Abstract

This study conducted a quasi-natural experiment on Chinese mutual funds that signed the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI) to examine whether institutional investors’ ESG commitments reduce ESG rating disagreements among their portfolio firms. We find that firms held by UNPRI-signatory investors exhibit significantly less ESG rating disagreement than those held by non-UNPRI investors. We further demonstrate that this effect operates through two channels: improved ESG disclosure quality and increased external ESG attention. Corporate governance and industry ESG sensitivity positively moderates the relationship between institutional investors’ ESG commitments and ESG rating disagreement. Moreover, the mitigating effect is more pronounced for domestic rating agencies. This study not only provides evidence for the role of institutional investors in ESG development but also identifies potential pathways to reduce ESG rating discrepancies, offering insights into enhancing the reliability of ESG rating outcomes.

1. Introduction

ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) ratings are developed by independent third-party agencies that conduct comprehensive assessments of companies’ sustainability efforts across environmental, social, and governance (ESG) dimensions. Market participants may base decisions on ESG rating outcomes. As an investment tool, ESG ratings should be accurate and reliable. However, the absence of a globally unified ESG assessment framework leads to significant methodological differences among rating agencies [1,2]. Consequently, the same company may receive vastly different ESG ratings from different agencies, potentially influencing investor decisions and even affecting capital market stability.

As ESG investment principles gain widespread adoption, an increasing number of Chinese public funds are signing the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI). Initiated by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the UNPRI principles primarily advocate for signatories to incorporate ESG factors into investment decisions.

The effectiveness of current ESG commitments made by institutional investors in reducing ESG rating discrepancies remains controversial. Driven by reputational and green transition objectives, institutional investors actively push companies to enhance ESG disclosure quality to fulfill commitments [3,4,5] and coordinate with external stakeholders to jointly address these discrepancies [6], significantly mitigating rating divergence. Conversely, other scholars express skepticism, noting that institutional investors adhering to the UNPRI may collude with companies to engage in “greenwashing” to pursue their own objectives, potentially exacerbating ESG rating discrepancies [2,6]. Thus, this study asks, Can the monitoring effect of signing the UNPRI influence ESG rating discrepancies among the companies in which signatories hold stakes?

Through conducting a quasi-natural experiment on Chinese public funds’ adoption of the UNPRI principles, this study investigates whether institutional investors’ commitment to ESG investment significantly attenuates ESG rating disagreement among their portfolio firms. We first document that firms held by ESG-committed institutional investors exhibit lower ESG rating divergence compared to those held by non-ESG-committed investors, indicating that such commitments help mitigate rating disagreements. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this effect operates through two key channels: improved quality of ESG disclosures and increased external ESG attention. Corporate governance and industry ESG sensitivity positively moderate the relationship between institutional investors’ ESG commitments and ESG rating disagreement. We also find that the disagreement-mitigating effect of institutional investors’ ESG commitments is more pronounced in ratings issued by domestic ESG agencies.

The contributions of this study can be summarized as follows.

This study makes a theoretical contribution by being the first to investigate the relationship between institutional investors’ ESG commitments and ESG rating disagreements. It extends the literature in two key ways. First, it shifts the focus from the economic consequences of ESG funds, a well-researched area but predominantly in European and American contexts [2,5,6,7], to the under-explored factor of rating disagreement, anchoring this inquiry within China’s rapidly evolving ESG ecosystem. Second, while existing research on the causes of rating discrepancies has centered on corporate disclosure behavior [8,9,10], this study demonstrates that institutional investors, specifically UNPRI signatories, play a critical role. Our finding that their ESG commitments effectively mitigate rating discrepancies among portfolio companies opens up a new pathway for reducing this form of market divergence.

From a practical perspective, this study offers actionable guidance for key market participants. For regulators, it provides insights for designing incentive policies that promote long-term sustainable investment. For asset managers, it confirms that UNPRI membership enhances professional reputation and risk management capabilities. For investee companies, it demonstrates that engaging responsible investors reduces ESG rating discrepancies, thereby stabilizing market expectations and lowering financing costs.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

The burgeoning field of ESG investing has been simultaneously enabled and complicated by the proliferation of ESG ratings. A foundational and persistent challenge in this domain is the widespread disagreement in ratings provided by different agencies. A growing body of literature has sought to diagnose the sources of this divergence. Seminal work by Berg et al. [2] aptly termed this phenomenon “aggregate confusion,” attributing it to systematic differences in measurement—encompassing rating scope, distinct indicator selection, and varying weightings assigned to the indicators. This inherent subjectivity is exacerbated by the nature of corporate ESG disclosure, which often relies heavily on qualitative narratives and non-financial metrics, creating ample room for interpretation and, at times, corporate impression management [8]. The consequences are significant, as this rating uncertainty can undermine investor confidence and distort capital allocation [10,11]. The Chinese context adds a critical layer of complexity to this global issue. As highlighted by Chen et al. [1], domestic rating agencies like Huazheng inherently prioritize indicators with distinctive Chinese characteristics, such as targeted poverty alleviation and rural revitalization, whereas global giants like MSCI emphasize universal issues like data security. This fundamental divergence in evaluative focus between local and international raters ensures that ESG rating disagreement is not merely a methodological artifact but is deeply embedded in institutional and cultural contexts.

Parallel to the research on rating divergence, there is a vast literature that examined the role of institutional investors as corporate monitors. A prominent strand of this research investigated whether investors committed to ESG principles, such as signatories to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI), effect meaningful change. One perspective, grounded in theories of shareholder activism, posits that these investors are potent forces for good. Studies, primarily in Western contexts, found that such investors actively engage with portfolio firms through dialog and shareholder proposals, leading to tangible improvements in ESG disclosure quality and overall performance [12,13]. This “positive monitoring” view suggests that by improving the underlying ESG practices and the transparency of reporting, these investors should logically provide rating agencies with a clearer, more consistent signal. However, a more skeptical perspective, informed by agency theory, warns of potential “greenwashing” or symbolic compliance. Critics argue that the pressure on funds to demonstrate ESG credentials may lead to collusion with portfolio firms for selective disclosure or manipulation of ESG reports, ultimately obfuscating true performance and potentially exacerbating rating discrepancies [3,14,15,16].

Despite the depth of these two parallel streams of research, a critical nexus remains underexplored. While we understand the causes of ESG rating disagreement and have debated the real-world impacts of ESG investors, there is a conspicuous lack of direct evidence linking the two. Specifically, it remains an open empirical question whether the entry of ESG-committed institutional investors serves to clarify or further muddy the informational waters for rating agencies. Does their monitoring activity resolve the “aggregate confusion” or does it introduce new noise? This question is particularly salient in China’s policy-driven ESG market, where the motivations and impacts of adopting global frameworks like the UNPRI may differ from those in developed markets. Our study directly addresses this gap. We conducted a quasi-natural experiment of Chinese funds signing the UNPRI to provide the first causal evidence testing these competing channels, thereby connecting the literature on rating divergence with that on institutional investor impact, and doing so within a critically important yet distinct institutional setting.

2.2. Hypotheses Development

From the perspective of sources of disagreement, public ESG disclosure by companies often contains a significant amount of qualitative information. Even when quantitative data is provided, it frequently consists of non-monetary metrics, such as carbon dioxide emissions. Furthermore, the content and format of ESG reports can vary significantly across firms, creating challenges for ESG rating agencies in understanding and effectively utilizing the relevant information [8]. Current ESG reporting standards lack harmonization and standardization, while regulatory coverage remains inadequate. As a result, companies may utilize ESG disclosure for impression management, embellishing their ESG practices. Therefore, the authenticity and accuracy of ESG disclosure remain underexamined. Consequently, the inconsistent quality of ESG disclosure among listed companies frequently results in substantial discrepancies in the ESG rating assigned to the same company by different rating agencies.

