Modeling an Energy Router with an Energy Storage Device for Connecting Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Sustainable Development of Power Supply Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

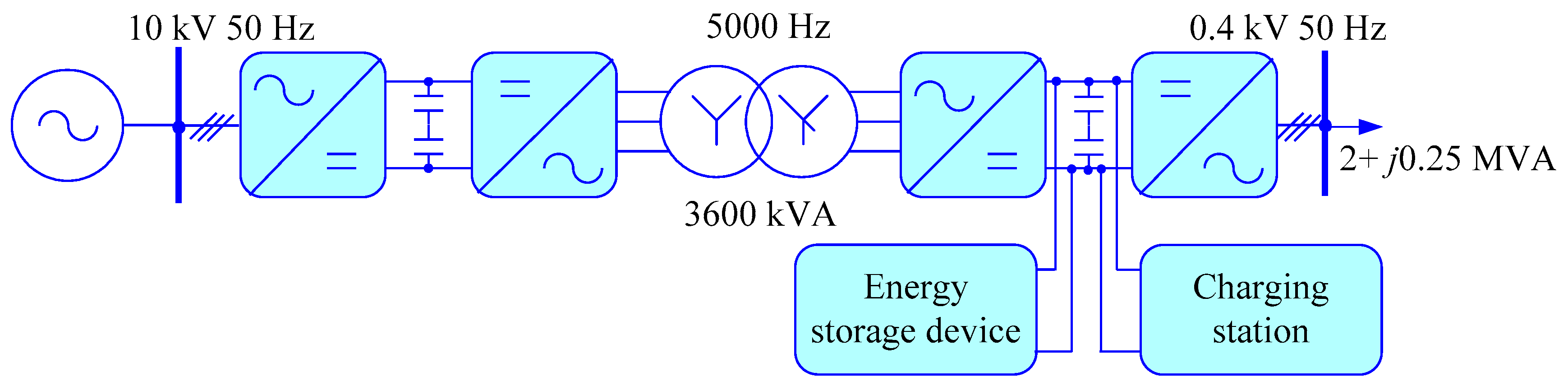

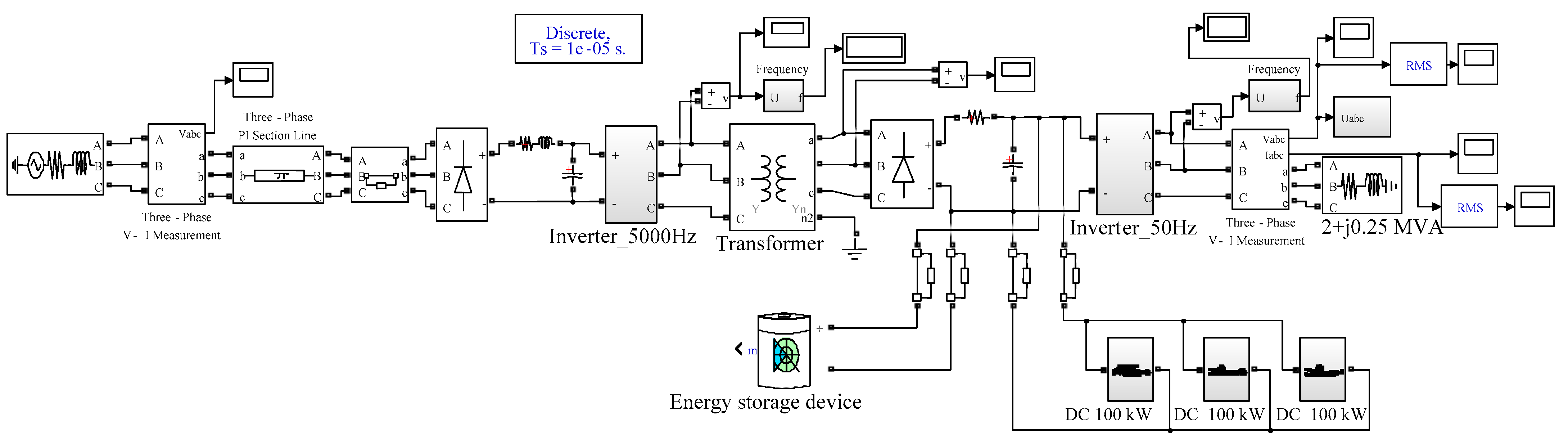

