Abstract

Ecosystem services provided by coastal and marine environments are increasingly recognised as of paramount importance for human wellbeing. To inform marine spatial planning and its implementation, as well as to manage conflicts between marine resource beneficiaries, we developed a comprehensive estimate of the economic value of the ecosystem services of Algoa Bay (AB) from 2000 to 2019. This is to assist in the development of effective policies concerning the management of marine resources. We quantified and assessed the monetary value by integrating 15 ecosystem services (ES) across five ecosystems using a range of economic valuation techniques and four scenarios. The scenarios differentiate between the local and global beneficiaries of the services and a conservative and alternative valuation estimate. These latter two valuation benefits are calculated using different sets of valuation estimates. We identified that onshore ecosystems, and recreation and tourism services, hold the most value. We estimated that the value grew from USD 613.4 million to USD 1695.9 million for local beneficiaries and from USD 1127.7 million to USD 2787.9 million for global beneficiaries between 2000 and 2019. The local values are roughly equivalent to the municipal budget, implying that the value of the ES is at least equal to that of the combined value of public service delivery. This highlights the significant economic contributions of marine and coastal ecosystems to local economies. This valuation provides a framework to make explicit the value that beneficiaries derive from marine ecosystems and provides a novel perspective on the valuation of ES in the coastal and marine ecosystems. This framework can be replicated elsewhere where there is a need to develop the ocean economy in an equitable and sustainable way.

1. Introduction

Over a third of the global population resides in coastal areas [1]. Communities in these regions and their associated economic activities rely on marine ecosystem services (ES) for their livelihoods and wellbeing [2,3,4]. Anthropogenic pressures, however, are jeopardising many coastal and marine ecosystems and their benefits [1,5,6,7], both now and in the future [8]. It is estimated that approximately 60% of major marine ecosystems have either been exploited unsustainably or degraded [9]. These ever-increasing pressures include fishing, climate change, ocean acidification, pollution and habitat degradation [10]. Altogether, the haphazard development of marine uses, the emergence of new uses and a growing coastal population are expected to intensify the decline of marine ecosystem health [11,12].

Given the growing scarcity of resources, increasing trade-offs and the intricate interplay between natural ecosystems and human activities, coupled with the significant environmental challenges confronting resource management, there is an increasing demand for comprehensive, systematic assessment frameworks [1,13,14]. One such important framework is marine spatial planning (MSP). MSP addresses these environmental challenges and impacts in a strategic and cohesive manner and comprises the process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives to promote sustainable ocean management and governance in coastal and marine ecosystems [15,16]. MSP hence recognises the need for ocean-based development and supports decision-making by facilitating the expansion of marine activities, while aiming to improve social and economic conditions and protect ecosystem integrity [17,18].

To inform an MSP and its implementation, as well as to manage conflicts between marine resource beneficiaries and develop effective policies concerning the management of marine resources, an independent economic basis is required [19]. ES valuation is an approach that incorporates and recognises natural capital in economic development and supports policymaking [3,20]. ES valuation is a tool in MSP as it can assist in developing an understanding of temporal changes and economic trade-offs between different marine ES, plans, policies and scenarios [10]. Moreover, it provides a framework to explicitly measure how policy and decision-making may impact marine ecosystems and their associated costs and benefits to society [4,21,22,23].

This study seeks to address the dual question of (i) how to apply ES in a comprehensive and replicable manner within a data scarce context so that it can inform MSP by means of a consistent framework, and (ii) what are the ES values for AB and how did they change over time? Question 1 is addressed in Section 3, while question 2 is answered in Section 4. The results are discussed in Section 5. First, however, a review is performed of marine spatial planning and the context thereof in general.

2. Marine Spatial Planning: A Review

MSP is being incorporated into ocean-based development, as many countries seek to adopt ocean-based economic directives [24,25]. In 2014, South Africa launched “Operation Phakisa” with the primary goal of utilising the economic potential of South Africa’s marine ecosystems [26]. This initiative aims to be applied through an integrated ocean governance framework, with MSP forming an integral part of the implementation process [27]. As part of the detailed MSP planning process, South Africa’s ocean space has been divided into four bio-geographic marine areas that serve as planning domains for which marine area plans will be designed and implemented [28]. Moreover, Algoa Bay (AB) in South Africa has been identified as a key node of implementation of MSP within South Africa as it is regarded as one of the best-monitored marine ecosystems on the continent and serves as one of the designated focus areas of the MSP development process [27].

The Algoa Bay Project, a research consortium formed in 2019, has since produced products and frameworks to inform MSP in South Africa [29]. To address the final challenge outlined in the project strategy—namely, the development of scenarios for management strategies to be used in stakeholder engagement—the impact on ES and their use in the project was recognised as an important avenue of inquiry [30]. Although more ecosystem service studies have been conducted in South Africa than any other African country, almost all ecosystem service valuations in South Africa have been conducted exclusively on terrestrial ecosystems [31,32,33,34,35], with only a couple of studies conducted on a local scale [36,37] and only a single study comparing long-term temporal changes in ES [38]. Furthermore, studies conducted on a local scale are scarce and currently insufficient to inform policy and resource management for local government [35]. Marine ecosystem service valuations in Africa are rare, but do include a few for coastal services [39], large marine ecosystems [40] and kelp forests [41] at continental to country scales, and a few local-scale studies for South [42], East [43] and West Africa [44,45,46].

Given these gaps in knowledge and the current implementation of the MSP process, there is an urgent need to conduct ecosystem service valuations of marine and coastal ES in South Africa. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop South Africa’s first comprehensive framework and valuation of marine ES in AB to inform the MSP process and contribute to policymaking on a local scale and, later, at a scaled-up national scale.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

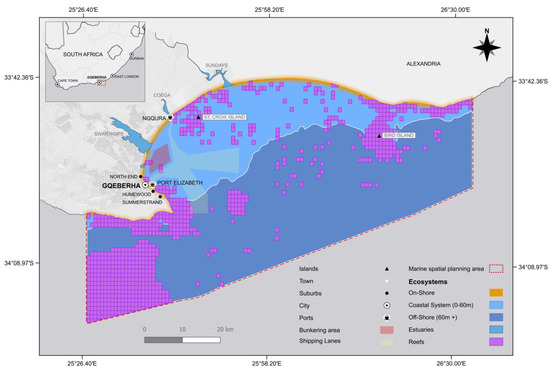

Algoa Bay is situated between Cape Recife (34°02′ S, 25°42′ E) and Cape Padrone (33°46′ S, 26°28′ E), on the south-east coast of South Africa, and is one of the largest bays in the country [27]. The study area for our ES valuation framework and subsequent valuation was based on the boundaries delineated for the AB Project [27]. It extends from the high-water mark to 12 nautical miles offshore, and from the western boundary of the Sardinia Bay Marine Protected Area (MPA) to the eastern perimeter of Cannon Rocks, encompassing five estuaries and totalling 448 516 hectares. The study area consists of five broad coastal and marine ecosystems: onshore, coastal, offshore, coral reefs and estuaries (Figure 1) [29,47].

Figure 1.

Algoa Bay Project study area showing the five ecosystems included in the valuation. Adapted from the Algoa Bay Project [29].

The Bay is considered a biodiversity hotspot, supporting the largest breeding colonies of critically endangered African Penguin Spheniscus demersus and endangered Cape Gannet Morus capensis [48,49,50]. On the western edge of the Bay lies the industrial city of Gqeberha (formerly Port Elizabeth) within the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropole [51]. The local economy is centred around two shipping ports, Ngqura and Port Elizabeth, that are used by the motor industry as well as the agricultural and mining sectors [27,50,52]. Tourism additionally attracts millions of visitors each year and has been recognised as an important economic contributor [53].

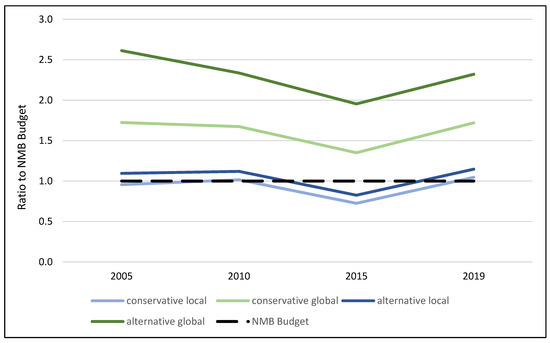

Other socio-economic marine activities include commercial fisheries and aquaculture [29]. Gqeberha is South Africa’s third largest coastal city with a population of approximately 1.3 million people. Sixteen percent of the population live in poverty and 37% of the population are unemployed [54]. The average purchase power parity adjusted annual income per person in the metropole is USD 8251 [54]. All nominal ZAR values herein have been converted to USD using the purchase power parity (PPP) exchange rate. The exchange rates used are ZAR2.759:USD (2000), ZAR3.556:USD (2005), ZAR4.62:USD (2010), ZAR5.825:USD (2015), ZAR6.707:USD (2019) [55]. Moreover, the municipal budget has grown from approximately USD 875 million in 2005 to more than USD 1.5 billion in 2019 (purchase power parity adjusted; Table 1). Data for 2000 is unavailable due the fact that the municipality changed reporting systems after 2000, and the prior data is no longer available.

Table 1.

Nelson Mandela Bay Municipal revenue and expenditure collated from NMBM annual reports and budgets between 2005 and 2019 (purchase power parity adjusted USD, thousands) [56,57,58,59].

3.2. Ecosystem Services Valuation Framework

The five ecosystems in AB (Figure 1) are diverse and render a range of ES. To capture this range of values, a framework comprising 15 ES, which are grouped into four categories as defined by the MEA [1], have been developed. This framework is based on Blignaut and Lumby [60], De Groot et al. [61], Clifton et al. [14], Blignaut et al. [62] and Blignaut et al. [63].

