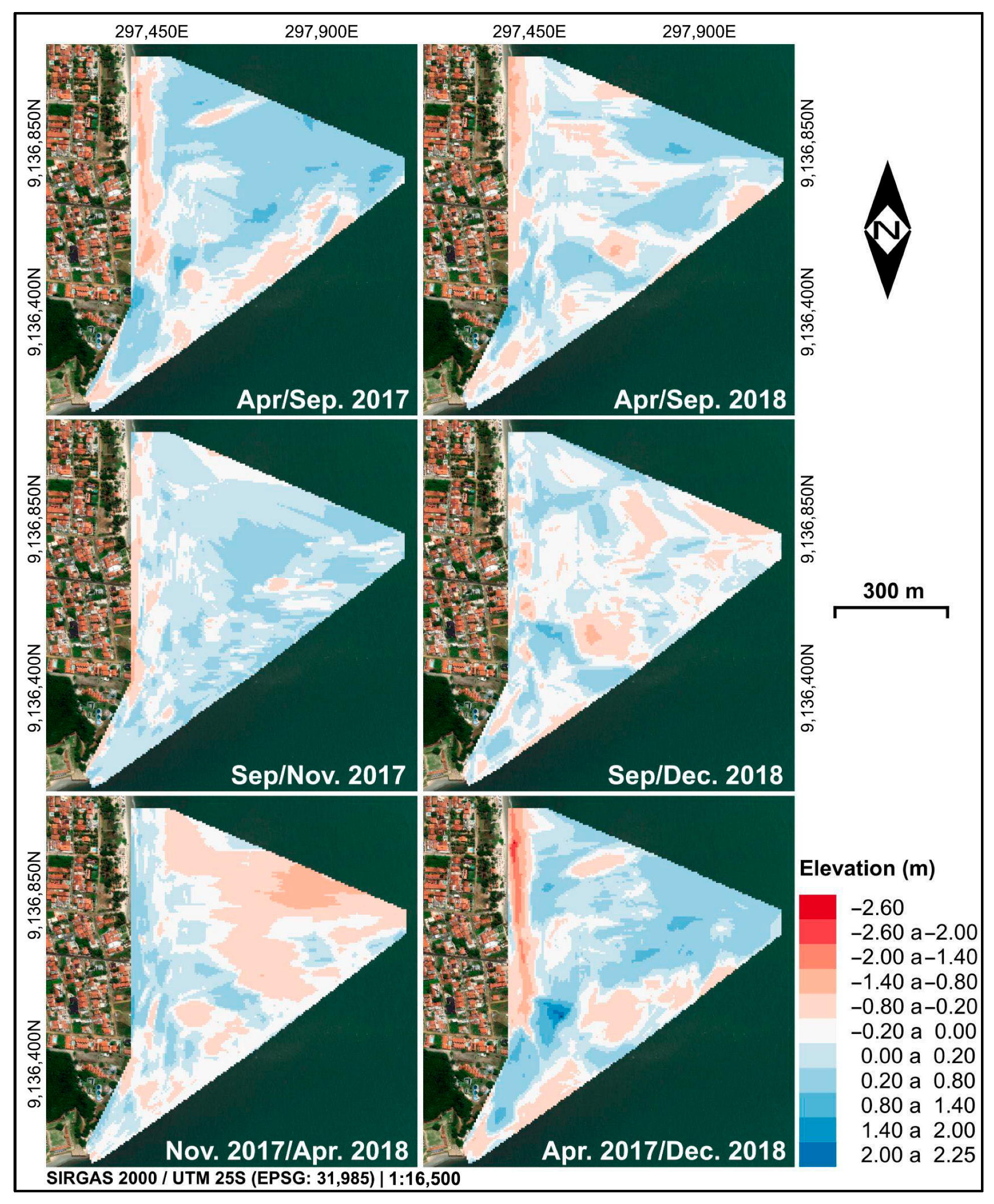

4.1.2. Spatiotemporal Sediment Budget (DoD) (Figure 4)

4.2. Multi-Temporal Exposure and Governance Context

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- List: Comparison of Existing Coastal Erosion Monitoring Methods

- Satellite Remote Sensing (Landsat, Sentinel)

- Spatial/Temporal Resolution: 10–30 m; 5–16-day revisit.