2. Problem Statement and Proposed Solution

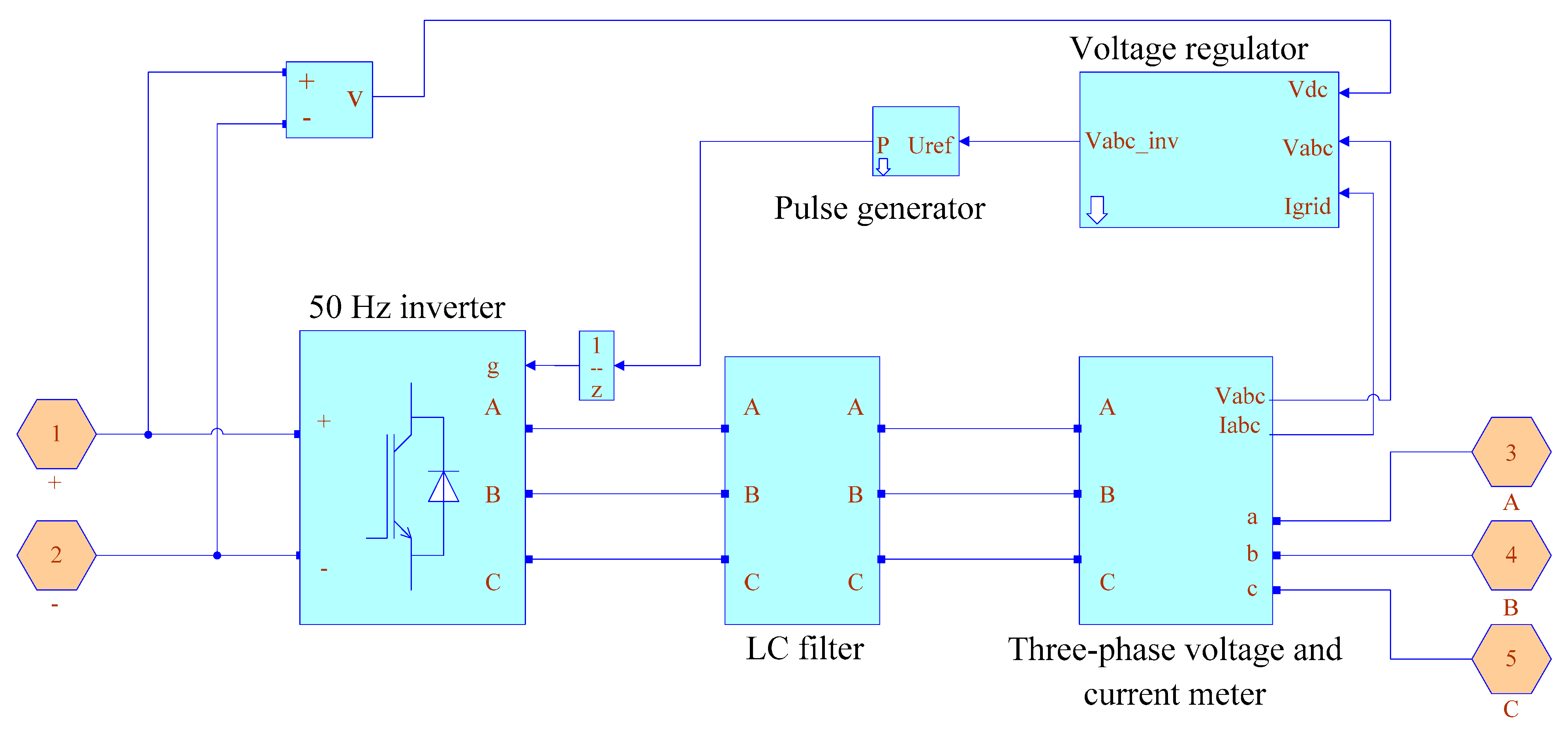

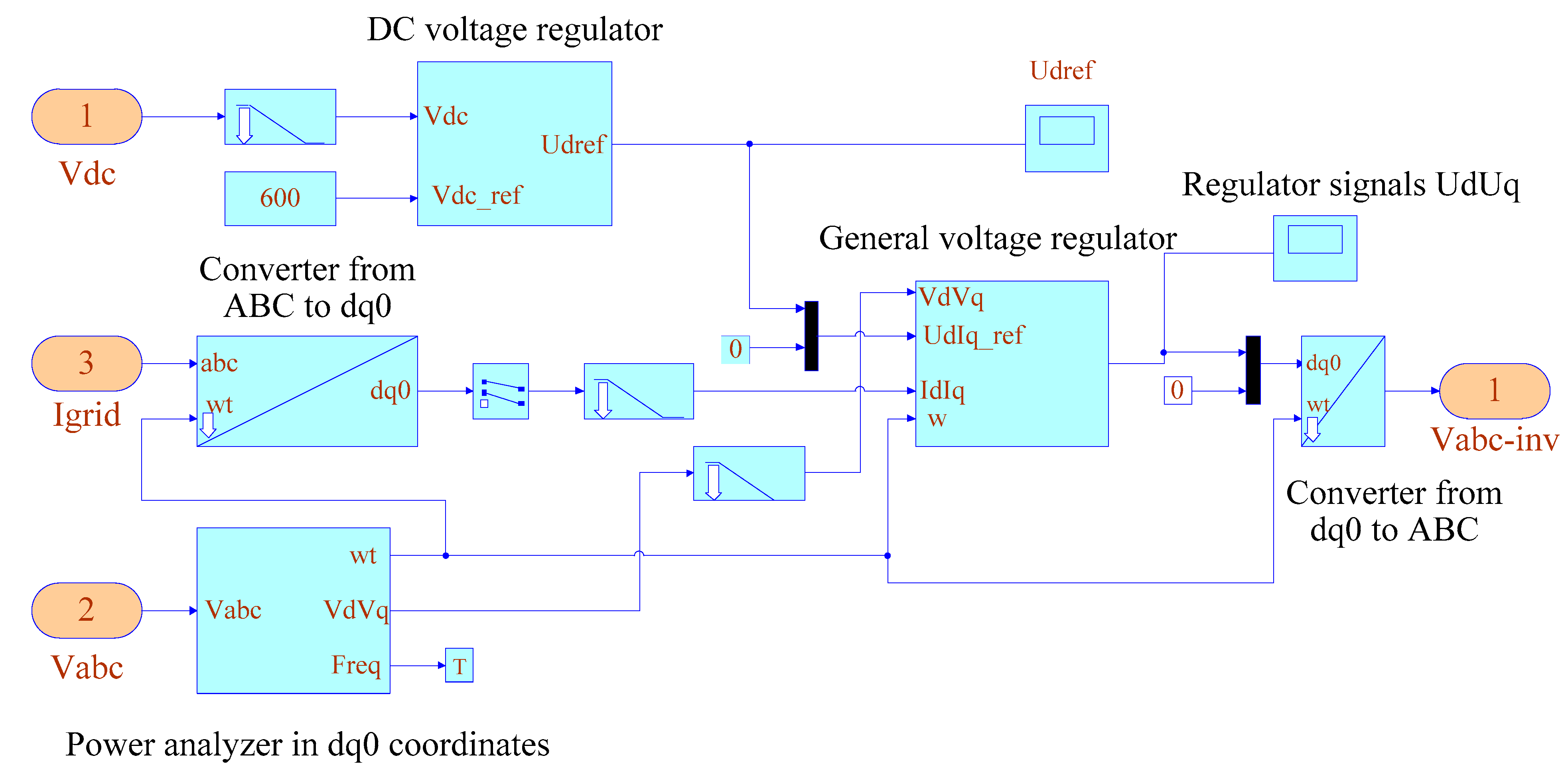

3. Materials and Methods

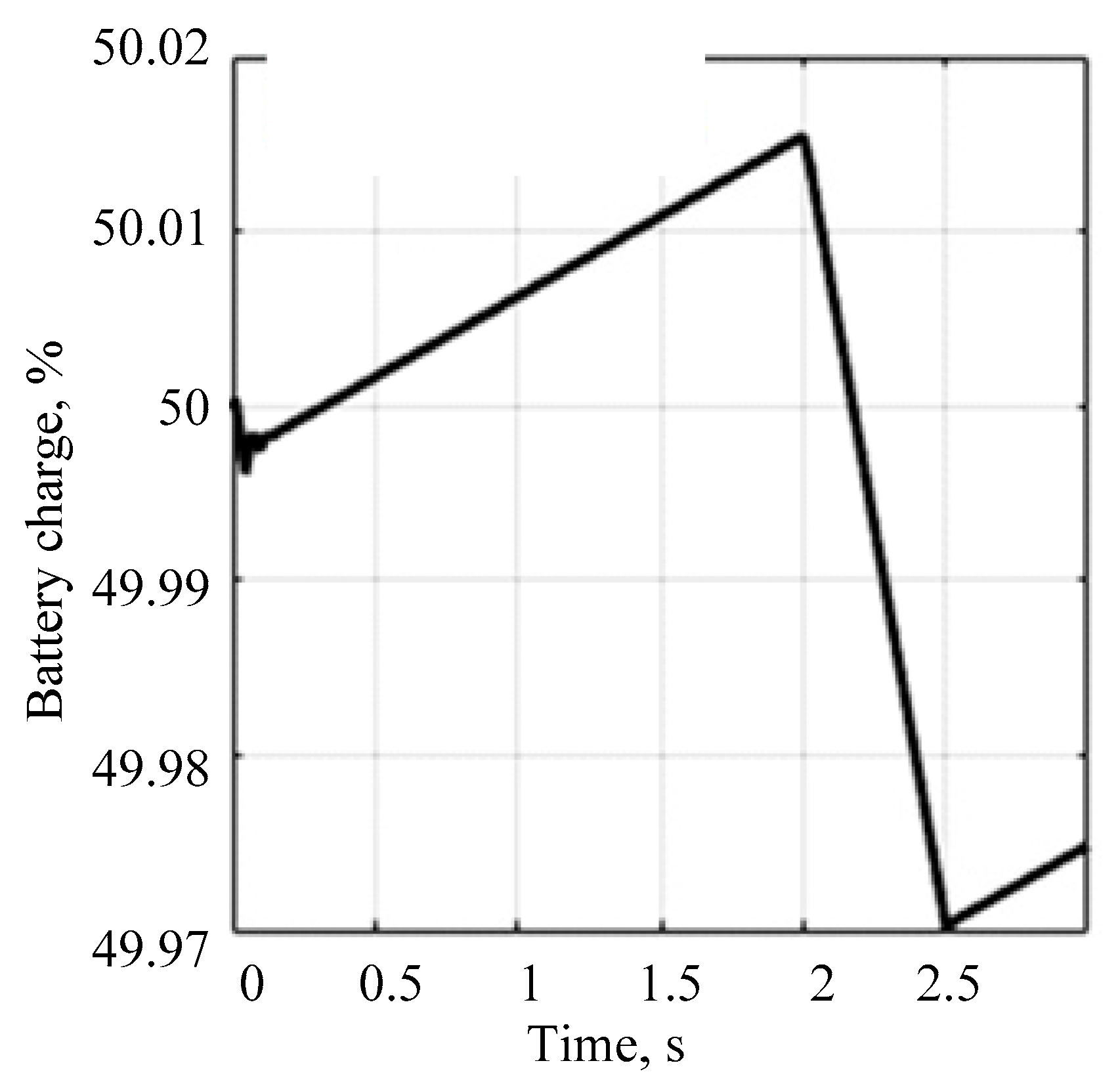

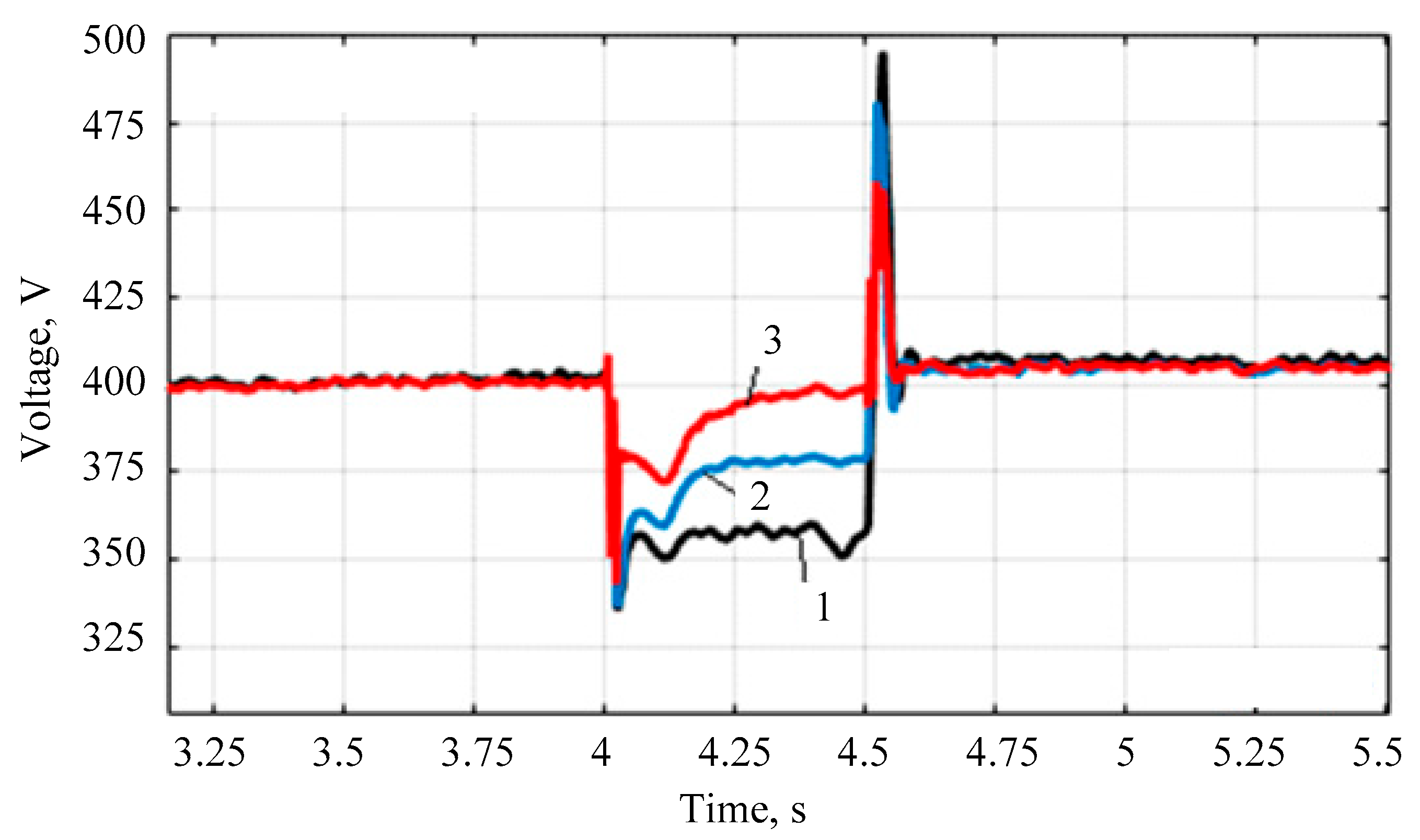

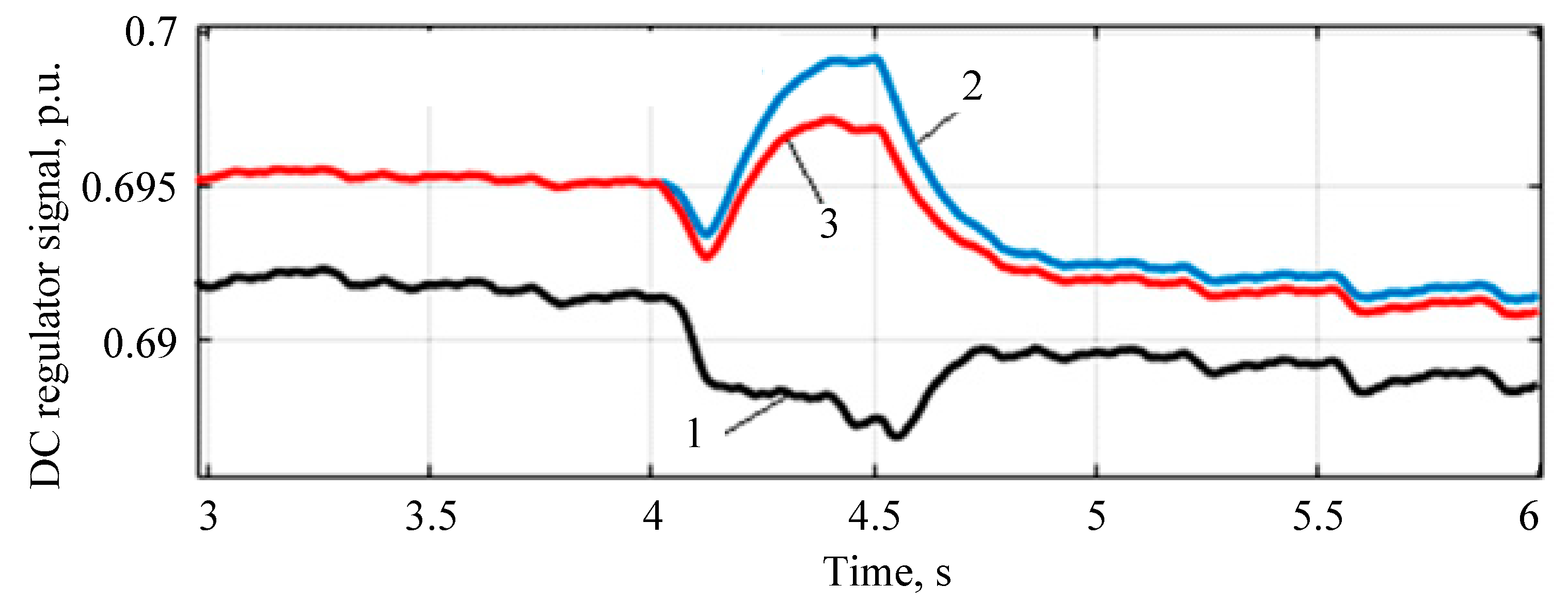