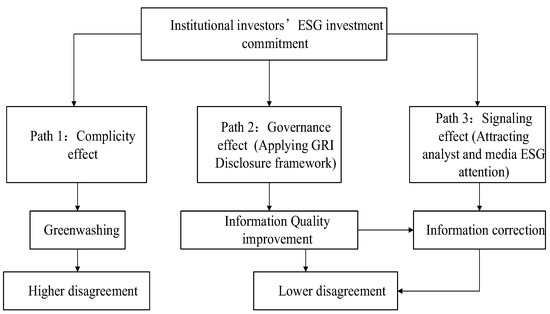

From the perspective of the fund, the current UNPRI signature mainly alleviates ESG rating differences through the following two paths:

(1) Information quality improvement: The PRI Initiative requires signatory organizations to commit to quality gatekeeping of ESG disclosure of the companies in their portfolio. In order to fulfill their commitments, the institutional investors will urge their holdings to proactively improve the quality of their ESG disclosure. Institutional investors can communicate directly with investees by starting ESG dialogs to improve corporate ESG-related disclosure [17,18,19]. Krueger et al. [17] asked 406 institutional investors from around the world and found that 43% of respondents had influenced their corporate climate risk governance by engaging in direct dialog with management. In addition to engaging in dialog, institutional investors can actively exercise their shareholder rights to improve the quality of corporate ESG disclosure through voting and proposing shareholder motions. According to a report released by nonprofit Ceres, 241 shareholder motions on ESG issues were proposed in 2022, with a 60 percent increase year-over-year. Of these, 48% won corporate commitments or were passed by a majority vote, indicating that these motions are expected to have a real impact on corporate ESG governance. By enhancing information disclosure—such as encouraging or requiring portfolio companies to adopt comparable reporting frameworks like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards—more comparable ESG information can be provided. This approach fundamentally mitigates rating discrepancies stemming from information asymmetry [20,21].

(2) UNPRI institutional investors entry can play a signaling role, which in turn attracts more ESG attention from media and analysts to correct rating disagreement. Media attention and analyst attention, as strong external monitoring mechanisms, can effectively curb the corporate cover-up of negative ESG information by management. Simultaneously, the growing market demand for corporate ESG information encourages companies to disclose more ESG-related data. Due to the lack of ESG report disclosure quality and the whitewashing of ESG reports by firms, the results of ESG rating of the same firm by different rating agencies tend to diverge significantly [22,23]. The media attention and analyst attention triggered by UNPRI institutional investors can bring richer information references for rating agencies, which in turn reduces the disagreement of rating agencies due to insufficient information.

H1a:

Institutional investors’ ESG investment commitments are negatively associated with ESG rating disagreement.

The entry of UNPRI institutional investors may increase the incentives for companies to “greenwash” their ESG disclosure, which in turn may exacerbate ESG rating disagreement. Due to the agency problem between institutional investors and firms, institutional investors are judging the validity of their investments based on the information disclosed in corporate ESG reports. For UNPRI institutional investors, corporate ESG performance is an important factor in an institutional investor’s choice of whether to continue investing. In this context, to prevent the withdrawal of UNPRI institutional investors resulting from insufficient ESG performance, companies may selectively disclose ESG information. Ultimately, this affects the decisions of the rating agencies [3,23,24].

Institutional investors primarily focus on profitability and will take any actions that serve this goal. The PRI Initiative commits signatory organizations to enhancing the ESG disclosure of the companies in their portfolios. For companies that do not meet ESG performance expectations, UNPRI institutional investors may collaborate with management to manipulate ESG disclosure, aiming to project an image of compliance with commitments. This practice undermines the consistency of ESG ratings. The specific assumptions are shown in Figure 1.

H1b:

Institutional investors’ ESG investment commitments are positively correlated with ESG rating disagreement.

Figure 1.

The path of institutional investors’ ESG Commitments to ESG rating disagreement.

3. Data and Variables

3.1. Sample Source and Processing

Most ESG rating agencies have focused exclusively on rating Chinese A-share listed companies since 2015. Consequently, this paper analyzes the effect of voluntary ESG regulation on the disagreement of ESG ratings among shareholding firms, using Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share listed companies as the research subjects from 2015 to 2022. In this paper, the initial sample is screened as follows: (1) Excluding ST and *ST type companies with poor operating conditions; (2) excluding samples with missing data, and finally obtaining 27,003 firm-year observations. To mitigate the effects of extreme values, this paper shrinks all continuous variables at the 1% and 99% quantiles. We collect the ESG rating data including multiple sources: FTSE Russell, Shanghai Huazheng Index Information Service Co., Ltd., Susallwave, Beijing SynTao Green Finance Consulting Co., Ltd., Bloomberg, and Wind.

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Explanatory Variable

The explanatory variable Dis is ESG rating disagreement. With the development and promotion of the concept of responsible investment, many ESG rating systems have emerged, which differ in terms of evaluation criteria, reference indicators and coverage. This article selects six categories of ESG ratings: Huazheng ESG, WIND ESG, SynTao Green Finance ESG, Susallwave ESG, Bloomberg ESG, and FTSE Russell ESG. The selection of Wind, Huazheng, SynTao Green Finance ESG, and Susallwave ESG, as the four primary rating agencies is based on their broad coverage and strong reputation in China’s ESG landscape, providing a comprehensive assessment of domestic companies’ ESG performance. The inclusion of global rating agencies—Bloomberg and FTSE Russell further supports this framework through their wider coverage of Chinese firms internationally. This dual approach helps to enhance the robustness and comparability of domestic ESG evaluations by incorporating an external, global perspective. The six ratings are subsequently assigned values and standard deviations are calculated to measure the corporate ESG rating disagreement. Huazheng ESG rating, WIND ESG rating and Susallwave ESG rating are all divided into 9 grades, from low to high with grades C, CC, CCC, B, BB, BBB, A, AA, AAA, etc. In this paper, the 9 grades of ratings C–AAA are assigned to be 1–9 in order. When the rating is AAA, ESG = 9, when the rating is AA, ESG = 8, and so on. The ESG ratings of Shangdao Ronglv are categorized into 10 grades, which from low to high include D, C−, C, C+, B−, B, B+, A−, A, and A+, respectively. Based on the above assignment methodology, the 10 grades from D− to A+ were assigned a value from 1 to 10. ESG = 1 for a D rating, ESG = 2 for a C− rating, ESG = 3 for a C rating, and so on. Bloomberg ESG ratings are scored on a scale of 0–100, with specific scores taken as 10% in this paper. FTSE Russell ESG ratings are on a 5-point scale. Therefore this paper takes the specific score as 200% for the sample data. On this basis, the ESG rating of the six categories of indicators were standardized using Z-value normalization and analyzed for standard deviation calculation, which in turn resulted in the data of ESG rating disagreement (Dis), following Christensen et al. [8] only listed companies with ratings from two or more agencies are included in the calculation; those covered by fewer than two rating agencies are treated as missing values.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

For the measurement of institutional investors’ ESG investment commitments, this paper uses four measures. (1) ESG commitment investor binary variable indicates whether the enterprise is held by UNPRI institutional investors, with a value of 1 if it is, and 0 if it is not. UNPRI institutional investors are funds established by public fund managers after signing up to the UNPRI. (2) ESG commitment institution count indicates the number of UNPRI public fund managers in which the enterprise is held. (3) ESG commitment fund count indicates the number of UNPRI funds in which the enterprise is held. (4) ESG commitment investor shareholdings indicates the percentage of shares held in the enterprise by the UNPRI organization. See Table 1 for the specific timing of public fund managers joining UNPRI.

Table 1.

Time for public funding agencies to join UNPRI.