The valuation of these 15 services, as summarised in Table 2, will subsequently be discussed individually in terms of their definitions and aspects related to their monetary and biophysical boundaries and measures. It should be noted that while all effort has been made to estimate the most appropriate unit values, the unit values are constant per service and ecosystem. Given the scope of five ecosystems and 15 services, no intra-ecosystem variation in unit values were possible. Furthermore, all local benefits, per definition, also accrue to the global population, but not all services render a local value. In those cases, it implies an elevated global value. The sources of data and details concerning the valuation methods are provided in Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2.

Table 2.

Demarcation of the ecosystem services by ecosystem and valuation method applied.

Four scenarios are being presented. They are for local and global beneficiaries, and for each of these two beneficiary groups a conservative and an alternative scenario were estimated. In each ES valuation, the smaller local population forms part of the global beneficiary group; however, some ecosystem services are only derived by the global level and not at the local level. While each of the beneficiary groups proved instrumental within the study, the local NMB residents are of particular importance on account of both the MSP orientation as well as the fact that benefits realised within such a group has direct implications for benefits realised among both the national and international groups. The conservative and the alternative scenarios for these two beneficiary groups refer to different sets of published unit ES values that were available from different sources. These scenarios are therefore not upper and lower scenarios from a single set of unit values, but rather different unit values from different sources, with the conservative scenario using the lowest available value each time.

The ES valuation was conducted in nominal ZAR terms. Where necessary unit values were converted to ZAR using the appropriate PPP rate. All values are reported in nominal USD terms. ZAR values have been converted to USD using the PPP rates highlighted above. Real values were converted to nominal terms using the consumer price index. Having developed a full dataset in ZAR terms, it has been converted to USD using the PPP exchange rates mentioned above.

We turn to the specific method used in performing the various ES valuation estimates.

3.2.1. Right of Access

Definition and Scope

As per He et al. [64], the spatial extent of an ecosystem provides a carrier service allowing a range of economic activities and infrastructure, such as a port wharf and related activities, to exist. The access to natural infrastructure allows the local authorities to extract rent from the users of the carrier service—rent that would not have been possible without the ecological infrastructure and its subsequent carrier service. Statutory prices have been used as an expression of the revealed preference to use the carrier service.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

With respect to mariculture, the statutory permit fee allowing the right to engage in aquaculture linked to the area assigned was used.

With respect to fishing, the statutory permit and licence fees as attributed to the class of fishery (i.e., small pelagic, traditional line fishing, squid, shark longline and inshore demersal trawl) were multiplied by the number of vessels permitted to access the resource—see Appendix C.

With respect to industrial sites and ports, the value was determined by multiplying the statutory fee, or rate, for industrial properties with the relevant area they are occupying per ecosystem in hectare.

3.2.2. Food Provisioning (Non-Cultivated)

Definition and Scope

The value of the fish catch, inclusive of all classes as well as that harvested from the estuary, was estimated. Market prices have been used as an expression of the revealed preference.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

The total fish catch per class of fishery in ton was multiplied by the average annual unit price based on market prices.

3.2.3. Food and Raw Materials (Cultivated)

Definition and Scope

The value of the mariculture production based on yield per hectare and the yield for the respective years was estimated.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

The annual yield in ton in mariculture was multiplied by the average annual unit price based on market prices.

3.2.4. Waste Dilution

Definition and Scope

Using the replacement cost method, the capital and operating cost of manufactured infrastructure to remove dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP), the value of the waste dilution service of the estuary was estimated.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

The difference in the DIP and DIN concentration levels between the head and the mouth of the estuaries were calculated. This provides an indication as to the level to which the estuary removed the inorganic material from the body of water. This was multiplied with the cost of manufactured capital to do the same using values from the local wastewater treatment facilities (Appendix A).

3.2.5. Air Quality Regulation

Definition and Scope

Using the benefit transfer method, De Groot and Bönhke-Heinrichs [65] calculated the amount of NOx, in the form of fine dust, captured by the onshore ecosystem and estimated an amount per kilogram based on the cost that would have arisen from health damage. The values for different biomes within the ecosystem were calculated to estimate a value per hectare.

Jones et al. [66] used a comparison of two scenarios for the coastal system, namely, a ‘no vegetation’ and ‘current vegetation’ scenarios. The amount of sulphur dioxide, fine particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and ozone removed under both scenarios was calculated by assessing the change in concentration, and a monetary benefit was then estimated based on health benefits. The difference equals the value per hectare.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

The unit values as derived from the international studies were applied on an area basis within this study. Using the benefit transfer mechanism has its disadvantages, namely, among others, a fixed unit rate per ha and the ignorance of the context, but in the absence of any local study, it is considered better than not including a value at all. This applies to all cases using the benefit transfer method.

3.2.6. Climate Regulation

Definition and Scope

This service ensures that the local climate does not significantly vary to opposing extremes. Herein, this service relates to the carbon sequestration ability of the ecosystems.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

Using the benefit transfer method, the unit values as derived by Christie and Rayment [67], Ganguly et al. [68] and Adams et al. [69] for the onshore, coastal and estuarine areas were applied to the relevant areas (see Figure 1).

3.2.7. Moderation of Extreme Events

Definition and Scope

This service refers to the non-use value derived from ecosystems acting as protection against natural disasters and climate-related events. Using the benefit transfer mechanism unit values were derived from published sources.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

As with climate regulation, the benefit transfer method was used based on Christie et al. [70] and Samonte et al. [71]. Unit values per ha for the coastal and coral reef systems were derived and applied to the relevant areas.

3.2.8. Erosion Prevention

Definition and Scope

This service refers to the protection of soil and the maintenance of water quality in nearby water bodies and is relevant to the coastal systems and coral reefs.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

Using the benefit transfer method, the unit values as estimated by Han et al. [72] and Albert et al. [73] for the coastal and coral reef systems were applied to the relevant areas.

3.2.9. Nutrient Cycling

Definition and Scope

With estuaries supporting the life cycles of such a broad array of organisms and marine animals, the ecosystem service of nutrient cycling proves extremely valuable. The monetary value of this service is estimated by calculating the nursery value of an area. An estuary’s nursery value is the ability of the estuary to be in a condition suitable enough to be nursery grounds for marine organisms, specifically the juveniles.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

A local study by Turpie and Clark [74] estimated nursery values by observing freshwater flows, frequency and duration of estuary mouth openings. These are the biggest factors affecting estuarine biota. The authors estimated the value of the biota using local and prevailing market prices.

3.2.10. Water Quality

Definition and Scope

Water quality value was estimated as the sum of a cultural use and an infrastructure replacement component. To estimate the cultural use, component benefit transfer was used with reference to Magobiane [75], where the study’s aim was to determine how much the users of the estuary value changes (improvements) in water quality to safer levels for other services such as swimming, fishing and maintenance of biodiversity and general human wellbeing. To estimate the infrastructure replacement cost component of the water quality ecosystem service in estuaries, reference was made to the function of estuaries in removing pollutants from water through nitrogen and phosphorous cycles [76]. This function was compared to that of wastewater treatment plants that remove pollutants through industrialised processes.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

While focussing on estuaries, the unit values as reported in Magobiane [75] and Huang et al. [76] were used and multiplied with the relevant areas.

3.2.11. Maintenance and Protection of Nursery and Gene Pool and Life Cycle

Definition and Scope

This refers to the service provided by ecosystems that supports and maintains biodiversity levels by providing suitable conditions and functioning habitats. Although all five of the ecosystems found in AB provide this service, suitable studies for the benefit transfer could only be found for the coastal systems and offshore ecosystems.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

Watson et al. [77] and Beaumont et al. [78] estimated unit values for coastal and offshore systems. These values were multiplied with the relevant areas.

3.2.12. Amenity Value

Definition and Scope

Residential properties have amenity premiums above similar properties based on their proximity or access to a given resource, such as enjoying coastal views and access to beaches.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

Using property values in accordance with the hedonic pricing method, we estimated the average price premium of properties with an ocean view and those without for three suburbs with close access to the ocean. The price premium per m2 was calculated using actual sales data by comparing house prices with the same physical features with or without an ocean view. This premium in m2 terms was multiplied by the extent of the area with an ocean view and multiplied by the municipal rate to determine the elevated price people are willing to pay for the amenity service.

3.2.13. Recreation and Tourism

Definition and Scope

Three methods were employed for this valuation: travel cost, total spend and opportunity cost methods. The ecosystems involved in the valuation include onshore, coastal systems, coral reefs and estuaries.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

The travel cost method uses market prices and is based on the travel expenses incurred in visiting a destination as a proxy for the value of access to the destination. The travel cost was calculated by measuring the total distance travelled and multiplying it with the cost per distance (R/km). The travel cost method has been applied only to the domestic tourists visiting the region, as it is assumed that foreign tourist trips prove insignificant relative to those taken by domestic tourists.

The second method employed in calculating the recreational ecosystem service value was that of direct recreational spend. This method allowed for the calculation of the total amount of money spent by foreign and domestic tourists alike. Domestic tourist spend comprised both day visitors as well as overnight visitors. Day visitors refer to tourists visiting NMB from close proximity and do not require overnight accommodation. The day visitor spend was calculated by multiplying the average spent per visitor per day with the total number of domestic day visitors visiting the Bay. The total overnight spent value was calculated by multiplying the total number of overnight visitors multiplied with the average spend per overnight visitor. To assess foreign tourists, a similar calculation was performed to that of domestic overnight spend, as foreign visitors only visit the Bay for periods longer than a day. The total number of foreign bed nights/visitor days was multiplied with the average spent per foreign visitor per day.

The opportunity cost method calculates the value of income forgone while on holiday. This value is indicative of what the service is worth to the individual. As with the travel cost method, the opportunity cost method was applied only to the domestic tourists visiting the region. The total amount of time spent at the Bay was multiplied with a standardised value of time, i.e., the GDP/capita.