- Strengths: Long historical record; regional shoreline trend detection; identifies large-scale anthropogenic pressures.

- Limitations: Cannot resolve seasonal or short-term changes; lacks vertical accuracy (limited 3D topography for details).

- Uniqueness of This Study: Integrates historical RS with centimeter-level 3D data, allowing multi-scalar morphological assessment.

- Aerial Photography (Manned Aircraft)

- Spatial/Temporal Resolution: <30 cm; infrequent (annual–decadal).

- Strengths: Valuable historical archives; useful for long-term shoreline evolution.

- Limitations: Costly, low repeat frequency; generally provides only 2D information.

- Uniqueness of This Study: Adds 3D elevation models (DTM/Orthophoto) from GNSS + RPAS, enabling volumetric erosion/accretion analysis.

- UAV/RPAS Photogrammetry

- Spatial/Temporal Resolution: 3–5 cm; flexible (weekly/monthly).

- Strengths: High-resolution data; excellent for short-term and seasonal morphodynamics.

- Limitations: Accuracy affected by lighting, flight altitude, forward overlap, and GCP configuration; sandy beaches pose challenges.

- Uniqueness of This Study: Applies optimized flight parameters + dense GCP network + GNSS-PPK, ensuring high-fidelity 3D mapping even on visually homogeneous beaches.

- GNSS Surveys (RTK, PPK, PPP, RK)

- Spatial/Temporal Resolution: Centimeter-level point accuracy; on-demand acquisition.

- Strengths: Best method for precise topographic control; critical for validating other datasets.

- Limitations: Labor-intensive; limited spatial coverage without UAV integration.

- Uniqueness of This Study: Employs GNSS-PPK best practices, enhancing accuracy of UAV-derived DTMs and enabling robust analysis.

- Coastal Video Monitoring Systems (e.g., Argus)

- Spatial/Temporal Resolution: Meter-scale; very high temporal frequency (minutes–hours).

- Strengths: Superior for shoreline/runup tracking and surf-zone dynamics.

- Limitations: Only 2D data; requires fixed infrastructure; lacks vertical information.

- Uniqueness of This Study: Provides full 3D topographic information, allowing true quantification of erosion/accretion volumes.

- LiDAR (Airborne, Terrestrial, Mobile)

- Spatial/Temporal Resolution: 1–10 cm; infrequent due to high cost.

- Strengths: Industry benchmark for coastal topography; highly accurate vertical data.

- Limitations: Expensive; limited availability for municipalities or small-scale management.

- Uniqueness of This Study: Achieves LiDAR-comparable accuracy through affordable GNSS + RPAS workflows, providing a realistic tool for ICZM at the municipal scale.