3.2.3. Control Variables

To delve deeper into the impact of institutional investors’ ESG commitments on ESG rating divergence, this study, building upon existing literature [8], controls for a series of firm-level characteristic variables that may confound this relationship within the model. These variables include Return on Assets (RoA), Leverage (Lev), Firm Size (Size), Dual Board Membership (Dual), Shareholding Concentration (Share), Board Size (Boardsize), Cash Holdings (Cash), Tangible Asset Ratio (Tang), Management Shareholding (Mngmhldn), and Ownership Structure (Equ). Among these, ROA, LEV, Size, Cash, and Tang primarily influence rating outcomes by affecting corporate ESG performance; Dual, Share, Board Size, and MngmHldn further impact rating judgments by influencing information transparency; and ownership structure (Equ), as a key institutional factor, also exerts systemic effects on ESG practices and disclosure. Specific definitions of each variable are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Variable definitions.

3.3. Regression Model

To quantitatively examine the impact of institutional investors’ ESG investment commitments on ESG rating disagreement, the least squares regression model (OLS) in this paper is set as follows. The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method is the standard choice for linear regression due to its well-established theoretical properties and practical utility. When its core assumptions—linearity and exogeneity of regressors—are met, the Gauss-Markov theorem establishes that the OLS estimator is the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE). This means it achieves the minimum variance among all linear unbiased estimators, forming a reliable basis for precise statistical inference.

The explanatory variable Dis is the degree of corporate ESG rating disagreement. The core explanatory variable ESGI is an indicator related to institutional investors’ ESG investment commitments, including whether the company is held by institutional investors’ ESG investment commitments (ESG commitment investor binary variable), the number of ESG investment commitment fund managers (ESG commitment Institution count), the number of ESG investment commitment funds (ESG commitment fund count), and the proportion of shares held by ESG investment commitment institutional investors (ESG commitment investor shareholdings). Controls are control variables; in addition, Industry, Year, and Firm denote industry, year, and firm fixed effects, respectively. The robust standard errors are also corrected in the regression analysis using the clustering method (cluster) at the individual firm level. Cluster adjustments at the company level are primarily implemented to address potential autocorrelation issues in the error terms of panel data, thereby ensuring the reliability of statistical inferences. In research designs calculating ESG rating discrepancies among enterprises, rating divergences for the same company across different years are unlikely to be independent of each other. This is because inherent characteristics such as a company’s business complexity and information disclosure practices can lead to persistent patterns in its rating discrepancies over time.

4. Results

4.1. Data and Summary Statistics

Appendix A presents the summary statistics of our main variables in this paper. The mean of ESG rating disagreement (Dis) is 0.530, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 3.412. In terms of distribution, the mean value of firms held by ESG investment commitment institutional investors is 0.385, and the mean value of firms not held by ESG investment commitment institutional investors is 0.630. This clearly indicates that the average level of ESG rating disagreement for firms held by institutional investors committed to ESG investments is significantly lower than that for firms not held by such investors. The distributional characteristics of the remaining variables are largely consistent with those found in previous studies and will not be discussed further.

4.2. Main Regression Results

Table 3 shows the effect of institutional investors’ ESG investment commitments on ESG rating disagreement. The explanatory variables in columns (1) to (4) of Table 3 are whether they are held by ESG investment commitment institutional investors (ESG commitment investor binary variable), the number of ESG investment commitment fund institutions (ESG commitment Institution count), the number of ESG investment commitment funds (ESG commitment fund count), and the shareholding ratio of ESG investment commitment institutional investors (ESG commitment investor shareholdings), respectively. The regression results for the examined variables indicate that the ESG commitment investor binary variable, ESGI_institution, ESG commitment fund count, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings are significantly negatively correlated with Dis at the 10%, 1%, 1%, and 1% levels, respectively. In the first column, the coefficient of the ESG commitment investor binary variable is −0.014, indicating that compared to firms without ESG commitment investors, firms with ESG commitment investors exhibit a 2.6% reduction in rating divergence (obtained by dividing the coefficient by the mean of the dependent variable). In the second column, the coefficient of ESG commitment institution count is −0.092, suggesting that each additional ESG-committed fund holding in a company reduces the rating divergence by 10.5%. In the third column, the coefficient of ESG commitment fund count is −0.056, meaning each additional ESG-committed institution holding in a company reduces rating divergence by 17.3%. In the fourth column, the coefficient of ESG commitment investor shareholdings is −0.056, indicating that a 1% increase in ESG-committed fund holdings reduces the rating divergence by 27.3%. This regression result suggests that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment reduced the ESG rating disagreement of the held firms and supports H1a.

Table 3.

Main regression results.

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Propensity Score Matching Test

To address the issue of sample selection bias in the model, this paper employs the propensity score matching method. The control variables are utilized as characteristic variables, and the “1-to-1 no-replacement” nearest-neighbor matching method is applied. This approach matches ESG investment commitment institutional investors holdings samples with a group of samples that have the most similar characteristics but do not hold by ESG investment commitment institutional investors. After matching the research sample for the robustness test, the regression results are shown in column (3) of Table 4, the regression results show that: ESG commitment investor binary variable, ESGI_institution, ESG commitment fund count, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings are significantly negatively correlated with Dis at the 1% level. The findings of the study remain unchanged.

Table 4.

Propensity score matching test.

4.3.2. PSM-DID Test

To further mitigate endogeneity between institutional investors’ ESG Investment commitments and ESG rating disagreement, and taking into account the characteristics of ESG commitment institutional investors, a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model is developed. This model estimates the changes in ESG rating disagreement of firms before and after the transition from having no ESG investment commitment institutional investors to having one.

In model (2), ESGI_did denotes the ESG commitment institutional investors first holding variable. If the regression result ESGI_did coefficient is significantly negative, it indicates that ESG investment commitment institutional investors significantly reduces corporate ESG rating disagreement. To reduce the effect of noise, this paper removes samples with frequent changes in ESG investment commitment institutional investors. In order to ensure that the characteristics of the treatment group and the control group are consistent before the shock, this paper uses the control variables in this paper as the characteristic variables, and adopts the method of “1v1 no-return” nearest-neighbor matching to match the samples of ESG investment commitment institutional investors holdings with the samples of the most similar characteristics, but without ESG investment commitment Institution holdings.

The regression results are shown in Table 5 (1). In Table 5 (1), the coefficients of ESGI_did are all significantly negative, indicating that the ESG investment commitment institutional investors mitigates corporate ESG rating disagreement, which again verifies that the conclusions of this paper are robust and reliable.

Table 5.

PSM-DID test.

The effective estimation of the double-difference model relies on the fact that the trends of the “treatment group” and the “control group” are parallel before the event. Therefore, this paper generates an interaction between ESG investment commitment institutional investors and year variable, and constructs a dynamic effects model (3) to test the dynamics of the ESG rating disagreement of ESG investment commitment institutional investors holdings.

In model (3), the term ESGI*Year represents the interaction between the dummy variable indicating institutional investors’ commitment to ESG investments and the dummy variable reflecting the year before and after their initial shareholding. This includes the dummy variables ESGI_pre6, ESGI_pre5, ESGI_pre4, ESGI_pre3, ESGI_pre2, ESGI_pre1, ESGI_current, ESGI_post1, ESGI_post2, ESGI_post3, ESGI_post4, and ESGI_post5. The regression excludes ESGI_pre1 as the base period.

The regression results are presented in Table 5 (2). The coefficients for the interaction terms ESGI_pre6, ESGI_pre5, ESGI_pre4, ESGI_pre3, and ESGI_pre2 are insignificant. In contrast, during the subsequent five years, the coefficients for ESGI_post1, ESGI_post2, ESGI_post3, ESGI_post4, and ESGI_post5 are all significantly negative at the 1% level. This indicates that the disagreement in corporate ESG ratings are notably reduced following the shareholding of ESG investment commitment institutional investors in listed companies, thereby supporting the main regression result.