3.2.14. Spiritual, Cognitive and Other

Definition and Scope

The ecosystem service of inspiration for culture, art and design, spiritual experience and information for cognitive development encompasses a range of smaller ES. Inspiration for culture, art and design refers to the enjoyment of individuals when appreciating the aesthetic qualities of nature and the inspiration that results from these aesthetic qualities. Spiritual experience generally refers to the sense of place and sense of experience that ecosystems instil in individuals, as nature can generate feelings of attachment and identity, and individuals place symbolic meaning in ecosystems. Finally, ecosystems can provide the right conditions for learning and the gathering of information. Although all five ecosystems found in AB provide this service, suitable studies could only be found for the onshore, coastal and coral reefs ecosystems.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

Using the benefit transfer method, the unit values for onshore ecosystems based on Christie and Rayment [67] was used, values for coastal areas were provided by De Groot and Bönhke-Heinrichs [65] and Failler et al. [79] provided unit values for estuarine areas. The unit values remained constant across the relevant ecosystems, irrespective of location, and that is a subject for further research.

3.2.15. Existence and Bequest

Definition and Scope

Individuals derive utility solely from the knowledge that biodiversity exists and place a high value on this existence. Furthermore, bequest values arise from the knowledge that this biodiversity will persist for the enjoyment of future generations. Once again, this service is provided by all the ecosystems which make up AB. However, suitable studies were only found for the coastal systems and coral reefs ecosystems.

Biophysical and Monetary Boundaries and Measures

Similarly, the benefit transfer method was used by applying unit values by Perni et al. [80] for coastal systems and by Turpie [81] for offshore systems. Values for coral reefs were derived from Seenprachawong [82], O’Garra [83], Failler et al. [79], Aanesen et al. [84] and Maynard et al. [85]. These unit values were multiplied with the respective areas.

4. Results

4.1. Value of Ecosystem Services for Various Beneficiaries

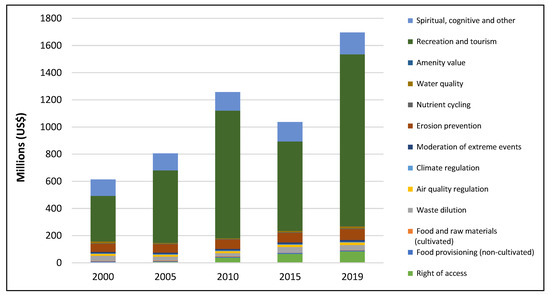

Our results indicates that the value of ES in AB increased with time, except for the values between 2010 and 2015. This trend is consistent for the value derived by both local and global beneficiaries under the conservative and alternative scenarios. Under the conservative scenario, the value derived from marine ecosystems services in AB grew, in purchase power parity adjusted terms, from USD 613.4 million in 2000 to USD 1632.1 million in 2019 for the local beneficiaries, while the value grew from USD 1127.3 million in 2000 to USD 2683.1 million in 2019 for the global beneficiaries (Table 3).

Table 3.

Economic value of Algoa Bay’s ecosystem services for local and global beneficiaries (USD, millions).

4.2. Value of Ecosystem Services for Local Beneficiaries

Differences in values placed on marine and coastal ecosystems in AB by the residents of Nelson Mandela Bay Metropole (local) and the global beneficiaries can be attributed to the supporting (maintenance of genetic diversity and life cycle) and cultural (recreation and tourism; existence and bequest; spiritual cognitive and other) ES. These values are significantly higher at the global than the local level, since existence and bequest services were only included for the global beneficiaries. Moreover, given the international nature of recreation and tourism, additional valuations were included for the global beneficiaries.

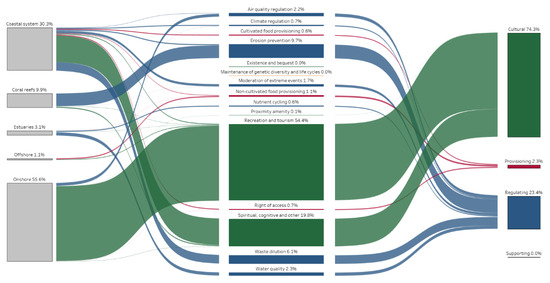

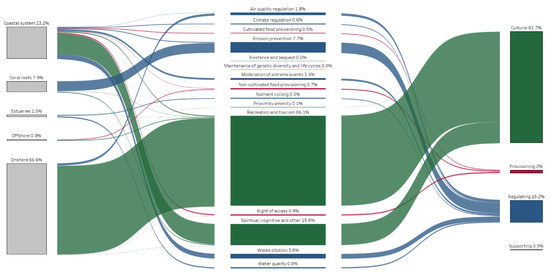

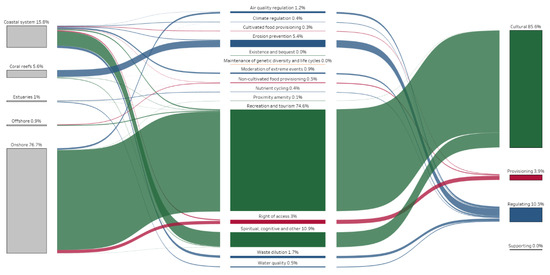

Cultural services were the most valuable of the four major types of ES, accounting for approximately three quarters of the value over the past two decades. Recreation and tourism contributed the highest value among the 15 ES, followed by another cultural ecosystem service in the form of spiritual, cognitive and other (Figure 2). Recreation and tourism explain between 54% and 75% of the value for local beneficiaries and between 50% and 71% for global beneficiaries of the value over the past two decades (see Appendix B and especially Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4, Figure A5, Figure A6, Figure A7, Figure A8, Figure A9 and Figure A10).

Figure 2.

The value of ecosystem services derived by the local beneficiaries.

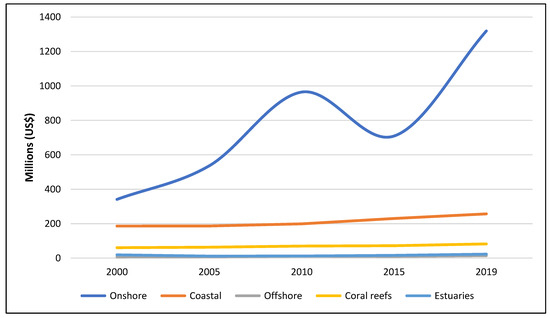

4.3. Value of Ecosystem Services in Terms of Ecosystems

The onshore ecosystem was the most valuable ecosystem, with the value exceeding the sum of all the other ecosystems combined. This ecosystem also had the greatest increase in value with a three-fold increase in value over the past two decades (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conservative estimate of the economic value of the ecosystem services rendered by Algoa Bay for the local beneficiaries.

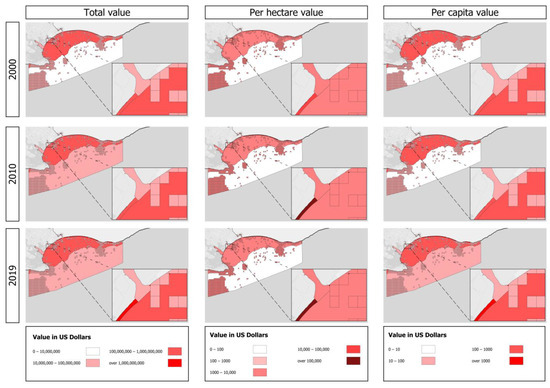

Figure 4 provides a summary of the ecosystem valuation results expressed spatially. The onshore ecosystem had the highest value of all the coastal and marine ecosystems in this study. This is unsurprising, given that many valuations have documented the substantial value that onshore ecosystems provide through amenity and recreational services [62,86]. For example, of the 196 coastal and marine ecosystem studies reviewed, Torres and Hanley [86] found that most of the studies concentrated on beaches. Recreation and tourism ES generate billions in US dollars on an annual basis in Africa [35]. Previous studies in South Africa have also found recreation and tourism to contribute a substantial, if not the largest, portion to overall values [36,87,88]. In this study, recreation and tourism accounted for at least half of the total value for all estimates and beneficiaries over the past two decades, peaking at three quarters of the total value for local beneficiaries in 2010. The rise in the proportionate value of recreation and tourism can be attributed to the 2010 FIFA World Cup, since Gqeberha hosted several of the matches. Mega-events such as this one have been documented to increase the economy of host nations [89]. The 2010 FIFA World Cup attracted 306,600 tourists to the country who spent USD 444 million [90]. This translated to an increase of 24 percent in average visitor spend compared to previous years and would explain the increase in the value of tourism during this time.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of valuation results of Algoa Bay’s ecosystem services: 2000–2019. Ecosystem delineations are provided in Figure 1.

5. Discussion

This study developed the first comprehensive economic valuation of marine ES in Africa and provides an economic basis to support the implementation of MSP in South Africa. Our study suggests that the overall value of ES in AB has increased over the past two decades and highlights the importance of marine and coastal ecosystems and their associated ES to the local economy. As part of the MSP process, we are able to identify the ecosystems and ES that hold the most value, namely, onshore and recreation and tourism, respectively (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Moreover, our study demonstrates the merit of performing the valuation at multiple time-steps in detecting structural changes in ES.

Our study also revealed that the value of ES has increased over time, with the value of ES growing by over USD 1 billion over the period of two decades. The ES were valued to be equivalent to the municipal revenue of Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality over the past two decades for local beneficiaries (Figure 5), emphasising the substantial value inherent to these marine ecosystems. Similarly, a review by Banela et al. [91] emphasised the importance of integrating ecosystem services, and, in particular, cultural ecosystem services in MSP, to sustain inclusive coastal/marine planning. Moreover, this study valued ES of AB at almost double that of Cape Town over a similar period [36]. Both studies are comparable in scale and geography (coastal cities in South Africa), yet the values are substantially different. These disparities could be attributed to the differences in the selection and classification of ecosystems since De Wit et al. [36] focused predominantly on terrestrial ES (with beaches being the only coastal ecosystem included). This indicates that coastal and marine ecosystems, particularly the onshore ecosystem, holds a substantial value even under varying valuation frameworks. These findings emphasise the growing recognition of the importance of ES and the need to take precaution in the development and expansion of ocean-based activities through initiatives like Operation Phakisa. Moreover, this underscores the necessity for increased conservation and sustainable management efforts to maintain this value amidst the increase in human activities, in line with an ecosystem-based approach to MSP [15] and the work of Holness et al. [92] who developed priority areas for biodiversity and nature-based activities in AB.