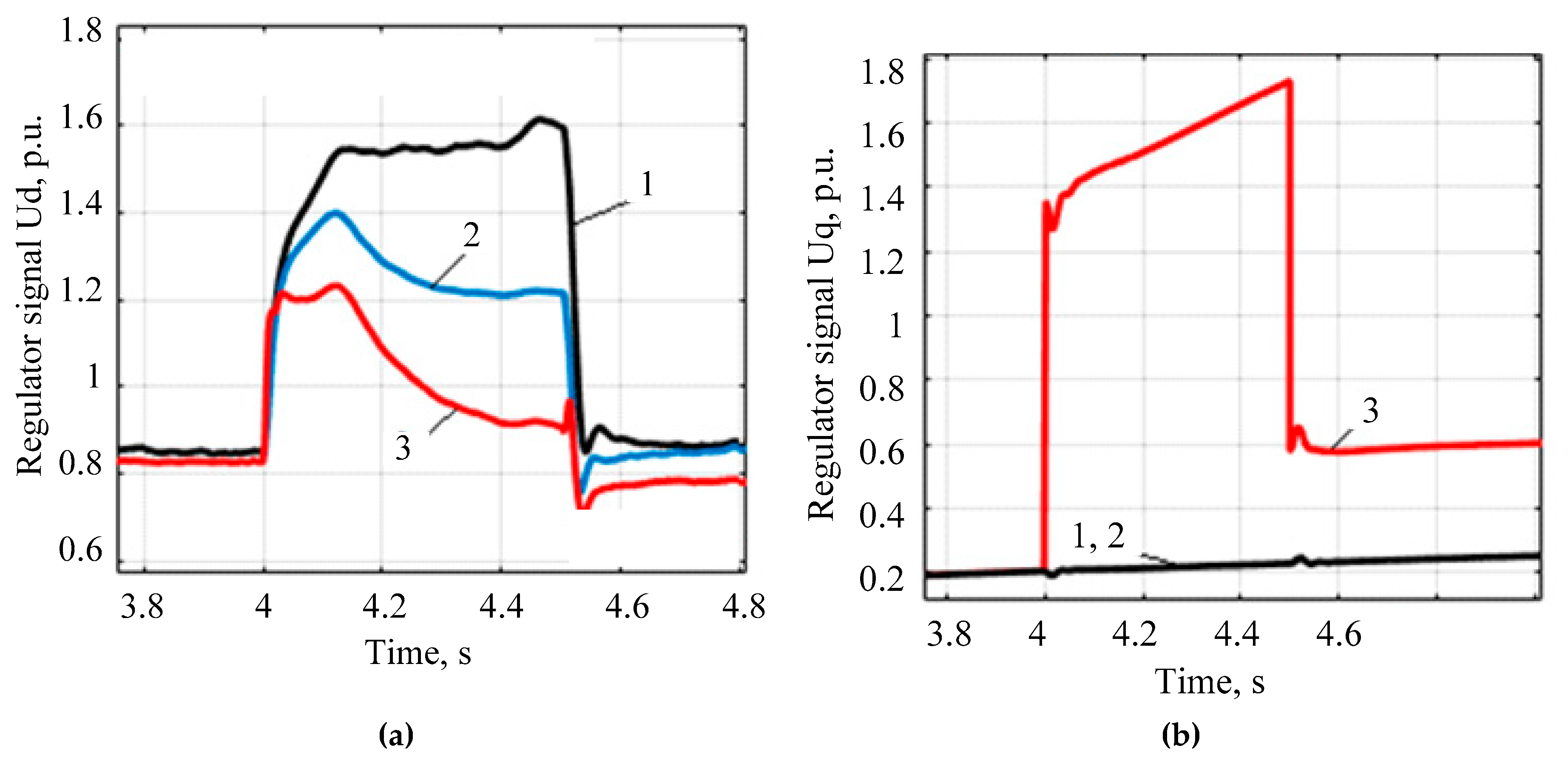

4. Simulation Results

5. Conclusions

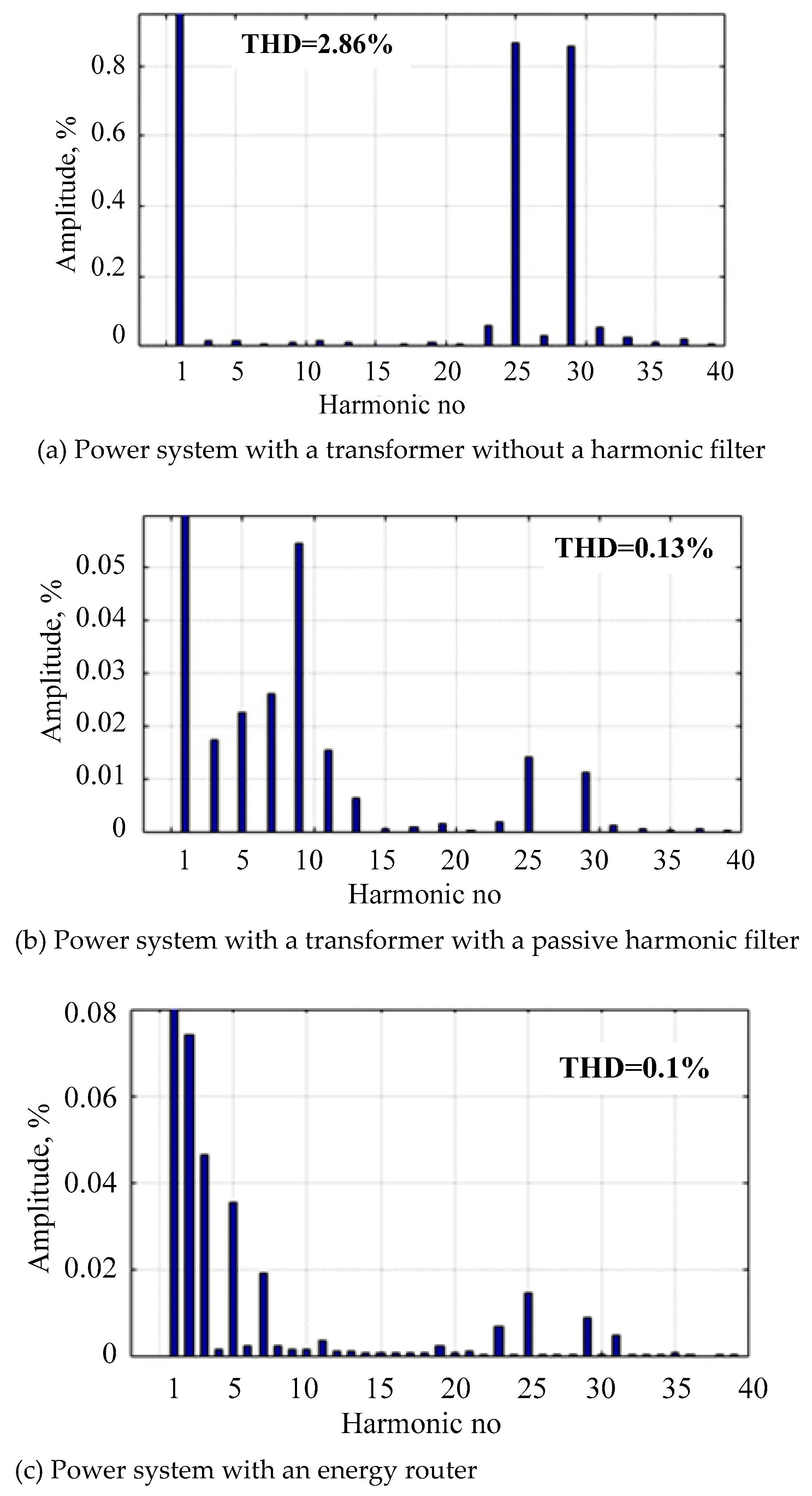

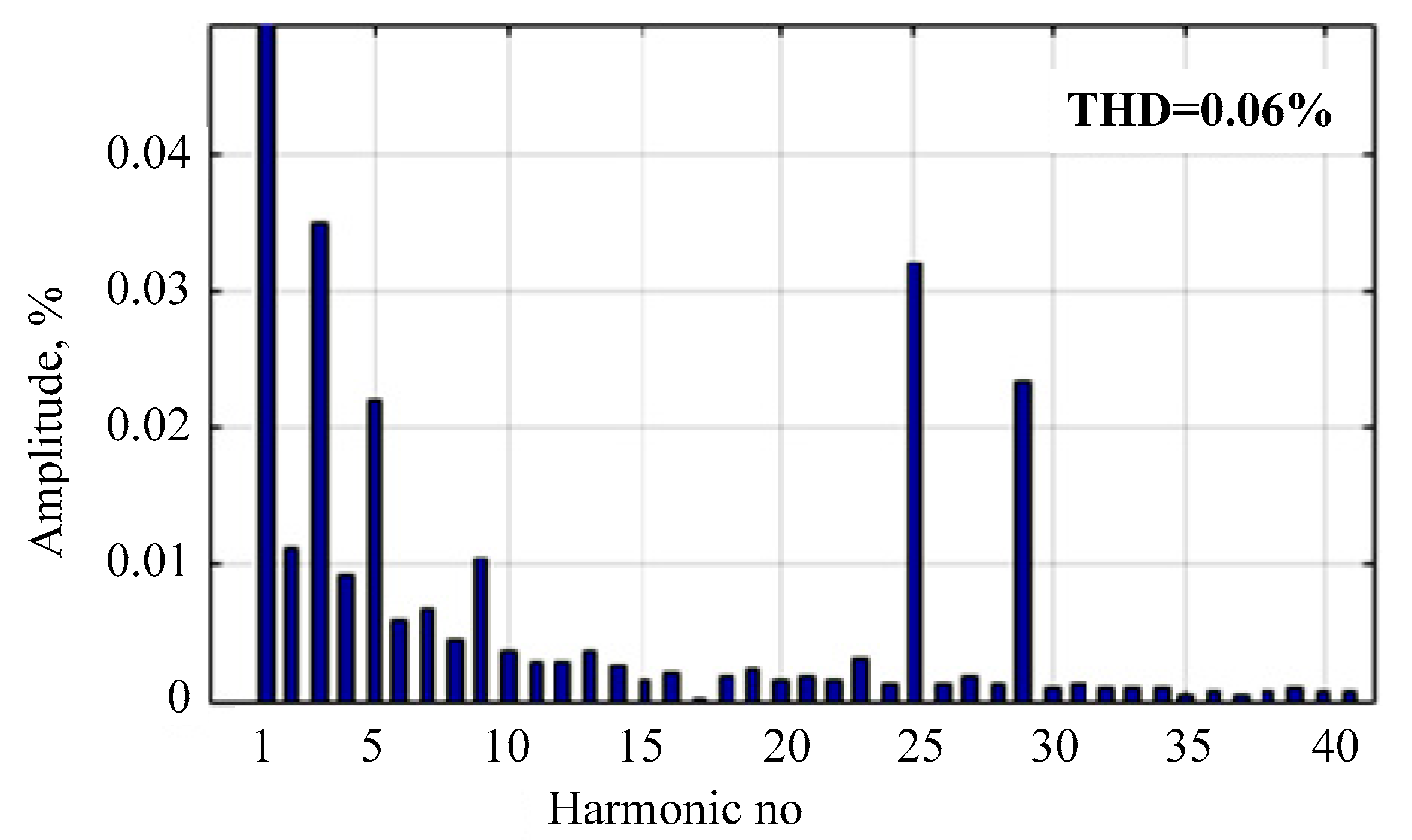

- Simulation modeling was performed for a power system incorporating an electric vehicle charging station. Connecting the charging station through a standard transformer and a bidirectional AC/DC converter produces noticeable harmonic voltage distortions (the THD kU is 2.9%). Installing a passive filter can reduce kU to 0.13%. The use of an energy router in a power supply system significantly reduces the amplitudes of the generated harmonics at the 0.4 kV consumer buses: the THD kU in a steady state declines by 29 times from 2.9 to 0.1%. Complete suppression of high-harmonics can be achieved using active filters with an appropriate control algorithm.