4.3.3. Instrumental Variables Test

To address potential endogeneity concerns, we draw on the research conducted by Nunn & Qian [25] and utilize the annual industry mean of the number of ESG commitment institutional investors multiplied by the number of Confucian temples located within 100 km of the enterprise as an instrumental variable for ESG investment commitment institution investors. The number of Confucian temples within a 100 km radius of a company serves as an exogenous geographic variable. Its spatial distribution formed during historical periods and bears no direct correlation with contemporary corporate operations or ESG performance, thereby exhibiting strong exogeneity. This variable primarily exerts influence by shaping a regional socio-cultural environment that values Confucian traditions, subtly influencing corporate values and ethical judgments. This, in turn, fosters and sustains a culture of social responsibility within the enterprise [26]. This culturally shaped disposition toward responsibility aligns with ESG investment commitment funds’ focus on long-term value and societal impact, thereby increasing their willingness to hold shares in such companies [27,28]. However, ESG rating discrepancies fundamentally stem from differences in methodology, indicator weighting, and information processing among rating agencies, representing technical outcomes. The cultural soft power embodied by Confucian temples cannot directly intervene in the standardized assessment processes of rating agencies. Therefore, theoretically, it should not exert a direct causal influence on ESG rating discrepancies.The number of industry average ESG investment commitment institutional investors is a more macro variable of a single firm, which is related to the industry average ESG investment commitment level of a single firm, but does not directly affect the ESG rating disagreement of a specific firm. This instrumental variable reflects the year-by-year diffusion of the number of ESG investment commitment institutional investors caused by exogenous geographical conditions, instrumental variable estimations give a local average treatment effect of the causal effect of ESG investment commitment funds on corporate ESG rating disagreement.

To rule out the possibility that instrumental variables influence rating divergence through channels other than ESG commitments, we conducted exclusionary tests. The results are shown in Appendix B. The results revealed that the correlation coefficients between the instrumental variables and the control variables were below 0.1, meeting the requirements for instrumental variables.

In the first stage, the instrumental variables exhibit a significant positive correlation with ESG investment commitment institutional investors. This indicates that a greater number of Confucian temples within 100 km of the enterprise contributes to a stronger corporate social responsibility (CSR) culture, thereby attracting more ESG Investment commitment institutional investors. Thus, the correlation of the instrumental variables is validated. In the first stage, Kleibergen–Paap rk LM is significant at 1% and 5% levels, rejecting the original hypothesis of insufficient identification of instrumental variables. Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic values are much larger than the Stock-Yogo weak ID test critical values at 10% significance level weak identification test critical values at the 10% significance level. In summary, the instrumental variables selected in this paper are reasonable and reliable. The results in Table 6 show that the coefficients of ESG commitment investor binary variable, ESG commitment Institution count, ESG commitment fund count, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings are significantly negative, indicating that the main conclusions of this paper still hold.

Table 6.

Instrumental variables test.

4.3.4. High-Dimensional Fixed Effects Test

To test the reliability of the findings, the paper further controls for industry-year fixed effects. The results are shown in Table 7. From Table 7, ESG commitment investor binary variable, ESG commitment Institution count, ESG commitment fund count and ESG commitment investor shareholdings are significantly at the levels of 10%, 1%, 1%, and 1% respectively negatively correlated. The conclusion of the study remains unchanged.

Table 7.

High-dimensional fixed effects test.

4.3.5. Substitution of Dependent Variables

To ensure the reliability of the findings, this study employed two alternative methods to measure ESG rating disagreement. Method one constructs an ESG rating divergence metric using the approach proposed by Avramov et al. [10]. This involves selecting pairs of rating agencies for the same firm in a given year and calculating the disagreement between the ratings assigned by these two agencies. The process is repeated for all possible pairings of rating agencies, and the corresponding disagreements are recorded. Finally, the average of these disagreements is calculated to serve as the measure of rating disagreement (Dis_r1).

To address potential concerns regarding unequal intervals between ratings, this study converted all rating or score data from the various rating agencies into standardized percentile ranks. Specifically, for each rating agency in a given year, the ESG scores of all rated companies were sorted and converted into percentile rankings. Subsequently, for each company, every possible pair of agencies that rated it in that year was identified (companies rated by only one agency were excluded from the sample). The standard deviation of the percentile rankings provided by the two agencies in each such “rater pair” was defined as the “paired rating divergence.” Finally, the average of all “paired rating divergences” across all such pairs for a given firm in a given year was computed, yielding the firm’s annual ESG rating disagreement (Dis_r2).

As shown in Table 8, the ESG commitment investor binary variable, ESG commitment Instone count, ESG commitment fund count, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings all demonstrated a significant negative relationship with firm ESG rating disagreement. These findings affirm the robustness of the study’s results.

Table 8.

Substitution of dependent variables.

Additionally, this study categorized the six types of ESG ratings into six groups based on quantiles. The ranges of the six ratings were then calculated. Subsequently, an ordered probit model was employed to examine the impact of ESG commitment on ESG rating divergence. The results, shown in Appendix F, demonstrate that the findings of this study are robust.

4.3.6. Test of Exclusion of Other Policies

To eliminate the effects of A-share inclusion in the MSCI index and stock inclusion in the CSI ESG 180, this paper constructs the dummy variable ESG_regulation for A-share inclusion in the MSCI index and the dummy variable ESG_index for stock inclusion in the CSI ESG 180. These variables are incorporated into model (1) for regression analysis. The regression results are presented in Table 9. As shown in Table 10, ESG commitment investor binary variable, ESG commitment Institution count, ESG commitment fund count, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings all demonstrate a significant negative relationship with firm ESG rating disagreement, at the 5%, 1%, 1%, and 1% levels, respectively. These findings affirm the robustness of the study’s results.

Table 9.

Test of exclusion of other policies.

Table 10.

GRI Standard test.

4.4. Mechanism Analysis

4.4.1. Information Quality Improvement Effect Test

According to the previous theoretical analysis, this paper argues that the institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment reduces the ESG rating disagreement of the holding companies through the information quality improvement effect and the” information correction” effect. The Global Reporting Initiative Sustainability Reporting Standard (GRI standard) is a standard for the preparation of ESG reports by listed companies. Each section of the GRI standards includes disclosure “Requirements” and corresponding performance indicators. Gipper et al. [29] found that ESG reports using the GRI standard are more horizontally comparable and easier to validate. Therefore, this paper examines whether institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment can lead shareholding enterprises to use GRI standard to verify the information quality improvement effect.

The results of (1)–(4) in Table 10 show that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment can significantly increase the utilization of GRI criteria in ESG reports of shareholding firms. Further, this paper introduces an interaction term between institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment and GRI criteria (ESGI#GRI) to examine whether it ultimately mitigates ESG rating disagreement. It is found that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment work better for firms using the GRI criterion, suggesting that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment reduce ESG rating disagreement through the information quality improvement effect.

4.4.2. Information Correction Effect Test

This paper tests the information correction effect by examining whether institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment attract ESG attention from the media and analysts. In this paper, we use the number of ESG news reports to measure the level of media ESG attention (ESG_new), which is mainly obtained from the Datago News ESG Quantitative Public Opinion Datasheet.

The selection of this database is based on two key factors, with data validity being the primary concern. Unlike previous studies that used text analysis to gather company-related news, a single article often mentions multiple firms for a single event. The relevance and depth of evaluation for each mentioned company can vary significantly, and many articles provide only superficial mentions rather than substantive analysis. Our database addresses this by filtering news based on publication source and content, eliminating approximately 80% of invalid data. This process ensures a significantly higher degree of news validity than the corpora used in earlier research. Second, relevance to this research. The database draws on the Hong Kong Exchange’s “Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting Guide,” Zhi Ding’s ESG rating indicators, and the ESG/social responsibility reports published by various companies to define three news themes: Environmental (E), Social (S), and Governance (G). This means the media reports selected in the database all contain information related to corporate E, S, and G factors, ensuring high relevance to the subject of this study. The media attention variable constructed in this paper is derived from the total number of corporate E, S, and G reports in this database, to which 1 is added before taking the natural logarithm.