Figure 5.

The estimated value of Algoa Bay’s ecosystem services relative to the municipal budget.

This increase in the value of recreation and tourism reveals that our valuation was able to detect structural changes in ES over the 20 years and emphasises the dynamic nature of ES. Moreover, this dynamism demonstrates the importance of using multiple timesteps to develop meaningful policy interventions for ES. For example, tourism is sensitive to declines in environmental quality, which may incentivise policymakers and governments to invest, regulate and conserve marine and coastal systems [93]. This further encourages policymakers to assess synergies and conflicts between activities and the marine environment, and to reduce those that may negatively impact the value of these ES. It is recommended that policy and implementation incorporate ES in planning, inclusive of tourism, an important income-generating activity in AB, and other services that would support sustainable development in the area, particularly when including stakeholders in the process [29]. Further, to determine the impact of policy and regulations on ES requires additional research to investigate the feedback relationships and changes thereof under alternative management scenarios as tested in Vermeulen-Miltz [94].

An additional limitation of this study is that the valuation of ES is based solely on the spatial extent of the ecosystem and does not account for the ecological condition or health of the underlying ecosystems. As a result, observed increases in ES value reflect increased human use or demand for these services, rather than an improvement in the ecosystems’ capacity to provide them. For example, the existence value associated with declining species such as African penguins will likely diminish, yet this is not captured directly in the valuation [95]. Similarly, for the non-cultivated food provisioning service, the unchanging trend may also indicate that the ecosystem is operating at or near its provisioning capacity, and that the sector is either unable or unwilling to pay more for this service.

Therefore, if both ecosystem extent and condition had been integrated into the valuation framework, different trends may have emerged. Importantly, this means that increases in ES value cannot be interpreted as evidence of improving marine ecosystem health.

Using both conservative and alternative values as well as local and global beneficiaries, we were able to give a range of values and deal with uncertainty. Moreover, we were faced with a lack of well-developed frameworks when attempting to value the marine ecosystems in this study. For onshore and estuaries, most of the ES were valued using a range of valuation methods (mostly non-transfer), whereas the marine ecosystems were mostly valued using benefit transfer, owing to the lack of information and studies in the study area. The benefit transfer method is not without challenges and limitations (see Pascual et al. [21] for a more detailed description of the challenges). However, owing to resource and data constraints, it was the most pragmatic means of estimating the value of these marine ecosystems and including them in the study. Ignoring them would signal a nil value, which is per definition incorrect. Using the benefit transfer method is thus, despite its obvious weakness, superior to no value [96,97,98].

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first comprehensive economic valuation to consider multiple marine ES and provides a transparent approach to inform MSP in AB. Our study contributes to the very sparse literature of marine ES on the African continent at the local scale. This is notwithstanding the various limitations that had to be breached with respect to data. Data had to be collated from various sources and over a long period of time. That complicated matters since definitions of variables and the spatial scales thereof changed occasionally and had to be corrected to keep the integrity of the data and the variable intact. An advantage, however, is that the largest ecosystem service—namely, recreation and tourism services—also have the best and most complete set of data, and these are all market-based. Likewise, the cultivated and non-cultivated provisioning services made use of quality market-based data. The benefit transfer method, however, had to be used for supporting services, some of the cultural services, and all but waste dilution of the regulating services. This is due to the absence of reliable data and is a source of concern. Using the benefit transfer mechanism is more desirable than entering no data, but is a weak proxy, especially related to services that are highly context- and site-specific such as cultural and regulatory services. It is strongly recommended that a thorough local assessment of these is undertaken.

Our implementation of an ES valuation has provided a framework to make explicit the value that beneficiaries derive from marine ecosystems in an African context and provides a novel perspective on the valuation of ES in the coastal and marine ecosystems within South Africa. This framework can be replicated elsewhere in Africa, where there is a need to develop the ocean economy in an equitable and sustainable way. Moreover, it can be applied in other coastal and embayment areas for a comparative analysis and to support the national MSP process. This type of marine ecosystem valuation method can be used to support ocean planning at both national global scales and can contribute to measuring progress towards United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O., J.B., B.S. and A.T.L.; methodology, M.O., J.B., R.P., C.L., M.B., T.T., P.R. and R.P.; validation, E.M. J.B., M.O. and R.P.; formal analysis, M.O., J.B., R.P., C.L., M.B., T.T., P.R. R.P. and E.M.; investigation, M.O., J.B., R.P., C.L., M.B., T.T., P.R. and R.P.; data curation, M.O., J.B., R.P., C.L., M.B., T.T. and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O., J.B.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualisation, M.O., J.B. and R.P.; supervision, J.B.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, B.S. and A.T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of the Algoa Bay Marine Spatial Planning Community of Practice project supported by the DSI/NRF South African Research Chair in Marine Spatial Planning [grant number 98574], the Belmont Forum for the MARISCO project (Belmont Forum Award 03F0836A) and One Ocean Hub [UKRI GCRF grant no. NE/S008950/1].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Nelson Mandela University (H20-BES-DEV-003) on 7 December 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Leandri van der Elst for her editorial work throughout the project. We wish to also thank Anne Lemahieu and Hannah Truter for their valuable contributions and inputs. Finally, we would like to thank all stakeholders for their valuable insight along with the respective communities of practice.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Matthew Orolowitz, James Blignaut, Chase Lourens, Matthew Bentley, Twesigye Twekye, Pablo Rees and Rozanne Peacock were employed by the company ASSET Research. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Population of Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa, and of the globe between 2000 and 2019 (people, millions) [52,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106].

Table A1.

Population of Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa, and of the globe between 2000 and 2019 (people, millions) [52,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106].

| Beneficiaries | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.15 | 1.24 | 1.27 |

| Global | 6108 | 6517 | 6942 | 7383 | 7805 |

Table A2.

Data sources.

Table A2.

Data sources.

| Onshore | Coastal | Offshore | Coral Reefs | Estuaries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right of access | Industrial site values (A1) [107,108,109,110,111,112,113]: Industrial site values = Average site value × Size ×rates Initial research into directly obtaining the actual site values were unsuccessful. A proxy was used, in which the average site values per hectare were obtained and multiplied by the size of the ports. To obtain the right to access the port for each timestep on an annual basis, the previous calculation was multiplied by industrial property rates. | Port dues (A2) [[114,115] Appendix C]: The actual port dues were obtained directly from Transnet through the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) process. Port limits were obtained from the Department of Transport and were used to calculate the per hectare value and value per ecosystem of the port dues (accounting for MPAs and mariculture). Mariculture permits (A3) [116,117,118,119,120,121]: Mariculture permits = application fee + permit fee + right to engage in mariculture Licencing and permits fees were obtained in the Marine Living Resources Act of 1998 and subsequent iterations for the past 20 years. This right-of-access ecosystem service consists of fees to conduct mariculture operations. These values were summed. Only companies that actively partook in mariculture were included. Therefore, these values were only applied to for the Knysna Oyster Company. Fishing permits (A4): See offshore ecosystem for a summary of the valuation. | Port dues (A2): See coastal ecosystem for a summary of the valuation. Fishing Permits (A4) [Appendix C, [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129]]: No. of right holders in AB = No. of vessels in AB× Right holder: vessels in RSA The number of fishing vessels for the five commercial fisheries operating in Algoa Bay were obtained from the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) through the PAIA process. However, the right-of-access fees are based on right holders rather than on vessel. The national ratio of right holders to vessels was obtained from various sources and assumed to be constant. This ratio was multiplied by the number of vessels in Algoa Bay to obtain the number of right holders in bay. Total fees per fishery = Right holders × (Application fee + permit fee) + no. of vessels in AB*licence fees To get the total value per fishery, these right holders were subsequently multiplied by sum of the permit and application fees and added to the product of the number of vessels and licence fees of the vessels. | Industrial Site values (A1) [108,109,110,130]: Industrial Site values = Average site value × Size × rates The Coega and Baakens estuaries both occupy areas within port bounds. This area was taken out of the onshore ecosystem and reallocated to the estuary value. The same method was employed as in the onshore ecosystem. | |

| Food provisioning (non-cultivated) | Commercial fishing price (B1) [[55,129,131,132,133,134], Appendix C]: Market prices for each commercial fishery were obtained from the sources listed above. The value was deflated and inflated to the different timesteps. However, in some instances, market values were indicated in US dollars. These values were converted to rand-equivalent values using the PPP [55]. Catch data: See offshore ecosystem for a summary of the valuation. | Commercial fishing price (B1): See coastal ecosystem for a summary of the valuation. Catch data [Appendix C]: Total catch volumes (in tons) were obtained from the DFFE through the PAIA process for each fishery. | Subsistence fishing value (B2) [74]: The two estuaries identified, the Sundays and Swartkops estuaries, provide a subsistence fishing value estimate of the estuaries. The final annual estimate was used across all five timesteps by inflating and deflating the values to the various years. | ||

| Food and raw materials (cultivated) | Mariculture gross income (C1) [116]: Revenue = Total annual yield × price per yield The revenue was calculated by multiplying the total annual yield by the price per yield. These estimates were provided by the Knysna Oyster Company. | ||||