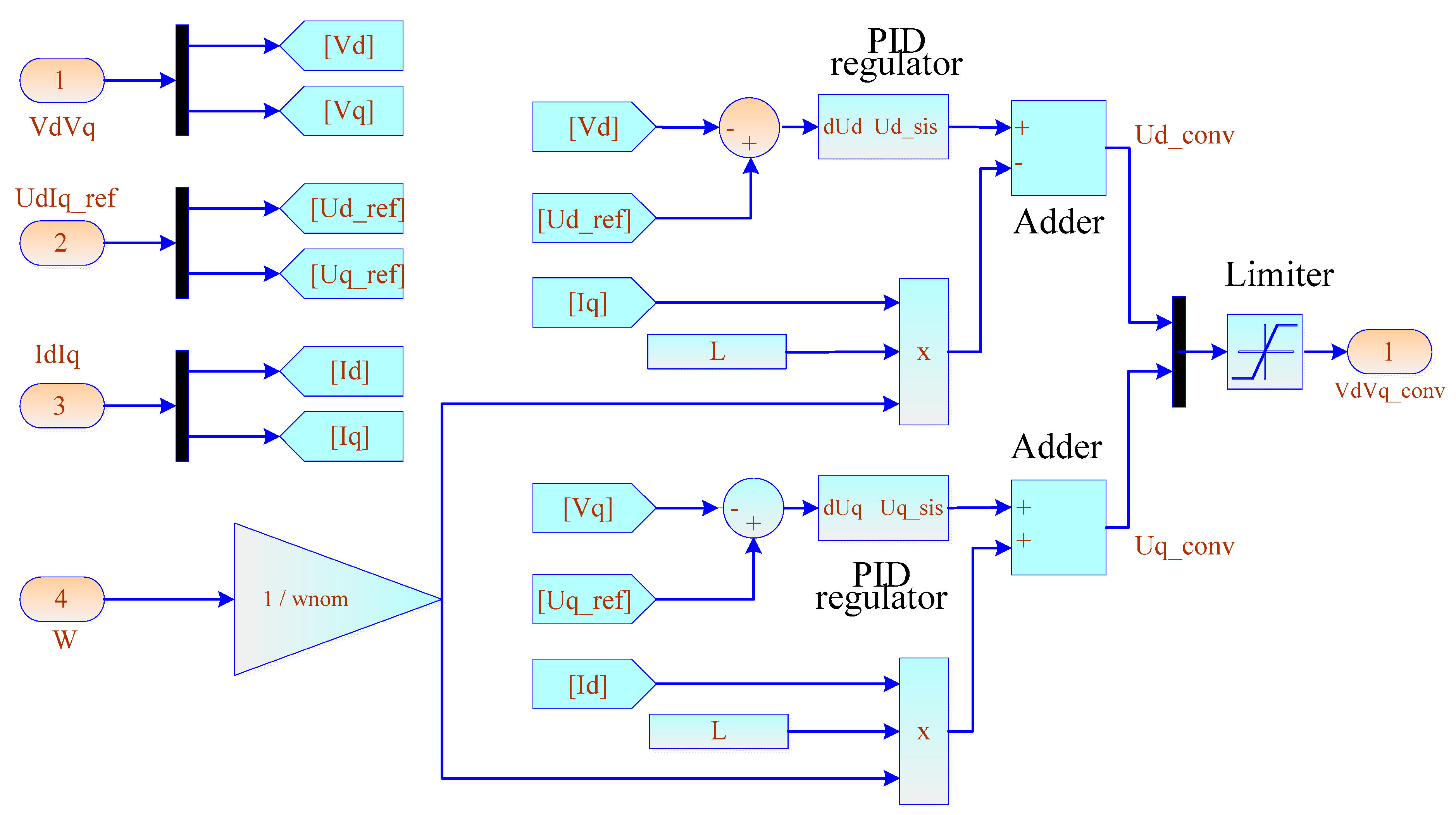

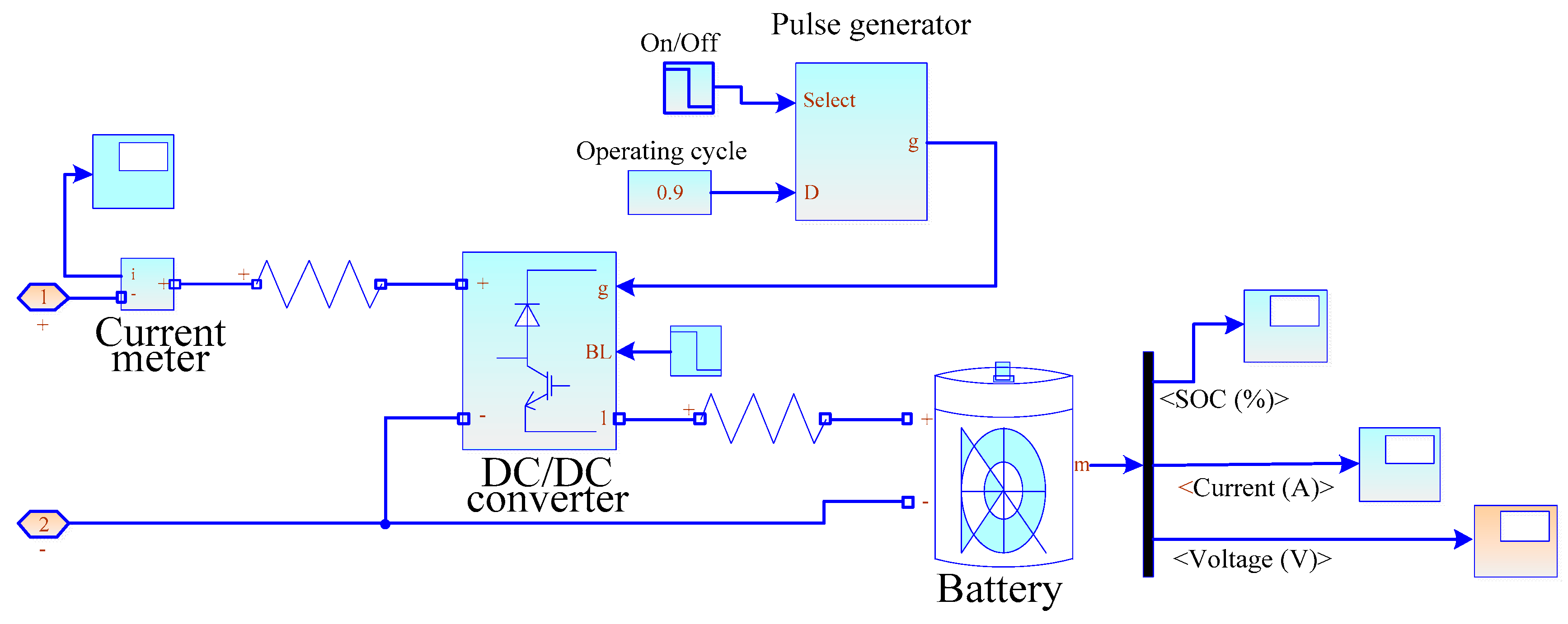

- A modified model of the voltage regulator of the energy router inverter is developed. An algorithm for stabilizing the DC and AC voltage is proposed, relying on the transformation of three-phase coordinates a–b–c into the system d–q–0. The diagrams and description of the models for the power system based on the energy router with a DC charging station and a DC/DC converter to control the mode of electric vehicle batteries are presented.