Analyst ESG attention is primarily measured using the number of ESG analyst reports. This is performed as follows: first, this paper constructs an ESG lexicon in conjunction with Lee and Raschke’s [30] study (see Appendix A for details). Second, analyst report topics are screened by text analysis using Python 3.8. The data reported by the analysts is sourced from the CSMARK database.

In descriptive statistics, the mean of ESG_new is 1.030 and the standard deviation is 0.808, indicating that each company has 1 ESG report per year. The mean of ESG_analyst is 2.945 and the standard deviation is 7.424. it shows that each company has 2.9 analyst reports related to ESG every year. The standard deviation of analyst reports is larger than the standard deviation of news reports, indicating that the degree of analyst attention of different companies varies greatly.

The results of (1)–(4) in Table 11 show that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment can significantly increase media ESG attention. Further, this paper introduces an interaction term (ESGI#GRI) between institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment and media ESG concerns to examine whether it ultimately mitigates ESG rating disagreement. It is found that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment work better for firms with high media ESG concerns.

Table 11.

Test for attracting media ESG attention.

The results of (1)–(4) in Table 12 show that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment raises analysts’ ESG attention significantly. Further, this paper introduces an interaction term between institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment and analysts’ ESG concerns (ESGI#GRI) to examine whether it ultimately mitigates ESG rating disagreement. It is found that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment work better for firms with high analysts’ ESG concerns.

Table 12.

Test for attracting analysts’ ESG attention.

4.5. Moderating Effect Analysis

4.5.1. Corporate Governance Moderation Effect Test

The ability of institutional investors to fulfill a governance role is largely determined by the costs and capacities associated with monitoring [30,31]. For firms with stable institutional investments and greater information transparency, the monitoring process is both easier and less costly for these investors [32]. As a result, corporate governance positively moderates the relationship between institutional investors’ ESG commitments and ESG rating disagreement.

This paper uses the absolute value of manipulative accruals to measure information transparency (DA). The stability of institutional investors (Stable) is determined through a two-step process. In the first step, we assess institutional investor stability over time by calculating the ratio of the percentage of institutional investor holdings in firm i during year t to the standard deviation of those holdings over the previous three years. A higher value indicates greater stability of institutional investors in the time dimension. In the second step, we evaluate institutional investor heterogeneity from an industry perspective. If the ratio of a firm’s institutional investor shareholding to the standard deviation of its institutional investor shareholding over the past three years is greater than or equal to the annual industry median, the firm is classified as having stable institutional investors. In this case, the variable Stable is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0.

In Table 13, ESG commitment investor binary variable # DA, ESG commitment Institution count # DA, ESG commitment fund count # DA, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings # DA are all significantly positive, and ESG commitment investor binary variable # Stable, ESG commitment Institution count # Stable, ESG commitment fund count # Stable, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings # Stable are all significantly negative, indicating that institutional investors are more effective when the level of corporate governance is high.

Table 13.

Corporate governance moderation effect test.

To increase the robustness of the results, this paper also uses measures of board independence and the number of ESG members, and the results are shown in the Appendix D. From the results of the Appendix E, the conclusions of this paper are robust.

4.5.2. Industry ESG Sensitivity Moderation Effect Test

ESG-sensitive industries pose significant threats to the ecological environment and public welfare due to their production activities being directly linked to high carbon emissions, environmental pollution, and excessive resource consumption [33,34]. Consequently, they become the primary focus and subject to rigorous screening by ESG-committed funds. In contrast, non-ESG-sensitive sectors—such as certain technology and consumer services fields—exhibit inherently milder negative impacts, resulting in relatively lower oversight pressure. Consequently, ESG industry sensitivity positively moderates the relationship between ESG institutional investor commitments and ESG rating disagreements. Highly polluting industries often attract greater scrutiny and exhibit stronger ESG sensitivity. Therefore, this paper references the ”Catalogue of Environmental Protection Inspection Industry Classification Management for Listed Companies” to classify B06, B07, B08, B09, C17, C19, C22, C25, C26, C28, C29, C30, C31, C32, and D44 as heavily polluting industries.

In Table 14, ESG commitment investor binary variable # DA, ESG commitment Institution count # DA, ESG commitment fund count # DA, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings # DA are all significantly positive, and ESG commitment investor binary variable # Stable, ESG commitment Institution count # Stable, ESG commitment fund count # Stable, and ESG commitment investor shareholdings # Stable are all significantly negative. our findings reveal heavy pollution industry positively moderates the relationship between institutional investors’ ESG commitments and ESG rating disagreement.

Table 14.

Heavy pollution industry moderation effect test.

4.6. Further Discussion

As a developing nation, China’s unique relational social context renders “soft information” crucial in social interactions. Within this environment, both domestic and international ESG rating agencies face significant transnational information asymmetry [35]. International rating agencies typically rely on globally uniform, standardized assessment frameworks, which often struggle to accurately capture and measure “soft” ESG performance rooted in local culture, informal institutions, and social relationships. For instance, a Chinese company’s actual performance in community relations, labor practices, or government collaboration is often embedded within localized business environments, making it difficult for analysts overseas to fully decipher [36,37].

In contrast, local institutions leverage their geographical and cultural proximity to more effectively gather and interpret this “soft information” through multiple channels after funds make ESG investment commitments [1]. They can not only verify publicly disclosed ESG data more swiftly but also gain deeper insights into the operational quality of the underlying social capital and relationship networks. Therefore, when local institutions invest based on their informational advantage, their actions themselves send a clearer and more credible signal of ESG quality to the market. This effectively mitigates rating discrepancies arising from the disconnect between international rating standards and local practices, making the ESG commitments of local institutional investors particularly significant in bridging domestic rating gaps.

ESG rating agencies are categorized into domestic and foreign based on their geographical attributes. The standard deviation of Bloomberg and FTSE Russell rating results is used to indicate foreign ESG rating disagreement (Dis_for). The standard deviation of the results of the FIN-ESG ratings of wind, CSI, Merchant R&G and Allied Wave is calculated to indicate the domestic ESG rating disagreement (Dis_dom).

In Table 15 are the regression results of institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment and domestic and foreign ESG rating disagreement. Positive and significant results appear only in the first four columns, indicating that institutional investors’ ESG investment commitment mitigate domestic ESG rating disagreement, but this effect is not significant among foreign ESG rating agencies.

Table 15.

ESG rating agency characteristics heterogeneity test.

5. Conclusions

This study found that after institutional investors sign the UNPRI principles, they assume a role far beyond that of passive investors, transforming into proactive shapers of the information ecosystem. They assist companies in improving their ESG information disclosure while also helping attract greater follow-up from analysts and media, thereby playing an information-correcting role and compressing the scope for rating divergence. Further research also revealed that the mitigating effect of institutional investors’ ESG commitments on rating divergence is more pronounced in companies with superior corporate governance, in industries with high ESG sensitivity, and when assessed by domestic rating agencies. The value of this study lies in its compelling demonstration that market participants themselves can become proactive co-creators of credibility. Rather than being passive recipients of rating outcomes, they actively engage in shaping the informational foundation upon which ratings rely through guiding disclosures, attracting scrutiny, and proactive intervention.

5.1. Policy Recommendation

The following recommendations are made based on the findings of this paper:

First, regulators should encourage institutional investors to actively engage with international ESG organizations and learn from leading global practices in ESG investment. The research presented in this paper finds that institutional investors’ participation in reputable international ESG organizations, such as the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), can help reduce discrepancies in ESG ratings among the firms they invest in. To promote this, regulators can foster deeper collaboration with international ESG organizations like the PRI, increase awareness of successful case studies, and encourage more institutional investors to participate. This approach will enhance the efficiency of corporate ESG development and promote better sustainability practices across the industry.