| Waste dilution | Waste dilution (D1) [[135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144], Appendix D]: Waste water dilution value = nutrient load entering coastal area × Cost of removing kg pollutant by WWTW The ocean’s ability to dilute wastewater is estimated by taking the capital replacement cost for wastewater treatment plants operating in Algoa Bay in treating the nutrient loads from untreated dissolved inorganic nitrogen and phosphorous discharged from wastewater treatment works as well as from the concentrations found at estuary mouths. | ||||

| Air quality regulation * | Air quality regulation (E1): ESVD [145]: Value = value per hectare (R/ha) × area (ha) This study calculated the amount of NOx, in the form of fine dust, captured by the ecosystem and estimated an amount per kilogram based on the cost that would have arisen from health damage. The values for the different biomes within the ecosystem were then averaged across to arrive at a final value per hectare for the onshore ecosystem. | Air quality regulation (E1): ESVD [66]: This study measured the amount of sulphur dioxide, fine particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and ozone removed under ‘no vegetation’ and ‘current vegetation’ scenarios by assessing the change in concentration, and a monetary benefit was then estimated on the basis of health benefits. The ‘no vegetation’ monetary value was then subtracted from the ‘current vegetation’ monetary value to reach a value per hectare amount. | |||

| Climate regulation * | Climate regulation (F1): ESVD [67]: This study employed a choice experiment to derive a value for the climate regulation service. A ‘series of CE choice tasks’ were presented to the participants, in which hypothetical scenarios were posed. From the answers of the participants, the authors estimated a value for the climate regulation service using a conditional logit model. | Climate regulation (F1): ESVD [68]: This study measured carbon sequestration from biomass samples. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was then used, which took seasonal variation into account, to value the amount of carbon sequestrated and stored. | Climate regulation (F1): ESVD [69]: The paper provided an in-depth assessment of carbon sequestration of salt marshes in South Africa and gave the range of values for the annual carbon dioxide equivalent reduction per hectare in salt marshes. | ||

| Moderation of extreme events * | Moderation of extreme events (G1): ESVD [70]: This study developed a three-step approach to value the moderation of extreme events in the UK. A public survey was conducted, in which the choice experiment method was used. Participatory workshops were used to overcome the complexity of the different policy scenarios. Following the collection of responses, an ecological weighting matrix was used to pool the judgement of experts over the “relative level of ecosystem services delivered by habitats”. | Moderation of extreme events (G1): ESVD [71]: This study estimated the value provided by the Danojon Reef in the Philippines for its ability to moderate extreme events using the contingent valuation method. A questionnaire was issued to a variety of individuals, such as tourists, residents, etc. The questionnaire elicited a willingness to pay (WTP) for this ecosystem service. The WTP measure provided by respondents was then manipulated to reflect all individuals who make use of the ecosystem services. | |||

| Erosion prevention * | Erosion prevention (H1): ESVD [72]: This study used the “expert survey” method to provide values for several services for the coastal system found in Guangxi Province, China. In total, 300 questionnaires were sent out to experts in the region. From these responses, the percentage of reduction in costs attributable to the erosion prevention was calculated. | Erosion prevention (H1): ESVD [73]: This study conducted interviews with reef users in the Solomon Islands, in which the WTP of interviewees were derived to construct an “artificial market for ecosystem services”. | |||

| Nutrient cycling * | Nutrient cycling (I1) [74]: This study was used to value the top twenty temperate estuaries in terms of nursery values by observing freshwater flows, the frequency and duration of the estuary mouth openings, which are considered to be the biggest factors affecting the estuarine biota. | ||||

| Water quality* | Water quality (J1) [[75,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153], Appendix D]: Water quality value = (pollutant concentration estuary head-pollutant concentration estuary mouth) × molar mass × Mean annual runoff × Cost of removing kg pollutant by WWTW The extent of phosphorous and nitrogen cycles operating in estuaries to remove dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and phosphorous (DIP) is estimated by taking the difference in average concentrations at the estuary mouth and head. A reduction in DIP and DIN is considered the treatment of the estuary in sinking these pollutants. The equivalent cost of treating similar nutrient loads with wastewater treatment plants is used to estimate value. | ||||

| Maintenance and protection of nursery and gene pool and life cycle * | Maintenance and protection of nursery and gene pool and life cycle (K1): ESVD [72]: This study focused on an area spanning 876 hectares in the Cairns Harbour Bay in Australia. A deterministic simulation model was employed to estimate the ability of the coastal system to maintain the stocks of different species living in the Bay. | Maintenance and protection of nursery and gene pool and life cycle (K1): ESVD [78]: This study estimated the value of the offshore ecosystem in the UK, arising from its ability to maintain its level of marine biodiversity. Using a goods and services approach, in which the goods and services produced by the offshore ecosystem’s marine biodiversity are valued. | |||

| Amenity value | Statutory payments (L1) [130,154,155,156]: Premium in property value = (amenity premium × Housing Price Index) × suburb extent The amenity values were adjusted using the FNB Housing Price Index. These premiums were summed providing a total amenity premium. The total amenity premium was multiplied by the total extent of three suburbs (Humewood, Northend and Summerstrand). Statutory payment = Premium in property value × ratio. Statutory payments were calculated by multiplying the premium in property value that was calculated in the previous step by the ratio of property rates to land value. Willingness to pay [108,109,157,158]: The willingness to pay premium for amenity values was calculated by collating sales transactions data from Property24 for each of the three suburbs where properties sold were counted and property value for each year summed. The number of properties sold was multiplied by the average property size to give the total extent of properties sold for that year. This extent of properties sold was then multiplied by the amenity value to provide the premium paid in the property sale (willingness to pay). | Amenity value (L1) [58,59,74,107,108,109,158]: Estimates for property values were obtained from Turpie and Clark [74] for the Sundays and Swartkops estuaries and were subsequently inflated/deflated. Amenity value = property value× ratio of property rate to land value × municipal rates Property rates were multiplied by the ratio of property rate to land value and then by the municipal rates to obtain the amenity value. | |||

| Recreation and tourism | Travel cost (M3) [101,102,103,104,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175]: Travel cost = total distance travel × rate per km The travel cost was calculated by measuring the total distance travelled by all domestic tourists each year from each of their respective provinces and multiplying it with the cost per distance (R/km). Opportunity cost (Residents)(M2) [52,105,176]: Opportunity cost = Residents using the beach × hours spent at beach × GDP/capita/hour The number of residents using the beach was multiplied by hours spent at the beach and cost of time (measured by the GDP per capita per hour). Opportunity cost (Domestic) (M2) [160,176]: Opportunity cost = domestic bed nights or visitor days × GDP/capita/day × moderation value GDP per capita per day was multiplied by both the visitor days and bed nights to give a total opportunity cost value. The opportunity cost of overnight visitors was moderated by 70% since had the tourists been at work, income would have been earned strictly during working hours, and not 24 h per day. Day visitors were moderated by 20%. Direct recreational spend (M1): See offshore ecosystem for a summary of the valuation. | Direct recreational spend Travel cost (M1) [160]: Direct recreational spend: Overnight value = overnight visitors× average spend overnight visitors. The total overnight spend value was calculated by multiplying the total number of overnight visitors multiplied with the average spend per overnight visitor. Tourists were separated into domestic and foreign tourists, with the average spend and duration of stay differing between the two. | Direct recreational spend (M1): See offshore ecosystem for a summary of the valuation. | Direct recreational spend (M1): See offshore ecosystem for a summary of the valuation. | Recreational fishing (M4) [177,178]: Fishing value = annual no. of hours × ratio of population To calculate the value of fishing along the estuaries, the annual number of fishing hours for the Sundays and Swartkops estuaries was then multiplied by the ratio of the year of interest to the population of NMB in 2007. The opportunity cost method was used to value this service to these fishermen. The GDP per capita per hour value was multiplied by the total annual fishing hours to generate an annual value per estuary. Recreational boating (M4) [179,180]: Annual no. of boating hours = boats per weekend day × boating days per year × people per boat × hours per trip To calculate the value of boating along the Swartkops and Sundays estuaries, the number of boats was multiplied by the number of boating days (weekend days and public holidays for each year) and then multiplied by both the average number of people per boat and the assumed duration of the trip (2 h). Value of boating = annual no. of boating hours × GDP/capita/hour The same opportunity cost method was applied to the total annual number of boating hours as was performed with the annual fishing hours (see the previous section) to obtain the annual value per estuary. |

| Spiritual, cognitive and other * | Spiritual, cognitive and other (N1): ESVD [67]: See onshore climate regulation for more detail explanation. This study employed a “series of CE choice tasks”, where hypothetical scenarios were posed to participants. From their answers, a value for the sense of place individuals felt using a conditional logit model was estimated. | Spiritual, cognitive and other (N1): ESVD [175]: This study gathered information about a knowledge network of universities, NGOs and public authority companies that made use of the coastal systems. The authors estimated the annual revenue of this knowledge network and calculated a percentage of this revenue that could be attributed to the coastal systems ecosystem in Holland. | Spiritual, cognitive and other (N1): ESVD [79]: This study investigated the opportunities that coral reefs provide for research and education in Martinique. They assessed the level of public spending that was directed towards providing opportunities for research and maintaining the reef so that knowledge could be gained from a well-functioning reef. | ||

| Existence and bequest * | Existence and bequest (O1): ESVD [80]: This study employed a contingent valuation method to provide a value for the coastal systems located in Spain. Both an “open format” survey, in which participants were only asked their WTP, as well as a “binary format”, in which interviewers offer a “guideline value” and participants indicate whether or not they would be willing to pay this amount for the continued existence of the coastal system, were used. From these responses, the authors estimated a binary logit model to derive values. | Existence and bequest (O1) [81]: This study estimated the value placed on the marine biome in the Western Cape, arising from individuals knowing the marine ecosystems are healthy. They used the contingent valuation method to elicit individual’s WTP to maintain the condition of the marine biome. Participants were asked how much they would be willing to contribute towards conservation efforts aimed at preserving the biodiversity in South Africa. | Existence and bequest (O1): ESVD [79,82,83,84,85]: Analogous studies on coral reefs found in Algoa Bay were not found. Therefore, values from a suite of different papers estimating the existence and bequest values for coral reefs around the world was used. Thus, an array of values was created. Quartiles were then calculated from the distribution of values, from which the second and third quartiles were used for the conservative and alternative values. |

* Denotes that these ecosystem services employed the benefit transfer method. The studies were obtained from the Ecosystem Services Valuation Database. The per hectare values were converted from USD to ZAR using PPP [55] and deflated to each timestep using the consumer price index [181]. All studies used in the benefit transfer were selected based on the comparability of scale and how recent the study was published (with more recent studies being favoured).