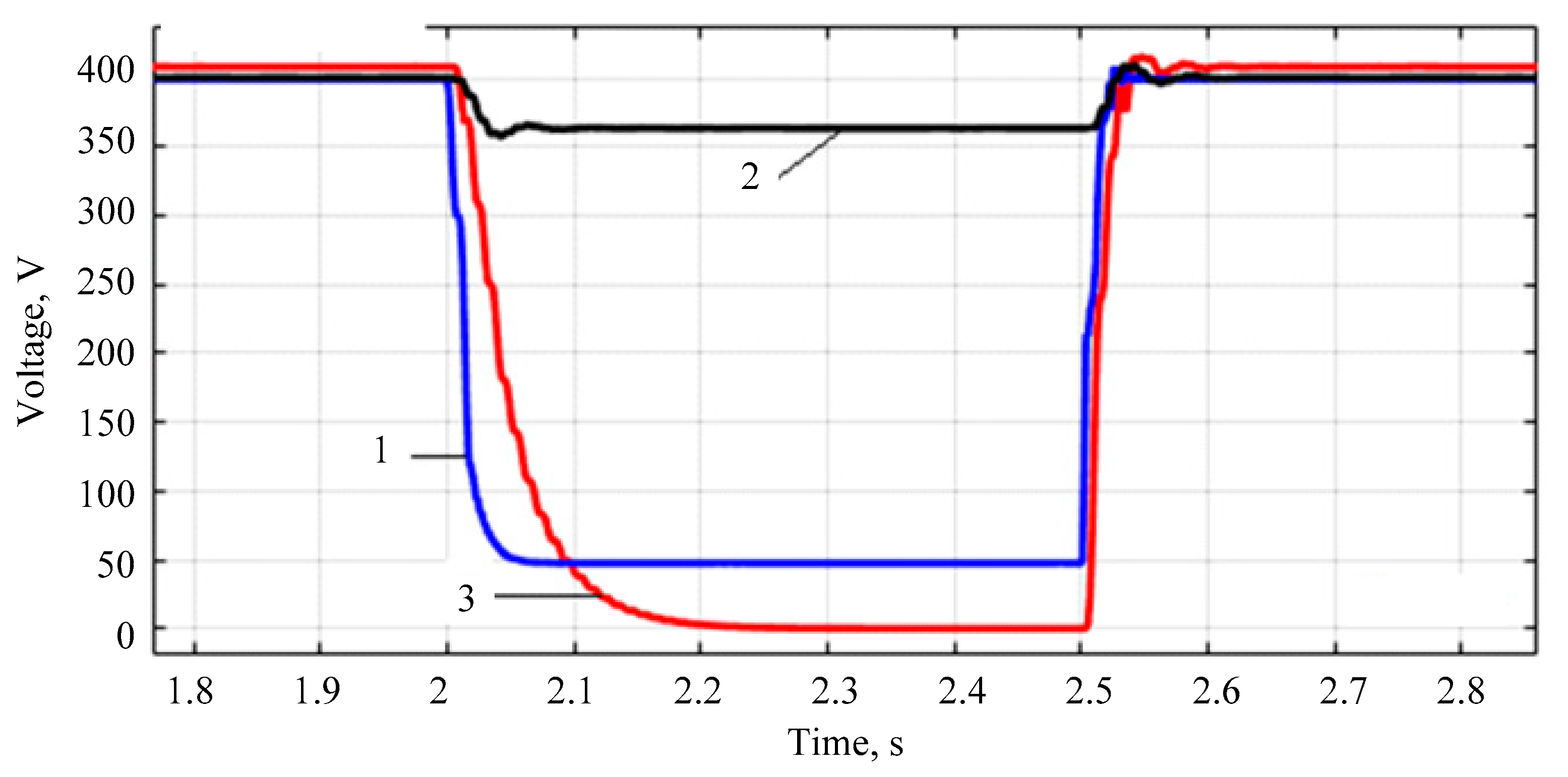

- Modeling of the power supply system under short-circuit conditions shows that the system with the energy router, in contrast to the power supply system with a standard transformer, is able to maintain the voltage close to the nominal value. This is because the modeling employed a unidirectional AC/DC converter on the 10 kV side of the energy router and there was no power supply to the short circuit location from the energy router.

- The proposed regulator allows maintaining the voltage at the consumer near the nominal value when connecting an additional load. At the same time, voltage forcing and the energy storage device ensure a rapid increase in voltage to the nominal value.

- The proposed energy router regulator can reduce voltage dips and improve the power quality in terms of harmonic content. With the proposed regulator, the total harmonic distortion decreased by 1.7 times from 0.1% to 0.06%. This leads to the conclusion that enhancing the control algorithm of the energy router inverter improves the power quality. Further research needs to be conducted to design, test, and refine voltage regulation systems for energy router converters that incorporate energy storage devices and charging stations equipped with active filters to enhance the electric power quality. In this case, for multi-objective control, artificial intelligence systems can be applied. Based on these, it is possible to develop and implement an active harmonic filtering algorithm into the overall control system of the energy router.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, X.; Dong, Z.; Cai, Y.; Jin, Z.; Lei, G.; Tian, X. A comprehensive review of design optimization methods for hybrid electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 217, 115765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prempeh, I.; Awopone, A.K.; Ayambire, P.N.; El-Sehiemy, A. Optimal allocation of distributed generation units and fast electric vehicle charging stations for sustainable cities. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2025, 4, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urooj, A.; Nasir, A. Review of intelligent energy management techniques for hybrid electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2024, 92, 1112132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbian, O.; Izmailova, D.; AMashkin, A.; Glagoleva, S. Assessment of the Reliability of the Development of Infrastructure Projects on Transport in the Russian Federation. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 68, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, K.; Sadiq, M.; Uddin, W.; Gulzar, M.M.; Alqahtani, M.; Khalid, M. A Systematic review of topologies, control strategies, challenges, recent developments, and future prospects on emerging electric vehicle chargers. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 61, 101846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haya, A.; Zoltán, R. Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure and Charging Technologies. Haditechnika 2020, 54, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.H.; Mohammadi, J.; Kar, S. Distributed holistic framework for smart city infrastructures: Tale of interdependent electrified transportation network and power grid. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 157535–157554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.R.; Digalwar, A.K.; Routroy, S. Towards sustainable Transportation: Factors influencing electric vehicle charging stations development. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 77, 104339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanu, P.; Vibin, R.; Gnanaprakasam, C.N.; Srilakshmi, K. Optimizing electric vehicle charging station performance: Integrating Gazelle Optimization Algorithm and Hamiltonian Deep Neural Networks for reduced costs and enhanced efficiency. J. Energy Storage 2025, 136, 118250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, A.; Strunz, K. Modeling of an electric vehicle charging station for fast DC charging. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference, Greenville, SC, USA, 4–8 March 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvvala, J.; Kumar, K.S.; Dhananjayulu, C.; Kotb, H.; Elrashidi, A. Integration of renewable energy sources using multiport converters for ultra-fast charging stations for electric vehicles: An overview. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, M.; Ghasemi-Marzbali, A. Electric vehicle fast charging station design by considering probabilistic model of renewable energy source and demand response. Energy 2023, 267, 126545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hong, C.; Wang, S.; Qiang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiang, J.; Yang, J.; Ji, C. Research on energy management strategies for ammonia-hydrogen internal combustion engine hybrid electrical vehicles. Energy 2025, 334, 137548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, S.; Das, D.; Aeloiza, E.; Maitra, A.; Rajagopalan, S. Hybrid distribution transformer: Concept development and field demonstration. In Proceedings of the IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Raleigh, NC, USA, 15–20 September 2012; pp. 4061–4068. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S.; Roh, M.; Kim, M.; Oh, J.; Kim, S. How electric vehicles impact the power grid: A spatially high-resolution analysis of charging demand and power system dynamics. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 59, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiringer, T.; Haghbin, S. Power quality issues of a battery fast charging station for a fully-electric public transport system in Gothenburg City. Batteries 2015, 1, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, P.S.; Deilami, S.; Masoum, A.S.; Masoum, M.A.S. Power quality of smart grids with plug-in electric vehicles considering battery charging profile. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT Europe), Gothenburg, Sweden, 11–13 October 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, A.; Bonavitacola, F.; Kotsakis, E.; Fulli, G. Grid harmonic impact of multiple electric vehicle fast charging. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2015, 127, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Muyeen, S.M.; Iqbal, A.; Ilahi, F.; Ben-Brahim, B. Effect of battery storage based electric vehicle chargers on harmonic profile of power system network, current scenario and future scope. J. Energy Storage 2025, 131 Pt B, 117563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desticioglu, B.; Erdin, T.; Simsek, K.A. Capacited range coverage location model for electric vehicle charging stations: A case of Istanbul-Ankara highway. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 19, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voropai, N.I.; Suslov, K.V.; Sokolnikova, T.V.; Styczynski, Z.A.; Lombardi, P. Development of power supply to isolated territories in Russia on the bases of microgrid concept. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyushin, P.; Georgievskiy, I.; Boyko, E. Application Methods of Efficient Electricity Storage Systems to Improve Flexibility of Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon), Sochi, Russia, 8–14 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamarova, N.; Suslov, K.; Ilyushin, P.; Shushpanov, I. Review of battery energy storage systems modeling in microgrids with renewables considering battery degradation. Energies 2022, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyushin, P.V. Analysis of the specifics of selecting relay protection and automatic (RPA) equipment in distributed networks with auxiliary low-power generating facilities. Power Technol. Eng. 2018, 51, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voropai, N.; Styczysnki, Z.; Shushpanov, I.; Suslov, K. Mathematical model and topological method for reliability calculation of distribution networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Grenoble Conference Powertech, Grenoble, France, 16–20 June 2013; p. 6652129. [Google Scholar]