Second, regulators should promote cooperation among cross-border ESG rating agencies. The research in this paper indicates that fund ESG commitments play a crucial role in mitigating rating discrepancies among domestic ESG rating agencies. Therefore, regulators should actively facilitate collaboration and communication between domestic and foreign rating agencies to minimize the divergence in domestic ESG ratings and enhance rating accuracy. This cooperation will help establish more consistent and reliable ESG assessments, benefiting the investment community and promoting transparency in ESG reporting.

Third, to effectively respond to regulatory and investor ESG expectations and fundamentally reduce rating discrepancies, companies should proactively learn and adopt international mainstream ESG standards such as GRI and SASB to enhance the transparency and comparability of their disclosures. Concurrently, companies must focus on building internal ESG management capabilities, deeply integrating ESG into corporate strategy and risk management, and establishing regular communication channels with institutional investors to actively incorporate their feedback. Furthermore, actively participating in industry ESG initiatives to share best practices and introducing third-party verification to enhance data credibility are also critical measures for companies to improve ESG performance, lower financing costs, and achieve long-term value.

5.2. Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations that offer productive pathways for future scholarship.

The first limitation is the single-country context (China) and its regulatory specificities. The findings of this study showed significant differences in economies with different regulatory frameworks, market maturity, and cultural traditions. For example, the “incremental marginal effect” of institutional investors may be less pronounced in an already heavily regulated environment than in China.

The second limitation is the potential self-selection bias due to the use of UNPRI participation. Although our instrumental variable and PSM-DID design help to alleviate endogeneity concerns, the identification rests on the exclusion restriction that our IV affects rating disagreement only through its impact on ESG investor holdings. While geographically determined social norms are plausibly exogenous, unobserved firm-level factors correlated with both cultural endowment and ESG performance might persist.

Finally, there was an absence of cross-rating agency reliability tests. Our current study did not consider ESG rating reliability so a weakening ESG rating disagreement may not mean that the ratings are more accurate.

5.3. Future Research

Building on our findings, future research could delve deeper into the “black box” of investor engagement. Our study used the outcome of reduced disagreement, but the specific mechanisms of dialog—such as the topics, frequency, and tone of private engagements between UNPRI signatories and firm management—remain unstudied. Survey-based or interview-based methodologies could illuminate these micro-processes. Furthermore, as mandatory ESG disclosure regulations gain global traction, a critical future inquiry would be to examine how such top–down regulatory mandates interact with, and potentially crowd out or reinforce, the bottom–up monitoring role of institutional investors that we identified. When data becomes available, future research can further examine whether the discrepancies stem from coverage or from the scoring process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; Software, Y.S.; Validation, Y.S.; Investigation, Y.S.; Supervision, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Comments from the editor and the anonymous referees are gratefully acknowledged. However, the usual disclaimer applies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Summary Statistics of Main Variables

Table A1.

Summary statistics of main variables.

Table A1.

Summary statistics of main variables.

| Variable | Sample Size (Sample Size 27,003) | Companies Held by ESG Investment Institutional Investors (Sample Size 16,033) | Companies Not Held by ESG Investment Commitment Institutional Investors (Sample Size 10,970) | All A-Share Listed Companies (Sample Size 31,953) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std | Min | p50 | Max | Mean | Std | Mean | Std | Mean | Std | |

| Dis | 27,003 | 0.530 | 0.469 | 0 | 0.489 | 3.412 | 0.385 | 0.502 | 0.630 | 0.417 | ||

| Share | 27,003 | 0.809 | 0.622 | 0.0373 | 0.655 | 2.846 | 0.787 | 0.621 | 0.824 | 0.621 | 0.816 | 0.640 |

| Dual | 27,003 | 0.319 | 0.466 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.297 | 0.457 | 0.334 | 0.472 | 0.314 | 0.464 |

| Mngmhldn | 27,003 | 14.90 | 19.69 | 0 | 2.460 | 68.12 | 14.39 | 19.95 | 15.24 | 19.51 | 14.59 | 19.82 |

| Boardsize | 27,003 | 8.350 | 1.592 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 8.345 | 1.575 | 8.353 | 1.603 | 8.414 | 1.754 |

| Roa | 27,003 | 0.0325 | 0.0754 | −0.354 | 0.0371 | 0.205 | 0.0223 | 0.0774 | 0.0395 | 0.0732 | 0.0373 | 0.133 |

| Equ | 27,003 | 0.286 | 0.452 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.295 | 0.456 | 0.280 | 0.449 | 0.329 | 0.470 |

| Tang | 27,003 | 0.923 | 0.0920 | 0.520 | 0.955 | 1.000 | 0.918 | 0.0972 | 0.926 | 0.0880 | 0.848 | 0.249 |

| Cash | 27,003 | 2.548 | 2.465 | 0.312 | 1.741 | 15.56 | 2.478 | 2.425 | 2.596 | 2.492 | 2.305 | 2.458 |

| Size | 27,003 | 22.24 | 1.288 | 19.87 | 22.05 | 26.36 | 21.88 | 1.173 | 22.49 | 1.305 | 22.23 | 1.569 |

| Lev | 27,003 | 0.416 | 0.207 | 0.0577 | 0.404 | 0.946 | 0.422 | 0.217 | 0.412 | 0.200 | 0.439 | 1.056 |

Appendix B. Test of IV Limitation

Table A2.

Test of IV limitation.

Table A2.

Test of IV limitation.

| IV | Size | Roa | Lev | Cash | Share | Dual | Boardsive | Mngmhldn | Equ | Tang | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | 1 | ||||||||||

| Size | 0.0402 | 1 | |||||||||

| Roa | −0.0163 | 0.0271 | 1 | ||||||||

| Lev | −0.0306 | 0.4769 | −0.3694 | 1 | |||||||

| Cash | 0.0799 | −0.3465 | 0.2193 | −0.6589 | 1 | ||||||

| Share | 0.0621 | −0.1035 | −0.025 | −0.0889 | 0.0817 | 1 | |||||

| Dual | 0.0836 | −0.1834 | 0.0317 | −0.1309 | 0.1253 | 0.0527 | 1 | ||||

| Boardsize | −0.0796 | 0.2881 | 0.016 | 0.1345 | −0.1244 | 0.023 | −0.184 | 1 | |||

| Mngmhldn | 0.0652 | −0.3464 | 0.165 | −0.3 | 0.2523 | 0.1758 | 0.239 | −0.2029 | 1 | ||

| Equ | −0.0603 | 0.355 | −0.054 | 0.2479 | −0.1788 | −0.2312 | −0.3052 | 0.2772 | −0.4462 | 1 | |

| Tang | 0.0901 | −0.0174 | 0.065 | 0.0408 | 0.1337 | −0.1053 | −0.0094 | −0.0016 | −0.0002 | 0.0774 | 1 |

Appendix C. Greenwashing Effect Test

To validate the greenwashing mechanism, we employed greenwashing indicators for verification. This paper references Zhang et al. [38] research to measure greenwashing. The specific calculation formula is shown in (1).

where ESG Disclosure is the firm’s ESG disclosure as measured by Bloomberg ESG Disclosure Score. ESG Performance is measured by CSI ESG Rating. ESG_Disclosure is the mean of ESG disclosure. σESG_Disclosure is the standard deviation of firms. ESG_Action is the mean of ESG disclosure. σESG_Action is the standard deviation of the firm. By calculating the difference between the mean-variance normalized ESG disclosures and the actual ESG data, we obtain an indicator of greenwashing in ESG disclosures. The more significant the difference, the higher the degree of green washing.

The Bloomberg ESG Disclosure Score was used to measure a company’s ESG disclosure in this study. The Bloomberg ESG Disclosure Score reflects the amount of ESG data disclosed by the company to the public but does not assess its ESG performance. All ESG information disclosed by the selected companies is counted in the score, regardless of whether it is favorable. Over 900 key disclosure metrics are divided into separate disclosure scores, which are then combined into a total Bloomberg ESG disclosure score for each company. Scores start at 0.1 for companies that disclose minimal ESG data and go up to 100 for companies that disclose more ESG information. A higher Bloomberg ESG Disclosure Score indicates that the company discloses more non-financial information.