References

- Lucrezi, S.; Saayman, M.; Van der Merwe, P. An assessment tool for sandy beaches: A case study for integrating beach description, human dimension, and economic factors to identify priority management issues. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 121, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.P.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Schmidt, M.A.R. Avaliação da eficácia do gerenciamento costeiro integrado utilizando AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) para a Ilha de Itamaracá, Pernambuco, Brasil. Geociências 2017, 36, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Chávez, V.; Bouma, T.J.; Van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Arkema, K.K.; Martínez, M.L.; Oumeraci, H.; Heymans, J.J.; Osorio, A.F.; Mendoza, E.; et al. The Incorporation of Biophysical and Social Components in Coastal Management. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, E.; Jimenez, J.A.; Sarda, R.; Villares, M.; Pinto, J.; Fraguell, R.; Elisabet Roca, E.; Marti, C.; Valdemoro, H.; Ballester, R.; et al. Proposal for an Integral Quality Index for Urban and Urbanized Beaches. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botero, C.; Pereira, C.; Tosic, M.; Manjarrez, G. Design of an index for monitoring the environmental quality of tourist beaches from a holistic approach. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 108, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; Groot, R.; Stephen Farberk, S.; Grasso, M.; Bruce Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, L.S. Managed Realignment: A Viable Long-Term Coastal Management Strategy? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-94-017-9028-4. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, A.M. Serviços Ecossistêmicos de Ambientes Costeiros do Litoral de Pernambuco. Ph.D. Thesis, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, 2020; 123p. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, M.C.B.; Costa, M.F. Environmental Quality Indicators for Recreational Beaches Classification. J. Coast. Res. 2008, 24, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.C.; Jiménez, J.A.; Medeiros, C.; Costa, R.M. The influence of the environmental status of Casa Caiada and Rio Doce beaches (NE-Brazil) on beaches users. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2003, 46, 1011–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.R.; Gerhardinger, L.C.; Polette, M.; Turra, A. An Endless Endeavor: The Evolution and Challenges of Multi-Level Coastal Governance in the Global South. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarín, R.S.; Lacouture, M.M.V.; Durón, F.J.R.; Daniela Pedroza Paez, D.P.; Pérez, M.A.O.; Baldwin, E.G.M.; Calzadilla, M.A.D.; Del Carmen Escudero Castillo, M.; Angélica Félix Delgado, A.F.; Salinas, A.C. Caracterización de la zona costera y planeamiento de elementos técnicos para la elaboración de criterios de regulación y manejo sustentable; Instituto de Ingeniería—UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014; 117p, ISBN 978-607-02-6287-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nel, R.; Campbell, E.E.; Harris, L.; Hauser, L.; Schoeman, D.S.; McLachlan, A.; Preez, D.R.; Bezuidenhout, K.; Schlacher, T.A. The status of sandy beach science: Past trends, progress, and possible futures. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2014, 150, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyan, R.D.; Velikova, V.N. Coastal zone e Terra (and aqua) incognita e Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Black Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 169, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolodi, J.; Gruber, N. Abordagem geográfica da Gestão Costeira Integrada. In Geografia Marinha: Oceanos e Costas na Perspectiva de Geógrafos; Muehe, D., Lins-de-Barros, F.M., Pinheiro, L., Eds.; PGGM: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; pp. 382–401. ISBN 978-65-992571-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa, P.V.; Fernandes, E.H. Anthropogenic influence on the sedimentary dynamics of a sand spit bar, Patos Lagoon Estuary, RS, Brazil. J. Integr. Coast. Zone Manag. 2015, 15, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.B.; Jennerjahn, T.C.; Vizzini, S.; Zhang, W. Changes to processes in estuaries and coastal waters due to intense multiple pressures—An introduction and synthesis. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 156, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.C.B.; Souza, S.T.; Chagas, A.O.; Barbosa, S.C.T.; Costa, M.F. Análise da Ocupação Urbana das Praias de Pernambuco, Brasil. J. Integr. Coast. Zone Manag. 2007, 7, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.R.G. A Erosão Costeira e os Desafios da Gestão Costeira no Brasil. Rev. Da Gestão Costeira Integr. 2009, 9, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, K.L.; Barnard, P.L. Anthropogenic influences on shoreline and nearshore evolution in the San Francisco Bay coastal system. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2011, 92, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Canora, F.; Pasquariello, G.; Spilotro, G. Shoreline variations and coastal dynamics: A space-time data analysis of the Jonian litoral, Italy. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 129, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Fitzgerald, D.M. Beaches and Coasts, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; 419p, ISBN 10 0632043083. [Google Scholar]