Appendix B

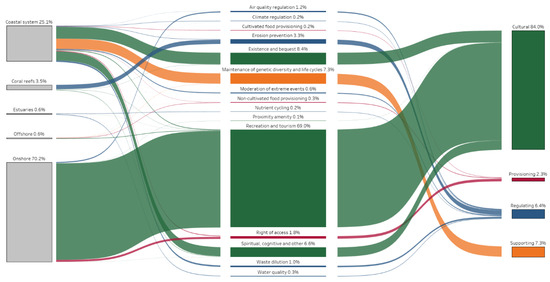

Appendix B.1. Local Beneficiaries

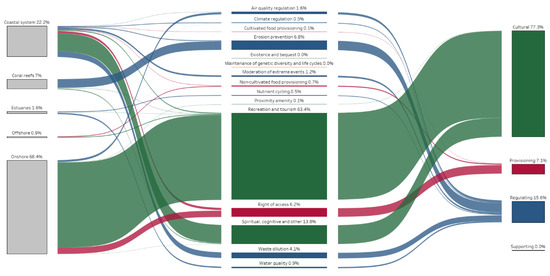

Figure A1.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the local beneficiaries for the year 2000 (Total value: USD 613.4 million).

Figure A2.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the local beneficiaries for the year 2005 (Total value: USD 805.7 million).

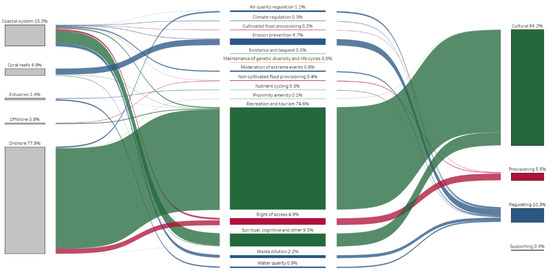

Figure A3.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the local beneficiaries for the year 2010 (Total value: USD 1257.3 million).

Figure A4.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the local beneficiaries for the year 2015 (Total value: USD 1 037.1 million).

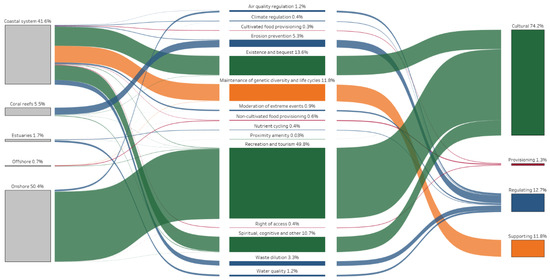

Figure A5.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the local beneficiaries for the year 2019 (Total value: USD 1695.9 million).

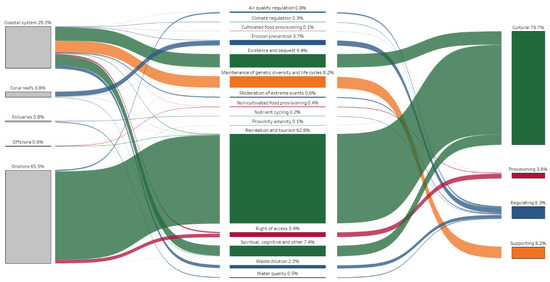

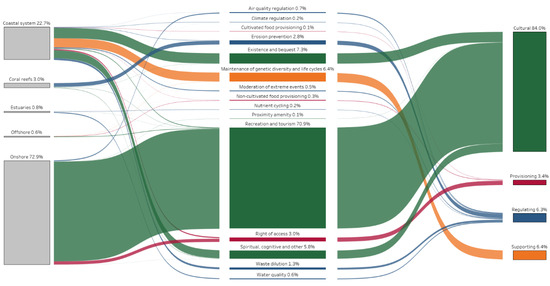

Appendix B.2. Global Beneficiaries

Figure A6.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the global beneficiaries for the year 2000 (Total value: USD 1127.3 million).

Figure A7.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the global beneficiaries for the year 2005 (Total value: USD 1454.0 million).

Figure A8.

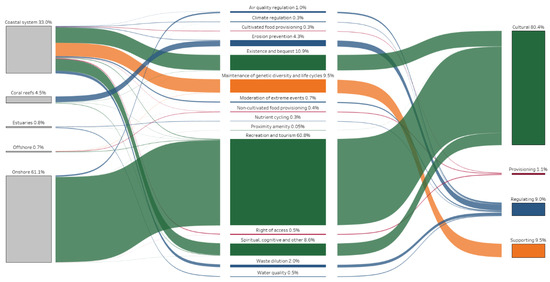

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the global beneficiaries for the year 2010 (Total value: USD 2073.0 million).

Figure A9.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the global beneficiaries for the year 2015 (Total value: USD 1932.3 million).

Figure A10.

Sankey diagram depicting the value of ecosystem services derived by the global beneficiaries for the year 2019 (Total value: USD 2787.9 million).

Appendix C. Data and Values Used to Estimate the Right-of-Access Values with Respect to the Fishing Values

| Year | Annual Catch of Shallow-Water Hake Merluccius capensis and Deep-Water Hake M. paradoxus | Squid Jig | Small Pelagic | Shark Longline | Inshore Trawl | Licence | Permits | Levy | Application Fees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tons | No. of Vessels | No. of Vessels | No. of Vessels | No. of Vessels | ZAR | ZAR | ZAR | ZAR | |

| a | b | c | d | e | (b + c + d + e) × Licence Fee of ZAR1318 | (b + c + d + e) × Permit Fee of ZAR831 | (a) × Offshore Hake Trawl Levy of ZAR227 | (b + C + e) × Commercial Permit of ZAR 240 + (d) × Large Pelagic Licence of ZAR9123 | |

| 2000 | 710.0 | 60 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 92,260 | 58,170 | 161,170 | 25,683 |

| 2001 | 790.0 | 64 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 101,486 | 63,987 | 179,330 | 18,480 |

| 2002 | 1000.0 | 68 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 108,076 | 68,142 | 227,000 | 19,680 |

| 2003 | 850.0 | 72 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 121,256 | 76,452 | 192,950 | 48,729 |

| 2004 | 700.0 | 76 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 129,164 | 81,438 | 158,900 | 59,052 |

| 2005 | 400.0 | 80 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 130,482 | 82,269 | 90,800 | 59,292 |

| 2006 | 338.6 | 82 | 15 | 6 | 16 | 156,842 | 98,889 | 76,857 | 81,858 |

| 2007 | 310.8 | 87 | 14 | 4 | 18 | 162,114 | 102,213 | 70,551 | 65,052 |

| 2008 | 1415.3 | 101 | 9 | 4 | 15 | 170,022 | 107,199 | 321,282 | 66,492 |

| 2009 | 1042.3 | 111 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 180,566 | 113,847 | 236,611 | 77,295 |

| 2010 | 1011.4 | 117 | 9 | 4 | 11 | 185,838 | 117,171 | 229,587 | 69,372 |

| 2011 | 824.6 | 121 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 183,202 | 115,509 | 187,173 | 60,009 |

| 2012 | 482.4 | 112 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 170,022 | 107,199 | 109,512 | 39,843 |

| 2013 | 286.7 | 94 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 144,980 | 91,410 | 65,080 | 35,283 |

| 2014 | 529.3 | 94 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 141,026 | 88,917 | 120,157 | 61,212 |

| 2015 | 1198.4 | 100 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 146,298 | 92,241 | 272,036 | 53,289 |

| 2016 | 1531.4 | 101 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 148,934 | 93,903 | 347,617 | 53,769 |

| 2017 | 2024.3 | 97 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 139,708 | 88,086 | 459,510 | 43,206 |

| 2018 | 2945.6 | 99 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 154,206 | 97,227 | 668,647 | 54,729 |

| 2019 | 934.3 | 113 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 170,022 | 107,199 | 212,096 | 57,609 |

| 2020 | 543.9 | 98 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 158,160 | 99,720 | 123,465 | 46,566 |

Symbols a–e in line 1 refer to column numbers and as applied in the subsequent formulas. Data sourced from the Transnet National Ports Authority (TNPA). Unpublished data relating to port dues for Ngqura and Port Elizabeth for 2000–2020 accessed online via https://www.gov.za/documents/promotion-access-information-act, accessed on 10 September 2025. TNPA, Gqeberha, 2023. TNPA PAIA number 002, 27 November 2023. Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. Unpublished data relating to number of vessels fishing and catch data per year in Algoa Bay for each of the five commercially important fisheries from 2000 to 2020 accessed online via https://www.gov.za/documents/promotion-access-information-act, accessed on 10 September 2025. DFFE, Pretoria, 2023. DFFE PAIA numbers 233246/227791/227792/227793/227796/227795, 21 August 2023.