- She, X.; Huang, A.Q.; Burgos, R. Review of Solid State Transformer technologies and their applications in power distribution system. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2013, 1, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushpanov, I.; Suslov, K.; Ilyushin, P.; Sidorov, D.N. Towards the flexible distribution networks design using the reliability performance metric. Energies 2021, 14, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, J.W.; Ortiz, G. Solid-state-transformers: Key components of future traction and smart grid systems. In Proceedings of the International Power Electronics Conference (IPEC), Hiroshima, Japan, 18–21 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bulatov, Y.; Kryukov, A.; Arsentyev, G. Application of energy routers in railway power supply systems. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 239, 01047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volnyi, V.; Ilyushin, P.; Boyko, E. Approaches to Construction of Active Distribution Networks with Distributed Power Sources Based on Solid-State Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon), Sochi, Russia, 8–14 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatov, Y.N.; Kryukov, A.V.; Arsentiev, G.O. Use of Power Routers and Renewable Energy Resources in Smart Power Supply Systems. In Proceedings of the International Ural Conference on Green Energy (UralCon), Chelyabinsk, Russia, 4–6 October 2018; pp. 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sosnina, E.N.; Shumskii, N.V.; Shramko, P.A. Development of a distributed energy router control system based on a neural network. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Ural Conference on Electrical Power Engineering (UralCon)–IEEE, Chelyabinsk, Russia, 22–24 September 2020; pp. 313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Oukhouya Ali, Y.; EL Haini, J. Energy management strategies for grid-integrated photovoltaic and battery energy storage systems-enhanced electric vehicle charging stations: Classical approaches and neural network solutions. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 43, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsel, M.; Kilic, H.S.; Kalender, Z.T.; Tuzkaya, G. Multi-objective model for electric vehicle charging station location selection problem for a sustainable transportation infrastructure. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 198, 110695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Xie, X. Performance evaluation and cost optimization for electric vehicle charging stations. Energy 2025, 332, 137017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, S.; Choi, J.; Zheng, C. A hybrid deep learning model for load forecasting of electric vehicle charging stations using time series decomposition. J. Power Sources 2025, 655, 237882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H. (Ed.) Handbook of Power Electronics in Autonomous and Electric Vehicles; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Juneja, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Energy router: Architectures and functionalities toward Energy Internet. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), Brussels, Belgium, 17–20 October 2011; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshuddin, M.A.; Rojas, F.; Cardenas, R.; Pereda, J.; Diaz, M.; Kennel, R. Solid State Transformers: Concepts, Classification, and Control. Energies 2020, 13, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, B.M.; Jibril, Y.; Jimoh, B.; Kunya, A.B.; Aliyu, S. Energy router applications in the electric power system. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 4, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouani, I.; Guesmi, T.; Alshammari, B.M.; Alqunun, K.; Alshammari, A.S.; Albadran, S.; Hadj Abdallah, H.; Rahmani, S. Optimized FACTS Devices for Power System Enhancement: Applications and Solving Methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fan, X.; Huang, R.; Huang, Q.; Li, A.; Guddanti, K. Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Technology in Power System Applications; PNNL-35735; 2340760; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-L.; Sun, Q.-Y.; Li, Y.-Y.; Liu, X.-R. Optimal Energy Routing Design in Energy Internet with Multiple Energy Routing Centers Using Artificial Neural Network-Based Reinforcement Learning Method. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Yadav, A.; You, S.; Dong, J.; Kuruganti, T.; Liu, Y. Neural Networks-Based Inverter Control: Modeling and Adaptive Optimization for Smart Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2024, 15, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H. Power Electronics Handbook: Devices, Circuits, and Applications, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Ge, N.; Xu, J. Power Supply Reliability Analysis of Distribution Systems Considering Data Transmission Quality of Distribution Automation Terminals. Energies 2023, 16, 7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bulatov, Y.; Kryukov, A.; Kizhin, V.; Suslov, K.; Iliev, I.; Beloev, H.; Beloev, I. Modeling an Energy Router with an Energy Storage Device for Connecting Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Sustainable Development of Power Supply Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411041

Bulatov Y, Kryukov A, Kizhin V, Suslov K, Iliev I, Beloev H, Beloev I. Modeling an Energy Router with an Energy Storage Device for Connecting Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Sustainable Development of Power Supply Systems. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411041

Chicago/Turabian StyleBulatov, Yuri, Andrey Kryukov, Vadim Kizhin, Konstantin Suslov, Iliya Iliev, Hristo Beloev, and Ivan Beloev. 2025. "Modeling an Energy Router with an Energy Storage Device for Connecting Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Sustainable Development of Power Supply Systems" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411041

APA StyleBulatov, Y., Kryukov, A., Kizhin, V., Suslov, K., Iliev, I., Beloev, H., & Beloev, I. (2025). Modeling an Energy Router with an Energy Storage Device for Connecting Electric Vehicle Charging Stations and Sustainable Development of Power Supply Systems. Sustainability, 17(24), 11041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411041