- Mallmann, D.L.; Pereira, P.S. Coastal erosion at Maria Farinha beach, Pernambuco, Brazil: Possible causes and alternatives for shoreline protection. J. Coast. Res. 2014, 71, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolodi, J.L.; Asmus, M.L.; Polette, M.; Turra, A.; Seifert, C.A., Jr.; Stori, F.T.; Shinoda, D.C.; Mazzer, A.; Souza, V.A.; Gonçalves, R.K. Critical gaps in the implementation of Coastal Ecological and Economic Zoning persist after 30 years of the Brazilian coastal management policy. Mar. Policy 2021, 128, 104470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Imai, K.; Horikawa, H. Tsunami Early Warning Using High-Frequency Ocean Radar System in the Kii Channel, Japan. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2024, 96, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, M.; Scott, T.; Masselink, G.; Russell, P.; McCarroll, R.J. Coastal embayment rotation: Response to extreme events and climate control, using full embayment surveys. Geomorphology 2019, 327, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.J.V.; Pereira, P.S.; Lino, A.P.; Araújo, T.C.M.; Gonçalves, R.M. Morphodynamic Study of Sandy Beaches in a Tropical Tidal Inlet Using RPAS. Mar. Geol. 2021, 438, 106540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.J.V.; Araújo, T.C.M.; Veleda, D.; Pereira, P.S.; Lino, A.P.; Gonçalves, R.M. Shoreline, wave power and global teleconnection influences on a South Atlantic tropical island (Tamarack Island, 1984 to 2020). Catena 2025, 250, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.; Silva, G.V.; Strauss, D.; Murray, T.; Woortmann, L.G.; Taber, J.; Cartwright, N.; Tomlinson, R. Headland bypassing timescales: Processes and driving forces. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, C.; Kjerfve, B. Hydrology of a Tropical Estuarine System: Itamaracá, Brasil. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1993, 36, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, S.G.A. Arqueologia de uma Fortificação: O Forte Orange e a Fortaleza de Santa Cruz em Itamaracá, Pernambuco. Master’s Thesis, Center for Philosophy and Human Sciences, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, 2007; 168p. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.L.N.; Santos, J.L. A Ilha de Itamaracá e a organização da defesa no período colonial (séculos XVI e XVII): Contribuição para a história do litoral norte de Pernambuco, Brasil. Cad. Do LEPAARO 2014, XI, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, K.A.; Pereira, P.S.; Lino, A.P.; Gonçalves, R.M. Determinação da erosão costeira no Estado de Pernambuco através de geoindicadores. Rev. Bras. De Geomorfol. 2016, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil Grupo de Integração do Gerenciamento Costeiro. GI-GERCO/CIRM Guia de Diretrizes de Prevenção e Proteção à Erosão Costeira; GI-GERCO/CIRM: Brasília, Brazil, 2018; 111p, ISBN 978-85-68813-13-3. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, M.; Lucena, V.; Walmsley, D. Fortes de Pernambuco: Imagens do Passado e do Presente; Graftorres: Recife, Brazil, 1999; 204р. [Google Scholar]

- Vousdoukas, M.; Clarke, J.; Ranasinghe, R.; Bescoby, D.; Vafeidis, A.; Mentaschi, L.; Feyen, F.; Sabour, S.; Khalaf, N.; Duong, T.; et al. Climate change threatens coastal heritage worldwide. Res. Sq. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, T.F.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Lino, A.P.; Pereira, P.S.; Sousa, P.H.G.O. Morphodynamic classification, variations and coastal processes of Paiva beache, PE, Brazil. Rev. Bras. De Geomorfol. 2020, 21, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.J.V. Dinámica Costeira e Processos Erosivos: Alternativas de Controle Para o Pontal sul da Ilha de Itamaracá PE, Brasil. Ph.D. Thesis, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, 2022; 147p. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Awange, J.L. Three Most Widely Used GNSS-Based Shoreline Monitoring Methods to Support Integrated Coastal Zone Management Policies. J. Surv. Eng. 2017, 143, 05017003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-de-Villar, F.; García, F.J.; Muñoz-Perez, J.J.; Contreras-de-Villar, A.; Ruiz-Ortiz, V.; Lopez, P.; Garcia-López, S.; Jigena, B. Beach Leveling Using a Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS): Problems and Solutions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, M. Arqueologia do Forte Orange. Rev. Da Cult. 2009, 15, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente—M.M.A. Macrodiagnóstico da Zona Costeira e Marinha do Brasil; MMA: Brasília, Brazil, 2008; 242p, ISBN 978-85-7738-112-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mangor, K.; Drønen, N.K.; Kærgaard, K.H.; Kristensen, S.E. Shoreline Management Guidelines; DHI: Hørsholm, Denamrk, 2017; 462p, ISBN 978-87-90634-04-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Economia—M.E. Manual Projeto Orla; Secretaria de Coordenação e Governança do Patrimônio da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2022; 324p, ISBN 978-65-997520-0-1. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico, Nacional—IPHAN. Projeto de Recuperação e Revitalização, Formulação de um Modelo de Uso e Gestão e Preparação de um Plano de Financiamento Para o Forte Orange: Sub-Projeto de Contenção do Mar e Projeto Executivo; IPHAN: Recife, Brazil, 2009; 84p. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Saleem, A.; Queiroz, H.A.A.; Awange, J.L. A fuzzy model integrating shoreline changes, NDVI and settlement influences for coastal zone human impact classification. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 113, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Tecnologia de Pernambuco—ITEP. Relatório de Impacto Ambiental—RIMA: Recuperação da Orla Maritima Municípios de Jaboatão dos Guararapes, Recife, Olinda e Paulista (Pernambuco); ITEP: Recife, Brazil, 2012; 98p. [Google Scholar]