Appendix D. Data and Values Used to Estimate the Waste Dilution Values

| Physical Data | Nutrient Data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample ID | Date | Site | Phosphate (umol/L) | Silicate (umol/L) | Nitrate (umol/L) | Nitrite (umol/L) | Ammonium (umol/L) |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2019/04/24 | S1 | 0.73 | 5.50 | 1.69 | 0.30 | 1.89 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2019/04/24 | S1 | 0.71 | 4.30 | 2.01 | 0.24 | 1.76 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2019/04/24 | S1 | 0.76 | 4.24 | 2.09 | 0.21 | 1.68 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2019/04/24 | M1 | 0.85 | 4.61 | 2.46 | 0.25 | 2.65 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2019/04/24 | M1 | 0.66 | 4.79 | 2.54 | 0.23 | 2.17 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2019/04/24 | M1 | 0.67 | 4.43 | 2.57 | 0.21 | 1.83 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2019/04/24 | B1 | 0.61 | 4.63 | 2.26 | 0.23 | 2.09 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2019/04/24 | B1 | 0.56 | 4.18 | 2.53 | 0.25 | 1.36 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2019/04/24 | B1 | 0.46 | 4.53 | 2.45 | 0.19 | 1.78 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2019/04/24 | S6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2019/04/24 | S6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2019/04/24 | S6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2019/07/24 | S1 | 0.55 | 4.86 | 3.17 | 0.49 | 3.24 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2019/07/24 | S1 | 0.91 | 5.04 | 3.60 | 0.45 | 2.70 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2019/07/24 | S1 | 0.70 | 4.21 | 3.15 | 0.37 | 3.35 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2019/07/24 | M1 | 0.67 | 3.62 | 2.78 | 0.36 | 2.46 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2019/07/24 | M1 | 0.71 | 5.05 | 3.62 | 0.45 | 3.26 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2019/07/24 | M1 | 0.78 | 5.42 | 4.04 | 0.44 | 2.60 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2019/07/24 | B1 | 0.87 | 4.84 | 3.53 | 0.39 | 3.16 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2019/07/24 | B1 | 0.73 | 4.92 | 3.61 | 0.44 | 3.65 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2019/07/24 | B1 | 0.85 | 5.11 | 3.92 | 0.44 | 3.04 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2019/07/24 | S6 | 55.64 | 63.59 | 91.40 | 8.69 | 13.12 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2019/07/24 | S6 | 58.89 | 58.79 | 97.17 | 9.96 | 23.64 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2019/07/24 | S6 | 52.83 | 44.70 | 56.92 | 5.39 | 26.82 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2019/11/04 | S1 | 0.75 | 3.01 | 0.96 | 0.16 | 1.57 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2019/11/04 | S1 | 0.75 | 2.78 | 1.04 | 0.13 | 1.50 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2019/11/04 | S1 | 0.81 | 3.13 | 1.26 | 0.19 | 1.31 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2019/11/04 | M1 | 0.79 | 2.85 | 0.97 | 0.15 | 1.99 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2019/11/04 | M1 | 0.75 | 2.89 | 1.14 | 0.17 | 1.43 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2019/11/04 | M1 | 0.75 | 4.49 | 1.12 | 0.16 | 1.13 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2019/11/04 | B1 | 0.80 | 3.73 | 1.12 | 0.19 | 1.79 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2019/11/04 | B1 | 0.74 | 3.06 | 1.06 | 0.17 | 1.36 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2019/11/04 | B1 | 0.83 | 3.19 | 1.16 | 0.19 | 1.80 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2019/11/04 | S6 | 93.06 | 35.00 | 16.07 | 7.19 | 3.75 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2019/11/04 | S6 | 94.15 | 35.01 | 15.33 | 7.49 | 0.90 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2019/11/04 | S6 | 75.91 | 34.41 | 12.10 | 5.92 | 1.54 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2020/02/04 | S1 | 0.70 | 2.42 | 1.92 | 0.68 | 1.52 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2020/02/04 | S1 | 0.77 | 2.14 | 2.15 | 0.74 | 1.29 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2020/02/04 | S1 | 0.79 | 1.71 | 1.90 | 0.67 | 1.51 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2020/02/04 | M1 | 0.70 | 1.59 | 1.81 | 0.63 | 1.20 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2020/02/04 | M1 | 0.70 | 1.56 | 1.87 | 0.63 | 1.33 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2020/02/04 | M1 | 0.72 | 1.20 | 2.01 | 0.66 | 1.31 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2020/02/04 | B1 | 0.67 | 1.10 | 1.60 | 0.59 | 0.97 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2020/02/04 | B1 | 0.65 | 1.21 | 1.73 | 0.63 | 0.98 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2020/02/04 | B1 | 0.68 | 1.35 | 1.80 | 0.64 | 1.03 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2020/02/04 | S6 | 73.85 | 35.62 | 59.50 | 25.51 | 8.46 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2020/02/04 | S6 | 74.33 | 42.75 | 72.14 | 26.36 | 11.44 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2020/02/04 | S6 | 86.07 | 43.18 | 73.95 | 25.73 | 11.52 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2020/06/05 | S1 | 7.86 | 23.04 | 10.42 | 1.91 | 9.05 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2020/06/05 | S1 | 7.90 | 23.09 | 10.39 | 1.91 | 9.35 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2020/06/05 | S1 | 7.96 | 23.23 | 10.53 | 1.97 | 9.79 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2020/06/05 | M1 | 7.77 | 22.38 | 9.96 | 1.76 | 8.59 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2020/06/05 | M1 | 7.84 | 22.48 | 10.05 | 1.78 | 8.18 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2020/06/05 | M1 | 7.92 | 22.50 | 10.12 | 1.80 | 8.21 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2020/06/05 | B1 | 7.71 | 21.87 | 10.21 | 1.92 | 9.17 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2020/06/05 | B1 | 7.75 | 21.77 | 10.03 | 1.91 | 7.75 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2020/06/05 | B1 | 7.52 | 21.77 | 9.93 | 1.89 | 8.21 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2020/06/05 | S6 | 71.01 | 147.94 | 61.19 | 24.02 | 61.87 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2020/06/05 | S6 | 69.72 | 148.96 | 60.51 | 23.29 | 62.50 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2020/06/05 | S6 | 70.47 | 148.87 | 59.75 | 23.68 | 61.13 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2020/06/25 | S1 | 1.57 | 7.52 | 4.54 | 0.65 | 2.30 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2020/06/25 | S1 | 1.51 | 7.85 | 4.26 | 0.60 | 1.19 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2020/06/25 | S1 | 1.56 | 7.52 | 4.39 | 0.62 | 2.24 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2020/06/25 | M1 | 1.55 | 7.65 | 4.06 | 0.56 | 1.52 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2020/06/25 | M1 | 1.52 | 7.80 | 4.16 | 0.58 | 3.19 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2020/06/25 | M1 | 1.54 | 7.93 | 4.46 | 0.60 | 2.37 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2020/06/25 | B1 | 1.46 | 8.20 | 4.23 | 0.59 | 1.11 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2020/06/25 | B1 | 1.42 | 7.84 | 4.27 | 0.60 | 1.43 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2020/06/25 | B1 | 1.38 | 7.83 | 4.31 | 0.59 | 1.19 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2020/06/25 | S6 | 63.09 | 128.08 | 65.68 | 23.89 | 60.61 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2020/06/25 | S6 | 62.90 | 129.02 | 64.91 | 23.92 | 61.18 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2020/06/25 | S6 | 62.36 | 129.30 | 67.17 | 24.00 | 56.54 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2020/09/22 | S1 | 0.97 | 6.19 | 4.30 | 0.68 | 2.88 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2020/09/22 | S1 | 1.03 | 6.61 | 4.63 | 0.71 | 2.96 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2020/09/22 | S1 | 1.04 | 6.52 | 4.66 | 0.70 | 2.92 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2020/09/22 | M1 | 1.00 | 6.31 | 4.49 | 0.65 | 2.82 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2020/09/22 | M1 | 1.01 | 6.50 | 4.64 | 0.67 | 3.03 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2020/09/22 | M1 | 1.09 | 7.13 | 5.10 | 0.74 | 2.91 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2020/09/22 | B1 | 1.00 | 7.56 | 4.59 | 0.64 | 3.40 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2020/09/22 | B1 | 1.04 | 6.50 | 4.39 | 0.64 | 2.99 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2020/09/22 | B1 | 1.03 | 6.30 | 4.31 | 0.65 | 3.01 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2020/09/22 | S6 | 78.43 | 28.64 | 136.74 | 24.98 | 73.34 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2020/09/22 | S6 | 81.35 | 28.53 | 136.54 | 24.51 | 78.93 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2020/09/22 | S6 | 77.49 | 28.67 | 126.92 | 24.01 | 77.94 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2020/11/12 | S1 | 4.17 | 10.64 | 3.29 | 0.32 | 0.66 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2020/11/12 | S1 | 4.45 | 11.11 | 3.51 | 0.34 | 0.79 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2020/11/12 | S1 | 4.44 | 10.27 | 2.62 | 0.36 | 0.16 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2020/11/12 | M1 | 3.77 | 8.92 | 2.02 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2020/11/12 | M1 | 3.87 | 12.04 | 3.16 | 0.27 | 0.88 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2020/11/12 | M1 | 3.82 | 8.72 | 1.87 | 0.22 | 0.30 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2020/11/12 | B1 | 4.37 | 10.19 | 2.26 | 0.29 | 0.38 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2020/11/12 | B1 | 4.86 | 11.97 | 2.78 | 0.34 | 0.50 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2020/11/12 | B1 | 4.88 | 11.89 | 2.70 | 0.34 | 0.46 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2020/11/12 | S6 | 62.00 | 59.35 | 68.13 | 23.83 | 98.75 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2020/11/12 | S6 | 62.35 | 59.51 | 67.11 | 23.48 | 95.79 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2020/11/12 | S6 | 61.80 | 58.70 | 66.51 | 23.26 | 97.04 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2021/01/26 | S1 | 10.46 | 24.83 | −0.45 | 0.24 | 1.16 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2021/01/26 | S1 | 10.49 | 24.43 | −0.22 | 0.20 | 1.14 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2021/01/26 | S1 | 10.69 | 24.60 | −0.61 | 0.16 | 0.94 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2021/01/26 | M1 | 10.58 | 25.67 | 0.99 | 0.19 | 0.74 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2021/01/26 | M1 | 10.86 | 25.46 | 0.91 | 0.18 | 1.13 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2021/01/26 | M1 | 10.39 | 24.21 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 0.78 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2021/01/26 | B1 | 10.22 | 26.76 | −0.55 | 0.15 | 0.94 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2021/01/26 | B1 | 10.30 | 23.44 | −0.63 | 0.13 | 0.94 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2021/01/26 | B1 | 10.12 | 23.91 | −0.76 | 0.14 | 1.14 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2021/01/26 | S6 | 94.69 | 130.09 | 41.99 | 18.84 | 196.84 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2021/01/26 | S6 | 95.97 | 123.32 | 37.17 | 17.68 | 198.14 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2021/01/26 | S6 | 98.47 | 123.84 | 33.71 | 16.19 | 195.07 |