This study selected the CSI ESG rating to measure enterprises’ actual ESG performance. The CSI ESG index system refers to the mainstream ESG evaluation framework and considers the reality of China’s capital market and the characteristics of various listed companies. The industry-weighted average method is adopted for ESG evaluation, which is updated quarterly and includes all listed companies. Ratings are categorized into nine grades from C to AAA. This paper assigns values from 9 to 1, with larger values indicating better ESG performance.

To ensure robustness of the results, we also constructed the Oral and Actual variables following the approach outlined by Hu et al. [39]. The Oral variable indicates whether the number of keywords exceeds the industry median, while the Actual variable indicates whether environmental penalties were incurred during the year. These variables were then multiplied to yield the final results.

Based on the results in Table C, the coefficients for all variables are negative and not statistically significant, indicating that no greenwashing mechanism exists. Hypothesis H1b is rejected.

Table A3.

Test for greenwashing.

Table A3.

Test for greenwashing.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | GW | GW | GW | GW | GW_r | GW_r | GW_r | GW_r |

| ESG commitment investor binary variable | 0.001 (0.20) | −0.032 (−0.69) | ||||||

| ESG commitment Institution count | −0.005 (−1.37) | −0.016 (−0.46) | ||||||

| ESG commitment fund count | −0.003 (−1.36) | 0.009 (0.46) | ||||||

| ESG commitment investor shareholdings | 0.011 (0.91) | 0.063 (0.65) | ||||||

| Size | 0.014 ** | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.014 ** | −0.040 | −0.035 | −0.054 | −0.048 |

| (2.36) | (2.74) | (2.74) | (2.28) | (−0.65) | (−0.54) | (−0.80) | (−0.76) | |

| Roa | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.317 | 0.319 | 0.314 | 0.308 |

| (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.06) | (1.06) | (1.07) | (1.06) | (1.03) | |

| Lev | −0.016 | −0.021 | −0.022 | −0.016 | 0.187 | 0.178 | 0.206 | 0.196 |

| (−0.74) | (−0.95) | (−0.96) | (−0.72) | (0.73) | (0.70) | (0.81) | (0.77) | |

| Cash | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.030 * | 0.030 * | 0.030 * | 0.030 * |

| (−1.00) | (−1.05) | (−1.04) | (−1.00) | (1.84) | (1.82) | (1.87) | (1.87) | |

| Share | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.003 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.007 |

| (−0.40) | (−0.42) | (−0.41) | (−0.41) | (0.09) | (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.10) | |

| Dual | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.013 |

| (0.73) | (0.75) | (0.75) | (0.74) | (−0.21) | (−0.21) | (−0.21) | (−0.21) | |

| Boardsize | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| (−0.75) | (−0.75) | (−0.75) | (−0.75) | (0.37) | (0.37) | (0.37) | (0.36) | |

| Mngmhldn | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** | −0.001 * | −0.001** | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.005 |

| (−2.06) | (−1.96) | (−1.95) | (−2.07) | (−1.23) | (−1.24) | (−1.25) | (−1.23) | |

| Equ | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.092 | −0.093 | −0.090 | −0.090 |

| (−0.71) | (−0.73) | (−0.72) | (−0.69) | (−0.57) | (−0.58) | (−0.56) | (−0.56) | |

| Tang | −0.034 | −0.029 | −0.028 | −0.034 | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.022 |

| (−0.90) | (−0.77) | (−0.75) | (−0.92) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.05) | |

| Constant | −0.190 | −0.257 * | −0.261 * | −0.182 | 0.356 | 0.243 | 0.625 | 0.520 |

| (−1.30) | (−1.69) | (−1.70) | (−1.23) | (0.24) | (0.16) | (0.40) | (0.35) | |

| Observations | 21,814 | 21,814 | 21,814 | 21,814 | 6194 | 6194 | 6194 | 6194 |

| R-squared | 0.341 | 0.341 | 0.341 | 0.341 | 0.607 | 0.607 | 0.607 | 0.607 |

| FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Notes: Yes means the control variable and fixed effect is controlled for. The t-statistics are in parentheses. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01. FE includes industry fixed effects, firm fixed effects, and year fixed effects, as defined above.

Appendix D. ESG Dictionary

Table A4.

ESG dictionary with E, S, and G word/word roots.

Table A4.

ESG dictionary with E, S, and G word/word roots.

| Environment (E) | Social (S) | Governance (G) |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Protection | Companionship | Organizations |

| New Energy | Advocacy | Approval |

| Environmental Protection | Care | Assurance |

| Pollution | Career | Audit |

| Energy Consumption | Caring | Board of Directors |

| Emission Reduction | Charity | Committees |

| Emission | Community | Communication |

| Ecology | Discrimination | Compliance |

| Green | Diversity | Controls |

| Low Carbon | Education | Corruption |

| Air | Employment | Administration |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand | Empowerment | Governance |

| Sulfur Dioxide | Participation | Code |

| Carbon Dioxide | Equality | Leadership |

| PM10 | Equity | Laws |

| PM2.5 | Gender | Surveillance |

| Dust removal | Humanity | Operation |

| Decontamination | Inclusion | Surveillance |

| Recycling | Inequality | Policy |

| Energy saving | Labor | Practice |

| Desulfurization | Loyalty | Privatization |

| Denitrification | Minority | Secrecy |

| Eliminate backwardness | Poverty | Procedure |

| Social | Process | |

| Stakeholders | Regulation | |

| Team | Review | |

| Training | Risk | |

| Trust | Shareholders | |

| Understanding | Managers | |

| Evaluation | Managers | |

| Volunteer | Strategy | |

| Salary | Structure | |

| Welfare | Oversight | |

| Women | Transparency | |

| Jobs | Vision | |

| Mission | ||

| Independent Directors | ||

| Directors |

Appendix E. Corporate Governance Level Heterogeneity Support Test

Table A5.

Corporate governance level heterogeneity support test.

Table A5.

Corporate governance level heterogeneity support test.

| Variables | ESGcommittee | Inddirector | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Dis | Dis | Dis | Dis | Dis | Dis | Dis | Dis | |

| ESG commitment investor binary variable#ESGcommittee | −0.095 ** (−2.04) | |||||||

| ESG commitment Institution count#ESGcommittee | −0.038 ** (−2.58) | |||||||

| ESG commitment fund count#ESGcommittee | −0.017 *** (−3.35) | |||||||

| ESG commitment investor shareholdings#ESGcommittee | 0.007 (0.13) | |||||||

| ESG commitment investor binary variable#inddirector | −0.104 *** (−7.48) | |||||||

| ESG commitment Institution count#inddirector | −0.060 *** (−8.88) | |||||||

| ESG commitment fund count#inddirector | −0.030 *** (−8.57) | |||||||

| ESG commitment investor shareholdings#inddirector | −0.113 * (−1.90) | |||||||

| ESGcommittee | 0.080 | 0.094 ** | 0.084 *** | −0.010 | ||||

| (1.64) | (2.13) | (2.60) | (−0.50) | |||||

| ESG commitment investor binary variable | −0.014 * (−1.67) | 0.307 *** (7.05) | ||||||

| ESG commitment Institution count | −0.091 *** | 0.099 *** | ||||||

| (−14.54) | (4.50) | |||||||

| ESG commitment fund count | −0.056 *** | 0.040 *** | ||||||

| (−16.79) | (3.47) | |||||||

| ESG commitment investor shareholdings | −0.144 *** (−5.43) | 0.225 (1.20) | ||||||

| ESG commitment investor shareholdings#ESGcommittee | 0.007 (0.13) | |||||||

| inddirector | 0.060 *** (3.66) | 0.066 *** (4.22) | 0.063 *** (4.04) | 0.006 (0.39) | ||||

| Constant | 1.067 *** | −0.060 | −0.336 | 0.910 *** | 0.928 *** | −0.124 | −0.377 | 0.925 *** |

| (4.56) | (−0.25) | (−1.40) | (3.91) | (3.95) | (−0.52) | (−1.58) | (3.97) | |

| Observations | 26,615 | 26,615 | 26,615 | 26,615 | 26,615 | 26,615 | 26,615 | 26,615 |

| R-squared | 0.446 | 0.454 | 0.457 | 0.447 | 0.449 | 0.457 | 0.460 | 0.447 |

| FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Notes: Yes means the control variable and fixed effect is controlled for. The t-statistics are in parentheses. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, and *** p < 0.01. FE includes industry fixed effects, firm fixed effects, and year fixed effects, as defined above.