- Luijendijk, A.P.; Schipper, M.A.; Ranasinghe, R. Morphodynamic Acceleration Techniques for Multi-Timescale Predictions of Complex Sandy Interventions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredini, P.; Arasaki, E. Obras e Gestão de Portos e Costas: A Técnica Aliada ao Enfoque Logístico e Ambiental, 2nd ed.; Blucher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009; 804p. [Google Scholar]

- Worldbankgroup. Global Economic Prospects, January 2022; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vousdoukas, M.L.; Clarke, J.; Ranasinghe, R.; Reimann, L.; Khalaf, N.; Duong, T.M.; Ouweneel, B.; Sabour, S.; Iles, C.E.; Trisos, C.H.; et al. African heritage sites threatened as sea-level rise accelerates. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perricone, V.; Mutalipassi, M.; Mele, A.; Buono, M.; Vicinanza, D.; Contestabile, P. Nature-Based and Bioinspired Solutions for Coastal Protection: An Overview among Key Ecosystems and a Promising Pathway for New Functional and Sustainable Designs. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 80, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Rui, S. Field implementation to resist coastal erosion of sandy slope by eco-friendly methods. Coast. Eng. 2024, 189, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, M. Arqueologia do forte Orange: O forte holandês. Rev. Da Cult. 2010, 17, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, M. Arqueologia do Forte Orange II. Rev. Da Cult. 2010, 16, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Type of Change | Locations | Elevation Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter Erosion | |||

| April–September 2017 | Losses | Central-northern shoreline; near SE bulwark of Forte Orange. | −1.70 m |

| Gains | Low-tide terraces and sandbanks. | +1.30 m | |

| April–September 2018 | Losses | Near the beach face | −1.40 m |

| Gains | Along the sandbanks | +1.20 m | |

| Summer Accretion | |||

| September–November 2017 | Losses | Narrow strip parallel to beach | −1.07 m |

| Gains | Foreshore and shoreface | +0.70 m | |

| November 2017–April 2018 | Losses | Shoreface (notably NE boundary) | −1.20 m |

| Gains | Foreshore and backshore | +1.00 m | |

| September–December 2018 | Net Change | Across the study area (uniform) | ±1.15 m |

| Net Change (Full Period) | |||

| April 2017–December 2018 | Losses | Shoreline (Forte Orange to ICMBio/CMA); S-N strip to northern limit | −2.60 m (max) |

| Gains | ICMBio/CMA beach; sandbank-beach connection; offshore shoreface (NE boundary) | +2.25 m (max) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Araújo, R.J.V.; Araújo, T.C.M.; Pereira, P.S.; Queiroz, H.A.d.A.; Gonçalves, R.M. Managing Coastal Erosion and Exposure in Sandy Beaches of a Tropical Estuarine System. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411046

Araújo RJV, Araújo TCM, Pereira PS, Queiroz HAdA, Gonçalves RM. Managing Coastal Erosion and Exposure in Sandy Beaches of a Tropical Estuarine System. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411046

Chicago/Turabian StyleAraújo, Rodolfo J. V., Tereza C. M. Araújo, Pedro S. Pereira, Heithor Alexandre de Araujo Queiroz, and Rodrigo Mikosz Gonçalves. 2025. "Managing Coastal Erosion and Exposure in Sandy Beaches of a Tropical Estuarine System" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411046

APA StyleAraújo, R. J. V., Araújo, T. C. M., Pereira, P. S., Queiroz, H. A. d. A., & Gonçalves, R. M. (2025). Managing Coastal Erosion and Exposure in Sandy Beaches of a Tropical Estuarine System. Sustainability, 17(24), 11046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411046