| Sunday’s S1S1 | 2021/03/26 | S1 | 1.58 | 98.92 | 3.31 | 0.30 | 2.88 |

| Sunday’s S1S2 | 2021/03/26 | S1 | 1.10 | 77.62 | 3.57 | 0.27 | 1.65 |

| Sunday’s S1S3 | 2021/03/26 | S1 | 1.74 | 75.95 | 4.06 | 0.29 | 1.77 |

| Sunday’s S1B1 | 2021/03/26 | B1 | 1.56 | 73.21 | 4.46 | 0.31 | 1.34 |

| Sunday’s S1B2 | 2021/03/26 | B1 | 1.48 | 77.12 | 3.30 | 0.22 | 0.95 |

| Sunday’s S1B3 | 2021/03/26 | B1 | 1.29 | 71.28 | 3.07 | 0.31 | 1.30 |

| Sunday’s S6S1 | 2021/03/26 | S6 | 3.68 | 127.53 | 22.48 | 0.58 | 1.05 |

| Sunday’s S6S2 | 2021/03/26 | S6 | 3.76 | 154.67 | 32.82 | 0.65 | 1.23 |

| Sunday’s S6S3 | 2021/03/26 | S6 | 4.08 | 224.58 | 35.31 | 0.73 | 1.24 |

| Sunday’s S6B1 | 2021/03/26 | B6 | 3.96 | 289.23 | 31.69 | 1.07 | 1.97 |

| Sunday’s S6B2 | 2021/03/26 | B6 | 3.28 | 261.72 | 16.88 | 0.53 | 0.96 |

| Sunday’s S6B3 | 2021/03/26 | B6 | 4.08 | 284.38 | 29.21 | 0.73 | 1.36 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2021/05/07 | S1 | 5.40 | 17.41 | 5.02 | 1.06 | 4.30 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2021/05/07 | S1 | 4.67 | 14.13 | 4.48 | 0.85 | 3.85 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2021/05/07 | S1 | 5.88 | 18.60 | 5.68 | 1.11 | 4.58 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2021/05/07 | M1 | 8.47 | 27.05 | 7.87 | 1.51 | 6.01 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2021/05/07 | M1 | 9.12 | 29.64 | 8.59 | 1.63 | 6.46 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2021/05/07 | M1 | 10.36 | 34.06 | 9.60 | 1.83 | 7.14 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2021/05/07 | B1 | 2.49 | 8.54 | 2.75 | 0.46 | 2.55 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2021/05/07 | B1 | 2.18 | 5.84 | 2.38 | 0.41 | 2.26 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2021/05/07 | B1 | 2.63 | 6.84 | 2.82 | 0.48 | 2.58 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2021/05/07 | S6 | 117.97 | 208.28 | 26.09 | 20.65 | 93.93 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2021/05/07 | S6 | 118.27 | 223.37 | 19.95 | 17.11 | 91.92 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2021/05/07 | S6 | 116.87 | 213.69 | 24.09 | 19.86 | 91.63 |

| Sunday’s S1S1 | 2021/06/10 | S1 | 0.65 | 34.22 | 2.64 | 0.27 | 1.54 |

| Sunday’s S1S2 | 2021/06/10 | S1 | 1.07 | 66.19 | 4.27 | 0.45 | 1.12 |

| Sunday’s S1S3 | 2021/06/10 | S1 | 1.02 | 58.42 | 3.74 | 0.37 | 1.58 |

| Sunday’s S1B1 | 2021/06/10 | B1 | 0.87 | 43.62 | 3.37 | 0.33 | 1.46 |

| Sunday’s S1B2 | 2021/06/10 | B1 | 0.77 | 34.79 | 2.74 | 0.26 | 1.30 |

| Sunday’s S1B3 | 2021/06/10 | B1 | 0.97 | 61.01 | 3.90 | 0.41 | 1.38 |

| Sunday’s S6S1 | 2021/06/10 | S6 | 2.53 | 219.99 | 27.02 | 0.33 | 0.99 |

| Sunday’s S6S2 | 2021/06/10 | S6 | 2.33 | 183.35 | 24.30 | 0.28 | 1.16 |

| Sunday’s S6S3 | 2021/06/10 | S6 | 2.01 | 158.78 | 24.39 | 0.30 | 1.07 |

| Sunday’s S6B1 | 2021/06/10 | B6 | 2.59 | 221.48 | 24.29 | 0.31 | 1.02 |

| Sunday’s S6B2 | 2021/06/10 | B6 | 2.38 | 210.05 | 19.06 | 0.26 | 1.04 |

| Sunday’s S6B3 | 2021/06/10 | B6 | 2.43 | 226.63 | 18.97 | 0.26 | 1.22 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2021/07/12 | S1 | 1.18 | 4.63 | 2.05 | 0.37 | 3.88 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2021/07/12 | S1 | 1.23 | 4.84 | 2.49 | 0.32 | 3.58 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2021/07/12 | S1 | 1.28 | 4.91 | 2.88 | 0.33 | 3.92 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2021/07/12 | M1 | 1.37 | 5.35 | 2.92 | 0.33 | 3.02 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2021/07/12 | M1 | 1.34 | 4.97 | 3.17 | 0.32 | 3.49 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2021/07/12 | M1 | 1.16 | 4.39 | 2.46 | 0.27 | 2.87 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2021/07/12 | B1 | 0.90 | 2.82 | 1.58 | 0.17 | 2.31 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2021/07/12 | B1 | 1.22 | 5.06 | 2.43 | 0.30 | 3.00 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2021/07/12 | B1 | 1.48 | 5.50 | 3.52 | 0.36 | 4.23 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2021/07/12 | S6 | 102.28 | 151.85 | 102.21 | 30.28 | 61.79 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2021/07/12 | S6 | 101.26 | 124.84 | 92.49 | 27.97 | 60.26 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2021/07/12 | S6 | 105.42 | 165.33 | 94.12 | 29.73 | 62.07 |

| Sunday’s S1S1 | 2021/09/28 | S1 | 0.40 | 8.49 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.79 |

| Sunday’s S1S2 | 2021/09/28 | S1 | 0.46 | 22.72 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.66 |

| Sunday’s S1S3 | 2021/09/28 | S1 | 0.32 | 10.00 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Sunday’s S1B1 | 2021/09/28 | B1 | 0.28 | 4.57 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Sunday’s S1B2 | 2021/09/28 | B1 | 0.28 | 5.43 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Sunday’s S1B3 | 2021/09/28 | B1 | 0.25 | 4.64 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.52 |

| Sunday’s S6S1 | 2021/09/28 | S6 | 2.78 | 132.82 | 15.82 | 0.22 | 1.72 |

| Sunday’s S6S2 | 2021/09/28 | S6 | 2.87 | 132.05 | 15.86 | 0.47 | 2.38 |

| Sunday’s S6S3 | 2021/09/28 | S6 | 2.82 | 134.16 | 15.41 | 0.49 | 1.85 |

| Sunday’s S6B1 | 2021/09/28 | B6 | 2.86 | 132.48 | 15.12 | 0.51 | 1.91 |

| Sunday’s S6B2 | 2021/09/28 | B6 | 2.84 | 137.34 | 14.88 | 0.50 | 1.97 |

| Sunday’s S6B3 | 2021/09/28 | B6 | 2.81 | 132.50 | 14.79 | 0.50 | 1.95 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2021/10/20 | S1 | 3.52 | 2.65 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 2.55 |

| Swartkops S1S2 | 2021/10/20 | S1 | 4.62 | 6.49 | 0.90 | 0.28 | 2.33 |

| Swartkops S1S3 | 2021/10/20 | S1 | 3.66 | 2.88 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 2.21 |

| Swartkops S1M1 | 2021/10/20 | M1 | 4.15 | 4.80 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 1.80 |

| Swartkops S1M2 | 2021/10/20 | M1 | 4.67 | 5.88 | 0.92 | 0.29 | 2.65 |

| Swartkops S1M3 | 2021/10/20 | M1 | 4.55 | 6.20 | 1.11 | 0.26 | 2.66 |

| Swartkops S1B1 | 2021/10/20 | B1 | 4.80 | 6.70 | 0.67 | 0.20 | 1.83 |

| Swartkops S1B2 | 2021/10/20 | B1 | 4.98 | 7.05 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 1.95 |

| Swartkops S1B3 | 2021/10/20 | B1 | 4.13 | 4.00 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 1.83 |

| Swartkops S6S1 | 2021/10/20 | S6 | 126.35 | 121.31 | 88.16 | 40.80 | 107.97 |

| Swartkops S6S2 | 2021/10/20 | S6 | 131.09 | 91.53 | 73.90 | 34.83 | 95.39 |

| Swartkops S6S3 | 2021/10/20 | S6 | 135.23 | 124.38 | 80.91 | 39.08 | 107.69 |

| Swartkops S1S1 | 2022/01/27 | S1 | 0.37 | 3.77 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 8.95 |