Appendix F. Substitution of Dependent Variables Support Test

Table A6.

Substitution of dependent variables support test.

Table A6.

Substitution of dependent variables support test.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Dis_r3 | Dis_r3 | Dis_r3 | Dis_r3 |

| ESG commitment investor binary variable | −0.194 *** (−9.64) | |||

| ESG commitment Institution count | −0.170 *** (−15.07) | |||

| ESG commitment fund count | −0.081 *** (−14.81) | |||

| ESG commitment investor shareholdings | −0.128 ** (−2.23) | |||

| Size | −0.312 *** | −0.275 *** | −0.274*** | −0.330 *** |

| (−42.02) | (−34.05) | (−33.76) | (−45.78) | |

| Roa | −1.992 *** | −1.773 *** | −1.780 *** | −2.072 *** |

| (−19.09) | (−16.76) | (−16.84) | (−19.80) | |

| Lev | 1.127 *** | 1.069 *** | 1.071 *** | 1.170 *** |

| (21.02) | (19.86) | (19.90) | (21.91) | |

| Cash | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| (1.11) | (1.44) | (1.59) | (1.25) | |

| Share | −0.009 | −0.005 | −0.003 | −0.008 |

| (−0.83) | (−0.43) | (−0.27) | (−0.71) | |

| Dual | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| (0.50) | (0.95) | (0.98) | (0.33) | |

| Boardsize | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.000 |

| (−0.06) | (0.14) | (0.11) | (−0.08) | |

| Mngmhldn | −0.008 *** | −0.008 *** | −0.008 *** | −0.008 *** |

| (−20.11) | (−19.66) | (−19.81) | (−20.46) | |

| Equ | −0.204 *** | −0.215 *** | −0.215 *** | −0.202 *** |

| (−11.12) | (−11.69) | (−11.69) | (−11.01) | |

| Tang | −1.097 *** | −1.060 *** | −1.051 *** | −1.089 *** |

| (−13.90) | (−13.43) | (−13.32) | (−13.81) | |

| Observations | 27,003 | 27,003 | 27,003 | 27,003 |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Indu FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Notes: Yes means the control variable and fixed effect is controlled for. The t-statistics are in parentheses. ** p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.01. FE includes industry fixed effects, firm fixed effects, and year fixed effects, as defined above.

References

- Chen, J.Z.; Li, Z.; Mao, T.; Yoon, A. Global versus local ESG ratings: Evidence from China. Account. Rev. 2025, 100, 161–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Koelbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate confusion: The disagreement of ESG ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, G.R.; Glossner, S.; Krueger, P.; Matos, P.; Steffen, T. Do responsible investors invest responsibly? Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1389–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qi, B.; Li, Y.; Hossain, M.I.; Tian, H. Does institutional commitment affect ESG performance of firms? Evidence from the United Nations principles for responsible investment. Energy Econ. 2024, 130, 107302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Lins, K.V.; Roth, L.; Wagner, H.F. Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yoon, A. Analyzing Active fund managers’ commitment to ESG: Evidence from the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsultan, A.; Hussainey, K. Does nomination committee diversity influence the relationship between audit committee diversity and ESG disclosure? Evidence from the UK. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why is corporate virtue in the eye of The beholder? The Case of ESG ratings. Account. Rev. 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, M.; Mastrorocco, I.; Garegnani, G.M. The influence of market and institutional factors on ESG rating disagreement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3916–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, D.; Cheng, S.; Lioui, A.; Tarelli, A. Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 145, 642–664. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Lou, J.; He, B. Greening corporate environmental, social, and governance performance: The impact of China’s carbon emissions trading pilot policy on listed companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Z.; He, B. Merging Economic Aspirations with Sustainability: ESG and the Evolution of the Corporate Development Paradigm in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z. Dynamic incentive contracts for ESG investing. J. Corp. Financ. 2024, 87, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Du, K. From awareness to action: The role of ESG committees in driving corporate ambidextrous green innovation. Energy Econ. 2025, 150, 108835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Krüger, P.; van Dijk, M. Drawing up the bill: Are ESG ratings related to stock returns around the world? J. Corp. Finance 2025, 93, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippas, D.; Tziogkidis, P.; Sfakianakis, M. The fine line between ESG commitment and bank performance. Energy Econ. 2025, 151, 108978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T. The importance of climate risks for institutional investors. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1067–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Guan, S.; He, B. The Impact of Trade Openness on Carbon Emissions: Empirical Evidence from Emerging Countries. Energies 2025, 18, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lan, K. Does Green Finance Policy Contribute to ESG Disclosure of Listed Companies? A Quasi-Natural Experiment from China. SAGE Open 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Tang, Q. The real effects of ESG reporting and GRI standards on carbon mitigation: International evidence. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 2985–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Ferreira, M.R. Where Is Human Resource Management in Sustainability Reporting? ESG and GRI Perspectives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, M.D.; Wang, X.; Wei, S.; Zhang, J. Does voluntary ESG reporting resolve disagreement among ESG rating agencies? Eur. Account. Rev. 2024, 33, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, R.; Rao, P.; Kumar, S.; Paltrinieri, A. ESG investing & firm performance: Retrospections of past & reflections of future. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 1096–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, S.; Mazzù, S.; Naciti, V.; Paltrinieri, A. A PRISMA systematic review of greenwashing in the banking industry: A call for action. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 69, 102262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, N.; Qian, N. US food aid and civil conflict. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1630–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Xie, Y.; Lai, S.; Zeng, Q. Confucian culture and accounting conservatism: Evidence from China. China J. Account. Stud. 2022, 10, 549–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Yu, H. Confucian culture and corporate innovation. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.M.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z. Confucian culture and corporate environmental management: The role of innovation, financing constraints and managerial myopia. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 73, 102585. [Google Scholar]

- Gipper, B.; Ross, S.; Shi, S.X. ESG assurance in the United States. Rev. Account. Stud. 2024, 30, 1753–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, D.; Yu, Q.; Liu, X. Peer ESG controversies and enterprise earnings management. Energy Econ. 2025, 149, 108736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, J.; Zhang, L. ESG ratings and corporate clean production from the perspective of evolutionary game theory: Evidence from A-share listed companies. Energy Econ. 2025, 152, 108989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Pang, Y. ESG Disagreement and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. Asia-Pac. Financ. Mark. 2025, 32, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L. Stakeholder legitimacy in firm greening and financial performance: What about greenwashing temptations? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Yan, X. Environmental management system certification and corporate ESG greenwashing. Energy Econ. 2025, 149, 108800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Li, R. ESG ratings and ESG mutual fund management compensation. Energy Econ. 2025, 147, 108511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coval, J.D.; Moskowitz, T.J. Home bias at home: Local equity preference in domestic portfolios. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 2045–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Ma, C. Can the Inclusiveness of Foreign Capital Improve Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Subsidy expiration and greenwashing decision: Is there a role of bankruptcy risk? Energy Econ. 2023, 118, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hua, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C. The green fog: Environmental rating disagreement and corporate greenwashing. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).